Abstract

AIM: To investigate the feasibility of lectin microarray for differentiating gastric cancer from gastric ulcer.

METHODS: Twenty cases of human gastric cancer tissue and 20 cases of human gastric ulcer tissue were collected and processed. Protein was extracted from the frozen tissues and stored. The lectins were dissolved in buffer, and the sugar-binding specificities of lectins and the layout of the lectin microarray were summarized. The median of the effective data points for each lectin was globally normalized to the sum of medians of all effective data points for each lectin in one block. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded gastric cancer tissues and their corresponding gastric ulcer tissues were subjected to Ag retrieval. Biotinylated lectin was used as the primary antibody and HRP-streptavidin as the secondary antibody. The glycopatterns of glycoprotein in gastric cancer and gastric ulcer specimens were determined by lectin microarray, and then validated by lectin histochemistry. Data are presented as mean ± SD for the indicated number of independent experiments.

RESULTS: The glycosylation level of gastric cancer was significantly higher than that in ulcer. In gastric cancer, most of the lectin binders showed positive signals and the intensity of the signals was stronger, whereas the opposite was the case for ulcers. Significant differences in the pathological score of the two lectins were apparent between ulcer and gastric cancer tissues using the same lectin. For MPL and VVA, all types of gastric cancer detected showed stronger staining and a higher positive rate in comparison with ulcer, especially in the case of signet ring cell carcinoma and intra-mucosal carcinoma. GalNAc bound to MPL showed a significant increase. A statistically significant association between MPL and gastric cancer was observed. As with MPL, there were significant differences in VVA staining between gastric cancer and ulcer.

CONCLUSION: Lectin microarray can differentiate the different glycopatterns in gastric cancer and gastric ulcer, and the lectins MPL and VVA can be used as biomarkers.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Gastric ulcer, Lectin microarray, Lectin histochemistry, Differentiate

Core tip: To assess the different glycopatterns in gastric ulcer and cancer by lectin microarray, which was then validated by lectin histochemistry. The results showed that the glycosylation level of gastric cancer was significantly higher than that in ulcer; the subsequent validation with two lectins (MPL and VVA) using lectin histochemistry showed higher positive rates and signal intensity in all types of gastric cancer detected, when compared with ulcer, which was consistent with the results of the lectin microarray, suggesting that GalNAc bound by the lectins MPL and VVA could be used to distinguish gastric cancer from ulcer.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the most common epithelial cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer death, with an incidence of 18.9/100000 per year[1,2]. It has been estimated that there are more than 934000 cases of gastric cancer worldwide, with 56% of newly diagnosed cases in East Asia[3]. In China, there are 400000 new cases of gastric cancer and 300000 deaths annually, making gastric cancer China’s third most common type of cancer[4]. Surgery is the only known cure, so new prognostic indicators or tumour markers are necessary to increase patient survival, improve treatment outcome, and facilitate early diagnosis[5].

The relation between gastric ulcers and cancer has long been disputed, ever since Cruveilhier first distinguished clearly between chronic ulcer and cancer, both clinically and pathologically, in 1839[6], but there is accumulating evidence that gastric ulcer disease is positively associated with the risk of developing stomach cancer[7]. The presenting symptoms of early gastric cancer resemble those of a benign gastric ulcer[8,9]. The symptoms of gastric cancer are similar to those of gastric ulcer, and gastric cancers often seem to be benign ulcers, making them difficult to differentiate, which leads to delayed diagnosis and the continued development of gastric cancer. Therefore, a tool for distinguishing early gastric cancer from ulcers is necessary.

Protein glycosylation, the attachment of a saccharide moiety to a protein, is a modification that occurs post-translationally. Two major types of glycosylation exist: N-linked and O-linked-N-glycosylation to the amide nitrogen of asparagine (Asn) side chains and O-glycosylation to the hydroxyl groups of serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) side chains. Glycosylation plays a key role in various biological processes, such as development, disease, intercellular signalling, protein-protein interaction, protein folding, cellular regression and metabolism, and other processes[10-14]. Aberrant alterations of glycosylation have been associated with the development and progression of cancer[15-18]. N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (GalNAc) is the substrate of N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases, and is catalysed to a peptide substrate by this enzyme. Differences in the tissue distribution and substrate specificity towards peptides are related to the diverse functions of these different subtypes of GalNAc-Tases. A GalNAc-Tase expression pattern has been reported in several types of cancer[19-22], including gastric cancer[22-25], which suggests that GalNAc plays a key role in gastric cancer genesis.

In the past two decades, lectins have been the main means of investigating glycosylation. Lectins are sugar-binding proteins that are highly specific for their sugar moieties. Since 2005, lectin microarray technology has emerged as a relatively simple but powerful technique for the comprehensive analysis of glycoprotein glycosylation[26,27]. The display of lectins in a microarray enables multiple and distinct binding glycopatterns to be observed simultaneously, providing information on the carbohydrate composition of the samples. Lectin microarray is a sensitive tool with the potential to allow high-throughput analysis of cancer-associated changes in glycosylation, and it has been used for biomarker discovery for cancer.

In this study, we first investigated the differences in glycopatterns between gastric ulcer and cancer using a lectin microarray, and the results were further validated by lectin histochemistry. Our results showed that the glycosylation level of gastric ulcer was lower than that of gastric cancer in general, and the subsequent lectin histochemistry using two selected lectins (MPL and VVA) suggested that these lectins could be used as biomarkers to distinguish gastric cancer from ulcer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens

Human gastric ulcer (n = 20) and gastric cancer tissues (n = 20) were obtained from the Affiliate Hospital of Beihua University (Jilin, China) as frozen tissues, and the diagnosis confirmed by pathologists. Proteins were extracted from the frozen tissues using T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent mixed with proteinase inhibitor (Sigma), then quantified and stored at -80 °C until use.

Lectin microarrays

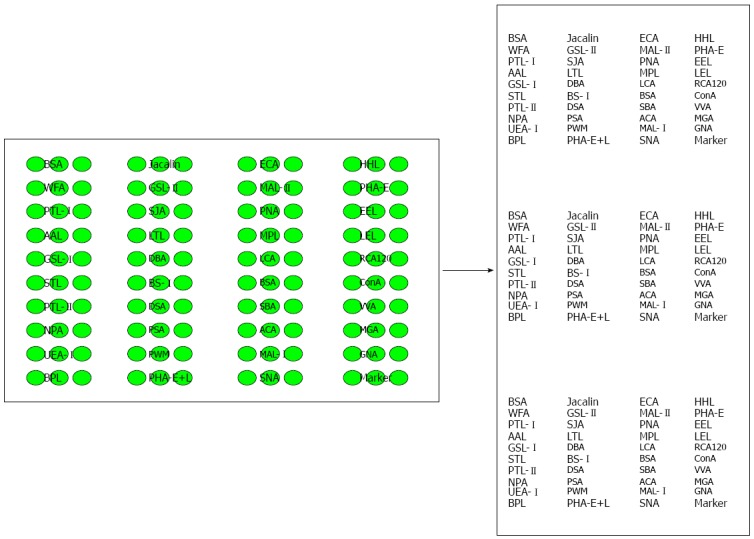

A lectin microarray was produced using 37 lectins (purchased from Vector Laboratories, Sigma-Aldrich, and Calbiochem) with different binding preferences covering N- and O-linked glycans, as described previously[28]. The lectins were dissolved in the manufacturer’s recommended buffer containing 1 mmol/L appropriate monosaccharide to a concentration of 1 mg/mL and spotted on the homemade epoxysilane-coated slides according to the protocol using Stealth micro spotting pins (SMP-10B) (TeleChem, United States) and a Capital smart microarrayer (CapitalBio, Beijing). The sugar-binding specificities of the lectins and the layout of the lectin microarray (Figure 1) were summarized. Each lectin was pointed on plate for use. The extracted tissue protein was labelled with Cy3 fluorescent dye (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) and purified using Sephadex G-25 columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Thereafter, Cy3-labelled protein was applied to the blocked lectin microarrays and incubation was performed in a chamber at 37 °C for 3 h in a rotisserie oven set at 4 r/min. The slides were washed twice with 1 × PBST, each for 5 min, and washed once with 1 × PBS for 5 min, and dried by centrifugation at 600 r/min for 5 min. Finally, the microarrays were scanned using a Genepix 4000B confocal scanner (Axon Instruments, United States) set at 70% photomultiplier tube and 100% laser power. The acquired images were analysed using Genepix 3.0 software (Axon Instruments, Inc., United States). The average background was subtracted and values less than average background ± 2 SD were removed from each data point. The median of the effective data points for each lectin was globally normalized to the sum of medians of all effective data points for each lectin in one block. Each sample was observed on three replicate slides and the normalized medians of each lectin from nine replicate blocks were averaged and the SD calculated.

Figure 1.

Sugar-binding specificities of the lectins and the layout of the lectin microarray.

Lectin histochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded gastric cancer tissues and their corresponding adjacent gastric tissues were subjected to Ag retrieval in 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer solution, pH 6.0 at 100 °C in a microwave for 15 min. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed according to a standard protocol[29]. Biotinylated lectin was used as the primary antibody and HRP-streptavidin as the secondary antibody.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD for the indicated number of independent experiments. Statistical differences between groups were calculated using Student’s two-tailed t test. Differences were considered statistically significant for values of P < 0.05, P < 0.01 or P < 0.001.

RESULTS

Glycopatterns of glycoproteins in gastric ulcer and cancer

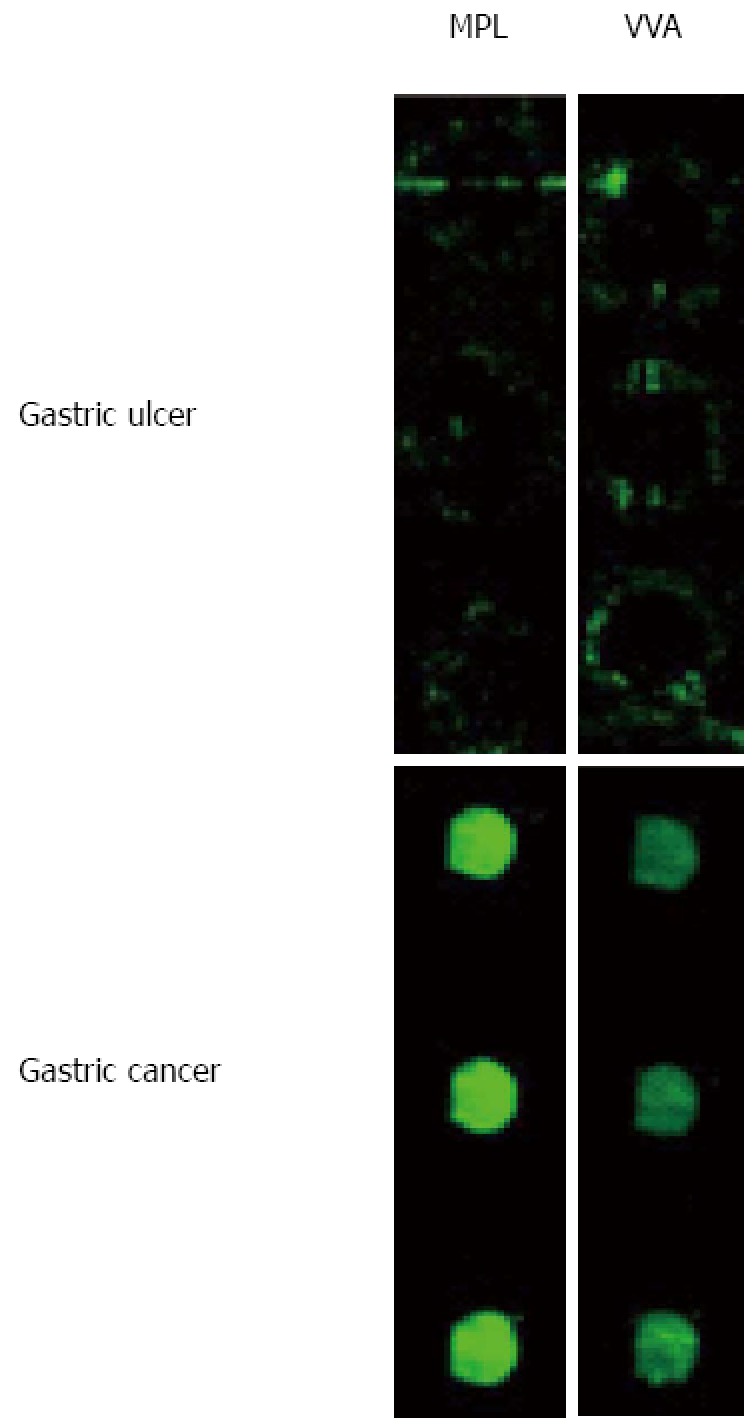

The glycopatterns of glycoproteins provide us with clues about the expression and function of oligosaccharides. Here, we hoped to discover which glycans emerge and how they differ between gastric ulcer and cancer, by detecting glycan expression using high-throughput lectin arrays. The proteins of 20 cases of gastric ulcer and cancer tissue were extracted and pooled together respectively; 37 lectins were subsequently analysed, and the results of the lectin microarrays, and the specific sugars recognized by the lectins as well as the normalized fluorescent intensities are summarized in Table 1. As shown, in gastric ulcers, 20 of the 37 lectins produced no signal. The others produced a weak signal. Among these lectins, GalNAc and Gal binder SJA, Galβ1-3GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(T) binder PNA, and GlcNAc binder GST-I binder GSL-I produced higher intensity signals in ulcers compared to gastric cancer. Galα1-3(Fucα1-2)Gal binder EEL, GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(Tn) binder DBA, Gal and GalNAc binder RAC120, α-Man binder ConA, Polymannose (α-1,6) linked mannose binder NPA, Fucα-N-acetylchitobiose-man binder PSA, Galβ1-3GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(Tn) binder ACA, Sia2-3Gal1-4GlcNAc binder Mal-I, (α-1,3) Man binder GNA, and Sia2-6Galβ1-4Glc(NAc) binder SNA produced lower intensity signals in ulcers, in contrast to gastric cancer. The signals produced by Gal binder DSA, α-L-Fucose binder LTL, GlcNAc trimer/tetramer binder LEL, and GlcNAc binder STL did not differ in intensity between tissues. Representative images of the microarray are shown (Figure 2). The microarray data showed that the glycopatterns of ulcer and gastric cancer tissue differed. In gastric cancer, most of the lectin binders gave positive signals and the intensity of the signals was strong, whereas the opposite was the case for ulcers, suggesting that alterations in glycans might underlie the switch from ulcer to gastric cancer, and could be used to diagnose gastric cancer. The αGalNAc binder MPL and the GalNAc and GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(Tn) binder VVA were subsequently selected for further validation.

Table 1.

Clinical information about patients

| Patients No. | Gender | Age | Type of disease |

| 1 | Male | 64 | EGC |

| 2 | Female | 72 | EGC |

| 3 | Male | 70 | EGC |

| 4 | Male | 66 | EGC |

| 5 | Female | 68 | EGC |

| 6 | Female | 63 | BGU |

| 7 | Female | 53 | BGU |

| 8 | Female | 50 | BGU |

| 9 | Male | 49 | BGU |

| 10 | Male | 33 | BGU |

EGC: Early gastric cancer, BGU: Benign gastric ulcer.

Figure 2.

Glycopatterns of gastric cancer and ulcer according to lectin microarrays. After scanning of MPL and VVA lectins, a diagram was shown.

Validation of the differential glycopatterns by lectin histochemistry

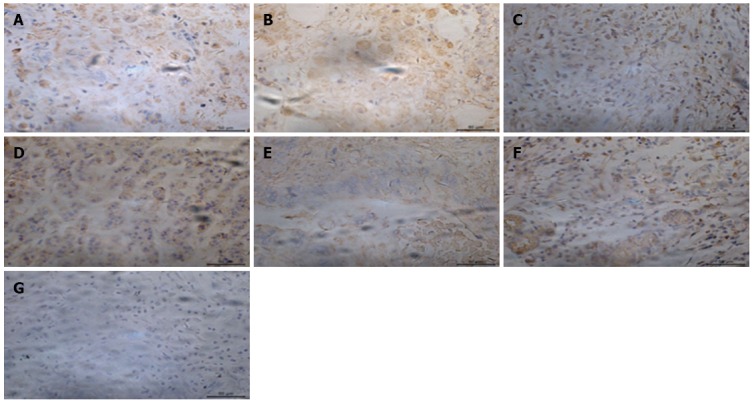

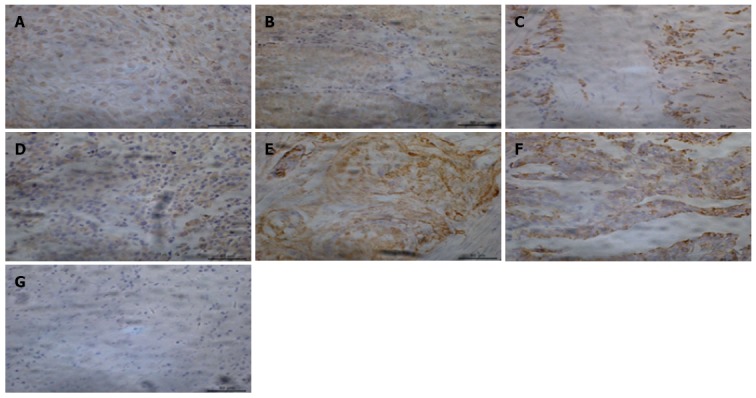

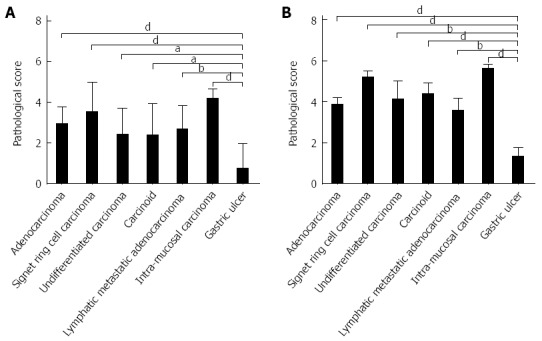

Although the lectin microarrays showed differences in the glycopatterns of gastric ulcer compared with gastric cancer, lectin histochemistry was required to validate these differences and determine the distribution of glycosidic residues. Two lectins (MPL and VVA) were selected and used for this validation. A tissue microarray (Alenabio Inc, Xi’an, China) was commercially available for this study. This array includes 9 cases of gastric ulcer and 58 cases of gastric cancer (22 cases of adenocarcinoma, 9 cases of signet ring cell carcinoma, 7 cases of undifferentiated carcinoma, 5 cases of carcinoid, 10 cases of lymphatic metastatic adenocarcinoma, and 5 cases of intra-mucosal carcinoma). All TMA spots were evaluated by the pathologist, who provided semi-quantitative estimates of the percentage of positive cells and the degree of staining. Lectin binding in the gastric cells resulted in no or very weak staining to intense to very intense staining; the staining intensity was graded by an experienced pathologist and analysed using the Fromowitz standard. In general, the most intensive reactions were found with the lectins MPL and VVA. Representative immunohistochemical images obtained using the antibody-biotinylated lectins are shown in Figures 3 and 4, and are consistent with the results of the lectin microarrays. Both lectins (MPL and VVA) strongly stained the gastric cancer tissues and the rate of positivity was high, unlike in gastric ulcer. Significant differences in the pathological score of these two lectins were visible between ulcer and gastric cancer tissues (Figure 5 and Table 2). In comparison with ulcer, all types of gastric cancer produced stronger staining and a higher positive rate for MPL and VVA, especially in signet ring cell carcinoma and intra-mucosal carcinoma. GalNAc that bound to MPL was significantly more abundant in gastric cancer. A statistically significant association between MPL and gastric cancer was observed. A representative example of tissue histology is shown in Figure 3. As with MPL, significant differences in VVA staining were observed between gastric cancer and ulcers (Figure 4). We also analysed other lectins including AAL, LEL, and PHA-E+L, and found that the glycan residues to which they bind were upregulated in different types of gastric cancer (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Level of GalNAc bound by MPL in various types of gastric cancer and gastric ulcer. A: Staining of adenocarcinoma (× 400); B: Staining of signet ring cell carcinoma (× 400); C: Staining of undifferentiated carcinoma (× 400); D: Staining of carcinoid (× 400); E: Staining of lymphatic metastatic adenocarcinoma (× 400); F: Staining of intra-mucosal carcinoma (× 400); G: Staining of gastric ulcer (× 400).

Figure 4.

Level of GalNAc bound by VVA in various types of gastric cancer and gastric ulcer. A: Staining of adenocarcinoma (× 400); B: Staining of signet ring cell carcinoma (× 400); C: Staining of undifferentiated carcinoma (× 400); D: Staining of carcinoid (× 400); E: Staining of lymphatic metastatic adenocarcinoma (× 400); F: Staining of intra-mucosal carcinoma (× 400); G: Staining of gastric ulcer (× 400).

Figure 5.

Pathological score of tissue staining. The figure compares gastric ulcer and various types of gastric cancer. A indicates MPL, and B represents VVA. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, dP < 0.01.

Table 2.

Differential glycopattern in gastric ulcer and cancer according to the lectin microarray analysis based on data from 37 lectins giving significant signals

| Lectin | Specificity |

Normalized fluorescent intensity1 |

Ratio, P value | |

| Gastric cancer | Gastric ulcer | (C/U) | ||

| Jacalin | Galβ1-3GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(T) and GalNACα-Ser/Thr(Tn) | 0.49 | - | P < 0.001 |

| ECA | Galβ-1,4GlcNAc | 0.72 | - | P < 0.001 |

| HHL | Polymannose (α-1,3) and (α-1,6) linked mannose | 0.64 | - | P < 0.001 |

| WFA | GalNAcα/β-1,3/6Gal | 0.64 | - | P < 0.001 |

| GSL-II | GlcNAc | 0.67 | - | P < 0.001 |

| MAL-II | Sia2-3Galβ1-4Glc (NAc) | - | - | / |

| PHA-E | Bisecting GlcNAc and biantennary N-glycans | 0.65 | - | P < 0.001 |

| PTL-I | αGalNAc | 0.67 | - | P < 0.001 |

| SJA | Terminal in GalNAc and Gal | 0.12 | 0.38 | 0.32, P < 0.001 |

| PNA | Galβ1-3GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(T) | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.36, P < 0.001 |

| EEL | Galα1-3(Fucα1-2)Gal | 1 | 0.23 | 4.41, P < 0.001 |

| AAL | Fucα-1,6GlcNAc, Fucα-1,3LacNAc | 0.89 | - | P < 0.001 |

| LTL | α-L-Fuc | 0.59 | 0.31 | / |

| MPL | αGalNAc | 0.69 | - | P < 0.001 |

| LEL | Poly-LacNAc and (GlcNAc)n | 0.54 | 0.27 | / |

| GSL-I | αGalNAc, αGal | - | 0.03 | P < 0.001 |

| DBA | GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(Tn) | 0.4 | 0.2 | / |

| LCA | α-Man and Fucα-1,6GlcNAc (core fucose) | 0.61 | - | P < 0.001 |

| RCA120 | Gal and GalNAc | 0.61 | 0.17 | 3.55, P < 0.001 |

| STL | (GlcNAc)n | 0.54 | 0.31 | / |

| BS-I | αGal and αGalNAc | 0.12 | - | P < 0.001 |

| ConA | α-Man (inhibited by presence of bisecting GlcNAc) | 0.13 | 0.11 | / |

| PTL-II | Gal | 0.66 | - | P < 0.001 |

| DSA | β1-4GlcNAc and LacNAc | 0.79 | 1 | 0.79, P < 0.001 |

| SBA | Terminal GalNAc (especially GalNAcα1-3Gal) | 0.38 | - | P < 0.001 |

| VVA | GalNAc and GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(Tn) | 0.45 | - | P < 0.001 |

| NPL | Polymannose(α-1,6)linked mannose | 0.64 | 0.12 | 5.21, P < 0.001 |

| PSA | Fucα-N-acetylchitobiose -man | 0.85 | 0.2 | 4.19, P < 0.001 |

| ACA | Galβ1-3GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(Tn) | 0.71 | 0.18 | 3.84, P < 0.001 |

| WGA | Terminal GlcNAc and (GlcNAc)n | 0.35 | - | P < 0.001 |

| UEA-I | Fucoseα1-2Galβ1-4Glc(NAc) | 0.81 | - | P < 0.001 |

| PWM | GlcNAc | 0.8 | - | P < 0.001 |

| MAL-I | Galβ-1,4GlcNAc and Sia2-3Galβ1-4Glc(NAc) | 0.63 | 0.16 | 3.89, P < 0.001 |

| GNA | (α-1,3)Man | 0.78 | 0.09 | 9.1, P < 0.001 |

| BPL | Galβ1-3GalNAc | 0.67 | - | P < 0.001 |

| PHA-E+L | Tri-and tetra-antennary complex-type N-glycan | 0.92 | - | P < 0.001 |

| SNA | Sia2-6Galβ1-4Glc(NAc) | 0.61 | 0.18 | 3.39, P < 0.001 |

Signal intensities obtained from nine replicate blocks on three replicate slides were normalized and averaged, and the ratio of gastric cancer vs gastric ulcer (C/U) was calculated. -: Negative signal; /: No significant difference.

Overall, lectin histochemistry revealed more positive cells and intensive staining in gastric cancer when compared with gastric ulcer using the two selected lectins (MPL and VVA), which was consistent with the results of the lectin microarray, suggesting that MPL and VVA could be used to distinguish gastric cancer from ulcer.

DISCUSSION

Gastric cancer is the most common epithelial cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer death, with an increasing number of new cases every year. New prognostic indicators or tumour markers are urgently required to increase patient survival, improve treatment outcome, and facilitate early diagnosis. The symptoms of gastric cancer are similar to those of gastric ulcer, and as gastric cancers often seem to be benign ulcers, they are difficult to differentiate, leading to delayed diagnosis and the continued development of gastric cancer. Therefore, a tool for distinguishing gastric cancer from ulcer is necessary. In this study, a lectin microarray was performed to compare the glycopatterns of gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. The results indicated that the glycosylation levels in gastric ulcer are lower than those in gastric cancer. Most lectins produced no signals in ulcers; the opposite was the case in gastric cancer. Subsequently, we selected two lectins (MPL and VVA) whose receptors were upregulated in gastric cancer to validate the results of the lectin microarrays using lectin histochemistry, and our results illustrated that the glycan residues that these two lectins bound were significantly elevated in gastric cancer compared with ulcer, which was consistent with the results of the lectin microarrays, and therefore that they could be used to distinguish gastric cancer from ulcer.

The lectin microarray is a promising technology in glycomics and glycoproteomics, utilizing a series of lectins immobilized on a well-defined substrate for high-throughput analysis of glycans and glycoproteins. It may also have great potential in disease biomarker studies. The microarray data showed that the glycopatterns differed between ulcers and gastric cancer, which is a promising starting point. The lectin microarray may turn out to be a promising tool for high-throughput analysis of clinical samples in an attempt to identify glycoprotein biomarkers for cancer detection. In this study, the lectin microarrays were used to probe differences in protein glycosylation between gastric ulcer and gastric cancerous tissues, revealing that glycosylation levels were higher in gastric cancer than in ulcers. The rate and intensity of the signals were higher in gastric cancer than in ulcers. In gastric ulcer, 20 of the 37 lectins produced no signal. The others produced weak signals. Among these lectins, GalNAc and Gal binder SJA, Galβ1-3GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(T) binder PNA, and GlcNAc binder GST-I binder GSL-I had increased signals in ulcer compared to gastric cancer. Galα1-3(Fucα1-2)Gal binder EEL, GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(Tn) binder DBA, Gal and GalNAc binder RAC120, α-Man binder ConA, Polymannose (α-1,6) linked mannose binder NPA,Fucα-N-acetylchitobiose-man binder PSA, Galβ1-3GalNAcα-Ser/Thr(Tn) binder ACA, Sia2-3Gal1-4GlcNAc binder Mal-I, (α-1,3) Man binder GNA, and Sia2-6Galβ1-4Glc(NAc) binder SNA had decreased signals in ulcer, in contrast to gastric cancer. Gal binder DSA, α-L-Fucose binder LTL, GlcNAc trimers/tetramers binder LEL, and GlcNAc binder STL had no differences. Representative images of the microarray are shown in Figure 2. The microarray data showed that the glycopatterns were different between ulcers and gastric cancer. In gastric cancer, most of the lectin binders showed positive signals and the intensity of the signals were stronger, whereas the results were the opposite in ulcers, which suggested that alteration of glycans might be the reason for the switch of ulcer to gastric cancer, and could be for diagnosis of gastric cancer.

To validate the results of the lectin microarray and detect glycosylation in cancerous cells and tissues, lectin histochemistry was performed. Two lectins (MPL and VVA) were selected, both of which were elevated in gastric cancer according to the lectin array. It has previously been reported that the receptors for these lectins are upregulated in various cancers[30-36]. The result showed that the two lectins moderately or strongly stained the cancerous tissues and the positive rate was higher than that in gastric ulcer. Significant differences were visible between gastric cancer and ulcer tissues when using the same lectin. Furthermore, different subtypes of gastric cancer showed different binding specificities. In comparison with ulcer, all types of gastric cancer showed stronger staining, especially in signet ring cell carcinoma and intra-mucosal carcinoma; GalNAc, that was bound by MPL and VVA, showed a significant increase. Lectin histochemistry indicated that more positive cells and intensive staining were present in gastric cancer when compared with gastric ulcer, which was consistent with the results of the lectin microarray.

In summary, we used a lectin microarray to investigate the different glycopatterns in gastric cancer and ulcer, revealing that the level of glycosylation was higher in gastric cancer than in gastric ulcer. Lectin histochemistry was then performed to validate the results of the lectin microarray. The results of the two approaches were consistent, indicating that the selected lectins, MPL and VVA, could be used to distinguish gastric cancer from ulcer.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric cancer is the most common epithelial cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer death. The relation between gastric ulcer and cancer has long been disputed. Therefore, a tool for distinguishing early gastric cancer from ulcer is necessary.

Research frontiers

In this study, the lectin microarray was first performed to compare the glycopatterns in gastric ulcer and gastric cancer, revealing that the glycosylation levels in gastric ulcer were lower than those in gastric cancer. The results illustrated that the glycan residues bound by the two lectins were significantly elevated in gastric cancer when compared with ulcer, which was consistent with the results of the lectin microarrays, and thus these lectins could be used to distinguish gastric cancer from ulcer.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This study used lectin microarray to investigate the different glycopatterns in gastric cancer and ulcer, revealing that the glycosylation level was higher in gastric cancer. Lectin histochemistry was then performed to validate the results of the lectin microarray. The results were consistent, indicating that the selected lectins, MPL and VVA, could be used to distinguish gastric cancer from ulcer.

Applications

The selected lectins, MPL and VVA, could be used to distinguish gastric cancer from ulcer.

Peer review

In this study, a lectin microarray was performed to compare the glycopatterns of gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. The results are promising and provide a new perspective for the diagnosis of gastric cancer.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Fondran JC, Senagore AJ, Silverman R S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Cunningham D, Jost LM, Purkalne G, Oliveira J. ESMO Minimum Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16 Suppl 1:i22–i23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue M, Tsugane S. Epidemiology of gastric cancer in Japan. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:419–424. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang L. Incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:17–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrelli D, Roviello F, De Stefano A, Farnetani M, Garosi L, Messano A, Pinto E. Prognostic significance of CEA, CA 19-9 and CA 72-4 preoperative serum levels in gastric carcinoma. Oncology. 1999;57:55–62. doi: 10.1159/000012001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakuta M. [One hundred books which built up neurology (35)--Cruveilhier J “Anatomie Pathologique du Corps Humain” (1829-1842)] Brain Nerve. 2009;61:1354–1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansson LE. Risk of stomach cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. World J Surg. 2000;24:315–320. doi: 10.1007/s002689910050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everett SM, Axon AT. Early gastric cancer in Europe. Gut. 1997;41:142–150. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hicks S. Gastric cancer: diagnosis, risk factors, treatment and life issues. Br J Nurs. 2001;10:529–536. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2001.10.8.5317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haltiwanger RS, Lowe JB. Role of glycosylation in development. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:491–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dennis JW, Granovsky M, Warren CE. Protein glycosylation in development and disease. Bioessays. 1999;21:412–421. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199905)21:5<412::AID-BIES8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler M. Optimisation of the cellular metabolism of glycosylation for recombinant proteins produced by Mammalian cell systems. Cytotechnology. 2006;50:57–76. doi: 10.1007/s10616-005-4537-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharon N, Lis H. Carbohydrates in cell recognition. Sci Am. 1993;268:82–89. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0193-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher CM, Coyne MJ, Villa OF, Chatzidaki-Livanis M, Comstock LE. A general O-glycosylation system important to the physiology of a major human intestinal symbiont. Cell. 2009;137:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell BJ, Yu LG, Rhodes JM. Altered glycosylation in inflammatory bowel disease: a possible role in cancer development. Glycoconj J. 2001;18:851–858. doi: 10.1023/a:1022240107040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YS, Yoo HS, Ko JH. Implication of aberrant glycosylation in cancer and use of lectin for cancer biomarker discovery. Protein Pept Lett. 2009;16:499–507. doi: 10.2174/092986609788167798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peracaula R, Barrabés S, Sarrats A, Rudd PM, de Llorens R. Altered glycosylation in tumours focused to cancer diagnosis. Dis Markers. 2008;25:207–218. doi: 10.1155/2008/797629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter TM, Brooks SA. Detection of aberrant glycosylation in breast cancer using lectin histochemistry. Methods Mol Med. 2006;120:201–216. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-969-9:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J, Yang L, Jin M, Xu L, Wu S. regulation of the invasion and metastasis of human glioma cells by polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2. Mol Med Rep. 2011;4:1299–1305. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taniuchi K, Cerny RL, Tanouchi A, Kohno K, Kotani N, Honke K, Saibara T, Hollingsworth MA. Overexpression of GalNAc-transferase GalNAc-T3 promotes pancreatic cancer cell growth. Oncogene. 2011;30:4843–4854. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berois N, Mazal D, Ubillos L, Trajtenberg F, Nicolas A, Sastre-Garau X, Magdelenat H, Osinaga E. UDP-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-6 as a new immunohistochemical breast cancer marker. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:317–328. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6783.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo JM, Chen HL, Wang GM, Zhang YK, Narimatsu H. Expression of UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-12 in gastric and colonic cancer cell lines and in human colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2004;67:271–276. doi: 10.1159/000081328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hua D, Shen L, Xu L, Jiang Z, Zhou Y, Yue A, Zou S, Cheng Z, Wu S. Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2 regulates cellular metastasis-associated behavior in gastric cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30:1267–1274. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomes J, Marcos NT, Berois N, Osinaga E, Magalhães A, Pinto-de-Sousa J, Almeida R, Gärtner F, Reis CA. Expression of UDP-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-6 in gastric mucosa, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric carcinoma. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:79–86. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.952283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onitsuka K, Shibao K, Nakayama Y, Minagawa N, Hirata K, Izumi H, Matsuo K, Nagata N, Kitazato K, Kohno K, et al. Prognostic significance of UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-3 (GalNAc-T3) expression in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:32–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilobello KT, Krishnamoorthy L, Slawek D, Mahal LK. Development of a lectin microarray for the rapid analysis of protein glycopatterns. Chembiochem. 2005;6:985–989. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenfeld R, Bangio H, Gerwig GJ, Rosenberg R, Aloni R, Cohen Y, Amor Y, Plaschkes I, Kamerling JP, Maya RB. A lectin array-based methodology for the analysis of protein glycosylation. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2007;70:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qin Y, Zhong Y, Dang L, Zhu M, Yu H, Chen W, Cui J, Bian H, Li Z. Alteration of protein glycosylation in human hepatic stellate cells activated with transforming growth factor-β1. J Proteomics. 2012;75:4114–4123. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen T, Li Y, Wu M, Sun X, Bao X, Lin Y, Hao J, Han L, Cao G, Wang Z, et al. Therapeutic effects of a novel tylophorine analog, NK-007, on collagen-induced arthritis through suppressing tumor necrosis factor α production and Th17 cell differentiation. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2896–2906. doi: 10.1002/art.34528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arndt NX, Tiralongo J, Madge PD, von Itzstein M, Day CJ. Differential carbohydrate binding and cell surface glycosylation of human cancer cell lines. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:2230–2240. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawaguchi T. Cancer metastasis: characterization and identification of the behavior of metastatic tumor cells and the cell adhesion molecules, including carbohydrates. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2005;5:39–64. doi: 10.2174/1568006053005038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konska G, Guerry M, Caldefie-Chezet F, De Latour M, Guillot J. Study of the expression of Tn antigen in different types of human breast cancer cells using VVA-B4 lectin. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:305–310. doi: 10.3892/or.15.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meany DL, Chan DW. Aberrant glycosylation associated with enzymes as cancer biomarkers. Clin Proteomics. 2011;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishiyama T, Matsumoto Y, Watanabe H, Fujiwara M, Sato S. Detection of Tn antigen with Vicia villosa agglutinin in urinary bladder cancer: its relevance to the patient’s clinical course. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78:1113–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takano Y, Teranishi Y, Terashima S, Motoki R, Kawaguchi T. Lymph node metastasis-related carbohydrate epitopes of gastric cancer with submucosal invasion. Surg Today. 2000;30:1073–1082. doi: 10.1007/s005950070004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terasawa K, Furumoto H, Kamada M, Aono T. Expression of Tn and sialyl-Tn antigens in the neoplastic transformation of uterine cervical epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2229–2232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]