Abstract

Background. Recent studies suggested that two common polymorphisms, miR-146a G>C and miR-196a2 C>T, may be associated with individual susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, the results remain conflicting rather than conclusive. Object. The aim of this study was to assess the association between miR-146a G>C and miR-196a2 C>T polymorphisms and the risk of HCC. Methods. A meta-analysis of 17 studies (10938 cases and 11967 controls) was performed. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used to evaluate the strength of the association. Results. For miR-146a G>C, the variant genotypes were associated with a decreased risk of HCC (CC versus GG: OR = 0.780 and 95% CI 0.700–0.869; GC/CC versus GG: OR = 0.865 and 95% CI 0.787–0.952; CC versus GC/GG: OR = 0.835 and 95% CI 0.774–0.901). For miR-196a2 C>T, significant association was also observed (TT versus CC: OR = 0.783, 95% CI: 0.649–0.943, and P = 0.010; CT versus CC: OR = 0.831, 95% CI 0.714–0.967, and P = 0.017; CT/TT versus CC: OR = 0.817, 95% CI 0.703–0.949, and P = 0.008). Conclusion. The two common polymorphisms miR-146a G>C and miR-196a2 C>T were associated with decreased HCC susceptibility, especially in Asian population.

1. Introduction

Liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the world, with 782,000 new cases diagnosed in 2012. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is its dominant histological type and accounts for 70–85% of primary liver cancer [1]. Because of the high fatality rates, its incidence approximately equals the mortality rate and nearly 53% of all liver cancer deaths worldwide were in China [2, 3]. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are the major cause of HCC, but only a fraction of infected patients develop HCC during their lifetime [4, 5]. Recent studies have demonstrated that genetic alterations may be involved in the development and prognosis of HCC [6, 7].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a large family of short noncoding and evolutionarily conserved RNAs (about 21–23 nucleotides) that function as negative gene regulators [8]. They exert their regulatory effects by binding to the 3′ untranslated region of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) imperfectly, repressing target gene expression at a posttranscriptional level and inducing mRNA degradation eventually. These small molecules have been shown to play an important role in malignancy by targeting various tumor suppressors and oncogenes, taking part in cancer stem cell biology, angiogenesis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition [9–12]. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is the most common genetic variation. SNPs in miRNA may affect the expression and function of mature miRNA and thereby influence individual susceptibility to cancer [13–15]. SNPs miR-146a G>C (rs2910164) and miR-196a2 C>T (rs11614913) are two of the most popular miRNA polymorphisms and have been shown to relate to tumorigenesis in several studies [16–20].

To date, several studies have investigated the association between the two polymorphisms miR-146a G>C and miR-196a2 C>T and hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility. However, the results remain inconsistent rather than conclusive. In order to estimate the overall risk of miR-146a G>C and miR-196a2 C>T polymorphisms associated with hepatocellular carcinoma and to quantify the potential between study heterogeneity, we carried out a meta-analysis on all eligible case-control studies with a total of 10938 hepatocellular carcinoma cases and 11967 controls.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Eligibility of Relevant Studies

We searched the electronic literature from PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, ScienceDirect, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases, and Wanfang databases for all relevant reports (the last search update was February 10, 2014), using the search terms “miR-196a2 or microrna 196a2 or rs11614913 or miR-146a or microrna 146a or rs2910164,” “polymorphism or variant or SNP,” and “hepatocellular carcinoma or liver cancer or HCC.” Publication country and publication language were not restricted in our search. In addition, studies were identified by a manual search of the reference lists of original studies. Of the studies with the same or overlapping data published by the same investigators, the most recent or complete articles with the largest sample sizes were included. In our meta-analysis, studies had to meet the following criteria: (a) evaluated the correlation between SNPs miR-146a rs2910164 and/or miR-196a2 rs11614913 and susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma, (b) contained available genotype frequency for both cases and controls, and (c) used a case-control design. Studies were mainly excluded for the following reasons: (a) no control population, (b) duplicating the previous publication, and (c) not for human cancer research.

2.2. Data Extraction

Two of the authors (Zhaoming Wang and Lei Zhang) extracted data independently complying with the inclusion criteria after the concealment of titles, authors, journals, supporting organizations, and funds to avoid investigators' bias. In the present study, the following variables were collected for each study: the first author's last name, year of publication, country of origin, ethnicity, source of controls (population- or hospital-based controls), genotyping method, and sample sizes of genotyped cases and controls. In the cases of conflicting evaluation, the two investigators checked the data and agreement was reached after a discussion. If disagreement still existed, senior investigator Jianmin Bian was invited to the discussion.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

For the control group of each study, the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was calculated using a goodness-of-fit chi-square test. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to assess the strength of association between the miR-146a rs2910164 and miR-196a2 rs11614913 polymorphism and susceptibility to HCC. The pooled ORs were performed for allele frequency comparison (miR-146a G>C: C versus G, and miR-196a2 C>T: T versus C), codominant model (miR-146a G>C: GC versus GG, CC versus GG, miR-196a2 C>T: CT versus CC, and TT versus CC), dominant model (miR-146a G>C: GC/CC versus GG, and miR-196a2 C>T: CT/TT versus CC), and recessive model (miR-146a G>C: CC versus GC/GG, and miR-196a2 C>T: TT versus CT/CC), respectively. The significance of pooled ORs was determined by Z-test and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The heterogeneity between the studies was assessed by Cochran's Q-test [21]. If the studies were shown to be homogeneous with a P > 0.10 for the Q test, the summary of OR estimate of each study was calculated using a fixed-effects model (the Mantel-Haenszel method) [22]. Otherwise, the random-effects model (the DerSimonian and Laird method) was used [23]. Sensitivity analyses were also performed to assess the stability of the results by deleting a single study in the meta-analysis each time to reflect the influence of the individual data set to the summary OR. To test the publication bias, both Funnel plots and Egger's linear regression tests were used [24]. All analyses were performed with Stata software (version 10.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), using two-sided P values.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies

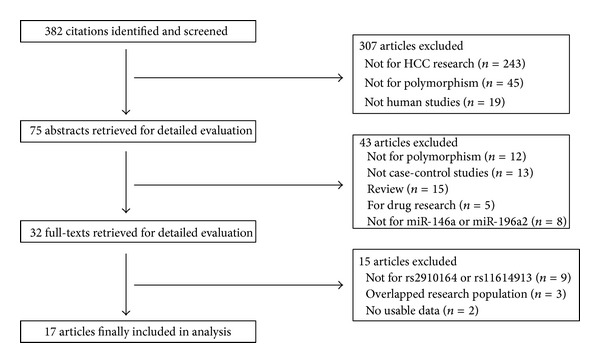

There were 382 published articles relevant to the search terms (Figure 1). By choosing additional filters, 307 of these papers were excluded (243 not for hepatocellular carcinoma research, 45 not for polymorphism, and 19 not for human studies). 43 of these studies were excluded by screening the titles and abstracts. Only 32 articles were left for full text review, and among them another 15 were excluded. Finally, a total of 17 eligible studies involving 5689 cases and 6790 controls for miR-146a G>C and 10 studies involving 5249 cases and 5177 controls for miR-196a2 C>T were included in this meta-analysis [25–41]. The characteristics of the selected studies are summarized in Table 1. For miR-146a G>C, there were 12 studies on Asian population (11 Chinese and 1 Korean) and 1 study on Caucasian population (Turkish). As for miR-196a2 C>T, 9 studies were carried out on Asians (8 Chinese and 1 Korean) and one study on Caucasian (Turkish). Hepatocellular carcinomas were confirmed histologically or pathologically in most studies. All of the controls were matched with respect to ethnicity. Among them, 16 studies were population based while one was hospital based. Several genotyping methods were used in the studies, including polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP), primer introduced restriction analysis-PCR (PIRA-PCR), PCR-ligase detection reaction (PCR-LDR), allele specific-PCR (AS-PCR), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF), and MassArray. The distribution of genotypes in the controls was in agreement with HWE in all studies.

Figure 1.

Articles identified with criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of literatures included in the meta-analysis on hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Source of controls | Genotyping method | Cases/controls | MicroRNA polymorphism | Allele frequency G/C or C/T |

HWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xu et al. [36] | 2008 | China | Asian | Population | PCR-RFLP | 479/504 | miR-146a G>C | 0.36/0.64 | 0.119 |

| Xu [37] | 2010 | China | Asian | Population | PCR-RFLP | 500/522 | miR-146a G>C | 0.39/0.61 | 0.296 |

| 492/495 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.46/0.54 | 0.621 | ||||||

| Qi et al. [33] | 2010 | China | Asian | Population | PCR-LDR | 361/391 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.49/0.51 | 0.869 |

| Li et al. [31] | 2010 | China | Asian | Hospital | PCR-RFLP | 310/222 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.42/0.58 | 0.402 |

| Wang [34] | 2011 | China | Asian | Population | MALDI-TOF | 1116/1869 | miR-146a G>C | 0.39/0.61 | 0.115 |

| Akkiz et al. [25] | 2011 | Turkey | Caucasian | Population | PCR-RFLP | 222/222 | miR-146a G>C | 0.80/0.20 | 0.384 |

| Akkiz et al. [26] | 2011 | Turkey | Caucasian | Population | PCR-RFLP | 185/185 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.55/0.45 | 0.492 |

| Zhang et al. [39] | 2011 | China | Asian | Population | PIRA-PCR | 925/840 | miR-146a G>C | 0.41/0.59 | 0.149 |

| 934/837 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.47/0.53 | 0.972 | ||||||

| Yu [38] | 2012 | China | Asian | Population | PCR-RFLP | 100/100 | miR-146a G>C | 0.44/0.56 | 0.506 |

| Li [32] | 2012 | China | Asian | Population | AS-PCR | 560/560 | miR-146a G>C | 0.42/0.58 | 0.196 |

| 560/560 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.39/0.61 | 0.056 | ||||||

| Kim et al. [30] | 2012 | Korea | Asian | Population | PCR-RFLP | 159/201 | miR-146a G>C | 0.38/0.62 | 0.190 |

| 159/201 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.49/0.51 | 0.356 | ||||||

| Xiang et al. [35] | 2012 | China | Asian | Population | PCR-RFLP | 100/100 | miR-146a G>C | 0.44/0.56 | 0.506 |

| Zhou et al. [41] | 2012 | China | Asian | Population | PCR-RFLP | 186/483 | miR-146a G>C | 0.41/0.59 | 0.056 |

| Huang et al. [29] | 2013 | China | Asian | Population | MALDI-TOF | 110/110 | miR-146a G>C | 0.32/0.68 | 0.122 |

| Zhang et al. [40] | 2013 | China | Asian | Population | MassArray | 997/998 | miR-146a G>C | 0.39/0.61 | 0.911 |

| 996/995 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.42/0.58 | 0.245 | ||||||

| Han et al. [27] | 2013 | China | Asian | Population | RT-PCR | 1017/1009 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.46/0.54 | 0.310 |

| Hao et al. [28] | 2013 | China | Asian | Population | PCR-RFLP | 235/281 | miR-146a G>C | 0.38/0.62 | 0.056 |

| 235/281 | miR-196a2 C>T | 0.52/0.48 | 0.051 |

HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; RFLP: restriction fragment length polymorphism; PIRA: primer introduced restriction analysis; LDR: ligase detection reaction; AS: allele specific; MALDI-TOF: matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight.

3.2. Quantitative Synthesis

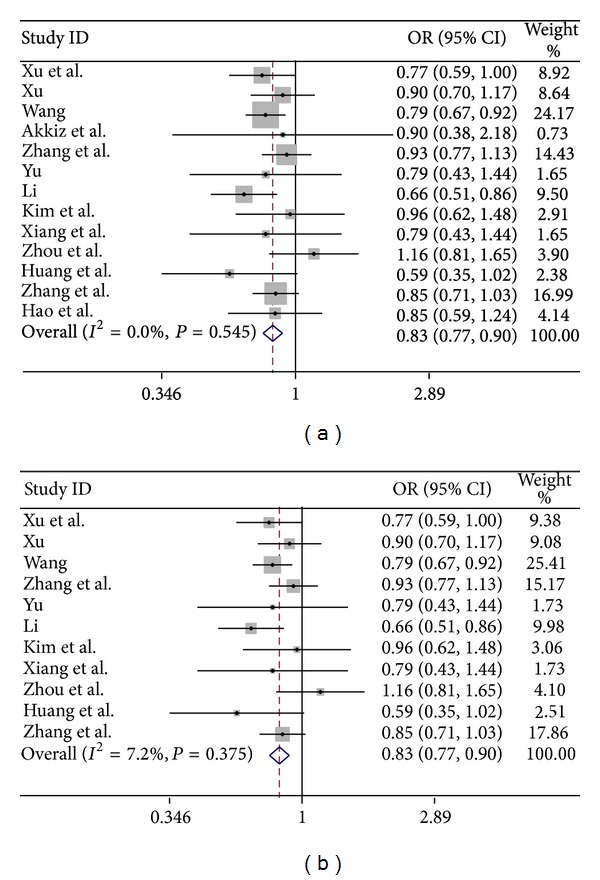

As shown in Table 2, the miR-146a G>C polymorphism was significantly associated with a decreased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in the following models: C versus G: OR = 0.883, 95% CI 0.839–0.930, and P = 0.000; CC versus GG: OR = 0.780, 95% CI 0.700–0.869, and P = 0.000; GC/CC versus GG: OR = 0.865, 95% CI 0.787–0.952, and P = 0.003; CC versus GC/GG: OR = 0.835, 95% CI 0.774–0.901, and P = 0.000 (Figure 2(a)), and this positive association also was maintained in ethnicity subgroup analysis. 11 out of the 12 included studies were conducted in Asian population. Significant association remained in Asian population in the following genetic models: C versus G: OR = 0.878, 95% CI 0.834–0.925, and P = 0.000; CC versus GG: OR = 0.777, 95% CI 0.697–0.867, and P = 0.000; GC/CC versus GG: OR = 0.850 95% CI 0.771–0.937, and P = 0.001; CC versus GC/GG: OR = 0.834, 95% CI: 0.771–0.901, and P = 0.000 (Figure 2(b)).

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of the miR-146a G>C polymorphism associated with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Comparisons | OR | 95% CI | P | P h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | ||||

| C versus G | 0.883 | 0.839–0.930 | 0.000 | 0.230 |

| CC versus GG | 0.780 | 0.700–0.869 | 0.000 | 0.167 |

| GC versus GG | 0.920 | 0.832–1.017 | 0.104 | 0.199 |

| GC/CC versus GG | 0.865 | 0.787–0.952 | 0.003 | 0.125 |

| CC versus GC/GG | 0.835 | 0.774–0.901 | 0.000 | 0.545 |

| Asian | ||||

| C versus G | 0.878 | 0.834–0.925 | 0.000 | 0.255 |

| CC versus GG | 0.777 | 0.697–0.867 | 0.000 | 0.129 |

| GC versus GG | 0.905 | 0.816–1.004 | 0.060 | 0.216 |

| GC/CC versus GG | 0.850 | 0.771–0.9373 | 0.001 | 0.159 |

| CC versus GC/GG | 0.834 | 0.771–0.901 | 0.000 | 0.461 |

P h: P value of Q test for heterogeneity test; OR odds: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of hepatocellular carcinoma risk associated with the mir-146a G>C polymorphism (CC versus GC/GG) in overall population (a) and in Asian population (b).

For miR-196a2 C>T, the results were shown in Table 3. Association between rs11614913 polymorphism and HCC risk was observed in the following models (using the random-effects model): T versus C: OR = 0.891, 95% CI 0.815–0.974, and P = 0.011; TT versus CC: OR = 0.783, 95% CI: 0.649–0.943, and P = 0.010; CT versus CC: OR = 0.831, 95% CI 0.714–0.967, and P = 0.017; CT/TT versus CC: OR = 0.817, 95% CI 0.703–0.949, and P = 0.008. The results suggested that miR-196a2 C allele carrier may be susceptible to HCC. In subgroup analysis, there was also significant association in Asian population (using the random-effects model, T versus C: OR = 0.910, 95% CI 0.837–0.990, and P = 0.029; TT versus CC: OR = 0.817, 95% CI: 0.684–0.976, and P = 0.026; CT versus CC: OR = 0.838, 95% CI 0.712–0.986, and P = 0.033; CT/TT versus CC: OR = 0.833, 95% CI 0.712–0.974, and P = 0.022).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of the miR-196a2 C>T polymorphism associated with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Comparisons | OR | 95% CI | P | P h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | ||||

| T versus C | 0.891 | 0.815–0.974 | 0.011 | 0.012 |

| TT versus CC | 0.783 | 0.649–0.943 | 0.010 | 0.007 |

| CT versus CC | 0.831 | 0.714–0.967 | 0.017 | 0.025 |

| CT/TT versus CC | 0.817 | 0.703–0.949 | 0.008 | 0.012 |

| TT versus TC/CC | 0.907 | 0.807 | 1.020 | 0.094 |

| Asian | ||||

| T versus C | 0.910 | 0.837–0.990 | 0.029 | 0.036 |

| TT versus CC | 0.817 | 0.684–0.976 | 0.026 | 0.021 |

| CT versus CC | 0.838 | 0.712–0.98 | 0.033 | 0.017 |

| CT/TT versus CC | 0.833 | 0.712–0.974 | 0.022 | 0.012 |

| TT versus TC/CC | 0.935 | 0.846–1.032 | 0.181 | 0.270 |

P h: P value of Q test for heterogeneity test; OR odds: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; random-effects model was used when P h≦0.10; otherwise, fix-effects model was used.

3.3. Heterogeneity, Sensitivity Analysis, and Publication Bias

Q-test was used in all of the genetic models to test heterogeneity. For miR-146a G>C, it showed no significant heterogeneity between studies during overall comparisons (Table 2). For miR-196a2 C>T, heterogeneity was observed in all models (Table 3): T versus C: P h = 0.012 and I 2 = 57.7%; TT versus CC: P h = 0.007 and I 2 = 60.6%; CT versus CC: P h = 0.025 and I 2 = 52.7%; TC/TT versus CC: P h = 0.012 and I 2 = 57.6%; TT versus CT/CC: P h = 0.094 and I 2 = 39.6%. Then, we assessed the source of heterogeneity by ethnicity, source of controls, genotyping methods, publication year, and sample size (subjects > 500 in both cases and controls). Using metaregression analysis, none of them could explain the significant heterogeneity (Table 4). In addition subgroup analysis was performed; substantial heterogeneity still existed when stratified by ethnicity (P h = 0.007 and I 2 = 60.6%), source of controls (P h = 0.009 and I 2 = 61.0%), and sample size (P h = 0.023 and I 2 = 68.5%).

Table 4.

Metaregression analysis for heterogeneity in studies on the miR-196a2 C>T polymorphism associated with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Sort | P | τ 2 | I 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 0.119 | 0.0078 | 51.50% |

| Source of controls | 0.287 | 0.0097 | 56.48% |

| Genotyping method | 0.382 | 0.0134 | 61.50% |

| Year | 0.976 | 0.1454 | 62.34% |

| Sample size | 0.397 | 0.1194 | 58.59% |

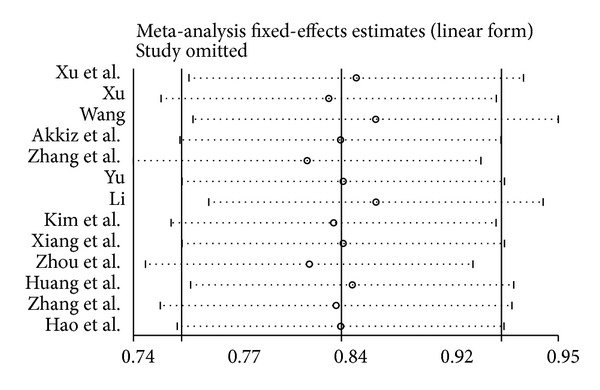

To assess the influence of each individual study on the pooled ORs, the sensitivity analysis was performed by removing a single study from meta-analysis sequentially. The results indicated that no single study influenced the pooled OR qualitatively (Figure 3). It suggested that the results of this meta-analysis were stable.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis for mir-146a G>C polymorphism with hepatocellular carcinoma (CC versus GC/GG).

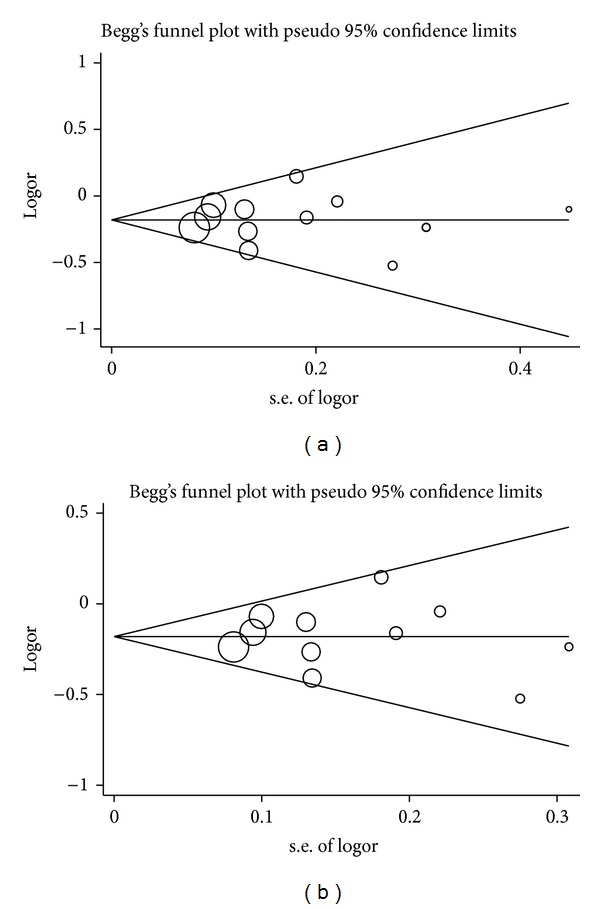

The Begg funnel plot and Egger's test were conducted to assess publication bias. The shapes of the funnel plots did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry in all comparison models (Figure 4). Then, Egger's test was used to provide statistical evidence of funnel plot symmetry. The results still did not show any evidence of publication bias (t = −2.00 and P = 0.074 for miR-146a G>C and t = 1.18 and P = 0.273 for miR-196a2 C>T).

Figure 4.

Begg's funnel plot for publication bias test for mir-146a G>C polymorphism with hepatocellular carcinoma in overall population (a) and in Asian population (b). s.e.: Standard Error; logor: logOR (logarithms of Odds Ratio).

4. Discussion

miRNAs are involved in a variety of biological processes and regulate hundreds of gene targets [12]. The study of miRNAs provides a new view of the pathophysiological mechanism of the etiology and development of HCC. SNPs in miRNA sequence have the potential to function as new diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for high risky population in an early stage [42, 43]. Moreover, the identification of SNPs may lead new sights to personalized therapy and small molecular interventions for liver cancer.

MiR-146a G>C, or rs2910164 polymorphism which locates in the passenger strand of miR-146a, can disturb the secondary structure and maturation of miR-146a [26, 44]. Xu et al. [36] found that target genes of miR-146a, such as tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 and interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1, are key adapter molecules downstream of the Toll-like and cytokine receptors in the signaling pathways that play crucial roles in cell growth and immune recognition. So individuals with GG genotype of miR-146a gene have an increased level of mature miR-146a and are more susceptible to carcinogens that promote HCC. Li [32] found miR-146a may target DNA repairing genes such as XRCC1, BRCA11, and XPC. G>C polymorphism can affect mature miR-146a expression and associate with HCC susceptibility. However, in contrast, Akkiz et al. [26] and Kim et al. [30] demonstrated that the rs2910164 polymorphism had no major role in the susceptibility to HCC and they attribute their discrepancy with other studies to ethnic variation in the population. Besides, Zhou et al. [41] indicated polymorphisms of miR-146a were related to the age of onset and Child-Pugh grade in HCC but lacked association with the risk of HCC. Xiang et al. [35] and Zhang et al. [40] also observed no significant difference in ORs of the miRNA-146a variant among HCC patients.

To explain these conflicting results, our meta-analysis, which was based on eleven studies and involved 5689 cases and 6790 controls, was conducted to derive a more precise estimation of the association. Our results suggested that miR-146a G>C polymorphism was associated with decreased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among the included studies, especially in Asian population. Cochran's Q-test and Egger's test showed no significant heterogeneity or publication bias, which indicated that our results were stable. Since miR-146a regulates hundreds of downstream gene targets, it is biologically plausible that rs2910164 polymorphism may alter the oncogenesis genetic pathway and modulate hepatocellular carcinoma risk.

MiR-196a2 C>T polymorphism is another potential SNP in relevance to HCC. It not only affected the maturation of miR-196a2 but also could enhance the cell response to mutagen challenge [31, 45, 46]. Li et al. [31] and Qi et al. [33] found that C allele carriers have a higher incidence of HCC than T allele carriers, which suggested that the C allele may confer risk to the occurrence of HCC. Studies have indicated that high expression of miR-196a2 could deregulate target genes including homeobox (HOX) gene cluster and annexinA1 (ANXA1) gene and lead to carcinogenesis and malignant transformation of HCC [25, 40, 47]. However, Li [32] and Kim et al. [30] observed no significant difference of the TT, TC, and CC genotypes distribution between HCC patients and controls. Han et al.'s study [27] also showed miR-196a2 polymorphism was not statistically associated with HCC risk, though it may enhance the effects of other SNPs in relevance to HCC.

Our meta-analysis included 9 case-control studies to assess the relationship between MiR-196a2 C>T polymorphism and HCC. The results indicated that T allele carriers had significantly lower HCC susceptibility, especially in Asian population. Identification of heterogeneity is one of the most important goals of meta-analysis and heterogeneity existed in our study. However, through subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis we could not find the source of heterogeneity, which suggested that these included studies may be different in either clinical, methodological, or statistical components and the quantitative synthesis.

There are three similar meta-analyses about the association between the miR-146a G>C polymorphism or the miR-196a2 C>T polymorphism and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, but their studies showed different results from ours. Wang et al. 2012 [48] carried out a meta-analysis to estimate the relevance between these two SNPs and HCC susceptibility and it concluded that neither the rs2910164 nor rs11614913 polymorphism was associated with HCC risk. Their results were in the opposite direction to ours possibly due to the relatively small sample size. Their last search update was on September 10, 2012, and they totally identified 6 studies including 1912 cases and 2149 cases for miR-146a G>C polymorphism and 1790 cases and 1635 controls for miR-196a2 C>T polymorphism. In our study we included a total of 17 studies with 5689 cases and 6790 cases for miR-146a G>C polymorphism and 5249 cases and 5177 controls for miR-196a2 C>T polymorphism. Our sample size was much larger and could lead to the difference. Hu et al. 2013 [49] performed a meta-analysis to assess the contributions of the rs2910164 and rs3746444 polymorphisms to HCC susceptibility. Possibly because of the same reason of Wang's, their study showed no significant association. The meta-analysis of Xu et al. 2013 [50] revealed the miR-146a C variant was associated with a decreased HCC risk and it was consistent with ours. Their study only comprised a total of ten case-control studies involving 3437 cases and 3437 controls. We extracted data from all the published studies and added another 7501 cases and 8530 controls to the analysis, which accounted for 69.9% of the total sample size. Thus our results were more precise and persuasive. With regard to rs11614913, they concluded that the miR196a2 T variant was associated with a decreased risk of HCC. However, heterogeneity existed among studies. Our pooled effects were also statistically significant, but we failed to find the source of heterogeneity by subgroup analysis and metaregression analysis. So we concluded that miR-196a2 C>T polymorphism may contribute to a decreased HCC risk, but the results need to be validated by more qualified studies. In our present meta-analysis, we searched multiple databases and included all eligible studies. It contained the newest data and largest sample size. Compared with previous meta-analyses, we generate more exact and powerful pooled results of the association between SNPs miR-146a G>C and miR-196a2 C>T and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

There are some limitations in this meta-analysis that must be addressed. First, in the subgroup analyses, only one study originated from Caucasian, the size of which was small, and there was no African population. So our study mainly suggested the association between the two SNPs and HCC susceptibility in Asian population and may not be generalized to other ethnicities. Further studies on other ethnicities are necessary to validate the results. Second, lack of original data like HBV infection status, alcohol consumption, age, and gender from the included studies limited our further stratified analysis. HBV is one the most important risk factors to HCC [51], and the interactions among gene-gene and gene-environment may relate to cancer risk. Insufficient information prevented us from performing further evaluation. Third, heterogeneity was detected in overall comparisons of miR-196a2 C>T and we could not find its source. Though miR-196a2 C allele carrier was shown to have a higher risk of HCC in our study, more studies using standardized unbiased methods and well-matched controls are needed to draw a more persuasive conclusion. Last, as the two miRNAs have some other more SNPs than miR-146a G>C and miR-196a2 C>T, this analysis cannot tell the contribution of other polymorphisms to the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis provided evidence that the two common polymorphisms miR-146a G>C and miR-196a2 C>T were associated with decreased HCC susceptibility, especially in Asian population. Additional well-designed, large studies are warranted to validate our findings and further functional studies should be conducted to elucidate its mechanism. More sufficient data such as hepatitis infection status, gene-environment interactions, and multiethnic groups should be considered in future studies to lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the association between miR-146a G>C and miR-196a2 C>T polymorphisms and the risk of HCC.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Meilin Wang (Department of Epidemiology, Nanjing Medical University) for critical comments and scientific editing.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Zhaoming Wang and Lei Zhang contributed equally to this work. Jianmin Bian designed this study.

References

- 1.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJF, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. Journal of Hepatology. 2006;45(4):529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. Ca-A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(7):2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerrieri F, Belloni L, Pediconi N, Levrero M. Molecular mechanisms of HBV-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2013;33(2):147–156. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1345721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Chenc L, Hon Man Chan T, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: transcriptome diversity regulated by RNA editing. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2013;45(8):1843–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagymási K, Tulassay Z. Epidimiology, risk factors and molecular pathogenesis of primary liver cancer. Orvosi Hetilap. 2008;149(12):541–548. doi: 10.1556/OH.2008.28313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong CM, Kai AK, Tsang FH, Ng IO. Regulation of hepatocarcinogenesis by microRNAs. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2013;5:49–60. doi: 10.2741/e595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP, Anderson TA. microRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Developmental Biology. 2007;302(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takebe N, Harris PJ, Warren RQ, Ivy SP. Targeting cancer stem cells by inhibiting Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2011;8(2):97–106. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, Hu G, Zhou J. Repression of versican expression by microRNA-143. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(30):23241–23250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.084673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong YW, Ferland-McCollough D, Jackson TJ, et al. microRNAs in cancer management. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13(6):e249–e258. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slaby O, Bienertova-Vasku J, Svoboda M, Vyzula R. Genetic polymorphisms and microRNAs: new direction in molecular epidemiology of solid cancer. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2012;16(1):8–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartels CL, Tsongalis GJ. Mini-reviews micrornas:novel biomarkers for human cancer. Clinical Chemistry. 2009;55(4):623–631. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Yan H-X, Yang W, et al. The role of microRNA expression pattern in human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Journal of Hepatology. 2009;50(2):358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeon HS, Lee YH, Lee SY, et al. A common polymorphism in pre-microRNA-146a is associated with lung cancer risk in a Korean population. Gene. 2014;534(1):66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chae YS, Kim JG, Lee SJ, et al. A miR-146a polymorphism (rs2910164) predicts risk of and survival from colorectal cancer. Anticancer Research. 2013;33(8):3233–3239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasani SS, Hashemi M, Eskandari-Nasab E, et al. A functional polymorphism in the miR-146a gene is associated with the risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a preliminary report. Tumor Biology. 2014;35(1):219–225. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei J, Zheng L, Liu S, et al. MiR-196a2 rs11614913 T > C polymorphism and risk of esophageal cancer in a Chinese population. Human Immunology. 2013;74(9):1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei WJ, Wang YL, Li DS, et al. Association between the rs2910164 polymorphism in pre-Mir-146a sequence and thyroid carcinogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056638.e56638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handoll HH. Systematic reviews on rehabilitation interventions. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2006;87(6, article 875) doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akkiz H, Bayram S, Bekar A, Akgöllü E, Ülger Y. A functional polymorphism in pre-microRNA-196a-2 contributes to the susceptibility of hepatocellular carcinoma in a Turkish population: a case-control study. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2011;18(7):e399–e407. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akkiz H, Bayram S, Bekar A, Akgöllü E, Üsküdar O, Sandikçi M. No association of pre-microRNA-146a rs2910164 polymorphism and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma development in Turkish population: a case-control study. Gene. 2011;486(1-2):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han Y, Pu R, Han X, et al. Associations of pri-miR-34b/c and pre-miR-196a2 polymorphisms and their multiplicative interactions with hepatitis B virus mutations with hepatocellular carcinoma risk. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058564.e58564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hao YX, Wang JP, Zhao LF. Associations between three common MicroRNA polymorphisms and hepatocellular carcinoma risk in Chinese. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2013;14(11):6601–6604. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.11.6601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Q, Huang T-R, Li J-L, et al. Correlation between microRNA-146a polymorphism and primary liver carcinoma in the Guangxi Zhuang population. Chinese Journal of Cancer Prevention and Treatment. 2013;(02):100–104. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim WH, Min KT, Jeon YJ, et al. Association study of microRNA polymorphisms with hepatocellular carcinoma in Korean population. Gene. 2012;504(1):92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X-D, Li Z-G, Song X-X, Liu C-F. A variant in microRNA-196a2 is associated with susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese patients with cirrhosis. Pathology. 2010;42(7):669–673. doi: 10.3109/00313025.2010.522175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y. MicroRNA Related SNPs and Genetic Susceptibility to Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Zhengzhou University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi P, Dou T-H, Geng L, et al. Association of a variant in MIR 196A2 with susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma in male Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Human Immunology. 2010;71(6):621–626. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W. Association of MiR-146a Single Nucleotide Polymorphism with Susceptibility to Hepatocellular Carcinoma and the Microarray Analysis of Tumor Related MicroRNAs. Fudan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiang Y, Fan S, Cao J, et al. Association of the microRNA-499 variants with susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese population. Molecular Biology Reports. 2012;39(6):7019–7023. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu T, Zhu Y, Wei Q-K, et al. A functional polymorphism in the miR-146a gene is associated with the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(11):2126–2131. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y. Association Study of Polymorphisms in MiRNAs Genes with the Susceptibility of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Nanjing Medical University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu L. Association of the MicroRNA-499Variants with Susceptibilityto Hepatocellular Carcinomain the Southwest-China Population. Chongqing Medical University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X-W, Pan S-D, Feng Y-L, et al. Relationship between genetic polymorphism in microRNAs precursor and genetic predisposition of hepatocellular carcinoma. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;45(3):239–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Wang R, Ma YY, et al. Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in miRNA196a-2 and miRNA146a and susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma in a chinese population. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2013;14(11):6427–6431. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.11.6427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou J, Lv R, Song X, et al. Association between two genetic variants in miRNA and primary liver cancer risk in the Chinese population. DNA and Cell Biology. 2012;31(4):524–530. doi: 10.1089/dna.2011.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giordano S, Columbano A. MicroRNAs: new tools for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma? Hepatology. 2013;57(2):840–847. doi: 10.1002/hep.26095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ngamruengphong S, Patel T. Molecular evolution of genetic susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2984-3. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeng Y, Cullen BR. Sequence requirements for micro RNA processing and function in human cells. RNA. 2003;9(1):112–123. doi: 10.1261/rna.2780503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhan J-F, Chen L-H, Chen Z-X, et al. A functional variant in MicroRNA-196a2 is associated with susceptibility of colorectal cancer in a chinese population. Archives of Medical Research. 2011;42(2):144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pavlakis E, Papaconstantinou I, Gazouli M, et al. MicroRNA gene polymorphisms in pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2013;13(3):273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luthra R, Singh RR, Luthra MG, et al. MicroRNA-196a targets annexin A1: a microRNA-mediated mechanism of annexin A1 downregulation in cancers. Oncogene. 2008;27(52):6667–6678. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z, Cao Y, Jiang C, et al. Lack of association of two common polymorphisms rs2910164 and rs11614913 with susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040039.e40039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu M, Zhao L, Hu S, et al. The association between two common polymorphisms in MicroRNAs and hepatocellular carcinoma risk in Asian population. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057012.e57012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu Y, Li L, Xiang X, et al. Three common functional polymorphisms in microRNA encoding genes in the susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gene. 2013;527(2):584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ayub A, Ashfaq UA, Haque A. HBV induced HCC: major risk factors from genetic to molecular level. BioMed Research International. 2013;2013:14 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/810461.810461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]