Abstract

The schwannomas are nervous tissue tumors. We report a case of schwannoma of oral tongue. Because schwannomas are quite rare in the oral cavity, they are often not immediately included in the differential diagnosis of oropharyngeal masses, causing delay in identification and treatment. The definitive diagnosis requires histopathologic examination.

Keywords: Schwannoma, Tongue, Schwann cells

Introduction

The schwannomas are nervous tissue tumors also known as neurilemomas or neurinomas. They are benign, slow growing, epineurium-encapsulated neoplasms arising from Schwann cells that comprise the myelin sheaths surrounding peripheral nerve [6, 21]. Extracranially, about 25% of all schwannomas are located in the head and neck, but only 1% shows an intraoral origin [21]. The most common intraoral sites are the tongue, followed by the palate, the floor of the mouth, the buccal mucosa, the gingiva, the lips, and the vestibular mucosa [9, 22]. The cyst may arise at any age, the peak incidence is between third and sixth decades. There is no sex predilection [11, 14, 17, 21]. Schwannomas remain asymptomatic unless they attain appreciable size. These tumors are usually solitary lesions but in unusual instance are multiple, or occur in the setting of von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis. In contrast to multiple neurofibromatosis, schwannomas almost never undergo malignant transformation [1, 3, 6, 18]. The treatment of choice is surgical excision of the tumor. Schwannomas do not show recurrence if completely excised [1]. We report a case of schwannoma of oral tongue.

Case Report

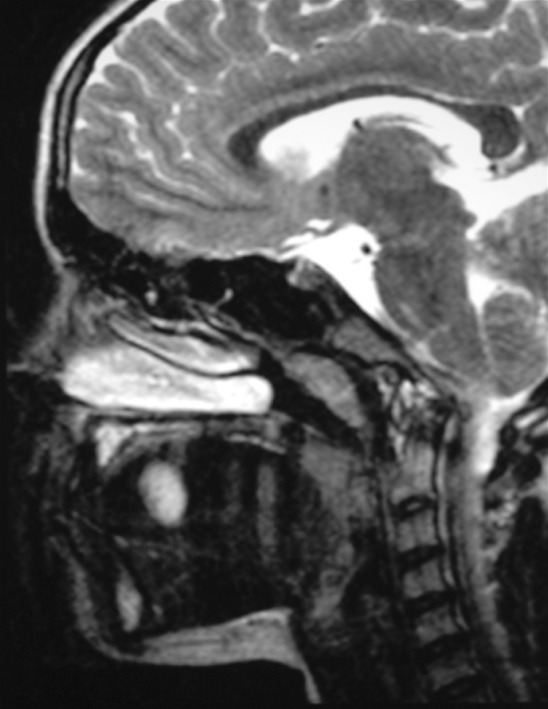

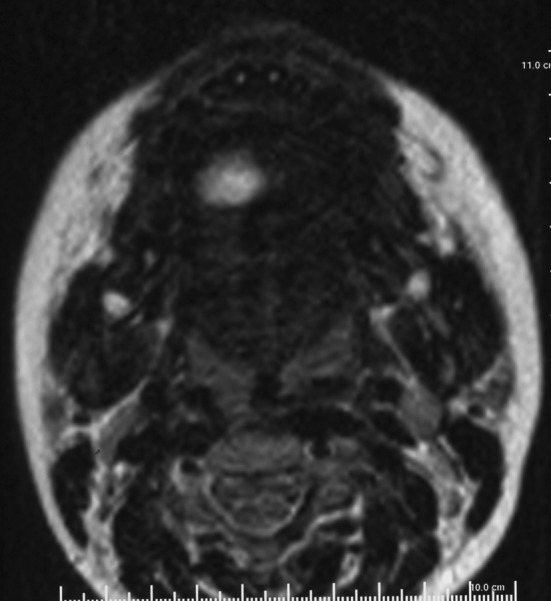

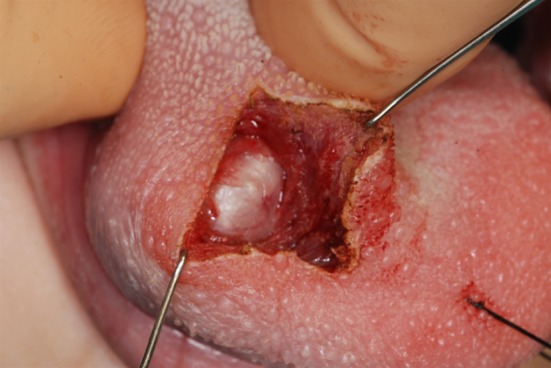

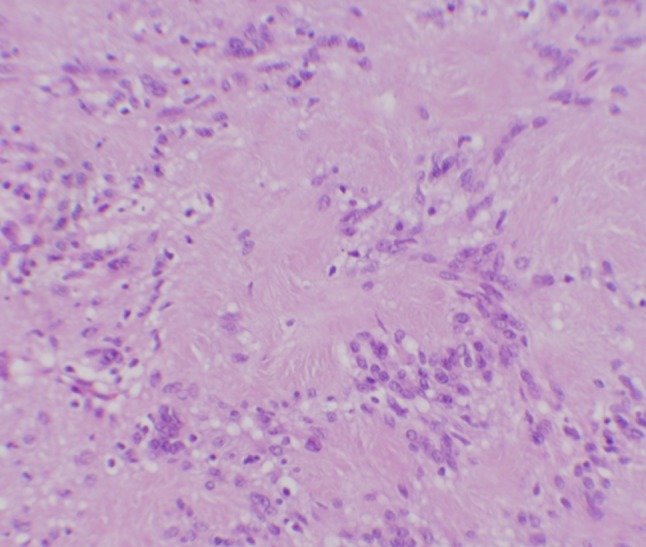

A 13-year-old woman presented to the department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University Hospital Infanta Cristina of Badajoz, for evaluation of a lesion on the right side of the tongue (ventral part) first noted 3 months earlier. Her past medical history was unremarkable. Noteworthy findings in the patient’s family history included bone marrow malignancy and a salivary gland tumor. Clinical examination revealed a 2 cm, nontender, nonulcerated mass on the right side of the tongue. The remainder of the oral examination was unremarkable and examination of the head and neck was otherwise normal. MR imaging demonstrated a mass with uniform isointensity relative to surrounding muscles on T1-weighted images without contrast enhancement, and on T2-weighted images, the signal intensity was markedly high (Figs. 1, 2). An excisional biopsy was done under general anesthesia. Grossly the mass was well encapsulated, measuring 2 cm in diameter, and had firm gray white cut surface (Figs. 3, 4). Tissue was sent for histopathological examination. Histologic sections showed a 0.3-cm, circumscribed submucosal nodule composed of spindle cells with thin wavy nuclei. Nuclear palisading and verocay bodies typical of a schwannoma were readily identifiable. A confirmatory S-100 immunoperoxidase stain was strongly positive. The diagnosis was schwannoma of the tongue. An associated nerve was not identified. The patient has not shown any recurrence in the follow up period of 1 year.

Fig. 1.

MR imaging demonstrated a mass with signal intensity on T2-weighted images, markedly high (sagital view)

Fig. 2.

MR imaging demonstrated a mass with signal intensity on T2-weighted images, markedly high (axial view)

Fig. 3.

The excisional biopsy on tongue was done under general anesthesia

Fig. 4.

The mass was well encapsulated, measuring 2 cm in diameter

Discussion

Schwannomas are infrequent, benign neoplasms that can arise from any cranial, peripheral, or autonomic nerve that contains Schwann cells. Schwann cells are neural crest-derived glial cells that are responsible for providing myelin insulation to peripheral nervous system axons. In the head and neck, two notable exceptions of nerves lacking Schwann cell encasement are the optic and olfactory nerve [22]. Schwannomas were first described by Verocay in 1908 [3, 6]. Shortly thereafter Stout recognized their schwannian derivation [1, 6, 11].

Embryologically, Schwann cells arise during the fourth week of development from a specialized population of ectomesenchymal cells of the neural crest, which then detach from the neural tube and migrate into the embryo. Schwann cells form a thin barrier around each extracranial nerve fiber and wrap larger fibers with an insulating membrane, myelin sheath, to enhance nerve conductance. As nerves exit the brain and spinal cord, there is a change between myelination by oligodendrocytes to myelination by Schwann cells. Schwannomas arise when proliferating Schwann cells form a tumor mass (unknown etiology) encompassing motor and sensory peripheral nerves. Only 50% of these tumors have a direct relation with a nerve [3, 17].

Most head and neck schwannomas present as a solitary, slowly enlarging, nontender, encapsulated mass, and usually asymptomatic. Depending on the location of the tumor and its mass effect or nerve involvement, patients may report symptoms such as pain, hoarseness, dysphagia, cranial nerve neuropathies, and even Horner syndrome [22, 23].

Because schwannomas are quite rare in the oral cavity, they are often not immediately included in the differential diagnosis of oropharyngeal masses, causing delay in identification and treatment. Symptoms, however, can be significant as seen in patients who experienced dysphagia and apnea severe enough to warrant tracheotomy. Patients with tongue base schwannomas may also complain of pain, swelling, fasciculations, loss of tongue control, and weight loss, although most are asymptomatic until the tumor reaches a significant size [2, 5, 8, 16, 19, 20].

Schwannomas commonly arise from spinal nerve roots, intracranial nerves of the face, neck, extremities, mediastinum and pelvis. Most commonly affected nerve is the VIII cranial nerve (acoustic neurinomas) [1, 6, 18]. Leu and Chang in their review of 52 cases of neurilemmomas originating in head and neck region found that 25 Schwannomas originated in the scalp, face, and external auditory canal, 18 in the neck and only 9 Schwannomas were found in oral or nasal cavity [11]. Lopez and Ballestin in their study of 9 intraoral schwannomas found 3 schwannomas in vestibule, 2 each in tongue and palate and 1 each in floor of mouth and lower lip [12]. Within the tongue neurilemomas arise from the hypoglossal nerve. Typically, they remain asymptomatic and are slow growing neoplasm present several years before diagnosis. They produce symptoms by virtue of their large size and impingement on the affected nerve [1, 6, 18]. Other symptoms that may develop include pain, loss of taste sensation, motor and sensory loss.

Gallo et al. [7] reported on 157 cases where 45.2% of the cases involved the tongue and 13.3% involved the cheek. Das Gupta et al. [4] reported on 136 cases of schwannoma in the head and neck that consisted of 60 cases in the neck, 10 cases in the parotid gland, 9 cases in the cheek, 8 cases in the tongue, and 8 cases in the pharynx. Kun et al. [10] reported in their study that 18 out of 49 cases were in the neck and 11 cases were in the tongue. In the oral cavity, schwannoma is found most commonly in the tongue. Any part of the tongue may harbor the schwannoma. Robert et al. and Mevio et al. have reported schwannomas in the ventral part of the tongue [14]. Tip of the tongue is the least affected part. Robert et al. have documented a schwannoma in a 30-year-old woman arising in the tip of tongue.

They are usually solitary but multifocal lesions have also been reported. Multiple lesions occur in: (1) multiple localized neurilemmomas; (2) in association with neurofibroma in von Recklinghausen’s disease and (3) in schwannomatosis, a non-hereditary disease characterized by multiple subcutaneous and intradermal schwannomas along with variety of intracranial tumors [1, 6, 18].

Although most extracranial and intracranial schwannomas are benign, malignant schwannomas are reported in the literature and account for 5% of all soft tissue sarcomas. Of these, only 9–14% are located in the head and neck [22]. Malignant transformation of schwannoma is in contrast to neurofibroma, an exceptionally rare event and for practical purpose can be discounted. Those cases reported were either neurofibromas or had occurred in the setting of von Recklinghausen’s disease. Malignant schwannomas in the head and neck region are unusual [1]. Das Gupta and Brasfield found an incidence of 8% of malignant schwannomas and Ghosh et al. reported an incidence of 13.9% [4].

Computed tomographic or magnetic resonance imaging scans can be useful in the initial workup to determine the extent of the lesion and assist with delineating a differential diagnosis. Characteristic findings include a homogeneous enhancing lesion with or without central necrosis. Lack of surrounding tissue infiltration and well-circumscribed borders are also common features [22].

Because of their uncommon occurrence and nonspecific clinical presentation, the diagnosis of schwannoma is confirmed with histopathologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. Microscopic evaluation reveals an encapsulated tumor [22]. The definitive diagnosis requires histopathologic examination, ranging from densely packed spindle cells (Antoni A areas) with a typical palisading arrangement (Verocay bodies—Fig. 5) to loose hypocellular arrangements (Antoni B areas) with no definite architecture [5, 21]. Immunohistostaining commonly reveals positivity for S-100, Leu-7 antigen, vimentin, and glial fibrillary acidic protein and supports the Schwann cell origin of these tumors [12, 22].

Fig. 5.

Antoni A areas are composed of palisading spindled cells, also known as Verocay bodies (hematoxylin and eosin, 200×; inset, 200×)

The differential diagnosis must be made relative to malignant tumors (based on the data relating to speed of growth and clinical appearance of the neoplasm) and numerous benign epithelial and connective tissue neoformations (lipoma, traumatic fibroma, leiomyoma, granular cell tumor, and adenoma) [17, 21].

Oral lipomas are relatively innocuous tumors involving the oral submucosa and are most commonly encountered in the check; less common sites include tongue, floor of the mouth and lips. The Histopathology remains the gold standard in the diagnosis of liopoma. Lipomas differ little in microscopic appearance from the surrounding fat.

A fibroma is a focus of hyperplastic fibrous connective tissue representing a reactive response to local irritation or masticatory trauma. The most common location is along the occlusal line of the buccal mucosa—an area subject to masticatory trauma—although other locations, such as the tongue, labial mucosa, and gingiva, are possible. Fibromas manifest as asymptomatic, moderately firm, smooth-surfaced, pink, sessile or pedunculated nodules.

The leiomyoma is a benign neoplasm of smooth muscle. In the mouth it typically occurs in or on the tongue, presenting as a slowly enlarging, painless nodule which may eventually reach a couple of centimeter in size. It typically presents as a slowly enlarging, sessile, asymptomatic, firm submucosal mass or nodule, although occasional lesions are tender or painful, especially the vascular leiomyoma. All forms of leiomyoma are well encapsulated and show little cellular pleomorphism or mitotic activity. The solid tumor is comprised of interlacing bundles of spindle-shaped or stellate smooth muscle cells with elongated, blunt-ended, pale-staining nuclei. Nuclei may be palisaded and must then be differentiated from schwannoma, a task usually made easy by the lack of Verocay bodies and wavy, thin, spindled nuclei.

The lesions of granular cell tumour are usually larger and may be locally destructive, thus causing symptoms (e.g., pressure, obstruction, hemorrhage, ulceration, secondary infection) depending on the site. Histopathologic features of malignancy are unmistakable in some patients and pose no diagnostic difficulty. Necrosis, nuclear pleomorphism, spindling and increased mitotic activity are the features of malignancy.

Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common benign tumor arising from the major as well as minor salivary glands. The most common site of occurrence in the minor salivary glands is the palate. The histopathologic appearance of a pleomorphic adenoma is mainly composed of epithelial and myoepithelial elements, which are arranged in a variety of patterns and embedded in mucopolysaccharide stroma. The capsule is usually false, because its formation is caused by the fibrosis of the surrounding salivary parenchyma.

Treatment of benign schwannoma is complete surgical excision of the lesion, that does not usually result in any recurrence. Because recurrence of schwannoma usually occurs only with incomplete excision, treatment is aimed at total surgical removal of the tumor [5, 21]. Among approaches for removal of lingual schwannoma, transoral approach was suitable for our patient.

References

- 1.Bansal R, Trivedi P, Patel S. Schwannoma of the tongue. Oral Oncol Extra. 2005;41(2):15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ooe.2004.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassichis BA, McClay JE. Pedunculated neurilemoma of the tongue base. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(5):639–641. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiapasco M, Ronchi P, Scola G. Neurilemmoma (Schwannoma) of the oral cavity: a report of 2 clinical cases. Minerva Stomatol. 1993;42(4):173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD, Strong EW, Hajdu SI. Benign solitary schwannomas (neurilemomas) Cancer. 1969;24(2):355–366. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196908)24:2<355::AID-CNCR2820240218>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Bree R, Westervedl GJ, Smeele LE. Submandibular approach for excision of a large schwannoma in the base of the tongue. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257(6):283–286. doi: 10.1007/s004050050241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Soft tissue tumors. 3. St Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book Inc; 1995. pp. 821–888. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallo WJ, Moss M, Shapiro DN, Gaul JV. Neurilemoma: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Oral Surg. 1977;35(5):235–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez Beldarrain M, Fernandez Canton G, Garcia-Monco JC. Hypoglossal schwannoma: an uncommon cause of twelfth-nerve palsy. Neurologia. 2000;15(4):182–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones JA, McWilliam LJ. Intraoral neurilemmoma (schwannoma): an unusual palatal swelling. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63(3):351–353. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kun Z, Dao-Yi QI, Kui-Hua Z. A comparison between the clinical behavior of neurilemomas in the neck and oral and maxillofacial region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51(7):769–771. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leu YS, Chang KC. Extracranial head and neck schwannomas: a review of 8 years experience. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122(4):435–437. doi: 10.1080/00016480260000157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez Jl, Ballestin C. Intraoral schwannoma. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of nine cases. Arch Anat Cytol Pathol. 1993;41(1):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Jornet P, Bermejo-Fenoll A. Neurilemmoma of the tongue. Oral Oncol Extra. 2005;41(7):154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ooe.2005.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mevio E, Gorini E, Lenzi A, et al. Schwannoma of the tongue: one case report. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol. 2002;123(4):259–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nedim Arda H, Akdogan O, Arda N, Sarikaya Y. An unusual site for an intraoral schwannoma: a case report. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24(5):348–350. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(03)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okura A, Shigemori M, Abe T, et al. Hemiatrophy of the tongue due to hypoglossal schwannoma shown by MRI. Neuroradiology. 1994;36(3):239–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00588142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfeifle R, Baur DA, Paulino A, et al. Schwannoma of the tongue: report of 2 cases. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(7):802–804. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.24298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robert OG. The oral cavity. In: Steven GS, editor. Principle and practice of surgical pathology and cytology. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 1399–1460. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawhney R, Carron M, Mathog R. Tongue base schwannoma: report, review, and unique surgical approach. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008;29:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spandow O, Fagerlund M, Bergmark L, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of a large parapharyngeal neurilemoma located at the base of tongue. ORL. 1999;61:25–30. doi: 10.1159/000027634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tepe Karaca C, Erden Habesoglu T, Naiboglu B, Habesoglu M, Oysu C, Egeli E, Tosun I (2009) Schwannoma of the tongue in a child. Am J Otolaryngol (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wayne Lollar K, Pollak N, Daniel Liess B, Miick R, Zitsch R III (2010) Schwannoma of the hard palate. Am J Otolaryngol 31:139–140 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Zhang H, Cai C, Wang S, et al. Extracranial head and neck schwannomas: a clinical analysis of 33 patients. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:278–281. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000249929.60975.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]