Abstract

Purpose

To enable high-quality correction of susceptibility-induced geometric distortion artifacts in diffusion MRI images without increasing scan time.

Theory and Methods

A new method for distortion correction is proposed based on subsampling a generalized version of the state-of-the-art reversed-gradient distortion correction method. Rather than acquire each q-space sample multiple times with different distortions (as in the conventional reversed-gradient method), we sample each q-space point once with an interlaced sampling scheme that measures different distortions at different q-space locations. Distortion correction is achieved using a novel constrained reconstruction formulation that leverages the smoothness of diffusion data in q-space.

Results

The effectiveness of the proposed method is demonstrated with simulated and in vivo diffusion MRI data. The proposed method is substantially faster than the reversed-gradient method, and can also provide smaller intensity errors in the corrected images and smaller errors in derived quantitative diffusion parameters.

Conclusion

The proposed method enables state-of-the-art distortion correction performance without increasing data acquisition time.

Keywords: Diffusion MRI, Distortion correction, Echo-Planar Imaging, B0-Field inhomogeneity, Interlaced q-space sampling, Constrained reconstruction

INTRODUCTION

Diffusion MRI provides quantitative information about tissue microstructure that is not available through any other noninvasive imaging technology, and is routinely used in a wide variety of clinical and neuro-science applications (1–3). Quantitative diffusion MRI experiments acquire multiple Diffusion Weighted Images (DWIs) corresponding to different q-space samples. These DWIs are typically acquired using fast pulse sequences like Echo-Planar Imaging (EPI) to reduce acquisition time and minimize certain motion artifacts. However, EPI is sensitive to B0 inhomogeneities because of low bandwidth along the phase encoding direction (PED). This leads to geometric distortion in reconstructed EPI images, which is particularly strong near interfaces between soft tissue and air or bone (4). In brain imaging, this leads to distortions that are particularly severe near the frontal sinuses and in the temporal lobes. Geometric image distortions can confound interpretation of the data and limit the accuracy of multimodal image analyses (5,6).

Multiple methods have been proposed to correct distortion in EPI images. One common approach uses a measured B0 fieldmap to model the geometric warping observed in the EPI images, and generates a corresponding unwarping transform which is used to correct the distortions (7). This approach, which we will refer to as the ‘single-PED method,’ is widely used, but can be inaccurate in areas of substantial distortion (5).

There are two typical ways that severe geometric distortion artifacts manifest in EPI images: signal pile-up and signal stretching (7). Signal pile-up occurs when signal from multiple spatial locations is erroneously mapped to the same spatial location. On the other hand, signal stretching occurs when signal that should be mapped to one voxel is spread across multiple voxels. Of these two, stretching is a one-to-many mapping that is relatively easy to correct, while pile-up correction is an ill-posed many-to-one mapping that is very difficult to correct using the single-PED method (5,8). Distorted EPI brain images often contain both pile-up and stretching artifacts simultaneously in different image regions (7).

In EPI, geometric distortions occur primarily along the PED (7), and a pile-up artifact can be converted into a stretching artifact (and vice versa) by reversing the PED (9, 10)1. The previously proposed reversed-gradient (RG) method (9–13) uses this fact to substantially improve distortion correction relative to the single-PED method. The RG method acquires two DWIs for each q-space sample, each with a different PED so that they have opposite distortion characteristics. The complementary information from these two images allows substantially better distortion correction than the single-PED method (5,9,11). However, the main limitation of the RG method is that it requires twice as many images, which increases the total scan time by a factor of two. This increased acquisition time can be prohibitive in many applications. Figure 1 illustrates typical results obtained by applying the RG and single-PED methods to an image from an EPI diffusion experiment. Note that the RG method yields corrected images with more uniform image intensity and better geometric fidelity to the undistorted anatomical reference.

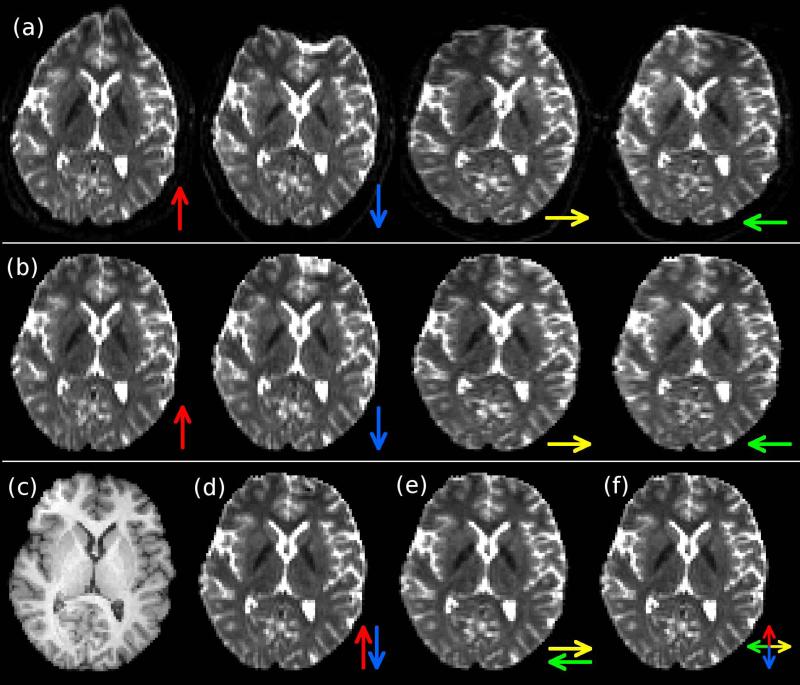

Figure 1.

Overview of susceptibility-induced EPI distortion with single-PED and RG correction methods. (a) The same axial b=0 s/mm2 brain image acquired with different EPI PEDs (represented by colored arrows). Note the presence of substantial geometric distortion, particularly in the frontal lobe. (b) Distortion-corrected images using the single-PED method. (c) Undistorted anatomical MPRAGE image for reference. Distortion-corrected images using the RG method are shown based on PEDs along the (d) A/P direction and (e) L/R direction. (f) Generalized RG distortion correction using all four PEDs (‘4-PED Full’).

This work proposes a new accelerated strategy for distortion correction which, similar to the RG method, uses information from multiple PEDs to improve the performance of distortion correction. However, unlike the RG method, the proposed approach does not require each q-space sample to be acquired multiple times. Instead, we propose to acquire each q-space sample once, using an interlaced sampling scheme that uses different PEDs for different q-space samples. This kind of subsampling is possible because neighboring q-space samples share a substantial amount of information, meaning that there is redundancy in the RG dataset if the distortion correction problem is formulated in an appropriate way. In the proposed approach, the acquired PED-interlaced DWIs are corrected for distortion using a constrained joint-reconstruction method that exploits the smoothness of diffusion data in q-space. Our results with simulated and experimental data suggest that the proposed method yields substantially better performance than the single-PED method, and can offer similar performance to the RG method while using only half the scan time.

THEORY

In the traditional RG method, distortion correction is performed independently for each q-space sample (10,11). As a result, it is necessary to acquire each point in q-space with two different PEDs. Our proposed method is based on the observation that nearby q-space samples are generally related to each other, and share a substantial amount of structure. This conceptual breakthrough allows for distortion correction of different DWIs to be performed jointly, which can substantially reduce the amount of data needed for high-quality results.

A variety of different dependencies have been previously observed between the DWIs for different q-space samples. For example, it has been observed that image edge locations are highly correlated between different DWIs (see (14) and its references), and that DWIs possess approximately low-rank structure (see (15) and its references). For simplicity, we will not focus on these kinds of constraints in this work, though note that they are potentially powerful in this context. Another constraint, which we use extensively in the proposed method, is that the diffusion signal is generally smooth in q-space. This smoothness assumption is frequently used in high angular resolution diffusion imaging (HARDI) modeling (16–18), and is implicit in most of the parametric models of the diffusion signal like Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) (1–3).

Based on the assumption of q-space smoothness, our proposed method acquires different q-space samples with different PEDs in an interlaced manner: each q-space location is only measured once, and PEDs are assigned to each q-space location so that neighboring q-space samples have different PEDs. In addition, we construct the sampling pattern so that the samples associated with each unique PED are distributed as evenly as possible in q-space. Examples of our interlaced PED (IPED) q-space sampling scheme are shown in Fig. 2. By acquiring the data in an interlaced fashion, we do not require any additional scan time, but still obtain information from DWIs with similar contrasts that have been distorted in different ways. Note that unlike the RG method, which always uses 2 PEDs, we do not place any restrictions on the number of distinct PEDs that are used in the acquisition (though, for simplicity, the examples we present either use 2 or 4 PEDs). We will respectively refer to IPED data acquired with 2 and 4 PEDs as ‘2-IPED’ and ‘4-IPED’ data in the rest of the paper.

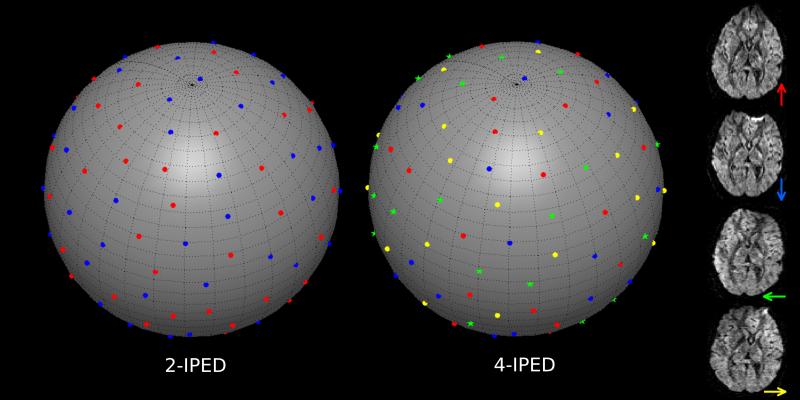

Figure 2.

2-IPED and 4-IPED examples of our proposed q-space sampling scheme assuming that data is sampled at 64 points on a sphere (i.e., a single b-value). Each q-space sample is shown as a dot on the surface of the sphere, where the color of each dot represents the PED for that particular diffusion encoding. The rightmost column of images shows how the different colors are mapped to different PEDs (represented by colored arrows).

To enable distortion correction with our IPED q-space sampling scheme, we represent the geometric distortion process as a linear operator on an undistorted image, and formulate distortion correction as a regularized least-squares problem. In particular, assuming that each DWI has V voxels, that there are Q-different DWIs, and that we have an estimate of the B0 fieldmap, we obtain distortion-corrected images by solving:

| [1] |

where and are respectively the measured distorted image and the corresponding unknown distortion-free image for the qth sample in q-space, Dq is the corresponding V × V geometric distortion operator (a function of the PED for the qth DWI and the measured fieldmap), and R(·) is a regularization penalty function that stabilizes the distortion correction procedure by enforcing additional constraints. Similar formulations for EPI distortion correction based on least-squares approaches have previously been explored (8,11), though these did not incorporate joint reconstruction of different q-space samples, regularization, or multiple PEDs.

Careful choice of the function R(·) is essential, since the use of IPED sampling was predicated on leveraging the shared structure between different q-space samples, and regularization is the only mechanism in our formulation for imposing shared structure. Note that without regularization in Eq. [1], the distortion correction of different q-space samples is completely decoupled when using IPED sampling. As already described, distortion correction of a single DWI from a single-PED dataset can be ill-posed.

The proposed formulation in Eq. [1] is quite general, and can be adapted to arbitrary q-space sampling schemes through the choice of an appropriate R(·) function that couples together the distortion correction of different q-space samples. However, the choice of R(·) must also be compatible with the q-space sampling pattern. For simplicity, we will assume in this paper that diffusion data is sampled on the surface of a sphere in q-space (i.e., a conventional single-shell acquisition with multiple diffusion encoding directions and a single b-value), and that the q-space signal varies smoothly on the surface of the sphere. Based on this assumption, we will adopt the Laplace-Beltrami q-space smoothness regularization penalty that is commonly used for this kind of data when estimating HARDI signals (16–18). Similar to previous approaches, we implement the Laplace-Beltrami operator in a computationally-efficient manner by using a representation of the DWIs in the spherical harmonic (SH) basis. In particular, we assume that the V × Q image matrix S = [s1, · · · , sQ] is represented as S = CY, where C is a V × N matrix whose vth row contains the N different SH coefficients (truncated at a predetermined user-chosen SH order (16–18)) for the vth voxel, and Y is the N × Q matrix whose rows are computed by sampling the SH basis functions along each of the Q different diffusion encoding directions. In order to further stabilize the distortion correction procedure, we also encourage the spatial smoothness of each DWI. Combining the SH representation with Laplace-Beltrami (spherical) q-space smoothness and spatial smoothness penalties, we arrive at our proposed optimization formulation:

| [2] |

and then obtaining Ŝ by setting Ŝ = ĈY. In Eq. [2], cv is the transpose of the vth row of C, L is a diagonal matrix that applies the Laplace-Beltrami operator to SH coefficients (16–18), F is a first-order finite difference matrix of size 2V × V, that computes the horizontal and vertical spatial image derivatives at each image voxel, and αv and β are scalar regularization parameters that respectively control the strength of the spherical and spatial smoothness constraints. See Appendix A for more specific details about the SH representation, the Laplace-Beltrami operator, and the associated matrix definitions that are used in Eq. [2].

Equation [2] is quite similar in structure to a variety of different constrained image reconstruction methods (e.g., (14) and its references), and reduces to a simple linear least squares problem (shown in Appendix B) that can be solved using standard iterative least squares algorithms. Despite the relatively large scale of the optimization problem, computationally-efficient implementations can be obtained by using sparse matrix representations that enable fast matrix-vector multiplications (note that D, L, and F are all sparse). We solved all linear least squares problems in this paper using the iterative LSQR algorithm (19) in MATLAB 7.14 (The MathWorks, Inc., USA).

In practice, the regularization parameters αv and β must be chosen appropriately to achieve good performance. Small values of αv will only weakly impose coupling between different DWIs in the distortion correction procedure, which could lead to performance that is more similar to single-PED distortion correction than to the RG method. On the other hand, excessively large values of αv will lead to a bias towards isotropic diffusion characteristics. It should be noted that we are allowing αv to vary as a function of spatial location, since the coupling between different DWIs will be more critical in spatial image regions that are more highly distorted. Similarly, small values of β can cause the reconstructed DWIs to be more sensitive to noise, while excessively large values of β can lead to substantial loss of spatial resolution. Spatially-varying choices of β can also be used to achieve additional performance benefits (14), though for simplicity, we will use a spatially-invariant β in this work.

METHODS

Simulation Data

To evaluate the proposed method, we simulated a 20-direction diffusion MRI dataset acquired with a single-shot EPI readout for two different levels of geometric distortion. Small and large distortions were generated by simulating a fully-sampled 128 × 128 EPI trajectory (without any parallel imaging) with echo spacings of 0.35ms and 0.55ms, respectively. The echo spacings used in our simulation are similar to typical ‘effective’ echo spacings for in vivo acquisitions. We used distortion-corrected experimental human brain data (TE=88s, TR=10000ms, b=1000 s/mm2, 2mm isotropic resolution) as a ground truth for the simulation. The ground truth for the simulation was specifically constructed based on 10 contiguous DWI slices from a brain region with minimal B0 field inhomogeneity, to ensure that the ground truth had negligible geometric distortion artifacts. To yield even better geometric accuracy, these images were also corrected using a data sampling and distortion correction scheme we refer to as ‘4-PED Full’. Specifically, 4-PED Full samples each q-space sample 4 times with 4 different PEDs which encodes the highly distorted image regions even more comprehensively than the RG method. Note that 4-PED Full uses twice as many images as the RG method, and four times as many as the single-PED schemes. Distorted images were simulated based on the ground truth images using a B0 fieldmap acquired on a 3T scanner from a different subject (fieldmap values ranged from approximately -75 Hz to 130 Hz, leading to maximum signal displacements of approximately 11 mm and 18 mm for the small and large distortion simulated datasets, respectively) and a least-squares time segmentation approach to model the effects of field inhomogeneity on measured k-space data (20–22).

Simulated data was generated for each of the four different PEDs shown in Fig. 1, for a total of 80 simulated DWIs. Acquisitions corresponding to single-PED, RG, 2-IPED, 4-IPED, and 4-PED Full sampling schemes were constructed by subsampling this data (80 DWIs for 4-PED Full, 40 DWIs for the RG acquisition, and 20 DWIs for the single-PED, 2-IPED, and 4-IPED acquisitions). Note that while 4-PED Full distortion correction was used for the construction of the ground truth images for the simulation, we used a distinct distortion model to generate the simulated distorted images. Specifically, the simulated distorted images were constructed using a distinct fieldmap with larger inhomogeneity, and distortion was simulated in k-space rather than image space. As a result, the simulation would not be expected to be biased toward 4-PED Full reconstruction, and 4-PED Full reconstruction of the simulated data would not be expected to be perfect.

PEDs for each of the 20 DWIs in the interlaced acquisitions were assigned to achieve a fairly even distribution in q-space by using a variation of the electrostatic repulsion method for distributing q-space samples evenly on the sphere (23). In particular, we first used electrostatic repulsion to distribute the 20 q-space samples evenly on the sphere. Subsequently, keeping the q-space sampling locations fixed, we chose PED labels for each q-space location to minimize the electrostatic potential energy for the subsets of q-space samples sharing the same PED. Global optimization of this energy is not computationally tractable, but we obtained reasonable PED distributions using Monte Carlo methods (see Appendix C for the gradient/PED table). Note that our approach has similarities to a recent method developed for designing multi-shell diffusion acquisitions (24), though was derived independently.

In Vivo Data

The proposed method was also evaluated with in vivo data. We acquired a set of 20 DWIs (using the same gradient/PED tables as the simulations) on a 3T scanner (single-shot EPI, 6/8ths partial Fourier, GRAPPA with 2×acceleration, TE=88ms, TR=10000ms, b=1000s/mm2, 60 slices, isotropic 2 mm resolution, 0.85ms echo spacing) for each of four different PEDs. The use of GRAPPA makes the ‘effective’ echo spacing (for distortion modeling) equal to 0.425ms. The b = 0s/mm2 images for the four PEDs were shown in Fig. 1(a). A B0 fieldmap was also estimated from two gradient echo images ( TE=10.0ms and 12.46ms, respectively, with image resolution and FOV matched to the DWI acquisition, and a total acquisition time of approximately 2 minutes).

Similar to the simulation, we subsampled the in vivo DWI dataset to create single-PED, RG, 2-IPED, and 4-IPED datasets. Since the ground truth is unavailable for in vivo data, we used distortion-corrected DWIs based on 4-PED Full data (using our own implementation of a generalized version of the RG method with appropriate modifications to use 4 PEDs instead of only 2) as a reference for comparison. This choice is justified by our simulation results (to be presented later), which quantitatively demonstrate very accurate distortion correction performance when using simulated 4-PED Full data. An example of 4-PED Full correction was shown in Fig. 1(f).

Comparisons

The performance of different distortion correction methods on the simulated and in vivo data was assessed both qualitatively and quantitatively. The distortion correction results were evaluated for accuracy with respect to the ground truth images for the simulated data, while the results were evaluated with respect to 4-PED Full distortion corrected images for the in vivo data (due to the lack of a ground truth in this case).

Quantitative performance was assessed by computing the following error measures between the distortion-corrected images and the ground truth (for simulated data) or 4-PED Full images (for in vivo data): (i) Mean Absolute Error (MAE)2 of the DWI voxel intensities, (ii) log-Euclidean distances (LED) between DTI fits of the diffusion data (25) (see Appendix D for the definition of LED), and (iii) MAE of the fractional anisotropy (FA) values derived from the DTI fit. These three measures each reflect different features of the different distortion correction methods. Since different spatial regions are distorted by different amounts in different spatial locations, we also compared these errors as a function of the relative amount of local image distortion.

We compared results for several different distortion correction schemes. We performed single-PED distortion correction for each of the 4 different PEDs, using our own implementation of the non-iterative unwarping procedure described in Ref. (7), which is not based on regularized least squares optimization. We also performed RG distortion correction with Left-Right (L/R) and Anterior-Posterior (A/P) PEDs (see Fig. 1(d,e)). Our implementation of the RG method is similar to the method described in Ref. (11), except that we used spatial smoothness regularization to improve performance, and used a separate B0 field measurement (instead of estimating the B0 fieldmap directly from the distorted data). In particular, our RG implementation used the data consistency and spatial regularization terms (but no spherical regularization) from Eq. [2], with appropriate modifications to the data consistency term to accommodate two PEDs for each q-space sample. We also used Eq. [2] without spherical regularization to correct distortions in the 4-PED Full data (also used as reference image for comparison for the in vivo data), with similar modifications to the data consistency term to accommodate four PEDs for each q-space sample. For the proposed IPED method, we evaluated the performance with 2-IPED (for both L/R and A/P PEDs) and 4-IPED acquisitions. Regularization parameters, when not specified, were chosen empirically for each method and dataset (to minimize the MAE of the DWI voxel intensities) to ensure a fair comparison.

In most of our results (and unless specified otherwise), the regularization parameters αv in Eq. [2] were chosen heuristically to be larger in spatial regions with more substantial geometric distortion, though we also performed a comparison with spatially-uniform αv. In the spatially-varying case, we chose αv to be a monotonic function of the amount of distortion in each voxel, and used the magnitude of the spatial gradient vector of the B0 fieldmap to quantify the amount of distortion for each voxel. In particular, if Wv is the magnitude of the gradient of B0 at the vth voxel, then we set αv = αΛv, where

| [3] |

The threshold parameters γ and δ were chosen manually to avoid under- and over-regularization, respectively, and were set at approximately γ=1.5Hz/mm and δ=16Hz/mm in our experiments. We evaluated performance for a range of different α and β values.

RESULTS

Qualitative Comparisons

Each of the methods performed similarly on simulated and in vivo data, and while we will present quantitative results in both cases, we will only show qualitative results for in vivo data. A representative qualitative comparison between methods for in vivo data is shown for an axial slice including the frontal lobe in Fig. 3. We observe that the single-PED method performs poorly compared to the other approaches, and has significant errors in the frontal lobe where the distortion was relatively large. As expected, the RG method performs substantially better and recovers the structure in the frontal lobe quite accurately. Our proposed interlaced methods (both 2-IPED and 4-IPED) perform similarly to the RG method, with the 4-IPED images actually demonstrating better performance than the RG method. This enhanced performance is notable, given the fact that the RG method used twice as many DWIs and would require twice the scan time as the 4-IPED approach. Maximum intensity projection (MIP) images of whole-brain DWI intensity and FA error maps are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively, and have features that are similar to those observed in the single-slice comparison.

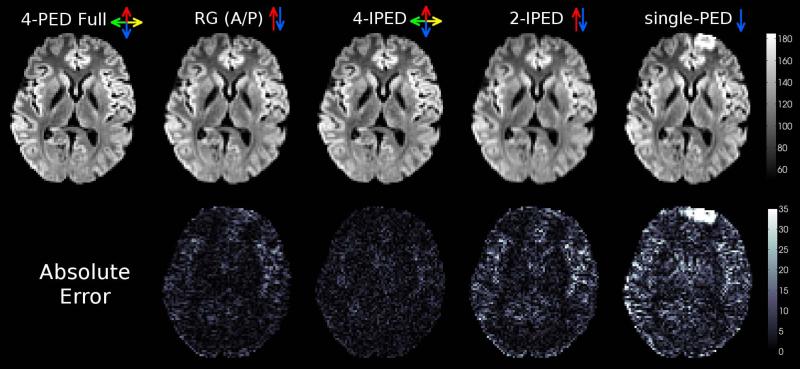

Figure 3.

Representative comparison of applying different distortion correction methods to in vivo data. (top) The average of all distortion-corrected DWIs from the same axial slice shown in Fig. 1(a). (bottom) Corresponding MAE of the DWI image intensities, with respect to the 4-PED Full images (used as a reference since no ground truth exists for the in vivo data). Colored arrows indicate the PED(s) used for each method.

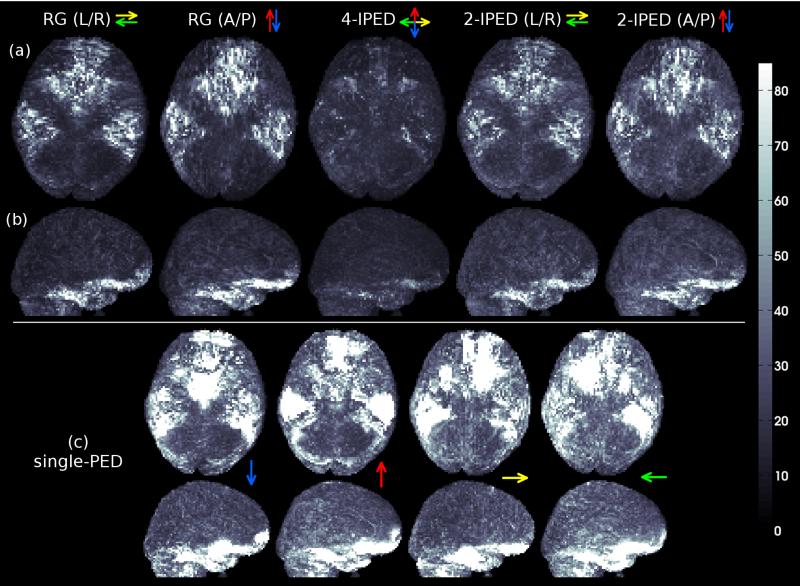

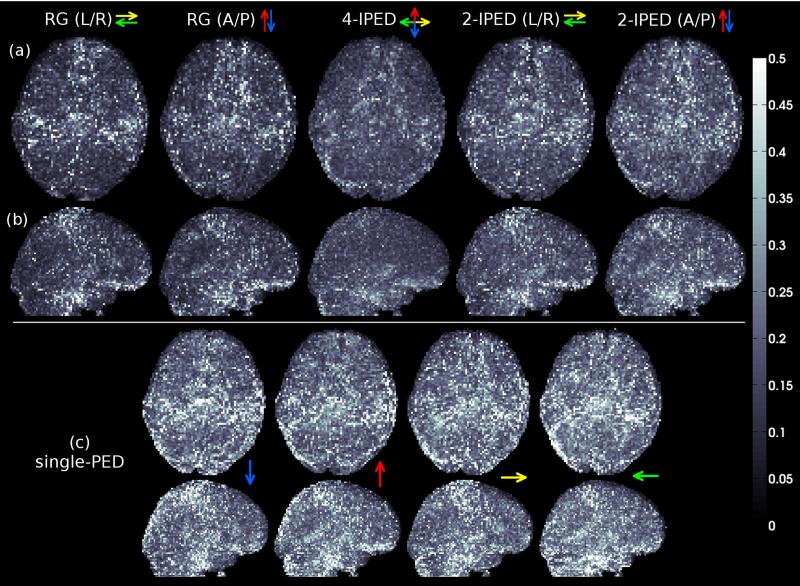

Figure 4.

Whole-brain MIP images of image-intensity error maps computed after applying different distortion correction methods to the in vivo data. (a) Axial MIP images. (b) Sagittal MIP images. (c) Axial and sagittal MIP images for single-PED acquisitions. Colored arrows indicate the PEDs used for each method. Error images are computed using 4-PED Full data as a reference, since there is no ground truth available for in vivo data.

Figure 5.

Whole-brain MIP images of FA error maps computed after applying different distortion correction methods to the in vivo data. (a) Axial MIP images. (b) Sagittal MIP images. (c) Axial and sagittal MIP images for single-PED acquisitions. Colored arrows indicate the PEDs used for each method. Error images are computed using 4-PED Full data as a reference, since there is no ground truth available for in vivo data.

Quantitative Comparisons

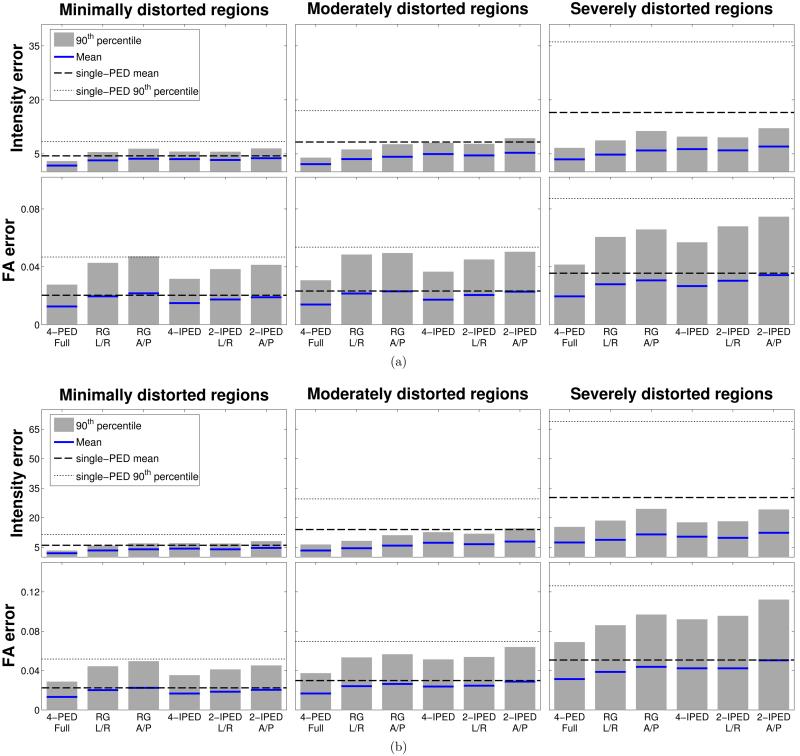

Quantitative performance comparisons are shown in Fig. 6 for the two simulation datasets. The errors are quantified individually for different image regions based on a partition of Wv, noting that increasing values of Wv correspond to increasing levels of local image distortion. We define image regions with minimal, moderate, and severe distortion by finding voxels with Wv values in the ranges of 0-2 Hz/mm, 2-6 Hz/mm, and >6 Hz/mm, respectively. As expected, single-PED data has the worst performance across all error measures, while the 4-PED Full data (which acquires the most data and requires the longest acquisition time) consistently outperforms all other methods for all regions and error measures, and both the RG (L/R) and RG (A/P) methods perform substantially better than the single-PED method. We observe that performance with our proposed interlaced methods was substantially better than with the single-PED methods, and that the 4-IPED acquisition was generally better than the two 2-IPED acquisitions. Notably, the 4-IPED acquisition performed similar to and frequently better than both RG methods, despite using half as much data. It should be noted that the 2-IPED performance was either similar to or slightly worse than for the RG methods, as would be expected since the 2-IPED acquisition uses a subset of the data from the RG method. The 4-IPED acquisition has the capability to improve on the RG method because it measures a more diverse set of PEDs (4 different types of distortion, instead of the 2 different types of distortion that the RG method uses). The spherical regularization in the proposed method makes it possible to use this information for distortion correction without increasing the scan time, and allows 4-IPED acquisition to perform better than the RG method on some error measures. Similar quantitative performance comparisons are shown for the in vivo data in Fig. 7(a), and reflect similar trends.

Figure 6.

Quantitative performance of different methods (measured separately for groups of voxels that experience different amounts of local image distortion) for simulated data with (a) small and (b) large distortion in comparison to the ground truth images. The height of each bar plot shows the 90th percentile of the computed error measure for each region, while the solid blue line shows the mean value of the error measure. The thin and thick dashed lines correspond to the 90th percentile and the mean, respectively, of the error measure in the region for the single-PED methods (all single-PED methods had similar error numbers, and we show the average value of the four).

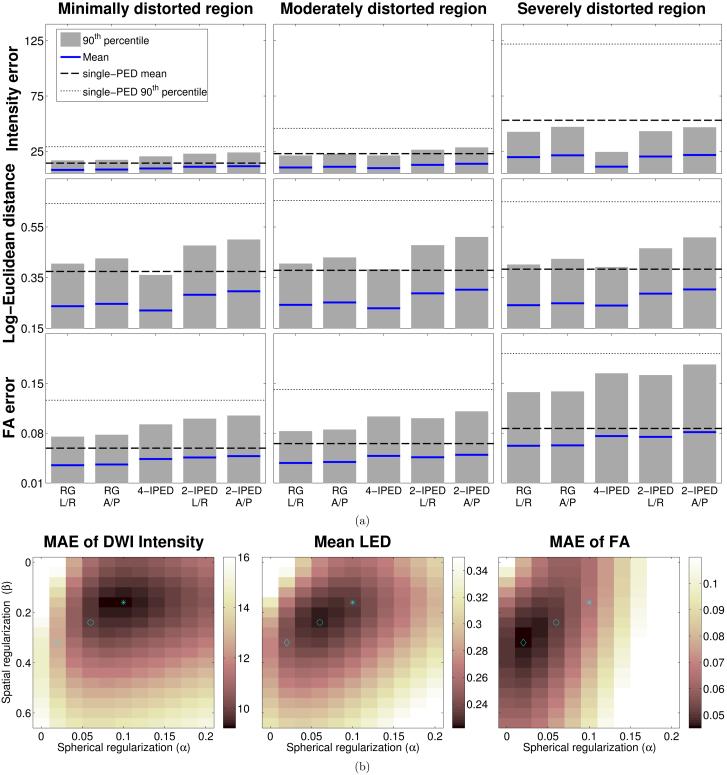

Figure 7.

(a) Quantitative performance of different methods (measured separately for groups of voxels that experience different amounts of local image distortion) for in vivo data, in comparison to the 4-PED Full images which were used as a reference. The height of each bar plot shows the 90th percentile of the computed error measure for each region, while the solid blue line shows the mean value of the error measure. The thin and thick dashed lines correspond to the 90th percentile and the mean, respectively, of the error measure in the region for the single-PED methods (all single-PED methods had similar error numbers, and we show the average value of the four). (b) Mean values of several distortion correction error measures across all voxels as a function of the spherical smoothness (α) and spatial smoothness (β) regularization parameters. Regularization parameters corresponding to minimum error measures are marked by an asterisk (*) for the MAE of DWI Intensity, by a circle (○) for the Mean LED, and by a diamond (◇) for the MAE for FA.

Choice of Regularization Parameters

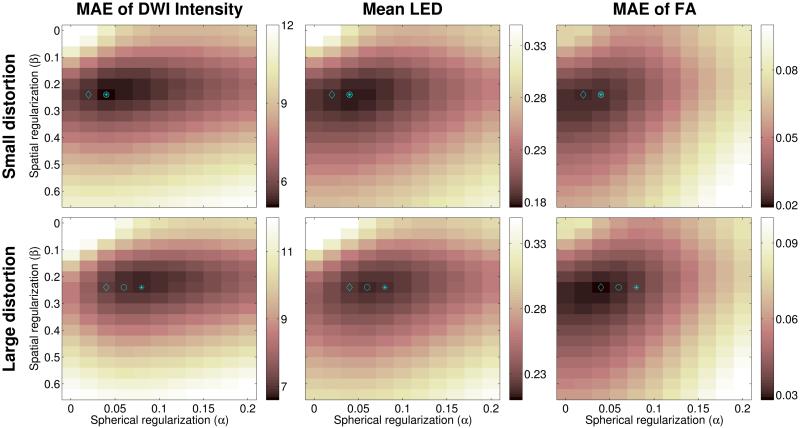

In order to illustrate the impact of the different regularization terms in Eq. [2], we show quantitative error measures when using the 4-IPED acquisition for a range of different choices of α and β for in vivo data (Fig. 7(b)) and the simulations (Fig. 8). We observe that the use of regularization substantially reduces all of the error measures for all of the datasets, and observe that the best performance is obtained when using spatial and spherical regularization together (α ≠ 0 and β ≠ 0). However, as indicated in Fig. 7(b) and Fig. 8, we also observe that the optimal choice of regularization parameters is different for different error measures. This observation is consistent with previous regularized processing of diffusion data (15), and is a reflection of the fact that different estimated diffusion parameters are more or less sensitive to different features of the diffusion data. This suggests that for optimal performance in a given application, the choice of regularization parameters should be tuned based on the subsequent data analysis procedures.

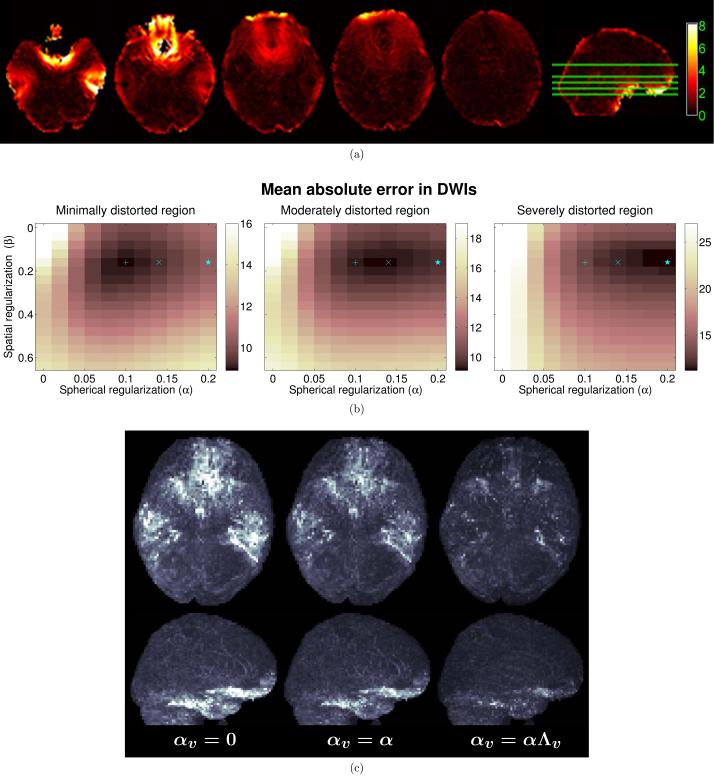

Figure 8.

Mean values of several distortion correction error measures across all voxels as a function of the spherical smoothness (α) and spatial smoothness (β) regularization parameters, computed for (top) the 4-IPED small distortion simulation data and (bottom) the 4-IPED large distortion simulation data in comparison to ground truth images. Regularization parameters corresponding to minimum error measures are marked by an asterisk (*) for the MAE of DWI Intensity, by a circle (○) for the Mean LED, and by a diamond (◇) for the MAE for FA.

Our choice to use spatially-varying regularization was motivated by the fact that distortion correction is more ill-posed in highly distorted regions than in less-distorted regions. Figure 9 illustrates this in more detail with the 4-IPED in vivo data. In particular, Fig. 9(a) shows Wv (the magnitude of the gradient of B0) for several slices of the in vivo data, and Fig. 9(b) plots the MAE of the DWI intensities as a function of the amount of local image distortion. This was achieved by partitioning the image into mildly, moderately, and severely distorted regions based on Wv, identical to the partition used for Figs. 6 and 7(a). For easier interpretation of these plots, we did not use spatial weights for the spherical smoothness constraint, i.e., αv = α for all v instead of αv = αΛv. The figure demonstrates that imposing the spherical q-space smoothness constraint becomes more important as the amount of distortion increases, which is consistent with our use of spatially-varying αv. In addition, we observe that the optimal β is not highly dependent on the amount of distortion. We compare the use of spatially-varying αv with spatially invariant αv for the in vivo data in Fig. 9(c), and observe that the use of spatially-varying αv substantially improves distortion correction in severely distorted brain regions in the frontal and temporal lobes.

Figure 9.

(a) Magnitude of the spatial gradient vector of the B0 fieldmap (Wv) for several axial slices (units of Hz/mm). (b) MAEs of the distortion corrected image intensities, as a function of the amount of local geometric distortion and the spherical-smoothness and spatial-smoothness regularization parameters α and β. Regularization parameters corresponding to minimum MAE are marked respectively by a plus sign (+), a cross (×), and a star (⋆) for minimally, moderately, and severely distorted regions. (c) Whole-brain MIP images of the image-intensity error maps resulting from (left) no spherical smoothness regularization (αv = 0 for all v), (center) spatially-invariant spherical smoothness regularization (αv = α for all v), and (right) spatially-varying spherical smoothness regularization (αv = αΛv). (top row) Axial MIP images. (bottom row) Sagittal MIP images. Error images were computed with respect to 4-PED full data, since no ground truth exists for in vivo data.

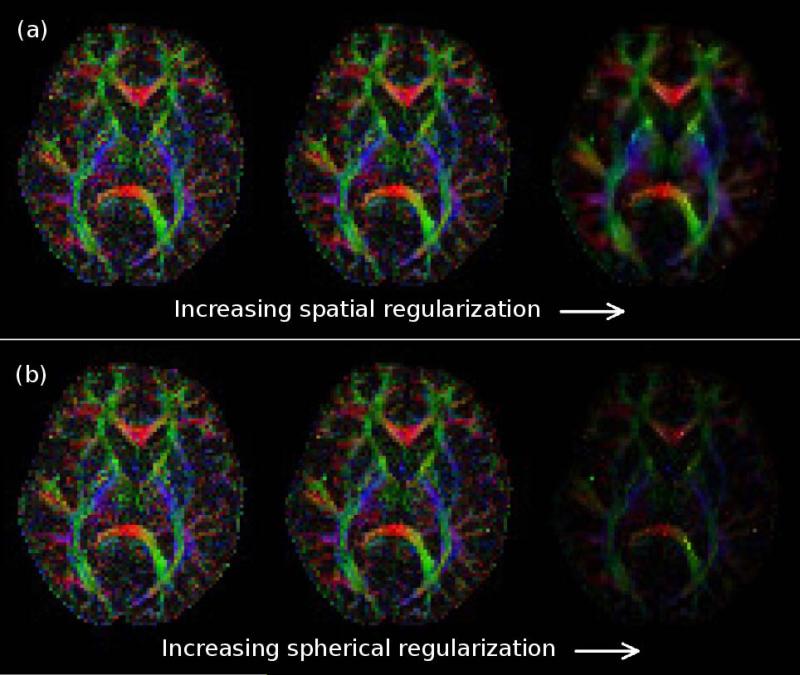

A further illustration of the impact of the regularization parameters is presented in Fig. 10, which shows the color-coded FA images that result when α or β are too large or too small. As expected from theory, we observe that when either of the regularization parameters is too small, the resulting color FA maps are quite noisy. On the other hand, setting the regularization parameters too high leads to over-smoothing. As predicted, over-smoothing manifests as a loss in spatial resolution for the case of spatial regularization, and as a reduction in anisotropy for the case of spherical regularization.

Figure 10.

Color-coded FA maps shown as a function of the (a) spatial-smoothness regularization parameter β and the (b) spherical-smoothness regularization parameter α. (left) Regularization parameters that are too small lead to noisy results. (center) Reasonable regularization parameters lead to reasonable results. (right) Regularization parameters that are too large lead to over-smoothing.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrated that the proposed PED-interlaced methods can accurately correct DWI distortion without increasing scan time, and that the 4-IPED acquisition yields the best performance. The approach uses a relatively small modification of a conventional acquisition, and can be implemented from the console (without changing pulse sequence code) if the existing diffusion pulse sequence allows flexible choice of the PED. For example, the IPED acquisition can easily be implemented in this case by dividing the acquisition into two or more segments, where each segment is acquired separately using a different PED and a different diffusion gradient table. With this setup, the PEDs would be interlaced in q-space, but not in time. Note that the proposed IPED approach could also be implemented with more than 4 PEDs, with potential for additional gains in performance.

Since our proposed approach involves changing PEDs, it is relevant to mention that different PEDs can be associated with different incidence rates for peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) (26). No subjects experienced PNS during our experiments with using multiple EPI PEDs, though results may vary on different scanners with different pulse sequence protocols.

Similar to other regularized methods, the performance of the proposed approach depends on the choice of regularization parameters. In this work, we selected the optimal parameters by comparing our corrected images with accurate reference images. However, this approach is impractical for real applications. One approach to avoiding this problem could be to use automatic regularization parameter selection techniques (27). However, it should be noted that optimal regularization parameters will depend on the choice of error measure, and that automated parameter selection techniques might not available for many of the error measures that would be most relevant to diffusion MRI. We expect that optimal regularization parameters will be relatively consistent for data collected with the same sequence on the same scanner, so that reasonable regularization parameters would only need to be calibrated once.

Our proposed method can also be modified to use more advanced regularization constraints, including the use of the previously mentioned edge- and rank-constraints (14, 15). This could, for example, be achieved by augmenting the cost function in Eq. [2] with appropriate additional penalty terms. The proposed approach can also be used with q-space data that is not sampled on a sphere (e.g., multi-shell acquisitions (24) or diffusion spectrum imaging (28)), as long as an appropriate regularization penalty is used to couple the reconstruction of neighboring q-space samples together. In addition, our proposed method can also be modified to use more advanced noise models. Our proposed formulation used the -norm to measure data consistency, which is the optimal choice when the noise is Gaussian. Since the noise in MR magnitude images is approximately Gaussian at high SNR, our choice was appropriate for high-SNR experiments. However, low-SNR is frequently encountered in certain diffusion imaging scenarios, particularly when acquiring data with high b-values. For these cases, the noise is more appropriately modeled using Rician or non-central chi signal distributions. Our proposed approach is easily adapted to these cases by replacing the -norm data consistency term in Eq. [2] with an appropriate Rician or non-central chi log-likelihood function, and using efficient algorithms to optimize the resulting cost function (29).

In principle, our proposed q-space smoothness constraint could also be applied to fully-sampled RG or 4-PED acquisitions. We studied this possibility, but only observed minor improvements in quantitative performance. This is not unexpected, since the main purpose of the q-space smoothness constraint in our proposed IPED scheme was to compensate for information that is missing with the IPED acquisition, but which is present in fully-sampled non-interlaced acquisitions. Another interesting observation from our study is that the fully-sampled 4-PED acquisition can lead to even better performance than the RG method. This is not surprising, since it uses twice as much data and more comprehensive encoding of distorted image regions.

In this work, we demonstrated good performance of our proposed IPED approach with an acquisition that sampled a relatively small number of q-space samples. However, it should be noted that our assumption that neighboring q-space samples have similar image structure and contrast will become more accurate as the q-space sampling density increases. As a result, we would expect even better distortion correction for large numbers of q-space samples, e.g., as in HARDI acquisitions. On the other hand, our assumptions might not be accurate enough for fewer than 20 q-space samples, though this issue remains to be investigated. However, it should also be noted that most quantitative diffusion experiments perform best when more than 20 q-space samples are acquired, even in the absence of significant image distortions (30).

The proposed method relies on accurate models of geometric distortion that are computed based on B0 fieldmaps. However, our distortion model may be inaccurate if the fieldmap is noisy and/or if there are significant geometric distortion artifacts that are not related to B0 inhomogeneity (i.e., from concomitant fields, non-linear gradients, or eddy currents (4)), and an inaccurate distortion model can severely degrade the performance of all fieldmap-based distortion methods. The effects of noisy fieldmaps can be minimized by acquiring higher-quality field mapping data and/or using regularized fieldmap estimation (31). If eddy current or concomitant field artifacts were present in the data, we would ideally want to also model their effects in the Dq geometric distortion operators. This was not necessary in our experiments, since the data was acquired axially at 3T and had negligible concomitant field effects, and because the acquisition used a twice-refocused spin-echo sequence to significantly reduce eddy current effects (32).

In our experiments, the fieldmaps were estimated from two gradient echo images, which requires a moderate amount of extra acquisition time. However, we should note that the details of fieldmap estimation are not essential to the proposed IPED method, and that there are other potentially faster B0 fieldmap estimation schemes. For example, many previous RG methods (11–13) were able to estimate accurate B0 fieldmaps directly from the distorted DWI data, without any increase in acquisition time. Similar B0 fieldmap estimation techniques could also be used with IPED data (e.g., from two b=0s/mm2 images acquired with opposite PEDs).

CONCLUSIONS

We have proposed and evaluated a novel distortion correction method for DWIs that enables high-quality distortion correction without measuring q-space samples more than once. The proposed method combines a novel q-space sampling scheme (in which neighboring q-space samples are acquired with different PEDs) with a novel constrained reconstruction approach that leverages the fact that DWIs from neighboring q-space samples are related to each other. Our results demonstrated that the proposed method provides substantially better distortion correction performance than the single-PED method, and similar performance to the RG method while using only half as much data. We expect that this accelerated approach to highly-quality distortion correction will make accurate geometric distortion correction methods more practical for a range of different experimental contexts.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported in part by NIH grants R01-NS074980 and P41-EB015922.

APPENDIX A: Spherical Harmonics and the Laplace-Beltrami Operator

As described in the Theory section, we represent the distortion-free signal (unknown, and to be estimated using Eq. [2]) using a SH representation to simplify the use of spherical q-space smoothness constraints. Our SH modeling representation is identical to that described in Ref. (16). These details from Ref. (16) are repeated here for the sake of completeness.

We assume that diffusion data is sampled on the surface of the sphere along Q different gradient orientations, which are defined in terms of the standard polar angles (θq ∈ [0, π], ϕq ∈ [0, 2π]) for q = 1, 2, . . . , Q. As with all data sampled on the sphere, it is possible to represent the element in the vth row and qth column of the S matrix (i.e., the diffusion data for the vth voxel and qth q-space sample) in an orthonormal basis of spherical harmonics according to

| [4] |

where [C]v,n is the nth SH coefficient for the vth voxel, [Y]n,q = Yn(θq, ϕq) is the nth modified (real and symmetric) SH basis function sampled along qth diffusion encoding direction (16), and N is the number of SH basis functions used in the representation. The modified SH basis functions are defined in terms of the order-L truncation of the even-order standard SH basis functions , which are given by

| [5] |

for and , where is the associated Legendre polynomial of order ℓ and degree m. The truncated modified SH basis function Yn(θ, ϕ) is obtained by defining the index n in terms of ℓ and m according to , and setting

| [6] |

for and . Note that N = (L + 1)(L + 2)/2.

The SHs have the special property that they are eigenfunctions of the Laplace-Beltrami operator. As a result, applying the Laplace-Beltrami operator in the SH domain is equivalent to multiplying the N SH coefficients for each voxel by an N × N diagonal matrix L. The nth diagonal element of L is equal to , where is the spherical harmonic order used in Eq. [6] when constructing Yn(θ, ϕ) (16). This result is used in the spherical smoothness term from Eq. [2].

APPENDIX B: Linear Least Squares Formulation

The solution to Eq. [2] can be obtained by solving the following equivalent linear least squares problem:

| [7] |

In this expression:

The vector c is the length-V N concatenation of the SH coefficient vectors for each voxel cv for v = 1, . . . , V;

The vector d is the length-V Q concatenation of the distorted DWIs dq for q = 1, . . . , Q;

The linear operator , which can also be expressed as a sparse matrix of size V Q × V N, converts a vector of SH coefficients into the undistorted DWI vectors sq for q = 1, . . . , Q according to Eq. [4], and then concatenates the sq vectors into a single length-V Q vector;

D is a V Q × V Q block-diagonal matrix with Q diagonal blocks. The diagonal blocks are each of size V×V, and are equal to Dq for q = 1, . . . , Q. Dq is a function of the PED for the qth q-space sample, and the number of unique Dq matrices is equal to the total number of PEDs used;

A is a V × V diagonal matrix with vth diagonal entry equal to ;

0F and 0L are zero vectors of length 2V Q and V N, respectively;

F and L are defined in eq. [2] and Appendix A, respectively;

I is the Q × Q identity matrix; and

The symbol ⊗ denotes the standard Kronecker product.

APPENDIX C: Gradient and PED Table

The gradient orientations and PEDs used for the simulation and in vivo experiments are shown in Table 1. We show only the L/R version of the 2-IPED scheme. The 2-IPED A/P scheme can be derived from the L/R scheme by replacing L and R with A and P, respectively.

Table 1.

Table of the gradient orientations and PEDs used for the simulation and in vivo experiments.

| Gradient Orientation | PED | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | 2-IPED | 4-IPED |

| 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | L | L |

| 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | R | R |

| −0.0310 | 0.8034 | −0.5947 | R | P |

| 0.8554 | 0.4976 | 0.1441 | R | A |

| 0.8348 | 0.3138 | −0.4523 | R | A |

| 0.8348 | −0.3138 | −0.4523 | L | P |

| 0.8554 | −0.4976 | 0.1441 | R | R |

| 0.8239 | −0.0045 | 0.5668 | L | P |

| 0.5508 | 0.4313 | 0.7146 | L | R |

| 0.4666 | 0.8370 | 0.2858 | R | P |

| 0.5144 | 0.8121 | −0.2754 | L | L |

| 0.3919 | 0.5211 | −0.7582 | L | P |

| 0.4789 | −0.0036 | −0.8779 | R | R |

| 0.3919 | −0.5211 | −0.7582 | L | L |

| 0.5144 | −0.8121 | −0.2754 | R | A |

| 0.4666 | −0.8370 | 0.2858 | L | L |

| 0.5508 | −0.4313 | 0.7146 | R | A |

| 0.1102 | −0.2686 | 0.9569 | L | R |

| 0.1102 | 0.2686 | 0.9569 | R | L |

| 0.0310 | 0.8032 | 0.5949 | L | A |

APPENDIX D: Log-Euclidean Distance

The similarity-invariant Log-Euclidean distance between diffusion tensors S1 and S2 is defined as (25):

| [8] |

where log(·) denotes the matrix logarithm. See Ref. (25) for implementation details and further discussion of this metric.

Footnotes

In this paper, we use the term ‘PED’ to denote both the axis and the polarity of the phase encoding gradients

MAE was chosen over mean-squared error because it is more robust to outliers. However, results with both MAE and mean-squared error were qualitatively similar in all of our experiments.

References

- 1.Jones DK. Diffusion MRI: Theory, Methods, and Applications. Oxford University Press 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tournier JD, Mori S, Leemans A. Diffusion tensor imaging and beyond. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:1532–1556. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Bihan D, Johansen-Berg H. Diffusion MRI at 25: Exploring brain tissue structure and function. NeuroImage. 2012;61:324–341. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson JLR, Skare S. Jones DK, editor. Image distortion and its correction in diffusion MRI. Diffusion MRI: Theory, Methods, and Applications. 2011:285–302. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones DK, Cercignani M. Twenty-five pitfalls in the analysis of diffusion MRI data. NMR Biomed. 2010;23:803–820. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irfanoglu MO, Walker L, Sarlls J, Marenco S, Pierpaoli C. Effects of image distortions originating from susceptibility variations and concomitant fields on diffusion MRI tractography results. NeuroImage. 2012;61:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jezzard P, Balaban RS. Correction for geometric distortion in echo planar images from B0 field variations. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:65–73. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munger P, Crelier GR, Peters TM, Pike GB. An inverse problem approach to the correction of distortion in EPI images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2000;19:681–689. doi: 10.1109/42.875186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan PS, Bowtell RW, McIntyre DJO, Worthington BS. Correction of spatial distortion in EPI due to inhomogeneous static magnetic fields using the reversed gradient method. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19:499–507. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang H, Fitzpatrick J. A technique for accurate magnetic resonance imaging in the presence of field inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1992;11:319–329. doi: 10.1109/42.158935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersson JLR, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage. 2003;20:870–888. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland D, Kuperman JM, Dale AM. Efficient correction of inhomogeneous static magnetic field-induced distortion in echo planar imaging. NeuroImage. 2010;50:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallichan D, Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, Robson MD, Miller KL. Reducing distortions in diffusion-weighted echo planar imaging with a dual-echo blip-reversed sequence. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:382–390. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haldar JP, Wedeen VJ, Nezamzadeh M, Dai G, Weiner MW, Schuff N, Liang ZP. Improved diffusion imaging through SNR-enhancing joint reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:277–289. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam F, Babacan SD, Haldar JP, Weiner MW, Schuff N, Liang ZP. Denoising diffusion-weighted magnitude MR images using rank and edge constraints. Magn Reson Med. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mrm.24728. Doi: 10.1002/mrm.24728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Descoteaux M, Angelino E, Fitzgibbons S, Deriche R. Regularized, fast, and robust analytical Q-ball imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:497–510. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hess CP, Mukherjee P, Han ET, Xu D, Vigneron DB. Q-ball reconstruction of multimodal fiber orientations using the spherical harmonic basis. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:104–117. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson AW. Measurement of fiber orientation distributions using high angular resolution diffusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1194–1206. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paige CC, Saunders MA. LSQR: An algorithm for sparse linear equations and sparse least squares. ACM Trans Math Soft. 1982;8:43–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fessler JA, Lee S, Olafsson VT, Shi HR, Noll DC. Toeplitz-based iterative image reconstruction for MRI with correction for magnetic field inhomogeneity. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2005;53:3393–3402. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutton B, Noll D, Fessler J. Fast, iterative image reconstruction for MRI in the presence of field inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2003;22:178–188. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2002.808360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gai J, Obeid N, Holtrop JL, Wu XL, Lam F, Fu M, Haldar JP, Hwu WW, Liang ZP, Sutton BP. More IMPATIENT: A gridding-accelerated Toeplitz-based strategy for non-Cartesian high-resolution 3D MRI on GPUs. J Parallel Distrib Comput. 2013;73:686–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jpdc.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones DK, Horsfield M, Simmons A. Optimal strategies for measuring diffusion in anisotropic systems by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:515–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caruyer E, Lenglet C, Sapiro G, Deriche R. Design of multishell sampling schemes with uniform coverage in diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:1534–1540. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arsigny V, Fillard P, Pennec X, Ayache N. Log-Euclidean metrics for fast and simple calculus on diffusion tensors. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:411–421. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ehrhardt JC, Lin CS, Magnotta VA, Fisher DJ, Yuh WTC. Peripheral nerve stimulation in a whole-body echo-planar imaging system. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;7:405–409. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880070226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kilmer ME, O'Leary DP. Choosing regularization parameters in iterative methods for ill-posed problems. SIAM J Matrix Anal Appl. 2001;22:1204–1221. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wedeen VJ, Hagmann P, Tseng WYI, Reese TG, Weisskoff RM. Mapping complex tissue architecture with diffusion spectrum magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1377–1386. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varadarajan D, Haldar JP. A quadratic majorize-minimize framework for statistical estimation with noisy Rician and noncentral chi-distributed MR images. Proc IEEE ISBI. 2013:708–711. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones DK. The effect of gradient sampling schemes on measures derived from diffusion tensor MRI: A Monte Carlo study. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:807–815. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernando D, Kellman P, Haldar JP, Liang ZP. Robust water/fat separation in the presence of large field inhomogeneities using a graph cut algorithm. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:79–90. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reese TG, Heid O, Weisskoff RM, Wedeen VJ. Reduction of eddy-current-induced distortion in diffusion MRI using a twice-refocused spin echo. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:177–182. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]