Abstract

Knowledge about the clinical significance of V-Raf Murine Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog B1 (BRAF) mutations in colorectal cancer (CRC) is growing. BRAF encodes a protein kinase involved with intracellular signaling and cell division. The gene product is a downstream effector of Kirsten Ras 1(KRAS) within the RAS/RAF/MAPK cellular signaling pathway. Evidence suggests that BRAF mutations, like KRAS mutations, result in uncontrolled, non–growth factor-dependent cellular proliferation. Similar to the rationale that KRAS mutation precludes effective treatment with anti-EGFR drugs. Recently, BRAF mutation testing has been introduced into routine clinical laboratories because its significance has become clearer in terms of effect on pathogenesis of CRC, utility in differentiating sporadic CRC from Lynch syndrome (LS), prognosis, and potential for predicting patient outcome in response to targeted drug therapy. In this review we describe the impact of BRAF mutations for these aspects.

Keywords: Colorectal Cancer, BRAF mutation, Prognosis value

Molecular pathway in colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major medical and public health challenge that develops via a series of genetic and epigenetic changes. These alterations result in the transformation of normal mucosa to a premalignant polyp, and ultimately to a tumor (1–3).

At least three different molecular pathways have been postulated as main players in CRC: chromosomal instability (CIN), Microsatellite instability (MSI) and CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) (4). CIN is the most common cause of genomic instability in CRC and is responsible for approximately 65–70% of sporadic CRC (5).

CIN, or classic adenoma-to-carcinoma pathway, is characterized by an imbalance in chromosome number (aneuploidy), chromosomal genomic amplifications, and a high frequency of LOH, which has been determined through a series of mutations in tumor suppressor genes, such as APC and p53, and oncogenes, such as KRAS (6). The most common genetic alterations are mutations in APC and KRAS genes (7). A very small percentage of chromosomal instability tumors are inherited and arise secondary to germline mutations in the APC gene (familial adenomatous polyposis; less than 1% of CRCs) or the MUTYH gene (MUTYH-associated polyposis; ≤1% of CRCs) (8).

The second pathway, microsatellite instability (MSI), is observed in 15% of CRCs and also most of these tumors are sporadic, in which damaged DNA mismatch repair (MMR) enzymes contribute to acquire copy number variants in repeat sequences of microsatellites. This mechanism is identified by a test for MSI, which categorizes each tumor as MSI-high (MSI-H), MSI-low (MSI-L), or microsatellite stable, based on evaluating the size of multiple microsatellites (9).

The last pathway is characterized by epigenetic alterations, resulting in changes in gene expression or function without changing the DNA sequence of that particular gene (5). For example, methylation of CpG islands in distinct promoter sites can lead to the silencing of critical tumor suppressor genes. The resulting tumors are termed to have the CpG Island Methylator Phenotype, or CIMP (5). CIMP tumors have been closely correlated with mutations in the BRAF oncogene (4, 10–12).

Several papers have documented in serrated polyps (sessile serrated adenoma, traditional serrated adenoma, and hyperplastic polyp) a high frequency of BRAF mutations, and a low frequency of KRAS mutations, and in conventional adenomas, a low frequency of BRAF mutations and a high frequency of KRAS mutations. This observation provides further data to support the hypothesis that serrated polyps are precursor lesions of CIMP+ CRCs, which have a high frequency of BRAF mutations and a low frequency of KRAS mutations (13, 14). Mutations in the KRAS and BRAF genes may be observed in RAS/BRAF/MEK/ERK pathway (MAPK signaling) (15). Together, these observations result in a growing clinical importance of BRAF mutation in CRC patients (16). The BRAF gene is composed of 18 exons, and the major common mutation is found in exon 15 at nucleotide position 1799, accounting for more than 90% of all mutations. This thymine to adenine transversion within codon 600 leads to substitution of valine by glutamic acid at the amino acid level. The other commonly mutated are exon 11, codon 468 and exon 15, codon 596 (17). Recently, BRAF mutation testing has been utilized into routine clinical laboratories because of its beneficial operation in differentiating sporadic CRC from hereditary in MSI tumors, determination of clinical prognosis, and prediction of response to drug therapy (18).

Distinguish Lynch syndrome from sporadic CRC

Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), also called Lynch syndrome, is characterized by MSI and is the most common hereditary colon cancer, accounting for 2-6% of all colorectal cancer burden (19). Available data has provided evidence that, family history alone is unreliable for identifying HNPCC cases. So tumor screening methods such as immunohistochemistry (IHC), genetic testing for mutations and microsatellite instability (MSI) should be considered for identifying individuals with HNPCC.

There are different diagrams for evaluation of LS using MSI, IHC and genetic testing. Every approach has benefits and drawbacks and may depend on provider preferences and institutional resources. Of course each test will miss about 5-15 percent of all HNPCC cases. In this context, accumulative data show that the events leading to HNPCC is an inherited mutation of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) gene, mainly MLH1 or MSH2, which account for approximately 90% of the known mutations to date. Subsequent, mutations in MSH6 account for almost 10% of the cases and bottommost, mutations in PMS2 have been also reported in a few cases (20–22).

Microsatellites are prepared to instability when mutations are detected in MMR genes. Relative to the panel of MSI markers, 80-91% of MLH1 and MSH2 mutations and 55-77% of MSH6 and PMS2 mutations will be detected by MSI testing. However, MSI in sporadic colorectal cancer is most often associated with hypermethylation of the MLH1 gene promoter (23). The BRAF V600E mutation is often correlated with this sporadic MLH1 promoter methylation and this mutation has not been detected in tumors that arise from individuals with a germline mutation in MMR. Thus, it has been proposed that when IHC reveals absent MLH1, evaluated of BRAF mutation may avoid unnecessary further genetic testing for identifying tumors as a result of LS. BRAF mutation screening may indentify HNPCC in MSI-H tumors, although it may not be applicable in the case of PMS2 mutation carriers (24–28).

According to a study by Loughrey et al., the BRAF V600E mutation has been reported as a germline mutation in 17 of 40 (42%) tumours showing loss of MLH1 protein expression by immunohistochemistry, but only in patients with sporadic CRC. The authors recommend the incorporation of BRAF V600E mutation testing into the laboratory algorithm for pre-screening patients with suspected HNPCC, whose CRCs show loss of expression of MLH1 (28): If a BRAF V600E mutation is present, no further testing for HNPCC would be warranted. Also another study showed that detection of the BRAF V600E mutation in a colorectal MSI-H tumor rules out of the presence of a germline mutation in either the MLH1 or MSH2 gene (25). The result of this study showed that the BRAF-V600E hotspot mutation was found in 40% (82/206) of the sporadic MSI-H tumors analysed, but in none of the 111 tested HNPCC tumors. Thus screening CRC for BRAF V600E mutation is a reliable, fast, and low cost strategy that simplifies genetic testing for HNPCC (25).

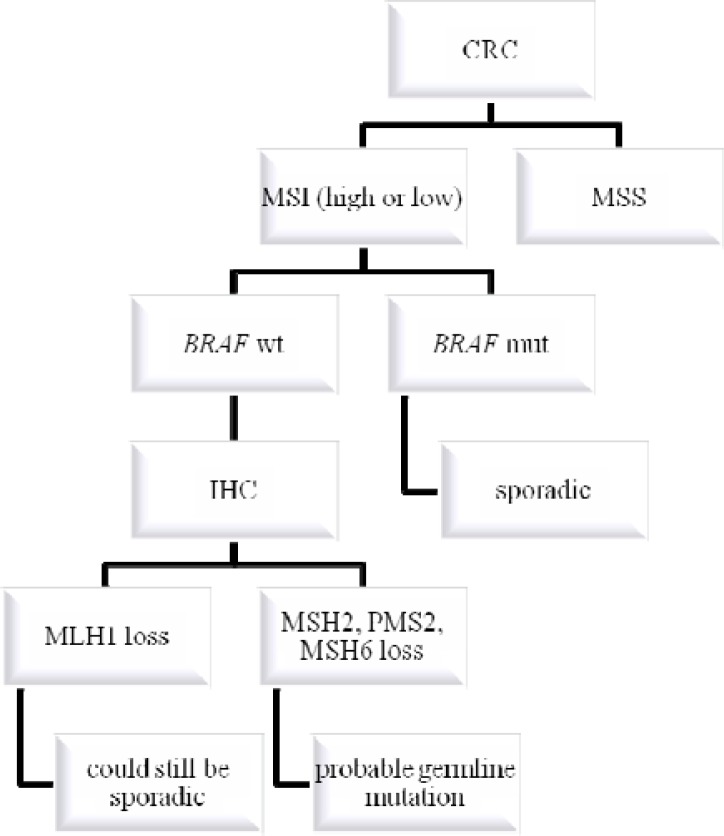

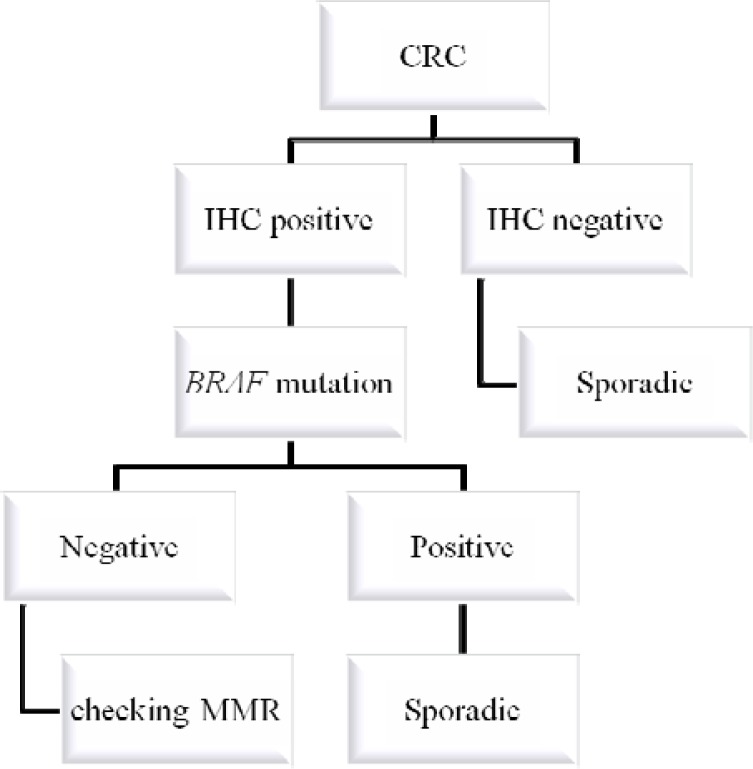

The concurrent use of MSI testing, MMR protein IHC and BRAF mutation analysis would detect almost all MMR-deficient CRC (29). A suggested algorithm incorporating somatic BRAF V600E mutation testing of tumor tissue into the investigation of suspected HNPCC is shown in Fig. 1 and in Fig. 2.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for genetic testing in colorectal cancer, following the microsatellite instability (MSI) route, when the samples are first tested for microsatellite instability, next for mutated BRAF, and finally for expression of mismatch repair enzymes by immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Figure 2.

Algorithm for genetic testing in colorectal cancer when the samples are first tested for expression of mismatch repair enzymes by immunohistochemistry (IHC), next for mutated BRAF, and finally checking MMR in full sequence

Predicting patient outcome in response to targeted drug therapy

Recently, papers demonstrated that information about BRAF mutation status, like for KRAS, is useful to help select efficacious therapy, especially when selecting systemic chemotherapy (30). In this context, many papers showed that, the patients harboring KRAS mutation do not respond to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapies, but many patients with wild type KRAS also do not respond to this therapy (4).

It has been suggested that other mutations, such as BRAF and PIK3CA, have a critical role in those cases (31). BRAF testing is suggested in CRCs that are negative for KRAS mutation when the patient is being pondered for anti-EGFR therapy. Colucci et al. in 2010 showed that the efficacy of anti-EGFR mAb is confined to patients with wild-type KRAS, whereas no mutations in any of the patients were detected in the BRAF gene (32). The efficacy of BRAF mutation on cetuximab or panitumumab response was also evaluated by cellular models of CRC (30). According to an Italian paper, 53% of the patients (110 out of 209) were considered as potentially non-responders to anti-EGFR therapy because of KRAS, BRAF or PI3K mutations (33).

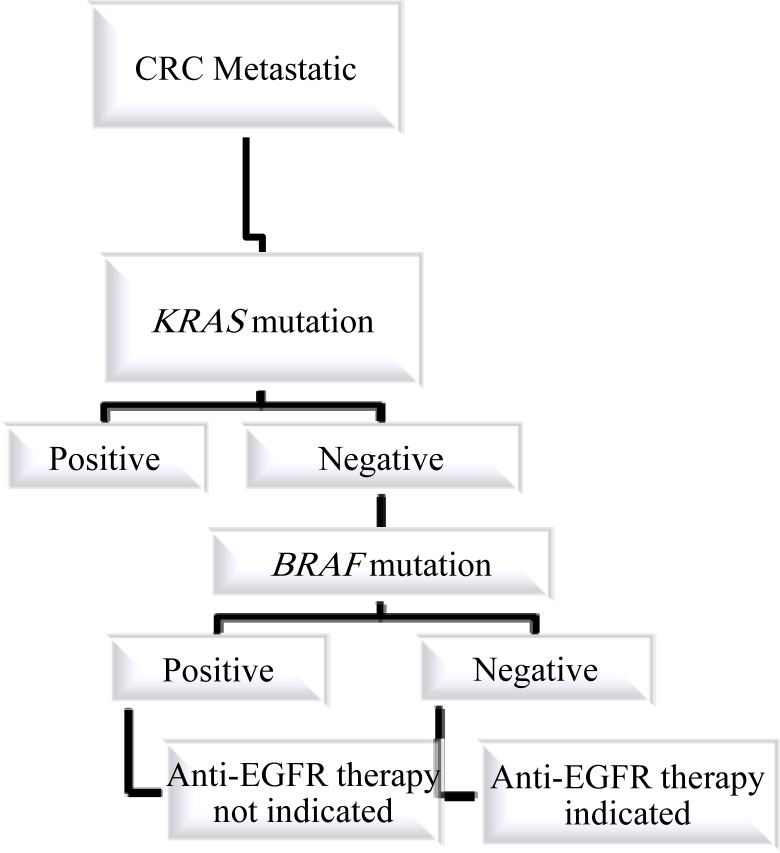

It is now recognized that anti-EGFR mAb therapy should only be used in patients whose tumors express wild-type KRAS. Furthermore, BRAF, PTEN, and PI3K are emerging as future potential predictive markers of response. However, further clinical studies are warranted to define the role of these biomarkers (34). An algorithm that includes testing for KRAS and BRAF mutation for the selection of patients for anti-EGFR therapy is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Algorithm for genetic testing in colorectal cancer when the patient is a candidate for Anti-EGFR therapy.

Predicting prognosis of CRC

The last potential use of BRAF mutation testing is for prognosis of CRC (18). In an interesting paper, Kalady et al. documented that BRAF mutation is associated with distinct clinical characteristics as mutant tumors were characterized by female sex, advanced age, proximal colon location, poor differentiation, MSI, and importantly, worse clinical prognosis for the patient (4).

They showed that BRAF mutation was independently associated with decreased overall survival. Many studies suggest that the association between BRAF mutation and CRC survival may differ by some factors. Phipps et al. documented that poor clinical prognosis associated with BRAF mutation was limited to cases diagnosed at ages <50, and in another study Samowitz et al. reported that this poor clinical outcome in CRC were microsatellite stable and not MSI-H cases (35, 36). Fariñ a-Sarasqueta et al. in 2010 reported that the V600E BRAF mutation confers a worse prognosis in stage II and stage III colon cancer patients independently of disease phase and therapy (37). In one interesting paper, Teng et al. in 2012 showed that BRAF mutation is an independent prognostic biomarker in patients with liver metastases after metastasectomy (38). Ogino et al. suggest that, the worst prognosis associated with BRAF mutation may in part be disannulled by a high CIMP status and the good prognosis associated with MSI-high status is partly weakened by a mutated BRAF status (39).

Status of KRAS and BRAF mutations in relation with CRC in Iran

There are few data on BRAF and KRAS mutation in Iran (40, 41). In one valuable study, tumor samples from 182 Iranian colorectal cancer patients (170 sporadic cases and 12 HNPCC cases) were screened for KRAS mutations at codons 12, 13 and 61 by sequencing analysis (40). KRAS mutations were observed in 68/182 (37.4%) cases, which is slightly lower as compared to the outcome of a study on an Italian population (33). Mutation frequencies were similar in HNPCC-associated, sporadic MSI-H and sporadic microsatellite-stable (MSS) tumors (40). Another study was done by Shemirani et al. and showed that probably the profile of KRAS mutations in tumors is not entirely compatible with the pattern of mutations in polyps (41). Montazer Haghighi et al. investigated 78 patients and determined with the Pentaplex Panel of mononucleotide repeats that 21 patients (26.9%) had tumors that were MSI-H, 11 patients (14.1%) were MSI-L and 46 patients (59%) were MSS. There were no statistically significant different between MSI-H, MSI-L and MSS regarding clinical features, pathology or family history of cancer in the patients (42). However, Naghibalhosseini et al. reported high frequency of genes promoter methylation, but lack of BRAF mutation among 110 unselected of sporadic patients (43). It is conclude that studies are warranted to determine the prevalence of BRAF mutation in different site of Iran to examine their impact on prognosis and response to targeted treatment. Iran is vast country and has people from various ethnic backgrounds. Therefore, we suggest to do clinical studies on the correlation between BRAF mutation and ethnic background. The results will show if the prevalence of BRAF mutations in CRC differs by ethnic background and also whether ethnic background has influence on clinical prognosis or response to drug treatment.

Summary

In terms of prognosis, an emerging body of literature describes worse clinical prognosis and decreased response to therapy for patients with BRAF mutant tumors. BRAF mutation has been reported to have a worse prognosis in MSS tumors, but there is little information regarding the effect of BRAF mutations on MSI-H tumors. In addition to prognosis, BRAF mutation could have clinical treatment implications. Similar to patients with KRAS mutations, patients with metastatic tumors that are being considered for anti-EGFR therapies should be tested for BRAF mutations as well. Because KRAS is more frequently mutated than BRAF, first-line testing should be done for KRAS. If the tumor is KRAS wild type, then genotyping BRAF should be considered. We propose studies in CRC in Iran on the clinical impact of KRAS and BRAF mutation, especially considering ethnic background.

Acknowledgements

This paper is resulted from PhD thesis of Ehsan Nazemalhosseini Mojarad student at Gastroenterology and Liver Disease Research center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

(Please cite as: Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E, Kishani Farahani R, Montazer Haghighi M, Asadzadeh Aghdaei H, Kuppen PJ, Zali MR. Clinical implications of BRAF mutation test in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2013;6(1):6-13).

References

- 1.Jass JR. Colorectal cancer: a multipathway disease. Crit Rev Oncog. 2006;12:273–87. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v12.i3-4.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007;50:113–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular origins of cancer: molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2449–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalady MF, Dejulius KL, Sanchez JA, Jarrar A, Liu X, Manilich E, et al. BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with distinct clinical characteristics and worse prognosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:128–33. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823c08b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Sohaily S, Biankin A, Leong R, Kohonen-Corish M, Warusavitarne J. Molecular pathways in colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1423–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:525–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang GH. Four molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer and their precursor lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:698–703. doi: 10.5858/2010-0523-RA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedeir A, Krasinskas AM. Molecular diagnostics of colorectal cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:578–87. doi: 10.5858/2010-0613-RAIR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Worthley DL, Whitehall VL, Spring KJ, Leggett BA. Colorectal carcinogenesis: road maps to cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3784–91. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i28.3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in cancer. Nat Rev. 2004;4:993–988. doi: 10.1038/nrc1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8681–86. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, Young J, Long TI, Faasse MA, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:787–93. doi: 10.1038/ng1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minoo P, Moyer MP, Jass JR. Role of BRAF-V600E in the serrated pathway of colorectal tumourigenesis. J Pathol. 2007;212:124–33. doi: 10.1002/path.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jass JR, Baker K, Zlobec I, Higuchi T, Barker M, Buchanan D, et al. Advanced colorectal polyps with the molecular and morphological features of serrated polyps and adenomas: concept of a ‘fusion’ pathway to colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2006;49:121–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colombino M, Sperlongano P, Izzo F, Tatangelo F, Botti G, Lombardi A, et al. BRAF and PIK3CA genes are somatically mutated in hepatocellular carcinoma among patients from South Italy. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e259. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vakiani E, Solit DB. KRAS and BRAF: drug targets and predictive biomarkers. J Pathol. 2011;223:219–29. doi: 10.1002/path.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–54. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma SG, Gulley ML. BRAF mutation testing in colorectal cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1225–28. doi: 10.5858/2009-0232-RS.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaltonen LA, Salovaara R, Kristo P, Canzian F, Hemminki A, Peltomaki P, et al. Incidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and the feasibility of molecular screening for the disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1481–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Genetic susceptibility to nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. J Med Genet. 1999;36:801–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marra G, Boland CR. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: the syndrome, the genes, and historical perspectives. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1114–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.15.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyaki M, Konishi M, Tanaka K, Kikuchi-Yanoshita R, Muraoka M, Yasuno M, et al. Germline mutation of MSH6 as the cause of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 1997;17:271–72. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domingo E, Laiho P, Ollikainen M, Pinto M, Wang L, French AJ, et al. BRAF screening as a low-cost effective strategy for simplifying HNPCC genetic testing. J Med Genet. 2004;41:664–68. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.020651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajagopalan H, Bardelli A, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE. Tumorigenesis: RAF/RAS oncogenes and mismatch-repair status. Nature. 2002;29:418–934. doi: 10.1038/418934a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domingo E, Niessen RC, Oliveira C, Alhopuro P, Moutinho C, Espín E, et al. BRAF-V600E is not involved in the colorectal tumorigenesis of HNPCC in patients with functional MLH1 and MSH2 genes. Oncogene. 2005;24:3995–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domingo E, Laiho P, Ollikainen M, Pinto M, Wang L, French AJ, et al. BRAF screening as a low-cost effective strategy for simplifying HNPCC genetic testing. J Med Genet. 2004;41:664–68. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.020651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senter L, Clendenning M, Sotamaa K, Hampel H, Green J, Potter JD, et al. The clinical phenotype of Lynch syndrome due to germ-line PMS2 mutations. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:419–28. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loughrey MB, Waring PM, Tan A, Trivett M, Kovalenko S, Beshay V, et al. Incorporation of somatic BRAF mutation testing into an algorithm for the investigation of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Fam Cancer. 2007;6:301–10. doi: 10.1007/s10689-007-9124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahner N, Friedrichs N, Steinke V, Aretz S, Friedl W, Buettner R, et al. Coexisting somatic promoter hypermethylation andpathogenic MLH1 germline mutation in Lynch syndrome. J Pathol. 2008;214:10–16. doi: 10.1002/path.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokota T. Are KRAS/BRAF mutations potent prognostic and/or predictive biomarkers in colorectal cancers? Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12:163–71. doi: 10.2174/187152012799014968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rizzo S, Bronte G, Fanale D, Corsini L, Silvestris N, Santini D, et al. Prognostic vs predictive molecularbiomarkers in colorectal cancer: is KRAS and BRAF wild type status required foranti-EGFR therapy? Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:S56–61. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(10)70021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colucci G, Giuliani F, Garufi C, Mattioli R, Manzione L, Russo A, et al. Cetuximab plus FOLFOX-4 in untreated patients with advanced colorectal cancer: a Gruppo Oncologico dell'Italia Meridionale Multicenter phase II study. Oncology. 2010;79:415–22. doi: 10.1159/000323279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bozzao C, Varvara D, Piglionica M, Bagnulo R, Forte G, Patruno M, et al. Survey of KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutational status in 209 consecutive Italian colorectal cancer patients. Int J Biol Markers. 2012;5:0. doi: 10.5301/JBM.2012.9765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouché O, Beretta GD, Alfonso PG, Geissler M. The role of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody monotherapy in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:S1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(10)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samowitz WS, Sweeney C, Herrick J, Albertsen H, Levin TR, Murtaugh MA, et al. Poor survival associated with the BRAF V600E mutation in microsatellite-stable colon cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6063–69. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, Burnett-Hartman AN, Coghill AE, Passarelli MN, et al. BRAF Mutation Status andSurvival after Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis According to Patient and TumorCharacteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1792–98. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fariña-Sarasqueta A, van Lijnschoten G, Moerland E, Creemers GJ, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, van den Brule AJ. The BRAF V600E mutation is an independent prognostic factor for survival in stage II and stage III colon cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2396–402. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teng HW, Huang YC, Lin JK, Chen WS, Lin TC, Jiang JK, et al. BRAF mutation is a prognostic biomarker for colorectal liver metastasectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:123–29. doi: 10.1002/jso.23063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, Kawasaki T, Meyerhardt JA, Loda M, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype, microsatellite instability, BRAF mutation and clinical outcome in colon cancer. Gut. 2009;58:90–96. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.155473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bishehsari F, Mahdavinia M, Malekzadeh R, Verginelli F, Catalano T, Sotoudeh M, et al. Patterns of K-ras mutation in colorectal carcinomas from Iran and Italy (a Gruppo Oncologico dell'Italia Meridionale study): influence of microsatellite instability status and country of origin. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:vii91–96. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irani Shemirani A, Montazer Haghighi M, Milanizadeh S, Taleghani MY, Fatemi R, Damavand B, et al. The role of KRAS mutations and MSI status in diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2011;4:70–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haghighi MM, Javadi GR, Parivar K, Milanizadeh S, Zali N, Fatemi SR, Zali MR. Frequent MSI mononucleotide markers for diagnosis of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1033–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naghibalhossaini F, Hosseini HM, Mokarram P, Zamani M. High frequency of genes’ promoter methylation, but lack of BRAF V600E mutation among Iranian colorectal cancer patients. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17:819–25. doi: 10.1007/s12253-011-9388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]