Abstract

Aims/Introduction: Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is one of the contributing factors in the development of type 2 diabetes. To investigate the cytoprotective effect of glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor (GLP‐1R) signaling in vivo, we examined the action of exendin‐4 (Ex‐4), a potent GLP‐1R agonist, on β‐cell apoptosis in Akita mice, an animal model of ER stress‐mediated diabetes.

Materials and Methods: Ex‐4, phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) or phlorizin were injected intraperitoneally twice a day from 3 to 5 weeks‐of‐age. We evaluated the changes in blood glucose levels, bodyweights, and pancreatic insulin‐positive area and number of islets. The effect of Ex‐4 on the numbers of C/EBP‐homologous protein (CHOP)‐, TdT‐mediated dUTP‐biotin nick‐end labeling (TUNEL)‐ or proliferating cell nuclear antigen‐positive β‐cells were also evaluated.

Results: Ex‐4 significantly reduced blood glucose levels and increased both the insulin‐positive area and the number of islets compared with PBS‐treated mice. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the insulin‐positive area between PBS‐treated mice and phlorizin‐treated mice, in which blood glucose levels were controlled similarly to those in Ex‐4‐treated mice. Furthermore, treatment of Akita mice with Ex‐4 resulted in a significant decrease in the number of CHOP‐positive β‐cells and TUNEL‐positive β‐cells, and in CHOP mRNA levels in β‐cells, but there was no significant difference between the PBS‐treated group and the phlorizin‐treated group. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen staining showed no significant difference among the three groups in proliferation of β‐cells.

Conclusions: These data suggest that Ex‐4 treatment can attenuate ER stress‐mediated β‐cell damage, mainly through a reduction of apoptotic cell death that is independent of lowered blood glucose levels. (J Diabetes Invest, doi: 10.1111/j.2040‐1124.2010.00075.x, 2010)

Keywords: Apoptosis, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, Glucagon‐like peptide‐1

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by the loss of β‐cell function and mass. The mechanisms underlying the loss of β‐cell function and mass are not fully understood, but recent studies have shown that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is one of the causes of β‐cell damage in diabetes1. Owing to increased demand for insulin secretion, β‐cells show a highly developed ER1. The ER has a number of important functions, such as post‐translational modification, folding and assembly of newly synthesized secretory proteins2–4. Thus, the ER plays an essential role in cell survival. ER function can be impaired by various conditions, including inhibition of protein glycosylation, reduction in formation of disulfide bonds, calcium depletion from the ER lumen, impairment of protein transport from the ER to the Golgi and expression of malfolded proteins1. Various physiological or pathological conditions that compromise ER functions are collectively termed ER stress1–3. To alleviate ER stress and promote cell survival, an adaptive response, known as unfolded protein response (UPR) is activated. UPR comprises translational attenuation, induction of chaperones and ER stress‐associated degradation (ERAD). However, prolonged activation of UPR can ultimately lead to cell death by apoptosis.

Increased demand for insulin secretion under certain conditions, such as chronic hyperglycemia, might result in β‐cell overload. Chronic hyperglycemia in diabetes can therefore induce persistent ER stress, cause β‐cell dysfunction and finally lead to a reduction in β‐cell mass through apoptosis1.

Glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) is a physiological incretin, an intestinal hormone released in response to nutrient ingestion that stimulates glucose‐dependent insulin secretion. A growing body of evidence suggests that GLP‐1 not only increases insulin secretion and upregulates insulin biosynthesis, but also stimulates β‐cell proliferation and neogenesis5–9, and inhibits β‐cell apoptosis9–16, resulting in increased β‐cell mass. However, demonstration of an in vivo effect in the animal models of type 2 diabetes is problematic, because enhancement of GLP‐1R signaling lowers blood glucose levels as result of its insulinotropic action, and it is difficult to evaluate the direct cytoprotective effects of GLP‐1 in conditions of similar glucose toxicity.

In the present study, we investigated the cytoprotective effect of GLP‐1R signaling in vivo on ER stress‐mediated apoptotic cell death by using Akita mice, an animal model of ER stress‐mediated diabetes mellitus. Akita mice have a point mutation in the insulin 2 gene, resulting in misfolding of insulin that leads to severe ER stress17,18. To exclude the possibility that the effect of Ex‐4 on β‐cells is mediated through improved blood glucose levels, we used three groups of mice: Akita mice treated with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), Ex‐4, or the sodium‐coupled glucose transporter inhibitor phlorizin, which decreases blood glucose levels without increasing insulin secretion.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice and male Akita mice were obtained from Shimizu (Kyoto, Japan). The animals were housed under a light/dark cycle of 12 h with free access to food and water. All experiments were approved by the Kyoto University Animal Care Committee.

In vivo Treatment

The mice were given twice daily intraperitoneal injections of PBS, Ex‐4 (24 nmol/kg) or phlorizin (0.3 g/kg) for 2 weeks (from 3 to 5 weeks‐of‐age). Blood glucose levels were measured every third day by enzyme electrode method using a portable glucose analyzer (Glutest sensor; Sanwakagaku, Nagoya, Japan). Blood samples were collected from tail cuttings from these mice fed ad libitum. At the end of the experimental period, blood samples were collected from the inferior vena cava under anesthesia to determine the plasma glycoalbumin levels (Oriental Yeast, Tokyo, Japan). Pancreas samples from each of the animal groups were obtained for histological evaluation, and islets were isolated for measurement of insulin content and RNA extraction.

Evaluation of Pancreatic Insulin‐Positive Area and Number of Islets

The pancreas samples were fixed in Bouin’s solution. Serial 5‐μm paraffin‐embedded tissue sections were mounted on slides. After rehydration, sections were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti‐insulin antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), with a biotinylated goat anti‐rabbit antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA), and then with a streptavidin peroxidase conjugate and substrate kit (DAKO) using standard protocols. The total pancreas area and insulin‐positive area were quantified on five distal, random, non‐overlapping sections from five mice of each group using a BZ‐8100 microscope equipped with a BZ‐Analyzer (KeyEnce, Osaka, Japan). Insulin‐positive areas and the number of islets of each group were adjusted by total pancreas area15.

Measurement of Insulin Contents of Isolated Islets

Pancreatic islets were isolated by collagenase digestion. To determine insulin contents, islets were homogenized in 400 μL acid ethanol (37% HCl in 75% ethanol, 15:1000 [v/v]) and extracted at 4°C overnight. The acidic extracts were dried by vacuum, reconstituted and subjected to insulin measurement. The amount of immunoreactive insulin was determined by radioimmunoassay (RIA).

Measurement of mRNA Expression of C/EBP‐Homologous Protein and BiP in Isolated Islets

Measurement of mRNA expression of C/EBP‐homologous protein (CHOP) and BiP was carried out by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) as described previously19. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from isolated islets with an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and treated with DNase (Qiagen). cDNA was prepared by SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase system (Invitrogens, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CHOP mRNA levels and BiP mRNA levels in the islets were measured by quantitative RT–PCR using an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The sequences of forward and reverse primers to evaluate CHOP expression were 5′‐GAGCT‐ GGAAGCCTGGTATGA‐3′ and 5′‐GGACGCAGGGTCAAGAGTAG‐3′, respectively; the sequences of forward and reverse primers to evaluate BiP expression were 5′‐TTTCTGCCATGGTTCTCACTAA‐3′ and 5′‐GCTGGGCATCATTGAAGTAAG‐3′, respectively; and the sequences of forward and reverse primers to evaluate glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression were 5′‐AGCTCACTGGCATGGCTTCCG‐3′ and 5′‐GCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGATG‐3′, respectively. SYBER Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was prepared for the PCR run. Thermal cycling conditions were denatured at 95°C for 10 min followed by 50 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Total CHOP and total BiP levels were corrected by GAPDH mRNA levels.

Immunofluorescence Staining

For pancreatic CHOP and insulin immunohistochemistry, the tissues were fixed and embedded in paraffin. Serial 5‐μm sections were stained with anti‐CHOP/GADD153 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti‐insulin (DAKO) antibodies using standard protocols. Insulin immunopositive areas were measured on five distal, random, non‐overlapping sections from five mice of each group using a BZ‐8100 fluorescence microscope equipped with a BZ‐Analyzer (KeyEnce), and the number of cells showing both nuclear CHOP and cytoplasmic insulin immunopositivity was determined. The ratio of CHOP‐positive β‐cells was calculated by adjusting the number of CHOP‐positive β‐cells by the insulin‐positive area20. The effect of Ex‐4 treatment on β‐cell replication and apoptosis was evaluated histologically by proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) staining (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and TdT‐mediated dUTP‐biotin nick‐end labeling (TUNEL) staining (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan), respectively. The ratio of TUNEL‐positive and PCNA‐positive β‐cells was also calculated as described earlier.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were carried out by unpaired t‐test. A P‐value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of Ex‐4 on Hyperglycemia and Bodyweight in Akita Mice

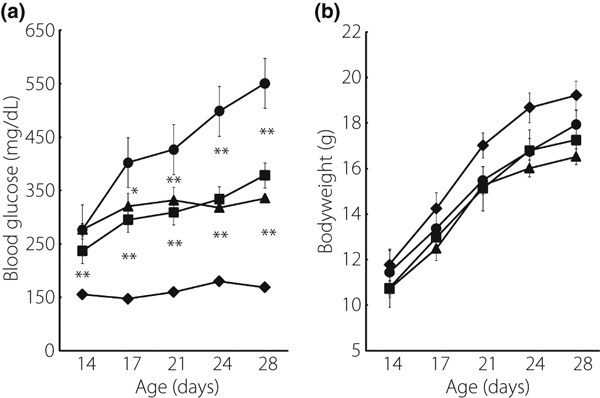

Akita mice showed acute and progressive hyperglycemia at 14 days after birth and thereafter. Twice‐daily intraperitoneal injection of Ex‐4 from 3 to 5 weeks‐of‐age significantly reduced blood glucose levels compared with those in PBS‐treated mice (Figure 1a). Plasma glucose levels in phlorizin‐treated Akita mice were similar to those in Ex‐4‐treated mice. Plasma glycoalbumin levels were significantly lower in the Ex‐4‐ and phlorizin‐treated groups than those in the PBS‐treated group, but no significant difference was observed between the Ex‐4‐ and phlorizin‐treated groups (12.9 ± 1.5 vs 8.7 ± 0.7 vs 8.2 ± 0.6, respectively, n = 10–12). Ex‐4 treatment or phlorizin treatment did not change bodyweight compared with PBS treatment (Figure 1b). Ex‐4 or phlorizin treatment did not change the amount of food intake assessed at 4 weeks‐of‐age (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Ex‐4 significantly reduced blood glucose levels in Akita mice. (a) Blood glucose concentration and (b) bodyweight were measured in wild‐type C56BL/6 mice (closed diamond, n = 10), Akita mice treated with PBS alone (closed circle, n = 10), Ex‐4 (closed square, n = 12) and phlorizin (closed triangle, n = 10). Each symbol represents mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs PBS‐treated Akita mice.

Effect of Ex‐4 on Insulin‐Positive Area and Number of Islets

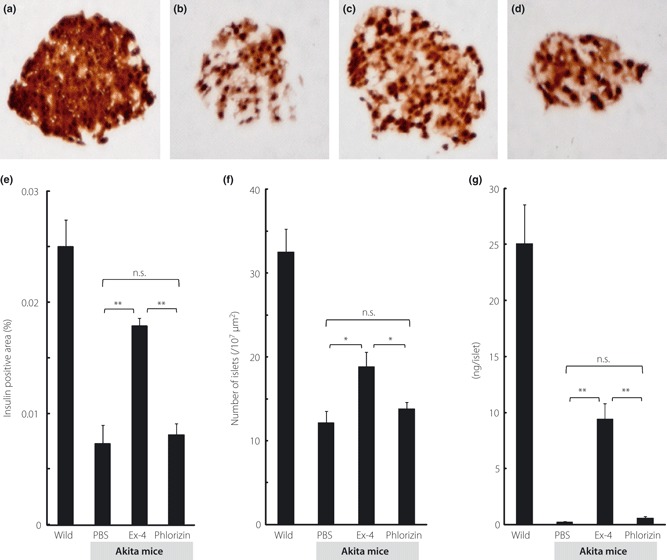

Preservation of β‐cell morphology was observed by treatment with Ex‐4, as shown in Figure 2a. Quantitative histological analyses showed that Ex‐4 treatment significantly increased both the insulin‐positive area and the number of islets, whereas there was no significant difference between the PBS‐treated group and the phlorizin‐treated group (Figure 2b,c).

Figure 2.

Ex‐4 treatment increased insulin‐positive areas, number of islets and insulin content. (a–d) Representative mouse pancreata at 5 weeks‐of‐age stained with insulin. (a) Wild, (b) Akita mice treated with PBS, (c) Ex‐4 or (d) phlorizin. (e) Insulin‐positive areas and (f) number of islets were evaluated as described in Materials and Methods (n = 5 for each group). (g) Pancreatic insulin content was measured as described in Materials and Methods, and expressed as ng/islet (n = 5 for each group). Each column represents mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Effect of Ex‐4 on Pancreatic Insulin Content

Figure 2d shows the effect of Ex‐4 treatment on insulin content in pancreatic islets. Treatment with Ex‐4 significantly increased insulin content in isolated islets, but phlorizin treatment did not.

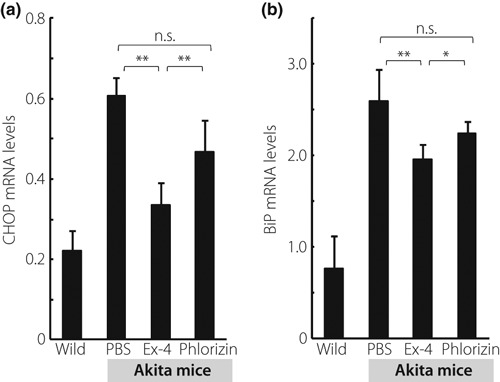

Quantitative Estimation of CHOP and BiP Expression Levels by Real‐Time PCR

The expression levels of CHOP mRNA are shown in Figure 3a, and those of BiP mRNA are shown in Figure 3b. Ex‐4 significantly lowered the expression levels of CHOP and BiP mRNA, but there was no significant difference in the expression levels of CHOP or BiP mRNA between the phlorizin‐ or PBS‐treated groups.

Figure 3.

Ex‐4 treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the expression levels of C/EBP‐homologous protein (CHOP) mRNA and Bip mRNA in Akita mice. (a) mRNA expression levels of CHOP were evaluated by quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). (b) mRNA expression levels of BiP were evaluated by quantitative real‐time PCR. Data are expressed as the ratio to that of glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase in the same sample (n = 5 for each group). Each column represents mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

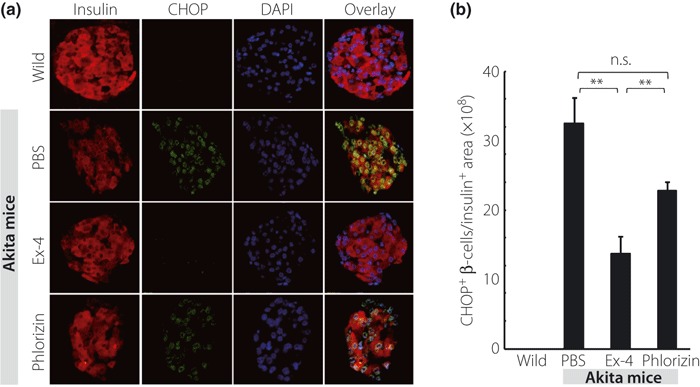

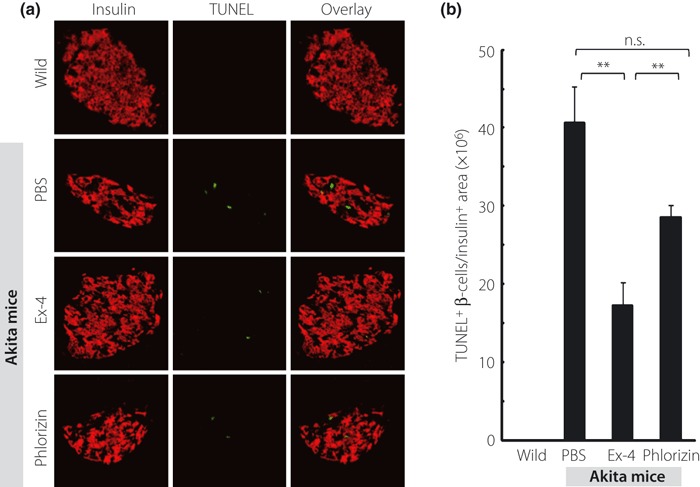

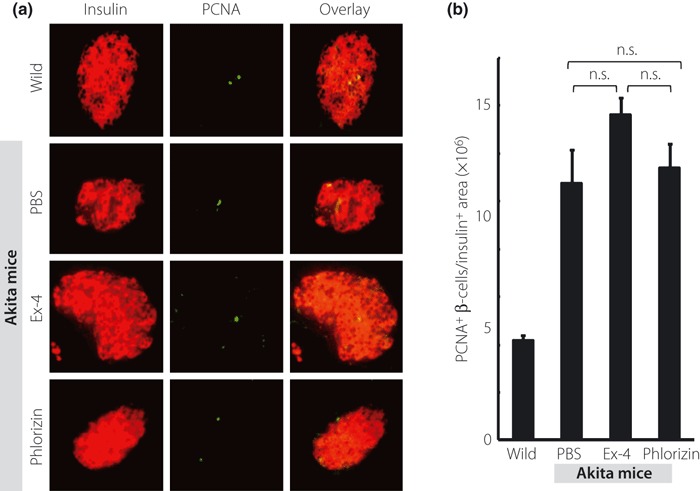

Effect of Ex‐4 on the Ratio of CHOP‐, TUNEL‐ and PCNA‐Positive β‐cells

Figure 4a depicts the representative pancreata stained with insulin (red), CHOP (green) and DAPI (blue), respectively. Similarly, Figure 5a shows the representative pancreata stained with insulin (red) and TUNEL (green). Treatment with Ex‐4 significantly decreased the ratio of CHOP‐positive β‐cells and TUNEL‐positive β‐cells (Figures 4b and 5b), but there was no significant difference in the ratio of CHOP‐positive or TUNEL‐positive β‐cells between the PBS‐ and phlorizin‐treated groups. Figure 6a shows the representative pancreata stained with insulin (red) and PCNA (green). PCNA staining showed no significant difference in proliferation of β‐cells among the three groups of Akita mice (Figure 6b). Interestingly, the ratio of PCNA‐positive β‐cells was increased in all three groups when compared with wild‐type C57BL/6 mice.

Figure 4.

Ex‐4 treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the ratio of C/EBP‐homologous protein (CHOP)‐positive β‐cells in Akita mice. (a) Representative mouse pancreata at 5 weeks‐of‐age stained with insulin (red), CHOP (green) and DAPI (blue). (b) The number of CHOP‐positive β‐cells normalized per insulin‐positive area was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Each column represents mean ± SE. **P < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Ex‐4 treatment decreased the ratio of TUNEL‐positive β‐cells. (a) Representative mouse pancreata at 5 weeks‐of‐age stained with insulin (red) and TUNEL (green). (b) The number of TUNEL‐positive β‐cells normalized per insulin‐positive area was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Each column represents mean ± SE. **P < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Ex‐4 treatment did not significantly increase the ratio of PCNA‐positive β‐cells. (a) Representative mouse pancreata at 5 weeks‐of‐age stained with insulin (red) and PCNA (green). (b) The number of PCNA‐positive β‐cells normalized per insulin‐positive area was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Each column represents mean ± SE.

Discussion

Akita mice are widely used as an animal model of ER stress‐mediated diabetes. Akita mice have a point mutation (C96T) in the insulin 2 gene21 that disrupts the disulfide bond formation between the A and B chains of proinsulin, resulting in a drastic conformational change of the molecule. The unfolded proinsulin accumulates to the ER, causing severe ER stress leading to β‐cell apoptosis. In humans, it has recently been shown that a mutation in the insulin gene, which is identical to that in the Akita mouse, causes permanent neonatal diabetes within the first month of life that requires lifelong insulin injection22.

In the present study, we have shown that Ex‐4 treatment has a protective effect on β‐cells in Akita mice. The insulin‐positive area and the number of islets were maintained along with a decreased ratio of CHOP‐ and TUNEL‐positive cells in the islets, showing that the major effect of Ex‐4 treatment in the maintenance of β‐cell mass is through decreasing β‐cell apoptosis in response to ER stress. Because phlorizin decreases blood glucose levels without increasing insulin secretion, it might well reduce ER stress by decreasing the insulin demand. However, in contrast to the Ex‐4 treatment, phlorizin treatment failed to show a reduction of ER stress or β‐cell protective effects against apoptosis in our conditions. These findings show that Ex‐4 has a direct effect on ER stress‐mediated β‐cell apoptosis that is independent of decreased insulin demand.

There are several in vitro and in vivo studies showing that GLP‐1R agonists inhibit β‐cell apoptosis9–16, and several molecular mechanisms have been suggested. For example, GLP‐1 treatment decreases the expression levels of proapoptotic protein caspase‐3 and increases those of anti‐apoptotic protein bcl‐2 in isolated human islets10. It also has been shown that the anti‐apoptotic effect of Ex‐4 is associated with the activation of protein kinase B/Akt through PKA‐dependent phosphorylation of CREB11. There are some reports that GLP‐1 ameliorates ER stress. Yusta et al. found that treatment by Ex‐4 reduces blood glucose levels in obese db/db mice along with a decrease in the number of CHOP‐positive β‐cells20. Tsunekawa et al.23 reported a beneficial effect of Ex‐4 on β‐cell damage in calmodulin‐overexpressing transgenic (CaMTg) mice that develop diabetes through ER stress‐mediated β‐cell apoptosis. They found that Ex‐4 treatment reduced blood glucose levels while retaining the insulin‐positive areas and decreasing the expression levels of CHOP mRNA in CaMTg mice. In vitro studies have found that rapid recovery from translational attenuation19 or upregulation of BiP and JunB24 accounts for the attenuation of ER stress‐mediated β‐cell damage by Ex‐4 treatment. However, results of chronic Ex‐4 treatment in animal models of type 2 diabetes should be carefully interpreted, because enhancement of GLP‐1R signaling reduces the blood glucose level by its insulinotropic action. Therefore, the possibility remains that reduced hyperglycemia attenuates persistent ER stress and ameliorates β‐cell apoptosis. Our present findings clearly show that Ex‐4 treatment attenuates ER stress‐mediated β‐cell damage in Akita mice through a reduction of apoptotic cell death that is independent of decreased blood glucose levels.

Although several studies have found that the cytoprotective effect of GLP‐1R signaling is not only through inhibition of β‐cell apoptosis, but also through stimulation of β‐cell proliferation5–9, we did not find any effect of Ex‐4 treatment on β‐cell proliferation. It is possible that the administration period in the present study was too short to observe β‐cell proliferation by Ex‐4 or that stimulation of β‐cell proliferation does not play a significant role in the cytoprotective effect of GLP‐1R signaling in Akita mice. The ratio of PCNA‐positive β‐cells was increased not only in the Ex‐4‐treated group of Akita mice, but also in the phlorizin‐treated group and the untreated group compared with that in wild‐type C57BL/6 mice. Whether or not this result can be attributed to the phenotype of Akita mice requires further study.

Islet mass is reported to be decreased in patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis25. Although Ex‐4 is in clinical use for treatment of type 2 diabetes26, superiority of Ex‐4 over the other antidiabetic drugs has not been shown. Our data confirm the previous findings of a beneficial effect of Ex‐4 on glycemic control, but also suggest that Ex‐4 has a direct β‐cell‐protective effect independently of improved glycemic control. Thus, Ex‐4 and other GLP‐1R agonists might well be more effective than other antidiabetic drugs in clinical use in terms of alleviating β‐cell damage and maintaining β‐cell mass for diabetic patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Scientific Research Grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and from the Ministry of Health, Labor, Welfare, Japan, and by the Kyoto University Global COE Program ‘Center for Frontier Medicine’. There is no conflict of interest for all the authors listed.

References

- 1.Oyadomari S, Araki E, Mori M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress‐mediated apoptosis in pancreatic β‐cells. Apoptosis 2002; 7: 335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev 1999; 13: 1211–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori K. Tripartite management of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 2000; 101: 451–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman RJ, Scheuner D, Schroder M, et al. The unfolded protein response in nutrient sensing and differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002; 3: 411–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedrichsen BN, Neubauer N, Lee YC, et al. Stimulation of pancreatic β‐cell replication by incretins involves transcriptional induction of cyclin D1 via multiple signalling pathways. J Endocrinol 2006; 188: 481–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miettinen P, Ormio P, Hakonen E, et al. EGF receptor in pancreatic β‐cell mass regulation. Biochem Soc Trans 2008; 36: 280–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin T, Liu L. The Wnt signaling pathway effector TCF7L2 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Endocrinol 2008; 22: 2383–2392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J, Pineyro MA, Wang X, et al. Exendin‐4 differentiation of a human pancreatic duct cell line into endocrine cells: involvement of PDX‐1 and HNF3β transcription factors. J Cell Physiol 2002; 192: 304–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Q, Brubaker PL. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 treatment delays the onset of diabetes in 8 week‐old db/db mice. Diabetologia 2002; 45: 1263–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farilla L, Bulotta A, Hirshberg B, et al. Glucagon‐like peptide 1 inhibits cell apoptosis and improves glucose responsiveness of freshly isolated human islets. Endocrinology 2003; 144: 5149–5158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jhala US, Canettieri G, Screaton RA, et al. cAMP promotes pancreatic β‐cell survival via CREB‐mediated induction of IRS2. Genes Dev 2003; 17: 1575–1580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Hansotia T, Yusta B, et al. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor signaling modulates β cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 471–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buteau J, El Assaad W, Rhodes CJ, et al. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 prevents beta cell glucolipotoxicity. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 806–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bregenholt S, Moldrup A, Blume N, et al. The long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogue, liraglutide, inhibits β‐cell apoptosis in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 330: 577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S, Dong X, Fisher TL, et al. Exendin‐4 uses Irs2 signaling to mediate pancreatic β cell growth and function. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 1159–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toyoda K, Okitsu T, Yamane S, et al. GLP‐1 receptor signaling protects pancreatic beta cells in intraportal islet transplant by inhibiting apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008; 367: 793–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshioka M, Kayo T, Ikeda T, et al. A novel locus, Mody4, distal to D7Mit189 on chromosome 7 determines early‐onset NIDDM in nonobese C57BL/6 (Akita) mutant mice. Diabetes 1997; 46: 887–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oyadomari S, Koizumi A, Takeda K, et al. Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress‐mediated diabetes. J Clin Invest 2002; 109: 525–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harada N, Yamada Y, Tsukiyama K, et al. A novel GIP receptor splice variant influences GIP sensitivity of pancreatic β‐cells in obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008; 294: E61–E68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yusta B, Baggio LL, Estall JL, et al. GLP‐1 receptor activation improves β cell function and survival following induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab 2006; 4: 391–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Takeuchi T, Tanaka S, et al. A mutation in the insulin 2 gene induces diabetes with severe pancreatic β‐cell dysfunction in the Mody mouse. J Clin Invest 1999; 103: 27–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoy J, Edghill EL, Flanagan SE, et al. Insulin gene mutations as a cause of permanent neonatal diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 15040–15044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsunekawa S, Yamamoto N, Tsukamoto K, et al. Protection of pancreatic β‐cells by exendin‐4 may involve the reduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress; in vivo and in vitro studies. J Endocrinol 2007; 193: 65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunha DA, Ladriere L, Ortis F, et al. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 agonists protect pancreatic β‐cells from lipotoxic endoplasmic reticulum stress through upregulation of BiP and JunB. Diabetes 2009; 58: 2851–2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner‐Weir S, et al. β‐cell deficit and increased β‐cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2003; 52: 102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kendall DM, Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, et al. Effects of exenatide (exendin‐4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin and a sulfonylurea. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 1083–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]