Abstract

Background

Epidemiological evidence has suggested a link between beta2‐agonists and increases in asthma mortality. There has been much debate about possible causal links for this association, and whether regular (daily) long‐acting beta2‐agonists are safe.

Objectives

The aim of this review is to assess the risk of fatal and non‐fatal serious adverse events in trials that randomised patients with chronic asthma to regular formoterol versus placebo or regular short‐acting beta2‐agonists.

Search methods

We identified trials using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials. We checked websites of clinical trial registers for unpublished trial data and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) submissions in relation to formoterol. The date of the most recent search was January 2012.

Selection criteria

We included controlled, parallel design clinical trials on patients of any age and severity of asthma if they randomised patients to treatment with regular formoterol and were of at least 12 weeks' duration. Concomitant use of inhaled corticosteroids was allowed, as long as this was not part of the randomised treatment regimen.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected trials for inclusion in the review. One author extracted outcome data and the second author checked them. We sought unpublished data on mortality and serious adverse events.

Main results

The review includes 22 studies (8032 participants) comparing regular formoterol to placebo and salbutamol. Non‐fatal serious adverse event data could be obtained for all participants from published studies comparing formoterol and placebo but only 80% of those comparing formoterol with salbutamol or terbutaline.

Three deaths occurred on regular formoterol and none on placebo; this difference was not statistically significant. It was not possible to assess disease‐specific mortality in view of the small number of deaths. Non‐fatal serious adverse events were significantly increased when regular formoterol was compared with placebo (Peto odds ratio (OR) 1.57; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.31). One extra serious adverse event occurred over 16 weeks for every 149 people treated with regular formoterol (95% CI 66 to 1407 people). The increase was larger in children than in adults, but the impact of age was not statistically significant. Data submitted to the FDA indicate that the increase in asthma‐related serious adverse events remained significant in patients taking regular formoterol who were also on inhaled corticosteroids.

No significant increase in fatal or non‐fatal serious adverse events was found when regular formoterol was compared with regular salbutamol or terbutaline.

Authors' conclusions

In comparison with placebo, we have found an increased risk of serious adverse events with regular formoterol, and this does not appear to be abolished in patients taking inhaled corticosteroids. The effect on serious adverse events of regular formoterol in children was greater than the effect in adults, but the difference between age groups was not significant.

Data on all‐cause serious adverse events should be more fully reported in journal articles, and not combined with all severities of adverse events or limited to those events that are thought by the investigator to be drug‐related.

Keywords: Adult, Child, Humans, Adrenergic beta‐Agonists, Adrenergic beta‐Agonists/adverse effects, Adrenergic beta‐Agonists/therapeutic use, Age Factors, Albuterol, Albuterol/therapeutic use, Asthma, Asthma/drug therapy, Asthma/mortality, Bronchodilator Agents, Bronchodilator Agents/adverse effects, Bronchodilator Agents/therapeutic use, Chronic Disease, Ethanolamines, Ethanolamines/adverse effects, Ethanolamines/therapeutic use, Formoterol Fumarate, Terbutaline, Terbutaline/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Does daily treatment with formoterol result in more serious adverse events compared to placebo or daily salbutamol?

Asthma is a common condition that affects the airways – the small tubes that carry air in and out of the lungs. When a person with asthma comes into contact with an irritant (an asthma trigger), the muscles around the walls of the airways tighten, the airways become narrower, and the lining of the airways becomes inflamed and starts to swell. This leads to the symptoms of asthma ‐ wheezing, coughing and difficulty in breathing. They can lead to an asthma attack or exacerbation. People can have underlying inflammation in their lungs and sticky mucus or phlegm may build up, which can further narrow the airways. There is no cure for asthma; however there are medications that allow most people to control their asthma so they can get on with daily life.

Long‐acting beta2‐agonists, such as formoterol, work by reversing the narrowing of the airways that occurs during an asthma attack. These drugs ‐ taken by inhaler ‐ are known to improve lung function, symptoms, quality of life and reduce the number of asthma attacks. However, there are concerns about the safety of long‐acting beta2‐agonists, particularly in people who are not taking inhaled corticosteroids to control the underlying inflammation. We did this review to take a closer look at the safety of people taking formoterol daily compared to people on placebo or the short acting beta2‐agonist salbutamol.

There was no statistically significant difference in the number of people who died during treatment with formoterol compared with placebo or salbutamol. Because so few people die of asthma, huge trials or observational studies are normally required to detect a difference in death rates from asthma. There were more non‐fatal serious adverse events in people taking formoterol compared to those on placebo; for every 149 people treated with formoterol for 16 weeks, one extra non‐fatal event occurred in comparison with placebo. There was no significant difference in serious adverse events in people on formoterol compared to regular salbutamol.

We conclude that regular formoterol should not be taken by people who are not taking regular inhaled steroids due to the increased risk of serious adverse events. Formoterol should not be used as a substitute for inhaled corticosteroids, and adherence with inhaled steroids should be kept under review if separate inhalers are used when formoterol is added to inhaled corticosteroids.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings ‐ SAE all ages.

| Regular formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol for chronic asthma: SAEs in adults and children | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with chronic asthma Settings: community Intervention: regular formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Regular formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol | |||||

| SAEs ‐ formoterol versus placebo (follow‐up: mean 16 weeks) | Medium‐risk population | OR 1.57 (1.05 to 2.37) | 6646 (19) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (10 to 23) | |||||

| SAEs ‐ formoterol versus salbutamol (follow‐up: mean 13 weeks) | Medium‐risk population | OR 0.72 (0.37 to 1.43) | 2119 (9) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 23 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (9 to 33) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; SAE: serious adverse event | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Confidence interval includes the possibility of harm or benefit

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings ‐ mortality (all‐cause).

| Regular formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol for chronic asthma | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with chronic asthma Settings: community Intervention: regular formoterol Comparison: placebo or salbutamol | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or salbutamol | Regular formoterol | |||||

| Mortality (all‐cause) ‐ formoterol versus placebo (follow‐up: mean 16 weeks) | Medium‐risk population | OR 1.52 (0.24 to 9.71) | 5463 (14) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Mortality (all‐cause) ‐ formoterol versus salbutamol (follow‐up: mean 13 weeks) | Medium‐risk population | OR 0.5 (0.03 to 8.05) | 1418 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Not enough data to assess this outcome

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings ‐ SAE children.

| Regular formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol for children with chronic asthma: serious adverse events | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with chronic asthma (children) Settings: community Intervention: regular formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Regular formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol | |||||

| SAEs ‐ formoterol versus placebo (follow‐up: mean 23 weeks) | Medium‐risk population | OR 2.82 (1.16 to 6.83) | 1335 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 12 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (14 to 77) | |||||

| SAEs ‐ formoterol versus salbutamol | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; SAE: serious adverse event | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

Description of the condition

There is currently no universally accepted definition of the term 'asthma'. This is in part due to an overlap of asthmatic symptoms with those of other diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), but is also due to the probable existence of more than one underlying pathophysiological process. There are, for example, wide variations in the age of onset, symptoms, triggers, associations with allergic disease and the type of inflammatory cell infiltrate seen in patients diagnosed with severe asthma (Miranda 2004). Patients with all forms and severity of disease will typically have intermittent symptoms of cough, wheeze and/or breathlessness. Underlying these symptoms there is a process of variable, at least partially reversible airway obstruction, airway hyper responsiveness and, in most cases, chronic inflammation.

Airway obstruction

Patients with a history of asthma demonstrate chronic changes within the airways including goblet cell hyperplasia, airway smooth muscle (ASM) hyperplasia and hypertrophy (Ebina 1993; Ordonez 2001; Woodruff 2004) and excess myofibroblasts with increased subepithelial collagen deposition (Brewster 1990). In the acute setting, in patients who have died of status asthmaticus, airway obstruction is evident from air‐trapping and lung hyperinflation with mucus plugging of the small and large airways (Dunnill 1960; Kuyper 2003). There is also shedding of ciliated bronchial mucosal cells, inflammatory cell infiltrates and submucosal oedema with transudation of fluid into the bronchial lumen (Carroll 1993). It is more difficult to measure the degree of ASM contraction (bronchoconstriction) in post‐mortem studies although evidence for a role of bronchoconstriction in airway narrowing comes from other sources.

Airway hyper responsiveness

Patients with asthma typically display a degree of 'airway hyper responsiveness' to inhaled allergens (Cockcroft 2006), and to a variety of chemical stimuli including histamine, serotonin, bradykinin, prostaglandins, methacholine and acetylcholine as well as other triggers such as exercise, deep inhalation and inhalation of cold air (Boushey 1980). Bronchoconstriction is implicated as the primary effector mechanism of airway narrowing in these responses. This is because of both the short time frame of the response and because many of these stimuli typically either cause bronchoconstriction directly in vitro or promote bronchoconstriction through interference with the autonomic control of ASM. Further evidence comes from findings that this response can be abolished or diminished by bronchodilator medications such as atropine and beta2‐agonists (Phillips 1990; Simonsson 1967); although beta2‐agonists in particular may have additional mechanisms of action. Whether airway hyper responsiveness relates primarily to an abnormality of ASM, to increased ASM bulk (Wiggs 1990), to aberrant autonomic control or reflex pathways, or to physical damage to the airway epithelium remains to be established. Regular use of salbutamol has, however, been shown to increase airway hyper responsiveness to allergen exposure and produce tolerance to the protective effect of salbutamol against bronchoconstriction induced by both methacholine and allergens (Cockcroft 1993).

Inflammation

It has long been thought that the histological changes described above and the phenomenon of airway hyper responsiveness are due to a combined acute and chronic inflammatory response (Bousquet 2000). Patients with status asthmaticus have increased numbers of inflammatory cells including eosinophils and neutrophils, as well as a variety of pro‐inflammatory cytokines and chemokines found in bronchial alveolar lavage (Tonnel 2001). In patients with chronic asthma there is also evidence of increased eosinophil numbers (Bousquet 1990), inflammatory cell adhesion molecules (Vignola 1993) and some evidence of an association between the extent of inflammation, disease severity and hyperreactivity. This association has however been questioned on the background of a number of negative results (Brusasco 1998), although it is made difficult to prove by the lack of a consistent marker of a sequential and variable inflammatory response (Haley 1998).

Description of the intervention

Beta2‐agonists and mortality: an historical perspective

Time trend data and case‐control studies

Adrenaline was successfully used in the symptomatic treatment of asthma as far back as 1903 (Tattersfield 2006). Initially given subcutaneously, the inhaled route was tried in 1929 to reduce adverse effects but these remained a problem and in 1940 details of a new agent, isoprenaline (isoproterenol), were published in Germany (Konzett 1940). Although isoprenaline was more selective for beta‐ as opposed to alpha‐adrenoreceptors, adverse effects including palpitations were still a major problem, particularly with oral administration (Gay 1949) and it first became available as atomiser spray for use in the UK in 1948 (Pearce 2001).

Prior to the 1940s, mortality rates from asthma in a number of countries were stable and low at less than 1 asthma death per 100,000 people per year (Pearce 2001; Figure 1). During the 1940s and 50s there was a slight rise in mortality rates and concerns about a possible link to inhaled adrenaline were raised at an early stage (Benson 1948). However, the rise was small and the cause unclear and sales continued to increase with the introduction of aerosol or metered‐dose inhalers in the early 1960s. During this decade there was an epidemic of asthma deaths in at least six countries including England, Wales and New Zealand (Figure 1). In all six countries the epidemics coincided with the licensing of an aerosol called 'Isoprenaline Forte', which contained five times the dose of isoprenaline per administration than the standard preparation (Stolley 1972). In other countries including the Netherlands, where isoprenaline forte was introduced late and sales volumes low, and in the US, where isoprenaline forte was not licensed, no increase in asthma mortality occurred. This was despite an approximate trebling in per capita alternative bronchodilator sales between 1962 and 1968 in the US (Stolley 1972). A detailed review of the epidemic in England and Wales concluded it was not due to changes in death certification, disease classification or an increase in asthma prevalence, but instead was most likely due to new methods of treatment (Speizer 1968). In England and Wales mortality rates fell following health warnings about the overuse of inhalers and banning of over the counter sales in 1968. It was around this time that more selective beta2‐agonists such as terbutaline (Bergman 1969) and salbutamol (albuterol) (Cullum 1969) were being developed.

1.

Changes in asthma mortality (5 to 34 age group) in three countries in relation to the introduction of isoprenaline forte in the UK and New Zealand and of fenoterol in New Zealand. (From Blauw 1995. With permission from the Lancet).

In the late 1970s a second epidemic of asthma deaths occurred in New Zealand (Figure 1). It was later shown that this epidemic coincided with the introduction and rising sales of fenoterol, a new short‐acting beta2‐agonist (Crane 1989; Figure 2). A significant association between mortality and fenoterol use was demonstrated in three consecutive case‐control studies, the latter studies addressing criticisms of the first (Crane 1989; Grainger 1991; Pearce 1990). Furthermore the relative risk of asthma death in patients prescribed fenoterol increased markedly when analysis was restricted to subgroups defined by markers of severity, including previous hospital admission and use of oral corticosteroids. Following the publication of the first case‐control study, the fenoterol market share in New Zealand fell from 30% in 1988 to 3% in 1991 and by the early 1990s the mortality epidemic appeared to be over (Figure 2). During the gradual decline in mortality in New Zealand from its peak in 1979, total sales of alternative beta2‐agonists, including salbutamol, gradually rose and the use of inhaled corticosteroids also increased during the latter half of the 1980s (Pearce 2007).

2.

Inhaled fenoterol market share and annual asthma mortality in New Zealand in persons aged 5 to 34

The introduction of long‐acting beta2‐agonists

Given the relatively short action of beta2‐agonists such as salbutamol, in the late 1980s efforts were made to develop longer‐acting compounds. Subsequently the long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABAs), salmeterol and formoterol were released by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Novartis, respectively. Both drugs cause bronchodilation that lasts for more than 12 hours although formoterol has a faster onset of action (Kemp 1993; Ringdal 1998). Given previous concerns about the safety profile of some of the short acting beta2‐agonists, salmeterol and formoterol were subject to randomised controlled trials on larger numbers of patients. Using these trials several Cochrane reviews have addressed the efficacy of LABAs in addition to inhaled corticosteroids (Ni Chroinin 2004; Ni Chroinin 2005), in comparison with placebo (Walters 2007), short‐acting beta2‐agonists (Walters 2002), leukotriene‐receptor antagonists (Ducharme 2006), and increased doses of inhaled corticosteroids (Greenstone 2005). The beneficial effects of LABAs on lung function, symptoms, quality of life and exacerbations requiring oral steroids have been demonstrated. However, with some studies demonstrating an associated increase in mortality concerns about the safety profile of LABAs have heightened and there has been much debate about the potential protective role of inhaled corticosteroids.

How the intervention might work

We have outlined the pharmacology of beta2‐agonists in detail in Appendix 1. Since the early epidemics in asthma mortality, a number of potential mechanisms have been proposed to explain a relationship to the use of beta2‐agonists. We discuss these mechanisms in detail in Appendix 2; they include direct toxicity, tolerance, delay in seeking help and reduction in use of inhaled corticosteroids.

Why it is important to do this review

We have taken a different approach from Salpeter 2006, in that we have not assumed a class effect of long‐acting beta2‐agonists, but we have considered trials comparing regular formoterol to placebo or regular salbutamol/terbutaline. We have chosen not to include results from trials on salmeterol in this review, as there are known differences in the pharmacological properties of salmeterol and formoterol (Ringdal 1998; Van Noord 1996). This review forms part of a set of reviews on the safety of regular salmeterol and formoterol that has now been published (Cates 2008; Cates 2009; Cates 2009a; Cates 2011). We have also excluded studies which randomised participants to formoterol and inhaled corticosteroids for this review, as these are considered in another review (Cates 2009a).

In view of the difficulty in ascertaining the causation of deaths and serious adverse events (SAEs), we have considered all‐cause fatal and non‐fatal SAEs as the main outcomes of this review, with asthma‐related and cardiovascular events as secondary outcomes.

Objectives

To assess the risk of mortality and non‐fatal serious adverse events in trials which randomise patients with chronic asthma to formoterol alone

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised trials (RCTs) of parallel design, with or without blinding, in which formoterol alone was randomly assigned to patients with chronic asthma. We excluded studies on acute asthma and exercise‐induced bronchospasm.

Types of participants

We included patients with a clinical diagnosis of asthma of any age group, unrestricted by disease severity, previous or current treatment.

Types of interventions

We included trials that randomised patients to receive inhaled formoterol twice daily for a period of at least 12 weeks, at any dose and delivered by any device (metered‐dose inhalers (MDIs) with chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) or hydrofluoroalkane (HFAs), or dry powder inhalers (DPIs)). We included studies that used comparison groups with placebo or short‐acting beta2‐agonists, and co‐intervention with leukotriene receptor antagonists, inhaled or oral corticosteroids or theophylline was allowed as long as they are not part of the randomised intervention. We excluded studies that randomised patients to formoterol for intermittent use as a reliever, and studies that compared different doses of formoterol, or different delivery devices or propellants (with no placebo arm). We also excluded studies in which formoterol was randomised together with an inhaled steroid (in separate inhalers or a combined inhaler) from this review; however these are considered in a separate review (Cates 2009a).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

All‐cause non‐fatal serious adverse events

Secondary outcomes

Asthma‐related mortality

Asthma‐related non‐fatal serious adverse events

Respiratory‐related mortality

Respiratory‐related non‐fatal serious adverse events

Cardiovascular‐related mortality

Cardiovascular‐related non‐fatal serious adverse events

Asthma‐related non‐fatal life‐threatening events (intubation or admission to intensive care)

Respiratory‐related non‐fatal life‐threatening events (intubation or admission to intensive care)

We did not restrict outcomes to those that the trial investigators considered to be related to trial medication.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (see Appendix 3 for details). All records in the Specialised Register coded as 'asthma' were last searched in January 2012 using the following terms:

(((beta* and agonist*) and (long‐acting or "long acting")) or ((beta* and adrenergic*) and (long‐acting or "long acting")) or (bronchodilat* and (long‐acting or "long acting")) or (salmeterol or formoterol or eformoterol or Advair or Symbicort or serevent or Seretide or Oxis)) AND (serious or safety or surveillance or mortality or death or intubat* or adverse or toxicity or complications or tolerability)

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We also checked websites of clinical trial registers for unpublished trial data and FDA submissions in relation to formoterol.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Both authors (CJC, MJC) independently assessed studies identified in the literature searches by examining titles, abstract and keywords fields. We obtained studies that potentially fulfilled the inclusion criteria in full text. We independently assessed these full‐text trial reports for inclusion. We resolved disagreements by consensus. We kept a record of decisions.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data using a prepared checklist before entering into Rev Man 5.0. We entered data on characteristics of included studies (methods, participants, interventions, outcomes) and results of the included studies. We contacted authors or manufacturers if serious adverse event data were not included in the trial report, and searched manufacturers' and FDA websites for further details of adverse events.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both authors assessed the included studies for bias protection (including sequence generation for randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and assessors, loss to follow‐up, completeness of outcome assessment and other possible bias prevention). We resolved disagreements by consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

We recorded the number of participants with a serious adverse event of any cause (fatal and non‐fatal), and in view of the difficulty in deciding whether events are asthma‐related, we noted details of the cause of death and serious adverse events where they were available. We noted the definition of serious adverse events, and sought further information if this was not clear (particularly in relation to hospital admissions and serious adverse events).

Unit of analysis issues

We extracted data using the number of participants who suffered one or more serious adverse events, in order to avoid double‐counting events from the same participant.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity in the pooled odds ratio using the I2 statistic in RevMan 5.0.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias by comparing the published and unpublished serious adverse events, and by comparing all serious adverse events with those that were thought to be drug‐related. We also compared serious events with all adverse events (whether serious or not).

Data synthesis

The outcomes of this review were dichotomous and we recorded the number of participants with each outcome event, by allocated treated group. We planned to analyse mortality using risk difference, as many studies did not have any deaths in either arm. However, the recently revised Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions advises against this approach, so we only used the risk differences to estimate the absolute impact of treatment (Higgins 2008). Although meta‐analysis with Peto odds ratio has advantages when events are rare (Bradburn 2007), it performs less well with unbalanced treatment arms and large effect sizes, and therefore we calculated the results for serious adverse events and mortality in RevMan 5.0 as pooled odds ratios using the Mantel‐Haenszel (MH) fixed‐effect model. We compared the results of this model to the Peto method and MH random‐effects models (as sensitivity analysis), although Bradburn 2007 cautions against the random‐effects model as the variance calculations are based on large sample assumptions. We explored heterogeneity on the basis of the subgroup and sensitivity analyses outlined below. We inspected funnel plots to assess publication bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses on the primary outcomes on the basis of dose of formoterol (usual dose versus high dose), age (adults versus children) and comparator used. We planned to carry out subgroup analysis based on reported corticosteroid use, but none of the studies reported whether the patients who actually suffered serious adverse events were taking inhaled corticosteroids or not. We compared subgroups using tests for interaction (Altman 2003).

The definition of serious adverse events was rarely reported in the trials, but there is a standard definition used by industry in clinical study reports (ICHE2a 1995) and this is listed in Appendix 4.

Sensitivity analysis

We checked the overall results for the primary outcomes to assess the impact of removing the results from unblinded studies, and also those participants that were randomised to high‐dose formoterol (24 µg twice daily). We also checked the impact of using fixed or random‐effects models for meta‐analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

See Figure 3 for the study flow diagram. We found 512 abstracts from the initial search in October 2007 (reduced to 504 after removing duplicates). We identified 128 relevant abstracts that related to formoterol alone. We included 22 studies (32 references) in the review and excluded 95 others (see Excluded studies). Of those excluded 53 were less than 12 weeks in duration, (including 29 single‐dose studies), three were not RCTs, eight were dose or device comparison studies, nine were on exercise‐induced bronchospasm or acute asthma, nine used formoterol as reliever medication, eight were cross‐over in design, three randomised to formoterol and budesonide and five were excluded for other reasons. One study that was included in Salpeter 2006 was excluded from this review because formoterol was randomised with budesonide (Price 2002) and therefore did not fit the inclusion criteria for this review. Both authors reached consensus on all the included studies after inspection of the full text from papers and websites.

3.

Study flow diagram.

We repeated the search in July 2008, when we found 48 further abstracts. Six were relevant to this review but we excluded five as they were short‐term studies, and one was on exercise‐induced bronchospasm; we found no new studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Similarly a further search in January 2012 (cumulative total of 748 citations) identified three potentially relevant studies (Happonen 2009; Kamenov 2007; Price 2008). On checking the full text, none of these yielded new trials that were suitable for inclusion (see Excluded studies).

We identified one additional included study from other reviews; this was a trial on the AstraZeneca controlled trials register (SD‐037‐0344) which is otherwise unpublished. Additionally two documents on the FDA website provided additional serious adverse event information for four of the included studies (Bensch 2001; Bensch 2002; Pleskow 2003; Wolfe 2006). Additionally 22 studies of at least four weeks duration are listed in the appendix to a Novartis FDA submission (NovartisNDA20‐831 2005), but it is not clear how these relate to the 10 included studies that we found which were supported by Novartis.

Included studies

We included 22 studies on 8032 participants (6693 adults and 1339 children); the characteristics of these studies are fully described in Characteristics of included studies. Sponsorship of the studies is also listed in Table 4.

1. Study sponsors.

| Study ID | Sponsor |

| Bensch 2001 | Novartis |

| Bensch 2002 | Novartis |

| Busse 2004 | Novartis |

| Corren 2007 | AstraZeneca |

| Ekstrom 1998 | AstraZeneca |

| Ekstrom 1998a | AstraZeneca |

| FitzGerald 1999 | Novartis |

| Hekking 1990 | Not reported |

| Kesten 1991 | Novartis |

| Kozlik‐Feldmann 1996 | Not reported |

| LaForce 2005 | Novartis |

| Levy 2005 | Novartis |

| Molimard 2001 | Novartis |

| Noonan 2006 | AstraZeneca |

| Pleskow 2003 | Novartis |

| SD‐037‐0344 | AstraZeneca |

| Steffensen 1995 | Novartis |

| van der Molen 1997 | AstraZeneca |

| van Schayck 2002 | Not reported |

| Von Berg 2003 | AstraZeneca |

| Wolfe 2006 | Novartis |

| Zimmerman 2004 | AstraZeneca |

Eight studies enrolled adults over 18 years of age (Ekstrom 1998; Ekstrom 1998a; FitzGerald 1999; Hekking 1990; Kesten 1991; Molimard 2001; Steffensen 1995; van der Molen 1997), one study adults over 16 years of age (van Schayck 2002), eight studies adults and adolescents over 12 years of age (Bensch 2001; Busse 2004; Corren 2007; LaForce 2005; Noonan 2006; Pleskow 2003; SD‐037‐0344; Wolfe 2006) and five enrolled children from five up to 12 or 16 years of age (Bensch 2002; Kozlik‐Feldmann 1996; Levy 2005; Von Berg 2003; Zimmerman 2004).

All of the studies were of 12 weeks duration with the exception of Bensch 2002 (52 weeks), FitzGerald 1999 (24 weeks), van der Molen 1997 (24 weeks) and Wolfe 2006 (16 weeks). This gives a weighted mean duration of 16 weeks for the 19 studies with a placebo arm.

Since many of the studies randomised patients to more than two treatment arms, we have reported the overall number of patients randomised to treatment categories under investigation. Adults and adolescents are combined, as separate data for adolescents were not provided in any of the studies. In total 8032 participants were randomised (6693 adults and 1339 children); of these 2146 adults and 483 children received placebo, 2483 adults and 568 children received formoterol up to 12 µg twice daily, 921 adults and 277 children received formoterol 24 µg twice daily, and 1143 adults and 11 children received regular salbutamol or terbutaline. Although Molimard 2001 was an open study that did not use a placebo group, we included it in the placebo comparisons as on‐demand salbutamol was used by patients in both the formoterol and the comparison arm.

Doses of formoterol ranged from 4.5 µg to 24 µg twice daily in children and 6 µg to 24 µg twice daily in adults (but different delivery devices mean that the delivered dose may not be identical between studies, even if the nominal dose is the same). We have considered high‐dose formoterol to be 24 µg twice daily.

Concurrent use of inhaled corticosteroids varied in the included studies from zero to 100%; Table 5 lists the inhaled steroid use by study. In almost all the studies at least half of the patients were taking inhaled corticosteroids at baseline.

2. Proportion of participants using inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).

| Study ID | Proportion of participants on ICS |

| Bensch 2001 | 51% |

| Bensch 2002 | 69% |

| Busse 2004 | 64% |

| Corren 2007 | 0% (withdrawn) |

| Ekstrom 1998 | 86% |

| Ekstrom 1998a | 89% |

| FitzGerald 1999 | 100% |

| Hekking 1990 | Not reported |

| Kesten 1991 | 62% |

| Kozlik‐Feldmann 1996 | 0% |

| LaForce 2005 | 67% |

| Levy 2005 | 72% |

| Molimard 2001 | 100% |

| Noonan 2006 | 100% |

| Pleskow 2003 | 44% |

| SD‐037‐0344 | 100% |

| Steffensen 1995 | 87% |

| van der Molen 1997 | 100% |

| van Schayck 2002 | 95% |

| Von Berg 2003 | 82% |

| Wolfe 2006 | 62% |

| Zimmerman 2004 | 100% |

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 4 show a graphical representation of the domains of risk of bias across each study.

4.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Allocation concealment and sequence generation were often poorly reported in the included studies. However, the majority of the studies are supported by manufacturers of formoterol (see Table 4) and are therefore likely to have had appropriate protection against selection bias.

Blinding

All studies were double‐blind except for Kozlik‐Feldmann 1996, Molimard 2001 and van Schayck 2002, and of these only Molimard 2001 has contributed data to the primary outcomes.

Incomplete outcome data

The included studies generally had withdrawal rates of less than 20% with the exception of Corren 2007 (51% dropout in the placebo group), and Noonan 2006 (60% withdrawals in placebo arm and 51.2% in formoterol arm).

Selective reporting

Although paper reports of studies often did not include usable information on all‐cause serious adverse events, it has proved possible to obtain serious adverse events information from 19 of the 22 included studies. This represents 100% of participants randomised to formoterol or placebo, but only 80% of participants compared to regular salbutamol or terbutaline. There are clear guidelines for the reporting of serious adverse events for industry (ICHE3 2007). These all have to be listed in detail for the regulatory authorities, but there is clearly no similar expectation from medical journals.

Twenty‐two studies of at least four weeks duration are listed in the appendix to a Novartis FDA submission (NovartisNDA20‐831 2005), but it is not clear how many of these would fulfil the criteria for inclusion in this review, or how they related to the 10 Novartis studies included in this review (Table 4). It has not been possible to obtain further information from the sponsors.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Events were sparse in the trials and the presence or absence of mortality was not always reported in the paper publications.

Formoterol versus placebo

Data were available from 14 studies comparing formoterol (N = 3413) with placebo (N = 2050); this represents 80% of the randomised patients for this comparison. Three deaths occurred in these trials (two adults and one child), and overall there were three deaths on formoterol and none on placebo. The cause of death for one adult was not reported in SD‐037‐0344, there was one adult death from asthma in Pleskow 2003, and one child died of a subarachnoid haemorrhage in Von Berg 2003. The pooled odds ratio (OR) was not statistically significant (Peto OR 4.50; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.41 to 49.49), see Figure 5. The confidence interval and point estimate are somewhat different for a Mantel‐Haenszel OR 1.52 (95% CI 0.24 to 9.71) using fixed or random‐effects models. This discrepancy is due to the continuity correction required for zero cells in the Mantel‐Haenszel method. The point estimate of the pooled risk difference (RD) was an increase of 4 deaths per 10,000 treated with regular formoterol over 16 weeks, with a confidence interval from 20 fewer deaths to 28 more deaths per 10,000. There was no statistical heterogeneity in this outcome.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All‐cause mortality, outcome: 1.1 Overall results.

Formoterol versus salbutamol

Data were available from six studies comparing formoterol (N = 847) to salbutamol/albuterol (N = 571), representing 49% of the randomised patients for this comparison. Only two deaths occurred, both in Pleskow 2003; one in the formoterol arm (from asthma as reported above) and one in the salbutamol arm (from pancreatitis), and again the difference was not statistically significant. As only one study contributed to this outcome, we calculated no pooled OR.

Subgroup analyses

No subgroup analyses were possible for all‐cause mortality as the data were too sparse.

Serious adverse events (SAEs) (non‐fatal all‐cause)

An example of the definition of a serious adverse event (SAE) is given in Pleskow 2003: “A serious adverse event was defined as any experience that was fatal or life‐threatening, permanently disabling, requiring in‐patient or prolonged hospitalisation, or was a congenital abnormality, cancer or drug overdose.” This is in line with the definition in Appendix 4, and we have assumed that this definition was used in the other trials (even though this was often not made explicit). In most cases the events were defined as serious because they were associated with hospital admission.

Formoterol versus placebo

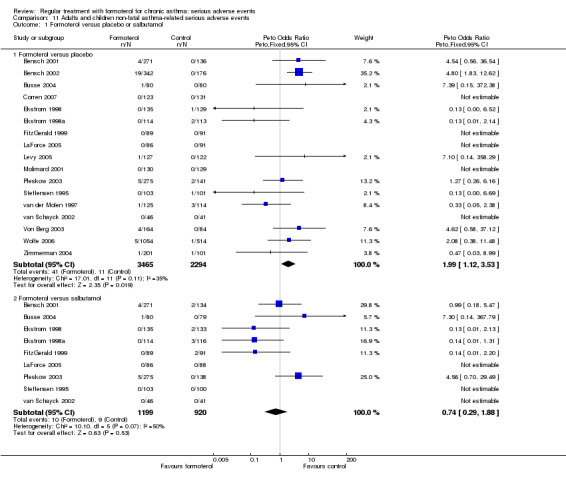

Combined data from adults and children

Data were available on non‐fatal SAEs for 19 studies comparing regular formoterol (N = 4017) to placebo (N = 2629); this represents all of the randomised patients from published studies for this comparison. The studies were largely on adults (N = 5311), but five trials were in children (N = 1335).

The overall result indicated an increased risk of SAEs with formoterol (Peto OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.31) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), Figure 6. SAEs were rare in the studies (occurring in 1.2% of patients on placebo over a weighted mean of 16 weeks), so the pooled risk difference is small at 0.007 (95% CI 0.0012 to 0.013) and using a weighted mean of the placebo arms, over a 16‐week period there would need to be 149 patients treated (95% CI 66 to 1407) for one extra serious adverse event to occur; this number needed to treat was calculated by Visual Rx using the pooled odds ratio and baseline risk of 1%. This is illustrated in Figure 7 which shows that for every thousand patients treated over 16 weeks with formoterol there are an extra six patients who will suffer a serious adverse event, so that in comparison to 10 per thousand in the placebo group this rises to 16 per thousand on regular formoterol.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Adults and children non‐fatal serious adverse events, outcome: 2.1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

7.

Serious adverse events with regular formoterol compared to placebo. In the control group 12 people out of 1000 had serious adverse events over 16 weeks, compared to 19 (95% CI 13 to 27) out of 1000 for the active treatment group.

Sensitivity analysis by applying the Mantel‐Haenszel method gave a very similar result, OR 1.57 (95% CI 1.05 to 2.37). Using a random‐effects model (which is not recommended for rare events due to an increased risk of bias (Bradburn 2007)), the point estimate was similar but the confidence interval widened: OR 1.52 (95% CI 0.96 to 2.40). When we excluded the participants receiving high‐dose formoterol (24 µg) arms from the analysis the confidence interval again widened (Peto OR 1.55; 95% CI 0.97 to 2.48)(Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adults and children non‐fatal serious adverse events (without formoterol 24 µg arms), Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

Adults with non‐fatal serious adverse events

When the adult data comparing regular formoterol (N = 3170) with placebo (N = 2137) were considered on their own, the results showed a smaller increase in risk which did not reach statistical significance (Peto OR 1.23; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.99)(Analysis 4.1). The Mantel‐Haenszel method gave very similar results, OR 1.22 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.96).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Adults with non‐fatal serious adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

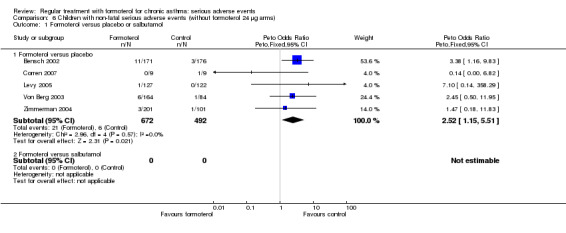

Children with non‐fatal serious adverse events

Although fewer children were studied, regular formoterol (N = 843) compared with placebo (N = 492), the separate results for children showed a larger increase in serious adverse events with regular formoterol (Peto OR 2.48; 95% CI 1.27 to 4.83)(Analysis 5.1). Again the Mantel‐Haenszel method gave a very similar result, OR 2.92 (95% CI 1.26 to 6.74). There was low heterogeneity in this outcome (I2 = 0%), and the result in children remained significant when the data on high‐dose formoterol were excluded (Peto OR 2.52; 95% CI 1.15 to 5.51) and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 2.59 (95% CI 1.08 to 6.19)(Analysis 6.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Children with non‐fatal serious adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Children with non‐fatal serious adverse events (without formoterol 24 µg arms), Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

When the results in children are compared with adults using a test for interaction (Altman 2003), the increased risk in children relative to adults is a relative OR of 2.39 (95% CI 0.91 to 6.27) using the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio, which is not statistically significant. The results are very similar when the Peto OR is compared between adults and children (relative OR 2.02; 95% CI 0.89 to 4.59).

High‐dose formoterol versus lower doses

When the study arms using formoterol 24 µg twice daily were compared to those using lower doses (formoterol 12 µg twice daily), no significant difference was found in adults (Peto OR 1.35; 95% CI 0.64 to 2.85)(Analysis 7.1). The confidence interval for this result is too wide to rule out a difference in relation to dose, and although the three adult studies all used the same dry powder delivery device (Aerolizer), there is a high level of heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 74%), which is unexplained.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Dose comparison: formoterol 24 µg versus 12 µg twice daily, Outcome 1 Serious adverse events.

Moreover the data from the Novartis database of published and unpublished placebo‐controlled studies of at least four weeks duration has been included for comparison (Novartis 2005); the Novartis data show a significantly higher risk of asthma‐related serious adverse events with formoterol 24 µg twice daily in comparison to 12 µg twice daily (Peto OR 2.16; 95% CI 1.13 to 4.11) and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 2.08 (95% CI 1.11 to 3.89).

Formoterol versus salbutamol

Adults with non‐fatal serious adverse events

In contrast, the results from nine studies in adults comparing regular formoterol (N = 1119) to salbutamol (N = 920), representing 80% of the randomised patients for this comparison, showed a non‐significant reduction in the risk of SAEs (Peto OR 0.73; 95% CI 0.37 to 1.43)(Analysis 4.1). However, when the results from patients using high‐dose formoterol were excluded, there was a significant reduction in risk for formoterol in comparison with salbutamol or terbutaline (Peto OR 0.41; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.90) and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 0.40 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.94) (Analysis 3.1). A test for interaction between the results comparing formoterol with placebo and salbutamol was not significant; the risk in trials against regular salbutamol compared to those against placebo using Mantel‐Haenszel OR gives a relative OR of 0.46 (95% CI 0.21 to 1.01), whilst for the Peto method the relative OR is 0.59 (95% CI 0.26 to 1.36).

No studies were found comparing regular formoterol to regular salbutamol or terbutaline in children.

SAEs all‐cause (fatal and non‐fatal combined)

When fatal and non‐fatal SAEs are considered together the findings are very similar to those for the non‐fatal events, with a significant increase in risk with regular formoterol in comparison with placebo (Peto OR 1.61; 95% CI 1.09 to 2.37) and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 1.63 (95% CI 1.08 to 2.44), but not in comparison with regular salbutamol (see Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Adults and children fatal and non‐fatal serious adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

Secondary outcomes

Mortality by cause of death

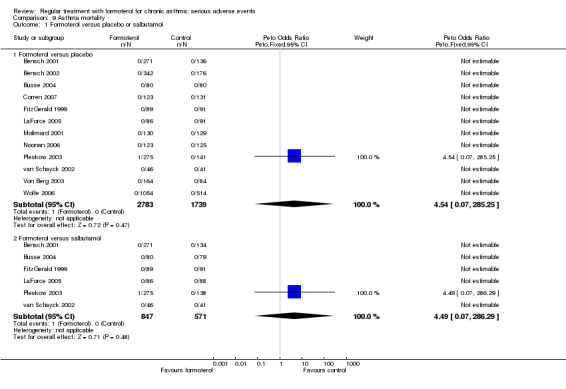

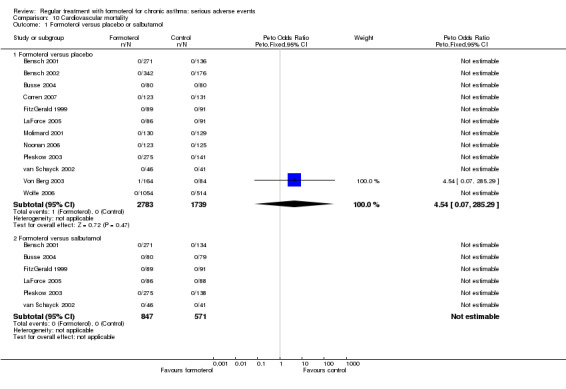

Asthma mortality and cardiovascular mortality

Only one death related to asthma was reported using formoterol 24 µg in Pleskow 2003, and one death in Von Berg 2003 from sub‐arachnoid haemorrhage on formoterol 9 µg, so there are insufficient data to assess the impact of formoterol on disease‐specific mortality. The third death in SD‐037‐0344 has no reported cause.

SAEs related to asthma and the cardiovascular system

When formoterol is compared to placebo, there is a significant increase in asthma‐related serious adverse events on regular formoterol (Peto OR 1.99; 95% CI 1.12 to 3.53) and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 1.90 (95% CI 1.03 to 3.48)(Analysis 11.1). This finding is also apparent from the Novartis integrated database (Novartis 2005), which is concordant with the results of the 10 Novartis studies included in the review as shown in Analysis 12.1.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Adults and children non‐fatal asthma‐related serious adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Adults and children non‐fatal asthma‐related serious adverse events (Novartis data), Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

In comparison with regular salbutamol there is a decrease in asthma‐related serious adverse events on regular formoterol but this is not significant (Peto OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.29 to 1.88) and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 0.72 (95% CI 0.32 to 1.76)(Analysis 11.1).

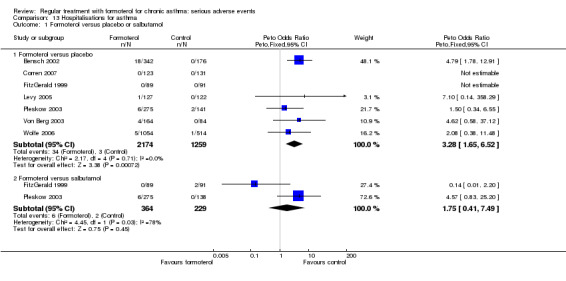

There is a significant increase in hospital admissions for asthma when regular formoterol is compared to placebo: Peto OR 3.28; 95% CI 1.65 to 6.52 and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 4.28; 95% CI 1.60 to 11.46 (Analysis 13.1). For this outcome we assumed that all the patients with asthma‐related SAE documented in the FDA submission were admitted to hospital; in Pleskow 2003 this is clearly stated to be the case for two patients on placebo and five on formoterol 24 µg, but is not clearly reported for the single patient on formoterol 12 µg (Mann 2003). No significant difference was seen when regular formoterol is compared to regular salbutamol.

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Hospitalisations for asthma, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

Very few events relating to the cardiovascular system were reported, so although the direction of effect is in favour of formoterol the confidence intervals in comparison to placebo and salbutamol are very wide (Analysis 14.1).

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Adults and children non‐fatal cardiovascular serious adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

Impact of inhaled corticosteroids

It has not been possible to assess whether inhaled corticosteroids have an impact on SAEs with regular formoterol from the included studies, as this would require individual patient data relating inhaled corticosteroid usage to those patients who suffered the events, and these data are not available. However, data are presented in Novartis 2005 in which patients on inhaled corticosteroids are compared with those who are not, for asthma‐related serious adverse events. Although the increased risk is larger without inhaled corticosteroids (Peto OR 3.22; 95% CI 1.17 to 8.89) and Mantel Haenszel OR 7.31 (95% CI 0.97 to 55.06), than with inhaled corticosteroids (Peto OR 2.58; 95% CI 1.21 to 5.49) and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 3.47 (95% CI 1.21 to 9.97), the confidence intervals are wide and there is no statistically significant interaction between the increased risk and use of inhaled corticosteroids. Moreover there remains a significant three‐fold increase in odds for patients who were taking inhaled corticosteroids, and this is maintained when the data on formoterol 24 µg twice daily are excluded (Peto OR 2.76; 95% CI 1.06 to 7.15) and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 3.11 (95% CI 1.01 to 9.55)(Analysis 15.1).

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Impact of inhaled corticosteroids on asthma‐related SAEs, Outcome 1 Patients with at least one asthma‐related SAE.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Three deaths occurred on regular formoterol and none on placebo; this difference was not statistically significant. It was not possible to assess disease‐specific mortality in view of the small number of deaths.

Non‐fatal serious adverse events (SAEs) were significantly increased in comparison with placebo. These events were rare, occurring in 1.0% of patients in the placebo arms over an average of 16 weeks; in comparison 1.6% of those given regular formoterol suffered a SAE (Figure 7). One additional participant with a SAE was found to occur for every 149 people treated with regular formoterol over 16 weeks, and the play of chance is compatible with one extra event for every 66 to 1407 given regular formoterol. The majority of these extra events appear to be asthma‐related, and data from unpublished studies on the Novartis integrated database of placebo‐controlled trials suggest that there may be a significant increase in the risk of asthma‐related SAEs with regular formoterol even in those patients who were taking inhaled corticosteroids (Analysis 15.1).

The increased risk is larger in children than in adults, but the difference between the results in children and adults is not statistically significant. No significant overall differences were found for all‐cause mortality or non‐fatal SAEs in trials comparing regular formoterol with salbutamol or terbutaline.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Although large numbers of participants have been treated with regular formoterol, the rarity of mortality and SAEs means that there is still considerable uncertainty in relation to the size of the effects being investigated. There is insufficient evidence to be sure whether the larger increase in SAEs found in children is significantly different from the smaller increase in adults. We have received additional information relating to eight studies from authors and manufacturers, but data have not been forthcoming for three of the included studies. The missing data represent a moderate proportion of the participants who are in trials comparing formoterol with salbutamol, but they could alter the point estimates and confidence intervals for this comparison. Whilst it has not been possible to obtain details of unpublished Novartis studies submitted to the FDA, the pooled data from the Novartis trials has been used in this review (but not combined with the included studies as there is an unknown degree of overlap).

Information from papers published in medical journals

All‐cause non‐fatal SAEs were published in the paper reports of studies for 31 patients on formoterol and seven patients on placebo; this less than half of the total number of events found from all sources. Considering only the data from paper reports there is still a significant increase with regular formoterol (Peto odds ratio (OR) 2.31; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17 to 4.53), see Analysis 16.1.

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Adults and children published non‐fatal serious adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

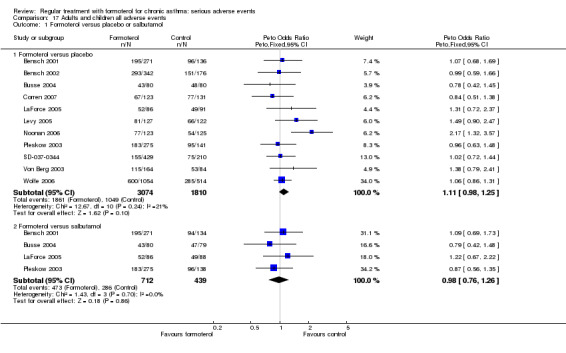

Serious and non‐serious adverse events

All adverse events are shown in Analysis 17.1, and published adverse events in Analysis 18.1. Both show small increases with regular formoterol that do not reach statistical significance, which may be because the larger number of minor adverse events are not altered by formoterol. Published drug‐related adverse events showed a significant increase as shown in Analysis 19.1.

17.1. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Adults and children all adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

18.1. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Adults and children published adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

19.1. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Adults and children all published drug‐related adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

Drug‐related serious adverse events

If the analysis had been confined to SAEs that were thought to be drug‐related, only five of the 136 SAEs would have been included, and because there is a wide confidence interval around this small number of events, no significant increase in drug‐related SAEs was found (Peto OR 1.45; 95% CI 0.18 to 11.61) and Mantel‐Haenszel OR 0.90 (95% CI 0.19 to 4.24) (Analysis 20.1).

20.1. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Adults and children serious drug‐related adverse events, Outcome 1 Formoterol versus placebo or salbutamol.

Quality of the evidence

All the studies were double‐blind with the exception of LaForce 2005, Molimard 2001 and van Schayck 2002. Of these, only Molimard 2001 contributed data to SAEs with regular formoterol in comparison with placebo, and if the meta‐analysis is confined to the double‐blind trials the increase remains significant (Peto OR 1.52; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.25). There are methodological concerns in relation to data from the Novartis integrated database, as these are not presented for the individual studies, but where it has been possible to compare results from the database with the Novartis studies included in the review the results are very similar (Analysis 12.1).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings of this review are similar to those of our review comparing regular salmeterol to placebo and regular salbutamol (Cates 2008). Both reviews show that, in comparison with placebo, there are significant increases in all‐cause SAEs with the use of regular long‐acting beta2‐agonists. The size of this increase is comparable for regular salmeterol (Peto OR 1.15; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.29) and regular formoterol (Peto OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.31). The placebo group event rates were different in the two reviews, so it would be misleading to try to compare the absolute increases in risk between salmeterol and formoterol. Similarly, although the increase in events reached statistical significance in adults (but not children) for salmeterol, and in children (but not adults) for formoterol, these age group differences may be due to the play of chance, as the test for interaction between age group and treatment effect was not significant in either case (Altman 2003).

The number of participants is too small to assess the impact of regular formoterol on all‐cause or asthma‐related mortality, so it is not possible to compare these results with the increased asthma mortality found in SMART 2006. However, data submitted by Novartis to the FDA (Novartis 2005) do indicate a significant increase in asthma‐related serious adverse events, even in patients taking regular inhaled corticosteroids (Analysis 15.1).

A recent meta‐analysis of individual patient data from trials of all FDA‐approved LABAs found a higher risk of serious asthma‐related events in children as compared to adults (McMahon 2011), which is in keeping with the results of this review. This increased risk in children persisted in those who were given concomitant ICS, but not in the trials in which participants were assigned to ICS as part of their randomised treatment.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In comparison with placebo, we have found an increased risk of serious adverse events with regular formoterol, and this does not appear to be abolished in patients taking inhaled corticosteroids. The effect on serious adverse events of regular formoterol in children was greater than the effect in adults, but the difference between age groups was not significant.

Implications for research.

Data on all‐cause serious adverse events should be more fully reported in medical journals, and not combined with all adverse events or limited to those events that are thought by the investigator to be drug‐related.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 April 2013 | Amended | NIHR acknowledgement added |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2008 Review first published: Issue 4, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 January 2012 | New search has been performed | No new studies found. Minor edits made and plain language summary revised. |

| 5 January 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New search carried out in January 2012 but no new studies included. |

| 10 November 2008 | Amended | The 'Summary of findings' tables have been reordered. Contents are unchanged. An additional reference has also been added for Corren 2007. The Primary Analysis has been changed to Peto Odds Ratio. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Susan Hansen and Elizabeth Stovold of the Cochrane Airways Group for their assistance in searching for trials and obtaining the abstracts and full reports, and extraction of data on trial characteristics, Toby Lasserson for assistance in checking outcome data and Anne Tattersfield for helpful comments. We are grateful to Martin Shaw (Novartis) for providing data in relation to FitzGerald 1999, Onno van Schayck for providing data for van Schayck 2002, Vincent Le Gros (Novartis) for providing data in relation to Molimard 2001, Andrea von Berg for providing data in relation to Von Berg 2003 and Robyn Von Maltzahn (AstraZeneca) for providing data in relation to Ekstrom 1998; Ekstrom 1998a; van der Molen 1997; Zimmerman 2004.

CRG Funding Acknowledgement: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Airways Group.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Pharmacology of beta2‐agonists

Beta2‐agonists are thought to cause bronchodilation primarily through binding beta2‐adrenoceptors on airways smooth muscle (ASM), with subsequent activation of both membrane‐bound potassium channels and a signalling cascade involving enzyme activation and changes in intracellular calcium levels following a rise in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) (Barnes 1993). However, beta2‐adrenoceptors are also expressed on a wide range of cell types where beta2‐agonists may have a clinically significant effect including airway epithelium (Morrison 1993), mast cells, post capillary venules, sensory and cholinergic nerves and dendritic cells (Anderson 2006). Beta2‐agonists will also cross‐react to some extent with other beta‐adrenoceptors including beta1‐adrenoceptors on the heart.

The in vivo effect of any beta2‐agonist will depend on a number of factors relating to both the drug and the patient. The degree to which a drug binds to one receptor over another is known as selectivity, which can be defined as absolute binding ratios to different receptors in vitro, whilst functional selectivity is measured from downstream effects of drugs in different tissue types in vitro or in vivo. All of the beta2‐agonists described thus far are more beta2 selective than their predecessor isoprenaline in vitro. However, because attempts to differentiate selectivity between the newer agents are confounded by so many factors, it is difficult to draw conclusions about in vitro selectivity studies and probably best to concentrate on specific adverse side effects in human subjects at doses which cause the same degree of bronchodilatation. The potency of a drug refers to the concentration that achieves half the maximal receptor activation of which that drug is capable but it is not very important clinically as for each drug, manufacturers will alter the dose to try to achieve a therapeutic ratio of desired to undesired effects. In contrast efficacy refers to the ability of a drug to activate its receptor independent of drug concentration. Drugs that fully activate a receptor are known as full agonists and those that partially activate a receptor are known as partial agonists. Efficacy also is very much dependent on the system in which it is being tested and is affected by factors including the number of receptors available and the presence of other agonists and antagonists. Thus whilst salmeterol acts as a partial agonist in vitro it causes a similar degree of bronchodilation to the strong agonist formoterol in stable asthmatic patients (Van Noord 1996), presumably because there are an abundance of well‐coupled beta2‐adrenoceptors available with few downstream antagonising signals. In contrast, with repetitive dosing formoterol is significantly better than salmeterol at preventing methacholine‐induced bronchoconstriction (Palmqvist 1999). These differences have led to attempts to define the 'intrinsic efficacy' of a drug independent of tissue conditions (Hanania 2002), as shown in Table 26. The clinical significance of intrinsic efficacy remains unclear.

3. Intrinsic efficacy of beta‐agonists.

| Drug | Intrinsic efficacy (%) |

| Isoprenaline, adrenaline | 100 |

| Fenoterol | 42 |

| Formoterol | 20 |

| Salbutamol | 4.9 |

| Salmeterol | < 2 |

Adapted from Hanania 2002. The authors acknowledge that it is difficult to determine the intrinsic efficacy of salmeterol given its high lipophilicity.

Appendix 2. Possible mechanisms of increased asthma mortality with beta‐agonists

Direct toxicity

This hypothesis states that direct adverse effects of beta2‐agonists are responsible for an associated increase in mortality and most research in the area has concentrated on effects detrimental to the heart. Whilst it is often assumed that cardiac side effects of beta2‐agonists are due to cross‐reactivity with beta1‐adrenoceptors (i.e. poor selectivity), it is worth noting that human myocardium also contains an abundance of beta2‐adrenoceptors capable of triggering positive chronotropic and inotropic responses (Lipworth 1992). Indeed, there is good evidence that cardiovascular side effects of isoprenaline (Arnold 1985) and other beta2‐agonists including salbutamol (Hall 1989) are mediated predominantly via cardiac beta2‐adrenoceptors thus making the concept of in vitro selectivity less relevant. Generalised beta2‐adrenoceptor activation can also cause hypokalaemia (Brown 1983) and it has been proposed that, through these and other actions, beta2‐agonists may predispose to life‐threatening dysrhythmias or cause other adverse cardiac effects.

During the 1960s epidemic most deaths occurred in patients with severe asthma and it was originally assumed that asthma and its sequelae, including hypoxia, were the primary cause of death. However, mucus plugging and hypoxia does not preclude a cardiac event as the final cause of death, and one might expect those with severe asthma to take more doses of a prescribed inhaler. As noted by Speizer and Doll most deaths in the 1960s were in the 10 to 19 age group and “at these ages children have begun to act independently and may be particularly prone to misuse a self‐administered form of treatment” (Speizer 1968). If toxicity were related to increasing doses of beta2‐agonists one might expect most deaths to occur in hospital where high doses are typically used and this was not the case. One possible explanation for this anomaly was provided by animal experiments in which large doses of isoprenaline caused little ill effect in anaesthetised dogs with normal arterial oxygenation whereas much smaller doses caused fatal cardiac depression and asystole (although no obvious dysrhythmia) when hypoxic (Collins 1969; McDevitt 1974). It has been hypothesised therefore that such events would be less likely in hospital where supplemental oxygen is routinely given. The clinical relevance of these studies remains unclear although there is some evidence of a synergistic effect between hypoxia and salbutamol use in asthmatic patients in reducing total peripheral vascular resistance (Burggraaf 2001) – another beta2‐mediated effect which could be detrimental to the heart during an acute asthma attack through a reduction in diastolic blood pressure. Other potential mechanisms of isoprenaline toxicity include a potential increase in mucous plugging and worsening of ventilation perfusion mismatch despite bronchodilation (Pearce 1990).

Further concerns about a possible toxic effect of beta2‐agonists were raised during the New Zealand epidemic in the 1970s. In 1981 Wilson et al, who first reported the epidemic, reviewed 22 fatal cases of asthma and noted “In 16 patients death was seen to be sudden and unexpected. Although all were experiencing respiratory distress, most were not cyanosed and the precipitate nature of their death suggested a cardiac event, such as an arrest, inappropriate to the severity of their respiratory problem” (Wilson 1981). In humans, fenoterol causes significantly greater chronotropic, inotropic and electrocardiographic side effects than salbutamol in asthmatic patients (Wong 1990). Interestingly, across the same parameters fenoterol also causes more side effects than isoprenaline (Burgess 1991).

In patients with mild asthma and without a bronchoconstrictor challenge, salmeterol and salbutamol cause a similar degree of near maximal bronchodilation at low doses (Bennett 1994). However, whilst as a one‐off dose salbutamol is typically used at two to four times the concentration of salmeterol, the dose equivalences for salmeterol versus salbutamol in increasing heart rate and decreasing potassium concentration and diastolic blood pressure were 17.7, 7.8 and 7.6 respectively (i.e. salmeterol had a greater effect across all parameters). Given the lower intrinsic efficacy of salmeterol (Table 4), these results highlight the importance of in vivo factors; one possible explanation for the difference is the increased lipophilicity of salmeterol compared to salbutamol contributing to higher systemic absorption (Bennett 1994).

When comparing increasing actuations of standard doses of formoterol and salmeterol inhalers in stable asthmatic patients, relatively similar cardiovascular effects are seen at lower doses (Guhan 2000). However, at the highest doses (above those recommended by the manufacturers) there were trends towards an increase in systolic blood pressure with formoterol; in comparison there was a trend towards a decrease in diastolic blood pressure and an increase in QTc interval with salmeterol although no statistical analysis of the difference was performed. In contrast in asthmatic patients with methacholine‐induced bronchoconstriction there was no significant difference between salmeterol and formoterol in causing increased heart rate and QTc interval although formoterol caused significantly greater bronchodilation and hypokalaemia (Palmqvist 1999). Whilst there is good evidence of cardiovascular and metabolic side effects with increasing doses of beta2‐agonists, it is a little difficult to envisage serious adverse effects of this nature when using LABAs at manufacturer‐recommended preventative doses. However, it is possible that some patients choose to use repeated doses of LABAs during exacerbations.

Tolerance

In this setting, the term tolerance refers to an impaired response to beta2‐agonists in patients who have been using regular beta2‐agonist treatment previously (Haney 2006). Tolerance is likely to result from a combination of reduced receptor numbers secondary to receptor internalisation and reduced production and also uncoupling of receptors to downstream signalling pathways following repeated activation (Barnes 1995). This phenomenon is likely to explain the beneficial reduction in systemic side effects seen with regular use of beta2‐agonists including salbutamol after one to two weeks (Lipworth 1989). However, the same effect on beta2‐adrenoceptors in the lung might be expected to produce a diminished response to the bronchodilating activity of beta2‐agonists following regular use. In patients with stable asthma, whilst there is some evidence of tolerance to both salbutamol (Nelson 1977) and terbutaline (Weber 1982) other studies have been less conclusive (Harvey 1982; Lipworth 1989). However, evidence of tolerance to short and long‐acting beta2‐agonists in both protecting against and reducing bronchoconstriction is much stronger in the setting of an acute bronchoconstrictor challenge with chemical, allergen and 'natural' stimuli (Haney 2006; Lipworth 1997).

Studies comparing salmeterol and formoterol have shown that both cause tolerance compared to placebo but there was no significant difference between the drugs (van der Woude 2001). There also appears to be little difference in the tolerance induced by regular formoterol and regular salbutamol treatment (Hancox 1999; Jones 2001). To the authors' knowledge no studies have looked specifically at the degree of tolerance caused by isoprenaline and fenoterol in the setting of acute bronchoconstriction. Tolerance to bronchodilation has been shown to clearly occur with addition of inhaled corticosteroids to salmeterol and formoterol (Lee 2003) and terbutaline (Yates 1996). There is conflicting evidence as to whether high‐dose steroids can reverse tolerance in the acute setting (Jones 2001; Lipworth 2000).

At first glance the toxicity and tolerance hypotheses might appear incompatible as systemic and cardiovascular tolerance ought to protect against toxicity in the acute setting and there is good evidence that such tolerance occurs in stable asthmatic patients (Lipworth 1989). However, whilst this study showed that changes in heart rate and potassium levels were blunted by previous beta2‐agonist use, they were not abolished; furthermore, at the doses studied these side effects appear to follow an exponential pattern (Lipworth 1989). In contrast, in the presence of bronchoconstrictor stimuli the bronchodilator response to beta2‐agonists follows a flatter curve (Hancox 1999; Wong 1990) and as previously discussed this curve is shifted downwards by previous beta2‐agonist exposure (Hancox 1999). Thus, it is theoretically possible that in the setting of an acute asthmatic attack and strong bronchoconstricting stimuli, bronchodilator tolerance could lead to repetitive beta2‐agonist use and ultimately more systemic side effects than would otherwise have occurred. Of course, other sequelae of inadequate bronchodilation including airway obstruction will be detrimental in this setting.

Whilst the tolerance hypothesis is often cited as contributing towards the asthma mortality epidemics it is difficult to argue that reduced efficacy of a drug can cause increased mortality relative to a time when that drug was not used at all. However, tolerance to the bronchodilating effect of endogenous circulating adrenaline is theoretically possible and there is also evidence of rebound bronchoconstriction when stopping fenoterol (Sears 1990), which may be detrimental. Furthermore, it appears that regular salbutamol treatment can actually increase airway responsiveness to allergen (Cockcroft 1993) a potentially important effect that could form a variant of the toxicity hypothesis. Differences between beta2‐agonists in this regard are unclear, but the combination of rebound hyper responsiveness and tolerance of the bronchodilator effect with regular beta2‐agonist exposure has been recently advocated as a possible mechanism to explain the association between beta2‐agonists and asthma mortality (Hancox 2006).

Other explanations

Confounding by severity

Historically, this hypothesis has been used extensively to try to explain the association between mortality and the use of fenoterol during the 1970s New Zealand epidemic (see Pearce 2007) and is still quoted today. The hypothesis essentially relies on the supposition that patients with more severe asthma are more likely to take either higher doses of beta2‐agonists or a particular beta2‐agonist (such as fenoterol) thereby explaining the association. This hypothesis was carefully ruled out in the three case‐control studies by comparing the association between fenoterol and mortality in patients with varying severity of disease (Crane 1989; Grainger 1991; Pearce 1990). Furthermore, the hypothesis cannot explain the overall increase in mortality in the 1960s and 1970s nor can it explain any significant increase in mortality (whether taking inhaled steroids or not) from randomised controlled trial data.

The delay hypothesis