Abstract

The increased presence of chemical contaminants in the environment is an undeniable concern to human health and ecosystems. Historically, by relying heavily upon costly and laborious animal-based toxicity assays, the field of toxicology has often neglected examinations of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of toxicity for the majority of compounds—information that, if available, would strengthen risk assessment analyses. Functional toxicology, where cells or organisms with gene deletions or depleted proteins are used to assess genetic requirements for chemical tolerance, can advance the field of toxicity testing by contributing data regarding chemical mechanisms of toxicity. Functional toxicology can be accomplished using available genetic tools in yeasts, other fungi and bacteria, and eukaryotes of increased complexity, including zebrafish, fruit flies, rodents, and human cell lines. Underscored is the value of using less complex systems such as yeasts to direct further studies in more complex systems such as human cell lines. Functional techniques can yield (1) novel insights into chemical toxicity; (2) pathways and mechanisms deserving of further study; and (3) candidate human toxicant susceptibility or resistance genes.

Keywords: yeast, toxicology, toxicity testing, functional toxicology, functional genomics, functional profiling

Chemical production and its implications

Current estimates project that global chemical production—currently growing 3% per year—will double every 25 years (Wilson et al., 2006). In the United States alone, excluding fuels, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, or food products, about 42 billion pounds of chemicals are produced or imported daily (U.S. EPA, 2005). Many chemicals are managed through the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), but several independent analyses have concluded that these regulations seriously hinder (1) toxicity testing and hazard assessment; (2) control of chemicals of concern; and (3) investment in safer alternatives, such as those generated by the tenets of green chemistry (Wilson and Schwarzman, 2009). Combined with the widespread use and distribution of industrial chemicals, the data and safety gaps precipitated by TSCA elicit a situation in which chemical exposures to humans and ecosystems are oftentimes of unknown hazard and risk.

The present state of chemical toxicity testing

The field of toxicology currently employs extensive animal-based assays to evaluate chemical toxicity, a burdensome and prohibitively expensive approach that typically assesses a limited number of endpoints. Considering that tens of thousands of in use chemicals lack adequate toxicity data (Judson et al., 2009), it is unreasonable to rely upon these traditional methods to fill data gaps. The National Research Council (NRC), realizing that more innovative approaches to testing were needed, envisioned that toxicology should commit to mechanistically-based high-throughput cellular in vitro assays (NRC, 2007; Andersen and Krewski, 2010). In this way, a more complete comprehension of chemical toxicity can be achieved, while expediting testing, decreasing costs, and reducing animal usage.

Although high-throughput in vitro methods certainly signal progress in toxicity testing, they are limited to existing assays with known endpoints, such as analyses of stress response pathways induced by oxidative species, heat shock, DNA damage, hypoxia, and unfolded proteins (Simmons et al., 2009). Another approach utilizes “omics” technologies such as gene expression profiling, proteomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics to conduct targeted and untargeted investigations into chemical mechanisms of toxicity (reviewed by Hamadeh et al., 2002; Gatzidou et al., 2007). However, by associating toxicant exposure with changes in mRNA, protein, lipid, or metabolite levels, these assays are correlative and do not provide direct links between genes and their requirements in the cellular toxicant response.

The advantages of functional toxicology

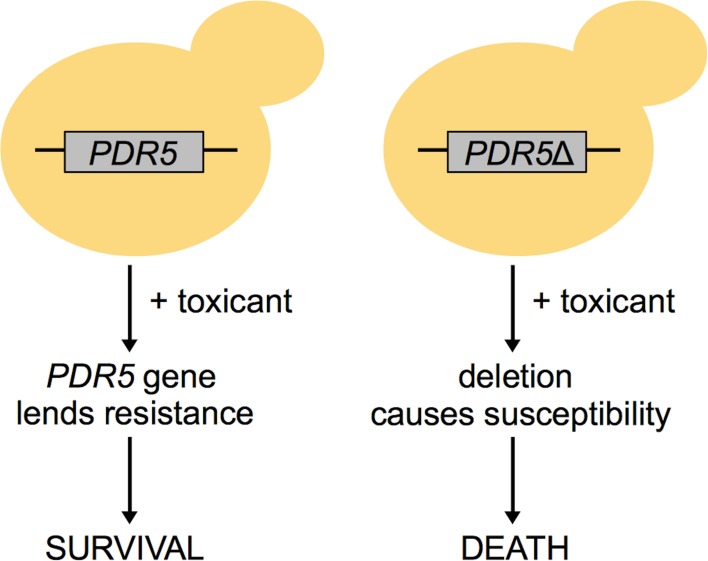

Functional toxicology is based in the high-throughput use of cells/organisms harboring gene deletions or depleted proteins to systematically examine genetic requirements for toxicity tolerance. Any assayable phenotype can be measured in response to a toxicant, but viability or fitness are the most conventional endpoints (Figure 1). Functional techniques can provide information distinct from the aforementioned correlative methodologies; for example, Giaever et al. (2002) found that expression of a gene is generally unrelated to its requirement for growth under a selective condition. Functional analyses, which have been conducted in budding and fission yeast (Table 1), bacteria, nematodes, fruit flies, zebrafish, and human cell lines (Table 2), can (1) contribute novel insight into chemical mechanisms of action; (2) define more specific toxicological endpoints; and (3) inform further mechanistic-based assays.

Figure 1.

The concept of functional toxicology in yeast. In this example, a yeast cell with the PDR5 gene is able to survive under toxicant selection, whereas a cell deleted for PDR5 experiences susceptibility to that same toxicant. Therefore, the PDR5 gene is essential for survival in that toxicant.

Table 1.

Summary of recent functional toxicological screens in yeasts.

| Chemical class | Description | Organism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvents | Butanol | S. cerevisiae | González-Ramos et al., 2013 |

| Dimethylsulfoxide | S. cerevisiae | Zhang et al., 2013 | |

| Dimethylsulfoxide | S. cerevisiae | Gaytán et al., 2013a | |

| Metals | Aluminum | S. cerevisiae | Tun et al., 2013 |

| Gold nanoparticles | S. cerevisiae | Smith et al., 2013 | |

| Cobalt | S. pombe | Ryuko et al., 2012 | |

| Cadmium | S. pombe | Kennedy et al., 2008 | |

| Persistent pollutants | Dieldrin | S. cerevisiae | Gaytán et al., 2013b |

| Toxaphene | S. cerevisiae | Gaytán et al., 2013c | |

| Antimicrobials | 2,4-diacetylphloro- glucinol | S. cerevisiae | Troppens et al., 2013 |

| Antimicrobial peptides | S. cerevisiae | Lis et al., 2013 | |

| Curcumin | S. cerevisiae | Azad et al., 2013 | |

| Chitosan | S. cerevisiae | Galván Márquez et al., 2013 | |

| Eugenol | S. cerevisiae | Darvishi et al., 2013a | |

| Thymol | S. cerevisiae | Darvishi et al., 2013b | |

| Polyalkyl guanidiniums | S. cerevisiae | Bowie et al., 2013 | |

| TA-289 | S. cerevisiae | Quek et al., 2013 | |

| Micafungin | S. pombe | Zhou et al., 2013 | |

| Various antifungals | S. pombe | Fang et al., 2012 | |

| Drugs | Chloroquine | S. cerevisiae | Islahudin et al., 2013 |

| Edelfosine | S. cerevisiae | Cuesta-Marbán et al., 2013 | |

| Porphyrin TMpyP4 | S. cerevisiae | Andrew et al., 2013 | |

| FK506 | S. pombe | Ma et al., 2011 | |

| Caffeine | S. pombe | Calvo et al., 2009 | |

| Genotoxicants | Methyl methanesulfonate | S. cerevisiae | Huang et al., 2013b |

| Various | S. cerevisiae | Svensson et al., 2013 | |

| Various | S. cerevisiae | Torres et al., 2013 | |

| Various | S. pombe | Pan et al., 2012 | |

| Other | Acetic acid | S. cerevisiae | Sousa et al., 2013 |

| Hydrolysate | S. cerevisiae | Skerker et al., 2013 | |

| Neonicotinoids | S. cerevisiae | Mattiazzi Ušaj et al., 2013 | |

| Manzamine A | S. cerevisiae | Kallifatidis et al., 2013 | |

| NCI diversity/ mechanistic sets | S. cerevisiae/ S. pombe | Kapitzky et al., 2010 |

A literature search identified recently published S. cerevisiae and S. pombe screens.

Table 2.

Summary of functional toxicological screens in organisms other than yeast.

| Chemical/condition | Organism | Methodology | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clotrimazole | C. albicans | Deletions | Oh et al., 2010a |

| Wide variety of growth conditions and diverse chemical compounds | C. albicans | Deletions | Oh et al., 2010b |

| Paraquat | C. elegans | RNAi | Kim and Sun, 2007 |

| Cell cycle inhibitors | D. melanogaster | RNAi | Eggert et al., 2004 |

| Cell cycle inhibitors | D. rerio | Morpholinos | Murphey et al., 2006 |

| Various media and growth inhibitors | E. coli | Deletions | Warner et al., 2010 |

| Vemurafenib | H. sapiens | CRISPR | Shalem et al., 2014 |

| 6-thioguanine | H. sapiens | CRISPR | Wang et al., 2014 |

| Etoposide | H. sapiens | CRISPR | Wang et al., 2014 |

| Wide range of drugs | H. sapiens | RNAi | reviewed by Berns and Bernards (2012) |

| Ricin | H. sapiens | shRNA | Bassik et al., 2013 |

| 3-bromopyruvate | H. sapiens | Transposon mutagenesis | Birsoy et al., 2013 |

| Tunicamycin | H. sapiens | Transposon mutagenesis | Reiling et al., 2011 |

| 2-amino-6-mercaptopurine | M. musculus | Transposon mutagenesis | Leeb and Wutz, 2011 |

| 6-thioguanine | M. musculus | Transposon mutagenesis | Pettitt et al., 2013 |

| Olaparib | M. musculus | Transposon mutagenesis | Pettitt et al., 2013 |

| Ricin | M. musculus | Transposon mutagenesis | Elling et al., 2011 |

| Wide variety of growth conditions and diverse chemical compounds | S. oneidensis | Deletions | Deutschbauer et al., 2011 |

| Minimal media | S. oneidensis | Deletions | Oh et al., 2010a |

| Plant hydrolysate | Z. mobilis | Deletions | Skerker et al., 2013 |

A literature search identified published screens.

Functional toxicology in yeasts

For many reasons, the eukaryotic budding (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and fission (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) yeasts are ideal models in which to conduct functional toxicological studies. Numerous metabolic and signaling pathways, along with basic cellular processes, are conserved with more complex organisms such as humans. Human homologs have been identified for a large number of yeast genes, with several hundred of the conserved genes linked to disease in humans (Steinmetz et al., 2002; Wood et al., 2002). A long history of genetic manipulation in yeasts confers the ability to selectively target and examine conserved genes and pathways throughout their genomes, facilitating functional analyses. The ease of culture and availability of software resources, molecular protocols, and genetic and physical interaction data collectively bolster the value of yeasts in toxicology.

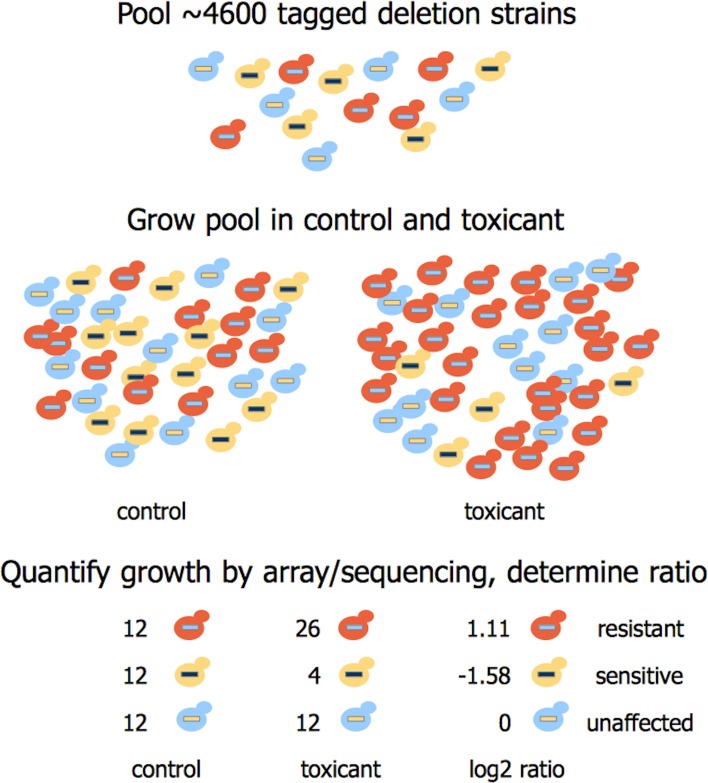

Barcoded mutant collections have been generated in budding (Giaever et al., 1999, 2002) and fission yeast (Kennedy et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012), allowing assessment of individual strain fitness in pooled cultures under selective conditions (reviewed by North and Vulpe, 2010; dos Santos et al., 2012). This technique, known as functional profiling, functional genomics, chemical genomics, or chemical-genetic profiling, can identify the genetic requirements for tolerance to any substance that causes measurable growth inhibition in yeast. Figure 2 demonstrates the screening process, while Table 1 provides a summary of recent functional studies. Homozygous profiling (HOP) utilizes strains deleted for non-essential genes to establish the genetic requirements for chemical tolerance, while haploinsufficiency profiling (HIP) detects strains sensitized to a chemical targeting the product of their corresponding heterozygous locus (for a review, see Smith et al., 2010a). In brief, DNA sequences (“barcodes”) uniquely identifying each deletion strain enable parallel growth analyses with thousands of pooled mutants exposed to a chemical of interest. A PCR amplification of the barcodes and their subsequent quantification via microarray hybridization or sequencing allows for discovery of strains with altered growth in the particular substance. The decreased abundance by mRNA perturbation (dAMP) collection complements heterozygote profiling by destabilizing a gene's mRNA (and thus depleting the encoded protein) via disruption of 3′-untranslated regions (Yan et al., 2008). An additional tool that may benefit functional toxicology is the barcoded yeast overexpression library (Ho et al., 2009; Douglas et al., 2012). Similar to HOP and HIP, this technique enables highly parallel and systematic investigations of overexpression phenotypes in pooled cultures. Finally, a novel “functional variomics” approach utilizes high-complexity random mutagenesis to identify genes conferring drug resistance due to mutations or overexpression (Huang et al., 2013a). The advent of multiplexed high-throughput barcode sequencing of pooled cultures (Han et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2010b) promises a future of expedited and cost efficient functional genomic analyses.

Figure 2.

Overview of functional profiling in yeast. About 4600 deletion strains uniquely identified by DNA sequences (barcodes) are pooled and exposed to a toxicant at multiple doses and generation times (5 or 15). Barcodes are amplified from purified genomic DNA by PCR and counted by hybridization to a microarray or high-throughput sequencing methods. Subsequent analyses of individual strains can confirm susceptibility or resistance to the toxicant.

The functional tools available in yeast provide unmatched resources for inquiries into potential cellular and molecular mechanisms of toxicity. Such analyses have informed functional experimentation in more complex organisms such as zebrafish or human cell lines. For example, Ishizaki et al. (2010) utilized a yeast chemical-genetic screen to reveal that intracellular trafficking defects conferred sensitivity to copper limitation, and further reported that knockdown of zebrafish homologs to these yeast genes sensitized fish to copper-dependent hypopigmentation, a hallmark of copper deficiency in humans. Following identification of the Sas2p histone acetyltransferase as a modulator of arsenite tolerance in yeast, knockdown of its homolog MYST1 in human bladder epithelial cells was found to similarly induce arsenite sensitivity (Jo et al., 2009a,b). Another group demonstrated that the investigational cancer drug elesclomol affected electron transport mutants in yeast and extended their analysis by determining that elesclomol interacted with the electron transport chain in human cells (Blackman et al., 2012). Likewise, a functional screen in yeast identified mitochondrial translation inhibition as the lethality mechanism of the antimicrobial and antileukemic compound tigecycline, and this activity was confirmed in leukemic cells (Skrtić et al., 2011). Finally, Jo et al. (2009a) used yeast to show that a S-adenosylmethionine dependent methyltransferase conferred resistance to various arsenic species, while Ren et al. (2011) showed the corresponding gene in humans (N6AMT1) could metabolize arsenic in human urothelial cells. Harari et al. (2013) expanded upon these studies by demonstrating that N6AMT1 polymorphisms were associated with arsenic methylation in Andean women, and posited that the polymorphisms could be used as susceptibility markers for arsenic toxicity.

Potential for functional toxicology in other fungi and bacteria

The recent development of the TagModule collection (Oh et al., 2010a), building upon the work of Xu et al. (2007), takes advantage of barcoded transposons to extend the yeast DNA barcoding methodology to a variety of microorganisms. In essence, in vitro transposon mutagenesis is utilized to mutagenize a genomic DNA library, and subsequent transformation of barcoded genomic fragments into a compatible unicellular organism allows for genome-wide unbiased screening of chemical-genetic interactions. Akin to the yeast functional process, the barcodes can be amplified from pooled cultures and counted by microarray hybridization or high-throughput sequencing. Oh et al. (2010a) demonstrated the versatility of the TagModule collection by generating tagged mutants in the bacterium Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 and the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. As a proof of principle, the authors identified S. oneidensis mutants with growth deficiencies in minimal media and C. albicans mutants sensitive to the antifungal drug clotrimazole (Oh et al., 2010a). The same group reports on additional haploinsufficiency screens in C. albicans (Oh et al., 2010b) and S. oneidensis (Deutschbauer et al., 2011) encompassing a wide variety of growth conditions and diverse chemical compounds. Furthermore, the method was applied to identify genes important for plant hydrolysate tolerance in Zymomonas mobilis, a bacterium with potential for commercial-scale cellulosic ethanol production (Skerker et al., 2013). By facilitating barcoding of mutant or overexpression collections for pooled functional analyses in a range of organisms, the TagModule system can be a valuable tool for toxicity testing.

Alternative approaches utilizing deletion/overexpression strains, or high-throughput sequencing of tagged transposon mutants may have applications relevant to functional toxicology. A signature-tagged mutagenesis strategy permitted parallel analysis of Cryptococcus neoformans fungal mutants in experimental infections (Liu et al., 2008), while high-throughput sequencing examined the relative quantities of human gut bacterium Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron transposon mutants in wild-type and immunodeficient gnotobiotic mice (Goodman et al., 2009). Relative strain abundance has been quantified in a collection of homozygous C. albicans deletion mutants, albeit in a lower-throughput investigation (Noble et al., 2010) than allowed by the TagModule system (Oh et al., 2010a). Overexpression studies can be conducted in C. albicans, however the available ORFeome is confined to a few hundred genes (Chauvel et al., 2012). Genome-wide deletion libraries have been constructed in Escherichia coli (Baba et al., 2006), Bacillus subtilis (Kobayashi et al., 2003), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Jacobs et al., 2003), with a limited set available in Salmonella enterica (Santiviago et al., 2009). Thousands of specific genetic modifications were simultaneously evaluated to quantify population dynamics in various media and growth inhibitors in E. coli (Warner et al., 2010). It is conceivable that functional toxicological or even pharmaceutical inquiries can be performed using any of these tools and/or organisms.

Functional toxicology in eukaryotes of increased complexity

Overview

Large-scale targeted deletion collections do not currently exist for animal models. Published studies are confined to specific subsets of genes or cellular processes affected by the chemical of interest. Recent advances in knockout technology may make genome-wide functional toxicology possible in complex eukaryotes.

Studies in cell lines

Until recently, the DT40 B lymphocyte chicken cell lines, because of a hyperactive recombination system, represented the only vertebrate system in which both alleles of a gene could be efficiently disrupted. DT40 cells display a stable phenotype, double in a short period (~8 h), and grow in suspension (Yamazoe et al., 2004; Evans et al., 2010). Thus, DT40 are advantageous in the functional and mechanistic screening of various toxicants. Currently, they are used primarily in the study of genotoxicants, as the majority of the cell lines harbor various individual deletions in DNA repair genes (Ridpath et al., 2007; Yamamoto et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2013). Although other cellular components and processes are not represented in the set of mutants, the cells could become another general resource if additional deletions are generated. However, because the cells are not barcoded, multiplexing or parallel growth screens are not possible.

Genome-wide RNA interference (RNAi) screens have become an important tool in drug discovery (Kiefer et al., 2009), and can be readily applied to functional toxicological studies. RNAi methods, first discovered in C. elegans (Fire et al., 1998), exploit existing cellular machinery to destroy the mRNA of a target gene, thus preventing translation and effectively “knocking down” the function of the target gene. RNAi screens in cell lines can be useful to functional toxicology but are experimentally complex, as incomplete knockdown of target genes and off-target effects can complicate execution and analysis (reviewed by North and Vulpe, 2010). The majority of functional genomic applications in human cells rely upon RNAi loss-of-function screens (reviewed by Mullenders and Bernards, 2009). RNAi in Drosophila cell lines has been previously utilized to study cellular toxicity—as examples, Eggert et al. (2004) identified small molecules inhibiting the cell cycle, while Zhang et al. (2010) discovered genes that increased the aggregation of mutant Huntingtin proteins. Barcoded short hairpin RNA (shRNA—a method to accomplish RNAi) libraries enable identification of shRNAs that elicit a specific phenotype under toxicant selection. The relative abundance of barcodes in control and treated populations can be measured by hybridization to microarrays (Mullenders and Bernards, 2009) or sequencing (Kimura et al., 2008; Sims et al., 2011). This method is efficient at detecting shRNAs that increase fitness but cannot always discover shRNAs that decrease viability, and furthermore, the process is lengthy and requires significant optimization (Sims et al., 2011). Nevertheless, RNAi-based screens have uncovered human genes whose suppression confers resistance to a wide range of drugs (reviewed by Berns and Bernards, 2012). Finally, a two-stage shRNA screen identified mammalian genetic interactions underlying ricin susceptibility (Bassik et al., 2013).

As noted above, in diploid cells, both chromosomal copies of the gene of interest must be targeted to fully abrogate gene function, an inefficient and laborious step wise process. Thus, an exciting development for the field of functional toxicology is the identification of haploid mouse (Leeb and Wutz, 2011) and near haploid human (Carette et al., 2009) cell lines. Transposon mutagenesis in mouse haploid embryonic stem cells has identified genes required for resistance to 2-amino-6-mercaptopurine (Leeb and Wutz, 2011), the chemotherapeutic 6-thioguanine and the PARP 1/2 inhibitor olaparib (Pettitt et al., 2013), and the bioweapon ricin (Elling et al., 2011). Similarly, the human cells are a derivative of a chronic myeloid leukemia cell line haploid for all chromosomes except chromosome 8. Insertional mutagenesis generated null alleles that have been screened for resistance to host factors used by pathogens (Carette et al., 2009, 2011a; Jae et al., 2013), the cancer drug candidate 3-bromopyruvate (Birsoy et al., 2013), and the ER stressor tunicamycin (Reiling et al., 2011). Especially encouraging is the use of deep sequencing to examine millions of mutant alleles via selection and sequencing of pools of cells (Carette et al., 2011b), an improvement over the laborious analyses of individual clones. These systems promise to advance chemical-genetic studies in human cell lines.

The toolbox for functional toxicology in mammalian cells is expanding. The TALE nuclease architecture has been utilized to regulate mammalian genes and engineer deletions within the endogenous human NTF3 and CCR5 genes (Miller et al., 2011). Of particular note is the development of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, which may allow for efficient, large-scale, loss of function screening in mammalian cells (Shalem et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014). The strategy utilizes a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to cleave target DNA sequences. With lentiviral delivery of a CRISPR-Cas9 knockout library, sgRNAs serve as distinct barcodes that can be counted via high-throughput sequencing to perform negative and positive selection screening in human cells. One study identified human genes essential for viability in cancer cells, and also discovered human genes necessary for survival in vemurafenib, a RAF inhibitor (Shalem et al., 2014). Others utilized the method in human cell lines to identify genes required for resistance to the nucleotide analog 6-thioguanine and the DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide (Wang et al., 2014). The simplification and expedition of screening and deletion processes in mammalian cell lines will undoubtedly have considerable ramifications for functional toxicology.

Studies in whole organisms

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has been exploited in forward genetic and RNAi screens (reviewed by Leung et al., 2008). Following a round of mutagenesis and selection in a toxicant, next generation sequencing can identify individual C. elegans mutants (Doitsidou et al., 2010). Various groups have utilized limited RNAi screens in nematodes to discover genes that, when silenced, confer chemical resistance or susceptibility. Examples include investigations with the herbicide paraquat (Kim and Sun, 2007), whereas gene expression analyses informed RNAi studies with cadmium (Cui et al., 2007) and PCB-52 (Menzel et al., 2007). Although many C. elegans homozygous deletion mutants are available through the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, high-throughput methods to assess survival of all strains at once (in a manner similar to yeast functional profiling) are not available due to the lack of barcode sequences in the mutants. These mutants may prove useful in follow-up analyses of conserved genes and pathways identified by chemical genetic screens in yeasts or bacteria.

Functional toxicology in more complex whole organisms is not straightforward, but new technologies offer encouragement for the future. The zebrafish model is useful in large-scale in vivo genetic and chemical studies (Pardo-Martin et al., 2010). Forward chemical genetic screens in zebrafish have identified small molecules inhibiting the cell cycle (Murphey et al., 2006) and examined genes involved in copper-dependent hypopigmentation (Ishizaki et al., 2010). An emerging multidimensional high-throughput in vivo approach in embryonic zebrafish, where a wide variety of developmental morphology and neurotoxicity endpoints are rapidly screened to understand chemical toxicity (Truong et al., 2014), indicates that the field of toxicology is advancing in the study of whole organisms. Combining this type of screening strategy with other methodologies such as RNAi, although not currently performed on a large scale basis, could provide additional information related to chemical mechanisms of toxicity.

Traditional approaches for generation of knockout animals in mice remains a time-consuming and costly process that limits its utility in functional toxicology to confirmatory analysis.

However, new systems facilitating deletions in animals can be used to selectively target genes for editing or mutagenesis (Miller et al., 2011; Wilkinson and Wiedenheft, 2014). For example, the site-specific endonuclease TALE-nuclease was used to mediate mutagenesis in mouse zygotes, producing animals with genetic knockouts of the progesterone immunomodulatory binding factor 1 and selenoprotein W, muscle 1 (Sung et al., 2013). The European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis program (EUCOMM) and the Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP) are two large-scale mouse phenotyping initiatives that aim to provide libraries of knockout animals for further study (Ayadi et al., 2012). The focus of these efforts, however, has been on phenotypic analysis of the mutants rather than the intersection between chemical exposure and genetic background. Knockouts created by these methodologies could expedite analyses of conserved toxicant mechanisms in a variety of animal models. At the present, however, more reasonable is the use of individual animal knockouts or knockdowns to confirm results acquired in less complex systems such as yeast.

Application of computational analyses to functional toxicology

Inherent in high-throughput functional toxicology methods is the use of computational analyses to decipher toxicant mechanisms of action. Various studies have utilized overenrichment or Cytoscape software (Shannon et al., 2003) to uncover yeast genetic networks affected by a toxicant (Zhou et al., 2009; North et al., 2011; Gaytán et al., 2013a,b; Kaiser et al., 2013). Others, by integrating data from many distinct yeast chemical-genetic datasets, have assembled chemical-phenotype networks that helped identify potential effects elicited by various compounds (Venancio et al., 2010). Without computational analyses, the high-throughput approaches in zebrafish (Truong et al., 2014) or human cell lines (Shalem et al., 2014) would not be possible.

Challenges with functional toxicology

For a variety of reasons, functional toxicology has its limitations in the range of organisms discussed within this review. Less complex organisms such as yeasts, other fungi, and bacteria possess P450 enzymes (Käppeli, 1986; Urlacher et al., 2004; McLean et al., 2005), but their role in toxicant metabolism is limited. To better understand chemical toxicity to humans, toxicant activation or deactivation may be catalyzed in these experiments by adding S-9 human liver microsomes. Additionally, in unicellular organisms, cell lines, and less complex eukaryotes such as C. elegans, one is unable to examine a toxicant's target organs or systemic effects. The discovery of human disease models through orthologous phenotypes may address these concerns. For example, McGary et al. (2010) proposed a yeast model for angiogenesis defects and a C. elegans model for breast cancer, based upon analyses of genes shared between the model system and an organism displaying the disease under study. Similar analyses of functional data from unicellular organisms, cell lines, and C. elegans may reveal toxicant mechanisms associated with more complex biological processes.

In whole organisms, throughput is the major barrier to progress in functional toxicology. In yeasts and bacteria, barcoded systems allow for the high-throughput examination of thousands of deletion mutants in parallel (Giaever et al., 2002; Oh et al., 2010a). The lack of such methods in whole organisms such as zebrafish or rodent models diminishes throughput, and complicates systematic identification of genes required for resistance to a toxicant. Until high-throughput screens are devised in whole organisms, such systems are invaluable in extending or confirming results gathered in yeasts or bacteria.

The future of functional toxicology

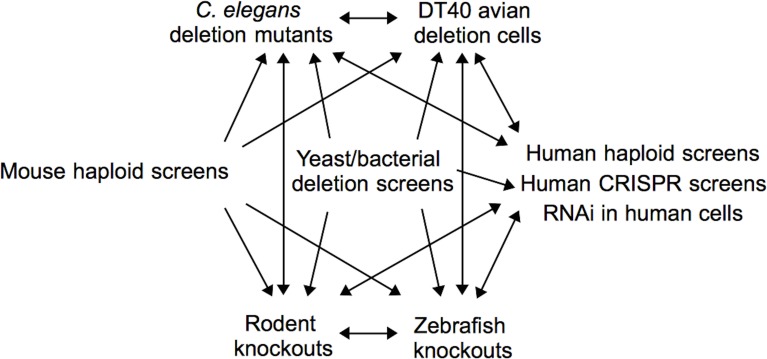

Functional toxicological screening methods, i.e., those that identify genetic requirements for chemical tolerance, are powerful, unbiased tools which provide unique mechanistic insights in the field of toxicology. High-throughput screens of chemicals of concern or unknown toxicity will allow toxicologists to formulate hypotheses related to their corresponding mechanisms and pathways of toxicity. Automation and deep parallel sequencing technologies will unquestionably increase the throughput of functional techniques, but extensive computational resources and knowledge will be required to implement screening systems and analyze the resulting data. Integration of functional assays across a variety of organisms can identify conserved modes of toxicity and direct studies most relevant to human health (Figure 3). The field of functional toxicology is primed to assist toxicologists meet the need for enhanced chemical toxicity testing.

Figure 3.

Integration of functional assays across organisms. One can use functional tools across a variety of organisms, depending upon the model under study and the end goal of the investigation. For example, one may start with a screen in yeast, mouse, or human cells and extend the analyses to whole organisms such as zebrafish or rodents. Alternatively, one may start with zebrafish mutants or DT40 avian deletion cells and perform follow-up experimentation in human cells or other whole organisms. The many possibilities can advance the future of toxicity testing.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vanessa De La Rosa and Mani Tagmount for helpful discussions.

References

- Andersen M. E., Krewski D. (2010). The vision of toxicity testing in the 21st century: moving from discussion to action. Toxicol. Sci. 117, 17–24 10.1093/toxsci/kfq188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew E. J., Merchan S., Lawless C., Banks A. P., Wilkinson D. J., Lydall D. (2013). Pentose phosphate pathway function affects tolerance to the G-quadruplex binder TMPyP4. PLoS ONE 8:e66242 10.1371/journal.pone.0066242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayadi A., Birling M.-C., Bottomley J., Bussell J., Fuchs H., Fray M., et al. (2012). Mouse large-scale phenotyping initiatives: overview of the European Mouse Disease Clinic (EUMODIC) and of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Mouse Genetics Project. Mamm. Genome. 23, 600–610 10.1007/s00335-012-9418-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad G. K., Singh V., Golla U., Tomar R. S. (2013). Depletion of cellular iron by curcumin leads to alteration in histone acetylation and degradation of Sml1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 8:e59003 10.1371/journal.pone.0059003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T., Ara T., Hasegawa M., Takai Y., Okumura Y., Baba M., et al. (2006). Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 20060008. 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassik M. C., Kampmann M., Lebbink R. J., Wang S., Hein M. Y., Poser I., et al. (2013). A systematic mammalian genetic interaction map reveals pathways underlying ricin susceptibility. Cell 152, 909–922 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns K., Bernards R. (2012). Understanding resistance to targeted cancer drugs through loss of function genetic screens. Drug Resist. Updat. 15, 268–275 10.1016/j.drup.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birsoy K., Wang T., Possemato R., Yilmaz O. H., Koch C. E., Chen W. W., et al. (2013). MCT1-mediated transport of a toxic molecule is an effective strategy for targeting glycolytic tumors. Nat. Genet. 45, 104–108 10.1038/ng.2471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman R. K., Cheung-Ong K., Gebbia M., Proia D. A., He S., Kepros J., et al. (2012). Mitochondrial electron transport is the cellular target of the oncology drug elesclomol. PLoS ONE 7:e29798 10.1371/journal.pone.0029798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie D., Parvizi P., Duncan D., Nelson C. J., Fyles T. M. (2013). Chemical-genetic identification of the biochemical targets of polyalkyl guanidinium biocides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 4359–4366 10.1039/c3ob40593a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo I. A., Gabrielli N., Iglesias-Baena I., García-Santamarina S., Hoe K.-L., Kim D. U., et al. (2009). Genome-wide screen of genes required for caffeine tolerance in fission yeast. PLoS ONE 4:e6619 10.1371/journal.pone.0006619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette J. E., Guimaraes C. P., Varadarajan M., Park A. S., Wuethrich I., Godarova A., et al. (2009). Haploid genetic screens in human cells identify host factors used by pathogens. Science 326, 1231–1235 10.1126/science.1178955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette J. E., Guimaraes C. P., Wuethrich I., Blomen V. A., Varadarajan M., Sun C., et al. (2011b). Global gene disruption in human cells to assign genes to phenotypes by deep sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 542–546 10.1038/nbt.1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette J. E., Raaben M., Wong A. C., Herbert A. S., Obernosterer G., Mulherkar N., et al. (2011a). Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1. Nature 477, 340–343 10.1038/nature10348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvel M., Nesseir A., Cabral V., Znaidi S., Goyard S., Bachellier-Bassi S., et al. (2012). A versatile overexpression strategy in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans: identification of regulators of morphogenesis and fitness. PLoS ONE 7:e45912 10.1371/journal.pone.0045912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.-R., Hale D. C., Ciolek P. J., Runge K. W. (2012). Generation and analysis of a barcode-tagged insertion mutant library in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. BMC Genomics 13:161 10.1186/1471-2164-13-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta-Marbán A., Botet J., Czyz O., Cacharro L. M., Gajate C., Hornillos V., et al. (2013). Drug uptake, lipid rafts and vesicle trafficking modulate resistance to an anticancer lysophosphatidylcholine analogue in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8405–8418 10.1074/jbc.M112.425769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., McBride S. J., Boyd W. A., Alper S., Freedman J. H. (2007). Toxicogenomic analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans reveals novel genes and pathways involved in the resistance to cadmium toxicity. Genome Biol. 8, R122 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvishi E., Omidi M., Bushehri A. A., Golshani A., Smith M. L. (2013b). Thymol antifungal mode of action involves telomerase inhibition. Med. Mycol. 8, 826–834 10.3109/13693786.2013.795664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvishi E., Omidi M., Bushehri A. A. S., Golshani A., Smith M. L. (2013a). The antifungal eugenol perturbs dual aromatic and branched-chain amino Acid permeases in the cytoplasmic membrane of yeast. PLoS ONE 8:e76028 10.1371/journal.pone.0076028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutschbauer A., Price M. N., Wetmore K. M., Shao W., Baumohl J. K., Xu Z., et al. (2011). Evidence-based annotation of gene function in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 using genome-wide fitness profiling across 121 conditions. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002385 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doitsidou M., Poole R. J., Sarin S., Bigelow H., Hobert O. (2010). C. elegans mutant identification with a one-step whole-genome-sequencing and SNP mapping strategy. PLoS ONE 5:e15435 10.1371/journal.pone.0015435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos S. C., Teixeira M. C., Cabrito T. R., S.á-Correia I. (2012). Yeast toxicogenomics: genome-wide responses to chemical stresses with impact in environmental health, pharmacology, and biotechnology. Front. Genet. 3:63 10.3389/fgene.2012.00063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas A. C., Smith A. M., Sharifpoor S., Yan Z., Durbic T., Heisler L. E., et al. (2012). Functional analysis with a barcoder yeast gene overexpression system. G3 (Bethesda) 2, 1279–1289 10.1534/g3.112.003400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert U. S., Kiger A. A., Richter C., Perlman Z. E., Perrimon N., Mitchison T. J., et al. (2004). Parallel chemical genetic and genome-wide RNAi screens identify cytokinesis inhibitors and targets. PLoS Biol. 2:e379 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elling U., Taubenschmid J., Wirnsberger G., O'Malley R., Demers S.-P., Vanhaelen Q., et al. (2011). Forward and reverse genetics through derivation of haploid mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 9, 563–574 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T. J., Yamamoto K. N., Hirota K., Takeda S. (2010). Mutant cells defective in DNA repair pathways provide a sensitive high-throughput assay for genotoxicity. DNA Repair (Amst.) 9, 1292–1298 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Hu L., Zhou X., Jaiseng W., Zhang B., Takami T., et al. (2012). A genome-wide screen in Schizosaccharomyces pombe for genes affecting the sensitivity of antifungal drugs that target ergosterol biosynthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 1949–1959 10.1128/AAC.05126-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A., Xu S., Montgomery M. K., Kostas S. A., Driver S. E., Mello C. C. (1998). Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391, 806–811 10.1038/35888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván Márquez I., Akuaku J., Cruz I., Cheetham J., Golshani A., Smith M. L. (2013). Disruption of protein synthesis as antifungal mode of action by chitosan. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 164, 108–112 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatzidou E. T., Zira A. N., Theocharis S. E. (2007). Toxicogenomics: a pivotal piece in the puzzle of toxicological research. J. Appl. Toxicol. 27, 302–309 10.1002/jat.1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaytán B. D., Loguinov A. V., De La Rosa V. Y., Lerot J.-M., Vulpe C. D. (2013a). Functional genomics indicates yeast requires Golgi/ER transport, chromatin remodeling, and DNA repair for low dose DMSO tolerance. Front. Genet. 4:154 10.3389/fgene.2013.00154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaytán B. D., Loguinov A. V., Lantz S. R., Lerot J.-M., Denslow N. D., Vulpe C. D. (2013b). Functional profiling discovers the dieldrin organochlorinated pesticide affects leucine availability in yeast. Toxicol. Sci. 132, 347–358 10.1093/toxsci/kft018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaytán B. D., Loguinov A. V., Peñate X., Lerot J.-M., Chávez S., Denslow N. D., et al. (2013c). A genome-wide screen identifies yeast genes required for tolerance to technical toxaphene, an organochlorinated pesticide mixture. PLoS ONE 8:e81253 10.1371/journal.pone.0081253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever G., Chu A. M., Ni L., Connelly C., Riles L., Véronneau S., et al. (2002). Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418, 387–391 10.1038/nature00935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever G., Shoemaker D. D., Jones T. W., Liang H., Winzeler E. A., Astromoff A., et al. (1999). Genomic profiling of drug sensitivities via induced haploinsufficiency. Nat. Genet. 21, 278–283 10.1038/6791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Ramos D., van den Broek M., van Maris A. J., Pronk J. T., Daran J.-M. G. (2013). Genome-scale analyses of butanol tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveal an essential role of protein degradation. Biotechnol. Biofuels 6, 48 10.1186/1754-6834-6-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. L., McNulty N. P., Zhao Y., Leip D., Mitra R. D., Lozupone C. A., et al. (2009). Identifying genetic determinants needed to establish a human gut symbiont in its habitat. Cell Host Microbe 6, 279–289 10.1016/j.chom.2009.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadeh H. K., Amin R. P., Paules R. S., Afshari C. A. (2002). An overview of toxicogenomics. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 4, 45–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han T. X., Xu X.-Y., Zhang M.-J., Peng X., Du L.-L. (2010). Global fitness profiling of fission yeast deletion strains by barcode sequencing. Genome Biol. 11, R60 10.1186/gb-2010-11-6-r60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari F., Engström K., Concha G., Colque G., Vahter M., Broberg K. (2013). N-6-adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase 1 (N6AMT1) polymorphisms and arsenic methylation in Andean women. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, 797–803 10.1289/ehp.1206003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C. H., Magtanong L., Barker S. L., Gresham D., Nishimura S., Natarajan P., et al. (2009). A molecular barcoded yeast ORF library enables mode-of-action analysis of bioactive compounds. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 369–377 10.1038/nbt.1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Piening B. D., Paulovich A. G. (2013b). The preference for error-free or error-prone postreplication repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae exposed to low-dose methyl methanesulfonate is cell cycle dependent. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 1515–1527 10.1128/MCB.01392-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Chen K., Zhang J., Li Y., Wang H., Cui D., et al. (2013a). A functional variomics tool for discovering drug-resistance genes and drug targets. Cell Rep. 3, 577–585 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki H., Spitzer M., Wildenhain J., Anastasaki C., Zeng Z., Dolma S., et al. (2010). Combined zebrafish-yeast chemical-genetic screens reveal gene-copper-nutrition interactions that modulate melanocyte pigmentation. Dis Model Mech. 3, 639–651 10.1242/dmm.005769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islahudin F., Khozoie C., Bates S., Ting K.-N., Pleass R. J., Avery S. V. (2013). Cell-wall perturbation sensitizes fungi to the antimalarial drug chloroquine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3889–3896 10.1128/AAC.00478-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M. A., Alwood A., Thaipisuttikul I., Spencer D., Haugen E., Ernst S., et al. (2003). Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14339–14344 10.1073/pnas.2036282100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jae L. T., Raaben M., Riemersma M., van Beusekom E., Blomen V. A., Velds A., et al. (2013). Deciphering the glycosylome of dystroglycanopathies using haploid screens for lassa virus entry. Science 340, 479–483 10.1126/science.1233675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo W. J., Loguinov A., Wintz H., Chang M., Smith A. H., Kalman D., et al. (2009a). Comparative functional genomic analysis identifies distinct and overlapping sets of genes required for resistance to monomethylarsonous acid (MMAIII) and arsenite (AsIII) in yeast. Toxicol Sci. 111, 424–436 10.1093/toxsci/kfp162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo W. J., Ren X., Chu F., Aleshin M., Wintz H., Burlingame A., et al. (2009b). Acetylated H4K16 by MYST1 protects UROtsa cells from arsenic toxicity and is decreased following chronic arsenic exposure. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 241, 294–302 10.1016/j.taap.2009.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson R., Richard A., Dix D. J., Houck K., Martin M., Kavlock R., et al. (2009). The toxicity data landscape for environmental chemicals. Environ. Health Perspect. 117, 685–695 10.1289/ehp.0800168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C. J. O., Grötzinger S. W., Eckl J. M., Papsdorf K., Jordan S., Richter K. (2013). A network of genes connects polyglutamine toxicity to ploidy control in yeast. Nat. Commun. 4, 1571 10.1038/ncomms2575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallifatidis G., Hoepfner D., Jaeg T., Guzmán E. A., Wright A. E. (2013). The marine natural product manzamine a targets vacuolar ATPases and inhibits autophagy in pancreatic cancer cells. Mar. Drugs 11, 3500–3516 10.3390/md11093500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitzky L., Beltrao P., Berens T. J., Gassner N., Zhou C., Wüster A., et al. (2010). Cross-species chemogenomic profiling reveals evolutionarily conserved drug mode of action. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 451 10.1038/msb.2010.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käppeli O. (1986). Cytochromes P-450 of yeasts. Microbiol. Rev. 50, 244–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P. J., Vashisht A. A., Hoe K.-L., Kim D.-U., Park H.-O., Hayles J., et al. (2008). A genome-wide screen of genes involved in cadmium tolerance in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Toxicol. Sci. 106, 124–139 10.1093/toxsci/kfn153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer J., Yin H. H., Que Q. Q., Mousses S. (2009). High-throughput siRNA screening as a method of perturbation of biological systems and identification of targeted pathways coupled with compound screening. Methods Mol. Biol. 563, 275–287 10.1007/978-1-60761-175-2_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.-U., Hayles J., Kim D., Wood V., Park H.-O., Won M., et al. (2010). Analysis of a genome-wide set of gene deletions in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 617–623 10.1038/nbt.1628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Sun H. (2007). Functional genomic approach to identify novel genes involved in the regulation of oxidative stress resistance and animal lifespan. Aging Cell. 6, 489–503 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00302.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura J., Nguyen S. T., Liu H., Taira N., Miki Y., Yoshida K. (2008). A functional genome-wide RNAi screen identifies TAF1 as a regulator for apoptosis in response to genotoxic stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 5250–5259 10.1093/nar/gkn506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Ehrlich S. D., Albertini A., Amati G., Andersen K. K., Arnaud M., et al. (2003). Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4678–4683 10.1073/pnas.0730515100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Liu X., Takeda S., Choi K. (2013). Genotoxic potentials and related mechanisms of bisphenol A and other bisphenol compounds: a comparison study employing chicken DT40 cells. Chemosphere 93, 434–440 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb M., Wutz A. (2011). Derivation of haploid embryonic stem cells from mouse embryos. Nature 479, 131–134 10.1038/nature10448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung M. C. K., Williams P. L., Benedetto A., Au C., Helmcke K. J., Aschner M., et al. (2008). Caenorhabditis elegans: an emerging model in biomedical and environmental toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 106, 5–28 10.1093/toxsci/kfn121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis M., Bhatt S., Schoenly N. E., Lee A. Y., Nislow C., Bobek L. A. (2013). Chemical genomic screening of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae genomewide mutant collection reveals genes required for defense against four antimicrobial peptides derived from proteins found in human saliva. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 840–847 10.1128/AAC.01439-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu O. W., Chun C. D., Chow E. D., Chen C., Madhani H. D., Noble S. M. (2008). Systematic genetic analysis of virulence in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell 135, 174–188 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Jiang W., Liu Q., Ryuko S., Kuno T. (2011). Genome-wide screening for genes associated with FK506 sensitivity in fission yeast. PLoS ONE 6:e23422 10.1371/journal.pone.0023422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiazzi Ušaj M., Kaferle P., Toplak A., Trebše P., Petrovič U. (2013). Determination of toxicity of neonicotinoids on the genome level using chemogenomics in yeast. Chemosphere 104, 91–96 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGary K. L., Park T. J., Woods J. O., Cha H. J., Wallingford J. B., Marcotte E. M. (2010). Systematic discovery of nonobvious human disease models through orthologous phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 6544–6549 10.1073/pnas.0910200107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean K. J., Sabri M., Marshall K. R., Lawson R. J., Lewis D. G., Clift D., et al. (2005). Biodiversity of cytochrome P450 redox systems. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33, 796–801 10.1042/BST0330796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel R., Yeo H. L., Rienau S., Li S., Steinberg C. E. W., Stürzenbaum S. R. (2007). Cytochrome P450s and short-chain dehydrogenases mediate the toxicogenomic response of PCB52 in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Mol. Biol. 370, 1–13 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. C., Tan S., Qiao G., Barlow K. A., Wang J., Xia D. F., et al. (2011). A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 143–148 10.1038/nbt.1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullenders J., Bernards R. (2009). Loss-of-function genetic screens as a tool to improve the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Oncogene 28, 4409–4420 10.1038/onc.2009.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphey R. D., Stern H. M., Straub C. T., Zon L. I. (2006). A chemical genetic screen for cell cycle inhibitors in zebrafish embryos. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 68, 213–219 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00439.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble S. M., French S., Kohn L. A., Chen V., Johnson A. D. (2010). Systematic screens of a Candida albicans homozygous deletion library decouple morphogenetic switching and pathogenicity. Nat. Genet. 42, 590–598 10.1038/ng.605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North M., Tandon V. J., Thomas R., Loguinov A., Gerlovina I., Hubbard A. E., et al. (2011). Genome-wide functional profiling reveals genes required for tolerance to benzene metabolites in yeast. PLoS ONE 6:e24205 10.1371/journal.pone.0024205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North M., Vulpe C. D. (2010). Functional toxicogenomics: mechanism-centered toxicology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 11, 4796–4813 10.3390/ijms11124796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC of the National Academies. (2007). Committee on toxicity testing and assessment of environmental agents, in Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Oh J., Fung E., Price M. N., Dehal P. S., Davis R. W., Giaever G., et al. (2010a). A universal TagModule collection for parallel genetic analysis of microorganisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e146 10.1093/nar/gkq419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J., Fung E., Schlecht U., Davis R. W., Giaever G., St Onge R. P., et al. (2010b). Gene annotation and drug target discovery in Candida albicans with a tagged transposon mutant collection. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001140 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., Lei B., Zhou N., Feng B., Yao W., Zhao X., et al. (2012). Identification of novel genes involved in DNA damage response by screening a genome-wide Schizosaccharomyces pombe deletion library. BMC Genomics 13:662 10.1186/1471-2164-13-662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Martin C., Chang T.-Y., Koo B. K., Gilleland C. L., Wasserman S. C., Yanik M. F. (2010). High-throughput in vivo vertebrate screening. Nat. Methods 7, 634–636 10.1038/nmeth.1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt S. J., Rehman F. L., Bajrami I., Brough R., Wallberg F., Kozarewa I., et al. (2013). A genetic screen using the PiggyBac transposon in haploid cells identifies Parp1 as a mediator of olaparib toxicity. PLoS ONE 8:e61520 10.1371/journal.pone.0061520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quek N. C. H., Matthews J. H., Bloor S. J., Jones D. A., Bircham P. W., Heathcott R. W., et al. (2013). The novel equisetin-like compound, TA-289, causes aberrant mitochondrial morphology which is independent of the production of reactive oxygen species in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biosyst. 9, 2125–2133 10.1039/c3mb70056a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiling J. H., Clish C. B., Carette J. E., Varadarajan M., Brummelkamp T. R., Sabatini D. M. (2011). A haploid genetic screen identifies the major facilitator domain containing 2A (MFSD2A) transporter as a key mediator in the response to tunicamycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 11756–11765 10.1073/pnas.1018098108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Aleshin M., Jo W. J., Dills R., Kalman D. A., Vulpe C. D., et al. (2011). Involvement of N-6 adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase 1 (N6AMT1) in arsenic biomethylation and its role in arsenic-induced toxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 771–777 10.1289/ehp.1002733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridpath J. R., Nakamura A., Tano K., Luke A. M., Sonoda E., Arakawa H., et al. (2007). Cells deficient in the FANC/BRCA pathway are hypersensitive to plasma levels of formaldehyde. Cancer Res. 67, 11117–11122 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryuko S., Ma Y., Ma N., Sakaue M., Kuno T. (2012). Genome-wide screen reveals novel mechanisms for regulating cobalt uptake and detoxification in fission yeast. Mol. Genet. Genomics 287, 651–662 10.1007/s00438-012-0705-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiviago C. A., Reynolds M. M., Porwollik S., Choi S.-H., Long F., Andrews-Polymenis H. L., et al. (2009). Analysis of pools of targeted Salmonella deletion mutants identifies novel genes affecting fitness during competitive infection in mice. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000477 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalem O., Sanjana N. E., Hartenian E., Shi X., Scott D. A., Mikkelsen T. S., et al. (2014). Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 343, 84–87 10.1126/science.1247005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., et al. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons S. O., Fan C.-Y., Ramabhadran R. (2009). Cellular stress response pathway system as a sentinel ensemble in toxicological screening. Toxicol. Sci. 111, 202–225 10.1093/toxsci/kfp140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims D., Mendes-Pereira A. M., Frankum J., Burgess D., Cerone M.-A., Lombardelli C., et al. (2011). High-throughput RNA interference screening using pooled shRNA libraries and next generation sequencing. Genome Biol. 12, R104 10.1186/gb-2011-12-10-r104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerker J. M., Leon D., Price M. N., Mar J. S., Tarjan D. R., Wetmore K. M., et al. (2013). Dissecting a complex chemical stress: chemogenomic profiling of plant hydrolysates. Mol. Syst. Biol. 9, 674 10.1038/msb.2013.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrtić M., Sriskanthadevan S., Jhas B., Gebbia M., Wang X., Wang Z., et al. (2011). Inhibition of mitochondrial translation as a therapeutic strategy for human acute myeloidleukemia. Cancer Cell. 20, 674–688 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. M., Ammar R., Nislow C., Giaever G. (2010a). A survey of yeast genomic assays for drug and target discovery. Pharmacol Ther. 127, 156–164 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. M., Heisler L. E., St.Onge R. P., Farias-Hesson E., Wallace I. M., Bodeau J., et al. (2010b). Highly-multiplexed barcode sequencing: an efficient method for parallel analysis of pooled samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e142 10.1093/nar/gkq368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. R., Boenzli M. G., Hindagolla V., Ding J., Miller J. M., Hutchison J. E., et al. (2013). Identification of gold nanoparticle-resistant mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae suggests a role for respiratory metabolism in mediating toxicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 728–733 10.1128/AEM.01737-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa M., Duarte A. M., Fernandes T. R., Chaves S. R., Pacheco A., Leão C., et al. (2013). Genome-wide identification of genes involved in the positive and negative regulation of acetic acid-induced programmed cell death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genomics 14:838 10.1186/1471-2164-14-838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz L. M., Scharfe C., Deutschbauer A. M., Mokranjac D., Herman Z. S., Jones T., et al. (2002). Systematic screen for human disease genes in yeast. Nat. Genet. 31, 400–404 10.1038/ng929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung Y. H., Baek I.-J., Kim D. H., Jeon J., Lee J., Lee K., et al. (2013). Knockout mice created by TALEN-mediated gene targeting. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 23–24 10.1038/nbt.2477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J. P., Quirós Pesudo L., McRee S. K., Adeleye Y., Carmichael P., Samson L. D. (2013). Genomic phenotyping by barcode sequencing broadly distinguishes between alkylating agents, oxidizing agents, and non-genotoxic agents, and reveals a role for aromatic amino acids in cellular recovery after quinone exposure. PLoS ONE 8:e73736 10.1371/journal.pone.0073736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres N. P., Lee A. Y., Giaever G., Nislow C., Brown G. W. (2013). A high-throughput yeast assay identifies synergistic drug combinations. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 11, 299–307 10.1089/adt.2012.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troppens D. M., Dmitriev R. I., Papkovsky D. B., O'Gara F., Morrissey J. P. (2013). Genome-wide investigation of cellular targets and mode of action of the antifungal bacterial metabolite 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 13, 322–334 10.1111/1567-1364.12037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong L., Reif D. M., St Mary L., Geier M. C., Truong H. D., Tanguay R. L. (2014). Multidimensional in vivo hazard assessment using zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 137, 212–233 10.1093/toxsci/kft235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun N. M., O'Doherty P. J., Perrone G. G., Bailey T. D., Kersaitis C., Wu M. J. (2013). Disulfide stress-induced aluminium toxicity: molecular insights through genome-wide screening of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metallomics. 5, 1068–1075 10.1039/c3mt00083d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urlacher V. B., Lutz-Wahl S., Schmid R. D. (2004). Microbial P450 enzymes in biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64, 317–325 10.1007/s00253-003-1514-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA. (2005). How Can EPA More Efficiently Identify Potential Risks and Facilitate Risk Reduction Decision for Non-HPV Existing Chemicals? Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; National Pollution Prevention and Toxics Advisory Committee; Broader Issues Work Group; Available online at: http://epa.gov/oppt/npptac/pubs/finaldraftnonhpvpaper051006.pdf (Accessed July 1 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Venancio T. M., Balaji S., Aravind L. (2010). High-confidence mapping of chemical compounds and protein complexes reveals novel aspects of chemical stress response in yeast. Mol. Biosyst. 6, 175–181 10.1039/b911821g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Wei J. J., Sabatini D. M., Lander E. S. (2014). Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science 343, 80–84 10.1126/science.1246981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner J. R., Reeder P. J., Karimpour-Fard A., Woodruff L. B. A., Gill R. T. (2010). Rapid profiling of a microbial genome using mixtures of barcoded oligonucleotides. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 856–862 10.1038/nbt.1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R., Wiedenheft B. (2014). A CRISPR method for genome engineering. F1000Prime Rep. 6, 3 10.12703/P6-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. P., Chia D. A., Ehlers B. C. (2006). Green chemistry in California: a framework for leadership in chemicals policy and innovation. New Solut. 16, 365–372 10.2190/9584-1330-1647-136P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. P., Schwarzman M. R. (2009). Toward a new U.S. chemicals policy: rebuilding the foundation to advance new science, green chemistry, and environmental health. Environ. Health Perspect. 117, 1202–1209 10.1289/ehp.0800404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood V., Gwilliam R., Rajandream M.-A., Lyne M., Lyne R., Stewart A., et al. (2002). The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature 415, 871–880 10.1038/nature724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Jiang B., Ketela T., Lemieux S., Veillette K., Martel N., et al. (2007). Genome-wide fitness test and mechanism-of-action studies of inhibitory compounds in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 3:e92 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K. N., Hirota K., Kono K., Takeda S., Sakamuru S., Xia M., et al. (2011). Characterization of environmental chemicals with potential for DNA damage using isogenic DNA repair-deficient chicken DT40 cell lines. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 52, 547–561 10.1002/em.20656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazoe M., Sonoda E., Hochegger H., Takeda S. (2004). Reverse genetic studies of the DNA damage response in the chicken B lymphocyte line DT40. DNA Repair (Amst.) 3, 1175–1185 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z., Costanzo M., Heisler L. E., Paw J., Kaper F., Andrews B. J., et al. (2008). Yeast Barcoders: a chemogenomic application of a universal donor-strain collection carrying bar-code identifiers. Nat. Methods 5, 719–725 10.1038/nmeth.1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Liu N., Ma X., Jiang L. (2013). The transcriptional control machinery as well as the cell wall integrity and its regulation are involved in the detoxification of the organic solvent dimethyl sulfoxide in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 13, 200–218 10.1111/1567-1364.12022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Binari R., Zhou R., Perrimon N. (2010). A genome-wide RNA interference screen for modifiers of aggregates formation by mutant Huntingtin in Drosophila. Genetics 184, 1165–1179 10.1534/genetics.109.112516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Arita A., Ellen T. P., Liu X., Bai J., Rooney J. P., et al. (2009). A genome-wide screen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals pathways affected by arsenic toxicity. Genomics 94, 294–307 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Ma Y., Fang Y., Gerile W., Jaiseng W., Yamada Y., et al. (2013). A genome-wide screening of potential target genes to enhance the antifungal activity of micafungin in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. PLoS ONE 8:e65904 10.1371/journal.pone.0065904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]