Abstract

Cancer starts with a change in one single cell. This change may be initiated by external agents and genetic factors. Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide and accounts for 7.6 million deaths (around 13% of all deaths) in 2008. Lung, stomach, liver, colon and breast cancer cause the most cancer deaths each year. In this review, different aspects of gastric cancer; including clinical, pathological characteristic of gastric cancer, etiology, incidence, risk factors, prevention and treatment are studied.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, Gastric carcinoma, Stomach cancer

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide: it accounted for 7.9 million deaths (around 13% of all deaths) in 2008. The rising life expectancy means that the risk of developing cancer is also increasing. Deaths from cancer worldwide are projected to continue rising, with an estimated 12 million deaths in 2030. As most cancers appear in adults at an advanced age, the burden of cancer is much more important than other diseases in populations with a long life expectancy (1–3). The eight leading cancer killers worldwide are also the eight most common in terms of incidence. Together, they account for about 60% of all cancer cases and deaths. They are cancers of the lung, stomach, breast, colon-rectum, mouth, liver, cervix and oesophagus.

Gastric cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide and almost two-thirds of all cases occur in developing countries. It is the fourth most common cancer in men, while in women it is the fifth most common cancer (based on statistic in 2008). Although the incidence of gastric cancer is declining, it still remains a major health problem and a common cause of cancer mortality worldwide (4, 5). Gastric cancer carcinogenesis refers to accumulation of genetic alteration of multiple genes such as oncogenes, tumour suppressor and mismatch repair genes (6).

The dynamic balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis is very important to maintain the homeostasis in human body and gastric carcinogenesis is related to this imbalance (7). Development of gastric cancer is believed to be a slow process with primary etiological determinants for gastric cancer being exposure to chemical carcinogens and/or infection with Helicobacter pylori (8, 9). It has been reported that gastric cancer also expresses multidrug-resistance associated protein (MRP) and shows lower sensitivity to anti-cancer drugs (10). Gastric cancer is more common in older populations, usually occurring in the seventh and eighth decades of life. The mean age at diagnosis was 67 years in one large series. Although suspected, there is current uncertainty as to whether gastric cancer in young patients is associated with a worse clinical outcome (11, 12).

Clinical/pathological characteristics of gastric cancer

Stomach is the most commonly involved site (60%-75%) in gastrointestinal tract followed by small bowel, ileocecal region and rectum (13). Several different types of cancer can occur in the stomach. The most common type is called adenocarcinoma. Approximately 90% of gastric cancers are adenocarcinoma. Adenocarcinoma is believed to arise form a single cell. Adenocarcinoma of the stomach is a common cancer of the digestive tract worldwide, although it is uncommon in the United States. It occurs most often in men over age 40. The rate of most types of gastric adenocarcinoma in the United States has gone down over the years. Researchers think the decrease may be because people are eating less salted, cured, and smoked foods. There are two types of gastric adenocarcinoma based upon anatomical location: cardia, or proximal, and distal, noncardia adenocarcinomas. These should be considered as separate entities because of differing epidemiologic relationships, associated risk factors, and prognosis. Historically, distal gastric carcinoma was the most frequent type. However, because the rate of cardia tumors continues to increase while that of distal gastric cancers decreases (14, 15), the incidence of proximal adenocarcinoma has surpassed that of distal cancers in recent years. This is an unfortunate change in the epidemiology of the disease since cancers of the gastric cardia generally have worse prognosis than distal gastric cancers (15). Bormann recognized four basic growth patterns for gastric carcinomas, and categorized them as follows (some tumors show a combination of these patterns): polypoid (type I), fungating (type II), ulcerated (type III), and diffusely infiltrative (type IV). It was recognized that a gastric ulcer may be benign or malignant. Gross features that have been associated with malignancy in gastric ulcers include irregular, heaped-up margins and a location on the greater curvature near the pylorus.

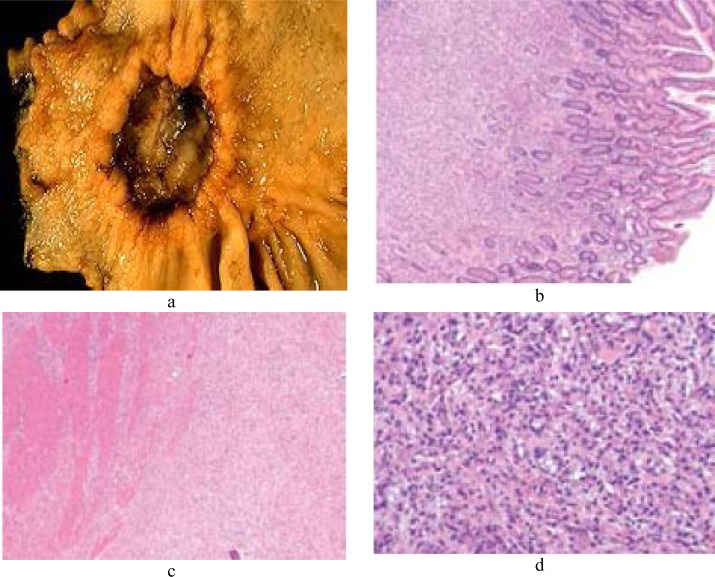

In practice, confident differentiation of benign ulcers from malignant ulcers requires microscopic examination of biopsies in many cases (16). On microscopic examination, gastric cancer is divided into two main types: well-differentiated, intestinal type and undifferentiated, diffuse type (17) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Morphological and cellular illustrations related to gastric cancer. A suspicious stomach ulcer that was diagnosed as cancer on biopsy and resected (a). Tumor cells fill the lamina propria, leaving benign glands largely undisturbed (b). Tumor cells infiltrate the muscularis propria (c). In diffuse-type carcinoma, glandular structures are abortive (d).

This histologic type is seen throughout the world, whereas the intestinal type occurs in areas with a high incidence of gastric cancer and follows a predictable stepwise progression of cancer development from metaplasia. Intestinal-type gastric carcinomas are usually characterized by the presence of gland-forming mitotically active columnar cells with enlarged, darkly staining (with hematoxylin) nuclei, with accumulation of mucin in the lumina of these malignant glands, and without much intracellular accumulation of mucin (18).

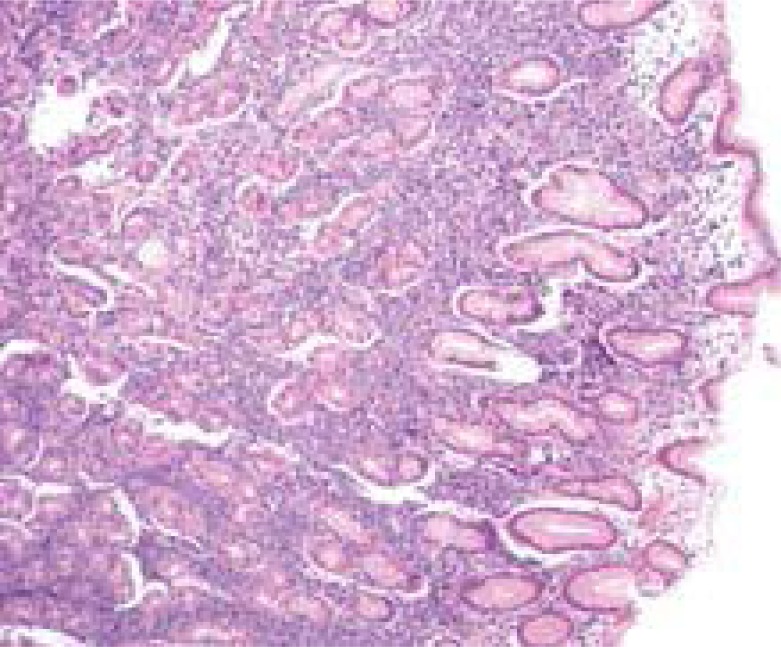

As compared to the cells in intestinal-type carcinomas, diffuse carcinoma cells were smaller, more uniform in overall shape and in nuclear size, and had less mitotic activity (19). Gastric lymphoma accounts for 3%-5% of all malignant tumours of the stomach (20). Although the incidence of gastric carcinoma has been reduced, the incidence of primary gastric lymphoma is increasing (21). H. pylori play a role in the development of most MALT lymphomas (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Illustration of gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

However, its exact mechanism has not been fully understood, although a chronic inflammation may enhance the probability of malignant transformation via B cell proliferation in response to H. pylori mediated by tumour-infiltrating T cells (20). H. pylori may play a similar role in development of DLBCL (diffuse large B cell lymphoma) and few studies have shown complete remission after eradication therapy alone (21).

Causes and incidence of gastric cancer

The development of gastric cancer is a multifactorial process and many conditions influence the likelihood of occurrence, of them, family history of gastric cancer, Helicobacter pylori infection (a common bacteria that can also cause stomach ulcers), history of an adenomatous gastric polyp larger than 2 centimetres, history of chronic atrophic gastritis, history of pernicious anemia, obesity, alcohol, smoking, red meat and low socioeconomic status are all believed to be important.

The important risk factors of the causes of gastric cancer are H. pylori, obesity, smoking, red meat, alcohol, and low socioeconomic status (22).

In 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer and The World Health Organization classified Helicobacter pylori as a type I carcinogen, the exact mechanism leading to gastric carcinoma is not clearly understood. The effects of H. pylori infection on gastric cancer appear multifactorial, involving host and environmental factors as well as differing bacterial strains. H. pylori is most closely associated with intestinal gastric cancers, which follow a stepwise pathway but toward malignancy, similar to that in the colon. In the Correa model of gastric carcinogenesis, gastric inflammation leads to mucosal atrophy, metaplasia, dysplasia, and, ultimately, carcinoma (23). Studies have shown that H. pylori infection is an independent risk factor for distal gastric cancer, with a 3- to 6-fold increased risk relative to those without the infection (24–26). In patients with H. pylori, the presence of specific gene polymorphisms increases the risk of developing gastric carcinoma. Genes that encode tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interleukins IL-1, IL-8, and IL-10 have each been associated with higher cancer rates in the setting of H. pylori (27, 28). While intestinal gastric cancer is strongly associated with chronic H. pylori, this strong link is not seen in diffuse gastric cancer. Diffuse or cardia gastric cancer, however, has been associated with other risk factors such as higher socioeconomic class (29), obesity (30, 31), and type A blood (32).

Ethnic and geographic factors

There is a higher incidence of gastric cancer in non-Caucasian populations. In the United States, the highest incidence is found in the Native American (21.6/100,000) and Asian (20/100,000) populations. Both race and sex affect the risk of disease development and subsequent mortality rate. The highest mortality rate based upon ethnic/sex combination is African-American males (12.4/100 000) (33). However, there are similar overall 5-year survival rates among the different races. The incidence of gastric carcinoma also varies dramatically by geographic location. In contrast to the American population, the societal burden of gastric cancer is much higher in Japan where it is the most common tumor type, accounting for approximately 19% of new tumor diagnoses based upon 2001 cancer registry data (34). In Japanese men, the incidence rate is 116/100 000 (34).

Genetics

There are a variety of genes that increase the risk of gastric cancer that are detailed in Specific genes such as MCC, APC, and p53 tumor suppressor genes have been identified in a large percentage of gastric cancers (35). Several studies have identified E-cadherin, a calcium-dependent adhesion molecule that is responsible for cellular binding to adjacent cells, as an important component in the gastric carcinogenesis cascade (36–38). Genetic susceptibility involves hereditary transmission of a single mutated CDH1 allele. If there is an acquired mutation of the second allele in the E-cadherin gene, then loss of intracellular adhesion leads to increased intracellular permeability (39). A wide variety of mutations in this domain have been identified in gastric cancer families (40). Multiple syndromes are associated with gastric carcinoma; most are associated with gastrointestinal polyp formation and have increased risk of cancer at other sites as well. These include familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Cowden disease. The FAP genetic defect is located in the APC gene involved in the Wnt tumor-signaling pathway. This gene is located on chromosome 5q and involves development of different tumor types, including colonic and gastric cancers (41).

Environmental and behavioral factors

There are many environmental and behavioral factors that affect the development of gastric carcinoma. Smoking is now considered a significant contributor. A meta-analysis in 1997 revealed a 44% increase in risk for gastric cancer for current and ex-smokers (42). In a second more comprehensive meta- analysis in 2007, this increase in risk was reported as 60% for men and 20% for women (43). In a population-based case control study, exposure to smoking at any time during the patient's life had a population-attributable risk of 18% and 45% for the development of both non-cardia and cardia gastric carcinomas, respectively (44).

Unlike tobacco exposure, alcohol consumption has not been consistently shown to be associated with gastric cancer (45–49). Alcohol, however, has been identified as a risk factor for disease progression (50), and the combined effect of alcohol and smoking increases the risk of non-cardia gastric cancer 5-fold (47). Diets with high amounts of fresh vegetables and fruit have been shown to have a protective association with gastric cancer (51, 54). Consumption of high levels of salt and processed meat has been shown to be positively associated with gastric cancer in some studies (51–53, 56, 57) Salted foods have been shown to increase the carcinogenic effects of nitrates in rats (58). Obese patients have an increased risk for cardia type gastric cancer (31, 59). A large prospective cohort study revealed a body mass-index- (BMI-) dependent increased risk of cardia gastric cancer in overweight (incidence rate ratio 1.32) and obese (2.73) subjects (59). In one study, the use of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was associated with approximately 50% decreased risk of non-cardia gastric adenocarcinomas (60). Patients who have had gastric surgery for benign disease are also at 2–4 times increased risk for gastric cancer. This association may result from decreased acid production in the gastric remnant and chronic inflammation due to reflux of bile into the gastric remnant (61).

High-dose radiation exposure is an uncommon risk factor for gastric cancer found primarily in survivors of atomic bomb radiation in World War II (62). A protective effect of vitamin C or beta-carotene has been previously associated with decreased gastric cancer rates.

A randomized controlled chemo-prevented trial revealed that anti- H.pylori treatment, supplementation with ascorbic acid, and supplementation with beta-carotene were each associated with a significant regression of precancerous lesions in the setting of atrophic gastritis (63). In a recent meta-analysis, antioxidants were found to have a protective role against esophageal cancer, and beta-carotene was found to be protective against cardia gastric cancer (odds ratio (OR): 0.57) (64).

Symptoms of gastric cancer

Most patients with gastric carcinoma become symptomatic only after they have advanced lesions with local or distant metastases. Common presenting findings include epigastric pain, bloating, or a palpable epigastric mass. Other patients may have nausea and vomiting due to gastric outlet obstruction, early satiety due to linitis plastica, dysphagia due to cardia involvement, or signs and symptoms of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to ulceration of the tumor. Still other patients with advanced gastric cancer may present with clinical signs of metastatic disease, such as anorexia, weight loss, jaundice, ascites, and hepatic enlargement (65).

Diagnosis of gastric cancer

Early detection is essential for improving outcomes in patients with gastric cancer. With earlier detection, the likelihood of cure with non-surgical endoscopic therapy Increases. Diagnosis is often delayed because symptoms may not occur in the early stages of the disease. Also, patients may self-treat symptoms that gastric cancer has in common with other, less serious gastrointestinal disorders (bloating, gas, heartburn, and a sense of fullness). The following tests can help diagnose gastric cancer: Complete blood count (CBC) to check for anaemia, Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy, Stool test to check for blood in the stools, Upper GI series. Modest changes in the morphology and color of the mucosa are important factors for the diagnosis. The morphologic characteristics of EGC include mild elevation and shallow depression of the mucosa, as well as discontinuity with surrounding mucosa and areas of uneven surface. When the mucosa shows pale redness or fading of color, this indicates significant disease (66). Flexible spectral imaging color enhancement (FICE) is an endoscopic technique that was developed to enhance the capillary and the pit patterns of the gastric mucosa. FICE technology is based on the selection of spectral transmittance with a dedicated wavelength.67 Chromo-endoscopy is performed by spraying dyes such as indigo carmine on the mucosa after thoroughly washing the mucus. This technique is useful in determining the lateral tumor extent (68–71).

Treatment of gastric cancer

Surgery to remove the stomach (gastrectomy) is the only treatment that can cure the condition. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy may help. For many patients, chemotherapy and radiation therapy after surgery may improve the chance of a cure.

The currently used chemotherapeutic agents for gastric cancer are not highly effective because detection and treatments of this cancer are performed in the advanced stages of the disease (72). Chemptherapy or radiation can improve symptoms and may prolong survival, but is not curative. For some patients, a surgical bypass procedure may relieve symptoms (72–74).

The most common chemotherapy components used are mitomycin, fluorouracil, cisplatin, paclitaxel injection, docetaxel injection. There are a lot of studies underway to identify new chemotropic agents; calprotectin seems to be much more potent cytotoxic agent for AGS tumour cells compared to etoposide (calprotectin affect about 20 times more than etoposide on cancer cells) (75, 76).

Expectations (prognosis) of gastric cancer

The prognosis for gastric cancer is variable. Tumours in the lower stomach are cured more often than those in the higher stomach -- gastric cardia or gastroesophageal junction. How far the tumour invades the stomach wall and whether lymph nodes are involved when the patient is diagnosed affect the chances of a cure. When the tumour has spread outside the stomach, a cure is not possible and treatment is designed to improve symptoms (2).

Prevention of gastric cancer

Mass screening programs have been successful at detecting disease in the early stages in Japan, where the risk of gastric cancer is much higher than in the United States. The value of screening in the United States and other countries with lower rates of gastric cancer is not clear. At least one-third of all cancer cases are preventable. Prevention offers the most cost-effective long-term strategy for the control of cancer.

Tobacco use is the single greatest avoidable risk factor for cancer mortality worldwide, causing an estimated 22% of cancer deaths per year. In 2004, 1.6 million of the 7.4 million cancer deaths were due to tobacco use. Due to the seriousness of reversing the tobacco epidemic, the WHO has implemented initiatives to monitor the extent of the problem and to help countries putting in place the effective measures to combat the tobacco epidemic. These tools are essential components of national cancer prevention programmes and will play a key role in reducing cancer incidence.

Dietary modification is another important approach to cancer control. There is a link between physical inactivity and obesity to many types of cancer. Diets with low consumption of red meat, high in fruits and vegetables may have a protective effect against many cancers. (They are also associated with a lower of cardiovascular disease.) The World Health Assembly adopted the WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health, in May 2004 to reduce deaths and diseases.

The bacterium Helicobacter pylori increase the risk of stomach cancer. Development of atrophy and metaplasia of the gastric mucosa are strongly associated with H. pylori infection. Oxidative and nitrosative stress in combination with inflammation plays an important role in gastric carcinogenesis. Preventive measures include vaccination and prevention of infection. H. pylori have been shown to be heterogeneous at the genomic level with a high variability in some genes. The feasibility of preventive vaccination has been proven in animal models (mice, dogs) using whole cell vaccines as well as subunit vaccines comprising selected antigens such as VacA, CagA, NAP, hsp, urease or catalase. One of the difficulties met in vaccine studies is the absence of correlates of protection; another is to develop a vaccine that will be efficacious at the mucosal level. In humans, several Phase I studies have been conducted using: recombinant attenuated Salmonellas expressing H. pylori urease, that showed mediocre immunogenicity by the oral route; an oral whole-cell vaccine adjuvanted with wild-type LT. This study that was discontinued because of excessive side effects; purified urease co-administered with LT, also put on hold; a recombinant VacA, CagA and NAP vaccine in alum that proved to be safe and strongly immunogenic. The companies which were involved are Antex, Acambis and Chiron in the USA and the Commonwealth Serum Labs in Australia. A prophylactic vaccine would be cost-effective in preventing gastric cancer and duodenal ulcer (9).

Future perspective

The number of global cancer deaths is projected to increase by 45% from 2008 to 2030 (from 7.9 million to 11.5 million deaths), influenced in part by an increasing and aging global population. The estimated rise takes into account expected slight declines in death rates for some cancers in high resource countries. New cases of cancer in the same period are estimated to jump from 11.3 million in 2008 to 15.5 million in 2030 based on WHO statistics.

There has been a tremendous leap in the diagnosis, staging and management of gastrointestinal cancer in the last two decades. Identification of the cell surface antigens has led to the introduction of monoclonal antibodies that may enable a more targeted approach for treatments. Another important aspect to be considered is the increasing sensitivity and specificity of imaging techniques like EUS and PET-CT in the diagnosis and staging of gastric cancer. One of important field is the use of molecular imaging with a variety of new radiopharmaceutical agents that target the up regulated specific receptors in cancer cells.

(Please cite as: Zali K, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Azodi M. Gastric cancer: prevention, risk factors and treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2011;4(4):175-185).)

References

- 1.Rustgi AK. Neoplasms of the stomach. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, editors. Cecil medicine. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunderson LL, Donohue JH, Alberts SR. Cancer of the stomach. In: Abeloff MD, et al., editors. Abeloff's clinical oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cancer Institute. Gastric cancer treatment PDQ. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/gastric/HealthProfessional/page1. Updated July 8, 2010.

- 4.Derakhshan MH, Yazdanbod A, Sadjadi AR, Shokoohi B, McColl KEL, Malekzadeh R. High incidence of adenocarcinoma arising from the right side of the gastric cardia in NW Iran. Gut. 2004;53:1262–66. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan XM, Wong BCY, Wang WP, Zhow XM, Cho CH, Yuen ST, et al. Inhibition of proteosome function induced apoptosis in gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:481–88. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holian O, Wahid S, Atten MJ, Attar BM. Inhibition of gastric cancer cell proliferation by resveratrol: role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:809–16. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00193.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou XM, Wong BC, Fan XM, Zhang HB, Lin MC, Kung HF, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs induce apoptosis in gastric cancer cells through upregulation of bax and bak. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1393–97. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Otani T, Yamamoto S, Ikeda S, et al. Effect of helicobacter pylori infection combined with cagA and pepsinogen status on gastric cancer development among Japanese men and women: A nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1341–47. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otaka M, Konishi N, Odashima M, Jin M, Wada I, Matsuhashi T, et al. Is Mongolian gerbil really adequate host animal for study of Helicobacter pylori infection-induced gastritis and cancer? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:297–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomonaga M, Oka M, Narasaki F, Fukuda M, Nakano R, Takatani H, et al. The multidrug resistance-associated protein gene confers drug resistance in human gastric and colon cancers. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1996;87:1263–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1996.tb03142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hundahl SA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base Report on poor survival of U.S. gastric carcinoma patients treated with gastrectomy: Fifth Edition American Joint Committee on Cancer staging, proximal disease, and the “different disease” hypothesis. Cancer. 2000;88:921–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai JF, Kim S, Li C. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis for young gastric adenocarcinoma patients after curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1464–69. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9809-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papaxoinis G, Papageorgiou S, Rontogianni D, Kaloutsi V, Fountzilas G, Pavlidis N, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 128 cases in Greece. A Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group study (HeCOG) Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2140–46. doi: 10.1080/10428190600709226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He YT, Hou J, Chen ZF. Trends in incidence of esophageal and gastric cardia cancer in highrisk areas in China. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:71–76. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282b6fd97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maeda H, Okabayashi T, Nishimori I. Clinicopathologic features of adenocarcinoma at the gastric cardia: is it different from distal cancer of the stomach. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:306–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adachi Y, Mori M, Tsuneyoshi M. Benign gastric ulcer grossly resembling a malignancy: a clinicopathological study of 20 resected cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;16:103–108. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinaltypecarcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ming SC. Gastric carcinoma: a pathobiological classification. Cancer. 1977;39:2475–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197706)39:6<2475::aid-cncr2820390626>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vauhkonen M, Vauhkonen H, Sipponen P. Pathology and molecular biology of gastric cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:651–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrucci PF, Zucca E. Primary gastric lymphoma pathogenesis and treatment: what has changed over the past 10 years? Br J Haematol. 2007;136:521–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogliatti SB, Schmid U, Schumacher U, Eckert F, Hansmann ML, Hedderich J, et al. Primary B-cell gastric lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 145 patients. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1159–70. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90063-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hundahl SA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base Report on poor survival of U.S. gastric carcinoma patients treated with gastrectomy: Fifth Edition American Joint Committee on Cancer staging, proximal disease, and the “different disease” hypothesis. Cancer. 2000;88:921–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process – First American Cancer Society Award lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. Br Med J. 1991;302:1302–305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6788.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398–402. doi: 10.1038/35006081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rad R, Dossumbekova A, Neu B. Cytokine gene polymorphisms influence mucosal cytokine expression, gastric inflammation, and host specific colonisation during Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 2004;53:1082–89. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.029736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell J, McConkey CC. Increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia and adjacent sites. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:440–43. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merry AH, Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Body mass index, height and risk of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2007;56:1503–11. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.116665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindblad M, Rodriguez LA, Lagergren J. Body mass, tobacco and alcohol and risk of esophageal, gastric cardia, and gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma among men and women in a nested case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:285–94. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-3485-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haenszel W, Correa P, Cuello C. Gastric cancer in Colombia. II. Case-control epidemiologic study of precursor lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57:1021–26. doi: 10.1093/jnci/57.5.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marugame T, Matsuda T, Kamo K, Katanoda K, Ajiki W, Sobue T. Cancer incidence andincidence rates in Japan in 2001 based on the data from 10 population-based cancer registries. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:884–91. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhyu MG, Park WS, Jung YJ, Choi SW, Meltzer SJ. Allelic deletions of MCC/APC and p53 are frequent late events in human gastric carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1584–88. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ilyas M, Tomlinson IP. The interactions of APC, E-cadherin and beta-catenin in tumour development and progression. J Pathol. 1997;182:128–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199706)182:2<128::AID-PATH839>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooks-Wilson AR, Kaurah P, Suriano G. Germline E-cadherin mutations in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: assessment of 42 new families and review of genetic screening criteria. J Med Genet. 2004;41:508–17. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.018275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998;392:402–405. doi: 10.1038/32918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson EV, Jankowski JA. Genetics of gastroesophageal cancer: paradigms, paradoxes, and prognostic utility. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:443–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oliveira C, Seruca R, Carneiro F. Genetics, pathology, and clinics of familial gastric cancer. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:21–33. doi: 10.1177/106689690601400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKie AB, Filipe MI, Lemoine NR. Abnormalities affecting the APC and MCC tumour suppressor gene loci on chromosome 5q occur frequently in gastric cancer but not in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:598–603. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trédaniel J, Boffetta P, Buiatti E, Saracci R, Hirsch A. Tobacco smoking and gastric cancer: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:565–73. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970807)72:4<565::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ladeiras-Lopes R, Pereira AK, Nogueira A. Smoking and gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:689–701. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9132-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engel LS, Chow WH, Vaughan TL. Population attributable risks of esophageal and gastric cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1404–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye W, Ekstrom AM, Hansson LE, Bergstrom R, Nyren O. Tobacco, alcohol and the risk of gastric cancer by sub-site and histologic type. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:223–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991008)83:2<223::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. The role of tobacco, snuff and alcohol use in the aetiology of cancer of the oesophagus and gastric cardia. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:340–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sjödahl K, Lu Y, Nilsen TI. Smoking and alcohol drinking in relation to risk of gastric cancer: a population-based, prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:128–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research. Washington, DC: American Institute of Cancer Research; 1997. Food, Nutrition and Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gammon MD, Schoenberg JB, Ahsan H. Tobacco, alcohol, and socioeconomic status and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1277–84. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.17.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leung WK, Lin SR, Ching JY. Factors predicting progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia: results of a randomised trial on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut. 2004;53:1244–49. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graham S, Haughey B, Marshall J. Diet in the epidemiology of gastric cancer. Nutr Cancer. 1990;13:19–34. doi: 10.1080/01635589009514042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Risch HA, Jain M, Choi NW. Dietary factors and the incidence of cancer of the stomach. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:947–59. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buiatti E, Palli D, Decarli A. A case- control study of gastric cancer and diet in Italy. Int J Cancer. 1989;44:611–16. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910440409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lunet N, Valbuena C, Carneiro F, Lopes C, Barros H. Antioxidant vitamins and risk of gastric cancer: a case-control study in Portugal. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:71–77. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5501_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ngoan LT, Mizoue T, Fujino Y, Tokui N, Yoshimura T. Dietary factors and stomach cancer mortality. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:37–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van den Brandt PA, Botterweck AA, Goldbohm RA. Salt intake, cured meat consumption, refrigerator use and stomach cancer incidence: a prospective cohort study (Netherlands) Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:427–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1024979314124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buiatti E, Palli D, Decarli A. A case-control study of gastric cancer and diet in Italy: II. Association with nutrients. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:896–901. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsugane S, Sasazuki S. Diet and the risk of gastric cancer: review of epidemiological evidence. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s10120-007-0420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merry AH, Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Body mass index, height and risk of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2007;56:1503–11. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.116665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Farrow DC, Vaughan TL, Hansten PD. Use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stalnikowicz R, Benbassat J. Risk of gastric cancer after gastric surgery for benign disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:2022–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sauvaget C, Lagarde F, Nagano J, Soda M, Koyama K, Kodama K. Lifestyle factors, radiation and gastric cancer in atomic-bomb survivors (Japan) Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:773–80. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-5385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1881–88. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kubo A, Corley DA. Meta-analysis of antioxidant intake and the risk of esophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2323–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olearchyk AS. Gastric carcinoma. A critical review of 243 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1978;70:25–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomas RL, Rice RP. Calcifying mucinous adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Radiology. 1967;878:1002–1003. doi: 10.1148/88.5.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Low VH, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Laufer I, Herlinger H. Diagnosis of gastric carcinoma: sensitivity of double-contrast barium studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:329–34. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.2.8310920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rubesin SE, Levine MS, Laufer I. Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal radiography: a pattern approach for diseases of the stomach. Radiology. 2008;246:33–48. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461061245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thompson G, Somers S, Stevenson GW. Benign gastric ulcer: a reliable radiologic diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141:331–3. doi: 10.2214/ajr.141.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levine MS, Creteur V, Kressel HY, Laufer I, Herlinger H. Benign gastric ulcers: diagnosis and follow-up with double-contrast radiography. Radiology. 1987;164:9–13. doi: 10.1148/radiology.164.1.3588932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carman RD. A new roentgen-ray sign of ulcerating gastric cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 1921;77:990–92. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van De Velde CJH. Current role of surgery and multimodal treatment in localized gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:93–98. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Arndt V. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:467–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Greene FL, Page DL, Balch CM, Fleming ID, Morrow M, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. Stomach; pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zali H, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Kariminia A, Yousefi R, Shokrgozar MA. Evaluation of Growth Inhibitory and Apoptosis Inducing Activity of Human Calprotectin on the Human Gastric Cell Line (AGS) Iranian Biomedical Journal. 2008;12:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rezaei Tavirani M, Zali H, Nasiri S, Shokrgozar MA. Human Calprotectin, a Potent Anticancer with Minimal Side Effect. IJCP. 2009;2:76–84. [Google Scholar]