Nanomedicine seeks to manufacture drugs and other biologically relevant molecules that are packaged into nanoscale systems for improved delivery. This includes known drugs, proteins, enzymes, and antibodies that have limited clinical efficacy based on delivery, circulating half-lives, or toxicity profiles. The <100 nm nanoscale physical properties afford them a unique biologic potential for biomedical applications. Hence they are attractive systems for treatment of cancer, heart and lung, blood, inflammatory, and infectious diseases. Proposed clinical applications include tissue regeneration, cochlear and retinal implants, cartilage and joint repair, skin regeneration, antimicrobial therapy, correction of metabolic disorders, and targeted drug delivery to diseased sites including the central nervous system. The potential for cell and immune side effects has necessitated new methods for determining formulation toxicities. To realize the potential of nanomedicine from the bench to the patient bedside, our laboratories have embarked on developing cell-based carriage of drug nanoparticles to improve clinical outcomes in infectious and degenerative diseases. The past half decade has seen the development and use of cells of mononuclear phagocyte lineage, including dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages, as Trojan horses for carriage of anti-inflammatory and anti-infective medicines. The promise of this new technology and the perils in translating it for clinical use are developed and discussed in this chapter.

I. Translational Pathways for Cell-Based Nanomedicines

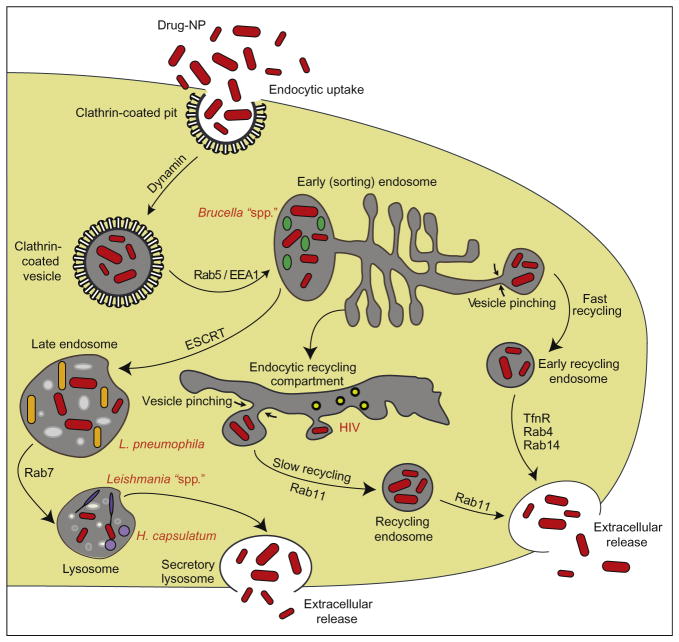

Evasion of mononuclear phagocytes’ (MP; monocyte, macrophage, and dendritic cell) antimicrobial immune responses, including complement, interferon, and phagolysomal fusion among others, represent effective strategies for any pathogen to circumvent immune defenses. Although microbes commonly secrete metabolites that can effect MP phagocytosis, in practice, this does little to impair this critical cell function.1–4 Indeed, pathogens are readily phagocytosed and enter phagosomes (Table I). This vesicle then undergoes a series of fission and fusion events, associated with alterations of the surrounding membrane and vacuolar content.1–3 The microbicidal microenvironment is associated with pH reduction, hydrolytic enzymes, defensins, and generation of toxic oxidative compounds. Many microbes have developed strategies to survive in MP and replicate intracellularly, including effecting the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Microbes use MP as “Trojan horses” for their dissemination while remaining undetected by host immune surveillance and entering into tissues including the central nervous system (CNS). Fusion of phagosomes with early or late endosomes and/or lysosomes occurs where microbes are destined for elimination and clearance. However, during chronic infection, the system breaks down and the microbe can survive in these compartments for months to years. Thus, the search for a means to best deliver antimicrobial drugs directly to organelles that harbor infection is critically important.5–8 We recently demonstrated that recycling endosomes harbor microbes such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) capable of pathogen replication. Interestingly, it is these exact compartments where drug-laden nanoparticles are directed (Fig. 1). This, at least in theory, provides a boost to microbial clearance in that the drug can be delivered to the site of active pathogen growth. Independent works were performed recently and in parallel within our laboratories demonstrating that catalase nanozymes can be used effectively for treatment of an experimental model of Parkinson’s disease (PD), leading to neuroprotective outcomes.10–13 These results taken together provide a clear path for translational studies in cell-based nanomedicine for human investigations and ultimate use (Fig. 2). The subsequent sections of this review outline the pathways through which this may be achieved. Reviews of the advances made in nanomedicine overall, with a particular focus on how they may be redirected for cell-based therapies, are illustrated.

TABLE I.

Therapies for Pathogen Sequestration in Mononuclear Phagocytes

| Pathogen | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Bacteria | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, streptomycin |

| Mycobacterium leprae | Dapsone, rifampicin, clofazimine |

| Legionella pneumophila | Azithromycin, moxifloxacin |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Penicillin, ampicillin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

| Brucella spp. | Streptomycin, doxycycline, gentamicin, rifampin, (ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole) |

| Salmonella spp. | Ampicillin, gentamicin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ceftriaxone, amoxicillin, or ciprofloxacin |

| Shigella spp. | Ampicillin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin |

| Coxiella burnetii | Tetracycline, doxycycline, erythromycin, rifampin, Q-vax vaccine (CSL) |

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum | Doxycycline, rifampin |

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis | Doxycycline, rifampicin |

| Bacillus anthracis | Penicillin, fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin), doxycycline |

| Francisella tularensis | Streptomycin, gentamicin, doxycycline, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | Chloramphenicol, florfenicol, tetracyclines, sulfonamide, nitrofuran derivatives, pyrodinecarboxylic acids |

| Rhodococcus equi | Erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, vancomycin, aminoglycosides, rifampin, imipenem, meropenem, linezolid, penicillin G, ampicillin, carbenicillin, cefazolin |

| Protozoa | |

| Leishmania spp. | Pentavalent antimonials (sodium stibogluconate, meglumine antimoniate), amphotericin B, paromomycin |

| Toxoplasma gondii |

Acute: pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, clindamycin, spiramycin Latent: atovaquone, clindamycin, Artemisia annua |

| Fungi | |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | Amphotericin B, itraconazole (1 year), ketoconazole (mild) |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B, flucytosine, AmBisome 4® |

| Viruses | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | Antiretroviral drugs (NRTIs, PIs, NNRTIs)a |

| Ross River virus | No specific antivirals, analgesics, anti-inflammatories, anti-pyretics |

| Dengue virus | No specific antivirals, acetaminophen |

| Human cytomegalovirus | Ganciclovir |

| Herpes Simplex virus type I/II | Acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir, penciclovir |

| Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus | Oseltamivir |

| Human T cell leukemia virus type 1 | Zidovudine, interferon alpha, CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), arsenic trioxide |

| Monkeypox virus | Smallpox vaccination preventative |

| Vaccinia virus | VIG (vaccinia immune globulin intravenous), cidofovir (proposed) |

NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Fig. 1.

Intracellular pathways of nanoparticles and pathogens in macrophages. Drug nanoparticles (shown in red) enter macrophages via clathrin-coated pits and are then transported to the early endosome compartment. From the early endosome compartment, the particles can have three different fates: (1) fast recycling via Rab4+ or 14+ endosomes; (2) trafficking to late endosomes, regulated in part by endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery for eventual release as a secretory lysosome; or (3) transport to the recycling endosome compartment where they will be stored for long periods and slowly recycled via Rab11+ endosomes. Pathogens are maintained in early endosomes (Brucella spp.), late endosomes (L. pneumophila), nonacidic lysosomes (Leishmania spp.; H. capsulatum), or recycling endosomes (HIV). (Figure adapted with permission from Ref. 9.)

Fig. 2.

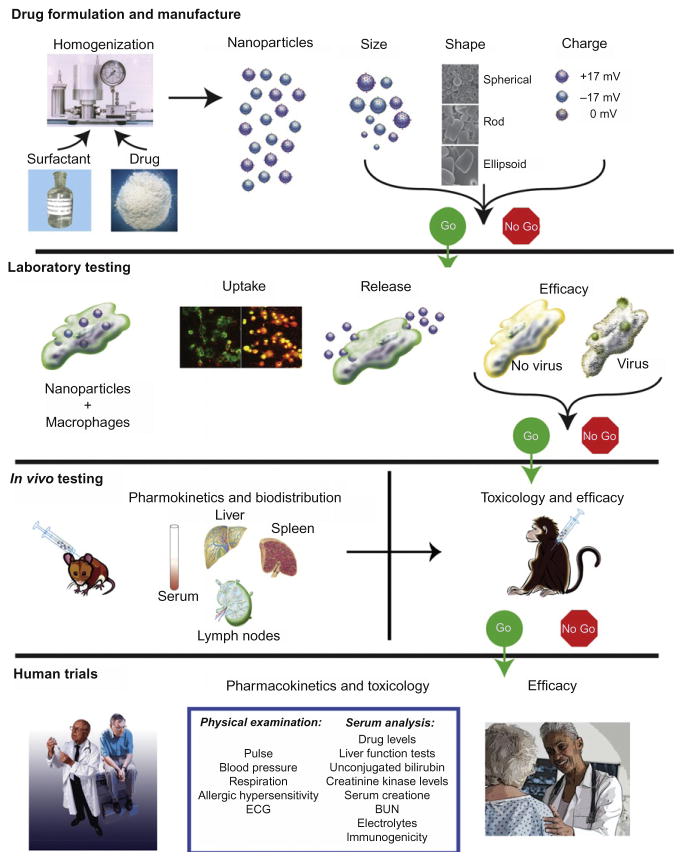

Bench-to-bedside development of nanoformulated drugs. Nanoformulated drugs hold considerable promise for treatment of human disease and their development for cell-based carriage is illustrated herein. Independent of application, neuroprotective or anti-inflammatory, antitumor, or antimicrobial agents are packaged into particles with surfactant coats that target circulating mono-nuclear phagocytes (MP; dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages). The nanoparticles (NPs) are developed dependent on size, shape, charge, and surfactant coating to facilitate uptake by MP. MP scavenge the particles and traffic them into endocytic compartments and as such act as delivery vehicles. Laboratory tests measure uptake and release of drug-NP. In the case of HIV-1 infection, the drug-NP housed in macrophages would release antiretroviral drugs, leading to inhibition of viral replication. This may be measured by attenuation of cytotoxicity including giant cell formulation, reverse transcriptase activity, and HIV-1 p24 antigen expression. Select formulations are used for drug pharmacokinetics (PK) and toxicology to demonstrate sustained drug levels and extended efficacy. Final therapeutic use in humans will be dependent upon toxicity measures, PK responses, hypersensitivity, immunogenicity, and other untoward side effects.

II. Nanomedicines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer, Infectious and Degenerative Diseases, and Tissue Repair

Nanomedicine research has focused, in large measure, on cancer and infectious diseases. Of the nanomedical products developed, reformulated pharmaceuticals remain in majority.14 Several are in clinical trials for bioimaging and cancer15 treatments. These include Doxil®, a polyethyleneglycol (PEG) liposomal version of the anticancer drug doxorubicin,16 Abraxane®, an albumin conjugated nanoparticle version of the anticancer drug paclitaxel, and Rapamune®, a micellar nanoformulation of rapamycin.17,18 These nanoformulated drugs have exhibited fewer unwanted side effects and improved therapeutic indices over their non-formulated drug counterparts.19–22

A. Cancer

The most highly studied area of nanoparticle drug delivery is in cancer treatment. A variety of nanoparticulate systems have been developed for cancer therapeutics including functionalized liposomes, albumin-based particles, polymeric micelles, dendrimers, gold nanoparticles, and cell-based nanoparticle delivery systems.23–25 Nanoformulations for delivery of the chemotherapeutic drugs doxorubicin and paclitaxel are Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved. PEGylated liposomal formulations of doxorubicin (Doxil®, Caelyx®) can extend the half-life of the drug dramatically and decrease the cardiotoxicity.23,25 The albumin-based paclitaxel nanoformulation Abraxane® targets tumor cells by engaging the endothelial gp60 receptor and the albumin-binding protein. Secondary toxicities are reduced compared to Cremophor® or ethanol drug suspensions.25 Recently, targeted multifunctional anticancer nanoparticles for tumor imaging and delivery were developed to track drug distribution and monitor therapeutic efficacy.25–28

B. Infectious Diseases

Nanosystems are being used or developed for treatment of infectious diseases. These include nanoemulsion, niosome (a nonionic surfactant-based liposome), polymeric nanoparticle, dendrimer, liposomal and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanobead delivery systems, RNA/siRNA nanoparticles, and DNA vaccines. In particular, antimicrobials are being placed into polymer-coated crystalline nanoparticles, homogenized particulate suspensions, cholesterol-conjugated amphiphilic peptide self-assembled particles, composite hydrogel/glass particles, liposomes, PLGA, cationic, and pDNA-coated gold nanoparticles, and developed for human treatment for a broad range of microbial infections including tuberculosis.29–41 Nanoformulated drugs are being designed to specifically deliver therapeutics to sites of infection and in regions of the body that are often difficult to reach using traditional or available treatments.

C. Degenerative Diseases

Use of nanoparticulate systems to treat autoimmune and neurodegenerative disorders include approaches for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. These include anti-TNF-α-Fab′ with a PEG block, soluble C60 fullerenes for their free radical scavenging abilities, targeted micelles of camptothecin, and N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymer–dexamethasone conjugate.42–45 In regard to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and PD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington’s disease, delivery systems are being manufactured to overcome the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and deliver drugs to the diseased areas of the brain. Metal chelators conjugated to nanoparticles cross the BBB and chelate metal ions in brains of AD patients and are designed to reduce amyloid-beta aggregates.46–48 Copolymeric N-isopropylacrylamide, N-tert-butylacrylamide nanoparticles, and N-acetyl-L-cysteine capped quantum dots also reduce amyloid-beta aggregation.49,50 Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers have been used to deliver bromocriptine and apomorphine to the brain and improve locomotor skills in animal models of PD.51,52 A nanoparticle delivery system for the human glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor gene improves locomotor activity, reduces dopaminergic neuronal loss, and enhances monoamine neuro-transmitter levels in a rat model of PD.53,54

D. Immunomodulation

Nanoformulated drugs and nanoparticle treatments can improve the efficacy of traditional immunosuppressants and regulate the host immune responses to reduce graft versus host disease. The rapamycin nanocrystalline formulation Rapamune® has greater efficacy over traditional rapamycin treatment as an immunosuppressant in transplant patients.17,55 Development of nanoformulations of rapamycin for use in arterial stents and for oral delivery has been described and tested in animal models of diseases.56,57 Other immunomodulatory strategies include targeting nanoparticles to dendritic cells to develop specific immune responses against cancer cells, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases.58,59

E. Regenerative Medicine and Facilitation of Wound Repair

Recent studies have described the use of nanoparticles for enhancing wound repair and tissue regeneration. Wigglesworth et al.60 reported that liposomes containing glycolipids with Gala1-3Galb1-4GlcNAc-R epitopes applied to skin wounds in mice induced local activation of complement and its chemotactic factors with resultant recruitment of macrophages. This resulted in a two fold increase in healing time. Kwan et al. described the use of silver nanoparticles to promote wound healing and improve the tensile properties of skin.61 Use of nanocomposites in scaffolds to promote bone and cartilage regeneration is under clinical trials.62,63 Lei et al. used caged nanoparticle encapsulation to load DNA/polyethyleneimine (PEI) polyplexes into hyaluronic acid and fibrin hydrogels for gene therapy.64 Others used nanotubes and nanofibers to promote axonal growth.65

F. Ocular Drug Delivery

The protective barriers of the eye make drug delivery difficult without tissue damage. Poor drug absorption and penetration of drugs to intraocular tissues limit the delivery of drugs. Use of nanoparticles and nanosuspensions for drug delivery to the intraocular tissues is being developed.66 One example is cross-linked polymer nanosuspensions of dexamethasone, which show enhanced anti-inflammatory activity in a model of rabbit eye irritation.67 Chitosan nanoparticles increase bioavailability of 5-fluorouracil to the aqueous humor in rabbits.68 In other model systems, solid lipid nanoparticles containing methazolamide yield prolonged therapeutic efficacy in reducing intraocular pressure in glaucoma compared to commercial eye drop preparations.69 Magnetic hyperthermia was used with superparamagnetic Mn0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 nanoparticles to induce heat shock proteins throughout the vitreous body as a neuroprotective strategy for glaucoma.70 Delivery of macromolecules and plasmid DNA to the nuclei of retinal and corneal cells can be achieved using PEGylated nucleolin-binding peptide nanoparticles.71

G. Imaging and Diagnostics

A range of nanoscale systems has been developed for bioimaging. These include liposomes, quantum dots, magnetic nanoparticles, and dendrimers.72 These nanoparticulate imaging systems are amenable to bioimaging by single-photon emission computed tomography, positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fluorescence microscopy, computed tomography, and ultrasound.

Use of superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles for MRI imaging to distinguish between normal and cancerous liver tissue was successfully developed.73 SPIO particles are used, for example, for imaging prostate cancer metastases and atherosclerotic plaques.74,75 Other nanoformulations in development for cancer detection include ferritin nanocages, dendrimers, liposomes, nanoshells, nanotubes, emulsions, and quantum dots.76–78 By actively targeting these nanoparticles to specific cell surface receptors, the sensitivity and accuracy of imaging are improved in animal models of human disease.18,79,80 Perfluorocarbon nanoparticle carriers were developed for targeting ligands for aVb3-integrin to visualize aortic neovasculature during the development of atherosclerotic plaques in rabbits.81 Nanoparticle systems also offer the possibility of multiple imaging modalities. For example, quantum dots in combination with SPIO particles have been used in animals to provide for both optical imaging and MRI.82 To determine drug delivery to a target site, dendrimers can provide targeted delivery of both drug and optical dyes.24

III. Chemical Composition, Structure, Function, and Manufacture

As described above, a range of other nanoparticular systems, which include functionalized fullerenes and carbon nanotubes, liposomes, iron oxide nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, dendrimers, nanoshells, polymeric nanospheres, nanobins, quantum dots, and polymer-coated nanocrystals, among others, are being applied to improve human disease outcomes72,81,83,84 These systems are discussed in relation to their potential for use in cancer and infectious disease diagnosis and treatment.

A. Functionalized Fullerenes and Carbon Nanotubes

Fullerenes and carbon nanotubes have been well studied since their discovery in 1985. However, their use in nanomedicine has been limited by their lack of water solubility. Functionalization of fullerenes and carbon nanotubes has increased their water solubility and attractiveness for use in biomedical applications as vehicles for nanodrug delivery.83 To functionalize fullerenes and carbon nanotubes for drug delivery and ROS quenching and for use as MRI contrast agents, functional moieties were developed which include dendrimers, amino acids, peptides, proteins, liposomes, polyamines, polymers, carboxyl groups, and gadolinium.76,83,85–88 Because of their ability to release substantial vibrational energy upon exposure to near-infrared radiation (NIR), multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) were studied for photothermal cancer ablation.89 MWCNTs coated with Pluronic F127 when administered to mice bearing RENCA tumors localized to the tumor sites. Treatment of the tumors with an NIR laser resulted in a 10-fold reduction in tumor size and increased survival rate in mice treated with 100-μg MWCNT compared to saline-treated mice. The authors proposed this treatment as a potential method for reducing the amount of NIR radiation needed for ablation of embedded cancers and limiting damage to surrounding dermal tissue.

B. Liposomes

Liposomes are vesicles composed of a lipid bilayer surrounding a hollow core into which drugs or other molecules can be loaded for delivery to tumors or other disease sites.88,90,91 They can be composed of natural phospholipids or other surfactants. Hydrophilic molecules can be carried in the aqueous interior of the liposome, while hydrophobic molecules can be dissolved in the lipid membrane.92 Thus, liposomes can carry both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs and molecules to a target site. Delivery of the drug is accomplished when the liposome fuses with the lipid membrane of a cell, releasing its contents into the cell cytoplasm. Liposomes can be coated with a functionalized polymer, creating a nanobin, to improve targeted drug delivery.93 Long-circulating liposomes (or “stealth liposomes”) can be obtained by coating with polyethylenglycol chains (PEGylated liposomes).94 The most important application of liposomal delivery is AmBisome®, an injectable liposomal formulation of amphotericin B that consists of the drug dissolved in the lipid bilayer of unilamellar liposomes composed of soy phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, and distearoyl phosphatidylglycerol. In clinical trials, AmBisome® showed equal or improved efficacy and fewer side effects than amphotericin B in the treatment of febrile neutropenia, cryptococcal meningitis, and histoplasmosis.95

C. Polymeric Micelles

When amphiphiles are placed in water, they form micelles with their hydrophobic tails forming a core surrounded by a hydrophilic shell.96 Polymeric micelles are made with amphiphilic polymers such as the block copolymers poly(ethyleneglycol)-b-poly(e-caprolactone)(PEG-b-PCL),22 poly(styrene) or PLGA.96 FDA-approved block copolymers of poly(ethylene) oxide-polypropylene oxide are the most commonly used for targeted drug delivery.86 Hydrophobic drugs can be suspended in the core and protected from the surrounding environment by the hydrophilic shell. The hydrophilic shell serves to disperse the micelles in an aqueous environment and imparts the unique pharmaceutical behavior of the drug-micellar suspension. Polymeric micelles have been extensively studied as injectables to deliver poorly water-soluble drugs such as paclitaxel and amphotericin B.97–99 Adding ligands to the ends of the polymer chains can target the micelles to specific cell types, such as T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells.86 Potential use of polymeric micelles composed of Pluronic block copolymers containing dextran for oral delivery of drugs, such as cyclosporine A, has also been described.96

D. Polymeric Nanospheres

Polymeric nanospheres are uniform spherical structures less than a micron in size made from nonbiodegradable or biodegradable polymers. The aqueous polymer is dispersed in an organic phase and then cross-linked to form spherical structures.100 Drug molecules can be entrapped in the interior of a hollow nano-sphere or incorporated into the matrix of a solid nanosphere. Nanospheres made from tyrosine-derived triblock copolymers are able to deliver lipophilic therapeutics101–103 and, when incorporated into gels, are effective agents for transdermal drug delivery.104 Their use as targeted imaging agents was described recently by Li et al.105 The fluorescence activity of the polymers poly[9,9-bis(2-(2-(2-methox-yethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl) fluorenyldivinylene] (PFV) and the PFV derivative (PFVBT) containing 10 mol% 2,1,3-benzothiadiazole (BT) when conjugated and functionalized with the peptide arginine–glycine–aspartic acid was utilized to diagnose human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive and integrin-positive cancer cells in vitro.

E. Dendrimers

Dendrimers are large, complex molecules with a well-defined branched chemical structure. They are monodisperse, highly symmetric, highly branched, and generally spherical.24 Their composition comprises a series of branched chains around a central core, with surface functional groups on the exterior. Void spaces between the chains allow carriage of drugs or molecules for imaging.106 The most utilized dendrimers are clusters made of poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) units107 and are assembled in layers, or generations. Functionalization of the dendrimers can be accomplished by linking a targeting moiety to the surface structure. By attaching sugar moieties, such as mannose, to the surface of polypropyleneimine dendrimers, the antituberculosis drug rifampicin was delivered directly to macrophages and its hemolytic side effects were reduced.108

F. Polymer-Coated Nanocrystals

Coating of crystalline hydrophobic molecules with polymers and surfactants has been accomplished by wet-milling and high-pressure homogenization processes.34,36,109–111 The polymeric coating of the nanocrystals prevents aggregation and helps in establishing a stable nanosupension. Stability of the nanoformulations is dependent on both the drug and surfactant composition. Polymer-coated nanocrystals of antiretroviral drugs such as indinavir, atazanavir, ritonavir, and efavirenz are being developed by our laboratory for macrophage-based delivery to sites of HIV infection and sequestration.34–36,109,112 Crystalline drug coated with polymer was readily taken up by macrophages in culture and was effective in reducing HIV infection of the cells. Further, macrophages loaded with nanoformulated indinavir were able to deliver an effective antiviral dose to an area of HIV infection in a mouse model of HIV encephalitis.

G. Nanoshells

Nanoshells are spherical particles consisting of a dielectric core surrounded by a thin metallic shell, most commonly gold.113,114 Because of their optical and chemical properties, these particles have been used for biomedical imaging and cancer treatment. PEG coating of the gold shell minimized nonspecific uptake by macrophages and improved in vivo bioavailability.115 Other functional groups can be added, such as receptor antibodies, to target the nanoshells to specific cells.115 Photothermal ablation can then eliminate those cells containing the particles.116 Nanoshells have also been designed that carry antitumor drugs such as doxorubicin and combretastatin to allow concerted action of the two drugs at tumor sites.117

H. SPIO Nanoparticles

Iron oxide particles in the range of 1–100 nm possess superparamagnetic properties that make them attractive for biomedical imaging, diagnosis, and therapeutics in addition to their long-standing use in separation technologies.118,119 SPIO particles consist of a core of magnetite or maghemite with a coating of polysaccharides, polymers, or monomers. Functional groups can be attached to the surface coating to achieve targeted delivery of the particles for imaging specific cell and tissue sites.120–123 Beduneau et al. covalently linked IgG and Fab′2 fragments to SPIO particles to facilitate uptake by macrophages in vitro. Intravenous administration of the IgG-linked SPIO to mice demonstrated sustained distribution to lymphoid tissue over 24 h.124

I. Quantum Dots

Quantum dots are semiconductors with spatially confined excitons that afford them unique optical and electrical properties.125 Their distinct fluorescence spectra make them valuable tools for biomedical imaging. Gao et al.126 demonstrated the utility of quantum dots for simultaneous visualization of several target sites by injecting quantum dots with differing emission wavelengths into three different subcutaneous sites in a mouse. Using a single excitation wavelength, a different color emission for each injection site was observed. Bioactive targeting molecules can be conjugated to the surface of the quantum dots to image specific cells and structures, such as tumor cells, cell membrane receptors, and cellular organelles.122,127–129 Because of the stability of their fluorescence emission, quantum dots are increasingly being studied to label intracellular compartments. Quantum dots were used to label endosomal compartments,130,131 F-actin filaments,132,133 mortalin, and P-glycoprotein.134,135 The use of quantum dots for imaging in human disease, however, is limited by their potential heavy metal toxicity.7,136 Methods to reduce their toxicity include PEGylation and encapsulation by micelles.113

IV. Targeted Drug Delivery

A major focus of nanomedicine research has been to target nanoparticle drug delivery to specific sites. Targeted delivery could simultaneously increase the efficacy of the therapeutic treatment and decrease unwanted side effects.72 One hurdle in the use of nanoparticulate drug delivery has been the uptake of nanoparticles by the cells of the reticuloendothelial system (RES). To minimize removal of nanoparticles by the cells of the RES, coating the particles with PEG is beneficial.14,72 While this may prevent nonspecific uptake by phagocytic cells, more direct targeting strategies are used to focus the nanoparticles to a specific site of cellular action. This is being accomplished by the addition of targeting ligands to the surface of nanoparticles, enabling their recognition by specific receptors on the surface of cancer cells or other target cells.72,137 Ligand-functionalized nanocarriers allow large quantities of drug to be delivered to a cell upon interaction of the ligand with its receptor. By attaching the ligand to the nanocarrier rather than to the drug, the therapeutic activity of the drug is maintained. Targeted nanoparticle delivery also can provide a more efficient delivery into tumor sites. Specifically, targeting of drug nanoparticles to folate receptors overexpressed on cancer cells, human growth factor receptors, and integrins involved in angiogenesis and atherosclerosis have been moved from in vitro testing to in vivo testing.76,138–142

The addition of functional groups on nanoparticles can also serve to target the particle to specific intracellular regions in order to enhance drug function and reduce drug toxicity. Thus, by changing the surface charge of cerium nanoparticles, they could be localized to the cytoplasm or the lysosomes of cancer cells with a corresponding change in cytotoxicity.143 Attachment of a nucleolin-binding peptide to PEGylated nanoparticles effectively delivered a green fluorescent protein to the nucleus of retinal and corneal cells.71

V. Nanomedicine and Vaccines

Nanoparticles are used as adjuvants for vaccines, especially peptide and DNA vaccines.144 Because of their ability to release their entrapped cargo over extended time frames, they have shown potential as vaccine delivery vehicles. Coatings on the surface of nanoparticles or specific polymer composition can increase uptake across mucosal layers and provide oral and intranasal delivery of vaccines.145–147 A recent study reported the successful intranasal delivery of an antitumor vaccine using amphiphilic poly(g-glutamic acid) nanoparticles.148 Biodegradable PLGA particles can elicit a Th1 humoral response144,149 and downregulate Th2 responses in a mouse model of Type 1 allergy.144,150 Lipid A liposomes are used as adjuvants for malarial vaccines.151 Liposomal vaccines can simultaneously activate the major histocompatibility complex class I and II pathways and induce antibody and cellular immune responses.151 Specific targeting of nanoparticulate vaccines to dendritic cells is being explored as a way to enhance the immunogenicity of respiratory virus vaccines.152 SPIO nanoparticles can facilitate delivery of a malaria DNA vaccine into eukaryotic cells.153 Application of an external magnetic field served to enhance transfection efficiency.

Nonbiodegradable nanoparticles (latex, gold, silica, polystyrene) are also used as adjuvants. These particles remain at the site of injection for extended time periods, with potential for enhanced immunogenicity.144 For example, gold nanoparticles were used in Phase I studies for the delivery of hepatitis B and malaria DNA vaccines.154

VI. Nanodevices and Cell Reprogramming

Cell-based therapies using adult, embryonic, or pluripotent stem cells as drug carriers are under development.155,156 To induce cell differentiation for cancer therapeutics and tissue regeneration, adjuvant drugs and growth factors are coadministered.155–158 The growth factors, in particular, need to be maintained at high systemic levels for clinical benefit.157,158 Targeted induction of stem cell growth and differentiation for specific tissue engineering is possible by using scaffolds for drug and growth factor delivery.159–163 Human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were induced to differentiate by embedding them in PLGA nanosphere-encapsulated PLGA microspheres containing different types of growth factors and transplanting the microspheres into nude mice.164 This system can deliver MSCs to any desired tissue site and facilitate their differentiation.

Genetic engineering of donor cells to produce their own support can be accomplished by nonviral vector loading of growth factors by nanoparticle delivery.165 As proof of concept, PAMAM dendrimers functionalized with peptides that exhibit high affinity for MSCs were used for gene transfection of enhanced green fluorescent protein with no cytotoxicity.165 Nanoparticles containing adjuvant drugs conjugated to the surface of hematopoietic stem cells resulted in increased in vivo repopulation and used lower doses of adjuvant than with systemic administration.166 In a different vein, Zhou et al. used synthetic low-density lipoprotein nanoparticles for targeted delivery of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib to chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) stem cells as a potential treatment for eradication of previously resistant CML cells.167

Loading stem cells with magnetic nanoparticles has provided a means to track the migration of cells to sites of disease.168,169 In addition, they can be used as magnetic nanoparticle-based vector systems for transfection of therapeutic biomolecules into stem cells while simultaneously allowing the in vivo migration of the cells to be tracked.168,169 The carriage of the magnetic nanoparticles did not alter the viability and differentiation potential of Schwann, olfactory ensheathing, oligodendrocyte progenitor, and human neural stem cells (NSCs).170–172

VII. Nanomedicine and Stem Cells

Stem cells have been proposed as drug delivery vehicles for chemotherapeutic agents and gene therapy. NSCs have been studied for delivery of neurotrophic factors to the CNS.173–175 In response to disease and injury in cases of AD, PD, cancer, stroke, and multiple sclerosis, NSCs readily migrate to sites of tissue damage. Thus they could be used to deliver neurotrophic factors to diseased and damaged areas in the CNS to promote neuron integrity and regeneration.11 MSCs offer advantages for delivery of therapeutic agents in regenerative medicine and cancer treatment. They are relatively easy to isolate, can differentiate into a wide variety of functional cell types, can be expanded extensively in culture, are not immunogenic, possess immunosuppressant and anti-inflammatory properties upon transplantation, and can migrate to damaged tissues, tumors, and areas of metastases. MSCs have been engineered using nanoparticle delivery vectors to produce antitumor proteins such as TRAIL and were shown to successfully deliver the protein to an intracranial glioma in a mouse xenograft model.176–181 In other tumor models, MSCs modified to produce interferon beta were introduced with a resultant reduction in tumor growth.177,180,181 The potential of using MSCs as vehicles for the delivery of drug-loaded nanoparticles was shown using polylactic acid nanoparticles and lipid nanocapsules loaded with coumarin-6. Marrow-isolated adult multilineage inducible cells loaded with these nanoparticles retained their migratory and differentiation capabilities and migrated to the tumor site in a mouse model of glioma where they were detectable for at least 7 days.182 Using another delivery strategy, NeutrAvidin-coated nanoparticles were attached to MSCs containing a biotinylated plasma membrane and remained attached to the surface for up to 2 days.183 These nanoparticulate cellular patches may provide a novel means of delivering nanotherapeutics to tumors using stem cells.

VIII. Potential of Nanotherapeutics

Nanoparticles can improve pharmacokinetics and biodistribution profiles that lead to increased efficacy and reduced undesirable side effects.21 This may be achieved through increased intestinal uptake, reduced liver metabolism, increased drug half-life, active targeting to a site of disease, or improved accessibility to sites of disease. The utility of nanoparticles in improving pharmacokinetics, reducing unwanted side effects, and improving delivery to disease sites has been demonstrated for a number of nanodrug delivery systems.21

A. Improved Pharmacokinetics

Reformulation of drugs into nanoformulations has been done to increase plasma half-life and enhance the oral bioavailability of several drugs, including those used to treat infectious diseases. As an example, amphotericin B, a poorly water-soluble drug, is used to treat fungal infections and leishmaniasis. Its oral absorption, however, is poor because of its insolubility, instability at acidic pH, molecular size, and P-glycoprotein export activity in intestinal epithelial cells. Several investigators have described the development of nanoparticlute forms of the drug that have increased oral bioavailability and decreased toxicity in animal models.30,184

B. Reduced Toxicity

Nanoformulations of drugs can serve to decrease toxic side effects that limit their therapeutic efficacy. In particular, reduction in toxic side effects is an important driver for the clinical use of nanoformulations of anticancer drugs and antifungal drugs. As an example, the anticancer drug doxorubicin can elicit undesirable side effects, which include cardiotoxicity and myelosuppression.185 Cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin is reduced with use of the nanoformulated version Doxil®.19 The liposomal formulation of amphotericin B, AmBisome®, exhibits not only improved efficacy but also decreased toxicity compared to unformulated drug.186

C. Targeted Tissue Delivery

The development of targeted drug delivery systems that elicit fewer toxic side effects and improved pharmacokinetics is an area of intense focus. Much of the focus on development of targeted nanoparticles has been for delivery of antineoplastic drugs; however, targeted delivery for other diseases is also being explored. Several studies have described the development of targeted nanoparticle delivery of vaccines to dendritic cells.41,59,187–189

To reduce uptake of nanoparticles by the cells of the RES, “stealth” carriers have been developed. These carrier systems contain PEG polymers on their outer surface. PEGylated nanoparticles are not easily recognized by the phagocytic cells of the RES system and thus can avoid accumulation in the RES organs such as the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes and deliver their cargo to the intended site of action more efficiently.14

As an extension of targeted therapy, the use of cells to carry nanoparticles across biologic barriers such as the BBB has been proposed. MSCs loaded with coumarin-6-polylactic acid nanoparticles and coumarin-6-LNCs migrate to a mouse tumor site and there release the nanoparticles and differentiate.182 Similarly, several nanoparticle systems are being developed to take advantage of the phagocytic capability of macrophages and their ability to cross biological barriers such as the BBB. As an example, macrophages have been shown to carry “nanozymes” to sites of injury in an animal model of PD.12 In addition, macrophages loaded with nanoparticles containing antiretroviral drugs have been shown to migrate to the site of HIV infection in the CNS in an animal model of HIV encephalitis and to reduce the rate of viral infection.112 By targeting macrophages for drug uptake in vivo, delivery of drugs to areas of disease or viral infection that are protected from the action of free drug in circulation can be achieved.

D. Subcellular Localization

How nanoparticles are taken up by cells and their intracellular trafficking is determined in large part by their physicochemical properties. Studies using polystyrene beads demonstrated different uptake processes for fluorescent beads of 78 nm and carboxylated spheres of 50 nm. Uptake of the larger fluorescent beads was by a passive, nonphagocytic mechanism,190 while the smaller carboxylated spheres were opsonized and recognized by scavenger receptors on macrophages.191 In other studies, opsonization of particles decreased cellular uptake,192 suggesting that the physicochemical properties of the nanoparticles and cell-specific characteristics influence how nanoparticles are taken up by cells. Endocytosis is a major process by which nanoparticles are taken up by cells and has been demonstrated to occur for gold nanoparticles, iron oxide particles, quantum dots, and carbon nanotubes.130,131,193–195 Once the particles are internalized, intracellular trafficking is dependent on the physicochemical properties of the particles, such as surface charge, polymer coat, and surface modifications.85 Konan and coworkers observed that meso-tetra-(4-hydroxyphenyl)porphyrin (p-THPP)-PLGA nanoparticles were accumulated intracellularly 1.3-fold better than p-THPP-poly (D,L-lactide) (PLA) nanoparticles,196 suggesting that the presence of glycolic acid, imparting a hydrophilic character to the nanoparticle, enhanced cellular sequestration. Cerium nanoparticles were taken up by a clathrin-dependent mechanism and trafficked throughout the cell, supporting the use of these nanoparticles as intracellular scavengers of reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen species.197 Most nanoparticles taken up by endocytosis through either clathrin- or caveolae-dependent mechanisms remain in the endosomes; however, use of specific targeting ligands on the surface of gold nanoparticles was successful in bypassing endosomal uptake and targeting the nanoparticles to specific cellular compartments such as the nucleus.8 By varying alkyl spacer lengths at the termini of dendrimers, Huang et al. could direct the targeting of the dendrimers to either the nucleus or cytosol,198 suggesting that nanoparticle delivery could be targeted to specific intracellular compartments in addition to specific cell types. In additional studies, Bale et al.199 used hydrophobic silica nanoparticles to deliver active proteins intracellularly to a variety of cell types without extended entrapment in the endocytic compartment, which maintained the protein’s biologic activity.

IX. Nanotoxicology: Immunogenicity, Cytotoxicity, and Generation of ROS

Nanotoxicology was coined as a term in 2004–2005137,200,201 although concerns about the adverse affects of nanomaterials on human and environmental health were voiced several years earlier.202 The field came about to study the adverse effects of engineered nanomaterials on living organisms and the ecosystems, with the goal to prevent and eliminate the adverse responses and evaluate the risk/benefit ratio of using nanoparticles in medical settings. Much about the interaction of small particles with biological systems is gleaned from studies of ultrafine particles; however, the uniqueness of the physico-chemical properties of nanoparticles may result in unpredictable biological interactions. The small size of nanoparticles puts them in the range of viruses, DNA, and proteins and thus their subcellular interactions can reflect the interactions of these molecules. Gold nanocluster compounds 1.4 nm in size were observed to induce cell death by intercalation into the major groove of DNA, while larger gold nanoparticles were nontoxic.203 The subcellular localization of quantum dots appears to depend on size, as quantum dots in the range of 2.1 nm localized to the nucleus while larger quantum dots (3.4 nm) remained in the cytoplasm.204,205 Single-walled carbon nanotubes have been shown to interfere with the microtubular system of cells and thus interfere with cell division.206,207 The shape of nanoparticles in combination with their small size may play a role in how they are perceived by cells. Cationic PEG nanoparticles that are rod-shaped are better internalized than particles of other shapes, suggesting that their resemblance to rod-shaped bacteria may enhance their recognition by cells of the immune system.208 The toxicity of nanoparticles is not only dependent on their size and shape, but is also correlated with the relative surface area of administered nanoparticles. Clearance of titanium dioxide nanoparticles administered by inhalation to rats was proportional to the surface area of the particles rather than to the mass of the particles.209 Also, Monteiller and coworkers found that the proinflammatory activity of low-solubility, low-toxicity nanoparticles was proportional to surface area rather than mass.210 Another component of nanoparticles that can contribute to the overall biologic response is the actual surface coating of the particles. Endotoxin adherence to nanoparticle surfaces,211 surfactant composition of the nanoparticles,212 and transition-metal contamination during synthesis213 can induce adverse effects of administered nanoparticles. Furthermore, aggregation of the nanoparticles can mean that the toxic response to the nanoparticles is dependent on the size of aggregates rather than size of nanoparticles.214

Cell-based delivery can positively affect the biodistribution of the nano-particles and their efficacy and toxicity profiles.137 The immunogenicity of certain types of nanoparticles is being taken advantage of in the development of adjuvants for vaccines.215 In contrast, potential deleterious effects of nano-particles on phagocytic cells can interfere with innate and adaptive immune responses. Nanoparticles such as fullerenes and quantum dots have been observed to induce autophagy in phagocytic cells and could lead to insufficient innate and adaptive immune responses.216–218

Nanoparticles have been proposed as inducers of oxidative stress.219–224 Two potential mechanisms for eliciting excessive cellular oxidative stress have been presented, ROS generation by metal contaminants in nanoparticles, and nanoparticles as sources of oxidizing equivalents. Metals are used during the manufacture of carbon nanotubes and are present as contaminants in the final product. Metal ions such as Fe2+ can participate in the one-electron oxidation of oxygen to produce ROS such as superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals.225 In animals treated with carbon nanotubes, oxidation of cellular proteins, DNA, and lipids has been observed226,227 and could be exacerbated by maintaining animals on a vitamin E deficient diet.228 Suh and colleagues84 proposed several events in which nanoparticles could produce cell toxicity and ROS both outside and inside the cell. (1) Nanoparticles smaller than a cell produce ROS externally and destabilize the cell membrane. (2) Internalized nanoparticles create ROS internally. (3) Particle dissolution after internalization results in ROS production. (4) Mechanical damage of organelles such as lysozomes, endoplasmic reticulum, and the nucleus results in increased ROS production. (5) Different functional groups and surface chemistry on different types of nanoparticles can affect the interaction between the nano-particles and their surroundings. (6) The size of the nanoparticle can determine the toxic event, with larger particles damaging the cell membrane and smaller internalized particles affecting cells intracellularly. (7) Nanoparticle shape may determine cell surface effects and internalization. (8) Dissolution products of the nanoparticles externally can affect their interaction with the cell. These interactions are very complex, and applying systems biology to understand them has been proposed.84

X. Unique Challenges for Translational Nanomedicine

While the potential for therapeutic benefits from nanomedicines is great, the translation of basic research into clinically used drugs can be complicated.217 Specifically, how should the safety and efficacy of nanomaterials be defined? Regulatory guidelines currently in existence are generally suitable for nanomedicines; however, there can be confusion over guidelines related to animal study design, therapeutic efficacy and potency, dosimetrics across species, and drug delivery to the target site.217 Many of the studies needed to develop nanoparticle formulations for drug delivery are similar to those for small molecules.229,230 However, in some instances, the nanoparticles may interfere with common tests, and other means of evaluation of suitability will have to be considered. For example, dendrimers exhibit a high false-positive rate in a common endotoxin test.229,230 Thus some tests designed for small molecules may not be suitable for evaluating nanoparticulates, and alternatives will need to be developed.

A. Assessing Efficacy

Different nanomaterials have different physicochemical properties that can impact their activity in biologic systems. The size of the nanoparticles can affect biodistribution and potential toxicity.229,230 For example, smaller gold nanoparticles (10 nm) exhibit a wider biodistribution profile than larger (50 and 250 nm) particles following intravenous injection,231,232 with the smaller particles being detected in liver, spleen, kidney, testis, thymus, heart, lung, and brain and the larger particles being present in only spleen and liver. Others have shown that smaller polypropylene nanoparticles stabilized with Pluronic (poloxamer 188) could enter the lymphatic system more readily than larger particles following intradermal injection.233 Pharmacokinetics and distribution can also be influenced by aggregation of the particles and their association with endogenous proteins.229,230 The pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of dendrimers is also greatly influenced by parameters such as molecular weight and polymer chain length, with smaller sizes exhibiting more rapid renal clearance than larger sizes.234

For each nanoformulation, characteristics such as surface charge, shape, stability, particle density, and solubility, in addition to the unique properties of a particular type of formulation, may differ and may influence the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and efficacy of the nanoparticles. The oil/water partitioning coefficient affects the biodistribution of drugs in an emulsion, while size, charge, surface properties, and lipid type affect the biodistribution of liposomal formulations.87,229 If specific mechanisms are required to release the active drug from its carrier, the bioavailability and biodistribution of the drug will be affected by the activity of the release mechanisms.229,230

The choice of animal species for preclinical testing is critical. Animal models of human disease are used to predict human efficacy of potential therapeutics and can be used for preclinical testing of nanoparticle drug delivery and efficacy. For certain degenerative and infectious diseases, appropriate animal models may be available, for example, the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) mouse model for PD12,235 and humanized mouse models for HIV infection and neurological disorders.236,237 Testing of nanoformulations of enzymes and antiretroviral drugs in these animal systems will provide evidence for estimating clinical efficacy in the human diseases.

B. Unique Toxicological Issues

Because of the unique properties of nanomaterials, unexpected, adverse responses may arise that would not be predicted from what is known about the compounds on a larger scale.238 In addition, the use of standard toxicological screening assays may not be appropriate for all nanoparticulate systems. A number of articles have reviewed the need for specific in vitro assays to test specific nanoparticle systems for determining oxidative stress and ROS production, proinflammatory activity, and genotoxicity.223,239,240 Traditional and proteomics-based assays can be used to assess target cell function in response to nanoparticle treatment.223,241–243 Nanoparticulate drug systems are generally composed of both carrier and drug. Thus, the pharmacokinetics and toxicological properties of both the carrier and drug need to be assessed.229,230,244 Further, nanoparticles tend to accumulate in cells of the phagocytic lineage,244 and thus may cause unwanted side effects in tissues with high numbers of monocytes and macrophages (liver, spleen, bone marrow, lymphatics).

XI. Development of Cell-Based Nanomedicine: A Perspective

A. Cell-Specific Targeting

As a means of targeting drug delivery, efforts to develop cell-based carriers for nanomedicines are underway. Use of immunocytes, MP (monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells), lymphocytes, neutrophils, and stem cells has been proposed. The ability to target drugs to specific sites of disease, prolong drug half-life by sequestering drug away from hepatic metabolism, release drug slowly, and decrease drug toxicity are all advantages provided by cell-based drug carriage. In addition, immunocytes and stem cells can migrate to sites of injury and tumors and act as Trojan horses to deliver drug across biological barriers such as the BBB. Despite their potential, there are limitations that need to be overcome for cell-based nanomedicine delivery to be a viable clinical treatment paradigm. Drug loading into the cells can be low, thus sufficient numbers of cells must migrate to the site of release in order to deliver a therapeutically effective drug dose. Once inside the cells, the drug must be released from the carrier into the extracellular space to be effective. A slow, steady release of drug from the carrier cell is required rather than a quick, bolus release. The ability of the cells to migrate and function should not be compromised by the presence of the nanomaterial and drug.

B. Particle Uptake

Nanocarriers for drugs are commonly composed of an outer polymer shell and inner core for drug carriage. The outer core imparts stability to the nanosuspension, determines particle circulation time, and defines the interaction of the nanoparticle with the surrounding environment and cell surfaces. Charged carriers are generally taken up rapidly by mononuclear phagocytes, immunocytes, and stem cells through interaction with plasma membrane receptors.245–251 These receptors include mannose receptor, complement and Fc receptors that recognize mannans and integrins, and complement and antibody opsonized particles. Positively charged particles are taken up by macrophages somewhat better than negatively charged particles,36,167 perhaps through interaction with the negatively charged plasma membrane. To improve cell loading of nanocarriers with neutral and hydrophobic shells, such as PEG, attachment of targeting vectors has proven to be beneficial.245,252–254

C. Subcellular Localization, Drug Stability, and Drug Release

Once inside cell carriers, the stability, retention, and controlled release of the drug can depend on the intracellular trafficking of the nanocarrier. By avoiding entry of drug-loaded nanocarriers into lysosomes, disintegration of the drug is reduced.9,110 Nanoparticles of ritonavir prepared by high-pressure homogenization and coated with poloxamer 188, N-(carbonyl-methoxypolyethyleneglycol 2000)-1,2 sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (mPEG-DSPE), and (1-oleoyl-2-[6-[(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino]hexanoyl]-3-trimethylammonium propane were taken up by human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) via a clathrin-mediated mechanism. They were trafficked to recycling endosomes where they remained intact and were released through Rab 11- and Rab14-dependent mechanisms. The nanoparticles that were released retained their ability to prevent HIV-1 infection of MDM cultures. It is noteworthy that these particles were positively charged, and that divergent fates for positively and negatively charged particles inside macrophages have been described.254 In another example, positively charged block copolymers (PEI-PEG and polylysine (PL)-PEG) provided protection for “nanozymes” from lysosomal degradation following uptake by MDM, whereas a negatively charged block copolymer (poly-L-glutamic acid (PGLU)-PEG) did not.167

The release of uploaded nanoencapsulated drugs from the carrier cells at the target site is also an area of active study. A controlled release of the drug from the cell carrier is desired in order to provide a sustained dose and duration of exposure at the diseased site. Cell residence time and extracellular conditions at the site of disease can provide release of the drug from the cell carrier. Macrophages are well known to release compounds from intracellular vesicles in response to disease stimuli, and this mechanism could be applied to release of nanocarriers of drugs.13 Other stimuli for nanocarrier release could include an increase in intracellular Ca++255 and mild hyperthermia in the case of anticancer treatment.256

The structure and composition of the nanocarrier itself will also affect the intracellular stability and toxicity and cellular release of the drug nanoparticle. Nanozymes containing catalase were taken up and released best by macrophages when the negatively charged block copolymer PGLU-PEG was used and the nanozymes were not cytotoxic; however, the enzyme was readily degraded in the lysosomal compartment of the cells.167 When a positively charged block copolymer was used, cytotoxicity of the nanozymes was increased and cell loading and release were lower; however, enzymatic activity of the enzyme was retained.

D. Cells as Trojan Horses for Drug Delivery

For cells to be effective carriers of nanomedicines, they have to effectively target to the site of disease. For CNS disorders, they also need to be able to penetrate the BBB to elicit their therapeutic effect. Peripheral diseases, and, in particular, many neurological disorders, have an inflammatory component that can actively recruit macrophages. Through the processes of diapedesis, chemotaxis, margination, and extravasation, macrophages can cross the BBB. These cells, loaded with drug nanoparticles, can then deliver the drug to the site of disease in the CNS. In an experimental mouse model of neuroAIDS, mouse bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) loaded with indinavir nanoparticles and injected intravenously into SCID mice migrated to a site of induced HIV encephalitis in the brain and reduced the rate of infection compared to untreated animals.112 Indinavir levels at the site of infection were elevated compared to levels in noninfected brain tissue 14 days after administration of indinavir nanoparticle-loaded BMMs. As another example, significant amounts of catalase (2.1% of the injected dose) were detected in the brain after injection of catalase nanozyme-loaded mouse BMM into mice treated with MPTP, an experimental model of PD.13 Macrophages loaded with nanoparticles were also observed to migrate to areas of myocardial infarction, spinal cord injury, cerebral ischemia, and cancer.257–262 Other cell types such as NSCs also have the potential to migrate to areas of disease in the CNS and thus could serve as potential drug nanoparticle delivery vehicles.173–175

While these methods require preloading of the cells with drug nanoparticles and then administration to the diseased host, an alternative approach is being explored for delivery of antiretroviral drug nanoparticles. Polymeric nanoparticles of the antiretroviral drugs indinavir, ritonavir, atazanavir, and efavirenz have been made by wet-milling and high-pressure homogenization.34–36 These particles are rapidly taken up by MP in culture and are retained by the cells for up to 15 days. Antiretroviral efficacy in HIV-infected MP is observed through 15 days postinfection. Preliminary in vivo studies in mice demonstrated atazanavir levels in serum exceeding 100 ng/ml and in liver and spleen exceeding 500 ng/g up to 14 days after subcutaneous administration of poloxamer 188-coated atazanavir nanocrystals (unpublished observations). This proof of concept suggests that, when administered by parenteral injection, polymer-coated antiretroviral nanoparticles can be taken up by macrophages and delivered to reservoir sites of viral infection including the CNS.

E. Future Perspectives

Cell delivery of drug nanoparticles has been demonstrated for animal models of disease. However, these methods have not yet been tested in a clinical setting. For clinical use, cell carriers could be harvested from the patient’s blood by apharesis, loaded with drug, and then readministered to the patient. Stem cells could be harvested from bone marrow, propagated, loaded with drug, and then adoptively transferred to the patient. In another setting, drug nanoparticles that were targeted for selective uptake by macrophages could be administered to patients. The patient’s own phagocytic cells would take up the administered nanoparticles and deliver them to sites of injury and disease. By targeting the drug nanoparticles to specific cell carriers, drug uptake and delivery could be greatly improved.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Carol Swarts MD Neuroscience Research Laboratory Fund, the Frances and Louie Blumkin Foundation, the Community Neuroscience Pride Research Initiative, the Alan Baer Charitable Trust, and the National Institutes of Health Grants P20 DA026146, R01 NS36126, P01 NS31492, 2R01 NS034239, P20 RR15635, P01 MH64570, and P01 NS43985 (to HEG) and 1RO1 NS057748 (to EVB).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ernst JD. Bacterial inhibition of phagocytosis. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:379–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberger CM, Finlay BB. Phagocyte sabotage: disruption of macrophage signalling by bacterial pathogens. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:385–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin JS, Abraham SN. Co-option of endocytic functions of cellular caveolae by pathogens. Immunology. 2001;102:2–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skendros P, Pappas G, Boura P. Cell-mediated immunity in human brucellosis. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:134–42. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breunig M, Bauer S, Goepferich A. Polymers and nanoparticles: intelligent tools for intracellular targeting? Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;68:112–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen K, Conti PS. Target-specific delivery of peptide-based probes for PET imaging. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1005–22. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hild WA, Breunig M, Goepferich A. Quantum dots—nano-sized probes for the exploration of cellular and intracellular targeting. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;68:153–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nativo P, Prior IA, Brust M. Uptake and intracellular fate of surface-modified gold nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2008;2:1639–44. doi: 10.1021/nn800330a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadiu I, Nowacek A, McMillan J, Gendelman HE. Macrophage endocytic trafficking of antiretroviral nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2011;6:975–94. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Y, Haney MJ, Klyachko NL, Li S, Booth SL, Higginbotham SM, et al. Polyelectrolyte complex optimization for macrophage delivery of redox enzyme nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2011;6:25–42. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batrakova EV, Gendelman HE, Kabanov AV. Cell-mediated drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8:415–33. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.559457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brynskikh AM, Zhao Y, Mosley RL, Li S, Boska MD, Klyachko NL, et al. Macrophage delivery of therapeutic nanozymes in a murine model of Parkinson’s disease. Nanomedicine. 2010;5:379–96. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batrakova EV, Li S, Reynolds AD, Mosley RL, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV, et al. A macrophage-nanozyme delivery system for Parkinson’s disease. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:1498–506. doi: 10.1021/bc700184b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner V, Dullaart A, Bock AK, Zweck A. The emerging nanomedicine landscape. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1211–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1006-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gradishar WJ. Albumin-bound paclitaxel: a next-generation taxane. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:1041–53. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.8.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cattel L, Ceruti M, Dosio F. From conventional to stealth liposomes: a new Frontier in cancer chemotherapy. J Chemother. 2004;16(Suppl 4):94–7. doi: 10.1179/joc.2004.16.Supplement-1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald A. Improving tolerability of immunosuppressive regimens. Transplantation. 2001;72:S105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendelsohn J. A national cancer clinical trials system for targeted therapies. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75cm78. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science. 2004;303:1818–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1095833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emerich DF, Thanos CG. The pinpoint promise of nanoparticle-based drug delivery and molecular diagnosis. Biomol Eng. 2006;23:171–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igarashi E. Factors affecting toxicity and efficacy of polymeric nanomedicines. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;229:121–34. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanez JA, Forrest ML, Ohgami Y, Kwon GS, Davies NM. Pharmacometrics and delivery of novel nanoformulated PEG-b-poly(epsilon-caprolactone) micelles of rapamycin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:133–44. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0458-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misra R, Acharya S, Sahoo SK. Cancer nanotechnology: application of nanotechnology in cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:842–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sampathkumar SG, Yarema KJ. Targeting cancer cells with dendrimers. Chem Biol. 2005;12:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seigneuric R, Markey L, Nuyten DS, Dubernet C, Evelo CT, Finot E, et al. From nanotech-nology to nanomedicine: applications to cancer research. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:640–52. doi: 10.2174/156652410792630634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bothun GD, Lelis A, Chen Y, Scully K, Stoner MA. Multicomponent folate-targeted magnetoliposomes: design, characterization, and cellular uptake. Nanomedicine. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.02.007. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deshayes S, Maurizot V, Clochard MC, Baudin C, Berthelot T, Esnouf S, et al. “Click” conjugation of peptide on the surface of polymeric nanoparticles for targeting tumor angiogenesis. Pharm Res. 2011;28:1631–42. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taratula O, Garbuzenko O, Savla R, Wang YA, He H, Minko T. Multifunctional nanomedicine platform for cancer specific delivery of siRNA by superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles-dendrimer complexes. Curr Drug Deliv. 2011;8:59–69. doi: 10.2174/156720111793663642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffiths G, Nystrom B, Sable SB, Khuller GK. Nanobead-based interventions for the treatment and prevention of tuberculosis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:827–34. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Italia JL, Yahya MM, Singh D, Ravi Kumar MN. Biodegradable nanoparticles improve oral bioavailability of amphotericin B and show reduced nephrotoxicity compared to intravenous Fungizone. Pharm Res. 2009;26:1324–31. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9841-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SS, Peer D, Kumar P, Subramanya S, Wu H, Asthana D, et al. RNAi-mediated CCR5 silencing by LFA-1-targeted nanoparticles prevents HIV infection in BLT mice. Mol Ther. 2010;18:370–6. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manandhar KD, Yadav TP, Prajapati VK, Kumar S, Rai M, Dube A, et al. Antileishmanial activity of nano-amphotericin B deoxycholate. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:376–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mihu MR, Sandkovsky U, Han G, Friedman JM, Nosanchuk JD, Martinez LR. The use of nitric oxide releasing nanoparticles as a treatment against Acinetobacter baumannii in wound infections. Virulence. 2010;1:62–7. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.2.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nowacek AS, Balkundi S, McMillan J, Roy U, Martinez-Skinner A, Mosley RL, et al. Analyses of nanoformulated antiretroviral drug charge, size, shape and content for uptake, drug release and antiviral activities in human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Control Release. 2010;150:204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowacek AS, McMillan J, Miller R, Anderson A, Rabinow B, Gendelman HE. Nanoformulated antiretroviral drug combinations extend drug release and antiretroviral responses in HIV-1-infected macrophages: implications for neuroAIDS therapeutics. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010;5:592–601. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nowacek AS, Miller RL, McMillan J, Kanmogne G, Kanmogne M, Mosley RL, et al. NanoART synthesis, characterization, uptake, release and toxicology for human monocyte-macrophage drug delivery. Nanomedicine. 2009;4:903–17. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosa Borges A, Wieczorek L, Johnson B, Benesi AJ, Brown BK, Kensinger RD, et al. Multivalent dendrimeric compounds containing carbohydrates expressed on immune cells inhibit infection by primary isolates of HIV-1. Virology. 2010;408:80–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sosnik A, Carcaboso AM, Glisoni RJ, Moretton MA, Chiappetta DA. New old challenges in tuberculosis: potentially effective nanotechnologies in drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:547–59. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Xu K, Liu L, Tan JP, Chen Y, Li Y, et al. The efficacy of self-assembled cationic antimicrobial peptide nanoparticles against Cryptococcus neoformans for the treatment of meningitis. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2874–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Feng SS, Wang S, Chen ZY. Evaluation of cationic nanoparticles of biodegradable copolymers as siRNA delivery system for hepatitis B treatment. Int J Pharm. 2010;400:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiang SD, Selomulya C, Ho J, Apostolopoulos V, Plebanski M. Delivery of DNA vaccines: an overview on the use of biodegradable polymeric and magnetic nanoparticles. Wiley Inter-discip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2010;2:205–18. doi: 10.1002/wnan.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barnes T, Moots R. Targeting nanomedicines in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: focus on certolizumab pegol. Int J Nanomedicine. 2007;2:3–7. doi: 10.2147/nano.2007.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koo OM, Rubinstein I, Onyuksel H. Actively targeted low-dose camptothecin as a safe, long-acting, disease-modifying nanomedicine for rheumatoid arthritis. Pharm Res. 2010;28:776–87. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0330-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu XM, Miller SC, Wang D. Beyond oncology–application of HPMA copolymers in non-cancerous diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:258–71. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yudoh K, Karasawa R, Masuko K, Kato T. Water-soluble fullerene (C60) inhibits the development of arthritis in the rat model of arthritis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2009;4:217–25. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s7653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cui Z, Lockman PR, Atwood CS, Hsu CH, Gupte A, Allen DD, et al. Novel D-penicillamine carrying nanoparticles for metal chelation therapy in Alzheimer’s and other CNS diseases. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2005;59:263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu G, Men P, Kudo W, Perry G, Smith MA. Nanoparticle-chelator conjugates as inhibitors of amyloid-beta aggregation and neurotoxicity: a novel therapeutic approach for Alzheimer disease. Neurosci Lett. 2009;455:187–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu G, Men P, Perry G, Smith MA. Nanoparticle and iron chelators as a potential novel Alzheimer therapy. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;610:123–44. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-029-8_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cabaleiro-Lago C, Quinlan-Pluck F, Lynch I, Lindman S, Minogue AM, Thulin E, et al. Inhibition of amyloid beta protein fibrillation by polymeric nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15437–43. doi: 10.1021/ja8041806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao L, Zhao D, Chan WH, Choi MM, Li HW. Inhibition of beta 1–40 amyloid fibrillation with N-acetyl-L-cysteine capped quantum dots. Biomaterials. 2010;31:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Esposito E, Fantin M, Marti M, Drechsler M, Paccamiccio L, Mariani P, et al. Solid lipid nanoparticles as delivery systems for bromocriptine. Pharm Res. 2008;25:1521–30. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9514-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hsu SH, Wen CJ, Al-Suwayeh SA, Chang HW, Yen TC, Fang JY. Physicochemical characterization and in vivo bioluminescence imaging of nanostructured lipid carriers for targeting the brain: apomorphine as a model drug. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:405101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/40/405101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang R, Ke W, Liu Y, Jiang C, Pei Y. The use of lactoferrin as a ligand for targeting the polyamidoamine-based gene delivery system to the brain. Biomaterials. 2008;29:238–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu S, Chen M, Yao Y, Zhang Z, Jin T, Huang Y, et al. Novel poly(ethylene imine) biscarbamate conjugate as an efficient and nontoxic gene delivery system. J Control Release. 2008;130:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warrington JS, Shaw LM. Pharmacogenetic differences and drug-drug interactions in immunosuppressive therapy. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2005;1:487–503. doi: 10.1517/17425255.1.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bisht S, Feldmann G, Koorstra JB, Mullendore M, Alvarez H, Karikari C, et al. In vivo characterization of a polymeric nanoparticle platform with potential oral drug delivery capabilities. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3878–88. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu K, Cao G, Zhang X, Liu R, Zou W, Wu S. Pretreatment with intraluminal rapamycin nanoparticle perfusion inhibits neointimal hyperplasia in a rabbit vein graft model. Int J Nanomedicine. 2010;5:853–60. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S13112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clawson C, Huang CT, Futalan D, Martin Seible D, Saenz R, Larsson M, et al. Delivery of a peptide via poly(D, L-lactic-co-glycolic) acid nanoparticles enhances its dendritic cell-stimulatory capacity. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:651–61. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klippstein R, Pozo D. Nanotechnology-based manipulation of dendritic cells for enhanced immunotherapy strategies. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:523–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wigglesworth KM, Racki WJ, Mishra R, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Greiner DL, Galili U. Rapid recruitment and activation of macrophages by anti-Gal/{alpha}-Gal Liposome interaction accelerates wound healing. J Immunol. 2011;186:4422–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwan KH, Liu X, To MK, Yeung KW, Ho CM, Wong KK. Modulation of collagen alignment by silver nanoparticles results in better mechanical properties in wound healing. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cai L, Guinn AS, Wang S. Exposed hydroxyapatite particles on the surface of photo-cross-linked nanocomposites for promoting MC3T3 cell proliferation and differentiation. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2185–99. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kon E, Delcogliano M, Filardo G, Busacca M, Di Martino A, Marcacci M. Novel nano-composite multilayered biomaterial for osteochondral regeneration: a pilot clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1180–90. doi: 10.1177/0363546510392711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lei Y, Rahim M, Ng Q, Segura T. Hyaluronic acid and fibrin hydrogels with concentrated DNA/PEI polyplexes for local gene delivery. J Control Release. 2011;153:255–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olakowska E, Woszczycka-Korczynska I, Jedrzejowska-Szypulka H, Lewin-Kowalik J. Application of nanotubes and nanofibres in nerve repair A review. Folia Neuropathol. 2010;48:231–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Das S, Suresh PK. Nanosuspension: a new vehicle for the improvement of the delivery of drugs to the ocular surface. Application to amphotericin B. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:242–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rafie F, Javadzadeh Y, Javadzadeh AR, Ghavidel LA, Jafari B, Moogooee M, et al. In vivo evaluation of novel nanoparticles containing dexamethasone for ocular drug delivery on rabbit eye. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35:1081–9. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.508867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagarwal RC, Singh PN, Kant S, Maiti P, Pandit JK. Chitosan nanoparticles of 5-fluorouracil for ophthalmic delivery: characterization, in-vitro and in-vivo study. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2011;59:272–8. doi: 10.1248/cpb.59.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li R, Jiang S, Liu D, Bi X, Wang F, Zhang Q, et al. A potential new therapeutic system for glaucoma: solid lipid nanoparticles containing methazolamide. J Microencapsul. 2011;28:134–41. doi: 10.3109/02652048.2010.539304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jeun M, Jeoung JW, Moon S, Kim YJ, Lee S, Paek SH, et al. Engineered superparamagnetic Mn0.5Zn0. 5Fe2O4 nanoparticles as a heat shock protein induction agent for ocular neuro-protection in glaucoma. Biomaterials. 2011;32:387–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]