Abstract

Background

Ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm (ATAA) predisposes patients to aortic dissection and has been associated with diminished tensile strength and disruption of collagen. ATAA arising in patients with bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) develop earlier than those with tricuspid aortic valves (TAV) and have a different risk of dissection. The purpose of this study was to compare aortic wall tensile strength between BAV and TAV ATAAs and determine if the collagen content of the ATAA wall is associated with tensile strength and valve phenotype.

Methods

Longitudinally and circumferentially oriented strips of ATAA tissue obtained during elective surgery were stretched to failure and collagen content was estimated by hydroxyproline assay. Experimental stress-strain data were analyzed for failure strength and elastic mechanical parameters: α, β and maximum tangential stiffness.

Results

The circumferential and longitudinal tensile strengths were higher for BAV ATAA when compared with TAV ATAA. The α and β were lower for BAV ATAA when compared with TAV ATAA. The maximum tangential stiffness was higher for circumferential when compared with longitudinal orientation in both BAV and TAV ATAA. Amount of hydroxyproline was equivalent in BAV and TAV ATAA specimens. While there was a moderate correlation between the collagen content and tensile strength for TAV, this correlation is not present in BAV.

Conclusion

The increased tensile strength and decreased values of α and β in BAV ATAAs despite uniform collagen content between groups indicate that micro-structural changes in collagen contribute to BAV-associated aortopathy.

Keywords: Aorta/aortic, Bioengineering, Aneurysm (thoracic ascending), in vitro studies

Introduction

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is the most common congenital heart malformation occurring in 1–2% of the population and is associated with ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm (ATAA) formation and a significantly greater risk of aortic valve disease than the general population[1, 2]. ATAAs progress to aortic dissection, rupture and sudden death. Current expert surgical consensus concludes that patients with ATAA should undergo prophylactic surgery when the maximum orthogonal diameter is 48–55 mm depending on several risk factors[3]. In certain high risk populations, such as patients with BAV, ATAA have been known to dissect at smaller diameters[4] suggesting that diameter may not be the best predictor of aortic catastrophe. Alternatively, because aortic dissection or disruption is a biomechanical phenomenon, mechanical models should be developed to better predict risk of aortic catastrophe.

Although the mechanical properties of abdominal aortic aneurysm have been widely studied, data for ATAA is significantly more limited. Okamoto et.al demonstrated nonlinear behavior of ATAA under biaxial testing and a decrease in distensibility with age.[5] Our laboratory previously reported directional strength differences of ATAA compared to normal non-aneurysmal aorta[6]. Iliopoulos et.al reported both regional and directional variations of strength and stiffness in ATAAs [7]. Choudhury et.al, reported local stiffness changes from biaxial tests for ATAAs [8]. To our knowledge, no information on aortic wall mechanical strength of ATAA with respect to valve phenotype has been reported.

Mechanical behavior of the aortic wall depends on extracellular matrix (ECM) structure and composition. Elastin and collagen determine the mechanical properties of the aortic wall, with distensibility primarily depending on elastin, and peak aortic stiffness and tensile strength provided by collagen [9]. The role of collagen content in ATAA development remains unclear as some investigators have reported no differences in the elastin and collagen content of aneurysmal wall tissues between patients with BAV and patients with tricuspid aortic valves (TAV) [10, 11], while others have observed regionally reduced collagen expression [12]. No previous studies examined the relationship between the ECM and the mechanical properties of ATAA, or whether there is difference due to aortic valve morphology.

The purpose of this study was 1) to determine whether there is a difference in wall tensile strength between BAV and TAV ATAAs and 2) to determine the relative collagen content within ATAA wall and its relationship to mechanical properties of the two aortic valve phenotypes.

Material and Methods

Tissue Harvest

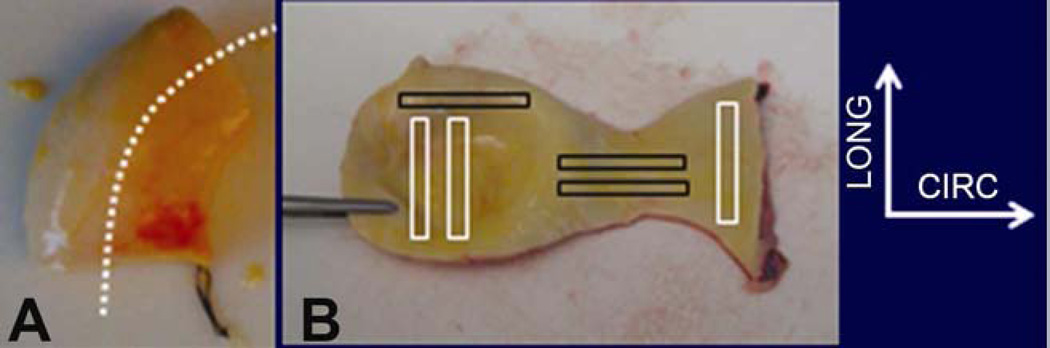

Whole, fresh, non-dissecting ascending aortic specimens were harvested as an intact tubular structure (Figure 1A) from patients with BAV (aged 54 ± 4 years; diameter, 50 ± 5 mm, mean ± S.D) (n=23) and TAV (aged 66 ± 11 years; diameter, 57 ± 14mm, mean ± S.D) (n=15) undergoing elective surgery. All tissues were excised following informed patient consent in accordance with a study protocol approved by our Institutional Review Board. The tissue was harvested from above the sinuses of Valsalva with proximal/distal orientation noted by the surgeon, immersed in saline and kept refrigerated at 4° C until testing. Patient demographics were obtained from clinical records. The maximum diameter of each ATAA was determined via computed tomography.

Figure 1.

A. Representative image of tubular ATAA tissue harvested. Suture indicates proximal end and a tentative aorta axis is drawn in white dotted line. B. Tubular tissue is cut open and rectangular pieces of circumferentially (CIRC) and longitudinally (LONG) oriented specimens were harvested for tensile testing.

Tensile Testing

ATAA tissues were tested within 48 hours of harvest. The ATAAs were prepared by first removing the adipose tissues and then dissecting circumferentially (CIRC) and longitudinally (LONG) oriented strip specimens (Figure 1B). Specimen width and thickness were measured at three different locations using a caliper (Scienceware, Wayne, NJ, USA) and then averaged. Both ends of each strip were sandwiched between the clamps using sand paper and cyanoacrylate glue. The clamps were then mounted in a custom-built uniaxial tensile testing machine [13] with a 25 lb load cell and amplifier (Transducer Techniques, Temecula, CA, USA), and LabVIEW 7.1 (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). The specimen was slowly stretched until a small increase in load was observed and initial specimen length was noted. The specimens were preconditioned and then stretched until specimen failure as described previously [13]. The applied force and corresponding displacement were collected synchronously and continuously at the sampling rate of 10 Hz until specimen failure.

Biomechanical Data Analysis

As described previously [13], stress and strain were calculated from force-displacement data and initial specimen dimensions. Briefly, the Cauchy stress (T) within the specimen was calculated as the applied force normalized by deformed cross-sectional area, and the strain (ε) was calculated as deformation normalized by original specimen length. The maximum tangential stiffness (MTS) was taken as the maximum slope (i.e., maximum resistance to deformation), while the tensile strength was taken as the peak stress obtained before failure from the stressstrain curve [6].

We used our prior model to further characterize the biomechanical response of the aneurysm wall [14]. The model relates the stress in a uniaxial loaded specimen to the stretch (λ = ε + 1) through the equation

| (1) |

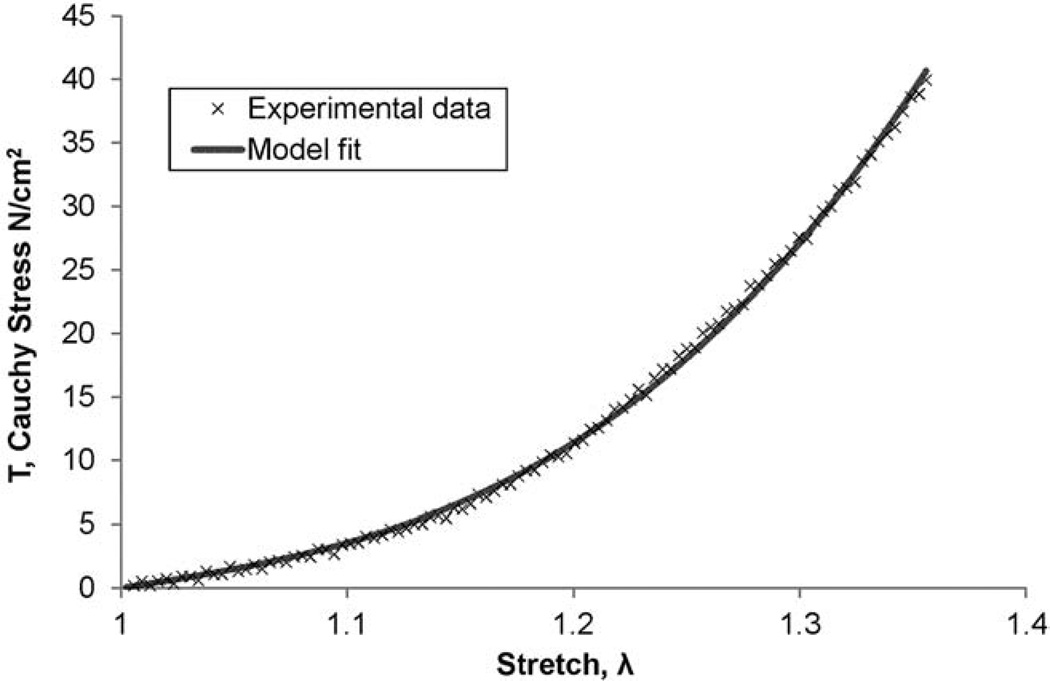

where, α and β are model parameters indicative of the mechanical properties of the tissue. The mathematical model was fit to the elastic region of each experimentally derived T − λ data sets (i.e., before yield) using the Marquardt-Levenberg least squares nonlinear regression algorithm in Sigma Plot 11.0 (Systat Software, Inc. San Jose, CA, USA). A representative model fit for stress-stretch data (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A representative fit of the model given by equation (1) to the experimental stress-stretch data obtained from the tensile testing of an ATAA tissue specimen. This particular data is from a LONG oriented specimen of an ATAA with BAV.

Collagen content assessment

a. Trichrome Staining

Aortic specimens (~1 × 0.5 cm2) were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and paraffin embedded. Four micron sections were stained using Masson’s trichrome (Research Histology Services, University of Pittsburgh Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute) to qualitatively assess collagen composition. Slides were visualized using a Nikon TE-2000-E inverted microscope and captured using a Nikon DS-Fi1 5MP color camera and NIS Elements Software (Nikon, USA).

b. Hydroxyproline

Total collagen content was determined for a subset of samples from each group using a modification of a hydroxyproline (HYP) assay [15, 16]. After tensile testing, a small portion of flanking tissue (50–100 mg) from both sides of the failure region was minced (~1×1 mm) specimens (n=49 for BAV; n=26 for TAV) and lyophilized. Specimens were flame-sealed in 10mm Pyrex tubes with 100µl of 6N HCl containing 0.5% (v/v) phenol and incubated at 110°C for 24 hours and dried under vacuum. The dried sample was re-suspended with 1% (v/v) HCl, incubated at 50°C, and then neutralized with an equivalent amount of NaOH. Chloramine T reagent (0.056M) was added, followed by incubation at room temperature for 25 min. Freshly-prepared Ehrlich’s reagent (1M) was added followed by incubation at 65°C for 20 min. Absorbance of replicates was measured at 550nm in a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M2, Model# D02667, Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA). Experimental hydroxyproline levels were normalized to the mass (g) of dry tissue.

Statistical analysis

All data is presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t test was performed to compare the mean values between the groups using Sigma Plot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc, Chicago, IL). Significance was assumed for a p value of less than 0.05.

Results

A total of 23 ATAA with BAV and 15 ATAA with TAV were included in this study. The average maximal orthogonal diameter of the aorta was 50 ± 5 mm for BAV vs. 57 ± 14mm for TAV(p=0.15). There was a difference in age between the group means (54 ± 4 years for BAV vs. 66 ± 11 years for TAV; p<0.01). The age discrepancy noted is consistent with the clinical observation that BAV ATAAs present 10–20 years earlier than patients with TAV and ATAA[17]. From these ATAAs, 178 samples were tensile tested. 15 of those were either slipped or broke at the clamp hence discarded from data analysis. There was no significant difference between the tensile test data normalized per patient and the un-normalized data of all specimens averaged for the study group. Hence un-normalized values averaged for the whole group is reported here.

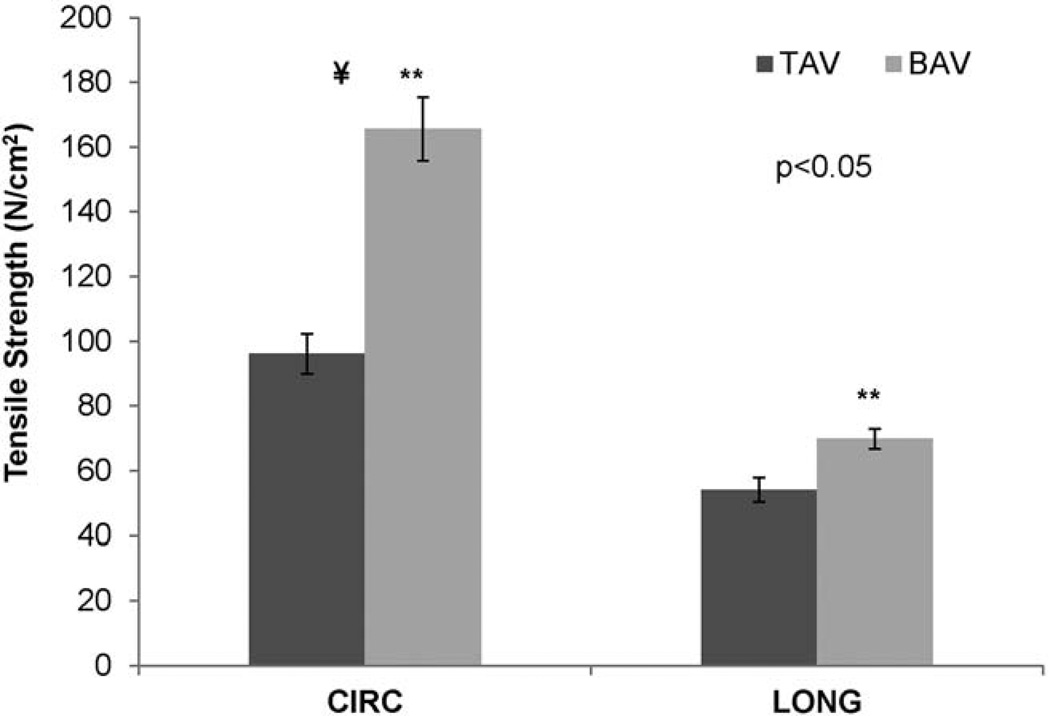

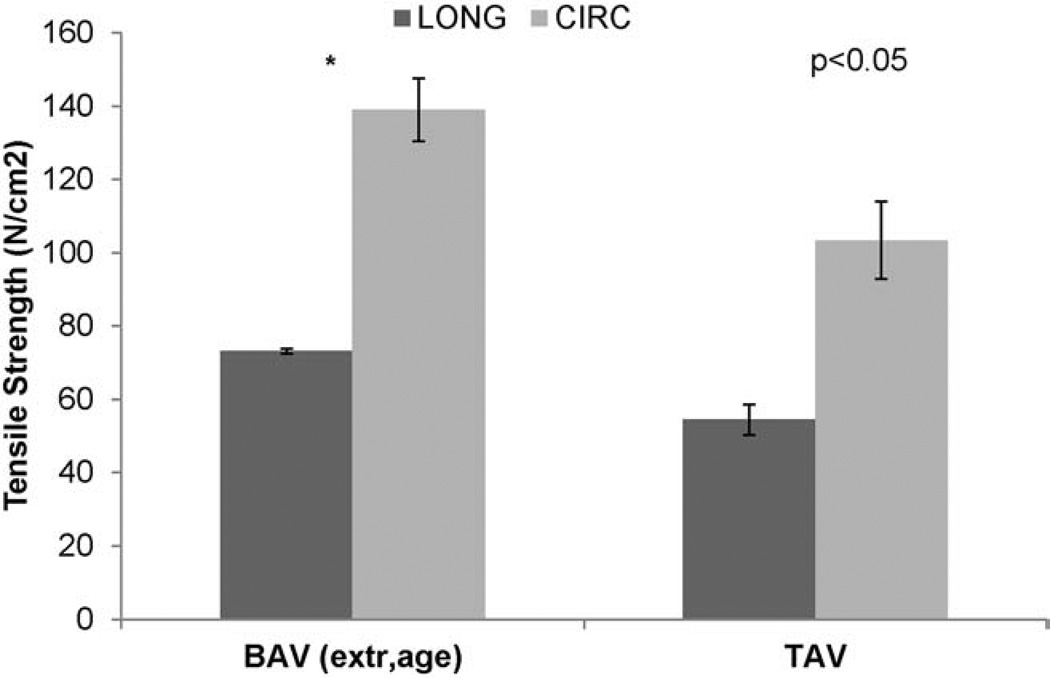

For BAV tissues, the CIRC and LONG tensile strengths were 165.6±9.8 N/cm2 and 69.8±3.1 N/cm2, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 3). For TAV, these were 96.1±6.1 N/cm2 and 54.0±3.7 N/cm2, respectively. In both BAV and TAV, the CIRC oriented samples were stronger than LONG orientation samples (p<0.05), and the strength of BAV was stronger than TAV in both orientations (p<0.05). The average percentage of failure strain for BAV in CIRC and LONG orientations are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biomechanical properties and hydroxyproline values assessed for BAV and TAV

| α | β | MTS | Failure Strain (%) | Tensile Strength | HYP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAV CIRC | 6.8 ± 2.3 | 71.0 ± 22.2 | 335.1 ± 22.2 a | 60.7 ± 4.1 a | 96.1 ± 6.1 a | 19.0 ± 1.5 (all TAV) |

| TAV LONG | 6.2 ± 0.8 b | 120.0 ± 31.5 b | 220.7 ± 20.3 | 46.9 ± 3.1 b | 54.0 ± 3.7 b | |

| BAV CIRC | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 12.3 ± 1.1c | 350.4 ± 16.0 | 91.7 ± 3.7c | 165.6 ± 9.8c | 18.9 ± 1.9 (all BAV) |

| BAV LONG | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 1.8d | 191.6 ± 9.6d | 63.4 ± 2.2d | 69.8 ± 3.1d |

For p-value < 0.05:

TAV CIRC compared to TAV LONG

TAV LONG compared to BAV LONG

BAV CIRC compared to TAV CIRC

BAV LONG compared to BAV CIRC

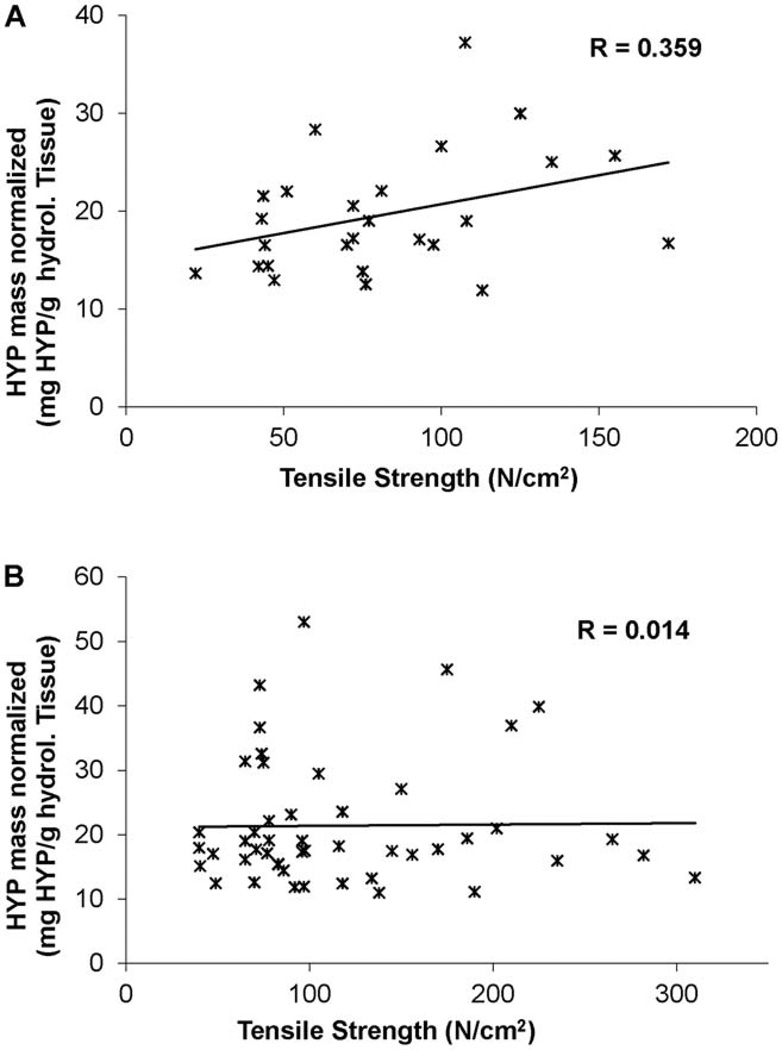

Figure 3.

The average tensile strength of BAV and TAV in CIRC and LONG orientations. ¥The strength of CIRC oriented specimen is significantly higher than LONG oriented specimen for both BAV (p<0.01) and TAV (p<0.01). **BAV is significantly stronger than TAV in both orientations (p<0.01). ATAA=ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm; BAV=bicuspid aortic valve; CIRC=circumferential; LONG=longitudinal; TAV=tricuspid aortic valve.

The MTS of BAV appeared to be higher when compared with TAV CIRC specimens and lower than TAV in LONG (Table 1). In BAV the MTS were 350.4±16.0 N/cm2 and 191.6±9.6 N/cm2 for CIRC and LONG specimens (p<0.05), respectively. Similarly, in TAV the MTS were 335.1±22.2 N/cm2 and 220.7±20.3 N/cm2 for CIRC and LONG specimens (p<0.05), respectively.

The average closeness-of-fit of the biomechanical model described in Equation 1 to the experimental stress-stretch data was found to be greater than 99% (R2 > .99 ± .001). The mean value of α was not significantly different in LONG and CIRC for either BAV or TAV (Table 1; TAV: 6.7± 2.3 N/cm2 versus 6.2±0.8 N/cm2; BAV: 4.8± 0.3 N/cm2 versus 4.5±0.4 N/cm2). However, α is significantly lower in BAV LONG specimens compared to TAV LONG (p<0.05). The β is not significantly different between CIRC and LONG specimens in TAV (Table 1; 71.0±22.2 N/cm2 versus 120.1±31.5 N/cm2, p=0.1), but was significantly different within BAV (12.3±1.1 N/cm2 versus 18.1±1.8 N/cm2, p<0.005). In addition, the β is significantly lower in BAV compared to TAV in both orientations (p<0.005).

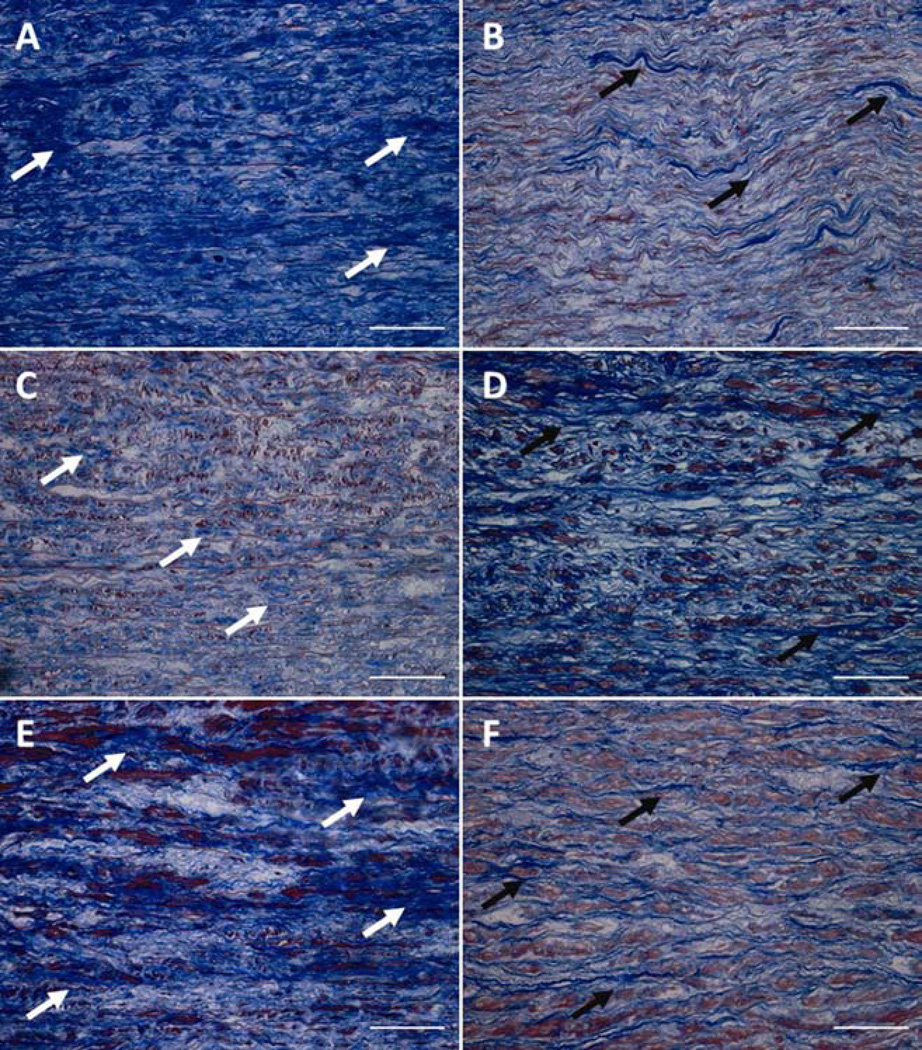

Trichrome staining of ATAAs revealed cystic media degeneration, elastin fragmentation and a disproportionate distribution of collagen among BAV and TAV suggesting increased collagen in BAV (Figure 4). However, there was no difference in HYP for BAV and TAV (18.9±1.9 vs. 19.0±1.5, respectively, p=0.17; Table 1). For TAV, a moderate correlation between the collagen content and tissue strength was demonstrated (R=0.359; Figure 5), but this correlation was not seen in BAV tissues (R=0.014).

Figure 4.

Three representative micrographs of Masson’s trichrome staining of BAV (A, C, E) and TAV (B, D, F) tissues. Note that BAV shows more disrupted collagen (blue color, white arrows). TAV has less collagen (blue color, black arrows), but aligned in orientation. Scale bar= 50 µm. BAV=bicuspid aortic valve; TAV=tricuspid aortic valve.

Figure 5.

Collagen content, as estimated by hydroxyproline, as a function of tensile strength for each TAV (A) and BAV (B) specimen tested. Note a moderate correlation (R = 0.359) between the collagen content and strength for TAV, but not for BAV (R=0.014). BAV=bicuspid aortic valve; HYP=hydroxyproline; TAV=tricuspid aortic valve.

Comment

Aortic dissection and/or rupture represent a mechanical failure of the aortic wall and can occur when aortic wall integrity is altered. Despite a higher percentage of patients with BAV compared to TAV among the aortic dissection population than among the general population [18], no investigation has been done, to our knowledge, on the condition of ATAA wall tensile strength with respect to valve phenotype. This study found differences in the wall strength between ATAAs from BAV and TAV patients. The tensile strength in the CIRC orientation was higher than LONG orientation for both BAV and TAV ATAAs. Tensile strength of BAV ATAAs was higher when compared with that of TAV ATAAs for both the CIRC and LONG orientations. The directional differences in the tensile strength of the ATAA wall is consistent with demonstrated anisotropic nature of the ATAA wall as previously reported by our group and others and is consistent with lower tensile strength of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) and ATAAs when compared with normal aorta [5–7, 19, 20]. Moreover, Iliopoulos et al. reported spatial variation in the material parameters such as strength and stiffness of ATAAs [7].

Our qualitative, histologic observation of increased collagen in BAV compared with TAV (Figure 4) agrees with a prior report from our team which demonstrated elevated Type I collagen mRNA [21], and from data reported by Choudhury et al. [8]. Further, Wang et al. demonstrated increased collagen deposition in aortic dissection.[22] Iliopoulos et al. documented higher levels of collagen histologically in ATAA when compared with normal aorta.[19] On the other hand, our quantitative assessment of collagen content by hydroxyproline assay showed no difference between BAV and TAV which is consistent with reports by Fedak et al. and LeMaire et al. [10, 11] Collectively, these data suggest that differences in mechanical properties are not due to absolute collagen content, but may be accounted for by microstructural changes in the collagen framework within the ECM (i.e. collagen architecture) as we recently revealed in native aortic specimens[23].

Though the tensile strength of BAV is significantly stronger when compared with TAV in both CIRC and LONG orientations, the total HYP was equivalent in both groups. The finding of differential correlation between collagen content and tensile strength in TAV (R=0.359) compared to BAV (R=0.014) may indicate distinguishable architecture. Our finding suggests the proportional differences in tensile strength between BAV and TAV cannot be explained by alterations in total collagen content.

The aortic walls of BAV and TAV exhibit differences in mechanical behavior as characterized by our non-linear elastic biomechanical model. The material parameters α, β represent the initial stiffness of the material in the non-linear stress-stretch curve in elastic region up to MTS for each specimen tested. α represents shear modulus for infinitesimal deformation of structural fibers and β being stiffening parameter or bulk modulus of the tissue. We tested this model to predict which of these two parameters influences the stress-stretch curves with one of the parameters kept constant while varying the other parameter. We found that β influences the model twelve times more than α when the difference in simulated stress for incremental β increase was divided by the difference in stress for the corresponding incremental α increase at the maximum failure stretch of 1.9. For BAV, α is lower by 28% and 26%, in the CIRC and LONG orientations, respectively, and β is lower by 83% and 85%, respectively, when compared with TAV. The fact that α and β were much lower with BAV when compared with TAV indicates that less structural fibers were engaged to bear the initial stretch load in BAV. This low α and β in BAV suggest that collagen may be more coiled or disrupted as microstructural changes of the collagen network within the ECM. β is higher in LONG when compared with CIRC for BAV and TAV. A significantly lower value of β in CIRC for BAV indicates a possibility of immature organization of collagen fibers in CIRC. Furthermore, β within TAV between CIRC and LONG oriented specimens does not vary significantly, suggesting a more mature organization of collagen fibers in both the orientations for TAV which is consistent with our recent observation of increased mature collagen in TAV vs. BAV ATAA [23]. Okamoto et al., reported differences in the properties of BAV and TAV using an exponential constitutive model in biaxial testing which were consistent with reduced α and β in BAV compared to TAV [5]. Previously we reported no difference in α and β between LONG and CIRC of AAA, but ATAAs showed a difference between LONG and CIRC for β [6, 13]. α and β of ATAAs were reduced when compared with AAAs, and for ATAAs the β is higher in LONG (53 N/cm2) than CIRC (17 N/cm2). A similar trend is now observed in BAV and TAV as shown in Table 1. However, the value of β is lower in BAV, and higher in TAV compared to the average for all ATAAs reported earlier in both LONG and CIRC direction. The current data suggests that the ATAA wall material property characteristics are strongly associated with valve phenotype. Equivalent total collagen content despite different biomechanical material parameters suggests there are distinct architectural differences of the ECM in the two phenotypes which impart the mechanical property differences.

Previously, we observed increased MTS in ATAAs when compared to normal aorta[6]. In the current study, we showed that the MTS measured in the failure region is higher in CIRC than LONG for both TAV and BAV which seems contrary to the stiffness measured in the elastic region in both cases. This may be because at higher stretch, all the structural fibers of the tissue may be engaged or aligned in the preferred direction to resist deformation. CIRC MTS of BAV was the highest and LONG MTS of BAV was the lowest when compared to the corresponding orientation of TAV. Higher MTS of CIRC indicates that BAV ATAA becomes stiffer after initial stretching in the circumferential direction and lower MTS of LONG indicates that BAV becomes more compliant in longitudinal direction. The higher difference between CIRC and LONG stiffness of BAV implies that BAV ATAA is more anisotropic when compared with TAV ATAA. The increased anisotropic nature of BAV could explain why BAV ATAAs tend to develop in the characteristically asymmetric pattern that they do along the greater curvature of the proximal ascending aorta. To date, our observations of aortic wall biomechanics including alterations in tensile strength, elastic constitutive material modeling, and tangential stiffness all support our overarching hypothesis that aneurysm formation in BAV patients is due to alterations in ECM architecture rather than collagen content.

A potential limitation of the study is the age discrepancy between BAV and TAV ATAAs, such that aging may compound architectural changes [4, 17]. However, we have previously shown that patient age and aneurysm diameter do not impact the delamination strength of the aortic media [24]. We proposed that reduced medial delamination strength could contribute to a greater risk of dissection in BAV compared with TAV ATAA patients [24]. In this study, we linearly extrapolated the strength of BAV to the corresponding age of TAV. When the tensile strength of BAV was extrapolated to that of the age of TAV, strength of BAV remained higher than TAV (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The extrapolated BAV tensile strength for the various TAV patient ages. *The extrapolated tensile strength of BAV is significantly higher than TAV in both orientations (CIRC p<0.01; LONG p<0.01). ATAA: ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm; BAV=bicuspid aortic valve; CIRC=circumferential; LONG=longitudinal; TAV=tricuspid aortic valve.

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to compare material property, directionally dependent strength and collagen content in the same ATAA specimens between BAV and TAV patients. We showed that BAV ATAAs have greater tensile strength in the circumferential and longitudinal directions and greater failure strain than TAV ATAAs. These data suggest that absolute collagen content does not explain the differences found in the mechanical properties tested for BAV and TAV ATAAs. Rather, given the marked differences in both strength and failure strain, these biomechanical differences support the notion that microstructural differences arise in the collagen framework of the ECM in BAV compared to TAV. Ongoing investigations are focused on the role that matrix architecture plays in region-specific biomechanical strength of the BAV aorta and its pathologic propensity.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Benjamin Green and Michael Eskay for their generous help in tissue collection and transportation and Kristin Valchar, Michelle Shirey and Erica Butler for their assistance in IRB procedures and informed patient consent. This research work was supported by grants: R01-HL060670-09 (DAV), R01-HL086418-04 (DAV) and R01-HL109132-01 (TGG) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. We certify that this manuscript has not been previously published and is not being considered in whole or in part in any other scientific journal. All authors are aware of and agree to the content of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Braverman AC, Guven H, Beardslee MA, Makan M, Kates AM, Moon MR. The bicuspid aortic valve. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2005;30(9):470–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedak PW, Verma S, David TE, Leask RL, Weisel RD, Butany J. Clinical and pathophysiological implications of a bicuspid aortic valve. Circulation. 2002;106(8):900–904. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027905.26586.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ergin MA, Spielvogel D, Apaydin A, et al. Surgical treatment of the dilated ascending aorta: When and how? Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67(6):1834–1839. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00439-7. discussion 1853–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tadros TM, Klein MD, Shapira OM. Ascending aortic dilatation associated with bicuspid aortic valve: Pathophysiology, molecular biology, and clinical implications. Circulation. 2009;119(6):880–890. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.795401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamoto RJ, Wagenseil JE, DeLong WR, Peterson SJ, Kouchoukos NT, Sundt TM., 3rd Mechanical properties of dilated human ascending aorta. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30(5):624–635. doi: 10.1114/1.1484220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vorp DA, Schiro BJ, Ehrlich MP, Juvonen TS, Ergin MA, Griffith BP. Effect of aneurysm on the tensile strength and biomechanical behavior of the ascending thoracic aorta. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(4):1210–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iliopoulos DC, Deveja RP, Kritharis EP, et al. Regional and directional variations in the mechanical properties of ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms. Medical engineering & physics. 2009;31(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choudhury N, Bouchot O, Rouleau L, et al. Local mechanical and structural properties of healthy and diseased human ascending aorta tissue. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2009;18(2):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokolis DP, Kefaloyannis EM, Kouloukoussa M, Marinos E, Boudoulas H, Karayannacos PE. A structural basis for the aortic stress-strain relation in uniaxial tension. J Biomech. 2006;39(9):1651–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fedak PW, de Sa MP, Verma S, et al. Vascular matrix remodeling in patients with bicuspid aortic valve malformations: Implications for aortic dilatation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126(3):797–806. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeMaire SA, Wang X, Wilks JA, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases in ascending aortic aneurysms: Bicuspid versus trileaflet aortic valves. J Surg Res. 2005;123(1):40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotrufo M, Della Corte A, De Santo LS, et al. Different patterns of extracellular matrix protein expression in the convexity and the concavity of the dilated aorta with bicuspid aortic valve: Preliminary results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(2):504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghavan ML, Webster MW, Vorp DA. Ex vivo biomechanical behavior of abdominal aortic aneurysm: Assessment using a new mathematical model. Ann Biomed Eng. 1996;24(5):573–582. doi: 10.1007/BF02684226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghavan ML, Vorp DA. Toward a biomechanical tool to evaluate rupture potential of abdominal aortic aneurysm: Identification of a finite strain constitutive model and evaluation of its applicability. Journal of biomechanics. 2000;33(4):475–482. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stegemann H. microdetermination of hydroxyproline with chloramine-t and pdimethylaminobenzaldehyde. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1958;311(1–3):41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stegemann H, Stalder K. Determination of hydroxyproline. Clin Chim Acta. 1967;18(2):267–273. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(67)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gleason TG. Heritable disorders predisposing to aortic dissection. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;17(3):274–281. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larson EW, Edwards WD. Risk factors for aortic dissection: A necropsy study of 161 cases. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53(6):849–855. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iliopoulos DC, Kritharis EP, Giagini AT, Papadodima SA, Sokolis DP. Ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms are associated with compositional remodeling and vessel stiffening but not weakening in age-matched subjects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(1):101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamoto RJ, Xu H, Kouchoukos NT, Moon MR, Sundt TM., 3rd The influence of mechanical properties on wall stress and distensibility of the dilated ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126(3):842–850. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00728-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillippi JA, Eskay MA, Kubala AA, Pitt BR, Gleason TG. Altered oxidative stress responses and increased type i collagen expression in bicuspid aortic valve patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(6):1893–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, LeMaire SA, Chen L, et al. Increased collagen deposition and elevated expression of connective tissue growth factor in human thoracic aortic dissection. Circulation. 2006;114(1 Suppl):I200–I205. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillippi JA, Green BR, Eskay MA, et al. Mechanism of aortic medial matrix remodeling is distinct in bicuspid aortic valve patients. JTCVS. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.04.028. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasta S, Phillippi JA, Gleason TG, Vorp DA. Effect of aneurysm on the mechanical dissection properties of the human ascending thoracic aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(2):460–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]