Abstract

Background

The literature suggests that depression is an important comorbidity in asthma that can significantly influence disease management and quality of life (QOL).

Objective

To study the effect of coexisting depressive symptoms on the effectiveness of self-management interventions in urban teens with asthma.

Methods

We analyzed data from a randomized controlled trial of Puff City, a web-based, tailored asthma management intervention for urban teens, to determine whether depression modulated intervention effectiveness for asthma control and QOL outcomes. Teens and caregivers were classified as depressed based on responses collected from baseline questionnaires.

Result

Using logistic regression analysis, we found that a lower percentage of treatment students had indicators of uncontrolled asthma compared with controls (adjusted odds ratios <1). However, for teens depressed at baseline, QOL scores at follow-up were significantly higher in the treatment group compared with the control group for the emotions domain (adjusted relative risk, 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.2–3.63; P = .01; interpreted as emotional QOL for treatment students increased by a factor of 2.08 above controls). Estimates for overall QOL and symptoms QOL were borderline significant (adjusted relative risk, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 0.93–2.63; P = .09; and adjusted relative risk, 1.72; 95% confidence interval, 0.94–3.15; P = .08; respectively). Among teens not depressed at baseline, no significant differences were observed between treatment and control groups in QOL domains at follow-up.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that depression modified the relationship between the effectiveness of an asthma intervention and emotional QOL in urban teens. Further assessment of self-management behavioral interventions for asthma should explore the mechanism by which depression may alter the intervention effect.

Introduction

The prevalence of asthma has been steadily increasing across all age groups,1 and it is disproportionately higher among women and children, African Americans, and those reporting an income below the federal poverty level in United States.2,3 Asthma significantly affect the quality of life (QOL) in the most vulnerable sections of society and has important implications for increased health care costs and loss of productivity.4 Medical management of asthma is targeted at symptomatic improvement and only has an indirect effect on the QOL. An ideal intervention strategy would improve not only symptoms related to asthma but also the QOL in young children and teens with asthma.5 The Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3) asthma management guidelines from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recognized the importance of improving QOL and added it as one of the tools used in assessing impairment as part of classifying asthma severity.6 Several clinical trials have also focused on QOL as an outcome measure of therapies.7–9 Improvement in asthma-related QOL should therefore be one of the goals of any intervention program or treatment strategy.10

Urban teens represent a challenging group for asthma management because of the potential effect of other external influences (social and/or peer-related factors) and comorbidities (eg, depression) that can affect adherence to therapy and overall disease control. Several nonpharmacologic interventions have been advocated for adolescents with asthma to overcome these issues, and self-management education programs have targeted improvement in indicators of asthma control and QOL. Despite many self-management programs that have been developed for both adults11–20 and children21–27 in the past 3 decades, results have been mixed in terms of success.28,29 At the same time, it is also important to recognize the effect of other comorbidities and how they could affect the effectiveness of these interventions.

Depression is an important comorbidity among urban teens with asthma30,31 and is prevalent in teens with asthma and their caregivers.32,33 We wanted to understand how depression could influence the effect of a self-management educational intervention on asthma-related QOL and outcomes. Results could inform the design of better self-management interventions that would include an assessment of depression at baseline.

The Puff City asthma program (clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT00201058) was developed for urban African American teens with asthma and represents a web-based, computer-tailored approach to providing education related to asthma self-regulation and management, while targeting negative behaviors that could affect asthma-related outcomes.34 The content of Puff City is based on information from the EPR-2 and EPR-3 reports.35–37 Puff City focuses on modifying 3 core behaviors: adherence to controller medication, availability of rescue inhaler, and smoking reduction or cessation. The Puff City program presents theory-based health messages and information on asthma control in reference to the core behaviors and information about a variety of other pertinent topics.38–42 The objective of this analysis is to explore the effect of teen depression on the effectiveness of the Puff City asthma self-management program.

Methods

This analysis uses data from a school-based randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in 2007–2011 to evaluate Puff City. This study was approved by Detroit Public Schools Office of Research, Evaluation and Assessment and the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions (protocol 4579). The methods used to identify students eligible for the RCT are described elsewhere.34,43,44 Briefly, caregivers of 9th to 12th graders of 6 public high schools were informed by mail of a Lung Health Survey on respiratory symptoms to be administered during English class. Caregivers could opt out of having their student complete the questionnaire by signing and returning the letter to the school. Students who met criteria for current asthma (ie, report of asthma symptoms with or without report of a physician diagnosis of asthma) were eligible for the RCT,34 and informational packets with consent and assent forms were mailed to their homes by a district-affiliated contractor to maintain student confidentiality.44

The Puff City program is based on concepts from the transtheoretical model, the health belief model, attribution theory, motivational interviewing, and other behavior change models.36,38,39,45 Puff City also features topics on trigger avoidance, device use (eg, how to use a metered-dose inhaler, Diskus, Turbuhaler, and spacer), and basic asthma physiology. Problem-solving scenarios are also included.

Using computers at school, enrolled students completed an online baseline questionnaire and were randomized to an intervention (4 computer-tailored, online, asthma management sessions) or control group (4 sessions of access to existing asthma management websites). Students completed follow-up questionnaires at 6 and 12 months. Caregivers completed a baseline and 12-month telephone interview. In each computer session, after students responded to questions on attitudes and beliefs, computer algorithms are used to select appropriate feedback from a message library created by medical experts and behavioral scientists on the Puff City team. The information is used to assemble preprogrammed tailored feedback that is normative (compared with other teens) and ipsative (compared with your last session), resulting in a wide variety of message permutations. Visual aids help teens identify their current asthma medications. All Puff City surveys are voiced-over to accommodate literacy limitations. Puff City’s data management system allows for report generation and study monitoring and tracking.

Intervention students also had access to an Asthma Referral Coordinator (ARC) who made referrals to the appropriate resources for medication, health insurance, and depression. Using a risk assessment algorithm that collated student responses, the ARC proactively contacted students in the intervention group. Students were usually referred to school-based resources, but community-based resources were used when school resources were not available. The ARCs did not provide asthma education. Caregivers were contacted when appropriate and with student permission.

Study definitions and outcomes

For this analysis, current asthma was defined as report of a physician diagnosis of asthma, use of prescribed asthma medication in the last 12 months, and at least 1 episode of wheeze in the last 12 months. Classification of asthma severity used in this study was adapted from Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma from the EPR-3 (Figure 14. Classification of Asthma Severity [> 12 Months of Age]), using nighttime symptoms.6 As in previous studies, investigators interpreted and assigned numeric values when terms such as frequent and continual were used in the EPR-3 criteria. Depression in teens was defined as a yes to 5 or more of 7 questions about depressive symptoms in the preceding 6 months from the Diagnostic Predictive Scales46 completed by the teen. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children is a structured diagnostic instrument that was specifically designed for use by nonclinicians.47 The fourth version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children was further adapted to create several scales that were used as screening tools for various psychiatric diagnoses, including depression.46 These scales (known as Diagnostic Predictive Scales) have been tested in various populations and have been reported to be efficient and reliable screening tools for school-age children.48,49 Caregiver depression was defined as a response of 8 days’ duration or greater to 4 or more of the questions on the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 completed by the caregiver.50 It is based on the 9 diagnostic criteria for depression as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) and queries the caregivers about depressive symptoms in the prior 2 weeks. Outcome measures for this analysis included indicators of uncontrolled asthma and QOL at 12 months. Indicators of uncontrolled asthma were obtained from teen questionnaire responses using frequency of symptoms in last 30 days (>3 nights, >8 days), limitation or change of usual activities (>4 days), and schooldays missed (>2 days) due to asthma in the last 30 days. With the exception of days changed plans and school days missed, indicators of uncontrolled asthma were adapted from EPR-3 (Figure 15. Classification of Asthma Control [≥12 Years of Age]).6

The QOL scores were derived from the Paediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire51 completed by the student. This questionnaire was developed for children 7 to 17 years and can be self-administered after the age of 11 years. It is a well-standardized questionnaire that uses 23 questions covering 3 domains (symptoms [10 items], activity limitation [5 items], and emotional function [8 items]) with responses graded on a 7-point scale (with 7 indicating not bothered at all and 1 indicating extremely bothered). The overall Paediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score is a mean of the responses to all 23 questions. Domain scores are the means of the responses to the domain questions. Lower scores represent lower QOL. A change in score of 0.5 or more is considered clinically meaningful.52

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was defined as a P<.05. For bivariate comparisons, χ2 tests for categorical variables (with pairwise comparisons as appropriate) were used. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used for continuous or ordinal variables. Logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to describe treatment and control comparisons, beginning with a model containing key variables (as determined a priori and from the literature) and the baseline value for the dependent variable (the outcome of interest). Potential confounders (caregiver depression, age, sex, school of enrollment, baseline asthma severity, Medicaid enrollment, caregiver education, environmental tobacco smoke, student smoking, number of sessions completed, and physician diagnosis of asthma) were included in the logistic regression model if found to change the OR for the association of intervention arm to study outcome by 20% or more. For physician diagnosis of asthma, caregiver baseline report was used if teen baseline response was “don’t know.” An interaction term was entered into each model to assess whether the intervention effect differed by baseline depression status, indicated by a P < .20.

Results

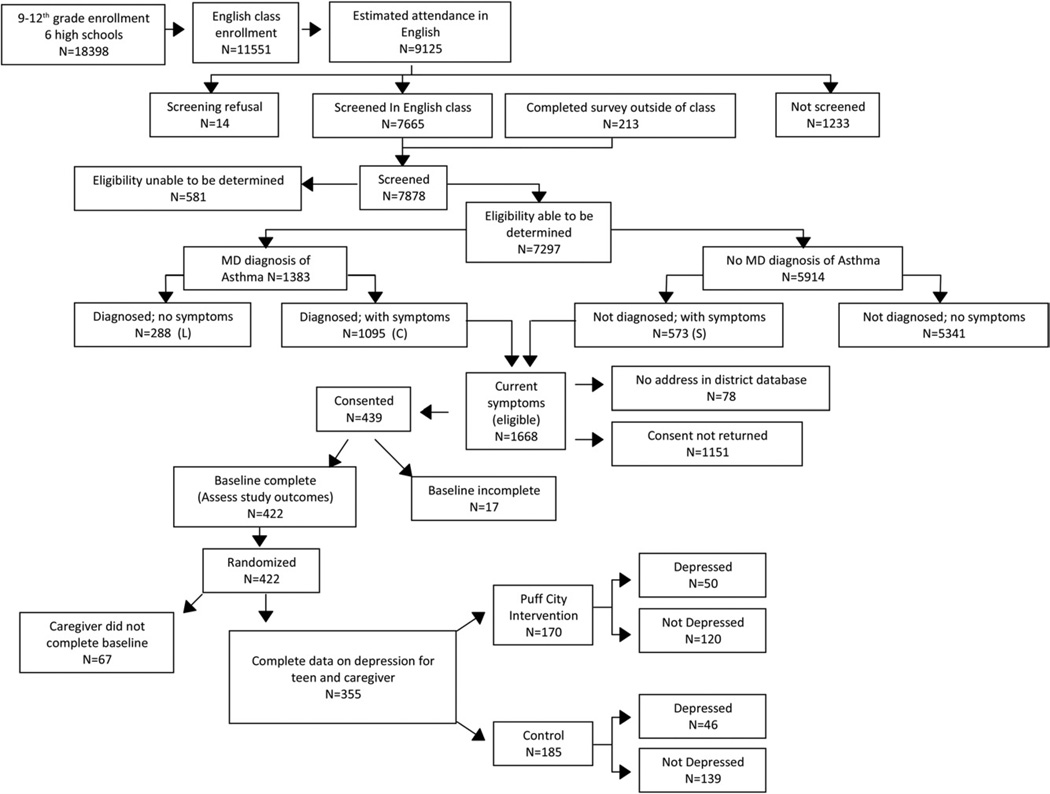

For the 6 high schools that participated in this intervention trial, there were 18,398 students enrolled in grades 9 through 12 at the start of the study (2007–2008), of which 11,551 students were enrolled in an English class, and 9,125 were in attendance in a scheduled English class on the dates the Lung Health Survey was administered. From among these students, 14 refused the survey, 1,233 were absent or not in class at the time of the survey, and a total of 7,878 completed the survey, of which 1668 finally met the eligibility criteria for participation in the RCT (Fig 1). A total of 439 caregivers provided written informed consent. Although 422 teens completed the baseline assessment, 67 caregivers did not complete a baseline interview, leaving a total of 355 teen-caregiver pairs with sufficient data for this analysis. These 355 teens were more likely to complete other aspects of the intervention (eg, computer sessions and follow-up forms) than teens not included in the analysis. In addition, teens included in the analysis were younger than those not included, although this was of borderline significance (eTable 1). Teens included in the analysis did not significantly differ from those excluded with regard to sex, exposure to environmental tobaccos smoke, smoking, Medicaid enrollment, indicators of uncontrolled asthma, medical care use, and asthma severity. The QOL scores at baseline were compared by baseline depression (before randomization). Before randomization, teens who met the study criteria for depression had significantly lower baseline QOL scores overall and for each domain compared with teens who did not report depressive symptoms at baseline (P < .001) (eFig 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for Puff City randomized controlled trial showing details of enrollment and randomization into treatment and control groups. Of the 9,125 students in English class, 1,233 were not screened because they were either absent or not present in class at the time the questionnaire was administered.

Table 1 is a comparison of teens in the intervention and control groups. Treatment students reported more days of restricted activity (>4 days in last 30 days) (P = .03) and emergency department visits (>1 visit in the last 12 months) (P=.04) than controls. The groups did not differ with regard to sociodemographic variables, indicators of uncontrolled asthma, and depression status. In the treatment group, 50 students met criteria for depression at session 1, and of those, 48 of 50 (96%) were contacted by the ARC (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 355 students enrolled in a randomized trial of an asthma management program and included in analysis by randomization groupa

| Characteristic | Intervention, No. (%) (n = 170) |

Control, No. (%) (n = 185) |

P value | No. missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician diagnosis of asthma | .65 | |||

| Yes | 133 (78.2) | 151 (81.6) | ||

| NO | 30 (17.7) | 26 (14.1) | ||

| Don’t know | 7 (4.1) | 8 (4.3) | ||

| Completed all 4 sessions | 149 (87.7) | 173 (93.5) | .06 | |

| Completed 6-month follow-up | 144 (84.7) | 166 (89.7) | .16 | |

| Completed 12-month follow-up | 157 (92.3) | 171 (92.4) | .98 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 15.8 (1.1) | 15.9 (1.2) | .78 | |

| Female | 100 (58.8) | 107 (57.8) | .85 | |

| Exposed to household ETS | 108 (64.3) | 121 (66.9) | .61 | 6 |

| Smoke >2 cigarettes on days smoked in last 30 days | 18 (10.8) | 22 (12.0) | .72 | 5 |

| Medicaid enrollment | 99 (58.6) | 110 (60.4) | .63 | 4 |

| Indicators of uncontrolled asthmab | ||||

| >8 Symptom-days in last 30 days | 44 (25.9) | 53 (28.6) | .56 | |

| >3 Symptom-nights in last 30 nights | 57 (34.1) | 65 (36.1) | .70 | 8 |

| >4 Days of restricted activity in last 30 days | 61 (35.9) | 87 (47.0) | .03 | |

| >4 Days had to change plans in last 30 days | 26 (15.7) | 24 (13.3) | .54 | 9 |

| >2 Schooldays missed due to asthma in last 30 days | 39 (23.6) | 37 (20.6) | .49 | 10 |

| Medical care use | ||||

| >1 Hospitalization in last 12 months | 28 (16.5) | 34 (18.5) | .62 | 1 |

| >1 Emergency department visit in last 12 months | 72 (42.3) | 58 (31.7) | .04 | 2 |

| Asthma severityc | ||||

| Mild, intermittent to persistent | 127 (74.7) | 140 (75.7) | .83 | |

| Moderate to severe | 43 (25.3) | 45 (24.3) | ||

| Teen depression | 50 (29.4) | 46 (24.9) | .34 | |

| Caregiver depression | 21 (12.4) | 25 (13.5) | .75 |

Abbreviation: ETS, environmental tobacco smoke.

Students who enrolled in the study, completed baseline assessment, and caregiver completed baseline assessment (84% of those enrolled) are presented. Data are presented as number (percentage) of students unless otherwise indicated.

Indicators of uncontrolled asthma adapted from the Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma from the Expert Panel Report 3 (Figure 15. Classification of Asthma Control [≥12 Years of Age]), with exception of days changed plans and school days missed.6

Classification of asthma severity and cutoffs adapted from the Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma from the Expert Panel Report 3 (Figure 14. Classification of Asthma Severity [≥12 Years of Age]), using nighttime symptoms.6

We first examined the association between the intervention arm and indicators of uncontrolled asthma at 12 months. For this association, there was no evidence of an interaction with baseline depression (all P values for assessment of interaction >.50; e-Tables 2 and 3). Results of logistic regression analyses are presented in Table 2. The percentage of treatment students experiencing uncontrolled asthma as indicated by symptom-days, days of restricted activity, and schooldays missed were significantly lower for treatment students compared with controls (Table 2). The ORs for symptom-nights, changed plans, and school missed due to asthma showed a trend toward treatment benefit but did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Results of logistic regression analysis for association between intervention arm and indicators of uncontrolled asthma at 12-month follow-up for the analysis of 355 teens participating in a randomized trial of Puff City

| Indicatora | Intervention, No. (%) (n = 170) |

Control, No. (%) (n = 185) |

Adjusted ORb |

95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >8 Symptom-days in last 30 days (or ≥2 days per week) | 17 (10.0) | 35 (18.9) | 0.38 | 0.19–0.77 | 0.01 |

| ≥3 Symptom-nights in last 30 nights | 39 (22.9) | 54 (29.2) | 0.67 | 0.39–1.14 | 0.14 |

| >4 Days of restricted activity in last 30 days | 31 (18.2) | 55 (29.7) | 0.52 | 0.30–0.89 | 0.02 |

| >4 Days had to change plans in last 30 days | 16 (9.4) | 21 (11.4) | 0.68 | 0.31–1.48 | 0.33 |

| >2 Schooldays missed in last 30 days | 53 (31.2) | 77 (41.6) | 0.56 | 0.35–0.90 | 0.02 |

| >2 Schooldays missed due to asthma in last 30 days | 20 (11.8) | 25 (13.5) | 0.78 | 0.40–1.52 | 0.46 |

In the last 30 days.

Adjusted logistic regression, adjusting for baseline measurement, baseline asthma severity, school of enrollment, teen sex, and caregiver depression.

Table 3.

Quality of life at 12 months for 96 teens depressed at baseline, from the analysis of 355 teens participating in a randomized trial of Puff Citya

| Quality of life | Intervention, mean (SD) |

Control, mean (SD) |

Adjusted RR (95% CI)b |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 4.5 (1.5) | 4.1 (1.6) | 1.57c (0.93–2.63) | .09 |

| Activity | 3.8 (1.5) | 3.7 (1.7) | 0.98 (0.54–1.78) | .95 |

| Symptoms | 4.7 (1.6) | 4.1 (1.6) | 1.72 (0.94–3.15) | .08 |

| Emotional | 4.9 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.8) | 2.08 (1.20–3.63) | .01 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

Scale of 1 to 7, where 7 is higher quality of life.

Adjusted RR (95% CI) were adjusted for baseline measurement, baseline asthma severity, school of enrollment, teen sex, and caregiver depression.

Interpreted as, on average, treatment quality of life score is increased by 1.57 over that of control overall QOL score.

In assessing depression as an effect modifier of the relationship between treatment assignment and overall QOL at 12 months, the interaction P value was .22. For the activity, symptoms, and emotions scale, the interaction P values were .75, .13, and .06, respectively. Our criterion for the presence of interaction was 0.20. Given that the overall P value was very close to .20 and P values for 2 of 3 QOL domains met our criteria for interaction, we have presented stratified results (Table 3 and Table 4). Among teens with reports of depression at baseline, QOL scores overall and for the symptoms domain were higher for treatment students compared with controls (adjusted RR, 1.57 and 1.72, respectively) but were of borderline significance. Intervention and control QOL scores for the emotions domain among teens who were depressed were 4.9 and 4.4, respectively (adjusted RR, 2.08; P = .01), indicating intervention benefit for emotional QOL among depressed students (interpreted as the emotional QOL score for treatment students is increased by a factor of 2.08 above that of controls). Among teens without depressive symptoms at baseline, QOL scores for treatment teens did not differ significantly from those in the control group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Quality of life at 12 months for 259 teens not depressed at baseline, from the analysis of 355 teens participating in a randomized trial of Puff Citya

| Quality of life | Intervention, mean (SD) |

Control, mean (SD) |

Adjusted RR (95% CI)b |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.3 (1.5) | 1.03 (0.78–1.37) | .81 |

| Activity | 4.9 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.5) | 1.07 (0.77–1.48) | .70 |

| Symptoms | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.5) | 0.98 (0.72–1.34) | .89 |

| Emotional | 5.8 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.6) | 1.05 (0.77–1.43) | .78 |

Scale of 1 to 7, where 7 is higher quality of life.

Adjusted RR (95% CI) were adjusted for baseline measurement, baseline asthma severity, school of enrollment, teen sex, and caregiver depression.

Discussion

QOL is an important component of the control and monitoring of asthma. The EPR-3 emphasizes the importance of periodic assessment of QOL and related loss of physical function as part of monitoring the response to therapy. The EPR-3 further enumerates several dimensions of QOL that are important to track, including physical function, role function, and mental health function,6 which are the same as the QOL domains assessed in this study. Mental health function can be related to a number of factors, with depression being one of the important comorbidities that is seen in patients with asthma.

We examined whether depressive symptoms modified the relationship between intervention arm (Puff City) and intervention effectiveness, as measured by indicators of uncontrolled asthma and QOL. According to our results, fewer intervention students had indications of uncontrolled asthma, and baseline depression did not affect this relationship. However, the intervention seemed especially effective in improving emotional QOL among students with depressive symptoms at baseline.

Because of a known association and higher prevalence of depression in urban teens with asthma,53,54 we were specifically interested in exploring the effect of depression on the effectiveness of this asthma intervention. Although previous literature describes how the presence of depression in teens with asthma correlates with higher health care use rates and lower QOL,55,56 we are unaware of reports on how depression modifies the response to an asthma intervention for urban teenagers.

The effect of depression status on the response to treatment or intervention has also been studied in several other disease models, such as substance abuse in teens,57 and chronic medical conditions in adults, such as diabetes58 and ischemic heart disease.59 In general, rates of health care use for patients with chronic medical conditions accompanied by comorbid depression are higher.60,61 These patients are also at high risk for poor adherence to recommended treatments or interventions, and depression has been noted to be a significant risk factor for nonadherence in adults with chronic medical conditions.62

The effect of an asthma management intervention on emotional QOL, in relation to the depression status of participants, has not been previously reported in urban teens with asthma. In adults with asthma participating in the RCT of a self-management intervention, Mancuso et al63 observed that a positive screen for depression was associated with worse outcomes. Among controls, depressed participants had worse outcomes than nondepressed controls. Conversely, within the intervention group, the observed intervention benefit was similar by depression status. The investigators concluded that the intervention served to buffer participants in the intervention group from the negative effects of depression. The study by Mancuso et al63 observed depression as a predictor of poor outcomes but did not look for a formal statistical interaction. Our results suggest that the effect of the Puff City intervention on emotional QOL is modified in the presence of depressive symptoms. Because depression is considered an emotional disorder,64–67 it seems plausible that the strongest association between intervention arm and QOL among depressed students would be observed in the domain of emotions.

In addition to a relatively small sample size and the use of self-report data, the potential for misclassification of depression is a potential limitation to our study. We used a screening tool for symptoms of depression (diagnostic predictive scales), which is not the same as a clinical diagnosis of depression. We note, however, that the prevalence of depression symptoms in our study population (96 [27%] of 355) is similar to the prevalence of depressive feelings in the past year for 9th through 12th graders in Michigan of 27.4% in 2009.68

Misclassification of students with possible asthma (symptoms only) is also a possibility in our study. Our eligibility criteria were taken from definitions that have been used in national and international studies, have been reported in the literature (eg, International Study of Allergy and Asthma in Childhood), and have been found to be reliable.69

Our process for identifying students with asthma symptoms began with English classes. English is a yearly curriculum requirement for the high schools in this district. Use of this approach to identify students potentially eligible for the RCT may have resulted in missing students not yet assigned to an English class at the time of the survey and students who were using electives to fulfill the English requirement. In this way, our results are only generalizable to students with characteristics similar to the students enrolled and present in English classes at the time the survey was administered.

Importantly, we are unable to determine the mechanism by which depression modifies the relationship between intervention effectiveness and emotional QOL. It is possible that intervention content may have affected depression directly, but it is also possible that other factors not related to the intervention or indirectly related to the intervention (eg, referrals for depression from the ARC) may have been influential as well. We acknowledge that the observed relationships among depressive symptoms, emotional QOL, and intervention effectiveness may be due to other factors that we did not measure and did not adjust for in our analysis.

To conclude, depression in youth with any chronic medical condition can have a significant effect on QOL and health outcomes. Our data suggest that the measured effect of a self-management intervention for asthma on emotional QOL is modified by baseline depression status. Further assessment of self-management behavioral interventions for asthma should include an investigation of the mechanisms by which intervention content, referrals, or treatment for depression may interact in such a way as to modify intervention effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01 HL67462-01.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi.10.1016/j.anai.2012.07.010.

References

- 1.Vital signs: asthma prevalence, disease characteristics, and self-management education: United States, 2001–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moorman JE, Rudd RA, Johnson CA, King M, Minor P, Bailey C, Scalia MR, Akinbami LJ. National surveillance for asthma–United States, 1980–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJMJ, Liu X. Asthma Prevalence, Health Care Use, and Mortality: United States, 2005–2009. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. National Health Statistics Report 32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnett SB, Nurmagambetov TA. Costs of asthma in the united states: 2002–2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams D, Portnoy JM, Meyerson K. Strategies for improving asthma outcomes: a case-based review of successes and pitfalls. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16:S3–S17. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.S1-C.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institutes of Health. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health; 2007. NIH publication 07–4051. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenzel SE, Lumry W, Manning M, Kalberg C, Cox F, Emmett A, Rickard K. Efficacy, safety, and effects on quality of life of salmeterol versus albuterol in patients with mild to moderate persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;80:463–470. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juniper EF, Jenkins C, Price MJ, James MH. Impact of inhaled salmeterol/fluticasone propionate combination product versus budesonide on the health-related quality of life of patients with asthma. Am J Respir Med. 2002;1:435–440. doi: 10.1007/BF03257170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price DB, Williams AE, Yoxall S. Salmeterol/fluticasone stable-dose treatment compared with formoterol/budesonide adjustable maintenance dosing: Impact on health-related quality of life. Respir Res. 2007;8:46. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S94–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maiman LA, Green LW, Gibson G, MacKenzie EJ. Education for self-treatment by adult asthmatics. JAMA. 1979;241:1919–1922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Palen J, Klein JJ, Zielhuis GA, van Herwaarden CL. The role of self-treatment guidelines in self-management education for adult asthmatics. Respir Med. 1998;92:668–675. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caplin DL, Creer TL. A self-management program for adult asthma, III: maintenance and relapse of skills. J Asthma. 2001;38:343–356. doi: 10.1081/jas-100000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creer TL, Caplin DA, Holroyd KA. A self-management program for adult asthma, part IV: analysis of context and patient behaviors. J Asthma. 2005;42:455–462. doi: 10.1081/JAS-67958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George M, Campbell J, Rand C. Self-management of acute asthma among low-income urban adults. J Asthma. 2009;46:618–624. doi: 10.1080/02770900903029788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang TT. Self-care behavior of adult asthma patients. J Asthma. 2007;44:613–619. doi: 10.1080/02770900701540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaya Z, Erkan F, Ozkan M, Ozkan S, Kocaman N, Ertekin BA, Direk N. Self-management plans for asthma control and predictors of patient compliance. J Asthma. 2009;46:270–275. doi: 10.1080/02770900802647565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vazquez MI, Buceta JM. Psychological treatment of asthma: effectiveness of a self-management program with and without relaxation training. J Asthma. 1993;30:171–183. doi: 10.3109/02770909309054515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinstein AG. Direction, motivation, and successful self-management of asthma: focus on drug compliance. J Asthma. 1984;21:281–283. doi: 10.3109/02770908409077435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snyder SE, Winder JA, Creer TJ. Development and evaluation of an adult asthma self-management program: wheezers anonymous. J Asthma. 1987;24:153–158. doi: 10.3109/02770908709070931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark NM, Feldman CH, Freudenberg N, Millman EJ, Wasilewski Y, Valle I. Developing education for children with asthma through study of self-management behavior. Health Educ Q. 1980;7:278–297. doi: 10.1177/109019818000700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chini L, Iannini R, Chianca M, et al. Happy air(r), a successful school-based asthma educational and interventional program for primary school children. J Asthma. 2011;48:419–426. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.563808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thoresen CE, Kirmil-Gray K. Self-management psychology and the treatment of childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983;72:596–606. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(83)90487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibutani S, Iwagaki K. Self-management programs for childhood asthma developed and instituted at the Nishinara-Byoin National Sanatorium in Japan. J Asthma. 1990;27:359–374. doi: 10.3109/02770909009073353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown JV, Avery E, Mobley C, Boccuti L, Golbach T. Asthma management by preschool children and their families: a developmental framework. J Asthma. 1996;33:299–311. doi: 10.3109/02770909609055371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bursch B, Schwankovsky L, Gilbert J, Zeiger R. Construction and validation of four childhood asthma self-management scales: parent barriers, child and parent self-efficacy, and parent belief in treatment efficacy. J Asthma. 1999;36:115–128. doi: 10.3109/02770909909065155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Espinoza-Palma T, Zamorano A, Arancibia F, et al. Effectiveness of asthma education with and without a self-management plan in hospitalized children. J Asthma. 2009;46:906–910. doi: 10.3109/02770900903199979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kauppinen RS, Vilkka V, Hedman J, Sintonen H. Ten-year follow-up of early intensive self-management guidance in newly diagnosed patients with asthma. J Asthma. 2011;48:945–951. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.616254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarke SA, Calam R. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions designed to improve health-related quality of life (HRQOL) amongst asthmatic children and their families: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:747–764. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9996-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bahreinian S, Ball GD, Colman I, Becker AB, Kozyrskyj AL. Depression is more common in girls with nonatopic asthma. Chest. 2011;140:1138–1145. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bender BG. Risk taking, depression, adherence, and symptom control in adolescents and young adults with asthma. AmJ Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:953–957. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1706PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartlett SJ, Krishnan JA, Riekert KA, Butz AM, Malveaux FJ, Rand CS. Maternal depressive symptoms and adherence to therapy in inner-city children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2004;113:229–237. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown ES, Gan V, Jeffress J, et al. Psychiatric symptomatology and disorders in caregivers of children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1715–e1720. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joseph CL, Peterson E, Havstad S, et al. A web-based, tailored asthma management program for urban african-american high school students. AmJ Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:888–895. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1244OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenstock I. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:328–335. [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Institutes of Health. Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fiese BH, Wamboldt FS, Anbar RD. Family asthma management routines: connections to medical adherence and quality of life. J Pediatr. 2005;146:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farber HJ, Capra AM, Finkelstein JA, et al. Misunderstanding of asthma controller medications: association with nonadherence. J Asthma. 2003;40:17–25. doi: 10.1081/jas-120017203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robertson CF, Rubinfeld AR, Bowes G. Pediatric asthma deaths in victoria: the mild are at risk. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1992;13:95–100. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950130207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raherison C, Tunon-de-Lara JM, Vernejoux JM, Taytard A. Practical evaluation of asthma exacerbation self-management in children and adolescents. Respir Med. 2000;94:1047–1052. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57:1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joseph CL, Havstad SL, Johnson D, et al. Factors associated with nonresponse to a computer-tailored asthma management program for urban adolescents with asthma. J Asthma. 2010;47:667–673. doi: 10.3109/02770900903518827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joseph CL, Baptist AP, Stringer S, et al. Identifying students with self-report of asthma and respiratory symptoms in an urban, high school setting. J Urban Health. 2007;84:60–69. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9121-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Redding C, Pallonen U, Rossi J, et al. Transtheoretical individualized multimedia expert systems targeting adolescents’ health behaviors. Cogn Behav Pract. 1999;6:144–153. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW, et al. The disc predictive scales (DPS): efficiently screening for diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:443–449. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cubo E, Velasco SS, Benito VD, et al. Psychometric attributes of the disc predictive scales. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2010;6:86–93. doi: 10.2174/1745017901006010086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leung PW, Lucas CP, Hung SF, et al. The test-retest reliability and screening efficiency of DISC Predictive Scales-Version 4.32 (DPS-4.32) with Chinese children/youths. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;14:461–465. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in children with asthma. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:35–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00435967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE. Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:81–87. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richardson LP, Lozano P, Russo J, McCauley E, Bush T, Katon W. Asthma symptom burden: relationship to asthma severity and anxiety and depression symptoms. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1042–1051. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katon W, Lozano P, Russo J, McCauley E, Richardson L, Bush T. The prevalence of DSM-IV anxiety and depressive disorders in youth with asthma compared with controls. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCauley E, Katon W, Russo J, Richardson L, Lozano P. Impact of anxiety and depression on functional impairment in adolescents with asthma. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richardson LP, Russo JE, Lozano P, McCauley E, Katon W. The effect of comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders on health care utilization and costs among adolescents with asthma. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Warden D, Riggs PD, Min SJ, et al. Major depression and treatment response in adolescents with ADHD and substance use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katon W, Unutzer J, Fan MY, et al. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:265–270. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Denollet J, Vaes J, Brutsaert DL. Inadequate response to treatment in coronary heart disease: adverse effects of type D personality and younger age on 5-year prognosis and quality of life. Circulation. 2000;102:630–635. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.6.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simon GE. Treating depression in patients with chronic disease: recognition and treatment are crucial; depression worsens the course of a chronic illness. West J Med. 2001;175:292–293. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.5.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simon GE, Manning WG, Katzelnick DJ, Pearson SD, Henk HJ, Helstad CS. Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment for high utilizers of general medical care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:181–187. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mancuso CA, Sayles W, Allegrante JP. Randomized trial of self-management education in asthmatic patients and effects of depressive symptoms. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peeters F, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J, Delespaul P, deVries M. Effects of daily events on mood states in major depressive disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:203–211. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murphy FC, Michael A, Sahakian BJ. Emotion modulates cognitive flexibility in patients with major depression. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1373–1382. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bylsma LM, Morris BH, Rottenberg J. A meta-analysis of emotional reactivity in major depressive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:676–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morris BH, Bylsma LM, Rottenberg J. Does emotion predict the course of major depressive disorder? a review of prospective studies. Br J Clin Psychol. 2009;48:255–273. doi: 10.1348/014466508X396549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Michigan Epidemiological Profile: Focusing on Abuse of Alcohol, Prescription Drugs, Tobacco, and Mental Health Indicators. Lansing, MI: State Epidemiology Outcomes Workgroup; 2011. Michigan Department of Community Health. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weiland SK, Bjorksten B, Brunekreef B, Cookson WO, von Mutius E, Strachan DP. Phase II of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC II): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:406–412. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00090303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.