Abstract

Background

An increase in serious adverse events with both regular formoterol and regular salmeterol in chronic asthma has been demonstrated in previous Cochrane reviews.

Objectives

We set out to compare the risks of mortality and non-fatal serious adverse events in trials which have randomised patients with chronic asthma to regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol.

Search methods

We identified trials using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials. We checked manufacturers’ websites of clinical trial registers for unpublished trial data and also checked Food and Drug Administration (FDA) submissions in relation to formoterol and salmeterol. The date of the most recent search was January 2012.

Selection criteria

We included controlled, parallel-design clinical trials on patients of any age and with any severity of asthma if they randomised patients to treatment with regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol (without randomised inhaled corticosteroids), and were of at least 12 weeks’ duration.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected trials for inclusion in the review and extracted outcome data. We sought unpublished data on mortality and serious adverse events from the sponsors and authors.

Main results

The review included four studies (involving 1116 adults and 156 children). All studies were open label and recruited patients who were already taking inhaled corticosteroids for their asthma, and all studies contributed data on serious adverse events. All studies compared formoterol 12 μg versus salmeterol 50 μg twice daily. The adult studies were all comparing Foradil Aerolizer with Serevent Diskus, and the children’s study compared Oxis Turbohaler to Serevent Accuhaler. There was only one death in an adult (which was unrelated to asthma) and none in children, and there were no significant differences in non-fatal serious adverse events comparing formoterol to salmeterol in adults (Peto odds ratio (OR) 0.77; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.46 to 1.28), or children (Peto OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.06 to 15.33). Over a six-month period, in studies involving adults that contributed to this analysis, the percentages with serious adverse events were 5.1% for formoterol and 6.4% for salmeterol; and over a three-month period the percentages of children with serious adverse events were 1.3% for formoterol and 1.3% for salmeterol.

Authors’ conclusions

We identified four studies comparing regular formoterol to regular salmeterol (without randomised inhaled corticosteroids, but all participants were on regular background inhaled corticosteroids). The events were infrequent and consequently too few patients have been studied to allow any firm conclusions to be drawn about the relative safety of formoterol and salmeterol. Asthma-related serious adverse events were rare and there were no reported asthma-related deaths.

BACKGROUND

When patients with asthma are not controlled by low-dose inhaled corticosteroids alone, many asthma guidelines recommend additional long-acting beta2-agonists. Several Cochrane reviews have addressed the efficacy of long-acting beta2-agonists in addition to inhaled corticosteroids (Ni Chroinin 2005; Ni Chroinin 2009), in comparison with placebo (Walters 2007), short-acting beta2-agonists (Walters 2002), leukotriene-receptor antagonists (Ducharme 2006) and increased doses of inhaled corticosteroids (Greenstone 2005). The beneficial effects of long-acting beta2-agonists on lung function, symptoms, quality of life and exacerbations requiring oral steroids have been demonstrated. The pharmacology of beta2-agonists is discussed in more detail in Appendix 1.

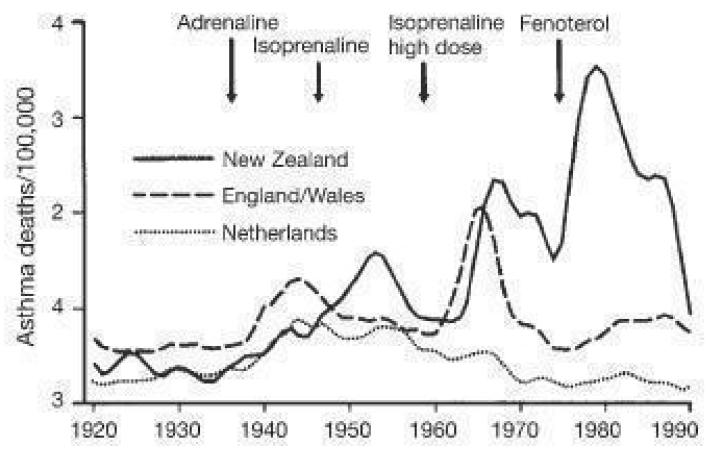

However, there is also longstanding controversy over the regular use of beta2-agonists in asthma. Sears 1986 suggested that excessive use of short-acting beta2-agonists might have contributed directly or indirectly to increases in asthma deaths in New Zealand between 1960 and 1980. The authors commented that “most deaths were associated with poor assessment, underestimation of severity and inappropriate treatment (over-reliance on bronchodilators and under use of systemic corticosteroids), and delays in obtaining help.”

Concern remains that the symptomatic benefit from treatment with long-acting beta2-agonists might lead to underestimation of attack severity in acute asthma, and could lead to an increase in asthma-related deaths (as seen in SMART 2006). Furthermore, regular treatment with beta2-agonists can lead to tolerance to their bronchodilator effects and this phenomenon may be more marked with longer-acting as opposed to shorter-acting compounds (Lipworth 1997). A number of molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain the possible detrimental effect of long-term beta2-agonist use in asthma, including desensitisation due to receptor down regulation with cellular internalisation (Giembycz 2006).

A recent systematic review of the effect of long-acting beta2-agonists on severe asthma exacerbations and asthma-related deaths (Salpeter 2006) concluded that “long-acting beta-agonists have been shown to increase severe and life-threatening asthma exacerbations, as well as asthma-related deaths”. Salpeter 2006 only considered trials that compared long-acting beta2-agonists with placebo, and the review was not able to include 28 trials in the primary analysis (including nearly 6000 patients) because information was not provided for asthma-related deaths.

Currently there are two long-acting beta2-agonists available, salmeterol and formoterol (also known as eformoterol). These two drugs are known to have differences in speed of onset and receptor activity, and are used in different ways. Salmeterol has a slower onset of action than formoterol and is not used as relief medication, whereas formoterol can be used for maintenance and relief of symptoms. Not all beta2-agonists carry the same risks, as pointed out in the book entitled ‘The Fenoterol Story’ (Pearce 2007). Appendix 2 discusses the possible mechanisms of increased asthma mortality with beta-agonists in more detail.

Two published reviews have assessed the risk of serious adverse events (SAEs) with regular salmeterol (Cates 2008) and formoterol (Cates 2008a) without randomised inhaled corticosteroids in comparison to placebo or short-acting beta2-agonists, and further reviews have compared regular formoterol and salmeterol when randomised with an inhaled corticosteroid (Cates 2009; Cates 2009a; Cates 2011; Jaeschke 2008; Jaeschke 2008a).

There is a need to systematically review all the available data from controlled trials that have compared patients randomised to regular formoterol or regular salmeterol without randomised inhaled corticosteroids, although it is likely that such patients in trials would already be prescribed background treatment with inhaled corticosteroids. We considered all SAEs (fatal and non-fatal), whether or not these were deemed by the investigators to be related to trial medication.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the risk of mortality and non-fatal SAEs in trials which have randomised patients with chronic asthma to regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised trials (RCTs) of parallel design, with or without blinding, in which patients with chronic asthma were randomly assigned to regular treatment with formoterol versus salmeterol. We excluded studies on acute asthma and exercise-induced bronchospasm.

Types of participants

We included patients with a clinical diagnosis of asthma of any age group, unrestricted by disease severity, previous or current treatment.

Types of interventions

We included trials that randomised patients to receive inhaled formoterol versus salmeterol given regularly for a period of at least 12 weeks, but not randomised with inhaled corticosteroids. We excluded studies that used adjustable maintenance dosing and single inhaler therapy (for maintenance and relief of symptoms).

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes were not subdivided according to whether the trial investigators considered them to be related to trial medication.

Primary outcomes

All-cause mortality

All-cause non-fatal SAEs

Secondary outcomes

Asthma-related mortality

Asthma-related non-fatal SAEs

Cardiovascular-related mortality

An illustrative example of the definition of SAEs used in trials by GlaxoSmithKline is shown in Appendix 3

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (please see Appendix 4 for further details). We searched all records in the Specialised Register coded as ‘asthma’ using the following terms: (salmeterol or serevent) AND (formoterol or eformoterol or oxis or foradil) AND (serious or safety or surveillance or mortality or death or intubat* or adverse or toxicity or complications or tolerability)

In addition we carried out a further search just using the terms: (salmeterol or serevent) AND (formoterol or eformoterol or oxis or foradil).

We conducted the latest searches in January 2012.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We also checked websites of clinical trial registers for unpublished trial data and checked FDA submissions in relation to formoterol.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Both review authors independently assessed studies identified in the literature searches by examining titles, abstract and keywords fields. We obtained studies that potentially fulfilled the inclusion criteria in full text. We independently assessed these full-text trial reports for inclusion. No disagreements occurred over the inclusion or exclusion of studies.

Data extraction and management

CJC extracted data using a prepared checklist and entered them into RevMan 5 (RevMan 2011). TL independently extracted the results. Data included characteristics of included studies (methods, participants, interventions, outcomes) and results of the included studies. We contacted authors and sponsors of included studies for unpublished adverse event data, and searched manufacturers’ websites for further details of adverse events. We also searched FDA submissions. We recorded all-cause SAEs (fatal and non-fatal) and, in view of the difficulty in deciding whether events are asthma-related, we noted details of the cause of death and SAEs where they were available. We also sought the definition of SAEs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

CJC assessed the included studies for bias protection (including sequence generation for randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and assessors, loss to follow-up, completeness of outcome assessment and other possible sources of bias), and this was independently verified by TL.

Unit of analysis issues

We extracted data using the number of participants who suffered one or more SAEs, in order to avoid double-counting events from the same participant.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity in the pooled odds ratio using the I2 statistic in RevMan 5 to indicate how much of the total heterogeneity found was between, rather than within, studies.

Data synthesis

The outcomes of this review were dichotomous and we recorded the number of participants with each outcome event by allocated treated group. We calculated pooled odds ratio (OR) and risk difference (RD). The Peto OR has advantages when events are rare, as no adjustment for zero cells is required. This property was found in previous reviews to be more important than potential problems with unbalanced treatment arms and large effect sizes, and we therefore calculated the results for SAEs in RevMan 5 using the Peto method with the Mantel-Haenszel method for sensitivity analysis. We could not use funnel plots to assess publication bias, as very few trials were identified.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to compare subgroups using tests for interaction (Altman 2003). However, events were too sparse to allow a meaningful comparison of the results in adults and children, and background non-randomised use of inhaled corticosteroids was used in all studies, so subgroup analysis by background inhaled corticosteroid use was not possible.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of the method used to combine the study events (risk difference, Peto OR and Mantel-Haenszel OR). The degree of bias protection in the study designs was part of planned sensitivity analysis, but all the studies were of open design and reporting of sequence generation and allocation concealment was poor.

RESULTS

Description of studies

Results of the search

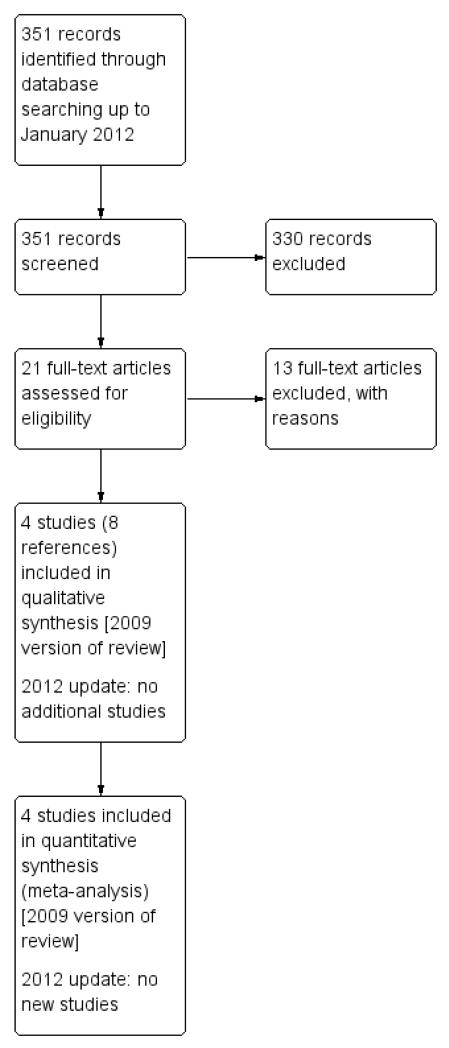

See Figure 1 for the study flow diagram. We carried out the original search in January 2009 and identified 40 references (155 references without the adverse event filter). We identified three studies for inclusion (Condemi 2001; Everden 2004; Vervloet 1998) from the shorter list of references. When this was rechecked against the unfiltered list we identified one further study (Gabbay 1998), which had been published in abstract form only in 1998, and found four further references related to the three included studies. We identified 13 further studies for possible inclusion, but we excluded them after more detailed inspection (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

We carried out an updated search in January 2012 but there were no new studies included.

Included studies

Of the four included studies, three enrolled a combined total of 1137 adults (Condemi 2001; Gabbay 1998; Vervloet 1998), and one enrolled 156 children (Everden 2004). Vervloet 1998 included adults with reversible airways obstruction, and whilst they did not seek to exclude participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), they indicated that most participants suffered from asthma, so both review authors independently decided that this study should be included.

All the studies compared a twice daily dose of formoterol 12 μg with twice daily salmeterol 50 μg. Condemi 2001, Gabbay 1998 and Vervloet 1998 compared the Foradil Aerolizer with Serevent Diskus inhaler devices, whilst Everden 2004 compared the Oxis Turbohaler with Serevent Accuhaler. Although none of the studies randomised patients to inhaled corticosteroids (in the form of combined inhalers), all four studies randomised patients who were already taking inhaled corticosteroids as background treatment. All the studies were multi-centre, open (i.e. unblinded), parallel-group design.

Condemi 2001, Gabbay 1998 and Vervloet 1998 were sponsored by Novartis (manufacturer of Foradil) and Everden 2004 was sponsored by AstraZeneca (manufacturer of Oxis).

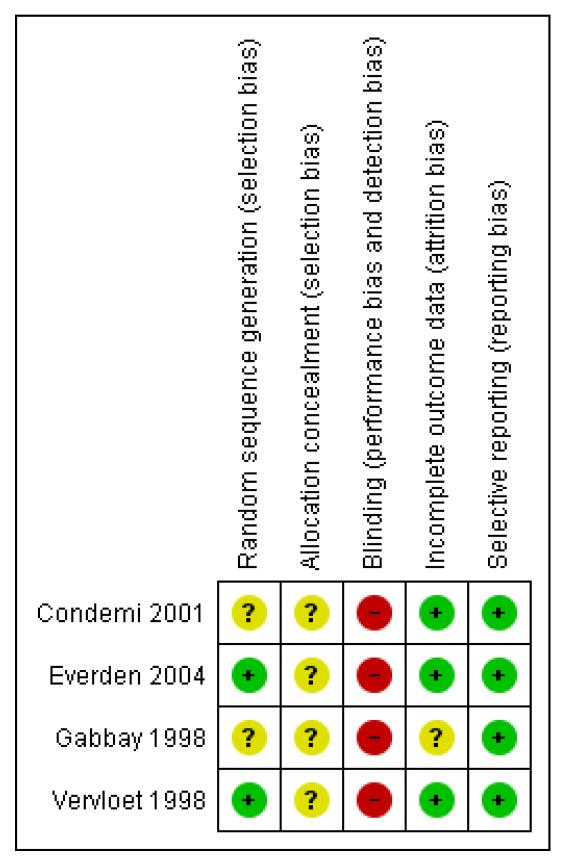

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Few details were available in relation to sequence generation or allocation concealment. As all the studies were sponsored by Novartis or AstraZeneca it is likely that they were adequately protected from the risk of selection bias.

Blinding

All the studies were open-label in design, so unprotected against performance bias. We remain uncertain as to the impact of this on the outcomes primarily of interest to this review.

Incomplete outcome data

The adult studies had low dropout rates, but the study in children had higher dropout rates and these were not balanced between the trial arms. Thirty-three out of 127 children discontinued the study (formoterol 21, salmeterol 12). All children who took at least one dose of medication were included in the analysis.

Selective reporting

No serious adverse event data were published in the abstract of Gabbay 1998, and no full publication has been identified after correspondence with the author, who was unable to offer further information. Vervloet 1998 also included information on all adverse events only, but no separate data on SAEs. Novartis have been able to provide data on file for SAEs in both of these studies. An overview of the risks of bias is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

All studies have contributed serious adverse event data to this review: Condemi 2001 (528 adults studied for six months) and Everden 2004 (156 children studies for three months) from published papers and Gabbay 1998 (127 adults for three months) and Vervloet 1998 (482 adults for six months) from data on file at Novartis.

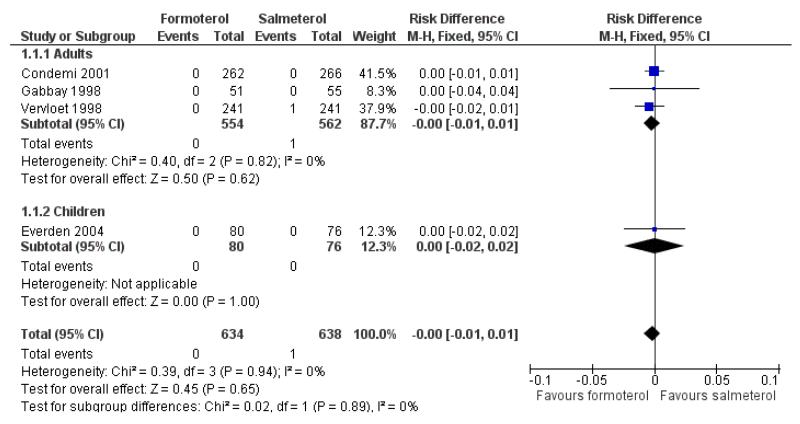

All-cause mortality

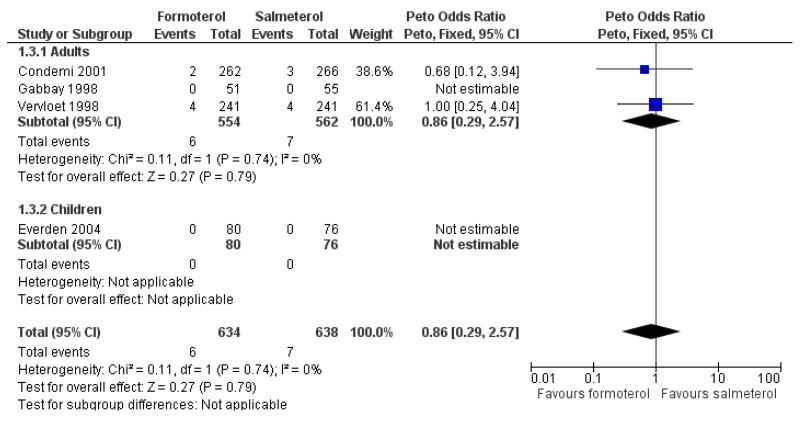

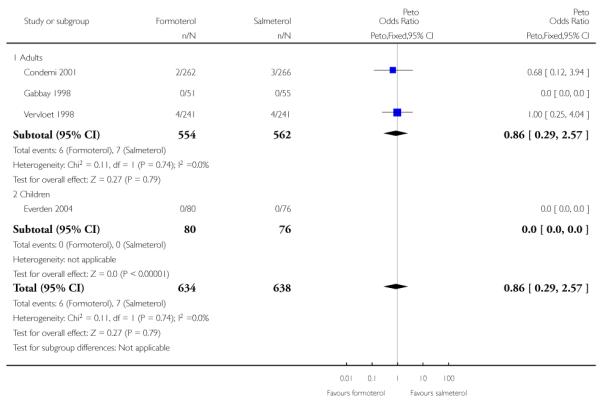

No deaths were reported in 528 adults in Condemi 2001. Novartis have confirmed that there were no deaths in Gabbay 1998, and in Vervloet 1998 there was one participant who died of heart disease following coronary surgery in the salmeterol group. AstraZeneca have confirmed that there were no deaths in the 156 children in Everden 2004. There are insufficient data to draw any firm conclusions in relation to mortality, but using the pooled risk difference (RD) to combine the results of studies, the overall risk difference in adults (RD −0.00; 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.01 to 0.01) and in children (RD 0.00; 95% CI −0.02 to 0.02) is as shown in Figure 3. This indicates that the maximum absolute difference between treatments in adults who have been studied is one percentage point either way, and in children is two percentage points either way. This range of uncertainty needs to be considered in the context of a mortality rate of 0.05% found in studies on formoterol alone (Cates 2008a).

Figure 3. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol, outcome: 1.1 All-cause mortality.

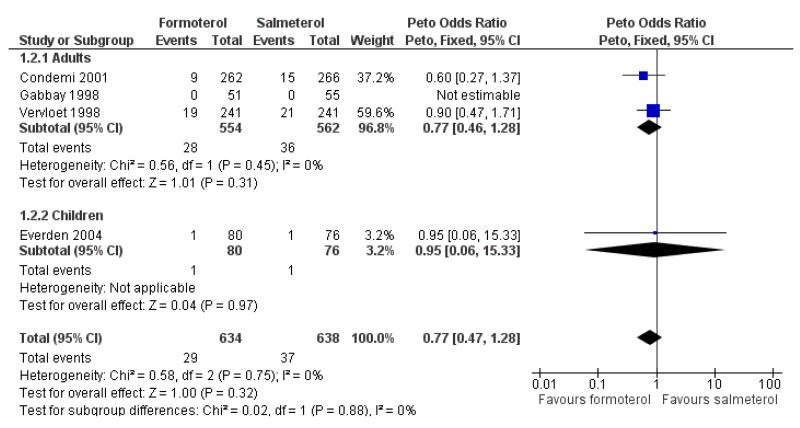

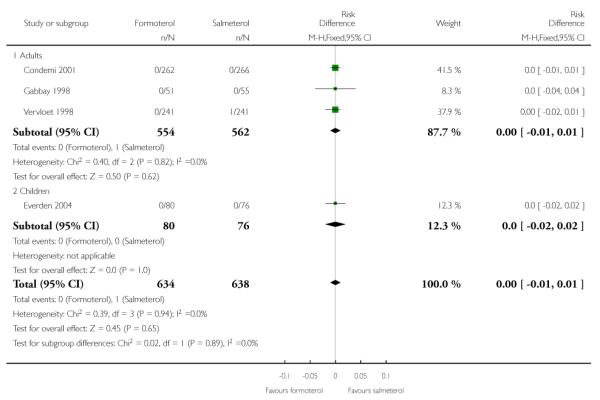

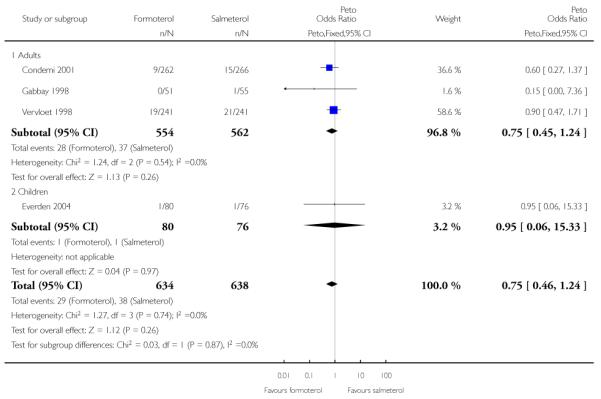

All-cause non-fatal serious adverse events (SAEs)

Adults

Condemi 2001 reported nine out of 262 adults having SAEs on formoterol and 15 out of 266 on salmeterol, and in Vervloet 1998 there were non-fatal SAEs in 19 of 241 adults on formoterol and 21 out of 241 adults on salmeterol (Novartis data on file). Gabbay 1998 recorded only one patient with a serious adverse event (an asthma exacerbation); the patient was not included in the safety analysis for this trial as it could not be confirmed that any of the study drug (salmeterol) had been taken. The Peto odds ratio (OR) comparing formoterol to salmeterol was not significantly different between groups (Peto OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.46 to 1.28 (Figure 4)), nor was the risk difference (RD −0.01; 95% CI −0.04 to 0.01). Over the six-month period for adults that contributed to this analysis the percentages of adults with SAEs were formoterol 5.1% and salmeterol 6.4%.

Figure 4. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol, outcome: 1.2 All-cause SAEs.

We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the addition of the patient from Gabbay 1998 and this gave very similar results (Peto OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.24). The OR was also virtually unchanged using Mantel-Haenszel random (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.46 to 1.29) or fixed method (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.46 to 1.28).

Children

Everden 2004 reported one out of 80 children experiencing SAEs on formoterol and one out of 76 children on salmeterol. Over the three-month period the percentages of children with SAEs were formoterol 1.3% and salmeterol 1.3%. The Peto OR was not significantly different between groups (Peto OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.06 to 15.52), nor was the risk difference (RD −0.0005; 95% CI −0.04 to 0.04).

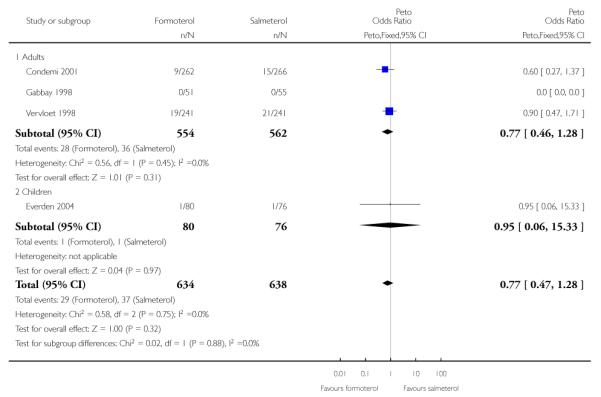

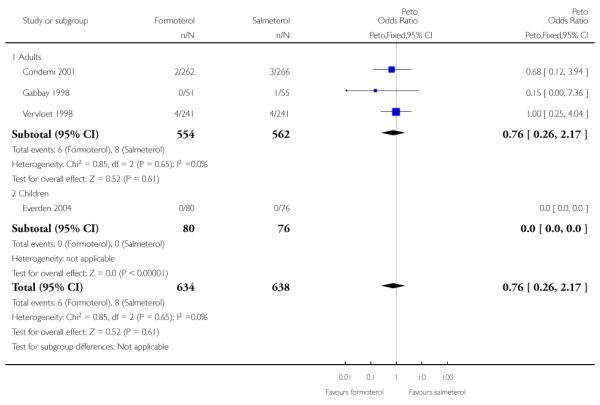

Asthma-related SAEs

Adults

Of all the SAEs reported in Condemi 2001, two adults on formoterol and three adults on salmeterol were classified as having events related to asthma. In Vervloet 1998 there were four adults in each group with events related to asthma. Again there is no significant difference between the treatment groups (Peto OR 0.86; 95% CI 0.29 to 2.57 (Figure 5)).

Figure 5. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol, outcome: 1.3 Asthma-related SAEs.

Sensitivity analysis to include the additional patient in Gabbay 1998 again gave very similar pooled results (Peto OR 0.76; 95% CI 0.26 to 2.17).

Children

Neither of the SAEs in children in Everden 2004 were asthma-related.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

We identified only three studies involving adults (N = 1116) and one study in children (N = 155) for inclusion in this review. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were rare, especially those related to asthma. Only one non-asthma-related death occurred. No significant differences in SAEs were found between regular formoterol and regular salmeterol in adults or children with asthma. All of the participants enrolled were taking inhaled corticosteroids at baseline.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All of the studies enrolled patients who were already taking inhaled corticosteroids. Therefore it has not been possible to assess the relative safety of formoterol and salmeterol in patients who were not prescribed background inhaled corticosteroids, but this is no longer considered acceptable practice.

Quality of the evidence

No double-blind trials have been carried out comparing regular formoterol with regular salmeterol. The open studies included in this review could have been influenced by the fact that the participants and investigators were aware of the assigned treatment for each patient, especially in studies sponsored by the companies marketing one of the comparator medications.

Potential biases in the review process

Data on SAEs have been obtained for all of the included studies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our two previous reviews (Cates 2008; Cates 2008a) indicated an increase in all-cause SAEs when both regular formoterol and regular salmeterol were compared with placebo. It would require very large numbers of patients in head-to-head comparison trials to determine whether there is any difference in SAEs between regular formoterol and salmeterol, and it is perhaps not surprising that it has not been possible to draw conclusions from this review, as the number of participants in the included trials is relatively small.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Four unblinded studies have been identified comparing regular formoterol to regular salmeterol. SAEs were infrequent and consequently too few patients have been studied to allow firm conclusions to be drawn. Asthma-related SAEs were rare and there were no reported asthma-related deaths.

Implications for research

In order to compare the safety of regular formoterol and regular salmeterol, much larger surveillance studies would need to be carried out. Ideally these should be double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group studies.

A further review compares regular formoterol and salmeterol when randomised together with additional inhaled corticosteroids (Cates 2011).

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Regular treatment with formoterol versus regular treatment with salmeterol in chronic asthma: serious adverse events

Asthma is a common condition that affects the airways - the small tubes that carry air in and out of the lungs. When a person with asthma comes into contact with an irritant (an asthma trigger), the muscles around the walls of the airways tighten, the airways become narrower, and the lining of the airways becomes inflamed and starts to swell. This leads to the symptoms of asthma - wheezing, coughing and difficulty in breathing. They can lead to an asthma attack or exacerbation. People can have underlying inflammation in their lungs and sticky mucus or phlegm may build up, which can further narrow the airways. There is no cure for asthma; however there are medications that allow most people to control their asthma so they can get on with daily life.

Long-acting beta2-agonists, such as formoterol and salmeterol, work by reversing the narrowing of the airways that occurs during an asthma attack. These drugs - taken by inhaler - are known to improve lung function, symptoms, quality of life and reduce the number of asthma attacks. However, there are concerns about the safety of long-acting beta2-agonists, particularly in people who are not taking inhaled corticosteroids to control the underlying inflammation.

We did this review to take a closer look at the safety of people taking formoterol daily compared to salmeterol daily. All participants were prescribed regular background treatment with inhaled corticosteroids. We found three trials on 1116 adults and one trial on 156 children. There was not enough information to draw any conclusions on the relative safety of regular formoterol and regular salmeterol in chronic asthma, but serious asthma-related events were rare, and only one non-asthma-related death was reported.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the assistance of Susan Hansen in obtaining the papers and extracting study details, Elizabeth Stovold for assistance with the update searches and of Matthew Cates with the protocol, and for input re physiology of beta-agonist receptors. We thank Prof Haydn Walters for providing editorial review and we thank Linda Armstrong from Novartis for providing data on file for Vervloet 1998 and Gabbay 1998, and Joe Gray of AstraZeneca and Dr Everden for clarifying that there were no deaths in Everden 2004.

CRG Funding Acknowledgement: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Airways Group.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

St George’s University of London, UK.

External sources

NIHR, UK.

Programme Grant

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Study design: a randomised, open-label, multicentre, parallel-group study over 6 months from September 1998 to June 1999 at 100 centres. Run-in: 1 week, long-acting beta2-agonists appear to have been withdrawn. | |

| Participants |

Population: 528 adults (18 to 75) years with moderate to moderately severe asthma Baseline characteristics: mean age not stated. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants Inclusion criteria: Outpatients between 18 and 75 years with moderate to moderately severe asthma diagnosed at least 1 year before screening. Must have been receiving low-dose inhaled corticosteroids at 400 μg/d (except fluticasone, 200 μg/d) for at least 1 month before screening, in addition to requiring a short-acting inhaled beta2-agonist at least 4 times per week. Any long-acting beta2-agonists had to be discontinued at least 1 week before study entry. FEV1 % predicted between 40% to 80%, bronchodilator reversibility by an increase of at least 12% in FEV1 after treatment with a beta2-agonist bronchodilator at the screening visit or within 6 months before this visit Exclusion criteria: pregnant or nursing women, and women of childbearing potential who were not practising reliable contraception. Respiratory diseases unrelated to asthma or other serious medical conditions, if they required a dose increase in inhaled corticosteroids to treat an acute exacerbation of asthma within 1 month before study entry. A history of allergy to sympathomimetic amines, aerosols or inhaled lactose, Taking beta-receptor-blocking medications, drugs that prolong the cardiac QT interval, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase derivatives or non-potassium-sparing diuretics |

|

| Interventions | 1. Formoterol 12 μg BD (Foradil Aerolizer) 2. Salmeterol 50 μg BD (Serevent Diskus inhaler) Delivery was DPI |

|

| Outcomes | The primary end point was mean morning PEF measure 5 minutes after dosing. SAEs reported (all-cause and asthma-related) “No deaths were reported in either treatment arm. SAEs were reported in 7 patients receiving formoterol (1 each, bronchospasm, chest pain, cholelithiasis, colon cancer, dyspnea, fracture, syncope) and 12 patients receiving salmeterol (1 each, abdominal pain, amnesia, appendicitis, bronchitis, cranial injury, fracture, glioma, intervertebral disc disorder, metastases, myocardial infarction; 2, breast cancer). In addition, asthma was reported as a serious adverse event in 2 patients receiving formoterol and 3 patients receiving salmeterol.” |

|

| Notes | Sponsored by Novartis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details of randomisation process |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details of randomisation process |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Open study |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 85.5% on formoterol and 88.7% on salmeterol completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE results reported in the paper |

| Methods | Study design: an open randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study over 12 weeks at 58 general practice centres (UK (56), Republic of Ireland(2)). Run-in 7 to 10 days | |

| Participants |

Population: 156 children (6 to 17) years with moderate persistent asthma Baseline characteristics: mean age 12 years. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants. PEF at randomisation 317.5 ± 110.4 (eformoterol) 311.5± 109.2 (salmeterol). Inclusion criteria: outpatients aged 6 to 17 years, with a clinical diagnosis of moderate, persistent asthma. Had to have been receiving ICS for asthma at a constant dose for at least 4 weeks prior to enrolment, currently using inhaled short-acting beta2-agonists for relief of asthma symptoms, and have had asthma symptoms occurring on at least 3 days or nights out of the past 7 days prior to enrolment. For randomisation, needed to have continued to experience asthma symptoms and to have used at least 7 actuations of short-acting b2-agonists in the last 7 days or nights for relief of asthma symptoms Exclusion criteria: PEF predicted less than 50%, asthma symptoms requiring immediate treatment, significant concurrent disease or health problems, or a requirement for additional medication (e.g. ß-blocker therapy, nebulised therapy, oral steroids or oral short-acting beta2-agonists) which may have interfered with the evaluation of the study drug |

|

| Interventions | 1. Formoterol 12 μg bid (Oxis Turbohaler, delivered dose 9 μg) 2. Salmeterol 50 μg bid (Accuhaler) Delivery was DPI |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome variable was the comparison of treatments via diary card assessment of changes in daytime short-acting b2-agonist use during the 7 days prior to the final (week 12) clinic visit. SAEs reported “Two patients reported serious AEs, testicular torsion (eformoterol) and diabetes mellitus (salmeterol), but neither were considered related to test treatment.” |

|

| Notes | Sponsored by AstraZeneca | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated randomisation scheme |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Open |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 33 patients discontinued the study (formoterol 21, salmeterol 12). All patients who took at least 1 dose of medication were included in the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE data reported |

| Methods | Study design: 3-month, randomised, open, parallel-group, multicentre (55 centres) general practice-based study. 2-week run-in period. From October 1995 to December 1996 | |

| Participants |

Population: 127 participants with asthma on regular maintenance anti-inflammatory therapy, but still complained of night time symptoms Baseline characteristics: mean age not stated. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants Inclusion criteria: patients had to be at least 18 years or age with reversible obstructive airways disease, with significant nocturnal symptoms at least twice per week and PEF 50% to 80% previous best at least 3 times per week during run-in. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids: all patients were on a stable dose of at least 400 μg BDP daily (or equivalent) Exclusion criteria: no details |

|

| Interventions | 1. Formoterol 12 μg BD (Foradil Aerolizer) 2. Salmeterol 50 μg BD (Serevent Diskus inhaler) Delivery was DPI |

|

| Outcomes | Day and night symptoms, morning and evening pre-drug PEF, rescue medication use. No information on adverse events found in abstract Novartis have provided data on file indicating that there were no deaths in this study. There was only 1 patient in the salmeterol group who suffered a SAE (asthma exacerbation). This was not included in the safety analysis as there was no confirmation that the patient had taken any study medication |

|

| Notes | Sponsored by Novartis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Open |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | 106 of 127 randomised were analysed for safety |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE data provided by Novartis |

| Methods | Study design: a randomised, open, multicentre, parallel-group study over 6 months at 41 centres (France, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom). Run-in 2 weeks | |

| Participants |

Population: 482 adults (18 to 78) years with moderate to severe asthma Baseline characteristics: mean age 48 years. Morning PEF 374, evening PEF 386. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants Inclusion criteria: outpatients with a documented diagnosis of reversible obstructive airways disease for 1 year or more, using regular inhaled corticosteroids at a constant dose of at least 400 μg day (or 200 μg day fluticasone) for at least 1 month before inclusion. No attempt was made to exclude reversible COPD but the authors state that the vast majority of participants would have had asthma based on the inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria: evidence of other clinically relevant diseases, pregnant or lactating women, patients on beta-blocker therapy or with hypersensitivity to sympathomimetic amines or inhaled lactose |

|

| Interventions | 1. Formoterol 12 μg BD (Foradil Aerolizer) 2. Salmeterol 50 μg BD (Serevent Diskus inhaler) Delivery was DPI |

|

| Outcomes |

Outcome: the primary efficacy variable was the mean morning pre-dose PEF during the last 7 days of treatment No reported data on SAEs or mortality in the paper but data on file obtained from Novartis. 1 death occurred in the salmeterol group following myocardial infarction. 19 patients suffered a serious adverse event on formoterol and 22 on salmeterol (including the 1 patient who died); 4 patients on formoterol and 4 on salmeterol suffered an asthma-related serious adverse event, and 1 additional patient on formoterol developed respiratory failure |

|

| Notes | Sponsored by Novartis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated randomisation scheme was used to provide balanced blocks of patient numbers for the 2 treatment groups within each country. A one-to-one treatment allocation and a block size of 8 were used |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Open |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 428/482 (89%) completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Full SAE data obtained from Novartis |

AE: adverse event; BD: twice a day; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BDP: budesonide diphosphionate; DPI: dry powder inhaler; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; PEF: peak expiratory flow; SAE: serious adverse event

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Brambilla 2003 | 4-week study |

| Campbell 1999 | 8-week study, followed by 4-week cross-over to assess patient preference |

| Eryonucu 2005 | Single-dose study |

| Heijerman 1999 | 6-week study |

| Larsson 1990 | Review of 3 other studies |

| Lemaigre 2006 | Single-dose study |

| Novartis 2005 | Comparison between different ways of using formoterol (no salmeterol arm) |

| Pohunek 2004 | Single-dose cross-over study |

| Sill 1999 | Single-dose study |

| van der Woude 2004 | Single-dose study |

| van Veen 2003 | Cross-over study of bronchodilator tolerance |

| Verini 1998 | 5-day treatment periods |

| Von Berg 2003 | No salmeterol arm |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1.

Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All-cause mortality | 4 | 1272 | Risk Difference (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | −0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] |

| 1.1 Adults | 3 | 1116 | Risk Difference (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | −0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] |

| 1.2 Children | 1 | 156 | Risk Difference (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [−0.02, 0.02] |

| 2 All-cause SAEs | 4 | 1272 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.47, 1.28] |

| 2.1 Adults | 3 | 1116 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.46, 1.28] |

| 2.2 Children | 1 | 156 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.06, 15.33] |

| 3 Asthma-related SAEs | 4 | 1272 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.29, 2.57] |

| 3.1 Adults | 3 | 1116 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.29, 2.57] |

| 3.2 Children | 1 | 156 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 All-cause SAEs (Sensitivity analysis) | 4 | 1272 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.46, 1.24] |

| 4.1 Adults | 3 | 1116 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.45, 1.24] |

| 4.2 Children | 1 | 156 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.06, 15.33] |

| 5 Asthma-related SAEs (Sensitivity analysis) | 4 | 1272 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.26, 2.17] |

| 5.1 Adults | 3 | 1116 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.26, 2.17] |

| 5.2 Children | 1 | 156 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol, Outcome 1 All-cause mortality

Review: Regular treatment with formoterol versus regular treatment with salmeterol for chronic asthma: serious adverse events

Comparison: 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol

Outcome: 1 All-cause mortality

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol, Outcome 2 All-cause SAEs

Review: Regular treatment with formoterol versus regular treatment with salmeterol for chronic asthma: serious adverse events

Comparison: 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol

Outcome: 2 All-cause SAEs

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol, Outcome 3 Asthma-related SAEs

Review: Regular treatment with formoterol versus regular treatment with salmeterol for chronic asthma: serious adverse events

Comparison: 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol

Outcome: 3 Asthma-related SAEs

|

Analysis 1.4. Comparison 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol, Outcome 4 All-cause SAEs (Sensitivity analysis)

Review: Regular treatment with formoterol versus regular treatment with salmeterol for chronic asthma: serious adverse events

Comparison: 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol

Outcome: 4 All-cause SAEs (Sensitivity analysis)

|

Analysis 1.5. Comparison 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol, Outcome 5 Asthma-related SAEs (Sensitivity analysis)

Review: Regular treatment with formoterol versus regular treatment with salmeterol for chronic asthma: serious adverse events

Comparison: 1 Regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol

Outcome: 5 Asthma-related SAEs (Sensitivity analysis)

|

Appendix 1. Pharmacology of beta2-agonists

Beta2-agonists are thought to cause bronchodilation primarily through binding beta2-adrenoceptors on airways smooth muscle (ASM), with subsequent activation of both membrane-bound potassium channels and a signalling cascade involving enzyme activation and changes in intracellular calcium levels following a rise in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) (Barnes 1993). However, beta2-adrenoceptors are also expressed on a wide range of cell types where beta2-agonists may have a clinically significant effect including airway epithelium (Morrison 1993), mast cells, post capillary venules, sensory and cholinergic nerves and dendritic cells (Anderson 2006). Beta2-agonists will also cross-react to some extent with other beta-adrenoceptors including beta1-adrenoceptors on the heart. The in vivo effect of any beta2-agonist will depend on a number of factors relating to both the drug and the patient. The degree to which a drug binds to one receptor over another is known as selectivity, which can be defined as absolute binding ratios to different receptors in vitro, whilst functional selectivity is measured from downstream effects of drugs in different tissue types in vitro or in vivo. All of the beta2-agonists described thus far are more beta2 selective than their predecessor isoprenaline in vitro. However, because attempts to differentiate selectivity between the newer agents are confounded by so many factors, it is difficult to draw conclusions about in vitro selectivity studies and probably best to concentrate on specific adverse side effects in human subjects at doses which cause the same degree of bronchoconstriction. The potency of a drug refers to the concentration that achieves half the maximal receptor activation of which that drug is capable but it is not very important clinically as for each drug, manufacturers will alter the dose to try to achieve a therapeutic ratio of desired to undesired effects. In contrast efficacy refers to the ability of a drug to activate its receptor independent of drug concentration. Drugs that fully activate a receptor are known as full agonists and those that partially activate a receptor are known as partial agonists. Efficacy also is very much dependent on the system in which it is being tested and is affected by factors including the number of receptors available and the presence of other agonists and antagonists. Thus whilst salmeterol acts as a partial agonist in vitro it causes a similar degree of bronchodilation to the strong agonist formoterol in stable asthmatic patients (van Noord 1996), presumably because there are an abundance of well-coupled beta2-adrenoceptors available with few downstream antagonising signals. In contrast, with repetitive dosing formoterol is significantly better than salmeterol at preventing methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction (Palmqvist 1999). These differences have led to attempts to define the “intrinsic efficacy” of a drug independent of tissue conditions (Hanania 2002), as shown in Table 1. The clinical significance of intrinsic efficacy remains unclear.

Table 1. Intrinsic efficacy of beta-agonists.

| Drug | Intrinsic efficacy (%) |

|---|---|

| Isoprenaline, adrenaline | 100 |

| Fenoterol | 42 |

| Formoterol | 20 |

| Salbutamol | 4.9 |

| Salmeterol | < 2 |

Adapted from Hanania 2002. The authors acknowledge that it is difficult to determine the intrinsic efficacy of salmeterol given its high lipophilicity.

Appendix 2. Possible mechanisms of increased asthma mortality with beta-agonists

Direct toxicity

This hypothesis states that direct adverse effects of beta2-agonists are responsible for an associated increase in mortality and most research in the area has concentrated on effects detrimental to the heart. Whilst it is often assumed that cardiac side effects of beta2-agonists are due to cross-reactivity with beta1-adrenoceptors (i.e. poor selectivity), it is worth noting that human myocardium also contains an abundance of beta2-adrenoceptors capable of triggering positive chronotropic and inotropic responses (Lipworth 1992). Indeed, there is good evidence that cardiovascular side effects of isoprenaline (Arnold 1985) and other beta2-agonists including salbutamol (Hall 1989) are mediated predominantly via cardiac beta2-adrenoceptors thus making the concept of in vitro selectivity less relevant. Generalised beta2-adrenoceptor activation can also cause hypokalaemia (Brown 1983) and it has been proposed that, through these and other actions beta2-agonists may predispose to life-threatening dysrhythmias or cause other adverse cardiac effects.

During the 1960s epidemic most deaths occurred in patients with severe asthma and it was originally assumed that asthma and its sequelae, including hypoxia, were the primary cause of death. However, mucus plugging and hypoxia does not preclude a cardiac event as the final cause of death, and one might expect those with severe asthma to take more doses of a prescribed inhaler. As noted by Speizer and Doll most deaths in the 1960s were in the 10 to 19 age group and “at these ages children have begun to act independently and may be particularly prone to misuse a self-administered form of treatment” (Speizer 1968). If toxicity were related to increasing doses of beta2-agonists one might expect most deaths to occur in hospital where high doses are typically used and this was not the case. One possible explanation for this anomaly was provided by animal experiments in which large doses of isoprenaline caused little ill effect in anaesthetised dogs with normal arterial oxygenation whereas much smaller doses caused fatal cardiac depression and asystole (although no obvious dysrhythmia) when hypoxic (Collins 1969; McDevitt 1974). It has been hypothesised therefore that such events would be less likely in hospital where supplemental oxygen is routinely given. The clinical relevance of these studies remains unclear although there is some evidence of a synergistic effect between hypoxia and salbutamol use in asthmatic patients in reducing total peripheral vascular resistance (Burggraaf 2001) - another beta2 mediated effect which could be detrimental to the heart during an acute asthma attack through a reduction in diastolic blood pressure. Other potential mechanisms of isoprenaline toxicity include a potential increase in mucous plugging and worsening of ventilation perfusion mismatch despite bronchodilation (Pearce 1990).

Further concerns about a possible toxic effect of beta2-agonists were raised during the New Zealand epidemic in the 1970s. In 1981 Wilson et al, who first reported the epidemic, reviewed 22 fatal cases of asthma and noted “In 16 patients death was seen to be sudden and unexpected. Although all were experiencing respiratory distress, most were not cyanosed and the precipitate nature of their death suggested a cardiac event, such as an arrest, inappropriate to the severity of their respiratory problem” (Wilson 1981). In humans, fenoterol causes significantly greater chronotropic, inotropic and electrocardiographic side effects than salbutamol in asthmatic patients (Wong 1990). Interestingly, across the same parameters fenoterol also causes more side effects than isoprenaline (Burgess 1991).

In patients with mild asthma and without a bronchoconstrictor challenge, salmeterol and salbutamol cause a similar degree of near maximal bronchodilation at low doses (Bennett 1994). However, whilst as a one-off dose salbutamol is typically used at two to four times the concentration of salmeterol, the dose equivalences for salmeterol versus salbutamol in increasing heart rate and decreasing potassium concentration and diastolic blood pressure were 17.7, 7.8 and 7.6 respectively (i.e. salmeterol had a greater effect across all parameters). Given the lower intrinsic efficacy of salmeterol (Table 1), these results highlight the importance of in vivo factors; one possible explanation for the difference is the increased lipophilicity of salmeterol compared to salbutamol contributing to higher systemic absorption (Bennett 1994).

When comparing increasing actuations of standard doses of formoterol and salmeterol inhalers in stable asthmatic patients, relatively similar cardiovascular effects are seen at lower doses (Guhan 2000). However, at the highest doses (above those recommended by the manufacturers) there were trends towards an increase in systolic blood pressure with formoterol; in comparison there was a trend towards a decrease in diastolic blood pressure and an increase in QTc interval with salmeterol although no statistical analysis of the difference was performed. In contrast in asthmatic patients with methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction there was no significant difference between salmeterol and formoterol in causing increased heart rate and QTc interval although formoterol caused significantly greater bronchodilation and hypokalaemia (Palmqvist 1999). Whilst there is good evidence of cardiovascular and metabolic side effects with increasing doses of beta2-agonists, it is a little difficult to envisage serious adverse effects of this nature when using long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs) at manufacturer-recommended preventative doses. However, it is possible that some patients choose to use repeated doses of LABAs during exacerbations.

Tolerance

In this setting, the term tolerance refers to an impaired response to beta2-agonists in patients who have been using regular beta2-agonist treatment previously (Haney 2006). Tolerance is likely to result from a combination of reduced receptor numbers secondary to receptor internalisation and reduced production and also uncoupling of receptors to downstream signalling pathways following repeated activation (Barnes 1995). This phenomenon is likely to explain the beneficial reduction in systemic side effects seen with regular use of beta2-agonists including salbutamol after one to two weeks (Lipworth 1989). However, the same effect on beta2-adrenoceptors in the lung might be expected to produce a diminished response to the bronchodilating activity of beta2-agonists following regular use. In patients with stable asthma, whilst there is some evidence of tolerance to both salbutamol (Nelson 1977) and terbutaline (Weber 1982) other studies have been less conclusive (Harvey 1982; Lipworth 1989). However, evidence of tolerance to short and long-acting beta2-agonists in both protecting against and reducing bronchoconstriction is much stronger in the setting of an acute bronchoconstrictor challenge with chemical, allergen and ‘natural’ stimuli (Haney 2006; Lipworth 1997).

Studies comparing salmeterol and formoterol have shown that both cause tolerance compared to placebo but there was no significant difference between the drugs (van der Woude 2001). There also appears to be little difference in the tolerance induced by regular formoterol and regular salbutamol treatment (Hancox 1999; Jones 2001). To the authors’ knowledge no studies have looked specifically at the degree of tolerance caused by isoprenaline and fenoterol in the setting of acute bronchoconstriction. Tolerance to bronchodilation has been shown clearly to occur with addition of inhaled corticosteroids to salmeterol and formoterol (Lee 2003) and terbutaline (Yates 1996). There is conflicting evidence as to whether high-dose steroids can reverse tolerance in the acute setting (Jones 2001; Lipworth 2000).

At first glance the toxicity and tolerance hypotheses might appear incompatible as systemic and cardiovascular tolerance ought to protect against toxicity in the acute setting and there is good evidence that such tolerance occurs in stable asthmatic patients (Lipworth 1989). However, whilst this study showed that changes in heart rate and potassium levels were blunted by previous beta2-agonist use, they were not abolished; furthermore, at the doses studied these side effects appear to follow an exponential pattern (Lipworth 1989). In contrast, in the presence of bronchoconstrictor stimuli the bronchodilator response to beta2-agonists follows a flatter curve (Hancox 1999; Wong 1990) and as previously discussed this curve is shifted downwards by previous beta2-agonist exposure (Hancox 1999). Thus, it is theoretically possible that in the setting of an acute asthmatic attack and strong bronchoconstricting stimuli, bronchodilator tolerance could lead to repetitive beta2-agonist use and ultimately more systemic side effects than would otherwise have occurred. Of course, other sequelae of inadequate bronchodilation including airway obstruction will be detrimental in this setting.

Whilst the tolerance hypothesis is often cited as contributing towards the asthma mortality epidemics it is difficult to argue that reduced efficacy of a drug can cause increased mortality relative to a time when that drug was not used at all. However, tolerance to the bronchodilating effect of endogenous circulating adrenaline is theoretically possible and there is also evidence of rebound bronchoconstriction when stopping fenoterol (Sears 1990), which may be detrimental. Furthermore, it appears that regular salbutamol treatment can actually increase airway responsiveness to allergen (Cockcroft 1993) a potentially important effect that could form a variant of the toxicity hypothesis. Differences between beta2-agonists in this regard are unclear, but the combination of rebound hyper responsiveness and tolerance of the bronchodilator effect with regular beta2-agonist exposure has been recently advocated as a possible mechanism to explain the association between beta2-agonists and asthma mortality (Hancox 2006a).

Other explanations

Confounding by severity

Historically, this hypothesis has been used extensively to try to explain the association between mortality and the use of fenoterol during the 1970s New Zealand epidemic (see Pearce 2007) and is still quoted today. The hypothesis essentially relies on the supposition that patients with more severe asthma are more likely to take either higher doses of beta2-agonists or a particular beta2-agonist (such as fenoterol) thereby explaining the association. This hypothesis was carefully ruled out in the three case-control studies by comparing the association between fenoterol and mortality in patients with varying severity of disease (Crane 1989; Grainger 1991; Pearce 1990). Furthermore, the hypothesis cannot explain the overall increase in mortality in the 1960s and 1970s nor can it explain any significant increase in mortality (whether taking inhaled steroids or not) from randomised controlled trial data.

The delay hypothesis

This hypothesis accepts that beta2-agonists or a particular beta2-agonist cause an increased risk of mortality but indirectly by causing patients to delay before getting medical help and further treatments including high-dose steroids and oxygen. There is evidence that both salmeterol and formoterol can reduce awareness of worsening underlying inflammation (Bijl-Hofland 2001; McIvor 1998). It is difficult to rule out the delay hypothesis in either explaining or contributing towards both the asthma mortality epidemics and an association with regular use of LABAs. There is evidence that beta2-agonists with higher intrinsic efficacy are more effective at relieving bronchoconstriction in the acute setting (Hanania 2007) and could paradoxically cause patients to delay seeking medical help for longer. For the delay hypothesis to explain the increase in mortality during the 1960s and 1970s one has to imply that hospital treatment of asthma when mortality rates were low during the earlier years of the 20th century was effective. It is difficult to say exactly how effective such treatment is likely to have been.

Reduced corticosteroid treatment

A slight but significant variation of the delay hypothesis suggests that patients who have separate beta2-agonists and corticosteroid inhalers may choose to take less corticosteroid because of better symptom control from the inhaled beta2-agonists and it is reduced corticosteroid treatment that contributes to a rise in mortality. It is rather difficult to see how this hypothesis explains the epidemics of asthma deaths in the 1960s and 1970s relative to the 1920s and 30s (Figure 6), given that corticosteroids were not used for the treatment of asthma in the earlier decades. If this hypothesis were to explain increased mortality from more recent randomised controlled trial data one would not expect to see an increase in mortality in those taking LABAs alone.

Figure 6. Changes in asthma mortality (5 to 34 age group) in three countries in relation to the introduction of isoprenaline forte in the UK and New Zealand and of fenoterol in New Zealand. (From Blauw 1995. With permission from the Lancet).

Appendix 3. Definition of serious adverse event (SAE)

A SAE is any adverse event occurring at any dose that results in any of the following outcomes:

Death

A life-threatening adverse event

Inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

A disability/incapacity

A congenital anomaly in the offspring of a subject who received medication

Important medical events that may not result in death, be life-threatening or require hospitalisation may be considered a serious adverse event when, based upon appropriate medical judgement, they may jeopardise the patient or subject and may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed in this definition. Examples of such medical events include allergic bronchospasm requiring intensive treatment in an emergency room or at home, blood dyscrasias or convulsions that do not result in inpatient hospitalisation, or the development of medication dependency or medication abuse.

Clarifications

“Occurring at any dose” does not imply that the subject is receiving study medication.

Life-threatening means that the subject was, in the view of the investigator, at immediate risk of death from the event as it occurred. This definition does not include an event that, had it occurred in a more severe form, might have caused death.

Hospitalisation for elective treatment of a pre-existing condition that did not worsen during the study is not considered an AE.

Complications that occur during hospitalisation are AEs. If a complication prolongs hospitalisation, the event is a SAE.

“Inpatient” hospitalisation means the subject has been formally admitted to a hospital for medical reasons. This may or may not be overnight. It does not include presentation at a casualty or emergency room.

With regard to criterion number 6 above, medical and scientific judgement should be used in deciding whether prompt reporting is appropriate in this situation.

Events or outcomes not qualifying as SAEs

The events or outcomes identified as asthma exacerbations will be recorded in the asthma exacerbations page of the case report form (CRF) page if they occur. However, these individual events or outcomes, as well as any sign, symptom, diagnosis, illness and/or clinical laboratory abnormality that can be linked to any of these events or outcomes, are not reported to GW as SAEs even though such event or outcome may meet the definition of SAE, unless the following conditions apply:

the investigator determines that the event or outcome qualifies as a SAE under criterion number 6 of the SAE definition (see Section 7.2., Definition of a SAE), or the event or outcome is in the investigator’s opinion of greater intensity, frequency or duration than expected for the individual subject, or death occurring for any reason during a study, including death due to a disease-related event.

Appendix 4. Sources and search methods for the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (CAGR)

Electronic searches: core databases

| Database | Frequency of search |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | Weekly |

| EMBASE (Ovid) | Weekly |

| CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library) | Quarterly |

| PSYCINFO (Ovid) | Monthly |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) | Monthly |

| AMED (EBSCO) | Monthly |

Handsearches: core respiratory conference abstracts

| Conference | Years searched |

|---|---|

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) | 2001 onwards |

| American Thoracic Society (ATS) | 2001 onwards |

| Asia Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR) | 2004 onwards |

| British Thoracic Society Winter Meeting (BTS) | 2000 onwards |

| Chest Meeting | 2003 onwards |

| European Respiratory Society (ERS) | 1992, 1994, 2000 onwards |

| International Primary Care Respiratory Group Congress (IPCRG) | 2002 onwards |

| Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) | 1999 onwards |

MEDLINE search strategy used to identify trials for the CAGR

Asthma search

exp Asthma/

asthma$.mp.

(antiasthma$ or anti-asthma$).mp.

Respiratory Sounds/

wheez$.mp.

Bronchial Spasm/

bronchospas$.mp.

(bronch$ adj3 spasm$).mp.

bronchoconstrict$.mp.

exp Bronchoconstriction/

(bronch$ adj3 constrict$).mp.

Bronchial Hyperreactivity/

Respiratory Hypersensitivity/

((bronchial$ or respiratory or airway$ or lung$) adj3 (hypersensitiv$ or hyperreactiv$ or allerg$ or insufficiency)).mp.

((dust or mite$) adj3 (allerg$ or hypersensitiv$)).mp.

or/1-15

Filter to identify RCTs

exp “clinical trial [publication type]”/

(randomised or randomised).ab,ti.

placebo.ab,ti.

dt.fs.

randomly.ab,ti.

trial.ab,ti.

groups.ab,ti.

or/1-7

Animals/

Humans/

9 not (9 and 10)

8 not 11

The MEDLINE strategy and RCT filter are adapted to identify trials in other electronic databases.

WHAT’S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 5 January 2012.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 April 2013 | Amended | Funder acknowledgement and PRISMA added |

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2009

Review first published: Issue 4, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 January 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No new studies found. |

| 5 January 2012 | New search has been performed | New search in January 2012 but no new studies included. Minor edits made and plain language summary revised |

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON

Regular formoterol compared to regular salmeterol for chronic asthma: SAEs.

Patient or population: patients with asthma

Settings: community

Intervention: regular formoterol

Comparison: regular salmeterol

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Regular salmeterol | Regular formoterol | |||||

|

All-cause mortality in adults Follow-up: mean 6 months |

2 per 10001 | 0 per 1000 (−9 to 13) | See comment | 1116 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕○○ low2,3 | No deaths were related to asthma. Risks were calculated from pooled risk differences |

|

All-cause mortality in children Follow-up: 3 months |

See comment | See comment | See comment | 156 (1 study) | ⊕○○○ very low2,3,4 | No deaths occurred in the single small study on children |

|

All-cause SAEs in adults Follow-up: mean 6 months |

64 per 10001 | 50 per 1000 (30 to 80) | OR 0.77 (0.46 to 1.28) | 1116 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕○○ low2,3 | |

|

All-cause SAEs in children Follow-up: 3 months |

13 per 10001 | 12 per 1000 (1 to 168) | OR 0.95 (0.06 to 15.33) | 156 (1 study) | ⊕○○○ very low2,3,4 | There was only one child in each group with a serious adverse event |

|

Asthma-related SAEs in adults Follow-up: mean 6 months |

12 per 10001 | 10 per 1000 (4 to 30) | OR 0.86 (0.29 to 2.57) | 1116 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕○○ low2,3 | |

|

Asthma-related SAEs in children Follow-up: 3 months |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 156 (1 study) | ⊕○○○ very low2,3,4 | No asthma-related SAEs in the single small study on children |

The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; SAE: serious adverse event

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate.

Mean event rate in salmeterol arm of the included studies.

Unblinded studies.

Confidence intervals too wide to reach firm conclusions.

Only one small study found in children.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST None known.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PROTOCOL AND REVIEW The ‘Summary of findings’ table was not mentioned in the protocol and has been constructed on the basis of the primary outcomes and asthma-related SAEs. Adults and children have been described separately in the ‘Summary of findings’ table.

INDEX TERMS

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Adrenal Cortex Hormones [therapeutic use]; Adrenergic beta-2 Receptor Agonists [*adverse effects]; Albuterol [adverse effects; *analogs & derivatives]; Anti-Asthmatic Agents [*adverse effects]; Asthma [*drug therapy; mortality]; Chronic Disease; Ethanolamines [*adverse effects]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words

Adult; Child; Humans

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

REFERENCES

* Indicates the major publication for the study

References to studies included in this review

- Condemi 2001 {published data only}.Condemi JJ. Comparison of the efficacy of formoterol and salmeterol in patients with reversible obstructive airway disease: a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial. Clinical Therapeutics. 2001;Vol. 23(issue 9):1529–41. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everden 2004 {published data only}.Everden P, Campbell M, Harnden C, McGoldrick H, Bodalia B, Manion V, et al. Eformoterol Turbohaler compared with salmeterol by dry powder inhaler in asthmatic children not controlled on inhaled corticosteroids. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2004;Vol. 15(issue 1):40–7. doi: 10.1046/j.0905-6157.2003.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Everden P, Lloyd A, Hutchinson J, Plumb J. Cost-effectiveness of eformoterol Turbohaler versus salmeterol Accuhaler in children with symptomatic asthma. Respiratory Medicine. 2002;Vol. 96(issue 4):250–8. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Everden P, Reynia S, Lloyd AC, Hutchinson JL, Plumb JM. Economic evaluation of eformoterol compared with salmeterol in children aged 6-17 with symptomatic asthma in the UK: cost-effectiveness results of the FACT study. European Respiratory Journal. 2001;Vol. 18(issue Suppl 33):122s. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay 1998 {published data only}.Gabbay MB, Kane H, di Benedetto G. A comparison of formoterol and salmeterol dry powders in the treatment of nocturnal asthma [abstract] European Respiratory Journal. Supplement. 1998;Vol. 12(issue Suppl 28):325S. [Google Scholar]

- Vervloet 1998 {published data only}.Rutten van Molken MP, van Doorslaer EK, Till MD. Cost-effectiveness analysis of formoterol versus salmeterol in patients with asthma. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;Vol. 14(issue 6):671–84. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199814060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sanguinetti CM, Duce F, Quebe Fehling E, Della Cioppa G, Di Benedetto G. A 6-month open comparison between formoterol and salmeterol dry powders in patients with reversible obstructive airway disease. European Respiratory Journal. 1997;Vol. 10(issue Suppl 25):241S. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Vervloet D, Ekstrom T, Pela R, Duce Gracia F, Kopp C, Silvert BD, et al. A 6-month comparison between formoterol and salmeterol in patients with reversible obstructive airways disease. Respiratory Medicine. 1998;Vol. 92(issue 6):836–42. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Brambilla 2003 {published data only}.Brambilla C, Le Gros V, Bourdeix I. Formoterol 12 mug BID administered via single-dose dry powder inhaler in adults with asthma suboptimally controlled with salmeterol or on-demand salbutamol: a multicenter, randomized, open-label, parallel-group study. Clinical Therapeutics. 2003;Vol. 25(issue 7):2022–36. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell 1999 {published data only}.Campbell LM, Anderson TJ, Parashchak MR, Burke CM, Watson SA, Turbitt ML. A comparison of the efficacy of long-acting beta 2-agonists: eformoterol via Turbohaler and salmeterol via pressurized metered dose inhaler or Accuhaler, in mild to moderate asthmatics. [Force Research Group corrected and republished with original paging, article originally printed in Respiratory Medicine 1999 Apr; 934:236-44] Respiratory Medicine. 1999;Vol. 93(issue 7):236–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eryonucu 2005 {published data only}.Eryonucu B, Uzun K, Guler N, Tuncer M, Sezgi C. Comparison of the short-term effects of salmeterol and formoterol on heart rate variability in adult asthmatic patients. Chest. 2005;Vol. 128(issue 3):1136–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijerman 1999 {published data only}.Heijerman HG, Dekker FW, Rammeloo RH, Roldaan AC, Sinninghe HE. European Respiratory Society. Madrid, Spain: Oct 9-13, 1999. Similar efficacy of formoterol via turbuhaler and salmeterol via diskhaler in the treatment of asthma. 1999:[P2209] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson 1990 {published data only}.Larsson S. Long-term studies on long-acting sympathomimetics. Lung. 1990;Vol. 168(issue Suppl):22–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02718109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaigre 2006 {published data only}.Lemaigre V, Van den Bergh O, Smets A, De Peuter S, Verleden GM. Effects of long-acting bronchodilators and placebo on histamine-induced asthma symptoms and mild bronchus obstruction. Respiratory Medicine. 2006;Vol. 100(issue 2):348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novartis 2005 {published data only}.Novartis A 12-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial to examine the long-term tolerability of formoterol 10μg via the multiple dose dry powder inhaler (MDDPI), both as twice daily maintenance therapy and as on-demand use in addition to maintenance in patients with persistent asthma. 2005 http://pharma.us.novartis.com/

- Pohunek 2004 {published data only}.Pohunek P, Matulka M, Rybnicek O, Kopriva F, Honomichlova H, Svobodova T. Dose-related efficacy and safety of formoterol (Oxis) Turbuhaler compared with salmeterol Diskhaler in children with asthma. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2004;Vol. 15:32–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0905-6157.2003.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sill 1999 {published data only}.Sill V, Bartuschka B, Villiger B, Ortland C, Domej W. Changes in specific airway resistance after powder inhalation of formoterol or salmeterol in moderate bronchial asthma. Pneumologie. 1999;Vol. 53(issue 1):4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Woude 2004 {published data only}.van der Woude HJ, Postma DS, Politiek MJ, Winter TH, Aalbers R. Relief of dyspnoea by beta2-agonists after methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction. Respiratory Medicine. 2004;Vol. 98(issue 9):816–20. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veen 2003 {published data only}.van Veen A, Weller FR, Wierenga EA, Jansen HM, Jonkers RE. A comparison of salmeterol and formoterol in attenuating airway responses to short-acting beta2-agonists. Pulmonary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2003;Vol. 16(issue 3):153–61. doi: 10.1016/S1094-5539(03)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verini 1998 {published data only}.Verini M, Verrotti A, Greco R, Chiarelli F. Comparison of the bronchodilator effect of inhaled short- and long-acting beta2-agonists in children with bronchial asthma. A randomised trial. Clinical Drug Investigation. 1998;Vol. 16(issue 1):19–24. doi: 10.2165/00044011-199816010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Berg 2003 {published data only}.Von Berg A, Papageorgiou Saxoni F, Wille S, Carrillo T, Kattamis C, Helms PJ. Efficacy and tolerability of formoterol Turbuhaler in children. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2003;Vol. 57:852–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Altman 2003.Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics notes: interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson 2006.Anderson GP. Current issues with beta(2)-adrenoceptor agonists - pharmacology and molecular and cellular mechanisms. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2006;Vol. 31(issue 2–3):119–30. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:31:2:119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold 1985.Arnold JMO, O’Connor PC, Riddell JG, Harron DWG, Shanks RG, McDevitt DG. Effects of the beta-2-adrenoceptor antagonist ici-118,551 on exercise tachycardia and isoprenaline-induced beta-adrenoceptor responses in man. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1985;Vol. 19(issue 5):619–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1985.tb02689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes 1993.Barnes PJ. Beta-adrenoceptors on smooth-muscle, nerves and inflammatory cells. Life Sciences. 1993;Vol. 52(issue 26):2101–9. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90725-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes 1995.Barnes PJ. Beta-adrenergic receptors and their regulation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995;Vol. 152(issue 3):838–60. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett 1994.Bennett JA, Smyth ET, Pavord ID, Wilding PJ, Tattersfield AE. Systemic effects of salbutamol and salmeterol in patients with asthma. Thorax. 1994;Vol. 49(issue 8):771–4. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.8.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijl-Hofland 2001.Bijl-Hofland ID, Cloosterman SG, Folgering HT, van den Elshout FJ, van Weel C, van Schayck CP. Inhaled corticosteroids, combined with long-acting beta(2)-agonists, improve the perception of bronchoconstriction in asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001;Vol. 164(issue 5):764–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.9910103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauw 1995.Blauw GJ, Westendorp RGJ. Asthma deaths in New Zealand - whodunnit. The Lancet. 1995;345:2–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown 1983.Brown MJ, Brown DC, Murphy MB. Hypokalemia from beta-2-receptor stimulation by circulating epinephrine. New England Journal of Medicine. 1983;Vol. 309(issue 23):1414–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312083092303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess 1991.Burgess CD, Windom HH, Pearce N, Marshall S, Beasley R, Siebers RWL, et al. Lack of evidence for beta-2 receptor selectivity - a study of metaproterenol, fenoterol, isoproterenol, and epinephrine in patients with asthma. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1991;Vol. 143(issue 2):444–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.2.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burggraaf 2001.Burggraaf J, Westendorp RGJ, in’t Veen J, Schoemaker RC, Sterk PJ, Cohen AF, et al. Cardiovascular side effects of inhaled salbutamol in hypoxic asthmatic patients. Thorax. 2001;Vol. 56(issue 7):567–9. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.7.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates 2008.Cates CJ, Cates MJ. Regular treatment with salmeterol for chronic asthma: serious adverse events. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(Issue 3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006363.pub2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006363.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates 2008a.Cates CJ, Cates MJ, Lasserson TJ. Regular treatment with formoterol for chronic asthma: serious adverse events. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(Issue 4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006923.pub2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006923.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates 2009.Cates CJ, Lasserson TJ, Jaeschke R. Regular treatment with formoterol and inhaled steroids for chronic asthma: serious adverse events. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(Issue 2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006924.pub2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006924.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]