Abstract

Background

Multiple studies have reported favorable short-term results after treatment of spondylolisthesis and other degenerative lumbar diseases with minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. However, to our knowledge, results at a minimum of 5 years have not been reported.

Questions/purposes

We determined (1) changes to the Oswestry Disability Index, (2) frequency of radiographic fusion, (3) complications and reoperations, and (4) the learning curve associated with minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion at minimum 5-year followup.

Methods

We reviewed our first 124 patients who underwent minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion to treat low-grade spondylolisthesis and degenerative lumbar diseases and did not need a major deformity correction. This represented 63% (124 of 198) of the transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion procedures we performed for those indications during the study period (2003–2007). Eighty-three (67%) patients had complete 5-year followup. Plain radiographs and CT scans were evaluated by two reviewers. Trends of surgical time, blood loss, and hospital stay over time were examined by logarithmic curve fit-regression analysis to evaluate the learning curve.

Results

At 5 years, mean Oswestry Disability Index improved from 60 points preoperatively to 24 points and 79 of 83 patients (95%) had improvement of greater than 10 points. At 5 years, 67 of 83 (81%) achieved radiographic fusion, including 64 of 72 patients (89%) who had single-level surgery. Perioperative complications occurred in 11 of 124 patients (9%), and another surgical procedure was performed in eight of 124 patients (6.5%) involving the index level and seven of 124 patients (5.6%) at adjacent levels. There were slowly decreasing trends of surgical time and hospital stay only in single-level surgery and almost no change in intraoperative blood loss over time, suggesting a challenging learning curve.

Conclusions

Oswestry Disability Index scores improved for patients with spondylolisthesis and degenerative lumbar diseases treated with minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion at minimum 5-year followup. We suggest this procedure is reasonable for properly selected patients with these indications; however, traditional approaches should still be performed for patients with high-grade spondylolisthesis, patients with a severely collapsed disc space and no motion seen on the dynamic radiographs, patients who need multilevel decompression and arthrodesis, and patients with kyphoscoliosis needing correction.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See the Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion utilizes a unilateral approach that allows for simultaneous neural canal decompression with an anterior interbody arthrodesis through a single posterior incision [8, 11]. This procedure diminishes neural retraction and reduces the risk of neural injury compared with bilateral posterior lumbar interbody fusion [8, 12, 28]. It is possible to perform unilateral posterior surgery using less invasive approaches to neural decompression and intervertebral arthrodesis through a tubular retractor and by augmenting the fusion construct with percutaneous pedicle screw instrumentation. Putative benefits of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion, compared with a traditional open approach, include less postoperative pain, reduced blood loss, earlier rehabilitation, shorter hospitalization, and fewer complications [4, 6, 21, 23, 24]. This technique also has disadvantages, including longer operative time and a steep learning curve compared with conventional open methods [4, 6, 16, 19, 21, 24]. As with other surgical procedures, however, understanding the learning curve of this technique is important to improve surgical performance.

Multiple studies have reported favorable results after treatment of spondylolisthesis and other degenerative lumbar diseases with minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion [3, 4, 6, 8, 16, 17, 20–25]. These studies described results from 6 to 49 months after surgery; however, to our knowledge, data at minimum 5-year followup have never been reported.

We therefore determined (1) changes to the Oswestry Disability Index, (2) frequency of radiographic fusion, (3) complications and reoperations, and (4) the learning curve associated with minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion at a minimum followup of 5 years.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection

We reviewed clinical and radiographic data for the first 124 patients undergoing minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion to treat low-grade spondylolisthesis and degenerative lumbar diseases performed by one of the authors (YP). These 124 patients represented 63% (124 of 198) of the transforaminal lumbar interbody arthrodesis procedures we performed for these indications. Patient data were stored in a prospectively maintained database, but the design of this study is retrospective. After approval by our institutional review board, we queried our institution’s database to identify patients who had this procedure at least 5 years earlier (from October 2003 to May 2007). Clinical and radiographic evaluations were performed at regular intervals (preoperatively and at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 5 years postoperatively). Two independent investigators (JWH, YTL) conducted the clinical and radiographic assessments. A third adjudicating reviewer (JHY) resolved disagreements between the two reviewers. Data from the preoperative and 2- and 5-year followup visits were analyzed in this study (Fig. 1). Detailed demographic and surgical data (Table 1) are provided. Of the 124 patients included in this series, 108 had surgery at one level, 15 at two levels, and one at three levels. Operative data, including surgical time, hospital stay, and intraoperative blood loss, are compared for the patients who underwent single-level surgery and those who underwent multilevel surgery (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

A flowchart shows the loss to followup over the 5-year followup period.

Table 1.

Demographic and surgical data

| Variable | Overall | 2 years | 5 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the time of surgery (years)* | 59.3 (23–82) | ||

| Male (number of patients) | 45 (36%) | ||

| BMI* | 25.0 ± 3.5 (18.2–42.7) | ||

| Current smoker at the time of surgery (number of patients) | 30 (24%) | ||

| Coexisting medical diseases (number of patients) | 67 (54%) | ||

| Diabetes (number of patients) | 26 (21%) | ||

| Osteoporosis (number of patients) | 29 (23%) | ||

| Previous back surgery at the index level (number of patients) | 8 (5 microdiscectomy, 3 laminectomy) | ||

| Total number of patients | 124 | 106 | 83 |

| Surgery level (number of patients) | |||

| Single level | 108 (87%) | 91 (86%) | 72 (87%) |

| Two levels | 15 (12%) | 14 (13%) | 11 (13%) |

| Three levels | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Total number of treated segments | 141 | 122 | 94 |

| Treated segments (number of segments) | |||

| L3–L4 | 11 (8%) | 10 (8%) | 7 (7%) |

| L4–L5 | 86 (61%) | 70 (57%) | 55 (59%) |

| L5–S1 | 30 (21%) | 29 (24%) | 21 (22%) |

| L5–L6 | 14 (10%) | 13 (11%) | 11 (12%) |

| Preoperative diagnosis of each treated segment (number of segments) | |||

| Spondylolisthesis | 75 (53%) | 66 (55%) | 51 (54%) |

| Degenerative spondylolisthesis | 40 | 34 | 26 |

| Isthmic spondylolisthesis | 35 | 32 | 25 |

| Foraminal stenosis and/or foraminal disc herniation | 44 (31%) | 35 (29%) | 25 (27%) |

| Degenerative segmental instability | 11 (8%) | 10 (8%) | 8 (9%) |

| Recurrent disc herniation | 5 (4%) | 5 (4%) | 4 (4%) |

| Postlaminectomy instability | 3 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 3 (3%) |

| Degenerative disc disease presenting low back pain and/or radiating pain down to lower extremities | 3 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 3 (3%) |

* Values are expressed as mean or mean ± SD, with range in parentheses.

Table 2.

Comparison of operative data of the single- and multilevel fusion groups

| Variable | Single-level fusion group (n = 108) | Multilevel fusion group (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Operative time (minutes)* | 176.3 ± 38.7 (80–305) | 235.0 ± 27.9 (180–270) |

| Average intraoperative blood loss (mL)* | 238.4 ± 183.0 (50–800) | 329.4 ± 256.4 (50–900) |

| Blood transfusion (number of patients) | 17 (16%) | 6 (38%) |

| Hospital stay (days)* | 7.5 ± 5.4 (1–37) | 10.3 ± 10.8 (2–45) |

* Values are expressed as mean ± SD, with range in parentheses.

Surgical Indications

The surgical indications for this approach at our center include treatment of low back pain and pain radiating down to the lower extremities (leg pain) from spondylolisthesis and other degenerative lumbar diseases that are refractory to nonoperative treatment (medication, physiotherapy, epidural steroid injections). Adult low-grade (Grade I/II) isthmic or degenerative spondylolisthesis was the major indication for this procedure in this series. Other surgical indications included foraminal stenosis and/or foraminal disc herniation, degenerative segmental instability, recurrent disc herniation, degenerative disc disease, and postlaminectomy instability. Segmental instability was defined as 4 mm or more of translation or 10° or more of angular motion seen on the preoperative flexion and extension lateral radiographs. The surgical goal was neural decompression and arthrodesis for the treatment of back and leg pain from spondylolisthesis and degenerative lumbar diseases.

Relative contraindications for minimally invasive surgery in our study included (1) high-grade (Grade III/IV) spondylolisthesis, (2) a severely collapsed disc space and no motion seen on the flexion-extension radiographs, (3) multilevel (> three levels) decompression and arthrodesis, (4) combined coronal and/or sagittal deformities (kyphoscoliosis) needing correction, and (5) lumbar disease involving trauma, infection, and pathologic causes. Patients with these contraindications were treated by traditional open surgery.

Surgical Procedures

Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 22-mm-diameter METRx™ (Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA) tubular retractor was introduced through a 2.5-cm incision for both neural decompression and to access the interbody space in all patients. The approach was carried out on the side with the worst preoperative radiculopathy.

Sextant™ (Medtronic) screws and rods were placed percutaneously on the contralateral side to distract the interbody space and maintain the distracted position. Once the optimal interbody distraction had been achieved, endplate preparation was performed through tubular retractor using curettes and endplate scrapers. After all of the cartilaginous endplate was removed, the autogenous bone obtained from the resected lamina and facet was mixed with demineralized bone matrix (Osteofil® RT DBM paste; Regeneration Technologies Inc, Alachua, FL, USA) and placed anteriorly and contralaterally to the annulotomy within the interbody space in all cases. A polyetheretherketone cage (Capstone®; Medtronic) was then inserted into the disc space. Ipsilateral percutaneous pedicle screws and rods were then placed through the same incision. No additional contralateral facet fusion was performed. More detailed descriptions of the procedure are available elsewhere [8, 14, 16, 17, 21, 23–25].

Outcome Measures

Clinical outcome measures included the Oswestry Disability Index and numeric rating scale scores for back and leg pain. The Oswestry Disability Index was estimated using the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire [5]. Scores on the Oswestry Disability Index range from 0 to 100 points, with lower scores representing less pain and better function. Back and leg pain scores were assessed with a 10-point numeric rating scale, where 0 was defined as no pain and 10 as very severe pain. Outcome measure change was evaluated on the basis of both the mean change and the percentage of patients reaching a minimum clinically important difference threshold. The minimum clinically important difference is a threshold level of outcome score change above which patients recognize their improvement to be clinically relevant [2]. We used the previously published minimum clinically important difference threshold of 10 points for the Oswestry Disability Index score [10].

Radiographic measures included plain radiographs with flexion and extension views and fine-cut CT scans with sagittal and coronal reformatting. The CT scans were used as a secondary measure only when bridging trabecular bone was not observed on plain radiographs. A total of 106 patients (86%) had CT scans because of equivocal findings on plain radiography. Radiographic fusion was assessed using the anterior fusion grades described by Bridwell et al. [1]: Grade I, fused with remodeling and trabeculae present; Grade II, graft intact but not fully remodeled and incorporated, with no lucencies above or below; Grade III, graft intact but with a definite lucency at the top or bottom of the graft; and Grade IV, definitely not fused, with resorption of bone graft and collapse. Both Grades I and II were considered signs of radiographic fusion.

Data on adverse events were collected during three separate time frames: (1) the perioperative period (day of surgery to 12 weeks postoperatively), (2) the 2-year postoperative period (12 weeks to 2 years postoperatively), and (3) the 5-year postoperative period (from 2 to 5 years postoperatively). Adverse events that were not specifically related to spine surgery and did not affect recovery (for example, urinary tract infection, ileus, anemia) were excluded. Adjacent segment diseases were designated as conditions requiring treatment of symptoms, including nonoperative treatments such as medication, physiotherapy, and epidural steroid injection, up to a second surgery that was indicated when symptoms were refractory to nonoperative treatments. Adjacent segment disease was defined as a newly developed or progressively worsening process compared with the preoperative radiographic findings at the cranial and caudal segments adjacent to the index fusion level. These findings included segmental instability (including spondylolisthesis), herniated intervertebral disc, spinal stenosis, and vertebral fracture. When the patients presented with new signs and symptoms related to adjacent segment disease during followup, the lesions were evaluated by CT and by comparing pre- and postoperative MR images.

Repeat surgical procedures at the index level during the followup periods were documented as revisions, hardware removals, supplemental fixations, or reoperations, depending on the clinical circumstances. Other surgical procedures performed at the adjacent level to treat symptomatic adjacent segment diseases were also classified as second surgeries.

Learning Curve

Graphs were created to assess the learning curve of the procedure. Patients were arranged in chronological order from the first case to the last one on the horizontal axis of the graph. The variables surgical time, hospital stay, and intraoperative blood loss were plotted on the vertical axis of the graph. To determine the curve trend of each variable with increasing number of the cases, a logarithmic curve fit-regression analysis was performed separately for patients who underwent single-level surgery and those who underwent multilevel surgery. In addition, complications were plotted against serial number of patients.

Statistical Analyses

To assess the postoperative improvement in all clinical outcome scores compared with preoperative values, longitudinal analyses for continuous variables were carried out using one-way (time) repeated-measures ANOVA. We considered p values of less than 0.05 to be significant. The data analysis was generated using SAS® software (Version 9.2 of the SAS® system for Linux; SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Oswestry Disability Index

Oswestry Disability Index scores improved after surgery, and the improvement was maintained out to 5 years (Table 3). The Oswestry Disability Index improved an average of 35.5 points at 2 years and 36 points at 5 years from a mean preoperative score of 60.3 points (p < 0.001, preoperative scores versus 5-year scores). At 2 years, a decrease in the Oswestry Disability Index of greater than 10 points (defined as the minimum clinically important difference) was achieved in 102 of 106 patients (96%) and was maintained in 79 of 83 patients (95%) at 5 years (Table 3). At 2 and 5 years, the mean back pain and leg pain scores improved from the preoperative scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical outcome scores

| Variable | Preoperative (n = 124) | 2 years* (n = 106) | 5 years* (n = 83) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Value | Improvement | Value | Improvement | |

| Oswestry Disability Index (points) | 60.3 ± 9.7 | 24.4 ± 16.8 | 35.5 ± 15.4 | 24.0 ± 16.1 | 36 ± 14.8 |

| Back pain (points) | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 3.7 ± 2.0 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 3.2 ± 2.5 |

| Leg pain (points) | 7.7 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 2.2 | 6.5 ± 2.2 | 0.9 ± 1.7 | 6.7 ± 2.0 |

| > 10 points’ improvement in Oswestry Disability Index (number of patients) | 102 (96%) | 79 (95%) | |||

Values are expressed as mean ± SD; * clinical outcome measures improved significantly from preoperative scores by 2 years, and these improvements were maintained at 5 years (p < 0.001, by one-way [time] repeated-measures ANOVA; clinical outcome scores at 5 years were not significantly different from the outcome scores at 2 years.

Radiographic Fusion

Successful fusion was identified in 81 of 106 patients (76%) at 2 years and 67 of 83 patients (81%) at 5 years (Table 4). In the single-level fusion group, solid fusion was achieved in 75 of 91 patients (82%) at 2 years and 64 of 72 patients (89%) at 5 years (Fig. 2). In the multilevel fusion group, however, solid fusion was achieved only in six of 15 patients (43%) (12 of 31 treated segments) at 2 years and three of 11 patients (27%) (six of 22 treated segments) at 5 years. In the multilevel fusion group, those who achieved successful fusion achieved fusion at all of their segments and those with nonunion did not achieve fusion at any of their segments.

Table 4.

Radiographic fusion status

| Variable | 2 years | 5 years |

|---|---|---|

| Fusion grade (number of treated segments) | ||

| I | 41 (34%) | 50 (53%) |

| II | 46 (38%) | 20 (21%) |

| III | 9 (7%) | 8 (9%) |

| IV | 26 (21%) | 16 (17%) |

| Solid fusion (I + II) (number of treated segments/patients) | 87 (72%)/81 (76%) | 70 (74%)/67 (81%) |

| Pseudarthrosis (III + IV) (number of treated segments/patients) | 35 (28%)/25 (24%) | 24 (26%)/16 (19%) |

| Total number of treated segments/patients | 122/106 | 94/83 |

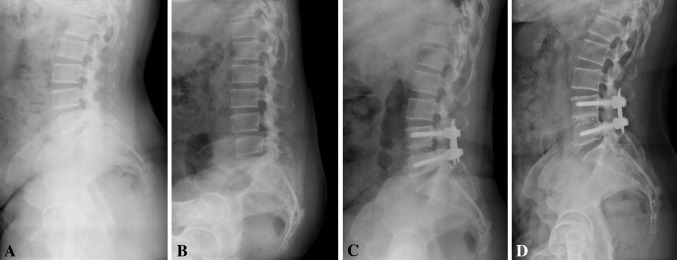

Fig. 2A–D.

Images illustrate the case of Patient 69, a 46-year-old woman who underwent minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Preoperative (A) standing lateral and (B) flexion radiographs illustrate low grade of spondylolisthesis. (C) A 2-year postoperative standing lateral radiograph shows Bridwell Grade II anterior interbody fusion. (D) A 5-year postoperative standing lateral radiograph demonstrates Grade I fusion.

Adverse Events and Additional Surgical Procedures

Adverse events occurred in 11 of 124 patients (9%) during the perioperative period, 35 of 106 patients (33%) before 2 years, and 41 of 83 patients (49%) during the 2- to 5-year time frame (Table 5). Eight patients (7%) had additional surgical procedures involving the index level and seven patients (6%) required intervention at adjacent levels (Table 6). Asymptomatic pseudarthrosis was recognized in 11 of 25 patients with nonunions (44%) at 2 years and five of 16 patients (31%) at 5 years. The others were symptomatic but without significant pain or disability, which made revision surgery to repair the nonunion unwarranted. Symptomatic adjacent segment diseases were identified in 10 of 106 patients (9%) before 2 years and 25 of 83 patients (30%) between 2 and 5 years. Eight patients before 2 years and 20 patients from 2 to 5 years reported symptomatic adjacent segment diseases and were managed with nonoperative treatments. One patient before 2 years and four patients from 2 to 5 years undertook additional surgical procedures for symptomatic adjacent segment diseases. Furthermore, two patients, one before 2 years and the other during the 2- to 5-year followup, underwent second surgical procedures involving both index and adjacent levels to treat combined adverse events of pseudarthrosis and adjacent segment diseases, as nonoperative treatments failed after a sufficient trial.

Table 5.

Adverse events during the 5 years after index surgery

| Adverse event | Number of patients with adverse event | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative period | 2-year postoperative period | 5-year postoperative period | |

| Dural tears | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Screw misplacement | 2 (2)* | 0 | 0 |

| Cage migration | 2 (2)* | 0 | 0 |

| Grafted bone extrusion | 1 (1)* | 0 | 0 |

| Temporary postoperative neuralgia | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Postoperative neurologic deficit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Deep wound infection | 2 (2)* | 0 | 0 |

| Instrumentation failure | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pseudarthrosis | 0 | 25 (1)*,† | 16 (1)*,† |

| Symptomatic adjacent segment disease | 0 | 10 (2)*,† | 25 (5)*,† |

| Spinal stenosis including foraminal stenosis | 0 | 8 (2)*,† | 17 (5)*,† |

| Vertebral compression fracture | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Herniated lumbar disc | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Spondylolisthesis | 0 | 1 | 1 |

* The numbers in parentheses represent the number of patients within the adverse events category who had a second surgical procedure; † the numbers in parentheses include one duplication of a patient who had a second surgical procedure due to dual adverse events of pseudarthrosis and adjacent segment disease.

Table 6.

Second surgical procedures during the 5 years after index surgery

| Procedure | Number of patients with second surgical procedure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative period | 2-year postoperative period | 5-year postoperative period | Total (n = 124) | |

| Index level | 7 | 0 | 1 | 8 (6.5%) |

| Revision | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Removal | 3* | 0 | 1§ | 4 |

| Supplemental fixation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reoperation | 4† | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Adjacent level | 0 | 2‡ | 5‡ | 7 (5.6%) |

| Laminectomy | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Laminectomy and posterolateral fusion | 0 | 2‡ | 2‡ | 4 |

| Other lumbar levels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

* One patient had implant removal for a misplaced screw, two patients had implant removal for infected cages, and two patients underwent anterior or posterior interbody arthrodesis along with implant removal for deep wound infection; † two reoperations were for cage migrations, one for a misplaced screw, and one for an extruded graft bone fragments; ‡ the numbers include one patient who underwent second surgery due to dual adverse events of pseudarthrosis and adjacent segment disease; § implant removal was performed between 2 and 5 years postoperatively, as the patient wanted to remove implanted devices for the relief of her back discomfort even after a successful fusion had been achieved.

Learning Curve

In the single-level fusion group, operative time and hospital stay diminished gradually with a descending curve trend over the course of the case series (Fig. 3A–B). In the multilevel fusion group, however, operative time and hospital stay did not decrease over time with the numbers available, nor did intraoperative blood loss decrease over the course of the case series in either group (Fig. 3C). However, most perioperative complications occurred during the earlier portion of the series rather than the later portion (eight versus three events) (Fig. 3D). These slowly descending trends of operative time and hospital stay noted only in the single-level surgery and almost no change over time in the multilevel group suggest a very challenging learning curve.

Fig. 3A–D.

Logarithmic curve fit-regression analysis shows curve trends over the case series for (A) operative time, (B) intraoperative blood loss, (C) hospital stay, and (D) adverse events in the perioperative period. Adverse events included pedicle screw misplacement (Patients 5, 45), grafted bone extrusion (Patient 11), cage migration (Patients 27, 36), temporary postoperative neuralgia (Patients 18, 39, 121), deep wound infection (Patients 13, 70), and dura tear (Patient 117); pseudarthrosis and adjacent segment disease were excluded. The slowly descending trends over time represent a challenging learning curve. x = patient number; y = operative time, intraoperative blood loss, or hospital stay; R2 = coefficient of determination.

Discussion

Multiple studies have reported favorable results after treatment of spondylolisthesis and other degenerative lumbar diseases with minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion [3, 4, 6, 14, 16, 17, 20–25]. These studies described results from 6 to 49 months postoperatively; however, to our knowledge, 5-year followup data have never been reported. We therefore determined 5-year outcomes including (1) changes to the Oswestry Disability Index, (2) frequency of radiographic fusion, (3) complications and reoperations, and (4) the learning curve associated with minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion.

Our study is not without weaknesses. Although the data were collected prospectively, our study is retrospective with a heterogeneous sample, and the patients were not randomly selected. The procedures included here were selected, representing 63% of our patients who underwent transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion procedures during the study period. Since this study concerned our early experiences with this procedure, we chose easier procedures with limited indications, as is almost always the case with new techniques. A more homogeneous sample, randomly and prospectively selected, would provide stronger evidence. Another potential limitation is that the overall followup rate was only 67%. This brings in so-called transfer bias, which almost always makes the results look better than they are. The likelihood of reoperation/revision is higher among patients who did not followup than among those who did. Our results therefore probably should be considered best-case results. Furthermore, given the rarity of minimally invasive spinal fusion surgeries performed at multiple levels, the data from multiple segmental lumbar arthrodesis were limited by this small sample. Additionally, we did not examine the radiographic measurements to determine postoperative sagittal alignment, lumbar lordosis, and correction of a slip and collapsed disc space; these objective measures might have strengthened the findings. Finally, our study has no control group for comparison. The most ideal control group would be a matched cohort of patients undergoing traditional open surgery. We would then be able to assess the difference in long-term results between minimally invasive and traditional open procedures.

The large majority of the patients treated with minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion had an improvement in the Oswestry Disability Index score of greater than 10 points at 5 years. Mean improvement in the Oswestry Disability Index score was 41% at 2 years and 40% at 5 years. Rouben et al. [22] found 88% and 86% of patients had an Oswestry Disability Index score change of at least 20% at 24 and 49 months after minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion surgery. Their average improvement was 46% at 2 years and 40% at 49 months. Schwender et al. [25] reported an average 32% improvement in the Oswestry Disability Index score postoperatively, with an average followup of 22.6 months. When comparing with traditional open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion, average improvements in the Oswestry Disability Index score of 43% at 2 years and 24% at the latest followup between 35 and 64 months postoperatively were noted in patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis [9]. The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial found a 24% improvement in the Oswestry Disability Index score at 2 years postoperatively in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis [27]. As compared with other studies, our data show a comparable and substantial improvement in the Oswestry Disability Index scores at 2 and 5 years postoperatively.

Successful radiographic fusion was seen in 81% of patients at 5 years and in 82% and 89% of single-level surgeries at 2 and 5 years, respectively. Our fusion rate of single-level surgeries compares favorably to those previously reported in the literature for patients undergoing conventional lumbar arthrodesis [7, 9, 13, 15]. On the other hand, the multilevel fusion group revealed a low fusion rate. These patients with nonunion may become more symptomatic with time. Successful fusion has been suggested to correlate with improved long-term clinical results in terms of back pain and lower limb function [15]. In previous studies of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion surgery [8, 17, 21, 25], a fusion rate of almost 100% was reported based on the flexion-extension radiographs and/or postoperative CT scan at 2 years. In particular, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (rhBMP-2) soaked in a collagen sponge carrier was used in these series [8, 17, 21, 25]. Rouben et al. [22] reported that 96% of patients showed fusion at 1 year postoperatively using local bone with rhBMP-2. Direct comparison of our fusion rate with others is difficult because of the different graft material and methods of measurement. Application of rigorous fusion criteria and nonuse of rhBMP-2 might explain the relatively low rate of fusion compared with historical studies [8, 17, 21, 22, 25].

Perioperative complications occurred in 9% of our series. Over the 5-year followup period, the second surgery rate for the index level was low (6.5%). These rates are lower than the recently reported 3- to 5-year results of traditional open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion by Tormenti et al. [26]. They reported 25% of patients had at least a single procedure-related complication. The most common complications were durotomy (14%) and infection (4%). Symptomatic misplaced pedicle screws (2%) and cage migration (2%) were also reported. Our complication and reoperation rates appear comparable to other results of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion [3, 4, 6, 8, 14, 16, 19, 22–25]. In the series of Rouben et al. [22], the overall rate for repeat surgery (14.2%) was higher than ours. The most common event was removal of painful pedicle screws (7.6%). Moreover, in contrast with these perioperative complications, adjacent segment disease after arthrodesis surgery has been one of the most important sequelae affecting long-term results [18]. Our data also found a growing rate of symptomatic adjacent segment diseases with time during 5 years so that second surgeries were also increasing. Further study is warranted to investigate the long-term effects of minimally invasive fusion surgery on the development of adjacent segment diseases by comparing it to the traditional open surgery.

Another important result of our study is that minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion has a challenging learning curve in terms of operative time, intraoperative blood loss, and hospital stay. Lee et al. [16] demonstrated a steep learning curve for this technique in a series of 86 cases. They found that the surgeon’s experience was correlated with reduced operative time and blood loss during surgery. Their complications were evenly distributed in both early and late portions of the case series. In our series of 124 patients, only the single-level surgery group showed significantly but slowly reducing trends of operative time and hospital stay with increasing numbers of cases. Blood loss during surgery, however, did not decrease as the number of patients increased in either the single-level or the multilevel surgery group. Moreover, perioperative complications occurred more frequently in the earlier patients in our series. These findings suggest that this procedure is difficult to learn.

Our study demonstrated that minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion improved clinical scores in patients with spondylolisthesis and other lumbar degenerative diseases; that the improvements observed were greater than the minimal clinically important difference threshold [2, 10], consistent with the standards of arthrodesis outcomes described in the literature [3, 4, 6, 16, 17, 19–25]; and that these improvements were maintained up to 5 years after surgery. Our study also illustrated a challenging learning curve for this procedure. On the basis of these results, we suggest that minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody arthrodesis can be a reasonable treatment option for properly selected patients with spondylolisthesis and degenerative lumbar diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ju-Hyung Yoo MD for his great support as a third adjudicating reviewer. We are also grateful to Manee Shim RN and Jihye Jung RN for their enormous assistance with the data collection.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, McEnery KW, Baldus C, Blanke K. Anterior fresh frozen structural allografts in the thoracic and lumbar spine: do they work if combined with posterior fusion and instrumentation in adult patients with kyphosis or anterior column defects? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:1410–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD, Polly DW, Jr, Schuler TC. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J. 2007;7:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deutsch H, Musacchio MJ., Jr Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with unilateral pedicle screw fixation. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E10. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhall SS, Wang MY, Mummaneni PV. Clinical and radiographic comparison of mini-open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in 42 patients with long-term follow-up. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:560–565. doi: 10.3171/SPI.2008.9.08142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O’Brien JP. The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan S, Zhao X, Zhao F, Fang X. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of degenerative lumbar diseases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:1615–1620. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c70fe3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischgrund JS, Mackay M, Herkowitz HN, Brower R, Montgomery DM, Kurz LT. 1997 Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective, randomized study comparing decompressive laminectomy and arthrodesis with and without spinal instrumentation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:2807–2812. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foley KT, Holly LT, Schwender JD. Minimally invasive lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(15 suppl):S26–S35. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000076895.52418.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hackenberg L, Halm H, Bullmann V, Vieth V, Schneider M, Liljenqvist U. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a safe technique with satisfactory three to five year results. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:551–558. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0830-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hägg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A, Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:12–20. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harms JG, Jeszensky D. The unilateral, transforaminal approach for posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Orthop Traumatol. 1998;6:88–99. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hee HT, Castro FP, Jr, Majd ME, Holt RT, Myers L. Anterior/posterior lumbar fusion versus transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: analysis of complications and predictive factors. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:533–540. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herkowitz HN, Kurz LT. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:802–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holly LT, Schwender JD, Rouben DP, Foley KT. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: indications, technique, and complications. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:1–5. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kornblum MB, Fischgrund JS, Herkowitz HN, Abraham DA, Berkower DL, Ditkoff JS. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective long-term study comparing fusion and pseudarthrosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:726–734. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000119398.22620.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JC, Jang HD, Shin BJ. Learning curve and clinical outcomes of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: our experience in 86 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37:1548–1557. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318252d44b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park P, Foley KT. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with reduction of spondylolisthesis: technique and outcomes after a minimum of 2 years’ follow-up. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:E16. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/25/8/E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park P, Garton HJ, Gala VC, Hoff JT, McGillicuddy JE. Adjacent segment diseases after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:1938–1944. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000137069.88904.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park Y, Ha JW. Comparison of one-level posterior lumbar interbody fusion performed with a minimally invasive approach or a traditional open approach. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:537–543. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000256473.49791.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park Y, Ha JW, Lee YT, Sung NY. The effect of a radiographic solid fusion on clinical outcomes after minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2011;11:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng CW, Yue WM, Poh SY, Yeo W, Tan SB. Clinical and radiological outcomes of minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1385–1389. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a4e3be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouben D, Casnellie M, Ferguson M. Long-term durability of minimally invasive posterior transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a clinical and radiographic follow-up. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011;24:288–296. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3181f9a60a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheufler KM, Dohmen H, Vougioukas VI. Percutaneous transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of degenerative lumbar instability. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(4 suppl 2):203–213. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255388.03088.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schizas C, Tzinieris N, Tsiridis E, Kosmopoulos V. Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: evaluating initial experience. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1683–1688. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0687-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwender JD, Holly LT, Rouben DP, Foley KT. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility and initial results. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(suppl):S1–S6. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000132291.50455.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tormenti MJ, Maserati MB, Bonfield CM, Gerszten PC, Moossy JJ, Kanter AS, Spiro RM, Okonkwo DO. Perioperative surgical complications of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a single-center experience. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16:44–50. doi: 10.3171/2011.9.SPINE11373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Zhao W, Blood EA, Tosteson ANA, Birkmeyer N, Herkowitz H, Longley M, Lenke L, Emery S, Hu SS. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis: four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1295–1304. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitecloud TS, 3rd, Roesch WW, Ricciardi JE. Transforaminal interbody fusion versus anterior-posterior interbody fusion of the lumbar spine: a financial analysis. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:100–103. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200104000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]