Abstract

Background

Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE) is the most common type of focal epilepsy in adults and can be successfully cured by surgery. One of the main complications of this surgery however is a decline in language abilities. The magnitude of this decline is related to the degree of language lateralization to the left hemisphere. Most fMRI paradigms used to determine language dominance in epileptic populations have used active language tasks. Sometimes, these paradigms are too complex and may result in patient underperformance. Only a few studies have used purely passive tasks, such as listening to standard speech.

Methods

In the present study we characterized language lateralization in patients with MTLE using a rapid and passive semantic language task. We used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study 23 patients [12 with Left (LMTLE), 11 with Right mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (RMTLE)] and 19 healthy right-handed controls using a 6 minute long semantic task in which subjects passively listened to groups of sentences (SEN) and pseudo sentences (PSEN). A lateralization index (LI) was computed using a priori regions of interest of the temporal lobe.

Results

The LI for the significant contrasts produced activations for all participants in both temporal lobes. 81.8% of RMTLE patients and 79% of healthy individuals had a bilateral language representation for this particular task. However, 50% of LMTLE patients presented an atypical right hemispheric dominance in the LI. More importantly, the degree of right lateralization in LMTLE patients was correlated with the age of epilepsy onset.

Conclusions

The simple, rapid, non-collaboration dependent, passive task described in this study, produces a robust activation in the temporal lobe in both patients and controls and is capable of illustrating a pattern of atypical language organization for LMTLE patients. Furthermore, we observed that the atypical right-lateralization patterns in LMTLE patients was associated to earlier age at epilepsy onset. These results are in line with the idea that early onset of epileptic activity is associated to larger neuroplastic changes.

Keywords: Hippocampal sclerosis, Epilepsy surgery, Functional neuroimaging, Plasticity, Aphasia

Background

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), the most common cause of intractable epilepsy in adults, can be successfully cured by surgery [1]. Partial removal of the anterior temporal lobe (ATL) remains the most common form of surgical treatment and is effective in 60-80% of patients [1-3]. A complication of surgery observed in 30-50% of patients after left ATL resection is a decline in language or verbal memory function [4-7]. The magnitude of decline is related to the degree of language lateralization to the left hemisphere and can be predicted using preoperative functional magnetic resonance imaging fMRI; [6-8].

A decrease of regional cerebral metabolism unilateral to the epileptogenic focus has been observed in patients with intractable TLE, usually in temporal and occasionally prefrontal regions [9]. Similarly, the reorganization of language may also affect different productive (located in frontal areas) and perceptive (located in temporal regions) language functions mainly in temporal rather than frontal areas [10,11]. Atypical functional lateralization for refractory epileptic patients during fMRI language tasks has been widely reported with either bilateral or right lateralized patterns of activation [12]. This is predominant in patients suffering from left mesial temporal lobe epilepsy LMTLE; [6,11,13-15].

Although the tasks employed by epilepsy institutes vary greatly, most fMRI paradigms used to determine the language dominance in epileptic populations include language production paradigms such as word or verb generation [11,13,15-18], object naming [14], or sentence repetition [11]. More complex paradigms involving semantic decisions have also been used [6,7,12,18,19]. All these paradigms require the patient to perform an active action (e.g., naming a word, making a semantic decision) which critically depends on his/her capacity to collaborate during the execution of the task. Paradigms that are too complex might result in patient underperformance, yielding poor activation patterns.

Surprisingly, only a few studies of epilepsy sufferers have used pure passive tasks such as listening to standard speech [11,20,21]. Passive listening paradigms reliably activate the receptive language cortex [22] making it possible to determine hemispheric dominance and identify the areas involved in language processing of TLE patients, which is of the utmost importance in pre-surgical language mapping [10,11]. These tasks commonly bring about activations in Wernicke's area –mainly the superior temporal gyrus (STG) and the middle temporal gyrus (MTG), frequently extending into the angular gyrus- but also in the primary auditory area and less often in frontal regions [11,20,23,24]. A study comprising healthy children [24] showed that both passive listening and active-response story processing yielded activations in the primary auditory cortex and the STG bilaterally and also in the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG). It has also been shown in TLE patients with atypical language patterns that plastic cortical reorganization can affect frontal and temporal language areas differently with greater reorganization of language circuits in the temporal rather than the frontal lobe [11,20]. This suggests that productive and receptive functions can be affected by the pathological process in different ways. In contrast with productive tasks, passive tasks are easy to perform, less dependent on patient collaboration and allow the assessment of how fronto-temporal networks contribute to other aspects of language processing. In addition, the pattern of activation of some receptive language paradigms can be as lateralized as that of verbal fluency or semantic decision tasks [11,20,22-25]. However, it is also well-known that using a baseline condition such as fixation or rest can lead to more bilateral activations [26].

The main purpose of this study is to investigate the reliability of a passive, non-collaboration dependent, semantic fMRI language task in evaluating language lateralization patterns in a group of selected left and right mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (RMTLE) patients. These results were compared to those of a well-matched healthy group. Based on previous studies, we expected to observe a clear increase of right-hemisphere lateralization associated to earlier age at epilepsy onset in LMTLE patients [12,27].

Methods

Participants

Twenty-three native Spanish patients (15 women) with refractory epilepsy of the temporal lobe were evaluated using an fMRI passive language paradigm. Twelve patients had a left hemispheric focus (LMTLE group) with the remaining eleven exhibiting the right (RMTLE group). All patients underwent pre-surgical evaluation which included long-term in-patient video-electroencephalogram (video-EEG) monitoring with clinical and EEG assessment, neuropsychological testing, brain MRI and psychiatric evaluation. All patients were considered good candidates for resective mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE) surgery. Twenty-two patients were right handed with only one left-handed right MTLE patient, as assessed by the Edinburgh handedness test [28]. Structural MRI on a 3 T Siemens Trio MRI system showed mesial temporal sclerosis in all patients with no other lesions found.

Nineteen healthy native Spanish subjects (9 women) were studied using the same fMRI and neuropsychological protocols. All controls were right handed as assessed by the Edinburgh handedness test [28] and had no record of neurological illness. None of the patients or controls had hearing disabilities.

We found no statistical differences between groups (n.s, all p > 0.4, see Table 1) in age (RMTLE, LMTLE, controls) or age at epilepsy onset (RMTLE, LMTLE). The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of University Hospital of Bellvitge and informed consent was obtained from all patients and controls.

Table 1.

Demographics, neuropsychological results and mean LI for each group and contrast

| LMTLE (n = 12) | RMTLE (n = 11) | Controls (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age |

40.50 ± 10.11 |

44.81 ± 13.51 |

40.68 ± 14.69 |

| Age at epilepsy onset |

14.94 ± 14.68 |

15.96 ± 12.01 |

- |

| Years of education |

11.08 ± 3.87 |

11.54 ± 2.91 |

14.52 ± 4.35 |

| Edinburg Handedness Inventory |

1.00 ± 0.00 |

1.45 ± 1.21 |

1.11 ± 0.32 |

| IQ |

92.50 ± 9.17 |

97.81 ± 11.19 |

106.35 ± 12.35 |

| BNT (SS) |

48.08 ± 6.15 |

51.27 ± 5.42 |

51.42 ± 8.80 |

| Phonemic fluency (SS)* |

13.08 ± 6.67 |

12.81 ± 6.17 |

15.21 ± 5.74 |

| Semantic fluency (SS)* |

18.08 ± 5.46 |

18.18 ± 4.19 |

19.78 ± 5.70 |

| Immediate verbal memory (SS)** |

30.08 ± 11.10 |

27.63 ± 6.12 |

32.68 ± 13.26 |

| Delayed verbal memory (SS)** |

14.91 ± 7.93 |

16.63 ± 5.57 |

20.42 ± 10.01 |

|

Lateralization index |

|

|

|

|

LI: SEN vs. Rest |

-0.32 ± 0.31 |

-0.10 ± 0.40 |

0.03 ± 0.34 |

| LI: PSEN vs. Rest | -0.41 ± 0.27 | -0.16 ± 0.29 | -0.08 ± 0.32 |

LMTLE, Left Temporal Lobe Epilepsy; RMTLE, Right Temporal Lobe Epilepsy; SS, scaled score; IQ, Intelligence Coefficient estimation; BNT, Boston Naming Test; *Subtests of the Barcelona test; **Subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale III; SEN, Passive Listening to Sentences; PSEN, Passive Listening to Pseudo Sentences.

All values are reported with mean and standard deviation. LIs lower than -0.4 are considered right lateralized, with LIs larger than 0.4 being considered left lateralized. LIs between -0.4 and 0.4 are considered bilateral.; For the handedness the scores were evaluated according to the following scale 1 = Right and 5 = Left; (for the interpretation of the results see methods section).

Neuropsychological testing

Neuropsychological data are summarized in Table 1. All patients and controls completed a set of subtests from the Wechsler Memory Scale III and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III (immediate and delayed verbal memory; immediate and delayed visual memory) [29]. The Boston Naming Test [30] and Semantic and Phonological fluency tests [31] were also carried out in order to explore naming abilities and verbal fluency. All these scores were compared to normative data, minimizing the possible bias of age and education in further statistical analysis. No statistical differences between the RMTLE group, LMTLE group and controls were found in any of the neuropsychological tests (n.s., all p > 0.15); however a marginal effect was found for years of education (n.s., p > 0.06). Following previous studies [6] we ensured that all participants had an IQ estimation ≥70, measured by the Vocabulary subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III.

MRI scanning

Images were acquired using a 3.0 Tesla Siemens Trio MRI system at the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona. A T1-weighted image (slice thickness = 1 mm; no gap; number of slices = 240; TR = 2300 ms; TE = 3 ms; matrix = 256 × 256; FOV = 244 mm) was acquired. Two functional runs of 90 echo-planar images were acquired using a single-shot T2*-weighted gradient-echo EPI sequence (slice thickness = 4 mm; no gap; number of slices = 32, interleaved order; TR = 2000 ms; TE = 29 ms; flip angle = 80°; matrix = 128×128; FOV = 240 mm; voxel size = 3 × 3 × 4 mm3).

Experimental design

Stimuli consisted of 20 well-formed Spanish sentences (SEN) containing 8 words (e.g., "En el museo hay una exposición de mariposas", meaning "There is an exhibition of butterflies in the museum") and 20 meaningless pseudo sentences (PSEN) (e.g., "An er sureo tas uma emdoriciós ne sacidosar"). PSENs were derived from well-formed sentences by substituting phonemes based on Spanish phonotactical rules, thus matching the original stimuli in phonemic complexity and length [32]. All stimuli were recorded using a native Spanish speaker reading the sentences. Patients were instructed to listen carefully to the stimuli as they would be required to answer some questions at the end of the session.

The stimuli was presented over two runs of a blocked design paradigm. Each run contained three experimental conditions: passive listening to SENs, passive listening to PSENs and rest. SEN and PSEN blocks contained 5 sentences each, with a total block duration of 30 seconds and were each followed by 15 second rest periods. Each run contained two blocks of SEN and PSEN conditions and 4 of rest, yielding a total task duration of 6 minutes over the two runs.

fMRI analysis and Lateralization Index calculation

Analysis of fMRI data was carried out using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM8; Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, University College, London, UK, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and MATLAB 7.8.0 (The MathWorks Inc, Natick, Mass). Echo-planar imaging (EPI) volumes were first spatially realigned and resliced with respect to the first volume of the first run. Each participant’s T1 image was coregistered to the mean EPI volume produced in the previous spatial realignment step. Then, using each coregistered T1 scan, the normalization parameters needed to transform the data to MNI152 space were obtained by means of Unified Segmentation [33], which combines segmentation, bias correction and spatial normalization under the same iterative model. This method has been successfully applied to both healthy and patient populations [34]. Finally, normalized EPI images were resliced to 2 × 2 × 2 mm and smoothed with an 8 mm full-width at half-maximum isotropic Gaussian kernel.

A general linear model was created using SEN, PSEN and rest conditions and the motion parameters extracted from the realignment phase. After model estimation, statistical parametrical maps for the SEN and PSEN conditions versus rest and for SEN versus PSEN were created. The first objective of this study was to assess whether a passive semantic task as the one presented could elicit robust activation of the temporal lobe at the subject-level. Thus, individual first level contrasts were inspected in order to compare the activations in individual subjects between active task and rest contrasts (SEN vs. rest, PSEN vs. rest) and contrasts involving only active blocks (SEN vs. PSEN) using a p < 0.001 uncorrected threshold with 20 voxels of cluster extent. The SEN vs. PSEN contrast did not elicit significant differences in around 40% of the subjects (see Results) and no laterality indexes or group contrasts were derived. No further analysis was conducted here as a contrast that shows no robust activations in all participants is of poor clinical use.

Active versus rest contrasts (PSEN vs. rest and SEN vs. rest) however elicited activations at the subject level in 100% of the participants (see Results) and were therefore both well-suited for clinical use. Group activations were then calculated using a one-sample t-test. These contrasts were calculated to provide a general idea of the pattern of activations in each group and therefore are reported at a false discovery rate corrected (FDR-corrected) p < 0.05 threshold with 20 voxels of cluster extent, to correct for multiple comparisons.

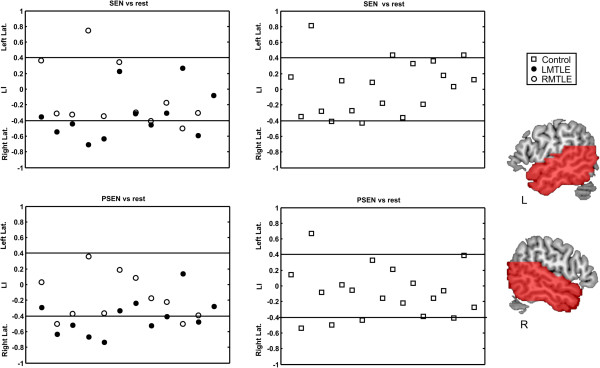

For each subject and for both PSEN vs. rest and SEN vs. rest contrasts, a Lateralization Index (LI) was calculated using a region of interest (ROI) which included the STG, MTG, inferior temporal gyri (ITG) and the anterior temporal lobe [35]; see Figure 1. The rationale behind this anatomical selection is based on the importance of ATL regions in MTLE patients, areas which are typically resected for epilepsy treatment [10,11]. The ROIs were generated using the Automated Anatomical Atlas [36] and the toolbox WFU PickAtlas [37,38]. The LI is calculated as:

Figure 1.

Individual LIs for each participant and for both SEN vs. Rest and PSEN vs. Rest contrasts. LIs under -0.4 are considered right lateralized, with LIs being larger than 0.4 being considered left lateralized. LIs between -0.4 and 0.4 are considered bilateral. On the right side the ROIs used to calculate the LIs are overlaid on red over a canonical MNI template. PSEN, Passive Listening to Pseudo Sentences; SEN, Passive Listening to Sentences; LMTLE, Left Temporal Lobe Epilepsy; RMTLE, Right Temporal Lobe Epilepsy; L, Left Hemisphere; R, Right Hemisphere.

| (1) |

Thus, the LI ranges between 1 for extreme left lateralized activations and -1 for total right lateralization patterns. In other words, an LI greater than 0.4 means that at least 70% (following eq. 1, 0.4 = [30]/100) of activation is left lateralized, while a LI below -0.4 implies that at least 70% of activation (-0.4 = [30-70]/100) is in the right hemisphere. This criterion was the threshold selected to classify a pattern of activation as left or right lateralized with LIs between 0.4 and -0.4 being considered bilateral. LIs were derived using the bootstrapped method (in which no threshold needs to be specified as this particular algorithm is threshold-independent) of the LI-toolbox [39], in which 10.000 LIs per subject were iteratively calculated at different thresholds using voxel values and clustering, yielding a robust LI.

A one-way ANOVA on LIs was performed to check for a significant group effect (RMTLE, LMTLE, controls). Two sample t-tests were also calculated between pairs of groups to evaluate significant differences in their mean LI. LIs were also correlated with the age at epilepsy onset and all neuropsychological variables (for each group and pooling all the groups together) using Pearson's linear correlation. For significant correlations and trends, 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using 10.000 permutations. In this manner, if CIs are greater than zero, the probability of the correlation being non significant is reduced to 5%.

Results

fMRI results

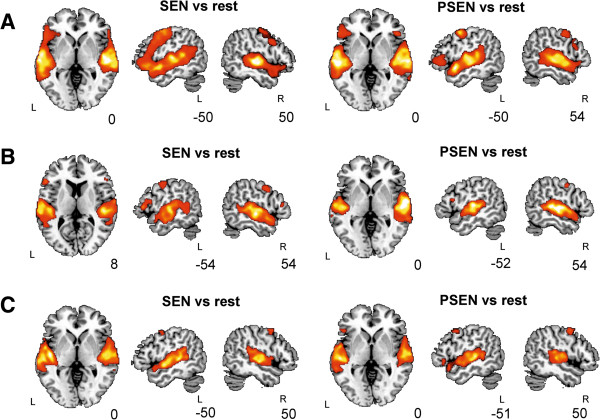

Task vs. rest contrasts (SEN vs. rest, PSEN vs. rest) thresholded at p < 0.001 uncorrected with 20 voxels of cluster extent and elicited clear activations in the STG and MTG bilaterally in all patients and controls (42 subjects in total, see Figure 2 and Tables 2, 3 and 4 for descriptions of each contrast of interest per group and Figure 3 for single case examples). The contrast between SEN vs. PSEN failed to show significant activations in any cortical region in 4 out of 11 (36%) RMTLE patients, 5 out of 12 (42%) LMTLE patients and in 8 out of 19 (42%) controls and thus was not analyzed any further.

Figure 2.

Whole brain fMRI activations for the three groups. Results are shown over an MNI template, at a p < 0.05 FDR-corrected threshold with 20 voxels of cluster extent using neurological convention. A. Healthy participants B. LMTLE patients. C. RMTLE patients. PSEN, Passive Listening to Pseudo Sentences; SEN, Passive Listening to Sentences; L, Left hemisphere; R, Right hemisphere.

Table 2.

Main fMRI results on the functional tasks for the control group

|

Side |

Cluster size (mm3) | t value |

Peak coordinate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

|

Healthy population | ||||||

| SEN vs. rest | ||||||

| STG/MTG/HG/IFG |

R |

40112 |

16.88 |

56 |

-20 |

0 |

| STG/MTG/HG/IFG/PG |

L |

81928 |

14.64 |

-62 |

-16 |

-6 |

| SMA |

L/R |

7096 |

8.85 |

-4 |

4 |

66 |

| PG |

R |

5560 |

5.30 |

56 |

12 |

30 |

| PSEN vs. rest | ||||||

| STG/MTG/HG/ |

L |

46552 |

16.47 |

-58 |

-24 |

2 |

| STG/MTG/HG/ |

R |

45952 |

13.47 |

42 |

-20 |

6 |

| PG/PC |

L |

3264 |

9.04 |

-50 |

-2 |

52 |

| IFG |

L |

4936 |

5.47 |

-54 |

30 |

0 |

| IFG |

R |

1264 |

5.27 |

60 |

22 |

20 |

| PG | R | 1328 | 4.04 | 54 | 0 | 46 |

All peak values reported were significant at p < 0.05 FDR-corrected at voxel level, 20 voxels spatial extent. Peak coordinates of each cluster are reported in MNI coordinates. STG, Superior Temporal Gyrus; MTG, Middle Temporal Gyrus; HG, Heschl Gyrus; PC, Postcentral Gyrus; PG, Precentral Gyrus; SMA, Supplementary Motor Area; IFG, Inferior Frontal Gyrus.PSEN, Passive Listening to Pseudo Sentences; SEN, Passive Listening to Sentences; L, Left hemisphere; R, Right hemisphere.

Table 3.

Main fMRI results on the functional tasks for RMTLE group

|

Side |

Cluster size (mm3) | t value |

Peak coordinate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

|

RMTLE | ||||||

| SEN vs. rest | ||||||

| STG/MTG/HG |

R |

21912 |

12.83 |

60 |

-8 |

8 |

| STG/MTG/HG/ |

L |

27280 |

12.49 |

-54 |

-28 |

4 |

| PG |

R |

6528 |

7.42 |

52 |

2 |

54 |

| PG |

L |

712 |

5.18 |

-50 |

8 |

52 |

| IFG |

L |

432 |

4.78 |

-46 |

26 |

2 |

| SMA |

L/R |

424 |

4.74 |

4 |

6 |

60 |

| PSEN vs. rest | ||||||

| STG/MTG/HG |

L |

33216 |

13.92 |

-54 |

-30 |

6 |

| STG/MTG/HG/ |

R |

28256 |

11.89 |

62 |

-24 |

6 |

| PG |

R |

584 |

5.76 |

54 |

6 |

48 |

| SMA |

L/R |

256 |

5.11 |

4 |

0 |

68 |

| PG | L | 248 | 4.88 | -54 | -2 | 50 |

All peak values reported were significant at p < 0.05 FDR-corrected at voxel level, 20 voxels spatial extent. Peak coordinates of each cluster are reported in MNI coordinates. STG, Superior Temporal Gyrus; MTG, Middle Temporal Gyrus; HG, Heschl Gyrus; PG, Precentral Gyrus; SMA, Supplementary Motor Area; IFG, Inferior Frontal Gyrus. PSEN, Passive Listening to Pseudo Sentences; SEN, Passive Listening to Sentences; L, Left hemisphere; R, Right hemisphere.

Table 4.

Main fMRI results on the functional tasks for LMTLE group

|

Side |

Cluster size (mm3) | t value |

Peak coordinate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

|

LMTLE | ||||||

| SEN vs. rest | ||||||

| STG/MTG/HG |

R |

28952 |

14.90 |

62 |

-18 |

4 |

| STG/MTG/HG/ |

L |

26344 |

12.71 |

-64 |

-28 |

6 |

| PG/PC |

L |

1832 |

7.70 |

-46 |

-10 |

56 |

| IFG |

L |

1504 |

7.13 |

-54 |

28 |

8 |

| PG |

R |

1424 |

5.36 |

60 |

0 |

40 |

| IFG |

R |

208 |

4.75 |

52 |

30 |

12 |

| SMA |

L/R |

424 |

4.56 |

2 |

0 |

64 |

| PSEN vs. rest | ||||||

| STG/MTG/HG |

R |

29064 |

23.58 |

58 |

-16 |

4 |

| STG/MTG/HG/ |

L |

21416 |

16.56 |

-62 |

-28 |

10 |

| PG |

R |

480 |

5.42 |

56 |

-2 |

42 |

| IFG | L | 424 | 4.49 | -52 | 16 | 18 |

All peak values reported were significant at p < 0.05 FDR-corrected at voxel level, 20 voxels spatial extent. Peak coordinates of each cluster are reported in MNI coordinates. STG, Superior Temporal Gyrus; MTG, Middle Temporal Gyrus; HG, Heschl Gyrus; Postcentral Gyrus; PG, Precentral Gyrus; SMA, Supplementary Motor Area; IFG, Inferior Frontal Gyrus. PSEN, Passive Listening to Pseudo Sentences; SEN, Passive Listening to Sentences; L, Left hemisphere; R, Right hemisphere.

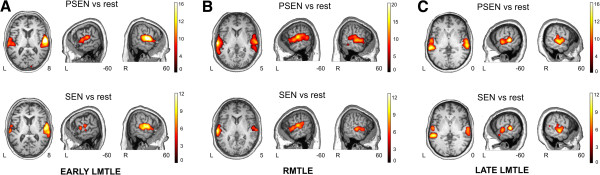

Figure 3.

Whole brain fMRI activations for three representative patients. Results are shown over a patient's T1, at a p < 0.05 FDR-corrected threshold with 20 voxels of cluster extent using neurological convention. A. Patient 9 from the LMTLE group (woman, 63 years old, age at epilepsy onset at 3 years, LI for PSEN -0.65, LI for SEN -0.77). B. Patient 14 from the RMTLE group (man, 23 years old, age at epilepsy onset at 0.66 years, LI for PSEN 0.19, LI for SEN 0.35). C. Patient 27 from the LMTLE group (woman, 48 years old, age at epilepsy onset at 32 years, LI for PSEN 0.14, LI for SEN 0.27). PSEN, Passive Listening to Pseudo-sentences; SEN, Passive Listening to Sentences; L, Left hemisphere; R, Right hemisphere.

Lateralization index

The mean LI and standard deviation for each group and condition can be found in Table 4, while individual LIs are shown for every participant and both SEN vs. rest and PSEN vs. rest contrasts in Figure 1.

For the SEN vs. rest contrast, a one-way ANOVA analysis on LIs showed a significant group effect (F(2,39) = 3.69 p < 0.035). The predominant pattern of activations was bilateral for controls (mean LI 0.03, 3 subjects left lateralized, 1 right dominant and 15 bilateral) and RMTLE patients (mean LI -0.10, 1 patient left lateralized, 1 right lateralized and 9 bilateral). LMTLE patients (6 patients with right hemispheric dominance and 6 bilateral) showed the most right lateralized pattern of activation (mean LI -0.32, 65% of activation in right temporal lobe) which was significantly more right lateralized than controls (t(29) = -2.87, p < 0.008). No significant differences were found between the mean LI of LMTLE and RMTLE patients (t(21) = -1.44, p > 0.16) or RMTLE patients and controls (t(28) = -0.98, p > 0.33). Correlations between LIs for this contrast and age at epilepsy onset for the RMTLE patients were not significant (r = -0.15, p > 0.65). However, for the LMTLE group a small trend was observed (r =0.40, p > 0.19, bootstrapped CIs -0.20/0.88). No other significant correlations or marginal effects were found (all p > 0.20).

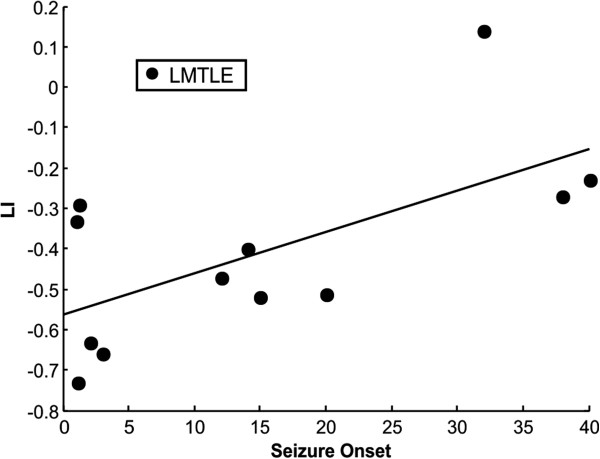

One-way ANOVA analysis on LIs in the PSEN vs. rest contrast also showed a significant group effect (F(2,39) = 4.67 p < 0.015). For controls (mean LI -0.08, 1 subject with left hemispheric dominance, 3 right lateralized and 15 bilateral) and RMTLE patients (mean LI -0.16, 2 patients right lateralized and 9 bilateral) bilateral activation was commonly observed. LMTLE patients (6 patients with right hemispheric dominance and 6 bilateral) showed, once again, the most right lateralized pattern of activation (mean LI -0.41, 70% of the activation in the right temporal lobe) which was significantly more right lateralized than controls (t(29) = -3.03, p < 0.005) and RMTLE patients (t(21) = -2.18, p < 0.041). No significant differences were found between the mean LI of RMTLE patients and controls (t(28) = -0.73, p > 0.47). The correlation between LIs for the PSEN contrast and age at epilepsy onset for RMTLE patients was not significant (r = -0.1, p > 0.76), whereas for the LMTLE group a significant correlation was found (see Figure 4) (r = 0.63, p < 0.03, bootstrapped CIs 0.16/0.93). No other significant correlations were found (all p > 0.20).

Figure 4.

On the left side, LIs correlation for the PSEN vs. rest of LMTLE patients and their epilepsy onset age (r = 0.63, p < 0.03).

Individual cases of interest

In order to illustrate the results, Figure 3 shows the main activations for SEN vs. rest and PSEN vs. rest contrasts for three representative patients. To emphasize the strength of the activations found in the temporal lobe at the subject-level, an FDR-corrected p < 0.05 threshold with 20 voxels of spatial extent was used to show the activations in these particular three subjects. Figure 3A shows the results of Patient 9, a 63 year old woman suffering from LMTLE with an early epilepsy debut (3 years), showing a strongly right lateralized activation pattern in both PSEN (LI -0.65, 82.5% of activation in the right temporal lobe) and SEN conditions (LI -0.77, 88.5% of activation in the right temporal lobe). Figure 3B shows the results of Patient 14, a 23 year old man suffering RMTLE with early epilepsy debut (0.66 years), showing bilateral (slightly left lateralized) activation in both PSEN (LI 0.19, 59.5% of activation in the left temporal lobe) and SEN conditions (LI 0.35, 67.5% of activation in the left temporal lobe). Figure 3C shows the results of Patient 27, a 48 year old woman suffering LMTLE with late epilepsy debut (32 years), showing bilateral activation in both PSEN (LI 0.14, 57% of activation in the left temporal lobe) and SEN conditions (LI 0.27, 63.5% of activation in the left temporal lobe).

Discussion

In line with previous intracarotid amobarbital procedure data and consistent with our findings, several fMRI studies have suggested that atypical dominance patterns are more frequent in epileptic patients [12,17,19,40] and may predominate in patients with epilepsy of left hemispheric origin [13,19,41]. A previous study [41] showed that 24% of LMTLE patients with HS had atypical language dominance and more importantly that this atypical language representation was associated with both a higher frequency of interictal discharges and with sensory auras representing seizure propagation to lateral temporal structures. It has been suggested that propagation of seizures from the epileptic focus to different brain regions triggers cortical plasticity not only around the focus but also in remote areas either ipsilateral or contralateral to the epileptic focus [13,14,17,19,40]. It would therefore appear that the language network is particularly vulnerable to chronic epileptic activity. Moreover, an inter-hemispheric dissociation of frontal and temporal language regions in patients with focal epilepsy has also been described [10,11,20,42-44]. In a previous study, 29 (20.1%) out of 144 patients with medically intractable complex-partial seizures showed bilateral language representation after intracarotid amobarbital test assessment [10] and more importantly, 4 (2.8%) of these patients -2 of them with TLE- had strong evidence of an interhemispheric dissociation of expressive and receptive language functions. These findings have been posteriorly confirmed by several functional neuroimaging studies [11,20,42-44], which all support the hypothesis that reorganization can affect frontal and temporal language areas differently in patients with atypical language patterns.

Paradigms used for clinical language mapping vary greatly in different centres and no accepted standardized technique exists. Most fMRI language dominance studies in epileptic patients have used active language tasks [13-18]. However, imaging studies have confirmed that the laterality indexes yielded by receptive language paradigms can be as lateralized as those of active tasks [11,20,22-25]. In this way, and similarly to other passive listening semantic paradigms used on TLE patients [11,20,21], we show how passive contrasts such as listening to SENs or PSENs versus baseline are able to unravel and clarify atypical language patterns in LMTLE patients. Mean LI was significantly more right lateralized for LMTLE patients than controls when listening to SENs and again more right lateralized for LMTLE than for both controls and RMTLE patients when listening to PSENs (see Figure 1 and Table 1). While LI was mainly bilateral for the controls (79% of subjects for both SEN and PSEN conditions) and for RMTLE patients (81.8% of patients, for both SEN vs. rest and PSEN vs. rest conditions), 6 out of 12 patients of the LMTLE group showed a right lateralized activation for both contrasts (50% of patients).

It is important to note that this passive listening task is very easy and rapid to perform (only 6 minutes of fMRI acquisition) and that both task-rest contrasts produced robust activations of the temporal lobe for every one of the 42 participants studied. Interestingly, the SEN vs. PSEN contrast failed to elicit robust responses in 42% of LMTLE patients and controls and in 36% of RMTLE patients. These results are consistent with other passive paradigms using direct speech contrast between two active conditions, which also failed to show significant activations in several subjects. In a previous study [11], a direct contrast between two active conditions (Listening Stories vs. Listening Reversed Stories) produced no significant activation in 22% of RMTLE and LMTLE patients and 12% of healthy subjects. Interestingly, in another study [35], activation in 100% of subjects failed to reach significance in the direct contrast between two active conditions (listening to Words, Pseudowords and Reversed Speech).

In accordance with the present results, there is extensive functional imaging data suggesting that language comprehension is subserved by a large cortical network involving both temporal cortices [45-52]. Many neuroimaging studies reveal weak neural activity in the right hemisphere in the anatomically equivalent areas to those of the left hemisphere which show a strong signal during language tasks [48,51]. Additionally, some patients with right brain damage have deficits in comprehending natural language [48]. All these data support the idea that although the left hemisphere plays a crucial role in language processing, the right hemisphere also contributes to language comprehension [45,48,50,51,60]. Hence, the bilateral pattern of temporal lobe activation in controls and MTLE patients using this passive semantic paradigm agrees with previous functional imaging data showing that the STG and MTG are activated bilaterally by both speech and complex non-speech sounds [20,32,35,45,53-61]. Even when the auditory stimuli is novel and no meaning extraction is possible (as in the PSEN condition) both the MTG and STG show enhanced activations [62,63]. In fact, some studies have shown that activation at the level of the auditory cortex is neither modulated by the semantic content ("meaningfulness") of stimuli nor by the type of cognitive task performed [64]. Moreover, in a previous study [35] Words, Pseudowords and Reversed Speech versus baseline bilaterally activated both temporal lobes, yielding less than 2 ml of volumetric difference in activation between hemispheres (the only contrast that showed a significant difference in activation in temporal lobes was Words vs. rest with an LI of 0.11, therefore showing a bilateral distribution). It is also well known that that using a baseline condition such as fixation or rest (as in the SEN vs. rest and PSEN vs. rest contrast) yields bilateral functional patterns and LI values around zero [26]. There is also experimental and clinical evidence showing bilateral activation in conceptual processing [65].

Furthermore, a significant correlation between LI and age at epilepsy onset was found for the PSEN condition versus baseline (LIs for SEN vs. rest contrast also yielded a trend). There is a gradual decline in the potential for plasticity with age [12,27], but no particular age after which plasticity becomes absolutely impossible [66]. Visual inspection of patients with LMTLE and early onset clearly showed a right lateralized pattern (Figure 3A), while subjects suffering from RMTLE or LMTLE with late epilepsy debut showed a more bilateral pattern (Figure 4B and 4C, respectively). It is important to note that a correlation between age at epilepsy onset and LI has been previously described using a semantic decision task [12]. This gives additional support to the usefulness of a simple passive language task like the one described in this study.

Previous studies using language fMRI with productive and receptive tasks have shown how in TLE patients with atypical language patterns, reorganization affected frontal and temporal language areas differently, with temporal LIs being more right lateralized than frontal ones [10,11,20,42-44]. Moreover, data from lesion and neuroimaging studies suggests that comprehension or semantic activation -involving retrieval and selection of semantic information- depends on a wide cortical network, larger than Wernicke's or even Broca’s area (which is required particularly for the correct processing of complex morphosyntactic structures) [67]. Furthermore, there are several patient studies supporting the involvement of the anterior superior temporal lobe for sentence-level comprehension [45,65,67,68]. Semantic knowledge stores are diffusely located in ventral temporal (MTG, ITG, fusiform gyrus, temporal pole) and inferior parietal (angular gyrus) cortices, in addition to the classic posterior STG and planum temporale [23,45,48,50,69,70]. Therefore, as both the ventral and anterior temporal lobes are related to receptive language and TLE surgery (ATL) commonly involves the resection of these regions of the temporal lobe, we hypothesize that the passive semantic paradigm presented here -which mainly activates temporal lobe structures- is more precise in predicting semantic language defects, such as naming retrieval or verbal memory decline, in TLE patients who undergo surgery [4,23,70-76]. In addition, this paradigm may also provide important information about the extent of functional reserves in the contralateral hemisphere [20] and might be helpful in tailoring the resection of temporal lesions with the aim of preserving eloquent areas of the brain. We cannot omit however that a limitation of this study is the lack of comparison to other laterality measurements yielded by more classical non-passive language paradigms. Also, a larger sample of patients might have allowed us to compute a more detailed analysis of the LIs within the temporal lobes by dividing the MTL into different sections (i.e., anterior/posterior).

Conclusions

In summary, the simple, rapid, non-collaboration dependent, passive task described in this study produces a robust activation in the temporal lobe in both TLE patients and controls and illustrates a pattern of atypical language organization specifically in LMTLE patients.

Financial disclosure statement and acknowledgments

This research has been supported by a predoctoral grant from the Spanish Government (FPU program AP2010-4179) to P.R., a predoctoral grant from Generalitat de Catalunya to D.L-B. (2010FI B1 00169), a predoctoral grant from the Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (program 06/IDB-001) to A.V.B., a Ramon y Cajal research program grant awarded to J.M.P. (RYC-2007-01614), Spanish Government grants (MICINN, PSI2011-29219 to A.R.F., PSI2009-09101 to J.M.P. and PSI2008-03885 to R.D.B.) and a grant from the Catalan Government (2009 SGR 93).We would like to thank all patients and healthy volunteers for their participation.

Competing interests

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design (PR, JM, MF, ARF, JMP, RdDB); acquisition of data (JM, PR, MF, AV, DLB, MJ); drafting of the manuscript (PR, JM, ARF); analysis and interpretation of data (PR, JM); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (ARF, JMP, AV, PR, RdDB, DLB, MJ, MF, JM); statistical expertise (PR, ARF, JMP); administrative, technical, or material support (RdDB, JMP, PR, JM); study supervision (MF, ARF). All authors red and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Júlia Miró, Email: jmiro@bellvitgehospital.cat.

Pablo Ripollés, Email: pablo.ripolles.vidal@gmail.com.

Diana López-Barroso, Email: dlopezbarroso@gmail.com.

Adrià Vilà-Balló, Email: adria.vila.ballo@gmail.com.

Montse Juncadella, Email: mjuncadella@bellvitgehospital.cat.

Ruth de Diego-Balaguer, Email: ruth.de.diego@gmail.com.

Josep Marco-Pallares, Email: josepmarco@hotmail.com.

Antoni Rodríguez-Fornells, Email: arfornells@gmail.com.

Mercè Falip, Email: mfalip@bellvitgehospital.cat.

References

- Wiebe S, Blume WT, Girvin JP, Eliasziw M. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:311–318. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh AM, Wilson SJ, Berkovic SF. Seizure outcome after temporal lobectomy: current research practice and findings. Epilepsia. 2001;42:1288–1307. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellez-Zenteno JF, Dhar R, Wiebe S. Long-term seizure outcomes following epilepsy surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain May. 2005;128:1188–1198. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter C, Elger CE. Cognitive consequences of two-thirds anterior temporal lobectomy on verbal memory in 144 patients: a three-month follow-up study. Epilepsia. 1996;37:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup E, Langfitt J, Berg M, McDermott M, Pilcher W, Como P. Predicting verbal memory decline following anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) Neurology. 2003;60:1266–1273. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000058765.33878.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabsevitz DS, Swanson SJ, Hammeke TA, Spanaki MV, Possing ET, Morris GL, Mueller WM, Binder JR. Use of preoperative functional neuroimaging to predict language deficits from epilepsy surgery. Neurology. 2003;60:1788–1792. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000068022.05644.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Sabsevitz DS, Swanson SJ, Hammeke TA, Raghavan M, Mueller WM. Use of preoperative functional MRI to predict verbal memory decline after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1377–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR. Functional MRI, is a valid noninvasive alternative to Wada testing. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;20:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokeit H, Seitz RJ, Markowitsch HJ, Neumann N, Witte OW, Ebner A. Prefrontal asymmetric interictal glucose hypometabolism and cognitive impairment in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 12):2283–2294. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.12.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurthen M, Helmstaedter C, Linke DB, Solymosi L, Elger CE, Schramm J. Interhemispheric dissociation of expressive and receptive language functions in patients with complex-partial seizures: an amobarbital study. Brain Lang. 1992;43:694–712. doi: 10.1016/0093-934X(92)90091-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thivard L, Hombrouck J, du Montcel ST, Delmaire C, Cohen L, Samson S, Dupont S, Chiras J, Bualc M, Lehericy S. Productive and perceptive language reorganization in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2005;24:841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer JA, Binder JR, Hammeke TA, Swanson SJ, Frost JA, Bellgowan PS, Brewer CC, Perry HM, Morris GL, Mueller WM. Language dominance in neurologically normal and epilepsy subjects: a functional MRI study. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 11):2033–2046. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.11.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adcock JE, Wise RG, Oxbury JM, Oxbury SM, Matthews PM. Quantitative fMRI assessment of the differences in lateralization of language-related brain activation in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2003;18:423–438. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(02)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berl MM, Balsamo LM, Xu B, Moore EN, Weinstein SL, Conry JA, Pearl PL, Sachs BC, Grandin CB, Frattali C, Ritter FJ, Sato S, Theodore WH, Gaillar WD. Seizure focus affects regional language networks assessed by fMRI. Neurology. 2005;65:1604–1611. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000184502.06647.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janszky J, Mertens M, Janszky I, Ebner A, Woermann FG. Left-sided interictal epileptic activity induces shift of language lateralization in temporal lobe epilepsy: an fMRI study. Epilepsia. 2006;47:921–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli SB, Thompson PJ, Yogarajah M, Vollmar C, Powell RH, Symms MR, McEvoy AW, Micallef C, Koepp MJ, Duncan JS. Imaging language networks before and after anterior temporal lobe resection: Results of a longitudinal fMRI study. Epilepsia. 2012;53:639–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woermann FG, Jokeit H, Luerding R, Freitag H, Schulz R, Guertler S, Okujava M, Wolf P, Tuxhorn I, Ebner A. Language lateralization by Wada test and fMRI in 100 patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 2003;61:699–701. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000078815.03224.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Holland SK, Jacola LM, Lindsell C, Privitera MD, Szaflarski M. Comprehensive presurgical functional MRI language evaluation in adult patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger LR, Zeck J, Berl MM, Moore EN, Ritzl EK, Shamim S, Weinstein SL, Conry JA, Pearl PL, Sato S, Vezina LG, Theodore WH, Gaillar WD. Interhemispheric and intrahemispheric language reorganization in complex partial epilepsy. Neurology. 2009;72:1830–1836. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a7114b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives-Deliperi VL, Butler JT, Meintjes EM. Functional MRI language mapping in pre-surgical epilepsy patients; findings from a series of patients in the Epilepsy Unit at Mediclinic Constantiaberg. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(8):563–567. doi: 10.7196/samj.6336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannest J, Szaflarski JP, Eaton KP, Henkel DM, Morita D, Glauser TA, Byars AW, Patel K, Holland SK. Functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals changes in language localization in children with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(4):435–445. doi: 10.1177/0883073812447682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits M, Visch-Brink E, Schraa-Tam CK, Koudstaal PJ, van der Lugt A. Functional MR imaging of language processing: an overview of easy-to-implement paradigms for patient care and clinical research. Radiographics. 2006;26(Suppl 1):S145–S158. doi: 10.1148/rg.26si065507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Swanson SJ, Hammeke TA, Sabsevitz DS. A comparison of five fMRI protocols for mapping speech comprehension systems. Epilepsia. 2008;49(12):1980–1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannest JJ, Karunanayaka PR, Altaye M, Schmithorst VJ, Plante EM, Eaton KJ, Rasmussen JM, Holland SK. Comparison of fMRI data from passive listening and active-response story processing tasks in children. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29(4):971–976. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JS. Imaging in the surgical treatment of epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(10):537–550. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghier ML. Laterality index in functional MRI : methodological issues. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26(5):594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazdil M, Zakopcan J, Kuba R, Fandrdolya Z, Rector I. Atypical hemispheric language dominance in left temporal lobe epilepsy as a result of the reorganization of language functions. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:414–419. doi: 10.1016/S1525-5050(03)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WMS III. Escala de memoria de Wechsler-III. Madrid: TEA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EF, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Casanova J. Integrated neuropsychological exploration program- Barcelona test revised. Barcelona: Masson; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Saur D, Kreher BW, Schnell S, Kummerer D, Kellmeyer P, Vry MS, Umaroya R, Glauche V, Abel S, Huber W, Rijntjes M, Hennig J, Weiller C. Ventral and dorsal pathways for language. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18035–18040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805234105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage. 2005;26:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripolles P, Marco-Pallares J, de Diego-Balaguer R, Miro J, Falip M, Juncadella M, Rubio F, Rodriguez-Fornells A. Analysis of automated methods for spatial normalization of lesioned brains. Neuroimage. 2012;60:1296–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Frost JA, Hammeke TA, Bellgowan PS, Springer JA, Kaufman JN, Possing ET. Human temporal lobe activation by speech and nonspeech sounds. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:512–528. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.5.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1233–1239. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Burdette JH. Precentral gyrus discrepancy in electronic versions of the Talairach atlas. Neuroimage. 2004;21:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke M, Lidzba K. LI-tool: a new toolbox to assess lateralization in functional MR-data. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;163:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger MJ, Cole J. Language organization and reorganization in epilepsy. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21(3):240–251. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9180-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janszky J, Jokeit H, Hienemann D, Schultz R, Woermann FG, Ebner A. Epileptic ctivitiy influences the speec organization in medial temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2003;126(9):2043–2205. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baciu MV, Watson JM, McDermott KB, Baciu MV, Watson JM, McDermot KB, Wetzel RD, Attarian H, Moran CJ, Ojemann JG. Functional MRI reveals an interhemispheric dissociation of frontal and temporal language regions in a patient with focal epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:776–780. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutten GJ, Ramsey NF, van Rijen PC, Alpeherts WC, van Veelen CW. fMRI-determined language lateralization in patients with unilateral or mixed language dominance according to the Wada test. Neuroimage. 2002;17(1):447–460. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreer J, Arnold S, Quiske A, Wohlfarth R, Ziyeh S, Altenmuller D, Herpers M, Kassubek J, Klisch J, Steinhoff BJ, Honegger J, Schulze Bonhage A, Schumacher M. Determination of hemiphere dominance for language: comparion of frontal and temporal fMRI activation with intracarotid amytal testing. Neuroradil. 2002;44:467–474. doi: 10.1007/s00234-002-0782-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries C, Willard K, Buchsbaum B, Hickok G. Role of anterior temporal cortex in auditory sentence comprehension: an fMRI study. Neuroreport. 2000;12:1749–1752. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200106130-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonet JF, Chollet F, Ramsay S, Cardebat D, Nspoulous JL, Wise R, Rascol A, Frackowiak R. The anatomy of phonological and semantic processing in normal subjects. Brain. 1992;115:1753–1768. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.6.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ, Evans AC, Meyer E, Gjedde A. Lateraliztion of phonetic and pitch discrimination in speech processing. Science. 1992;256:846–849. doi: 10.1126/science.1589767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookheimer S. Functional MRI, of language: New approaches to understanding the cortical organization of semantic processing. Ann Rev Neursci. 2002;25:151–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici AD, Rüschemeyer SA, Habne A, Eiebach CJ. The role of left inferior frontal and superior temporal cortex in sentence comprehension: localizing syntactic and semantic processes. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13(2):170–177. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Beeman M. Bilateral brain processes for comprehending natural language. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(11):512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Kemeny S, Park G, Frattali C, Braun A. Language in context: emergent features of word sentence, and narrative comprehension. Neuroimage. 2005;25:1002–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidzba K, Schwilling E, Grodd W, Krägeloh-Mann I, Wilke M. Language comprehension vs. language production:age effects on fMRI activation. Brain Lang. 2011;119(1):6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazoyer B, Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Frak V, Mazoyer BM, Tzourio N, Frak V, Syrota A, Murayama N, Levrier O, Salamon G, Dehaene S, Cohen L, Mehler J. The cortical representation of speech. J Cogn Neurosc. 1993;5:467–479. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1993.5.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G, Poeppel D. Towards a functional neuroanatomy of speech perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4:131–138. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ. The anatomy of language: a review of 100 fMRI studies published in 2009. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1191:62–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestres-Misse A, Camara E, Rodriguez-Fornells A, Rotte M, Munte TF. Functional neuroanatomy of meaning acquisition from context. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008;20:2153–2166. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G, Poeppel D. Dorsal and ventral streams: a framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition. 2004;92:67–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeppel D, Hickok G. Towards a new functional anatomy of language. Cognition. 2004;92:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani M, Jones DK, Ffytche DH. Perisylvian language networks of the human brain. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:8–16. doi: 10.1002/ana.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonet JF, Thierry G, Cardebat D. Renewal of the neurophysiology of language: functional neuroimaging. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:49–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Fornells A, Cunillera T, Mestres-Misse A, de Diego-Balaguer R. Neurophysiological mechanisms involved in language learning in adults. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:3711–3735. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunillera T, Càmara E, Toro JM, Marco-Pallares J, Sebastián-Galles N, Ortiz H, Pujol J, Rodríguez-Fornells A. Time course and functional neuroanatomy of speech segmentation in adults. Neuroimage. 2009;48:541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Barroso D, Catani M, Ripolles P, Dell'Acqua F, Rodriguez-Fornells A, de Diego-Balaguer R. Word learning is mediated by the left arcuate fasciculus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13168–13173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301696110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Rao SM, Hammeke TA, Frost JA, Bandettini PA, Hyde JS. Effects of stimulus rate on signal response during functional magnetic resonance imaging of auditory cortex. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 1994;2:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0926-6410(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad M, Warren JE, Scott SK, Turkheeimer FE, Wise RJ. A common system for the comprehension and production of narrative speech. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11455–11464. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5257-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra KK, Ferrier CH. Patterns and predictors of atypical language representation in epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(4):379–385. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dronkers NF, Wilkins DP, Van Valin RD, Jr RBB, Jaeger JJ. Lesion analysis of the brain areas involved in language comprehension. Cognition. 2004;92(1–2):145–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Payer F, Onishi K, D’Eposito M, Morrison D, Sadek A, Alavi A. Language comprehension and regional cerebral defects in frontotemporal degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;50(1):157–163. doi: 10.1212/WNL.50.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp DJ, Scott SK, Wise RJ. Retrieving meaning after temporal lobe infarction: the role of the basal language area. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:936–846. doi: 10.1002/ana.20294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson H, Zahn R, Keidel JL, Binney RJ, Sage K, Lambon Ralph MA. The anterior temporal lobes support residual comprehension in Wernicke’s aphasia. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 3):931–943. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt373. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levelt WJM. Speaking: from intention to articulation. Cambridge MA: MIT Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lambon Ralph MA, McClelland J, Patterson K, Galton CJ, Hodges JR. No right to speak? The relationship between object naming and semantic impairment: neurpsychological evidence and a computational model. J Cogn Neurosci. 2001;13:341–356. doi: 10.1162/08989290151137395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vl I-D, Butler JT. Naming outcomes of anterior temporal lobectomy in epilepsy patients: a systematic review of the literature. Epilelpsy Behav. 2012;24(2):194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.04.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo EY, Han HJ, Lee EK, Choi S, Jin JH, Kim JH, Tae WS, Seo DW, Hong SC, Lee M, Hong SB. Resection extent versus postoperative outcomes of seizure and memory in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Seizure. 2005;14(8):541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojemann GA, Dodrill CB. Verbal memory deficits after left temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: mechanism and intraoperative prediction. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:101–107. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.1.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yucus CJ, Tranel D. Preserved proper naming following left anterior temporal lobectomy is associated with early age of seizure onset. Epilepsia. 2007;48(12):2241–2252. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]