Abstract

Background

In 2003, the first phase of duty hour requirements for U.S. residency programs recommended by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) was implemented. Evidence suggests that this first phase of duty hour requirements resulted in a modest improvement in resident wellbeing and patient safety. To build on these initial changes, the ACGME recommended a new set of duty hour requirements that took effect in July 2011. We sought to determine the effects of the 2011 duty hour reforms on first year residents (interns) and their patients.

Methods

We conducted alongitudinal cohort study of 2323 interns entering one of 51 residency programs at 14 university and community-based GME institutions or graduating from one of four medical schools participating in the study. We compared self-reported duty hours, hours of sleep, depressive symptoms, well-being and medical errors at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months of the internship year between interns serving before (2009 and 2010) and interns serving after (2011) the implementation of the new duty-hour requirements.

Results

58% of invited interns chose to participate in the study. Reported duty hours decreased from an average of 67.0 hours/week before the new rules to 64.3 hours/week after the new rules were instituted (p<0.001). Despite the decrease in duty hours, there were no significant changes in hours slept (7.0→6.8; p=0.17), depressive symptoms (5.8→5.7; p=NS) or well-being (48.5→48.4; p=0.86) reported by interns. With the new duty hour rules, the percentage of interns who reported committing a serious medical error increased from 19.9% to 23.3% (p=0.007).

Conclusions

Although interns report working fewer hours under the new duty hour restrictions, this decrease has not been accompanied by an increase in hours of sleep or an improvement in depressive symptoms or wellbeing but has been accompanied by an unanticipated increase in self-reported medical errors under the new duty hour restrictions.

Keywords: Graduate, Medical, Education, Residency, Work, Hours, Sleep

Background

Over the past 25 years, there has been a growing concern that the long duty hours and sleep deprivation that have traditionally been common during residency training can lead to adverse consequences for both residents and the patients that they treat.1 Recognition of this concern, has sparked intense debate among policy makers, medical educators, and residents themselves about how to devise a medical education system that promotes rigorous, high-quality training while maintaining the health of residents and maximizing the safety of patients.2

Using input from the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) established a new set of duty hour recommendations that took effect July, 2011.1,3 The ACGME recommendations focus on establishing progressive responsibility through residency, with greater oversight and lower work demand for first-year residents (commonly referred to as interns), because they are the least experienced clinicians and traditionally have worked the longest hours. While the recommendations included numerous changes in supervision and in the requirement for greater oversight by programs, the most important and controversial changes related to maximum shift length for interns. A landmark study published in 2004 found that an intensive intervention designed to reduce extended intern shifts in the ICU successfully reduced the incidence of serious medical errors.4 This study, along with additional work indicating that long duty hours harms both patients5,6 and residents themselves,7,8 prompted the ACGME to restrict the maximum shift length for interns to 16 hours.9 Other research, however, has shown a substantial increase in patient handoffs with shift length restriction and a higher rate of medical errors with more handoffs.10,11 Further, a recent study found that duty hour restrictions increased the stress felt by residents, despite a reduction in extended shifts.12 As a result, some residency program directors have warned that the new ACGME restrictions would result in poorer training for interns and poorer outcomes for patients.13,14 These conflicting points of view highlight the importance of evaluating the effect of the duty hour changes for interns and their patients.

As part of the ongoing Intern Health Study,15 we conducted a large, prospective, longitudinal study comparing interns serving before and interns serving after the new duty hour standards were instituted. The study solicited self-report information to evaluate the effects of the new ACGME duty hour standards on resident duty hours, sleep duration, depressive symptoms and medical errors in a sample of interns from multiple specialties and institutions across the country.

Methods

Participants

Graduate medical education (GME) institutions and medical schools who expressed interest in taking part in the Intern Health Study were included in the sample for this study.15 Fifty-one residency programs at 10 university-based and four community-based GME institutions agreed to allow us to invite their incoming residents to take part in the study. In addition, four medical schools agreed to allow us to invite their graduating students to take part in the study. In total, 4352 individuals entering internal medicine, general surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, emergency medicine, combined medicine/pediatrics, transitional year and psychiatry residency programs during the 2009, 2010 and 2011 academic years were sent an email two months prior to commencing internship and invited to participate in the study.

For 348 subjects, our email invitations were returned as undeliverable and we were unable to obtain a valid email address. Fifty-eight percent (2323/4005) of the remaining invited subjects agreed to participate in the study. The Institutional Review Board at all of the participating institutions approved the study. Subjects were compensated $40 for their time and effort. Because there was some variation from year to year in the set of residency programs assessed in the study, we performed a secondary analysis including only subjects at residency programs that took part in the study in all three years of study (See Supplementary Online Content for “Common program sub-sample analysis).

Data Collection

The data collection procedures utilized in the Intern Health Study have been detailed previously.15 Briefly, all surveys were conducted through a secure online website designed to maintain confidentiality, with subjects identified only by numbers.

Pre-Internship Assessment

Subjects completed a baseline survey 2 months prior to commencing internship that assessed general demographic factors (age, sex, marital status), and psychological factors (baseline Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depressive symptoms (PHQ-9), history of depression and a measure of personality, the NEO-Five Factor Inventory Neuroticism).16,17 The PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report component of the PRIME-MD inventory, designed to screen for depressive symptoms. A score of 10 or greater on the PHQ-9 has a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 88% for the diagnosis of major depressive disorder.18

Within-Internship Assessments

Interns were contacted via email on the first Tuesday of months 3, 6, 9 and 12 of internship year and asked to complete a previously published survey addressing work hours, sleep and medical error.15 Survey questions included, “how many hours have you worked in the past week” and “on average, how many hours have you slept per night over the past week.” To assess medical errors, the survey asked the question “are you concerned that you have made any major medical errors in the last 3 months?”19 Interns' depressive symptoms were assessed with the PHQ-9. To minimize the time burden on interns, Subjective Well-Being, assessed through the 14-item Mental Health Continuum–Short Form, was administered only at month 6.20

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (Chicago, IL). Baseline factors were compared between the pre-implementation and post-implementation cohorts with a two-sample t-test for continuous measures and a Chi-Squared test for categorical measures. A series of Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) analyses were utilized to assess the effects of the duty hour rule, while accounting for the repeated measures within subjects during internship. In the GEE analyses, cohort membership was entered as the predictor variable (pre-implementation (2009 and 2010) cohort compared to post-implementation (2011) cohort), and quarterly reports of duty hours, sleep hours, depressive symptoms and medical errors were assessed as outcomes. To evaluate differences in response to duty hour reforms among medical specialties, a cohort membership × specialty interaction term was included in these analyses. Two-sample t-tests were used to compare Subjective Well-Being between cohorts.

Results

Representativeness of the Sample

Compared to all individuals entering internship in 2009, 2010 and 2011 nationally, our sample was younger (27.5 years old vs. 28.8 years old) and included a slightly higher percentage of women (50.9% vs. 48.6%). There were no significant differences in specialty, institution or demographic variables between individuals who chose to participate in the current study and individuals who chose not to participate (demographic information for full residency programs provided by American Association of Medical Colleges; personal communication - September 17, 2012).

Pre-Internship Comparisons

For the 2323 study participants, there were no significant differences in specialty, baseline depressive symptom score, neuroticism, gender or age between the pre-implementation (2009 (N=714) and 2010 (N=772)) and post-implementation (2011 (N=837)) cohorts (Table 1; all p values=NS). Further, there were no differences in these baseline characteristics between subjects who completed one, two, three or four quarterly surveys (all p values=NS). On average, 65% of participants responded to each quarterly survey. In total, 8,099 baseline and quarterly subject assessments were completed.

Table 1. Sample Demographic Characteristics (N(%)).

| Variable | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | p value# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 345 (48.3) | 383 (49.6) | 412 (49.2) | NS |

| Female | 369 (51.7) | 389 (50.4) | 425 (50.8) | ||

| Specialty | Internal Medicine | 404 (56.6) | 412 (53.4) | 451 (53.9) | NS |

| General Surgery | 84 (11.8) | 67 (8.7) | 86 (10.2) | ||

| Pediatrics | 99 (13.9) | 117 (15.1) | 102 (12.2) | ||

| Emergency | 50 (7.0) | 60 (7.8) | 62 (7.4) | ||

| Other | 77 (10.7) | 116 (15.0) | 136 (16.3) | ||

| Age | 27.5 (3.1) | 27.6 (3.0) | 27.5 (2.7) | NS | |

| PHQ Depression Score | 2.52 (3.11) | 2.43 (3.05) | 2.47 (3.07) | NS | |

| Neuroticism | 21.4 (8.7) | 22.0 (8.8) | 21.4 (8.8) | NS | |

- Two sample T-test (continuous variables) or Chi Square (categorical variables) p value comparing 2009+2010 cohort to 2011 cohort

Internship Comparisons

Across the four quarterly assessments, the mean number of duty hours reported per week decreased significantly from a mean (SD) of 67.0±17.0 in the pre-implementation cohort to 64.3±21.7 in the post-implementation cohort (Wald Chi Square(1)=31.6; p<0.001). There was no significant effect of specialty on the change in work hours (Wald Chi Square(4)=3.34; p=0.50). The percentage of interns who reported working more than 80 hours per week decreased from 12.8% to 7.8% (Wald Chi Square(1)=28.1; p<0.001). In contrast, the mean number of reported hours slept each day was not significantly different between cohorts, with 6.8±3.7 hours of sleep for the pre-implementation cohort and 7.0±4.3 hours of sleep for the post-implementation cohort (Wald Chi Square(1)=2.3; p=0.17). The mean PHQ depression score during the year also did not change significantly between cohorts, with a mean PHQ depressive symptom score of 5.8 ± 4.8 for the pre-implementation cohort and 5.7±4.6 for the post-implementation cohort (Wald Chi Square(1)=0.37; p=0.55). Correspondingly, the percentage of interns meeting PHQ criteria for depression (PHQ score>=10) did not change significantly between cohorts, with 20.0% of the pre-implementation cohort and 18.7% of the post-implementation cohort meeting criteria for depression (Wald Chi Square(1)=0.75; p=0.39). Consistent with the depressive symptom scores, the Subjective Well-Being score did not change significantly under the new duty hour rules, with mean scores of 48.5±13.9 for the pre-implementation cohort and 48.4±13.9 for the post-implementation cohort (t(1)=-0.17; p=0.86). The percentage of interns who reported concern about making a serious medical error increased significantly from 19.9% in the pre-implementation cohort to 23.3% in the post-implementation cohort (Wald Chi Square(1)=7.3; p=0.007) (Table 2; Figure 1). There was no significant effect of specialty on the change in error rates (Wald Chi Square(4)=6.74; p=0.15). Interns in both the pre-implementation and post-implementation cohort who met PHQ criteria for depression were significantly more likely to report a medical error compared to residents who did not meet criteria for depression (35.3% vs. 17.8%; Wald Chi Square(1)=92.3; p<0.001) (Table 2; Figure 1). Results from Common program sub-sample analysis are presented in the Supplementary Online Materials.

Table 2. Duty Hours, Sleep, Depressive Symptoms and Medical Errors in Pre- and Post- Duty Hour Restriction Cohorts.

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duty Hours (hours/week)*** | 1st quarter | 68.76 | 67.07 | 66.68 |

| 2nd quarter | 68.40 | 65.87 | 63.78 | |

| 3rd quarter | 68.08 | 65.70 | 64.65 | |

| 4th quarter | 67.05 | 65.41 | 61.45 | |

| Sleep (hours/day) | 1st quarter | 6.85 | 7.13 | 7.24 |

| 2nd quarter | 6.84 | 6.51 | 7.08 | |

| 3rd quarter | 6.87 | 6.35 | 6.99 | |

| 4th quarter | 6.82 | 6.48 | 6.52 | |

| PHQ Depressive Symptom Score | 1st quarter | 6.02 | 5.47 | 5.77 |

| 2nd quarter | 5.87 | 5.86 | 5.80 | |

| 3rd quarter | 5.99 | 6.35 | 5.84 | |

| 4th quarter | 5.56 | 5.67 | 5.42 | |

| Serious Medical Error (%)* | 1st quarter | 19.3% | 17.6% | 22.7% |

| 2nd quarter | 20.4% | 22.2% | 24.2% | |

| 3rd quarter | 20.6% | 23.3% | 22.6% | |

| 4th quarter | 18.0% | 18.3% | 23.3% |

indicates P < 0.05;

indicates P < 0.001

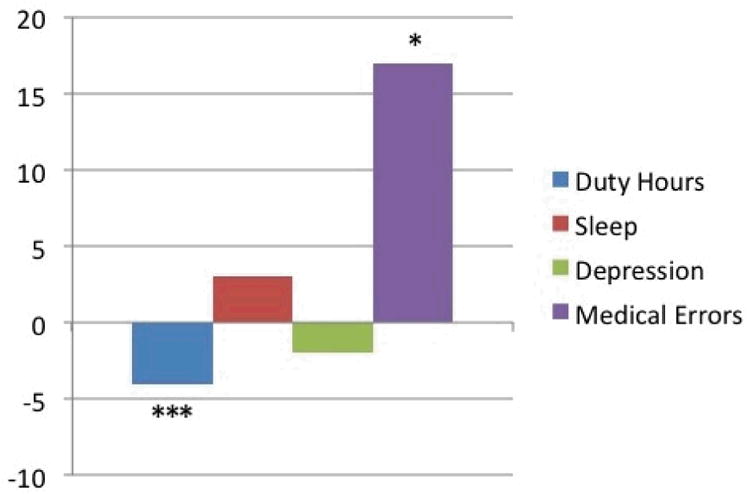

Figure 1. Percent Change in Key Variables Pre and Post Implementation of 2011 ACGME Reforms.

Figure 1 shows the percent change in outcomes pre and post 2011 ACGME reforms. Overall, work hours decreased by 4%, average number of hours of sleep per night over the past week increased by 3%, mean depressive symptoms decreased by 2%, and medical errors increase by 17% following the new ACGME guidelines. *indicates P < 0.05; *** indicates P < 0.001.

Discussion

In this prospective, longitudinal, multi-institutional study, we found that during the 2011-2012 academic year, interns reported working fewer hours but more frequently reported concerns about committing medical errors than interns serving before the ACGME duty hour reforms were implemented. Further, we find that the reforms were not associated with any reported changes in interns' sleep duration or their symptoms of depression.

Investigations of the 2003 ACGME duty hour restrictions yielded conflicting findings on whether they resulted in residents working fewer hours,21,22 but generally agreed that these restrictions did not result in increased sleep for residents.21,23,24 With the more restrictive 2011 ACGME requirements, we found clear evidence that interns were working fewer hours. Similar to the 2003 reforms however, our findings indicate that the 2011 ACGME restrictions did not significantly increase in sleep for interns. In response to the new restriction on maximum shift length, many residency programs instituted a night float system. While we did not assess which programs switched to a night float system, our results are consistent with earlier work suggesting that the implementation of a night-float system does not increase sleep for residents.25 Some studies have suggested that changing away from traditional internship schedules can reduce the number of hours preceded by little or no sleep even without having a substantial effect on total sleep hours experienced by residents12,26. Future studies should investigate whether the timing or quality of resident sleep or the number of hours worked on little or no sleep has changed with the new restrictions.

Previous work has demonstrated that physicians experience a substantial increase in depressive symptoms during internship.15,27 In this study, we found that the levels of depressive symptoms and well-being among interns were unchanged from previous cohorts, following implementation of the 2011 duty hour rules. High levels of depression have been linked to more medical errors and poorer clinical performance.19,28 In this sample, we find further evidence supporting this link, with interns meeting PHQ criteria for depression reporting medical errors (35.3%) at almost twice the rate as non-depressed interns (17.8%).

Based on information from national mortality studies and single-institution pre-post studies, the IOM concluded that the 2003 ACGME reforms did not harm patients and may have modestly improved outcomes for a subset of patients.1 However, the magnitude of the improvement in patient safety was not as substantial as some had predicted, suggesting that a decrease in continuity of care may have largely offset a reduction in fatigue-related errors resulting from the reforms.1 In contrast to the evidence suggesting a modest improvement in safety with the 2003 reforms, in this study of the 2011 reforms, we found unexpected evidence of an increase in self-reported medical errors among interns. Specifically, the average percentage of residents reporting a serious medical error during each quarter increased from 19.9% before implementation of the 2011 ACGME reforms to 23.3% after implementation. Although our analysis of errors in the common program sub-sample did not reach significance, the difference in the rate of medical errors in the sub-sample was comparable to that in the overall sample, suggesting that the lack of significance may be due to inadequate statistical power (see Supplementary Online Content).

There are multiple possible reasons that the 2011 ACGME reforms may have yet to achieve their stated goals. Given that increased sleep was a key mechanisms through which the new duty hour restrictions were intended to improve the health of residents,3 the lack of such an effect in the post-implementation cohort in our study is concerning. Designing work schedules that account for circadian phase and explicitly training residents on practices to increase sleep time and improve sleep quality may be necessary.29

In addition, for many hospitals, the new duty hour restrictions were not accompanied by funding to hire additional clinical staff.30 As a result, the duty hour restrictions may have exacerbated the problem of work compression, with residents expected to complete the same amount of work as previous cohorts but in less total time.31 Increased work compression has been associated with poorer clinical performance and decreased satisfaction among residents.32 Consistent with increased work compression, the 2011 duty hour reforms were associated with a modest, non-significantly lower level of workload satisfaction, despite being associated with a reduction in duty hours. Residents have also noted that the new duty hour rules necessitated a shift towards longer daily shifts and eliminated the reprieve of a “post-call” day.33 Evidence that resource-intensive interventions have been effective in improving resident satisfaction and patient care suggests that it may be necessary to allocate substantially more resources to achieve the improvements targeted by the ACGME reforms.32

Finally, evidence strongly indicates that implementing the new ACGME reforms has resulted in an increased number of handoffs in most residency programs.33 The increase in handoffs may be a contributing factor to the increase in self-reported medical errors with the implementation of the new duty hour. While curricula in handoff training for residents has remained largely undeveloped, initial studies of standardized handoff systems have been effective in reducing errors.34,35 Thus, more research in handoff training and broader implementation of standardized systems to improve handoffs may be necessary to ensure high quality patient care under the new duty hour regulations.36

There are important features of our study that strengthen confidence in the results. First, we studied large cohorts of residents, working in over a dozen different hospital systems, community and academic hospitals and hospitals in all major regions of the United States. The full sample provided statistical power to detect effects of small to moderate size. Second, by focusing on interns, the target of the most aggressive and controversial aspects of the 2011 ACGME reforms, the study provides important information on the core aspects of the reforms. Third, the prospective design allows us to differentiate cohort outcomes from outcomes due to pre-existing differences between the pre- and post-implementation cohorts. Fourth, by conducting quarterly assessments, we were able to obtain a picture of the ACGME reform effects throughout the year, rather than a single cross-sectional snapshot.

In addition to these strengths there are limitations to our study. The most important limitation is the self-report nature of our assessment. Although self-report represents the only practical way to gather data on a large and varied sample of subjects, this method is susceptible to subject bias, especially on topics as controversial as medical errors and duty hour reforms. We guarded against the influence of subject bias by embedding this study in a larger study with the stated aim of identifying genetic predictors of depression under stress and, thus, the likelihood of subject bias in report of medical errors and duty hours was reduced.15 Further, we did not ask interns about their opinions on duty hour reforms but queried them about more objective outcome measures of interest. Specifically related to medical errors, we did not find any evidence for trending in the self-reported error rates in the years preceding duty hour reforms or through the four quarters within years (see Supplementary Online Content). This suggests that any long-term trends towards increasing patient safety awareness did not account for the increased rate of self-reported medical errors that we identified following the implementation of duty hour reforms. While the validity of self-report is questioned in skills assessment, self-report may be a more valid measure for variables assessed in this study.37 For example, self-reported work hours matches well with swipe-in and swipe-out electronic recordings of resident work hours.38 Further, some studies showed that the substantial majority of self-reported errors were confirmed by medical record review.39,40 Other work, however has suggested that physician self-report and medical record review identified a similar number of errors, but that there was only partial overlap in the errors identified, with self-reported errors more likely to be preventable medical errors41. Although it is difficult to obtain gold standard measures (e.g., through medical record review, electronic recording of work hours, etc.) on large samples across multiple institutions, investigators were able to conduct single-program objective assessment studies of the effect of the 2003 duty hour reforms.21,42 Going forward, similar studies evaluating the 2011 duty hour reforms would provide a vitally important complement to the multi-institutional self-report results reported here.

There are other important limitations to our study. First, because the pre-implementation cohort served in 2009-10 and 2010-11 and the post-implementation cohort served in 2011-12, the differences between cohorts could have resulted from stricter enforcement of 2003 duty hour reforms, anticipation of future reforms or secular trends unrelated to duty hour reforms. Because our study spanned three sequential academic years, however, it is unlikely that long-term trends could explain the observed effects. Further, because the identified national trend has been towards improvements in the quality of care, temporal trends would, if anything, have served to obscure effects of duty hour changes.43 Second, only 58% of invited individuals chose to participate in the study. Although this is a comparatively high participation rate for a multi-institutional study, any systematic differences between participants and non-participants could introduce bias. Despite the lack of demographic differences between individuals who chose to take part in the study and those who did not, our results should be extrapolated with caution. Finally, our study only assessed the effects of duty hour reforms during the first year of their implementation. Studies should assess changes in interns' sleep and rates of depression and medical errors in future years, after hospital systems have had time to adjust to the new duty hour restrictions.

In conclusion, this large prospective pre-post study of the 2011 ACGME duty hour reforms and found that, although the reforms reduced the total number of hours that interns are on duty, they did not affect interns' duration of sleep or mental health and increased the frequency of self-reported medical errors. These concerning findings represent important early evidence that the newest ACGME restrictions, alone, have not met with immediate success in either improving the health of residents, or in leading to a reduction in self-reported errors. Further changes, targeted specifically towards improving resident education and patient care, may be necessary to achieve the desired impact of ACGME reforms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Faren Grant B.A. (University of Michigan) and Heather Bryant M.A (University of Michigan) who served as study coordinators for the project. Most importantly, we thank the participating interns and program directors for the time that they invested in this study. The project was supported by the following grants: UL1RR024986 from the National Center for Research Resources (SS), MH095109 from the National Institute of Mental Health (SS), AA013736 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (HK), and a Young Investigator Grant from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (SS). The funding agencies played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Sen had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None

Contributor Information

Dr. Srijan Sen, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan

Dr. Henry R. Kranzler, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia VAMC

Dr. Aashish K. Didwania, Department of Internal Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Dr. Ann C. Schwartz, Department of Psychiatry, Emory University School of Medicine

Dr. Sudha Amarnath, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Washington

Dr. Joseph C. Kolars, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan

Dr. Gregory W. Dalack, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan

Dr. Breck Nichols, Departments of Pediatrics and Medicine, Keck USC School of Medicine/LAC+USC Medical Center.

Dr. Constance Guille, Department of Psychiatry, Medical University of South Carolina

References

- 1.Ulmer C, Wolman DM, Johns MME. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuehn BM. New rules call for more oversight, fewer hours for first-year residents. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010 Sep 1;304(9):950–951. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES., Jr The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 8;363(2):e3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1005800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004 Oct 28;351(18):1838–1848. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart RP, Buchsbaum DG, Wade JB, Hamer RM, Kwentus JA. Effect of sleep deprivation on first-year residents' response times, memory, and mood. Journal of medical education. 1987 Nov;62(11):940–942. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198711000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine AC, Adusumilli J, Landrigan CP. Effects of reducing or eliminating resident work shifts over 16 hours: a systematic review. Sleep. 2010 Aug;33(8):1043–1053. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.8.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, et al. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jan 13;352(2):125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valko RJ, Clayton PJ. Depression in the internship. Dis Nerv Syst. 1975 Jan;36(1):26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iglehart JK. The ACGME's final duty-hour standards-special PGY-1 limits and strategic napping. N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 21;363(17):1589–1591. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1010613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidyarthi AR, Arora V, Schnipper JL, Wall SD, Wachter RM. Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign-out. Journal of hospital medicine: an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2006 Jul;1(4):257–266. doi: 10.1002/jhm.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen LA, Brennan TA, O'Neil AC, Cook EF, Lee TH. Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events? Ann Intern Med. 1994 Dec 1;121(11):866–872. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-11-199412010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auger KA, Landrigan CP, Gonzalez Del, Rey JA, Sieplinga KR, Sucharew HJ, Simmons JM. Better Rested, but More Stressed? Evidence of the Effects of Resident Work Hour Restrictions. Acad Pediatr. 2012 May 26;12:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice LB. Evidence-based evaluation of physician work hour regulations. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009 Feb 4;301(5):484. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.43. author reply 484-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea JA, Willett LL, Borman KR, et al. Anticipated Consequences of the 2011 Duty Hours Standards: Views of Internal Medicine and Surgery Program Directors. Acad Med. 2012 Jul;87(7):895–903. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182584118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;67(6):557–565. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Stability and change in personality assessment: the revised NEO Personality Inventory in the year 2000. J Pers Assess. 1997;68(1):86–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6801_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa PaM, R R. The NEO Personality Inventory: Manual. 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006 Sep 6;296(9):1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keyes CL. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2005 Jun;73(3):539–548. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landrigan CP, Fahrenkopf AM, Lewin D, et al. Effects of the accreditation council for graduate medical education duty hour limits on sleep, work hours, and safety. Pediatrics. 2008 Aug;122(2):250–258. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagsi R, Weinstein DF, Shapiro J, Kitch BT, Dorer D, Weissman JS. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education's limits on residents' work hours and patient safety. A study of resident experiences and perceptions before and after hours reductions. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Mar 10;168(5):493–500. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arora VM, Georgitis E, Siddique J, et al. Association of workload of on-call medical interns with on-call sleep duration, shift duration, and participation in educational activities. JAMA. 2008 Sep 10;300(10):1146–1153. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzgibbons SC, Chen J, Jagsi R, Weinstein D. Long-Term Follow-Up on the Educational Impact of ACGME Duty Hour Limits: A Pre-Post Survey Study. Ann Surg. 2012 Oct 12; doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825ffb33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chua KP, Gordon MB, Sectish T, Landrigan CP. Effects of a night-team system on resident sleep and work hours. Pediatrics. 2011 Dec;128(6):1142–1147. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lockley SW, Cronin JW, Evans EE, et al. Effect of reducing interns' weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failures. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Oct 28;351(18):1829–1837. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellini LM, Baime M, Shea JA. Variation of mood and empathy during internship. JAMA. 2002 Jun 19;287(23):3143–3146. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008 Mar 1;336(7642):488–491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arora VM, Georgitis E, Woodruff JN, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer D. Improving sleep hygiene of medical interns: can the sleep, alertness, and fatigue education in residency program help? Arch Intern Med. 2007 Sep 10;167(16):1738–1744. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romano PS, Volpp K. The ACGME's 2011 changes to resident duty hours: are they an unfunded mandate on teaching hospitals? J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Feb;27(2):136–138. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1936-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludmerer KM. Redesigning residency education--moving beyond work hours. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 8;362(14):1337–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1001457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMahon GT, Katz JT, Thorndike ME, Levy BD, Loscalzo J. Evaluation of a redesign initiative in an internal-medicine residency. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 8;362(14):1304–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0908136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drolet BC, Christopher DA, Fischer SA. Residents' response to duty-hour regulations--a follow-up national survey. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Jun 14;366(24):e35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okie S. An elusive balance--residents' work hours and the continuity of care. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Jun 28;356(26):2665–2667. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petersen LA, Orav EJ, Teich JM, O'Neil AC, Brennan TA. Using a computerized sign-out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events. The Joint Commission journal on quality improvement. 1998 Feb;24(2):77–87. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wohlauer MV, Arora VM, Horwitz LI, Bass EJ, Mahar SE, Philibert I. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012 Apr;87(4):411–418. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318248e766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1999 Dec;77(6):1121–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Todd SR, Fahy BN, Paukert JL, Mersinger D, Johnson ML, Bass BL. How accurate are self-reported resident duty hours? J Surg Educ. 2010 Mar-Apr;67(2):103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weingart SN, Callanan LD, Ship AN, Aronson MD. A physician-based voluntary reporting system for adverse events and medical errors. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Dec;16(12):809–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.November M, Chie L, Weingart SN. Physician-Reported Adverse Events and Medical Errors in Obstetrics and Gynecology. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol 1: Assessment) Rockville (MD): 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Neil AC, Petersen LA, Cook EF, Bates DW, Lee TH, Brennan TA. Physician reporting compared with medical-record review to identify adverse medical events. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Sep 1;119(5):370–376. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, et al. Mortality among patients in VA hospitals in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA. 2007 Sep 5;298(9):984–992. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horwitz LI, Kosiborod M, Lin Z, Krumholz HM. Changes in outcomes for internal medicine inpatients after work-hour regulations. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jul 17;147(2):97–103. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]