Abstract

More than a decade ago, a number of methods were proposed for the inference of protein interactions, using whole-genome information from gene clusters, gene fusions and phylogenetic profiles. This structural and evolutionary view of entire genomes has provided a valuable approach for the functional characterization of proteins, especially those without sequence similarity to proteins of known function. Furthermore, this view has raised the real possibility to detect functional associations of genes and their corresponding proteins for any entire genome sequence. Yet, despite these exciting developments, there have been relatively few cases of real use of these methods outside the computational biology field, as reflected from citation analysis. These methods have the potential to be used in high-throughput experimental settings in functional genomics and proteomics to validate results with very high accuracy and good coverage. In this critical survey, we provide a comprehensive overview of 30 most prominent examples of single pairwise protein interaction cases in small-scale studies, where protein interactions have either been detected by gene fusion or yielded additional, corroborating evidence from biochemical observations. Our conclusion is that with the derivation of a validated gold-standard corpus and better data integration with big experiments, gene fusion detection can truly become a valuable tool for large-scale experimental biology.

Keywords: genome analysis, comparative genomics, gene fusion, protein interactions, proteomics, validation study

INTRODUCTION

It is just over 10 years ago and prior to the decoding of the first human genome sequence that a set of key computational methods collectively known as ‘genome context’ methods have been developed, heralding a new wave of genome bioinformatics [1]. These methods, exploiting for the first time the structural and evolutionary features of genomic sequences, were shown to be able to accurately infer functional associations of genes and their corresponding protein interactions. The three most highly acclaimed methods of this kind were phylogenetic profiling (based on co-evolutionary patterns across genomes) [2, 3], conserved gene clusters (based on proximal genomic structures) [4–6] and gene fusion detection (also known as the Rosetta Stone method—based on distal genomic elements across species) [7–9], extensively reviewed elsewhere [1].

Using gold-standard data sets compiled from the emerging large-scale functional genomics and proteomics experiments, an increasingly wider range of reference genomes and a mixture of variants and parameters [10, 11], these ‘genome-aware’ sequence analysis methods and in particular gene cluster/fusion detection, have yielded an impressive level of performance and accuracy [12].

While it is widely appreciated that gene fusion analysis has its roots in the early observations of such events in the entire genome sequences of cellular organisms ever published, including those of Haemophilus influenzae and Methanococcus jannaschii, the first report of such an explicit prediction has remained rather obscure. This case dates back to 1997, when it was observed that the distal gene pair ThiD (HI0416) and TenA (HI0358) from H. influenzae presented similarity to the ‘composite’ protein thi-4 from yeast (in this order, N- and C-termini), unlike gene MJ0236 from M. jannaschii [13]; the concluding remarks of that study pointed to the remarkable fact that this functionally associated pair (on the basis of its similarity to thi-4) was not ‘proximal’ in bacterial genomes, as observed elsewhere [4]. This unique prediction for the interaction of ThiD and TenA was a first step toward the invention of automated methods for protein interaction inference in entire genome sequences—a prediction in fact that has been subsequently confirmed by experimental analysis [14].

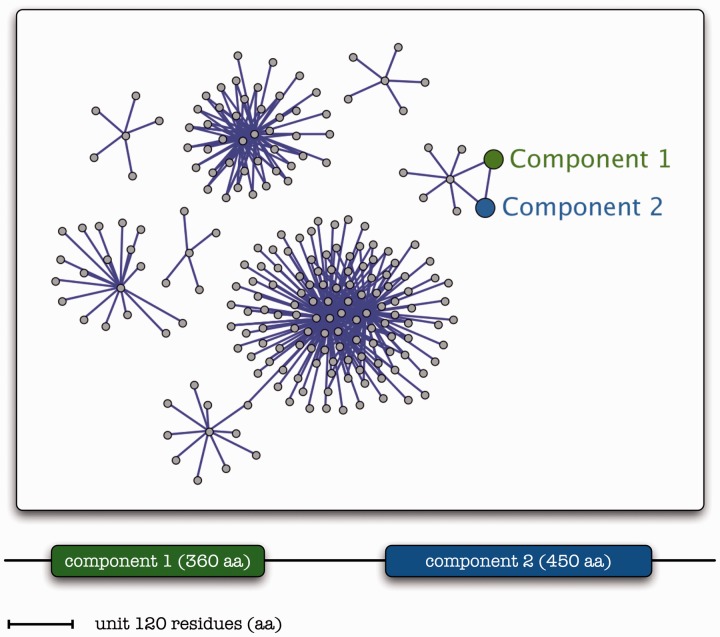

Much followed since, and a number of high-profile reports announced the arrival of new methods such as gene clusters [6], gene fusion [8] and phylogenetic profiles [3]. In particular, gene fusion analysis has provided a basis for the detection of protein interactions in whole genomes [8, 9]. Compared with the other genome-aware methods above, it was shown to be far more reliable with respect to precision (i.e. high-quality predictions with few false positives) [10], albeit with lower coverage as expected. This method is based on the observation of two separate genes in one genome found to be fused in another genome (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A pictorial representation of the gene fusion detection/association inference process. A composite protein (bottom) with two domains exhibits sequence similarities to two component homologs [Component 1 (green) and Component 2 (blue) with 360 and 450 amino acid residues (aa), respectively—not shown]. The total length of the fictitious protein sequence is 1200 residues, drawn to scale—unit shown (120 residues). Networks of associations, with nodes (grey) corresponding to genes/proteins and links (purple) depicting pairwise interactions, can thus include the corresponding (color-coded) component proteins identified by their similarity to composite proteins and inferred to be functionally linked.

The assumption is that the two separate genes in the first organism tend to be functionally linked [8]. For all the success and the extremely high citation rates of these methods (Table 1) and despite (or possibly because of) the subsequent advancement of experimental proteomics, these methods have not been used extensively in experimental settings and on a large scale. Moreover, within the vast number of publications citing the original genome-aware methods, there exists an inordinate number of computational biology citations (data not shown). It is somewhat ironic that while these methods were primarily developed to support experimental work and assist the validation of proteomics analyses, large-scale studies apparently did not find much use in these approaches (see below).

Table 1.

Citation analysis of key methods—Google Scholar, 20 May 2012

| Method | Primary reference | No. of citations |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic profiles | Ouzounis and Kyrpides (1996) [2] | 54 |

| Pellegrini et al. (1999) [3] | 1361 | |

| Gene order | Tamames et al. (1997) [4] | 151 |

| Dandekar et al. (1998) [5] | 786 | |

| Overbeek et al. (1999) [6] | 896 | |

| Gene fusion | Marcotte et al. (1999) [7] | 1320 |

| Enright et al. (1999) [8] | 906 | |

| Marcotte et al. (1999) [9] | 813 | |

| Total number of citations (approximately) | >6000 | |

All three approaches and their variants have collectively received over 6000 citations in the current literature (Table 1), signifying a new era in the analysis of genomic sequences and their real potential for the inference of protein interactions, or more generally functional associations. Yet, this astonishing number of citation records, almost half of that for the first publication of the human genome sequence, does not exactly correspond to a seamless use of these data into experimental pipelines, as indicated by a relative low number of experiments in direct use of those methods.

Indeed, a best-practice approach might be the inference of protein interactions following validation by experiment or conversely, the detection of (typically a multitude of) protein interactions subsequently corroborated by computational analysis. In either case, the interplay of a wide range of experimental techniques with the computational detection and inference of these associations can substantially increase both the efficiency and accuracy of large-scale experiments.

In this critical survey, our intention is to demonstrate this best-practice approach for individual studies of protein interactions using gene fusion and propose how the particular method—or more generally all genome-aware approaches—can be put in good use for large-scale proteomics. We review a heterogeneous, scattered body of knowledge in the literature where such benefits have been reported with the successful detection of protein interactions using a mixture of experiment and computation. We provide an assorted list of experimental findings of validated protein interactions, with the intention to reassure potential users of the merits of gene fusion analysis in this context and underline the need for integration of advanced sequence analysis with mainstream proteomics [15].

We thus argue that gene fusion detection and generally genome-aware sequence analysis, following a decade of active development, might be ripe for use in real-world experimental settings on a large scale, as reflected in todays’ big biology.

EVIDENCE FOR THE INFERENCE OF FUNCTIONAL ASSOCIATIONS VIA GENE FUSION DETECTION

Here, we provide strong evidence in support of the method in 30 case studies (Table 2) which cite the original publications [7, 8] and refer mostly to experimental rather than computational work. It is not always clearly reported whether there was a direct use of this particular method, yet it is important to review the valuable experimental evidence in support of gene fusion detection. It is encouraging to see comprehensive reviews where experimental information is summarized hand-in-hand with computational evidence, thus expanding our understanding of functional properties of certain protein classes, e.g. glutaredoxins [16] and their specificities [17]. This integration can provide a more profound characterization of entire cellular processes with the additional element of the ever increasing availability of entire genome sequences [18, 19].

Table 2.

The 30 cases of protein interaction evidence from gene fusion events

| Protein pair | Year | Ref. | Comment | Case | Composite GI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peroxidase/FAD-oxidase | 2000 | [28] | Analysis of composite, histology | 01 | 20149640 |

| MOCS1A/B | 2000 | [30] | Possible fusion, bicistronic gene | 03 | 3559907 |

| Nit/Fhit | 2000 | [48] | Sequence/structure determination | 13 | 9955180 |

| UEV1/Kua | 2000 | [72] | Differential hybrid expression | 29 | 6448867 (220675525) |

| AKINβγ/AKIN11 | 2001 | [46] | Complex biochemistry/genetics | 11 | 18390971 |

| wxcM composite | 2001 | [57] | Biochemical characterization | 18 | 14090396 |

| RAD30/CTF7 | 2001 | [66] | Indirect evidence, confirmed in [67] | 24 | 7678718 |

| Fab-G/-A/SCP2-like | 2001 | [71] | Multi-functional association | 28 | 486419 |

| MsrA/SelR | 2002 | [41] | Biochemical characterization | 08 | 3252888 |

| PA1957/1958 | 2002 | [61] | Biochemical/genetic experiments | 21 | 730107 |

| 4E-BP3/MASK | 2003 | [29] | Putative interaction | 02 | 27451489 |

| EPXH2 composite | 2003 | [33] | Functional analysis of two domains | 04 | 181395 |

| Allene oxide synthase | 2003 | [55] | EPR spectroscopy analysis | 16 | 23396450 |

| MsPpm1/2 (MtPpm1) | 2003 | [56] | Two-hybrid system in vivo interaction | 17 | 15609188 |

| MMAA (MeaB)/MCM-ICM | 2004 | [52] | Biochemical evidence for complex | 14 | 581476 |

| BCS1 (TarI/TarJ) | 2004 | [60] | Complex formation and catalysis | 20 | 471234 |

| IspD/F (+IspE) | 2004 | [68] | Structural analysis and fusion detection | 25 | 12230305 |

| burs-α/β | 2005 | [45] | Possible heterodimer activator | 10 | 62529362 |

| PitA (cld/monooxygenase) | 2006 | [35] | Putative interaction, biochemistry | 05 | 292656006 |

| SYNW2462/2463 | 2006 | [44] | Supported by expression data | 09 | 36955582 |

| CysN/CysC (NodQ) | 2006 | [62] | Interpretation of structure/function | 22 | 46313 |

| Monooxygenase/trHb | 2007 | [38] | Structural indications | 06 | 29606967 |

| Bh0493/mannitol dh | 2008 | [58] | Prediction for composite case | 19 | 348670788 |

| NirK/NirM | 2009 | [69] | Protein structure complex | 26 | 34497462 |

| RJL/DnaJ | 2009 | [73] | Evolutionary analysis | 30 | 23821015 |

| MeaB/ICM | 2010 | [54] | Indirect evidence of association | 15 | 91781568 |

| GfcC/GfcD | 2011 | [40] | Precise prediction, structure | 07 | 257140810 |

| NodGS-like FluG | 2011 | [47] | Nod/GS-like FluG, various techniques | 12 | 67537298 |

| TagF/PppA | 2011 | [64] | Confirmatory experimental evidence | 23 | 358005017 |

| Cass2 (MarA/Rob) | 2011 | [70] | Structure determination of Cass2 | 27 | 225734311 |

Protein pair, names of genes and proteins involved in gene fusion (see text)—where possible, the name of the composite protein is provided; Year, year of publication; Ref., reference; Comment, short comment for the special features of each case, for more information please see text and original reference; Case, number as in text, Composite GI, NCBI gene identification number for the composite protein sequence, either the most relevant protein or a representative of a wider case. The full composite sequence collection is available at the following publicly accessible URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/myncbi/collections/public/1RWJxAcY5x5tj-gzaTirhhG/. In total, 31 GI numbers are provided—including a double count for Case 29. Table entries are sorted by chronological order and (within each year) by order of citation in main text. Please note that not all cases are fully annotated in their corresponding sequence database records; for reasons of symmetry database cross-references e.g. from CDD [74] or PFam [75] are thus not provided, these links can be extracted from the corresponding records through the composite GI (reference).

Implicit use of gene fusion analysis in wider studies

Before the detailed description of case studies where gene fusion has been used explicitly either as a guiding principle or as confirmatory evidence, it is worth mentioning a number of analyses which use this approach indirectly. These reports range from comparative studies of entire gene families or classes and their evolutionary history, to functional studies of cellular modules. An example of a comparative study is represented by extensive structure–function analyses of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO)-like proteins [20, 21]. Examples of detailed functional studies are illustrated by the quest for putative cancer biomarker associations for proteins Ki67 [22] and Bcl-xL [23, 24], both detected in breast cancer.

Structure-based screens of interactions for specific molecular partners have been devised to accelerate protein interaction discovery, indirectly based on the premise that functional specificity of potential partners is also reflected by their phylogeny. One such example is the analysis of interactions between histidine-containing protein (HPr) and carbon catabolite protein A (CcpA) in Bacillus subtilis [25]. Other cases include the fusion of HisH/F, two histidine biosynthesis enzymes, predicted to interact through structural analysis [26] and the plant PHYLLO locus for vitamin K1 biosynthesis, present in photosynthetic cyanobacteria as a homologous gene cluster of the men (F/D/C/H) genes [27].

Explicit use of gene fusion analysis: from computation to experiment

Here, we discuss cases of potential protein interactions that have been detected through initial inference by computation which guided detailed experimentation and, where possible, validated biochemically (Table 2). We number all cases from 01 to 30 (marked in bold), in a sequential manner and across different approaches for easy reference.

Tentative interaction predictions

01 Early observations of ‘fusion’ of stand-alone domains have provided confirmatory evidence that their components allude to possible interactions, especially for longer proteins. One such example is the functional characterization of thyroid NADPH oxidases (ThoX1, ThoX2) with an N-terminal peroxidase domain and a C-terminal NADP-/FAD-oxidase domain [28].

02 Intriguingly, rare cases of mammalian genes such as the reported 4E-BP3 (eIF-binding protein)-MASK fusion transcript across different reading frames point to possible associations of the native gene products in similar regulatory pathways, although it has not been possible to confirm this prediction through literature [29].

03 Another peculiar instance of gene fusion at the transcript level has been presented for the MOCS1A/B pair, the first enzymes in the pathway of molybdopterin biosynthesis [30]. The MOCS1 locus corresponds to the highly conserved bacterial MoaA ortholog; curiously, the last steps in this pathway involve bacterial genes MoeA and MogA, which are reportedly fused in certain eukaryotic gene homologs [31]. The nature of this possible interaction has not been yet elucidated, despite detailed structural knowledge [32].

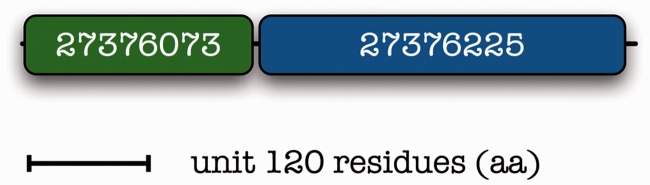

04 Inspired by such methods, detailed specificity screens have been performed for bifunctional enzymes, such as the human soluble epoxide hydrolase (EPXH2) [33]. While the domains are well delimited as a putative phosphatase (N-terminal) and epoxide hydrolase (C-terminal), their roles have not been understood in detail and were subject to functional analysis for the delineation of their function: human and mouse enzymes are bifunctional, while plant enzymes reportedly lack the phosphatase domain [33]. We note that two bacterial genes from Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110 map to the corresponding mammalian composite protein [gene identification number (GI):27376073 and GI:27376225), therefore augmenting the argument of interaction (Figure 2). These interesting discoveries are further strengthened by structure simulation and mechanistic interpretations for catalytic activities of the fused complex [34].

Figure 2.

Mapping of two component proteins from Bradyrhizobium japonicum onto the human composite protein EPXH2. GI numbers are provided. Drawn to scale as in Figure 1.

05 A more compelling case of a clear prediction with experimental support has been provided for a family of proteins from halophilic bacteria, where a ‘bifunctional’ protein containing an N-terminal chlorite dismutase domain (PF06778) and a C-terminal monooxygenase domain (PF03992) points to the possible interaction of these two enzyme families, supported by protein purification, limited proteolysis and mass spectrometry [35]. Implications for salt tolerance of this interaction remain an open issue: it is worth pointing out that similar chlorite dismutase enzymes have been found in other chemolithotrophic bacteria, indicating an ancient origin [36]; the original discovery in halobacteria has spurred an active area of fascinating research [37].

06 In parallel work, the monooxygenase domain (PF03992) has been found to be associated with a heme-containing protein, known as bacterial globin or trHb, on the basis of two fusion ‘composite’ proteins [38]. While interaction data were not available yet, this association is further supported by structural evidence from the pair IsdG/I in dimeric formations [39]. We note that IsdG and IsdI are separate genes in Staphylococcus aureus, yet present in consecutive order in the chlorophyta Ostreococcus tauri/lucimarinus (GI:308806403/GI:145348684) and elsewhere (data not shown).

07 Recently, the 3D structure of protein GfcC, essential for assembly of group 4 polysaccharide capsule, has been reported in conjunction with a putative interaction potential with GfcD [40]. This interaction is proposed based on the observation that the pair GfcC/D exhibits similarity to the ‘composite’ protein OtnG from Burkholderia species [40]. This prediction might be confirmed in the future when the high-resolution structure of GfcD is obtained.

In all the above cases, there is credible evidence that the domains in question are functionally associated and potentially physically interacting. However, there is no direct experimental observation confirming these precise predictions, as yet.

Prediction-driven experiments

08 One of the early discoveries that confirmed the prediction power of this method is the observation that the proteins peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase MsrA and Selenoprotein R (SelR) exhibit both a similar phylogenetic distribution across multiple organisms and patterns of gene clusters or fusions (see Table 1 in [41]). This observation has led to the characterization of SelR as a methionine sulfoxide reductase [41]. Interestingly, the MsrA/B gene fusion components were not detected as an interacting pair in specific systems [42], while later the protein structure of a MsrA/B fusion (composite) protein provides detailed explanations for the earlier negative biochemical findings [43].

09 Full-scale studies with explicit use of gene fusion detection and pathway inference have also appeared, for example the computational derivation of a network for nitrogen assimilation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus (WH8102), using data derived from comparative analysis that is confirmed by relevant expression studies [44]. A stunning example is the pair SYNW2462/3 which corresponds to a composite protein in other strains and is down-regulated by ammonium in the expression experiments [44], thus implicating this pair in a direct association.

10 An interesting computation-driven experimental analysis has been reported for the bursicon gene, a key factor for insect development [45]. The presence of two genes in Drosophila, found as a putative fusion gene in some other insect species, drove a series of elegant experiments that demonstrated how the two highly similar, paralogous genes form a heterodimer which is involved in the activation of the receptor DLGR2 [45].

11 Another case of a bifunctional adaptor-regulator protein AKINβγ with a composite structure has been identified in plants, composed of an N-terminal AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) β- (KIS domain) and a C-terminal AMPK γ-subunit (SNF4), itself interacting with SNF1-related protein kinases (SnRKs) [46].

12 A strikingly thorough study, employing a range of techniques, resulted in the identification of protein interaction between the plant N-terminal nodulin/amidohydrolase (Nod) and the C-terminal glutamine synthase I (GS) domains, as inferred from the fungal composite NodGS-like FluG protein [47].

13 The centerpiece methodology of the gene fusion (Rosetta Stone) hypothesis has been adopted for the structural delineation of the Nit–Fhit interactions, known to share a common evolutionary distribution as well as expression profiles [48]. On the basis of the above observations, an extensive sequencing effort has been made to discover more Nit (nitrilase) homologs from species with Fhit (nucleotide-binding) genes [48], to amplify the initial hypothesis of their association. The structure determination of the composite Nit–Fhit from Caenorhabditis elegans (also widely present elsewhere) provides insights into the interaction of the two monomers as well as additional evidence that this hypothesis holds [48], extending beyond this instance [49–51].

14 Yet another phylogenetically inspired experimental analysis involves the McmC gene present in a number of bacterial genomes as an alleged fusion of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MCM) and MeaB (GTP-binding protein) [52]. This peculiar organization of two genes where the N-terminus of McmC matches the C-terminus of MCM (and vice versa, with the former region corresponding to a putative coenzyme B12-binding site) while the central region of McmC is similar to MeaB, still points to a complex fusion event, implying an interaction of the two component proteins, namely MCM and MeaB [52]. Biochemical assays confirm the expected activities of the two component proteins (including GTPase activity for MeaB), while complex formation has also been established [52]. The structure of both human homologs has been determined further providing support for this particular interaction [53].

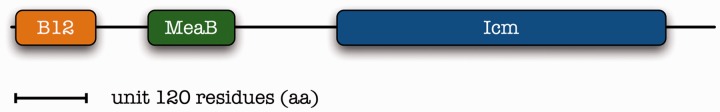

15 Furthermore, in parallel work this particular composite case has been identified as a fusion of isobutyryl-CoA mutase (ICM) and named appropriately as IcmF [54], in Nocardia farcinica for instance (GI:54023003) (Figure 3, suggested domain structure). This is one of the most challenging examples of substrate and cofactor specificity that has not yet been fully elucidated.

Figure 3.

Mapping of the complex domain structure for IcmF in the actinobacterium N. farcinica IFM 10152, GI:54023003, length 1071 residues (aa); orange: cofactor-binding site; green: MCM; blue: ICM—see text for details. Drawn to scale as in Figure 1.

16 Mechanistic studies of substrate coupling between lipoxygenase (C-terminal) and catalase (N-terminal) have been inspired by the presence of this domain fusion in coral and other organisms. Coral allene oxide synthase (cAOS, catalase superfamily) and 8R-lipoxygenase in Plexaura homomalla fuse into a composite protein and were subject to a combination of spectroscopic and mutagenesis studies, confirming the genuine functional role of this association [55].

17 Using a two-hybrid system, it has been shown that the protein pair MsPpm1/2 in Mycobacterium smegmatis encoded as a single operon corresponds to an interaction pair as reflected by the composite structure of protein MtPpm1 in M. tuberculosis [56]—indeed in multiple strains (data not shown). MtPpm1 encodes a poly-prenol-P-Man synthase for the biosynthesis of the cell wall glycolipid lipoarabinomannan, whose N-terminal domain corresponds to a putative membrane anchoring protein and C-terminal catalytic domain to the dolichol-P-Man synthase; the MsPpm1/2 component orthologs have been shown to interact and complement this function through heterodimerization, with MsPpm1 having a synthase activity and MsPpm2 transmembrane segments that stabilize and augment the enzymatic function [56].

18 Finally, a significant example of mixed computation and experiment for pathway inference and experimental validation with molecular genetics is the analysis of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Xanthomonas campestris [57]. In this report, it is found that gene wxcM codes for a bifunctional enzyme, with its N-terminus acting as an acetyltransferase and the C-terminus acting as a putative isomerase. These observations coupled with detailed experimentation led to the proposal that wxcM catalyzes two alternating steps in the biosynthesis of precursor molecules for this pathway [57].

Independent confirmations, twilight zone similarities

19 Remote homologs are difficult to detect in fusion mode, as stated for the case of amidohydrolase superfamily members [58]. In this case, yet again, certain homologs of the gene product under consideration namely Bh0493 characterized as uronate isomerase, exhibit strong similarity to ‘composite’ proteins, e.g. the Phytophthora sojae gene 347522 (GI:348670788), which contain a C-terminal amidohydrolase domain and a N-terminal mannitol dehydrogenase.

20 Carrying this argument to the limit, there is also a possibility that the one of the two ‘component’ proteins might be analogous and not homologous and yet confer similar functional properties. The bifunctional composite protein Bcs1 from H. influenzae contains two domains, a IspD-/GlmU-like cytidyltransferase N-terminal domain and a FabG-like reductase C-terminal domain [59], in an arrangement reminiscent of the genes TarI and TarJ in S. aureus. While TarI shares similarity with the H. influenzae protein, TarJ does not; instead, it has been hypothesized that it carries out a similar reaction, later validated by detailed biochemical experiments, also confirming the direct physical interaction of the two subunits TarI/J as a complex in S. aureus [60].

21 Another case of a missing biochemical function involving weak sequence similarities, that of ribosylnicotinamide kinase, has been identified using a mixture of comparative analysis including gene fusion [61]. In Escherichia coli (K-12 MG1655), the fused ‘composite’ protein contains both required enzyme/transport functions, while in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 is represented by two neighboring genes, namely, PA1957 (kinase)/PA1958 (transporter, pnuC homolog). In H. influenzae Rd, the transporter domain is encoded by the pnuC gene, thus representing the function of the composite or neighboring genes from E. coli and P. aeruginosa, respectively [61]. Analysis with biochemical and genetic experiments provides strong evidence for the role of these proteins in the corresponding biochemical pathway [61].

Explicit use of gene fusion analysis: from experiment to computation

Here, we discuss cases of experimentally delineated potential protein interactions which are further corroborated by a follow-up comparative analysis of the corresponding genes via the detection of relevant gene fusions.

Interpretation in structure/function studies

22 The structural analysis of Pseudomonas syringae ATP sulfurylase subunit CysN provides a credible explanation for the association of this domain with adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate kinase (CysC) into NodQ in several bacterial species (e.g. Rhizobium meliloti) [62], strongly suggestive of substrate channeling. The CysN/C case has also been explored within an evolutionary context, as a case of a possible horizontal gene transfer (HGT) event followed by gene fusion. It has been proposed that multiple fusion events have occurred independently, where an archaeal or eukaryotic CysN-like gene most similar to elongation factor-1α gene (EF-1α) was horizontally transferred into a bacterial species, from which secondary HGT events were spawned [63].

23 In P. aeruginosa, protein TagF participates in the transcriptional control of a type VI secretion system while at the same time synteny analysis revealed its potential association with PppA, a PP2C phosphatase [64]. In certain species, such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens, the two genes are fused into a composite, further corroborating this association, a finding, however, not supported by the particular report [64]. Indeed, the apparent absence of other associated proteins such as Fha1 in Burkholderia thailandensis might be due to undetectable similarities and absence of syntenic involvement in published genome sequences (data not shown). The complex recruitment sequence for the regulation of type VI secretion is another exemplary system where gene fusion might be responsible for the co-expression of critical genes in certain species. Involvement of the PP2C domain in complex configurations has been reported elsewhere [65].

24 Examining the involvement of genes CTF18 and CTF4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through a series of rigorous experiments [66], a detailed network of physical and genetic interactions has been established. One of these genes, Eso1, can be found in Schizosaccharomyces pombe as a fusion of two domains, namely, polymerase η (RAD30, cd01702) and Ctf7 (pfam13880), suggesting a possible indirect interaction [66], later confirmed by large-scale co-localization experiments [67]. This particular example is an excellent case of best practice from small-scale high-quality studies coupled with large-scale high-throughput studies, the main theme propounded in this critical survey.

25 An impressive example of detailed biochemical work involving enzymes from the core isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis pathway, namely, IspD/E/F from Campylobacter jejuni clearly demonstrates the presence of a composite protein IspD/F, corresponding to two enzymes catalyzing non-consecutive steps in this process, known to exist as components in other organisms including E. coli [68]. The enzyme IspE, catalyzing the intermediate step, is shown to mediate this interaction in E. coli [68], thus providing further support for the hypothesis that gene fusion might provide a selective advantage for substrate channeling in some species.

26 The structure determination of copper-containing nitrite reductase (CuNIR, NirK) with its cognate cytochrome c (NirM) strongly suggests that this particular arrangement, supported by comparative genomics evidence for the co-location of these genes in certain organisms, is indeed a functional complex [69]. The cytochrome c moiety has thus been proposed to participate as the electron donor for the function of CuNIR pointing to intra-protein heme-to-copper electron transfer, with component genes NirK and NirM found as fused genes (NirK/M composite) elsewhere [69].

27 Finally, examples of gene fusion involving extrachromosomal elements as indicated by the structure determination and sequence analysis of the Cass2 integron gene cassette-associated protein from an environmental Vibrio cholerae strain (OP4G) correspond to regions of DNA-binding (helix-turn-helix) motifs [70]. These motifs are characteristic of MarA and Rob homologs suggesting possible complex interactions of the corresponding monomers elsewhere [70] as well as the critical significance of gene fusion events in generating protein sequence diversity and substrate specificity outside the recipient genomes.

Omics-supported studies for indirect protein associations

28 In the case of human 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 4 (17β-HSD type 4), containing three consecutive domains with direct involvement in the corresponding catalytic functions—namely, hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (cd05353, FabG-like), enoyl-CoA hydratase (FabA-like) and SCP-2 sterol transfer domain (cl01225), there exist highly conserved multi-functional homologs in various taxa, including yeasts (where they are known as FOX2) [71]. The strong conservation and the presumed multiple events of fusion and fission, also involving the occasional loss (e.g. SCP-2, GI:328711512) or duplication (e.g. FabG-like, GI:5869811) of single domains, further suggest a strong association of these individual functional elements in the pathway [71].

29 In C. elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, Kua and UEV (a variant E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme) are expressed independently and are found at different loci. The human homologs UEV1 and Kua are adjacent to each other and expressed either as separate transcripts or as a hybrid transcript, encoding a fused composite protein [72]. Experimental analysis of cellular localization indicates that the two variants (i.e. non-hybrid and hybrid) reach different destinations within the cell [72].

30 Patchy phylogenetic distribution of genes does not always imply HGT, as shown in the case of the Ras-like GTPase RJL family of unknown function, where gene loss has been implicated in a number of occasions involving taxa without flagellated cells, thus suggesting a role with the flagellar apparatus. In two cases, RJL members were fused with an N- or C-terminal DnaJ (Hsp70) domain, the Alveolata and Holozoa, respectively [73].

DISCUSSION AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

This comprehensive survey of individual cases of protein interaction discovery through computation-driven experiment or experimentally derived computational inference strongly suggests that gene fusion detection can be a valuable tool for modern, high-throughput proteomics [1]. The corroborating evidence derived from this limited, high-quality data set unambiguously demonstrates that in most, if not all, cases, gene fusions can direct toward potential protein interactions with high accuracy and reasonably good coverage. One prerequisite is the availability of an entire genome sequence for the species under consideration, a condition that is increasingly more relaxed with more genome sequences becoming available. Another prerequisite is evidently correct gene prediction, so that the domain structure of encoded proteins is accurately reflected in the sequence, a condition that is not always easy to satisfy by next-generation sequencing technology with sequences obtained by short-read sequence assemblies.

As mentioned earlier, it is somewhat ironic that while the genome-aware methods were developed as a way to augment experimental work in proteomics, most such large-scale studies in the literature do not report (or cite) the use of any of those methods as a validation mechanism for high-throughput experiments. Indeed, the majority of citations for these methods (Table 1) arise from similar computational work, technical extensions, general reviews and sensational commentary, written in the past. We hope that we now provide the argument for more extensive use of gene fusion analysis for proteomics.

One could envision a setting where this gold-standard corpus expands to a significant degree and can be used primarily to assess the coverage of protein interaction detection by experiments. One example, with the limited information available today follows. Of the 30 cases (Table 2), there are five readily detectable cases of orthologous gene pairs in the genome of S. cerevisiae S288c (Table 3). We chose this organism for two reasons, first for its extensively studied interactome and second for its consistent and easy-to-use gene name catalog. Searching for these pairs in the source database listed [76], it can be found that four out of the five cases can be detected as interaction partners, indicating a high coverage, in this instance 80%—of course this estimate is by way of example, as a deeper analysis and statistical treatment will be necessary in real-world settings.

Table 3.

Examples of component pairs detected by gene fusion in the S. cerevisiae interactome

| Case | Component 1 | Component 2 | Found? | Composite GI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08 | YER042W | YCL033C | Yes | 3252888 |

| 11 | YER027C | YGL115W | Yes | 18390971 |

| 13 | YJL126W | YDR305C | Yes | 9955180 |

| 21 | YBR118W | YKL001C | Yes | 46313 |

| 23 | YDR419W | YFR027W | No | 7678718 |

Source: http://www.yeastnet.org/data/yeastnet2.orf.txt [76].

Thus, it must be appreciated that with the availability of an ever increasing number of genomes acting as reference, i.e. providing composite background protein sequences, this approach can become a benchmark for protein interaction research. We have extensively reviewed the available experimental evidence in the literature and have found that, while protein interaction data processing has been maturing over the past few years [77], the inference of protein interactions has not been integrated to a sufficient degree, at least as this is reflected by citation analysis. The development of multiple methods that compile experimentally derived protein interactions from curated databases, process the interaction graphs, cluster related modules, discover novel associations and visualize them [77, 78] appears to have out-shined valuable genome-aware inference methods.

It is encouraging to see parallel studies that examine the micro-evolutionary mechanisms of these events in one genus e.g. Drosophila [79] and the further investigation of concurrent gene (i.e. domain) loss events, for example the repertoire of Myb domains lost in fungal zuotins from MIDA1-like factors [80]. Given the wider availability of genomic and metagenomic information, we predict that gene fusion detection and subsequent inference of functional associations will become more common and applicable to large-scale studies of protein interaction. The best-practice examples that are provided herein point the way for the critical importance of integration of inference and validation methods for protein interaction detection and how trailblazing small-scale studies pave the way for large-scale proteomics.

The sheer power of evolutionary thinking behind protein interaction analysis [81, 82] can thus reveal the conservation and diversification of interacting modules, enriched by functional genomics data for example gene expression or cellular localization and further our understanding of the complex pathways that govern cell biology.

Key Points.

Gene fusion analysis is one of the most successful computational methods for the detection of genome-wide protein interactions.

Compared with other methods that take into account genome structure and evolution, gene fusion has a relatively low coverage of known interactions but high precision.

Despite high citation rates, these methods do not appear to have been used extensively in high-throughput proteomics.

Many examples from individual case studies listed here have demonstrated that this method is applicable as a validation approach for proteomics.

Evolutionary thinking in support of protein interaction analysis can reveal the conservation and diversification of interacting modules in cellular pathways.

Acknowledgements

C.A.O. thanks the Deparment of Biological Sciences at the University of Cyprus for their kind hospitality during the spring semester of 2012 and also Prof. Ben Blencowe (University of Toronto) and Dr Peter Karp (SRI International) for critical reading of the article.

FUNDING

Parts of this work have been supported by the FP7 Collaborative Project MICROME (grant agreement # 222886-2 to C.A.O.), funded by the European Commission.

Biographies

Vasilis J. Promponas is a lecturer in Bioinformatics and the head of the Bioinformatics Research Laboratory at the University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus.

Christos A. Ouzounis is a principal investigator at the Centre for Research & Technology Hellas (CERTH), Thessaloniki, Greece and a visiting professor at the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, University of Toronto, Canada.

Ioannis Iliopoulos is a lecturer in Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics at the University of Crete Medical School, Heraklion, Greece.

References

- 1.Eisenberg D, Marcotte EM, Xenarios I, et al. Protein function in the post-genomic era. Nature. 2000;405:823–6. doi: 10.1038/35015694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ouzounis C, Kyrpides N. The emergence of major cellular processes in evolution. FEBS Lett. 1996;390:119–23. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00631-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellegrini M, Marcotte EM, Thompson MJ, et al. Assigning protein functions by comparative genome analysis: protein phylogenetic profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4285–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamames J, Casari G, Ouzounis C, et al. Conserved clusters of functionally related genes in two bacterial genomes. J Mol Evol. 1997;44:66–73. doi: 10.1007/pl00006122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dandekar T, Snel B, Huynen M, et al. Conservation of gene order: a fingerprint of proteins that physically interact. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:324–8. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Overbeek R, Fonstein M, D’Souza M, et al. The use of gene clusters to infer functional coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2896–901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcotte EM, Pellegrini M, Ng HL, et al. Detecting protein function and protein-protein interactions from genome sequences. Science. 1999;285:751–3. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enright AJ, Iliopoulos I, Kyrpides NC, et al. Protein interaction maps for complete genomes based on gene fusion events. Nature. 1999;402:86–90. doi: 10.1038/47056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcotte EM, Pellegrini M, Thompson MJ, et al. A combined algorithm for genome-wide prediction of protein function. Nature. 1999;402:83–6. doi: 10.1038/47048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karimpour-Fard A, Leach SM, Gill RT, et al. Predicting protein linkages in bacteria: which method is best depends on task. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:397. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green ML, Karp PD. Using genome-context data to identify specific types of functional associations in pathway/genome databases. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:i205–i211. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrer L, Dale JM, Karp PD. A systematic study of genome context methods: calibration, normalization and combination. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:493. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouzounis CA, Kyrpides NC. ThiD-TenA: a gene pair fusion in eukaryotes. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:708–11. doi: 10.1007/pl00013145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morett E, Korbel JO, Rajan E, et al. Systematic discovery of analogous enzymes in thiamin biosynthesis. Nature Biotechnol. 2003;21:790–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pyndiah S, Lasserre JP, Menard A, et al. Two-dimensional blue native/SDS gel electrophoresis of multiprotein complexes from Helicobacter pylori. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:193–206. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600363-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouhier N, Couturier J, Johnson MK, et al. Glutaredoxins: roles in iron homeostasis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;35:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rouhier N, Gelhaye E, Sautiere PE, et al. Isolation and characterization of a new peroxiredoxin from poplar sieve tubes that uses either glutaredoxin or thioredoxin as a proton donor. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1299–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsoka S, Ouzounis CA. Recent developments and future directions in computational genomics. FEBS Lett. 2000;480:42–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy ASN, Ben-Hur A, Day IS. Experimental and computational approaches for the study of calmodulin interactions. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:1007–19. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li HY, Sawaya MR, Tabita FR, et al. Crystal structure of a RuBisCO-like protein from the green sulfur bacterium Chibrobium tepidum. Structure. 2005;13:779–89. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabita FR, Hanson TE, Li HY, et al. Function, structure, and evolution of the RubisCO-like proteins and their RubisCO homologs. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:576–9. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00015-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan PH, Bay BH, Yip G, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of Ki67 in breast cancer correlates with transcriptional regulation of genes related to apoptosis and cell death. Modern Pathol. 2005;18:374–81. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espana L, Martin B, Aragues R, et al. Bcl-x(L)-mediated changes in metabolic pathways of breast cancer cells - from survival in the blood stream to organ-specific metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1125–37. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendez O, Martin B, Sanz R, et al. Underexpression of transcriptional regulators is common in metastatic breast cancer cells overexpressing Bcl-X-L. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1169–79. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller W, Horstmann N, Hillen W, et al. The transcription regulator RbsR represents a novel interaction partner of the phosphoprotein HPr-Ser46-P in Bacillus subtilis. FEBS J. 2006;273:1251–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Donoghue P, Amaro RE, Luthey-Schulten Z. On the structure of hisH: protein structure prediction in the context of structural and functional genomics. J Struct Biol. 2001;134:257–68. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross J, Cho WK, Lezhneva L, et al. A plant locus essential for phylloquinone (vitamin K1) biosynthesis originated from a fusion of four eubacterial genes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17189–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Deken X, Wang DT, Many MC, et al. Cloning of two human thyroid cDNAs encoding new members of the NADPH oxidase family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23227–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poulin F, Brueschke A, Sonenberg N. Gene fusion and overlapping reading frames in the mammalian genes for 4E-BP3 and MASK. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52290–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray TA, Nicholls RD. Diverse splicing mechanisms fuse the evolutionarily conserved bicistronic MOCS1A and MOCS1B open reading frames. RNA. 2000;6:928–36. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schrag JD, Huang W, Sivaraman J, et al. The crystal structure of Escherichia coli MoeA, a protein from the molybdopterin synthesis pathway. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:419–31. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanaujia SP, Jeyakanthan J, Shinkai A, et al. Crystal structures, dynamics and functional implications of molybdenum-cofactor biosynthesis protein MogA from two thermophilic organisms. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2011;67:2–16. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110035037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman JW, Morisseau C, Harris TR, et al. The soluble epoxide hydrolase encoded by EPXH2 is a bifunctional enzyme with novel lipid phosphate phosphatase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1558–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437724100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Vivo M, Ensing B, Dal Peraro M, et al. Proton shuttles and phosphatase activity in soluble epoxide hydrolase. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:387–94. doi: 10.1021/ja066150c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bab-Dinitz E, Shmuely H, Maupin-Furlow J, et al. Haloferax volcanii PitA: an example of functional interaction between the Pfam chlorite dismutase and antibiotic biosynthesis monooxygenase families? Bioinformatics. 2006;22:671–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btk043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maixner F, Wagner M, Lucker S, et al. Environmental genomics reveals a functional chlorite dismutase in the nitrite-oxidizing bacterium ‘Candidatus Nitrospira defluvii’. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:3043–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goblirsch B, Kurker RC, Streit BR, et al. Chlorite dismutases, DyPs, and EfeB: 3 microbial heme enzyme families comprise the CDE structural superfamily. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:379–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonamore A, Attill A, Arenghi F, et al. A novel chimera: the “truncated hemoglobin-antibiotic monooxygenase” from Streptomyces avermitilis. Gene. 2007;398:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu R, Skaar EP, Zhang R, et al. Staphylococcus aureus IsdG and IsdI, heme-degrading enzymes with structural similarity to monooxygenases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2840–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409526200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sathiyamoorthy K, Mills E, Franzmann TM, et al. The crystal structure of Escherichia coli group 4 capsule protein GfcC reveals a domain organization resembling that of Wza. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5465–76. doi: 10.1021/bi101869h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kryukov GV, Kumar RA, Koc A, et al. Selenoprotein R is a zinc-containing stereo-specific methionine sulfoxide reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4245–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072603099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grimaud R, Ezraty B, Mitchell JK, et al. Repair of oxidized proteins - identification of a new methionine sulfoxide reductase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48915–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim YK, Shin YJ, Lee WH, et al. Structural and kinetic analysis of an MsrA-MsrB fusion protein from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:699–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su ZC, Mao FL, Dam P, et al. Computational inference and experimental validation of the nitrogen assimilation regulatory network in cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp WH 8102. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1050–65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendive FM, Van Loy T, Claeysen S, et al. Drosophila molting neurohormone bursicon is a heterodimer and the natural agonist of the orphan receptor DLGR2. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lumbreras V, Alba MM, Kleinow T, et al. Domain fusion between SNF1-related kinase subunits during plant evolution. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:55–60. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doskocilova A, Plihal O, Volc J, et al. A nodulin/glutamine synthetase-like fusion protein is implicated in the regulation of root morphogenesis and in signalling triggered by flagellin. Planta. 2011;234:459–76. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pace HC, Hodawadekar SC, Draganescu A, et al. Crystal structure of the worm NitFhit Rosetta Stone protein reveals a Nit tetramer binding two Fhit dimers. Curr Biol. 2000;10:907–17. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brenner C. Catalysis in the nitrilase superfamily. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:775–82. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00387-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brenner C. Hint, Fhit, and GalT: function, structure, evolution, and mechanism of three branches of the histidine triad superfamily of nucleotide hydrolases and transferases. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9003–14. doi: 10.1021/bi025942q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Semba S, Han SY, Qin HR, et al. Biological functions of mammalian NIT1, the counterpart of the invertebrate NitFhit Rosetta Stone protein, a possible tumor suppressor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28244–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Korotkova N, Lidstrom ME. MeaB is a component of the methylmalonyl-CoA mutase complex required for protection of the enzyme from inactivation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13652–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Froese DS, Kochan G, Muniz JR, et al. Structures of the human GTPase MMAA and vitamin B12-dependent methylmalonyl-CoA mutase and insight into their complex formation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38204–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cracan V, Padovani D, Banerjee R. IcmF is a fusion between the radical B(12) enzyme isobutyryl-CoA mutase and its G-protein chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:655–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.062182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu FY, Katsir LJ, Seavy M, et al. Role of radical formation at tyrosine 193 in the allene oxide synthase domain of a lipoxygenase-AOS fusion protein from coral. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6871–80. doi: 10.1021/bi027427y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baulard AR, Gurcha SS, Engohang-Ndong J, et al. In vivo interaction between the polyprenol phosphate mannose synthase Ppm1 and the integral membrane protein Ppm2 from Mycobacterium smegmatis revealed by a bacterial two-hybrid system. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2242–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vorholter FJ, Niehaus K, Puhler A. Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris: a cluster of 15 genes is involved in the biosynthesis of the LPS O-antigen and the LPS core. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;266:79–95. doi: 10.1007/s004380100521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen TT, Brown S, Fedorov AA, et al. At the periphery of the amidohydrolase superfamily: Bh0493 from Bacillus halodurans catalyzes the isomerization of D-galacturonate to D-tagaturonate. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1194–206. doi: 10.1021/bi7017738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zolli M, Kobric DJ, Brown ED. Reduction precedes cytidylyl transfer without substrate channeling in distinct active sites of the bifunctional CDP-ribitol synthase from. Haemophilus influenzae. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5041–8. doi: 10.1021/bi002745n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pereira MP, Brown ED. Bifunctional catalysis by CDP-ribitol synthase: convergent recruitment of reductase and cytidylyltransferase activities in Haemophilus influenzae and Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11802–12. doi: 10.1021/bi048866v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kurnasov OV, Polanuyer BM, Ananta S, et al. Ribosylnicotinamide kinase domain of NadR protein: identification and implications in NAD biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6906–17. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.6906-6917.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mougous JD, Lee DH, Hubbard SC, et al. Molecular basis for G protein control of the prokaryotic ATP sulfurylase. Mol Cell. 2006;21:109–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Inagaki Y, Doolittle WF, Baldauf SL, et al. Lateral transfer of an EF-1 alpha gene: origin and evolution of the large subunit of ATP sulfurylase in eubacteria. Curr Biol. 2002;12:772–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00816-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silverman JM, Austin LS, Hsu F, et al. Separate inputs modulate phosphorylation-dependent and -independent type VI secretion activation. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82:1277–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greenstein AE, Hammel M, Cavazos A, et al. Interdomain communication in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis environmental phosphatase Rv1364c. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29828–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hanna JS, Kroll ES, Lundblad V, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae CTF18 and CTF4 are required for sister chromatid cohesion. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3144–58. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.9.3144-3158.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huh WK, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, et al. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–91. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gabrielsen M, Bond CS, Hallyburton I, et al. Hexameric assembly of the bifunctional methylerythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase and protein-protein associations in the deoxy-xylulose-dependent pathway of isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52753–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nojiri M, Koteishi H, Nakagami T, et al. Structural basis of inter-protein electron transfer for nitrite reduction in denitrification. Nature. 2009;462:117–20. doi: 10.1038/nature08507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deshpande CN, Harrop SJ, Boucher Y, et al. Crystal structure of an integron gene cassette-associated protein from Vibrio cholerae identifies a cationic drug-binding module. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e16934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Breitling R, Marijanovic Z, Perovic D, et al. Evolution of 17 beta-HSD type 4, a multifunctional protein of beta-oxidation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;171:205–10. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomson TM, Lozano JJ, Loukili N, et al. Fusion of the human gene for the polyubiquitination coeffector UEV1 with Kua, a newly identified gene. Genome Res. 2000;10:1743–56. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1405r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Elias M, Archibald JM. The RJL family of small GTPases is an ancient eukaryotic invention probably functionally associated with the flagellar apparatus. Gene. 2009;442:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D225–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D290–301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee I, Li Z, Marcotte EM. An improved, bias-reduced probabilistic functional gene network of baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cusick ME, Yu H, Smolyar A, et al. Literature-curated protein interaction datasets. Nat Methods. 2009;6:39–46. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Missiuro PV, Liu K, Zou L, et al. Information flow analysis of interactome networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu YC, Rasmussen MD, Kellis M. Evolution at the subgene level: domain rearrangements in the Drosophila phylogeny. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:689–705. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Braun EL, Grotewold E. Fungal Zuotin proteins evolved from MIDA1-like factors by lineage-specific loss of MYB domains. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:1401–12. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Navlakha S, Kingsford C. Network archaeology: uncovering ancient networks from present-day interactions. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1001119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peregrin-Alvarez JM, Ouzounis CA. The comparative genomics of protein interactions. Genome Inform. 2007;19:131–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]