Abstract

Behçet's disease is a systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology, characterized by oral and genital ulceration, skin lesions, and uveitis as well as vascular, central nervous system, and gastrointestinal system involvement. It is prevalent in the Middle East, Mediterranean, and Eastern Asia. The aim of this review is to evaluate the gender differences in clinical manifestations of Behçet's disease, treatment responses, mortality, and morbidity. Behçet's disease has been reported to be more prevalent in males from certain geographic regions and particular ethnic groups; however, recent reports indicate more even gender distribution across the world. There are gender differences in clinical manifestations and severity of the disease. Ocular manifestations, vascular involvement, and neurologic symptoms are more frequently reported in male patients whereas oral and genital ulcers, skin lesions, and arthritis occur more frequently in female patients. The disease can have a more severe course in males, and overall mortality rate is significantly higher among young male patients.

1. Introduction

Behçet's disease (BD) is a rare immune-mediated small vessel systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology. It is a multisystem disorder that presents with episodes of mucocutaneous lesions, uveitis, arthritis, venous thrombosis, arterial aneurysms, intestinal ulcers, pulmonary lesions, and central nervous system lesions. Between episodes, clinical findings may be completely normal [1]. BD predominantly affects people with lineages from the Silk Road, particularly Turkey and Japan. BD is more prevalent in certain geographic regions and among particular ethnic groups. There is a strong association with HLA-B51 as has been confirmed by recent genome-wide association studies [2]. Studies have also indicated that shared risk loci with other autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases, such as ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and familial Mediterranean fever, implicate shared and complicated pathogenic pathways involving both the innate and adaptive immune system in Behçet's disease [3–5]. HLA-B51 has been shown to be present in 40–70% of patients from the Middle East and Asia; however, it is found in only 13% of patients in Europe and North America [6]. Patients with HLA-B51 have a sixfold increased risk of BD, and the disease is usually more severe in HLA-B51 positive patients [4]. Familial BD has been reported in 1–18% of patients, mostly in Turkish, Israeli, and Korean populations [6].

Patients often present in their 30 s–40 s with recurrent oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, and uveitis [7]. Children are rarely affected [5]. In contrast to early reports of higher male to female ratios from Turkey and Japan [8–10], this ratio is now nearly equal with the only exception being Arab countries where higher male prevalence persists. A recent large Chinese population-based study showed no significant gender difference in the incidence or prevalence of Behçet's disease [11, 12].

BD exhibits a more severe course in males as well as in patients with younger age of onset and HLA-B51 positivity [13]. According to the International Study Group (ISG) for Behçet's disease diagnostic guidelines, the patient must have recurrent oral (aphthous) ulceration (at least three times within a 12-month period) along with 2 out of the following 4 symptoms: recurrent genital ulcers, ocular inflammation (anterior and/or posterior uveitis, cells in the vitreous, and retinal vasculitis), skin lesions (including erythema nodosum, pseudofolliculitis, papulopustular lesions, and acne in postadolescents not on corticosteroids), and positive pathergy test [14]. Each of these clinical manifestations may affect men and women differently (Table 1).

Table 1.

Behçet's disease and gender differences in clinical manifestations.

| Clinical findings | Incidence/prevalence | Severity* |

|---|---|---|

| Mucocutaneous lesions | Erythema nodosum more common in females Papulopustular lesions more common in males |

Comparable |

| Oral ulcers | More in females | Comparable |

| Genital ulcers | More in females | More severe in females |

| Skin pathergy test | More in males | Comparable |

| Arthritis and arthralgia | More in females** | Comparable |

| Vascular involvement | More in males | More severe in males |

| Central nervous system involvement | More in males | More severe in males |

| Gastrointestinal manifestation | Comparable | Comparable |

| Uveitis | More in males (anterior uveitis is more common in women; panuveitis is more common in men) | More severe in males |

*Comparable indicates that the severity of these clinical manifestations were not significantly different in most studies.

**Some studies indicated arthritis to be more common in females while others showed comparable incidence.

2. Gender Differences in Extraocular Manifestations of Behçet's Disease

Mucocutaneous lesions are the most frequently observed findings of BD and include oral and genital ulcers, acneiform lesions, papulopustular lesions, erythema nodosum-like lesions, and superficial thrombophlebitis. Cutaneous lesions constitute part of the major criteria for the diagnosis. The most frequent cutaneous manifestations are erythema nodosum-like lesions, papulopustular lesions, erythema multiforme, and extragenital ulcerations. Erythema nodosum-like lesions are more frequently seen in females and typically affect the lower limbs. These lesions usually resolve within 2-3 weeks with residual pigmentation [15, 16]. Papulopustular lesions are more frequently seen in males [15–17].

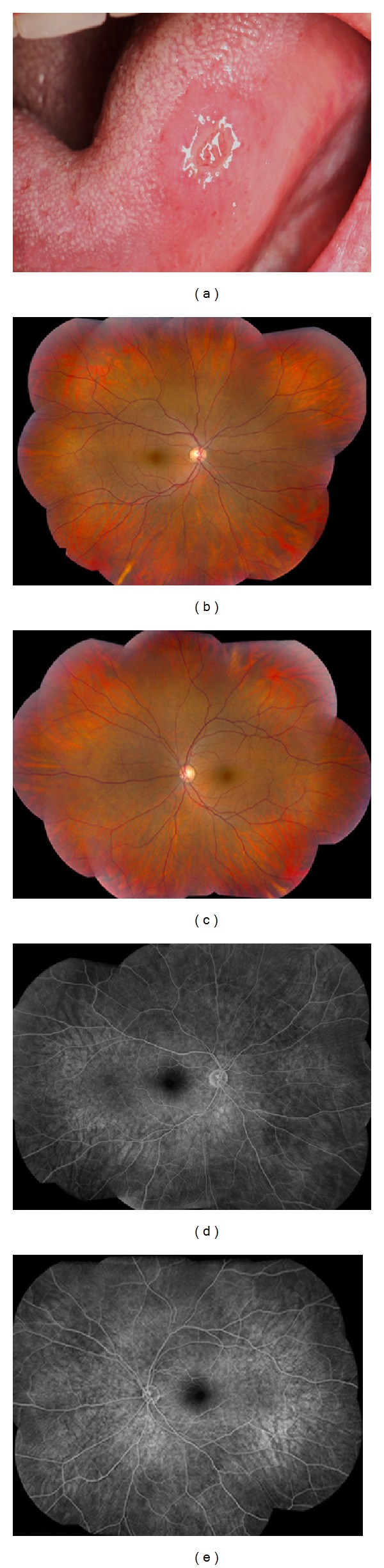

Oral aphthous ulcers are typically recurrent painful ulcerations of the oral mucosa that last up to 14 days. Oral ulcer is the most common manifestation of BD (found in 95–100% of patients) and can be the presenting manifestation in about 70% of patients [12, 18–20]. According to ISG for BD criteria, oral ulcers recurring at least three times over a 12 month period are crucial to the diagnosis [14]. In a retrospective review of 3527 BD patients, Oh et al. found that oral ulcers were more common in females and exacerbations correlated with menstrual cycles [21] (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

A 36-year-old Iranian female with incomplete Behçet's disease with history of oral ulcers (a), genital ulcers, and nongranulomatous anterior uveitis. Retinal exam was completely normal with a visual acuity of 20/16 in each eye. Fundus photos ((b) and (c)) and fluorescein angiogram ((d) and (e)) confirm the absence of retinal vasculitis and retinitis ((b)–(e)).

Genital ulcers are less likely than oral ulcers to recur, often heal with scarring, and can be found in 62% to almost 100% of BD patients [12, 22, 23]. Similar to oral ulcers, genital ulcers are also more frequent in females [11, 21, 24–28]. In males, scrotum is more likely to be involved whereas in females, genital ulcers are frequently seen on labia majora and minora [29]. Genital ulcers are especially common and larger in females with BD and resemble recurrent aphthous stomatitis [15].

The skin pathergy test is a skin hyperreactivity test induced by a needle prick. Typically, papule formation (>2 mm diameter), ≥24–48 hours following a sterile needle prick to the forearm, is considered a positive response [14]. According to the ISG for BD, pathergy positivity is among the major criteria for the diagnosis. Different pathergy reaction rates have been reported worldwide (6–71%) [30], but it is especially high in Japan (44%) [31] and the Middle East (60–70%) [32]. Pathergy positivity is more common in males [15, 16] but is not associated with an increased risk for specific mucocutaneous or systemic involvement or a more severe disease course. An epidemiologic study from Korea reported an overall female predominance among BD patients and higher positivity of pathergy test in male patients [33].

Arthritis and arthralgia have been reported in approximately 35–50% of BD patients [34]. Some reports revealed high frequencies in females (56%) [24, 35] whereas some reports indicated similar incidence in both sexes [26]. It is usually mono- or oligoarticular arthritis and typically resolves in a few weeks without deformity or radiological erosions. The knee joint is the most commonly affected followed by ankle, wrist, and elbow joints. Joint manifestations are frequently seen with erythema nodosum and thrombophlebitis and seem to be more common in patients with papulopustular lesions [22, 32].

Vascular involvement can occur in 7.7% to 43% of patients. Even though vasculitis is a significant feature of Behçet's disease, it is not one of the ISG diagnostic criteria. Both veins and arteries of all sizes can be affected with an associated thrombotic tendency [1, 10, 36–41]. Venous involvement is more common than arterial (88% versus 12%) [39]. Venous thrombosis is the most common vascular manifestation occurring in 6.2% to 33% [42, 43]. Vascular involvement in BD is more common in males and has a more severe course [37]. A review of 137 Turkish BD patients showed vascular involvement in 27.7% with venous involvement in 24% and arterial involvement in 3%. Vascular involvement was more common in males with a male to female ratio of 4.4 : 1. Additionally, ocular involvement and pathergy positivity were significantly more common among patients with vascular disease [39]. Similarly, a subsequent study of 2,147 Turkish patients with BD also showed that male patients were five times more likely to have vascular complications [10].

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement (neuro-Behçet's) occurs in approximately 5% of patients and is one of the most serious causes of long-term morbidity and mortality [44–47]. Neuro-Behçet's is more prevalent in males with a male to female ratio of 2 : 1 to 3 : 1. In a large retrospective study from Turkey, the frequency of CNS involvement was 13% in men and 5.6% in women. Among 200 Turkish neuro-Behçet's patients, the male to female ratio was 3.4 : 1. Other groups from Iraq, Tunis, and Italy have also reported higher rates of neuro-Behçet's in males with a male to female ratio ranging from 1.6 : 1 to 2.8 : 1. In these studies male gender and CNS involvement were also found to be associated with a poor prognosis [46–51]. The age of onset of neuro-Behçet's is generally 20–40 years, though it has been reported in children [52]. Neurological signs commonly develop a few years after the onset of the other systemic manifestations of BD [46, 50].

Intestinal involvement is rare but can be a common cause of mortality and severe morbidity in BD [53]. Gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations of BD usually occur 4.5–6 years after the onset of oral ulcers. The prevalence of GI involvement is higher (50–60%) in Japan and Korea, while it is much lower in Turkey and Israel (0–5%). The frequency of extraoral GI involvement varies widely among different ethnic groups [25, 53, 54]. Although several studies reported no gender difference in the incidence of GI involvement, male predominance has been reported by some [11, 25, 55]. Ulcerations may occur anywhere from the mouth to the anus in the GI tract; however, the ileocecal region with extension into the ascending colon is the most frequent site of extraoral involvement [56].

3. Gender Differences in Prevalence, Incidence, and Severity of Behçet's Disease Associated Uveitis

Uveitis in BD (BDU) has been reported in approximately 50% of the patients in multidisciplinary centers and more than 90% in ophthalmology reports [4, 57]. Patients usually present with bilateral nongranulomatous panuveitis and retinal vasculitis. However, it may rarely present as isolated anterior uveitis, particularly in female patients [58] (Figure 1). Episcleritis, scleritis, conjunctival ulcers, keratitis, orbital inflammation, isolated optic neuritis, and extraocular muscle palsies are rare forms of ocular involvement [59]. Uveitis occurs within 3–5 years after the onset of BD; however, ocular manifestations may be the initial manifestation in approximately 10–20% of cases [58, 59]. Similar to vascular and neurologic involvement, BDU is also more common in males [10]. Typically, BDU has a relapsing and remitting course with explosive episodes and quiet periods in between. Sudden onset of uveitis flare-ups and spontaneous resolution are important features of the disease [58]. Anterior uveitis (iridocyclitis) with hypopyon is very characteristic but occurs in only 10–30% of patients. Hypopyon in BD forms a smooth layer and shifts with head positioning. Posterior synechiae, peripheral anterior synechiae, iris atrophy, cataract, and secondary glaucoma can be seen as complications of recurrent anterior uveitis attacks [58]. Anterior uveitis and hypopyon occur more commonly in women whereas panuveitis and severe ocular BD are more common in men [59, 60] (Figure 2). Childhood onset BDU is also more common in males [61].

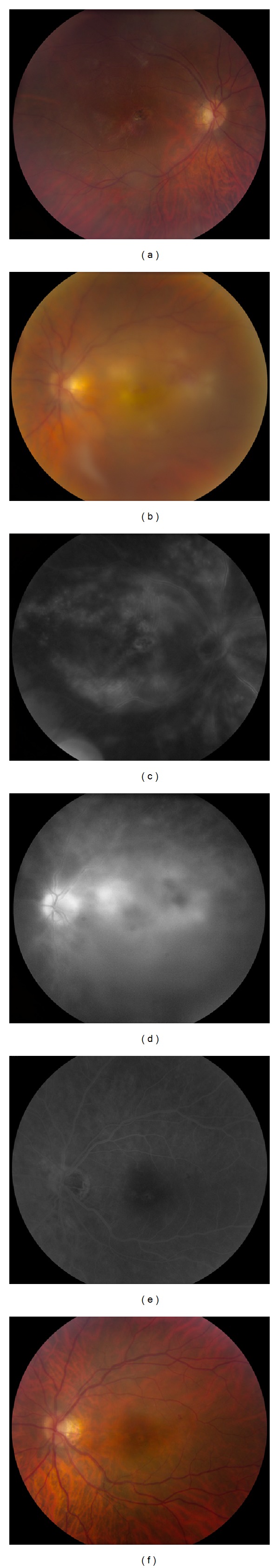

Figure 2.

A 30-year-old Jewish male presented with panuveitis, retinitis, and retinal vasculitis and was later diagnosed with Behçet's disease. Right eye was legally blind with a visual acuity of 20/200 due to a macular retinitis in the past. Left eye visual acuity was 20/640 due to active macular retinitis. Fundus photos and fluorescein angiogram show macular scar (a) in the right eye and active macular retinitis in the left eye (b) with diffuse retinal vascular leakage in both eyes (involving both veins and arteries) and late staining of the retinitis in the left eye ((c) and (d)). Left eye visual acuity improved to 20/50 after treatment with infliximab with resolution of retinitis and retinal vasculitis ((e) and (f)).

Posterior uveitis patients present with decreased vision with floaters and/or visual field defects. Diffuse vitritis, retinal infiltrates, sheathing of retinal veins, occlusive vasculitis, swelling of the optic disc, branch retinal vein occlusions, and exudative retinal detachment are common posterior segment findings. The classic posterior uveitis finding is retinal vasculitis, which can affect both arteries and veins. Retinal disease is the most serious form of ocular involvement in BD [58]. Maculopathy and optic atrophy are the most common causes of permanent visual loss [17]. Optic disc involvement can occur in the form of acute anterior neuropathy, papilledema as a result of dural sinus thrombosis or benign intracranial hypertension, neuroretinitis, or retrobulbar optic neuropathy [46, 62].

In a large retrospective study from Turkey, the mean age at onset of uveitis was 28.5 years in males and 30 years in females. Bilateral ocular involvement was seen in 78.1%. There was no gender difference in terms of bilaterality and recurrence of uveitis [61]. However, panuveitis was more common in male patients [63]. Sight-threatening fundus lesions and complications were also more common in male BD patients [61]. In a study by Tugal-Tutkun et al., hypopyon, vitritis, retinal vasculitis, retinitis, and retinal hemorrhages were also seen more frequently in male patients while papillitis was more common in females [61]. According to some reports, male patients with BDU have worse visual prognosis likely due to the fact that men with BD are more likely to have panuveitis [17, 61].

4. Gender Differences in Treatment and Prognosis of Behçet's Disease

There may be gender differences in response to treatment as well. Mat et al. reported that methylprednisolone acetate was effective for erythema nodosum in females but not in males [64]. Similarly, Yurdakul et al. reported in 116 BD patients from Turkey that colchicine had favorable effects on genital ulcers, erythema nodosum, and arthritis in females but only for arthritis in males [65]. Hamuryudan et al. showed that different dosages of thalidomide were effective for oral and genital ulcers and follicular lesions in male patients; however, the study did not assess thalidomide's effect in females because of its teratogenic effects [66]. Another male-only study reported that azathioprine 2.5 mg/kg daily was effective for the preservation of visual acuity and the prevention of incident ocular BD as well as mucocutaneous lesions and arthritis [67]. Masuda et al. reported cyclosporine 10 mg/kg daily to be more effective than colchicine 1 mg daily for the treatment of ocular disease and oral and genital ulcers in a double-masked randomized trial [68]. Interestingly, treatment side effects also differed between males and females; hirsutism with cyclosporine occurred more commonly in females while neurotoxicity was significantly more common among males [68, 69].

Several reports showed that the overall mortality rate in BD is significantly higher among male patients. The rate is especially high for young males in their 20 s–40 s [47, 70]. Common causes of mortality are pulmonary arterial aneurysms and neurological involvement, which are significantly more common among young male patients [4].

5. Possible Explanations for Gender Differences in Behçet's Disease

Autoimmune diseases tend to be more common in women of childbearing age. However, Behçet's disease is equally prevalent among males and females in some geographic regions and more prevalent in males in others [4, 34]. Overall, the disease has a more severe course and higher mortality among male patients [47]. Despite numerous studies indicating notable gender differences in ocular and extraocular manifestations as well as severity and mortality of the disease, there is no clear evidence as to what this difference stems from. Although its etiology is unknown, both genetic and environmental factors (smoking, infection, vitamin D, and immune dysregulation) have been blamed [1, 13]. Whether males are more prone to such environmental risk factors has yet to be determined. Both smoking and cessation of smoking have been implicated in severity of clinical manifestations of BD including vasculitis and mucocutaneous lesions [71–73]. Smoking was more common among male patients with BD in some studies raising the question of possible association [71–73]. Similarly, low vitamin D3 levels have been associated with BD or its severity; however, these studies failed to show significant differences in vitamin D3 levels between male and female BD patients [74, 75]. Both male gender and HLA-B51 have been consistently associated with a severe disease course and poor prognosis in BD. In fact, a recent meta-analysis study indicated that HLA-B51 was more common among male BD patients [76], suggesting there could be a genetic basis for poor prognosis among men with BD. While most other autoimmune diseases are more common among women of childbearing age, BD seems to differ with either equal gender distribution or male predominance. The relationship between BD and pregnancy is also poorly studied. Effects of pregnancy on Behçet's disease in 27 patients showed worsening of disease in 2/3 of patients during pregnancy, particularly in the 1st trimester. This same group also noted exacerbations in oral and genital ulcers during premenstrual periods. These findings suggest that progesterone may play a role in the disease course among women in a complex manner [77]. Whether other reproductive or sex hormones play any role or to what extent has yet to be determined.

6. Conclusion

In summary, mucocutaneous involvement is the hallmark of BD and is more common in females. Neurologic involvement and major vessel disease are uncommon, but such involvements are life-threatening and more common in males. Ocular BD is more common in males whereas arthritis is more frequently reported in female patients. Male patients are more likely to be affected at a younger age, have a more severe uveitis, present with worse visual acuity, and suffer vision loss over time [4, 58]. Though bilaterality and recurrence of uveitis are similar between sexes, incidence of panuveitis and vision loss are higher in men [29]. Overall mortality rates are also higher in young male patients [47]. Despite gender differences in severity of ocular and extraocular findings, visual prognosis in BDU has improved over the past decade due to more aggressive use of immunomodulatory therapy [34].

It is intriguing as to why BD is more prevalent, at least in some reports, and more severe among men when most autoimmune diseases are more prevalent or more severe among women [11]. Although some of the aforementioned risk factors may indeed be responsible for more severe disease in men, there are, unfortunately, no studies directly evaluating possible reasons for gender differences in BD. Translational and epidemiologic studies are needed to further address the question of gender in Behçet's disease.

Acknowledgments

This study has been sponsored by the NEI Intramural Research Program and this research was made possible through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and generous contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from Pfizer Inc., The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, as well as other private donors. For a complete list, please visit the foundation website at http://www.fnih.org/work/programs-development/medical-research-scholars-program.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Gül A. Behçet's disease: an update on the pathogenesis. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2001;19(5, supplement 24):S6–S12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remmers EF, Cosan F, Kirino Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions associated with Behçet's disease. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(8):698–702. doi: 10.1038/ng.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGonagle D, McDermott MF. A proposed classification of the immunological diseases. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3(8, article e297) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yazici H, Fresko I, Yurdakul S. Behçet's syndrome: disease manifestations, management, and advances in treatment. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2007;3(3):148–155. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirino Y, Zhou Q, Ishigatsubo Y, et al. Targeted resequencing implicates the familial Mediterranean fever gene MEFV and the toll-like receptor 4 gene TLR4 in Behçet disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(20):8134–8139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306352110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fietta P. Behçet's disease: familial clustering and immunogenetics. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2005;23(4, supplement 38):S96–S105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yazici H, Yurdakul S, Hamuryudan V, Fresko I. Behçet’s syndrome. In: Hochberg MC, Silman JA, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, editors. Rheumatology. 3rd edition. London, UK: Mosby; 2003. pp. 1665–1669. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saylan T, Ozarmagan G, Azizlerli G, Ovül C, Oke N. Behçet disease in Turkey. Zeitschrift für Hautkrankheiten. 1986;61(15):1120–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gürler A, Boyvat A, Türsen U. Clinical manifestations of Behçet's disease: an analysis of 2147 patients. Yonsei Medical Journal. 1997;38(6):423–427. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1997.38.6.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zouboulis CHC, Djawari D, Kirch W. Adamantiades-Behçet's disease in Germany. In: Godeau P, Wechsler B, editors. Behçet's Disease. 1st edition. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 1993. pp. 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- 11.See LC, Kuo CF, Chou IJ, Chiou MJ, Yu KH. Sex- and age-specific incidence of autoimmune rheumatic diseases in the Chinese population: a Taiwan population-based study. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2013;43(3):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davatchi F, Shahram F, Chams-Davatchi C, et al. Behçet's disease: from east to west. Clinical Rheumatology. 2010;29(8):823–833. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gül A. Behçet's disease as an autoinflammatory disorder. Current Drug Targets: Inflammation & Allergy. 2005;4(1):81–83. doi: 10.2174/1568010053622894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Study Group for Behçet's Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet's disease. The Lancet. 1990;335(8697):1078–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alpsoy E, Zouboulis CC, Ehrlich GE. Mucocutaneous lesions of Behçet’s disease. Yonsei Medical Journal. 2007;48(4):573–585. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2007.48.4.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alpsoy E, Donmez L, Onder M, et al. Clinical features and natural course of Behçet’s disease in 661 cases: a multicentre study. British Journal of Dermatology. 2007;157(5):901–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yazici H, Tüzün Y, Pazarli H, et al. Influence of age of onset and patient's sex on the prevalence and severity of manifestations of Behçet's syndrome. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1984;43(6):783–789. doi: 10.1136/ard.43.6.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebert EC. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Behçet's disease. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2009;54(2):201–207. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang LY, Zhao DB, Gu J, Dai SM. Clinical characteristics of Behçet's disease in China. Rheumatology International. 2010;30(9):1191–1196. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shahram F, Davatchi F, Nadji A, et al. Recent epidemiological data on Behçet's disease in Iran. The 2001 survey. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2003;528:31–36. doi: 10.1007/0-306-48382-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh SH, Han EC, Lee JH, Bang D. Comparison of the clinical features of recurrent aphthous stomatitis and Behçet's disease. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2009;34(6):e208–e212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koné-Paut I, Yurdakul S, Bahabri SA, et al. Clinical features of Behçet's disease in children: an international collaborative study of 86 cases. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1998;132(4):721–725. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davatchi F, Shahram F, Chams-Davatchi C, et al. Behcet’s disease: is there a gender influence on clinical manifestations? International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2012;15(3):306–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ideguchi H, Suda A, Takeno M, Ueda A, Ohno S, Ishigatsubo Y. Behçet disease: evolution of clinical manifestations. Medicine. 2011;90(2):125–132. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318211bf28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tursen U, Gurler A, Boyvat A. Evaluation of clinical findings according to sex in 2313 Turkish patients with Behçet’s disease. International Journal of Dermatology. 2003;42(5):346–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prokaeva T, Madanat W, Yermakova N, Alekberova Z. Sex dimorphism of Behçet’s disease. In: Godeau P, Wechsler B, editors. Behçet’s Disease. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 1993. pp. 219–221. [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Neill TW, Rigby AS, McHugh S, Silman A, Barnes C. Regional differences in clinical manifestations of Behçet’s disease. In: Godeau P, Wechsler B, editors. Behçet’s Disease. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 1993. pp. 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evereklioglu C. The migration pattern, patient selection with diagnostic methodological flaw and confusing naming dilemma in Behçet disease. European Journal of Echocardiography. 2007;8(3):167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khairallah M, Accorinti M, Muccioli C, Kahloun R, Kempen JH. Epidemiology of Behçet disease. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2012;20(5):324–335. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2012.723112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zouboulis CC. Epidemiology of Adamantiades-Behçet's disease. Annales de Médecine Interne. 1999;150(6):488–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakae K, Masaki F, Hashimoto T, Inaba G, Mochizuki M, Sakane T. Recent epidemiological features of Behçet’s disease in Japan. In: Wechsler B, Godeau P, editors. Behçet’s Disease. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Excerpta Medica; 1993. pp. 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yurdakul S, Yazici H. Behçet's syndrome. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2008;22(5):793–809. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bang D, Lee JH, Lee E-S, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical survey of Behçet’s disease in Korea: the first multicenter study. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2001;16(5):615–618. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.5.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalvi SR, Yildirim R, Yazici Y. Behçet's Syndrome. Drugs. 2012;72(17):2223–2241. doi: 10.2165/11641370-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamzaoui A, Klii R, Harzallah O, Attig C, Mahjoub S. Behçet's disease in women. La Revue de Médecine Interne. 2012;33(10):552–555. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet's disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(17):1284–1291. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zierhut M, Mizuki N, Ohno S, et al. Immunology and functional genomics of Behçet’s disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2003;60(9):1903–1922. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2333-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lie JT. Vascular involvement in Behçet's disease: arterial and venous and vessels of all sizes. The Journal of Rheumatology. 1992;19(3):341–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koç Y, Güllü I, Akpek G, et al. Vascular involvement in Behçet's disease. The Journal of Rheumatology. 1992;19(3):402–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Dalaan AN, Al Balaa SR, El Ramahi K, et al. Behçet's disease in Saudi Arabia. The Journal of Rheumatology. 1994;21(4):658–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Jesus H, Rosa M, Queiroz MV. Vascular involvement in Behçet's disease. An analysis of twelve cases. Clinical Rheumatology. 1997;16(2):220–221. doi: 10.1007/BF02247857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nadji A, Shahram F, Davatchi F. Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease: report of 323 cases. Proceedings of the 8th International Congress on Behcet’s Disease; 1998; Milano, Italy. Prex; p. p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muftuoglu A, Yurdakul S, Yazici H, et al. Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease—a review of 129 cases. In: Lehner T, Barnes CG, editors. Recent Advances in Behçet’s Disease. Vol. 103. London, UK: Royal Society of Medicine Services; 1986. pp. 255–260. (International Congress and Symposium Series). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ildan F, Göçer AI, Bağdatoğlu H, Tuna M, Karadayi A. Intracranial arterial aneurysm complicating Behçet's disease. Neurosurgical Review. 1996;19(1):53–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00346612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakasu S, Kaneko M, Matsuda M. Cerebral aneurysms associated with Behçet’s disease: a case report. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2001;70(5):682–684. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.5.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akman-Demir G, Serdaroglu P, Tasçi B. Clinical patterns of neurological involvement in Behçet's disease: evaluation of 200 patients. Brain. 1999;122, part 11:2171–2182. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.11.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kural-Seyahi E, Fresko I, Seyahi N, et al. The long-term mortality and morbidity of Behçet syndrome: a 2-decade outcome survey of 387 patients followed at a dedicated center. Medicine. 2003;82(1):60–76. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Houman MH, Bellakhal S, Salem TB, et al. Characteristics of neurological manifestations of Behçet's disease: a retrospective monocentric study in Tunisia. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2013;115(10):2015–2018. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Talarico R, d'Ascanio A, Figus M, et al. Behçet's disease: features of neurological involvement in a dedicated centre in Italy. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2012;30(3, supplement 72):S69–S72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Araji A, Sharquie K, Al-Rawi Z. Prevalence and patterns of neurological involvement in Behçet’s disease: a prospective study from Iraq. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2003;74(5):608–613. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.5.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Araji A, Kidd DP. Neuro-Behçet’s disease: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management. The Lancet Neurology. 2009;8(2):192–204. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uluduz D, Kürtüncü M, Yapıcı Z, et al. Clinical characteristics of pediatric-onset neuro-Behçet disease. Neurology. 2011;77(21):1900–1905. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318238edeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Korman U, Cantasdemir M, Kurugoglu S, et al. Enteroclysis findings of intestinal Behçet disease: a comparative study with Crohn disease. Abdominal Imaging. 2003;28(3):308–312. doi: 10.1007/s00261-002-0036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yurdakul S, Tüzüner N, Yurdakul I, Hamuryudan V, Yazici H. Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's syndrome: a controlled study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1996;55(3):208–210. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.3.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kötter I, Dürk H, Fieribeck G, Pleyer U, Zierhut M, Saal JG. Behçet’s disease in 39 German and Mediterranean patients. In: Godeau P, Wechsler B, editors. Behçet’s Disease. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 1993. pp. 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheon JH, Han DS, Park JY, et al. Development, validation, and responsiveness of a novel disease activity index for intestinal Behcet’s disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2011;17(2):605–613. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang P, Fang W, Meng Q, Ren Y, Xing L, Kijlstra A. Clinical features of chinese patients with Behçet's disease. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2):312.e4–318.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tugal-Tutkun I. Behçet's uveitis. Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009;16(4):219–224. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.58425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evereklioglu C. Current concepts in the etiology and treatment of Behçet disease. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2005;50(4):297–350. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramsay A, Lightman S. Hypopyon uveitis. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2001;46(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tugal-Tutkun I, Onal S, Altan-Yaycioglu R, Huseyin Altunbas H, Urgancioglu M. Uveitis in Behçet disease: an analysis of 880 patients. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2004;138(3):373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujikado T, Imagawa K. Dural sinus thrombosis in Behçet’s disease—a case report. Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology. 1994;38(4):411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Verity DH, Marr JE, Ohno S, Wallace GR, Stanford MR. Behçet’s disease, the Silk Road and HLA-B51: historical and geographical perspectives. Tissue Antigens. 1999;54(3):213–220. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.1999.540301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mat C, Yurdakul S, Uysal S, et al. A double-blind trial of depot corticosteroids in Behçet’s syndrome. Rheumatology. 2006;45(3):348–352. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yurdakul S, Mat C, Tüzün Y, et al. A double-blind trial of colchicine in Behçet's syndrome. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2001;44(11):2686–2692. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200111)44:11<2686::aid-art448>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamuryudan V, Mat C, Saip S, et al. Thalidomide in the treatment of the mucocutaneous lesions of the Behçet syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1998;128(6):443–450. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-6-199803150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yazici H, Pazarli H, Barnes CG, et al. A controlled trial of azathioprine in Behçet’s syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;322(5):281–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002013220501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Masuda K, Nakajima A, Urayama A, Nakae K, Kogure M, Inaba G. Double-masked trial of cyclosporin versus colchicine and long-term open study of cyclosporin in Behçet’s disease. The Lancet. 1989;1(8647):1093–1096. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92381-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Akmar-Demir G, Ayranci O, Kurtuncu M, Vanli EN, Mutlu M, Tugal-Tutkun I. Cyclosporine for Behçet’s uveitis: is it associated with an increased risk of neurological involvement? Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2008;26(4, supplement 50):S84–S90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seyahi E, Yazici H. Prognosis in Behçet’s syndrome. In: Yazici Y, Yazici H, editors. Behçet’s Syndrome. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2010. pp. 285–295. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Özer HT, Günesaçar R, Dinkçi S, Özbalkan Z, Yildiz F, Erken E. The impact of smoking on clinical features of Behçet's disease patients with glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2012;30(3, supplement 72):S14–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rizvi SW, McGrath H., Jr. The therapeutic effect of cigarette smoking on oral/genital aphthosis and other manifestations of Behçet’s disease. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2001;19(5, supplement 24):S77–S78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aramaki K, Kikuchi H, Hirohata S. HLA-B51 and cigarette smoking as risk factors for chronic progressive neurological manifestations in Behçet’s disease. Modern Rheumatology. 2007;17(1):81–82. doi: 10.1007/s10165-006-0541-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Can M, Gunes M, Haliloglu OA, et al. Effect of vitamin D deficiency and replacement on endothelial functions in Behçet's disease. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2012;30(3, supplement 72):S57–S61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamzaoui K, Dhifallah IB, Karray E, Sassi FH, Hamzaoui A. Vitamin D modulates peripheral immunity in patients with Behçet’s disease. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2010;28(4, supplement 60):S50–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maldini C, Lavalley MP, Cheminant M, de menthon M, Mahr A. Relationships of HLA-B51 or B5 genotype with Behçet’s disease clinical characteristics: systematic review and meta-analyses of observational studies. Rheumatology. 2012;51(5):887–900. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bang D, Chun YS, Haam IB, Lee E-S, Lee S. The Influence of pregnancy on Behçet’s disease. Yonsei Medical Journal. 1997;38(6):437–443. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1997.38.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]