Abstract

Embryo implantation is a complicated process involving a series of endometrial changes that depend on differential gene expression. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are important for regulation of gene expression. Previous studies have shown that miRNAs may participate in the regulation of gene expression during embryo implantation. To explore the role of endometrial miRNAs in early murine pregnancy, we used microarrays to investigate whether miRNAs were differentially expressed in the mouse endometrium on pregnancy day 4 (D4) and day 6 (D6). The results demonstrated that 17 miRNAs were upregulated and 18 were downregulated (>2-fold) in D6 endometria compared to D4. We identified that mmu-miR-193 exhibited the highest upregulation on D6, and the upregulation of mmu-miR-193 before embryo implantation could reduce the embryo implantation rate. Further, we demonstrated that mmu-miR-193 influenced embryo implantation by regulating growth factor receptor-bound protein 7 expression. In summary, our study suggests that mmu-miR-193 plays an important role in embryo implantation.

Keywords: embryo implantation, microRNAs (miRNAs), mmu-miR-193, GRB7

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, noncoding RNA molecules that are approximately 20 to 24 nucleotides in length and are common in plants, animals, and viruses.1 MicroRNAs are involved in sequence-specific, posttranscriptional gene regulation by modulating mRNA stability and/or translation. MicroRNA-regulated RNA silencing is accomplished by an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) that results from the interaction between a mature miRNA and its binding site located in the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of the target messenger RNA (mRNA).2 MicroRNA-mediated gene regulation results in weak or dramatic downregulation of gene expression, depending on sequence complementarity between the miRNA, the target miRNA-responsive element, and the total number of miRNA-responsive elements in a given 3’ UTR.3 These small, noncoding RNAs participate in various biological processes, including development, cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and metabolism.

Embryo implantation is a complicated process involving a receptive uterus, a normal, competent embryo at the blastocyst stage, and a synchronized dialog between the uterus and the embryo.4,5 There are many genes known to be involved in embryo implantation, including Sgk1,6 Lif,7 p53,8 Fkbp52,9,10 and others. The process of murine embryo implantation is divided into prereceptive (D1-D3), receptive (D4, the window of implantation), and refractory phases (D5),11 the transitions between which are regulated by estrogen (E2) and progesterone (P4) hormones secreted by the ovary.12 During this period, the endometrium undergoes considerable changes, including rapid cell proliferation, angiogenesis, differentiation, and tissue remodeling.13 These changes depend on precisely regulated differential gene expression, especially during the peri-implantation period.

MicroRNA-mediated gene regulation is classified as weak or dramatic downregulation of gene expression; they play an important function in precise regulation of gene expression. An early study comparing miRNA expression on D4 with that on D1 in pregnant mouse revealed that 32 miRNAs were upregulated more than 1.5-fold and 5 miRNAs were downregulated more than 1.5-fold.14 This group also identified 2 miRNAs, miR-199a* and miR-101a, which play important roles in embryo implantation by regulating the cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) gene. Similarly, Hu et al15 reported changes in miRNA expression levels at implantation and interimplantation sites on D5. These findings suggest that miRNAs play an important role during this process.

In our previous experiments, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) expression on pregnancy day 6 (D6) was dramatically downregulated compared with pregnancy day 4 (D4) and was important for embryo implantation.16 These data suggested that certain miRNAs participate in gene expression regulation before and/or after implantation. In this study, we used miRNA chips to screen for differentially expressed miRNAs in the mouse endometrium before and after implantation. Our data demonstrated a close relationship between miRNAs and endometrial changes in the peri-implantation period. Furthermore, this study identified mmu-miR-193 that was most highly expressed on D6 and affects embryo implantation by regulating growth factor receptor-bound protein 7 (GRB7) expression in the mouse endometrium.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Six- to eight-week-old NIH mice weighing 25 to 30 g were used. The Chongqing Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee approved all of the experiments. Animals were provided by the Chongqing medical university experimental animal center in accordance with the institute’s animal welfare policy (Certificate: SCXK(YU) 2007-0001, Chongqing, China). Mating was performed by housing female and male mice at a 2:1 ratio. The appearance of the vaginal plug marked pregnancy day 1. The pregnant mice were randomly divided into 2 groups. One group of mice were sacrificed on D4 at 0600to 0800 hours, and the others were sacrificed on D6 at 0600 to 0800 hours. The endometria were removed and stored for analysis.

Total RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from the mouse endometrial tissues (without the embryos) using Trizol reagent (TAKARA Biotechnology Co, Ltd, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at −80°C. Quantification and purity assessments were performed by optical density measurement at 260 and 280 nm. Total RNA integrity was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Micro-RNA Chip Assay

Micro-RNA chip hybridization, scanning, and data analysis were performed by Shanghai Kangcheng Bioengineering Co Ltd (Shanghai, China). Total RNA was labeled with Cy3 using a miRCURYTM LNA Array labeling kit (Exiqon, Denmark). Labeled RNAs were then hybridized with miRCURYTM LNA Arrays (Exiqon,). Assay chips were scanned with a Gene Pix 4000B scanner (Axon Instruments, Union City, California), and the data were analyzed with Gene Pix 6.0 software (Axon Instruments).

Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as described previously.17 The PCR primers are listed in Table 1. U6 was used for normalization.

Table 1.

Primers Used to Perform Real-Time miRNA RT-PCR.

| Primers | Sequence (5’→3’) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-200b | RT primer | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGA | |

| GGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACTCATCA | |||

| PCR primer | Forward | CCCCTAATACTGCCTGGTAATGA | |

| Reverse | GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT | ||

| miR-141 | RT primer | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGA | |

| GGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACCCTTCT | |||

| PCR primer | Forward | CCGGGTAACACTGTCTGGTAAAG | |

| Reverse | GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT | ||

| miR-193 | RT primer | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCG | |

| AGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACACTGGG | |||

| PCR primer | Forward | AACTGGCCTACAAAGTC | |

| Reverse | GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT | ||

| U6 | PCR primer | Forward | GCTTCGGCAGCACATATACTAAAAT |

| Reverse | CGCTTCACGAATTTGCGTGTCAT | ||

Abbreviations: miRNA, microRNA; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction.

Bioinformatics Analysis

Target gene prediction was performed with online tools including miRGen,18 Targetscan,19 and Pictar.20

In Situ Hybridization

Mmu-miR-193-specific probes and a negative control (Scrambled) were purchased from Exiqon. Hybridization was performed with an in situ hybridization kit from the Peking Dinguo Biotechnology Company (China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, frozen endometria were sectioned and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 minutes. Fixed samples were incubated with acetylate for 10 minutes followed by protease K treatment at 37°C for 7 minutes. Samples were incubated in prehybridization solution for 3 hours at 55°C in a humidified chamber. After adding the denatured probes (40 µmol/L), samples were incubated overnight at 55°C. Samples were washed with standard saline citrate and incubated with rabbit anti-bovine serum albumin (BSA; 1:100 dilution) at 37°C for 1 hour followed by incubation with ammonium persulfate-labeled goat anti-rabbit Immunoglobulin G (1:100 dilution) for 1 hour and stained with NBT/BCIP (nitro blue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate) at room temperature for 33 minutes.

Injection

Mmu-miR-193 mimics (agomir)21,22 and GRB7 antisense oligonucleotides (5’-CTA GAA AAA CGT TTC TTC TGC TTT CTG CGT CGA ATT CCA CGC AGA AAG CAG AAG AAA CG-3’) were purchased from Guangzhou Ribo Biotechnology Co, Ltd (Guangzhou, China) and were diluted with isotonic NaCl before use. On day 3 of pregnancy, mice were randomly divided into control and experimental groups. Ten control animals were injected with isotonic NaCl into both the cornu uteri. Ten mice in the experimental groups received injections of 8 µL of 30 nmol/L mmu-miR-193 antagomir or GRB7 antisense oligonucleotides into the left cornu uteri and isotonic NaCl into the right cornu uteri as previously described.23 Uteri were removed and examined on day 7 of pregnancy.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Primary stromal cells were obtained from the excised uterus of mouse that was sacrificed on day 4 of pregnancy. After removal, uteri were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, cut into small pieces, and treated with 1 mL 10% trypsin at 4°C for 1 hour, 20°C for 1 hour, and 37°C for 10 minutes. Digestion was terminated by adding Dulbecco-modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/F12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hangzhou Evergreen Biological Engineering Materials Co, Ltd, Huzhou, China). Uterus stromal cells were collected by centrifugation at 500 rpm for 10 minutes. Cells were seeded in 50-mL culture flasks at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (HyClone Laboratories, Inc, Logan, Utah) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell separation and culture were performed using previously described methods.24,25,26

Lipofectamine 2000 (lipo2000) was purchased from Invitrogen (Beijing, China). The mmu-miR-193 mimic and inhibitor were purchased from Guangzhou Ribo Biotechnology Co, Ltd (the transfection effect was verified). Cells were plated at a density of 5000 cells/well in 96-well plates. The miR-200a mimic-lipo2000 mixture (final concentration of 20 nmol/L), miR-200a inhibitor-lipo2000 mixture (final concentration of 100 nmol/L), and negative controls were prepared 1 day after plating and were added to the cells after 20-minute room-temperature incubation. Cells were harvested after culturing for 48 hours.

Dual-Luciferase Activity Assay

For luciferase reporter experiments, the 3’ UTR segment of mouse GRB7, which was predicted to interact with miR-193, was amplified by PCR from mouse complementary DNA and inserted into the pGL3 control vector (Promega) using FseI and XbaI sites immediately downstream from the luciferase stop codon. The recombinant pGL3 plasmid was designated as GRB7-pGL3. The PRL-TK containing Renilla luciferase was cotransfected with GRB7-pGL3 for data normalization. Mouse 3T3 cells were preplated and cultured in 24-well tissue culture plates at a concentration of 3 × 104 cells per well in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum. The next day, 3T3 cells were transfected with 40 ng pRL-TK and 200 ng GRB7-pGL3 vectors. These 3T3 cells were cotransfected with the miR-193 precursor (pre-miR-193), the pre-miRTM miRNA precursor as a negative control, a miR-193 inhibitor (anti-miR-193), or anti-miRTM negative control (Ambion, Beijing, China). All of the transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). Cell lysates were collected and assayed 30 hours after transfection. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity levels were measured using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) in triplicate. The mmu-miR-193 binding site in GRB7 (GGCCAGT) was mutated to GGGCAGT for analysis.

Western Blotting

Uterine samples from each group were extracted on ice-cold radioimmunoassay buffer (1% NP-40, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L PMSF, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail, and the protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit according to the manufacturer protocol (Sigma Chemical Co, Shanghai, China). Western blotting was conducted as previously described.27

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois), using single factor analysis of variance. Differences were considered to be statistically significant for P < .05. Values shown in all of the figures are given as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

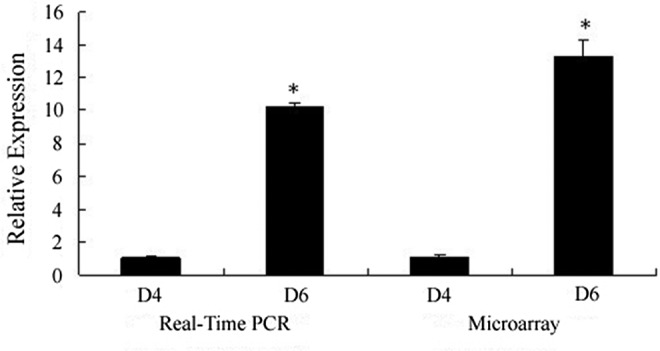

Differential miRNA Expression in the Endometria of Pregnant Mouse

By comparing murine endometrial miRNA levels from pregnancy day 4 (D4) and pregnancy day 6 (D6), we identified that 18 miRNAs were downregulated by more than 2-fold, and 17 miRNAs were upregulated by more than 2-fold in D6 endometria (Table 2; D4: n = 3; D6: n = 3). We then used real-time quantitative PCR to verify changes in the expression of several miRNAs identified in the chip assay, including mmu-miR-200b and mmu-miR-141, which were downregulated, and mmu-miR-193, which was upregulated in the D6 endometria (D4: n = 6; D6:n = 6). The results from the quantitative PCR analysis (Table 3, Figure 1) were largely in agreement with those from the microarray assay.

Table 2.

Differentially Expressed miRNAs in D6 and D4 Mouse Endometria.

| Number | miRNA | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | mmu-miR-199b | 0.4569 |

| 2 | mmu-miR-293* | 0.4918 |

| 3 | mmu-miR-200a | 0.2763 |

| 4 | mmu-miR-10a | 0.2529 |

| 5 | mmu-miR-871 | 0.4863 |

| 6 | mmu-miR-138 | 0.1632 |

| 7 | mmu-let-7i | 0.3696 |

| 8 | mmu-miR-125b-5p | 0.4612 |

| 9 | mmu-let-7b | 0.4116 |

| 10 | mmu-miR-200b | 0.4567 |

| 11 | mmu-miR-106b | 0.4928 |

| 12 | mmu-miR-199a-5p | 0.2055 |

| 13 | mmu-miR-141 | 0.2575 |

| 14 | mmu-miR-135a | 0.3723 |

| 15 | mmu-miR-467b | 0.4597 |

| 16 | mmu-miR-199b* | 0.3174 |

| 17 | mmu-miR-100 | 0.2146 |

| 18 | mmu-miR-429 | 0.1121 |

| 19 | mmu-miR-146b | 11.0873 |

| 20 | mmu-miR-675-5p | 2.2091 |

| 21 | mmu-miR-193 | 13.9202 |

| 22 | mmu-miR-341 | 2.6159 |

| 23 | mmu-miR-668 | 2.4319 |

| 24 | mmu-miR-720 | 3.7926 |

| 25 | mmu-miR-805 | 2.1237 |

| 26 | mmu-miR-494 | 2.0399 |

| 27 | mmu-miR-183* | 2.8177 |

| 28 | mmu-miR-129-5p | 2.8892 |

| 29 | mmu-miR-714 | 3.0067 |

| 30 | mmu-miR-483 | 2.2392 |

| 31 | mmu-miR-673-3p | 2.1115 |

| 32 | mmu-miR-9* | 3.2218 |

| 33 | mmu-miR-690 | 2.0512 |

| 34 | mmu-miR-21* | 2.1890 |

| 35 | mmu-miR-378 | 4.6963 |

Abbreviation: miRNA, microRNA.

Table 3.

Changes in mmu-miR-200b, mmu-miR-141, and mmu-miR-193 Expression Levels From Real-Time RT-PCR and Microarray Results.

| miRNA Name | D6 : D4 Fold Change | |

|---|---|---|

| Real-Time RT-PCR | Microarray | |

| mmu-miR-200b | 0.2386 | 0.4567 |

| mmu-miR-141 | 0.3434 | 0.2575 |

| mmu-miR-193 | 10.2362 | 13.9202 |

Abbreviations: miRNA, microRNA; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction.

Figure 1.

Mmu-miR-193 real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR; D4: n = 6; D6: n = 6) and microarray (D4: n = 3; D6:n = 3) analysis on pregnancy D4 and D6. Real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed as described previously.17 U6 was used as a normalization control. Mmu-miR-193 expression values from pregnant endometrium were expressed relative to D4 values and represent the average ± standard deviation (SD). Microarray analysis was performed by Shanghai Kangcheng Bioengineering Co, Ltd. D4 and D6 represent pregnancy day 4 and day 6, respectively. *P < .05 D6 versus D4.

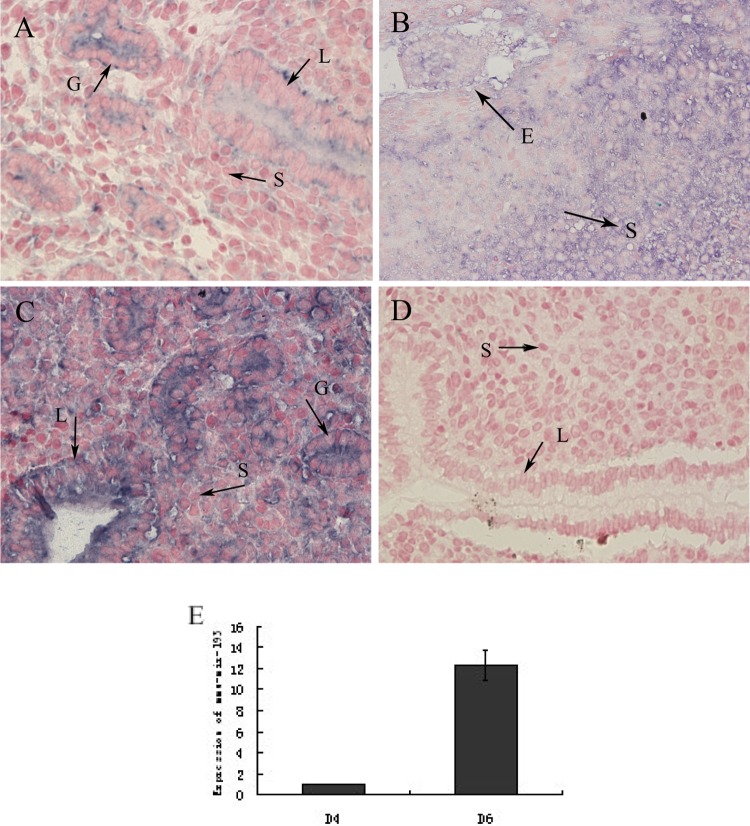

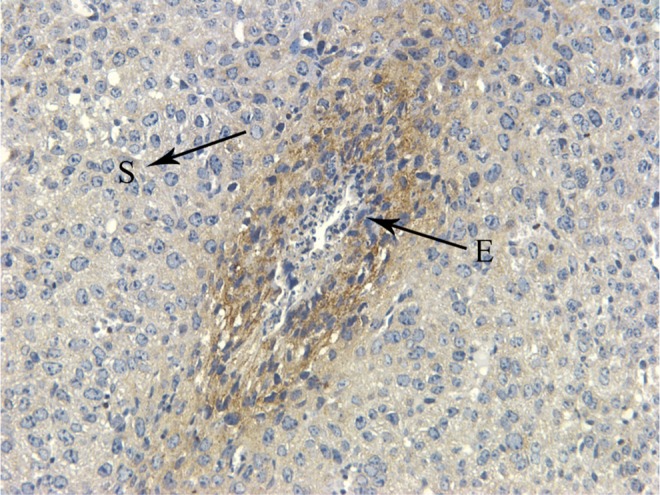

In Situ Hybridization

Next, we examined mmu-miR-193 expression in pregnant mouse endometria using in situ hybridization. We found that expression was significantly higher on pregnancy day 6 than on day 4 (D4: n = 6; D6: n = 6; P < .05). Similar results were obtained as compared with the quantitative PCR analysis. Moreover, mmu-miR-193 expression was observed mainly in luminal epithelial cells and glandular cells but was only weakly present in stromal cells in D4 and D6 interimplantation sites; however, expression was much stronger in stromal cells than in luminal epithelial cells and glandular cells in D6 implantation sites (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

mmu-miR-193 in situ hybridization in mouse uterus. mmu-miR-193 location and expression levels were examined with specific probes and negative controls from Exiqon (Denmark). Blue stain was determined to be positive. Scrambled was used as a negative control. A, D4. B, D6 implantation site. C, D6 interimplantation site. D, Scramble. S indicates stromal cells; G, glandular epithelium; L, luminal epithelium; E, embryo (×400). E, A quantitative representation of the results is shown in (A), (B), and (C) through Image-Pro Plus analysis (n = 6, the experiment was repeated 3 times).

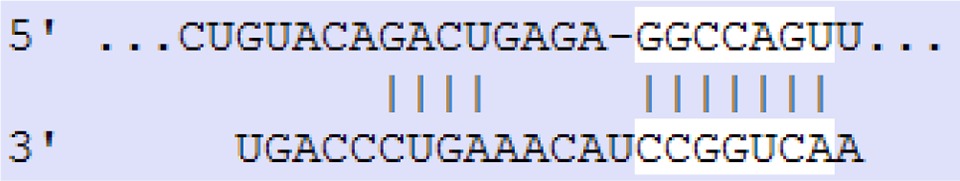

Mmu-miR-193 Target Gene Prediction and Confirmation

We used computational analysis to predict potential mmu-miR-193 target sequences and found that GRB7 was one potential mmu-miR-193 target gene based on its function in the endometrium during embryonic implantation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Target Genes of mmu-miR-193.

| Target Gene Name | Predicted Consequential Pairing of Target Region (top) and miRNA (bottom) | Free Energies kcal/mol | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position 313-319 of GRB7 3' UTR mmu-miR-193 |

|

−26.0 | .97 |

Abbreviation: miRNA, microRNA.

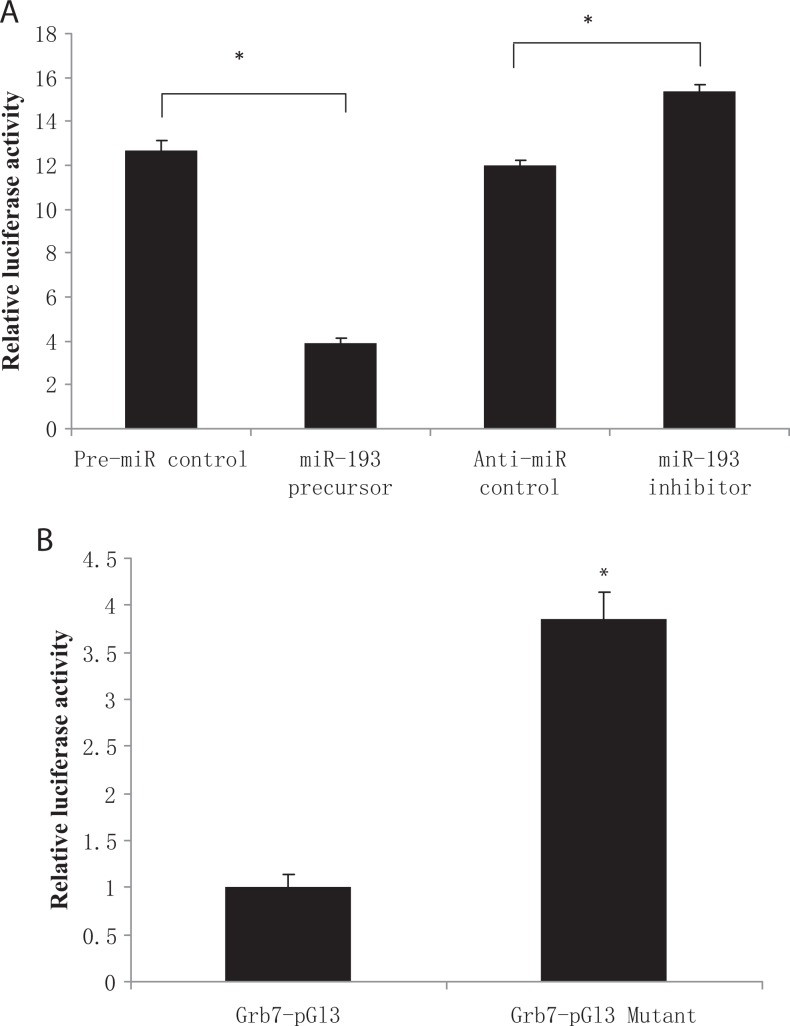

We used a GRB7-luciferase reporter assay to confirm that GRB7 is indeed a mmu-miR-193 target gene. Luciferase activity was not affected by the pre-miR negative control but was significantly decreased with the mmu-miR-193 precursor. Furthermore, luciferase activity was significantly increased after mutation of the mmu-miR-193 binding site. These results demonstrated that GRB7 is a mmu-miR-193 target gene (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mmu-miR-193 target gene confirmation. A, Mouse 3T3 cells were cotransfected with GRB7-pGL3 vector and mmu-miR-193 precursor (pre-miR-193), pre-miR microRNA (miRNA) precursor as a negative control, mmu-miR-193 inhibitor (anti-miR-193), or anti-miR negative control. Luciferase activity was not affected by the pre-miR negative control but was significantly decreased by the miR-193 precursor. Furthermore, luciferase activity was not affected by the anti-miR negative control but was significantly upregulated by the miR-193 inhibitor. *P < .05 versus mmu-miR-193 precursor. B, miR-193 binding site mutation analysis. A single base of the miRNA binding site (GGCCAGT) in GRB7-pG13 was mutated into (GGGCAGT), and mouse 3T3 cells were cotransfected with GRB7-pGL3 vector and mmu-miR-193 precursor; after transfection, luciferase activity was significantly increased, the experiment was repeated 3 times. *P < .05 versus GRB7-pG13. GRB7 indicates growth factor receptor-bound protein 7.

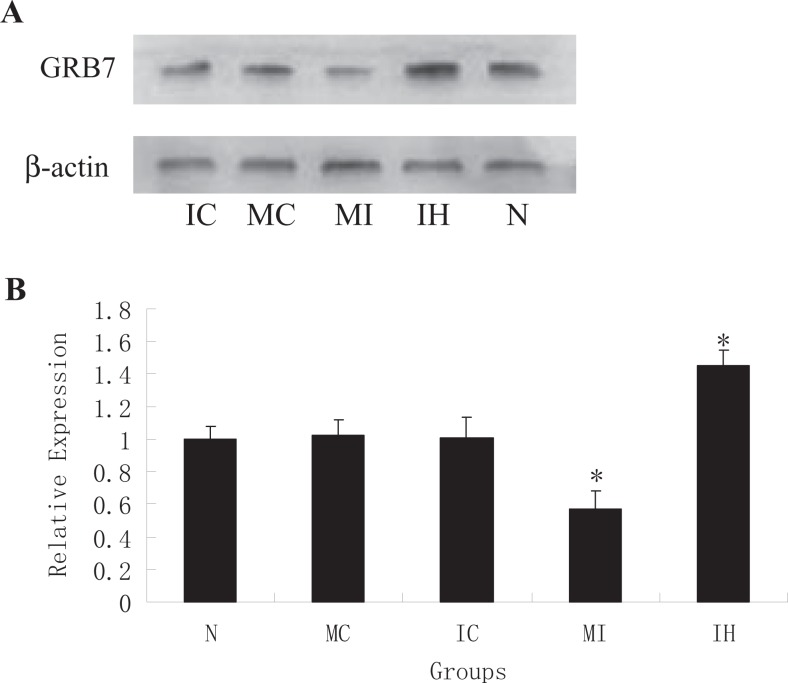

Concurrently, we examined GRB7 expression levels in primary stromal cells that had been transfected with mmu-miR-193 mimics or inhibitors. We found that GRB7 expression was reduced in mimic-transfected cells but increased in inhibitor-treated cells (Figure 4). In contrast, no change in GRB7 expression was observed in control-treated cells. These data support the hypothesis that mmu-miR-193 regulates GRB7 expression in stromal cells.

Figure 4.

Western blot of GRB7 protein expression after transfection. A, GRB7 expression levels were determined by Western blot using anti-GRB7 antibodies 48 hours posttransfection with vehicle, mimics control, inhibitor control, mimics, and inhibitor. N, MC, IC, MI, and IH represent vehicle, mimics control, inhibitor control, mimics, and inhibitor, respectively. β-actin levels were used as loading control. (B) A quantitative representation of the results is shown in (A). Data are from 6 independent experiments. *P < .05 versus vehicle (N). GRB7 indicates growth factor receptor-bound protein 7.

Moreover, we utilized immunohistochemistry to examine the expression and location of GRB7 on D6 (n = 6). Compared with mmu-miR-193, we found that GRB7 was expressed mainly in stromal cells around the blastocyst, whereas mmu-miR-193 had the opposite localization pattern (Figures 2 and 5). These results showed that GRB7 is the target gene of mmu-miR-193.

Figure 5.

GRB7 immunohistochemistry on D6 in mouse uterus. Brown stain was determined to be positive. S indicates stromal cells; E, embryo; GRB7, growth factor receptor-bound protein 7 (×400).

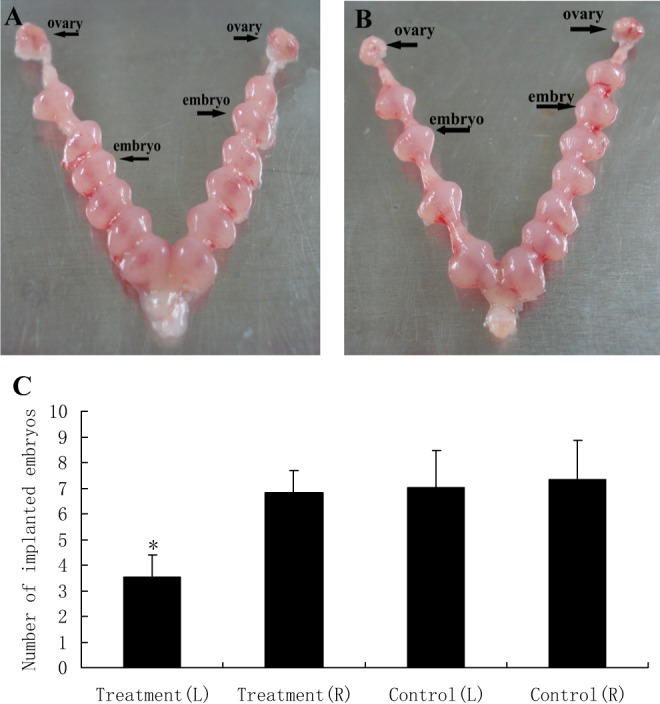

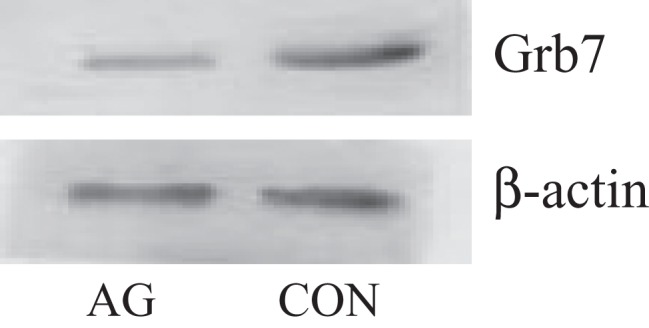

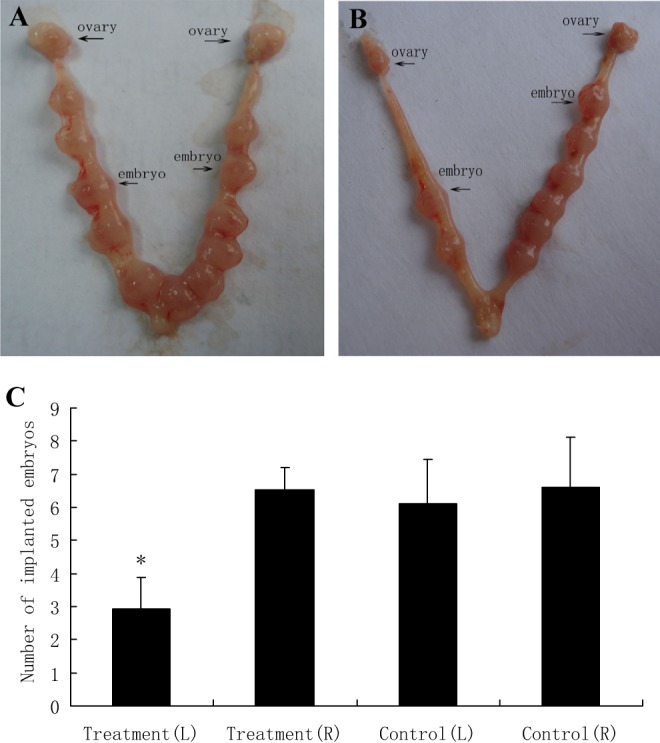

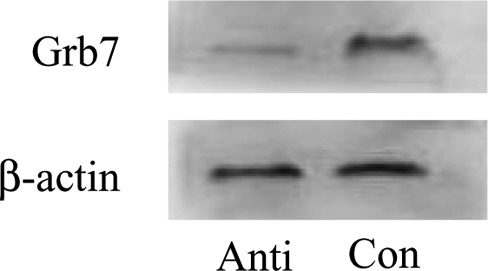

The number of blastocyst implantation sites and GRB7 expression change after injection of mmu-miR-193 agomir and GRB7 antisense oligonucleotide into the cornu uteri. After injection of mmu-miR-193 agomir into the cornu uteri, the numbers of blastocyst implantation sites in the left and right uterine horns of mouse in the experimental group (n = 10) were 3.51 ± 0.89 and 6.81 ± 0.86, respectively. In comparison, the number of implantation sites in the left and right uterine horns of control (n = 10) was 7.02 ± 1.45 and 7.32 ± 1.53, respectively. In the experimental group, the number of implantation sites in the left mmu-miR-193 agomir-treated uterine horn was lower than that in the right isotonic NaCl-treated uterine horn and also lower than that in the control. The number of implantation sites in mouse treated with isotonic NaCl in both uterine horns had no difference (Figure 6). After mmu-miR-193 agomir injection, GRB7 protein expression decreased in the left uterine horn in the experimental group (P < .05; Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Analysis of Mmu-miR-193 function. A, The number of implanted embryos after injecting isotonic NaCl into both cornu uteri between 0800 and 0900 hours on pregnancy D3 was used as a control. B, The number of implanted embryos in the left uterine horns after injecting mmu-miR-193 agomir between 0800 and 0900 hours on pregnancy D3 was markedly decreased compared with the control. The number of implanted embryos after injecting isotonic NaCl into the right cornu uteri was as same as in the control. C, A quantitative representation of the results is shown in A and B. The data shown are an average ± standard deviation (SD). L and R represent left and right, respectively. *P < .05 versus control.

Figure 7.

Western blot of GRB7 protein expression after injecting mmu-miR-193 agomir. Injection mmu-miR-193 agomir between 0800 and 0900 hours on pregnancy D3 and extract protein 72 hours later. Uterine GRB7 protein expression after injecting agomir (AG) was downregulated compared with the control. AG and CON represent agomir and control, respectively; the experiment was repeated 3 times. GRB7 indicates growth factor receptor-bound protein 7.

After injection of GRB7 antisense oligonucleotide into the cornu uteri, the number of implanted blastocysts in the left and right uterine horns of mouse in the experimental group (n = 10) was 2.93 ± 0.95 and 6.52 ± 0.68, respectively. The number of implanted blastocysts in the left and right uterine horns of control mouse (n = 10) was 6.12 ± 1.33 and 6.61 ± 1.52, respectively. In the experimental group, the number of implanted embryos in the left antisense oligonucleotide-treated uterine horn was lower than that in the right isotonic NaCl-treated uterine horn and also lower than that in the control. The number of embryos in the mouse that treated with isotonic NaCl on both sides had no difference (Figure 8). After antisense oligonucleotide injection, GRB7 protein expression decreased in the left uterine horn in the experimental group (P <.05; Figure 9). The results suggest that mmu-miR-193 can affect embryo implantation by regulating the target gene GRB7.

Figure 8.

Function analysis of GRB7. A, The number of the implanted embryos by injecting isotonic NaCl into both cornu uteri between 0800 and 0900 hours on D3 of pregnancy as control. B, The number of implanted embryos in the left uterus horns by injecting antisense GRB7 oligodeoxynucleotide between 0800 and 0900 hours on D3 of pregnancy was markedly decreased compared with the control. The number of implanted embryos by injecting isotonic NaCl into right cornu uteri was same as the control. C, A quantitative representation of the results is shown in A and B. Data shown are average ± standard deviation (SD). L and R represent left and right, respectively. *P < .05 versus control. GRB7 indicates growth factor receptor-bound protein 7.

Figure 9.

Western blot of GRB7 protein expression after injecting antisense GRB7 oligodeoxynucleotide. Injection antisense GRB7 oligodeoxynucleotide between 0800 and 0900 hours on pregnancy D3 and extract protein 72 hours later. GRB7 protein expression in the uterus after injecting antisense GRB7 oligodeoxynucleotide was downregulated when compared to that in control. Anti and Con represented antisense GRB7 oligodeoxynucleotide and control, respectively; the experiment was repeated 3 times. GRB7 indicates growth factor receptor-bound protein 7.

Discussion

The process of embryo implantation is complex and involves interactions between the blastocyst and the uterus. Differential uterine gene expression is important in this process. The majority of mammalian miRNAs participate in gene expression regulation and are involved in cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, metabolism, and spatial and temporal tissue structure regulation.28,29 The human genome contains approximately 1000 miRNAs that regulate approximately 30% of protein-encoding genes.19,30–32 It is possible that all signaling proteins are regulated by miRNAs. It is well established that the generation of mature miRNA requires Dicer, a cytoplasmic multidomain RNase III enzyme, to cut the pre-miRNA. Lack of Dicer results in embryo death between days 12.5 and 14.5 due to angiogenesis defects.33 Additionally, recent studies have shown that mice lacking miRNAs are abnormal, suggesting that miRNAs play an important role as gene expression regulators.34,35

Previous reports have demonstrated that miRNAs are involved in embryo implantation via regulation of their target genes.36,37 Chakrabarty et al found that COX-2, the target gene of miR-101 and miR-199a, is an essential gene for implantation and decidualization.14 Cyclooxygenase 2 is not regulated by E2 and P4 in the former investigations,38 and the scholars were unable to identify the mechanism of COX-2 regulation until Chakrabarty et al discovered that miRNAs can regulate COX-2 expression and then the effect of miRNA was confirmed through its target gene. Hu et al15 performed locked nucleic acid–modified microarrays to study miRNA expression discrepancy in the mouse uterus at implantation sites and interimplantation sites on D5 and also investigated the target genes of differentially expressed miRNAs.15

Unlike their study, our study used a different research strategy. First, we measured the gene expression of endometrium and uterine changes on D4 and D6 (represented the period before and after implantation, respectively). When comparing endometrial miRNAs between pregnancy D6 and D4, we found that 18 miRNAs were downregulated by more than 2-fold, and 17 were upregulated by more than 2-fold. These data suggest that there is a close relationship between miRNAs and endometrial changes during the peri-implantation process. Second, we found that mmu-miR-193 expression in endometrium after embryo implantation was significantly higher than that before implantation, and this pattern of differential expression may have an important role in the process of embryo implantation. So we confirmed that the abnormal expression of mmu-miR-193 results in implantation defect through the functional experiment. Taken together, we thought that miRNAs are indeed involved in the process of embryo implantation.

Using dual-luciferase activity assays, injections, and Western blots, we found that mmu-miR-193 participates in embryo implantation by regulating GRB7 gene expression. GRB7 is a growth factor receptor-binding protein family member and plays an important role in cell migration, which is critical for biological processes such as development, immune responses, wound healing, and tumor metastasis.39 Recently, it was shown that endometrial stromal cell migration at the implantation site may facilitate stromal trophoblast penetration, and it was suggested that embryonic trophoblast spreading and invasion require maternal endometrial stromal cell motility in a Rac1-/RhoA-dependent manner.40 The endocannabinoid system reportedly regulates cannabinoid receptor 1-mediated endometrial stromal cell migration through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) pathway activation.41 A study showed that GRB7, through its interaction with Ras, resulted in increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation.42 Our study found that the number of implantation sites and GRB7 protein expression both decreased after antisense oligonucleotide injection. Therefore, we supposed that GRB7 affects embryo implantation by regulating endometrial cell migration; however, its function during embryo implantation is still unclear.

In summary, we used the miRNA chip technique to study endometrial miRNA expression during the peri-implantation period and found changes in the expression of several miRNAs that may be important for embryo implantation. Among the miRNAs that we identified, the role of mmu-miR-193 in implantation was identified. By injecting mmu-miR-193 agomir into the uterine horn, we found that mmu-miR-193 decreases embryo implantation rate. We subsequently used target prediction software to screen mmu-miR-193 targets and identified GRB7, which we later confirmed as a target. The number of implanted embryos decreased after injection of GRB7 antisense oligonucleotide in the uterine horn of pregnant mouse on day 3. Therefore, our study shows that mmu-miR-193 participates in embryo implantation by regulating GRB7 gene expression and supports the hypothesis that miRNAs play an important role in this process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Qiubo Yu, PhD, for helpful suggestions and De-Hui Yang, MD, for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31271545) and the National Key Clinical Department Funding (201101CKZD). The funders played no role in the study’s design, the collection or analysis of data, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Cai X, Schafer A, Lu S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs are evolutionarily conserved and differentially expressed. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(3):e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stark A, Brennecke J, Bushati N, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Animal MicroRNAs confer robustness to gene expression and have a significant impact on 3'UTR evolution. Cell. 2005;123(6):1133–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(2):102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cha J, Sun X, Dey SK. Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat Med. 2012;18(12):1754–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang H, Dey SK. Roadmap to embryo implantation: clues from mouse models. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(3):185–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salker MS, Christian M, Steel JH, et al. Deregulation of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1 in the endometrium causes reproductive failure. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1509–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, et al. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature. 1992;359(6390):76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu W, Feng Z, Teresky AK, Levine AJ. p53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF. Nature. 2007;450(7170):721–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tranguch S, Cheung-Flynn J, Daikoku T, et al. Cochaperone immunophilin FKBP52 is critical to uterine receptivity for embryo implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(40):14326–14331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tranguch S, Wang H, Daikoku T, Xie H, Smith DF, Dey SK. FKBP52 deficiency-conferred uterine progesterone resistance is genetic background and pregnancy stage specific. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(7):1824–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paria BC, Huet-Hudson YM, Dey SK. Blastocyst's state of activity determines the “window” of implantation in the receptive mouse uterus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(21):10159–10162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dey SK, Lim H, Das SK, et al. Molecular cues to implantation. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(3):341–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lim HJ, Wang H. Uterine disorders and pregnancy complications: insights from mouse models. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(4):1004–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chakrabarty A, Tranguch S, Daikoku T, Jensen K, Furneaux H, Dey SK. MicroRNA regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 during embryo implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(38):15144–15149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hu SJ, Ren G, Liu JL, et al. MicroRNA expression and regulation in mouse uterus during embryo implantation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(34):23473–23484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen X, He J, Ding Y, et al. The role of MTOR in mouse uterus during embryo implantation. Reproduction. 2009;138(2):351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(20):e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Megraw M, Sethupathy P, Corda B, Hatzigeorgiou AG. miRGen: a database for the study of animal microRNA genomic organization and function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(database issue):D149–D155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120(1):15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37(5):495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krutzfeldt J, Rajewsky N, Braich R, et al. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs’. Nature. 2005;438(7068):685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yuan JX, Xiao LJ, Lu CL, et al. Increased expression of heat shock protein 105 in rat uterus of early pregnancy and its significance in embryo implantation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Illera MJ, Cullinan E, Gui Y, et al. Blockade of the alpha(v)beta(3) integrin adversely affects implantation in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2000;62(5):1285–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sakkas D, Trounson AO. Co-culture of mouse embryos with oviduct and uterine cells prepared from mice at different days of pseudopregnancy. J Reprod Fertil. 1990;90(1):109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryan IP, Schriock ED, Taylor RN. Isolation, characterization, and comparison of human endometrial and endometriosis cells in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78(3):642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharpe KL, Zimmer RL, Khan RS, Penney LL. Proliferative and morphogenic changes induced by the coculture of rat uterine and peritoneal cells: a cell culture model for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1992;58(6):1220–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tsai NP, Bi J, Loh HH, Wei LN. Netrin-1 signaling regulates de novo protein synthesis of kappa opioid receptor by facilitating polysomal partition of its mRNA. J Neurosci. 2006;26(38):9743–9749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ouellet DL, Perron MP, Gobeil LA, Plante P, Provost P. MicroRNAs in gene regulation: when the smallest governs it all. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006(4):69616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Song L, Tuan RS. MicroRNAs and cell differentiation in mammalian development. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2006;78(2):140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bentwich I, Avniel A, Karov Y, et al. Identification of hundreds of conserved and nonconserved human microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2005;37(7):766–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berezikov E, Guryev V, van de Belt J, Wienholds E, Plasterk RH, Cuppen E. Phylogenetic shadowing and computational identification of human microRNA genes. Cell. 2005;120(1):21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xie X, Lu J, Kulbokas EJ, Golub TR, et al. Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in human promoters and 3' UTRs by comparison of several mammals. Nature. 2005;434(7031):338–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang WJ, Yang DD, Na S, Sandusky GE, Zhang Q, Zhao G. Dicer is required for embryonic angiogenesis during mouse development. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(10):9330–9335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill J, Olson EN. Control of stress-dependent cardiac growth and gene expression by a microRNA. Science. 2007;316(5824):575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhao Y, Ransom JF, Li A, et al. Dysregulation of cardiogenesis, cardiac conduction, and cell cycle in mice lacking miRNA-1-2. Cell. 2007;129(2):303–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu JL, Su RW, Yang ZM. Differential expression profiles of mRNAs, miRNAs and proteins during embryo implantation. Front Biosci. 2011;3:1511–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Su RW, Lei W, Liu JL, et al. The integrative analysis of microRNA and mRNA expression in mouse uterus under delayed implantation and activation. PloS One. 2010;5(11):e15513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lim H, Paria BC, Das SK, et al. Multiple female reproductive failures in cyclooxygenase 2-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;91(2):197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Han DC, Shen TL, Guan JL. The Grb7 family proteins: structure, interactions with other signaling molecules and potential cellular functions. Oncogene. 2001;20(44):6315–6321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grewal S, Carver JG, Ridley AJ, Mardon HJ. Implantation of the human embryo requires Rac1-dependent endometrial stromal cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(42):16189–16194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gentilini D, Besana A, Vigano P, et al. Endocannabinoid system regulates migration of endometrial stromal cells via cannabinoid receptor 1 through the activation of PI3K and ERK1/2 pathways. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(8):2588–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chu PY, Li TK, Ding ST, Lai IR, Shen TL. EGF-induced Grb7 recruits and promotes Ras activity essential for the tumorigenicity of Sk-Br3 breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(38):29279–29285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]