Abstract

BACKGROUND

Although the increased prevalence of childhood obesity in the United States has been documented, little is known about its incidence. We report here on the national incidence of obesity among elementary-school children.

METHODS

We evaluated data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999, a representative prospective cohort of 7738 participants who were in kindergarten in 1998 in the United States. Weight and height were measured seven times between 1998 and 2007. Of the 7738 participants, 6807 were not obese at baseline; these participants were followed for 50,396 person-years. We used standard thresholds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to define “overweight” and “obese” categories. We estimated the annual incidence of obesity, the cumulative incidence over 9 years, and the incidence density (cases per person-years) overall and according to sex, socioeconomic status, race or ethnic group, birth weight, and kindergarten weight.

RESULTS

When the children entered kindergarten (mean age, 5.6 years), 12.4% were obese and another 14.9% were overweight; in eighth grade (mean age, 14.1 years), 20.8% were obese and 17.0% were overweight. The annual incidence of obesity decreased from 5.4% during kindergarten to 1.7% between fifth and eighth grade. Overweight 5-year-olds were four times as likely as normal-weight children to become obese (9-year cumulative incidence, 31.8% vs. 7.9%), with rates of 91.5 versus 17.2 per 1000 person-years. Among children who became obese between the ages of 5 and 14 years, nearly half had been overweight and 75% had been above the 70th percentile for body-mass index at baseline.

CONCLUSIONS

Incident obesity between the ages of 5 and 14 years was more likely to have occurred at younger ages, primarily among children who had entered kindergarten overweight.

Childhood obesity is a major health problem in the United States.1 The prevalence of a body-mass index (BMI; the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) at the 95th percentile or higher among children between the ages of 6 and 11 years increased from 4.2% in 1963–1965 to 15.3% in 1999–20002,3 and may have plateaued during the first decade of the 21st century.4,5 Although trends in the prevalence of obesity are documented, surprisingly little is known about the incidence of childhood obesity. Examining incidence may provide insights into the nature of the epidemic, the critically vulnerable ages, and the groups at greatest risk for obesity.

National data on the incidence of pediatric obesity to date have pertained only to adolescents transitioning to adulthood. A study that was based on data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health showed that the 5-year cumulative incidence of obesity among persons who were 13 to 20 years of age in 1996 and 19 to 26 years of age in 2001 was 12.7%, ranging from 6.5% among Asian girls to 18.4% among non-Hispanic black girls.6 However, since many of the processes leading to obesity start early in life,7 data with respect to incidence before adolescence are needed.

We report here the incidence of obesity according to data from a large, nationally representative longitudinal study of children who were followed from entry into kindergarten to the end of eighth grade (ages 5 to 14 years); the study included direct anthropometric measurements at seven points between 1998 and 2007.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

We analyzed data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999, which was designed and conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) of the Department of Education. The NCES selected a nationally representative cohort using multistage probability sampling, in which the primary sampling units were counties or groups of counties, the second-stage units were schools within the sampled units, and the third-stage units were students within schools.8 The study enrolled 21,260 children who were starting kindergarten in the fall semester of 1998 (mean age, 5.6 years) and followed 9358 children through sequential phases of data collection, in 1999 (spring semester of kindergarten; mean age, 6.1 years), 2000 (first grade; mean age, 7.1 years), 2002 (third grade; mean age, 9.1 years), 2004 (fifth grade; mean age, 11.1 years), and 2007 (eighth grade; mean age, 14.1 years). The NCES also collected data from a representative subsample of one third of the children in 1999 (mean age, 6.6 years; fall semester of first grade). With appropriate survey adjustments, this longitudinal sample is representative of all children enrolled in kindergarten in 1998 and 1999 in the United States (approximately 3.8 million children).

The survey included extensive data collection from caregivers, school staff, teachers, and children, along with direct measurements, as described previously.8 Trained assessors measured children’s height in inches (to the nearest 0.25 in.) with the use of a Shorr board and recorded weight in pounds with the use of a digital scale. For this analysis, in order to track the incidence of obesity, we selected variables — height, weight, and parent-reported age, sex, race or ethnic group, socioeconomic status, and birth weight — from among the variables in the restricted-use data set for children from kindergarten through eighth grade. The analytic sample consists of the 7738 children with data on these variables across phases of data collection.

EVALUATION OF DATA

We used the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Growth Charts to calculate each child’s BMI, standardized to the reference population for the child’s age and sex.9 We determined cutoffs for normal weight, overweight, and obesity using the CDC’s standard thresholds of the 85th percentile for overweight and 95th percentile for obesity. The use of alternative specifications with cutoffs set by the Child Obesity Working Group of the International Obesity Task Force10 showed consistent results.

We calculated the prevalence of obesity as the proportion of all children in each age group who were obese. Incidence was defined as the occurrence of a new case of obesity in a child who was not previously obese. We calculated the incidence of obesity on the basis of the follow-up data for 6807 children who were not already obese in kindergarten and thus were at risk for incident obesity. We also calculated incidence proportions by dividing the number of newly obese children by the number of children at risk during the follow-up period. Because the intervals between the study phases varied, we calculated the annual incidence by dividing the incidence by the length of the interval between the study phases in years. Cumulative incidence shows the 9-year risk of obesity.

In prespecified alternative analyses, we calculated incidence density rates, which better account for the unequal intervals between study phases and nonconstant incidence according to age. We divided the number of new obesity cases by the number of person-years of follow-up, which was expressed as a rate per 1000 person-years. We measured person-years at risk using age in months, beginning at baseline and continuing either to the midpoint between the last study phase in which the child was not obese and the study phase in which incident obesity was noted or to the end of follow-up in eighth grade — whichever occurred first.11

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To assess the incidence of obesity in the major population groups, we stratified the estimates of prevalence and incidence according to sex, quintile of the kindergartners’ household socioeconomic status, and race or ethnic group (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or “other”). To understand the importance of weight early in life, we also stratified the data according to birth weight (<2500 g, 2500 to 3999 g, and ≥4000 g) and baseline weight in kindergarten (normal weight vs. overweight but not obese). To compare the risk of obesity between normal-weight and overweight children, we calculated risk ratios for the incidence of obesity in overweight kindergartners divided by the incidence in normal-weight kindergartners. Finally, we used logistic regression to determine clinically relevant predictive risks by calculating the marginal predicted probabilities of being obese in eighth grade as a function of the percentile of BMI and z score at younger ages.

We used variance estimates for constructing 95% confidence intervals with Taylor series linearization to account for the complex sample design.12 We used longitudinal weights and survey adjustments constructed by the National Center for Education Statistics to make nationally representative inferences. All analyses were performed with the use of SUDAAN software, version 10.1 (Research Triangle Institute).

RESULTS

PREVALENCE OF OBESITY

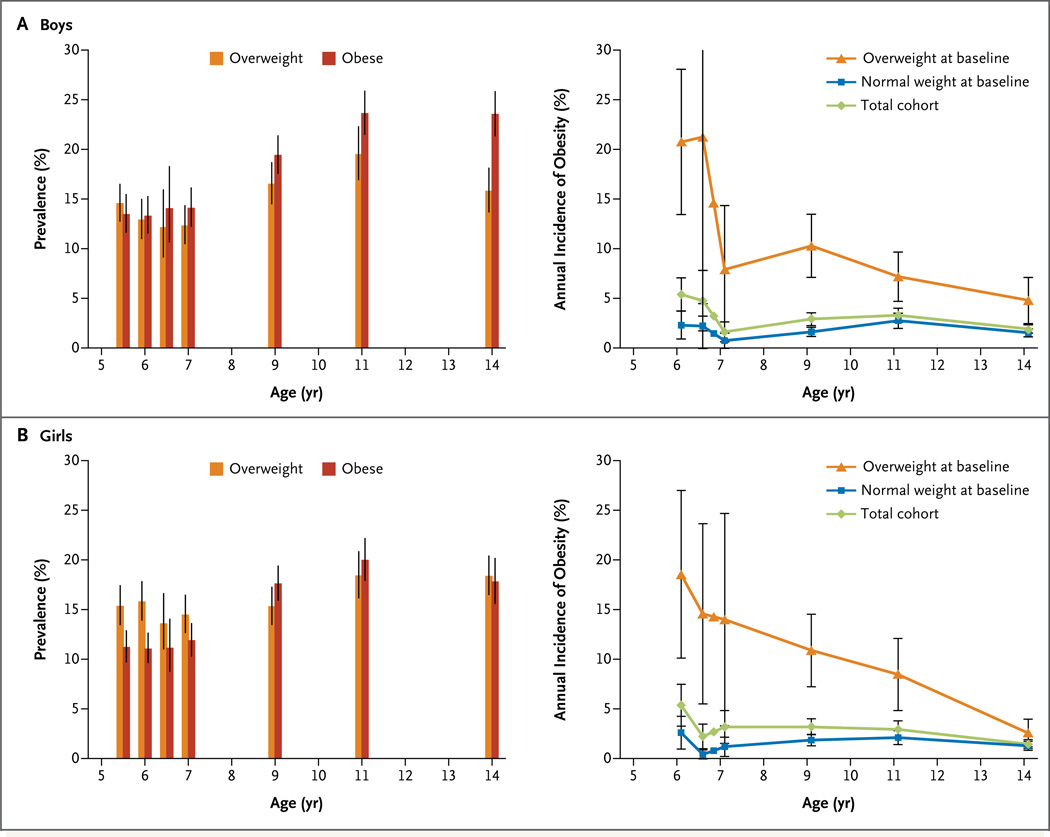

When children were entering kindergarten, at a mean age of 5.6 years, 14.9% were overweight (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org), and 12.4% were obese (Table 1 and Fig. 1A and 1B, left panels). The prevalence of obesity increased at subsequent ages, reaching 20.8% by eighth grade (mean age, 14.1 years). There were no significant increases in prevalence between the ages of 11 and 14 years.

Table 1.

National Prevalence of Obesity among Children between the Ages of 5 and 14 Years (1998–2007).*

| Variable | No. of Children |

Prevalence of Obesity (95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kindergarten, Fall Semester: Mean Age, 5.6 Yr |

Kindergarten, Spring Semester: Mean Age, 6.1 Yr |

First Grade, Fall Semester: Mean Age, 6.6 Yr† |

First Grade, Spring Semester: Mean Age, 7.1 Yr |

Third Grade, Fall Semester: Mean Age, 9.1 Yr |

Fifth Grade, Spring Semester: Mean Age, 11.1 Yr |

Eighth Grade, Fall Semester: Mean Age, 14.1 Yr |

||

| All children | 7738 | 12.4 (11.2–13.7) | 12.2 (11.0–13.5) | 12.6 (10.4–15.1) | 13.0 (11.9–14.3) | 18.6 (17.3–19.9) | 21.9 (20.4–23.4) | 20.8 (19.1–22.5) |

| Boys | 3865 | 13.4 (11.6–15.5) | 13.3 (11.5–15.3) | 14.1 (10.6–18.3) | 14.1 (12.2–16.2) | 19.4 (17.6–21.4) | 23.6 (21.5–25.9) | 23.5 (21.3–25.9) |

| Girls | 3873 | 11.2 (9.7–12.9) | 11.0 (9.6–12.7) | 11.1 (8.7–14.1) | 11.9 (10.3–13.7) | 17.6 (15.9–19.5) | 20.0 (17.9–22.2) | 17.8 (15.6–20.2) |

| Socioeconomic quintile‡ | ||||||||

| 1 | 1025 | 13.8 (11.5–16.5) | 12.6 (10.5–15.1) | 15.6 (10.8–21.9) | 14.7 (12.1–17.7) | 20.1 (17.4–23.0) | 25.2 (21.8–28.9) | 24.1 (19.9–28.9) |

| 2 | 1278 | 16.5 (12.8–21.0) | 17.4 (14.1–21.3) | 18.1 (12.6–25.4) | 15.7 (12.5–19.6) | 23.5 (20.0–27.3) | 25.5 (21.8–29.7) | 25.8 (21.4–30.6) |

| 3 | 1484 | 12.0 (9.3–15.3) | 13.4 (10.5–16.9) | 12.3 (8.1–18.2) | 16.2 (13.0–20.0) | 20.7 (17.6–24.3) | 25.7 (22.2–29.5) | 24.2 (20.5–28.3) |

| 4 | 1594 | 12.2 (9.3–15.8) | 11.5 (8.8–15.0) | 12.8 (8.6–18.5) | 11.4 (8.9–14.5) | 17.8 (14.5–21.6) | 20.9 (17.4–24.9) | 20.5 (16.8–24.8) |

| 5 | 2047 | 7.4 (5.6–9.7) | 6.6 (5.0–8.6) | 5.2 (3.2–8.4) | 7.0 (5.4–9.1) | 10.8 (8.8–13.3) | 12.3 (10.2–14.9) | 11.4 (9.1–14.2) |

| Race or ethnic group§ | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 4822 | 10.3 (8.9–12.0) | 9.3 (7.9–11.0) | 9.7 (7.1–13.3) | 10.6 (9.2–12.3) | 14.6 (13.1–16.2) | 17.9 (16.2–19.8) | 17.0 (15.3–18.9) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 762 | 12.5 (9.4–16.6) | 13.7 (10.4–17.9) | 14.4 (9.3–21.5) | 14.0 (10.7–18.1) | 22.3 (17.9–27.4) | 26.8 (22.0–32.1) | 27.1 (21.4–33.7) |

| Hispanic | 1301 | 17.8 (15.0–20.9) | 18.8 (15.7–22.4) | 19.5 (14.3–26.0) | 18.6 (15.6–22.0) | 27.2 (23.7–30.9) | 29.2 (25.3–33.5) | 26.6 (23.1–30.5) |

| Other | 853 | 14.5 (10.6–19.5) | 15.3 (11.4–20.2) | 13.2 (8.2–20.7) | 16.1 (11.8–21.5) | 19.5 (15.2–24.8) | 23.0 (17.8–29.1) | 20.8 (15.3–27.7) |

| Birth weight¶ | ||||||||

| <2500 g | 711 | 9.3 (6.1–14.0) | 10.4 (7.0–15.1) | 9.8 (5.5–16.8) | 12.4 (9.4–16.2) | 15.2 (11.3–20.2) | 19.0 (14.8–24.2) | 19.5 (15.2–24.7) |

| 2500–3999 g | 6035 | 11.2 (10.0–12.5) | 11.1 (10.0–12.4) | 12.0 (9.9–14.5) | 11.8 (10.5–13.3) | 17.8 (16.4–19.3) | 20.9 (19.2–22.8) | 19.4 (17.7–21.2) |

| ≥4000 g | 915 | 22.5 (18.1–27.5) | 21.1 (16.3–26.8) | 21.7 (13.5–33.1) | 21.3 (17.0–26.4) | 26.3 (21.7–31.4) | 30.9 (25.5–36.8) | 31.2 (25.8–37.2) |

Data are from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999.8 CI denotes confidence interval.

The fall semester of first grade was a random subsample of the entire cohort consisting of 2277 children.

Quintiles range from the lowest fifth (1) to the highest fifth (5). Data on socioeconomic status were missing for 310 children, so the numbers in the subcategories do not total 7738.

Race or ethnic group was reported by parents of the children or collected from school records. The category designated as “other” includes Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, and multiracial background.

Data on birth weight were missing for 77 children, so the numbers in the subcategories do not total 7738.

Figure 1. Prevalence and Incidence of Obesity between Kindergarten and Eighth Grade.

Shown are the age-specific prevalence of overweight and obesity (left graph on each panel) and annual incidence of obesity according to the weight status at baseline (right graph on each panel) among boys (Panel A) and girls (Panel B). The black vertical lines and I bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

The prevalence of obesity was higher among Hispanic children than among non-Hispanic white children at all ages (Table 1). Starting in third grade, non-Hispanic black children also had a significantly higher prevalence of obesity than non-Hispanic white children. Among all children during the follow-up period, the greatest increase in the prevalence of obesity was between first and third grades, when the prevalence increased from 13.0% to 18.6%. Between kindergarten and eighth grade, the prevalence of obesity increased by 65% among non-Hispanic white children, 50% among Hispanic children, nearly 120% among non-Hispanic black children, and more than 40% among children of other races (Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, and multiracial children).

Children from the wealthiest 20% of families had a lower prevalence of obesity in kindergarten than did those in all the other socioeconomic quintiles (7.4%, vs. 13.8% and 16.5% among children in the two poorest quintiles, respectively); these differences increased through eighth grade. At all ages, the prevalence of obesity was highest among children in the next-to-poorest quintile, reaching 25.8% by eighth grade.

There were no significant differences in the prevalence of obesity between kindergartners with a low birth weight (<2500 g) and those with an average birth weight (2500 to 3999 g) (9.3% and 11.2%, respectively), but there was a significantly higher prevalence at all ages among children who had a high birth weight (≥4000 g) than among children in the other two birth-weight groups.

INCIDENCE OF OBESITY

Although the prevalence of obesity increased with age, incident obesity was highest at the youngest ages and declined through eighth grade. The annual incidence of obesity among kindergartners from fall to spring was 5.4% but fell to 1.9% (among boys) and 1.4% (among girls) per year during the period between fifth grade and eighth grade (Fig. 1A and 1B, right panels, and Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Between the ages of 5 and 14 years, 11.9% of children became obese (10.1% of girls and 13.7% of boys) (Table 2). By eighth grade, 16.8% of non-Hispanic black children became obese, as did 10.1% of non-Hispanic white children and children of other races or ethnic groups and 14.3% of Hispanic children. The lowest cumulative incidence of obesity according to socioeconomic status was among children from the wealthiest 20% of families (7.4%), and the highest was among children from the middle socioeconomic quintile (15.4%).

Table 2.

Cumulative Incidence of Obesity from Kindergarten through Eighth Grade, According to Weight in Kindergarten, and Risk Ratios for Overweight versus Normal Weight Children.*

| Variable | Not Obese at Baseline (N = 6807) |

Normal Weight at Baseline (N = 5675) |

Overweight at Baseline (N = 1132) |

Risk Ratio for Overweight vs. Normal Weight (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) |

P Value | Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) |

P Value | Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) |

P Value | ||

| % | % | % | |||||

| All children | 11.9 (10.6–13.3) | 7.9 (6.7–9.0) | 31.8 (26.9–36.7) | 4.04 (3.29–4.96) | |||

| Boys | 13.7 (11.9–15.5) | Reference | 9.1 (7.5–10.6) | Reference | 36.6 (29.7–43.4) | Reference | 4.03 (3.14–5.18) |

| Girls | 10.1 (8.2–12.0) | 0.006 | 6.6 (4.9–8.3) | 0.03 | 26.9 (20.3–33.4) | 0.04 | 4.07 (2.94–5.65) |

| Socioeconomic quintile | |||||||

| 1 | 13.7 (10.0–17.4) | 0.004 | 9.3 (5.9–12.6) | 0.02 | 31.6 (21.4–41.9) | 0.34 | 3.41 (2.11–5.50) |

| 2 | 13.7 (10.1–17.3) | 0.006 | 9.9 (6.4–13.3) | 0.03 | 31.7 (19.6–43.8) | 0.37 | 3.21 (1.93–5.34) |

| 3 | 15.4 (12.2–18.6) | <0.001 | 10.0 (6.8–13.3) | 0.005 | 38.3 (29.8–46.8) | 0.04 | 3.82 (2.59–5.63) |

| 4 | 11.5 (8.1–14.8) | 0.04 | 6.8 (4.0–9.7) | 0.24 | 34.3 (21.0–47.6) | 0.22 | 5.02 (2.85–8.83) |

| 5 | 7.4 (5.2–9.6) | Reference | 4.9 (3.0–6.8) | Reference | 24.3 (13.7–34.8) | Reference | 4.99 (2.77–8.99) |

| Racial or ethnic group | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 10.1 (8.5–11.6) | Reference | 6.7 (5.4–7.9) | Reference | 29.0 (22.3–35.7) | Reference | 4.35 (3.21–5.89) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 16.8 (12.1–21.6) | 0.01 | 10.2 (6.1–14.3) | 0.11 | 44.0 (30.0–58.0) | 0.07 | 4.32 (2.61–7.13) |

| Hispanic | 14.3 (11.5–17.1) | 0.01 | 10.5 (7.5–13.4) | 0.02 | 28.9 (21.6–36.2) | 0.97 | 2.76 (1.93–3.94) |

| Other | 10.1 (5.7–14.5) | 0.97 | 6.6 (2.8–10.5) | 0.98 | 27.0 (11.1–42.8) | 0.81 | 4.07 (1.84–9.02) |

| Birth weight | |||||||

| <2500 g | 10.7 (7.9–13.5) | 0.56 | 8.6 (5.8–11.3) | 0.58 | 25.8 (10.8–40.8) | 0.54 | 3.40 (1.66–6.95) |

| 2500–3999 g | 11.6 (10.1–13.1) | Reference | 7.7 (6.5–9.0) | Reference | 30.7 (25.3–36.2) | Reference | 3.97 (3.10–5.09) |

| ≥4000 g | 16.4 (11.3–21.4) | 0.07 | 8.1 (4.4–11.8) | 0.86 | 41.2 (28.0–54.4) | 0.14 | 5.11 (2.92–8.94) |

Data are from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999.8

Incidence density rates were consistent with cumulative incidence, with a rate of 26.5 per 1000 person-years between the ages of 5 and 14 years (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). The magnitude of differences between groups varied slightly according to the incidence measure used, probably because incidence is not constant through time, as the incidence proportion method assumes.

INCIDENCE OF OBESITY ACCORDING TO WEIGHT IN KINDERGARTEN

A total of 45.3% of incident obesity cases between kindergarten and eighth grade occurred among the 14.9% of children who were overweight when they entered kindergarten (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). The annual incidence of obesity during kindergarten among these children was 19.7%, as compared with 2.4% among children who entered kindergarten with normal weight (Fig. 1A and 1B, right panels, and Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Consistent with these data, incidence density rates were 91.5 vs. 17.2 per 1000 person-years for overweight and normal-weight kindergartners, respectively (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

The high incidence of obesity among children who were overweight in kindergarten fell with increasing age, so that between the ages of 11 and 14 years, the annual incidence was 3.7% (4.8% for boys and 2.6% for girls) (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). A total of 31.8% of the children who were overweight at kindergarten entry had become obese by the age of 14 years, as compared with 7.9% of their normal-weight kindergarten classmates (Table 2). Even among kindergartners from families with the highest socioeconomic status, the incidence was much higher among those who had been overweight rather than normal weight in kindergarten. There were no significant differences in incidence among children of various races or ethnic groups who were already overweight in kindergarten.

Overweight kindergartners had four times the risk of becoming obese by the age of 14 years as normal-weight kindergartners (Table 2). The relative risks of obesity among overweight kindergartners, as compared with normal-weight kindergartners, were highest among children from the two highest socioeconomic groups. Thus, overweight children from the two highest socioeconomic groups had five times the risk of becoming obese as normal-weight children of similar socioeconomic status, whereas an overweight child from the lowest socioeconomic group had only 3.4 times the risk of obesity as a normal-weight child of similar socioeconomic status. Non-Hispanic white and black kindergartners who were overweight had higher incidences of obesity (by factors of 4.4 and 4.3, respectively) than did normal-weight children; among Hispanic children, the incidence was higher by a among children who had a birth weight of more than 4000 g and had become overweight by the age of 5 years. These children were 5.1 times as likely to become obese during the subsequent 9 years as were children with the same high birth weight whose growth trajectories led to a normal weight at the age of 5 years.

QUANTIFYING WEIGHT TRAJECTORIES

Children at the 50th percentile of body-mass index at the age of 5 years had a 6% probability of being obese at the age of 14 years (Table 3). This probability increased to 25% among 5-year-olds at the 85th percentile and to 47% among those at the 95th percentile. Among children who were at the 99th percentile in kindergarten, 72% could expect to still be obese as they finished eighth grade.

Table 3.

Probability of Obesity in Eighth Grade, Spring Semester (Mean Age, 14.1 Years), According to z Score and Percentile of Body-Mass Index at Earlier Ages.*

| Weight Category and z Score |

Percentile of Body-Mass Index |

Probability of Obesity in Eighth Grade, Spring Semester | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kindergarten, Fall Semester: Mean Age, 5.6 Yr |

Kindergarten, Spring Semester: Mean Age, 6.1 Yr |

First Grade, Fall Semester: Mean Age, 6.6 Yr |

First Grade, Spring Semester: Mean Age 7.1 Yr |

Third Grade, Spring Semester: Mean Age, 9.1 Yr |

Fifth Grade, Spring Semester: Mean Age, 11.1 Yr |

||

| percent | |||||||

| Normal weight | |||||||

| 0.00 | 50 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | <1 |

| 0.25 | 60 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| 0.52 | 70 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 1 |

| 0.84 | 80 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 11 | 4 |

| Overweight | |||||||

| 1.04 | 85 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 16 | 7 |

| 1.28 | 90 | 33 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 25 | 16 |

| Obese | |||||||

| 1.64 | 95 | 47 | 49 | 48 | 48 | 44 | 39 |

| 2.33 | 99 | 72 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 80 | 87 |

Data are from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999.8

DISCUSSION

The incidence of obesity between the ages of 5 and 14 years was 4 times as high among children who had been overweight at the age of 5 years as among children who had a normal weight at that age. Consequently, 45% of incident obesity between the ages of 5 and 14 years (kindergarten and eighth grade) occurred among the 14.9% of children who were overweight (85th to 95th percentile for age- and sex-specific BMI) at the age of 5 years. Furthermore, 87% of obese eighth graders had had a BMI above the 50th percentile in kindergarten, and 75% had been above the 70th percentile; only 13% of children who were normal weight in eighth grade had been overweight in kindergarten.

The annualized incidence of obesity was fairly constant among normal-weight kindergartners but fell with increasing age from high levels among children who were overweight at kindergarten entry. The results are consistent with incident obesity occurring largely among the minority of children who become overweight at young ages, with incidence tapering off as this susceptible pool is exhausted.

Our estimates are consistent with nationally representative data, which showed the prevalence of obesity at 16.9% among all children and 18.0% among elementary-school children between the ages of 6 and 11 years in 2009 and 2010.4 The incidence of obesity between adolescence and adulthood in the United States was estimated at 2.5% annually from 1995 through 2000.6 In a study of 386 children between the ages of 5 and 7 years attending Philadelphia health care centers from 1996 through 2003, the incidence of obesity was 2% annually among normal-weight children and 14% among overweight children.13

Although prevalence estimates provide information on the burden of obesity, understanding incidence is key to understanding risk over a lifetime and identifying potential ages for intervention. We uncovered several important points by examining incidence. First, a component of the course to obesity is already established by the age of 5 years: half of childhood obesity occurred among children who had become overweight during the preschool years, even after the exclusion of the 12.4% of children who were already obese at the age of 5 years. There is evidence that body weight and eating patterns early in life are strongly related to subsequent obesity risks.7 Second, obesity incidence among overweight children tended to occur early in elementary school. This pattern is consistent with exhaustion of the population of persons who are highly susceptible to becoming obese.14 In contrast, among children who entered school at a normal weight, the incidence of obesity was low and constant between the ages of 5 and 14 years.

Emerging from the finding that a substantial component of childhood obesity is established by the age of 5 years are questions about how early the trajectory to obesity begins and about the relative roles of early-life home and preschool environments, intrauterine factors, and genetic predisposition. Although these questions are beyond the scope of our study, we have shown some evidence that factors that are established before birth (indicated by birth weight) and those that occur during the first 5 years of life (indicated by weight at kindergarten entry) are important. Even though high-birth-weight children made up 12% of the population, they represented more than 36% of those who were obese at the age of 14 years. Thus, more than one third of high-birth-weight children became obese adolescents, as did almost half the children (45.3%) who entered kindergarten overweight.

This study has certain limitations. First, to maintain the sample size for stratified analyses, we grouped into an “other race” category Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, and multiracial children. Second, we did not have information on weight between birth and kindergarten or after eighth grade, so we cannot map the entire trajectory of incidence or identify the age at which children who entered kindergarten overweight or obese had become overweight or obese. Lacking data before and after a period of observation, called “left and right censoring,” is common in studies of disease incidence.15 Third, the cohort is representative of children who were in kindergarten in 1998 and 1999 and may not reflect the experiences of earlier or later cohorts. Still, this cohort is of particular interest because they were growing up during the 1990s and 2000s, when obesity became a major health concern. Finally, given the focus on documenting obesity incidence, it was beyond the scope of this study to model the factors associated with the development of obesity.

A question regarding statistical analysis is how to treat data for children who are obese at one point but subsequently lose weight and become overweight or normal weight. In the analysis of incidence, we considered everyone who was not obese at a given study phase to be at risk for becoming obese by the next study phase, regardless of whether they had previously been obese. In alternative models of incidence density rates, we reported cumulative obesity risks, considering as incident cases only children who became obese during the period of observation and remained obese through the end of follow-up. The patterns from these methods are consistent, as are results from sensitivity analyses separating children who reversed weight trajectories from those who remained obese through the end of follow-up.

By the time they enter kindergarten, 12.4% of American children are already obese, and 14.9% are overweight. Almost half the obesity incidence from kindergarten through eighth grade occurs among children who were overweight as kindergartners. Furthermore, 36% of incident obesity between the ages of 5 and 14 years occurred among children who were large at birth. These findings highlight the importance of further research to understand the factors associated with the development of overweight during the first years of life. We speculate that obesity-prevention efforts that are focused on children who are overweight by the age of 5 years may be a way to target the children who are most susceptible to becoming obese during later childhood and adolescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R03HD060602).

We thank Patricia Cheung, Lisa Matz, and Mark Hutcheson for their assistance in literature searches and in the preparation of earlier versions of the figures.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glickman D, Parker L, Sim LJ, Cook HDV, Miller EA, editors. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: solving the weight of the nation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jolliffe D. Extent of overweight among US children and adolescents from 1971 to 2000. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:4–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakshman R, Elks CE, Ong KK. Childhood obesity. Circulation. 2012;126:1770–1779. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh GK, Kogan MD, van Dyck PC. Changes in state-specific childhood obesity and overweight prevalence in the United States from 2003 to 2007. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:598–607. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Nelson MC, Popkin BM. Five-year obesity incidence in the transition period between adolescence and adulthood: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:569–575. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baidal JA, Taveras EM. Childhood obesity: shifting the focus to early prevention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:1179–1181. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tourangeau K, Nord C, Lê T, Sorongon AG, Najarian M. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–99 (ECLS-K): combined user’s manual for the ECLS-K Eighth-Grade and K–8 full sample data files and electronic codebooks (NCES 2009–004) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vidmar S, Caelin J, Hesketh K, Cole TJ. Standardizing anthropometric measures in children and adolescents with new functions for egen. Stata J. 2004;4:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity world-wide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szklo M, Nieto J. Epidemiology: beyond the basics. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams RL. Taylor Series Linearization (TSL) In: Lavrakas PJ, editor. Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins JM, Khan KS, Lisi LM, Robbins SW, Michel SH, Torcato BR. Overweight among young children in the Philadelphia health care centers: incidence and prevalence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:17–20. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaupel JW, Yashin AI. Heterogeneity’s ruses: some surprising effects of selection on population dynamics. Am Stat. 1985;39:176–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleinbaum D, Klein M. Survival analysis: a self-learning text. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.