SUMMARY

Sexually dimorphic mammalian tissues, including sexual organs and the brain, contain stem cells that are directly or indirectly regulated by sex hormones1-6. An important question is whether stem cells also exhibit sex differences in physiological function and hormonal regulation in tissues that do not exhibit sex-specific morphological differences. The terminal differentiation and function of some haematopoietic cells are regulated by sex hormones7-10 but haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function is thought to be similar in both sexes. Here we show that mouse HSCs exhibit sex differences in cell cycle regulation by estrogen. HSCs in females divide significantly more frequently than in males. This difference depended on the ovaries but not the testes. Administration of estradiol, a hormone produced mainly in the ovaries, increased HSC cell division in males and females. Estrogen levels increased during pregnancy, increasing HSC division, HSC frequency, cellularity, and erythropoiesis in the spleen. HSCs expressed high levels of estrogen receptor α (ERα). Conditional deletion of ERα from HSCs reduced HSC division in female, but not male, mice and attenuated the increases in HSC division, HSC frequency, and erythropoiesis during pregnancy. Estrogen/ERα signaling promotes HSC self-renewal, expanding splenic HSCs and erythropoiesis during pregnancy.

A fundamental question in stem cell biology concerns the extent to which stem cells are regulated by long-range signals to ensure that stem cell function within individual tissues is integrated with the overall physiological state11. For example, stem cells in the intestine, central nervous system, and germline are regulated by insulin and nutritional status12-17. Among haematopoietic cells estrogen regulates proliferation, survival, differentiation, and cytokine production by lymphoid and myeloid cells10,18,19 and induces apoptosis in erythroid cells by inhibiting Gata-120,21. This raises the question of whether sex hormones also regulate HSCs.

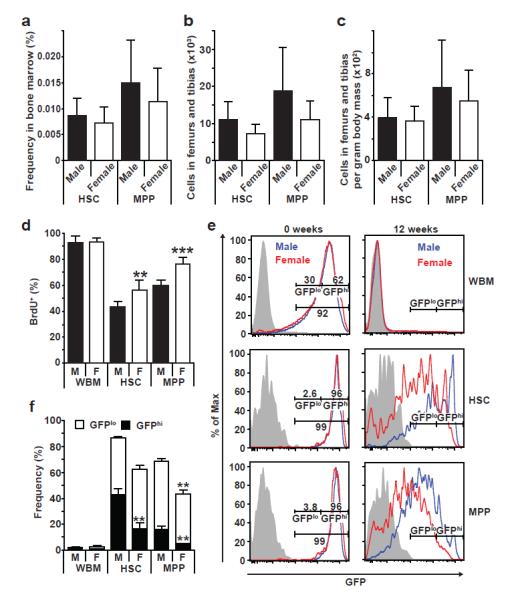

Comparing 8-10 week old male and female mice, we observed no significant differences in the frequency (Fig. 1a) or total numbers (Fig. 1b, c) of CD150+CD48−Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+ HSCs or CD150−CD48−Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+ multipotent progenitors (MPPs)22, or in the percentage of bone marrow cells that incorporated a 10 day pulse of BrdU (Fig. 1d). However, a significantly higher percentage of HSCs and MPPs incorporated BrdU in female as compared to male mice (Fig. 1d). Since the HSCs had incorporated BrdU while remaining in the HSC pool, HSCs undergo more frequent self-renewing divisions in female as compared to male mice.

Figure 1. HSCs divide more frequently in female as compared to male mice.

a-c, The frequency of HSCs and MPPs in the bone marrow (a), the total numbers of HSCs and MPPs in two femurs and tibias (b), and the numbers of HSCs and MPPs per gram of body mass (c) did not differ between young adult male and female mice. d, BrdU incorporation into whole bone marrow (WBM) cells, HSCs, and MPPs during a 10 day pulse (a-d, n=5 mice/group in 5 independent experiments). e, H2B-GFP intensity immediately after a 6-week pulse of doxycycline in Col1A1-H2B-GFP; Rosa26-M2-rtTA mice (left) or after a 12-week chase without doxycycline (right). f, The percentages of WBM cells, HSCs, and MPPs that retained H2B-GFP (4 males and 3 females in 3 independent experiments). All data represent mean±standard deviation; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; and ***, p<0.0005 by Student’s t-test.

To test this using an independent approach we treated 4-6 week old Rosa26-rtTA; tetO-H2B-GFP mice23 with doxycycline for 6 weeks to induce histone H2B-GFP expression and then chased for 12 weeks without doxycycline to assess the rate of H2B-GFP dilution as a result of cell division. After 6 weeks of doxycycline, HSCs, MPPs, and WBM cells in male and female mice were strongly and uniformly labeled with H2B-GFP (Fig. 1e). However, after the 12-week chase almost all bone marrow cells lost H2B-GFP expression in male and female mice (Fig. 1e, f). As expected23,24, HSCs and MPPs retained substantial frequencies of H2B-GFPhi cells that were relatively quiescent during the chase period (Fig. 1e, f). Consistent with the higher rate of BrdU incorporation in female HSCs, significantly (p<0.005) lower percentages of HSCs and MPPs retained high levels of H2B-GFP in female as compared to male mice (Fig. 1e, f). HSCs and MPPs thus divide more frequently in female as compared to male mice.

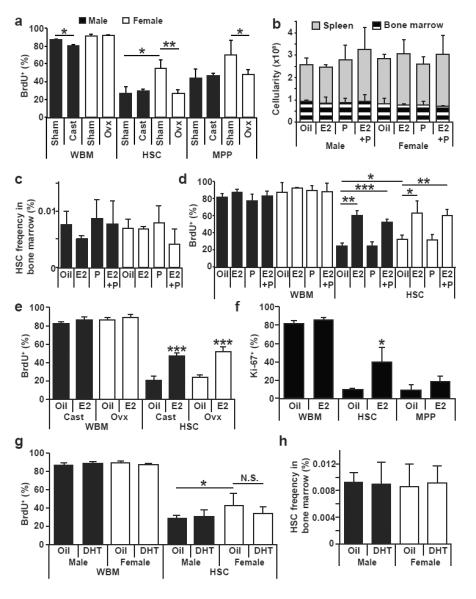

Ovariectomy, but not castration, significantly reduced the percentage of HSCs and MPPs that incorporated a 10-day pulse of BrdU (Fig. 2a). Indeed, ovariectomy reduced HSC and MPP division in females to male levels (Fig. 2a). Castration or ovariectomy did not affect the numbers of HSCs or MPPs in the bone marrow (Extended Data Fig. 1a) and produced only minor changes in the gross lineage composition of bone marrow cells (Extended Data Fig. 1b). The rate of HSC division in female mice is therefore increased by signals from the ovary.

Figure 2. Increased HSC division in female mice depends upon the ovaries and is stimulated by estradiol.

a, Effect of castration or ovariectomy on the rates of division by WBM cells, HSCs, or MPPs (3 sham and 4 gonadectomized mice in 3 independent experiments). b, c, Administering estradiol (E2), progesterone (P), or both (E2+P) for 1 week did not affect the number of bone marrow cells or splenocytes (b), or HSC frequency in bone marrow (c). d, Administering E2 or E2+P significantly increased HSC division in male and female mice (b-d, n=3 mice/treatment in 3 independent experiments). e, f, Administering E2 to castrated or ovariectomized mice significantly increased HSC division by BrdU incorporation (e, n=5) or Ki-67 staining (f, n=3). g,h, Administering dihydrotestosterone (DHT) for 7 days did not affect HSC division or HSC frequency (n=4 mice/treatment in 4 independent experiments). Data represent mean±standard deviation; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; and ***, p<0.0005 by Student’s t-test.

To test whether female sex hormones can affect HSC cycling we administered estradiol (E2; 2μg/day), progesterone (P; 1mg/day)5, or estradiol with progesterone (E2+P) to young adult male and female mice for 1 week along with BrdU for the last 3 days. This significantly increased estrogen and/or progesterone levels in both male and female mice (Extended Data Fig. 3a, b) without exceeding the physiological levels observed during pregnancy (Fig. 4e). These treatments did not affect bone marrow or spleen cellularity (Fig. 2b) or HSC frequency (Fig. 2c) but E2 induced erythropoiesis in the spleen (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Treatment with E2 or E2+P, but not P alone, significantly increased BrdU incorporation by HSCs, but not unfractionated bone marrow cells, in both male and female mice (Fig. 2d).

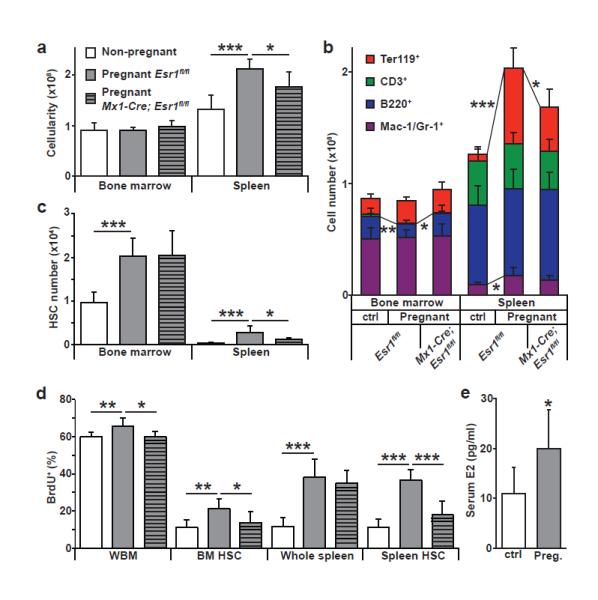

Figure 4. Increased HSC division, HSC frequency, and erythropoiesis in the spleen during pregnancy depend upon ERα signaling in haematopoietic cells.

a, Spleen and bone marrow cellularity. Pregnant mice were between days 12 and 15 of gestation. b, Pregnant mice had significantly increased Mac-1/Gr-1+ myeloid cells, Ter119+ erythroid cells, and overall cellularity in the spleen, but reduced bone marrow B220+ B-cells. The increase in splenic erythropoiesis required ERα expression by haematopoietic cells. c, HSC frequency in the bone marrow and spleen. d. In pregnant mice the rate of BrdU incorporation (24-hour pulse) significantly increased in whole bone marrow (WBM) cells, bone marrow HSCs, and spleen HSCs and depended upon ERα expression by haematopoietic cells (a-d, 9 non-pregnant, 7 pregnant Esr1fl/fl, and 6 pregnant Mx1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice in 9 independent experiments). e, Serum E2 levels in mice (21 non-pregnant and 9 pregnant mice from 6 independent experiments). All data represent mean±standard deviation; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; and ***, p<0.0005 by Student’s t-test.

E2 treatment increased BrdU incorporation by HSCs in castrated and ovariectomized mice, indicating that E2 acts independently of the gonads (Fig. 2e). E2 treatment also increased the frequency of Ki-67+ HSCs (Fig. 2f; Extended Data Fig. 4a). E2 treatment significantly reduced the frequency of HSCs that retained H2B-GFP in Rosa26-rtTA; tetO-H2B-GFP mice (Extended Data Fig. 4b-c). In contrast, treatment with dihydrotestosterone did not affect BrdU incorporation by male or female HSCs (Fig. 2g) or HSC frequency in bone marrow (Fig. 2h).

Consistent with the observation that estrogen induces apoptosis in erythroid progenitors20, we observed an increased frequency of Annexin-V+Ter119+ cells in female as compared to male bone marrow (Extended Data Fig. 5a). This appeared to be offset by increased generation of megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) in female mice (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Neither MEPs nor Ter119+ cells exhibited differences in cell cycle distribution between males and females (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Given that MEPs may arise directly from the asymmetric division of HSCs25 these observations raise the possibility that the increased frequency of MEPs in female mice reflects increased asymmetric self-renewal of female HSCs in response to estrogen.

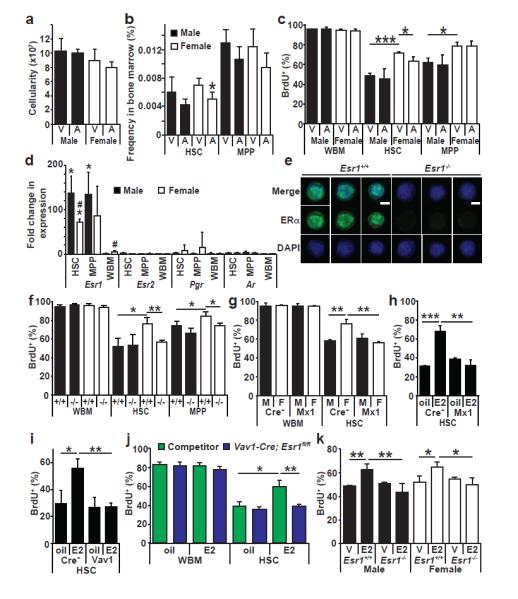

We treated mice for 14 days with the aromatase inhibitor, anastrozole, which reduces estrogen levels26. Anastrozole did not significantly affect bone marrow cellularity (Fig. 3a) or lineage composition (Extended Data Fig. 6a), but slightly reduced HSC frequency in female mice (Fig. 3b). Anastrozole did not significantly affect BrdU incorporation (during the last 10 days of anastrozole) by whole bone marrow cells or MPPs in male or female mice, but did significantly reduce BrdU incorporation by female HSCs (p<0.05, Fig. 3c). Treatment with the progesterone receptor antagonist RU486 had no effect on bone marrow or spleen cellularity, HSC frequency, or BrdU incorporation (Extended Data Fig. 3d-f). These results suggested that endogenous estrogen increases HSC division in female mice.

Figure 3. Estradiol-ERα signaling promotes HSC division in female mice.

a, b, Bone marrow cellularity (a), HSC, and MPP frequency (b) in mice administered the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole (A) or vehicle (PBS, abbreviated V) for 2 weeks. c, BrdU incorporation (10 day pulse) by WBM cells, HSCs, or MPPs in male or female mice treated with anastrozole or vehicle (a-c, 4 PBS treated and 6 anastrozole treated mice in 4 independent experiments). d, qRT-PCR revealed that HSCs and MPPs from female and male mice expressed greatly elevated levels of Esr1 (which encodes ERα) but not Esr2 (ERβ), Pgr (progesterone receptor), or Ar (androgen receptor) relative to male WBM (*, p<0.05 between HSC/MPP and WBM; #, p<0.05 between male and female.). Expression levels were normalized to β-actin. e, Immunofluorescence for ERα in HSCs (d,e, n=3 mice from 3 experiments. Scale bar, 4 μm). f, BrdU incorporation (10-day pulse) by WBM cells, HSCs, and MPPs in male and female mice (−/−, Esr1-deficient; +/+, littermate controls, f-h, n=3 mice/group in 3 independent experiments). g, Conditional deletion of Esr1 in female Mx1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice reduced BrdU incorporation into HSCs (Cre−, Esr1fl/fl; Mx1, Mx1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl, n=3). h, i, Conditional deletion of Esr1 in male Mx1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice (h) or Vav1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice (i) rendered HSCs insensitive to exogenous estrogen (h, i, n=3 mice/group in 2 independent experiments). j, E2 treatment of mice competitively reconstituted with WBM cells from wild-type and Vav1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice increased BrdU incorporation by wild-type HSCs but not Esr1-deficient HSCs (3 oil-treated and 4 E2-treated mice in 2 independent experiments). k, Effect of E2 on HSCs freshly added to culture (serum-free, phenol red-free medium with E2 or vehicle for three days; BrdU for one hour; n=3 mice in 2 independent experiments). All data represent mean±standard deviation; * and #, p<0.05; ** and ##, p<0.005; and *** and ###, p<0.0005 by Student’s t-test.

HSCs and MPPs from male and female mice expressed high levels of estrogen receptor α (ERα; encoded by Esr1) (Fig. 3d, e). However, HSCs expressed little or no ERβ (encoded by Esr2), progesterone receptor (Pgr), or androgen receptor (Ar) (Fig. 3d). To assess the roles of ERα and ERβ in HSC regulation we treated male mice with the ERα agonist propylpyrazoletriol (PPT) or the ERβ agonist diarylpropionitrile (DPN)27 for two weeks along with BrdU for the last 10 days. PPT and DPN did not affect bone marrow or spleen cellularity, or the frequencies of HSCs and MPPs (Extended Data Fig. 7a, b). PPT, but not DPN, significantly increased erythropoiesis in the bone marrow and spleen (Extended Data Fig. 7c) as well as BrdU incorporation by HSCs (Extended Data Fig. 7d) suggesting estrogen effects on HSCs are mediated mainly by ERα. Consistent with this conclusion, germline Esr1 deficient mice of both sexes had normal bone marrow cellularity and lineage composition (Extended Data Fig. 6b, d), as well as normal HSC and MPP frequency (Extended Data Fig. 6c) but significantly reduced BrdU incorporation into HSCs in female but not male mice (Fig. 3f).

To test whether ERα acts autonomously in HSCs we conditionally deleted Esr1 from haematopoietic cells. Mx1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice and Esr1fl/fl controls were treated with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (pIpC; four doses of 10μg/20g body mass/day over 8 days) to induce Mx1-Cre expression then 19-21 days after pIpC treatment we pulsed with BrdU for 10 days. Conditional deletion of Esr1 from haematopoietic cells significantly reduced BrdU incorporation into HSCs in female, but not male, mice (Fig. 3g).

Seven days of E2 significantly increased BrdU incorporation (3 day pulse) by HSCs from Esr1fl/fl controls but not Mx1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice (Fig. 3h). Similar results were obtained using Vav1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice (Fig. 3i), suggesting that Esr1-deficient HSCs are not capable of responding to exogenous estrogen.

To test whether E2 acts directly on HSCs, we competitively transplanted 106 CD45.2+ Vav1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl bone marrow cells along with 106 CD45.1+ bone marrow cells into irradiated mice. Fifteen weeks later we treated the mice with either E2 or vehicle for 7 days along with BrdU for the last three days. E2 treatment did not significantly affect BrdU incorporation by wild-type or Esr1-deficient bone marrow cells (Fig. 3j). E2 treatment did significantly increase BrdU incorporation by wild-type HSCs but not by Esr1-deficient HSCs in the same mice (Fig. 3j). This demonstrates that E2 acts directly on HSCs, rather than acting indirectly by stimulating secondary signals from other haematopoietic cells. Consistent with this, addition of E2 to cultured HSCs significantly increased BrdU incorporation by wild-type HSCs from male and female mice but not Esr1-deficient HSCs (Fig. 3k).

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) revealed significant enrichments of cell cycle genes and genes with E2F1 motifs in HSCs from mice treated with E2 for a week (Extended Data Fig. 8a, b). ERα signaling may therefore promote HSC division by activating E2Fs.

Estrogen levels increase in females during ovulation and pregnancy28. Relative to normal female mice, pregnant mice exhibited significantly increased cellularity, erythropoiesis, and myelopoiesis in the spleen (Fig. 4a, b) as well as more HSCs in the bone marrow and spleen (Fig. 4c). A 24-hour pulse of BrdU to pregnant mothers on day 13.5 of gestation revealed significant increases in proliferation among HSCs, whole bone marrow cells, and splenocytes in pregnant as compared to normal female mice (Fig. 4d). As expected28, serum E2 levels increased significantly in pregnant as compared to control mice (Fig. 4e).

Deletion of Esr1 from haematopoietic cells in Mx1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice significantly reduced cellularity (Fig. 4a), erythropoiesis (Fig. 4b), and HSC numbers (Fig. 4c) in the spleens of pregnant mice relative to pregnant Esr1fl/fl controls. Deletion of Esr1 from haematopoietic cells also significantly reduced BrdU incorporation into HSCs in the bone marrow and spleen of pregnant mice (Fig. 4d). Esr1 deletion from haematopoietic cells in pregnant mice did not block the increase in HSC frequency in the bone marrow but nearly eliminated the increase in HSC frequency in the spleen (Fig. 4c). This indicates that estrogen is not the only factor that increases HSC activity in pregnant mice but that it is critical for the mobilization of proliferating HSCs to the spleen and for the expansion of splenic erythropoiesis.

The increase in spleen cellularity and erythropoiesis during pregnancy may also occur in humans, which exhibit increased spleen size during pregnancy29,30. There may be many unexplored mechanisms by which systemic signals modulate the function of stem cells within individual tissues in response to physiological change.

METHOD SUMMARY

Specific mouse alleles used in this study are referenced in full Methods. Mice were housed in AAALAC-accredited, specific-pathogen-free animal care facilities at the University of Michigan (UM), Baylor College of Medicine (BCM), or UT Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW). All procedures were approved by the UM, BCM, and UTSW Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. For hormonal treatment, mice were injected subcutaneously with 100 μl of corn oil containing 2 μg estradiol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 1 mg progesterone (Sigma)5, or 100 μg of dihydrotestosterone (Steraloids, Newport, RI). 50 μg of anastrozole (Sigma) dissolved in PBS was given intraperitoneally. RU486, PPT, and DPN (all from Sigma) dissolved in corn oil were administered subcutaneously at 5mgkg−1. pIpC (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) was resuspended in PBS at 50 μg/ml, and 0.5 μg/gram of body mass were injected intraperitoneally every other day for 6 days. Females were mated with male mice one week after the last injection.

METHODS

Mice

The mouse alleles used in this study were Rosa26-rtTA/tetO-H2B-GFP (ref23), germline Esr1-deficient32, Mx1-Cre33, Vav1-Cre34, and Esr1fl (ref35). Most studies of HSC frequency and cycling employed young adult C57BL/Ka-Thy-1.1 (CD45.2) mice (8-12 weeks of age). C57BL/Ka-Thy-1.2 (CD45.1) mice were used in transplantation experiments. Mice were housed in AAALAC-accredited, specific-pathogen-free animal care facilities at the University of Michigan (UM), at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM), or UT Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW). All procedures were approved by the UM, BCM, and UTSW Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Hormone and pIpC treatments

Mice were injected subcutaneously with 100 μl of corn oil containing 2 μg estradiol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and/or 1 mg progesterone (Sigma)5. 100 μg of dihydrotestosterone (Steraloids, Newport, RI) in corn oil was administered subcutaneously31. 50 μg of anastrozole (Sigma) dissolved in PBS was given intraperitoneally. RU486, PPT, and DPN (all from Sigma) dissolved in corn oil were administered subcutaneously at 5mgkg−1. pIpC (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) was resuspended in PBS at 50 μg/ml, and mice were injected intraperitoneally (IP) with 0.5 μg/gram of body mass every other day for 6 days. Note that the biological effect of pIpC varies with polymer length and manufacturer such that doses must be optimized with each batch to obtain complete recombination without inducing HSC cycling. Females were mated with male mice one week after the last injection.

Statistical Methods

Multiple independent experiments were performed to verify the reproducibility of all experimental findings. Group data always represent mean±standard deviation. Unless otherwise indicated, two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to assess statistical significance. No randomization or blinding was used in any experiments. Experimental mice were not excluded from analysis in any experiments. Sample sizes were selected based upon prior experience with the degree of variance in each assay.

Cell cycle analysis

BrdU incorporation in vivo was measured by flow-cytometry using the APC BrdU Flow Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg of BrdU (Sigma) per 6 g of body mass in PBS and maintained on 1 mg/ml BrdU in the drinking water for up to 10 days.

Flow-cytometry and HSC isolation

Bone marrow cells were either flushed from the long bones (tibias and femurs) or isolated by crushing the long bones (tibias and femurs), pelvic bones, and vertebrae with mortar and pestle in Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS) without calcium and magnesium, supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated bovine serum (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). Cells were triturated and filtered through nylon screen (100 μm, Sefar America, Kansas City, MO) or a 40μm cell strainer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) to obtain a single-cell suspension. For isolation of CD150+CD48−Lineage−Sca-1+c-kit+ HSCs, bone marrow cells were incubated with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2; BioLegend, San Diego, CA), PE-conjugated anti-CD48 (HM48-1; BioLegend), APC-conjugated anti-Sca-1 (Ly6A/E; E13-6.7), and biotin-conjugated anti-c-kit (2B8) antibody, in addition to antibodies against the following FITC-conjugated lineage markers: CD41 (MWReg30; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), Ter119, B220 (6B2), Gr-1 (8C5), CD2 (RM2-5), CD3 (KT31.1) and CD8 (53-6.7). For isolation of CD34−CD16/32−Lineage−Sca-1-c-kit+ MEPs, CD34+CD16/32−Lineage−Sca-1−c-kit+ CMPs, and CD34+CD16/32−Lineage−Sca-1−c-kit+ GMPs, bone marrow cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-CD34 (RAM34; eBiosciences, San Diego, CA), PE-Cy7 conjugated anti-CD16/32 (93; Biolegend), PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-Sca-1 (Ly6A/E; E13-6.7), and biotin-conjugated anti-c-kit (2B8) antibody, in addition to antibodies against the following PE-conjugated lineage markers: Ter119, B220 (6B2), Gr-1 (8C5), Mac-1 (M1/70), CD2 (RM2-5), CD3 (KT31.1) and CD8 (53-6.7). For isolation of Flt3+IL-7R+Lineage−Sca-1loc-kitlo CLPs, bone marrow cells were incubated with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-Flt3 (A2F10; eBiosciences), PE-conjugated anti-IL-7R (A7R34; eBiosciences), PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-Sca-1 (Ly6A/E; E13-6.7), and biotin-conjugated anti-c-kit (2B8) antibody, in addition to antibodies against the following FITC-conjugated lineage markers: Ter119, B220 (6B2), Gr-1 (8C5), Mac-1 (M1/70), CD2 (RM2-5), CD3 (KT31.1) and CD8 (53-6.7). Unless otherwise noted, antibodies were obtained from BioLegend, BD Biosciences, or eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Biotin-conjugated antibodies were visualized using streptavidin-conjugated APC-Cy7. HSCs were sometimes pre-enriched by selecting c-kit+ cells using paramagnetic microbeads and autoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Nonviable cells were excluded from sorts and analyses using the viability dye 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1 μg/ml). To analyze BrdU incorporation into HSCs, bone marrow cells were incubated with PE-conjugated anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2), FITC-conjugated anti-CD48 (HM48-1), PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-Sca-1 (Ly6A/E; E13-6.7), and biotin-conjugated anti-c-kit (2B8) antibody, in addition to antibodies against the following FITC-conjugated lineage markers: CD41 (MWReg30), Ter119, B220 (6B2), Gr-1 (8C5), CD2 (RM2-5), CD3 (KT31.1) and CD8 (53-6.7). Biotin-conjugated c-kit was visualized using streptavidin-conjugated AlexaFluor 700 or PE-Cy7 (Invitrogen). To distinguish donor HSCs from recipient HSCs, AlexaFluor 700 conjugated anti-CD45.2 (clone 104) antibody was used. To analyze haematopoietic lineage composition, bone marrow cells or splenocytes were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-B220, PE-conjugated anti-Ter119, APC-conjugated anti-CD3, APC-eFluor780-conjugated anti-Mac-1 (M1/70), and PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-Gr-1 antibodies. Annexin-V staining was performed using Annexin-V APC (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry was performed with FACSAria II, FACSCanto II, LSR II, or LSRFortessa flow-cytometers (BD Biosciences).

Ki-67 staining

Ki-67 staining was performed as before36. In brief, HSCs were sorted into 70% ethanol and kept at −20°C for at least 24 hours. Ki-67 staining was performed using a FITC Ki-67 kit (BD Biosciences), followed by staining with 50μg/ml propidium iodide (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and analyzed by flow-cytometry.

Castration

An incision was made in the scrotum and the testis and attached testicular fat pad were pulled out of the incision. Spermatochords were individually ligated with absorbable sutures (4-0 chromic gut), then excised, and then 1-3 non-absorbable sutures (3-0 Tevdek II) were used to close the skin.

Ovariectomy

The skin around the dorsal midline caudal to the posterior borders of the ribs was shaved and an incision was made to expose the ovaries on each side. The ovaries were isolated, ligated with absorbable sutures (4-0 chromic gut) and excised, and then 3-4 non-absorbable sutures (3-0 Tevdek II) were used to close the skin. Sham treated animals underwent similar surgeries except that the gonads were left intact. All animals were allowed to recover for two weeks before BrdU was administered.

Cell cycle analysis of HSCs from competitively reconstituted mice

Adult recipient mice (CD45.1) were irradiated with an X-ray source delivering approximately 300 rad/min in two equal doses of 540 rad, delivered at least 2 hours apart. 106 whole bone marrow cells from CD45.2 Vav1-Cre; Esr1fl/fl mice were transplanted along with 106 CD45.1 whole bone marrow cells from wild-type mice into the retro-orbital venous sinus of anesthetized recipients. Fifteen weeks after transplantation, recipient mice were either treated with oil or 2 μg estradiol for 7 days. Mice were administered BrdU continuously for the last three days of estradiol treatment. BrdU incorporation into HSCs was analyzed by flow cytometry as described above.

Measurement of serum hormone concentration

Whole blood samples were collected and allowed to clot at room temperature for 90 minutes before being centrifuged at 2000 × g for 15 minutes at room temperature. Serum samples were analyzed for estradiol and progesterone levels at the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction.

Quantitative real-time (reverse transcription) PCR

HSCs and other haematopoietic cells were sorted into Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was made with random primers and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). Quantitative PCR was performed using a LightCycler 480 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) or ViiA7 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). Each sample was normalized to β-actin. Primers to quantify cDNA levels were Esr1 F, 5'- CCTTCTAGACCCTTCAGTGAAGCC-3', Esr1 R, 5'- CGAGACCAATCATCAGAATCTCC-3', Esr2 F, 5’- CCAGCCCTGTTACTAGTCCAAGC-3’, Esr2 R, 5’- GGTACACTGATTCGTGGCTGG-3’, Pgr F, 5’- CCAGCTCACAGCGCTTCTACC-3’, Pgr R, 5’- GAAAGAGGAGCGGCTTCACC-3’, Ar F, 5’- GGTGTGTGCCGGACATGACAAC-3’, Ar R, 5’- GGTCATCCACATGCAAGTTGCGG-3’, β-actin F, 5’- CGTCGACAACGGCTCCGGCATG-3' and β-actin R, 5’- GGGCCTCGTCACCCACATAGGAG-3'.

Microarray analysis

Groups of three male and three female mice were treated with either E2 (2μg/day) or vehicle (oil) for one week. HSCs were sorted into Trizol and RNA purified according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNase I treated RNA samples were amplified and biotinylated using the Nugen Ovation Pico WTA V2 system and the Encore Biotin Module (NuGEN Technologies, San Carlos, CA). Biotinylated samples were hybridized to Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) by the Baylor College of Medicine Genomic and RNA profiling core. dChip software37 was used to calculate normalized expression values for each array. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis was performed as described previously38.

HSC culture and in vitro BrdU incorporation

HSCs were sorted directly into serum free, phenol red free medium (X-Vivo 15, Lonza, Allendale, NJ) supplemented with 50 ng/ml of SCF and 50 ng/ml TPO (both from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), with or without 100 nM estradiol, and cultured for three days. BrdU (10 μM final concentration) was added for an hour before cells were cytospun to a slide. Slides were fixed with cold methanol for 5 minutes at −20 °C, then washed with PBS containing 0.01 % NP-40 and treated with 2N HCl for 15 minutes. Slides were blocked in PBS containing 4% goat serum, 4 mg/ml BSA, and 0.1% NP-40 followed by staining overnight at 4°C with antibody against BrdU (BU1/75, 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) as described previously36.

Immunostaining

Sorted HSCs were fixed with methanol and stained overnight at 4°C with antibodies against ERα (MC-20, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) diluted in PBS containing 4% goat serum, 4 mg/ml BSA and 0.1% NP-40. Primary antibody staining was developed with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa fluor 488 together with DAPI (2 μg/ml). Slides were analyzed on a Leica DMI6000 fluorescence microscope.

Extended data

Extended Data Figure 1. Castration or ovariectomy modestly increased the numbers of B cells in the bone marrow without affecting the numbers of HSCs or MPPs.

a, Castration (Cast) or ovariectomy (Ovx) did not significantly affect the numbers of HSCs or MPPs in the bone marrow (femurs and tibias). b, Castration or ovariectomy significantly increased the numbers of B220+ B-cells in the bone marrow but did not affect the numbers of Mac-1+/Gr-1+ myeloid cells, CD3+ T-cells, or Ter119+ erythroid cells in the bone marrow or spleen. 3 sham and 4 gonadectomized mice used in 3 independent experiments. All data represent mean±standard deviation; *, p<0.05 by Student’s t-test.

Extended Data Figure 2. Administration of estradiol (E2) to mice induced erythropoiesis in the spleen.

a, b, c, Treatment of male and female mice for 1 week with E2, with or without P, did not affect the numbers of Mac-1+/Gr-1+ myeloid cells, B220+ B-cells, or CD3+ T-cells in the bone marrow or spleen of either sex. d, E2 and E2+P treatment did significantly increase the number of Ter119+ erythroid cells in the spleen of male mice, and E2 treatment significantly increased the number of Ter119+ erythroid cells in the spleen of female mice. n=3 mice/treatment in 3 independent experiments. All data represent mean±standard deviation; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; and ***, p<0.0005 by Student’s t-test comparing each treatment to vehicle.

Extended Data Figure 3. Administration of exogenous estrogen and progesterone significantly increased serum estrogen and progesterone levels in mice but progesterone did not affect HSC division in vivo.

a, Estradiol treatment significantly increased serum estradiol levels in male and female mice but the increased levels remained within the physiological range, similar to levels observed during pregnancy (see Fig. 4e) (Male Oil; 22, male E2; 20, female oil; 33, female E2; 14 mice used in 8 independent experiments). b, Progesterone treatment significantly increased serum progesterone levels in male and female mice (n=3 mice/treatment in 3 independent experiments). Note that this did not affect bone marrow or spleen cellularity, HSC frequency, or HSC division (Fig. 2b-d). c, Esr1-deficient mice had normal levels of serum progesterone (n=3 mice/group in 3 independent experiments). d-f, Administration of a progesterone receptor antagonist, RU486 (RU), did not affect bone marrow or spleen cellularity (d), HSC frequency in the bone marrow (e), or the division of HSCs, MPPs, or WBM cells (f). All data represent mean±standard deviation from 3 independent experiments, except as indicated above; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; and ***, p<0.0005 by Student’s t-test comparing each treatment to vehicle (oil).

Extended Data Figure 4. Estrogen treatment increased the frequency of Ki-67+ cycling HSCs.

a, Administration of estrogen (E2) significantly increased the frequency of HSCs in G1 phase of the cell cycle, and reduced the frequency of HSCs in G0 phase of the cell cycle based on Ki-67/propidium iodide staining (n=3 mice/treatment in 3 independent experiments). b, c, Col1A1-H2B-GFP; Rosa26-M2-rtTA mice pulsed with doxycycline for 6-weeks to induce H2B-GFP expression were treated with oil (blue histogram) or E2 (red histogram) for 2-weeks without doxycycline. E2 treatment significantly increased the rate of HSC division as indicated by the reduced frequency of GFPhi quiescent HSCs and the increased the frequency of GFPlo moderately cycling HSCs (5 oil-treated and 4 E2-treated mice used in 3 independent experiments). All data represent mean±standard deviation; *, p<0.05 by Student’s t-test comparing each treatment to vehicle (oil).

Extended Data Figure 5. Female mice have increased frequencies of megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) and apoptotic Ter119+ cells relative to male mice.

a, Annexin-V staining of the indicated cell populations in the bone marrow of male and female mice revealed a significantly increased frequency of apoptotic Annexin-V+ cells among Ter119+ erythroid progenitors in female mice. b, Female mice had a significantly increased frequency of CD34−CD16/32−Lineage−Sca-1−c-kit+ MEPs, but no significant differences in the frequencies of CD34+CD16/32−Lineage−Sca-1-c-kit+ CMPs, CD34+CD16/32+Lineage−Sca-1-c-kit+ GMPs, or Flt3+IL-7R+Lineage−Sca-1loc-kitlo CLPs. c, None of the restricted progenitors or differentiated cells displayed differences in cell cycle status between male and female (a-c, n=5 mice/group in 3 independent experiments). Data represent mean±standard deviation; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; by Student’s t-test comparing each treatment between sexes.

Extended Data Figure 6. Inhibiting estrogen signaling by anastrozole treatment or Esr1 deficiency did not affect the numbers of haematopoietic cells in the bone marrow or spleen.

a, Administration of anastrozole (Ana) to mice for two weeks did not significantly affect the number of Ter119+ erythroid cells, CD3+ T-cells, B220+ B-cells, or Mac-1+/Gr-1+ myeloid cells in the bone marrow or spleen (4 PBS treated and 6 anastrozole treated mice were used in 4 independent experiments). b, c, Esr1 deficiency did not significantly affect bone marrow cellularity (b) or the frequencies of HSCs or MPPs (c) in either sex. d, Esr1 deficiency did not significantly affect the numbers of Ter119+ erythroid cells, CD3+ T-cells, B220+ B-cells, or Mac-1+/Gr-1+ myeloid cells in the bone marrow or spleen of normal mice. −/− indicates Esr1-deficient mice and +/+ indicates wild-type littermate control mice (b-d, n=3 mice/group in 3 independent experiments). All data represent mean±standard deviation.

Extended Data Figure 7. Pharmacological ERα activation, but not ERβ activation, is sufficient to promote HSC division.

Male mice (n=5 mice/treatment in 3 independent experiments) were treated with oil, ERα agonist PPT, or ERβ agonist DPN for 14 days then pulsed with BrdU for 10 days, beginning on the fourth day of hormone treatment. PPT or DPN treatment did not significantly affect the cellularity of bone marrow or spleen (a), or the frequencies of HSCs or MPPs in bone marrow (b). c, PPT treatment, but not DPN treatment, significantly increased erythropoiesis in bone marrow and spleen. d, PPT significantly increased the division rates of HSCs and MPPs, but DPN failed to do so, suggesting that ERα activation, but not ERβ activation, promotes HSC division. Data represent mean±standard deviation; ***, p<0.0005 by Student’s t-test comparing each treatment to vehicle (oil).

Extended Data Figure 8. E2 treatment changes HSC gene expression profile in a manner consistent with increased cell division.

a, b, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis revealed that HSCs from mice treated with E2 exhibited significant enrichment in the expression of genes involved in cell cycling (a). We also observed a significant enrichment in the expression of genes with E2F1 motifs in HSCs from E2-treated mice, consistent with the role of E2Fs in cell cycle control (b). n=3 mice/treatment of each sex were used to isolate independent aliquots of RNA from HSCs for gene expression profiling.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SJM is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator and the Mary McDermott Cook Chair in Pediatric Genetics. This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (awards to DN and SJM) and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (HL097760 to SJM). BPL was supported by an Irvington Institute-Cancer Research Institute/Edmond J. Safra Memorial Fellowship. Flow-cytometry was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (NCRR grant S10RR024574, NIAID AI036211 and NCI P30CA125123) for the BCM Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core. Thanks to JoAnne Richards, Shailaja Mani, and former member of Nakada lab for discussions. This work was initiated in the Life Sciences Institute at the University of Michigan then completed at Baylor College of Medicine and Children’s Research Institute at UT Southwestern. Thanks to the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction for measuring serum hormone levels. This work is dedicated to Nicole Ryan who passed away during the study.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.N., H.O., and B.P.L. designed and performed most experiments. G.R.W., A.K., Y.S., and M.T. performed some experiments with D.N.. D.N. and S.J.M. analyzed results and wrote the manuscript.

AUTHOR INFORMATION

Microarray data have been deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE52711). The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams TM, Carroll SB. Genetic and molecular insights into the development and evolution of sexual dimorphism. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10:797–804. doi: 10.1038/nrg2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy MM, Arnold AP. Reframing sexual differentiation of the brain. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14:677–683. doi: 10.1038/nn.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oatley JM, Brinster RL. Regulation of Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal in Mammals. Annual Reviews in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2008 doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asselin-Labat ML, et al. Control of mammary stem cell function by steroid hormone signalling. Nature. 2010;465:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature09027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi PA, et al. Progesterone induces adult mammary stem cell expansion. Nature. 2010;465:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature09091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shingo T, et al. Pregnancy-stimulated neurogenesis in the adult female forebrain mediated by prolactin. Science. 2003;299:117–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1076647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carreras E, et al. Estradiol acts directly on bone marrow myeloid progenitors to differentially regulate GM-CSF or Flt3 ligand-mediated dendritic cell differentiation. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180:727–738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thurmond TS, et al. Role of estrogen receptor alpha in hematopoietic stem cell development and B lymphocyte maturation in the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2309–2318. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.7.7560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medina KL, et al. Identification of very early lymphoid precursors in bone marrow and their regulation by estrogen. Nature Immunology. 2001;2:718–724. doi: 10.1038/90659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fish EN. The X-files in immunity: sex-based differences predispose immune responses. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2008;8:737–744. doi: 10.1038/nri2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakada D, Levi BP, Morrison SJ. Integrating physiological regulation with stem cell and tissue homeostasis. Neuron. 2011;70:703–718. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien LE, Soliman SS, Li X, Bilder D. Altered modes of stem cell division drive adaptive intestinal growth. Cell. 2011;147:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yilmaz OH, et al. mTORC1 in the Paneth cell niche couples intestinal stem-cell function to calorie intake. Nature. 2012;486:490–495. doi: 10.1038/nature11163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLeod CJ, Wang L, Wong C, Jones DL. Stem cell dynamics in response to nutrient availability. Current Biology : CB. 2010;20:2100–2105. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaFever L, Drummond-Barbosa D. Direct control of germline stem cell division and cyst growth by neural insulin in Drosophila. Science. 2005;309:1071–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.1111410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sousa-Nunes R, Yee LL, Gould AP. Fat cells reactivate quiescent neuroblasts via TOR and glial insulin relays in Drosophila. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature09867. doi:10.1038/nature09867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chell JM, Brand AH. Nutrition-responsive glia control exit of neural stem cells from quiescence. Cell. 2010;143:1161–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gourdy P, et al. Relevance of sexual dimorphism to regulatory T cells: estradiol promotes IFN-gamma production by invariant natural killer T cells. Blood. 2005;105:2415–2420. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghazeeri G, Abdullah L, Abbas O. Immunological differences in women compared with men: overview and contributing factors. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2011;66:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blobel GA, Orkin SH. Estrogen-induced apoptosis by inhibition of the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1687–1694. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blobel GA, Sieff CA, Orkin SH. Ligand-dependent repression of the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 by the estrogen receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3147–3153. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oguro H, Ding L, Morrison SJ. SLAM family markers resolve functionally distinct subpopulations of hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:102–116. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foudi A, et al. Analysis of histone 2B-GFP retention reveals slowly cycling hematopoietic stem cells. Nature Biotechnology. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nbt.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson A, et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cells Reversibly Switch from Dormancy to Self-Renewal during Homeostasis and Repair. Cell. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto R, et al. Clonal analysis unveils self-renewing lineage-restricted progenitors generated directly from hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 2013;154:1112–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wit JM, Hero M, Nunez SB. Aromatase inhibitors in pediatrics. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;8:135–147. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsson S, Koehler KF, Gustafsson JA. Development of subtype-selective oestrogen receptor-based therapeutics. Nature Reviews Drug discovery. 2011;10:778–792. doi: 10.1038/nrd3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahendroo MS, Cala KM, Landrum DP, Russell DW. Fetal death in mice lacking 5alpha-reductase type 1 caused by estrogen excess. Molecular Endocrinology. 1997;11:917–927. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.7.9933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan HL, Falkiner NM. Splenic aneurysm and splenic enlargement in pregnancy. British Medical Journal. 1948;2:1105. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4590.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maymon R, et al. Normal sonographic values of maternal spleen size throughout pregnancy. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1827–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

EXTENDED DATA REFERENCES

- 31.Azzi L, El-Alfy M, Martel C, Labrie F. Gender differences in mouse skin morphology and specific effects of sex steroids and dehydroepiandrosterone. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2005;124:22–27. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lubahn DB, et al. Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:11162–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kühn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 1995;269:1427–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7660125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Boer J, et al. Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. European journal of immunology. 2003;33:314–325. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng Y, Manka D, Wagner KU, Khan SA. Estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the mammary epithelium is required for ductal and alveolar morphogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14718–14723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706933104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakada D, Saunders TL, Morrison SJ. Lkb1 regulates cell cycle and energy metabolism in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2010;468:653–658. doi: 10.1038/nature09571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li C, Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]