Abstract

Background

An increase in serious adverse events with the use of both regular formoterol and regular salmeterol (long-acting beta2-agonists) in chronic asthma has been demonstrated in comparison with placebo in previous Cochrane reviews. This increase was significant in trials that did not randomise participants to an inhaled corticosteroid. However, systematic reviews of trials in which each drug was randomised with an inhaled corticosteroid did not demonstrate significant increases in serious adverse events. The confidence intervals were found to be too wide to be sure that the addition of an inhaled corticosteroid renders regular long-acting beta2-agonists completely safe; there were fewer participants and insufficient serious adverse events in these trials to come to a definitive decision about the safety of combination treatments.

Objectives

We set out to compare the risks of mortality and non-fatal serious adverse events in trials which have randomised patients with chronic asthma to regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol, when each are used with an inhaled corticosteroid as part of the randomised treatment.

Search methods

We identified trials using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials. We checked manufacturers’ websites of clinical trial registers for unpublished trial data and also checked Food and Drug Administration (FDA) submissions in relation to formoterol and salmeterol. The date of the most recent search was August 2011.

Selection criteria

We included controlled clinical trials with a parallel design, recruiting patients of any age and severity of asthma, if they randomised patients to treatment with regular formoterol versus regular salmeterol (each with a randomised inhaled corticosteroid) and were of at least 12 weeks duration.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion in the review and extracted outcome data. We sought unpublished data on mortality and serious adverse events from the sponsors and authors.

Main results

Ten studies on 6769 adults and adolescents met the eligibility criteria of the review. Seven studies (involving 5935 adults and adolescents) compared formoterol and budesonide to salmeterol and fluticasone. All but one study administered the products as a combined inhaler, and most used formoterol 12 μg and budesonide 400 μg twice daily versus salmeterol 50 μg and fluticasone 250 μg twice daily. There were two deaths overall (one on each combination) and neither were thought to be related to asthma.

There was no significant difference between treatment groups (formoterol/budesonide versus salmeterol/fluticasone) for non-fatal serious adverse events, either all-cause (Peto odds ratio (OR) 1.14; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.82 to 1.59, I2 = 26%) or asthma-related (Peto OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.37 to 1.26, I2 = 33%). Over 23 weeks the rates for all-cause serious adverse events were 2.6% on formoterol and budesonide and 2.3% on salmeterol and fluticasone, and for asthma-related serious adverse events, 0.6% and 0.8% respectively.

There was one study (228 adults) comparing formoterol and beclomethasone to salmeterol and fluticasone, but there were no deaths or hospital admissions. One study (404 adults) compared formoterol and mometasone to salmeterol and fluticasone for 52 weeks, but the small number of events leaves considerable uncertainty about the comparative safety of the two products. Similarly one study (202 adults) compared formoterol and fluticasone with salmeterol and fluticasone, but there was only one serious adverse event in each group.

No studies were found in children.

Authors’ conclusions

The seven identified studies in adults did not show any significant difference in safety between formoterol and budesonide in comparison with salmeterol and fluticasone. Asthma-related serious adverse events were rare, and there were no reported asthma-related deaths. There was a single, small study comparing formoterol and beclomethasone to salmeterol and fluticasone in adults, a single study comparing formoterol and mometasone with salmeterol and fluticasone in adults, and a single study comparing formoterol and fluticasone with salmeterol and fluticasone in adults.

No studies were found in children, so no conclusion can be drawn for this age group.

Overall there is insufficient evidence to decide whether regular formoterol in combination with budesonide, beclometasone, fluticasone or mometasone have equivalent or different safety profiles from salmeterol in combination with fluticasone.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Administration, Inhalation; Albuterol [administration & dosage; adverse effects; *analogs & derivatives]; Androstadienes [administration & dosage; adverse effects]; Anti-Asthmatic Agents [administration & dosage; *adverse effects]; Asthma [*drug therapy; mortality]; Budesonide [administration & dosage; adverse effects]; Drug Therapy, Combination [adverse effects]; Ethanolamines [administration & dosage; *adverse effects]; Glucocorticoids [administration & dosage; *adverse effects]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Adolescent, Adult, Humans

BACKGROUND

When patients with asthma are not controlled by low-dose inhaled corticosteroids alone, many asthma guidelines recommend additional long-acting beta2-agonists. Several Cochrane reviews have addressed the efficacy of long-acting beta2-agonists given with inhaled corticosteroids (Ni Chroinin 2009; Ni Chroinin 2010), in comparison with placebo (Walters 2007), short-acting beta2-agonists (Walters 2002), leukotriene-receptor antagonists (Ducharme 2011) and increased doses of inhaled corticosteroids (Ducharme 2010). The beneficial effects of long-acting beta2-agonists on lung function, symptoms, quality of life and exacerbations requiring oral steroids have been demonstrated, and a rationale has been put forward for their use in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid (Barnes 2002).

Concern remains that regular treatment with long-acting beta2-agonists might lead to an increase in asthma-related deaths (as seen in SMART 2006). Regular treatment with beta2-agonists can lead to tolerance to their bronchodilator effects with both long-acting and short-acting compounds (Lipworth 1997). A number of molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain the possible detrimental effect of long-term beta2-agonist use in asthma, including receptor down-regulation and desensitisation (Giembycz 2006).

A recent meta-analysis of the effect of long-acting beta2-agonists on severe asthma exacerbations and asthma-related deaths (Salpeter 2006) concluded that “long-acting beta-agonists have been shown to increase severe and life-threatening asthma exacerbations, as well as asthma-related deaths”. Salpeter 2006 considered trials that compared any long-acting beta2-agonists with placebo, and the review was not able to include 28 trials in the primary analysis (including nearly 6000 patients) because information was not provided for asthma-related deaths.

Currently there are two long-acting beta2-agonists available, salmeterol and formoterol (also known as eformoterol). These two drugs are known to have differences in speed of onset and receptor activity, and are used in different ways (for example, salmeterol has a slower onset of action than salbutamol, Beach 1992). For this reason we have considered salmeterol and formoterol separately in our previous work.

Two of our published reviews have assessed the risk of fatal and non-fatal serious adverse events with regular salmeterol (Cates 2008) and formoterol (Cates 2008a) in comparison to placebo or short-acting beta2-agonists. In comparison to placebo, adults on regular salmeterol and children on regular formoterol demonstrated a significant increase in all-cause non-fatal serious adverse events. Two further reviews, in which each drug was randomised with an inhaled corticosteroid in comparison to the same dose of the inhaled corticosteroid have also been completed (Cates 2009;Cates 2009a). These did not demonstrate significant increases in serious adverse events, but the confidence intervals are too wide to be sure that the addition of an inhaled corticosteroid renders regular long-acting beta2-agonists completely safe. Moreover, indirect comparisons on the relative safety of formoterol and salmeterol from the results of these existing reviews are subject to confounding due to differences in the participants, interventions, comparisons and outcomes in the trials of each review.

A review comparing the safety of regular formoterol and salmeterol without a randomised inhaled corticosteroid has also been carried out from trials that have made head-to-head comparisons of the two products (Cates 2009b). The trials that were included in Cates 2009b turned out to have used background inhaled corticosteroids in all participants. However, no previous review has compared regular formoterol to regular salmeterol from trials in which an inhaled corticosteroid was a mandatory part of the randomised treatment. We have considered this to be a separate question, as adherence with an inhaled corticosteroid may be better when it is part of the randomised treatment schedule (particularly if a combined inhaler is used).

This review, therefore, sets out to compare the safety of regular formoterol and regular salmeterol when each is used in combination with a randomised inhaled corticosteroid.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the risk of mortality and non-fatal serious adverse events in trials which have randomised patients with chronic asthma to regular formoterol and an inhaled corticosteroid versus regular salmeterol and an inhaled corticosteroid.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included controlled, parallel-design clinical trials, with or without blinding, in which patients with chronic asthma were randomly assigned to regular treatment with formoterol and an inhaled corticosteroid versus salmeterol and an inhaled corticosteroid. We excluded studies on acute asthma and exercise-induced bronchospasm.

Types of participants

We included patients with a clinical diagnosis of asthma of any age group, unrestricted by disease severity, previous or current treatment.

Types of interventions

We included trials randomising patients to formoterol versus salmeterol given regularly in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid at any dose and delivered at fixed dose by any single or separate devices (chlorofluorocarbon metered dose inhaler (CFCMDI); hydrofluoroalkane metered dose inhaler (HFA-MDI); dry powder inhaler (DPI)) for a period of at least 12 weeks. We excluded studies that used adjustable maintenance dosing and single inhaler therapy (for maintenance and relief of symptoms).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All-cause mortality

All-cause non-fatal serious adverse events (see definition below)

Secondary outcomes

Asthma-related mortality

Asthma-related non-fatal serious adverse events

Cardiovascular-related mortality

We did not subdivide outcomes according to whether the trial investigators considered them to be related to trial medication. We accepted trial investigators’ judgement of whether serious adverse events were asthma-related or not.

An assessment of efficacy outcomes (such as exacerbations, symptoms and lung function) of these drug combinations when co-delivered via the same inhaler has been undertaken and published elsewhere (Lasserson 2008).

Definition of serious adverse events

The Expert Working Group (Efficacy) of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) define serious adverse events as follows (ICHE2a 1995):

“A serious adverse event (experience) or reaction is any untoward medical occurrence that at any dose:

results in death,

is life-threatening,

requires inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization,

results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, or

is a congenital anomaly/birth defect.

NOTE: The term “life-threatening” in the definition of “serious” refers to an event in which the patient was at risk of death at the time of the event; it does not refer to an event which hypothetically might have caused death if it were more severe.”

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (please see Appendix 1). We searched all records in the Specialised Register coded as ‘asthma’ using the following terms: (((salmeterol or serevent) AND (formoterol or eformoterol or oxis or foradil) AND (steroid* or corticosteroid* or ICS or fluticasone or FP or Flixotide or budesonide or BUD or Pulmicort or beclomethasone or becotide or becloforte or becodisk or QVAR or ciclesonide or triamcinolone or flunisolide or mometasone)) OR (Symbicort or Viani or Seretide or Advair or Inuvair)) AND (serious or safety or surveillance or mortality or death or intubat* or adverse or toxicity or complications or tolerability)

In addition we carried out a second search just using the terms: (salmeterol or serevent) AND (formoterol or eformoterol or oxis or foradil).

The date of the most recent search was August 2011.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We checked websites of clinical trial registers for unpublished trial data and we also checked FDA submissions in relation to salmeterol and formoterol.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (CJC) independently assessed studies identified in the literature searches by examining titles, abstracts and keyword fields. We obtained studies that potentially fulfilled the inclusion criteria in full text. Two review authors (CJC and TL) independently assessed full-text articles for inclusion. No disagreements occurred.

Data extraction and management

One review author (CJC) extracted data using a prepared checklist and entered data into RevMan 5. The second review author (TL) independently checked the data extraction and entry. We extracted data on characteristics of included studies (methods, participants, interventions, outcomes) and results of the included studies. We contacted authors and sponsors of included studies for unpublished adverse event data and searched manufacturers’ websites for further details of adverse events. We also searched FDA submissions. We recorded all-cause serious adverse events (fatal and non-fatal) and in view of the difficulty in deciding whether events are asthma-related, noted details of the cause of death and serious adverse events. We requested further information when causation was not clear (particularly in relation to hospital admissions and serious adverse events).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

One review author (CJC) assessed the included studies for bias protection (including sequence generation for randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and assessors, loss to follow-up, completeness of outcome assessment and other possible bias prevention). We judged risk of bias as either high, low or unclear according to recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008).

Unit of analysis issues

We confined our analysis to patients with one or more serious adverse events, rather than the number of events that occurred (as the latter are not independent when one patient suffers multiple events).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic to indicate how much of the total heterogeneity found was between, rather than within studies.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to inspect funnel plots to assess publication bias.

Data synthesis

The outcomes of this review were dichotomous and we recorded the number of participants with one or more of each outcome event, by allocated treated group. We calculated pooled odds ratios (OR) and risk differences (RD). The Peto odds ratio has advantages when events are rare, as no adjustment for zero cells is required. This property was found in previous reviews to be more important than potential problems with unbalanced treatment arms, and we therefore calculated the results for serious adverse events in RevMan 5 using the Peto method with Mantel-Haenszel methods for sensitivity analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analyses on the basis of age (adults versus children) and dose of inhaled corticosteroids (equivalence between arms or not). We planned to compare subgroups using tests for interaction (Altman 2003).

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of the method used to combine the study events (risk difference, Peto odds ratio and Mantel-Haenszel odds ratio). We conducted a sensitivity analysis on the degree of bias protection in the study designs.

RESULTS

Description of studies

Results of the search

We carried out the original search for relevant studies in January 2009 and identified 106 potentially relevant abstracts. We obtained 12 abstracts as full articles and included seven abstracts relating to six studies (Aalbers 2004; Busse 2008; Dahl 2006; Kuna 2007; Papi 2007; Ringdal 2002). We excluded three review articles (Bleecker 2008; Dhillon 2006; Lyseng-Williamson 2003) with reasons provided in Characteristics of excluded studies. We also carried out an extended search in which the adverse event terms were excluded, and this identified a further 184 abstracts; from these we obtained 17 further full-text articles. We included two further studies from the GSK trials register (SAM 40010; SAM 40048); excluded one study (Lee 2003) and the other articles were all additional references to studies that had already been included. A total of eight studies reported in 35 separate references met the eligibility criteria of the review.

A subsequent search in July 2009 did not identify any further studies for inclusion, but there were two further potentially relevant studies that we subsequently excluded (Hampel 2008; Jung 2008), see Characteristics of excluded studies for further details. In August 2011 a further search identified three new citations for studies already included (Aalbers 2004; Busse 2008; Kuna 2007), three citations for a new study comparing formoterol and fluticasone with salmeterol and fluticasone (Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011) and six citations for a new study on 404 adults comparing formoterol and mometasone with salmeterol and fluticasone (Maspero 2010).

Included studies

Dose and delivery of medication

Overall in seven studies 5935 adults were randomised to formoterol and budesonide versus salmeterol and fluticasone; 228 adults were randomised to formoterol and extra-fine beclomethasone versus salmeterol and fluticasone in Papi 2007, 202 adults were randomised to formoterol and fluticasone or salmeterol and fluticasone in Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011 and 404 adults were randomised to formoterol and mometasone or salmeterol and fluticasone in Maspero 2010.

Details of the delivery devices and doses of the medication in each trial are given in Table 1. All the studies used combination inhalers except for Ringdal 2002, in which formoterol and budesonide were administered in separate inhalers. We judged the dose of inhaled corticosteroid in each arm to be equivalent except in Ringdal 2002 (higher-dose budesonide) and SAM 40048 (higher-dose fluticasone), see Table 1. Whilst most studies compared 12 μg formoterol twice daily with 50 μg salmeterol twice daily, SAM 40010 and SAM 40048 compared 6 μg formoterol with 50 μg salmeterol twice daily.

Table 1. Details of the dose and type of medication used.

| Study ID | Formoterol device | Formoterol dose | ICS type and dose | Salmeterol device | Salmeterol dose | ICS type and dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aalbers 2004 | DPI | 12 μg bd | Budesonide 400 μg bd | DPI | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 250 μg bd |

| Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011 | HFA pMDI with AeroChamber | 10 μg bd | Fluticasone 100 μg or 250 μg bd | HFA pMDI with AeroChamber | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 100 μg or 250 μg bd |

| Busse 2008 | pMDI | 12 μg bd | Budesonide 400 μg bd | DPI | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 250 μg bd |

| Dahl 2006 | DPI | 12 μg bd | Budesonide 400 μg bd | DPI | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 250 μg bd |

| Kuna 2007 | DPI | 12 μg bd | Budesonide 400 μg bd | pMDI | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 250 μg bd |

| Maspero 2010 | pMDI | 10 μg bd | Mometasone 200 μg or 400 μg bd | pMDI | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 250 μg or 500 μg bd |

| Papi 2007 | pMDI | 12 μg bd | Beclomethasone extra fine 200 μg bd | pMDI | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 250 μg bd |

| Ringdal 2002 | DPI two separate inhalers | 12 μg bd | Budesonide 800 μg bd | DPI | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 250 μg bd |

| SAM 40010 | DPI | 6 μg bd | Budesonide 200 μg bd | DPI | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 100 μg bd |

| SAM 40048 | DPI | 6 μg bd | Budesonide 200 μg bd | DPI | 50 μg bd | Fluticasone 250 μg bd |

Doses shown are ex-actuator rather than delivered doses.

bd: twice a day

DPI: dry powder inhaler

ICS: inhaled corticosteroid

HFA: hydrofluoroalkane

pMDI: pressurised metered dose inhaler

Run-in period

In all studies except Busse 2008 and Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011, the participants continued their previous treatment with inhaled corticosteroids alone during the run-in period (those previously on long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) were either excluded or discontinued LABA treatment), and were enrolled in the study if they were symptomatic at the end of run-in. Busse 2008 allowed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and LABA/ICS to be continued during run-in, but participants still had to be symptomatic to be enrolled into the study. Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011 did not specify treatment details for the screening phase of 4 to 10 days to evaluate eligibility, and Maspero 2010 kept participants on their previous medication during screening.

Age of participants

No studies were found in children. The lower age limit in the studies varied from 12 years old (Aalbers 2004; Busse 2008; Kuna 2007; Maspero 2010; SAM 40010; SAM 40048) to 16 or 18 years (Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011; Dahl 2006; Papi 2007; Ringdal 2002).

Sponsorship and location

All the included studies were sponsored by one of the manufacturers of combined inhalers, and the duration and location of studies are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Details of the study participants, location and sponsors.

| Study ID | Number randomised | Duration | Age | Location | Sponsors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aalbers 2004 | 658 | 26 weeks (open extension) | 12+ | Europe | AstraZeneca |

| Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011 | 202 | 12 weeks | 18+ | Europe | Mundipharma |

| Busse 2008 | 1225 | 30 weeks | 12+ | USA | AstraZeneca |

| Dahl 2006 | 1397 | 24 weeks | 18+ | Europe | GlaxoSmithKline |

| Kuna 2007 | 3335 | 24 weeks | 12+ | Multinational | AstraZeneca |

| Maspero 2010 | 404 | 52 weeks | 12+ | South America | Merck |

| Papi 2007 | 228 | 12 weeks | 18+ | Europe | Chiesi |

| Ringdal 2002 | 428 | 12 weeks | 16+ | Europe | GlaxoSmithKline |

| SAM 40010 | 373 | 12 weeks | 12+ | Europe | GlaxoSmithKline |

| SAM 40048 | 248 | 12 weeks | 18+ | Germany | GlaxoSmithKline |

Risk of bias in included studies

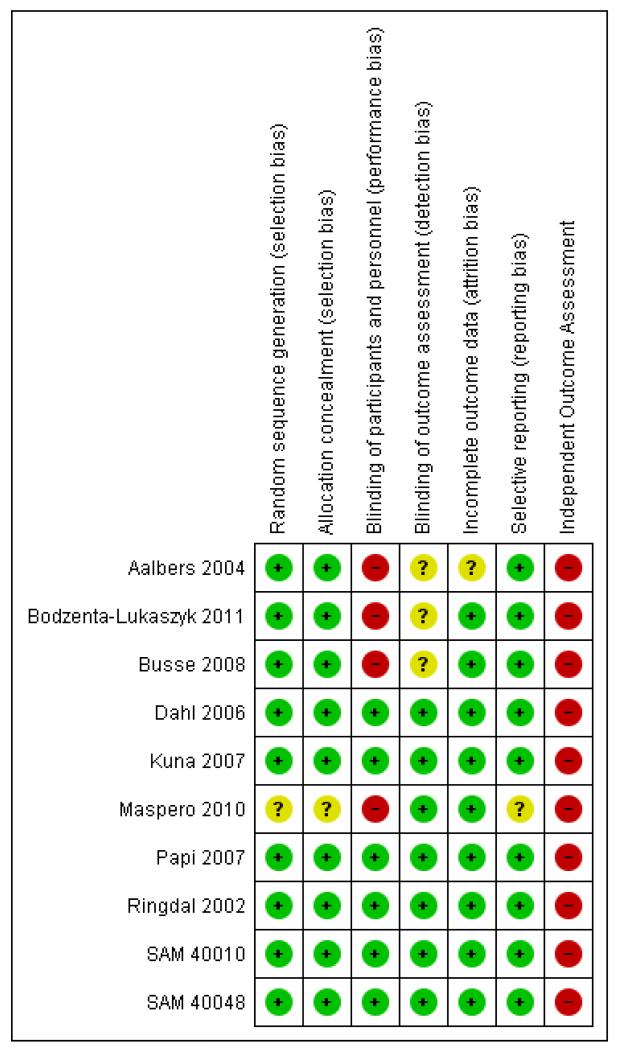

Figure 1 shows an overview of the potential risks of bias in each study

Figure 1. Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged sequence generation and allocation concealment to be adequate in six studies (Aalbers 2004; Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011; Dahl 2006; Kuna 2007; Papi 2007; Ringdal 2002). The methods used were not clearly reported in four studies (Busse 2008;Maspero 2010; SAM 40010; SAM 40048).

Blinding

Four studies had well-reported methods of blinding (Dahl 2006; Kuna 2007; Ringdal 2002; SAM 40010) and four studies were open label (Aalbers 2004; Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011; Busse 2008; Maspero 2010) but one of these (Maspero 2010) reported that there was evaluator blinding. SAM 40048 was unclear and Papi 2007 did not use a double-dummy design but encased the inhalers in a non-removable covering.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies, with the exception of Aalbers 2004, reported that at least 80% of participants completed the study and in most cases the completion rate was 90% or above (see Characteristics of included studies for details of individual studies).

Selective reporting

Full data on serious adverse events have been obtained from all studies.

Other potential sources of bias

All the studies have been sponsored by manufacturers of combined long-acting beta2-agonist and inhaled corticosteroid inhalers. None of the studies had independent assessment of the cause of serious adverse events, which may present risk of bias when considering asthma-related events (rather than all-cause events).

Effects of interventions

Formoterol/budesonide versus salmeterol/fluticasone

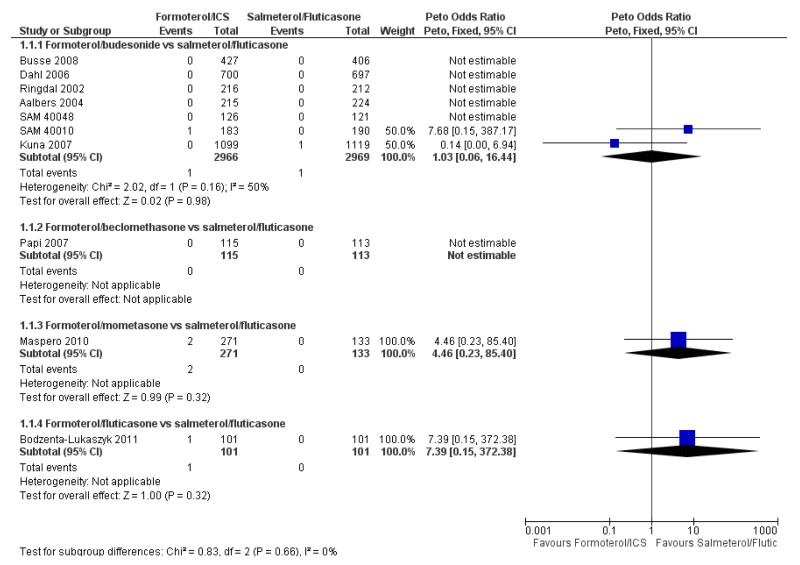

Mortality

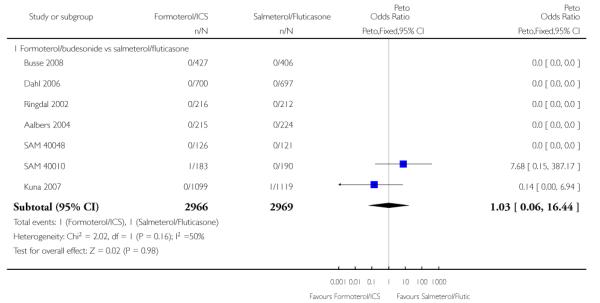

Two deaths were reported in 5935 adult and adolescent participants and neither was asthma-related. In SAM 40010 there was one death in formoterol/budesonide group due to gastrointestinal obstruction, cardiac failure and septic shock. In Kuna 2007 there was one death in the salmeterol/fluticasone group due to cardiac failure. The pooled results do not show a significant difference in all-cause mortality using Peto odds ratio (Peto OR 1.03; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06 to 16.44, I2 = 50%) (see Figure 2), or risk difference (RD 0.000009; 95% CI −0.002 to 0.002, I2 = 0%).

Figure 2. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Fixed-dose formoterol/ICS versus salmeterol/fluticasone, outcome: 1.1 All-cause mortality.

There is insufficient information to consider asthma-related or cardiovascular-related mortality (which were secondary outcomes in our protocol).

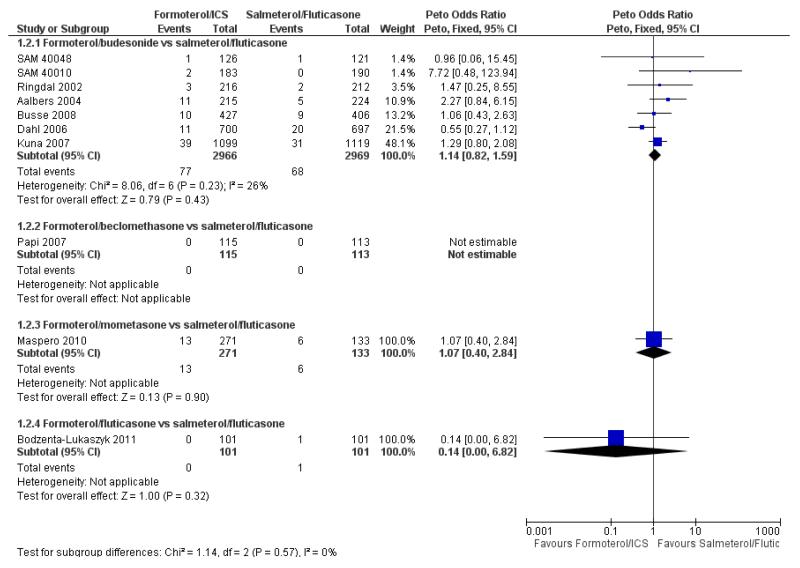

All-cause non-fatal serious adverse events

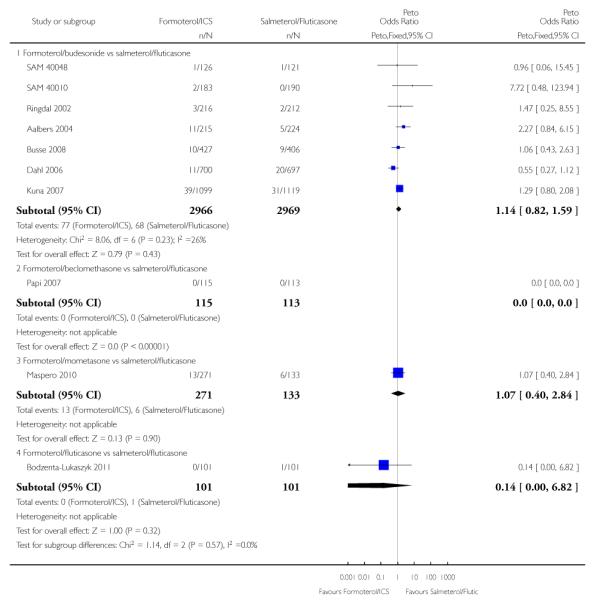

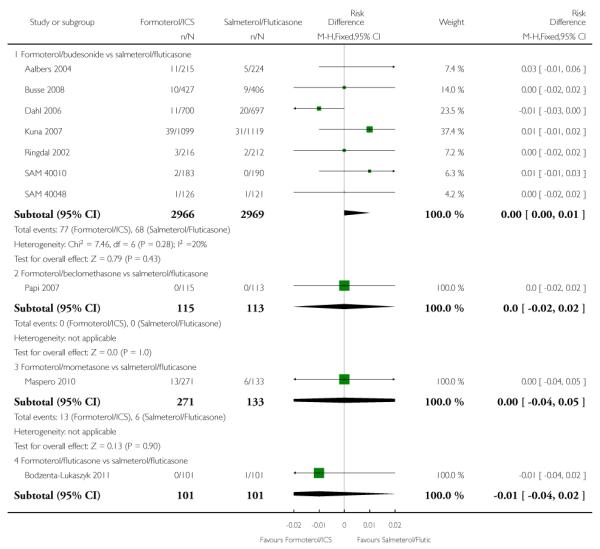

There were 77 out of 2966 adults and adolescents on formoterol and budesonide who suffered one or more serious adverse events, compared to 68 out of 2969 patients on salmeterol and fluticasone. This is not a significant difference when combined as an odds ratio (Peto OR 1.14; 95% CI 0.82 to 1.59, I2 = 26%) (see Figure 3), or as a risk difference (RD 0.003; 95% CI −0.005 to 0.011, I2 = 21%).

Figure 3. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Fixed-dose formoterol/ICS versus salmeterol/fluticasone, outcome: 1.2 All-cause non-fatal serious adverse events.

Busse 2008 reported nine participants who suffered a serious adverse event in each arm of the trial (table S4 of the paper), but one additional participant on formoterol/budesonide was admitted to hospital on treatment for an episode that was judged to have started during run-in. Another participant had a serious adverse event after the last dose of randomised treatment, but correspondence with the sponsors indicated that this participant had already suffered a serious adverse event on treatment, and so was already included. We therefore decided to enter 10 participants for the formoterol/budesonide arm of this trial. We carried out sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of excluding the additional patient in the formoterol/budesonide arm and the results showed very little difference in the odds ratio (Peto OR 1.13; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.57, I2 = 27%) as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Fixed-dose formoterol/ICS versus salmeterol/fluticasone, outcome: 1.2 All-cause non-fatal serious adverse events (without the additional participant on formoterol/budesonide in Busse 2008).

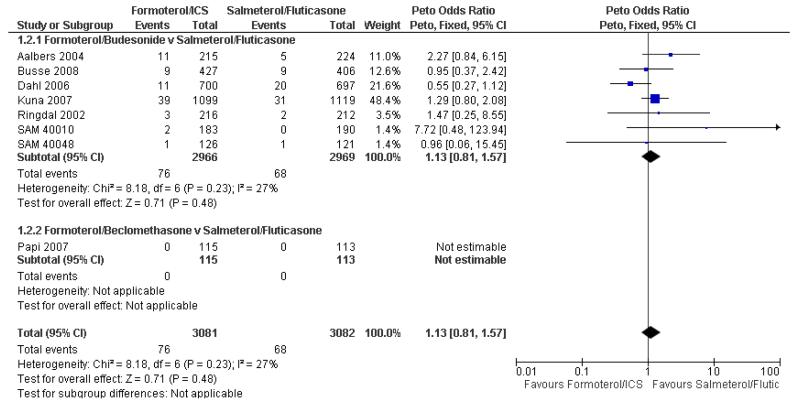

Asthma-related non-fatal serious adverse events

For two studies we were not able to find published reports of the number of patients who had suffered one or more asthma-related serious adverse events in the paper, but we were able to obtain this information from the sponsor (Busse 2008; Kuna 2007). Overall there were 17 adults and adolescents out of 2966 on formoterol and budesonide with asthma-related serious adverse events, and 25 out of 2969 on salmeterol and fluticasone. This is not a significant difference when combined as an odds ratio (Peto OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.37 to 1.26, I2 = 33%) (see Figure 5), or as a risk difference (RD −0.003; 95% CI −0.007 to 0.002, I2 = 0%).

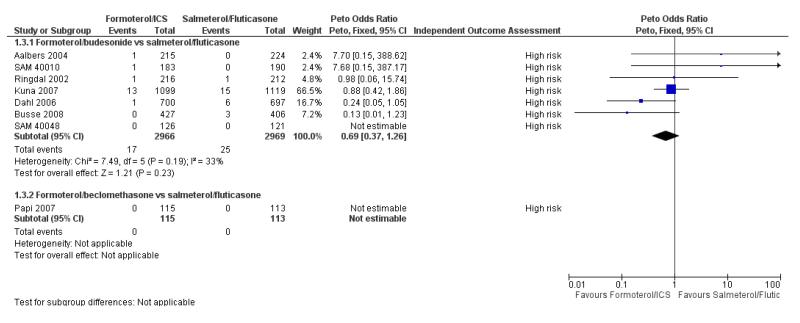

Figure 5. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Fixed-dose formoterol/ICS versus salmeterol/fluticasone, outcome: 1.3 Asthma related non-fatal serious adverse events.

The number of patients who were admitted to hospital in Dahl 2006 on salmeterol and fluticasone was recorded as four, which is lower than the six patients recorded as having asthma-related serious adverse events in this review. The reason for this difference has been clarified following correspondence with GlaxoSmithK-line and relates to one patient who suffered acute bronchospasm but was not admitted to hospital, and a second patient who was admitted to hospital but had an exacerbation that had started in the run-in period.

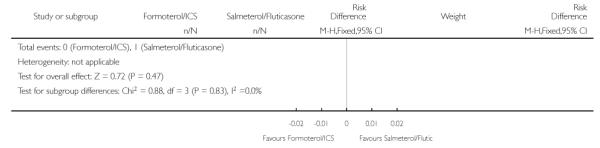

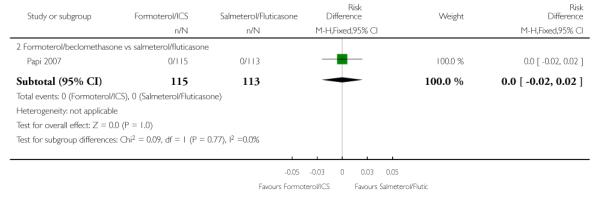

Formoterol/beclomethasone versus salmeterol/fluticasone

No serious adverse events (fatal or non-fatal) were reported in the single trial in the 228 adult participants from Papi 2007.

Formoterol/mometasone versus salmeterol/fluticasone

Mortality

Two deaths occurred in the single study of this comparison (Maspero 2010) and both were taking mometasone (see Figure 2). One was due to electrocution and one due to gastric cancer.

All-cause non-fatal serious adverse events

There were similar proportions of participants with non-fatal serious adverse events of any cause on both formoterol/mometasone and salmeterol/fluticasone, but the confidence intervals are too wide to conclude that the safety of the two products is equivalent (Peto OR 1.07; 95% CI 0.40 to 2.84) (see Figure 3).

Asthma-related serious adverse events were not reported from this study.

Formoterol/fluticasone versus salmeterol/fluticasone

One serious adverse event was reported in each arm of a single study comparing formoterol/fluticasone versus salmeterol/fluticasone in 202 adult participants from Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011. The trial report states: “Serious AEs (SAEs) were also reported for one patient in each treatment group. The SAEs experienced by the patient in the fluticasone/formoterol group (haemorrhagic stroke and cardiac arrest, approximately 2 months after randomization) led to withdrawal from the study, and had a fatal outcome. The SAE reported in the fluticasone/salmeterol group was pneumococcal pneumonia.”

These numbers are too small to make any meaningful comparison of the relative safety of the two treatments.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analysis, excluding the two unblinded studies (Aalbers 2004; Busse 2008). Restricting the analysis to the blinded studies had no impact on mortality (as there were no deaths in either of the open studies). All-cause serious adverse events in the blinded studies showed no significant difference (Peto OR 1.05; 95% CI 0.72 to 1.53, I2 = 34%), and similarly asthma-related events were also not significant (Peto OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.39 to 1.39, I2 = 23%).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was not possible on the basis of age, as there were no studies in children. We did not attempt subgroup analysis on the basis of dose equivalence of inhaled corticosteroids or long-acting beta2-agonists as the data were too sparse.

Publication bias

It was possible to obtain data on serious adverse events from all the studies. A funnel plot was not appropriate as there were fewer than 10 studies included.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

Ten studies involving adults and adolescents are included in this review. Seven of these (N = 5935) compared formoterol and budesonide to salmeterol and fluticasone, mostly using combined inhalers. One trial (N = 228) compared formoterol and beclomethasone to salmeterol and fluticasone, but this study included no hospital admissions or deaths, so it has not been possible to assess safety for this comparison. One trial (N = 404) compared formoterol and mometasone to salmeterol and fluticasone and one trial (N = 202) compared formoterol and fluticasone with salmeterol and fluticasone. There were no identified studies in children. The studies recruited participants who were previously treated with moderate to high doses of inhaled steroids.

No significant differences have been found between combination treatment on formoterol with inhaled corticosteroids and salmeterol with fluticasone for all-cause mortality in adults and adolescents, nor for non-fatal adverse events of any cause or events related to asthma.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Whilst the included studies were sufficiently powered for equivalence in terms of the primary efficacy outcomes (e.g. Papi 2007), they remain underpowered to detect possible important differences in serious adverse events (Cates 2008). Therefore, whilst no significant differences have been found between the combination inhalers, the confidence intervals are too wide to determine equivalence of safety.

Quality of the evidence

The studies were generally well protected against bias (see Figure 1). Allocation concealment and sequence generation did not present undue risk of bias in the included studies, and results on serious adverse events have been obtained from all the studies. Aalbers 2004, Bodzenta-Lukaszyk 2011, Busse 2008 and Maspero 2010 were open studies, and Aalbers 2004 had a withdrawal rate of over 20%. We carried out sensitivity analysis using only the blinded studies and there was still no significant difference between the treatments. Consideration of asthma-related adverse events might have been subject to bias as none of the trials used independent outcome assessment for causation of adverse events.

Potential biases in the review process

Since the included studies were designed to assess efficacy, it seems unlikely that publication bias would take the form of whole studies remaining unreported. It is, however, apparent that the reporting of serious adverse events in medical journals is suboptimal (Cates 2008). In this review it has been possible to obtain serious adverse event data from all studies, following correspondence with the trial sponsors. We therefore feel that there is a low risk of publication bias for this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Previous reviews have identified an increased risk of serious adverse events with regular salmeterol (Cates 2008) and regular formoterol (Cates 2008a) when compared to placebo. In contrast, in studies that used randomised inhaled corticosteroids, no significant increase in serious adverse events has been shown with regular salmeterol (Cates 2009a) or regular formoterol (Cates 2009). However, the confidence intervals in the latter reviews were too wide to conclude that the addition of an inhaled corticosteroid renders regular formoterol or salmeterol completely safe. It is in keeping with these latter reviews that we have found no significant difference between regular salmeterol and regular formoterol when used with a randomised inhaled corticosteroid in this review. The results of this review are also similar to Cates 2009b, which found no significant difference between formoterol and salmeterol in which all participants used background (rather than randomised) inhaled corticosteroids.

The negative findings may be partly an issue of statistical power, as very large numbers of patients would need to be randomised to identify small differences between salmeterol and formoterol. We do not have enough information to rule out clinically important differences between salmeterol and formoterol from the available studies, as the events are too sparse to generate tight confidence intervals.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

No significant differences have been found between formoterol and budesonide and salmeterol and fluticasone treatment in studies on 5935 adults, nor between formoterol and beclomethasone and salmeterol and fluticasone in 228 adults, nor between formoterol and mometasone and salmeterol and fluticasone in 404 adults, or between formoterol and fluticasone and salmeterol and fluticasone in 202 adults. Small numbers of patients experienced serious adverse events and the confidence intervals around the combined results are wide, so we have not been able to demonstrate whether the products are equivalent in terms of safety.

Implications for research

No safety studies comparing formoterol and salmeterol have been carried out in children. A large double-blind, double-dummy study in children comparing the combined inhalers with the same inhaled corticosteroid alone (in a four-arm, parallel-group design) is required to assess the relative safety of formoterol and salmeterol in this age group. Further research is also required to clarify the risk-benefit ratio of combination products in adults as well as children

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Do people with asthma have fewer serious adverse events when taking formoterol and inhaled corticosteroids or salmeterol and inhaled corticosteroids?

Asthma is a condition that affects the airways - the small tubes that carry air in and out of the lungs. When a person with asthma comes into contact with an asthma trigger, their airways become irritated and the muscles around the walls of the airways tighten so that the airways become narrower (bronchoconstriction) and the lining of the airways becomes inflamed and starts to swell. Sometimes, sticky mucus or phlegm builds up, which can further narrow the airways. These reactions cause the airways to become narrower and irritated - making it difficult to breathe and leading to coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath and tightness in the chest. People with asthma are generally advised to take inhaled steroids to combat the underlying inflammation, but if asthma is still not controlled, current clinical guidelines for people with asthma recommend the introduction of an additional medication to help. A common strategy in these situations is to use a long-acting beta-agonists: formoterol or salmeterol. A long-acting beta-agonist is an inhaled drug which opens the airways (bronchodilator) making it easier to breath.

We know from previous Cochrane reviews that there is a small increase in serious adverse events (such as very severe asthma attacks as well as other life-threatening events) when either of regular formoterol and regular salmeterol are compared with placebo treatment in patients who are not also taking inhaled steroids. This review sought information from trials that compared the two treatments (i.e. when people taking salmeterol with an inhaled corticosteroid were compared directly with people taking formoterol and an inhaled corticosteroid) to see if we could determine which drug was the safest.

We found 10 trials on 6769 adults and adolescents, but we did not find any trials on children. We found no significant difference between the treatments, but serious adverse events were too rare to be confident that the risks are the same for both treatments. There are no trials in children; we therefore could not draw any conclusions for children and so more trials are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the assistance of Matthew Cates with the protocol. We thank Gabriele Nicolini from Chiesi for clarification of the methodology and confirmation of results from Papi 2007, Joe Gray for confirmation of results from data on record at AstraZeneca for Busse 2008 and Kuna 2007, and Richard Follows from GlaxoSmithKline for clarification of the methodology and results from Dahl 2006, Ringdal 2002, SAM 40010 and SAM 40048.

CRG Funding Acknowledgement: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Airways Group.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

• St George’s University of London, UK.

External sources

• NIHR, UK.

Programme Grant

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON

Regular formoterol and budesonide compared to regular salmeterol and fluticasone for chronic asthma.

Patient or population: patients with chronic asthma

Settings: regular treatment at home

Intervention: regular formoterol and budesonide

Comparison: regular salmeterol and fluticasone

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Regular salmeterol and fluticasone | Regular formoterol and budesonide | |||||

|

All-cause mortality - formoterol and budesonide vs salmeterol and fluticasone

Follow-up: mean 23 weeks |

0 per 1000 2 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | OR 1.03 (0.06 to 16.44) | 5935 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕○○ low 1 | |

|

All-cause non-fatal serious adverse events - formoterol and budesonide vs salmeterol and fluticasone

Follow-up: mean 23 weeks |

23 per 1000 2 | 26 per 1000 (19 to 36) | OR 1.14 (0.82 to 1.59) | 5935 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕○ moderate 3 | |

|

Asthma related non-fatal serious adverse events - formoterol and budesonide vs salmeterol and fluticasone

Follow-up: mean 23 weeks |

8 per 1000 2 | 6 per 1000 (3 to 10) | OR 0.69 (0.37 to 1.26) | 5935 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕○○ low 3,4 | |

The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence:

High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate.

Imprecision (−2): very wide confidence intervals.

Mean risk in the salmeterol/fluticasone arms of the trials.

Imprecision (−1): wide confidence intervals.

Study limitations (−1): no independent assessment of cause of serious adverse events.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | A randomised, double-blind/opens-extension, double-dummy, multicentre, parallel-group study over 4 weeks from October 2001 to December 2002 at outpatient clinics in 93 centres in 6 countries (Denmark (9), Finland (10), Germany (11), the Netherlands (12), Norway (41) and Sweden (10)). Open run-in 10 to 14 days) The open extension period was for 6 months in which 2 arms of the study continued on fixed-dose BDF and FPS |

|

| Participants | 658 adolescents and adults (12 to 85) years with perennial asthma Baseline characteristics: mean age 46 years. FEV1 84% predicted. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants, mean dose 735 μg/day. Run-in on previous dose of ICS alone (LABA discontinued in the 28% of participants taking it previously) Inclusion criteria: aged 12 years or over with a diagnosis of perennial asthma and using between 500 to 1200 μg daily of inhaled GCS. FEV1 % predicted of 50% or greater. Must have had a total asthma symptom score of at least 1 on at least 4 of the last 7 days of the run-in period and a mean morning peak expiratory flow (PEF) during the last 7 days of the run-in period of between 50% and 85% of post bronchodilatory PEF measured at Visit 1 or 2. Run-in on previous ICS alone Exclusion criteria: respiratory infection affecting asthma within 1 month of study entry, smoking history of more than 10 pack-years, use of systemic corticosteroids within 1 month of study entry and any significant disorder which, in the opinion of the investigator, may have put the patient at risk or influenced the study |

|

| Interventions | 1. Salmeterol/fluticasone 50/250 μg bd × 1 DPI 2. Budesonide/formoterol 160/4.5 μg bd × 2 DPI 3. The third arm was on adjustable maintenance dose and not used in this review |

|

| Outcomes | The primary efficacy endpoint was the odds of having a well-controlled asthma week during the randomised treatment period. SAE reported in the paper for each group. No deaths occurred in the study (web report) | |

| Notes | Sponsored by AstraZeneca | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The randomisation schedule was generated using a computer program by a statistician independent of the study team |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Patients were consecutively allocated to the lowest available patient number and were randomised strictly sequentially in blocks |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | No blinding in the 6-month open extension period |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No details |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | 575/658 (76%) completed the study, with similar loss in all groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE reported in paper for each group |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | No independent outcome assessment |

| Methods | Study design: this was a 12-week, open-label, randomised, active-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 study, conducted at 25 centres across 5 European countries (Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania and the UK; clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00476073) | |

| Participants |

Population: 202 adults (18+) years with patients with mild-to-moderate-to-severe persistent asthma Baseline characteristics: mean age 47 years. FEV1 67% predicted. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 93% of participants Inclusion criteria: patients were required to demonstrate a FEV1 of ≥ 40% and ≤ 85% of predicted normal values (17) during the screening phase following appropriate withholding of asthma medications (if applicable). Patients were also required to show reversibility of ≥ 15% in FEV1 after salbutamol inhalation (2 actuations, 100 μg per actuation) in order to be eligible for randomisation. Only patients who could demonstrate correct inhaler technique were entered into the study Exclusion criteria: life-threatening asthma within the past year; hospitalisation or emergency department visit for asthma in the 4 weeks prior to screening; systemic corticosteroid use in the month prior to screening; omalizumab use in the past 6 months; use of a leukotriene receptor antagonist in the week before screening; a smoking history that was either recent (in the 12 months prior to screening) or equivalent to ≥ 10 pack years (e.g. at least 20 cigarettes/day for 10 years); significant non-reversible active pulmonary disease; and clinically significant respiratory tract infection in the 4 weeks prior to screening. Also prohibited was recent use (in the past week) of b-blocking agents, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, astemizole, quinidine-type antiarrhythmics or potent CYP3A4 inhibitors. Current use of medications that would have an effect on bronchospasm and/or lung function was also a criterion for exclusion |

|

| Interventions | Patients randomised to receive fluticasone/formoterol were to take 2 actuations of 50/5 μg or 125/5 μg every 12 hours (i.e. 100/10 μg or 250/10 μg twice daily). Patients randomised to receive fluticasone/salmeterol were to take 2 actuations of 50/25 μg or 125/25 μg every 12 hours (i.e. 100/50 μg or 250/50 μg twice daily). Both study treatments were administered via a hydrofluoroalkane pressurised metered-dose inhaler with an AeroChamber® Plus spacer device Patients receiving the low dose of study medication were permitted to switch to the high dose during the treatment period if their asthma was not controlled, at the investigator’s discretion |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: FEV1

SAE results reported in the paper: “Serious AEs (SAEs) were also reported for one patient in each treatment group. The SAEs experienced by the patient in the fluticasone/formoterol group (haemorrhagic stroke and cardiac arrest, approximately 2 months after randomization) led to withdrawal from the study, and had a fatal outcome. The SAE reported in the fluticasone/salmeterol group was pneumococcal pneumonia.” |

|

| Notes | Sponsored by Mundipharma Research Limited | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random permuted block design |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Eligible patients were assigned a unique randomisation number selected sequentially from a randomisation list via an interactive voice randomisation system |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Open-label |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No details |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 7% and 6% withdrawn from each arm |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE events reported in paper for each group |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | No independent outcome assessment reported |

| Methods |

Study design: a randomised, open-label, multicentre, parallel-group, Phase III study over 7 months at 145 centres in the United States. Run-in 10 to 14 days. The study comprised 3 phases: run-in (10 to 14 days), treatment period 1 (1 month, fixed-dose regimens), treatment period 2 (6 months, adjustable-dose or fixed-dose regimens). |

|

| Participants |

Population: 1225 adolescents and adults (12 to 87) years with moderate-to-severe persistent asthma Baseline characteristics: mean age 39 years. FEV1 78.7% predicted. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants. Mean dose 550 μg/day. Run-in on previous asthma therapy (ICS or LABA/ICS) Inclusion criteria: patients aged 12 years and older with a documented diagnosis of asthma, as defined by the American Thoracic Society for 6 months or more before screening and who were in stable condition. To have been maintained on a daily medium-dose ICS or ICS/LABA combination for 12 weeks or longer before screening. FEV1 % predicted of 50% or greater 6 or more hours after short-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist use and 24 or more hours after LABA use, had received 8 or more inhalations of albuterol during the last 10 days of the run-in period and demonstrated a mean morning peak expiratory flow (PEF) of between 50% and 85% of the PEF value obtained 15 minutes after albuterol pMDI (2 to 4 inhalations (90 μg per inhalation)) during the last 7 days of the run-in period. Exclusion criteria: systemic corticosteroid use within 30 days before screening, a 20 or more pack-year smoking history at screening, or a significant disease, respiratory tract infection, or illness that might interfere with the patient’s lung function or participation in the study |

|

| Interventions | 1. Fluticasone/salmeterol 250/50 μg BD DPI 2. Budesonide/formoterol 320/9 μg BD pMDI The AMD treatment arm was not included in this review |

|

| Outcomes | The primary efficacy variable was asthma control, as assessed by asthma exacerbations SAE results reported on the sponsor’s website. Uncertainty over the 2 participants mentioned in the footnotes to table S4 in the report from the trial register was resolved after correspondence with the sponsors. The participant who suffered a SAE after finishing treatment had already been counted in the formoterol/budesonide arm due to another SAE whilst on treatment, but the patient who was admitted to hospital for an episode that was judged to have started during run-in had not been included in the 9 participants on formoterol/budesonide. After discussion we therefore used 10 for this arm in our primary analysis | |

| Notes | Sponsored by AstraZeneca | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The randomisation schedule was computer-generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | The site called in to an IVRS which assigned subjects the next lowest available randomisation number |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | No blinding in 6-month study extension |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No details |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 1052/1225 (86%) completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE data found on website |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | No independent outcome assessment |

| Methods | Study design: a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, multicentre, parallel-group study over 24 weeks from November 2001 to January 2003 at 178 centres in 18 European countries. Run-in 2 weeks | |

| Participants |

Population: 1397 adults (18 to 91) years with patients with moderate-to-severe asthma Baseline characteristics: mean age 46 years. FEV1 78.6% predicted. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants. Run-in on previous dose of ICS alone; LABA (if previously used) was withdrawn during the run-in period Inclusion criteria: aged 18 years or over, with a documented clinical history of asthma of at least 6 months and receiving 1000 to 2000 μg/day of beclomethasone dipropionate or equivalent. Combination therapy, if used, was discontinued and replaced with ICS alone, at least 4 weeks prior to study start (screening visit). Bronchodilator reversibility by an increase of at least 12% in FEV1 15 min after inhaling salbutamol 200 to 400 μg. For the randomised treatment period (baseline), bronchodilator reversibility by an increase of at least 12% in FEV1 (and > 200 mL), 15 min after inhaling salbutamol 200 to 400 μg, and an asthma symptom score (day and night combined) of at least 2 (2 or more episodes of symptoms during the day/night) on at least 4 of the last 7 evaluable days of the run-in period. Exclusion criteria: suffered an upper or lower respiratory tract infection or an acute asthma exacerbation (requiring emergency treatment or hospitalisation) within 4 weeks of Visit 1; used oral corticosteroids within 4 weeks or depot steroids within 12 weeks of Visit 1; a pre-bronchodilator FEV1 % predicted of less than 50%, smoking history of 10 pack-years or more |

|

| Interventions | 1. Salmeterol/fluticasone 50/250 μg bdx 1DPI 2. Formoterol/budesonide 6/200 μg bdx 2DPI |

|

| Outcomes | The primary efficacy measure was the number of exacerbations, expressed as a rate over the 24-week treatment period SAE data described in paper only as “No deaths in the study and only a small proportion of patients reported serious AEs” SAE data obtained from sponsors website |

|

| Notes | Sponsored by GSK | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Patients were assigned to study treatment in accordance with the randomisation schedule from the Interactive Voice Recognition System, which was part of the GSK System for the Central Allocation of Medication |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Blinded study medication was packed and supplied by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). All treatment packs contained both Diskus/Accuhaler and Turbuhaler devices (either active Diskus/Accuhaler + placebo Turbuhaler, or active Turbuhaler + placebo Diskus/Accuhaler) and looked identical |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 1258/1397 (90%) completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE data found on website |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | No independent outcome assessment |

| Methods | Study design: a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, multicentre, parallel-group study over 24 weeks from December 2003 to March 2005 at 235 centres in 16 countries. Argentina (15), Australia (22), Bulgaria (9), Czech Republic (12), Great Britain (25), Hungary (27), India (7), Malaysia (4), Mexico (15), the Netherlands (24), the Philippines (8), Poland (29), South Korea (7), South Africa (26), Thailand (4), Vietnam (1). Run-in 2 weeks | |

| Participants |

Population: 3335 adolescents and adults (12 to 83) years with persistent asthma Baseline characteristics: mean age 38 years. FEV1 73% predicted. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants. Run-in on previous dose of ICS alone (LABA discontinued in the 47% of participants taking it previously) Inclusion criteria: outpatients aged 12 years or over with a diagnosis of asthma for at least 6 months and using ICS for at least 3 months. FEV1 % predicted of 50% or greater, bronchodilator reversibility by an increase of at least 12% in FEV1 following terbutaline 1 mg and at least 1 asthma exacerbation in the previous 1 to 12 months, using reliever medication on at least 5 of the last 7 days of the 2-week run-in Combination therapy, if used, was discontinued and replaced with ICS alone, at least 4 weeks prior to study start (screening visit) Exclusion criteria: patients using systemic corticosteroids or with respiratory infections affecting asthma control within 30 days of study entry were excluded |

|

| Interventions | 1. Salmeterol/fluticasone 25/125 μg bd × 2 pMDI 2. Formoterol/budesonide 12/400 μg bd × 1 DPI (reported as 9/320 delivered dose in the paper) 3. Single inhaler therapy arm not included in this review |

|

| Outcomes | The primary outcome variable was time to first severe asthma exacerbation, defined as deterioration in asthma leading to at least one of the following: - hospitalisation or emergency room treatment due to asthma, or oral corticosteroid treatment due to asthma for at least 3 days, as judged by the investigator SAE data reported in the paper and asthma-related SAE data obtained from AstraZeneca (data on file). There was 1 death in the salmeterol/fluticasone group due to cardiac failure and 1 death in the single inhaler therapy group due to respiratory failure (arm is not included in this review) |

|

| Notes | Sponsored by AstraZeneca | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The randomisation schedule was computer-generated at AstraZeneca Research and Development, Charnwood, UK. Within each centre, patients were randomised strictly sequentially as they became eligible |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Individual treatment codes and code envelopes (indicating the treatment allocation for each randomised patient) were provided, but code envelopes were to be opened only in case of medical emergencies |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 3172/3335 (95%) completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE data obtained from paper and sponsors |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | No independent outcome assessment |

| Methods | Study design: this was a 52-week, randomised, multicentre, parallel-group, open-label, evaluator-blinded study conducted at 27 clinical sites in South America | |

| Participants |

Population: 404 adults (> 12 years of age) with persistent asthma Baseline characteristics: mean age 36 years, FEV1 77% predicted, all had received ICS (with or without LABA) for at least 12 weeks Inclusion criteria: patients included in the study were 12 years or older, diagnosed with persistent asthma of ≥12 months, had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) ≥50% predicted values, received medium- or high-dose ICS with or without LABA for ≥12 weeks before screening, and were on a stable regimen for >= 2 weeks before screening. Additional inclusion criteria were evidence of β2-reversibility (increase in FEV1 of ≥ 12% and ≥ 200 mL within 10 to 15 minutes of SABA use); normal electrocardiogram (ECG), clinical laboratory tests, and chest radiograph; and adequate contraceptive precautions for women of childbearing age Exclusion criteria: patients were excluded if they demonstrated a change > 20% in FEV1; required use of >12 inhalations of SABA or two nebulised treatments with 2.5 mg salbutamol on 2 consecutive days at any time between the screening and baseline visits; experienced a clinically judged deterioration (deterioration resulting in emergency treatment, hospitalisation, or treatment with additional asthma medication other than SABA); had intraocular pressure ≥22 mmHg in either eye, glaucoma or evidence of cataract(s) at screening; was a current smoker (had smoked within the previous year) or ex-smoker (> 10 pack-years); received emergency treatment for airway obstruction in the past 3 months; or suffered a respiratory infection within 2 weeks before screening |

|

| Interventions | 1. Mometasone/formoterol 100/5 (n = 141) or 200/5 (n = 130) μg 2 puffs twice daily 2. Fluticasone/salmeterol 125/25 (n = 68) or 250/25 (n = 65) μg 2 puffs twice daily Delivered by MDI and spacers were not permitted. Dose allocated according to previous ICS use of the participant |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: adverse events | |

| Notes | Sponsored by Merck and Co. Two deaths occurred (electrocution and gastric cancer) and these were both in mometasone/formoterol 200/10 group (see FDA report at www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../UCM224593.pdf | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Open label |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Evaluator blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Over 80% completed study in each arm |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Mortality details obtained from FDA report |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | Not reported |

| Methods | Study design: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group study over 12 weeks from November 2004 to June 2005 at 12 outpatient respiratory clinics in Europe (Poland (6) Ukraine (6)). Run-in 2 weeks | |

| Participants |

Population: 228 adults (18 to 65) years with moderate to severe persistent asthma. Baseline characteristics: mean age 48 years. FEV1 67% predicted. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants. Average ICS dose 731 μg/day (BDP equivalent). Run in on ICS alone (no other anti-asthma medication permitted) Inclusion criteria: clinical diagnosis of moderate to severe persistent asthma for at least 6 months, FEV1 % predicted between 50% to 80%, bronchodilator reversibility by an increase of at least 12% in FEV1 (or, alternatively, of 200 ml) over baseline measured 30 min after 2 puffs (2 × 100 μg) of inhaled salbutamol administered via pMDI. Treated with ICS at a daily dose of less than 1000 μg of BDP-equivalent and had asthma symptoms not adequately controlled as defined by: presence of daily symptoms at least once a week, night-time symptoms at least twice a month and daily use of short-acting beta2-agonists. Exclusion criteria: COPD, current or ex-smokers (more than 10 pack-years); severe asthma exacerbation or symptomatic infection of the airways in the previous 8 weeks; more than 3 courses of oral corticosteroids or hospitalisation due to asthma in the previous 6 months; treatment with LABAs, anticholinergics or antihistamines in the previous 2 weeks, and/or with topical or intranasal corticosteroids and leukotriene antagonists in the previous 4 weeks, change of ICS dose in the previous 4 weeks |

|

| Interventions | 1. Beclomethasone/formoterol 100/6 μg × 2 bd 2. Fluticasone/salmeterol 125/25 μg × 2 bd Delivery was via pMDI |

|

| Outcomes | The primary outcome variable was morning predose PEF measured by patients in the last 2 weeks of treatment period (weeks 11 and 12). No serious adverse events reported in either arm of the trial and the absence of deaths and hospitalisations has been confirmed by Chiesi; no details of one of the patients withdrawn due to “Development of an exclusion criteria” | |

| Notes | Sponsored by Chiesi | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was in balanced-block design stratified by centres |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Each patient was identified with a randomisation number, from 001 to 260 (in blocks of four); each investigator assigned the lowest available randomisation number at each site.” |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Described as double-blind but not double-dummy and inhalers were different shape and size but this was “masked” using a non-removable external covering for the inhalers |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Described as double-blind but not double-dummy and inhalers were different shape and size but this was “masked” using a non-removable external covering for the inhalers |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 225/228 (99%) completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | “During the study no deaths or hospitalizations occurred.” Data on file at Chiesi |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | No independent outcome assessment |

| Methods | Study design: a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, multicentre, parallel-group study over 12 weeks from May 1998 to June 1999 at 52 primary care practices and hospital respiratory units in 11 countries (Austria (4), Belgium (4), Croatia (2), Denmark (4), Finland (2), Germany (7), Italy (3), Norway (5), Russia (2), Slovakia (3), United Kingdom (16)). Run-in 2 weeks | |

| Participants |

Population: 428 adolescents and adults (16 to 75) years with moderate-to-severe asthma who were uncontrolled on existing corticosteroid therapy Baseline characteristics: mean age 47 years. FEV1 69% predicted. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants. Run-in on previous dose of ICS (no LABA allowed in previous 2 weeks before recruitment). Inclusion criteria: aged 16 to 75 years with a documented clinical history of asthma currently receiving 1000 to 1600 μg/day of budesonide, beclomethasone dipropionate or flunisolide, or 500 to 800 μg/day fluticasone propionate, for at least 4 weeks before Visit 1 At the end of run-in, FEV1 % predicted of 50% to 85% at any of Visits 1 or 2/2A (bronchodilators withheld for 6 hours), bronchodilator reversibility by an increase of at least 15% in FEV1 over baseline 15 minutes after inhaling 400 μg of salbutamol at Visit 1 or 2/2A, and a symptom score (day and night combined) of at least 2 or relief bronchodilator use on at least 2 separate occasions (any dose) per day on at least 4 of the last 7 days of the run-in period Exclusion criteria: a smoking history of 10 pack-years or more, an asthma exacerbation or upper or lower respiratory tract infection within the previous month, systemic or nasal steroids or anti leukotrienes within the previous 4 weeks, or long-acting/oral/slow-release beta2-agonists in the previous 2 weeks before Visit 1 |

|

| Interventions | 1. Salmeterol/fluticasone 50/250 μg bd via Diskus 2. Formoterol (12 μg bd) + budesonide (800 μg bd) via separate turbohalers |

|

| Outcomes | The primary efficacy measure was mean PEFam over the week prior to the end of treatment (Week 12) SAE data obtained from sponsor’s website and also reported in the paper publication |

|

| Notes | Sponsored by GSK | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A randomisation code was generated using the Glaxo Wellcome computer program ‘Patient Allocation for Clinical Trials’ (block size of 4) and non-overlapping sets of treatment numbers were allocated to each centre. Treatment numbers were allocated at Visit 2 in consecutive order, starting with the lowest number available at that centre |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Numbered treatment packs of study drugs were labelled to ensure that both patients and investigators were blinded to the treatment allocation, and the randomisation codes were not revealed to investigators or other study participants until after recruitment, treatment, data collection and analyses were complete |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 379/428 (89%) completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE reported in paper and on sponsor’s trial report |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | No independent outcome assessment |

| Methods | Study design: a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, multicentre, parallel-group study over 12 weeks from January 2000 to July 2000 at 50 centres in Europe (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Poland and The Netherlands). Run-in 2 to 4 weeks | |

| Participants |

Population: 373 adolescents and adults with asthma that is poorly controlled by low doses of inhaled corticosteroid Baseline characteristics: mean age 42 years. Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants. No details of treatment given during run-in Inclusion criteria: aged 12 years and older with reversible airways obstruction who remained symptomatic with inhaled corticosteroid treatment (400 to 500 μg/day budesonide or equivalent), for at least 4 weeks prior to Visit 1 (start of the run-in period), had a clinical history of asthma with symptoms including cough, wheeze and shortness of breath requiring treatment with short-acting beta2-agonist for a period of at least 6 months, a mean morning PEF during the last 7 consecutive days of the run-in period of between 50% and 85% of their PEF measured 15 minutes after administration of 400 μg of salbutamol at Visit 1, and had recorded a cumulative total symptom score (daytime plus night-time) of at least 8 for the last 7 consecutive days of the run-in period Exclusion criteria: not reported |

|

| Interventions | 1. Salmeterol/fluticasone 50/100 μg bd via Diskus 2. Budesonide 200 μg bd + formoterol 6 μg bd via DPI |

|

| Outcomes | The primary study endpoint was morning peak expiratory flow, assessed as the mean of the morning PEF values recorded during the 12-week treatment period. SAE data available from web report. One death in formoterol/budesonide group due to gastrointestinal obstruction, cardiac failure and septic shock | |

| Notes | Sponsored by GSK | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation code was computer-generated using Patient Allocation for Clinical Trials developed by GlaxoSmithKline research and development |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Treatment numbers were assigned sequentially to all eligible subjects starting with the lowest number available to the investigator |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 362/373 (97%) completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE data presented in web report |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | No independent outcome assessment |

| Methods | Study design: a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, multicentre, parallel-group study over 12 weeks from August 2001 to September 2002 at 27 centres in Germany. Run-in 2 weeks | |

| Participants |

Population: 248 adults with moderate bronchial asthma. Baseline characteristics: mean age 48 years. FEV1 65% predicted (at Visit 2 (baseline)). Concomitant inhaled corticosteroids used by 100% of participants. No details of treatment given during run-in Inclusion criteria: aged 18 years and older with moderate asthma. FEV1 % predicted between 50% to 80%, bronchodilator reversibility by an increase of at least 15% in FEV1, inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) treatment 1000 μg beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP)/day or equivalent; and symptomatic asthma Exclusion criteria: exacerbations or emergency visits during the 4-week pre-study period and smoking (more than 20 cigarettes per day) |

|

| Interventions | 1. Salmeterol/fluticasone 50/250 μg bd via Diskus 2. Formoterol/budesonide 6/200μg bd via DPI |

|

| Outcomes | The primary variable was the change in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (% predicted), after 12 weeks of treatment compared to baseline SAE data in web report | |

| Notes | Sponsored by GSK | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “The allocation of patients to the two treatment groups was undertaken according to a predetermined randomisation schedule (in a ratio of 1 to 1).” GSK data on file |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “The allocation was undertaken as a block randomisation, with identical allocation ratios in each study centre. Every investigator had to allocate the patient to the lowest available number at visit 2. Adherence to this randomisation schedule was checked during the process of data management.” |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind, double-dummy |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 235/248 (95%) completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | SAE data in web report |

| Independent Outcome Assessment Asthma-related serious adverse events |

High risk | No independent outcome assessment |

AMD: adjustable maintenance dosing

BDF: budesonide

DPI: dry powder inhaler

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

FDA: Food and Drug Administration

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second

FPS: fluticasone propionate and salmeterol inhaler

GCS: glucocorticosteroid

GSK: GlaxoSmithKline

IVRS: Interactive voice recording system

LABA: long-acting beta2-agonist

PEF: peak expiratory flow

pMDI: pressurised metered-dose inhaler

SABA: short-acting beta2-agonist

SAE: serious adverse event

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Bleecker 2008 | Review of 2 other studies (Busse 2008; Kuna 2007) |

| Dhillon 2006 | Review of studies on BDP/formoterol |

| Hampel 2008 | Single-dose study |

| Jung 2008 | Fluticasone/salmeterol versus current care |

| Lee 2003 | 4-week cross-over study |

| Lyseng-Williamson 2003 | Pharmacoeconomic review of studies on fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler |

BDP: beclometasone

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1. Fixed-dose formoterol/ICS versus salmeterol/fluticasone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All-cause mortality | 10 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Formoterol/budesonide vs salmeterol/fluticasone | 7 | 5935 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.06, 16.44] |

| 1.2 Formoterol/beclomethasone vs salmeterol/fluticasone | 1 | 228 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |