Abstract

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a serious condition that affects mainly young and middle-aged women, and its etiology is poorly understood. A prominent pathological feature of PH is accumulation of macrophages near the arterioles of the lung. In both clinical tissue and the SU5416 (SU)/athymic rat model of severe PH, we found that the accumulated macrophages expressed high levels of leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H), the biosynthetic enzyme for leukotriene B4 (LTB4). Moreover, macrophage-derived LTB4 directly induced apoptosis in pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs). Further, LTB4 induced proliferation and hypertrophy of human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. We found that LTB4 acted through its receptor, BLT1, to induce PAEC apoptosis by inhibiting the protective endothelial sphingosine kinase 1 (Sphk1)–endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) pathway. Blocking LTA4H decreased in vivo LTB4 levels, prevented PAEC apoptosis, restored Sphk1-eNOS signaling, and reversed fulminant PH in the SU/athymic rat model of PH. Antagonizing BLT1 similarly reversed established PH. Inhibition of LTB4 biosynthesis or signal transduction in SU-treated athymic rats with established disease also improved cardiac function and reopened obstructed arterioles; this approach was also effective in the monocrotaline model of severe PH. Human plexiform lesions, one hallmark of PH, showed increased numbers of macrophages, which expressed LTA4H, and patients with connective tissue disease–associated pulmonary arterial hypertension exhibited significantly higher LTB4 concentrations in the systemic circulation than did healthy subjects. These results uncover a possible role for macrophage-derived LTB4 in PH pathogenesis and identify a pathway that may be amenable to therapeutic targeting.

INTRODUCTION

In pulmonary hypertension (PH), there is increased resistance to blood flow through the lungs, leading to elevated blood pressure in the pulmonary circulation. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a category of PH that refers to World Health Organization group I conditions associated with pulmonary arteriolar remodeling. In this group of diseases, vascular obstruction leads to right heart failure and, ultimately, death. Growth factors, proteases, cytokines, and aberrant bone morphogenetic protein receptor-2 (BMPR2)/metabolic signaling have been suggested to drive the obliterative changes in the small pulmonary arterioles in PAH (1). PH can be idiopathic or associated with disorders ranging from congenital heart disease to HIV infection and connective tissue disorders (1). At least for some patients, inflammation appears to play a major pathogenic role (2, 3). In a preclinical animal model, dysregulated immunity resulting from deficient regulatory T cell (Treg) activity contributes to increased inflammation in experimental PH (4). (By convention, animal models are still referred to as having PH rather than PAH.) Macrophages, in particular, are prominent components of the inflammatory infiltrates in the lungs of patients and animals with PH (4–7). Whether activated macrophages directly promote vascular injury and the development of angio-obliterative PH is not known.

Leukotrienes (LTs) are prominent eicosanoid products of leukocytes, including macrophages, and are important mediators of inflammation (8). Leukotriene B4 (LTB4) and the cysteinyl LTs (CysLTs) (LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4) are synthesized by the enzymatic action of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO), which acts on arachidonic acid (AA) to yield leukotriene A4 (LTA4). LTA4 is quickly converted by leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H) to LTB4 or, alternatively, by LTC4 synthase (LTC4S) to LTC4 (Fig. 1A). LTC4 can be metabolized by sequential hydrolysis to LTD4 and LTE4. LT production is regulated by (i) the posttranslational activation of 5-LO by phosphorylation, (ii) 5-LO interaction with 5-LO activation protein (FLAP), (iii) 5-LO subcellular localization, and (iv) the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (8, 9). Phosphorylation of 5-LO by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) on residue Ser271 increases its enzyme activity in vitro. Ser271 phosphorylation also facilitates the nuclear retention of 5-LO, which enhances LTB4 biosynthesis (10–14).

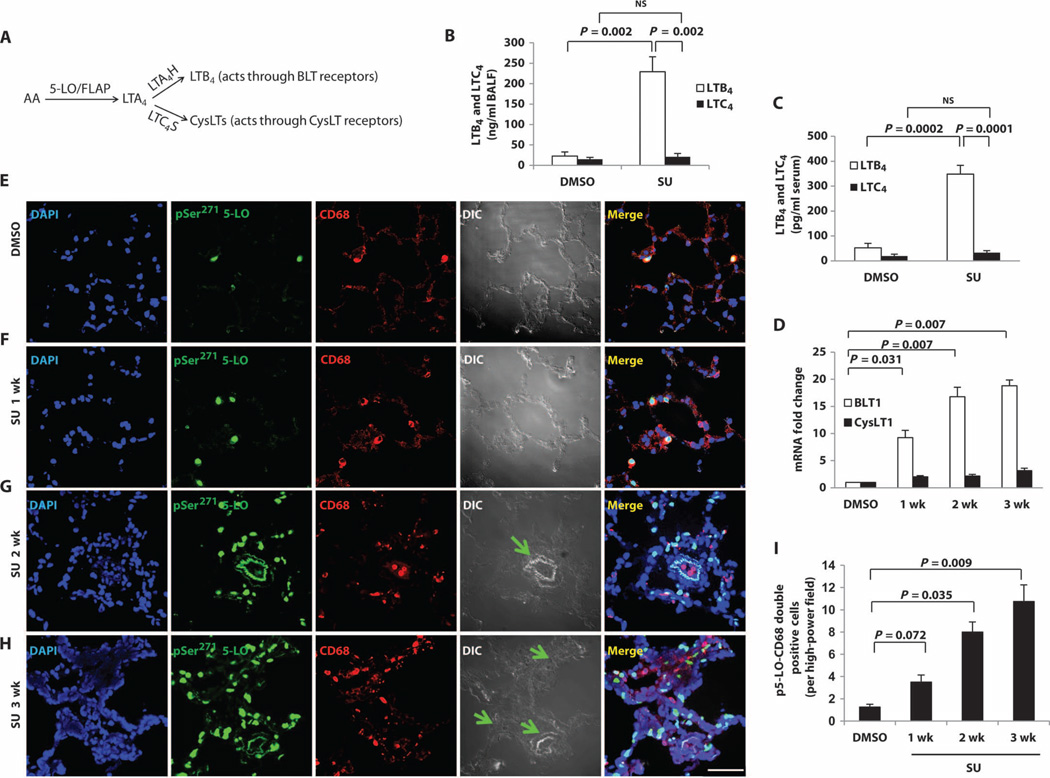

Fig. 1. Increased macrophage LTB4 biosynthesis during evolution of experimental PH.

(A) Summary of the LT pathways. (B and C) LTB4 and LTC4 concentrations in (B) BALF and (C) serum from dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)–treated (vehicle control) and SU-treated (PAH: 3 weeks after SU administration) animals with experimental PH as measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). (D) BLT1 (major LTB4 receptor) and CysLT1 (major CysLT receptor) mRNA levels measured by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). (E to H) Representative immunofluorescence images from lung sections stained with p5-LO (green) and CD68 (red) from (E) DMSO, (F) 1week after SU, (G) 2 weeks after SU, and (H) 3 weeks after SU. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) identifies nuclei. Differential interference contrast (DIC) highlights alveolar and vascular structures. Green arrows point to the center of occluded arterioles. Merged panels show all three stains. (I) Quantitation of the data in (E) to (H) (expressed as p5-LO+ macrophages per high-power field). n = 6 per group. Scale bar, 50 µm. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for post hoc analyses was used. Data are means ± SEM. NS, not significant.

5-LO expression is elevated in pulmonary macrophages and small pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs) in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (iPAH) (15). Targeted disruption of the 5-LO gene in mice and pharmacologic blockade of 5-LO function in rats attenuate chronic hypoxia-associated PH (16). Conversely, adenovirus-mediated up-regulation of 5-LO increases the susceptibility of heterozygous BMPR2 mutant mice to PH (17). CysLTs are elevated in neonatal PH (18) and have been studied because of their established role in smooth muscle contraction (19). Although LTB4 was initially recognized as a chemoattractant for neutrophils, it is now known to have much broader effects in chronic inflammation (8). How the increased expression of 5-LO and the overproduction of LTs are involved in the development of PH remains unknown.

Here, we primarily used an animal model of PH with dysregulated immunity (the SU-treated athymic rat) to study the role of macrophage LTB4 in disease pathogenesis to determine whether LTB4 secreted by infiltrating macrophages was directly injurious to pulmonary arterial endothelium. We also tested whether LTB4 antagonism can affect PH development and progression in vivo, and we examined human PAH lungs and blood for evidence of LTB4 participation.

RESULTS

Activation of the LTB4 axis in macrophages in PH

In athymic (T cell–deficient) rats, a single dose of SU5416 (SU) (10 mg/kg), a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) inhibitor that targets PAECs, is sufficient to induce severe and progressive PH (table S1), even under normoxic conditions (4, 20, 21). In these rats, macrophages accumulate around partially or fully occluded small to mid-sized pulmonary arterioles (4, 7). Using flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood cells, we determined that CD68+ monocytes/macrophages were the primary inflammatory cells expressing 5-LO (fig. S1, A to E) in these animals. Consistent with previous studies (15, 16), we found increased 5-LO expression by immunohistochemistry mainly in the infiltrating periarteriolar CD68+ macrophages in the lungs (fig. S1, F to J); 5-LO expression was higher in the lung than in other solid organs (fig. S2).

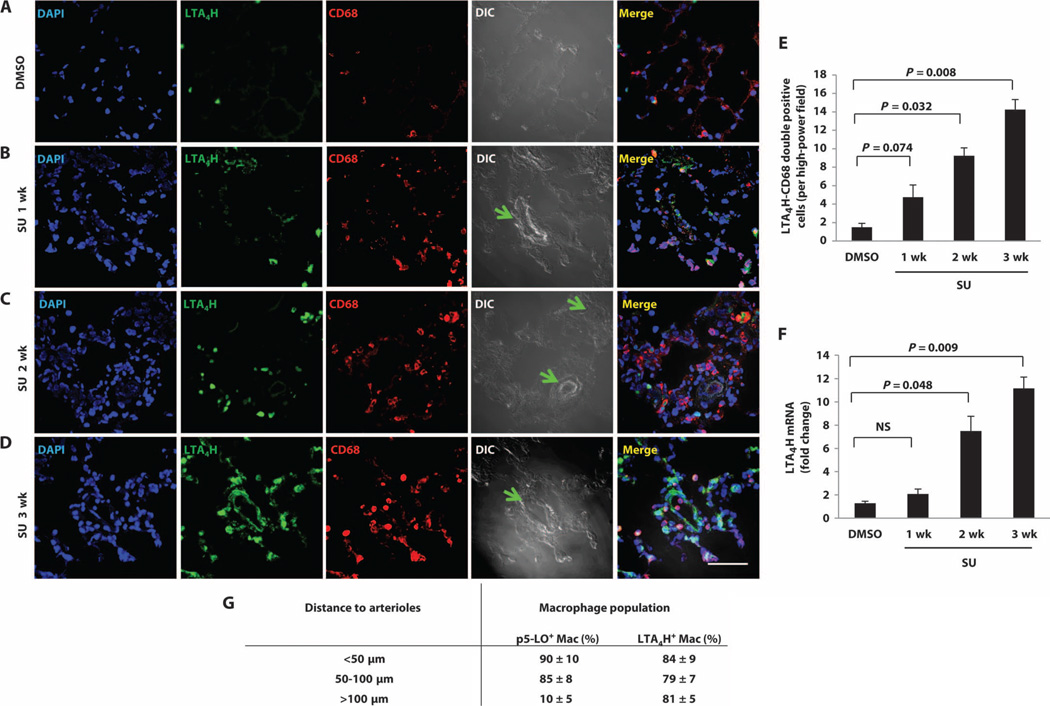

We next examined 5-LO metabolites in our model system. Like human cells (22) [and unlike those from mice (23)], rat macrophages produce 10 times more LTB4 than LTC4 (24), and we hypothesized that LTB4 is overproduced in PH. We found that the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from animals with PH had significantly higher LTB4 levels than BALF from control animals, whereas LTC4 levels were unchanged (Fig. 1B). Similarly, serum levels of LTB4, but not LTC4, were elevated in PH (Fig. 1C), and whole-lung transcript levels for the high-affinity LTB4 receptor BLT1 rose progressively during the evolution of PH, whereas those of the CysLT receptor (CysLT1) did not (Fig. 1D). pSer271 5-LO was localized to CD68+ macrophages and, at 2 to 3 weeks after SU treatment, to the vascular wall of the lung. The number of CD68+ macrophages with pSer271 5-LO increased as PH evolved (Fig. 1, E to I), as did the nuclear membrane localization of pSer271 5-LO, indicating rising LTB4 biosynthesis in pulmonary macrophages (fig. S3). LTA4H, which converts LTA4 to LTB4, was also found in the accumulating macrophages (Fig. 2, A to E), and lung LTA4H mRNA increased with PH development (Fig. 2F). In established disease, LTA4H was localized within cells of the vascular wall.

Fig. 2. Increased macrophage LTA4H over time in developing PH.

(A to D) Representative immunofluorescence images from lung sections stained with antibody to LTA4H (green) and CD68 (red) from (A) DMSO, (B) 1 week after SU, (C) 2 weeks after SU, and (D) 3 weeks after SU. DAPI (blue) identifies nuclei. Green arrows point to the center of occluded arterioles. Merged panel shows all three stains. (E)Quantitation of LTA4H staining over time in PH in pulmonary macrophages. LTA4H+, CD68+ macrophages were counted per high-power field. (F) LTA4H mRNA, as measured by RT-PCR. (G) p5-LO+ or LTA4H+ macrophages were counted and grouped as <50 µm, 50 to 100 µm, or 100 to 150 µm from the center of the small pulmonary arterioles. n = 6 per group. Scale bar, 50 µm. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for post hoc analyses was used. Data are means ± SEM.

To test whether macrophages near arterioles in PH lungs were activated, we did a morphometric assessment of macrophages within 150 µm of arterioles. The macrophages closest to diseased pulmonary arterioles had the highest expression of both inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which is an M1 activation marker (25) (fig. S4, A and C), and pSer271 5-LO (p5-LO) (Fig. 2G); LTA4H+ macrophages, by distinction, were common throughout the PH lung without localization near arterioles (Fig. 2G). Most iNOS+ macrophages isolated from collagenase-digested PH lungs were also p5-LO+, indicating that these arteriole-associated macrophages were primed to produce LTB4 (fig. S4B). The increased iNOS expression in infiltrating, activated M1 macrophages did not lead to a net increase lung NO release (fig. S5). Because NO produced by iNOS reacts with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, we measured reactive oxygen species (ROS) and found increased oxidative stress in PH lungs (fig. S6), raising the possibility that ROS contribute to arteriolar injury in PH development as a result of immune dysregulation. To evaluate the relative importance of these accumulating cells in PH development, we administered clodronate-containing liposomes to athymic rats 1 day before SU administration and biweekly thereafter for 3 weeks. This treatment reduced blood CD68+ monocytes/macrophages by 93% and prevented PH (fig. S7). These data collectively demonstrate that immune dysregulation–associated PH is macrophage-dependent and is characterized by a progressive perivascular infiltration of activated macrophages with up-regulated LTB4 synthetic machinery.

LTB4 induction of PAEC apoptosis and human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells proliferation and hypertrophy

PAEC injury is an important early event in PH pathogenesis (20). Therefore, we next determined whether lung macrophages could injure endothelial cells in PH lungs. We established a macrophage-PAEC coculture system that used pulmonary macrophages purified separately from the interstitial and alveolar compartments, as described (26, 27). In contrast to interstitial macrophages from control lungs, interstitial macrophages isolated from the lungs of SU-treated athymic rats with PH induced significant endothelial cell apoptosis, as assessed by flow cytometric analysis of annexin V staining; these results were confirmed by cleaved caspase-3 staining of cultured endothelial cells (Fig. 3, A and B, and fig. S8).

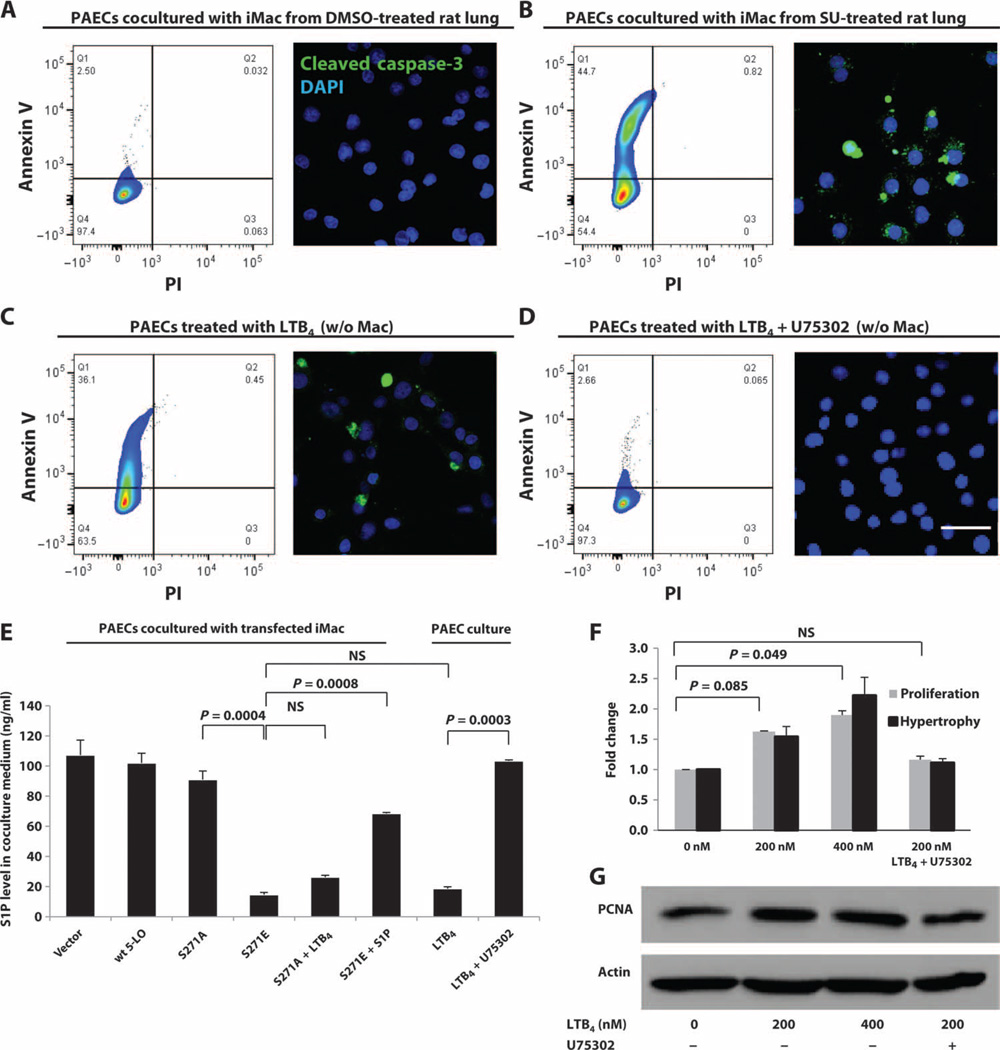

Fig. 3. LTB4 induction of PAEC apoptosis and promotion of human PASMC (hPASMC) growth and hypertrophy.

(A and B) Interstitial macrophages from (A) DMSO and (B) SU rat lungs were cocultured with PAECs for 24 hours. PAEC apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry for annexin V and by confocal microscopy for cleaved caspase-3 staining (green). (C and D) Effect of LTB4 on endothelial injury. PAECs were treated with (C) exogenous LTB4 (200 nM) or (D) LTB4 (200 nM) and U75302 (1 mM). (E) S1P concentrations in culture medium from different cells and treatments, as measured by LC-MS/MS. (F) Effect of LTB4 on smooth muscle cells. Various concentrations of LTB4 were added to hPASMC culture with or without U75302 (1 mM) for 24 hours. hPASMC proliferation was measured by MTT assay. Cellular hypertrophy was determined by protein/DNA ratio. n = 3 per group. Scale bar, 50 µm. Representative flow cytometry plots and confocal images are shown. (F) LTB4-induced hPASMC growth as measured by Western blot of PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen). n = 3 per group. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for post hoc analyses was used. Data are means ± SEM. NS, not significant.

To test whether macrophage-derived LTB4 generation was sufficient to induce endothelial damage, we first isolated interstitial macrophages from healthy rats. Next, we transfected them with S271E 5-LO to produce a 5-LO phosphorylation mimic mutant with constitutive LTB4 production and with S271A to produce a dephosphorylation mimic mutant with deficient LTB4 production (10). Although interstitial macrophages transfected with either vector alone, wild-type 5-LO, or S271A DNA did not induce endothelial cell apoptosis (fig. S8, B to D), S271E mutant macrophages caused PAEC death similar to macrophages isolated from lungs of SU-treated rats (fig. S8E). Given the evidence for oxidative stress in the lungs of rats with PH, we tested the role of ROS, generated as a byproduct of the 5-LO–catalyzed oxygenation reaction (28), in PAEC apoptosis; S271E cells were cocultured with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC); no diminution of apoptosis was observed (fig. S8F). Addition of exogenous LTB4 (200 nM) to the cocultures with macrophages transfected with inactive S271A 5-LO caused PAEC apoptosis (figs. S8G and S9).We examined macrophage transfection efficiency by flow cytometry (fig. S9). LTB4 biosynthesis was evident in both interstitial and alveolar macrophages (Fig. 1, E to H), and macrophages from both compartments equally induced LTB4-mediated PAEC injury (Fig. 3 and figs. S8 and S10). These findings indicate that LTB4 can be directly injurious to PAECs. To confirm that LTB4 was sufficient (in the absence of macrophages) to induce PAEC apoptosis, we cultured PAECs in various physiologically relevant concentrations of LTB4. Significant apoptosis was observed at 24 hours (Fig. 3C) in a dose-dependent manner (fig. S11, A to F). In contrast, addition of exogenous LTC4, LTD4, or LTE4 did not induce PAEC apoptosis (fig. S11, G to I).We confirmed these results in synchronized PAEC cultures (fig. S12). LTB4 induced >50%PAEC apoptosis in vitro at concentrations equal to those in BALF (Fig. 1B) from PH rats. Therefore, LTB4 generated in PH macrophages was likely sufficient to cause vascular injury. In addition, blocking BLT1, the major receptor for LTB4 in endothelial cells (29), with U75302 prevented LTB4-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 3D). These data collectively show that lung macrophages directly induce endothelial cell apoptosis ex vivo, likely through BLT1-mediated action of macrophage-derived LTB4. We also tested the effects of LTB4 on human smooth muscle cells from pulmonary arterioles by adding exogenous LTB4. At concentrations similar to those in PH BALF (Fig. 1B), LTB4 induced the proliferation and hypertrophy of these cells in a concentration- and BLT1-dependent manner (Fig. 3, F and G).

LTB4 induction of PAEC apoptosis through inhibition of the endothelial sphingosine kinase 1–endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathway

We next sought to elucidate how LTB4 injured endothelial cells. Because endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is activated by sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) (30) and is a fundamental endothelial cell survival factor (31), we hypothesized that LTB4 inhibited endothelial sphingosine kinase 1 (Sphk1) activity (the enzyme responsible for phosphorylating sphingosine and generating S1P) and downstream eNOS activation. We measured S1P concentrations in the culture medium of PAECs (Fig. 3E). The results paralleled those from our apoptosis assays (Fig. 3 and fig. S8); the experimental groups exhibiting endothelial cell apoptosis (macrophage coculture groups: S271E, S271A plus exogenous LTB4, and PAECs alone with exogenous LTB4) all also exhibited low S1P levels. Moreover, exogenously added S1P rescued PAECs cocultured with S271E cells (fig. S13).

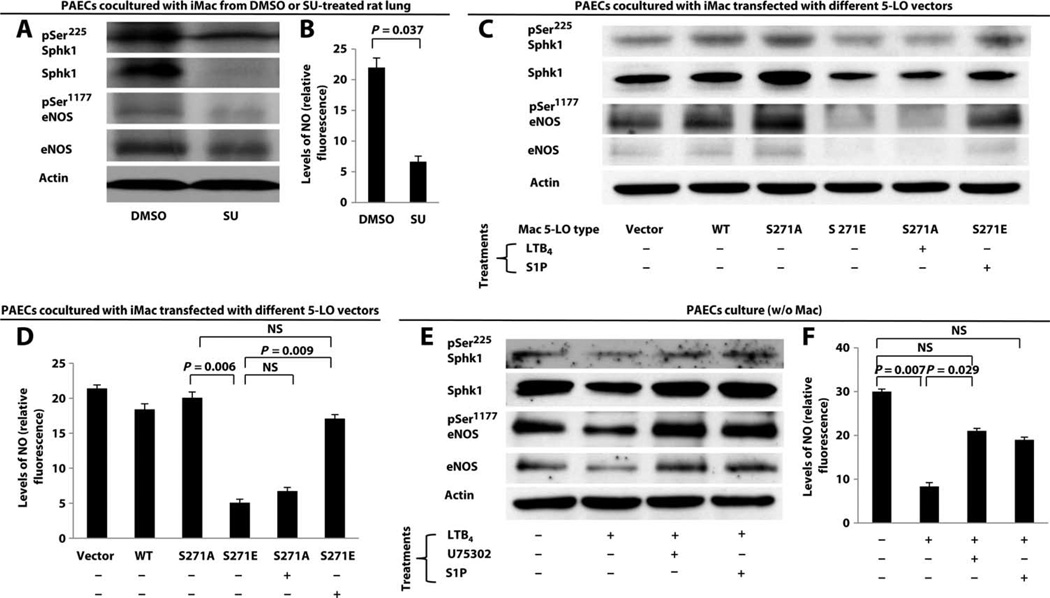

Next, we assessed PAECs incubated with various macrophages for the expression and activation (phosphorylation) of Sphk1 and eNOS. PAECs incubated with macrophages isolated from SU-treated PH lungs exhibited diminished levels of Sphk1 and eNOS by Western blot (Fig. 4A and fig. S14, A to C). Correspondingly, production of NO, a key endothelial prosurvival molecule, by activated eNOS was reduced in PAECs cultured with macrophages from SU-treated lungs (Fig. 4B). PAECs cultured with macrophages transfected with the S271E mutant also exhibited reduced Sphk1 and eNOS compared to PAECs cultured with macrophages transfected with only vector, wild-type 5-LO, or S271A mutant DNA (Fig. 4C). Addition of LTB4 to cultures with macrophages transfected with S271A reduced Sphk1 and eNOS expression, whereas addition of S1P to the culture with macrophages expressing S271E restored the levels of Sphk1 and eNOS. The overall reduction in total Sphk1 and eNOS production in PAECs likely accounted for the reduction in S1P and NO levels because the ratios between the active and total forms of both Sphk1 and eNOS did not indicate a selective inhibition of the active enzymes (fig. S14, C, F, and I). NO production was reduced when PAECs were cultured with macrophages expressing S271E or S271A cultured with exogenous LTB4; S1P restored NO production in the culture with S271E-expressing macrophages (Fig. 4D). Finally, when PAECs were cultured alone with exogenous LTB4, similar results were obtained (Fig. 4, E and F). Blocking the LTB4-BLT1 interaction with the BLT1 antagonist U75302 prevented PAEC apoptosis and preserved the levels of Sphk1-eNOS-NO pathway components. These data collectively demonstrate that LTB4 (and not the CysLTs) secreted by activated macrophages induces PAEC apoptosis in a BLT1-dependent manner through inhibition of endothelial S1P synthesis and NO production.

Fig. 4. LTB4 induction of PAEC apoptosis through the inhibition of endothelial Sphk1-eNOS pathway.

(A to F) PAECs cultured with or without macrophages were examined for pSer225 Sphk1, total Sphk1, pSer1177 eNOS, and total eNOS expression by Western blot. Because of differences in antibody specificity and sensitivity, blots were developed at various exposure times to best represent the signal of interest. Densitometry of the Western blots is summarized in fig. S8. Western blots of PAECs cultured with (A) macrophages isolated from DMSO and SU-PH athymic rat lungs, (C) transfected macrophages treated with or without LTB4 (200 nM) or S1P (1 µM), and (E) exogenous LTB4 (200 nM) with or without U75302 (1 µM) and with or without S1P (1 µM). NO production from culture medium in (A), (C), and (E) is summarized in (B), (D), and (F), respectively. NO levels are expressed relative to background fluorescence. n = 3 experiments per group. Data are means ± SEM. NS, not significant.

The reversal of established PH by inhibition of LTB4 biosynthesis or LTB4 signaling

Because (i) p5-LO+ and LTA4H+ macrophages progressively infiltrated PH lungs, (ii) macrophage depletion prevented SU-induced PH, (iii) macrophage-derived LTB4 likely mediated injury to endothelial cells, (iv) LTB4 induced pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell (PASMC) proliferation and hypertrophy, and (v) activated LTB4-secreting macrophages were contiguous with diseased arterioles, we hypothesized that inhibiting LTB4 signaling would be beneficial as a treatment in this model of PH. Bestatin [(2S, 3R)-3-amino-2-hydroxy-4-phenylbutanoyl-l-leucine] (not a statin derivative) is a well-tolerated LTA4H inhibitor that blocks LTB4 formation (32, 33). We tested whether delayed administration (a clinically relevant therapeutic strategy) of this LTA4H inhibitor could reverse established PH (fig. S15). In the SU/athymic rat model, echocardiographic evidence of PH was first detected between 1 and 2 weeks, and severe PH was evident by 3 weeks after SU administration. For this study, we tested three delayed intraperitoneally bestatin-dosing regimens. Therapy initiated as late as 3 weeks after SU administration was highly effective in reversing PH (fig. S15). Subsequently, we initiated all studies evaluating therapies in animals with severe PH 3 weeks after SU administration and followed surviving animals out to week 5 when they underwent a terminal right heart catheterization. A sustained-release oral formulation of bestatin was also highly effective for reversing PH (Fig. 5A and fig. S16). Bestatin efficacy was dose-dependent; oral availability of bestatin was determined by pharmacokinetic analysis with four different doses. Bestatin was absorbed rapidly within 3 hours and was eliminated from the body with a t1/2 of 12 hours (fig. S17). An inhalable formulation of bestatin also reversed established PH (fig. S18).

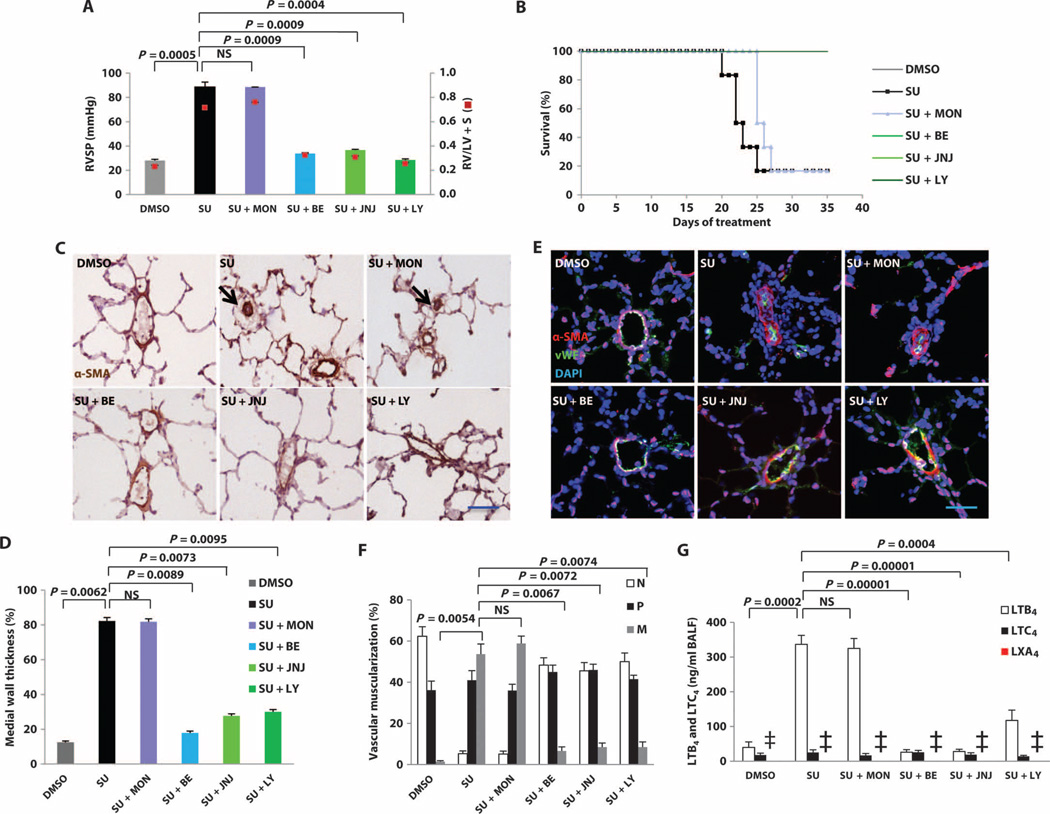

Fig. 5. The reversal of established PH by blockade of LTB4 signaling.

Rats were treated with montelukast (MON), bestatin (BE), JNJ-26993135 (JNJ), or LY293111 (LY) starting 3 weeks after SU administration. Animals were monitored by echocardiography weekly and sacrificed for hemodynamic measurements at week 5. (A) Right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) in DMSO, SU, and four different treatment protocols at week 5 after SU treatment (doses of the drugs used: montelukast, 10 mg/kg, orally, daily; bestatin, 1 mg/kg, orally, daily; JNJ-26993135, 30 mg/kg, orally, twice daily; LY293111, 0.5 mg/kg, orally, daily). RV hypertrophy (RVH) was assessed by the RV/[left ventricle (LV) + septum (S)] weight ratios. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot of survival of the groups of rats treated as in (A). The bestatin-, JNJ-26993135–, and LY293111-treated groups overlap with the DMSO group. (C) Representative immunohistochemistry images of pulmonary arterioles stained for α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) in lung tissues at week 5. Black arrows, occluded arterioles. (D) Medial wall thickness of α-SMA–positive small vessels (<100 µm in external diameter) from rats described in (A). Data are expressed as % total occlusion. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of pulmonary arterioles stained for α-SMA (red) and von Willebrand factor (vWF) (green) in lung tissues at week 5 from rats described in (A). DAPI (blue), nuclei. (F) Proportion of nonmuscularized (N), partially muscularized (P), or fully muscularized (M) pulmonary arteries, as a percentage of the total pulmonary arteriolar cross-sectional area (sized <100 µm) from rats described in (A). (G) LTB4, LTC4, and LXA4 in BALF as measured by LC-MS/MS in rats described in (A). SU data were pooled from contemporaneous control data (n = 15) as comparator because only one of the SU (PH) rat survived to 5 weeks in this experiment, as reflected in survival curve in (B). n = 6 per group. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test for post hoc analyses was used. Data are means ± SEM. NS, not significant. ‡, LXA4 levels in the experiment groups were below the level of detection.

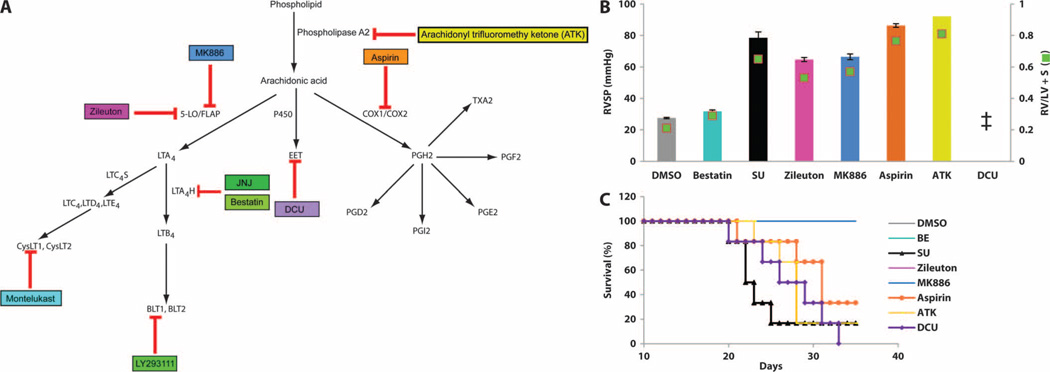

Because bestatin can exert pharmacologic actions in addition to LTA4H inhibition (34), we sought additional evidence that reducing LTB4 synthesis or actions was responsible for reversing PH. To this end, we tested a structurally different LTA4H inhibitor (JNJ-26993135) and a BLT1 receptor antagonist (LY293111). These other two agents also reversed PH and prevented PH-related death; the CysLT antagonist montelukast had little effect (Fig. 5, A and B). Blocking LTB4, either through inhibition of its biosynthesis or through receptor antagonism, increased the numbers of open arterioles and decreased arteriolar wall thickness and muscularization in parallel with reduced BALF LTB4 levels; by contrast, antagonizing CysLTs was not effective (Fig. 5, C and F). BLT1 antagonism also induced reduced BALF LTB4 levels, despite not blocking LTB4 biosynthesis, suggesting an autocrine loop. In addition to blocking LTB4 synthesis, LTA4H inhibition can also augment synthesis of anti-inflammatory lipoxin A4 (LXA4), and this mechanism has been suggested to contribute to decreased allergic airway inflammation (35); however, LXA4 was undetectable in the BALF in all groups (Fig. 5G). Furthermore, interruption of other eicosanoid pathways had little or no capacity to reverse PH. Inhibition of upstream 5-LO (with Zileuton) and FLAP (with MK886) mildly attenuated pressures and prevented death, whereas inhibition of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (with arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone), cyclooxygenase (COX) (with aspirin), and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) [with dicyclohexyl urea (DCU)] had minimal effects (Fig. 6 and fig. S19). (The dosing regimens for these compounds are listed in table S2.)

Fig. 6. Components of the eicosanoid pathway in experimental PH.

(A) Eicosanoid synthesis pathways, with the site of action of various inhibitors indicated: PLA2 inhibitor, arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone (ATK); 5-LO inhibitor, Zileuton; FLAP inhibitor, MK886; COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitor, aspirin; EET inhibitor, DCU. (B) RV parameters in rats treated with the inhibitors described in (A) 3 weeks after SU administration. See table S2 for complete dosing regimens. Animals were monitored by echocardiography weekly and sacrificed for hemodynamic measurement at week 5. RVSP and RV/(LV + S) measurements after treatments with DMSO, SU, bestatin, and five inhibitors were assessed at week 5 of SU administration. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve showing survival of rats after treatment. n = 6 per group. Bestatin treatment group overlaps with the DMSO, Zileuton, and MK886 groups. Data are means ± SEM. ‡, all animals were dead by the day of terminal cardiac catheterization.

Next, we evaluated the anti-inflammatory effect of LTA4H inhibition with bestatin. Athymic SU-treated rats show vascular infiltration with macrophages and B cells during PH development (4, 7). Bestatin significantly reduced the accumulation of LTA4H-expressing periarteriolar macrophages, B cells, and inflammatory cytokines in the lungs of SU-treated athymic rats (figs. S20 and S21). Bestatin reduced in vivo PAEC apoptosis, possibly by suppressing LTB4-mediated inhibition of the Sphk1-eNOS pathway (figs. S22 to S24). To investigate whether bestatin-induced regression of vascular pathology was associated with increased apoptosis in the thickened vessel wall, we examined lungs from 4-week rats (−1week into bestatin therapy) with histology and found them to exhibit increased terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) positivity in both the abnormal smooth muscle and intimal layers of diseased arterioles (fig. S25), indicating increased apoptosis.

Finally, we tested delayed bestatin therapy in the monocrotaline (MCT) and SU/chronic hypoxia PH models. Bestatin reversed PH in wild-type rats given MCT at the same time that it reduced serum LTB4 levels (fig. S26). In contrast, SU/chronic hypoxia rats exhibited markedly fewer LTA4H+ periarteriolar macrophages than athymic, SU-treated animals and no elevation in lung LTB4; the PH of these rats failed to respond to bestatin (fig. S27). Thus, LTB4 and LTB4-targeted therapy seems to be relevant only to experimental PH associated with immune dysregulation and characterized by high LTB4 production.

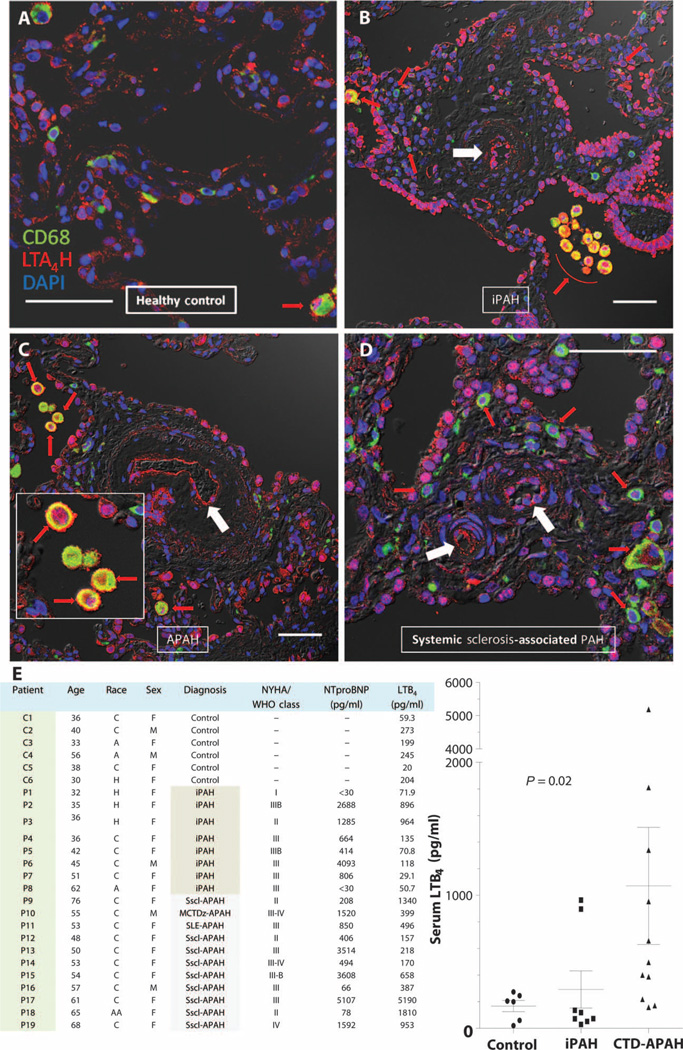

Increased LTB4 biosynthesis seen in human PAH

To determine the clinical relevance of the elevated LTB4 production observed in the athymic and MCT rat models, we examined the lungs of six PAH patients for LTA4H expression in CD68+ macrophages. In five of six PAH lungs, LTA4H expression was notably increased in macrophages clustered around occluded vascular lumens of plexiform lesions (representative images from three PAH patients and a healthy control are shown in Fig. 7, A to D). We also saw, as in the SU-treated, athymic rat, increased LTA4H in endothelial cells lining the nearly occluded vascular lumens of the plexiform lesions; in the sixth patient, who did not have increased LTA4H+ pulmonary macrophages, we still observed focal increases in LTA4H expression in the occluded vascular lumen. Next, we assessed LTB4 serum levels in 19 PAH patients and compared these values to those from 6 healthy individuals (Fig. 7E). LTB4 levels were elevated significantly in PAH patients, especially in those with connective tissue disorders; these latter individuals exhibited mean LTB4 levels about fivefold higher than those in healthy controls. By distinction, six of eight iPAH patients appeared to have normal LTB4 levels. There was no correlation between age and serum LTB4 in this cohort (r2 = 0.08). In conclusion, some, but not all, PAH patients exhibited evidence of increased LTB4 biosynthesis in lung macrophages, in occluding arteriolar intimal cells and in the systemic circulation.

Fig. 7. LTA4H expression and serum LTB4 concentrations in PAH patients.

(A to D) Confocal images of human lung tissues stained for CD68 (green) and LTA4H (red). (A) Healthy control. (B) Plexiform lesion from lung of patient with iPAH. (C) Plexiform lesion from patient with PAH associated with systemic sclerosis. (Inset) LTA4H+CD68+ macrophages in the alveolar space. (D) Plexiform lesion from systemic sclerosis–associated PAH lung. DAPI (blue), nuclei; red, LTA4H+CD68+ macrophages; white arrows, occluded arterioles. Scale bars, 50 µm. (E and F) Serum LTB4 concentrations in healthy controls (n = 6) and treatment-naïve PAH patients (n = 19). Gray shaded area in chart indicates CTD-APAH patients. (Right) Data from chart presented as concentrations (points) and means ± SEM in figure (lines and whiskers). P value reflects nonparametric one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal-Wallis test. H, Hispanic; C, Caucasian; A, Asian; AA, African American. Diagnosis: iPAH, idiopathic PAH; MCTDz-APAH, mixed connective tissue disease–associated PAH; SLE-APAH, systemic lupus erythematosus–associated PAH; Sscl-APAH, systemic sclerosis–associated PAH; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class. WHO, World Health Organization; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro-B–type natriuretic peptide.

DISCUSSION

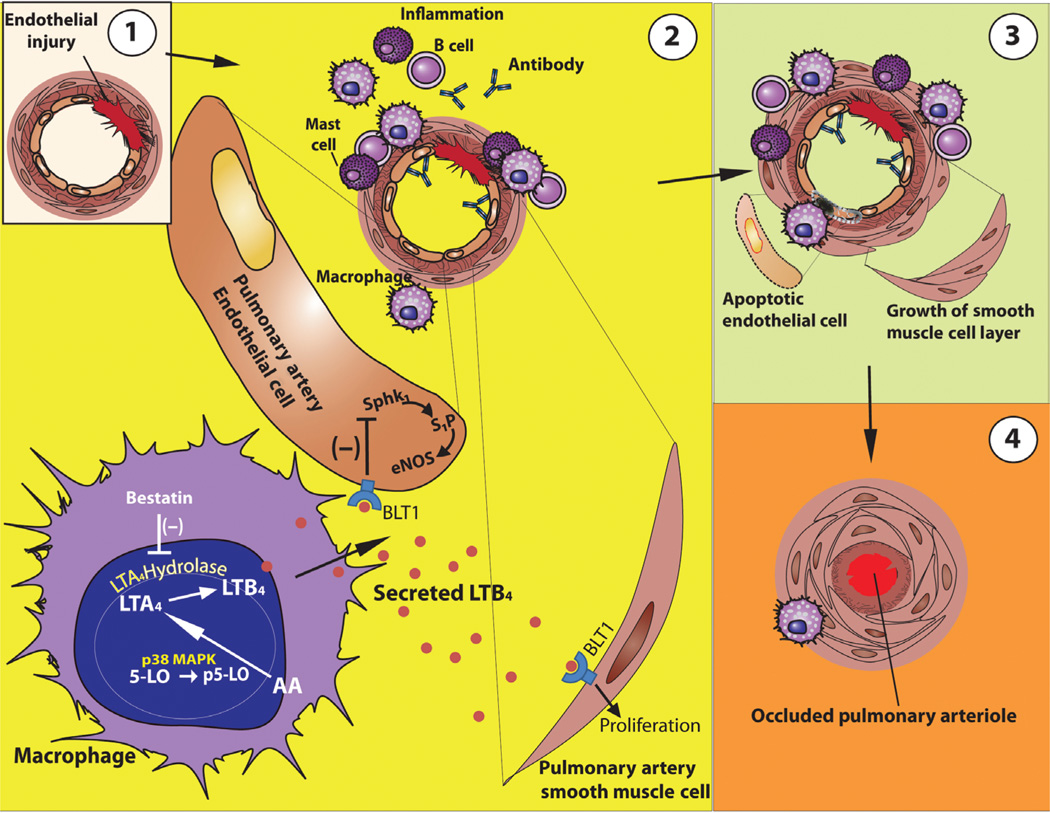

Here, we report increased LTA4H-expressing macrophages in human PH and establish, in a rat model of immune-dysregulated PAH, that increased synthesis of macrophage-derived LTB4 is sufficient to induce PAEC apoptosis. We further demonstrate that inhibiting LTB4, through LTA4H blockade or BLT1 antagonism, reverses the pulmonary vascular disease even after PH is already advanced. SU-mediated vascular injury in animals with dysregulated immunity leads to LTB4-mediated propagation of the vascular injury and results in angio-obliterative PH(Fig. 8). Experimental evidence suggests that when an individual has an impaired ability to resolve inflammation, vascular injury progresses and results in PAH (2–4). Previous observations that T cell–deficient athymic rats develop particularly aggressive PH (4, 7, 36) can be explained by the lack of CD4+ Treg populations in these animals; these Tregs, when present, are sufficient to self-limit vascular inflammation (4). Patients with conditions in which PAH occurs, such as HIV infection, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Sjögren’s syndrome, and the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, all exhibit abnormalities in CD4+ T cell number and function (37–42). A failure of Tregs to resolve vascular inflammation after endothelial injury may result in the accumulation of dysregulated macrophages; overproduction of LTB4 by these cells appears to play a key role in the evolution of PH.

Fig. 8. Model illustrating how macrophage-derived LTB4 may induce vascular remodeling and contribute to PH.

(A) Endothelial injury causes a local immune response. (B) With immune dysregulation because of a lack of normal Treg activity, there is an exuberant inflammatory response that includes perivascular inflammation with mast cells, B cells, anti–endothelial cell antibodies, and macrophages. In macrophages, 5-LO is phosphorylated by p38 MAPK in the nucleus. p5-LO converts AA to LTA4, which is subsequently catalyzed by LTA4H to produce LTB4. LTB4 is secreted by macrophages, binds to BLT1 on PAECs, and inhibits the Sphk1-eNOS survival signal in the PAEC. LTB4 signaling through BLT1 also promotes PASMC proliferation and hypertrophy. (C) This process causes accelerated endothelial cell apoptosis and smooth muscle cell layer growth. (D) Ongoing endothelial apoptosis and smooth muscle growth can result in luminal occlusion and PH.

Macrophages are prominent in the inflammatory infiltrate of plexiform lesions in PH (5, 6, 15), and our data now show that macrophages, isolated from diseased lungs, can induce apoptosis of endothelial cells from pulmonary vessels. Activated iNOS+ p5-LO+ macrophages are concentrated close to arterioles in rat PH lungs, a finding indicating that LTB4-producing cells are found close to the site of disease. Increased iNOS expression in infiltrating macrophages did not correlate with increased lung NO release in SU-induced PH (lung NO liberation was generally decreased in PH lung from these animals). Decreased NO in endothelial cells can promote smooth muscle cell growth (43). Because NO produced by iNOS reacts with superoxide to form peroxynitrite that can also damage endothelial cells (44), we assessed ROS and determined that there was indeed globally increased oxidative stress in the lungs of PH rats. However, in vitro experiments showed that antioxidant NAC treatment did not inhibit macrophage-derived LTB4 from inducing PAEC apoptosis. Because in vitro experiments showed that culture of PAECs with exogenous LTB4 at concentrations similar to those found in the PH BALF was also sufficient to cause >50% PAEC apoptosis at 24 hours (compared to <5% without LTB4), we conclude that LTB4 is sufficient, even in the absence of oxidative stress, to cause significant endothelial injury.

We also demonstrate that LTB4, secreted by activated macrophages, induces apoptosis by ligating its cognate high-affinity heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide–binding protein (G protein)–coupled receptor, BLT1, on PAECs. Transfected pulmonary macrophages that express activated p5-LO and secrete high levels of LTB4 effectively induce endothelial cell apoptosis, whereas transfected macrophages that secrete less LTB4 do not. Macrophages also directly contribute to endothelial cell death in the vascular regression that occurs in normal fetal development (45) and in the plaque disruption complicating coronary artery disease (46). Because BALF levels of LTB4 were high and because transfected macrophages that produce abundant LTB4 caused PAEC apoptosis, we conclude that LTB4 is likely responsible for lung vascular injury in our athymic PH animals. The fact that macrophage depletion prevented SU-induced PH in athymic rats is consistent with the notion that macrophage-derived LTB4 contributes to the pathogenesis of this form of experimental PH. Macrophages have been similarly implicated in models of hypoxia-induced PH (47) and the hepatopulmonary syndrome (48). The difficulty in replicating clinical pathology of PH in mice compared to rats may in part reflect the fact that mouse macrophages produce much less LTB4 and relatively more CysLTs (23) than do macrophages from rats (24) or humans (22).

LTB4 is well established as an enhancer of vascular permeability (49, 50), and its abundance in human atherosclerotic lesions correlates with symptoms of plaque instability (51). To explain our findings that LTB4 induces endothelial apoptosis, we evaluated a pathway used by vasoprotective prostaglandins, namely, Sphk1 and downstream eNOS (30, 52). Recent studies on S1P have demonstrated that this bioactive sphingolipid is an important negative regulator of vascular permeability in vivo (53), as well as an enhancer of endothelial survival mediated through eNOS and prostacyclin (30). We show that LTB4 induces PAEC apoptosis by inhibiting the expression of both Sphk1 and eNOS and that LTB4 induces PASMC proliferation and hypertrophy in a dose- and BLT1-dependent manner. The thickening of the PASMC layer in PH is likely from excess augmentation of proliferation, hypertrophy, migration, as well as depressed apoptosis (54–59). These results with LTB4 are consistent with the established effects of LTB4 on other types of vascular smooth muscle cells. For example, LTB4 has been implicated in atherogenesis, and BLT1 expression is increased in atherosclerotic plaques and on smooth muscle cells under inflammatory stress (29, 60). LTB4 induces signaling through nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)–dependent BLT1 receptors on coronary smooth muscle cells and causes increased proliferation and migration (29). LTB4 effects on PAECs and PASMCs are opposite to those induced by normal BMP signaling, which promotes PAEC health and suppresses aberrant PASMC growth (61, 62).

We show that blocking LTB4 action with two chemically distinct LTA4H inhibitors or with a BLT1 antagonist is an effective treatment for PH in immune-dysregulated rats. Bestatin therapy was also effective in the MCT rat model, results reminiscent of those of a previous study in which a BLT1 blocker reversed disease (63). Lung histology in our treated athymic animals revealed the opening of obliterated pulmonary arterioles as well as a decrease in the number of LTA4H+ macrophages, which otherwise rim the diseased arterioles. Bestatin therapy induced apoptosis in the smooth muscle and intimal layers of these vessels. Whether it was the antiproliferative effects of bestatin [which makes it useful as a chemotherapy adjuvant (64)] or its ability to limit LTB4-mediated PAEC apoptosis and PASMC proliferation/hypertrophy, the net effect of bestatin therapy was to reverse vessel remodeling.

In most of the human lungs that we examined, plexiform lesions exhibited pronounced infiltration of LTA4H+ macrophages around occluded arterioles. In both human lungs and animals, aberrant lumen-occluding endothelial cells were also LTA4H+, suggesting that LTB4 concentrations are high at the epicenter of PH pathology. Cells (especially macrophages) that express all the enzymes necessary for the production of LTB4 can directly synthesize LTB4, whereas cells like endothelial cells, which express little 5-LO (65), can use a transcellular synthetic pathway to generate LTB4. In our model used, this could involve LTA4 released by p5-LO–abundant macrophages and its uptake and subsequent hydrolysis by LTA4H-expressing PAECs. Therefore, as disease advances, LTB4 can be generated by macrophages acting both alone and with the cooperation of aberrant PAECs. Increased PAEC expression of 5-LO has been observed in iPAH, and these abnormal intimal cells could also serve as a source of LTA4 (15).

Serum levels of LTB4 were significantly elevated in PAH patients, especially in those with connective tissue disease–associated PAH (CTD-PAH). The half-life of LTB4 is only several minutes (66), and it is unknown how well serum LTB4 approximates lung LTB4 levels. In a smaller cohort of PAH patients, lung LTB4 levels were not significantly increased, although a trend toward increased LTB4 was seen in secondary PAH patients, a group that presumably included CTD-PAH patients (67). Dysregulated lung macrophages may be an important source of systemic LTB4 in these CTD patients. For example, CTD conditions associated with PAH, such as lupus and systemic sclerosis, exhibit defective Treg function (39, 68), which may facilitate the inappropriate activation of macrophages in these conditions (69, 70). This decrease in pulmonary Tregs also characterizes iPAH (71), another disease with clear autoimmune features (72) and activated pulmonary macrophages (15) exhibiting potentially aberrant function (73). Our results also show that macrophage-rich pulmonary inflammation and elevated systemic LTB4 levels do not occur in all PAH patients. Similarly, the SU/chronic hypoxia model of PH does not exhibit the same degree of macrophage infiltration, high LTB4 levels, and responsiveness to anti-LTB4 therapy as athymic rats. Collectively, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that different forms of PH have distinct etiologies. It should be possible to delineate and interpret preclinical PH animal models based on their comparison to human disease subtypes.

Although we show that LTA4H inhibition abrogates endothelial injury, the mechanisms by which this therapy actually reverses established PH may involve other LTB4-relevant pathways not examined here. For example, LTB4 also causes myoblast proliferation (74) and, acting on vascular smooth muscle cells through BLT1 receptors, induces smooth muscle cell chemotaxis and proliferation in the intimal hyperplasia of atherosclerosis (29). Additionally, LTA4H antagonism can attenuate inflammation in experimental allergic airway disease (35), a phenomenon possibly attributable to increased LXA4, an important controller of inflammation in this condition (75). LTA4H is also a target for cancer prevention and therapy, and LTA4H inhibitors have been useful in malignancies associated with chronic inflammation (76). The proliferation of endothelial cells in PH has been described by some investigators as having a quasi-malignant character (77, 78). Therefore, in addition to blocking endothelial apoptosis, inhibiting LTB4 biosynthesis may help reverse established PH by inducing apoptosis of the remodeled vascular wall, blocking disordered VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, reducing smooth muscle hyperplasia, dampening perivascular inflammation, and inhibiting abnormal endothelial cell proliferation.

Macrophage-derived LTB4 leads to endothelial cell death and appears to contribute to the development of immune dysregulation–associated PH. The effectiveness of LTA4H inhibition in reducing macrophage infiltration and reversing established disease likely involves the prevention of LTB4 biosynthesis by macrophages; LTB4 is itself a promoter of pulmonary macrophage infiltration (79). The ability of LTA4H inhibitors and a BLT1 receptor blocker to reverse severe PH supports the hypothesis that reducing LTB4 signaling has broader action than merely acting as an anti-inflammatory agent because these therapies also appear to promote the reopening of obliterated lung vessels. Bestatin also has antitumor activity and has been used in chemotherapy regimens in leukemia (80) and as a well-tolerated adjuvant therapy in stage I lung cancer (81). Therefore, clinical use of bestatin for the treatment of PH is possible. In keeping with the evolving concept of precision medicine, LTB4 antagonism may be a highly effective therapy for a subset of PH patients with concomitant immune dysregulation; in such patients, LTB4 levels in the blood or breath could serve as a useful biomarker predicting responsiveness to therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We mainly used an animal model of PH with dysregulated immunity (the SU-treated athymic rat) to study the role of macrophage LTB4 in disease pathogenesis to determine whether LTB4 secreted by infiltrating macrophages was directly injurious to pulmonary arterial endothelium. We used cocultures of macrophages from PH lungs and PEACs, some of which were engineered to mimic specific 5-LO phosphorylation states. Effects of LTB4 were tested in the MCT and SU/hypoxia models of rat PH. We also studied how LTB4 inhibition altered PH development and progression in vivo, and we examined human PAH lungs and serum for evidence of this LTB4 involvement. Animals were randomly assigned to experimental groups based on the weight at the time of SU or vehicle treatment. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Animal model

The experimental protocol was approved by the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Animal Care and Use Committee. Athymic nude rats (rnu/rnu; Charles River Laboratories) were used for these studies. Six- to 8-week-old animals were injected subcutaneously with a single dose of either SU (10 mg/kg) dissolved in DMSO or DMSO (vehicle) alone. All animals were maintained under normoxic conditions. Bestatin was injected intraperitoneally or given by inhalation three times per week starting at the time of SU administration or 1, 2, or 3 weeks after SU administration. Oral bestatin, JNJ-26993135, and other eicosanoid inhibitors were administered daily 3 weeks after SU injection. Detailed dosing regimen is listed in table S2.

Immunohistochemistry, Western blot, and flow cytometry

Procedures were described previously in (4). The following antibodies were used for immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, and flow cytometry: anti-CD68 (ED-1; AbD Serotec), anti-CD45RA (OX-33; AbD Serotec), anti-CD31 (TLD-3A12; AbD Serotec), anti–rat mast cells (AR32AA4; BD Pharmingen), anti–5-LO (3289; Cell Signaling Technology), anti–pSer271 5-LO (3748; Cell Signaling Technology), anti–cleaved caspase-3 (9664; Cell Signaling Technology), anti–pSer225 Sphk1 (SP1641; eBioscience), anti-Sphk1 (3297; Cell Signaling Technology), anti–pSer1177 eNOS (9571; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-eNOS (ab66127; Abcam), anti-LTA4H (TA500665; OriGene), anti-iNOS (ab3523; Abcam), and anti-PCNA (ab15487; Abcam). Western blots were quantified with the densitometry analysis function of ImageJ software.

BALF preparation

The rats were euthanized. A tracheal cannula was inserted, and the lung was lavaged with ice-cold Ca2+/Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a volume of 6 ml for the first lavage and 8 ml for subsequent lavages. BALF samples were centrifuged at 500g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet the cells. Supernatants were collected for LC-MS/MS assay.

Isolation of interstitial macrophages

Isolation of interstitial macrophagess was performed according to published methods (82). After exhaustive lung lavage (~30 times), the pulmonary artery was cannulated and the left atrium was opened. The lung vascular bed was perfused with ice-cold PBS-EDTA until the tissue turned white; this step was followed by perfusion with RPMI 1640 containing deoxyribonuclease (66 U/ml) and collagenase (50 U/ml). Lungs were then excised, and the tissues were sliced into 0.4-mm pieces. The lung tissue fragments were incubated with RPMI 1640 containing collagenase (50 U/ml) and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) for 60 min at 37°C in a gently shaking water bath. The lung-digested cells were then washed and layered on top of a two-step Percoll gradient (20 to 50%). After centrifugation at 300g, the interphase between the 20 and 50% Percoll layers was harvested, washed again, and resuspended in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS. To further enrich the isolated cells for macrophages, we seeded cells on petri dishes and washed them carefully after 5 hours of incubation period. The remaining cells were >95% macrophages as determined by flow cytometry.

Isolation of alveolar macrophages in BALF

Rats were euthanized. A tracheal cannula was inserted, and the lung was lavaged with ice-cold Ca2+/Mg2+-free PBS at a volume of 6 ml for 18 times. The alveolar macrophages were retrieved from the lavage effluents by centrifuging at 300g for 10 min. The cells were washed twice and resuspended to 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS and plated on petri dishes. Five hours after attaching, the remaining cells were >95% macrophages as determined by flow cytometry.

Transfection of macrophages

Eight hours after attaching, macrophages were trypsinized from the petri dish and resuspended to a concentration of 1 × 106/ml of transfection solution. Five micrograms of pEGFP-C1 vector (a gift from W. Cho, University of Illinois at Chicago), wild-type 5-LO, S271E, or S271A DNA was added to 100 µl of each of the macrophage suspensions. Mixtures were loaded into the cuvette, followed by preprogrammed transfection with 3D Nucleofactor (Lonza). Transfection efficiency was determined the next day with flow cytometry gated on the EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) channel.

Determination of medial wall thickness

Frozen sections of the lung were fixed and blocked with 10% donkey serum in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin. The tissue sections were then incubated with anti-SMA (Abcam) primary antibody and biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by hematoxylin staining. The percentage of wall thickness was determined as described (83) and was as follows: % wall thickness = (WT1 + WT2)/(external diameter of vessel) × 100, where WT1 and WT2 refer to wall thicknesses measured at two points diametrically opposite to each other. The endothelial component of the vessel wall was excluded from the measurements of wall thickness.

Degree of muscularization

To determine the degree of muscularization, we identified vessels <100 µm with positive α-SMA cell staining surrounding endothelial cells and classified them as follows: none, partially muscularized, or fully muscularized. The degree of muscularization was expressed as % ratio of number of vessels to the number of total vessels.

PAEC apoptosis assay

Rat PAECs were cocultured with macrophages (+/− transfection) for 24 hours. They were then washed once with PBS and once with binding buffer from the Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (88-8007; eBioscience). Cells were then suspended in binding buffer at 1 × 106 to 5 × 106/ml. Allophycocyanin-conjugated annexin V (5 µl) was added to 100 µl of cells and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Propidium iodide staining solution (5 µl) was added 5 min before flow cytometry analysis on the LSRFortessa cell analyzer (BD Biosciences). Serum starvation for 24 hours was performed to synchronize PAEC.

hPASMC proliferation assay

In Vitro Toxicology Assay Kit, MTT based (#M-5655, #8910, Sigma) was used to measure the number of viable hPASMC after LTB4 treatment. Briefly, hPASMCs were plated on a 96-well plate 2 days before treatment. hPASMCs were serum-starved for 24 hours before they were treated with 200 nM LTB4, 400 nM LTB4, or 200 nM LTB4 and 1 mM U75302 for 24 hours. On the day of assay, growing medium was first removed from the cell. Twenty microliters of 12 mM MTT solution was then added to each well. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. MTT dissolving solution (200 µl) (10% Triton X-100 plus 0.1 N HCl in anhydrous isopropanol) was then added to each well. Relative optical density used as an index for proliferation was calculated by subtracting the absorbance at 690 nm from that at 570 nm.

hPASMC hypertrophy

Cellular hypertrophy was determined by calculating protein/DNA ratio. Briefly, hPASMCs were seeded on six-well plates 2 days before treatment. hPASMCs were serum-starved for 24 hours before they were treated with 200 nM LTB4, 400 nM LTB4, or 200 nM LTB4 plus 1 mM U75302 for 24 hours. hPASMCs were then collected and divided into two. For one portion of the sample, BCA protein assay (#23227, Thermo Scientific) was used to determine the total protein amount. DNA was purified from the other part of the sample with Miniprep (Qiagen). DNA concentration was measured by NanoDrop. Protein/DNA ratio was then calculated.

NO production assay

The Nitric Oxide Synthase Detection Kit (Cell Technology Inc.) was used to detect the cellular NO production in the cocultured medium. Briefly, rat PAECs were washed with PBS once before adding 1× DAF-2DA, a cell-permeable reagent that measures free NO and NOS activity. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 60 min and read on a fluorescent plate reader at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and emission wavelength of 515 nm.

Measurements of hemodynamics

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (70 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) injected intraperitoneally before right heart catheterization. RVSP measurements were obtained by insertion of a microtip pressure transducer (model SPR-671, 1.4F; Millar Instruments) through the jugular vein into the RV. Signals were recorded continuously with a TC-510 pressure control unit 236927/R1 7 (Millar Instruments) coupled to a Bridge Amp (AD Instruments). Data were collected with the PowerLab 4/30 data acquisition system (AD Instruments) and analyzed with Chart Pro software (AD Instruments). The RV was dissected from the left ventricle (LV) and septum (S) and each was weighed. The Fulton index [RV/(LV + S)] was calculated to determine the degree of RVH.

Echocardiography

Echocardiographic evaluation of RV dimensions and pulmonary hemodynamics was performed with the Vivid 7 Dimension Cardiovascular Imaging System (GE), equipped with a 14-MHz transducer. Rats were lightly sedated with isoflurane for the duration of the procedure. The chests were depilated before obtaining echocardiographies. The rats were laid supine on a warming handling platform. Pulmonary artery Doppler tracings were obtained from the pulmonary artery parasternal short-axis views. The RV free wall was imaged from a modified parasternal long-axis view. All measurements were made in the expiratory phase of the respiratory cycle.

Immunohistochemistry of human tissue

Paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed human lung tissues from two healthy control subjects and six PAH patients were obtained from the Pulmonary Hypertension Breakthrough Initiative Tissue Bank at Stanford. Antigen retrieval was performed by steaming the slides for 20 min in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and then blocked with 1% normal swine serum (NSS) for 15 min. The slides were incubated with anti–5-LO (1:25, Cell Signaling Technology), anti–pSer271 5-LO (1:20, Abcam), or anti-LTA4H (1:50, LifeSpan Biosciences Inc.) in 1% NSS overnight at 4°C, followed by anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (1:100, Invitrogen) for 4 hours at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with anti-mouse CD68 (1:50, LifeSpan Biosciences) overnight at 4°C in PBS, followed by anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (1:100, Invitrogen) for 4 hours at room temperature. Negative controls with isotype immunoglobulin G were run in parallel. Images were acquired by laser-scanning confocal microscopy with a Leica TCS-SP2 confocal microscope and analyzed with ImageJ.

Human serum LTB4 measurements

The full methods are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods. Briefly, serum from de-identified healthy controls and patients with iPAH and CTD-APAH was procured from the Institutional Review Board–approved Stanford Pulmonary Hypertension Biobank. Serum LTB4 was isolated with solid-phase extraction and quantified with LC-MS/MS. Serum LTB4 levels were measured for normality with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and mean values were compared across cohorts using nonparametric one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal-Wallis test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Statistics

Prism 5 (GraphPad) was used for all analyses. Values are presented as means ± SEM. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate the data for normal distribution. Differences between various groups at multiple time points were compared with two-way ANOVA, with Bonferroni multiple comparison test for post hoc analyses. For comparisons between multiple experimental groups at a single time point, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for post hoc analyses was used. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Cho at the University of Illinois for providing the 5-LO plasmids and mutants, T. Saito for assistance with human studies, and S. Manikkam and B. Fitch of BioAdd (Stanford) for LT analyses.

Funding: This study was supported by NIH grants HL082662 and HL095686 (to M.R.N.), HL058897 (to M.P.-G.), and RO3HL110822 (to M.R.) and Stanford National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Proteomics Center NHLBI-HV-10-05. Human lung microscopy was performed at the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology Microscopy Facility, supported, in part, by funding from NIH–National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Center Core grant (5P30NS047463-02).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/5/200/200ra117/DC1

Materials and Methods

Fig. S1. Increased macrophage 5-LO during the evolution of experimental PH.

Fig. S2. Tissue-specific 5-LO expression in experimental PH.

Fig. S3. Increased nuclear membrane–translocated p5-LO over time as an indicator for 5-LO activation.

Fig. S4. High concentration of iNOS+ macrophages around occluded arterioles.

Fig. S5. In vivo NO release decreased in lungs from PH rats.

Fig. S6. Cellular ROS production is elevated in the SU group.

Fig. S7. Prevention of PH by macrophage depletion.

Fig. S8. Induction of PAEC apoptosis by interstitial lung macrophage (IMØ)–derived LTB4.

Fig. S9. Experimental groups of PAEC-macrophage coculture system.

Fig. S10. Induction of PAEC apoptosis by alveolar macrophage (AMØ)–derived LTB4.

Fig. S11. LTB4 induction of PAEC apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner.

Fig. S12. LTB4 induction of synchronized PAEC apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner.

Fig. S13. S1P rescues PAEC apoptosis induced by macrophage LTB4.

Fig. S14. Quantification of Western blots evaluating LTB4-mediated PAEC apoptosis.

Fig. S15. The reversal of established PH by administration of bestatin 3 weeks after SU administration.

Fig. S16. The improvement of right heart function of PH animals undergoing blockade of LTB4 signaling.

Fig. S17. The dose-dependent reversal of established PH using novel oral formulations of bestatin.

Fig. S18. The reversal of established PH using a novel formulation of inhaled bestatin.

Fig. S19. Blocking multiple eicosanoid pathways in the SU/athymic rat PH model.

Fig. S20. Reduction of disease-related LTA4H expression in macrophages in bestatin-treated rats.

Fig. S21. Inflammation attenuation in bestatin-treated animals.

Fig. S22. Prevention of PH lung macrophage–induced PAEC apoptosis with bestatin.

Fig. S23. Reestablishing lung Sphk1-eNOS signaling with bestatin treatment in established PH.

Fig. S24. Prevention of mutant-mimic macrophage-induced PAEC apoptosis and maintenance of Sphk1-eNOS signaling with exogenous bestatin.

Fig. S25. The induction of cellular apoptosis in remodeled PH vessel wall 1 week after bestatin treatment.

Fig. S26. The reversal of PH in the MCT model using bestatin therapy.

Fig. S27. The failure of bestatin in the low-LTB4 SU/hypoxia PH model.

Table S1. Hemodynamic and echocardiographic data for athymic rats at different time points after SU administration.

Table S2. Dosing regimen for different eicosanoid inhibitors.

Author contributions: W.T. designed and performed the experiments and helped write the manuscript. X.J. designed and performed the experiments and helped write the manuscript. R.T. designed and performed the experiments. Y.K.S. performed the experiments and helped write the manuscript. J.Q. designed and performed the experiments and helped write the manuscript. G.D. performed statistical analyses and helped write the paper. L.G. synthesized the VEGFR2 antagonist. L.F. designed and performed the experiments and helped write the manuscript. M.R. helped write the manuscript. R.T.Z. conducted human LTB4 analysis experiment and helped write the manuscript. M.I. created bestatin formulations and helped synthesize JNJ-26993135 and LY293111. M.F. performed LC-MS/MS studies. J.R. designed the experiments and helped write the manuscript. M.P.-G. helped design the experiments and write the manuscript. N.F.V. designed the experiments and helped write the manuscript. M.R.N. helped design the experiments and write the manuscript.

Competing interests: M.P.-G. has been a member of the Respiratory Advisory Board for Merck and a paid consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Nycomed/Takeda, Ono, and Sanofi. R.T.Z. is on the United Therapeutics CHARTER Advisory Board and has been a paid consultant for Gilead Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Ikeria, and Actelion. Y.K.S. has been a paid consultant for Hudson Global. W.T., J.R., and M.R.N. and Stanford University (OTL #S11-438) have a patent pending concerning the use of LTB4 antagonists for the treatment of PAH.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Wilkins MR, Grimminger F. Mechanisms of disease: Pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2011;8:443–455. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolls MR, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Rai PR, Badesch DB, Voelkel NF. Autoimmunity and pulmonary hypertension: A perspective. Eur. Respir. J. 2005;26:1110–1118. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00045705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassoun PM, Mouthon L, Barberà JA, Eddahibi S, Flores SC, Grimminger F, Jones PL, Maitland ML, Michelakis ED, Morrell NW, Newman JH, Rabinovitch M, Schermuly R, Stenmark KR, Voelkel NF, Yuan JX, Humbert M. Inflammation, growth factors, and pulmonary vascular remodeling. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54:S10–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamosiuniene R, Tian W, Dhillon G, Wang L, Sung YK, Gera L, Patterson AJ, Agrawal R, Rabinovitch M, Ambler K, Long CS, Voelkel NF, Nicolls MR. Regulatory T cells limit vascular endothelial injury and prevent pulmonary hypertension. Circ. Res. 2011;109:867–879. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.236927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuder RM, Voelkel NF. Pulmonary hypertension and inflammation. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1998;132:16–24. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(98)90020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorfmüller P, Perros F, Balabanian K, Humbert M. Inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2003;22:358–363. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00038903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Nicolls MR, Kraskauskas D, Scerbavicius R, Burns N, Cool C, Wood K, Parr JE, Boackle SA, Voelkel NF. Absence of T cells confers increased pulmonary arterial hypertension and vascular remodeling. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007;175:1280–1289. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1189OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters-Golden M, Henderson WR., Jr Leukotrienes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1841–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. 5-Lipoxygenase and FLAP. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2003;69:99–109. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werz O, Klemm J, Samuelsson B, Rådmark O. 5-Lipoxygenase is phosphorylated by p38 kinase-dependent MAPKAP kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050588997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werz O, Szellas D, Steinhilber D, Rådmark O. Arachidonic acid promotes phosphorylation of 5-lipoxygenase at Ser-271 by MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14793–14800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rådmark O, Samuelsson B. Regulation of the activity of 5-lipoxygenase, a key enzyme in leukotriene biosynthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;396:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo M, Jones SM, Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. Nuclear localization of 5-lipoxygenase as a determinant of leukotriene B4 synthetic capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:12165–12170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133253100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flamand N, Luo M, Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. Phosphorylation of serine 271 on 5-lipoxygenase and its role in nuclear export. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:306–313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805593200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright L, Tuder RM, Wang J, Cool CD, Lepley RA, Voelkel NF. 5-Lipoxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase activating protein (FLAP) immunoreactivity in lungs from patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998;157:219–229. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9704003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voelkel NF, Tuder RM, Wade K, Höper M, Lepley RA, Goulet JL, Koller BH, Fitzpatrick F. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein (FLAP) reduces pulmonary vascular reactivity and pulmonary hypertension in hypoxic rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:2491–2498. doi: 10.1172/JCI118696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song Y, Jones JE, Beppu H, Keaney JF, Jr, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY. Increased susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in heterozygous BMPR2-mutant mice. Circulation. 2005;112:553–562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stenmark KR, James SL, Voelkel NF, Toews WH, Reeves JT, Murphy RC. Leukotriene C4 and D4 in neonates with hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983;309:77–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307143090204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peck MJ, Piper PJ, Williams TJ. The effect of leukotrienes C4 and D4 on the microvasculature of guinea-pig skin. Prostaglandins. 1981;21:315–321. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(81)90149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Kasahara Y, Alger L, Hirth P, Mc Mahon G, Waltenberger J, Voelkel NF, Tuder RM. Inhibition of the VEGF receptor 2 combined with chronic hypoxia causes cell death-dependent pulmonary endothelial cell proliferation and severe pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J. 2001;15:427–438. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0343com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer NR, Moore TM, McMurtry IF. Rodent models of PAH: Are we there yet? Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007;293:L580–L582. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00281.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balter MS, Eschenbacher WL, Peters-Golden M. Arachidonic acid metabolism in cultured alveolar macrophages from normal, atopic, and asthmatic subjects. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1988;138:1134–1142. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.5.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coffey MJ, Phare SM, Peters-Golden M, Huffnagle GB. Regulation of 5-lipoxygenase metabolism in mononuclear phagocytes by CD4 T lymphocytes. Exp. Lung Res. 1999;25:617–629. doi: 10.1080/019021499270051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters-Golden M, McNish RW, Hyzy R, Shelly C, Toews GB. Alterations in the pattern of arachidonate metabolism accompany rat macrophage differentiation in the lung. J. Immunol. 1990;144:263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sindrilaru A, Peters T, Wieschalka S, Baican C, Baican A, Peter H, Hainzl A, Schatz S, Qi Y, Schlecht A, Weiss JM, Wlaschek M, Sunderkötter C, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. An unrestrained proinflammatory M1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:985–997. doi: 10.1172/JCI44490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holt PG, Degebrodt A, Venaille T, O’Leary C, Krska K, Flexman J, Farrell H, Shellam G, Young P, Penhale J, Robertson T, Papadimitriou JM. Preparation of interstitial lung cells by enzymatic digestion of tissue slices: Preliminary characterization by morphology and performance in functional assays. Immunology. 1985;54:139–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franke-Ullmann G, Pförtner C, Walter P, Steinmüller C, Lohmann-Matthes ML, Kobzik L. Characterization of murine lung interstitial macrophages in comparison with alveolar macrophages in vitro. J. Immunol. 1996;157:3097–3104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonizzi G, Piette J, Schoonbroodt S, Greimers R, Havard L, Merville MP, Bours V. Reactive oxygen intermediate-dependent NF-κB activation by interleukin-1β requires 5-lipoxygenase or NADPH oxidase activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:1950–1960. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bäck M, Bu DX, Bränström R, Sheikine Y, Yan ZQ, Hansson GK. Leukotriene B4 signaling through NF-κB-dependent BLT1 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis and intimal hyperplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:17501–17506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505845102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodríguez C, González-Díez M, Badimon L, Martínez-González J. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: A bioactive lipid that confers high-density lipoprotein with vasculoprotection mediated by nitric oxide and prostacyclin. Thromb. Haemost. 2009;101:665–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orning L, Krivi G, Fitzpatrick FA. Leukotriene A4 hydrolase. Inhibition by bestatin and intrinsic aminopeptidase activity establish its functional resemblance to metallohydrolase enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:1375–1378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muskardin DT, Voelkel NF, Fitzpatrick FA. Modulation of pulmonary leukotriene formation and perfusion pressure by bestatin, an inhibitor of leukotriene A4 hydrolase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;48:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scornik OA, Botbol V. Bestatin as an experimental tool in mammals. Curr. Drug Metab. 2001;2:67–85. doi: 10.2174/1389200013338748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rao NL, Riley JP, Banie H, Xue X, Sun B, Crawford S, Lundeen KA, Yu F, Karlsson L, Fourie AM, Dunford PJ. Leukotriene A4 hydrolase inhibition attenuates allergic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010;181:899–907. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1158OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyata M, Sakuma F, Ito M, Ohira H, Sato Y, Kasukawa R. Athymic nude rats develop severe pulmonary hypertension following monocrotaline administration. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2000;121:246–252. doi: 10.1159/000024324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Speich R, Jenni R, Opravil M, Pfab M, Russi EW. Primary pulmonary hypertension in HIV infection. Chest. 1991;100:1268–1271. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonelli M, Savitskaya A, Steiner CW, Rath E, Smolen JS, Scheinecker C. Phenotypic and functional analysis of CD4+CD25−Foxp3+ T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2009;182:1689–1695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radstake TR, van Bon L, Broen J, Wenink M, Santegoets K, Deng Y, Hussaini A, Simms R, Cruikshank WW, Lafyatis R. Increased frequency and compromised function of T regulatory cells in systemic sclerosis (SSc) is related to a diminished CD69 and TGFβ expression. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Covas MI, Esquerda A, García-Rico A, Mahy N. Peripheral blood T-lymphocyte subsets in autoimmune thyroid disease. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 1992;2:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mandl T, Bredberg A, Jacobsson LT, Manthorpe R, Henriksson G. CD4+ T-lymphocytopenia— A frequent finding in anti-SSA antibody seropositive patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 2004;31:726–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papo T, Piette JC, Legac E, Frances C, Grenot P, Debre P, Godeau P, Autran B. T lymphocyte subsets in primary antiphospholipid syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 1994;21:2242–2245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeremy JY, Rowe D, Emsley AM, Newby AC. Nitric oxide and the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;43:580–594. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia Y, Zweier JL. Superoxide and peroxynitrite generation from inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:6954–6958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lang RA, Bishop JM. Macrophages are required for cell death and tissue remodeling in the developing mouse eye. Cell. 1993;74:453–462. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80047-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugiyama S, Kugiyama K, Aikawa M, Nakamura S, Ogawa H, Libby P. Hypochlorous acid, a macrophage product, induces endothelial apoptosis and tissue factor expression: Involvement of myeloperoxidase-mediated oxidant in plaque erosion and thrombogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:1309–1314. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000131784.50633.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vergadi E, Chang MS, Lee C, Liang OD, Liu X, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Mitsialis SA, Kourembanas S. Early macrophage recruitment and alternative activation are critical for the later development of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2011;123:1986–1995. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.978627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thenappan T, Goel A, Marsboom G, Fang YH, Toth PT, Zhang HJ, Kajimoto H, Hong Z, Paul J, Wietholt C, Pogoriler J, Piao L, Rehman J, Archer SL. A central role for CD68(+) macrophages in hepatopulmonary syndrome. Reversal by macrophage depletion. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;183:1080–1091. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201008-1303OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Björk J, Hedqvist P, Arfors KE. Increase in vascular permeability induced by leukotriene B4 and the role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Inflammation. 1982;6:189–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00916243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Gennaro A, Kenne E, Wan M, Soehnlein O, Lindbom L, Haeggström JZ. Leukotriene B4-induced changes in vascular permeability are mediated by neutrophil release of heparin-binding protein (HBP/CAP37/azurocidin) FASEB J. 2009;23:1750–1757. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiu H, Gabrielsen A, Agardh HE, Wan M, Wetterholm A, Wong CH, Hedin U, Swedenborg J, Hansson GK, Samuelsson B, Paulsson-Berne G, Haeggström JZ. Expression of 5-lipoxygenase and leukotriene A4 hydrolase in human atherosclerotic lesions correlates with symptoms of plaque instability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:8161–8166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602414103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chalfant CE, Spiegel S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and ceramide 1-phosphate: Expanding roles in cell signaling. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:4605–4612. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L, Dudek SM. Regulation of vascular permeability by sphingosine 1-phosphate. Microvasc. Res. 2009;77:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michelakis ED, McMurtry MS, Wu XC, Dyck JR, Moudgil R, Hopkins TA, Lopaschuk GD, Puttagunta L, Waite R, Archer SL. Dichloroacetate, a metabolic modulator, prevents and reverses chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats: Role of increased expression and activity of voltage-gated potassium channels. Circulation. 2002;105:244–250. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.101974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMurtry MS, Bonnet S, Wu X, Dyck JR, Haromy A, Hashimoto K, Michelakis ED. Dichloroacetate prevents and reverses pulmonary hypertension by inducing pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Circ. Res. 2004;95:830–840. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145360.16770.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McMurtry MS, Archer SL, Altieri DC, Bonnet S, Haromy A, Harry G, Puttagunta L, Michelakis ED. Gene therapy targeting survivin selectively induces pulmonary vascular apoptosis and reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1479–1491. doi: 10.1172/JCI23203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merklinger SL, Jones PL, Martinez EC, Rabinovitch M. Epidermal growth factor receptor blockade mediates smooth muscle cell apoptosis and improves survival in rats with pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2005;112:423–431. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang Q, Lu Z, Ramchandran R, Longo LD, Raj JU. Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration in fetal lambs acclimatized to high-altitude long-term hypoxia: Role of histone acetylation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2012;303:L1001–L1010. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00092.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang J, Jiang Q, Wan L, Yang K, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Wang E, Lai N, Zhao L, Jiang H, Sun Y, Zhong N, Ran P, Lu W. Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate inhibits canonical transient receptor potential expression in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle from pulmonary hypertensive rats. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013;48:125–134. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0071OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heller EA, Liu E, Tager AM, Sinha S, Roberts JD, Koehn SL, Libby P, Aikawa ER, Chen JQ, Huang P, Freeman MW, Moore KJ, Luster AD, Gerszten RE. Inhibition of atherogenesis in BLT1-deficient mice reveals a role for LTB4 and BLT1 in smooth muscle cell recruitment. Circulation. 2005;112:578–586. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.545616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alastalo TP, Li M, Perez Vde J, Pham D, Sawada H, Wang JK, Koskenvuo M, Wang L, Freeman BA, Chang HY, Rabinovitch M. Disruption of PPARγ/β-catenin–mediated regulation of apelin impairs BMP-induced mouse and human pulmonary arterial EC survival. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:3735–3746. doi: 10.1172/JCI43382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perez VA, Ali Z, Alastalo TP, Ikeno F, Sawada H, Lai YJ, Kleisli T, Spiekerkoetter E, Qu X, Rubinos LH, Ashley E, Amieva M, Dedhar S, Rabinovitch M. BMP promotes motility and represses growth of smooth muscle cells by activation of tandem Wnt pathways. J. Cell Biol. 2011;192:171–188. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tabata T, Ono S, Song C, Noda M, Suzuki S, Tanita T, Fujimura S. Role of leukotriene B4 in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;35:160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]