Abstract

The POU5F1 transcription factor is the gatekeeper of the pluripotent state in mammals. It is essential for epigenetic reprogramming events and also for germ cell viability. The Pou5f1 gene’s expression is tightly controlled during embryogenesis, but its regulatory regions are not fully deciphered. The GOF18ΔPE-EGFP transgene, harboring the enhanced green fluorescence protein reporter gene inserted into an 17- kilobase long mouse Pou5f1 genomic sequence, has been widely used to visualize pluripotent embryonic cells and primordial germ cells in the mouse and other mammalian species. This construct includes the Pou5f1 promoter under the control of the distal enhancer and also includes the Pou5f1 gene body and flanking sequences. In search of the essential regulatory regions of Pou5f1 we generated four shorter forms of this construct. We found that the shortest form, containing the Pou5f1 promoter and distal enhancer but lacking the gene body and upstream flanking sequences, correctly expressed EGFP in transiently transformed undifferentiated ES cells, correctly switched it off upon ES cell differentiation, and correctly kept it silenced in differentiated Hep3B cells. Similarly to the original GOF18ΔPE-EGFP, this shortest form was expressed in the fetal mouse gonad. Our data suggest that the Pou5f1 distal enhancer and proximal promoter may be sufficient to specify transgene expression in pluripotent cells.

Keywords: Pou5f1, Oct4, EGFP transgene, pluripotency

INTRODUCTION

The Pou5f1 gene (also termed Oct3, Oct4 or Oct3/4) encodes a member of the Pic-1, Oct1,2, Unc-86 (POU) transcription factor family (Yeom et al., 1996). Pou5f1 protein is present in the totipotent zygote as a maternal factor. The Pou5f1 gene is activated during cleavage stages and remains active in the inner cell mass (ICM) and epiblast. After gastrulation, Pou5f1 is exclusively expressed in the developing germ line. POU5F1 transcription factor is essential for the pluripotency of ICM cells in vivo (Nichols et al., 1998) and for the viability of primordial germ cells (PGC) (Kehler et al., 2004). Introduction of POU5F1 and few other transcription factors can reprogram somatic cells into an induced pluripotency state or even can induce trans-differentiation, altering cell fate (Sterneckert et al., 2012). Therefore, POU5F1 is not only a gatekeeper in the early mammalian development, but also a gatekeeper for reprogramming expressway (Pesce and Scholer, 2001, Sterneckert et al., 2012). Because of its strict regulation during development, reporter genes under the control of the mouse Pou5f1 regulatory elements provide suitable tools for identifying pluripotent cell types (Yeom et al., 1996). A reporter transgenic construct, GOF18ΔPE-EGFP, consisting of a 7.5 kb promoter and distal enhancer region upstream of the Pou5f1 gene, an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene, and the five exons of Pou5f1, has been used as a powerful tool to visualize pluripotent cells in mouse development (Yoshimizu et al., 1999). The GOF18ΔPE-EGFP transgene provided an EGFP expression pattern that was faithful to the endogenous Pou5f1 expression in other mammals including pigs (Kirchhof et al., 2000, Nowak-Imialek et al., 2011). Transgenic mouse strains made with GOF18ΔPE-EGFP, such as the TgOG2 line (Szabó et al., 2002, Yoshimizu et al., 1999) have been very useful for isolating PGCs and fetal germ cells using flow cytometry based on EGFP expression. We decided to find the essential components of the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP transgene that are sufficient to specify reporter expression in pluripotent embryonic stem (ES) cells and in fetal germ cells and specify its silencing in differentiated cell types. We constructed four shorter forms of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP and analyzed their expression patterns in cultured cells and mouse gonads. To this end, we found that the shortest form consisting of the Pou5f1 distal enhancer and promoter is sufficient to drive EGFP expression in undifferentiated ES cells and in the 14.5 days post coitum (dpc) fetal gonad and is also sufficient to be silenced in differentiated Hep3B cells.

RESULTS

Considerations for shortening the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP construct

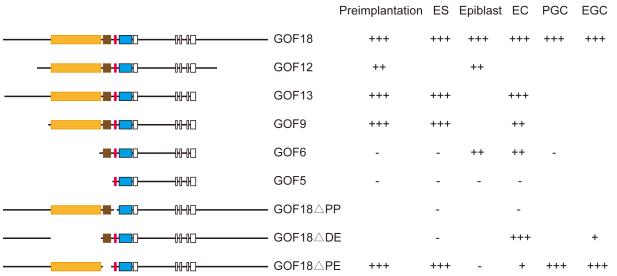

The Schöler laboratory has characterized the regulatory regions of the Pou5f1 gene in great detail using LacZ reporter transgenic constructs (Figure 1.) From these analyses we concluded that in order to keep the specific expression pattern of the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP in the shortened construct, we must keep at least two essential regions, the proximal promoter (PP) and the distal enhancer (DE) together with the EGFP reporter. The 230 bp long PP is essential for gene activity in pluripotent cells, because the promoterless GOF18ΔPP-LacZ construct is completely silent in ES cells (Figure 1). The Pou5f1 PP is also essential for restricted germ cell-specific expression after gastrulation. GCNF orphan nuclear receptor binds and represses the Pou5f1 PP upon differentiation, restricting its activity to germ cells (Fuhrmann et al., 2001). The DE is required for activating the PP during preimplantation development and in ES cells, as well as in the germ cells (compare GOF9 and GOF6; compare GOF18ΔPE-LacZ and GOF18ΔDE-LacZ). We hypothesized that we could shorten the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP construct from the 3’ end: it might be possible to remove the downstream sequences and the gene body without compromising specificity. The downstream part was not essential for expression in pluripotent cells (compare GOF18 and GOF13). The gene body may not be required, but this deletion hasn’t been tested before. Additionally, we considered that the upstream region 5’ to the DE might also be shortened, because GOF9, that lacks this region is expressed in pluripotent cells.

Fig.1. Considerations for shortening the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP construct.

Summary of transgenic experiments done by the Schöler group (Yeom et al., 1996). The different constructs are depicted with their components: LacZ reporter with SV40 polyA termination, blue box; distal enhancer (DE), orange box; proximal enhancer (PE), brown box; Pou5f1 proximal promoter (PP), red box; Pou5f1 exons, open boxes. Expression of the reporter gene is tabulated to the right: +++, high expression; ++, reduced expression; +, greatly reduced expression, compared to GF18; -, lack of expression at the different developmental stages: during preimplantation, in the epiblast, in primordial germ cells (PGC) and the cultured cell types: ES (embryonic stem) EC (embryonic carcinoma) EG (embryonic germ) cells.

Four shorter forms of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP were expressed in mouse ES cells

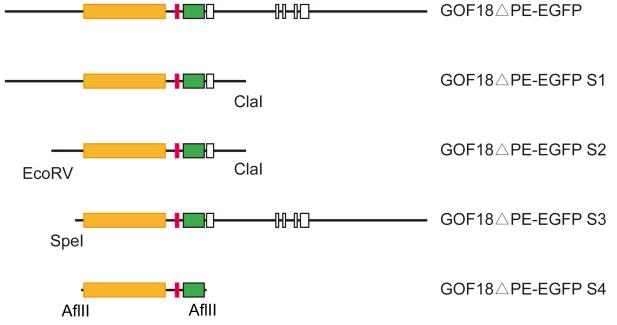

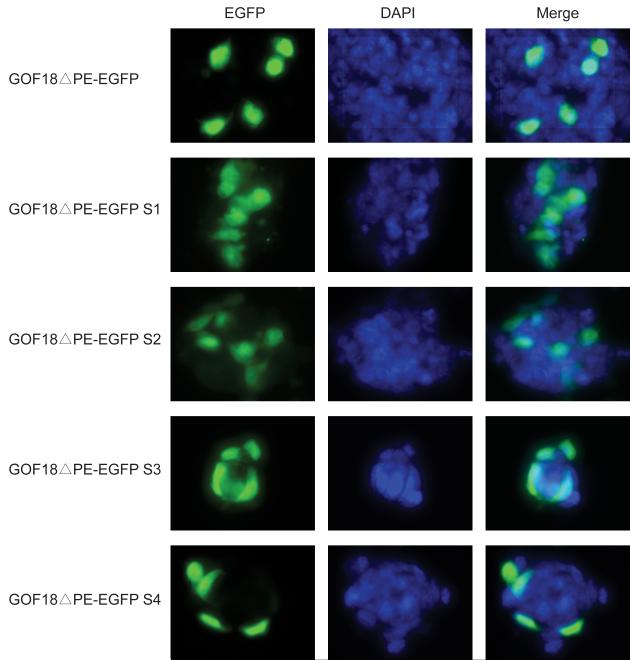

We generated four shorter forms GOF18ΔPE-EGFP, each containing the EGFP gene (Figure 2) fused to variable lengths of Pou5f1 sequences (Table 1). GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S1 retained the 7.5 kb of promoter/enhancer region and the first exon of Pou5f1 gene. GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S2 contained 5.5 kb of the promoter/enhancer region and the first exon. GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S3 contained 4.5 kb of the Pou5f1 enhancer/promoter region and five exons. GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4, the shortest form, only harbored the 3.5 kb DE-PP to drive EGFP expression. To analyze if these shorter versions of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP retain the expression specificity of the original transgene, we transfected them into mouse ES cells (Figure 3). Each of the four shorter (S1-S4) constructs drove EGFP expression in pluripotent ES cells similarly to the original GOF18ΔPE-EGFP. Only a subset of cells expressed EGFP. This was expected, because the efficiency of transient transfection is never 100%.

Fig. 2. Shortening of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP.

Four shortened forms (S1-S4) of the 17 kb long GOF18ΔPE-EGFP were generated by restriction endonuclease digestions: EGFP reporter with SV40 polyA termination, green box; distal enhancer (DE), orange box; Pou5f1 proximal promoter (PP), red box; Pou5f1 exons, open boxes.

Table 1.

Pou5f1 regulatory sequences used in the different constructs.

| Pou5f1 regulatory sequence length (kb) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Upstream | Downstream | Total |

| GOF18ΔPE-EGFP | 7.5 | 9 | 16.5 |

| GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S1 | 7.5 | 2 | 9.5 |

| GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S2 | 5.5 | 2 | 7.5 |

| GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S3 | 4.5 | 9 | 13.5 |

| GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

Fig. 3. Four shorter forms of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP were expressed in mouse ES cells.

Each plasmid DNA was transfected into mouse ES cells. Microscopy showed that all four shorter forms of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP expressed green fluorescent protein in ES cells, similarly to the original GOF18ΔPE-EGFP.

In addition, we found that the shortest form, GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4, carried the signal for repression in response to differentiation. We transfected the ES cells with the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP, GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4 and positive control Pgk promoter-EGFP plasmids in triplicates. 24 hours later we trypsinized the transfected plates and plated the ES cells on two culture dishes each. One contained ES-conditioned medium whereas the other one contained regular medium. This latter plate, therefore, had no lymphocyte inhibitory factor (LIF) to suppress the differentiation of ES cells. We trypsinized the plates three days later and subjected the cells to FACS analysis (Table 2). We found that the percent of GFP positive cells was greatly and significantly reduced (−42%, p=0.00348) in the absence of LIF in the plates transfected with the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4 construct, similarly to the plate transfected with the parental construct (−57%, p=0.01592). This suggested that the GOF constructs have started to shut down in the absence of LIF. As cell division times may also be affected in the different culture conditions, a decrease in EGFP protein or RNA levels may simply indicate the differential loss of plasmid content or episome inactivation upon cell division in cell culture and not necessarily the downregulation of the Pou5f1 promoter upon differentiation. This may also occur. However, this doesn’t account for the great level of reduction observed for the GOF constructs, because the control, Pgk promoter-EGFP, construct showed only a modest (-11%, p=0.01847) reduction in percent GFP positive cells.

Table 2.

Downregulation of Pou5f1-EGFP in the absence of conditioned medium

| Percent GFP+ cells in FACS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVERAGE (n=3) |

STDEV (n=3) |

Change | |||||

| Construct | LIF+ | LIF− | LIF+ | LIF− | Total | % | TTEST |

| Pgk-EGFP control | 28.51 | 25.15 | 2.01 | 0.93 | −3.36 | −11.77 | 0.01847 |

| GOF18ΔPE-EGFP | 1.06 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.04 | −0.60 | −56.78 | 0.01592 |

| GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4 | 3.25 | 1.88 | 0.20 | 0.36 | −1.38 | −42.32 | 0.00348 |

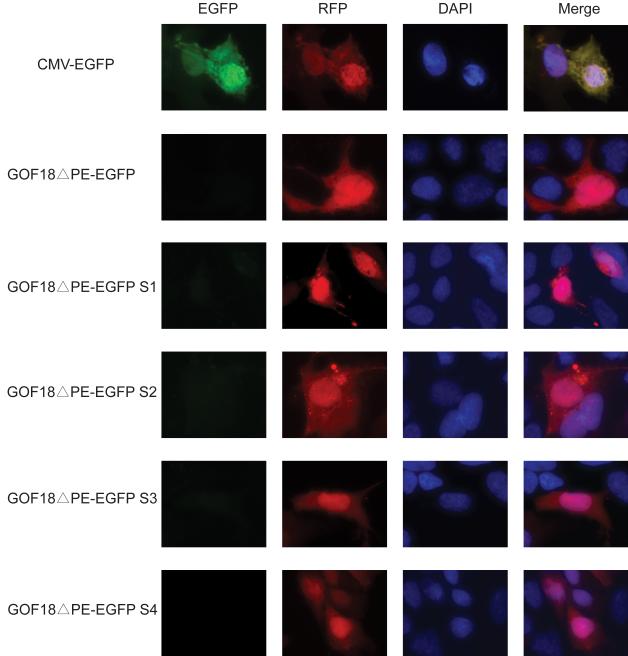

Four shorter forms of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP were not expressed in Hep3B cells

To test if these shorter forms could be correctly silenced in differentiated cells, we transfected them into Hep3B cells. We found that similarly to the parent GOF18ΔPE-EGFP transgene, none of the shorter (S1-S4) forms drove EGFP expression in Hep3B cells (Figure 4). The transfection control, red fluorescent protein (RFP), driven by the CMV promoter was expressed in each sample. Taken together, these results suggested that these four (S1-S4) shorter forms retained their restricted expression pattern specific to undifferentiated ES cells.

Fig. 4. Four shorter forms of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP were not expressed in Hep3B cells.

he expression constructs indicated to the left were transfected into Hep3B cells together with the CMV-dsRed plasmid as transfection control. Microscopy examination showed that similarly to the original GOF18ΔPE-EGFP, none of the shorter forms drove EGFP expression in differentiated Hep3B cells. However, the CMV promoter drove the control dsRed expression in each sample.

The shortest vector gives EGFP expression in 14.5 dpc mouse testis

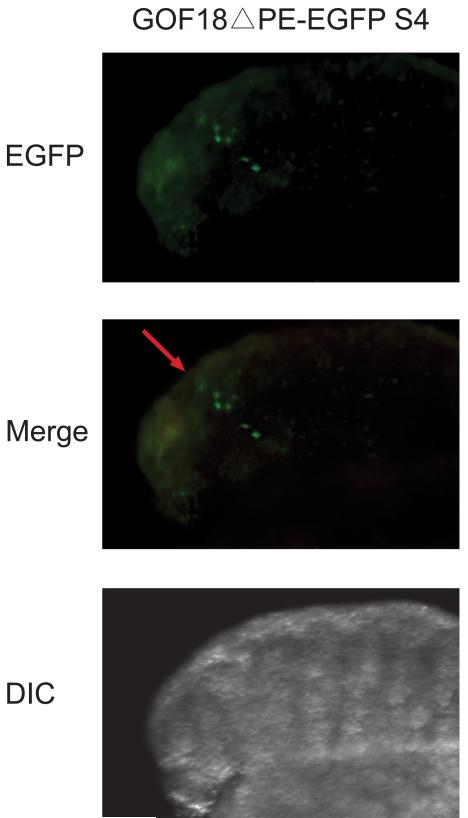

We next investigated if the DE-PP regulatory sequences of Pou5f1 could drive the EGFP expression in fetal mouse cells. We employed a simple approach to accomplish this goal through electroporation of this construct into cultured mouse embryonic gonads (Nakamura et al., 2002). We injected and electroporated the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4 into 14.5 dpc male gonads. Green fluorescence signal was found in the testicular cords where the germ cells reside. Based on this EGFP pattern it is most likely that EGFP was expressed in the fetal germ cells (Figure 5).

Fig. 5. Distal enhancer of Pou5f1 drove EGFP expression in 14.5 dpc mouse fetal gonad.

ale gonads from 14.5 dpc mouse fetuses were injected with GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4 (red arrow) and cultured for 48 hours after electroporation. GFP positive cells were observed inside the testicular cords, where the germ cells reside.

DISCUSSION

Pou5f1 expression is tightly controlled during embryogenesis. Even though the Pou5f1 gene’s transcriptional regulation is not yet completely understood, the Pou5f1 transgene has been a very useful tool to drive reporter gene expression in pluripotent embryonic cells and allowed the isolation of primordial germ cells from mixed cell population (Szabó et al., 2002, Yoshimizu et al., 1999). To find the minimal regulatory regions, essential and sufficient for specifying Pou5f1 expression, we generated four shorter forms of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP and analyzed their expression patterns in pluripotent mouse ES cells and a differentiated cell line, Hep3B cells. We found that all four shorter forms were expressed in ES cell but not in Hep3B cells, similarly to the original GOF18ΔPE-EGFP form. The shortest vector contained the DE and the PP regions in front of the EGFP. This suggested that the shortest form harbors the essential regulatory elements in the DE that activate the promoter in pluripotent ES cells and also the essential elements that repress the promoter in differentiated Hep3B cells. We then used microinjection and gonad electroporation to introduce the shortest form into cultured fetal gonads and found that EGFP expression was localized in small foci in the testicular cords where germ cells reside. This suggests that the distal enhancer is sufficient to specify Pou5f1 expression in fetal germ cells at least in cultured gonads. There may be differences in the level of expression between the constructs, but these may not hinder visualizing pluripotent cells as long as the EGFP signal is detectable in the right place and the right time. It remains to be proven that the GFP-positive cells within the gonad are genuine gonocytes. It would be tempting to differentiate the transfected ES cells to embryoid bodies and ask whether the EGFP transgene expression becomes completely downregulated upon differentiation. One could transplant S4-transfected ES cells to blastocysts, and then perform embryo transfers to assess the EGFP expression pattern in the embryo at 6.5-7.5 dpc and in the gonad at different time points. However, again, the suboptimal efficiency of transient transfection of ES cells and the normal downregulation of episomes in culture would pose technical limitations to these experiments and would make the interpretation difficult. Previous experiments in other species have shown that the entire Pou5f1genomic sequences are needed for specifying the correct expression pattern of the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP transgene (Kirchhof et al., 2000). Our results suggest that the sequences that are essential and sufficient for proper Pou5f1 gene regulation in the mouse may be concentrated on a shorter genomic region. To fully answer these questions one will need to develop a transgenic mouse line and test EGFP expression in embryos during development at different stages. Generation of a transgenic mouse with the shortest transgenic vector, GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4, is needed to confirm whether the distal enhancer is sufficient to drive Pou5f1 expression exclusively in pluripotent cells in the early embryo and in primordial germ cells after gastrulation. Nevertheless, we found that the most widely used Pou5f1 reporter construct can be shortened to its one third without losing its specific expression pattern, at least in cultured cell types and in cultured gonad. We feel that this is useful information for future studies where visualization or genetic manipulation of pluripotent cells is desired.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Construction of shorter forms of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP

Four shorter forms of GOF18ΔPE-EGFP were generated by restriction endonuclease digestion (Figure 2). GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S1 was made by ClaI digestion, removing 7 kb of the Pou5f1 gene sequence from the 3’ end. GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S2 was made by further digestion of S1 with EcoRV to remove 2 kb from the 5’end. GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S3 was made by subcloning a 14 kb long SpeI/NotI fragment (lacking 3 kb from the 5’end) into pBlueScript vector. GOF18ΔPE-EGFP S4 was made by subcloning a 4.7 kb AflII fragment, in which only Pou5f1 distal enhancer and the promoter was retained, into pSL1180 vector. Pgk-EGFP plasmid was generated by replacing the CMV promoter of pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, USA) with 0.5 kb of Pgk promoter.

Cell lines and transient transfection

Mouse A2 ES cells (129S1), provided by Jeffrey Mann, were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco-BRL, USA) supplemented with 12% fetal bovine serum, 10−4 M β-mercaptoethanol, nonessential amino acids, L-glutamine, and antibiotics at standard concentration on a layer of mitomycin-inactivated LIF-producing STOC feeder cells. One day before transfection, coverslips were coated with 0.1% gelatin for 1 hour at 37 °C in 12-well plates. ES cells were trypsinized and plated on a 10 cm plate for 30 minutes twice to remove feeder cells by differential attachment. Suspended cells were counted and plated into 12-well plate at the density of 5×105 per well and were subsequently grown in ES-conditioned medium but without feeders. The following day, 2μg of plasmid DNA was used for transfection with 5μl of LipoFectamine 2000 according to the standard procedure provided by the manufacturer (Invitrogene, USA). Microscopy was done 48 hours after transfection when cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. After three time of PBS wash, cells were mounted with Prolong Gold antifade regent with DAPI (Invitrogene, USA) overnight. Slides were sealed and kept at 4 °C before microscopy examination using an inverted fluorescence microscope. Alternatively, cells were trypsinized 24 hours after transfection and plated on duplicate 35 mm dishes with LIF (as supplied by freshly prepared conditioned medium) or without LIF (using regular medium). Three days later, cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS and fixed using 4% formaldehyde and analyzed by FACS for GFP positive cell content using a FACScalibur (BD Biosciences, USA) sorter.

Hep3B cells (ATCC) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 6% fetal bovine serum, nonessential amino acids, L-glutamine, and antibiotics, at standard concentrations. The transfection procedure was the same as for ES cells except the cell density was 3×105 in 12-well plate, and DNA:LipoFectamine 2000 ratio used was 1μg:2.5μl. For internal control, one tenth of CMV-dsRed plasmid DNA (0. 1μg) was cotransfected with each shorter construct DNA.

Gonad injection

Plasmid DNA was prepared using Qiagen endotoxin free maxiprep kit (Qiagen, USA), precipitated by ethanol, and dissolved in TE buffer at a concentration of 5μg/μl. As described by Nakamura et al (Nakamura et al., 2002), gonads were isolated from 14.5 dpc CF1 mouse embryos and kept in cold DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, nonessential amino acids, L-glutamine, and antibiotics at standard concentrations. A single gonad was washed with PBS and placed between a pair of electrodes (0.2 mm diameter, 15 mm length, 1 mm distance between electrodes; Nepa Gene Co., Ltd, Chiba, Japan) on glass dish with a small volume of PBS. The anterior-posterior axis of the gonad was parallel to the electrodes. Under microscope, approximately 0.3μl of DNA solution was hand injected by a glass capillary with mouthpiece. Right after injection, a set of electric pulses (50V, 50-ms, 100ms intervals, 10 times) was given by an electroporator (CUY21; Nepa Gene Co., Ltd, Japan) to the injected gonad to induce uptake of DNA by gonadal cells. Injected and electroporated gonads were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 48 hours on a culture insert membrane (Falcon, USA) in a 24-well dish with culture medium and examined using a Zeiss fluorescent dissecting microscope.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Dr. Hans Schöler for the GOF18ΔPE-EGFP plasmid and Dr. Jeffrey Mann for the A2 ES cells. This work was supported by NIH grant RO1GM064378 (to PES), and the 973 project 2013CB911003 and NSFC grant 31271446 (to JL).

Abbreviations

- Pou5f1

(Pic-1, Oct1,2, Unc-86 transcription factor 1)

- EGFP

(enhanced green fluorescent protein)

- PGC

(primordial germ cell)

- PP

(proximal promoter)

- DE

(distal enhancer)

- RFP

(red fluorescent protein) RFP

REFERENCES

- FUHRMANN G, CHUNG AC, JACKSON KJ, HUMMELKE G, BANIAHMAD A, SUTTER J, SYLVESTER I, SCHOLER HR, COONEY AJ. Mouse germline restriction of Oct4 expression by germ cell nuclear factor. Dev Cell. 2001;1:377–387. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEHLER J, TOLKUNOVA E, KOSCHORZ B, PESCE M, GENTILE L, BOIANI M, LOMELI H, NAGY A, MCLAUGHLIN KJ, SCHOLER HR, et al. Oct4 is required for primordial germ cell survival. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1078–1083. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRCHHOF N, CARNWATH JW, LEMME E, ANASTASSIADIS K, SCHOLER H, NIEMANN H. Expression pattern of Oct-4 in preimplantation embryos of different species. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1698–1705. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA Y, YAMAMOTO M, MATSUI Y. Introduction and expression of foreign genes in cultured mouse embryonic gonads by electroporation. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2002;14:259–265. doi: 10.1071/rd01130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHOLS J, ZEVNIK B, ANASTASSIADIS K, NIWA H, KLEWE-NEBENIUS D, CHAMBERS I, SCHOLER H, SMITH A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOWAK-IMIALEK M, KUES WA, PETERSEN B, LUCAS-HAHN A, HERRMANN D, HARIDOSS S, OROPEZA M, LEMME E, SCHOLER HR, CARNWATH JW, et al. Oct4-enhanced green fluorescent protein transgenic pigs: a new large animal model for reprogramming studies. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1563–1375. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PESCE M, SCHOLER HR. Oct-4: gatekeeper in the beginnings of mammalian development. Stem Cells. 2001;19:271–278. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-4-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STERNECKERT J, HOING S, SCHOLER HR. Concise review: Oct4 and more: the reprogramming expressway. Stem Cells. 2012;30:15–21. doi: 10.1002/stem.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZABÓ PE, HUBNER K, SCHOLER H, MANN JR. Allele-specific expression of imprinted genes in mouse migratory primordial germ cells. Mech Dev. 2002;115:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YEOM YI, FUHRMANN G, OVITT CE, BREHM A, OHBO K, GROSS M, HUBNER K, SCHOLER HR. Germline regulatory element of Oct-4 specific for the totipotent cycle of embryonal cells. Development. 1996;122:881–894. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOSHIMIZU T, SUGIYAMA N, DE FELICE M, YEOM YI, OHBO K, MASUKO K, OBINATA M, ABE K, SCHOLER HR, MATSUI Y. Germline-specific expression of the Oct-4/green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene in mice. Dev Growth Differ. 1999;41:675–684. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1999.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]