Abstract

The palmaris longus is considered a phylogenetic degenerate metacarpophalangeal joint flexor muscle in humans, a small vestigial forearm muscle; it is the most variable muscle in humans, showing variation in position, duplication, slips and could be reverted. It is frequently studied in papers about human anatomical variations in cadavers and in vivo, its variation has importance in medical clinic, surgery, radiological analysis, in studies about high-performance athletes, in genetics and anthropologic studies. Most studies about palmaris longus in humans are associated to frequency or case studies, but comparative anatomy in primates and comparative morphometry were not found in scientific literature. Comparative anatomy associated to morphometry of palmaris longus could explain the degeneration observed in this muscle in two of three of the great apes. Hypothetically, the comparison of the relative length of tendons and belly could indicate the pathway of the degeneration of this muscle, that is, the degeneration could be associated to increased tendon length and decreased belly from more primitive primates to those most derivate, that is, great apes to modern humans. In conclusion, in primates, the tendon of the palmaris longus increase from Lemuriformes to modern humans, that is, from arboreal to terrestrial primates and the muscle became weaker and tending to be missing.

1. Introduction

The palmaris longus (PL) is considered a phylogenetic degenerate metacarpophalangeal joint flexor muscle in humans [1] and a small vestigial forearm muscle [2]; it is the most variable muscle in humans [2–4], showing variation in position, duplication, and slips [2] and could be reverted [5]. It is frequently studied in papers about human anatomical variations in cadavers and in vivo [6]; its variation has importance in medical clinic, for example, vascular-neural compression [7], in surgery by using its tendon for grafting or other reconstructions [2, 4, 7], in radiological analysis, in study about high-performance athletes [8], and in genetics and anthropologic studies [2].

This muscle presents significant divergences as to its frequency in different humans groups [2, 7, 9–12]; it can be absent in some individuals of the genera Pan and Gorilla [6], but it is always present in Hylobates, Pongo [9, 10], and Sapajus [13], and its absence has not been reported in other primates.

Most studies about PL in humans are associated with frequency or case studies, but comparative anatomy in primates and comparative morphometry were not found in scientific literature. The comparative anatomy associated to the morphometry of palmaris longus could explain the degeneration observed in this muscle in two of three of the great apes (i.e., genera Pan and Gorilla) and modern humans.

Hypothetically, the comparison of the relative length of tendons and belly could indicate the pathway of the degeneration of this muscle; that is, the degeneration could be associated with increased tendon length and decreased belly from more primitive primates to those most derivate, that is, great apes to modern humans.

Therefore, the aim this work was to compare the anatomy and to verify the relative tendon/belly length of the palmaris longus in some primates from the New World and Old World and modern humans, associating data observed with those from the literature.

2. Material and Methods

This work was previously approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Goiás, state of Goiás, Brazil (CoEP-UFG 81/2008), for human and nonhuman primates studied in Brazil. For other primates, the rules of animal care in the USA and Japan were followed.

2.1. Samples

This study evaluated 14 adult human cadavers (males), allocated at the Laboratory of Human Anatomy, Federal University of Goiás, Brazil; six exemplars of adult Sapajus libidinosus (5 males and 1 female) and one exemplar of adult Callithrix sp. (male) allocated at the Laboratory of Anthropology, Biochemistry, Neuroscience and Primates' Behavior (LABINECOP), Federal University of Tocantins, Brazil; three exemplars of adult Macaca fuscata (males) allocated at the Laboratory of System Emotional Science, Toyama University, Japan; and one exemplar of adult Ateles sp. (male), one neonate Pongo sp. (male), one neonate and one child Pan sp. (males), one adult Callithrix sp. (male), two Aotus sp., two Lemur catta (one male, one female), and one Propithecus sp. (male) allocated at the Laboratory of Evolutionary Biology, Howard University, USA.

2.2. Dissection, Documentation, and Measures

Human cadavers, Sapajus sp., and one forearm of child Pan sp. had been dissected for other purposes, but other specimens were dissected for purposes of this work. The muscles were photographed by digital camera and their length was measured by metallic measure tape and digital politer (Niigara Seiki model DN 150). The values of measures were standardized to specific measure of the digital politer. Three measures of each structure were made and the average was used for purpose of statistical analysis. The tendons were measured from the point no part of the belly associated to the tendon could be seen by naked eye to the palmar aponeurosis at the level of the radio's head. Some comparison data from other primates were not observed in this work and were obtained from the literature, for example, Gorilla sp. and Hylobates sp. The frequency of muscles, whenever possible, was based on scientific literature.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the StatPlus:mac AnalystSoft Inc./2009 software to calculate the average, standard deviation and compare the mean length values. To effect comparative anatomy, statistics was performed based on Aversi-Ferreira [14] and Aversi-Ferreira et al. [15] and data on muscle frequency, origin, and insertion from literature [10, 13] was used and compared against data of this work. To perform the statistics, simple comparative nonparametric method was used to compare two different species associated with anatomical concepts of normality and variation as nominal variables. Relative frequency (RF) was defined as

| (1) |

where N is the total number of specimens and nv is the number of individuals presenting variation of the normal pattern; therefore, RF means the structure normality in a population sample.

When more than one parameter was used, they were related to specific weighted values with respect to their degree of relevance in comparative analysis. Parameters with less variation in phylogenetic terms were assigned a higher value. Therefore, origin, insertion, innervation, and presence of muscle in terms of frequency and type of fiber arrangement were assigned weights 4, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively.

The weighted average of frequencies (WAF) was calculated using the RF values:

| (2) |

where RF1 is the frequency of muscle's origin and P 1 is 4; RF2 is the frequency of muscle's insertion and P 2 is 4; RF3 is the frequency of innervation and P 3 is 3; RF4 is the frequency of the presence of muscle and P 4 is 2; and RF5 is the type of belly arrangement and the P 5 is 1. The frequencies of RF to humans, Pan sp., and Gorilla sp. were obtained from Gibbs [10], who cited the absence of palmaris longus from 3.9 to 20.4%; therefore, nv was calculated based on the average of these numbers, that is, 12.15%, and N was considered to be 100%; therefore, RF to human was 0.878. The nv value for chimpanzee was 19 and the N value was 28, and RF was 0.678; for gorilla, the nv value was 6 and the N value was 19, and RF was 0.316. The type of fiber arrangement was considered to be 1 to Lemuriformes and New World primates and 0.5 to the others, because this was considered here as an intermediate character among these primates.

To consider the phylogenetic proximity between the structures studied, the difference in the relative frequency was calculated or Comparative Anatomy Index (CAI) between samples from different species:

| (3) |

where indices i and ii represent samples 1 and 2.

From the previous equations, it follows that CAI value close to zero represents greater similarity between samples, whereas CAI closer to 1.0 implies higher divergence between samples. Therefore, the greater the numerical distance between values, the greater the divergence in relation to the palmaris longus muscle between species.

3. Results

In all primates studied here, the PL tendon, originated from medial humeral epicondyle and inserted into the palmar fascia, was innervated by the median nerve. A close relationship between the palmaris longus tendon and the fascia of the forearm was observed, which is similar to other flexor muscles of the forearm. The belly of palmaris longus was easily distinguished from the other muscles of the forearm in all studied species, except for the only exemplar of Ateles sp., in which the flexor muscles formed one group of bellies from the elbow with a separation of tendons close to the wrist (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Photos of the forearms of (a) Propithecus sp. (0.45x, left); (b) Lemur catta (0.52x, left); (c) Sapajus libidinosus (0.34x, right); (d) Ateles sp. (0.1x, right); (e) Callithrix sp. (0.3x, right); (f) Aotus sp. (0.8x, right); (g) Macaca fuscata (0.34x, right); (h) Pongo sp. (0.79x, left); (i) Pan sp. (0.23x, left). From (a) to (f), muscles are pennate and from (g) to (i) are fusiform. ∗ indicates the palmaris longus.

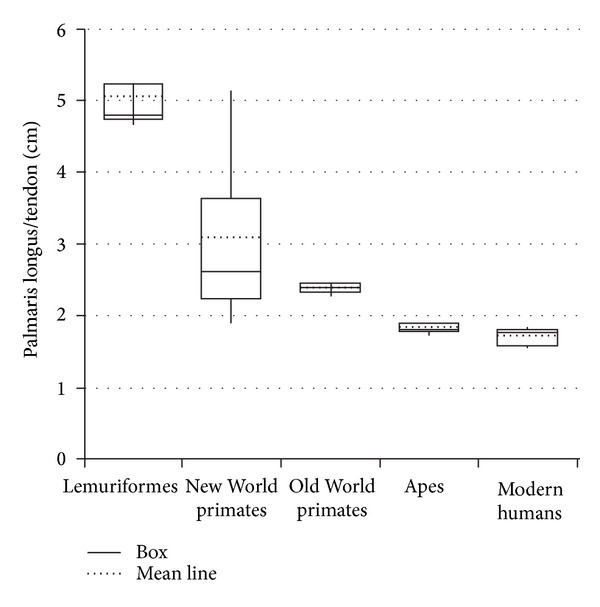

Regarding the type of fiber arrangement in the belly, the palmaris longus tendon presented an aspect similar to pennate in all Lemuriformes and New World primates (Figure 1), but fusiform to Macaca fuscata (unique exemplar of Old World primates) and to apes (Pongo sp. and Pan sp.) and modern humans. The average palmaris longus/tendon length showed significant differences between species studied in this work (Table 1, Figure 2). Shorter tendons were observed in Lemuriformes and longer in modern humans (P < 0.05, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Measures of the palmaris longus, palmaris longus tendon, and palmaris longus/tendon relationship for species of primates and primate groups.

| Specimens (n) | Total | Tendon | Total/tendon | Primate groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern humans (28) | 25.51 (±1.69) | 15.06 (±1.75) | 1.71 (±0.13) | Modern humans†, Δ, ∗, + |

| Pan sp. (3) | 8.83 (±1.62) | 4.95 (±0.91) | 1.78 (±0.04) | Apes†, Δ, ∗, + |

| Pongo sp. (2) | 8.30 (±0.10) | 4.40 (±0.30) | 1.89 (±0.15) | |

| Macaca fuscata (6) | 17.30 (±0.43) | 7.30 (±0.5) | 2.37 (±0.12) | Old World primates†, Δ, ∗ |

| Aotus sp. (4) | 6.8 (±0.47) | 3.2 (±0.50) | 2.09 (±0.23) | New World primates†, Δ |

| Callithrix sp. (3) | 4.35 (±0.19) | 1.72 (±0.23) | 2.53 (±0.08) | |

| Ateles sp. (1) | 25.3 | 10.0 | 2.53 | |

| Sapajus libidinosus (11) | 10.71 (±1.50) | 2.99 (±0.51) | 3.81 (±1.07) | |

| Lemur catta (2) | 8.6 (±0.50) | 1.9 (±0.0) | 4.53 (±0.27) | Lemuriformes† |

| Propithecus sp. (2) | 11.25 (±0.05) | 2.2 (±0.20) | 5.16 (±0.49) |

†Significant difference among Lemuriformes and other groups.

ΔSignificant difference among New World primates and other groups.

*Significant difference among Old World primates and other groups.

+Significant difference between apes and modern humans.

Figure 2.

Graph showing the mean line relative to the palmaris longus/tendon length of primate groups.

Significant differences were observed between averages (P < 0.05) calculated for all groups, that is, Lemuriformes and other groups, New World primates and other groups, and Old World primates (Macaca fuscata) and other groups, and for apes and modern humans (Table 1, Figure 2). Nevertheless, to Aotus sp., specifically, in comparison to Macaca fuscata and apes, differences were not observed.

The CAI indicates that Lemuriformes and New World primates share similar characters to PL (CAI = 0) while these features are more derived in Gorilla sp. (CAI = 0.133) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistics of the comparative anatomy of palmaris longus.

| Taxon | PAF | CAI = |PAFi − PAFii| | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propithecus sp. | 1 | Reference (most primitive characters) | |

| Lemur catta | 1 | 0 | |

| Callithrix sp. | 1 | 0 | |

| Sapajus sp. | 1 | 0 | |

| Ateles sp. | 1 | 0 | |

| Macaca fuscata | 0.964 | 0.036 | |

| Pongo sp. | 0.964 | 0.036 | |

| Modern humans | 0.947 | 0.053 | |

| Pan sp. | 0.918 | 0.082 | |

| Gorilla sp. | 0.867 | 0.133 |

PAF is the weighted average of frequencies; CAI is Comparative Anatomy Index.

4. Discussion

The large variations in the prevalence of the PL among modern humans may be indicative that this muscle is degenerating [1], and its small belly may suggest it is a vestigial muscle [2].

Although there are several studies investigating the frequency of PL in modern humans, only a few recent studies have compared PL frequency in nonhuman primates [9, 10, 16–18]. From such studies, it was found, for example, that the frequency of PL in Gorilla sp. is much lower than in humans and chimpanzees, even though humans and chimpanzees are the only species in which absence of PL has been reported. The PL is found in Gorilla sp. from 15% to 63% according to some authors [10, 16, 17, 19, 20] and could be considered absent in gorillas according to [18].

In this sense, considering only the frequency of this muscle in primates, PL would be more degenerative in Gorilla sp. Also, if degeneration is considered a derived characteristic of PL, it is more derived in Gorilla sp. than in other primates and modern humans. Indeed, it is reasonable to suggest that PL is a degenerative muscle because, according to Meglioli [21], its agenesis is associated with a recessive gene.

Notwithstanding, when parameters such as origin, insertion, innervation, frequency and type of belly fibers are compared together and using specific weight, (i.e., when CAI is applied; for review, see Aversi-Ferreira [14] and Aversi-Ferreira et al. [15]) Gorilla sp. shows the greatest numerical distance from the primitive character considered in Propithecus sp., followed by Pan sp., modern humans, Pongo sp. and Macaca fuscata in decreasing order.

In fact, the different variation factor observed in the CAI calculation can be explained by the low frequency in the number of specimens and species and by the different types of muscle fibers of the belly muscle obtained from the literature and from the present study. To Lemuriformes and New World primates, CAI indicates no quantitative difference; that is, the calculated value is zero; but to Macaca fuscata and Pongo sp., the only difference is type of fiber arrangement.

In order to obtain more objective parameters, the relative length of the tendon was studied, that is, the length of the PL muscle divided by the length of the palmaris longus tendon. Its measure indicates, indirectly, the muscle relative strength because smaller belly indicates less sarcomeres acting together to generate contraction [22]. Therefore, a longer tendon indicates less muscular force. According to the data obtained here, this relation (PL muscle divided by the length of the palmaris longus tendon) decreases from Lemuriformes to modern humans.

Interestingly, the comparison between means of the relative measures of PL among these groups of primates (P < 0.05) showed significant differences between one group and all other groups. One discrepancy was observed in the measures obtained from Aotus sp., a New World primate, in which the average measures were similar to Macaca fuscata and apes, but it was not possible to associate it with any aspect considered in this work. Putatively, a weak PL is observed in modern humans and apes and strong in Lemuriformes. Therefore, it is possible to hypothesize that the tendon length decreases from arboreal to terrestrial primates. In line with this, Ankel-simons [23] reports that great apes move in a quadrupedal Knuckle-walking manner; the Macaca genus is terrestrial quadruped; all New World primates are highly arboreal, and all Lemuriformes, except for Lemur catta, spend around 1/3 of the time on the ground.

Specifically to modern humans, the average measure of the PL tendon obtained here, that is, 15.06 (±1.75), was different from those reported for other Brazilians cadavers [12] (11.99 ± 1.52). Apparently, these differences are due to criteria for length measurements of the palmaris longus tendon in both studies.

On the other hand, different fiber arrangement of the belly of PL in Lemuriformes and New World primates compared to Old World primates, apes, and modern humans was observed. The tendon begins in the belly, which involves the tendon laterally up to approximately the wrist in Lemuriformes and New World primates, characterizing a pennate muscle; whereas from Macaca fuscata to modern humans, the tendon begins after the end of the belly, observed via naked eye, characterizing a fusiform muscle.

This characteristic affects the muscular strength, the fusiform muscle generates a more direct contraction, but to modern humans, apes, and Macaca fuscata, the bellies are shorter; in a pennate muscle, however, the physiological cross-sectional area is considerably larger than its anatomical cross-sectional area. Therefore the pennate muscle, ceteris paribus, generates more force [24]. In addition, they are longer in Lemuriformes and New World primate than in other primates.

The number of animals per species and the number of species used here allowed inferring the following conclusions. First, the more derived characteristics of PL are found in apes, especially in Gorilla sp. relative to evolutionary aspects measured by CAI, but a shorter tendon is verified in modern humans. Second, the path to the degeneration of the PL seems to follow a decreased tendon associated with modification in the type of belly fibers from pennate to fusiform; therefore, in primates with more derived thoracic limbs, the weaker PL.

To our knowledge this is the first study to present an evolutionary anatomical comparison of the PL. Further studies could indicate more accurately the evolutionary pathway followed by PL from primitive to derived primates associated with aspects such as the muscular force difference between primates and verification of anatomical aspects in more species and consider intra- and interspecific variations

5. Conclusions

Apparently, in primates, the PL tendon relative size seems to increase from ancestors genera to more derived ones. This suggests that this muscle is weaker in terrestrial primates when compared to arboreal primates. The PL tendon seems to be more derived in Gorilla sp., considering the factors analyzed here, but the tendon is longer in modern humans.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Standring S. Gray’s Anatomy the Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 2008. Pelvis girdle and lower limb. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kigera JWM, Mukwaya S. Frequency of agenesis Palmaris longus through clinical examination—an East African study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028997.e28997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray H. Gray Anatomia. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Guanabara Koogan; 1979. Membro superior. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Telles VS, Ernesto BAL. Consideraciones anatómicas de los músculos inconstantes. MedUnab. 1998;1(3):165–170. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cope JM, Looney EM, Craig CA, Gawron R, Lampros R, Mahoney R. Median nerve compression and the reversed palmaris longus. International Journal od Anatomical Variation. 2009;2:102–104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machado ABM, Di Dio LJA. Frequency of the musculus palmaris longus studied in vivo in some Amazon indians. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 1967;27(1):11–20. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330270103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babinski MA, Valente KMA, Savedra CMS, Burity CHF, Sabrá AMS. Variação anatômica do músculo palmar longo associado a ausência do arco palmar superficial e compressão do canal de Guyon. Acta Scienteae Medica. 2008;2(2):54–58. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fowlie C, Fuller C, Pratten MK. Assessment of the presence/absence of the palmaris longus muscle in different sports, and elite and non-elite sport populations. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(2):138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Testut L, Latarjet A. Tratado de Anatomia Humana. Barcelona, España: Salvat Editores; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibbs S. Comparative soft tissue morphology of the extant Hominoidea, including man [Ph.D. thesis] The University of Liverpool, Inglaterra; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kayode AO, Olamide AA, Blessing IO, Victor OU. Incidence of palmaris longus muscle absence in Nigerian population. International Journal of Morphology. 2008;26(2):305–308. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angelini Júnior LC, Angelini FB, Oliveira BC, Soares SA, Angelini LC, Cabral RH. Use of the tendon of the palmaris longus muscle in surgical proedures: study on cadavers. Acta Ortopedica Brasileira. 2012;20(4):226–229. doi: 10.1590/S1413-78522012000400007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aversi-Ferreira TA, Vieira LG, Pires RM, Silva Z, Penha-Silva N. Estudo anatômico dos músculos flexores superficiais do antebraço no macaco Cebus apella . Bioscience Journal. 2006;22(1):139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aversi-Ferreira TA. A new statistical method for comparative anatomy. International Journal of Morphology. 2009;27(4):1051–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aversi-Ferreira TA, Maior RS, Carneiro-e-Silva FO, et al. Comparative anatomical analyses of the forearm muscles of Cebus libidinosus (Rylands et al. 2000): manipulatory behavior and tool use. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):8 pages. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022165.e22165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preuschoft H. Muscles and joints of the anterior extremity of a gorilla (Gorilla gorilla Savage et Wyman, 1847) Gegenbaurs morphologisches Jahrbuch. 1965;107(2):99–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarmiento EE. Terrestrial traits in the hands and feet of gorillas. American Museum Novitates. 3091:1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diogo R, Pastor JF, Ferrero EM, et al. Photographic and Descriptive Musculoskeletal Atlas of Gorilla: With Notes on the Attachments, Veriations, Innervation, Synonymy and Weight of the Muscles. Enfield, USA: Science Publisher; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keith A. On the chimpanzees and their relationship to the gorilla. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1899;67(2):296–312. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loth E. Anthropologie Des Parties Molles (Muscles, Intestins, Vaisseaux, Nerfs Peripheriques) Paris, France: Mianowski-Masson et Cie; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meglioli GT. Étude de I’hérédité du muscle petit palmaire (Musculus palmaris longus) dans la population belge. BullEtin de La Société Royale Belge D'Anthropologie et de Préhistoire. 1965;75:67–86. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brand PW, Beach RB, Thompson DE. Relative tension and potential excursion of muscles in the forearm and hand. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1981;6(3):210–219. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(81)80072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ankel-Simons F. Primate Anatomy: An Introduction. Orlando, Fla, USA: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichinose Y, Kanehisa H, Ito M, Kawakami Y, Fukunaga T. Relationship between muscle fiber pennation and force generation capability in Olympic athletes. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 1998;19(8):541–546. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]