Abstract

Purpose

Estrogens play an important role in male reproduction via interacting with estrogen receptors (ERs), whose expression can be regulated by the polymorphisms in different regions of ESR1 and ESR2 genes. However, results from published studies on the association between four well-characterized polymorphisms (PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, and AluI) in the gene of ERs (ESR1 and ESR2) and male infertility risk are inconclusive.

Methods

To investigate the strength of relationship of PvuII and XbaI in ESR1 and RsaI and AluI in ESR2 with male infertility, we conducted a meta-analysis of 12 eligible studies with odds ratio (OR) and its corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI).

Results

Overall, ESR1 PvuII and ESR2 RsaI polymorphisms were significantly associated with male infertility risk. The subgroup analyses by ethnicities demonstrated that in Asians, ESR1 PvuII, XbaI and ESR2 RsaI polymorphisms were significantly associated with a decreased infertility risk, while in Caucasians both ESR1 PvuII and ESR2 RsaI polymorphisms increased the susceptibility to male infertility. As for ESR2 AluI polymorphism, no significant association was detected in either overall analysis or subgroup analyses by ethnicities/genotyping methods.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggested that polymorphisms in the genes of ERs (ESR1 and ESR2) may have differential roles in the predisposition to male infertility according to the different ethnic backgrounds. Further well-designed and unbiased studies with larger sample size and diverse ethnic backgrounds should be conducted to verify our findings

Keywords: Estrogen receptor, Polymorphism, Male infertility, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Infertility is a major health problem affecting one-sixth of couples worldwide, whose cause is shared equally between male and female partners [1, 2]. Despite the consistent advance in the diagnostic workup of male infertility, the etiology and pathogenesis in about 30 % of cases are yet unknown, and their conditions are considered as idiopathic infertility [3]. Genetic abnormalities have been identified as one of the major contributing factors of male infertility [4].

Although estrogens have been conventionally regarded as female steroid hormones, their profound effects on male productive systems have been widely investigated and well documented [5]. In males, the estrogens are synthesized from testosterone through the action of aromatase cytochrome P450 in testes [6], and the concentration of estrogens in semen is higher than that in serum of women [7]. However, the role of estrogens on male infertility is still a matter of controversy. On one hand, estrogen deficiency can lead to reduced sperm production and sperm motility in humans [8]; on the other hand, estrogen excess during the adulthood can deteriorate sperm production and maturation [9].

The physiological responses to estrogens are mediated by estrogen receptors (ERs), which consist of three subtypes: ERα, ERβ and ERγ [10]. Of these three isoforms, ERα and ERβ have been well investigated, while ERγ is an emerging ER similar to ERβ, which was detected in various cellular models, including human spermatozoa [11]. ERα is a 595 amino acid protein encoded by ESR1 which is located on chromosome 6q25 [12, 13], while ERβ is a 530 amino acid protein encoded by ESR2 on chromosome 14q23-24 with a total size of 40 kb [14, 15]. Both receptors are expressed in human testicular germ cells at different stages of spermatogenesis [16], and exert important functions on male reproductive capability via the interaction with estrogens [5].

Genetic screening for ESR1 and ESR2 gene locus has demonstrated several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). For ESR1, the two most studied SNPs are PvuII (397T>C, rs2234693) and XbaI (351G>A, rs9340799), which were located in intron 1 and separated by 46 bp. The XbaI polymorphism is caused by a A-to-G transition at position +397, whereas the PvuII polymorphism is resulted from a T-to-C transition upstream of the XbaI polymorphic site [17]. As for ESR2, two silent G-to-A SNPs, RsaI (1082G>A, rs1256049) and AluI (1730G>A, rs4986938), have been widely investigated [18].

Since the first study reported by Kukuvitis and colleagues on the association between polymorphisms in the genes of ERs (ESR1 and ESR2) and risk of male infertility [19], many similar investigations in different ethnicities have been conducted [20–34]; however, the results of the published studies are inconclusive and even controversial. Thus, we conduct this meta-analysis to explore the exact association of the four common SNPs (PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, and AluI) in ESR1 and ESR2 with male infertility.

Materials and methods

Identification of eligible studies

This meta-analysis was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [35]. A comprehensive search of PUBMED and EMBASE was performed until December 1, 2013 to identify all eligible studies examining the association of the four common SNPs (PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, and AluI) in ERs with male infertility risk. No restrictions were placed on language, and only published studies with full-text articles were included. To search and include as many related studies as possible, we used different combinations of the following medical subject headings and key words: estrogen receptors, ESR1, or ESR2; polymorphism or variant; male infertility or spermatogenic failure. Furthermore, the reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles were manually screened for additional studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies identified from the above mentioned databases (PUBMED and EMBASE) were screened by two independent authors (Yu-Zheng Ge and Lu-Wei Xu) according to the following predesigned inclusion criteria: 1) case–control design; 2) evaluating the correlation of the four SNPs (PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, and AluI) with male infertility risk; 3) providing sufficient data to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and its corresponding 95 % confidence interval (CI). When several studies with overlapping data were eligible, those with smaller sample size or less reliability were excluded. Furthermore, studies without detailed information were excluded, after the efforts to extract data from the original paper or contact the corresponding authors failed.

Data extraction

All data from eligible studies were extracted by two reviewers (Yu-Zheng Ge and Zheng Xu) independently and in duplicate according to the predesigned data-collection form. The following information was extracted: last name of first author, publication year, country of origin, ethnicity, genotyping method, case definition and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). When HWE was not reported in controls, an online program (http://ihg.gsf.de/cgi-bin/hw/hwa1.pl) was applied to test the HWE by χ2 test for goodness of fit [36]. Discrepancies occurring during the process of studies selection and data extraction were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (Wen-Cheng Li), and consensus on each item was achieved at last.

Statistical analysis

The strength of association between the four polymorphisms in ERs and male infertility risk was measured by OR with its corresponding 95 % CI. The pooled ORs were calculated for the following five genetic models (1. Allelic model: A allele vs. a allele; 2. homozygote comparison: AA vs. aa; 3. heterozygote comparison: Aa vs. aa; 4. dominant model: AA + Aa vs. aa; and 5. recessive model: AA vs. Aa + aa. A: variant allele, a: wild allele, and allele A, T, G and G were considered as wild alleles for PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, and AluI, respectively). Stratified analyses were also conducted based on ethnicities and genotyping methods. The statistical significance of the pooled OR was assessed with the Z test and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Chi-square based Q test was conducted to measure the heterogeneity between eligible studies, and the existence of heterogeneity was considered significant if P < 0.10 [37]. When the between-study heterogeneity was absent, a fixed-effect model (Mantel-Haenszel method) was used to pool the data from different studies [38]; otherwise, a random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird method) was applied [39]. Sensitivity analyses were performed to identify each individual study’s effect on pooled results and test the reliability of results by deleting a single study each time [40]. To determine the presence of publication bias, Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s linear regression test were conducted, and P < 0.05 was considered significant [41, 42].

All statistical tests for this meta-analysis were performed with STATA software (version 10.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) and Review Manager (version 5.0; Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

Results

Characteristics of eligible studies

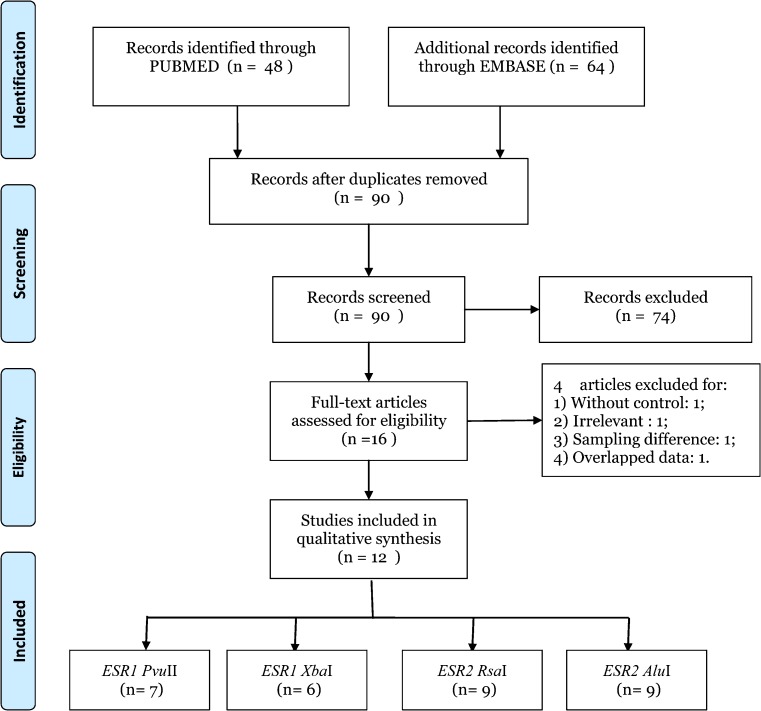

Records identified from the databases were primarily screened by titles and abstracts, and 16 full-text articles were retrieved for further assessment of the eligibility. Among those studies, four were excluded for: 1) without control [20]; 2) not targeted SNPs [24]; 3) data overlapped with others [25] and 4) subjects recruited from childhood cancer survivors [30]. After all, a total of 12 eligible articles were included in this meta-analysis, and the detailed screening process was shown in Fig. 1, which was modified according to the PRISMA Statement [35]. Among these 12 eligible studies, 7, 6, 9, and 9 studies were pooled for the analysis of PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, and AluI polymorphisms, respectively. As for ethnicities, four were studies of Caucasians [19, 21, 22, 28, 34], six studies were of Asians [23, 26, 27, 29, 32, 33], and one studies of mixed ethnicity [31]. To determine the SNPs, two different genotyping methods such as RFLP-PCR [19, 21–23, 26, 29, 33, 34] and TaqMan PCR [27, 28, 31, 32] were applied (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for study selection. Description: a total of 12 studies were included in this meta-analysis and systematic review after a comprehensive study selection

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Genotyping method | Investigated SNPs | Case definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kukuvitis | 2002 | Greece | Caucasian | RFLP-PCR | PvuII, XbaI | Oligospermia or azoospermia |

| Aschim | 2005 | Sweden | Caucasian | RFLP-PCR | RsaI, AluI | Oligozoospermia or azoospermia |

| Galan | 2005 | Spain | Caucasian | RFLP-PCR | PvuII, AluI | Oligozoospermia or azoospermia |

| Omrani | 2006 | Iran | Asian | RFLP-PCR | RsaI, AluI | Azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia |

| Khattri | 2009 | India | Asian | RFLP-PCR | RsaI, AluI | Azoospermia, oligoasthenozoospermia or oligoasthenoteratozoospermia |

| Su | 2010 | China | Asian | TaqMan PCR | RsaI, AluI | Oligozoospermia or azoospermia |

| Lazaros | 2010 | Greece | Caucasian | TaqMan PCR | PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, AluI | Oligospermia |

| Safarinejad | 2010 | Iran | Asian | RFLP-PCR | PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, AluI | Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia |

| Bianco | 2011 | Brazil | Mixed | TaqMan PCR | PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, AluI | Azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia |

| Ogata | 2012 | Japan | Asian | TaqMan PCR | RsaI | Azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia |

| Zalata | 2013 | Egypt | Caucasian | RFLP-PCR | PvuII, XbaI | Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia |

| Meng | 2013 | China | Asian | RFLP-PCR | PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, AluI | Oligozoospermia or azoospermia |

SNP single nucleotide polymorphism, PCR polymerase chain reaction, RFLP restriction fragment length polymorphism

Quantitative data synthesis

Association of ESR1 PvuII polymorphism with male infertility

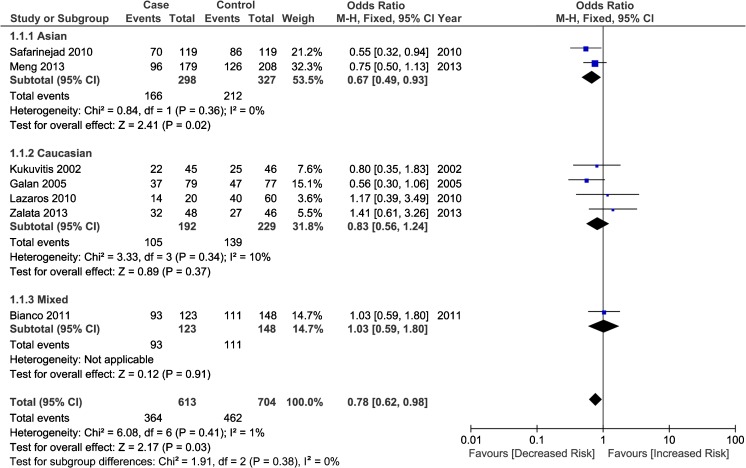

A total of seven studies with 840 cases and 936 controls were included to examine the association between ESR1 PvuII polymorphism and male infertility risk, including three Caucasian studies [19, 22, 28, 34], 2 Asian studies [29, 33], and 1 study with mixed population [31]. Overall, the PvuII polymorphism in ESR1 was associated with a significantly decreased risk of male infertility in heterozygote comparison (CT vs. TT, OR = 0.78, 95 % CI: 0.62–0.98, P heterogeneity = 0.415; Fig. 2). Further subgroup analyses based on ethnicities and genotyping methods demonstrated that ESR1 PvuII polymorphism was significantly associated with an decreased risk in Asian males (C allele vs. T allele, OR = 0.78, 95 % CI: 0.64–0.96; CC vs. TT, OR = 0.61, 95 % CI: 0.40–0.93; CT vs. TT, OR = 0.67, 95 % CI: 0.49–0.93; CC + CT vs. TT, OR = 0.66, 95 % CI: 0.49–0.90) and an increased risk in Caucasians (CC vs. CT + TT: OR = 1.52, 95 % CI: 1.05–2.22). With regard to the subgroup analysis by genotyping methods, a significant association was detected in RFLP-PCR genotyping method under both heterozygote comparison (CT vs. TT: OR = 0.71, 95 % CI: 0.55–0.92) and dominant model (CC + CT vs. TT, OR = 0.77, 95 % CI: 0.61–0.98), the detailed results was presented in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for the relationship of ESR1 PvuII polymorphism with male infertility (CT vs. TT) stratified by ethnicity. For each study, the estimate of OR and its 95 % CI is plotted with a box and a horizontal line. Filled diamond pooled OR and its 95%CI

Table 2.

meta-analysis results of the association of ESR1 PvuII polymorphism with male infertility

| Category | Numa | C allele vs. T allele | CC vs. TT | CT vs. TT | CC + CT vs. TT | CC vs. CT + TT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95%CI) | Pb | OR(95%CI) | Pb | OR(95%CI) | Pb | OR(95%CI) | Pb | OR(95%CI) | Pb | ||

| Total | 7 | 1.01(0.82,1.24) | 0.051 | 1.01(0.69,1.48) | 0.089 | 0.78(0.62,0.98) c | 0.415 | 0.83(0.67,1.03) | 0.177 | 1.11(0.90,1.38) | 0.217 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||

| Asian | 2 | 0.78(0.64,0.96) c | 0.681 | 0.61(0.40,0.93) c | 0.670 | 0.67(0.49,0.93) c | 0.358 | 0.66(0.49,0.90) c | 0.593 | 0.83(0.58,1.18) | 0.257 |

| Caucasian | 4 | 1.21(0.90,1.62) | 0.208 | 1.42(0.90,2.23) | 0.381 | 0.83(0.56,1.24) | 0.343 | 1.02(0.71,1.46) | 0.227 | 1.52(1.05,2.22) c | 0.628 |

| Mixed | 1 | 1.08(0.82,1.43) | – | 1.61(0.64,2.10) | – | 1.03(0.59,1.80) | – | 1.08(0.64,1.83) | – | 1.13(0.75,1.72) | – |

| Genotyping method | |||||||||||

| RFLP-PCR | 5 | 1.00(0.75,1.32) | 0.022 | 0.99(0.59,1.66) | 0.037 | 0.71(0.55,0.92) c | 0.392 | 0.77(0.61,0.98) c | 0.127 | 1.11(0.85,1.45) | 0.082 |

| TaqMan | 2 | 1.08(0.84,1.40) | 0.974 | 1.17(0.69,1.98) | 0.961 | 1.06(0.65,1.74) | 0.847 | 1.10(0.67,1.76) | 0.883 | 1.12(0.77,1.64) | 0.926 |

aNum, number of eligible studies

bP value of Q test for heterogeneity test

cStatistically significant results (in bold)

Association of ESR1 XbaI polymorphism with male infertility

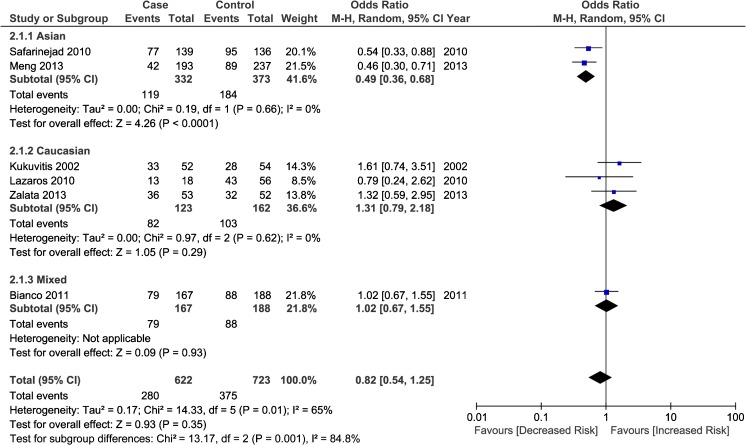

Six studies including 736 infertile men and 841 healthy fertile controls were identified for evaluating the relationship between XbaI polymorphism in ESR1 and male infertility. Overall, as shown in Table 3, no significant association was detected between ESR1 XbaI polymorphism and infertility susceptibility in males. Further stratification analysis by ethnicities demonstrated a significant association in Asian population in allelic model (G allele vs. A allele, OR = 0.67, 95 % CI: 0.54–0.85, P heterogeneity = 0.375), heterozygote comparison (AG vs. AA, OR = 0.49, 95 % CI: 0.36–0.68, P heterogeneity = 0.660; Fig. 3) and dominant model (GG + GA vs. AA, OR = 0.52, 95 % CI: 0.38–0.71, P heterogeneity = 0.768), while in Caucasian population, no significant association was detected. In the subgroup analysis based on genotyping method, no significant association was found in all genetic models.

Table 3.

meta-analysis results of the association of ESR1 XbaI polymorphism with male infertility

| Category | Numa | G allele vs. A allele | GG vs. AA | GA vs. AA | GG + GA vs. AA | GG vs. GA + AA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95%CI) | Pb | OR(95%CI) | Pb | OR(95%CI) | Pb | OR(95%CI) | Pb | OR(95%CI) | Pb | ||

| Total | 6 | 0.88(0.65,1.20) | 0.002 | 0.87(0.50,1.50) | 0.026 | 0.82(0.54,1.25) | 0.014 | 0.74(0.50,1.10) | 0.017 | 0.92(0.53,1.60) | 0.003 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||

| Asian | 2 | 0.67(0.54,0.85) c | 0.375 | 0.64(0.38,1.07) | 0.714 | 0.49(0.36,0.68) c | 0.660 | 0.52(0.38,0.71) c | 0.768 | 0.59(0.30,1.16) | 0.177 |

| Caucasian | 3 | 1.10(0.55,2.19) | 0.004 | 1.20(0.30,1.48) | 0.005 | 0.85(0.48,1.50) | 0.317 | 0.94(0.39,2.24) | 0.053 | 1.10(0.67,1.83) | 0.060 |

| Mixed | 1 | 0.93(0.70,1.25) | – | 0.81(0.43,1.54) | – | 1.02(0.67,1.55) | – | 0.97(0.66,1.44) | – | 0.50(0.27,0.92) c | – |

| Genotyping method | |||||||||||

| RFLP-PCR | 4 | 0.85(0.54,1.35) | 0.001 | 0.90(0.38,2.10) | 0.005 | 0.79(0.44,1.40) | 0.010 | 0.67(0.40,1.14) | 0.019 | 0.98(0.47,2.07) | 0.004 |

| TaqMan | 2 | 0.95(0.73,1.24) | 0.755 | 0.85(0.48,1.50) | 0.785 | 0.99(0.67,1.47) | 0.688 | 0.96(0.66,1.39) | 0.854 | 0.83(0.28,2.48) | 0.040 |

aNum, number of eligible studies

bP value of Q test for heterogeneity test

cStatistically significant results (in bold)

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for the association between ESR1 XbaI polymorphism with male infertility (AG vs. AA) stratified by ethnicity. For each study, the estimate of OR and its 95 % CI is plotted with a box and a horizontal line. Filled diamond pooled OR and its 95%CI

Association of ESR2 RsaI polymorphism with male infertility

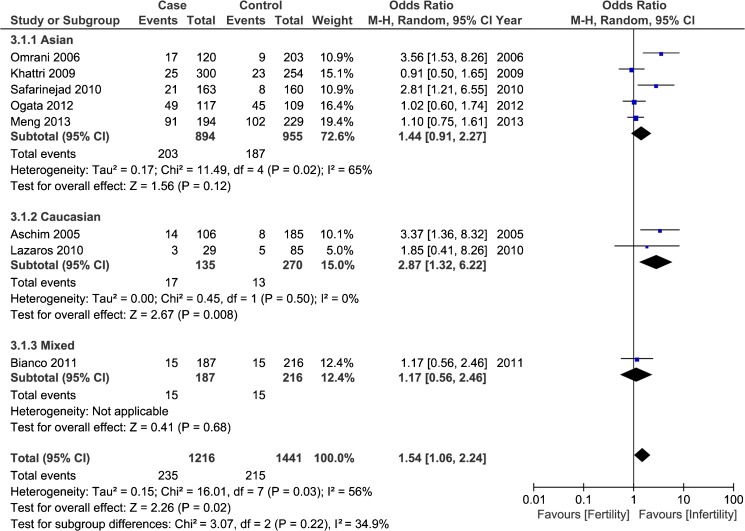

Data from nine case–control studies involving 1,418 infertile cases and 1,601 healthy fertile controls were pooled together to explore the potential association between ESR2 RsaI polymorphism with male infertility. The overall results indicated that variant A allele of ESR2 RsaI polymorphism was associated with a lower risk for male infertility in homozygote comparison (AA vs. GG, OR = 0.56, 95 % CI: 0.32–0.98, P heterogeneity = 0.964) and recessive model (AA vs. AG + GG, OR = 0.54, 95 % CI: 0.31–0.93, P heterogeneity = 0.954), while an increased risk in heterozygote comparison (AG vs. GG, OR = 1.54, 95 % CI: 1.06–2.24, P heterogeneity = 0.025; Fig. 4). The further subgroup analysis based on ethnicities demonstrated that ESR2 RsaI polymorphism was significantly associated with a decreased infertility risk for Asian population in homozygote comparison (AA vs. GG, OR = 0.56, 95 % CI: 0.31–0.98, P heterogeneity = 0.914) and recessive model (AA vs. AG + GG, OR = 0.54, 95 % CI: 0.31–0.94, P heterogeneity = 0.895) and an increased risk for Caucasian men in Allelic model (A allele vs. G allele, OR = 2.35, 95 % CI: 1.14–4.84, P heterogeneity = 0.682), heterozygote comparison (AG vs. GG, OR = 2.87, 95 % CI: 1.32–6.22, P heterogeneity = 0.501) and dominant model(AA + AG vs. GG, OR = 2.65, 95 % CI: 1.24–5.63, P heterogeneity = 0.585). As for the subgroup analysis by genotyping methods, the results indicated that the examined SNP was associated with a decreased risk with RFLP-PCR genotyping method in homozygote comparison (AA vs. GG, OR = 0.49, 95 % CI: 0.25–0.97, P heterogeneity = 0.973) and recessive model (AA vs. AG + GG, OR = 0.47, 95 % CI: 0.24–0.91, P heterogeneity = 0.972) while a higher risk in heterozygote comparison (AG vs. GG, OR = 1.85, 95 % CI: 1.05–3.27, P heterogeneity = 0.006) (Table 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for the correlation of ESR2 RsaI polymorphism with male infertility (AG vs. GG) stratified by ethnicity. For each study, the estimate of OR and its 95 % CI is plotted with a box and a horizontal line. Filled diamond pooled OR and its 95%CI

Table 4.

meta-analysis results of the association of ESR2 RsaI polymorphism with male infertility

| Category | A allele vs. G allele | AA vs. GG | AG vs. GG | AA + AG vs. GG | AA vs. AG + GG | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | |

| Total | 9 | 1.44(0.99,2.07) | <0.001 | 6 | 0.56(0.32,0.98) c | 0.964 | 8 | 1.54(1.06,2.24) c | 0.025 | 8 | 1.39(0.99,1.95) | 0.044 | 6 | 0.54(0.31,0.93) c | 0.954 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||

| Asian | 6 | 1.37(0.87,2.14) | <0.001 | 5 | 0.56(0.31,0.98) c | 0.914 | 5 | 1.44(0.91,2.27) | 0.022 | 5 | 1.27(0.85,1.90) | 0.043 | 5 | 0.54(0.31,0.94) c | 0.895 |

| Caucasian | 2 | 2.35(1.14,4.84) c | 0.682 | 1 | 0.64(0.03,15.9) | – | 2 | 2.87(1.32,6.22) c | 0.501 | 2 | 2.65(1.24,5.63) c | 0.585 | 1 | 0.58(0.02,14.4) | – |

| Mixed | 1 | 1.16(0.56,2.41) | – | 0 | – | – | 1 | 1.17(0.56,2.46) | – | 1 | 1.17(0.56,2.46) | – | 0 | – | – |

| Genotyping method | |||||||||||||||

| RFLP-PCR | 6 | 1.61(0.97,2.66) | <0.001 | 5 | 0.49(0.25,0.97) c | 0.973 | 5 | 1.85(1.05,3.27) c | 0.006 | 5 | 1.61(0.96,2.70) | 0.011 | 5 | 0.47(0.24,0.91) c | 0.972 |

| TaqMan | 3 | 1.02(0.72,1.43) | 0.644 | 1 | 0.75(0.28,2.03) | – | 3 | 1.12(0.74,1.69) | 0.760 | 3 | 1.08(0.72,1.61) | 0.707 | 1 | 0.75(0.31,1.96) | – |

aN, number of eligible studies

b P value of Q test for heterogeneity test

cStatistically significant results (in bold)

Association of ESR2 AluI polymorphism with male infertility

A total of nine eligible studies with 1,397 infertile cases and 1,577 healthy fertile controls were included for the analysis. Of these nine studies, six were conducted in Asian population [23, 26, 27, 29, 33], three in Caucasians [21, 22, 28], and one in the mixed population [31]. Of note, the study reported by Su et al. only presented allelic distribution of two groups [27]; therefore, it was merely included in the allelic model. Overall, as presented in Table 5, no significant association was detected about the association of studied SNP with male infertility risk. Stratified analyses based on ethnicities and genotyping methods also failed to detect the significant association between ESR2 AluI polymorphism and male infertility risk.

Table 5.

meta-analysis results of the association of ESR2 AluI polymorphism with male infertility

| Category | A allele vs. G allele | AA vs. GG | AG vs. GG | AA + AG vs. GG | AA vs. AG + GG | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | Na | OR(95%CI) | Pb | |

| Total | 9 | 0.99(0.89,1.12) | 0.620 | 8 | 1.03(0.79,1.34) | 0.743 | 8 | 1.01(0.80,1.27) | 0.095 | 8 | 1.19(0.84,1.69) | <0.001 | 8 | 1.06(0.83,1.36) | 0.195 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||

| Asian | 5 | 0.99(0.86,1.15) | 0.250 | 4 | 0.94(0.65,1.35) | 0.760 | 4 | 1.22(0.99,1.52) | 0.601 | 4 | 1.66(0.93,2.94) | <0.001 | 4 | 0.84(0.59,1.20) | 0.752 |

| Caucasian | 3 | 0.93(0.73,1.19) | 0.958 | 3 | 0.88(0.52,1.48) | 0.783 | 3 | 0.89(0.61,1.28) | 0.593 | 3 | 0.88(0.63,1.25) | 0.801 | 3 | 0.95(0.60,1.52) | 0.536 |

| Mixed | 1 | 1.10(0.83,1.46) | – | 1 | 1.55(0.89,2.73) | – | 1 | 0.59(0.38,0.91) c | – | 1 | 0.80(0.54,1.18) | – | 1 | 2.01(1.19,3.38) c | – |

| Genotyping method | |||||||||||||||

| RFLP-PCR | 7 | 0.98(0.86,1.12) | 0.481 | 6 | 0.93(0.68,1.27) | 0.903 | 6 | 1.14(0.94,1.38) | 0.447 | 6 | 1.34(0.88,2.04) | <0.001 | 6 | 0.88(0.66,1.19) | 0.759 |

| TaqMan | 2 | 1.05(0.81,1.36) | 0.472 | 2 | 1.35(0.82,2.23) | 0.266 | 2 | 0.62(0.41,0.93n c | 0.598 | 2 | 0.79(0.55,1.15) | 0.982 | 2 | 1.61(0.83,1.36) | 0.112 |

aN, number of eligible studies

bP value of Q test for heterogeneity test

cStatistically significant results (in bold)

Heterogeneity test and sensitivity analysis

During the meta-analysis, the significant between-study heterogeneity was observed (Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5). To explore the source of heterogeneity, stratification analyses by ethnicities and genotyping methods were conducted. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were performed to explore the influence of each individual study on the overall results by deleting one single study each time from the pooled analysis. The results indicated the three studies contributed to the main source of between-study heterogeneity [33, 23, 34]. In addition, no single study was found to have the substantial power to affect the pooled ORs significantly (Data not shown).

Publication bias

To assess the publication bias of the currently available literature, both Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were performed. The shapes of the funnel plots did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry in all comparison models (data not shown). Then, the Egger’s test was used to provide statistical evidence for funnel plot symmetry. The results also did not show any evidence of publication bias (Table 6).

Table 6.

Statistical analyses of publication bias for estrogen receptors polymorphisms

| Category | Allelic Model | Homozygote Comparison | Heterozygote Comparison | Dominant Model | Recessive Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR1 PvuII | C vs. T allele | CC vs. TT | CT vs, TT | CC + CT vs. TT | CC vs. CT + TT |

| Begg’s test | 0.230 | 0.133 | 0.230 | 0.133 | 0.368 |

| Egger’s test | 0.134 | 0.126 | 0.344 | 0.117 | 0.311 |

| ESR1 XbaI | G vs. A allele | GG vs. AA | GA vs. AA | GG + GA vs. AA | GG vs. GA + AA |

| Begg’s test | 1.000 | 0.707 | 1.000 | 0.707 | 0.452 |

| Egger’s test | 0.423 | 0.382 | 0.766 | 0.641 | 0.323 |

| ESR2 RsaI | A vs. G allele | AA vs. GG | AG vs. GG | AA + AG vs. GG | AA vs. AG + GG |

| Begg’s test | 0.118 | 0.707 | 0.108 | 0.063 | 0.707 |

| Egger’s test | 0.291 | 0.413 | 0.066 | 0.056 | 0.387 |

| ESR2 AluI | A vs. G allele | AA vs. GG | AG vs. GG | AA + AG vs. GG | AA vs. AG + GG |

| Begg’s test | 0.175 | 0.174 | 0.266 | 1.000 | 0.711 |

| Egger’s test | 0.168 | 0.078 | 0.551 | 0.578 | 0.119 |

Discussion

Male infertility is a major global health problem, which is contributory in approximately 50 % of couples unable to achieve pregnancy after regular intercourses over 1 year [1, 26]. Many efforts have been made to explore the potential biomarkers with clear-cut diagnostic and prognostic values, including the SNPs in the genes of ERs (ESR1 and ESR2). However, due to the relative small sample size, no clear consensus has reached on the relationship of four common SNPs (PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, and AluI) in ERs with male infertility risk; therefore this meta-analysis was conducted. In the present study, we provide evidence that two well-characterized SNPs (PvuII and XbaI) of ESR1 were associated with a significantly decreased risk for male infertility, especially in Asian population with RFLP-PCR genotyping method; in case of ESR2 RsaI polymorphism, diverse results were yielded that it was significantly with a lower risk at homozygote and recessive level while an increased risk at heterozygote level; as for ESR2 RsaI polymorphism, no significant association with male infertility risk was detected.

Over the past few decades, a growing body of evidence has implied that estrogens play a vital role on male reproductive capability [5]. The effects of estrogens are mediated by at least two ER isoforms (ERα and ERβ), which are expressed in human germ cells of various stages [16, 6]. The importance of ERs in male reproduction has been elucidated by both genetically modified mice without functional ERα and/or ERβ [43, 16] and the phenotypes of men with ERα and/or ERβ gene mutations [44, 33]. As one form of the most common genetic abnormalities, the SNPs in ESR1 and ESR2 and their implications in male infertility have been investigated widely.

Since the first two studies addressing the relationship of ESR1 and ESR2 polymorphisms with male infertility were reported [19, 21], a number of similar studies were conducted in different ethnicities with inconclusive results. After pooling all data from seven eligible studies, the results demonstrated that ESR1 PvuII variant C allele carriers were significant associated with a decreased male infertility risk (CT vs. TT, OR = 0.78, 95 % CI: 0.62–0.98). Further subgroup analyses based on ethnicities demonstrated the differential association of ESR1 PvuII polymorphism with a decreased risk in Asian population and an increased risk in Caucasian population. In case of ESR1 XbaI polymorphism, the variant G allele was significantly with a lower risk for male infertility in Asian population rather than Caucasian men. With regard to the correlation of ESR2 RsaI polymorphism with male infertility, differential even controversial results were presented. Variant A allele was associated with a lower risk in homozygote comparison (AA vs. GG, OR = 0.56, 95 % CI: 0.32–0.98) and recessive model (AA vs. AG + GG, OR = 0.54, 95 % CI: 0.31–0.93), while an increased risk in heterozygote comparison (AG vs. GG, OR = 1.54, 95 % CI: 1.06–2.24). The subsequent subgroup analysis by ethnicities demonstrated the examined SNP decreased spermatogenic failure risk in Asian males (AA vs. GG, OR = 0.56, 95 % CI: 0.31–0.98; AA vs. AG + GG, OR = 0.54, 95 % CI: 0.31–0.94) while increased the risk in Caucasian men (A allele vs. G allele, OR = 2.35, 95 % CI: 1.14–4.84; AG vs. GG, OR = 2.87, 95 % CI: 1.32–6.22 and AA + AG vs. GG, OR = 2.65, 95 % CI: 1.24–5.63). The different results in two ethnic groups contributed to the differential results in various comparison models of overall analysis. As for ESR2 AluI polymorphism, no significant association was detected in either overall analysis or subgroup analyses by ethnicities and genotyping methods.

The differential or even controversial results about the association between the three SNPs (PvuII, XbaI and RsaI) may be attributed to the following reasons: 1) the inherent genetic difference between Asians and Caucasians, and the similar result was demonstrated in a meta-analysis addressing the association between ESR1 polymorphisms and endometrial cancer risk [45]; 2) the difference of sample size in two populations was so obvious as the number of Caucasian studies included in the analysis for the four SNPs ranges from one to three; 3) the difference of lifestyles between Asians and Caucasians, as the phytoestrogens intake and exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors (EEDs) differs in two populations, which can help contribute to male infertility to some degree [5, 32, 46]; 4) the polygenic nature of male infertility is yet unclear, neither is the underlying genetic mechanism which means that additional loci might be involved in the development of the spermatogenic phenotype, either within or near the ERs gene or the other core genes involved in estrogenic and estrogen-related pathways [29, 33].

Although the meta-analysis is robust, several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the results. First, this study was conducted at the study level without access to more detailed information such as age, family history, and life-style (such as phytoestrogen intake and exposure to EEDs during the neonatal life), which may influence the results. Second, the between-study heterogeneity was significantly observed during the meta-analysis, even the sensitivity analysis confirmed no substantial impact of a single study on the overall results. Third, the number of studies included to assess the correlation of ERs polymorphisms with male infertility in Caucasian population and with TaqMan PCR genotyping method was relatively small. Last but not least, the meta-analysis is retrospective due to the methodological limitations. In order to minimize the bias, we followed the protocol designed before initiating the study, and the process of studies selection, data extraction and analyses was performed by two independent authors, discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third author. Nevertheless, the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

In summary, this meta-analysis suggested that polymorphisms in ERs (ESR1 and ESR2) may have differential roles in the predisposition to male infertility due to the different ethnic backgrounds. Additionally, further well-designed and unbiased studies with larger sample size, different genotyping methods, and diverse ethnic backgrounds (especially in Caucasians and Africans) should be conducted to verify our findings.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This project was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81070597, 81370853), Science and Education Development Program of the Jiangsu Province Health Board (LJ201107), Six Talent Peaks of the Jiangsu Province Health Bureau (2011-WS-093), and Research and Innovation Program for Graduates of Jiangsu Province (CXZZ13_0583). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Capsule

The differential association of polymorphisms in estrogen receptors (PvuII, XbaI, RsaI, and AluI) with male infertility was summarized.

Yu-Zheng Ge and Lu-Wei Xu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Maduro MR, Lamb DJ. Understanding new genetics of male infertility. J Urol. 2002;168(5):2197–2205. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1506–1512. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasqualotto FF, Pasqualotto EB, Sobreiro BP, Hallak J, Medeiros F, Lucon AM. Clinical diagnosis in men undergoing infertility investigation in a university hospital. Urol Int. 2006;76(2):122–125. doi: 10.1159/000090873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovac JR, Pastuszak AW, Lamb DJ. The use of genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics in identifying biomarkers of male infertility. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(4):998–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giwercman A. Estrogens and phytoestrogens in male infertility. Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21(6):519–526. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32834b7e7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carreau S, Lambard S, Delalande C, Denis-Galeraud I, Bilinska B, Bourguiba S. Aromatase expression and role of estrogens in male gonad: a review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hess RA, Bunick D, Lee KH, Bahr J, Taylor JA, Korach KS, et al. A role for oestrogens in the male reproductive system. Nature. 1997;390(6659):509–512. doi: 10.1038/37352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess RA. Estrogen in the adult male reproductive tract: a review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:52. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atanassova N, McKinnell C, Turner KJ, Walker M, Fisher JS, Morley M, et al. Comparative effects of neonatal exposure of male rats to potent and weak (environmental) estrogens on spermatogenesis at puberty and the relationship to adult testis size and fertility: evidence for stimulatory effects of low estrogen levels. Endocrinology. 2000;141(10):3898–3907. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawkins MB, Thornton JW, Crews D, Skipper JK, Dotte A, Thomas P. Identification of a third distinct estrogen receptor and reclassification of estrogen receptors in teleosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(20):10751–10756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luconi M, Forti G, Baldi E. Genomic and nongenomic effects of estrogens: molecular mechanisms of action and clinical implications for male reproduction. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;80(4–5):369–381. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(02)00041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menasce LP, White GR, Harrison CJ, Boyle JM. Localization of the estrogen receptor locus (ESR) to chromosome 6q25.1 by FISH and a simple post-FISH banding technique. Genomics. 1993;17(1):263–265. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponglikitmongkol M, Green S, Chambon P. Genomic organization of the human oestrogen receptor gene. EMBO J. 1988;7(11):3385–3388. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogawa S, Inoue S, Watanabe T, Hiroi H, Orimo A, Hosoi T, et al. The complete primary structure of human estrogen receptor beta (hER beta) and its heterodimerization with ER alpha in vivo and in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243(1):122–126. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K, Lagercrantz S, Lagercrantz J, Fried G, et al. Human estrogen receptor beta-gene structure, chromosomal localization, and expression pattern. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(12):4258–4265. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Donnell L, Robertson KM, Jones ME, Simpson ER. Estrogen and spermatogenesis. Endocr Rev. 2001;22(3):289–318. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.3.0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shearman AM, Cupples LA, Demissie S, Peter I, Schmid CH, Karas RH, et al. Association between estrogen receptor alpha gene variation and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2003;290(17):2263–2270. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenkranz K, Hinney A, Ziegler A, Hermann H, Fichter M, Mayer H, et al. Systematic mutation screening of the estrogen receptor beta gene in probands of different weight extremes: identification of several genetic variants. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(12):4524–4527. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.12.5471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kukuvitis A, Georgiou I, Bouba I, Tsirka A, Giannouli CH, Yapijakis C, et al. Association of oestrogen receptor alpha polymorphisms and androgen receptor CAG trinucleotide repeats with male infertility: a study in 109 Greek infertile men. Int J Androl. 2002;25(3):149–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2002.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki Y, Sasagawa I, Itoh K, Ashida J, Muroya K, Ogata T. Estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphism is associated with idiopathic azoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(6):1341–1343. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04267-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aschim EL, Giwercman A, Stahl O, Eberhard J, Cwikiel M, Nordenskjold A, et al. The RsaI polymorphism in the estrogen receptor-beta gene is associated with male infertility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5343–5348. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galan JJ, Buch B, Cruz N, Segura A, Moron FJ, Bassas L, et al. Multilocus analyses of estrogen-related genes reveal involvement of the ESR1 gene in male infertility and the polygenic nature of the pathology. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(4):910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omrani MD, Samadzadae S, Farshid B, Jahandidae B, Yazdanpanah K. Is there any association between ER(beta) gene polymorphism and infertility in Iranian men? J Res Med Sci. 2006;11(1):48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galan JJ, Guarducci E, Nuti F, Gonzalez A, Ruiz M, Ruiz A, et al. Molecular analysis of estrogen receptor alpha gene AGATA haplotype and SNP12 in European populations: potential protective effect for cryptorchidism and lack of association with male infertility. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(2):444–449. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khattri A, Pandey RK, Gupta NJ, Chakravarty B, Deendayal M, Singh L, et al. CA repeat and RsaI polymorphisms in ERbeta gene are not associated with infertility in Indian men. Int J Androl. 2009;32(1):81–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khattri A, Pandey RK, Gupta NJ, Chakravarty B, Deenadayal M, Singh L, et al. Estrogen receptor beta gene mutations in Indian infertile men. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15(8):513–520. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su MT, Chen CH, Kuo PH, Hsu CC, Lee IW, Pan HA, et al. Polymorphisms of estrogen-related genes jointly confer susceptibility to human spermatogenic defect. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazaros LA, Xita NV, Kaponis AI, Zikopoulos KA, Plachouras NI, Georgiou IA. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta polymorphisms are associated with semen quality. J Androl. 2010;31(3):291–298. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.007542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. Association of polymorphisms in the estrogen receptors alpha, and beta (ESR1, ESR2) with the occurrence of male infertility and semen parameters. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;122(4):193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romerius P, Giwercman A, Moell C, Relander T, Cavallin-Stahl E, Wiebe T, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha single nucleotide polymorphism modifies the risk of azoospermia in childhood cancer survivors. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2011;21(5):263–269. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328343a132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bianco B, Peluso C, Gava MM, Ghirelli-Filho M, Lipay MV, Lipay MA, et al. Polymorphisms of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in idiopathic, infertile Brazilian men: a case–control study. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78(9):665–672. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogata T, Fukami M, Yoshida R, Nagata E, Fujisawa Y, Yoshida A, et al. Haplotype analysis of ESR2 in Japanese patients with spermatogenic failure. J Hum Genet. 2012;57(7):449–452. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng J, Mu X, Wang YM. Influence of the XbaI polymorphism in the estrogen receptor-alpha gene on human spermatogenic defects. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12(2):1808–1815. doi: 10.4238/2013.June.11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zalata A, Abdalla HA, El-Bayoumy Y, Mostafa T. Oestrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms relationship with semen variables in infertile men. Andrologia. 2013 doi: 10.1111/and.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ge YZ, Wu R, Jia RP, Liu H, Yu P, Zhao Y, et al. Association between interferon gamma +874T>a polymorphism and acute renal allograft rejection: evidence from published studies. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(10):6043–6051. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thakkinstian A, McElduff P, D’Este C, Duffy D, Attia J. A method for meta-analysis of molecular association studies. Stat Med. 2005;24(9):1291–1306. doi: 10.1002/sim.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Couse JF, Enmark E, Warner M, Mahler JF, et al. Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(26):15677–15682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinkevicius KW, Laine M, Lotan TL, Woloszyn K, Richburg JH, Greene GL. Estrogen-dependent and -independent estrogen receptor-alpha signaling separately regulate male fertility. Endocrinology. 2009;150(6):2898–2905. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Cui M, Zheng L. Genetic polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor-alpha gene and the risk of endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(8):911–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sikka SC, Wang R. Endocrine disruptors and estrogenic effects on male reproductive axis. Asian J Androl. 2008;10(1):134–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]