Abstract

Coronary artery disease with associated myocardial infarction continues to be a major cause of death and morbidity around the world despite significant advances in therapy. Patients who suffer large myocardial infarctions are at highest risk for progressive heart failure and death, and cell-based therapies offer new hope for these patients. A recently discovered cell source for cardiac repair has emerged as a result of a breakthrough reprogramming somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). The iPSCs can proliferate indefinitely in culture and can differentiate into cardiac lineages including cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and cardiac progenitors. Thus large quantities of desired cell products can be generated without being limited by cellular senescence. The iPSCs can be obtained from patients to allow autologous therapy or, alternatively, banks of HLA diverse iPSCs are possible for allogeneic therapy. Preclinical animal studies using a variety of cell preparations generated from iPSCs have shown evidence of cardiac repair. Methodology for the production of clinical grade products from human iPSCs is in place. Ongoing studies of the safety of various iPSC preparations with regard to the risk of tumor formation, immune rejection, induction of arrhythmias, and formation of stable cardiac grafts are needed as the field advances toward the first in man trials of iPSCs post-MI.

Keywords: human induced pluripotent stem cells, cardiomyogenesis, tissue engineering myocardial infarction, cardioregenerative medicine

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) secondary to coronary artery disease is a leading cause of morbidity and death throughout the world. Although reperfusion therapies have provided dramatic advances in the treatment of acute MI, a substantial fraction of patients are not able to promptly undergo successful reperfusion. In patients suffering large MIs, loss of more than a billion cardiomyocytes (CMs) can occur overwhelming the hearts intrinsic reparative capacity. Without further intervention, the damaged myocardium is replaced by fibrous non-contractile tissue (scar), and the resulting left ventricular dysfunction can initiate a spiral of adverse remodeling progressing to end stage heart failure. Although pharmacological therapies can blunt the adverse remodeling, the prognosis for these patients is poor with increased risk of death and reduced quality of life. Hence there is a great need for new approaches to treat post-MI patients, and over the past decade cell therapy has emerged as an appealing avenue to repair the damaged myocardium.

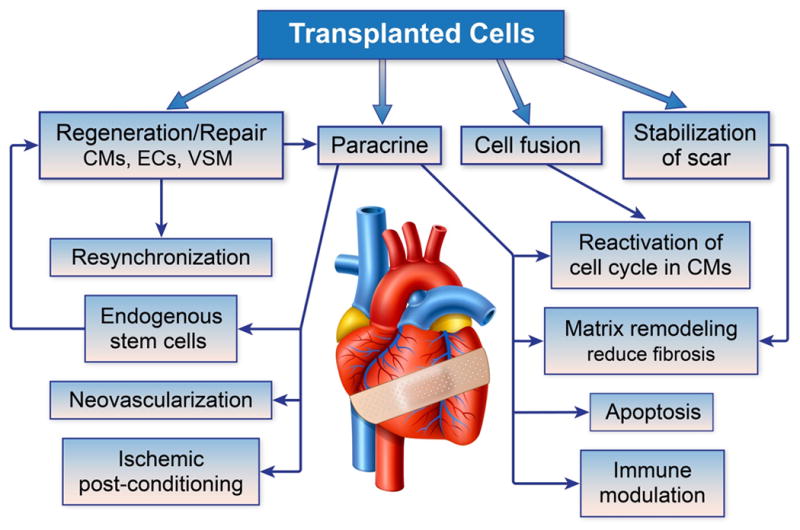

A wide variety of autologous (self) and allogeneic (non-self) cell sources have been tested for post-MI cardiac repair (Table 1). The first cell source studied in detail in both animal models and humans was autologous skeletal myoblasts. Although myoblasts formed stable grafts in the heart, they failed to differentiate into cardiomyocytes and were unable to improve myocardial function.1 Autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells, which posses a broader differentiation potential than myoblasts have also been tested in animal models and clinical trials. A range of rodent post-MI studies provided clear evidence for functional benefit resulting from transplantation of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells to the infarcted myocardium; however, the mechanisms of benefit have been debated. In some studies, robust remuscularization of the infarcted myocardium by c-Kit+/lin- cells isolated from bone marrow was demonstrated,2 but this finding was contested in other studies suggesting that bone marrow mononuclear cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiomyocytes.3, 4 Other mechanisms of benefit have also been proposed including cell fusion, immune-modulation, paracrine effects, and scar stabilization (Figure 1). Despite questions regarding underlying mechanisms, bone marrow mononuclear cells are being broadly tested in early stage clinical trials with results ranging from a small benefit on cardiac functional parameters primarily, e.g. ejection fraction, to no significant effect.5, 6 Patient-specific cardiac stem cells isolated from the adult heart hold promise.7, 8 Experiments in animal models and more recently in early stage clinical trials have shown encouraging results testing autologous cardiac stem cells and cardiosphere-derived cells.9, 10 However, scalability, senescence, and dysfunction secondary to the underlying pathology are major potential limitations for cardiac stem cells.11, 12 Alternatively, the use of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) has been investigated. MSCs can be derived from a variety of tissues including bone marrow and adipose, and these cells can be extensively expanded in culture and exhibit apparent immune privilege. MSCs transplanted post-MI animal hearts have shown benefits which appear to be primarily paracrine in nature.13, 14 MSCs have also been tested in early phase clinical trials including MSCs treated with a cardiogenic cocktail and show signs of functional benefits.15, 16

Table 1. Cell sources investigated for cardiac therapy.

| Autologous | Allogeneic |

|---|---|

| Skeletal myoblasts | Fetal cardiomyocytes |

Bone marrow-derived cells

|

Embryonic stem cells and derivatives |

Endothelial progenitor cells

|

Mesenchymal stem cellsa,b |

Cardiac stem/progenitor cells

|

Parthenogenetic stem cells and derivatives |

| Spermatogonial stem cells and derivatives | |

| Induced pluripotent stem cells and derivativesa |

Can be both autologous and allogeneic

Can be derived from multiple tissues including bone marrow and adipose.

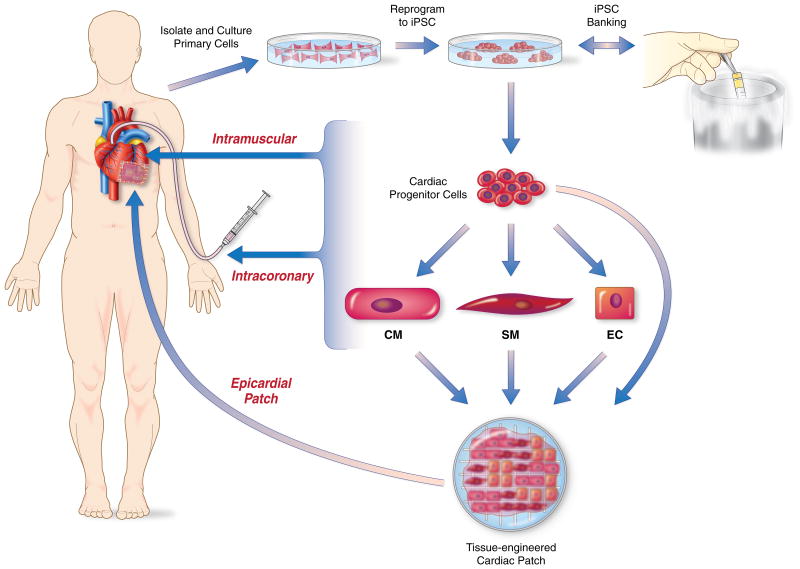

Figure 1. Potential mechanisms of benefit of cell therapy to the post-MI heart.

Transplanted cells exert beneficial effects on the damaged myocardium by multiple potential mechanisms. Regeneration of new myocardium from delivered cells is the most appealing mechanism; however, most pre-clinical and clinical studies to date have suggested that the beneficial effects of post-MI cell therapy are due to paracrine signaling. Paracrine signaling can reduce apoptosis in surviving cells, promote cell cycle activation for repair, prevent adverse immune remodeling, activate endogenous stem cells and induce neo-vascularization. The optimal cell therapy will likely harness multiple of these potential mechanisms for successful cardiac repair.

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) provide another allogeneic cell source investigated for post-MI therapy and tested in animal models. ESCs have undoubted potency to generate all cell types present in the heart, and both human17-19 and mouse20-25 ESCs as well as their derivatives have shown functional benefit in various animal MI models. Nevertheless, concerns about immune rejection, safety and the embryonic source of these cells have delayed clinical applications.26 In addition, other pluripotent stem cell sources including spermatogonial stem cells and parthenogenetic stem cells have been suggested as potential cell sources for cardiac repair,27, 28 but little data exist at this time on these cell sources and particularly with regard to human cells.

The recent discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and other advances in reprogramming technologies such as induced cardiomyocytes (iCMs) have provided more potential avenues for cardiac repair.29-32 Although iCMs and direct in vivo reprogramming post-MI hold promise,33-35 this review will focus on iPSC applications. Because iPSCs are produced by reprogramming somatic cells such as dermal fibroblasts, they can provide autologous cells for patients, reducing the risk of immune rejection. Another promising feature of iPSCs is that they can be extensively expanded for the production of large quantities of potentially any cell type desired to repair the myocardium. Despite this promise, iPSCs are incompletely understood, so there are several questions associated with this cell source including concerns regarding reprogramming effects, immunogenicity and tumorigenesis. Initial studies have begun to examine the utility of iPSCs and their derivatives for cellular therapy to treat a variety of diseases using animal models. The purpose of this review is to describe the progress in using iPSCs and their derivatives for post-MI cardiac repair highlighting recent advances in iPSC-related technology and preclinical animal models as well as discuss the remaining challenges that need to be overcome for successful transition of iPSC-technology to the clinic.

iPSC Technology

In a 2006 landmark study, Yamanaka and colleagues demonstrated that mouse fibroblasts could be reprogrammed by ectopically expressing 4 key pluripotency factors (Oct-3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4) to a state resembling ESCs in morphology and developmental potential and called these cells induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).29 Similar reprogramming was soon accomplished using human fibroblasts by the Yamanaka group and independently by Thomson and colleagues who used a slightly different combination of transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28).32, 36 These major discoveries initiated an avalanche of research advancing reprogramming technology and defining the properties and applications of iPSCs. A brief overview highlighting the advances in iPSC technology will be described, but interested readers are referred to other detailed reviews focused on this topic.37, 38

More cell types were soon demonstrated to be capable of undergoing factor-based reprogramming. In the mouse system, embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and tail tip fibroblasts (TTFs) were first reprogrammed, but soon a variety of cell types from all three germ layers were successfully reprogrammed. Likewise, iPSC research in the human system has expanded from using dermal or fetal fibroblasts to a range of cells sources including T cells,39, 40 fat tissue,41, 42 cord blood,43 amniotic fluid cells44 and even renal tubular cells present in urine.45 Juvenile human keratinocytes were shown to be 100-fold more efficient and two-fold faster at generating iPSCs as compared to other human fibroblasts.46 Also, hematopoietic stem cells were found to be 300 times more efficient at iPSC generation as compared to mature T/B cells.47 These results are in agreement with the mouse system where progenitor cells from various tissues have been more efficiently reprogrammed to iPSCs than terminally differentiated cells like fibroblasts. In general, cell types that are closer to inner cell mass cells/ESCs in the developmental hierarchy will be more efficiently reprogrammed to iPSCs.37

The iPSCs reprogrammed from different sources share many properties including pluripotency and self-renewal; however, differences in epigenetic state, mutational burden and differentiation capacity may ultimately lead to certain preferred cell sources for reprogramming for clinical applications. For example, dermal fibroblasts subjected to UV exposure and other stresses have potentially a greater mutation burden than more protected blood stem and progenitor cell pools. Alternatively, cell types that require less manipulation for reprogramming to pluripotency may be less likely to suffer adverse effects from reprogramming. One such cell type is the skeletal myoblasts (SMs), which endogenously express Klf4, Sox2 and c-Myc and hence induced expression of Oct4 alone can reprogram them to pluripotency.48 Some investigations have also proposed biased differentiation potential of the iPSC line based on the tissue of origin due to epigenetic memory.49 The relative importance of these and other differences between cell sources regarding clinical applications using iPSCs will require further investigation.

The methods to reprogram somatic cells are also rapidly advancing. Retroviral and lentiviral delivery of reprogramming factors were first employed with success. However, limitations with these integrating vectors are well known, including insertional mutagenesis (activating or inactivating an endogenous gene) and persistent expression of the transgene. These effects could impact the functional properties of iPSCs and their progeny, and they are of particular concern for clinical applications given the observed insertional mutagenesis-induced cancers in some early gene therapy trials. Recently, sendai virus-based vectors have been used in iPS reprogramming.50 Sendai viruses, unlike retroviruses do not integrate in host genome and are diluted out of reprogrammed cells over passages. A variety of alternative non-viral/non-integrating approaches have also been utilized including transfecting with simple plasmids,51 episomal vectors,36 and mini-circle based vectors;52 these techniques were inefficient as compared to virus based vectors. PiggyBac transposon-based vectors have also been utilized that have higher reprogramming efficiency and can be excised from the genome after achieving reprogramming.53, 54 Nevertheless, DNA based strategies still carry some risk of insertional mutagenesis and genomic recombination which needs to be considered. Therefore, recombinant proteins were used for reprogramming mouse fibroblasts.55 This method, although not DNA based, was slow and inefficient. Also, generating recombinant proteins in vitro is a major task. A more recent advance is the use of modified mRNA-based TF delivery as an alternative for reprogramming.56 However, nonviral-based reprogramming strategies have in general been less efficient as compared to virus based. A recent study has revealed that activation of innate immune response (as triggered by viral infection) leads to epigenetic changes that favor reprogramming.57 This discovery could potentially be applied to non-integrating approaches to further increase reprogramming efficiency as well as to get safer iPSC for transplant. Finally, epigenetic modifiers like HDAC inhibitors and DNA demethylating agents have been used to increase reprogramming efficiency in conjunction with the above mentioned strategies.58

In conclusion, there has been exponential growth in the technologies to produce iPSCs which has outpaced the ability to thoroughly investigate and benchmark the properties of resulting iPSCs. Nevertheless, iPSCs are already proving useful in drug testing and disease modeling. To date a variety of patient-specific iPSC lines have been generated for hematopoietic, hepatic, neurological as well as cardiovascular diseases demonstrating the utility of iPSC technology for studying disease mechanisms in-vitro. iPSC-derived CMs and neurons along with other cells types are increasingly being used in the pharmaceutical industry for drug discovery and toxicity assays.59, 60 Growing experience with these nonclinical applications of iPSCs has helped lead to the general consensus that non-integrating strategies to produce “footprint-free” iPSCs should be given the highest priority for further characterization and preclinical studies.

Differentiation and purification of cardiac lineage cells from iPSCs

ESCs and iPSCs have an unquestionable cardiac differentiation potential, like the pluripotent cells in the inner cell mass of the blastocyst which undergo a series of sequential differentiation steps including formation of mesodermal cells which further develop to heart field-specific progenitors which ultimately give rise to the heart. This complex process is orchestrated by dynamic growth factor gradients specific for particular stages of development as well as changing extracellular matrix composition as reviewed well by others.61, 62 Multiple cell types differentiate and precisely organize to form the functioning heart including CMs, endothelial cells (ECs), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and fibroblasts. Initial differentiation protocols used aggregates of ESCs, which in the presence of serum can spontaneously differentiate into embryoid bodies (EBs) containing poorly organized derivatives of the three primary germ layers including in some EBs contracting CMs. Alternatively, taking advantage of insights from cardiac development, co-culturing undifferentiated ESCs on a feeder layer of visceral endoderm-like cells was used to induce cardiogenesis.63 However, these initial approaches showed significant variability and were relatively inefficient at generating CMs. More recently, differentiation protocols aimed at generating CMs have evolved to use defined conditions with timed applications of specific growth factors known to be important in cardiac development, e.g. Activin A, BMP4, bFGF, Wnts, and in some cases manipulations of extracellular matrix as reviewed in detail elsewhere.64 The resulting yield and purity of CMs from these protocols has improved dramatically such that it is relatively straightforward to obtain millions and with scale-up billions of CMs at purities of 70% or better. In addition, small molecules have been used to biphasically manipulate Wnt signaling during differentiation to produce high yields and purities of CMs.65 Although much of the research on differentiation protocols was done with human ESCs, these protocols have also been applied to iPSCs successfully. The advances in CM differentiation protocols represent an enabling advance in the technology for producing human heart cells for potential clinical applications.64

Like protocols for generating CMs from ESCs and iPSCs, continually improving protocols for the differentiation to VSMCs and ECs have been evolving. Initial approaches used EBs to generate ECs and VSMCs, but subsequent studies have used feeder cells secreting key signaling molecules or more directed differentiation approaches. In directed differentiation protocols, growth factors to promote differentiation to VSMCs include PDGF-BB and TGF-β1.66, 67 In the case of differentiation to ECs, BMP4 and VEGF-A have been commonly used.66 Vascular progenitor cells have been isolated from cultures based on CD34 expression that can give rise to both ECs and VSMCs.66, 68, 69 For ECs, purification of the cells has been accomplished using anti-CD31 or anti-VWF with sorting to give relatively pure populations of ECs. Differentiation of other clinically relevant lines from iPSCs and ESCs has been described including cardiac progenitors and MSCs.70-73 Thus, ESCs/iPSCs can be differentiated into multiple cell types which are potentially useful for cardiac cell therapy.

Although the progress with differentiation protocols has been striking, a closer examination of the resulting cell populations reveals that significant cellular heterogeneity remains which could adversely impact clinical outcomes. In the case of CM differentiation, even if a protocol generates predominately CMs, there are different types of CMs present which exhibit distinct functional properties including ventricular-like, atrial-like and nodal-like CMs.74 If the purpose of a cell product is to repair the ventricular myocardium, then ventricular-like cells would likely be the desired CM population. In addition, non-CM cells are present typically including VSMCs, ECs, fibroblasts and potentially other undefined cell types. Furthermore, the cells can exhibit variable functional maturity and typically are embryonic in phenotype. Similar concerns exist for other lineage differentiation protocols such as EC preparations which exhibit a mixture of arterial, venous and lymphatic ECs.75 A number of approaches are being advanced to address such heterogeneity such as cell sorting using cell surface markers. In the case of ECs, a number of well-defined cell surface markers are known such as CD31 or vWF, but for CMs, the cell surface markers are only starting to be defined and utilized such as VCAM and SIRPA.71, 76 Genetic selection strategies in which cells are genetically modified with a cell lineage specific promoter driving expression of a fluorescent protein or an antibiotic resistance gene can allow selection of the desired cell type.77, 78 The disadvantage of this approach is that it requires genetic manipulation of the cells which can be time consuming and create adverse consequences such as insertional mutagenesis. Recently, differences in the metabolic properties between CMs and non-CMs have been exploited to devise a metabolic selection strategy which involves substituting lactate for glucose in culture medium to obtain CMs of up to 99% purity.79 Ultimately, refining differentiation protocols will produce improved preparations for therapy. Whether pure cell lineage preparations are ideal or a mixture of cells is best, will require additional investigation.

Animal Studies Using iPSC and iPSC-derivatives for Post-MI Repair

A growing number of studies have tested the ability of iPSCs and differentiated cells derived from iPSCs to repair the post-MI heart (see Table 2). Most of the studies have been in small animal models, but large animal models are also starting to be utilized. The cell preparations being tested have included undifferentiated iPSCs, iPSC-derived cardiac progenitors, CMs, VSMCs, and ECs (see Figure 2). These cell preparations have been tested alone or in combination sometimes using tissue engineering approaches.

Table 2. Preclinical studies of post-MI cell therapy using iPSCs and derivatives.

| Reference | Cell Source for Reprogramming | Reprogramming Method | Cell type transplanted | Delivery method | Animal Model | Duration of Study | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson et al.80 | MEFs | Lentiviral- human (KOSM) | iPSCs | Intramyocardial injection | Mouse | 4 wks | ↑ Ventricular function, ↓ pathological remodeling. Engraftment & differentiation into CMs, SMs,ECs. No teratomas in immunocompetent mice. Teratomas in immunodeficient mice. |

| Singla et al.81 | Mouse H9c2 cardiomyoblasts | Plasmid - mouse (KOSM) | iPSCs | Intramyocardial injection | Mouse | 2 wks | ↑ Ventricular function, ↓ apoptosis. No teratomas in immunocompetent mice. |

| Templin et al.93 | Human cord blood | Lentiviral - human (NOLS) | iPSCs | Intramyocardial injection | Pig | 12-15 wks | iPSCs co-injected with hMSC survived and differentiated into endothelial cells. iPSCs injected alone failed to survive. Pigs were immunosuppressed. |

| Ahmed et al.82 | Mouse SMs | Retrovirus - mouse (KOSM) | iPSCs | Intramyocardial injection | Mouse | 4 wks | Tumorigenic in 40% of immunocompetent mice |

| Zhang et al.83 | Rat Bone Marrow | Lentiviral - human (KOSM) | iPSCs | Intramyocardial injection | Rat | 2-6 wks | Tumorigenic independent of cell dose, duration and presence/absence of MI |

| Pasha et al.48 | Mouse SMs | DNMT-RG108 | Day5 EB-beating aggregate | Intramyocardial injection | Mouse | 4 wks | ↓ Fibrosis, ↑ heart function. No teratomas in immunocompetent mice. |

| Ahmed et al.84 | Mouse SMs | Retrovirus - mouse (KOSM) | Day10 EB-beating aggregates | Intramyocardial injection | Mouse | 4 wks | ↓ infarct size, ↑ cardiac function. No tumorigenesis |

| Buccini et al.85 | Mouse bone marrow MSCs | Retrovirus - mouse (KOSM) | Day10 EB- beating aggregates | Intramyocardial injection | Mouse | 4 wks | ↓ infarct size, ↑ global cardiac function partly due paracrine effects. No tumorigenesis |

| Dai et al.86 | MEFs | Plasmid - mouse (KOSM) | Day14 EB-NCX1+ CMs+ ECs+MEFs | Rat peritoneum patch | Mouse | 4 wks | ↓ Fibrosis, engraftment, improved LV function. |

| Kawamura et al.96 | Human dermal fibroblasts | Retrovirus – human (KOSM) | Day 25 CMs + human dermal fibroblasts | Scaffold free cell patch | Pig | 8 wks | Few hiPSC-CMs were retained at infarct site 8 weeks post transplant.↑ cardiac performance, ↓ ventricular remodeling attributed majorly to paracrine signalling. No teratomas. |

| Mauritz et al.90 | MEFs | Retrovirus - mouse (KOSM) | Day5 EB-FLK+/- CPCs | Intramyocardial injection | Mouse | 2 wks | ↑ Graft size & LV wall thickening in mice that received FLK+ CPCs as compared to Flk- cells |

| Xiong et al.97 | Human dermal fibroblasts | Lentivirus – human (KOSM) | iPSC derived ECs+VSMSs | Epicardial fibrin patch | Pig | 4 wks | Mobilization of endogenous progenitors, ↑ LV functions, ↓ scar size, neovascularization, ↑ metabolism of borderzone myocardium in cell treated immunosuppressed pigs as compared to controls. |

Figure 2. Cardiac cell therapy strategies using iPSCs and derivatives.

Patient-specific primary cells are isolated and cultured in-vitro from a suitable cell source such as blood or skin. These cells are reprogrammed to iPSCs utilizing non-integrating strategies under cGMP conditions. The resulting iPSCs are rigorously tested for pluripotency, genetic/epigenetic abnormalities and safety (Table 3,4). The iPSC clones that pass test criteria are banked for later use. Alternatively, allogeneic iPSCs can be utilized from a haplotype-matched iPSC bank. The iPSCs are then be differentiated into the desired cardiac lineage cells: cardiac progenitors, cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells or endothelial cells. The desired cell lineage or combination of cell lineages are transplanted into damaged heart via intracoronary/intramuscular injection or epicardially by tissue engineered cardiac patches. Ongoing studies will define he optimal cell preparations and associated delivery strategies for repair of the post-MI heart.

Initial studies of iPSCs for cardiac repair tested undifferentiatied iPSCs in animal models. The first study utilizing iPSCs for post MI repair was undertaken by Nelson et al.80 They used human Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc (Yamanaka factors) incorporated in lentiviral delivery vectors to reprogram murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) to miPSCs. Undifferentiated miPSCs were injected intramyocardially in either immunocompetent or immunodeficient mice after left coronary artery ligation. Four weeks post-transplantation, the immunocompetent mice showed significant improvement in ventricular function and reduced pathological remodeling due to iPSC transplantation. Histological analysis showed iPSC-derived CMs, VSMCs and ECs within damaged myocardium confirming the capacity of the injected cells to differentiate into the 3 primary cardiac lineages in vivo without evidence of tumor formation. In contrast, the majority of the immunodeficient mice developed tumors two weeks post iPSC injection and their cardiac function was progressively compromised due to tumor burden. Similarly, the Singla group transplanted undifferentiated miPSCs derived from H9c2 cardiomyoblast cells (isolated from embryonic ventricular tissue) into the peri-infarct region of immunocompetent mice and reported improvement in left ventricular function as well as reduced apoptosis due to engraftment of iPSC progeny 2 weeks post-transplant.81 No obvious teratomas were reported in the short time span of these studies. The above reports suggest that transplanting low numbers of pluripotent cells into immunocompetent post-MI mouse hearts results in cardiac-specific differentiation of iPSCs and cardiac repair. However, Ahmed et. al demonstrated that iPSCs derived from VSMCs, when injected post MI, were tumorigenic in approximately 40% of the mice.82 Others using rat iPSCs in an immunocompetent, allogeneic rat model reported tumor incidences (both intra and extra cardiac sites) that were independent of cell dose, transplant duration and presence or absence of MI.83 These reports challenged the hypothesis that cardiac microenvironment (native or post-infarct) is sufficient to direct pluripotent cells exclusively towards cardiac lineages. In general, the field has accepted that undifferentiated pluripotent cells (ES or iPS) are undesirable for clinical applications due to their tumorigenic potential; nonetheless, the above studies provided proof-of-principle that iPSCs hold promise for post-MI cell therapy.

Ongoing studies have focused on testing differentiated iPSC derivatives for post-MI repair. One strategy to obtain differentiated iPSC derivatives is to differentiate the iPSCs in embryoid bodies (EBs) and isolate the contracting regions. The contracting cell aggregates can be enzymatically treated to provide singularized cardiomyocytes, cardiac progenitors and likely other cell types. Using this cell isolation approach, Pasha et al. transplanted cells into infarcted areas of immunocompetent mice immediately after LAD ligation. Four weeks post-transplantation, reduced pathological remodeling and improved ventricular contractility were observed without tumor formation.48 The same group has also utilized micro-dissected beating aggregates from retroviraly reprogrammed SM-iPSCs84 and bone marrow MSC derived iPSCs85 for post MI injection and reported positive effects on cardiac function. The positive effects were partly attributed to paracrine signaling. Although the authors refer to cells isolated from micro-dissected EBs as cardiac progenitor cells/CMs it should be noted that spontaneous EB differentiation results in a mixture of contracting CMs, differentiating cardiac progenitor cells, VSMCs, ECs and potentially cell types of other lineages. Hence, the beneficial effects on cardiac function reported in these studies are complex, as it is difficult to tease out the exact contribution of the various undefined cell types that were injected post-MI. However, it is important to note that mice injected with micro-dissected beating clusters in these studies did not form teratomas, unlike the undifferentiated iPSCs. These experiments demonstrate the potential utility of using pre-differentiated iPSC-derived cell types for post MI repair.

To provide more defined, differentiated cell populations for transplantation, Dai et. al engineered a transgenic mouse iPS cell line that expressed GFP under the control of cardiac-specific NCX1 promoter to purify CMs from differentiating EBs.86 In this study, a tissue patch was generated for application to the post-MI heart by seeding purified iPSC-CMs, CD31-selected iPSC-ECs, and murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) on rat peritoneum patches (Tri-patch). Inclusion of MEFs dramatically improved the formation of organized blood vessels throughout the patch. The Tri-patches were placed over the infarcted myocardium one week after coronary ligation. Four weeks after patch implant, the mice that received Tri-patch showed a significant reduction in LV fibrosis as compared to MEFs only patch. This study did not perform comparative analysis between the functional benefits from CM only or EC only patches as compared to Tri-patch. Also, there was no information comparing direct cell injection versus Tri-patch application for post MI therapy. The use of MEFs in this study is another limitation because this cell source is heterogeneous, derived broadly from mouse embryos, and comparable populations for human clinical applications are not available. Nevertheless, this study was the first study to examine cardiac tissue engineering with iPSC therapy.

It is a matter of debate whether terminally differentiated cell types like CMs, VSMCs, or ECs compared to multipotent, yet tissue-committed, cardiac progenitors cells (CPCs) will be more suitable for cardiac repair. CPCs as compared to differentiated cardiomyocytes are scalable and can be propagated to generate large number of cells as would be required for post-MI cell therapy. CPCs are multipotent and can differentiate into VSMCs and ECs along with CMs. These cell types are equally important for normal function of the heart. Also, CPCs may have superior mechanical and electrical coupling capability as compared to CMs and other differentiated cell types when delivered to the injured myocardium.87-89 The first proof-of-principle study using iPSC-derived defined CPCs in post-MI cell therapy was published by Mauritz et al.90 They retrovirally reprogrammed MEFs into iPSCs and isolated Flk1 +/Oct4-CPCs from day 5 differentiated EBs via fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). The Flk1+ and FLK1- cells were then injected into mouse LV walls after LAD ligation and heart function was monitored for two weeks. Reduced cardiac remodeling and improved function was observed in both groups as compared to PBS controls. Mice that received Flk1+ cells had significantly larger grafts and increased LV wall thickening. The Keller group was the first to identify Flk1 (KDR in humans) as a marker for CPCs and is the most extensively characterized CPC surface marker to date.91, 92 Although Flk1 also marks hematopoietic stem cells at an earlier stage in development, it has been well documented that cardiac lineage cells are enriched in Flk1 expressing cells from day 4 onwards in mouse EB differentiation. This report puts forth a convincing argument that iPSC-derived CPCs hold promise for future transplantation studies.

In order for iPSC technology to reach clinical applications, preclinical testing is necessary with human-iPSCs and in large animal models such as pigs, canines, sheep or nonhuman primates. The tissue volume and number of functioning cardiomyocytes in these large animals are much more representative of human hearts. Furthermore, clinically relevant imaging and delivery techniques can be employed in these large animal models. Templin et al. published an initial study reporting use of human iPSCs in a pig MI model.93 They engineered a transgenic human iPSC line expressing sodium iodide sympoter to enable long-term tracking of transplanted cells via single photon emission computed topographic imaging. Ten days after inducing an MI in pigs, hiPSCs/hiPSCs+ hMSCs were introduced by an intramyocardial injection and imaged for up to 15 weeks (123I was infused by intracoronary injection before imaging). 123I signal was detected at the injection site for hiPSC+hMSC group 12-15 weeks post injection, where the hiPSC differentiated into endothelial cells. On the contrary, no signal was detected in the hiPSC only group. This indicates that hMSC co-injection was critical for the long term survival and engraftment of transplanted hiPSCs. MSCs have been reported to secrete antiapoptotic and immunomodulatory factors that facilitate post-MI repair94, 95. No teratomas were detected during the course this study, even though the pigs were treated with immunosuppressant drugs. In another recent large animal study, Kawamura et al. developed a scaffoldless hiPSC derived cardiomyocyte cell sheet for application in a pig MI model.96 The iPSCs were reprogrammed from human dermal fibroblast via retroviral infection of Yamanaka factors and differentiated into high purity CMs by modulating the Wnt pathway. A small amount of fibroblasts and endothelial cells were also present in the differentiated cultures. CMs were then seeded onto UpCell dishes (CellSeed, Tokyo, Japan) along with human dermal fibroblasts to form scaffold free hiPSC-CMs cell sheet. UpCell dishes are thermo sensitive and cause cells to spontaneously detach and form a sheet when incubated at room temperature. These cells sheets were then transplanted over the infarcted myocardium and cardiac functioning and CM engraftment was monitored after 8 weeks. Animals transplanted with hi-PSC-CMs sheets showed significant improvement in cardiac function, had reduced fibrosis and increased capillary density around the infarct region as compared to controls. The positive effects were mainly attributed to paracrine signaling. Few of the transplanted CMs engrafted into the host MI site. The majority cells were lost, which may have been due to insufficient immunosuppression. One study tested the impact of transplanting human iPSC-derived endothelial cells combined with human iPSC-derived smooth muscle cells in an immunosuppressed pig ischemia/reperfusion model.97 The iPSC-ECs and iPSC-VSMCs were delivered via an epicardial fibrin patch over the infarct bed. This study demonstrated improvements in LV function with reduced scar size in the cell treated group relative to placebo group based on MRI imaging. In addition, the function and metabolism of borderzone myocardium was improved by cell therapy. Histology provided evidence for neovascularization of the borderzone with some smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells being of human origins in the capillary network. These important studies provided the first test of human iPSC derivatives in a preclinical large animal model and provided encouraging results. Future studies testing other iPSCs-derived cell lineages such as cardiac progenitors or CMs in these large animal models are anticipated and may provide even better repair. However, this is just the beginning of large animal studies, and future work will need to examine dose optimization, delivery methods, and long-term safety endpoints.

As in studies with other cell sources post-MI, multiple underlying mechanisms of benefit have been described following transplantation of iPSCs and iPSC derivatives (see Figure 1). Remuscularizaiton of the heart has been the focus, but typically the extent of transplanted cell engraftment and survival has been relatively sparse suggesting the impact exceeds that expected for small grafts. A recent study transplanting porcine iPSC-ECs into a mouse model provided compelling evidence that the improvement in myocardial function largely occurred by a paracrine mechanism.98 In the future, the cellular preparation(s) prepared from iPSCs can be optimized to harness the most potent mechanisms for repair.

Transitioning to Clinical Trials and cGMP Processing of iPSC Products

The path from the research lab to clinical trials for iPSC-based therapeutics shares similarities to other cell therapeutics in many respects, but there are also unique aspects. The shared goals for cell products include developing a reproducible manufacturing process, eliminating or minimizing the use of raw materials that introduce risk, establishing suitable quality control test methods, and establishing the procedures and documentation required to produce the cell therapeutic according to current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) guidelines as well as current Good Tissue Practice (cGTP). Compliance with the cGMP regulations is a continuum of increasing compliance from the initial production of material for phase 1/2a clinical trials through to final launch of the commercial product. In addition, relatively unique considerations arise regarding use of iPSC products in cell therapy including the quality, robustness and safety of the reprogramming process, distinct approaches for autologous compared to allogeneic applications, and a reproducible differentiation process to produce highly defined cellular products free of undifferentiated pluripotent cells.

Considerations for autologous vs. allogeneic

One of the key considerations for developing an iPSC therapeutic is whether cell products will be autologous or allogeneic. An autologous therapeutic obviously provides a major benefit from the standpoint of addressing the key issue of rejection of the cell transplant. However, the choice of an autologous therapeutic also comes with a number of potential challenges from a manufacturing and regulatory perspective. First, a manufacturing process for an autologous therapeutic must be able to handle the wide range of patient-to-patient variability. Differences in patient age, disease condition and genetic/epigenetic background can all potentially impact the consistency of the quality and safety of the final cell therapeutics. Extensive process development and process validation studies may be required to demonstrate the ability of the process to handle the variability in the starting cell source. It is also worth noting that an autologous therapeutic may pose an increased risk of tumor formation since the patient would not be expected to launch an immune response against the autologous graft.

The alternative choice of an allogeneic cell therapeutic allows well characterized cell banks to be established for each therapeutic. This is a key consideration in applications where genetically modified cells are used to deliver therapeutic proteins. The issue of rejection is obviously a key consideration for allogeneic cell therapeutics. However, the ability to generate human leukocyte antigen (HLA) diverse banks offers one potential solution to this problem. Requirements for the use of immunosuppression may be minimized or potentially eliminated depending on the tissue that is being replaced and the required degree of HLA matching. For example, it has been suggested that iPSCs derived from 150 unique HLA-homozygous donors could cover 90% of the Japanese population.99 Due to greater genetic diversity many more unique donors would be required to cover the American population.

Early-Stage Process and Assay development

One of the biggest challenges in harnessing the potential of iPSCs is the inherent variability in the cell manufacturing process. This variability can be caused by variability in the quality of the starting cell source, differences in the quality of critical raw materials, differences in growth and differentiation protocols and differences in testing methods. Identifying and controlling the variability in the process and demonstrating that it does not introduce unacceptable risk is an important requirement for developing a cGMP compliant manufacturing process. For example, a key requirement for cell therapeutics is that they be produced in a manner that prevents the introduction of microbial or fungal contaminants at any step in the process. Standardized, robust methods for growing cells, evaluating critical raw materials (e.g., medium, growth factors), differentiating cells, and performing quality control testing are needed early in the development program.

Development, qualification and validation of quality control (QC) assays are another key aspect of development that must be addressed early. QC assays are typically developed and qualified in parallel with the manufacturing process. Key QC assays should be developed and qualified prior to initiating process qualification studies so that these assay are in place to support analysis of product from the qualification runs. Qualification involves demonstrating assay capabilities and that the assay is suitable for the intended application. Establishing a reference standard for the cell therapeutic is also important early in development as this will allow variability in the assay to be tracked. Potency assays represent one of larger challenges for assay development.

Material for Pre-clinical Testing and Human Clinical Trials

Once the process and assay development stage of the project is completed, material is typically produced for the pre-clinical animal studies to support the Investigation New Drug (IND) application that will be filed with the FDA prior to human clinical trials. A key consideration in producing the cells for these animal studies is ensuring that the final cell product that is used in the animal studies is representative of the cell therapeutic that will be used in the human clinical trial. If possible, identical cell banks, raw materials, process and QC testing should be used to produce the cells for animal studies. Again, variability in the starting cell source for autologous cell therapeutics may represent a significant challenge in determining suitable cells for evaluation in pre-clinical animal studies.

The pre-clinical animal studies must address areas of concern regarding the safety of the transplanted cell product. The concerns include the impact of off-target cells and the potential for teratoma formation due to residual undifferentiated cells or the generation of karyotypically abnormal cells. It is therefore critical that aspects of the process that could impact the quality of the cells with respect to attributes like residual undifferentiated cells, including starting cell material, are identical between cells produced for animal studies and human clinical trials. A dialogue should be established with the FDA to ensure that any intended process changes that are anticipated in moving from animal studies to clinical production do not represent significant changes.

iPSC Bank Production

For allogeneic cell therapeutics, establishing a bank of the starting cell material is usually done in the early stages of development. Typically a single Master Cell Bank or a two-tiered system with a Working Cell Bank is produced and tested to insure that the starting material for the manufacturing process is consistent. For autologous iPSC therapeutics, establishing a large iPSC bank is not necessary; however, establishing a small bank of the intermediate iPSCs following the reprogramming step will allow variability from the reprogramming step to be identified and potentially minimized. Establishing an intermediate bank with some level of QC testing will help to insure that a more consistent iPSC will enter the differentiation steps of the manufacturing process. Moreover, the existence of the intermediate bank will allow production of addition cells if the differentiation stage of the process is not successful or additional cells are needed for treatment.

The iPSC Master Cell Banks (MCBs) are produced starting with iPSC clones from the reprogramming process. Several iPSC colonies are typically selected and screened to ensure that they meet specifications such as no bacterial/fungal/mycoplasma contamination, acceptable growth characteristics, normal karyotype, and appropriate iPSC marker expression. An iPSC clone that meets these specifications is selected and moved into production and expanded to create the MCB using a manufacturing process that is clearly defined in manufacturing procedures. The manufacturing process should minimize the use of animal-derived raw materials wherever possible and complete traceability should be maintained for all materials used in MCB production. Cell bank production is performed according to established manufacturing SOPs. Methods have previously been described for the expansion of pluripotent stem cells using completely defined, xeno-free cell culture medium and attachment matrix.100, 101 All aspects of the process are documented from starting cell source and all materials used in reprogramming and production through to the final harvest, cryopreservation, and Quality Control testing. Cell Bank testing for adventitious agents is a critical part of developing cell lines for use in clinical production. Typical testing that is performed on an iPSC MCB is outlined in Table 3.

Table 3. Proposed testing for iPSC master cell banks.

| Test | Description |

|---|---|

| Identity | Short Tandem Repeat (STR) testing |

| Viable Cell Count | Trypan Blue dye exclusion |

| Bacterial/fungal Contamination | Testing for bacterial and fungal contamination according to 21 CFR 610.12 |

| Mycoplasma Contamination | Direct culture in broth and agar, indirect test using indicator culture/DNA stain. Assay conditions meet the FDA's PTC requirements |

| Karyotype | G-band on 20 metaphase spreads |

| Cell Marker Expression | Flow cytometry for human ES cell marker expression (e.g., Oct-3/4, SSEA-1/3/4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81) |

| Human Pathogen Testing | Performed on donor including HIV 1, HIV 2, Hepatitis B virus (HBV), Hepatitis C virus (HCV), and Treponema pallidum, and for leukocyte-rich tissues Human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV-I/II) and CMV |

| In vitro Adventitious Agent Testing | ICH cell line testing on 3 cell lines – MRC5, Vero, NIH 3T3/Hs68 |

| Additional pathogen testing | Additional testing performed based on risks introduced by reprogramming vectors and materials used in the manufacturing process |

| Residual Reprogramming Vector | PCR or Southern Blot to detect and map residual reprogramming vector |

iPSC Differentiation to the Final Cell Product

The differentiation stage of the manufacturing process should be initiated using iPSCs from a cell bank or culture that has been subjected to the QC testing discussed above. This will ensure that cells entering the differentiation process meet key criteria to help minimize variability in the differentiation process. The differentiation process should be developed and optimized to address four main issues: minimize undefined or animal-derived raw materials, ensure that the process is sufficiently robust to handle variability in the starting iPSCs, ensure that the process is scalable to meet future projected demands, and minimize off-target cell types and residual undifferentiated cells.

Quality Control testing of the final cell therapy should be designed to accommodate the product format and preparation procedures. Abbreviated QC testing may be required for releasing products that are prepared fresh for each administration. A summary of typical QC testing for an iPSC therapeutic is provided in Table 4. Some of these tests may be performed on intermediate cells while others may have a rapid method that is performed prior to release that is followed by a more rigorous method. For example, in cases where fresh cells are administered to patients, there is not sufficient time to perform the standard sterility test which requires a fourteen day incubation period. In this case, the FDA typically asks for a rapid test method (e.g., gram stain) to detect contamination with a follow-up full sterility test. A plan must be in place to address the potential scenario of a failed sterility test of a product that has already been administered to a patient. Other critical assays, such as residual undifferentiated cells, will be more challenging to address in this situation and may need to be performed on an intermediate sample so that results are available prior to release of the cell therapeutic to the clinic.

Table 4. Quality control testing plan of the final cell product.

| Attribute | Method | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Pre and Post-thaw Viable cell recovery | Trypan blue or other viability assessment | > 70% |

| Identity test | Short Tandem Repeat | Matches iPSC MCB |

| Bacterial Endotoxin | Kinetic chromogenic LAL (final cell prior to seeding on substrate) | < 5 EU/mL |

| Mycoplasma | PCR (validated) or PTC method (direct and indirect culture) | No Contamination |

| Sterility Test | Gram stain for fresh product 21 CFR 610.12, bacteristasis and fungistasis | No Contamination |

| Cell Surface Markers | Flow cytometry assay for - Positive markers: specific for cell type Negative markers: specific for off-target cells |

> X% Expression <Y% Expression |

| Residual Undifferentiated iPSCs | Flow cytometry or qPCR assay for expression of pluripotent markers (e.g., Oct-3/4, Nanog, Sox2, SSEA-3/4, TRA-1-60/1-81) | < Z% |

| Potency | Functional assessment of cell performance | Establish by Phase 3 |

Clinically Relevant Cell Delivery and Tracking

It is appealing to consider that iPSCs or their derivatives may home, engraft, mechanically and functionally couple with the infarcted myocardium, regenerate and improve cardiac contractility. However, the myocardium is an extremely complex and dynamic tissue with cells aligned and interconnected in a structured extracellular matrix that is highly vascularized. Further complicating this area of investigation is that methods used to deliver cells may be just as important therapeutically as the intrinsic regenerative potential of the cells themselves. Despite numerous cardiac cell therapy trials worldwide, variables such as the cell delivery method, infusion rates, timing, geographic distribution and dose continue to remain poorly defined.

A variety of cardiac cell delivery methods have been described and can be broadly categorized as i) intravascular infusion (ie. peripheral vein infusion, direct antegrade coronary artery infusion, direct retrograde coronary sinus infusion), ii) intramuscular injection (epicardial injection, transendocardial needle injection and iii) cellular scaffolds that are applied to the epicardial surface.102, 103 Each delivery method has both advantages and disadvantages. Peripheral vein infusion is simple, inexpensive and non-invasive, but cell retention in the heart is extremely low. Intravenous infusion relies on intact homing and a large proportion of cells trap in the lung vasculature.104 Direct intracoronary and retrograde coronary sinus infusion can be performed minimally invasively using available catheters, but these approaches suffer the problem of poor cell retention and the need for patent vessels supplying the target myocardium. Large cells such as ESC's and iPSC's are not well suited to intravascular infusion, as vascular plugging can occur and the ischemic zone may be extended. Epicardial injection through a thoracotomy incision offers improved cell retention and is not dependent on intact vascular conduits; however, this approach is invasive and is perhaps not clinically practical for the recent post-MI patient. Small incision, thoracoscopic delivery is more appealing but injecting into posterior heart locations may be challenging. Adhesions related to prior sternotomy from past coronary artery bypass surgery for example, is an additional barrier to this approach. Further, general anesthesia is typically required for these epicardial delivery approaches. Catheter-based transendocardial delivery involves a needle tipped catheter that is advanced from a peripheral artery, retrograde through the aortic valve and into the left ventricle. While still minimally invasive, this approach offers the ability to target widely and precisely throughout the left ventricle. Imaging systems such as electro-anatomic mapping and multimodality image fusion methods have been developed to assist cath lab operators in targeting the site of injections.105, 106 Recent excitement has been generated through applying cellular scaffolds or “patches” on the cardiac surface via a sternotomy incision or using small incision thoracoscopic techniques.107, 108 It is likely that the optimal cell delivery method will be closely linked to the type of stem cell and its mechanism of therapeutic effect.

Complementing cell delivery strategies are methods to track transplanted cells in vivo. Such tracking enables understanding of cell retention, engraftment and routes of cell egress from the myocardium following delivery. This information can be used to guide optimization of cell delivery methods, dosing regiments, and timing of dosing including repeat dosing. Various cell labeling and imaging methods have been explored to track transplanted cells and are described in detail elsewhere.109, 110 The sensitivity of detecting the label associated with cells, the spatial resolution of the imaging modality used, and detrimental effects of the labeling procedure on the stem cells vary significantly between cell tracking methods. In general, the iPSC derivatives can be labeled using either direct labeling with image tags (.e.g magnetic nanoparticles for MRI) or indirect labels such as reporter genes (e.g. HSV-TK for PET). Direct methods of labeling have the advantage of simplicity, and several safe tags have been clinically tested. However, these direct labels can leak out of cells and persist after cells die, and thus cautious interpretation of the imaging data are required. In contrast, indirect cell labeling typically uses an engineered reporter gene that is incorporated into the cells genome to track living transplanted cells and their cellular progeny, but the challenges associated with this method are related to genetically modifying the cell product. While optical techniques including fluorescence and bioluminescence imaging have proven useful in small animal studies, these studies are of limited value in clinical studies because of light attenuation. Human cardiac cell therapy studies to date have used PET, SPECT, or planar gamma camera imaging for monitoring acute cell retention with directly labeled cells. Studies of long-term cell engraftment and survival have not yet been accomplished clinically, but as techniques to safely genetically engineer stem cell lines improve, such long-term studies are anticipated and will advance the field. iPSCs like ESCs may be more amenable to these genetic modifications given their unique ability to proliferate in culture and undergo genome editing.

Safety Consideration from iPSC-based Therapies

Tumorigenicity

A hurdle for use of pluripotent cells in regenerative medicine is their tumorigenic potential, and while this risk is shared for ESCs and iPSCs there are some distinct risks associated with iPSCs. A shared property of both iPSC and ESC is teratoma formation following injection of undifferentiated cells into immune-compromised mice. Although teratomas are regarded as benign tumors, such tumor formation could be a major problem for clinical applications. Therefore, efforts at removing undifferentiated cells and obtaining pure differentiated cell populations have been pursued. A variety of selection strategies have been investigated including the use of genetically engineered cell lines to express a cell lineage-specific promoter driving the expression of reporter gene (e.g. GFP) or an antibiotic resistance gene.111, 112 In addition, efforts to identify optimal cell lineages using cell surface markers are being advanced.71, 113 The prolonged culture of ESCs and iPSCs including scale-up and differentiation processes provide opportunities for genetic abnormalities to develop which could be tumorigenic. It has also been observed that some ESCs and iPSCs exhibit upregulation in some miRNAs commonly found in cancers.114

There are also factors that can specifically impact the risk of tumorigenesis in iPSCs including the reprogramming process itself as well as the somatic cell source for reprogramming.115, 116 The initial mouse iPSC lines generated using c-myc as one of the reprogramming factors were prone to tumor formation, but even in the absence of c-myc, some mouse iPS lines when differentiated into neurospheres formed tumors when transplanted into mouse brains (see Okano et al., for review).68 Another concern is that the starting somatic cells used for reprogramming may have acquired somatic mutations which will be carried through to the iPSCs. Furthermore, mutations in iPSC lines tend to be concentrated in cancer-related genes.117 Only long term studies of transplanted cells in animal models will truly allow assessment of tumorigenesis risk, but the choice of animal models for testing can be complex. Many studies have used immune-compromised animals to allow direct testing of human cells, but it is possible that normal immune surveillance mechanisms will reduce or prevent some tumor risk in the true therapeutic context. Additional research and experience are needed to determine appropriate standards for this testing.

Genetic abnormalities

The genetic integrity of human iPSC lines will be critical for safe therapeutic applications. Like human ESCs, human iPSCs can exhibit chromosomal aberrations.118 In iPSCs, these aberrations can originate with the somatic cell used for reprogramming or as a result of culture adaptation. Routine karyotype analysis is used to identify aneuploid lines and typically exclude them from further development as a potential therapeutic tool. Less commonly, higher resolution evaluation for chromosomal integrity is performed using comparative genomic hybridization or single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays. Most recently, high-throughput sequencing technology has allowed in depth genetic analysis of iPSC lines and documented the presence of novel point mutations in the iPSC. It is estimated based on a study of 22 human iPSC lines that there are on average six protein-coding point mutations per iPSC line.117 About half of these mutations arose in fibroblasts used for reprogramming at low frequency while the other half occurred during or after the reprogramming process. These spontaneous mutations were found to be clustered in genes commonly mutated in cancer. The functional significance of the point mutations in the cells has not been directly tested as of yet, and how variable different cell lines will be in this regard is unknown. Will each individual iPSC line require exome or whole genome sequencing to confirm safety? Will screening a small panel of key disease causing genes be adequate? A normal karyotype will be required for an iPSC line to be considered for therapeutic applications, but some degree of higher level genetic analysis will also likely become part of standard safety evaluation.

Immunogenicity of iPSC

One of the appealing aspects of iPSC-based therapies is that an autologous cell source can be used. It has been generally assumed that autologously derived iPSCs would be immune-tolerated by the recipient after transplant. However, Zhao et al. first reported immune rejection in autologously transplated miPSCs.119 They transplanted ESCs and MEF derived iPSCs from B6 mice into syngenic recipients and observed that only iPSC derived teratomas had T cell infiltration, a classic sign of immune rejection. iPSC immunogenicity was partly credited to coding sequence mutations (that iPSCs can acquire from their parental somatic cells or during reprogramming) and epigenetic differences between ESCs and iPSCs which can lead to abnormal antigen expression during iPSCs differentiation. This unexpected finding raised questions over the therapeutic potential of autologous iPSCs. However, this study had some limitations. First, the iPSC lines were compared to only one mESC line. In order to establish that the immunogenicity was specific to iPSCs, more mESCs lines would need to be included in the study as it is well known that mESC lines themselves have diverse differentiation potential. Additionally, this study used pluripotent iPSCs for teratomas formation and thus the immune rejection could have been stimulated by tumorogenesis rather than simply the immunogenicity of the iPSCs.120 Studies testing immunogenicity of iPSC-derived, differentiated cells soon followed. Guha et al.121 and Araki et al.122 reported that miPSC-derived differentiated cells do not illicit an immune response after transplantation in syngeneic recipients. Immunogenecity of iPSCs may be reduced by deriving them from less immunogenic somatic cells. Liu et al observed that neural progenitor cells (NPCs) differentiated from umbilical cord derived iPSCs were less immunogenic as compared to NPCs differentiated from skin fibroblasts derived iPSCs.123

For transitioning iPSC technology to clinical trials, the immunogenicity of human iPSC-derived cells needs to be examined. The appropriate preclinical model to characterize the immunogenicity of such human cell products is not well established. One approach is to reconstitute severely immunodeficient NOD/SCID-IL2Rγ−/− (NSG) mice with humanized immune system.124 In these humanized mice ‘autologous’ and allogeneic cell products can be characterized for their long-term engraftment or rejection.

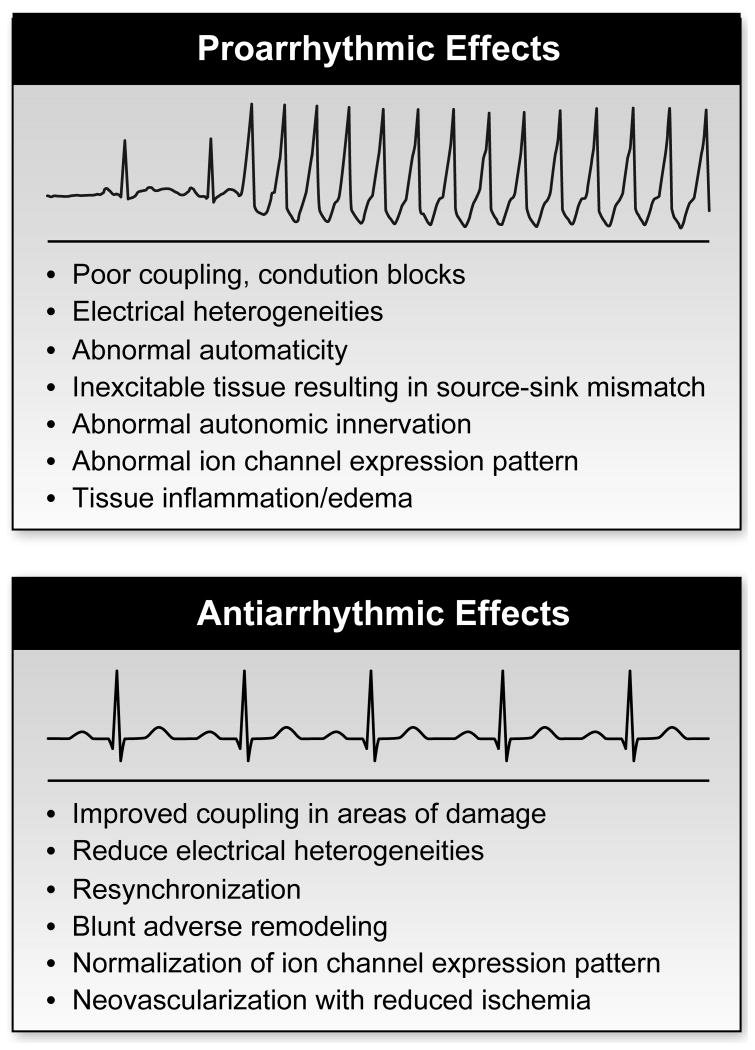

Arrhythmia risk

One of the serious risks of cardiac cell therapy is potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias. The post infarction heart is a vulnerable substrate for the generation of ventricular arrhythmias, and theoretically cell therapy could modify this substrate to either lower or raise the risk of clinically significant ventricular arrhythmias (Figure 3).125, 126 The pro-arrhythmic or antiarrhythmic effects of cell therapies will depend on the cell type(s) transplanted, the integration and coupling of the cells, and the intrinsic properties of the cells. In addition, it is possible that the risk profile will be dynamic potentially changing from pro-arrhythmic effects to antiarrhythmic effects as repair is impacted. Cell therapy can be envisioned as promoting multiple possible arrhythmic mechanisms such as introducing conduction blocks and electrical heterogeneities thus providing substrate for reentrant arrhythmias. In addition, abnormal automaticity of the transplanted cells could initiate arrhythmias. Triggered activity from abnormal repolarization of the transplanted cardiomyocytes or abnormal calcium cycling could likewise increase the risk of arrhythmias. Alternatively, if the dominant effect of cells is to improve coupling in the areas of damage for resynchronization and repair the heart, the impact could be to reduce arrhythmia risk.

Figure 3. Arrhythmia risk from cellular therapies.

Cell therapy has the potential to induce as well as prevent arrhythmias in the post-MI heart. Potential mechanisms for antiarrhythmic and proarrhythmic effects are listed.

Experimental data in animal models examining specifically the impact of cell therapy post-MI on arrhythmia risk are limited. The importance of transplanted cells being able to form connexin 43 containing gap junctions for proper electrical integration and low arrhythmic risk has been highlighted by studies transplanting skeletal myoblasts which normally do not express connexin 43 or couple to cardiomyocytes.127, 128 The studies of ESC-derived cardiomyocytes transplanted post-MI that have looked specifically at arrhythmia risk have found both pro-arrhythmic effects in one study and antiarrhythmic effects in a second study of human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes.129, 130 Understanding and resolving these apparently conflicting results will be important for safely advancing these therapies. In addition, the optimal model for assessing arrhythmia risk is not yet clear as rodents lack the cardiac tissue volume present in humans and larger mammals which may be an essential feature for genesis of some arrhythmias.

Completed clinical trials of cardiac cell therapy in general have not identified major arrhythmia risk at this point. Although an early study of myoblast therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy found frequent ventricular arrhythmia in treated patients, there was no control group for comparison in this high risk patient population.131 None of the phase II randomized trials of bone marrow mononuclear cell therapy post-MI have found increased incidence of arrhythmia following cell therapy, and a meta-analysis of cardiac post-MI cell therapy trials likewise suggested no proarrhythmic effects based on existing data.132 Nevertheless, the risk of arrhythmias remains a real concern that will merit continued vigilance.

Remaining Questions for iPSC-based Clinical Applications

Despite remarkable progress in the understanding of iPSCs since their discovery in 2006 and rapidly advancing technology, there remain major questions in defining the biology of these cells with special relevance to long-term clinical applications. What is the reprogrammed iPSC state and how stable is it? Are iPSCs equivalent to ESCs, and does it matter for clinically relevant cell types? Are differentiated progeny of iPSCs phenotypically and functionally stable or are they prone to further phenotypic changes such as premature senescence? What cell types derived from iPSCs and at what level of maturity are optimal for post-MI therapy? How can long term survival of the cells be promoted for robust regeneration?

Studies comparing ESCs and iPSCs have pointed to the similarity of the stem cell types, but these studies have also indicated clear differences in gene expression, epigenetics, and miRNA profiles. Functional assays on ESC and iPSCs support comparable pluripotency properties with the formation of teratomas containing derivatives of the three primary germ layers. In the case of mouse iPSCs, even more stringent functional tests of pluripotency such as germline transmission and tetraploid complementation have been demonstrated for some iPSC lines;133-135 however, such tests are not possible for human iPSCs. Although iPSCs show much greater similarity in gene expression pattern to ESCs than to the starting cell type which was reprogrammed, multiple studies have demonstrated that iPSCs exhibit clear differences in gene expression compared to ESCs.136, 137 These differences in gene expression between iPSC and ESC are greatest for low passage iPSCs, yet some differences persist regardless of passage number.137 Distinct culture conditions and unique genetic backgrounds can contribute to some of the experimentally observed variations in gene expression between iPSCs and ESCs. In addition, the epigenetic state of iPSC and ESCs, although highly similar, is not identical.125, 138 For example, clear differences in DNA methylation have been described between iPSCs and ESCs. There is evidence of epigenetic memory in iPSCs with retention of some methylation patterns of DNA from the cell of origin.49, 139-142 Thus, the prevailing evidence suggests that although ESCs and iPSCs are both clearly pluripotent stem cells, they are not fully equivalent in all of their characteristics. Whether these differences are problematic or advantageous for therapeutic applications is not known.

How stable and robust are the differentiated cell lineages from iPSCs? For clinical applications, the desired cell type ideally needs to exhibit functional properties appropriate for the long-term reconstitution of the organ. Some studies have raised the question of premature senescence in the case of hematopoietic cells differentiated from iPSCs.143 In addition, iPSCs exhibit an epigenetic memory that can bias differentiation towards the starting cell lineage.49 Furthermore, the epigenetic marks retained in iPSCs from the starting cell lineage can persist in cells differentiated to different lineages.125, 138 Because ESCs have been more extensively characterized and evidence of long-term stable cardiac grafts has been obtained for ESC-derivatives in animal models, comparison between ESC- and iPSC-derived cardiac cell types is an important goal in the field. Our initial characterization of cardiac differentiation of human iPSCs demonstrated that they are highly comparable to ESCs in terms of efficiency in forming contracting embryoid bodies, expression of cardiac specific genes during differentiation, proliferation, sarcomeric organization, electrophysiological properties, and chronotropic regulation by the β-adrenergic signaling pathway.74, 144 Recently, Gupta et al. and Van Laake et al. published studies comparing the global transcriptomes of cardiac lineage cells derived from ESCs and iPSCs.145, 146 They reported that mouse ESC- and iPSC-derived cardiac lineage cells were similarly enriched for cardio-specific genes and only a minority of the analyzed genes were differentially expressed. The differences in gene expression between ES- and iPS-derived cardiac lineage cells were no greater than differences between cardiac lineage cells derived from different ES cell lines. In spite of minor differences in gene expression, sarcomeric organization, electrophysiological properties and calcium handling of ES and iPS derived CMs were indistinguishable.145 These studies revealed a surprisingly high degree of similarity (transcriptional as well as functional) between the differentiated cardiac progeny of ES and iPS cells, suggesting that differences between gene expression among pluripotent ES and iPS cells narrow after/during lineage commitment. So if the differentiated progeny of ES and iPS reveal no significant differences, how much consideration should be given for the differences in their pluripotent states? Although these initial in vitro comparisons are encouraging, long-term engraftment studies in animal models and particularly large animal models are needed to demonstrate the stability and robustness of the cellular phenotype.

Although a variety of different cellular preparations differentiated from iPSCs have been studied in post-MI animal models as described in Table 2, the optimal cell preparation remains unknown. Few side-by-side comparisons of different cell preparations have been done. Will a pure population of iPS-CMs be optimal, or is a mixed population including endothelial and smooth muscle cells be better? Alternatively, could delivery of cardiac progenitor cell derived from iPSC provide greatest therapeutic benefit? Defining the optimal cell preparation does not stop at choosing the desired cell type(s), but the functional properties and particularly the maturity of the cells is another important variable as studies have indicated that, at least for iPSC-CMs, the phenotype is that of embryonic or fetal cardiomyocytes, not adult. While there are potential advantages of transplanting more fetal-like cardiomyocytes including their smaller size, relative resistance to ischemia and oxidative stress, there are potential disadvantages such as their automaticity that could trigger arrhythmias and lack of mature excitation-contraction coupling which could limit their functional contractile output. Again additional studies are needed particularly in large animal models which can provide comparisons of different cell preparations. Ideally, a standardized large animal model could facilitate comparisons between different studies as well.

If the greatest promise of iPSC products is to truly regenerate the myocardium with transplanted cells functionally integrating into the heart, then the long term survival of the donor cells is essential. However, most studies that have examined long term survival of ESC- and iPSC-derived cell preparations have shown that the number of surviving cells diminishes logarithmically over days or weeks.17, 93, 147 The reasons for this cell loss over time are not clear but may relate to the hostile environment in the post-MI remodeling heart, lack of adequate perfusion, slow immune rejection, or intrinsic properties of the transplanted cells limiting their ability to adapt and survive in the native heart. A variety of approaches have been tested to improve survival such as injecting ESC-CMs with a prosurvival cocktail containing a variety of growth factors, anti apoptotic agents and anti-oxidants.17 An alternative approach is to use tissue engineering principles to generate scaffolds for optimal cell delivery and survival which ideally will integrate into the myocardium.108 Perhaps transplanting the right combination of cells could promote long term survival as suggested by a study in a porcine MI model in which co-transplanting hMSCs promoted the survival of hiPSCs derivatives for at least 15 weeks.93 These early studies provide hope that robust myocardial regeneration may be possible in the future with continued optimization and innovation.

Conclusions

Overall, iPSC technology has opened up new approaches for cell-based therapies following myocardial infarction. There are appealing aspects of this cell source including autologous cell products, large banks of well characterized genetically defined cells, and a wide range of possible therapeutic cellular products. Preclinical studies primarily in small animals and beginning studies in larger animals have shown promising initial results. Clinical experience with iPSCs is beginning with the first-in-man trial of an iPSC product transplanting autologous retinal pigment epithelial cells to treat age-related macular degeneration in Japan. Cardiovascular clinical applications will likely follow as ongoing research defines the optimal cell preparations and best delivery strategies as well as ensures safety.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the outstanding contributions of many researchers in the field whose work could not be directly cited due to space constraints.

Sources of Funding: TJK receives funding from the NIH from grants U01HL099773, R01EB007534, and R01 HL108670. PAL is recipient of an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship Award 12PRE9520035. DJH and ANR receive funding from NHLBI Contract No.HHSN268201000010C (PACT)

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BMP

Bone morphogenetic protein

- CMs

Cardiomyocytes

- CPCS

Cardiac progenitor cells

- DKK

Dickkopf-related protein 1

- EB

Embryoid body

- ECs

Endothelial cells

- ESCs

Embryonic stem cells

- FACS

Fluorescence activated cell sorting

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- iPSCs

Induced pluripotent stem cells

- MCBs

Master cell banks

- MEFs

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- MI

Myocardial infraction

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

- NPCs

Neural progenitor cells

- QC

Quality control

- SMs

Skeletal myoblasts

- TTFs

Tail tip fibroblasts

- Vegf

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VSMCs

Vascular smooth muscle cells

- Wnt

Wingless/INT protein

Footnotes

Disclosures: TJK is a founding shareholder and consultant for Cellular Dynamics International which produces iPSC products for drug discovery, toxicity testing and research applications.

References

- 1.Leobon B, Garcin I, Menasche P, Vilquin JT, Audinat E, Charpak S. Myoblasts transplanted into rat infarcted myocardium are functionally isolated from their host. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:7808–7811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232447100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel J, McKay R, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murry CE, Soonpaa MH, Reinecke H, Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Rubart M, Pasumarthi KB, Virag JI, Bartelmez SH, Poppa V, Bradford G, Dowell JD, Williams DA, Field LJ. Haematopoietic stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiac myocytes in myocardial infarcts. Nature. 2004;428:664–668. doi: 10.1038/nature02446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Kofidis T, Weissman IL, Robbins RC. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature. 2004;428:668–673. doi: 10.1038/nature02460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunde K, Solheim S, Aakhus S, Arnesen H, Abdelnoor M, Egeland T, Endresen K, Ilebekk A, Mangschau A, Fjeld JG, Smith HJ, Taraldsrud E, Grogaard HK, Bjornerheim R, Brekke M, Muller C, Hopp E, Ragnarsson A, Brinchmann JE, Forfang K. Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schachinger V, Erbs S, Elsasser A, Haberbosch W, Hambrecht R, Holschermann H, Yu J, Corti R, Mathey DG, Hamm CW, Suselbeck T, Assmus B, Tonn T, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1210–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]