Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated the protective effect of beta-carotene (BC) on titanium oxide nanoparticle (TNP) induced spermatogenesis defects in mice.

Materials and methods

Thirty-two NMRI mice were randomly divided into four groups. BC group received 10 mg/kg of BC for 35 days. TNP group received 300 mg/kg TNP for 35 days. TNP+BC group initially received 10 mg/kg BC for 10 days and was followed by concomitant administration of 300 mg/kg TNP for 35 days. Control group received only normal saline for 35 days. Epididymal sperm parameters, testicular histopathology, spermatogenesis assessments and testosterone assay were performed for evaluation of the TNP and BC effects on testis.

Results

Serum testosterone levels were markedly decreased in TNP-intoxicated mice. Epididymal sperm parameters including sperm number, motility and percentage of abnormality were significantly changed in TNP-intoxicated mice (p < 0.01). Histopathological criteria such as epithelial vacuolization, sloughing of germ cells and detachment were significantly increased in TNP-intoxicated mice (p < 0.001). BC+TNP treatment significantly prevented these changes (p < 0.05). BC also significantly elevates testosterone levels in BC+TNP group compared to TNP-treated mice (p < 0.01).

Discussion and conclusion

The results of this study demonstrated that BC improved the spermatogenesis defects in TNP-treated mice. BC had a potent protective effect against the testicular toxicity and might be clinically useful.

Keywords: Beta- carotene, Titanium oxide nanoparticles, Spermatogenesis

Introduction

Spermatogenesis is a complex process of germ cell proliferation and differentiation which leads to the production and release of spermatozoa from the testis. This elaborate process is dependent on hormonal or dynamic interactions between the Sertoli cells and the germ cells [1, 2] as well as between Leydig cells and germ cells. Tight junctions between adjacent Sertoli cells create two separate compartments within the seminiferous epithelium: a basal compartment below the tight junction and an adluminal compartment above. Sertoli cells secrete hormonal and nutritive factors into the adluminal compartment which creates a specialized microenvironment for development and viability of germ cells. In addition, Sertoli cells provide efficient paracrine signaling mechanisms between these cells as well as physical support to developing germ cells [3]. Leydig cells synthesis and release testosterone. Testosterone is an essential factor for spermatogenesis process [2]. The intricate regulation and cellular interactions that occur in the testis provide multiple distinct targets by which toxicants can disrupt spermatogenesis [2].

Many recent in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrate that most nanoparticles (NPs) have an adverse or toxic action on male germ cells [4, 5]. NPs are materials with at least one dimension ≤100 nm, and this large surface-to-volume ratio results in unique characteristics compared to their corresponding bulk materials [6]. The administration of NPs to mice resulted in their accumulation in the various tissues including the brain and the testis, indicating that they easily pass through the blood–brain and blood–testis barriers [7, 8]. Among the various metal nanomaterials, titanium oxide nanoparticules (TNPs), is used in a variety of consumer products such as sunscreens, cosmetics, clothing, electronics, paints, and surface coatings [9, 10].

The TNP can be harmful to human and animal health [11–13].

Since NPs, such as TNP affect testis homeostasis and its high rate usage, it seems essential to find a suitable medication for neutralizing or decreasing their negative side effects.

Carotenoids are naturally occurring pigments found in plants, and are largely responsible for the vibrant colors of some fruits and vegetables. Beta-carotene (BC) is the most widely studied carotenoid. BC is either converted into vitamin A (retinol), which the body can use in a variety of ways, or it acts as an antioxidant to help protect cells from the damaging effects of harmful free radicals [14].

BC possesses a wide array of pharmacological and biological activities including: antioxidant, radioprotective, cardiovascular protection, antiepilepsy [15–19]. Previous studies have demonstrated protective action of BC against some toxicants including Fenvalerate, metotroxate and Cadmium [20–22]. It has been reported that increases in plasma carotenoid concentration associates with increases in sperm motility and velocity [23]. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to evaluate the ameliorating effect of BC on TNP-induced testicular defects in mice.

Materials and methods

Animals

In this study, 32 healthy adult male NMRI (Naval Medical Research Institute) mice (6–8 weeks old, 25–30 g) were used. This study was carried out in an ethically proper way by following the guidelines provided. The animals were kept under standard laboratory conditions (12 h dark and 12 h light cycle, relative humidity of 50 ± 5 % and 22 ± 3 °C) for at least 1 week before the experiment and those conditions were preserved until the end of the experiment. Animal cages were kept clean, and commercial food (pellet) and water were provided ad libitum.

Experimental design

The mice were randomly divided into four groups, all of which contained eight animals. The first (control) group received 0.2 ml normal saline for 35 days. The second group received 10 mg/kg BC for 35 days. Third group (TNP-intoxicated mice) received 300 mg/kg TNP for 35 days. Forth group (TNP+BC) initially received 10 mg/kg BC for 10 days and was followed by concomitant administration of 300 mg/kg TNP for 35 days. All group received the drugs by gavages.

The duration time of treatment was selected according to the timing of mouse spermatogenesis [24]. The doses of TNP (Sigma) were selected according to previous studies that demonstrated significant toxicity in rodents [25]. No published data was available about the daily exposure doses of TNP in human. However, TNP increasing use increases the health risk of people exposed to these particles, either occupationally or environmentally. Thus, we used the toxic dose of TNP to evaluate whether beta carotene could prevent toxic effects of TNP.

The stock solution of TNP (2 mg/ml) was prepared in Milli-Q water and dispersed for 10 min by using a sonicator to prevent aggregation. The stock solution of TNP was kept at 4 °C and used within 1 week for the experiments. Prior to each experiment, the stock solution was sonicated on ice for 10 min, then immediately diluted in Milli-Q water [26]. BC (Sigma) was diluted in saline solution. The dose of BC and the duration time of pre-treatment was selected based on the results of previous studies [21, 27, 28].

One day after the last administration, after blood sampling, the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under ether anesthesia and testicles from each animal were dissected out, weighed and then fixed in Bouin’s solution. The samples were embedded in paraffin, sectioned (5 μm) and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathology and Johnsen’s scoring.

Testosterone assay

The blood samples were collected in heparinized centrifuge tubes and centrifuged to obtain serum. Serum testosterone concentration was measured by radio immunoassay (RIA) method. Testosterone was also extracted from testes as previously described [29]. Briefly, testes were homogenized by sonication and centrifuged at 5,900 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was combined with an equal volume of ethyl acetate, and the organic phase was dried under a stream of N2 gas at room temperature and reconstituted in 1× PBS. The concentration of testosterone by this procedure was estimated by RIA.

Epididymal sperm parameters

Spermatozoa were taken from right epididymal cauda and placed into a petri dish containing 1 ml saline of the motility and frequency of morphologically abnormal spermatozoa. One drop of suspension was put onto concave object glass and observed under the microscope with magnification of 400×. The observation was carried out onto 100 spermatozoa with five times replication in each mouse. Motility is graded by the criteria according to the World Health.

Organization (WHO) Manual as “a” to “d”. This is detailed as below:

Grade a (fast progressive) sperms are those which swim forward fast in a straight line—like guided missiles.

Grade b (slow progressive) sperms swim forward, but either in a curved or crooked line, or slowly (slow linear or non linear motility).

Grade c (no progressive) sperms move their tails, but do not move forward (local motility only).

Grade d (immotile) sperms do not move at all.

A drop of suspension was put onto an object glass, stained with 1 % eosin and 10 % nigrosin, and smeared. Morphological observation was conducted in 100 spermatozoa with five replication in each mouse with magnification of 400×. The observation data were differentiated based on normal and abnormal morphology. The morphology was regarded as normal when the acrosome is curved like a hook, and the neck is straight with free-end single tail. Abnormal morphology was found when the head was smaller than normal, the neck was broken, the tail was branched or cut, etc. The left epididymis was macerated and minced in 0.8 ml of 1 % trisodium citrate solution for 7–8 min, then more solution was added (up to total amount 8 ml) and mixed for about 1 min. The sperm suspension was diluted 1:1 in 10 % buffered formalin. The sperm suspension from right testes was diluted 1:1 in 10 % buffered formalin. Spermatozoa were counted using improved Neubauer haemocytometer [30–34]. Three observers, blinded to the control and experimental groups, analyzed the sperm parameters independently.

Histopathology

Six microscopy slides per animal were examined for signs of germ cell degeneration including the following histopathological alterations: detachment (appearance of breaking off of cohorts of spermatocytes from the seminiferous epithelium), sloughing (release of clusters of germ cells into the lumen of the seminiferous tubule) and vacuolization (appearance of empty spaces in the seminiferous tubules). For each treatment, the average percentage of normal and regressed tubules was determined.

Average percentages were calculated for each sample by dividing the number of round tubules with a histopathology index (vacuolization, detachment, sloughing) or normal tubules in a randomly microscopic field by the total number of round tubules in the same field and the result multiplied by 100. For each slide the mean of three fields was considered [35, 36].

Assessment of spermatogenesis

Maturity of the germinal epithelium was graded by using the modified Johnsen’s scoring method [37, 38], a simple way for assessment of spermatogenesis. By using a 40× magnification, 150 tubules per animal were evaluated and each tubule was given a score ranging from 1 to 10. The tubules having complete inactivity were scored as 1 and those with maximum activity (at least five or more spermatozoa in the lumen) scored as 10.

Statistical analysis

The data were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). This was followed by post hoc pair-wise comparison using the Bonferroni t-procedure. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS for Windows, Version 15.0. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Organ weight

Comparing body and testis weight in animals of the four treatment groups with a one way ANOVA followed by pair-wise comparisons showed that the body weight in all groups was the same and no difference was detected between them. Weight of testicles in the BC groups was slightly more than control group (p > 0.05). A significant reduction in testicular weight was observed in the TNP-intoxicated mice compared to the control (p < 0.05). Pre-treatment with BC significantly changed the testis weight compared to TNP-intoxicated animals (Table 1). Relative testes weight was obtained by dividing testes weight by body weight. Relative testes weight in TNP group was significantly lower than the control and BC group (p < 0.05). BC+TNP group showed a significant increase in relative testis weight in comparison to TNP-intoxicated group. These results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Testis and body weight for control and experimental groups

| Group | Body weight (g) | Testis weight (mg) | Testis/body (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 30.3 ± 3.29 | 113.1 ± 11.2 | 3.75 ± 0.82 |

| BC | 30.4 ± 4.3 | 113.5 ± 9.3 | 3.8 ± 0.75 |

| TNP | 29.25 ± 2.3* | 93.3 ± 10.30* | 3.1 ± 0.70* |

| BC+TNP | 30.2 ± 3.7†† | 107.4 ± 9.7 | 3.5 ± 0.54† |

Values expressed as mean ± SD for eight mice. *p < 0.01, † p < 0.01; * and † symbols respectively indicate comparison to control and TNP groups

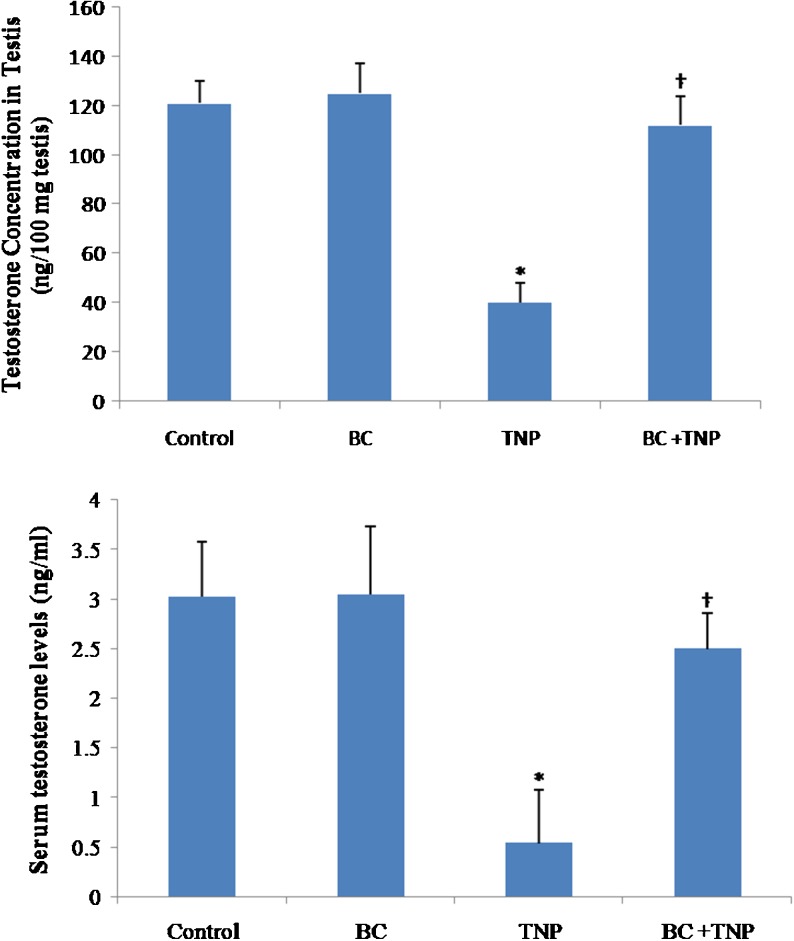

Testosterone assay

A pair-wise comparison used to compare testosterone levels in serum and testis of each group. As shown in Fig. 1, no significant changes were observed between control and BC groups in serum and testis testosterone levels (p > 0.05). The serum and testis testosterone concentration were significantly reduced in TNP-intoxicated animals (p < 0.01). There was a markedly increase in serum and testis testosterone levels in TNP+BC group compared to TNP-treated animals (p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Testosterone assessment of control and experimental groups. Values expressed as mean ± SD for eight mice. *p < 0.01, † p < 0.01; * and † symbols respectively indicate comparison to control and TNP-intoxicated groups

Epididymal sperm parameters

A pair-wise comparison used to compare epididymal sperm parameters from each treatment group. There were no significant changes in motility, abnormality and the number of sperms in the BC groups compared to the control. Exposure of the mice to the TNP exhibited a significant reduction in sperm number. In TNP+BC treated animals a significant increase in the sperm number was observed compared to the TNP-intoxicated mice (p < 0.01).

Exposure of the animals to TNP significantly reduced the sperm motility compared to the control group (p < 0.01). Treatment of the animals with TNP significantly increased the abnormality of sperms (p < 0.05). Treatment with BC+TNP significantly changed the abnormality and motility of the sperms in comparison to TNP-intoxicated animals (p < 0.01). The results of epididymal sperm parameters are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Epididymal sperm parameters in control and experimental groups. Values expressed as mean ± SD for eight mice. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, † p < 0.001; * and † symbols respectively indicate comparison to control and TNP-intoxicated groups

Histopathology

A pair-wise comparison used to compare histopathological criteria from each treatment group. Testicular sections from the control group showed normal spermatogenesis with a low incidence of detached, sloughed or vacuolized seminiferous tubules (Fig. 3a). Normal architecture of the seminiferous tubules and intact germinal epithelium were observed in BC group (Fig. 3b). There was no significant difference in the histopathology criteria between BC and control groups (p > 0.05). In the TNP-intoxicated group, varying degrees of germ cell degenerative changes was occurred, ranging from loss of elongated spermatids, disorganization of germ cell layers, detachment and sloughing to vacuolization of the seminiferous tubules, contributing to eventual atrophy (Fig. 3c). There was a significant increase in all histopathology criteria in TNP-treated mice (p < 0.001). In TNP+BC group (Fig. 3d), all histopathology criteria were significantly decreased compared to TNP- treated animals (p < 0.05). The results of histopathology assessments are shown in Table 2. There was no visible damages in Leydig cells of various groups.

Fig. 3.

Light microscopy of cross sections of H&E stained testis from control and experimental groups. a Control group; b BC group; c TNP-intoxicated group; d BC+TNP group. V vacuole, S slough, D deteched, * atrophy. Magnification: ×100

Table 2.

Testis histopathology assessments for control and experimental groups

| Group | Percentage of tubules | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Detached | Sloughed | Vacuolized | |

| Control | 90.12 ± 8.9 | 3.85 ± 1.29 | 2.15 ± 0.48 | 3.51 ± 0.77 |

| BC | 89.22 ± 9.2 | 4.63 ± 0.78 | 2.15 ± 0.75 | 2.9 ± 0.81 |

| TNP | 22.47 ± 3.5** | 41.93 ± 4.4** | 20.50 ± 4.7** | 20.50 ± 4.8** |

| BC+TNP | 69.42 ± 5.7*†† | 9.92 ± 1.9*†† | 12.53 ± 3.2*† | 12.53 ± 1.7*† |

Values expressed as mean ± SD for eight mice. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, † p < 0.01, †† p < 0.001; * and † symbols respectively indicate comparison to control and TNP groups

Assessment of spermatogenesis

A pair-wise comparison used to compare Johnsen’s score from each treatment group. In control and BC groups, normal spermatogenesis was observed and there was no significant difference in the mean Johnsen’s score between them (p > 0.05). In TNP-intoxicated mice, all sections contain a number of tubules with maturation arrest and the mean Johnsen’s score was significantly less than control group (p < 0.05). In TNP+BC group, some sections contain a few tubules in which spermatogenesis were abnormal and the mean Johnsen’s score was slightly lower than the control (p > 0.05). The results of the mean Johnsen’s score are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Johnsen’s score in control and experimental groups. Values expressed as mean ± SD for eight mice. *p < 0.01, † p < 0.01; * and † symbols respectively indicate comparison to control and TNP-intoxicated groups

Discussion

There are many studies of the testis after NPs treatment but researches about to find a suitable medication for neutralizing or decreasing their negative side effects have received little attention. In present study protective effect of beta-carotene on TNP-induced testicular damage was investigated. Data from our study demonstrated that TNP-treatment decreased testis weight and relative testis weight, serum and testis testosterone concentration, epididymal sperm parameters and Johnsen scoring. While, BC pre-treatment increased the weight of testis and relative testis weight, serum and testis testosterone concentration, epididymal sperm parameter and Johnsen scoring.

With a histopathological observation, it was possible to determine alterations in testis morphology. In general, the major deleterious effects of the TNP in affected tubules were the occurrence of intraepithelial vacuoles of varying size, slouging and seminiferous tubule atrophy. The vacuoles we observed within the seminiferous epithelium resembled those described following a variety of testicular insults including exposure to toxicants, hypophysectomy, transient scrotal heat stress and acute withdrawal of androgens following destruction of Leydig cells with ethane dimethane sulphonate [39–43]. Sloughing is caused by the effects of the chemical on microtubules and intermediate filaments of the Sertoli cell. These effects spread to dividing germ cells and also lead to abnormal development of the elongating spermatids [44].

The present study demonstrated that TNP induced a significant reduction in sperm count, sperm motility and morphology. This is in agreement with that of Guo et al., who reported that TNP treatment in rats caused a significant decrease in sperm count and motility [45]. It has been reported that the decrease in sperm count and motility are valid indices of male infertility in laboratory animals [46, 47]. However, sperm motility is often used as a marker of chemical-induced testicular toxicity [48].

In this study, the TNP exposed testis also showed a statistically significant decrease of Johnsen scores. This indicates that TNP can induce spermatogenesis damage. Diminution in the testis weights and relative testis weight in TNP-treated mice also supports the toxic effect of TNP on mouse testicles. As the body growth was not significantly altered in TNP-treated mice, the effect of TNP on the testis may be due to its specific toxic effect on the target organ and not the result of its general toxicity.

Previous studies also demonstrated toxic action of NPs on male germ cells. Braydich-Stolle et al. showed that mammalian spermatogonial stem cells are sensitive to TNP [5]. Gromadzka-Ostrowska et al. demonstrated that even small amounts of silver NPs had a toxic impact on the germ cells and reduced sperm quality [31].

There was no visible damage in Leydig cells in TNP-intoxicated mice. However, the significant decrease in both serum and testis testosterone concentration indicates that TNP affect Leydig cell function. Komatsu et al., have reported that Titanium oxide and carbon black nanoparticles were taken up by mouse Leydig TM3 cells, and affected the viability, proliferation and gene expression [49]. Yoshida et al. reported that exposure to diesel exhaust nanoparticles induce Leydig cell degeneration, increase the number of damaged seminiferous tubules, and reduce daily sperm production [50].

This study revealed that BC pre-treatment for 10 days could effectively reduce the toxic action of TNP on mouse spermatogenesis. The dose and pre-treatment duration of β-carotene used in this study were selected on the basis of the studies previously published elsewhere. Lyama et al. showed that oral administration of BC for 10 days led to its accumulation in mouse various tissues and excrete a protective role against oxidative stress [28].

The exact mechanism of BC action on spermatogenic defects induced by TNP is not obtained from this study. However, the reduction of sloughing of immature germ cells from the seminiferous tubules, and vacuolization of germinal epithelium in BC pre-treatment indicates its benifical affects on Sertoli cell functions.

This study revealed that BC elevated the testosterone concentration in TNP-intoxicated mice. Thus, the protection in gametogenic activity in BC pre-treated mice may be the result of restoration of testicular androgenesis, as androgen is a prime regulator of gametogenesis [51]. The TNP-induced spermatogenic damage may also be due to the formation of free radical products in the testicular tissue as they exert a detrimental effect on spermatogenesis [52].

Thus, the protective action of BC may also be due to its antioxidant effect [21, 53, 54].

El-Demerdash et al. demonstrated the beneficial influences of vitamin E, β-carotene alone and/or in combination improved semen quality in Fenvalerate-induced changes in oxidative stress, hemato-biochemical parameters, and semen quality of male rats [23].

Epididymal sperm parameters were also positively changed in BC pre-treated animals. Previous studies also demonstrated that BC improved semen quality [20, 22, 55]. In Eskenazi’s study vitamins C, E and beta-carotene were associated with semen quality in 97 healthy non-smoking men. They revealed that a high intake of antioxidants is associated with better sperm quality [56].

The reduction in testis weight induced by TNP was reversed by BC. This indicates that BC can effectively improve testicular damage. The significant increase in Johnsen’s scoring in BC+TNP group also indicated that BC can effectively improve spermatogenesis. The reduction in the Johnsen’s scoring in TNP-intoxicated mice may relate to induction of apoptosis in testicular germ cells. Thus another possibility is that BC may inhibit germ cell apoptosis induced by TNP.

Vardi et al. showed that BC had anti oxidant and anti apoptotic effects on methotrexate induced testicular injury in wister rat [21]. Peng et al. demonstrated that BC decreased oxidative stress and prevented ethanol-induced hepatic cell death by inhibiting caspase-9 and caspase-3 expression [57]. Lin et al. revealed that BC effectively protected against nicotine-induced teratogenesis in mouse embryos through its antioxidative, antiapoptotic, and anti-inflammatory activities [58].

Conclusions

In the present study, we have found that BC has an ameliorating effect against TNP induced testicular germ cell damage in mice. BC may be a valuable protective agent to ameliorate spermatogenesis dysfunction and cell loss. The exact mechanism by which BC reduces testicular injury is not obtained from this study. Further experiments are needed to clarify the mechanisms of the effect of BC on nanoparticles toxicity.

Acknowledgments

This paper was issue from thesis of Erfan Daneshi and was supported by a Grant (CMRC-84) from the research council of the Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences in 2013.

Footnotes

Capsule Beta-carotene has an ameliorating effect against titanium oxide nanoparticlesinduced testicular germ cell damage in mice.

References

- 1.Franca LR, Ghosh S, Ye SJ, Russell LD. Surface and surface to volume relationships of the Sertoli cells during the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium in the rat. Biol Reprod. 1993;49(6):1215–28. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod49.6.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boekelheide K, Fleming SL, Johnson KJ, Patel SR, Schoenfeld HA. Role of Sertoli cells in injury-associated testicular germ cell apoptosis. Exp Biol Med. 2000;225(2):105–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Cell junction dynamics in the testis: Sertoli-germ cell interactions and male contraceptive development. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(4):825–74. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braydich-Stolle LK, Lucas B, Schrand A, Murdock RC, Lee T, Schlager JJ, et al. Silver nanoparticles disrupt GDNF/Fyn kinase signaling in spermatogonial stem cells. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116(2):577–89. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braydich-Stolle L, Hussain S, Schlager JJ, Hofmann MC. In Vitro cytotoxicity of nanoparticles in mammalian germline stem cells. Toxicol Sci. 2005;88(2):412–9. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roduner E. Size matters: why nanomaterials are different. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35(7):583–92. doi: 10.1039/b502142c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borm PJ, Kreyling W. Toxicological hazards of inhaled nanoparticles potential implications for drug delivery. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2004;4(5):521–31. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2004.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Xue Z, Zheng D, Xia K, Zhao Y, Liu T, et al. Sodium chloride modified silica nanoparticles as a non-viral vector with a high efficiency of DNA transfer into cells. Curr Gene Ther. 2003;3(3):273–9. doi: 10.2174/1566523034578339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher J, Egerton T, Kirk-Othmer . Encyclopedia of chemical technology. New York: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaida T, Kobayashi K, Adachi M, Suzuki F. Optical characteristics of titanium oxide interference film and the film laminated with oxides and their applications for cosmetics. J Cosmet Sci. 2004;55(2):219–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberdorster G, Oberdorster E, Oberdorster J. Nanotoxicology: an emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(7):823–39. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warheit DB, Hoke RA, Finlay C, Donner EM, Reed KL, Sayes CM. Development of a base of toxicity tests using ultrafine TiO2 particles as a component of nanoparticle risk management. Toxicol Lett. 2007;171(3):99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma L, Liu J, Li N, Wang J, Duan Y, Yan J, et al. Oxidative stress in the brain of mice caused by translocated nanoparticulate TiO2 delivered to the abdominal cavity. Biomaterials. 2010;31(1):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martín JF, Gudiña E, Barredo JL. Conversion of β-carotene into astaxanthin: two separate enzymes or a bifunctional hydroxylase-ketolase protein? Microb Cell Factories. 2008;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schweiggert RM, Kopec RE, Villalobos-Gutierrez MG, Högel J, Quesada S, Esquivel P, et al. Carotenoids are more bioavailable from papaya than from tomato and carrot in humans: a randomised cross-over study. Br J Nutr. 2013;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krinsky NI. Antioxidant functions of carotenoids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;7(6):617–35. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salvadori DM, Ribeiro LR, Xiao Y, Boei JJ, Natarajan AT. Radioprotection of beta-carotene evaluated on mouse somatic and germ cells. Mutat Res. 1996;356(2):163–70. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gopal K, Nagarajan P, Jedy J, Raj AT, Gnanaselvi SK, Jahan P, et al. β-carotene attenuates angiotensin II-induced aortic aneurysm by alleviating macrophage recruitment in Apoe-/- mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sayyah M, Yousefi-Pour M, Narenjkar J. Anti-epileptogenic effect of beta-carotene and vitamin A in pentylenetetrazole-kindling model of epilepsy in mice. Epilepsy Res. 2005;63(1):11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Demerdash FM, Yousef MI, Kedwany FS, Baghdadi HB. Role of α-tocopherol and β-carotene in ameliorating the fenvalerate-induced changes in oxidative stress, hemato-biochemical parameters, and semen quality of male rats. J Environ Sci Health B. 2004;39(3):443–59. doi: 10.1081/PFC-120035929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vardi N, Parlakpinar H, Ates B, Cetin A, Otlu A. Antiapoptotic and antioxidant effects of b-carotene against methotrexate-induced testicular injury. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(6):2028–33. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Demerdash FM, Yousef MI, Kedwany FS, Baghdadi HH. Cadmium-induced changes in lipid peroxidation, blood hematology, biochemical parameters and semen quality of male rats: protective role of vitamin E and beta-carotene. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004;42(10):1563–71. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almbro M, Dowling DK, Simmons LW. Effects of vitamin E and beta-carotene on sperm competitiveness. Ecol Lett. 2011;14(9):891–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hess RA, Chen PP. Computer of germ cells in the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium and prediction of changes in the cycle duration in animals commonly used in reproductive biology and toxicology. J Androl. 1992;13:185–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid TE, Attia S, Baumgartner A, Nuesse M, Adler ID. Effect of chemicals on the duration of male meiosis in mice detected with laser scanning cytometry. Mutagenesis. 2001;16(4):339–43. doi: 10.1093/mutage/16.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Shi H, Ruth M, Yu H, Lazar L, Zou B, et al. Acute toxicity of intravenously administered titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matos HR, Marques SA, Gomes OF, Silva AA, Heinmann JC, Mascio PD, et al. Lycopene and β-carotene protect in vivo iron-induced oxidative stress damage in rat prostate. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39(2):203–10. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyama T, Takasuga A, Azuma M. Beta-carotene accumulation in mouse tissues and a protective role against lipid peroxidation. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1996;66(4):301–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Habertand R, Picon R. Control of testicular steroidogenesis in foetal rat: effect of decapitation on testosterone and plasma luteinizing hormone-like activity. Acta Endocrinol. 1982;99(3):466–73. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0990466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jadhav MV, Sharma RC, Rathore Mansee, Gangawane AK. Effect of Cinnamomum camphora on human sperm motility and sperm viability. J Clin Res Lett. 2010;1(1):01–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gromadzka-Ostrowskaa J, Dziendzikowskaa K, Lankoffb A, Dobrzyńska M, Instanes C, Brunborg G, et al. Silver nanoparticles effects on epididymal spermin rats. Toxicol Lett. 2012;214(3):251–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Talebi AR, Khorsandi L, Moridian M. The effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on mouse spermatogenesis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(9):1203–9. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khani B, Rabbani Bidgoli S, Moattar F, Hassani H. Effect of sesame on sperm quality of infertile men. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(3):184–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hajshafiha M, Ghareaghaji R, Salemi S, Sadegh-Asadi N, Sadeghi-Bazargani H. Association of body mass index with some fertility markers among male partners of infertile couples. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:447–51. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S41341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oatley JM, Tibary A, de-Avila DM, Wheaton JE, McLean DJ, Reeves JJ. Changes in spermatogenesis and endocrine function in the ram testis due to irradiation and active immunization against luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. J Anim Sci. 2005;83(3):604–12. doi: 10.2527/2005.833604x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orazizadeh M, Khorsandi LS, Hashemitabar M. Toxic effects of dexamethasone on mouse testicular germ cells. Andrologia. 2010;42(4):247–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnsen SG. Testicular biopsy score count: a method for registration of spermatogenesis in human testis. Hormones. 1970;1:2–25. doi: 10.1159/000178170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khorsandi L, Mirhoseini M, Mohamadpour M. Toxic effects of Carthamus tinctorius L (Safflower) extract on mouse spermatogenesis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(5):457–61. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9734-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hooley RP, Paterson M, Brown P, Kerr K, Saunders PTK. Intra-testicular injection of adenoviral constructs results in Sertoli cell-specific gene expression and disruption of the seminiferous epithelium. Reproduction. 2009;137(2):361–70. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creasy DM, Beech LM, Gray TJ, Butler WH. The ultrastructural effects of di-n-pentyl phthalate on the testis of the mature rat. Exp Mol Pathol. 1987;46:357–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(87)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghosh S, Sinha-Hikim AP, Russell LD. Further observations of stage-specific effects seen after short-term hypophysectomy in the rat. Tissue Cell. 1991;23:613–30. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(91)90018-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paul C, Murray A, Spears N, Saunders P. A single, mild, transient scrotal heat stress causes DNA damage, subfertility and impairs formation of blastocysts in mice. Reproduction. 2008;136:73–84. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerr JB, Savage GN, Millar M, Sharpe RM. Response of the seminiferous epithelium of the rat testis to withdrawal of androgen: evidence for direct effect upon intercellular spaces associated with Sertoli cell junctional complexes. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;274:153–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00327996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hess RA, Nakai M. Histopathology of the male reproductive system induced by the fungicide benomyl. Histol Histopathol. 2000;15(1):207–24. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo LL, Liu XH, Qin DX, Gao L, Zhang HM, Liu JY, et al. Effects of nanosized titanium dioxide on the reproductive system of male mice. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2009;15(6):517–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khaki A, Heidari M, Ghaffari Novin M, Khaki AA. Adverse effects of ciprofloxacin on testis apoptosis and sperm parameters in rats. Iran J Reprod Med. 2008;6(2):71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Working PK, Chellman GJ. The testis, spermatogenesis and the excurrent duct system. In: Scialli AR, Zinaman MJ, editors. Reproductive toxicology and infertility. New York: McGraw Hill; 1993. pp. 55–76.

- 48.Bitman J, Cecil HC. Estrogenic activity of DDT analoges and polychlorinated biphenyls. J Agric Food Chem. 1970;18:1108–12. doi: 10.1021/jf60172a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Komatsu T, Tabata M, Kubo-Irie M, Shimizu T, Suzuki K, Nihei Y, et al. The effects of nanoparticles on mouse testis Leydig cells in vitro. Toxicol in Vitro. 2008;22(8):1825–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshida S, Sagai M, Oshio S, Umeda T, Ihara T, Sugamata M, et al. Exposure to diesel exhaust affects the male reproductive system of mice. Int J Androl. 1999;22(5):307–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1999.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sofikitis N, Giotitsas N, Tsounapi P, Baltogiannis D, Giannakis D, Pardalidis N. Hormonal regulation of spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;109(3–5):323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahotupa M, Huhtaniemi I. Impaired detoxification of reactive oxygen and consequent oxidative stress in experimentally criptorchid rat testis. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:1114–8. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.6.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peters A, Denk AG, Delhey K, Kempenaers B. Carotenoid-based bill colour as an indicator of immuno-competence and sperm performance in male mallards. J Evol Biol. 2004;17(5):1111–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matos HR, Marques SA, Gomes OF, Silva AA, Heinmann JC, Mascio PD. Lycopene and b-carotene protect in vivo iron-induced oxidative stress damage in rat prostate. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39(2):203–10. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.el-Demerdash FM, Yousef MI, Kedwany FS, Baghdadi HH. Role of alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene in ameliorating the fenvalerate-induced changes in oxidative stress, hemato-biochemical parameters, and semen quality of male rats. J Environ Sci Health B. 2004;39(3):443–59. doi: 10.1081/PFC-120035929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eskenazi B, Kidd SA, Marks AR, Sloter E, Block G, Wyrobek AJ. Antioxidant intake is associated with semen quality in healthy men. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(4):1006–12. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peng HC, Chen JR, Chen YL, Yang SC, Yang SS. Beta-Carotene exhibits antioxidant and anti-apoptotic properties to prevent ethanol-induced cytotoxicity in isolated rat hepatocytes. Phytother Res. 2010;24(2):S183–9. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin C, Yon JM, Jung AY, Lee JG, Jung KY, Lee BJ, et al. Antiteratogenic effects of β-carotene in cultured mouse embryos exposed to nicotine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2013/575287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]