Abstract

Altered alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor signaling is associated with cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) and its cognate receptor CXCR4 have been reported to mediate cardioprotection after injury through the mobilization of stem cells into injured tissue. However, little is known regarding whether SDF-1/CXCR4 induces acute protection following pathological hypertrophy and if so, by what molecular mechanism. We have previously reported that CXCR4 physically interacts with the beta-2 adrenergic receptor and modulates its down stream signaling. Here we have shown that CXCR4 expression prevents beta-adrenergic receptor induced hypertrophy. Cardiac beta-adrenergic receptors were stimulated with the implantation of a subcutaneous osmotic pump administrating isoproterenol and CXCR4 expression was selectively abrogated in cardiomyocytes using Cre-loxP-mediated gene recombination. CXCR4 knockout mice showed worsened fractional shortening and ejection fraction. CXCR4 ablation increased susceptibility to isoproterenol-induced heart failure, by upregulating apoptotic markers and reducing mitochondrial function; cardiac function decreases while fibrosis increases. Additionally, CXCR4 expression was rescued with the use of cardiotropic Adeno-associated viral-9 (AAV9) vectors. CXCR4 gene transfer reduced cardiac apoptotic signaling, improved mitochondrial function and resulted in a recovered cardiac function. Our results represent the first evidence that SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling mediates acute cardioprotection through modulating beta-adrenergic receptor signaling in vivo.

Keywords: heart failure, cardiac remodeling, gene delivery, adeno-associated virus, chemokines

Introduction

Heart disease is not only the leading cause of death, disability, and healthcare expense in the US, but also the leading cause of death worldwide, and treatments to reduce cardiac damage could have significant health and fiscal impacts.1-3 Cardiac hypertrophy is a prevalent complication of chronic hypertension and an independent risk factor for heart failure and death.4 Current therapies assume that hypertrophy is mediated by neurohormonal activation of G-protein signaling pathways.5 Both α- and β-stimulation, operating through different mechanisms, appear to have growth-promoting effects on cardiac myocytes.6 The cardiac β-adrenergic signaling system mediates most effects of circulating catecholamines and represents the most powerful regulatory input in the heart.7,8 Sustained β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) activation was shown to enhance the synthesis of myocardial proteins. This effect was mediated via stimulation of myocardial growth factors, up-regulation of nuclear proto-oncogenes, induction of cardiac oxidative stress, as well as activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.9,10 Catecholamine-induced cardiac hypertrophy is associated with reduced contractile responses to adrenergic agonists, an effect attributed to the down regulation of myocardial β-ARs, uncoupling of the β-ARs and adenylate cyclase, in addition to modifications of downstream cAMP-mediated signaling.7,8 In compensated cardiac hypertrophy, these changes are associated with preserved or even enhanced basal ventricular systolic function due to increased sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium (Ca2+).

Recently, CXCR4 and its ligand, SDF-1α, have been considered therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease.11,12 SDF-1-CXCR4 axis was identified as a key factor in the recruitment of stem cells to areas of tissue injury in multiple organ systems. CXCR4 is a member of the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family, and agonists or antagonists of GPCRs have been used to treat diseases of every major organ system including the cardiovascular system, becoming the most successful molecular targets in clinical medicine.13,14,15 Given the keen interest in using SDF-1αas a therapeutic target, it is essential to determine the direct effects of SDF-1α on myocardial function. CXCR4 activation pathways are well studied in leukocytes, however, we cannot assume that CXCR4 functions in an identical capacity in cardiomyocytes. CXCR4 is a widely expressed chemokine receptor that is essential for development, hematopoiesis, organogenesis, and vascularization.16

We have previously reported that CXCR4 physically interacts with the β2-ARs and diminishes downstream signaling.17 Activation of CXCR4 by SDF-1α leads to a decrease in β-AR-induced PKA activity as assessed by cAMP accumulation and PKA-dependent phosphorylation of phospholamban, an inhibitor of SERCA2a that regulates calcium handling. Calcium handling is known to be disrupted in heart failure, and interventions aimed at improving cell calcium cycling may represent a promising approach to heart failure therapy.18 Utilizing the transverse aortic constriction (TAC) model in mice to induce hypertrophy and heart failure, we recently reported that overexpression of CXCR4 by gene transfer successfully prevented cardiac remodeling during chronic pressure overload.19 Cardiac overexpression of CXCR4 in mice with pressure overload prevented ventricular remodeling, preserved capillary density and maintained function, by a mechanism that has not yet been fully understood.

Over the years, many myocardial signaling pathways have been implicated in regulating the cardiac response to increased pressure or volume load, e.g. Gα (13)-mediated activation of the small GTPase RhoA,20 gp-130-mediated activation of the JAK/STAT pathway,21 AKT-mediated activation of GSK3β downstream signaling,22 increased expression and activity of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) etc.23 Moreover, compensatory hypertrophy in patients has also been associated with the increased expression of regulatory agonists such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), endothelin (ET)-1 and angiothensin II (Ang II).24,25 The current mainstay in heart failure treatment is the use of β-AR antagonists, indicating the importance of this pathway in regulating pathological hypertrophy. We designed this study to better understand signaling pathways that are relevant to the CXCR4 anti-remodeling response.

In our model of pathological hypertrophy, we sought to elucidate the critical role of SDF-1α/CXCR4 in regulating β-AR mediated hypertrophy and associated signaling. To do so, we constructed a model in which mice were treated with isoproterenol, a β-adrenergic agonist that induces cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. CXCR4 expression was selectively abrogated in cardiomyocytes using Cre-loxP-mediated gene deletion. Moreover, CXCR4 gene expression was rescued with gene therapy using AAV9 vectors, a non-pathogenic human parvovirus that is gaining attention for its potential use as a human gene therapy vector. Cardiac gene therapy using AAV vectors has been proven to be safe and efficacious in humans (CUPID Trial).26 We explored the importance of the SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis in an isoproterenol-induced model of heart failure and tested the hypothesis that deletion of myocardial CXCR4 exacerbates cardiac dysfunction and that AAV9.CXCR4 gene transfer could rescue the heart function and alleviate the symptoms.

Results

Generation of CXCR4 cardiac-specific knockout (CXCR4-KO) mice

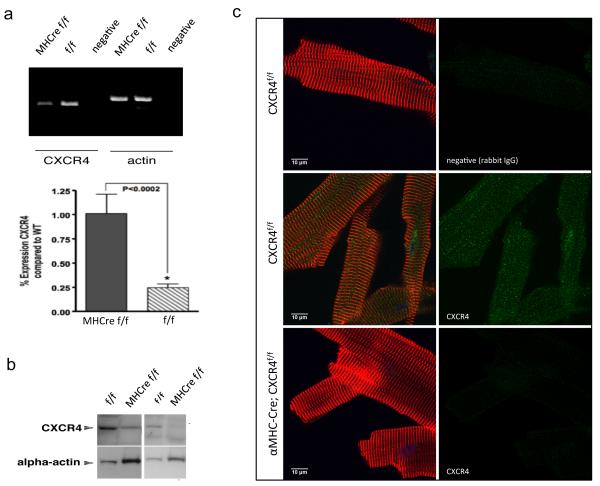

To better understand the underlying mechanisms and to uncover SDF-1α /CXCR4’s potential role in regulating β-AR mediated hypertrophic signaling, we generated CXCR4-KO mice. Cardiac specific CXCR4-KO were required because whole body deletion of either CXCR4 or SDF-1α results in an embryonic lethal mutation, leading to hematopoietic and cardiac defects.27-28 The phenotypic similarity of the SDF-1α and CXCR4 genetically deficient mice suggests that this ligand-receptor pair comprises a monogamous signaling unit in vivo. Interestingly, cardiomyocyte specific deletion of CXCR4 produces viable mice,29 which we confirmed independently in this study. Briefly, cardiomyocytes were enzymatically isolated and cells were tested for the presence of CXCR4. Quantitative real-time-PCR (qRT-PCR) using RNA isolated from these CXCR4-KO cardiomyocytes demonstrates significantly less CXCR4 RNA levels compared to wild type (Figure 1a). Western blot analysis using protein lysates from these isolated cardiomyocytes confirmed our expectations of significantly lower CXCR4 protein expression (Figure 1b). These observations were also validated by immunohistochemistry analysis revealing significant reduction in CXCR4 protein expression (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Generation of a cardiac-specific CXCR4-KO. CXCR4 flox/flox (f/f) mice, in which both CXCR4 alleles contain flox sites flanking CXCR4 exon 2, were crossed with α-MHC Cre (Cre+) mice to produce CXCR4-KO (MHCre f/f). Cardiomyocytes were enzymatically isolated and cells were tested for the presence of CXCR4. (a) CXCR4 mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR using a QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit and using specific primers for CXCR4 and α-actin. Primers were designed to generate short amplification products. Primers for α-actin served as a control for RNA loading and degradation. Densitometric analysis of data from three different experiments is shown. *P < 0.05. qRT-PCR data demonstrates significantly less CXCR4 RNA levels compared to control group (CXCR4-f/f). (b) CXCR4 protein expression was assessed in cardiomyocytes isolated from CXCR4-KO and flox control groups (n=3). Protein lysates were prepared from these isolated cardiomyocytes and analyzed by Western blot. There is a significant reduction in CXCR4 protein expression in CXCR4-KO mice when compared to the control group (CXCR4-f/f). Representative gels (left and right panels) of different animals in each group are shown here. (c) Immunohistochemistry analysis also confirmed these observations. Isolated mouse cardiomyocytes were fixed and cardiomyocyte-CXCR4 positive (Green), α-actinin-cy3 (Red) and nuclei-DAPI (blue) visualized at 100x magnification. Immunostaining of CXCR4 on the cardiomyocytes indicated proper membrane localization in the control group (CXCR4-f/f).

CXCR4 overexpression improves cardiac function in CXCR4-KO mice following isoproterenol treatment

Our study assessed whether the absence of CXCR4 worsens cardiac hypertrophy during sustained exposure to isoproterenol; an agonist of β-ARs. Knockout and wild type mice were surgically implanted with a subcutaneous osmotic pump delivering 30mg/kg/day isoproterenol. To measure cardiac performance, echocardiography was performed at baseline, 7 days and 14 days post implantation. Echocardiography is an ideal method to track heart function in treated mice over time because of its non-invasive nature. Mice were left undisturbed for an additional week to maximize the remodeling process. Hemodynamic measurements were obtained at the end of the study (three weeks post implantation) using a pressure-volume conductance catheter. In order to confirm that the observed phenotypes were the result of CXCR4 ablation, we overexpressed CXCR4 using AAV9 gene transfer to see whether it would rescue the phenotype. AAV9 constructs encoding CXCR4 along with a LacZ control were generated; titration, purity and the most efficient dose for CXCR4 overexpression in the murine heart had been previously determined.19 AAV9.CXCR4 was injected via the tail vein one month prior to pump insertion.

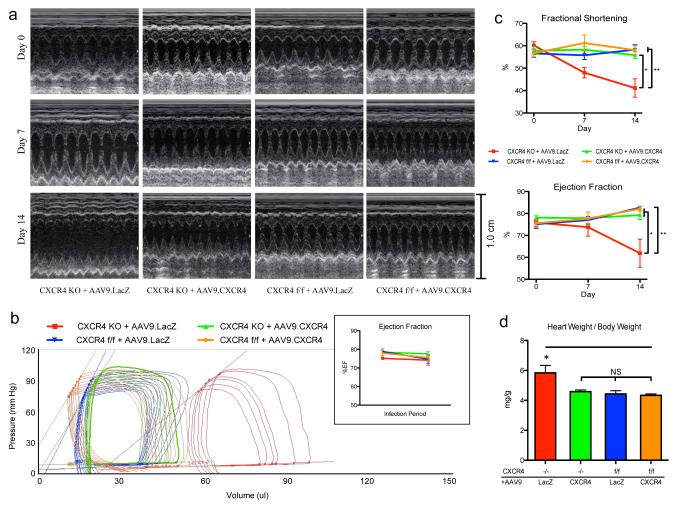

Ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), end-systolic and end-diastolic left ventricular internal dimensions (LVIDs and LVIDd), interventricular septum thickness (IVSs and IVSd), and left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPWs and LVPWd) were assessed (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). Representative images of short axis m-mode are shown (Figure 2a). At three weeks post pump insertion, in vivo hemodynamics were collected and heart weight–body weight (HW:BW) ratio was calculated (Table 2, Figures 2b-d,). Representative sets of pressure-volume loops from all treated groups were selected (Figure 2b). Our data demonstrates that CXCR4-KO mice exhibited depressed cardiac function as indicated by a reduction in EF and FS (Figure 2c), as well as increased end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes (Table 1 and 2) and greater HW:BW ratio following isoproterenol treatment (Figure 2d). CXCR4-KO mice that had been injected with AAV9.CXCR4 were rescued from cardiac dysfunction and performance was restored to control group (CXCR4-f/f) levels (Figure 2c). Specifically, CXCR4-treated mice showed reduced end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes (Figures 2a, c), and had reduced HW:BW’s compared to LacZ controls (Figure 2d). Loss of EF and FS was also prevented in knockout mice overexpressing CXCR4 (P < 0.05) (Table 2, Figure 2c).

Table 1.

30mg/kg/day Isoproterenol Pump

| Baseline | CXCR4 KO | CXCR4 flox/flox | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +AAV9.LacZ | +AAV9.CXCR4 | +AAV9.LacZ | +AAV9.CXCR4 | |

| n= | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| IVSd (mm) | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 0.79 ± 0.03 | 0.74 ± 0.01 |

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.69 ± 0.09 | 3.57 ± 0.10 | 3.52 ± 0.18 | 3.78 ± 0.22 |

| LVPWd (mm) | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.78 ± 0.04 | 0.80 ± 0.04 | 0.72 ± 0.06 |

| IVSs (mm) | 1.63 ± 0.10 | 1.65 ± 0.06 | 1.67 ± 0.05 | 1.65 ± 0.02 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.48 ± 0.09 | 1.52 ± 0.11 | 1.54 ± 0.13 | 1.65 ± 0.15 |

| LVPWs (mm) | 1.70 ± 0.05 | 1.63 ± 0.04 | 1.64 ± 0.06 | 1.60 ± 0.11 |

| %FS | 60.2 ± 1.6 | 57.8 ± 1.8 | 56.6 ± 1.8 | 56.7 ± 1.6 |

| EDV (μL) | 79.1 ± 7.0 | 74.5 ± 5.6 | 71.0 ± 5.4 | 80.5 ± 11.7 |

| ESV (μL) | 18.9 ± 1.5 | 16.5 ± 1.7 | 17.9 ± 2.2 | 19.4 ± 2.6 |

| %EF | 76.0 ± 1.6 | 78.1 ± 0.8 | 75.1 ± 1.9 | 75.6 ± 1.7 |

| HR (bpm) | 559 ± 13 | 592 ± 30 | 523 ± 38 | 557 ± 24 |

|

| ||||

| 7 Days Infusion | CXCR4 KO | CXCR4 flox/flox | ||

| +AAV9.LacZ | +AAV9.CXCR4 | +AAV9.LacZ | +AAV9.CXCR4 | |

|

| ||||

| n= | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| IVSd (mm) | 0.84 ± 0.05 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.97 ± 0.08 |

| LVIDd (mm) | 4.23 ± 0.22 | 3.87 ± 0.06 | 3.77 ± 0.15 | 3.51 ± 0.16 * |

| LVPWd (mm) | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.82 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.14 |

| IVSs (mm) | 1.68 ± 0.06 | 1.64 ± 0.06 | 1.75 ± 0.05 | 1.87 ± 0.07 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 2.21 ± 0.18 | 1.62 ± 0.08 * | 1.67 ± 0.12 * | 1.38 ± 0.19 ** |

| LVPWs (mm) | 1.62 ± 0.08 | 1.79 ± 0.07 | 1.66 ± 0.05 | 1.84 ± 0.24 |

| %FS | 48.0 ± 2.3 | 58.3 ± 1.5 * | 55.7 ± 1.9 | 61.2 ± 3.6 ** |

| EDV (μL) | 113.1 ± 12.3 | 83.6 ± 6.2 | 85.9 ± 10.8 | 94.2 ± 7.3 |

| ESV (μL) | 30.7 ± 7.2 | 19.1 ± 3.5 | 20.0 ± 3.3 | 20.9 ± 3.1 |

| %EF | 73.7 ± 4.1 | 77.9 ± 2.8 | 77.0 ± 1.7 | 77.7 ± 3.0 |

| HR (bpm) | 656 ± 31 | 607 ± 26 | 642 ± 14 | 680 ± 29 |

|

| ||||

| 14 Days Infusion | CXCR4 KO | CXCR4 flox/flox | ||

| +AAV9.LacZ | +AAV9.CXCR4 | +AAV9.LacZ | +AAV9.CXCR4 | |

|

| ||||

| n= | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| IVSd (mm) | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 0.70 ± 0.02 | 0.78 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.06 |

| LVIDd (mm) | 4.32 ± 0.28 | 3.80 ± 0.09 | 3.50 ± 0.08 * | 3.89 ± 0.14 |

| LVPWd (mm) | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.80 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.08 |

| IVSs (mm) | 1.46 ± 0.12 | 1.46 ± 0.03 | 1.56 ± 0.05 | 1.78 ± 0.11 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 2.59 ± 0.33 | 1.68 ± 0.08 * | 1.47 ± 0.09 ** | 1.63 ± 0.10 * |

| LVPWs (mm) | 1.46 ± 0.10 | 1.80 ± 0.11 | 1.73 ± 0.04 | 1.74 ± 0.18 |

| %FS | 41.2 ± 4.1 | 55.8 ± 1.6 * | 58.3 ± 2.2 ** | 58.0 ± 2.0 ** |

| EDV (μL) | 123.0 ± 12.4 | 86.5 ± 3.2 * | 84.6 ± 3.7 * | 90.0 ± 4.4 |

| ESV (μL) | 50.1 ± 13.0 | 18.1 ± 2.4 * | 14.6 ± 0.5 * | 16.0 ± 1.0 * |

| %EF | 61.9 ± 6.4 | 79.3 ± 2.0 * | 82.7 ± 0.6 ** | 82.1 ± 1.0 * |

| HR (bpm) | 677 ± 21 | 708 ± 26 | 679 ± 21 | 649 ± 21 |

One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test was performed between all groups at each time point. Asterisks indicate significance in comparison to the CXCR4 KO + AAV9.LacZ group

Figure 2.

AAV9.CXCR4 or AAV9.LacZ control was delivered to the heart via tail vein injection one month prior to pump insertion. (a) Echocardiography was performed at baseline, one week and two weeks post isoproterenol-treatment and showed significant dilation and loss of function that was prevented in gene therapy rescued animals. (b) In vivo hemodynamic data were acquired using a pressure-volume conductance catheter via an open-chest approach. Pre-load reduction studies were done by transiently occluding the inferior vena cava. CXCR4-KO-AAV9.LacZ (red) CXCR4-KO-AAV9.CXCR4 (green) CXCR4-f/f-AAV9.LacZ (blue) and CXCR4-f/f-AAV9.CXCR4 (orange) are shown at baseline and 3 weeks post isoproterenol treatment. AAV9.CXCR4 and AAV9.LacZ had no effects on cardiac function in the absence of isoproterenol treatment as demonstrated in the inset by unchanged ejection fraction prior to isoproterenol infusion. (c) Heart function (ejection fraction and fractional shortening) was significantly reduced in CXCR4-KO AAV9.LacZ group as compared to other groups. (d) Heart weight/body weight ratio. CXCR4-KO exhibited greater heart weight–body weight (HW:BW) ratio after isoproterenol treatment (n=5 mice/group).

Table 2.

In vivo hemodynamics: pressure-volume data were analyzed using 10X2 software.

| 14 Days Infusion | CXCR4 KO | CXCR4 flox/flox | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +AAV9.LacZ | +AAV9.CXCR4 | +AAV9.LacZ | +AAV9.CXCR4 | |

| n= | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Pes (mm Hg) | 96.5 ± 7.9 | 90.6 ± 5.1 | 99.6 ± 10.1 | 105.3 ± 12.9 |

| Ped (mm Hg) | 6.2 ± 1.0 | 8.6 ± 1.7 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 8.5 ± 0.5 |

| dP/dtmax (mm Hg/s) | 5780 ± 393 | 4677 ± 339 * | 5173 ± 313 | 5308 ± 1008 |

| dP/dtmin (mm Hg/s) | -4765 ± 175 | -3778 ± 340 | -4155 ± 475 | -4029 ± 840 |

| Tau (ms) | 10.3 ± 0.9 | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 11.6 ± 0.7 | 11.2 ± 0.4 |

| EDV (μL) | 86.0 ± 7.9 | 49.8 ± 3.8 ** | 50.6 ± 3.7 ** | 54.7 ± 2.5 ** |

| ESV (μL) | 51.8 ± 7.6 | 18.4 ± 2.6 ** | 21.4 ± 4.0 ** | 20.2 ± 2.2 ** |

| SV (uL) | 48.0 ± 3.9 | 38.8 ± 1.2 | 37.6 ± 1.5 * | 42.3 ± 1.3 |

| CO (μL/min) | 25021 ± 2364 | 17291 ± 1287 * | 15328 ± 907 ** | 17043 ± 1666 * |

| EF (%) | 52.0 ± 3.6 | 72.6 ± 2.4 ** | 66.8 ± 4.8 * | 70.5 ± 3.2 * |

| SW (mm Hg * μL) | 3836 ± 258 | 2938 ± 213 | 3301 ± 266 | 3843 ± 555 |

| Ea (mm Hg/μL) | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| ESPVR | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.8 |

| EDPVR | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.03 |

| PRSW | 93.9 ± 11.7 | 97.5 ± 12.9 | 94.3 ± 9.9 | 118.6 ± 22.2 |

| HR (bpm) | 499 ± 15 | 445 ± 22 | 424 ± 19 | 440 ± 23 |

Asterisks indicate significance in comparison to the CXCR4 KO + AAV9.LacZ group.

There were no significant changes in wall thickness comparing day 0 and day 14 in any of the groups. However there was a trend toward thickening after 7 days of isoproterenol treatment (Supplementary Figures S1a and b), especially in the CXCR4-flox treated control group, suggesting some initial concentric hypertrophy. These changes were reversed between week 1 and week 2, and in fact there was overall wall thinning in some animals, which was reflected in a thinner wall during systole, potentially due to apoptosis. The rescued CXCR4-KO group did not show initial hypertrophy. Eccentric hypertrophy was not seen using m-mode images in control groups. However estimates of LV volume using 2D images and the formula V=5/6*Area*Length showed an increase in end-diastolic volume among all groups following isoproterenol treatment (Table 1).

The CXCR4-KO mice treated with AAV9-LacZ clearly show significant LV remodeling and decreased contractility as evidenced by the echocardiography and PV loop data. The echocardiography data shows a 50% increase in the LV end diastolic volume and over 100% increase in the LV end systolic volume and significantly lower EF two weeks after isoproterenol infusion (Table 1). Similar results were obtained by PV loop (Table 2). Therefore, the decrease in EF could be explained by decreases in systolic function and depressed cardiac contractility. However, this is not reflected in the hemodynamic assessment of cardiac contractility such as Pes or ESPVR, dp/dt max and PRSW. Out of those parameters, the ESPVR is the most reliable parameter because it is not affected by loading conditions or afterload. Although the ESPVR in the CXCR4-KO mice was lower than the other groups, it did not reach statistical significance; however, the V0 (theoretical volume when no pressure is generated) was shifted to the right compared to the other three groups (Figure 2b, Supplementary Figures S2a and b). Together, a lower ESPVR and a rightward shift in V0 account for depressed contractility. Unfortunately, this is a limitation of the PV loop system and it is not feasible to adjust the ESPVR value for the rightward shift in V0.

Collectively, echocardiography and in vivo hemodynamics revealed maintenance of ventricular volumes and ESPVR with AAV9.CXCR4 (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 2). Taken together, these changes indicating a role for the SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis in regulating hypertrophy in response to isoproterenol, a catecholamine that activates both β-adrenergic receptor isoforms (β1-AR and β2-AR). .

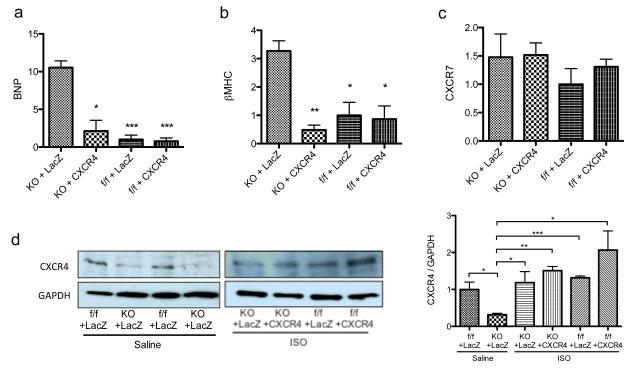

Changes in the expression of hypertrophy-related genes

The expression patterns of cardiac hypertrophy-related genes have been well documented and widely used as markers for hypertrophy. We first looked at the expression of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP). BNP is a hormone produced by the heart that is released in response to changes in pressure that occur during the development of heart failure, and as such, BNP expression level is considered to be an indicator for heart failure.30 qRT-PCR revealed a marked upregulation in BNP mRNA expression in CXCR4-KO LacZ-treated mice (Figure 3a). Overexpressing AAV9.CXCR4 inhibited BNP upregulation and levels matched those of the control groups (CXCR4-f/f). Next, We looked to the expression of β- myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) as a marker of pathological hypertrophy. It has also been reported that re-expression of β-MHC occurs in distinct regions of the hypertrophic heart.31 Next, we assessed the expression of β-MHC. As expected, cardiac β-MHC mRNA quantified by qRT-PCR was significantly increased in CXCR4-KO LacZ-treated mice. That effect was completely abolished in AAV9.CXCR4-rescued knockout animals (Figure 3b), indicating that CXCR4 overexpression improves cardiac function. These findings suggest a significant role for the SDF-1α /CXCR4 axis in regulating cardiac function in the stressed condition.

Figure 3.

Expression profiling of cardiac genes associated with hypertrophy. (a-c) RNA was isolated from whole ventricular myocardium and the expression of hypertrophy associated genes e.g. BNP, β MHC and CXCR7 were assessed. Specific mRNA levels were quantified via qRT-PCR performed in triplicate (n=3 mice/group *= p<0.05, **=p<0.01). (d) CXCR4 protein expression before and after isoproterenol infusion was quantified by western blot. Representative Western blots of CXCR4 from three animals per group are shown in the right panel (n=3). GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. Densitometric analysis of data from three different experiments is shown in the left panel. *p < 0.05, **=p<0.01, **=p<0.001.

It has been traditionally assumed that SDF-1α would affect its target cells by selectively interacting with the CXCR4, however, recent work revealed that SDF-1α also binds to the chemokine receptor CXCR7 (SDF-1α alternative receptor).32 Subsequent studies indicated that CXCR7 might have diverse functions in different cell types and biological conditions.33 To uncover whether the absence of CXCR4 alters CXCR7 expression in the heart, CXCR7 mRNA levels were assessed. Although a trend of upregulation in CXCR7 expression appears in both AAV9.LacZ and AAV9.CXCR4 treated groups, there were no statistically significant changes observed among these groups (Figure 3c), suggesting that its expression is not regulated by the presence or absence of myocardial CXCR4. Last, CXCR4 protein expression was quantified in the hearts of the experimental animals by western blot before and after isoproterenol infusion (Figure 3d). Densitometric analysis of data from three different experiments showed significant reduction in CXCR4 protein expression between CXCR4-KO and CXCR4-flox groups treated with AAV9.LacZ and implanted with a saline vehicle pump (Figure 3d, right panel). However, treatment with isoproterenol caused a marked increase in CXCR4 expression in all cohorts when compared to the saline groups. As our model only abolished CXCR4 in cardiomyocytes, this may be due to CXCR4 upregulation in other heart resident cells such as fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells in response to isoproterenol.

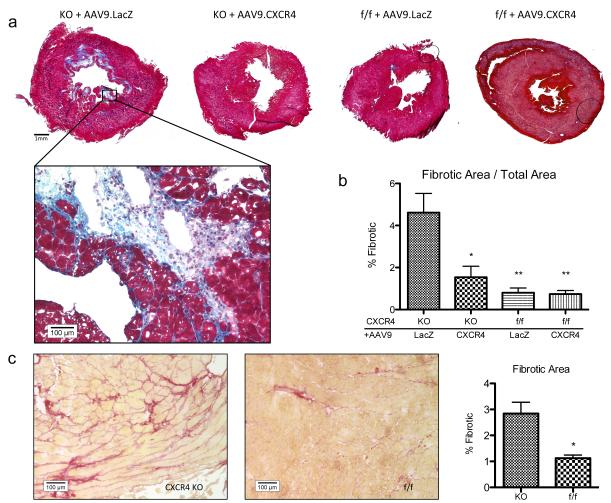

CXCR4-KO mice exhibited increased interstitial fibrosis in vivo following isoproterenol treatment

We used conventional Picrosirius Red and Masson's Trichrome staining to assess interstitial fibrosis. Histological staining was done on left ventricular sections at mid-papillary level and images were taken using light microscopy (Figure 4). Cardiac fibrosis was quantified using Masson’s Trichrome staining technique using a composite image of each sample at 40x magnification (Figure 4a). There was a significant increase in fibrosis in CXCR4-KO groups that was not present in the AAV9.CXCR4-rescued group (Figures 4a and c). CXCR4 overexpression prevented ventricular remodeling in the setting of isoproterenol-induced hypertrophy and failure (Figures 4a and b). Our data also confirms that the AAV9.LacZ overexpression does not have any side effects, as similar levels of fibrosis were observed in isoproterenol-stressed CXCR4-KO mice both with and without AAV9.LacZ gene therapy.

Figure 4.

CXCR4 knockout mice showed increased perivascular and interstitial fibrosis compared to rescued animals and controls. (a) Ventricular cross sections were taken at the midpapillary level and stained using Masson’s Trichrome. Comparative images shown are composites of images taken at 40x. Panel shown at 200X. (b) Quantification of fibrosis was calculated over the entire section at 40X magnification. The significance of each group is shown as compared to knockouts injected with AAV9.LacZ (*= p<0.05, **= p<0.01). (c) Sirius red stained sections at 200x. Quantification of fibrosis was calculated on sections obtained from CXCR4-KO and control group (CXCR4-f/f) subjected to isoproterenol treatment without any gene therapy.

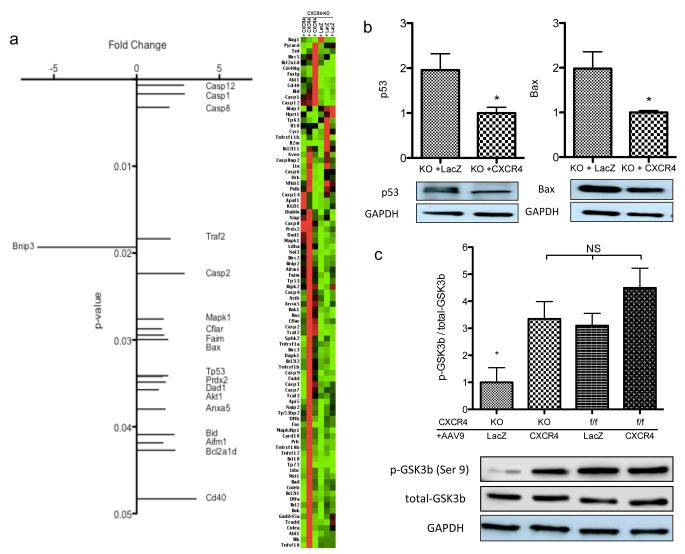

PCR array analysis of CXCR4-KO mice as compared to flox control; CXCR4 gene therapy increases GSK3β activity

Our next step was to assess the possible mechanisms that confer protection and are modulated by CXCR4. RNA was isolated from whole ventricular myocardium and specific mRNA levels were quantified. Using a commercial PCR array, we identified genes that were either upregulated or downregulated in AAV9.CXCR4-rescued mice as compared to CXCR4-KO mice post isoproterenol treatment. Interestingly, many of these genes were associated with cell death pathways (Figure 5a). Our data demonstrates significant upregulation of p53 (tumor suppressor gene) and Bax (Bcl-2-associated X protein) in the CXCR4-KO group, whereas AAV9.CXCR4-gene therapy prevented upregulation and reduced mRNA levels and their protein expression significantly (Figure 5b). p53 and Bax are both pro-apoptotic genes that can be regulated by the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) signaling pathway.34

Figure 5.

Transcriptional profile suggests upregulation of apoptotic markers. (a) RNA was isolated from whole ventricular myocardium and the expression of 84 genes were tested using qRT-PCR arrays in which fold changes (x axis) in gene expression of AAV9.CXCR4-rescued knockouts are shown compared to knockouts injected with AAV9.lacZ (n=3 per group). (b) mRNA expression of GSK3-activated pro-apoptotic factors; P53 and Bax (quantified via qRT-PCR) was shown in upper panel (n=3) and representative Western blots of P53 and Bax protein expression from four animals per group is shown in the lower panel (*= p<0.05). (c) Densitometric analysis for GSK3β phosphorylation/total-GSK3β is shown (*= p<0.05) and a representative Western blot of GSK3β phosphorylation on Ser9 is depicted. Western blots were performed on lysates prepared from whole ventricular tissue, and quantification was performed using four animals per group.

GSK3, of which there are two isoforms, GSK3α and GSK3β, was originally characterized in the context of glycogen metabolism regulation but is now known to regulate many other cellular processes including the promotion of apoptotic signaling. In neural cells, p53 forms a complex with GSK3β that in turns activates the Bax and Caspase 3 pathways.34 In the heart, emphasis has been placed particularly on the GSK3β isoform. Phosphorylation of GSK3α (Ser21) and GSK3β (Ser9) inhibits their protein kinase activity. Hypertrophic agonists such as β-AR ligands increase phosphorylation of GSK3β (Ser9), resulting in a 40–60% decrease in its activity. Immunoblot analysis (Figure 5c, lower panel) and relative quantification of p-GSK3β (Ser9) (Figure 5c, upper panel) demonstrates a significant decrease in the phosphorylation of GSK3β (Ser9) in CXCR4-KO LacZ-treated mice that were exposed to isoproterenol. This implies that there is increased GSK3β-dependent signaling activity associated with these knockouts. In mice injected with AAV9.CXCR4, phosphorylation (Ser9) was restored and GSK3β activity was diminished suggesting that the SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis utilizes this signaling pathway (Figure 5c).

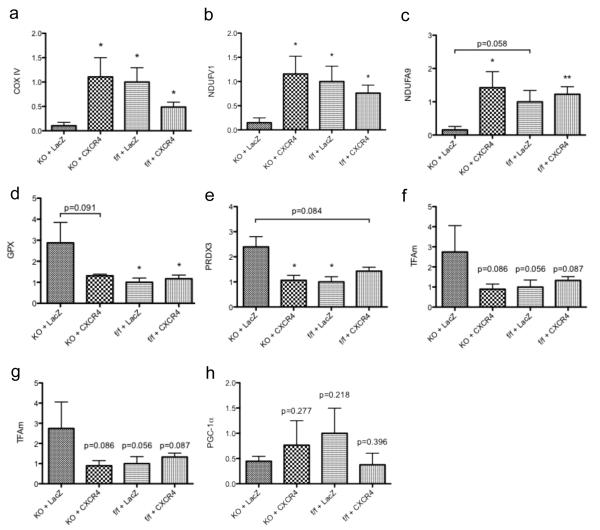

Mitochondrial-related gene expression changes

Mitochondria are the main intracellular location for fuel generation and it is generally accepted that mitochondrial dysfunction develops in the failing heart.35 The purpose of this section was to outline changes in mitochondrial function, oxidative stress and biogenesis in CXCR4-KO mice and to evaluate whether these changes were attenuated by AAV9.CXCR4 over expression. Indeed, in our model of chronic exposure to isoproterenol-induced hypertrophy, we observed significant changes in mitochondrial gene expression profiles (Figure 6). We first studied genes that are involved in regulating mitochondrial function, e.g. cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV (COX IV), NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase complex 1 (Ndufv1 and Ndufa9) ; these genes are important in the electron transport chain.36 Our data demonstrates a significant reduction in mRNA expression of COX4, Ndufv1 and Ndufa9 were detected in CXCR4-KO LacZ-treated mice; while their expression levels were returned to normal with AAV9.CXCR4 gene therapy (Figures 6a, b and c respectively) suggesting a great reduction in mitochondrial function in the absence of cardiac CXCR4.

Figure 6.

Transcription profiling reveals alterations in genes regulating mitochondrial function and oxidative stress response. RNA was isolated from whole ventricular tissues of mice subjected to isoproterenol infusion (CXCR4-KO AAV9.lacZ, CXCR4-KO AAV9.CXCR4, CXCR4-f/f-AAV9.LacZ and CXCR4-f/f-AAV9.CXCR4). mRNA levels of genes that are associated with mitochondrial function (a-c), mitochondrial oxidative stress (d-f), and mitochondrial biogenesis (g-h) were quantified via qRT-PCR performed in triplicate (n=3 mice/group *= p<0.05, **=p<0.01).

To confirm our data the expression of key oxidative stress-handling genes were also quantified using qRT-PCR. A major source of mitochondrial injury is oxidative stress produced by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) are among the major families of intracellular antioxidant enzymes in mitochondria that play an important role in limiting oxidative burden.37 The content of oxidative stress handing genes such as GPX, SOD2 and peroxiredoxin 3 (PRDX3) mRNAs were analyzed. Both GPX and PRDX3 were increased in the CXCR4-KO group, while CXCR4 overexpression ameliorated the increase in PRDX3 significantly (p<0.05) and reduced the GPX content to some extent (P=0.091) (Figures 6d, e and f). Mitochondrial biogenesis was also assessed between the CXCR4-KO and the AAV9.CXCR4-rescued groups. We did not see any significant changes in the content of genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis such as: Nuclear respiratory factor-1 (NRF1); Estrogen-related receptor (ERRa); Transcription factor A mitochondrial (TFAm); and the transcriptional co-activator Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1α (PGC1 α) (Figures 6g and h).

Our data collectively suggests that the absence of cardiac specific CXCR4 exacerbates stress related injuries, and thus, mitochondrial gene responses can be significantly modulated by the absence of CXCR4 when they are chronically exposed to isoproterenol. Our data also demonstrates an improvement in mitochondrial function by AAV9.CXCR4 overexpression. The relation between a lack of CXCR4 in cardiomyocytes and the changes in mitochondrial function are not well defined and further studies are necessary to elucidate the mechanisms by which SDF-1α/CXCR4 regulates mitochondrial function during certain pathological conditions e.g. catecholamine-induced myocardial fibrosis and oxidative stress.

Discussion

Cardiac hypertrophy represents a critical compensatory mechanism to hemodynamic stress and injury. In cardiac hypertrophy, alterations of β-adrenergic signaling, increases in myocardial β-AR density and increased expression of hypertrophy-associated proteins have been reported and thus, it is important to assess whether SDF-1α/CXCR4 can limit this response. In our animal model, CXCR4 expression has been selectively abrogated in cardiomyocytes, allowing for an in-depth analysis of SDF-1α/CXCR4 signaling in relation to β-AR activity on cardiac function without interference from other cell types. Our data demonstrates that CXCR4 ablation exacerbates cardiac hypertrophy induced by chronic infusion of isoproterenol, a β-AR agonist. This data supports our previous finding that demonstrated a novel anti-remodeling role of the SDF-1α/CXCR4 chemokine axis following pressure overload.19 Given our previous observations that CXCR4 activation modulates β-AR activity,17 it was critical to understand how β-AR activation affects cardiac function with or without CXCR4 activation. The ability to abrogate CXCR4 activity exclusively in cardiomyocytes allowed us to answer fundamental questions: what is the physiological relevance of its signaling, what electrophysiological pathways are utilized by CXCR4 in hearts that are chronically exposed to isoproterenol? In essence, we hypothesized that cardiomyocytes without CXCR4 may be more sensitive to β-AR activation, and indeed our in vivo results indicate cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy in hearts lacking CXCR4. Our isoproterenol heart failure model is associated with eccentric hypertrophy, which is the result of myocardial apoptosis, decreased contractility and thus myocyte stretch due to increases in wall stress. By echocardiography, there was a slight thinning of the left ventricular septal and posterior wall thickness and significantly higher LV length in diastole and systole in the CXCR4-KO group compared to the other three groups. This reflects significantly higher LV end diastolic and end systolic volumes, and is supported by the significantly higher HW/BW ratio in the CXCR4-KO despite the increase in apoptotic markers. Thus the hypertrophy seen in the CXCR4-KO has to be due to eccentric hypertrophy and not concentric hypertrophy.

One would have expected that the LV end diastolic pressure would have been increased in the CXCR4-KO, which was not the case despite the increase in myocardial fibrosis. In most models of heart failure, diastolic dysfunction precedes systolic dysfunction. However, in some circumstances this is not the case, such as in chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity where the depressed LV systolic function is not necessarily associated with diastolic dysfunction. This could be explained by loss of large amount of cardiomyocytes in a short period of time, but is more reasonably explained by depressed RV function as well. This could be the case in the isoproterenol heart failure model where the damage involves both the LV as well as the RV. Thus the decreases in RV function will decrease the preload of the LV and will falsely contribute to normal LV EDP in the CXCR4-KO group.

We managed to rescue this phenotype and improve cardiac function by AAV9.CXCR4 gene therapy. This suggests that observed significant differences in CXCR4-KO groups are indeed regulated by SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis. Given that mice lacking global CXCR4 (conventional knockout) exhibit hematopoietic and cardiac defects,27 it was interesting to see that cardiomyocyte CXCR4 expression is not required for normal heart development. We believe however, that the axis plays an important role in regulating cardiac myocyte function particularly in response to stress. Our data is not in agreement with the recently published study by Dong et al demonstrating that there is no phenotypic difference between control and cardiomyocytes CXCR4 null mouse following acute myocardial infarction (AMI).38 There are some fundamental differences between their model and ours that might explain the contrasting results. Notably, their model uses AMI, which is associated with an inflammatory reaction that leads to healing and scar formation.39 SDF-1α and CXCR4 are potent chemotactic proteins and play an important role in regulating stem cells recruitment, inflammation and inflammation mediated injury.41 In our model, isoproterenol-induced hypertrophy, inflammation or the recruitment of stem cells by SDF-1α /CXCR4 are not playing major roles this might contribute to the contrasting results that was observed.

The heart is capable of cellular and ventricular chamber remodeling in order to adapt against pathologic and physiologic stimulation. Although the sources of stress are distinguished, they share many molecular, biochemical, and cellular events in common which collectively change the shape of the myocardium 40. Individual myocytes enlarge as a means of reducing ventricular wall and septal stress when faced with increased workload or injury.41 Hypertrophy and cardiomyopathy are reported to alter myocardial oxygen demand.42 Pathological hypertrophy is reported to correlate with a reduction in capillary density. This could ultimately lead to myocardial hypoxia or microischemia which reinforces the pathology. Over an extended period, the additive effects of these conditions lead to activation of cardiac apoptosis effectors; these effectors may then go on to promote the progression from cellular hypertrophy to cell death.

To uncover SDF-1α/CXCR4’s underlying mechanism of action on β-AR induced cardiac hypertrophy, we screened for gene expression profiles correlated with cardiac hypertrophy and failure. This is the first study to utilize cardiac specific CXCR4 knockouts to examine the induction or the regression of genes that were controlled in part by β-AR stimulation. In addition to hypertrophy, β-AR agonists have also been found to modulate oxidative metabolism and energy expenditure,43 and thus we saw it fit to examine mitochondrial and apoptosis related gene expression profiles. Interestingly, upregulation of so many apoptotic induction factors is a testament to how an absence of CXCR4 is sufficient enough to promote apoptotic action in the catecholamine-induced stress condition. Moreover, GSK3β has also been shown to promote apoptosis by a pathway, in which the mitochondria play a critical role.44,45 Emerging evidence indicates that GSK3β is a central regulator of the stress-activated network acting in concert with metabolic sensors of the bioenergetic requirements of the cells. Our data demonstrated significant changes in the expression of key oxidative stress-handling genes, which were increased in CXCR4-KO mice, yet remained normal in AAV9.CXCR4-rescued knockouts, demonstrating an improvement in mitochondrial function. An increase in oxidative stress is a common characteristic and a key initiator in the process of cardiomyocyte loss during the development of heart failure. Since the mitochondria contain proteins that potentially execute apoptosis, it is reasonable to postulate that CXCR4-dependent signaling pathways of cytoprotection converge on this organelle. These results are intriguing and the relation between the absence of CXCR4 in cardiomyocytes and the negative impact on mitochondrial function need to be clarified further.

In conclusion, our present work shed lights on CXCR4 as a novel and direct modulator of cardiac function. Given that β-adrenergic signaling is an important regulator of myocardial function, any potential regulator of β-AR signaling, namely myocardial CXCR4, may have profound implications for the development and/or progression of left ventricular hypertrophy and subsequent heart failure. Thus it will be important to identify and explore new regulators of the cardiac hypertrophic pathways to further understand this complex cardiac response.

Materials and methods

The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health.

Generation of CXCR4 cardiac specific knockouts

We have C57Bl/6 cardiac myocyte-specific CXCR4-null mice (CXCR4-KO) that were obtained by cross-breeding CXCR4/loxP mice, 46, 47, 48 (Jackson laboratory; Bar Harbor, Maine 04609) that contain loxP sites flanking CXCR4 exon 2 with mice carrying a transgene for Cre-recombinase under the control of the cardiac myocyte-specific α-myosin heavy chain promoter (αMHCre+) (courtesy of Dr. Michael Schneider, Baylor College of Medicine).49 Exon 2 of CXCR4 encodes 98% of the CXCR4 molecule. Cre recombinase–mediated deletion of exon 2 abolishes CXCR4 function. Littermates were tested by genotyping tail DNA.

Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV)-mediated gene transfer in mouse model of isoproterenol-induced hypertrophy

Homozygous CXCR4-KO (MHCre+; CXCR4flox/flox ; MHCre f/f) mice at 7-8 weeks of age were used for the experimental procedures. Self-complementary AAV9 was generated using pds.AAV2.eGFP and the CXCR4 gene and/or LacZ control as previously described.19 AAV9.CXCR4 and AAV9.LacZ were administered via tail vein injection at a dose of 1x1011 vg/mouse. At 4 weeks post-injection, baseline cardiac function was evaluated and a mini pump was inserted; we used subcutaneous 14-day osmotic pumps (Alzet, Durect; model 1002) containing isoproterenol (Sigma, I5627; 30 mg/kg/day) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl). The osmotic-pump was implanted on the back of adult mice (CXCR4-KO and/or CXCR4flox/flox (f/f) controls) (25–30 g males) with or without gene transfer of AAV9.CXCR4 or AAV9.LacZ, slightly posterior to the scapulae. In order to obtain maximal remodeling, mice were scarified at three weeks post mini pump implantation. We gave an extra week post-treatment to allow for fibrosis accumulation. All experimental procedures followed the regulations of and were approved by the animal care and use committee of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Echocardiography and in vivo hemodynamic

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal ketamine (100μg/g) for echocardiographic analysis. Two-dimensional images and M-mode tracings were recorded on the short-axis at the level of the papillary muscle and the long axis to determine percent fractional shortening and ventricular dimensions (GE Vivid 7 Vision, i13L transducer). In vivo hemodynamics was studied using a 1.2Fr pressure-volume (PV) conductance catheter (Scisense, Ontario, Canada). Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection mixture of urethane (1mg/g), etomidate (10μg/g), morphine (1μg/g) and were then intubated via a tracheotomy and mechanically ventilated at 7μl/g tidal volume and 125 respirations/minute. The PV catheter was placed in the left ventricle via an apical stab approach as previously described.19 Pressure-volume data were analyzed using IOX2 software (EMKA technologies). All procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Staining procedures for interstitial fibrosis in hypertrophic hearts

At end time point, hearts were perfused with 30 ml of cold PBS with 0.1 ml of 1% heparin. LV was harvested, embedded in OCT, frozen and stored at −80°C. OCT heart sample was sectioned at 6-8 μm. Masson's Trichrome was conducted according to the guideline of the commercially available kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Frozen slides were fixed in Bouin’s solution for 15 minutes at 56°C, Picrosirius Red and Masson's Trichrome staining could be conveniently done on OCT samples with a 60 min incubation at room temperature followed by three washes. The overall procedure for the conventional Masson's Trichrome and Picrosirius Red stain on OCT. After Masson’s trichrome staining, distinct blue collagen fibers and red myocytes were observed in the tissues collected from hypertrophic hearts. In the Picrosirius Red staining method collagen appears red and myocytes are pale yellow.

Protein preparation and immunoblot analysis

Membrane and tissue homogenates were prepared as previously described.19,50 Briefly, Proteins were extracted by using total protein Extraction Kit (Millipore; Darmstadt, Germany). Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay. In all, 30 μg of proteins were then run on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and transferred on polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Following primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting: GSK3β, GSK3β-Phosph(ser9), p53, Bax, CXCR4, SDF-1, and GAPDH. Proteins were visualized using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and exposed using chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore, MA USA).

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assays

Whole ventricular tissues were minced and total RNA extracted using Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL; Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR using Clontech SYBR Advantage qPCR Premix (Clontech Inc; Mountain View, CA). Primers were designed to generate short amplification products. The sequences of the specific primers were: CXCR4 Forward:5’-CGTCGTGCACAAGTGGATCT-3’ and Reverse:5’-GTTCAGGCAACAGTGGAAGAAG-3’; BNP Forward:5’-GCTGCTTTGGGCACAAGATAG and Reverse:5’-GGTCTTCCTACAACAACTTCA-3’; β-MHC Forward:5’-TTGGCACGGACTGCGTCATC-3' and Reverse: 5'-GAGCCTCCAGAGTTTGCTGAAGGA-3'; CXCR7 Forward:5’-GGTCAGTCTCGTGCAGCATA-3’ and Reverse:5’-GTGCTGGTGAAGTAGGTGAT-3’; COX IV Forward:5’-CGCTGAAGGAGAAGGAGAAG-3’ and Reverse:5’-GCAGTGAAGCCAATGAAGAA-3’; NDUFV1 Forward:5’-TGTGAGACCGTGCTAATGGA-3’ and Reverse:5’-CATCTCCCTTCACAAATCGG-3’; NDUFA9 Forward:5’-ATCCCTTACCCTTTGCCACT-3’ and Reverse:5’-CCGTAGCACCTCAATGGACT-3’; GPX Forward:5’-GTCCACCGTGTATGCCTTCT-3’ and Reverse:5’-TCACCATTCACTTCGCACTT-3’; PRDX3 Forward:5’-ACGGAGTGCTGTTGGAAAGT-3’ and Reverse:5’-TTGATCGTAGGGGACTCTGG-3’; SOD2 Forward:5’-ACAACTCAGGTCGCTCTTCA-3’ and Reverse:5’-GAACCTTGGACTCCCACAGA-3’; 18SrRNA Forward:5’-GTTGGTTTTCGGAACTGAGGC-3’ and Reverse:5’-GTCGGCATCGTTTATGGTCG-3’. Reverse transcription was performed using a kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA). Real time PCR was performed in 10-μl reaction volumes using 10 pmol of primers. The relative level of gene expression was calculated according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Ribosomal 18S RNA was used as an internal control to calculate the relative abundance of mRNAs. Expression profiles were tested via commercially available pre-coated plates (SABiosciences; Valencia, CA).

Statistical analyses

Numeric data are presented as mean±S.E.M. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test was performed between all groups at each time point. Student's t-test were also utilized where it was applicable with p-values <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study was supported in part by the American Heart Association (grant GRNT4180006 to S.T.T.) and the National Institutes of Health (grant K02HL102163-01 to S.T.T.). We would like to thank Drs. Roger Hajjar and Antoine Chaanine for their helpful advice and suggestions throughout the data analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary information accompanies the paper on the Gene Therapy website (http://www.nature.com/gt)

REFERENCES

- 1.Tissier R, Berdeaux A, Ghaleh B, Couvreur N, Krieg T, Cohen MV, et al. Making the heart resistant to infarction: how can we further decrease infarct size? Front Biosci. 2008;13:284–301. doi: 10.2741/2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yellon DM, Baxter GF. Protecting the ischaemic and reperfused myocardium in acute myocardial infarction: distant dream or near reality? Heart. 2000;83:381–387. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.4.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carden DL, Granger DN. Pathophysiology of ischaemia-reperfusion injury. J Pathol. 2000;190:255–266. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<255::AID-PATH526>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katholi RE, Couri DM. Left ventricular hypertrophy: major risk factor in patients with hypertension: update and practical clinical applications. International journal of hypertension. 2011:495349. doi: 10.4061/2011/495349. doi:10.4061/2011/495349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Armouche A, Zolk O, Rau T, Eschenhagen T. Inhibitory G-proteins and their role in desensitization of the adenylyl cyclase pathway in heart failure. Cardiovascular research. 2003;60:478–487. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zierhut W, Zimmer HG. Significance of myocardial alpha- and beta-adrenoceptors in catecholamine-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation research. 1989;65:1417–1425. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ungerer M, Bohm M, Elce JS, Erdmann E, Lohse MJ. Altered expression of beta-adrenergic receptor kinase and beta 1-adrenergic receptors in the failing human heart. Circulation. 1993;87:454–463. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadcock JR, Ros M, Watkins DC, Malbon CC. Cross-regulation between G-protein-mediated pathways. Stimulation of adenylyl cyclase increases expression of the inhibitory G-protein, Gi alpha 2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1990;265:14784–14790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao M, Fajardo G, Urashima T, Spin JM, Poorfarahani S, Rajagopalan V, et al. Cardiac pressure overload hypertrophy is differentially regulated by beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2010;301:H1461–1470. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00453.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Port JD, Bristow MR. Altered beta-adrenergic receptor gene regulation and signaling in chronic heart failure. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2001;33:887–905. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore MA, Hattori K, Heissig B, Shieh JH, Dias S, Crystal RG, et al. Mobilization of endothelial and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by adenovector-mediated elevation of serum levels of SDF-1, VEGF, and angiopoietin-1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;938:36–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03572.x. discussion 45-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiasa K, Ishibashi M, Ohtani K, Inoue S, Zhao Q, Kitamoto S, et al. Gene transfer of stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha enhances ischemic vasculogenesis and angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor/endothelial nitric oxide synthase-related pathway: next-generation chemokine therapy for therapeutic neovascularization. Circulation. 2004;109:2454–2461. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128213.96779.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onuffer JJ, Horuk R. Chemokines, chemokine receptors and small-molecule antagonists: recent developments. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:459–467. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen C, Li J, Bot G, Szabo I, Rogers TJ, Liu-Chen LY. Heterodimerization and cross-desensitization between the mu-opioid receptor and the chemokine CCR5 receptor. European journal of pharmacology. 2004;483:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Insel PA, Tang CM, Hahntow I, Michel MC. Impact of GPCRs in clinical medicine: monogenic diseases, genetic variants and drug targets. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1768:994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busillo JM, Benovic JL. Regulation of CXCR4 signaling. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1768:952–963. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaRocca TJ, Schwarzkopf M, Altman P, Zhang S, Gupta A, Gomes I, et al. beta2-Adrenergic receptor signaling in the cardiac myocyte is modulated by interactions with CXCR4. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;56:548–559. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181f713fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lou Q, Janardhan A, Efimov IR. Remodeling of calcium handling in human heart failure. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2012;740:1145–1174. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larocca TJ, Jeong D, Kohlbrenner E, Lee A, Chen J, Hajjar RJ, et al. CXCR4 gene transfer prevents pressure overload induced heart failure. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2012;53:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takefuji M, Wirth A, Lukasova M, Takefuji S, Boettger T, Braun T, et al. G(13)-mediated signaling pathway is required for pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Circulation. 2012;126:1972–1982. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.109256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan J, Fukuda K, Kodama H, Sano M, Takahashi T, Makino S, et al. Involvement of gp130-mediated signaling in pressure overload-induced activation of the JAK/STAT pathway in rodent heart. Heart and vessels. 1998;13:199–208. doi: 10.1007/BF01745045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haq S, Choukroun G, Kang ZB, Ranu H, Matsui T, Rosenzweig A, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta is a negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. The Journal of cell biology. 2000;151:117–130. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson ME. CaMKII and a failing strategy for growth in heart. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:1082–1085. doi: 10.1172/JCI39262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serneri GG, Modesti PA, Boddi M, Cecioni I, Paniccia R, Coppo M, et al. Cardiac growth factors in human hypertrophy. Relations with myocardial contractility and wall stress. Circulation research. 1999;85:57–67. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker KM, Chernin MI, Wixson SK, Aceto JF. Renin-angiotensin system involvement in pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy in rats. The American journal of physiology. 1990;259:H324–332. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.2.H324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaski BE, Jessup ML, Mancini DM, Cappola TP, Pauly DF, Greenberg B, et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease (CUPID Trial), a first-in-human phase 1/2 clinical trial. J Card Fail. 2009;15:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 1998;393:595–599. doi: 10.1038/31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Takakura N, Nishikawa S, Kitamura Y, et al. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature. 1996;382:635–638. doi: 10.1038/382635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma Q, Jones D, Borghesani PR, Segal RA, Nagasawa T, Kishimoto T, et al. Impaired B-lymphopoiesis, myelopoiesis, and derailed cerebellar neuron migration in CXCR4- and SDF-1-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:9448–9453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal U, Ghalayini W, Dong F, Weber K, Zou YR, Rabbany SY, et al. Role of cardiac myocyte CXCR4 expression in development and left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation research. 2010;107:667–676. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berenji K, Drazner MH, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Does load-induced ventricular hypertrophy progress to systolic heart failure? American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2005;289:H8–H16. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01303.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiaffino S, Samuel JL, Sassoon D, Lompre AM, Garner I, Marotte F, et al. Nonsynchronous accumulation of alpha-skeletal actin and beta-myosin heavy chain mRNAs during early stages of pressure-overload--induced cardiac hypertrophy demonstrated by in situ hybridization. Circulation research. 1989;64:937–948. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balabanian K, Lagane B, Infantino S, Chow KY, Harriague J, Moepps B, et al. The chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12 binds to and signals through the orphan receptor RDC1 in T lymphocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:35760–35766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajagopal S, Kim J, Ahn S, Craig S, Lam CM, Gerard NP, et al. Beta-arrestin- but not G protein-mediated signaling by the "decoy" receptor CXCR7. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:628–632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912852107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eom TY, Roth KA, Jope RS. Neural precursor cells are protected from apoptosis induced by trophic factor withdrawal or genotoxic stress by inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase 3. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:22856–22864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702973200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rimbaud S, Garnier A, Ventura-Clapier R. Mitochondrial biogenesis in cardiac pathophysiology. Pharmacological reports : PR. 2009;61:131–138. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreno-Lastres D, Fontanesi F, Garcia-Consuegra I, Martin MA, Arenas J, Barrientos A, et al. Mitochondrial complex I plays an essential role in human respirasome assembly. Cell metabolism. 2012;15:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaya Y, Cebi A, Soylemez N, Demir H, Alp HH, Bakan E. Correlations between oxidative DNA damage, oxidative stress and coenzyme Q10 in patients with coronary artery disease. International journal of medical sciences. 2012;9:621–626. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong F, Harvey J, Finan A, Weber K, Agarwal U, Penn MS. Myocardial CXCR4 expression is required for mesenchymal stem cell mediated repair following acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:314–324. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.082453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Entman ML, Smith CW. Postreperfusion inflammation: a model for reaction to injury in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular research. 1994;28:1301–1311. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.9.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunter JJ, Chien KR. Signaling pathways for cardiac hypertrophy and failure. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;341:1276–1283. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaasch WH. Left ventricular radius to wall thickness ratio. The American journal of cardiology. 1979;43:1189–1194. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(79)90152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hudlicka O, Brown M, Egginton S. Angiogenesis in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Physiological reviews. 1992;72:369–417. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoeks J, van Baak MA, Hesselink MK, Hul GB, Vidal H, Saris WH, et al. Effect of beta1- and beta2-adrenergic stimulation on energy expenditure, substrate oxidation, and UCP3 expression in humans. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2003;285:E775–782. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00175.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beurel E, Jope RS. The paradoxical pro- and anti-apoptotic actions of GSK3 in the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis signaling pathways. Progress in neurobiology. 2006;79:173–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomez-Sintes R, Hernandez F, Lucas JJ, Avila J. GSK-3 Mouse Models to Study Neuronal Apoptosis and Neurodegeneration. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2011;4:45. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Subramaniam A, Jones WK, Gulick J, Wert S, Neumann J, Robbins J, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of the alpha-myosin heavy chain gene promoter in transgenic mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:24613–24620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrich BG, Molkentin JD, Wang Y. Temporal activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in adult transgenic heart via cre-loxP-mediated DNA recombination. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2003;17:749–751. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0438fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nie Y, Waite J, Brewer F, Sunshine MJ, Littman DR, Zou YR. The role of CXCR4 in maintaining peripheral B cell compartments and humoral immunity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2004;200:1145–1156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agah R, Frenkel PA, French BA, Michael LH, Overbeek PA, Schneider MD. Gene recombination in postmitotic cells. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase provokes cardiac-restricted, site-specific rearrangement in adult ventricular muscle in vivo. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;100:169–179. doi: 10.1172/JCI119509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tarzami ST, Calderon TM, Deguzman A, Lopez L, Kitsis RN, Berman JW. MCP-1/CCL2 protects cardiac myocytes from hypoxia-induced apoptosis by a G(alphai)-independent pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:1008–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.