Abstract

Prostaglandins (PGs) are potent lipid mediators that are produced during infections and whose synthesis and signaling networks present potential pharmacologic targets for immunomodulation. PGE2 acts through the ligation of 4 distinct G protein coupled receptors, E-prostanoid (EP) 1–4. Previous in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that the activation of the Gαs-coupled EP2 and EP4 receptors suppresses inflammatory responses to microbial pathogens through cAMP-dependent signaling cascades. While it is speculated that PGE2 signaling via the Gαi-coupled EP3 receptor might counteract EP2/EP4 immunosuppression in the context of bacterial infection (or severe inflammation), this has not previously been tested in vivo. To address this, we infected wild type (WT, EP3+/+) and EP3−/− mice with the important respiratory pathogen S. pneumoniae or injected mice intraperitoneally with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Unexpectedly, we observed that EP3−/− mice were protected from mortality after infection or LPS. The enhanced survival observed in the infected EP3−/− mice correlated with enhanced pulmonary clearance of bacteria; reduced accumulation of lung neutrophils; lower numbers of circulating blood leukocytes; and an impaired febrile response to infection. In vitro studies revealed improved alveolar macrophage phagocytic and bactericidal capacities in EP3−/− cells that were associated with an increased capacity to generate nitric oxide in response to immune stimulation. Our studies underscore the complex nature of PGE2 immunomodulation in the context of host-microbial interactions in the lung. Pharmacological targeting of the PGE2-EP3 axis represents a novel area warranting greater investigative interest in the prevention and/or treatment of infectious diseases.

Keywords: Bacterial infections, monocytes/macrophages, lipid mediators, lung tissue

Introduction

A subset of patients with community-acquired pneumonia will develop severe infection requiring intensive medical therapy for complications such as respiratory failure and sepsis. For these reasons, pneumonia ranks among the 10 leading causes of mortality in the United States (1). Steptococcus pneumoniae is the most frequently isolated pathogen in severe and uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia (2), accounting for nearly 1.6 million deaths annually (3) – more than any other bacterium (4). A better understanding of the immunological factors governing the development of pneumococcal pneumonia and its complications is needed to improve both preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Prostaglandins (PGs) are small lipid molecules derived from the cyclooxygenase (COX)-dependent metabolism of the cell membrane fatty acid constituent, arachidonic acid. The PGs are recognized as potent mediators of both innate and acquired immunity. An increasingly large body of evidence suggests key roles for PGs in the modulation of pulmonary host defense (5–7). Prostaglandins E2 (PGE2), is synthesized in abundance both locally (in infected tissues including the lung (8)) and systemically (e.g. within the brain) in response to microbial invasion, where it exerts myriad effects on physiological and immunological functions (9, 10). PGE2 can exert both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects on the immune response (11–13). The latter actions counterregulate host inflammatory responses, potentially limiting collateral damage to neighboring cells and tissues and aiding in the resolution of inflammation once pathogens are contained (14). Specifically, PGE2 has been shown to inhibit the ability of alveolar macrophages to phagocytose and kill respiratory pathogens (5, 15), and to generate proinflammatory signaling molecules such as tumor necrosis factor-α (16). Though such effects might benefit the immunocompetent host, data suggest that the exaggerated production of PGE2 in certain clinical circumstances may contribute to an enhanced susceptibility to respiratory infections. For example, excessive PGE2 generation was reported to be an important determinant of risk for bacterial lung infection following hematopoetic stem cell transplantation in lethally-irradiated mice (6).

The actions of PGE2 follow the activation of four distinct cell membrane-associated G-protein coupled receptors, termed E-prostanoid (EP) 1, EP2, EP3, and EP4. EP1 receptor activation provokes Gαq-coupled increases in intracellular Ca2+, EP2 and EP4 receptors signal predominantly through Gαs, increasing cAMP, and the EP3 receptor most often reduces cAMP via Gαi coupling (17). EP3-based signaling is complicated by the existence of several receptor variants generated through the alternative splicing of mRNA transcripts (18).

In general, the suppressive effects of PGE2 on leukocyte function follow the activation of the Gαs-coupled EP2 and EP4 receptors (19), while EP1 and EP3 receptors have been implicated in vasoregulatory, hyperalgesic, and thermoregulatory responses during infection (19). Immunosuppressive consequences of PGE2-EP2/EP4 signaling in pulmonary host defense have been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo (5–7, 15). Attention has been paid to the functional consequences of inhibiting EP2 or EP4 receptor signaling during bacterial pneumonia (5–7), but almost nothing is known about the influence of the other EP receptors on host defenses, whether inside or outside of the respiratory tract.

Because EP2 and EP4 activation suppress pulmonary host defenses through increases in cAMP (5–7), while EP3 receptor signaling inhibits adenylate cyclase activity (and might therefore support antimicrobial defense mechanisms), we hypothesized that the selective deletion of the EP3 receptor would worsen the ability of infected mice to handle microbial invasion of the lungs. A worsening of host defenses against bacterial infection in EP3 null (EP3−/−) mice might also be predicted in light of the central role of the EP3 receptor in governing the febrile response (20) since fever is believed to be a critical component of immune defense against microbial pathogens (21, 22). To address the role of EP3 signaling in the context of severe pneumonia, we utilized a model of lower respiratory tract infection in wild type (WT, EP3+/+) and EP3−/− mice caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Unexpected results were revealed by these investigations, in that EP3−/− mice were protected from pneumococcal mortality. Further investigations were performed to define the physiological and immunological host responses governed by PGE2-EP3 signaling. Our studies underscore the complex nature of PGE2 immunomodulation in the context of host-microbial interactions in the lung and the importance of correlating in vitro findings with in vivo experiments.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female mice with a targeted disruption of the EP3 gene (20) backcrossed over 10 generations onto a C57BL/6 background (EP3−/− mice) were a kind gift of Dr. Shuh Narumiya (Kyoto University) and were obtained from Ono Pharmaceuticals (Osaka, Japan) and bred in the University of Michigan Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine (ULAM, Ann Arbor, MI). Age and sex-matched WT C57BL/6 mice (EP3+/+ mice) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were treated according to National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of experimental animals with the approval of the University of Michigan Committee for the Use and Care of Animals.

Reagents

RPMI 1640 cell culture medium and penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B solution were purchased from Gibco-Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Tryptic soy broth was supplied by Difco (Detroit, MI). Cytochalasin D, saponin, and MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Other reagents are listed below.

Isolation and culture of alveolar macrophages

Resident alveolar macrophages from mice were obtained via lung lavages, as previously described (23) and resuspended in RPMI 1640 to a final concentration of 1–4 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were allowed to adhere to tissue culture-treated plates for 1 h (37°C, 5% RPMI 1640. Cells were cultured overnight in CO2) followed by two washes with warm RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B (antibiotics) before use. The following day cells were washed twice with warm medium to remove nonadherent cells.

Tetrazolium dye reduction assay of bacterial killing

The ability of bacteria to survive within the alveolar macrophage was quantified using a tetrazolium dye reduction assay, as described elsewhere (24, 25). In this assay, bacterial growth is determined colorimetrically based on the ability of live bacteria to convert MTT to a purple formazan salt that absorbs light at 595 nm (A595). Briefly, 2 × 105/mL mouse alveolar macrophages, prepared as described previously (26), were seeded in duplicate 96-well tissue culture dishes. The next day, S. pneumoniae were opsonized with 10% normal rat-derived immune serum, as previously described (26). Macrophages were then infected with a 0.1-mL suspension of opsonized S. pneumoniae (2 × 107 CFU/mL; multiplicity of infection (27), 100:1) for 120 min to allow phagocytosis to occur. The bacterial killing protocol was assessed as described elsewhere (24, 25). The intensity of the A595 was directly proportional to the number of intracellular bacteria associated with the macrophages (24). Results were expressed as percentage survival of ingested bacteria, where the survival of ingested bacteria = 100% × A595 control (phagocytosis) plate/A595 experimental (phagocytosis + killing) plate.

Fluorometric assay of alveolar macrophage phagocytosis

The ability of alveolar macrophages to phagocytose S. pneumoniae was assessed using a previously published protocol for determining the ingestion of fluorescent, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled bacteria (5). Briefly, heat-killed S. pneumoniae serotype 3 were labeled with FITC as previously described (FITCS. pneumoniae) (28). 1.5 × 105 murine alveolar macrophages were obtained from the BAL fluid of naive mice and seeded in replicates of 24 in 384-well tissue culture plates with opaque sides and optically clear bottoms (Costar, Corning Inc. Life Sciences, Lowell, MA). On the following day, FITCS. pneumoniae were opsonized with 10% normal rat-derived non-immune serum. Macrophages were then infected with FITCS. pneumoniae using an MOI of 150:1 for 180 min to allow phagocytosis to occur. Trypan blue (250 μg/ml; Molecular Probes) was added for 10 min to quench the fluorescence of extracellular bacteria and fluorescence was determined using a SPECTRAMax GEMINI EM fluorometer 485ex/535em (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The phagocytic index was calculated as previously described in relative fluorescence units (5).

Measurement of reactive oxygen intermediates

Alveolar macrophages were adhered to 384 well plates at a concentration of 1.25×105 cells/well and cultured overnight in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. On the next day, the media was replaced with PBS containing 10 μM H2DCF and the cells were cultured for 1 h. The media was then replaced with warmed Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS) and the cells were stimulated with heat-killed S. pneumoniae using a multiplicity of infection of 50:1. ROI production was assessed every 30 min for 2h by measuring fluorescence using a Spectramax Gemini XS fluorometer (Molecular Devices) with excitation/emission setting at 493/522 nm.

Nitric oxide production

Alveolar macrophages were adhered to 96 well plates at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/well and cultured with DMEM supplemented with 1% sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal calf serum and pen/strep with or without 10 μg/ml of lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus (Sigma) and 10 ng/ml IFN-γ (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 24h. Nitric oxide (NO) production was determined by measuring stable nitrite (NO2-) concentrations using a modified Griess reaction with a commercially-available assay kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI).

S. pneumoniae infection

S. pneumoniae serotype 3, 6303 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was used for these studies. The virulence of this organism was maintained by subculturing bacteria obtained from the spleens of bacteremic mice and storing them at −80°C until use. Bacteria were then grown in Todd Hewitt Broth Media (BD, Sparks, MD) at 37°C in 5% CO2 to mid-log phase. The bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation (16,000 × g for 5 min), washed twice in endotoxin-free PBS (Invitrogen), and the concentration of bacteria was determined spectrophotometrically (A600). The S. pneumoniae concentration was confirmed by plating serially diluted bacteria on soy-based blood agar plates (Difco, Detroit, MI). Mice were anesthetized by an intra-peritoneal injection of ketamine 100 mg/ml (Ketaset®, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) and xylazine 20 mg/ml (Anased®, Lloyd Laboratory, Shenandoah, IA) together at a dose of 10 μl/g mouse. A small incision was made to expose the trachea and the bacterial inoculum (105 CFUs suspended in 30 μl) was injected intratracheally (i.t.) using a 26g needle. The incision was closed using 3M Vetbond™ (3M Animal Care Products, St. Paul, MN).

Bronchoalveolar lavage and cell counts

Twenty-four and 48 h post-infection, lung leukocytes were obtained from mice by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) following CO2 asphyxiation as previously described (29). Blood was collected by cardiac puncture for peripheral white blood cell counts and hematocrit levels using a Hemavet cell analyzer (Drew Scientific) operated by the ULAM Animal Diagnostic Laboratory.

Serum lactate levels

Lactate levels were determined using the EnzyChrom™ Lactate Assay Kit (Bioassay Systems, Hayward, CA) on heparinized blood samples collected from mice anesthetized with isofluorane (AErrane, Baxter) 24 h following i.t. S. pneumoniae challenge.

Histology

At 48 h post-infection lungs were harvested, perfused intratracheally with 10% buffered formalin, and immersed in formalin (McClinchey Histology Lab, Stockbridge, MI). Lungs were embedded in toto, and 5 μm hematoxylin and eosin stained sections of all lung lobes were examined blindly without knowledge of their source. Histologic lesions in the lungs consisted of multifocal neutrophilic to suppurative interstitial pneumonia that ranged from mild to focally severe; multifocal atelectasis; and (in some cases) pulmonary edema. Pleural lesions consisted of fibrinonecrotizing and suppurative pleuritis that ranged from mild to severe. Pneumonia and pleuritis were scored separately on a semi-quantititive scale where 0 = no inflammation, 1 = mild inflammation, 2 = moderate inflammation, and 3 = severe inflammation.

Temperature measurements

Murine core temperatures (Tb) were assessed using a MicroTherma 2T Hand Held Thermometer (Braintree Scientific Inc., Braintree, MA) by inserting the probe into the rectum 3–4 cm up from the anus at several time points (0, 30, 60, 120 min) after LPS injection and at 24 and 48 h post-infection.

Myeloperoxidase activity assay

The presence of myeloperoxidase in lung homogenates was determined 48 h after infection. Lung tissue was homogenized in sterile PBS after the tissues were perfused with sterile PBS to eliminate myeloperoxidase activity in contaminating blood. The homogenized tissue was stored at −80°C to lyse the cells. After thawing, the homogenates were centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 × g at 4°C. Supernatants were utilized to determine myeloperoxidase levels (in ng/ml) using a commercially available kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (EnzChek® Myeloperoxidase Activity Assay Kit, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Lung, spleen, or serum cytokine, chemokine, and PGE2 determination

Lung homogenates, obtained from mice 48 h after pneumococcal infection, and blood harvested from mice 5 h after LPS injection, were evaluated for cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-12 p70, IL-6, and MCP-1) by ELISA (R&D Duoset, R&D Systems) by the University of Michigan Cancer Center Cellular Immunology Core. PGE2 levels in lung homogenates were determined by an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI).

LPS injection

LPS (10 mg/kg) from E. coli serotype 0111:B4 (Sigma) was reconstituted in PBS and administered to mice via an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. Mice were monitored over a 7 d period for survival analysis (n=15 per group). In other animals, blood was collected for cytokine and chemokine analysis 2 h (n=5 per group) or 5 h (n=10 per group) after LPS injection. The peritoneal cavity of separate cohorts of mice (n=5 per group) were also lavaged with 1.0 ml lavage fluid. Cells were pelleted and the supernatant was harvested and frozen at −20°C until later use for cytokine measurements.

Evans blue dye method for measuring vascular permeability

Vascular leak induced by LPS was estimated based on the extravasation of Evans blue dye (30). Six h after i.p. challenge with LPS (10 mg/kg), mice received a 30 mg/ml solution of Evans blue dye i.v. (30 mg/kg via the jugular vein). Thirty min later, mice were euthanized and perfused with 5 ml ice-cold PBS via the left ventricle. The lungs and kidneys were harvested, weighed and homogenized in 1 ml of PBS. Organ homogenates were then incubated with addition of 2 ml of formamide at 60 °C for 18 h and then centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 30 min. The absorbance of the Evans blue in the supernatants was spectrophotometrically measured at 620 nm while the absorbance of contaminating heme pigments was determined at 740 nm. The following formula was used to correct Evans blue A620 for the presence of heme (A740): A620 (corrected) = A620 − (1.426 × A740 + 0.030). Data were expressed in absorbance units per gm tissue.

Statistical analysis

Survival was evaluated for differences using a log-rank test. Where appropriate, mean values were compared using a paired Student t-test or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni correction. Differences were considered significant if P ≤ 0.05. All experiments were performed on at least three separate occasions unless otherwise specified. Data are presented as mean values ± standard error of the mean unless otherwise noted.

Results

EP3−/− mice are protected from death during S. pneumoniae infection

To examine the role of PGE2-EP3 signaling in host defense against bacterial infections of the lungs, EP3−/− mice or WT C57BL/6 mice (EP3+/+) were infected i.t. with 105 CFU of S. pneumoniae. As demonstrated (Fig. 1A), infected EP3−/− mice experienced a significantly lower 10 d mortality (56%) than did infected EP3+/+ animals (90%; P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

EP3−/− mice are protected from death following S. pneumoniae infection. (A) Wild type (WT) or EP3 knockout (KO) mice were infected i.t. with S. pneumoniae as detailed in Materials and Methods. Survival was assessed over time. (B) Bacterial burdens in lung and spleen tissue homogenates were determined by counting colony forming units (CFU) as described in Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05 compared to WT levels at 48 hr after infection.

Pulmonary clearance of S. pneumoniae is enhanced in EP3−/− mice

The difference in observed mortality between EP3+/+ and EP3−/− animals could reflect the fact that PGE2-EP3 receptor signaling modulates the local immune clearance of pneumococcal organisms or limits bacterial dissemination to distant sites. To test these possibilities, bacterial burdens were measured in the lung and spleen of infected animals 24 and 48 h following i.t. inoculation. These time points were selected to allow measurements prior to the onset of animal mortality. As shown (Fig. 1B), at 48 h after infection the EP3−/− mice exhibited significantly better lung clearance of S. pneumoniae (2.39 × 105 CFU/gm lung tissue) than did infected WT animals (3.8 × 107 CFU/gm lung tissue; P < 0.05). There was a nonsignficant trend towards better clearance at the 24 h time point as well (mean CFU/gm lung tissue of 1.2 × 105 in EP3+/+ mice vs. 3.98 × 103 in EP3−/− mice; P = 0.28) while there were no differences in splenic bacterial loads (Fig. 1B).

Pulmonary inflammatory responses are similar in EP3−/− and WT mice

Data from the human U937 monocyte cell line suggest that PGE2-EP3 signaling enhances leukocyte migration (31). Conversely, PGE2 impairs neutrophil migration (32) primarily as a result of EP2 activation, with a possible contribution of EP3 (33). To assess the influence of EP3 in phagocyte influx into infected alveoli we performed BAL on mice 48 h after inoculation with S. pneumoniae. There were non-signficant trends towards reduced numbers of neutrophils and macrophages in the air spaces of EP3−/− mice (Fig. 2A) while the percentage of neutrophils and macrophages did not differ between knock out and WT mice (Fig. 2B). These similarities were confirmed through histopathological determination of inflammatory infiltrates that also showed no significant difference in severity of pneumonia (Fig. 2C). It was noted that inflammatory infiltrates were more prominent in peripheral (pleural) regions in the EP3−/− mice compared to WT animals (Figs. 4A and B). Interestingly, the amount of myeloperoxidase enzyme activity in the lung homogenates of infected animals (a surrogate marker for the presence of neutrophils) was significantly reduced in the EP3−/− mice compared with EP3+/+ controls, suggesting differences in neutrophil ingress into the pulmonary interstitial spaces rather than into alveoli (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Reduced neutrophil influx and enhanced macrophage killing of S. pneumoniae in EP3−/− mice. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected from infected wild type (WT) or EP3 knockout (KO) mice 48 hr after inoculation and assessed for leukocyte counts and differential, then expressed as (A) cells per ml or (B) as a percent of the total number of cells. AM, alveolar macrophage, PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocyte (neutrophil). (C) Lung histology scores were determined as described. (D) Myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels were quantitated in lung homogenates 48 hr after infection as noted in Materials and Methods. **P < 0.01 compared to WT levels. The ability of AMs to phagocytose (E) and kill (F) ingested S. pneumoniae was determined in vitro as detailed. *P < 0.05 compared to WT.

Figure 4.

Histopathological and immunological evidence of inflammation in EP3−/− and EP3+/+ mice. Severe suppurative interstitial pneumonia (A) and fibrinonecrotizing pleuritis (B, arrows) in lungs from infected mice. In panel A, most alveolar spaces are obscured by aggregates of necrotic neutrophils (arrows). A is from an EP3+/+ mouse and B is from an EP3−/− mouse. Both lesions were present in both mouse strains though pleuritis was more severe in the EP3−/− animals. Magnification in panels A and B was 400x; bars = 25μm. (C and D) Similar profiles of pulmonary inflammatory mediators in lung homogenates (C) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (D) from infected wild type (WT) and EP3−/− (KO) mice. Cytokine and chemokine levels were determined by ELISA after infection as described in Materials and Methods. Differences were not statistically significant. MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1.

Improved phagocytosis and killing of S. pneumoniae by alveolar macrophages from EP3−/− mice

Alveolar macrophages are a critical defender against S. pneumoniae in murine models of infection (34, 35). The capacity of alveolar macrophages to phagocytose and kill bacterial pathogens is subject to regulation by PGE2 (5, 15). We therefore infected alveolar macrophages from WT and EP3−/− mice ex vivo, to compare both phagocytosis and bacterial killing. The capacity of EP3-deficient alveolar macrophages to internalize serum-opsonized FITCS. pneumoniae was approximately 10% greater than WT cells (Fig. 2E, P < 0.05). Furthermore, bacterial killing was enhanced in the EP3−/− macrophages as shown in Fig. 2F. In these studies, bacterial survival within alveolar macrophages was approximately 57% greater in the WT cells than in EP3−/− cells (P < 0.05).

Nitric oxide production is enhanced in EP3−/− alveolar macrophages

To address potentially causal mechanisms explaining the increased bacterial killing in EP3 null cells, alveolar macrophages were assessed for their ability to generate ROIs and NO in response to inflammatory stimuli. As shown (Fig. 3A), the production of ROIs by EP3+/+ and EP3−/− macrophages was equally robust upon exposure to S. pneumoniae. The capacity for alveolar macrophages to generate NO (determined as the stable nitrite, NO2-) was determined by stimulating the cells with a combination of IFN-γ and lipoteichoic acid (Fig. 3B). While basal production was similar, EP3 null cells generated significantly greater quantities of NO2- than did WT cells (54.5 ± 1.76 μM vs. 35.74 ± 1.11 μM, respectively; P<0.001).

Figure 3.

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediate production in EP3−/− and EP3+/+ alveolar macrophages. Alveolar macrophages were isolated from uninfected wild type (WT) or EP3 knockout (KO). (A) Cells were cultured with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF) for 1h then stimulated with heat-killed S. pneumoniae using a multiplicity of infection of 50:1 (dashed lines) or were not stimulated (solid lines). Reactive oxygen intermediates (ROIs) production was assessed fluorometrically and expressed as relative fluorescence units. The data represent the mean of 3 experiments completed in quadruplicate for each time point. (B) WT or KO macrophages were stimulated with recombinant mouse interferon-γ (10 ng/ml) plus lipoteichoic acid (10 μg/ml) for 24 hr and NO2- production was determined as described in Materials and Methods. ***P < 0.001 compared to unstimulated cells; ###P < 0.001 compared to WT levels.

Local and systemic inflammatory mediators are similar in infected EP3−/− and EP3+/+ mice

PGE2 regulates the production of cytokines and chemokines during infection and inflammation primarily via EP2 and EP4 receptor activation (36, 37). In the absence of intact PGE2-EP3 communication the pulmonary (Fig. 4C and 4D) and splenic (data not shown) production of inflammatory mediators did not significantly differ after infection. There was a trend towards lower levels of TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-12 in the lung homogenates of EP3−/− animals. As expected, PGE2 levels were higher in the lungs (230.9 ± 37.7 ng/ml in WT and 241.5 ± 18.3 ng/ml EP3−/− mice) than in the spleens (150.3 ± 5.9 ng/ml in WT and 134 ± 11.7 ng/ml EP3−/− mice) of infected animals 48 h after infection (n = 5) but the differences between WT and EP3−/− mice were not significant.

Circulating leukocyte levels are lower in EP3−/− mice than in EP3+/+ mice during infection

The acute elevation of circulating white blood cell numbers, particularly neutrophils, is a usual response to moderate or severe bacterial infections. The blood leukocyte counts were determined in uninfected and infected animals to identify correlates of survival in the EP3−/− mice (Figs. 5A and 5B). Basal counts in uninfected animals were similar. At 24 h post-infection the total leukocyte count of WT mice did not appreciably change, though there were decreases in lymphocytes and increases in neutrophils in this group. Notably, circulating neutrophil and lymphocyte counts decreased significantly 24 h after infection in EP3−/− mice (Fig. 5B). No changes were observed in red blood cell or platelet numbers (not shown).

Figure 5.

White blood cell (WBC) counts are depressed during pneumococcal infection in EP3−/− mice. Cell counts were enumerated in blood samples taken before infection (A) or 24 hr after infection (B) with S. pneumoniae in wild-type (WT) and EP3 knockout (KO) mice. Lymph, lymphocytes; mono, monocytes; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocyte (neutrophil). **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared to WT counts.

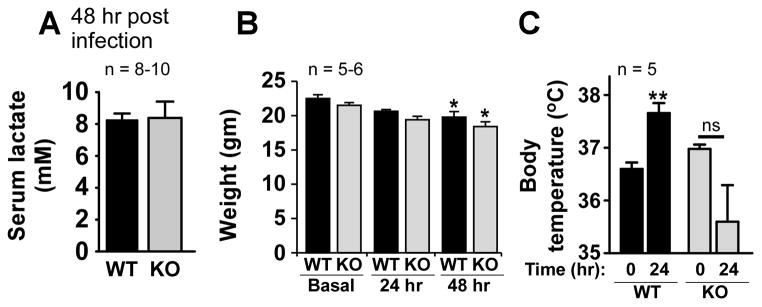

Serum lactate levels and acute weight loss are similar in EP3 null and WT mice

Tissue hypoxia during streptococcal sepsis may cause an elevation in serum lactate levels (38). The amount of tissue hypoxia induced by pneumococcal infection, as assessed by lactate determination, was similar in EP3−/− and EP3+/+ mice (Fig. 6A). Sickness in mice often results in reduced food intake and weight loss. Though both EP3 null and WT mice lost weight over the first 48 h after infection, there was no difference in this indicator of illness severity (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

EP3−/− mice exhibit similar degrees of tissue hypoxia and weight loss as wild type mice but have an impaired febrile response to infection. (A) Twenty four hr after infection, serum lactate levels were measured in wild-type (WT) and EP3 knockout (KO) mice. (B) Weights were determined for mice before and 24 and 48 hr after infection. *P < 0.05 compared to basal weight. (C) Core body temperature was measured as detailed in the text for WT and KO mice at time 0 and 24 hr after pneumococcal infection. **P < 0.01 compared to time 0. ns, non-significant.

EP3−/− mice have an impaired febrile response to pneumococcal infection

The febrile response to inflammatory non-infectious stimuli (such as LPS or proinflammatory cytokine injection) has been shown to depend on the presence of EP3 receptors in the central nervous system (9). However the role of this receptor in mediating fever during actual infection with a live pathogen has not been demonstrated. Therefore, the core Tb in mice was measured before and during infection (Fig. 6C), revealing that while WT mice exhibit an increase in Tb 24 h after inoculation, mice lacking intact PGE2-EP3 circuitry had a non-significant tendency towards hypothermia at the same time point. By 48 h Tb values were similar in surviving animals from both groups (not shown).

EP3−/− mice are protected from death following systemic endotoxin exposure

To determine whether the beneficial effects of EP3 receptor deletion on mortality were limited to live infection or might be true in the face of overwhelming, non-infectious inflammation, mice were injected i.p. with sterile LPS (10 mg/kg). As demonstrated in Fig. 7A, ablation of PGE2-EP3 signaling dramatically improved animal survival in the face of severe endotoxin exposure. Consistent with previous reports (20), EP3−/− mice did not generate a fever after LPS exposure (not shown).

Figure 7.

Deletion of EP3 confers protection against endotoxin-induced death and inflammation. (A) Wild type (WT) or EP3 knockout (KO) mice were injected i.p. with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 mg/kg) as detailed in Materials and Methods. Survival was assessed over time. (B) Evans blue dye extravasation was determined 6 hr after LPS injection in WT and KO mice in the lungs and kidney as outlined in the text. (C and D) Cytokine and chemokine levels were determined in the blood (C) and peritoneal fluid (D) by ELISA 5 hr after i.p. LPS injection in WT and KO mice as described in Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05 compared to WT level.

The inflammatory response to LPS exposure is blunted in EP3−/− mice

Whereas significant differences in inflammatory mediators were not observed between EP3−/− and WT mice during a local bacterial infection, it was unknown whether such differences might become evident (and significant) in an acute systemic inflammatory insult such as i.p. LPS injection. Notably, the mean serum concentration of TNF-α was significantly lower in the EP3−/− mice 5 hr after LPS exposure compared to the EP3+/+ mice, with mean (± SEM) values of 326.6 ± 47.4 pg/ml vs. 518.4 ± 60.8 pg/ml, respectively (P < 0.05; n=10 mice per group; Fig. 7C). There were non-significant trends towards lower levels of several other mediators in the KO animals (Fig. 7C). When the same mediators were compared in the peritoneal cavity of LPS-injected mice (Fig. 7D) no significant differences were observed between mice having the EP3 receptor or not.

When serum was examined at an earlier time point (2 hr after LPS injection), we observed significantly lower levels of TNF-α in the EP3−/− (497.0 ± 20.1 pg/ml) vs EP3+/+ animals (1,363 ± 206.0 pg/ml; P < 0.01); lower levels of IL-1β in the EP3−/− (134.3 ± 6.6 pg/ml) vs EP3+/+ animals (182.5 ± 14.3 pg/ml; P < 0.05); and lower levels of IL-10 in the EP3−/− (275.0 ± 30.3 pg/ml) vs EP3+/+ animals (696 ± 123.0 pg/ml; P < 0.05; n=5 mice per group; data not shown). Other mediators were not different in the serum and no mediators significantly differed between the two mouse strains when measured in the peritoneal fluid (data not shown).

Vascular permeability during LPS-induced shock is not influenced by the EP3 receptor

The enhanced survival observed in EP3 null mice in the face of overwhelming inflammatory insult with high dose LPS suggests a possible role for the EP3 receptor in regulating the vascular leak observed in this setting. To test this, EP3+/+ and EP3−/− mice were administered LPS (10 mg/kg i.p.) and the extravasation of Evans blue dye was measured in the lungs and kidneys 6 h later as a surrogate marker of vascular leak (Fig. 7B). No differences between genotypes were observed.

Discussion

The lipid mediator PGE2 has been implicated in the regulation of both innate and adaptive responses to microbial invasion (7, 39, 40). The diverse immunoregulatory effects of PGE2 result in part from the presence of four specific G protein-coupled receptors that signal in distinct fashions on a range of immune effector cells. Most studies of PGE2 immune regulation have focused on the two receptors that primarily alter cell function through increases in cAMP concentration, namely EP2 and EP4. As a ubiquitous second messenger, cAMP has been extensively characterized for its capacity to blunt immune responses and suppress host defenses against infection (41). Less is known about the remaining two EP receptors, the Gαq-coupled EP1 and the Gαi-coupled EP3 in regard to the regulation of immune defense systems.

The present studies represent the first attempt, to our knowledge, to identify a role for the EP3 receptor in the regulation of host-bacterial interactions in vivo. Because the EP3 receptor predominantly signals through the Gαi protein-coupled inhibition of adenylate cyclase (19), we questioned whether the ablation of EP3 signaling would unmask EP2- and/or EP4-dependent immunosuppressive mechanisms, resulting in a worse outcome for infected EP3−/− mice. The unexpected answer to this question, under the conditions of our murine pneumonia model, was no. Instead, EP3 receptor deletion protected mice against death from either infectious or non-infectious inflammatory insults.

The enhanced survival observed in the EP3−/− mice correlated with several potentially important differences in physiological and immune parameters. These included enhanced pulmonary clearance of bacteria with improved alveolar macrophage phagocytic and bactericidal capacities; reduced accumulation of lung neutrophils; lower numbers of circulating blood leukocytes; and an impaired febrile response to infection. It is speculative that a combination of effects such as these promoted the recovery of EP3 null animals in the face of severe bacterial infection.

A striking finding was the influence of EP3 signaling on alveolar macrophage-pneumococcal interactions. The impact of the observed increase in phagocytic capacity of the knockout macrophages (~10% greater than WT cells) might be irrelevant. However, this effect is amplified by a nearly 60% better killing capacity in the null macrophages (Figs. 2E and F). These actions likely contributed to the enhanced pulmonary bacterial clearance observed in vivo.

The observation that EP3 signaling in macrophages significantly limits bacterial killing is novel. To identify potential intracellular targets of EP3 signaling involved in this effect we investigated two important bactericidal mechanisms: the generation of ROIs and NO by activated macrophages. Both ROIs (8, 42) and NO have been implicated in controlling S. pneumoniae infection (43, 44).

Through EP2- and EP4-mediated increases in cAMP, PGE2 prevents the activation of the ROI-generating enzyme NADPH oxidase complex in alveolar macrophages (15), an effect noted previously in a Gram-negative infection model (15). Studies were conducted to identify an influence of the EP3 receptor on alveolar macrophage ROI generation in response to pneumococcal challenge but no effect was revealed (Fig. 3A). In addition, exogenously-added PGE2 (1 μM) inhibited ROI generation equally well in both EP3+/+ and EP3−/− cells when challenged with S. pneumoniae (data not shown).

To compare the capacities of WT and EP3 null alveolar macrophages to generate reactive nitrogen species we measured NO in response to immune stimulation using IFN-γ and the Gram positive bacterial cell wall component lipoteichoic acid, both potent stimulators of macrophage NO (45). We made the novel observation that cells lacking EP3 receptor generated significantly more NO than did WT cells in response to immune stimulation (Fig. 3B). We similarly observed significantly more NO production by EP3−/− alveolar macrophages in response to either LPS plus IFN-γ or IFN-γ alone (data not shown). Future studies are needed to define the mechanisms responsible for the negative influence of EP3 signaling on NO generation. It is notable that PGE2, through cAMP-dependent signaling, has been shown to enhance the expression of the inducible NO synthase enzyme in macrophages (46), suggesting that un-checked EP2 and/or EP4 signaling (through cAMP) might be responsible for the present findings.

The fact that EP3 null mice exhibited better survival in both infectious (S. pneumoniae) and non-infectious (LPS) models suggests a common underlying mechanism. The reduction in lung MPO levels in the pneumonia model (likely owing to enhanced clearance of bacteria from the lungs) and in serum IL-1β and TNF-α levels in the LPS model suggests the possibility that enhanced survival in these animals reflects reduced local and systemic inflammation. Our in vitro findings imply that the EP3-dependent suppression of nitric oxide signaling cascades might contribute to poor outcome in the setting of overwhelming inflammation or infection. This is an area now deserving greater attention in future studies.

We sought to define normal physiological responses governed by PGE2-EP3 signaling that limit survival during systemic inflammation. The present studies failed to identify differences in vascular leak between LPS-exposed WT and receptor deficient animals. PGE2 is involved in mediating physiological responses to disease, including anorexia/cachexia (47) and fever (20). EP3 knock out did not cause weight loss in infected animals (Fig. 6B). The EP3 receptor is firmly established as an important mediator of fever in response to inflammatory insults, particularly in mice (48), a consequence of EP3 signaling on neurons within the thermoregulatory centers of the hypothalamus (49). We found that during pneumococcal infection WT mice mounted an increase in Tb that was not observed in EP3−/− mice, which instead showed a tendency towards hypothermia after infection. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the febrile response in EP3−/− mice to infection rather than merely sterile, inflammatory stimuli such as LPS or cytokines. Fever is generally believed to be a beneficial response that has evolved because it facilitates defense against microbial pathogens (50). Thus, it might seem paradoxical that EP3−/− mice would have a survival advantage as a consequence of impaired thermoregulation. However, the proinflammatory effects of fever have also been implicated in driving maladaptive (i.e. lethal) responses such as enhanced energy expenditure in the setting of severe pneumonia (51). Whether a lack of fever in EP3 receptor null mice is causally related to their enhanced survival in the face of bacterial pneumonia or i.p. endotoxin injection cannot be answered from our studies.

The systemic inflammatory response to a major inflammatory insult, such as LPS injection, involves the synthesis and release of diverse inflammatory mediators (lipids, cytokines, and chemokines) into the systemic circulation (52, 53). While the EP3 receptor has not been implicated in the control of inflammatory mediator release in this setting, EP3 activation was found to regulate IL-6 production in a rat model of arthritis (54). The present results suggest that EP3 regulates systemic inflammation as well (Fig. 7C and data not shown). Whether there are direct effects of EP3 receptor activation on inflammatory mediator-producing cells (such as leukocytes), or the effects are indirect, remains unanswered.

In summary, these studies provide new insights into the physiological and pathophysiological role of PGE2 and the EP3 receptor in the setting of severe bacterial pneumonia and overwhelming inflammation. We observed protection of EP3−/− mice from lethal bacterial pneumonia and this was associated with enhanced clearance of bacteria from the lungs, reduced circulating leukocyte numbers with depressed pulmonary neutrophil recruitment; improved bacterial phagocytosis and killing by macrophages in the alveolar space; enhanced production of NO by these macrophages; and the suppression of normal thermoregulatory responses. Similar protection from death was observed in an LPS model of sepsis and this was associated with reduced systemic inflammatory responses. Future studies to better characterize the mechanisms underpinning these new observations are warranted. Pharmacological targeting of the PGE2-EP3 axis represents a novel area warranting greater investigative interest in the prevention and/or treatment of infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the NIH grants HL078727, HL077417, HL058897.

Nonstandard abbreviations

- AM

alveolar macrophage

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- EP

E-prostanoid

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- i.t

intra-tracheally

- i.p

intra-peritoneally

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NO

nitric oxide

- PG

prostaglandin

- PI

phagocytic index

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocytes

- ROI

reactive oxygen intermediate

References

- 1.Statistics, N. C. f. H; U. S. D. o. H. a. H. Services, editor. Health, United States, 2007, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. U.S. Government Printing Office; Hyattsville, MD: 2007. p. 567. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Jr, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine OS, O’Brien KL, Knoll M, Adegbola RA, Black S, Cherian T, Dagan R, Goldblatt D, Grange A, Greenwood B, Hennessy T, Klugman KP, Madhi SA, Mulholland K, Nohynek H, Santosham M, Saha SK, Scott JA, Sow S, Whitney CG, Cutts F. Pneumococcal vaccination in developing countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1880–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68703-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadioglu A, Andrew PW. The innate immune response to pneumococcal lung infection: the untold story. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronoff DM, Canetti C, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits alveolar macrophage phagocytosis through an E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in intracellular cyclic AMP. J Immunol. 2004;173:559–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballinger MN, Aronoff DM, McMillan TR, Cooke KR, Olkiewicz K, Toews GB, Peters-Golden M, Moore BB. Critical role of prostaglandin E2 overproduction in impaired pulmonary host response following bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. 2006;177:5499–5508. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadikot RT, Zeng H, Azim AC, Joo M, Dey SK, Breyer RM, Peebles RS, Blackwell TS, Christman JW. Bacterial clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is enhanced by the inhibition of COX-2. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1001–1009. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu A, Aronoff DM, Phipps J, Goel D, Mancuso P. Leptin improves pulmonary bacterial clearance and survival in ob/ob mice during pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:332–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romanovsky AA, Almeida MC, Aronoff DM, Ivanov AI, Konsman JP, Steiner AA, Turek VF. Fever and hypothermia in systemic inflammation: recent discoveries and revisions. Front Biosci. 2005;10:2193–2216. doi: 10.2741/1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilley SL, Coffman TM, Koller BH. Mixed messages: modulation of inflammation and immune responses by prostaglandins and thromboxanes. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:15–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI13416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medeiros AI, Serezani CH, Lee SP, Peters-Golden M. Efferocytosis impairs pulmonary macrophage and lung antibacterial function via PGE2/EP2 signaling. J Exp Med. 2009;206:61–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheibanie AF, Yen JH, Khayrullina T, Emig F, Zhang M, Tuma R, Ganea D. The proinflammatory effect of prostaglandin E2 in experimental inflammatory bowel disease is mediated through the IL-23-->IL-17 axis. J Immunol. 2007;178:8138–8147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takayama K, Sukhova GK, Chin MT, Libby P. A novel prostaglandin E receptor 4-associated protein participates in antiinflammatory signaling. Circ Res. 2006;98:499–504. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000204451.88147.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serhan CN, Brain SD, Buckley CD, Gilroy DW, Haslett C, O’Neill LA, Perretti M, Rossi AG, Wallace JL. Resolution of inflammation: state of the art, definitions and terms. FASEB J. 2007;21:325–332. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7227rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serezani CH, Chung J, Ballinger MN, Moore BB, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 Suppresses Bacterial Killing in Alveolar Macrophages by Inhibiting NADPH Oxidase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:562–570. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0153OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronoff DM, Carstens JK, Chen GH, Toews GB, Peters-Golden M. Differences between macrophages and dendritic cells in the cyclic AMP dependent regulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine and chemokine synthesis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:827–833. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breyer RM, Bagdassarian CK, Myers SA, Breyer MD. Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:661–690. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid A, Thierauch KH, Schleuning WD, Dinter H. Splice variants of the human EP3 receptor for prostaglandin E2. Eur J Biochem. 1995;228:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hata AN, Breyer RM. Pharmacology and signaling of prostaglandin receptors: multiple roles in inflammation and immune modulation. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;103:147–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ushikubi F, Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Murata T, Matsuoka T, Kobayashi T, Hizaki H, Tuboi K, Katsuyama M, Ichikawa A, Tanaka T, Yoshida N, Narumiya S. Impaired febrile response in mice lacking the prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP3. Nature. 1998;395:281–284. doi: 10.1038/26233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kluger MJ, Kozak W, Conn CA, Leon LR, Soszynski D. The adaptive value of fever. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1996;10:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kluger MJ, Kozak W, Conn CA, Leon LR, Soszynski D. Role of fever in disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;856:224–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailie MB, Standiford TJ, Laichalk LL, Coffey MJ, Strieter R, Peters-Golden M. Leukotriene-deficient mice manifest enhanced lethality from Klebsiella pneumonia in association with decreased alveolar macrophage phagocytic and bactericidal activities. J Immunol. 1996;157:5221–5224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peck R. A one-plate assay for macrophage bactericidal activity. J Immunol Methods. 1985;82:131–140. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serezani CH, Aronoff DM, Jancar S, Mancuso P, Peters-Golden M. Leukotrienes enhance the bactericidal activity of alveolar macrophages against Klebsiella pneumoniae through the activation of NADPH oxidase. Blood. 2005;106:1067–1075. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mancuso P, Standiford TJ, Marshall T, Peters-Golden M. 5-Lipoxygenase reaction products modulate alveolar macrophage phagocytosis of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5140–5146. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5140-5146.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sexton E, Van Themsche C, LeBlanc K, Parent S, Lemoine P, Asselin E. Resveratrol interferes with AKT activity and triggers apoptosis in human uterine cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arredouani MS, Yang Z, Imrich A, Ning Y, Qin G, Kobzik L. The macrophage scavenger receptor SR-AI/II and lung defense against pneumococci and particles. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:474–478. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0128OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mancuso P, Gottschalk A, Phare SM, Peters-Golden M, Lukacs NW, Huffnagle GB. Leptin-deficient mice exhibit impaired host defense in Gram-negative pneumonia. J Immunol. 2002;168:4018–4024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrero ME. In vivo vascular leakage assay. Methods Mol Med. 2004;98:191–198. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-771-8:191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng L, An S, Goetzl EJ. Independent down-regulation of EP2 and EP3 subtypes of the prostaglandin E2 receptors on U937 human monocytic cells. Immunology. 1995;86:620–628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalmar L, Gergely P. Effect of prostaglandins on polymorphonuclear leukocyte motility. Immunopharmacology. 1983;6:167–175. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(83)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki K, Araki H, Mizoguchi H, Furukawa O, Takeuchi K. Prostaglandin E inhibits indomethacin-induced gastric lesions through EP-1 receptors. Digestion. 2001;63:92–101. doi: 10.1159/000051876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dockrell DH, Marriott HM, Prince LR, Ridger VC, Ince PG, Hellewell PG, Whyte MK. Alveolar macrophage apoptosis contributes to pneumococcal clearance in a resolving model of pulmonary infection. J Immunol. 2003;171:5380–5388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knapp S, Leemans JC, Florquin S, Branger J, Maris NA, Pater J, van Rooijen N, van der Poll T. Alveolar macrophages have a protective antiinflammatory role during murine pneumococcal pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:171–179. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-698OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakamoto A, Matsumura J, Mii S, Gotoh Y, Ogawa R. A prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP4 agonist attenuates cardiovascular depression in endotoxin shock by inhibiting inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide production. Shock (Augusta, Ga. 2004;22:76–81. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000129338.99410.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ratcliffe MJ, Walding A, Shelton PA, Flaherty A, Dougall IG. Activation of E-prostanoid4 and E-prostanoid2 receptors inhibits TNF-alpha release from human alveolar macrophages. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:986–994. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00131606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldmann O, Chhatwal GS, Medina E. Immune mechanisms underlying host susceptibility to infection with group A streptococci. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:854–861. doi: 10.1086/368390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Son Y, Ito T, Ozaki Y, Tanijiri T, Yokoi T, Nakamura K, Takebayashi M, Amakawa R, Fukuhara S. Prostaglandin E2 is a negative regulator on human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunology. 2006;119:36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woolard MD, Hensley LL, Kawula TH, Frelinger JA. Respiratory Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain infection induces Th17 cells and prostaglandin E2, which inhibits generation of gamma interferon-positive T cells. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2651–2659. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01412-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serezani CH, Ballinger MN, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M. Cyclic AMP: Master Regulator of Innate Immune Cell Function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:127–132. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0091TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pitt J, Bernheimer HP. Role of peroxide in phagocytic killing of pneumococci. Infect Immun. 1974;9:48–52. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.1.48-52.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerr AR, Wei XQ, Andrew PW, Mitchell TJ. Nitric oxide exerts distinct effects in local and systemic infections with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Pathog. 2004;36:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marriott HM, Ali F, Read RC, Mitchell TJ, Whyte MK, Dockrell DH. Nitric oxide levels regulate macrophage commitment to apoptosis or necrosis during pneumococcal infection. FASEB J. 2004;18:1126–1128. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1450fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hattor Y, Kasai K, Akimoto K, Thiemermann C. Induction of NO synthesis by lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus in J774 macrophages: involvement of a CD14-dependent pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:375–379. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang YC, Li PC, Chen BC, Chang MS, Wang JL, Chiu WT, Lin CH. Lipoteichoic acid-induced nitric oxide synthase expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages is mediated by cyclooxygenase-2, prostaglandin E2, protein kinase A, p38 MAPK, and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1235–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang W, Andersson M, Lonnroth C, Svanberg E, Lundholm K. Anorexia and cachexia in prostaglandin EP1 and EP3 subtype receptor knockout mice bearing a tumor with high intrinsic PGE2 production and prostaglandin related cachexia. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2005;24:99–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuoka T, Narumiya S. The roles of prostanoids in infection and sickness behaviors. J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:270–278. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0622-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blatteis CM. The onset of fever: new insights into its mechanism. Prog Brain Res. 2007;162:3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)62001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aronoff DM, Neilson EG. Antipyretics: mechanisms of action and clinical use in fever suppression. Am J Med. 2001;111:304–315. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00834-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rice P, Martin E, He JR, Frank M, DeTolla L, Hester L, O’Neill T, Manka C, Benjamin I, Nagarsekar A, Singh I, Hasday JD. Febrile-range hyperthermia augments neutrophil accumulation and enhances lung injury in experimental gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. J Immunol. 2005;174:3676–3685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ball HA, Cook JA, Wise WC, Halushka PV. Role of thromboxane, prostaglandins and leukotrienes in endotoxic and septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 1986;12:116–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00254925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okazaki K, Kondo M, Kato M, Nishida A, Takahashi H, Noda M, Kimura H. Temporal alterations in concentrations of sera cytokines/chemokines in sepsis due to group B streptococcus infection in a neonate. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008;61:382–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kurihara Y, Endo H, Kondo H. Induction of IL-6 via the EP3 subtype of prostaglandin E receptor in rat adjuvant-arthritic synovial cells. Inflamm Res. 2001;50:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s000110050716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]