Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cyclosporine and infliximab are effective medical therapies for inducing remission in patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis (UC). Patients with acute, severe disease who do not respond to these therapies require colectomy, however, the risk of post-operative complications in such patients is not known. Analyzing patients with acute, severe UC, we compared the incidence of post-operative complications in patients who failed rescue therapy with cyclosporine or infliximab to that in patients who received IV corticosteroids alone.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective cohort study of UC patients who underwent colectomy after inpatient treatment with cyclosporine plus IV corticosteroids (CsA+IVS), infliximab plus IV corticosteroids (IFX+IVS), or IV corticosteroids alone (IVS) at the University of Chicago Hospitals from 10/1/2006 to 10/1/2012. Primary end-points were infectious, non-infectious, and total complications occurring within 30 days of colectomy.

RESULTS

Of 78 patients, 19 were treated with CsA+IVS, 24 with IFX+IVS, 4 with both CsA and IFX+IVS, and 31 with IVS alone. Patients treated with rescue therapy plus IVS had no difference in total post-operative complications compared to those receiving IVS alone (CsA+IVS: RR=0.63, 95% CI, 0.33–1.23; IFX+IVS: RR=0.65, 95% CI, 0.36–1.17). There remained no difference in post-operative complications between the rescue therapy and IVS alone groups when subcategorizing overall complications into infectious (CsA+IVS: RR=0.54, 95% CI, 0.17–1.76; IFX+IVS: RR=0.86, 95% CI, 0.36–2.09) and non-infectious (CsA+IVS: RR=0.88, 95% CI, 0.43–1.80; IFX+IVS: RR=0.40, 95% CI, 0.15–1.07) causes.

CONCLUSIONS

Cyclosporine and infliximab are not associated with an increased risk for post-operative complications in patients hospitalized for severe UC refractory to corticosteroids.

Keywords: biologic therapy, calcineurin inhibitor, anti-TNF alpha therapy

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 10–15% of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) experience an episode of fulminant colitis during the course of their disease.1 Though corticosteroids can induce remission during a UC flare, 27–59% of patients are refractory to steroid treatment.2–6 For such patients, colectomy traditionally was the only alternative intervention. Since the introduction of calcineurin inhibitors and anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) therapy, however, the need for emergent surgical intervention has substantially declined.7–10

Cyclosporine (CsA), a calcineurin inhibitor, was the first effective rescue therapy for corticosteroid-refractory severe UC. Demonstrated to be superior to placebo in several randomized control trials in the 1990s, it was the sole choice for medical therapy to induce remission in patients with severe, steroid-refractory UC for approximately a decade.7–8 In 2005, infliximab (IFX) was approved for use in patients with UC. Like cyclosporine, this human-murine chimeric antibody against TNF-α has an established benefit in preventing colectomy over placebo alone.9–10 Nevertheless, there remains controversy over which therapy has greater efficacy in patients hospitalized for acute, severe UC, as retrospective analyses have provided conflicting data regarding the superiority of each drug.11–13

Lacking a clear indication for drug choice based on colectomy-free outcomes alone, clinicians have resorted to alternative means in directing therapy decisions. In particular, a significant amount of attention has been placed on the adverse events associated with rescue therapy use, including complications that develop post-colectomy in patients who ultimately fail medical therapy. Several studies have investigated the incidence of such post-operative complications in patients treated with infliximab.14–24 While the majority of these studies demonstrate no difference in the short-term post-operative complication rates following treatment with infliximab versus control,14–22 others have reported increased infectious 23–24 and pouch-specific complications23 associated with infliximab. These studies, however, are limited by the inclusion of patients with a wide range of disease severity and do not control for the timing of the last infliximab infusion prior to surgery. Furthermore, while studies regarding post-operative complications in patients who receive cyclosporine are more controlled in regards to disease severity, the studies are much fewer in number and are less focused on the immediate post-operative period.25–26

Therefore, the goal of this study was to compare the incidence of post-operative complications in patients hospitalized for acute, severe UC refractory to corticosteroids who failed medical rescue therapy with either cyclosporine or infliximab to that in patients who underwent colectomy after only having received IV corticosteroids. Understanding the potential complications for patients who receive these therapies can be valuable to clinicians in their individualized approach to treatment options for this patient population.

METHODS

Subjects

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Chicago. Using ICD codes 45.7–45.83 and 556.0–556.9, we identified 978 patients with UC who underwent colectomy at the University of Chicago Hospitals from 10/1/2006 to 10/1/2012. Through a preliminary chart review, the database was limited to the following inclusion criteria: 1) a confirmed diagnosis of UC via histology and endoscopy, 2) colectomy for acute, severe UC refractory to medical therapy, 3) treatment with intravenous (IV) corticosteroids, infliximab, or cyclosporine during the hospitalization leading to colectomy. Patients who underwent an elective operation either for medically refractory UC (n = 102) or dysplasia (n = 74), as well as patients who underwent an ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) at the time of their colectomy (n = 5), were excluded from the analysis. An additional subset of patients who were discharged after receiving induction therapy with infliximab plus IV corticosteroids but urgently readmitted for colectomy were also excluded from the primary analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic outlining the process by which the eligible sample size of n=78 was reached.

Data Collection

Patients were grouped according to the medical rescue therapy used prior to colectomy and charts were reviewed retrospectively. All patients included in the study received IV corticosteroids, and those receiving IV corticosteroids alone were used as a standard for comparison (IVS). Data on patient demographics, smoking history, disease duration, Clostridium difficile and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection status, as well as the use of antimetabolites (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and methotrexate) on admission were recorded. Per review of surgical specimen pathology reports and pre-operative colonoscopy reports, we assessed for both disease extent and the presence of deep ulcers. Finally, laboratory values were recorded from the first day of admission – including hemoglobin, WBC count, platelets, albumin, and c-reactive protein (CRP). The resulting data was then evaluated to compare groups at baseline and to identify independent predictors for post-operative complications.

Both infectious and non-infectious complications following colectomy were analyzed. Consistent with previous studies on post-operative complications following infliximab therapy, analysis was focused on short-term complications occurring within 30 days of colectomy. Infectious complications included pelvic abscesses, wound infections (cellulitis, parastomal abscess), and non-specific infections (infections requiring antibiotic therapy which were not wound or intraabdominal infections such as urinary tract infections (UTI) and respiratory infections). Non-infectious complications were divided between thrombotic (deep venous thrombosis, portal vein thrombosis), re-hospitalizations (small bowel obstruction, bleeding complication, dehydration, pancreatitis), and wound failure (wound dehiscence, mucocutaneous separation).

Statistical Analysis

Each study group – CSA+IVS and IFX+IVS – was compared to the IV corticosteroids alone group to assess for differences in patient demographics and disease characteristics at baseline. Categorical variables were described as a frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were reported as a median and range or a mean and standard deviation as appropriate based on the normality of their distribution. Statistical significance was determined using either Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. All continuous variables were analyzed via the Mann-Whitney U-test or the Student’s T-test as appropriate. A p-value of <.05 was considered significant.

The association between total infectious, non-infectious, and overall postoperative complications with rescue therapy use was explored by comparing CsA+IVS versus IVS alone and IFX+IVS versus IVS alone. Results were displayed as relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

Finally, using cox regression with a constant for the time variable, a multivariable analysis was performed to identify potential confounders in the association of treatment groups and their post-operative complication outcomes. All variables listed in Table 1 were entered into the analysis; however, a backward deletion model included only those variables having an independent influence on complication outcomes at a level of p<.10.

Table 1.

Population demographics and disease characteristics at baseline

| IV Steroids (n = 31) | CsA+IVS (n = 19) | P-valuea | IFX+IVS (n = 24) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male, n (%) | 17 (55%) | 14 (74%) | .24 | 11 (46%) | .59 |

| Age, y, median [range] | 52 [18–79] | 34 [21–61] | <.01 | 41 [18–85] | .16 |

| Race, white, n (%) | 26 (84%) | 14 (74%) | .47 | 20 (83%) | >.99 |

| Smoking status, former, n (%) | 11 (36%) | 3 (16%) | .20 | 9 (38%) | >.99 |

| Disease duration, y, median [range] | 5.0 [0–49] | 2.5 [0–30] | .46 | 2.0 [0–17] | .07 |

| Disease extent, pancolitis, n (%) | 22 (71%) | 12 (63%) | .76 | 15 (63%) | .57 |

| Deep ulcers, present, n (%) | 12 (39%) | 7 (37%) | >.99 | 10 (42%) | >.99 |

| Histology, severe, n (%) | 26 (84%) | 14 (74%) | .47 | 21 (88%) | >.99 |

| Antimetabolitesc, n (%) | 9 (29%) | 11 (58%) | .07 | 6 (25%) | .77 |

| C. diff, n (%) | 6 (19%) | 3 (16%) | >.99 | 7 (29%) | .53 |

| CMV, n (%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) | b | 1 (4%) | b |

| Admission labs | |||||

| CRP, mg/L, median [range] | 38 [0–242] | 35 [0–144] | .61 | 64 [0–371] | .46 |

| Hgb, g/dL, mean ± SD | 11.9 ± 2.0 | 11.9 ± 1.9 | >.99 | 11.1 ± 1.9 | .14 |

| WBC, 103/mL, median [range] | 9.1 [3.5–22.3] | 10.3 [4.7–21.2] | .38 | 12.0 [4.1–21.6] | .08 |

| Platelets, 109/L, median [range] | 326 [108–827] | 394 [149–781] | .30 | 405 [144–821] | <.05 |

| Albumin, g/L, mean ± SD | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | .07 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | >.99 |

Chi-2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate for categorical variables; Mann-Whitney U-test or T-test for continuous variables

Number of patients with CMV infection too small to yield statistically meaningful P-value

Patients taking antimetabolite medications (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate) at time of admission

RESULTS

Population Demographics and Disease Characteristics at Baseline

A total of 78 patients were at risk for post-operative complications as defined by the inclusion criteria for this study. Of these patients, 19 (24.4%) were treated with CsA+IVS, 24 (30.8%) with IFX+IVS, 4 (5.1%) with both CsA and IFX + IVS, and 31 (39.7%) with IVS alone (Figure 1). All patients treated with cyclosporine and infliximab also received IV corticosteroids. There was no mortality observed in this study.

Based on median age of the patient population, the CsA+IVS group was younger than the IVS alone group (CsA+IVS: 34 y.o. [21–61]; IVS alone: 52 y.o. [18–79]; p <.01). Otherwise, there were no significant differences between these groups in terms of patient demographics and markers of disease severity. While the CsA+IVS group showed trends towards more males, fewer former smokers, more patients receiving antimetabolite therapy, and higher albumin level at admission, none of these differences reached statistical significance (Table 1).

The IFX+IVS group was also younger than the IVS group, though this difference was not significant (p=.16). The IFX+IVS group had increased platelets (p<.05) on their labs drawn at the time of admission compared to the IVS group. No other differences in baseline characteristics between these groups reached significance (Table 1).

Complications within 30 Days of Colectomy in Patients Receiving Cyclosporine

Patients were discharged at a mean of 6.2 days after colectomy (± 2.4 SD) in the CsA+IVS group and 9.5 (± 6.1 SD) days in the IVS alone group (p=.03). Despite there being a shorter post-operative stay in the CsA+IVS group, there were no differences between the groups in the number of patients having an infectious (RR = 0.54, 95% CI, 0.17–1.76, p=.31), non-infectious (RR = 0.88, 95% CI, 0.43–1.80, p=.72), or either complication (RR = 0.63, 95% CI, 0.33–1.23, p=.18) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Complications occurring ≤ 30 days post-colectomy

| IV Steroids (n = 31) | Relative Riska | CsA+IVS (n = 19) | Relative Risk | 95% CI | P-value | IFX+IVS (n = 24) | Relative Risk | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Discharge Dayb | 9.5 ± 6.1 | 6.2 ± 2.4 | .03 | 7.6 ± 3.6 | .18 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Infectious | 9 (29%) | 1.00 | 3 (16%) | 0.54 | 0.17–1.76 | .31 | 6 (25%) | 0.86 | 0.36–2.09 | .74 |

| Pelvic abscess | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | |||||||

| Woundd | 3 (10%) | 3 (16%) | 2 (8%) | |||||||

| Non-specifice | 4 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | |||||||

| Non-Infectiousc | 13 (42%) | 1.00 | 7 (37%) | 0.88 | 0.43–1.80 | .72 | 5 (21%) | 0.40 | 0.15–1.07 | .07 |

| Thrombosisf | 4 (13%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (8%) | |||||||

| Hospitalizationsg | 7 (23%) | 5 (26%) | 3 (13%) | |||||||

| Wound Failureh | 4 (13%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |||||||

| Totalc | 18 (58%) | 1.00 | 7 (37%) | 0.63 | 0.33–1.23 | .18 | 9 (38%) | 0.65 | 0.36–1.17 | .15 |

Reference group

Days post-colectomy, mean ± SD

Adjusted event number, n, for repeat complications in single patient

Wound infection/cellulitis, parastomal abscess

UTI, respiratory infection

DVT, portal vein thrombosis

SBO, bleeding complication, dehydration

wound dehiscence, mucocutaneous separation

Subcategorizing infectious complications, patients in the IVS alone group were found to have pelvic abscesses, wound infections, or non-specific infections at a frequency of 6%, 10%, and 13%, respectively. In contrast, 16% of patients receiving CsA+IVS developed wound infections; there were no pelvic abscesses or non-specific infections in this group (Table 2).

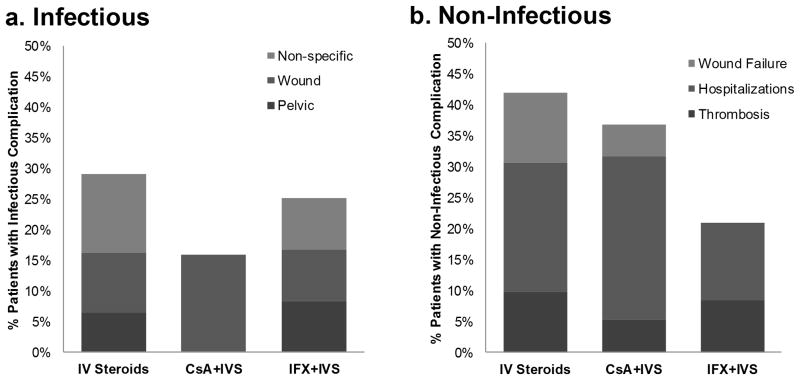

Analyzing the components of the non-infectious complications, there were fewer thrombotic and wound failure complications in the CsA+IVS group compared to the IVS group, with a 5% incidence for each in the CsA+IVS group compared to a 13% incidence for each in the IVS group (Table 2). A greater proportion of re-hospitalizations in the CsA+IVS group (Figure 2b) accounts for the similar total non-infectious complication rates observed between these two groups.

Figure 2. Relative contributions from complication subgroups.

Percentage of patients in each study group – CsA+IVS, IFX+IVS, IVS alone – having either an infectious (A) or non-infectious (B) complication. Differential shading represents the relative contribution from each complication subgroup.

Complications within 30 Days of Colectomy in Patients Receiving Infliximab

Patients receiving IFX+IVS were discharged a mean of 7.6 days after colectomy (± 3.6 SD), a length not statistically different than that of the IVS alone group (p=.18). Furthermore, there were no differences in total infectious (RR = 0.86, 95% CI, 0.36–2.09, p=.74), non-infectious (RR = 0.40, 95% CI, 0.15–1.07, p=.07) or overall (RR = 0.65, 95% CI, 0.36–1.17, p=.15) complications between the groups (Table 2).

Pelvic abscesses, wound infections, and non-specific infections each occurred at an incidence of 8% in the IFX+IVS group within 30 days of colectomy (Table 2). Given this breakdown, the relative contribution of non-specific infections to the total infectious complication rate in the IFX+IVS group was less than that of the IVS alone group (Figure 2a).

The non-infectious complications in the IFX+IVS group were thrombosis and re-hospitalizations, occurring at a rate of 8% and 13%, respectively. The lack of wound failure in this group, as well as the slightly lower incidences of both thrombosis and re-hospitalization as compared to those of the IVS alone group, account for the trend towards a total overall reduction in non-infectious post-operative complications in patients who received infliximab therapy.

Fourteen patients receiving induction therapy with IFX+IVS during an acute hospitalization were excluded from the above analysis as they were discharged after receiving their first dose of infliximab and were subsequently readmitted for urgent colectomy (Figure 1). Given that the median time between their infliximab dose and colectomy was 2 weeks (range 1–5 weeks), these patients likely had measureable infliximab serum levels in the post-operative period defined by this study. Analysis of these patients combined with the principal IFX+IVS group of this study (n = 38) also revealed no differences in the mean discharge day following colectomy (7.6 ± 3.8 SD, p=.12), total infectious complications (RR = 0.82, 95% CI, 0.37–1.80, p=.61), or overall complications (RR = 0.63, 95% CI, 0.16–1.06, p=.08) when compared to the IVS group. There was a statistically significant decrease in non-infectious complications, however, when analyzing all 38 patients who received infliximab compared to IVS alone (RR = 0.38, 95% CI, 0.16- 0.87, p=.02).

Complications within 30 Days of Colectomy in Patients Receiving Cyclosporine and Infliximab

Four patients received both cyclosporine and infliximab in addition to IV corticosteroids before going to surgery. Within the 30 days following colectomy, one patient developed a UTI. There were no other short-term infectious or non-infectious complications in these four patients.

Multivariable Analysis

Of all patient demographics and disease characteristics included in this study (Table 1), only the presence of deep ulcers independently had a significant impact on post-operative complications within 30 days following colectomy. The presence of deep ulcers on pre-operative colonoscopy reports was associated with increased total non-infectious (RR = 2.63, 95% CI, 1.30–5.29, p=.01) and overall (RR = 1.77, 95% CI, 1.18–2.66, p=.01) complications, but not with total infectious (RR = 1.08, 95% CI, 0.47–2.46, p=.86) complications.

Despite independently predicting post-operative complications, the presence of deep ulcers on a pre-operative colonoscopy, when included in the multivariable analysis, did not change the outcomes seen in the univariable analysis of post-operative complications by treatment groups. The association between infliximab rescue therapy and non-infectious post-operative complications – the association identified to have the most potential for confounding through the multivariable analysis – remained insignificant when adjusting for the potential confounding effect of deep ulcers (RR = 0.39, 95% CI, 0.13–1.18, p=.10). No other variables were selected as potential confounders through the backward deletion model of the multivariable analysis.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we show that patients hospitalized with severe UC who receive treatment with intravenous cyclosporine or infliximab along with IV corticosteroids as a rescue therapy do not have an increased risk for developing short-term post-operative complications compared to patients who receive IV corticosteroids alone. In fact, we found that patients treated with a rescue therapy in addition to IV corticosteroids trended towards an overall reduction in total post-operative complications when compared to IV corticosteroids alone, though this did not reach statistical significance. The reason for such a trend is unclear but may be related to the IV corticosteroids alone group being older as a whole. Alternatively, it is likely that our analysis failed to capture other patient-specific factors that affect the physician’s choice of medical therapy. While disease severity, as defined by deep ulcers on pre-operative colonoscopy reports, independently predicted increased non-infectious and total overall complications, this finding was present equally among the treatment groups, and as suggested by the multivariable analysis, did not confound the primary conclusions of this study.

The above evidence, suggesting there is no increased risk of total overall post-operative complications with IFX+IVS use, is consistent with several previous reports.14–23 Selvasekar et al. were the first to report this finding. Analyzing patients undergoing colectomy with an IPAA from 2002–2005, they found no difference in the overall postoperative complication rates between infliximab-treated patients and controls.23 While their sub-group analysis did reveal increased anastomotic leaks, pouch-specific complications, and infectious complications in the infliximab group, the off-label (pre-FDA approval) use of infliximab at the time, in addition to the wide range of disease severity included in the study, raises the question of whether infliximab treatment was an indirect marker for more severe disease.14,23 Though many subsequent studies have yielded comparable results to our analysis in regards to infectious and overall complications following infliximab therapy, they too have been limited by the inclusion of patients treated with infliximab prior to its FDA approval and by the variability of disease severity.14–22

In the present study, we aimed to minimize the potential for drug therapy to act as an indirect marker of disease severity by including only patients hospitalized for acute, severe UC refractory to corticosteroids in the post-FDA approval era. As a consequence, therapy choice was less skewed towards the severity of the patients’ disease. Furthermore, it provided a more uniform time from rescue therapy administration to colectomy, as thestudy groups received their respective infusions during the hospitalization in which colectomy was performed. Compared to the 12 week window described in previous studies, this study design increases the probability of having measurable serum rescue therapy levels at the time of colectomy and into the early post-operative period. Finally, the focused patient population provided less variation among the types of operations performed. Due to the acuity of the patients’ disease, all patients underwent a 3-stage procedure with a delayed IPAA, minimizing influences intrinsic to the procedure itself.

Despite these findings, the current study remains limited in that it is a retrospective, single center analysis. The small sample size limits the power of the study and may have prevented the detection of some differences among study groups and inhibited our ability to identify independent clinical predictors of post-operative morbidity through the multivariable analysis. This limitation is evident in our sub analysis of patients discharged after rescue therapy with IFX+IVS but urgently readmitted for colectomy. When combined with the primary IFX+IVS group, the relative risk for non-infectious post-operative complications remained unchanged, yet the reduction in these post-operative complications was statistically significant. While this may be a valid observation given that the subgroup received IFX+IVS rescue therapy a median of two weeks prior to colectomy and likely had measurable serum drug levels throughout the early post-operative period, we cannot exclude the possibility that these patients had an underlying difference from the primary group allowing them to be discharged. Finally, because the study was performed in a tertiary referral center, it is also possible that the study may have been impacted by loss of long-term follow-up and may not be generalizable to all UC patients who undergo colectomy after failing rescue therapy.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that patients hospitalized for acute, severe UC refractory to corticosteroids are not at increased risk for post-operative infectious or non-infectious complications following rescue therapy with cyclosporine or infliximab when undergoing a colectomy. With the controversy surrounding cyclosporine or infliximab superiority in regards to colectomy-free outcomes in this patient population, this finding, in addition to other clinical predictors of outcomes (e.g. vital signs, laboratory values, endoscopic assessments, serotypes, genotypes, etc.) 27–30 is important in tailoring an individualized treatment approach.

Acknowledgments

SOURCE OF FUNDING: Dr. David Rubin is a consultant for Janssen and receives grant support (TREAT registry). The present manuscript was funded in part by the following grants: P30DK42086 (Digestive Diseases Research Core Center) and K08DK090152 (J.P.).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

For the remaining authors, none were declared.

References

- 1.Edwards FC, Truelove SC. The course and prognosis of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1963;4:299–315. doi: 10.1136/gut.4.4.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Truelove SC, Witts L. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis. British Medical Journal. 1955;2:1041–1048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4947.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goligher JC, Hoffman DC, Dombal F. Surgical treatment of severe attacks of ulcerative colitis, with special reference to the advantages of early operation. British Medical Journal. 1970;4:703–706. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5737.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truelove S, Jewell D. Intensive intravenous regimen for severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. The Lancet. 1974;1:1067–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Järnerot G, Rolny P, Sandberg-Gertzén H. Intensive intravenous treatment of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustavsson A, Halfvarson J, Magnuson A, et al. Long-term colectomy rate after intensive intravenous corticosteroid therapy for ulcerative colitis prior to the immunosuppressive treatment era. Am J Gasteroenterol. 2007;102:2513–2519. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtiger S, Present D. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Haens G, Lemmens L, Geboes K, et al. Intravenous cyclosporine versus intravenous corticosteroids as single therapy for severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1323–1329. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sands B, Tremaine W, Sandborn W, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of severe, steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2001;7:83–88. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Järnerot G, Hertervig E, Friis-Liby I, et al. Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1805–1811. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sjöberg M, Walch A, Meshkat M, et al. Infliximab or cyclosporine as rescue therapy in hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a retrospective observational study. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2012;18:212–218. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean KE, Hikaka J, Huakau JT, et al. Infliximab or cyclosporine for acute severe ulcerative colitis: a retrospective analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;27:487–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mocciaro F, Renna S, Orlando A, et al. Cyclosporine or infliximab as rescue therapy in severe refractory ulcerative colitis: early and long-term data from a retrospective observational study. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2012;6:681–686. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali T, Yun L, Rubin DT. Risk of post-operative complications associated with anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;18:197–204. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schluender S, Ippoliti A, Dubinsky M, et al. Does infliximab influence surgical morbidity of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis? Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1747–1753. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrante M, D’Hoore A, Vermeire S, et al. Corticosteroids but not infliximab increase short-term postoperative infectious complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2009;15:1062–1070. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Z, Wu Q, Wu K, et al. Meta-analysis: pre-operative infliximab treatment and short-term post-operative complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:486–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gainsbury M, Chu D, Howard L, et al. Preoperative infliximab is not associated with an increased risk of short-term postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2011;15:397–403. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nørgård BM, Nielsen J, Qvist N, et al. Pre-operative use of anti-TNF-α agents and the risk of post-operative complications in patients with ulcerative colitis - a nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1301–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bregnbak D, Mortensen C, Bendtsen F. Infliximab and complications after colectomy in patients with ulcerative colitis. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2012;6:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eshuis E, Al Saady R, Stokkers P, et al. Previous infliximab therapy and postoperative complications after proctocolectomy with ileum pouch anal anastomosis. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2013;7:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waterman M, Xu W, Dinani A, et al. Preoperative biological therapy and short-term outcomes of abdominal surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62:387–394. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selvasekar CR, Cima RR, Larson DW, et al. Effect of infliximab on short-term complications in patients undergoing operation for chronic ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:956–962. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mor I, Vogel J, da Luz Moreira A, et al. Infliximab in ulcerative colitis is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1202–1207. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyde GM, Jewell DP, Kettlewell MG, et al. Cycosporin for severe ulcerative colitis does not increase the rate of perioperative complications. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1436–1440. doi: 10.1007/BF02234594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Randall J, Singh B, Warren BF, et al. Delayed surgery for acute severe ulcerative colitis is associated with increased risk of postoperative complications. Br J Surg. 2010;97:404–409. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Katsanos KH, et al. Predictors of early response to infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2007;13:123–128. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cacheux W, Seksik P, Lemann M, et al. Predictive factors of response to cyclosporine in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:637–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jürgens M, Laubender RP, Hartl F, et al. Disease activity, ANCA, and IL23R genotype status determine early response to infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1811–1819. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oussalah A, Evesque L, Laharie D, et al. A multicenter experience with infliximab for ulcerative colitis: outcomes and predictors of response, optimization, colectomy, and hospitalization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2617–2625. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]