Abstract

Background

Epidemiological evidence has suggested a link between beta2‐agonists and increases in asthma mortality. There has been much debate about possible causal links for this association, and whether regular (daily) long‐acting beta2‐agonists are safe.

Objectives

The aim of this review is to assess the risk of fatal and non‐fatal serious adverse events in trials that randomised patients with chronic asthma to regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular short‐acting beta2‐agonists.

Search methods

We identified trials using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials. We checked websites of clinical trial registers for unpublished trial data and FDA submissions in relation to salmeterol. The date of the most recent search was August 2011.

Selection criteria

We included controlled parallel design clinical trials on patients of any age and severity of asthma if they randomised patients to treatment with regular salmeterol and were of at least 12 weeks' duration. Concomitant use of inhaled corticosteroids was allowed, as long as this was not part of the randomised treatment regimen.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected trials for inclusion in the review. One author extracted outcome data and the second checked them. We sought unpublished data on mortality and serious adverse events.

Main results

The review includes 26 trials comparing salmeterol to placebo and eight trials comparing with salbutamol. These included 62,815 participants with asthma (including 2,599 children). In six trials (2,766 patients), no serious adverse event data could be obtained.

All‐cause mortality was higher with regular salmeterol than placebo but the increase was not significant (Peto odds ratio (OR) 1.33 (95% CI 0.85 to 2.08)). Non‐fatal serious adverse events were significantly increased when regular salmeterol was compared with placebo (OR 1.15 95% CI 1.02 to 1.29). One extra serious adverse event occurred over 28 weeks for every 188 people treated with regular salmeterol (95% CI 95 to 2606). There is insufficient evidence to assess whether the risk in children is higher or lower than in adults. We found no significant increase in fatal or non‐fatal serious adverse events when regular salmeterol was compared with regular salbutamol.

We combined individual patient data from the two largest studies (SNS: n=25,180 and SMART: n=26,355), as all the asthma‐related deaths in adults occurred in these studies. In patients who were not taking inhaled corticosteroids, compared to regular salbutamol or placebo, there was a significant increase in risk of asthma‐related death with regular salmeterol (Peto OR 6.15 95% CI 1.73 to 21.84). The confidence interval for patients who were taking inhaled corticosteroids is wide and cannot rule in or out an increase in asthma mortality in the presence of an inhaled corticosteroid (Peto OR 2.03 95% CI 0.82 to 5.00).

Authors' conclusions

In comparison with placebo, we have found an increased risk of serious adverse events with regular salmeterol. There is also a clear increase in risk of asthma‐related mortality in patients not using inhaled corticosteroids in the two large surveillance studies. Although the increase in asthma‐related mortality was smaller in patients taking inhaled corticosteroids at baseline, the confidence interval is wide, so we cannot conclude that the inhaled corticosteroids abolish the risks of regular salmeterol. The adverse effects of regular salmeterol in children remain uncertain due to the small number of children studied.

Keywords: Adult, Child, Humans, Adrenergic beta‐Agonists, Adrenergic beta‐Agonists/therapeutic use, Albuterol, Albuterol/administration & dosage, Albuterol/adverse effects, Albuterol/analogs & derivatives, Albuterol/therapeutic use, Anti‐Asthmatic Agents, Anti‐Asthmatic Agents/administration & dosage, Anti‐Asthmatic Agents/adverse effects, Asthma, Asthma/drug therapy, Asthma/mortality, Bronchodilator Agents, Bronchodilator Agents/administration & dosage, Bronchodilator Agents/adverse effects, Cause of Death, Placebos, Placebos/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Salmeterol Xinafoate

Plain language summary

Does daily treatment with salmeterol result in more serious adverse events compared with placebo or a salbutamol?

Asthma is a common condition that affects the airways – the small tubes that carry air in and out of the lungs. When a person with asthma comes into contact with an irritant (an asthma trigger), the muscles around the walls of the airways tighten, the airways become narrower, and the lining of the airways becomes inflamed and starts to swell. This leads to the symptoms of asthma ‐ wheezing, coughing and difficulty in breathing. They can lead to an asthma attack or exacerbation. People can have underlying inflammation in their lungs and sticky mucus or phlegm may build up, which can further narrow the airways. There is no cure for asthma; however there are medications that allow most people to control their asthma so they can get on with daily life.

Long‐acting beta2‐agonists, such as salmeterol, work by reversing the narrowing of the airways that occurs during an asthma attack. These drugs ‐ taken by inhaler ‐ are known to improve lung function, symptoms, quality of life and reduce the number of asthma attacks. However, there are concerns about the safety of long‐acting beta2‐agonists, particularly in people who are not taking inhaled corticosteroids to control the underlying inflammation. We did this review to take a closer look at the safety of people taking salmeterol daily compared to people on placebo or the short acting beta2‐agonist salbutamol.

There was no statistically significant difference in the number of people who died during treatment with salmeterol compared with placebo or salbutamol. Because so few people die of asthma, huge trials or observational studies are normally required to detect a difference in death rates from asthma. There were more non‐fatal serious adverse events in people taking salmeterol compared to those on placebo; for every 188 people treated with salmeterol for 28 weeks, one extra non‐fatal event occurred in comparison with placebo. There was no significant differences in serious adverse events in people on salmeterol compared to regular salbutamol.

In order to obtain individual patient data on asthma deaths, we looked separately at mortality in two large trials on over 51,000 patients who were not taking inhaled corticosteroids, and found that there was an increase in the number of asthma‐related deaths among people on salmeterol.

We conclude that, for patients whose asthma is not well‐controlled on moderate doses of inhaled corticosteroids, additional salmeterol can improve symptoms but this may be at the expense of an increased risk of serious adverse events and asthma related mortality. Salmeterol should not be used as a substitute for inhaled corticosteroids, and adherence with inhaled steroids should be kept under review if separate inhalers are used. Salmeterol should not be taken by people who are not taking regular inhaled steroids due to the increased risk of asthma‐related death.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Regular salmeterol compared to placebo for chronic asthma.

| Regular salmeterol compared to placebo for chronic asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with chronic asthma Settings: Intervention: regular salmeterol Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| placebo | Regular salmeterol | |||||

| All‐cause mortality ‐ adults and adolescents Follow‐up: mean 28 weeks | 2 per 10001 | 3 per 1000 (2 to 4) | OR 1.33 (0.85 to 2.08)2 | 29128 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | Two studies (27,266 participants) reported that deaths had occurred, and 96% of these were in the SMART study. |

| All‐cause mortality ‐ children | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 1126 (4) | See comment | There were no deaths in children during 793 patient years of observation |

| All‐cause non‐fatal serious adverse events ‐ adults and adolescents Follow‐up: mean 28 weeks | 34 per 10001 | 39 per 1000 (34 to 43) | OR 1.14 (1.01 to 1.28) | 30,196 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | 92% of events occurred in the SMART study |

| All‐cause non‐fatal serious adverse events ‐ children Follow‐up: mean 31 weeks | 56 per 10001 | 72 per 1000 (46 to 108) | OR 1.3 (0.82 to 2.05) | 1333 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Asthma‐related mortality ‐ adults and adolescents Follow‐up: mean 28 weeks | Medium risk population | OR 3.49 (1.31 to 9.31) | 29,128 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Mean risk of asthma death in placebo arm of trials was 2 in 10,000 and 9 in 10,000 for salmeterol arm of trials | |

| 0 per 10001 | 1 per 1000 (0 to 2) | |||||

| Asthma‐related non‐fatal serious adverse events ‐ adults and adolescents Follow‐up: mean 28 weeks | 9 per 10001 | 13 per 1000 (7 to 24) | OR 1.43 (0.75 to 2.71) | 3841 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | |

| Asthma‐related non‐fatal serious adverse events ‐ children Follow‐up: mean 31 weeks | 33 per 10001 | 55 per 1000 (33 to 92) | OR 1.72 (1 to 2.98) | 1333 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Assumed risks on control are taken from the mean risk in control arms of included trials 2 Risk ratios can be considered to be the same as odds ratios as event rates are very low 3 Few events were observed leading to wide CIs (including the possibilities of no effect and appreciable harm) 4 There was no independent assessment of the cause of serious adverse events, leading to possible ascertainment bias for disease‐specific outcomes

Summary of findings 2. Regular salmeterol compared to regular salbutamol for chronic asthma.

| Regular salmeterol compared to regular salbutamol for chronic asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with chronic asthma Settings: Intervention: regular salmeterol Comparison: regular salbutamol | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| regular salbutamol | Regular salmeterol | |||||

| All‐cause mortality ‐ adults and adolescents Follow‐up: mean 16 weeks | 2 per 10001 | 3 per 1000 (2 to 4) | OR 1.28 (0.79 to 2.05)2 | 26,463 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| All‐cause mortality ‐ children Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | 3 per 10001 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 9) | OR 0.04 (0 to 2.97) | 1152 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | A single death occurred in 273 patient‐years of observation in children |

| All‐cause non‐fatal serious adverse events ‐ adults and adolescents Follow‐up: mean 16 weeks | 43 per 10001 | 41 per 1000 (37 to 47) | OR 0.96 (0.85 to 1.1) | 27,002 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | |

| All‐cause non‐fatal serious adverse events ‐ children Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | 28 per 10001 | 38 per 1000 (20 to 71) | OR 1.37 (0.71 to 2.64) | 1181 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Asthma‐related mortality ‐ adults and adolescents Follow‐up: mean 16 weeks | Medium risk population | OR 2.36 (0.78 to 7.16) | 26,463 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | The mean risk of death from asthma was 2 per 10,000 on the regular salbutamol arms of the trials and 7 per 10,000 on the regular salmeterol arms. | |

| 0 per 10001 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 1) | |||||

| Asthma‐related non‐fatal serious adverse events ‐ adults and adolescents Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | 17 per 10001 | 16 per 1000 (6 to 39) | OR 0.94 (0.37 to 2.34) | 1155 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,5 | |

| Asthma‐related non‐fatal serious adverse events ‐ children Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | 23 per 10001 | 24 per 1000 (11 to 52) | OR 1.04 (0.47 to 2.31) | 1186 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,5 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Assumed risks on control are taken from the mean risk in control arms of included trials 2 Risk ratios can be considered to be the same as odds ratios as event rates are very low 3 Few events were observed leading to wide CIs (including the possibilities of no effect and appreciable harm) 4 The CI includes the possibility of no difference between treatments but is too wide to consider that the risks are equivalent 5 There was no independent assessment of the cause of serious adverse events, leading to possible bias in the ascertainment of disease‐specific outcomes

Background

Description of the condition

There is currently no universally accepted definition of the term "asthma". This is in part due to an overlap of asthmatic symptoms with those of other diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), but is also due to the probable existence of more than one underlying pathophysiological process. There are, for example, wide variations in the age of onset, symptoms, triggers, associations with allergic disease and the type of inflammatory cell infiltrate seen in patients diagnosed with severe asthma (Miranda 2004). Patients with all forms and severity of disease will typically have intermittent symptoms of cough, wheeze and/or breathlessness. Underlying these symptoms there is a process of variable, at least partially reversible airway obstruction, airway hyper responsiveness and, in most cases, chronic inflammation.

Airway obstruction

Patients with a history of asthma demonstrate chronic changes within the airways including goblet cell hyperplasia, airway smooth muscle (ASM) hyperplasia and hypertrophy (Ebina 1993; Ordonez 2001; Woodruff 2004) and excess myofibroblasts with increased subepithelial collagen deposition (Brewster 1990). In the acute setting, in patients who have died of status asthmaticus airway obstruction is evident from air‐trapping and lung hyperinflation with mucus plugging of the small and large airways (Dunnill 1960; Kuyper 2003). There is also shedding of ciliated bronchial mucosal cells, inflammatory cell infiltrates and submucosal oedema with transudation of fluid into the bronchial lumen (Carroll 1993). It is more difficult to measure the degree of ASM contraction (bronchoconstriction) at post‐mortem studies although evidence for a role of bronchoconstriction in airway narrowing comes from other sources.

Airway hyper responsiveness

Patients with asthma typically display a degree of 'airway hyper responsiveness' to inhaled allergens (Cockcroft 2006), and to a variety of chemical stimuli including histamine, serotonin, bradykinin, prostaglandins, methacholine and acetylcholine as well as other triggers such as exercise, deep inhalation and inhalation of cold air (Boushey 1980). Bronchoconstriction is implicated as the primary effector mechanism of airway narrowing in these responses. This is because of both the short time frame of the response and because many of these stimuli typically either cause bronchoconstriction directly in vitro or promote bronchoconstriction through interference with the autonomic control of ASM. Further evidence comes from findings that this response can be abolished or diminished by bronchodilator medications such as atropine and beta2‐agonists (Phillips 1990; Simonsson 1967); although beta2‐agonists in particular may have additional mechanisms of action. Whether airway hyper responsiveness relates primarily to an abnormality of ASM, to increased ASM bulk (Wiggs 1990), to aberrant autonomic control or reflex pathways, or to physical damage to the airway epithelium remains to be established. Regular use of salbutamol has, however, been shown to increase airway hyper responsiveness to allergen exposure and produce tolerance to the protective effect of salbutamol against bronchoconstriction induced by both methacholine and allergens (Cockcroft 1993).

Inflammation

It has long been thought that the histological changes described above and the phenomenon of airway hyper responsiveness are due to a combined acute and chronic inflammatory response (Bousquet 2000). Patients with status asthmaticus have increased numbers of inflammatory cells including eosinophils and neutrophils, as well as a variety of pro‐inflammatory cytokines and chemokines found in bronchial alveolar lavage (Tonnel 2001). In patients with chronic asthma there is also evidence of increased eosinophil numbers (Bousquet 1990), inflammatory cell adhesion molecules (Vignola 1993) and some evidence of an association between the extent of inflammation, disease severity and hyperreactivity. This association has however been questioned on the background of a number of negative results (Brusasco 1998), although it is made difficult to prove by the lack of a consistent marker of a sequential and variable inflammatory response (Haley 1998).

Description of the intervention

Beta2‐agonists and mortality: an historical perspective

Time trend data and case control studies

Adrenaline was successfully used in the symptomatic treatment of asthma as far back as 1903 (Tattersfield 2006). Initially given subcutaneously, the inhaled route was tried in 1929 to reduce adverse effects but these remained a problem and in 1940 details of a new agent isoprenaline (isoproterenol) were published in Germany (Konzett 1940). Although isoprenaline was more selective for beta‐ as opposed to alpha‐adrenoreceptors, adverse effects including palpitations were still a major problem, particularly with oral administration (Gay 1949) and it first became available as atomizer spray for use in the UK in 1948 (Pearce 2001).

Prior to the 1940s, mortality rates from asthma in a number of countries were stable and low at less than one asthma death per 100,000 people per year (Pearce 2001; Figure 1). During the 1940s and 50s, there was a slight rise in mortality rates and concerns about a possible link to inhaled adrenaline were raised at an early stage (Benson 1948). However, the rise was small and the cause unclear and sales continued to increase with the introduction of aerosol or metered dose inhalers in the early 1960s. During this decade, there was an epidemic of asthma deaths in at least six countries including England, Wales and New Zealand (Figure 1). In all six countries the epidemics coincided with the licensing of an aerosol called 'Isoprenaline Forte', which contained five times the dose of isoprenaline per administration than the standard preparation (Stolley 1972). In other countries including the Netherlands where isoprenaline forte was introduced late and sales volumes low and in the US, where isoprenaline forte was not licensed, no increase in asthma mortality occurred. This was despite an approximate trebling in per capita alternative bronchodilator sales between 1962 and 1968 in the US (Stolley 1972). A detailed review of the epidemic in England and Wales concluded it was not due to changes in death certification, disease classification or an increase in asthma prevalence, but instead was most likely due to new methods of treatment (Speizer 1968). In England and Wales, mortality rates fell following health warnings about the overuse of inhalers and banning of over the counter sales in 1968. It was around this time that more selective beta2‐agonists such as terbutaline (Bergman 1969) and salbutamol (albuterol) (Cullum 1969) were being developed.

1.

Changes in asthma mortality (5‐34 age group) in three countries in relation to the introduction of isoprenaline forte in the UK and New Zealand and of fenoterol in New Zealand. (From Blauw 1995. With permission from the Lancet.)

In the late 1970s, a second epidemic of asthma deaths occurred in New Zealand (Figure 1). It was later shown that this epidemic coincided with the introduction and rising sales of fenoterol, a new short‐acting beta2‐agonist (Crane 1989; Figure 2). A significant association between mortality and fenoterol use was demonstrated in three consecutive case‐control studies, the latter studies addressing criticisms of the first (Crane 1989; Grainger 1991; Pearce 1990). Furthermore, the relative risk of asthma death in patients prescribed fenoterol increased markedly when analysis was restricted to subgroups defined by markers of severity, including previous hospital admission and use of oral corticosteroids. Following the publication of the first case control study, the fenoterol market share in New Zealand fell from 30% in 1988 to 3% in 1991 and by the early 1990s the mortality epidemic appeared to be over (Figure 2). During the gradual decline in mortality in New Zealand from its peak in 1979, total sales of alternative beta2‐agonists, including salbutamol, gradually rose and the use of inhaled corticosteroids also increased during the latter half of the 1980s (Pearce 2007).

2.

Inhaled fenoterol market share and annual asthma mortality in New Zealand in persons aged 5‐34.

The introduction of long‐acting beta2‐agonists

Given the relatively short‐lived action of beta2‐agonists such as salbutamol, in the late 1980s efforts were made to develop longer‐acting compounds. Subsequently, the long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABAs), salmeterol and formoterol were released by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Novartis, respectively. Both drugs cause bronchodilation that lasts for more than 12 hours, although formoterol has a faster onset of action (Kemp 1993; Ringdal 1998). Given previous concerns about the safety profile of some of the short acting beta2‐agonists, salmeterol and formoterol were subject to randomised controlled trials on larger numbers of patients. Using these trials, several Cochrane reviews have addressed the efficacy of LABAs in addition to inhaled corticosteroids (Ni Chroinin 2004; Ni Chroinin 2005), in comparison with placebo (Walters 2007), short‐acting beta2‐agonists (Walters 2002), leukotriene‐receptor antagonists (Ducharme 2006), and increased doses of inhaled corticosteroids (Greenstone 2005). The beneficial effects of LABAs on lung function, symptoms, quality of life and exacerbations requiring oral steroids have been demonstrated. However, with some studies demonstrating an associated increase in mortality, concerns about the safety profile of LABAs have heightened and there has been much debate about the potential protective role of inhaled corticosteroids.

How the intervention might work

We have outlined the pharmacology of beta2‐agonists in detail in Appendix 1. Since the early epidemics in asthma mortality, a number of potential mechanisms have been proposed to explain a relationship to the use of beta2‐agonists. We discuss these mechanisms in detail in Appendix 2; they include direct toxicity, tolerance, delay in seeking help and reduction in use of inhaled corticosteroids.

Why it is important to do this review

We have taken a different approach from Salpeter 2006, in that we have not assumed a class effect of long‐acting beta2‐agonists, but we have considered trials comparing regular salmeterol to placebo or regular salbutamol. We have chosen not to include results from trials on formoterol in this review, as there are known differences in the pharmacology properties of salmeterol and formoterol (Van Noord 1996); however formoterol is the subject of another ongoing review.

In view of the difficulty in ascertaining the causation of deaths and serious adverse events (SAEs), we have considered all‐cause fatal and non‐fatal SAEs as the main outcomes of this review, with asthma‐related and cardiovascular events as secondary outcomes.

Objectives

The aim of this review is to assess the risk of mortality and non‐fatal serious adverse events in trials which randomised patients with chronic asthma to salmeterol alone

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of parallel design, with or without blinding, in which salmeterol alone was randomly assigned to patients with chronic asthma. We excluded studies on people with acute asthma and exercise‐induced bronchospasm.

Types of participants

We included patients with a clinical diagnosis of asthma of any age group, unrestricted by disease severity, previous or current treatment.

Types of interventions

We included trials that randomised participants to receive inhaled salmeterol twice daily for a period of at least 12 weeks, at any dose and delivered by any device (metered dose inhalers (MDIs) with chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) or hydrofluoroalkane (HFAs), or dry powder inhalers (DPIs). We included studies that used comparison groups with placebo or short‐acting beta2‐agonists, and co‐intervention with leukotriene receptor antagonists; inhaled or oral corticosteroids or theophylline was allowed as long as they were not part of the randomised intervention, and were therefore not systematically different between groups. We excluded studies that compared different doses of salmeterol or different delivery devices or propellants (with no placebo arm). We excluded studies in which salmeterol was randomised together with an inhaled steroid (in separate inhalers or a combined inhaler), but these studies were included in a separate review (Cates 2009).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

All‐cause non‐fatal SAEs

Secondary outcomes

Asthma‐related mortality

Asthma‐related non‐fatal SAEs

Respiratory‐related mortality

Respiratory‐related non‐fatal SAEs

Cardiovascular‐related mortality

Cardiovascular‐related non‐fatal SAEs

Asthma‐related non‐fatal life‐threatening events (intubation or admission to intensive care)

Respiratory‐related non‐fatal life‐threatening events (intubation or admission to intensive care)

We did not sub‐divide outcomes according to whether the trial investigators considered them to be related to trial medication.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (see Appendix 3 for details). All records in the Specialised Register coded as 'asthma' were last searched in August 2011 using the following terms:

(((beta* and agonist*) and (long‐acting or "long acting")) or ((beta* and adrenergic*) and (long‐acting or "long acting")) or (bronchodilat* and (long‐acting or "long acting")) or (salmeterol or formoterol or eformoterol or advair or symbicort or serevent or seretide or oxis)) AND (serious or safety or surveillance or mortality or death or intubat* or adverse or toxicity or complications or tolerability)

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We checked websites of clinical trial registers for unpublished trial data and FDA submissions in relation to salmeterol.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Both authors (CJC, MJC) independently assessed studies identified in the literature searches by examining titles, abstract and keywords fields. We obtained studies that potentially fulfilled the inclusion criteria in full text. We independently assessed these full text trial reports for inclusion. We resolved disagreements by consensus. We kept a record of decisions.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data using a prepared checklist before being entered into RevMan 2011. Data included characteristics of included studies (methods, participants, interventions, outcomes) and results of the included studies. We contacted authors of included studies for unpublished adverse event data, and searched manufacturers' websites for further details of adverse events. We recorded all‐cause SAEs (fatal and non‐fatal) and in view of the difficulty in deciding whether events were asthma related, we noted details of the cause of death and SAEs where they were available.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both authors assessed the included studies for bias protection (including sequence generation for randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and assessors, loss to follow‐up, completeness of outcome assessment and other possible bias prevention) as either high, low or unclear risk of bias in line with recommendation in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We resolved disagreements by consensus. We contacted study authors and sponsors to seek clarification where bias protection was unclear.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored heterogeneity on the basis of the subgroup and sensitivity analyses outlined below.

Assessment of reporting biases

We inspected funnel plots to assess publication bias.

Data synthesis

The outcomes of this review were dichotomous, and we recorded the number of participants with each outcome event, by allocated treated group. We planned to conduct the primary analysis, mortality, using risk difference, as many studies did not have any deaths in either arm. However, revisions to the Handbook (Higgins 2008) since the protocol was written advise against this approach. Therefore, the risk differences were only used to estimate the absolute impact of treatment. The Peto odds ratio has advantages when events are rare as no continuity correction for zero cells is required, and although it can perform less well with unbalanced treatment arms and large effect sizes, the updated review has now used Peto odds ratio for all primary analyses, and the Mantel‐Haenszel random effects model has been used for sensitivity analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses on the basis of dose of salmeterol (usual dose versus high dose), age (adults versus children), severity of asthma, reported corticosteroid use at baseline, comparator used and ethnic groups. We compared subgroups using tests for interaction (Altman 2003).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The initial search in October 2007 found 512 abstracts, which we reduced to 504 after removing duplicates. Of these, we identified 154 abstracts that related to salmeterol alone (three were from references listed in identified trials and review articles, and one was only published on the GSK website). We included 32 studies in the review (42 references) and excluded 118: 71 were less than 12 weeks in duration (including 26 single‐dose studies); eight were not RCTs; five were dose comparison studies; five are ongoing studies; four were on exercise‐induced bronchospasm; four compared with theophylline; three were propellant studies; three were cross‐over in design; and seven were for other reasons. We reached consensus on all the included studies after inspection of the full text from papers and websites; there was initial disagreement on six abstracts, five of which we subsequently included and one excluded. We identified additional references to the included studies and one unpublished study from other reviews (SLGA 3014).

A further search in July 2008 generated 48 new references, of which two were relevant to this review (Inoue 2007; Pascoe 2006), but we excluded both as they were short‐term crossover studies. We identified no further new studies by the latest searches in August 2009 (79 references) or August 2011 (191 references).

Included studies

There were 32 included studies which randomised 62,630 participants (Adinoff 1998; Boulet 1997; Boyd 1995; Britton 1992; Busse 1998; Chervinsky 1999; D'Alonzo 1994; D'Urzo 2001; Kavuru 2000; Kemp 1998a; Kemp 1998b; Lazarus 2001; Lenney 1995a; Lenney 1995b; Lundback 1993; Nathan 1999; Nathan 2006; Pearlman 1992; Pearlman 2004; Rosenthal 1999; Russell 1995; Shapiro 2000; Simons 1997; SLGA 3014; SLMF4002; SMART 2006; SNS 1993; Von Berg 1998; Wenzel 1998; Weinstein 1998; Wolfe 2000).

A total of 46,501 (74%) people completed treatment, encompassing more than 19,000 patient years studied. There were only seven studies on 2380 (Lenney 1995a; Lenney 1995b;Simons 1997; SLGA 3014; Von Berg 1998; Weinstein 1998) who completed a total of 921 patient years of treatment (this is not allowing for the nine‐month extension to the two Lenney studies). The remaining studies were in adults and adolescents with most studies randomising participants of 12 years and older; however many studies included few adolescent patients (for example 6% of all participants in SNS 1993).

Twenty‐six studies (34,781 participants) compared salmeterol to placebo and eight studies (28,532 participants) compared salmeterol to regular salbutamol. Two studies included both a placebo and a salmeterol arm (Pearlman 1992; SLGA 3014). The dose of salbutamol as a comparator varied between trials: four studies used salbutamol 200 µg four times daily (Boulet 1997; Pearlman 1992; SLGA 3014; SNS 1993); one study used the same regimen for the first three months, then 200 µg twice daily for the remaining nine months (Britton 1992); two studies used 200 µg twice daily (Lenney 1995a; Lenney 1995b); and one study used 400 µg of salbutamol delivered by diskhaler four times daily for the first three months and then twice daily for the following nine months (Lundback 1993).

The duration of trials ranged from 12 to 52 weeks, but in some of the 52‐week studies the data collection was separated into two periods. Four trials separated the first three months from the subsequent nine months of follow‐up (Britton 1992; Lenney 1995a; Lenney 1995b; Lundback 1993), whilst Von Berg 1998 separated data from the first and second six‐month periods.

The dose of salmeterol used was 50 µg twice daily (described as 42 µg delivered dose in the studies from the USA) in all studies except two which used 100 µg twice daily in participants with more severe asthma on high doses of inhaled steroids at study entry (Boyd 1995; SLMF4002). Three trials used either 25 µg or 50 µg twice daily in children (Lenney 1995a; Lenney 1995b; SLGA 3014).

Concurrent use of inhaled corticosteroids varied in the included studies from zero to 100%; Table 3 lists the inhaled steroid use by study. Only Rosenthal 1999 and Simons 1997 excluded patients who were using inhaled corticosteroids at baseline. Six trials withdrew inhaled corticosteroids from participants for the duration of the trial (Kavuru 2000; Lazarus 2001; Nathan 1999; Nathan 2006; Pearlman 2004; Shapiro 2000).

1. Baseline use of inhaled corticosteroids.

| Study ID | % patients |

| Adinoff 1998 | 64 |

| Boulet 1997 | 74 |

| Boyd 1995 | 100 |

| Britton 1992 | 64 |

| Busse 1998 | 67 |

| Chervinsky 1999 | 51 |

| D'Alonso 1994 | 21 |

| D'Urso 2001 | 93 |

| Kavuru 2000 | 26 ‐ Withdrawn |

| Kemp 1998a | 43 |

| Kemp 1998b | 100 |

| Lazarus 2001 | 53 ‐ Withdrawn |

| Lenney 1995 | 57 |

| Lundback 1993 | 31 |

| Nathan 1999 | 57 ‐ Withdrawn |

| Nathan 2006 | 100 ‐ Withdrawn |

| Pearlman 1992 | 25 |

| Pearlman 2004 | 37 ‐ Withdrawn |

| Rosenthal 1999 | 0 |

| Russell 1995 | 100 |

| Shapiro 2000 | 100 ‐ Withdrawn |

| Simons 1997 | 0 |

| SLGA3014 | 50 |

| SLMF4002 | 100 |

| SMART 2006 | 47 |

| SNS 1993 | 69 |

| Von Berg 1998 | 52 |

| Weinstein 1998 | 57 |

| Wenzel 1998 | 47 |

| Wolfe 2000 | 33 |

Risk of bias in included studies

All studies were double‐blind and unlikely to have been subject to selection bias; however lack of comprehensive reporting of fatal and non‐fatal SAEs make selective reporting a threat to the validity of this review (see Figure 3). It should however be noted that the missing data are from smaller studies, so 96% of patients in the trials had some information on SAEs.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

There was very sparse information in the reports of the studies in journals or on the company website in terms of sequence generation and allocation concealment. Most of these studies were supported by GSK, and correspondence with the company indicated a high level of bias protection in sequence generation and allocation concealment for the studies that they sponsor, so it is unlikely that this area is a major concern.

Blinding

All included studies employed a double‐blind design.

Selective reporting

SAEs were not well reported in the journal publications, but were available from the controlled trial register on the GSK website for many of the included studies. The only trial that did not receive financial support from the manufacturers of salmeterol (GSK) was Lazarus 2001; the authors of this trial report have provided data on mortality and hospital admissions.

One study was unpublished (SLMF4002), but event information was available from the controlled trial register on the company website. A second unpublished trial had available data from FDA submission documents (SLGA 3014). The GSK trial register also included reports on the following studies Britton 1992 (SLGT02), D'Urzo 2001 (SLGQ94 [521/180]), Kavuru 2000 (SFCA 3002), Lenney 1995a (SLPT01/SMS40093), Lenney 1995b (SLPT02), Lenney 1995c, Nathan 2006 (SAS3004), Pearlman 2004 (SAS3003), Russell 1995 (SALMP/AH91/D89), Shapiro 2000 (SFCA 3003), SMART 2006 (SGLA5011), SNS 1993 (SNS‐D920619), Von Berg 1998 (SLGB3019[SLPT09]), Wolfe 2000 (SLGA3010 & SLGA3011).

Journal publications tend not to list mortality and all SAEs (often restricting reporting to frequent adverse events or those thought to be related to study medication). We could find no SAE data for six trials (Adinoff 1998; Boulet 1997; Chervinsky 1999; D'Alonzo 1994; Kemp 1998a; Pearlman 1992). These accounted for around 2,766 randomised patients, which represents 4% of the total randomised population. We have sought further information from GSK in relation to Adinoff 1998, Boulet 1997, Boyd 1995, Busse 1998, Chervinsky 1999, D'Alonzo 1994, Kemp 1998a, Kemp 1998b, Lenney 1995b (in relation to data from the final nine months), Lundback 1993 (in relation to data from the final nine months), Nathan 1999, Pearlman 1992, Rosenthal 1999, SNS 1993 (in relation to patients with any SAE), Weinstein 1998, and Wenzel 1998.

Although the trial identifiers have been confirmed for these studies, many do not have reports on the manufacturers trial website. At this time it has not been possible to obtain information on SAE numbers with the exception of Lenney 1995b (in relation to SAE data from the final nine months), but further information may be available later and can be included when the review is updated.

Other potential sources of bias

Only the two large surveillance studies SMART 2006 and SNS 1993 used independent outcome assessors. For this reason, the primary outcomes for this review are all‐cause mortality and SAEs, as these avoid subjective judgements on causation. SAEs thought to be related to the study medication are likely to be subject to bias and have not been included in this review.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Events were sparse in the trials and the presence or absence of a mortality was not always reported in the paper publications.

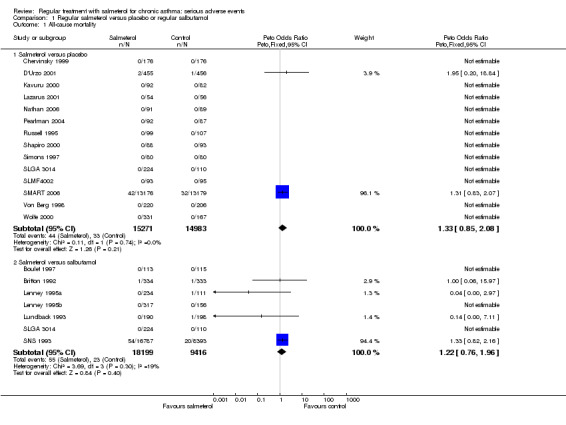

Salmeterol versus placebo

Data were available from the controlled trial register on the GSK website for 14 studies comparing salmeterol (N = 15,271) with placebo (N = 14,983); this represents 86% of the randomised patients for this comparison. Deaths only occurred in two of these trials in adults (D'Urzo 2001; SMART 2006), and overall there were 44 deaths on salmeterol and 33 on placebo. The pooled Peto OR was not statistically significant (1.33, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.08), Analysis 1.1 (see Figure 4). The confidence interval is almost identical using a Mantel‐Haenszel OR (1.33, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.10), and is the same for fixed‐effect and random‐effects models. The pooled risk difference has a point estimate of an increase of seven in 10,000, with a CI from five fewer deaths to 20 more deaths per 10,000 treated with salmeterol. There was no statistical heterogeneity in this outcome.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All‐cause Mortality, outcome: 1.1 Overall results.

Salmeterol versus salbutamol

Data were available from seven studies comparing salmeterol (N = 18,199) to salbutamol (N = 9,416), representing 93% of the randomised patients for this comparison. The larger numbers in the salmeterol arm are due to SNS 1993, in which twice as many patients were randomised to salmeterol in comparison to salbutamol. Three studies in adults (Britton 1992; Lundback 1993; SNS 1993) and one study in children (Lenney 1995a) contributed data to the outcome, although almost all the events came from the SNS study. The results were similar to those from the placebo comparison: 55 deaths occurred in the salmeterol arm compared to 23 in the salbutamol arm but again the difference was not statistically significant (Peto OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.96; Analysis 1.1; see Figure 4). The Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio was very similar (1.23, 95% CI 0.75 to 2.02). The pooled risk difference was an increase of seven in 10,000, with a CI from six fewer deaths to 20 more deaths per 10,000 treated with salmeterol. There was some heterogeneity in this outcome (I2 = 19%) but sensitivity analysis using a fixed effect risk difference gave a very similar result, with a point estimate of six per 10,000 and a CI from eight fewer deaths to 19 more deaths per 10,000 treated with salmeterol.

Subgroup analyses

No subgroup analyses were possible for all‐cause mortality as the data were too sparse, and subgroup characteristics were not reported for this outcome.

SAEs (non‐fatal all cause)

An illustrative example of the definition of SAEs used in trials by GSK is shown in Appendix 4. Whilst the majority of SAEs result in hospitalisations, the number of patients with SAEs tends to be higher than the number who are admitted to hospital (see Analysis 1.22 for comparative data from SMART 2006). We have used information on patients with any SAE for these analyses (with the exception of SNS 1993 where this was not reported, so we have used hospital admissions and life‐threatening events).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 22 All‐cause hospitalisation compared to SAE.

Salmeterol versus placebo

Combined data from adults and children

Data were available on non‐fatal SAEs from the GSK trial register and FDA submissions for 18 studies comparing salmeterol (N = 15,895) to placebo (N = 15,634); this represents 91% of the randomised patients for this comparison. The studies were largely on adults, but some data from 1333 children in five trials (Russell 1995; Simons 1997; SLGA 3014; Von Berg 1998; Weinstein 1998) contributed to the analysis. The overall result indicated an increased risk of SAEs with salmeterol (Peto OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.29) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 0), Figure 5. Random‐effects Mantel‐Haenzel modelling gave a very similar result (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.28) and the CI was unchanged when Boyd 1995 was excluded in view of the higher dose of salmeterol (100 mcg bd) used in this trial.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, outcome: 1.2 Non‐fatal serious adverse events (adults and children).

Since SAEs were rare in the studies (overall 3.6% of patients on placebo), the risk difference is small at 0.005 (95% CI 0.001 to 0.008); using the placebo arm of SMART 2006 for reference over a 28‐week period there would need to be 188 patients treated (95% CI 95 to 2606) for one extra SAE to occur, calculated by Visual Rx using the odds ratio and baseline risk of 3.6%. This is illustrated in Figure 6, which shows that for every thousand patients treated with salmeterol there are an extra five patients who will suffer a SAE, so that in comparison to 40 per thousand in the placebo group this rises to 45 per thousand on salmeterol.

6.

Serious adverse events with salmeterol in comparison to placebo. For 1000 patients given regular salmeterol for 28 weeks there would be 45 patients who suffer a serious adverse event, in comparison with 40 if all 1000 were given placebo.

Adults with non‐fatal SAEs

When the adult data comparing salmeterol with placebo were considered alone, the results showed a similar increase in risk which is also statistically significant (Peto OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.28; Figure 7). The result was unchanged using Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect, but became borderline significant using random‐effects (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.28).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, outcome: 1.3 Non‐fatal serious adverse events in adults.

Children with non‐fatal SAEs

There were only 1333 children reported for this outcome so, although the direction of effect was the same as for the adults, the CI is wide (Peto OR 1.30, 0.82 to 2.85; Figure 8). The results in children include both the possibility of a greater risk than in adults, but also the possibility of no difference between salmeterol and placebo.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, outcome: 1.4 Non‐fatal serious adverse events in children.

Salmeterol versus salbutamol

Combined data from adults and children

In contrast, the results from eight studies comparing salmeterol (N = 18,481) to salbutamol (N = 9,702), representing 98% of the randomised patients for this comparison, showed a reduction in the risk of SAEs with salmeterol which was not statistically significant (Peto OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.14). A test for interaction between the results comparing salmeterol with placebo and salbutamol was not significant. As it has not proved possible to obtain missing information in relation to the number of patients with any SAEs in SNS 1993, we used the number of hospitalisations or life/threatening events reported in the trial for the main analysis. We adopted this approach because the data collection form allowed more than one classification of events, and in contrast to the other studies in the review, the number of SAEs that did not result in hospitalisation was greater than in the hospitalisation category. We carried out a sensitivity analysis combining all non‐fatal SAEs (although this carries a risk that patients may have been more than once, which would lead to an over precise estimate) and this is shown in Analysis 1.5. This approach made very little difference to the pooled result (Peto OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.11).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 5 Non‐fatal adverse events in adults and children (SNS sensitivity analysis).

Adults with non‐fatal SAEs

The results in adults do not differ from the overall result described above (Peto OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.11).

Children with non‐fatal SAEs

Again the number of children contributing to this outcome is very small, which makes the uncertainty around the results considerable. As with the previous comparison between salmeterol and placebo, it remains possible that the risk may be higher or lower in children than in adults.

We carried out a sensitivity analysis because separate results are reported from Lenney 1995a and Lenney 1995b for the first three months and the subsequent nine months of the trial. Since patients could have contributed adverse event data from both periods of these trials, we did not consider it safe to combine the results, and full 12‐month data were not available. Both pooled results are shown in Figure 8, and there is no significant difference shown in either period. For the first three months the pooled Peto OR was 1.37 (95% CI 0.71 to 2.64) and for the nine‐month follow‐up the pooled Peto OR was 1.17 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.94).

All‐cause SAEs (fatal and non‐fatal combined)

When fatal and non‐fatal SAEs are considered together the findings are very similar to those for the non‐fatal events (Analysis 1.6), with a significant increase in risk with regular salmeterol in comparison with placebo (Peto OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.30), but not in comparison with regular salbutamol.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 6 Fatal and non‐fatal serious adverse events in adults and children.

Secondary outcomes

Mortality by cause of death

Asthma‐related mortality

The cause of death was only independently assessed in the two large surveillance studies (SMART 2006; SNS 1993). The results for asthma mortality in these studies are in Analysis 1.7; both studies found a similar increase in asthma mortality, but in the earlier SNS 1993 study this three‐fold increase in the risk of asthma death was not statistically significant, whilst in SMART 2006 a significant four‐fold increase in the risk of asthma death was found. In absolute terms the size of the risk difference for asthma mortality in SMART 2006 was very similar to that found for mortality of any cause; the point estimate for asthma related death being an increase of eight asthma deaths for every 10,000 patients treated with salmeterol for six months, with a CI from two more deaths to 14 more deaths per 10,000.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 7 Asthma mortality.

The direction and size of the increase in asthma mortality is consistent between the two studies, and although there are differences in study design and the comparator used, if the results of the two studies are combined there is a significant increase in asthma mortality with regular salmeterol, (Peto OR 2.94, 95% CI 1.41 to 6.14).

Inhaled corticosteroid use in relation to asthma mortality

We were able to obtain unpublished data from GSK in relation to asthma mortality and the use of corticosteroids at baseline for each of the asthma‐related deaths in SNS 1993. This is shown together with similar published data from SMART 2006 in Analysis 1.8. In the subgroup of patients not taking inhaled corticosteroids at baseline the combined increase in asthma mortality is statistically significant (Peto OR 6.43, 95% CI 2.13 to 19.42). This indicates a clear increase in risk of asthma death when inhaled corticosteroids were not used when the two studies are considered together.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 8 Asthma mortality (within study subgroups by ICS use at baseline).

For the subgroup taking inhaled corticosteroids at baseline, the increase in asthma mortality is smaller and not statistically significant (Peto OR 1.49, 95% CI 0.54 to 4.11). The test for interaction between inhaled corticosteroid use and asthma related deaths shows a relative OR of 0.23 (95% CI 0.05 to 1.04) and the CI includes the possibility of a 95% relative reduction in the risk of asthma death, but also a 4% relative increase in those on baseline inhaled corticosteroids. Moreover it should be pointed out that the CI for those on inhaled corticosteroids at baseline includes the overall three‐fold increase in mortality, so this finding cannot be interpreted as meaning that corticosteroids abolish any increased risk of asthma mortality from regular salmeterol.

Any corticosteroid use in relation to asthma mortality

Analysis 1.9 where the results of SMART 2006 & SNS 1993 are subgrouped according to any corticosteroid use, shows very similar results to Analysis 1.8. Whilst larger effects are shown in those not taking any form of steroid at baseline, the difference between subgroups is again not significant (Chi2= 1.96, df = 1, (P = 0.16)). As no details were provided in the report of SMART 2006 in relation to the number of patients taking oral corticosteroids at baseline, we assumed that the proportion is very small in comparison to those on inhaled corticosteroids. The information on baseline oral corticosteroid use in those who died has been extracted from Table 5 in the paper publication by Nelson et al.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 9 Asthma mortality (within study subgroups by any steroid at baseline).

Cardiovascular‐related mortality

This outcome was particularly difficult to assess as it was not a primary outcome for SMART 2006 or SNS 1993, so was not subject to independent data verification. Moreover it is very difficult in practice to know which deaths should be included in this category. The only child who died in all the identified studies was in Lenney 1995a; the death is listed both under asthma attack and circulatory arrest. The pooled odds ratio was not statistically significant and small numbers of deaths and classification problems mean that there is wide uncertainty around the finding, see Analysis 1.10.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 10 Cardiovascular mortality.

Asthma‐related SAEs

The reporting of disease‐specific SAEs on the GSK controlled trial register does not indicate how many patients suffered from more than one event. This represents a risk of over‐counting the number of patients suffering an asthma‐related SAE in the large studies, so we only included data for this outcome from studies which show individual events on the controlled‐trial web reports. The events in these studies are shown in Analysis 1.11. When salmeterol is compared to placebo the increase in asthma‐related SAEs is significant using Peto OR 1.59 (95% CI 1.05 to 2.41) but is not statistically significant using Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects OR 1.48 (95% CI 0.97 to 2.27). In comparison with salbutamol the decrease in asthma‐related SAEs is not statistically significant (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.81).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 11 Adults and Children non‐fatal asthma‐related serious adverse events.

SAEs in the cardiovascular system

The reports of SAEs in the cardiovascular system suffer from the same difficulty of possible over counting of patients with events. However, in this case there are almost no data except from SMART 2006 and SNS 1993 so the reported events in these studies have been used and are shown in Analysis 1.12. No significant differences are shown comparing salmeterol to placebo or salbutamol.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 12 Adults and children non‐fatal cardiovascular serious adverse events.

Within study subgroup analyses

D'Urzo 2001 reported the number of patients with severe asthma exacerbations (defined as hospitalisation, emergency department visit or use of oral prednisolone) in patients treated in primary care. They subgrouped according to the reported inhaled or oral corticosteroid consumption, and we found significant heterogeneity between subgroups. The direction of effect in the moderate dose subgroup was in favour of salmeterol (Peto OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.08). However in participants on oral corticosteroids or an inhaled daily dose of more than 1000 µg, the direction of effect reversed in favour of placebo (OR 1.75, 95% CI 0.99 to 3.11; Analysis 1.13). The Chi2 test for differences among the three subgroups returned P = 0.04, in keeping with the results of logistic regression analysis reported in the paper (P = 0.038). Very similar results were seen when the patients were stratified according to predicted peak flow (Analysis 1.14).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 13 Proportion of participants with serious asthma exacerbations in relation to dose of ICS.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 14 Proportion of participants with serious asthma exacerbations in relation to baseline PEF (% predicted).

SMART 2006 reported on numerous post‐hoc subgroups in relation to the primary outcome of the study (respiratory related deaths or life threatening events). The main results are shown in Analysis 1.15 to Analysis 1.21. Of these, the only comparison that had a statistically significant test for interaction was the post hoc comparison between African Americans and Causcasians (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 5.50, df = 1 (P = 0.02); Analysis 1.16). Whilst it may be tempting to interpret the individual subgroup results according to their statistical significance (such as for the subgroup with PEF less than 60% predicted as shown in Analysis 1.20), this approach is not the correct way to test for interaction between PEF and salmeterol (Altman 2003); the test for interaction between subgroups does not indicate a significant difference between those with high and low % predicted PEF (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 1.97, df = 1 (P = 0.16)).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 15 Respiratory related deaths or life‐threatening events (SMART).

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 21 Respiratory related deaths or life‐threatening events (SMART subgrouped by study phase.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 16 Respiratory related deaths or life‐threatening events (SMART subgrouped by race).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 20 Respiratory related deaths or life‐threatening events (SMART subgrouped by baseline predicted PEF).

Discussion

Summary of main results

The difference in the risk of all‐cause mortality with regular salmeterol when compared with placebo does not reach statistical significance. Non‐fatal SAEs were significantly increased in comparison with placebo. These events were uncommon, such that in the largest study (SMART 2006) 3.6% of the placebo group suffered a SAE over 28 weeks; in comparison in the salmeterol arm of the trial 4.0% reported a SAE. One additional SAE was found to occur for every 188 people treated with regular salmeterol over 28 weeks, and the play of chance is compatible with one extra event for every 100 to nearly 3000 given regular salmeterol. This increase is largely derived from the studies in adults, and as the number of children studied is small there are insufficient data to ascertain how the effect in children compares to that found in adults.

We found no significant differences for all‐cause mortality or non‐fatal SAEs in trials comparing regular salmeterol with salbutamol.

Disease‐specific mortality was not easy to assess, but we found no significant differences in cardiovascular deaths. In contrast there was a consistent increase is asthma‐related mortality in both SMART 2006 and SNS 1993. The four‐fold increase in SMART 2006 was statistically significant whilst the three‐fold increase in SNS 1993 was not. The absolute increase in asthma‐related mortality in SMART 2006 was very similar to the size of the absolute increase in all‐cause mortality; the increase represents eight extra asthma deaths for every 10,000 patients treated for six months.

The combined results of SMART 2006 and SNS 1993 showed a significant in increase asthma mortality. This increase was most apparent in patients who did not take inhaled corticosteroids at baseline, but in patients who took inhaled corticosteroids at baseline the wide confidence interval failed to rule out the possibility of a three fold increase in asthma mortality.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Although a very large number of adults given salmeterol were included in these studies, the rarity of mortality and SAEs means that there is still considerable uncertainty in relation to the size of the effects being investigated. This is a particular problem in children, where the numbers are smaller. There is insufficient evidence to be sure how the results in adults compare with those in children. It has proved difficult for the sponsor of these studies (GSK) to confirm data for some of the studies we identified, since they do not appear on their web‐based trial results register, and no data pertaining to adverse events were available for six of the included studies. The missing data are unlikely to alter the direction of the effects seen in this review, but could alter the point estimates and confidence intervals.

It is interesting to note that if this review had relied upon the information on SAEs published in papers, the results would have looked quite different (see Analysis 1.23). The published information does not indicate any significant increase in SAEs when regular salmeterol is compared to placebo in the 2117 patients included in this small subset of the included studies (Peto OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.95). If the analysis had been confined to SAEs that were thought to be drug related, the small number of events would not have provided sufficient information to draw any conclusions (Analysis 1.28).

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 23 Adults and children published non‐fatal serious adverse events.

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 28 Adults and children serious drug‐related adverse events.

Similar differences can be seen between published (Analysis 1.26) and complete data for adverse events (Analysis 1.25). The published drug related adverse events are shown in Analysis 1.27.

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 26 Adults and children published adverse events.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 25 Adults and children all adverse events.

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 27 Adults and children all published drug‐related adverse events.

Quality of the evidence

All of the included studies were double blind, and are likely to have had adequate allocation concealment. However, only the two large surveillance studies had independent assessment of the cause of death. This should not be a threat to all‐cause mortality and all‐cause SAEs (primary outcomes). In contrast the ascertainment of disease‐specific outcomes may have been subject to bias, and the data were difficult to use as they were presented as numbers of events rather than number of patients who suffered an event.

Almost all of the studies included in this review were sponsored or supported by GSK, and the lack of published data from some of the studies is of concern.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings of this review are in agreement with the findings of Salpeter 2006, who reviewed the trial evidence in relation to asthma exacerbations leading to hospital admissions, life‐threatening events or death. However the Salpeter review combined studies on salmeterol and formoterol, and only considered placebo controlled studies. Our findings also match those presented to the FDA summarising the results of salmeterol trials carried out in the USA (FDA GSK USA Studies). The submission reported: "....analysis shows similar results for hospitalizations due to asthma for subjects receiving ICS compared with salmeterol plus ICS. For subjects not receiving concomitant ICS, there were a higher number of events in salmeterol recipients compared with placebo." The same submission also found a higher incidence of respiratory related SAEs in the salmeterol group compared to placebo and this is shown alongside our results in Analysis 1.29.

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular salmeterol versus placebo or regular salbutamol, Outcome 29 Adults and children non‐fatal asthma‐related serious adverse events (FDA data shown).

The impact of inhaled corticosteroids on adverse events in relation to long‐acting beta2‐agonists

We compared data provided by GSK in relation to the inhaled corticosteroid status of those patients who died from asthma in SNS 1993 to the findings of SMART 2006. Both studies showed a similar pattern, in that the main increase in asthma‐related mortality occurred in the subgroup of patients who were not on corticosteroids when they were recruited to the study Figure 12.

It is not possible to draw firm conclusions about the risks of salmeterol when used in conjunction with inhaled corticosteroids (Martinez 2006), as the patients in this review were not randomised to inhaled corticosteroid treatment and the test for interaction between the use of inhaled corticosteroids and salmeterol was not significant. We cannot therefore conclude that inhaled corticosteroids abolish the increased risk of asthma mortality in patients taking salmeterol, nor can we assume that mortality rates might not be even lower if inhaled corticosteroids were taken alone. Moreover, the findings of D'Urzo 2001 do not show consistency in the risk of severe asthma exacerbations with salmeterol and inhaled corticosteroids in primary care; beneficial effects of regular salmeterol with moderate doses of inhaled corticosteroids contrast with increased exacerbations in patients on high doses or maintenance oral corticosteroids. Whilst the interactions between inhaled corticosteroids and beta2‐agonists are complex, corticosteroids do not appear to prevent the development of tolerance during chronic beta2‐agonist treatment (Hancox 2006b).

The results of Lazarus 2001 provide support for the fact that salmeterol cannot be used to replace inhaled corticosteroids, because although there were no hospitalisations or deaths in the study, replacing triamcinolone with salmeterol did not maintain asthma control; there was a significant increase in exacerbations on salmeterol or placebo in comparison to triamcinolone. Compliance with inhaled corticosteroids is often poor as demonstrated in Sovani 2008, and there is a risk that patients who are using salmeterol and an inhaled steroid in separate inhalers may default on the latter without immediate deterioration in their asthma symptoms.

For patients whose asthma is not well‐controlled on moderate doses of inhaled corticosteroids, additional salmeterol can give symptomatic benefit, but this may be at the expense of an increased risk of SAEs and asthma‐related mortality, risks which are not clearly abolished by inhaled corticosteroids. Therefore, the risks as well as the benefits of regular salmeterol should be discussed with patients; the drug should be discontinued if no symptomatic benefit is achieved and the manufacturers' advice not to increase the dose of salmeterol during exacerbations should be made clear. Salmeterol should not be used as a substitute for inhaled corticosteroids, and adherence with inhaled steroids should be kept under review if separate inhalers are used. Combining the medications in a single inhaler prevents patients taking salmeterol alone. Observational data from Delea 2008 indicated use of salmeterol and fluticasone in a single inhaler resulted in higher use of inhaled corticosteroids in comparison to patients prescribed two separate inhalers.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In comparison with placebo, we have found an increased risk of serious adverse events with regular salmeterol. There is also a clear increase in risk of asthma‐related mortality in patients not using inhaled corticosteroids in the two large surveillance studies. Although the increase in asthma‐related mortality was smaller in patients taking inhaled corticosteroids at baseline, the CI is wide, so it cannot be concluded that inhaled corticosteroids abolish the risks of regular salmeterol. The adverse effects of regular salmeterol in children remain uncertain due to the small number of children studied.

Implications for research.

Data on SAEs should be more fully reported in medical journals. In view of the increasing use of salmeterol in combination with inhaled corticosteroids, further studies investigating the impact of salmeterol alone on SAEs in adults may not be feasible, but studies using a combination of salmeterol and inhaled steroids should collect and fully report data on fatal and non‐fatal SAEs. The evidence base for assessing the risks and benefits of salmeterol in children is currently weak.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 April 2013 | Amended | NIHR acknowledgement inserted |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2007 Review first published: Issue 3, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 August 2011 | New search has been performed | New search in August 2011 but no new included studies. Minor edits made and plain language summary rewritten. |

| 24 August 2009 | New search has been performed | New search in August 2009 but no new studies found. New Summary of Findings tables added to show separate results for adults and children. Russell 1995 was previously wrongly classified as an adult study and this has now been corrected. The total number of participants in the review has been altered to reflect those who were randomised to one of the treatment arms included in this review. There is no change in the conclusions of the review. |

| 20 December 2008 | Amended | Primary analysis changed to Peto Odds Ratio. Typographic errors in the number of trials and participants contributing to the mortality and non‐fatal serious adverse events have been corrected to match the results in Figures 5 and 7. The results are unchanged. NIHR Programme Grant Support has been acknowledged as external funding. |

| 2 July 2008 | New search has been performed | A new search was carried out on July 1st 2008 but no new studies have been included. Additional figures have been added comparing the results of published adverse events and the complete data set available to us at present. This is included in an updated discussion section. The risk of bias tables have also been amended to reflect all the data available for serious adverse events in each study (previously the risk of selective reporting was classified according to the paper publications). The ongoing GSK study has now been excluded as it is a single dose study. An error in the data entry for SNS in Figure 7 has been corrected. No changes have been made to the conclusions of the review. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Toby Lasserson, Susan Hansen and Elizabeth Stovold of the Cochrane Airways Group for their assistance in searching for trials and obtaining the abstracts and full reports, and John White for editing the review. We also thank Steve Yancey and Richard Follows from GSK for their help in obtaining data, and Anne Tattersfield for helpful comments. We also thank the authors of Lazarus 2001 for providing additional information from their study.

CRG Funding Acknowledgement: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Airways Group.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Pharmacology of beta2‐agonists

Beta2‐agonists are thought to cause bronchodilation primarily through binding beta2‐adrenoceptors on airways smooth muscle (ASM), with subsequent activation of both membrane‐bound potassium channels and a signalling cascade involving enzyme activation and changes in intracellular calcium levels following a rise in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) (Barnes 1993). However, beta2‐adrenoceptors are also expressed on a wide range of cell types where beta2‐agonists may have a clinically significant effect including airway epithelium (Morrison 1993), mast cells, post capillary venules, sensory and cholinergic nerves and dendritic cells (Anderson 2006). Beta2‐agonists will also cross‐react to some extent with other beta‐adrenoceptors including beta1‐adrenoceptors on the heart.

The in vivo effect of any beta2‐agonist will depend on a number of factors relating to both the drug and the patient. The degree to which a drug binds to one receptor over another is known as selectivity, which can be defined as absolute binding ratios to different receptors in vitro, whilst functional selectivity is measured from downstream effects of drugs in different tissue types in vitro or in vivo. All of the beta2‐agonists described thus far are more beta2 selective than their predecessor isoprenaline in vitro. However, because attempts to differentiate selectivity between the newer agents are confounded by so many factors, it is difficult to draw conclusions about in vitro selectivity studies and probably best to concentrate on specific adverse side‐effects in human subjects at doses which cause the same degree of bronchoconstriction. The potency of a drug refers to the concentration that achieves half the maximal receptor activation of which that drug is capable but it is not very important clinically as for each drug, manufacturers will alter the dose to try to achieve a therapeutic ratio of desired to undesired effects. In contrast efficacy refers to the ability of a drug to activate its receptor independent of drug concentration. Drugs that fully activate a receptor are known as full agonists and those that partially activate a receptor are known as partial agonists. Efficacy also is very much dependent on the system in which it is being tested and is affected by factors including the number of receptors available and the presence of other agonists and antagonists. Therefore, whilst salmeterol acts as a partial agonist in vitro, it causes a similar degree of bronchodilation to the strong agonist formoterol in stable asthmatic patients (Van Noord 1996), presumably because there are an abundance of well‐coupled beta2‐adrenoceptors available with few downstream antagonising signals. In contrast, with repetitive dosing formoterol is significantly better than salmeterol at preventing methacholine‐induced bronchoconstriction (Palmqvist 1999). These differences have led to attempts to define the 'intrinsic efficacy' of a drug independent of tissue conditions (Hanania 2002), as shown in Table 5. The clinical significance of intrinsic efficacy remains unclear.

2. Intrinsic efficacy of beta‐agonists.

| Drug | Intrinsic efficacy (%) |

| Isoprenaline, adrenaline | 100 |

| Fenoterol | 42 |

| Formoterol | 20 |

| Salbutamol | 4.9 |

| Salmeterol | < 2 |

Adapted from Hanania 2002. The authors acknowledge that it is difficult to determine the intrinsic efficacy of salmeterol given its high lipophilicity

Appendix 2. Possible mechanisms of increased asthma mortality with beta2‐agonists

Direct toxicity

This hypothesis states that direct adverse effects of beta2‐agonists are responsible for an associated increase in mortality and most research in the area has concentrated on effects detrimental to the heart. Whilst it is often assumed that cardiac side‐effects of beta2‐agonists are due to cross‐reactivity with beta1‐adrenoceptors (i.e. poor selectivity), it is worth noting that human myocardium also contains an abundance of beta2‐adrenoceptors capable of triggering positive chronotropic and inotropic responses (Lipworth 1992). Indeed, there is good evidence that cardiovascular side effects of isoprenaline and other beta2‐agonists including salbutamol are mediated predominantly via cardiac beta2‐adrenoceptors thus making the concept of in vitro selectivity less relevant (Arnold 1985; Hall 1989). Generalised beta2‐adrenoceptor activation can also cause hypokalaemia and it has been proposed that, through these and other actions beta2‐agonists may predispose to life‐threatening dysrhythmias or cause other adverse cardiac effects (Brown 1983).