Abstract

Background

Self-efficacy with using a wheelchair is an emerging construct in the wheelchair-use literature that may have implications for the participation frequency in social and personal roles of wheelchair users.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the direct and mediated effects of self-efficacy on participation frequency in community-dwelling manual wheelchair users aged 50 years or older.

Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted.

Methods

Participants were community-dwelling wheelchair users (N=124), 50 years of age or older (mean=59.7 years), with at least 6 months of experience with wheelchair use. The Late-Life Disability Instrument, the Wheelchair Use Confidence Scale, the Life-Space Assessment, and the Wheelchair Skills Test–Questionnaire Version measured participation frequency, self-efficacy, life-space mobility, and wheelchair skills, respectively. Multiple regression analyses with bootstrapping were used to investigate the direct and mediated effects. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health was used to guide the analyses.

Results

Self-efficacy was a statistically significant determinant of participation frequency and accounted for 17.2% of the participation variance after controlling for age, number of comorbidities, and social support. The total mediating effect by life-space mobility, wheelchair skills, and perceived participation limitations was statistically significant (point estimate=0.14; bootstrapped 95% confidence interval=0.04, 0.24); however, the specific indirect effect by the wheelchair skills variable did not contribute to the total effect above and beyond the other 2 mediators. The mediated model accounted for 55.0% of the participation variance.

Limitations

Causality cannot be established due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, and the self-report nature of our data from a volunteer sample may be influenced by measurement bias or social desirability, or both.

Conclusion

Self-efficacy directly and indirectly influences the participation frequency in community-dwelling manual wheelchair users aged 50 years or older. Development of interventions to address low self-efficacy is warranted.

Participation, or involvement in life situations,1 is an important focus in the rehabilitation of older individuals because of its strong association with quality of life.2,3 Mobility limitations are a cause of disability among community-dwelling individuals4,5 and are the primary reason for participation restrictions in individuals aged 50 years or older.6 Individuals with mobility limitations are often prescribed wheelchairs to overcome participation restrictions; however, these individuals commonly report low participation levels, with rates as low as 8.3% in the frequency and duration of physical activity participation compared with 48.8% reported by ambulatory individuals.7

There is little evidence explaining the low participation frequency of community-dwelling manual wheelchair users. Shields8 noted, however, that older individuals are more likely than younger individuals to lack independence with using their wheelchair, and LaPlante and Kaye9 reported that difficulties with wheeled mobility increase with age. Although there is a void in our knowledge on the participation of community-dwelling manual wheelchair users aged 50 years or older, the existing evidence from other populations of wheelchair users may inform our understanding. For example, existing predictive models of participation developed with younger community-dwelling wheelchair users10,11 and older wheelchair users residing in nursing homes12 identify wheelchair skills as a determinant of participation. Wheelchair skills, therefore, also may affect the participation of community-dwelling manual wheelchair users aged 50 years or older. It also is plausible that variables such as depression,12 mobility,12 and injury or demographic factors (eg, age, sex)11,13 may be important, but their importance has not been established.

Although existing evidence may contribute to the development of models predicting the participation frequency of adult community-dwelling wheelchair users, the variables considered to date have explained between 9.0%13 and 53.0%12 of the variance of various forms of participation. These findings indicate that there is much more to be investigated to enhance our knowledge about the participation of wheelchair users in order to sufficiently address areas for improvement. When considering reports that the proportion of older American wheelchair users has been increasing by 4.3% per year9 and evidence that aging is a risk factor for wheelchair use,8,9 there is a clear need for more research.

Because studies consistently show that the ability to use a wheelchair is an important determinant of participation, a person's belief in his or her ability (ie, self-efficacy14) similarly may provide important explanatory value, as has been demonstrated in many areas of health. For example, self-efficacy has been shown to be an important determinant of leisure and physical activity participation in several populations, including individuals with a lower extremity amputation15 and older adults with chronic conditions.16 The construct, however, has yet to receive adequate investigation in wheelchair users.

Self-efficacy with using a wheelchair is the belief individuals have in their ability to use their wheelchair in a variety of challenging situations.17 Prevalence data suggest that 39.0% (95% confidence interval [95% CI]=29.0, 49.0) of older community-dwelling individuals have low self-efficacy with wheelchair use.18 Some evidence also indicates that there is a statistically significant positive association between self-efficacy and participation frequency in older, community-dwelling wheelchair users19 and that the construct is modifiable.20 These preliminary data suggest that self-efficacy with using a wheelchair may be of clinical interest; however, more robust research is needed.

Because social cognitive theory postulates self-efficacy has both direct and indirect effects on behavior,14 the objectives of this study were: (1) to investigate the direct effect of self-efficacy on participation frequency and (2) to test the indirect effect via multiple mediators. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)1 framework was used to classify variables and guide our investigation of the hypotheses that self-efficacy (conceptualized as a body function) is an independent predictor of participation frequency in older, community-dwelling manual wheelchair users after controlling for important health, environmental, and personal contextual factors and that the association is mediated by functioning/disability variables at the ICF's body, person, and societal levels.

Method

Design and Participants

Community-dwelling manual wheelchair users who were 50 years of age or older and living in British Columbia or Quebec, Canada, were enrolled in this cross-sectional study. Participants had at least 6 months of experience using a wheelchair on a daily basis and communicated in English or French. Individuals who had an acute illness or a Mini-Mental State Examination score of less than 2321 were excluded from study.

Recruitment

Therapists from British Columbia's largest rehabilitation center recruited volunteer participants, as did community-based therapists serving both urban and rural populations in 3 health authorities. Advertisements about the study were also posted at community and senior centers and sent to disability advocacy groups. In Quebec, participants were recruited from 2 rehabilitation centers in Quebec City and Montreal. Individuals who met the study's inclusion criteria were given information about the study. Those who expressed interest about the study either contacted the research team directly or provided consent to be contacted, in which case a research assistant contacted the individual to provide study information and answer questions. A trained researcher then met with the volunteer participants at a location of their convenience, and explained and administered all measures in a 60- to 90-minute session. The ethics boards from the relevant institutions approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

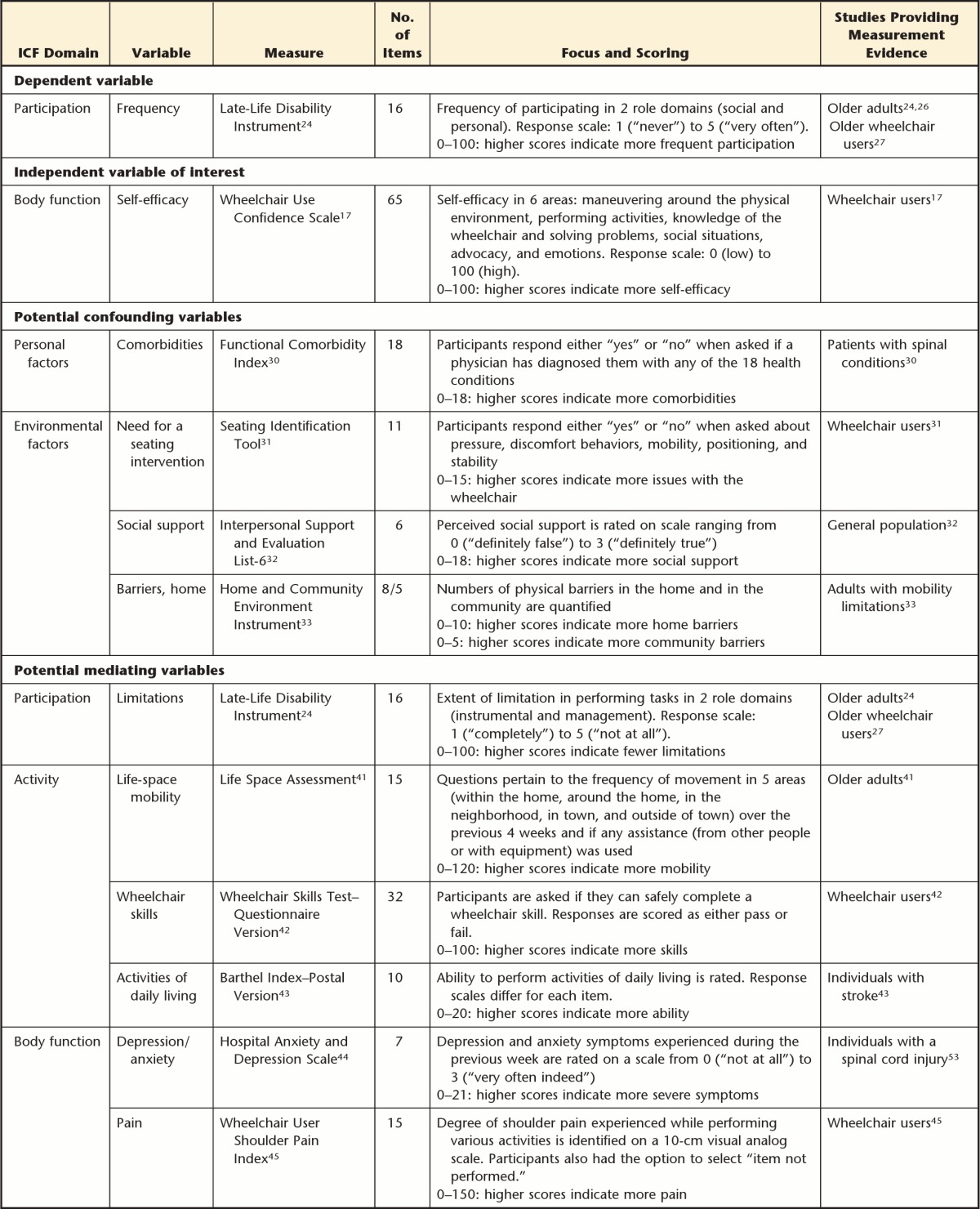

Variables and measures were selected based on either empirical or conceptual rationale. The properties of all measures used in this study have been evaluated with wheelchair users and/or older adults, and are detailed and classified by the ICF domains in Table 1. For measures not available in French, 2 bilingual researchers and a professional translator forward- and back-translated the measures. We followed Vallerand's international standards for the transcultural validation of questionnaires.22,23

Table 1.

Variables and Measures Organized by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

Dependent variable–participation domain.

Participation was measured using the 16-item frequency dimension in the Late-Life Disability Instrument (LLDI).24 Individuals rate their participation frequency in social and personal roles using a response scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“very often”). Item responses are summed to derive a raw total score, which is then standardized into a score ranging from 0 to 100.24 Higher scores indicate more frequent participation. Scores of 51.4 or less are considered low participation frequency in older adult populations.25 Validity testing demonstrated that LLDI total scores differentiate among older adults assigned to 4 functional levels24 and are moderately correlated with scores on the London Handicap Scale (r=.47).26 The measure has been shown to be reliable for use with adult wheelchair users (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]=.86; 95% CI=.76, .93).27

Independent variable of interest–body function domain.

The self-efficacy with wheelchair use construct was measured using the 65-item Wheelchair Use Confidence Scale (WheelCon).17 This measure assesses self-efficacy in 6 conceptual areas: maneuvering around the physical environment, performing activities, knowledge and problem solving, social situations, advocacy, and emotions. Items are rated on a scale of 0 to 100. A mean score is calculated, with higher scores indicating more self-efficacy.17 This measure has construct validity, with excellent test-retest reliability (ICC=.84; 95% CI=.70, .92) demonstrated in a sample of community-dwelling manual wheelchair users (age range=31–60 years).17

We categorized the self-efficacy construct as a body function for several reasons. A key conceptual difference between body function and personal factor variables in the ICF is that variables are viewed as a body function when they are influenced by health or disabling conditions.28 Conversely, personal factor variables have nothing to do with or are not caused by the health condition.1 Rather, they are long-standing attributes individuals display over time regardless of health or functional status. Therefore, in the context of self-efficacy with wheelchair use, because it is a state and has the potential to be influenced by a number of events, including health and disability,14 it was specified as a body function.

Potential confounding variables–health, environmental, and personal domains.

A confounding variable must be a risk factor for the outcome, cannot be an intervening or mediating variable, and must be associated with the key independent variable of interest.29(pp132–134) In this study, all potential confounders were health-related, personal, or environmental contextual factors, as per the ICF.

Data for health (eg, diagnosis), personal (eg, age, sex), and wheelchair-related environmental factor (eg, hours of daily use) variables were collected using a sociodemographic information form. Number of comorbidities, need for a seating intervention, and perceived social support were captured with the Functional Comorbidity Index,30 the Seating Identification Tool,31 and the Interpersonal Support and Evaluation List–6,32 respectively. Physical environmental barriers were captured using the Home and Community Environment Instrument.33 Table 2 lists all confounding variables tested, organized by ICF domain.

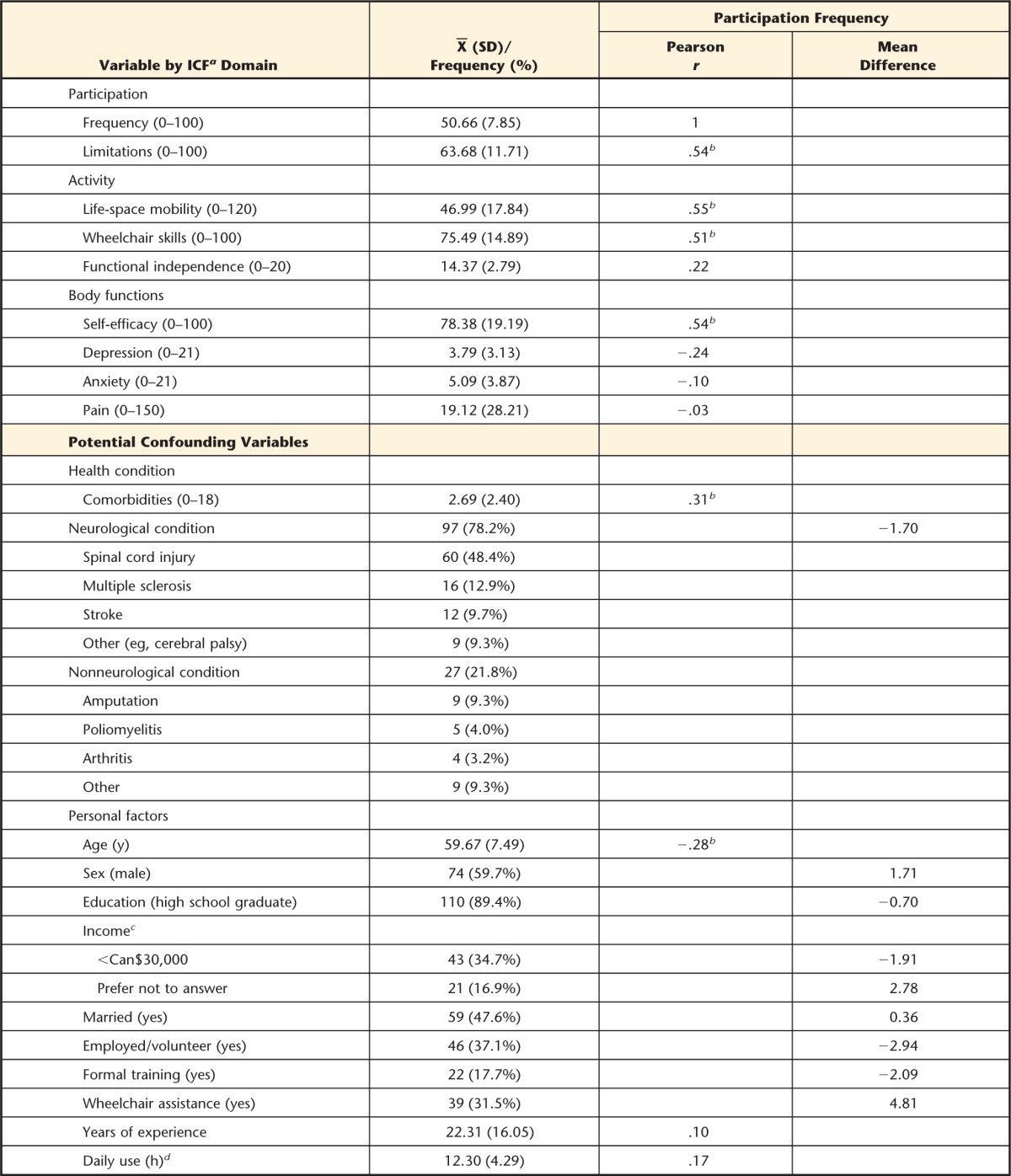

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations With Mean Differences in Participation Frequency (N=124)

a ICF=International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

b Included for modeling.

c Mean difference from ≥30,000.

d n=123.

Potential mediating variables–body function, activity, and participation domains.

Mediating variables help to explain why hypothesized associations exist.34 An important difference between mediators and confounders is that mediators are intervening or causal variables, and confounders are not. That is, an independent variable may have an indirect influence on an outcome through a mediating variable.34 In this study, mediators were selected on the basis of existing evidence showing them to both influence participation12,35–37 and be influenced by self-efficacy14,38–40 in various populations. The life-space mobility12,38 of wheelchair users was evaluated with the Life-Space Assessment.41 The Wheelchair Skills Test–Questionnaire Version42 assessed wheelchair skills.12,14 The Barthel Index,43 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,44 and Wheelchair User Shoulder Pain Index45 measured ability to perform activities of daily living,35,40 depression and anxiety symptoms,12,14,39 and shoulder pain,14,39 respectively. The perceived participation limitations14,37 variable was quantified using the 16-item limitations dimension of the LLDI.24

Data Analysis

A sample size of 122 was determined by G*Power (G*Power, http://www.gpower.hhu.de) to have 80% power to detect significance in a model with 9 independent variables using an alpha of .05 and a moderate effect size (f2=0.14). An effect size46 was calculated using the R2 increase (10%) reported in a previous study of wheelchair users.19 After completing the sociodemographic information form, the Mini-Mental State Examination, and the WheelCon, the remaining measures were administered in a random sequence to minimize response bias. Data from British Columbia and Quebec were combined for analyses because the mean difference in the dependent variable was less than the LLDI's 95% minimal detectable change observed in wheelchair users of 7.18,27 indicating no difference in participation frequency.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. Results from categorical variables were calculated as percentages, and results from continuous variables were calculated as means and standard deviations. Income was collapsed into 3 categories using the median Can$30,000 as a cutpoint, in addition to the “prefer not to answer” category. The following variables were dichotomized and coded as −0.5 (no) or 0.5 (yes)47: diagnosis (neurological condition), education (high school graduate), formal wheelchair skills training; assistance with wheelchair use (eg, supervision, transfers), married or common law, and employed or volunteer. Regression modeling was used to establish the direct and mediated self-efficacy effects on participation frequency.

Direct Effect of Self-efficacy on Participation Frequency

To establish a valid and precise estimate of the direct effect, we followed Kleinbaum's 3-stage modeling strategy to develop a valid regression model.48(pp169–173),49(pp189–204) In the first stage, potential confounding variables and interaction terms were specified for modeling. Data were collected for 16 potential confounders (Tab. 2). Only those continuous variables with a fair relationship (ie, r≥.2550(p525)) with participation frequency or those categorical variables with a mean difference in participation frequency that exceeded the LLDI's 95% minimal detectable change27 were included in the model. To minimize collinearity, all continuous variables were mean centered. However, when potential collinearity was identified (ie, r≥.70 among independent variables, with a variation inflation factor value greater than 1049(p315)), the measure with the highest correlation with the dependent variable was selected unless there was a theoretical rationale to choose one variable over another or to retain both. Finally, we included 2 interaction terms (ie, self-efficacy × sex and self-efficacy × age) to determine whether the relationship between self-efficacy and participation frequency differs by sex and age, which is in accordance with social cognitive theory14 and existing evidence.19 After specifying variables for modeling, all regression assumptions were tested.49(pp45–48)

In the second modeling stage, we tested the statistical significance of the interaction terms.48(pp207–210) After forcing the self-efficacy variable and the lower order components of each interaction term into the model, the statistical significance (P<.05) of the interaction terms were evaluated using both forward selection and backward elimination regression approaches. The result of this analysis was considered the crude model for the next modeling stage.

In the final stage of model development, we assessed for confounding.48(pp211–215) Confounding refers to the association of interest having a meaningfully different interpretation when potential confounding variables are ignored (ie, crude model) or included in the model (ie, adjusted model).49(p190) We considered a change in the unstandardized self-efficacy regression coefficient in the adjusted model, relative to the estimate in the crude model, that exceeded 10%29(pp261–262),51 to be indicative of confounding.

If the adjusted model indicated confounding, subsequent analyses were performed to identify subsets of the confounding variables that provide equivalent control of confounding, but with a more precise self-efficacy estimate. Precision was evaluated by examining the width of the 95% CI around the self-efficacy estimate. A narrowing of the 95% CI indicated improved precision.49(p201) The model with equivalent control of confounding, relative to the adjusted model, and the narrowest 95% CI was deemed to provide the most valid and precise estimate of the direct effect of self-efficacy on participation frequency. This model was used in the mediator analyses.

Mediated Effects of Self-efficacy on Participation Frequency

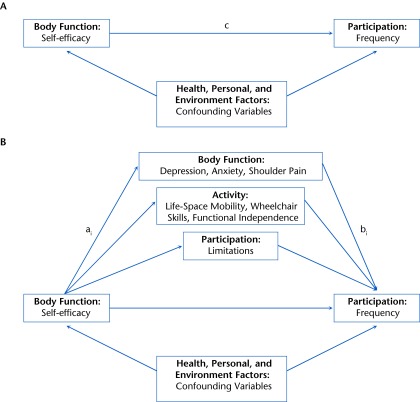

Because multiple variables were hypothesized as mediators, we tested a single multiple mediation model34 in lieu of separate simple models. Path c in Figure 1A depicts the direct effect of self-efficacy on participation frequency after controlling for confounders. Figure 1B represents the mediated effects via the 7 possible mediators. For mediators to be included in the model, they had to have at least a fair correlation magnitude (ie, r≥.2550(p525)) with participation frequency. A bias-corrected bootstrapping method was used to derive the point estimates for the total and individual mediation effects and 95% CI values.34 The proportion of the direct effect accounted by the mediators was calculated as:

|

We used SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois), G*Power version 3.1.3, and the INDIRECT macro34 for the analyses.

Figure.

Diagrams showing the direct and mediated paths of self-efficacy on participation: (A) direct effect (path c) of self-efficacy with using a manual wheelchair on participation frequency while controlling for health, personal, and environmental confounding variables and (B) mediated effect (paths ai and bi) of self-efficacy with using a manual wheelchair on participation frequency after controlling for health, personal, and environmental confounding variables.

Role of the Funding Source

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Operating Grant IAP-107848 and Doctoral Scholarship to Dr Sakakibara) and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (Senior Scholar Award to Dr Eng).

Results

Seventy-four individuals from British Columbia and 50 individuals from Quebec were enrolled. The mean age of the total sample was 59.67 years (SD=7.49), and 74 (59.7%) were male. The majority of the participants reported having a neurological condition (78.2%), with just under half reporting a spinal cord injury (48.4%). Participants reported few comorbid conditions (X̅=2.69, SD=2.40) and low severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Individuals were experienced with using their wheelchair (X̅=22.31 years, SD=16.05) and had a mean wheelchair skills level of 75.5% (SD=14.89). The sample's mean LLDI score was low (X̅=50.66, SD=7.85). Sample characteristics are further detailed in Table 2.

Direct Effect of Self-efficacy on Participation Frequency

Pearson correlation coefficients between the continuous independent and dependent variables are presented in Table 2, along with the mean difference in the dependent variable for the dichotomized variables. Variables specified for inclusion into the regression model included age, number of comorbidities, perceived social support, and the age and sex interaction terms. All model assumptions were met.

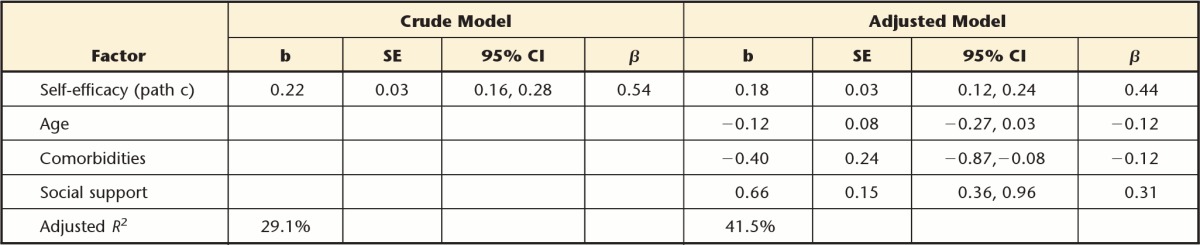

After entering the self-efficacy, age, and sex variables into the model, neither the age nor the sex interaction term reached statistical significance. The crude model (Tab. 3), therefore, included the self-efficacy variable, which accounted for 29.1% of the participation frequency variance.

Table 3.

Direct Effect of Self-efficacy on Participation Frequencya

b=unstandardized regression coefficient, SE=standard error, 95% CI=95% confidence interval, β=standardized regression coefficient, path c=direct effect of self-efficacy on participation frequency.

In the adjusted model (Tab. 3), the self-efficacy estimate was confounded by 18.2% after controlling for age, number of comorbidities, and perceived social support. This model accounted for 41.5% of the participation frequency variance (17.2% by the self-efficacy variable). It also was deemed the most valid and precise estimate of the self-efficacy effect on participation frequency because other confounder subsets provided neither equivalent control of confounding nor a more precise estimate.

Mediated Effect of Self-efficacy on Participation Frequency

Three mediators were identified for analyses: life-space mobility, wheelchair skills, and participation limitations. Although the correlation between wheelchair skills and self-efficacy (r=.84) indicated potential collinearity, we chose to retain both variables in the model because the variation inflation factor value (ie, 3.78) indicated no need for corrective action and because, according to social cognitive theory, a causal path exists in which higher levels of self-efficacy may lead to better abilities through various processes.14 For example, individuals with higher levels of self-efficacy are more likely to develop better abilities than individuals with lower self-efficacy because they will exert greater levels of perseverance to overcome challenges and impediments.14 The total mediated effect was statistically significant (point estimate=0.14, 95% bootstrapped CI=0.04, 0.24) (Tab. 4) and accounted for 78.0% of the direct effect on participation frequency. This mediation model accounted for 55.0% of the variance. Subsequent examination of the specific indirect effects revealed that the wheelchair skills variable was not a statistically significant mediator because the 95% CI included 0 and, therefore, did not contribute to the total indirect effect above and beyond life-space mobility and participation limitations (see Tab. 4 for the magnitude of each mediation effect).

Table 4.

Mediated Effect of Self-efficacy on Participation Frequencya

Path ai=associations between self-efficacy and the mediators, path bi=associations between the mediators and participation frequency, aibi=magnitude of each mediated effect, 95% CI=95% confidence interval.

b 1,000 bootstrap samples.

Discussion

This study's findings provide evidence in support of our hypothesis that self-efficacy has important implications for the participation frequency of community-dwelling manual wheelchair users aged 50 years or older. Social cognitive theory explains that self-efficacy is at the foundation of human motivation and action.14 Therefore, our results suggest that if people believe they can produce desired effects by their actions while using their wheelchair, they have greater incentive to participate in personal and social roles more frequently. When considering that the mean participation frequency score in this study's sample was low despite being in good health (ie, individuals reported few number of comorbidities and low severity of depression and anxiety symptoms), improvements to self-efficacy with using a wheelchair may result in notable participation and quality-of-life outcomes.

Our results substantiate preliminary findings that illustrated the importance of the self-efficacy construct on participation frequency.19 However, the findings contrast in that we observed no difference in the magnitude of the association by sex. This disagreement may have been due to the larger sample size used in this study, which allowed for more robust analyses such as controlling for additional confounders. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that strategies to improve low self-efficacy may have beneficial effects on participation frequency regardless of sex. More research is needed to investigate the differences by sex.

Finding that the self-efficacy term remained a statistically significant determinant of participation frequency after examining for interaction and confounding effects has both clinical and research implications. Because low self-efficacy may present as a barrier to participation frequency, clinical trials are justified to develop and test self-efficacy–enhancing interventions. According to Bandura,14 low self-efficacy is an amenable condition influenced by a variety of social cognitive means. In a pilot study of older individuals who were inexperienced with using a wheelchair, the researchers demonstrated positive effects of wheelchair skills training on self-efficacy with using a manual wheelchair.20

In a recent study, Phang et al52 examined self-efficacy as a mediator in the relationship between wheelchair skills and participation in leisure-time physical activity in younger manual wheelchair users (ie, mean age ≤50 years) with spinal cord injuries. Contrary to our findings, they found an absence of an association between self-efficacy and participation after controlling for skills and, therefore, demonstrated no mediating effect. A reason for this discrepancy relative to our findings is likely in how self-efficacy was measured. Their study assessed the self-efficacy construct with items in the WheelCon only pertaining to moving around the physical environment. Our findings may reflect the multifaceted nature of participation being accounted for by the different conceptual areas comprising the entire scale that was used in this study. We also differed in our modeling approach. Whereas they investigated self-efficacy as a mediator, we specified wheelchair skills to mediate the association between self-efficacy and participation. The use of situation-specific self-efficacy measures is in accordance with theory, as is the functional form of our model.14

The results from the mediation analyses also support our hypothesis that the association between self-efficacy and participation frequency is mediated by multiple functioning and disability variables. The results of the analyses suggest a causal direction in which higher levels of self-efficacy act to improve life-space mobility and perceptions about participation limitations, which—in turn—lead to more frequent participation. Therefore, efficacy-enhancing interventions targeted toward improving all of life-space mobility and participation limitations may be more beneficial than unilateral approaches at improving participation frequency. Clinical trials investigating the causal nature of self-efficacy are needed to corroborate our observations, as is research into the specific relationships between self-efficacy and the mediators.

Limitations

Although causality cannot be established due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, our findings are in agreement with both theory and a large body of research demonstrating the beneficial effects of enhanced self-efficacy on various outcomes and the expected relationships between our hypothesized mediators and participation. Next, we considered only 2-way interaction terms in order to keep the models hierarchically well-formulated. Although lower-order interactions minimize collinearity, the sample size limited our ability to evaluate possible higher-order interactions that included province. Furthermore, the self-report nature of our data from the use of questionnaires and a volunteer sample may be influenced by selection and measurement bias or social desirability, or both. As a result, the volunteer sample may not accurately represent the population as a whole.

Conclusion

Self-efficacy with using a manual wheelchair has both direct effects on the participation frequency of community-dwelling manual wheelchair users aged 50 years or older and statistically significant indirect effects through life-space mobility and participation limitations. Self-efficacy is an important construct to consider in the study of wheelchair users' participation, and the development of interventions to address low self-efficacy with wheelchair use is warranted.

Footnotes

All authors provided concept/idea/research design. Dr Sakakibara, Dr Miller, and Dr Eng provided writing and project management. Dr Sakakibara and Dr Routhier provided data collection and study participants. Dr Sakakibara, Dr Miller, and Dr Backman provided data analysis and consultation (including review of manuscript before submission). Dr Miller provided fund procurement. Dr Sakakibara and Dr Miller provided facilities/equipment and clerical support.

The results of this study were presented at the 65th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America; November 14–18, 2012; San Diego, California.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Operating Grant IAP-107848 and Doctoral Scholarship to Dr Sakakibara) and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (Senior Scholar Award to Dr Eng).

References

- 1. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization: 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ravenek KE, Ravenek MJ, Hitzig SL, Wolf DL. Assessing quality of life in relation to physical activity participation in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Disabil Health J. 2012;5:213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McLean AM, Jarus T, Hubley AM, Jongbloed L. Associations between social participation and subjective quality of life for adults with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2013. September 23 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.834986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Siebens H. Mobility difficulties are not only a problem of old age. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:235–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Satariano WA, Guralnik JM, Jackson RJ, et al. Mobility and aging: new directions for public health action. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1508–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilkie R, Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P. The prevalence of person-perceived participation restriction in community-dwelling older adults. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1471–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Best KL, Miller WC. Physical and leisure activity in older community-dwelling Canadians who use wheelchairs: a population study. J Aging Res. 2011. April 13 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.4061/2011/147929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shields M. Use of wheelchairs and other mobility devices. Health Rep. 2004;15:37–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. LaPlante MP, Kaye HS. Demographic trends in wheeled mobility equipment use and accessibility in the community. Assist Technol. 2010;22:2–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hosseini SM, Oyster ML, Kirby RL, et al. Manual wheelchair skills capacity predicts quality of life and community integration in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:2237–2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kilkens OJ, Post MW, Dallmeijer AJ, et al. Relationship between manual wheelchair skill performance and participation of persons with spinal cord injuries 1 year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(3 suppl 1):65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mortenson WB, Miller WC, Backman CL, Oliffe JL. Association between mobility, participation, and wheelchair-related factors in long-term care residents who use wheelchairs as their primary means of mobility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1310–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ginis KA, Latimer AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, et al. Leisure time physical activity in a population-based sample of people with spinal cord injury, part I: demographic and injury related correlates. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:722–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: Freeman; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller WC, Deathe AB, Speechley M, Koval J. The influence of falling, fear of falling and balance confidence on prosthetic mobility and social activity among individuals with a lower extremity amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1238–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anaby D, Miller WC, Eng JJ, et al. ; PACC Research Group. Can personal and environmental factors explain participation of older adults? Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:1275–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rushton PW, Miller WC, Kirby RL, Eng JJ. Measure for the assessment of confidence with manual wheelchair use (WheelCon-M) version 2.1: reliability and validity. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45:61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller WC, Sakakibara BM, Rushton PW. The prevalence of low confidence with using a wheelchair and its relationship to wheelchair skills. Gerontologist. 2012;52(suppl 1):205 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sakakibara BM, Miller WC, Eng JJ, et al. Preliminary examination of the relationship between participation and confidence in older manual wheelchair-users. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:791–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sakakibara BM, Miller WC, Souza M, et al. Wheelchair skills training to improve confidence with using a manual wheelchair among older adults: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:1031–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vallerand R. Vers une méthodologie de validation trans-culturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: implications pour la recherche en langue française. Can Psychol. 1989;30:662–680 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3186–3191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jette AM, Haley SM, Coster WJ, et al. The Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument, I: development and evaluation of the disability component. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M209–M216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keysor JJ, Jette AM, LaValley MP, et al. ; Multicenter Osteoarthritis (MOST) Group. Community environmental factors are associated with disability in older adults with functional limitations: the MOST study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:393–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dubuc N, Haley SM, Ni P, et al. Function and disability in late life: comparison of the Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument to the Short-Form-36 and the London Handicap Scale. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:362–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sakakibara BM, Routhier F, Lavoie MP, Miller WC. Reliability and validity of the French-Canadian version of the Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI-F) in older, community-living wheelchair-users. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:365–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Threats T. Access for persons with neurogenic communication disorders: influences of personal and environmental factors of the ICF. Aphasiology. 2007;21:67–80 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, et al. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:595–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller WC, Miller F, Trenholm K, et al. Development and preliminary assessment of the measurement properties of the Seating Identification Tool (SIT). Clin Rehabil. 2004;18:317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cohen S, Hoberman H M. Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1983;12:99–125 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Keysor JJ, Jette AM, Haley SM. Development of the Home and Community Environment (HACE) instrument. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res. 2008;40:879–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Leeuwen CM, Post MW, Westers P, et al. Relationships between activities, participation, personal factors, mental health, and life satisfaction in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:82–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kemp BJ, Bateham AL, Mulroy SJ, et al. Effect of reduction in shoulder pain on quality of life and community activities among people living long-term with SCI paraplegia: a randomized control trial. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:278–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barker DJ, Reid D, Cott C. The experience of senior stroke survivors: factors in community participation among wheelchair users. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;73:18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pang MY, Eng JJ. Fall-related self-efficacy, not balance and mobility performance, is related to accidental falls in chronic stroke survivors with low bone mineral density. Osteopor Int. 2008;19:919–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pang MY, Eng JJ, Lin K-H, et al. Association of depression and pain interference with disease-management self-efficacy in community-dwelling individuals with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:1068–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rejeski WJ, Miller ME, Foy C, et al. Self-efficacy and the progression of functional limitations and self-reported disability in older adults with knee pain. J Gerontol B Pysch Sci Soc Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:S261–S265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baker PS, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Measuring life-space mobility in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1610–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wheelchair Skills Program Manual. Version 4.1. 2008. Dalhousie University (online) Available at: http://www.wheelchairskillsprogram.ca Accessed February 9, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gompertz P, Pound P, Ebrahim S. A postal version of the Barthel Index. Clin Rehabil. 1994;8:233 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Curtis KA, Roach KE, Applegate EB, et al. Development of the Wheelchair User's Shoulder Pain Index (WUSPI). Paraplegia. 1995;33:290–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Norman GR, Streiner DL. Biostatistics: The Bare Essentials. 3rd ed Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: BC Decker Inc; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Logistic Regression: Statistics for Biology and Health. 3rd ed New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariate Methods. 4th ed Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. 3rd ed Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tong IS, Lu Y. Identification of confounders in the assessment of the relationship between lead exposures and child development. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:38–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Phang SH, Martin-Ginis KA, Routhier F, et al. The role of self-efficacy in the wheelchair skills-physical activity relationship among manual wheelchair-users with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:625–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sakakibara BM, Miller WC, Orenczuk SG, et al. A systematic review of depression and anxiety measures used with individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:841–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]