Abstract

Rationale

To date, there has been no specific marker of the first heart field to facilitate understandings of contributions of the first heart field to cardiac lineages. Cardiac arrhythmia is a leading cause of death, often resulting from abnormalities in the cardiac conduction system (CCS). Understanding origins and identifying markers of CCS lineages is an essential step toward modeling diseases of the CCS and for development of biological pacemakers.

Objective

To investigate HCN4 as a marker for the first heart field and for precursors of distinct components of the CCS, and gain insight into contributions of first and second heart lineages to the CCS.

Methods and Results

HCN4-CreERT2, -nuclear LacZ and -H2BGFP mouse lines were generated. HCN4 expression was examined by means of immunostaining with HCN4 antibody and reporter gene expression. Lineage studies were performed using HCN4CreERT2, Isl1Cre, Nkx2.5Cre, and Tbx18Cre, coupled to co-immunostaining with CCS markers. Results demonstrated that, at cardiac crescent stages, HCN4 marks the first heart field, with HCN4CreERT2 allowing assessment of cell fates adopted by first heart field myocytes. Throughout embryonic development, HCN4 expression marked distinct CCS precursors at distinct stages, marking the entire CCS by late fetal stages. We also noted expression of HCN4 in distinct subsets of endothelium at specific developmental stages.

Conclusions

This study provides insight into contributions of first and second heart lineages to the CCS and highlights the potential utility of HCN4 in conjunction with other markers for optimization of protocols for generation and isolation of specific conduction system precursors.

Keywords: Cardiac lineage, cardiac conduction system, HCN4, heart field, cardiac development, cardiac arrhythmia, transgenic model, cardiac biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac arrhythmias are a leading cause of death, and are often a result of abnormalities in the specialized cardiac conduction system (CCS). Understanding origins of CCS lineages, and identifying markers that can be utilized for their isolation from hESCs or iPSCs is an essential step toward modeling diseases of the CCS, to study drug responses of specific CCS lineages, or to develop biological pacemakers.

The CCS consists of sinoatrial node (SAN), atrioventricular node (AVN) and peripheral components of the fast conducting His-Purkinje fibers. CCS formation is a complex process that involves multiple cell types. During mouse development, the first heartbeat is recorded in the inflow tract as early as E8.01, 2, and later, the sinus venosus of the forming heart tube functions as a primitive pacemaker region. The first morphologically discernable SAN is formed at E11.5 which becomes further mature and fully functional at E13.53, 4. A subset of atrioventricular (AV) canal tissue gives rise to AV conduction system5. Early retroviral labeling studies demonstrated that CCS and working myocyte lineages shared a common progenitor6, 7 and demonstrated that the Purkinje fibers are derived from differentiated ventricular cardiomyocytes8-11. However, questions remain as to lineage origins and the dynamic formation of each component of the CCS during development.

In the last decade, a new paradigm for heart development has emerged from lineage studies which demonstrated distinct populations giving rise to the heart, the first and the second heart lineages, based on dye labeling studies in chick, and retrospective clonal analysis in mouse embryos12-14. These lineages are thought to diverge around the onset of gastrulation15.

The first lineage gives rise to the first heart field, which is defined as the first cells to differentiate in the cardiac crescent 12, 16. Thus, the first heart field is comprised of differentiated myocytes that are precursors of distinct myocyte populations within the developing heart. Myocytes of the first heart field give rise to the early heart tube and later give rise to most myocytes of the left ventricle and a subset of myocytes within both atria.

The second lineage gives rise to the second heart field, which, in contrast to the first heart field, is comprised of undifferentiated progenitors. At cardiac crescent stages, second heart field progenitors are localized medial and posterior to the first heart field. Growth of the heart after early heart tube stages occurs by successive addition of differentiating second heart field cells to both poles of the heart. The second heart field will give rise to the right ventricle, outflow tract, and a majority of cells within the left and right atria. Studies of the second heart field have been greatly facilitated by discovery of the transcription factor Isl1 as a marker for progenitors of the second heart field17. In contrast, studies of the first heart field have been constrained by lack of a comparable marker.

It has been shown that a posteriormost subset of the second heart field, the “posterior heart field”, marked by Tbx18Cre contributes to SAN formation18, 19. However, contributions of first or second heart fields to each component of the developing CCS have not yet been addressed.

The hyperpolarization activated nucleotide gated cation channel HCN4 is a pacemaker channel that is highly expressed in the SAN during development and in the adult20-22. In studying expression of HCN4, we noted that HCN4 was expressed in the first differentiating cells of the cardiac crescent, and was expressed transiently throughout the early heart tube 23, suggesting that HCN4 may act as a potential marker of the first heart field, and additionally, as a marker for pacemaker cells of the heart. In this study, we generated several HCN4 knockin mouse lines, including HCN4 -CreERT2, and -nuclear (n) lacZ or -H2BGFP. Data from these mouse lines, together with data generated using other mouse models marking distinct cardiac lineages, allowed us to assess contributions of first and second heart field lineages to the CCS. We found that earliest HCN4 expression marks the first heart field, and that HCN4 is dynamically expressed in distinct differentiated cardiomyocyte precursors at different stages of heart development, including myocyte precursors that give rise to distinct components of the CCS. From late fetal to early adult stages, HCN4 expression marks all components of the CCS. We also noted HCN4 expression in specific subsets of endothelium at distinct times during development. Our data give insight into the activation of HCN4 during development of distinct conduction system precursors, and suggest the utility of HCN4 in concert with other markers to isolate specific CCS precursors at distinct stages of development.

METHODS

Animals and tamoxifen induction

To generate HCN4CreERT2 knockin mouse lines, a SalI DNA cassette containing Cre-ERT2 was inserted immediately before endogenous ATG of HCN4 gene. Two recombinant clones were used for blastocyst injections and chimeric mice were crossed to C57BL/6J females to generate heterozygous HCN4CreERT2 knock-in mice (Online Figure I-A). A similar strategy was used to generate HCN4H2BGFP and HCN4nLacZ knock-in allele (Online Figure I-B, C).

For lineage analysis, Cre mice were crossed with RosaLacZ24, Rosa-tdTomato 25 or Rosa mT/mG26 reporter mice and pregnant female mice at desired times were fed 150μl (≤E11.5) to 250μl (≥E12.5) of tamoxifen (10mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by oral gavage. Samples were harvested at E16.5 or desired time points.

All the experiments involving mice were carried out in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of USCD, USA (A3033-01) and by the Animal Committee of Tongji University School of Medicine, China (TJmed-010-10).

Immunohistochemistry and X-gal staining

Immunohistochemistry and X-gal staining were performed as described27. Briefly, samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), embedded, sectioned and immunostained with antibodies as list below: rat anti-HCN4 (Abcam), rabbit anti-Cx40 (Santa Cruz, Biotechnology), goat anti-Tbx3 (Santa Cruz, Biotechnology), mouse anti-NKX2.5 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rat anti-PECAM-1 (BD Pharmingen), mouse anti-MF-20 (DSHB) and mouse anti-Troponin T (NeoMarkers, MSZ-295-P). The secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor 488, 594 and 647 conjugated (Invitrogen).

For quantitative assessment, hearts of appropriate developmental stages were cut at 10μm, every fourth to sixth section was stained and cells positive for lineage marker (mGFP+) within each defined area of the CCS were counted. Relative contribution of each lineage was expressed as a percentage of total number of HCN4 or Cx40 expressing cells within the same CCS area.

For wholemount immunostaining, samples were fixed in 4% PFA and dehydrated in gradients of methanol (50, 70, 100%) for 1 hour each. Samples were fixed in methanol/DMSO (4:1) overnight, then transfered to methanol/ DMSO/H2O2 (4:1:1) at room temperature for 6 hours. Samples were rehydrated and stained at 4°C with antibody to Isl1 (DSHB) for 48 hours, and then secondary antibody for 24 hours at 4°C. Samples were washed and incubated in DAB solution (Vector).

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean±SEM and student t-test was used for 2-group comparisons.

For experimental details, see the Online Supplemental Material.

RESULTS

Expression of HCN4nLacZ in the first heart field and the CCS

To better facilitate visualization of HCN4 expression, we generated mice with CreERT2, or a nuclear localized (n) LacZ or H2BGFP 28 knocked into the endogenous HCN4 locus (Online Figure I), and analyzed reporter expression in the heart during development.

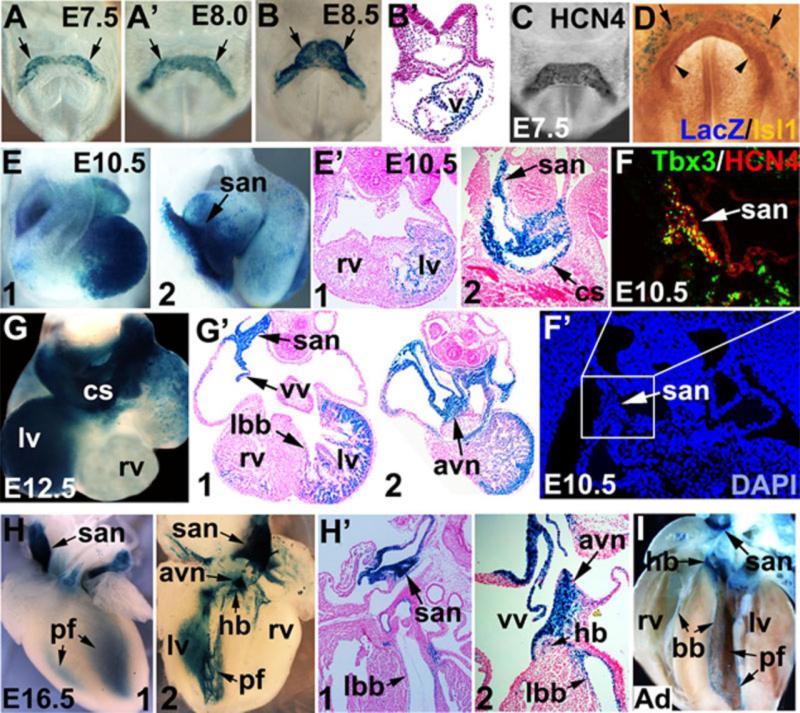

Consistent with previous RNA in situ data 23, expression of HCN4nlacZ was first observed in the cardiac crescent at E7.5 (Fig. 1A), and remained on throughout the early heart tube at around E8.0-8.5 (Fig. 1A-B’). Wholemount immunostaining at E7.5 with antibody to HCN4 revealed expression of HCN4 in the cardiac crescent (Fig. 1C), consistent with previous RNA in situ analyses 23 and expression of the HCN4nLacZ reporter (Fig, 1A). Wholemount Xgal staining and coimmunostaining at E7.5 with antibody to Isl1, a marker of the second heart field, revealed that HCN4nLacZ expression was adjacent and lateral to Isl1 expressing second heart field cells (Fig. 1D, arrowhead), suggesting that earliest HCN4 expression marks the first heart field.

Figure 1. Expression of HCN4nLacZ in the heart during development.

(A-B) Wholemount and section Xgal staining from E7.5 to E8.5 revealed expression of HCN4nLacZ in cardiac crescent (A, A’, arrow) and heart tube (B, B’, arrow). C) Wholemount immunostaining with antibody to HCN4 revealed expression of HCN4 protein in cardiac crescent at E7.5. D) Wholemount Xgal staining and immunostaining with antibody to Isl1 revealed expression of HCN4nLacZ in cardiac crescent (arrow), directly adjacent and lateral to the second heart field marked by Isl1 (arrowhead). E. E’) At E10.5, HCN4nLacZ was expressed in left ventricle (lv), sinus venosus (sv), sinoatrial node (san) and coronary sinus (cs), with slight expression in the right ventricle (rv) (E1, ventral view, E2, right side view of the heart). F, F’) Colocalization of HCN4 and Tbx3 in the SAN. G, G’) At E12.5, HCN4nLacZ was expressed in left ventricle, coronary sinus, some cells within the atria, venous valves (vv) and a small number of cells in right ventricle (rv). Expression was also observed in san, atrioventricular node (avn), and left bundle branch (lbb). H- I) At E16.5 (H1, ventral view, H2, open book view, H’1 and 2) and postnatal heart (I), expression of HCN4nLacZ was confined to the cardiac conduction system, including san, avn, His bundle (hb), bundle branches (bb) and Purkinje fibers (pf), as well as in venous valves.

At E10.5-E12.5, HCN4nlacZ was highly expressed in some components of the CCS, including SAN, AVN, and left bundle branches (lbb) (Fig. 1E, E’, G, G’). Interestingly, expression of HCN4nLacZ at these stages was also prominent in left ventricular myocardium and atria, with some expression in a small subset of right ventricular myocardium (Fig. 1E1, E’1, G, G’), consistent with HCN4 expression in the first heart field. Because previous RNA in situ had revealed that HCN4 expression at E11.5-12.5 is confined to the vena cava, sinoatrial junctions, and coronary sinus 23, expression of the HCN4nlacZ reporter in left ventricle and atria at this stage is likely to reflect perdurance of the β-galactosidase protein, acting as a lineage tracer. Alternatively, it may be due to loss of endogenous negative regulation because of the introduction of heterologous UTRs in the targeting construct. Coimmunostaining with antibodies to HCN4 and Tbx3, a marker of the SAN, revealed HCN4 expression in SAN at E10.5 (Fig. 1F, F’).

With further development, expression of HCN4nLacZ was gradually confined to the CCS. At E16.5 (Fig. 1H, H’) and in adult heart (Fig. 1I), the HCN4nlacZ transgene was expressed within all parts of the CCS, including SAN, the crista terminalis (Ct), AVN, His bundle (hb), bundle branches (bb) and Purkinje fibers (pf).

HCN4 is expressed in cardiomyocytes, and in some endothelial populations

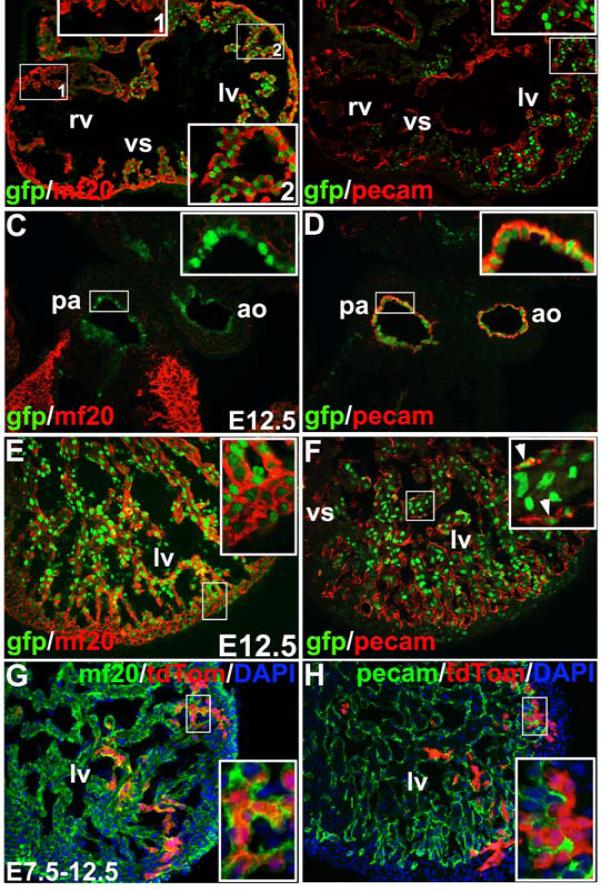

Expression of HCN4H2BGFP during development was consistent with that of HCN4nLacZ (Online Figure II). To examine the cell identity of HCN4 expressing cells within the heart, we performed immunostaining with antibodies to cardiomyocytes (MF20, Troponin T and Nkx2.5) and endothelial cells (PECAM) and colocalized these markers with HCN4H2BGFP at E9.5 to E12.5 (Figure 2A-F and not shown). At E9.5, HCN4H2BGFP cells were observed prominently in the left ventricle and atria, with a few GFP cells in right ventricular trabeculae, but not right ventricular wall (Fig. 2A, inset1 and 2). These HCN4H2BGFP cells coexpressed cardiomyocyte markers MF20 (Fig. 2A, inset 2), Nkx2.5 and Troponin T (not shown). However, expression of HCN4H2BGFP at this stage did not colocalize with the endothelial marker PECAM (Fig. 2B, inset). At E12.5, HCN4H2BGFP was expressed in endothelial cells of the aorta (ao) and pulmonary artery (pa), co-expressed with PECAM (Fig. 2D, inset), but not MF20 (Fig. 2C, inset). The majority of HCN4H2BGFP cells in left ventricle at E12.5 co-expressed MF20 (Fig. 2E, inset), and a subset of HCN4H2BGFP cells also expressed PECAM (Fig. 2F, inset).

Figure 2. HCN4 is expressed in cardiomyocytes, and in some endothelial populations.

A) Co-expression of HCN4H2BGFP and myocyte marker mf20 (A) at E9.5. Majority of mf20 expressing atrial myocytes and left ventricular (lv) myoctyes coexpress HCN4H2BGFP (A, inset-2). A few HCN4H2BGFP cells were also observed in right ventricular trabeculae around the ventricular septum (vs). Few if HCN4H2BGFP cells were observed in the free wall of the right ventricle (A, inset-1). B) At E9.5, few if any HCN4H2BGFP cells in the heart express endothelium/endocardial marker pecam (B, inset). C-H) Coexpression of HCN4H2BGFP and mf20 and pecam at E12.5. HCN4H2BGFP is expressed in the endothelial cells of the aorta (ao) and pulmonary artery (pa), that coexpress with pecam (D, inset), but not mf20 (C, inset). Majority of HCN4H2BGFP cells in the left ventricle coexpress mf20 (E, inset), a portion of HCN4H2BGFP cells express pecam (F, inset). HCN4-CreERT2 lineage labeled cells (tdTomato) coexpressed mf20 (G, inset) or but not pecam (H, inset).

To examine the fate of HCN4 expressing cells, we generated an HCN4 tamoxifen-inducible Cre by knocking CreERT2 into the endogenous HCN4 locus (Online Figure I). To examine whether the earliest HCN4 lineages contributed to myocardium and/or endothelium/endocardium, HCN4CreERT2 mice were crossed with Rosa-tdTomato indicator mice25, pregnant females were fed with tamoxifen at E7.5, and hearts were analyzed at E12.5 by direct visualization of tdTomato and co-immonstained with MF20 or PECAM antibodies. HCN4-CreERT2 lineage labeled cells (red) were observed in the left ventricle which coexpressed MF20 (Fig. 2G, inset), but not PECAM (Fig. 2H, inset).

Together, these studies suggested that earliest HCN4 lineages do not contribute to endocardium, and that HCN4 is de novo expressed in endothelial/endocardial cells at later developmental stages. At later stages of development (E16.5) and adult, we also observed expression of HCN4nLacZ in a subset of endothelial cells of the aorta, pulmonary artery and coronary arteries, but not in superior vena cava (Online Figure III, data not shown).

Contribution of HCN4 lineages to first heart lineages and the CCS during development revealed by HCN4CreERT2 fate mapping

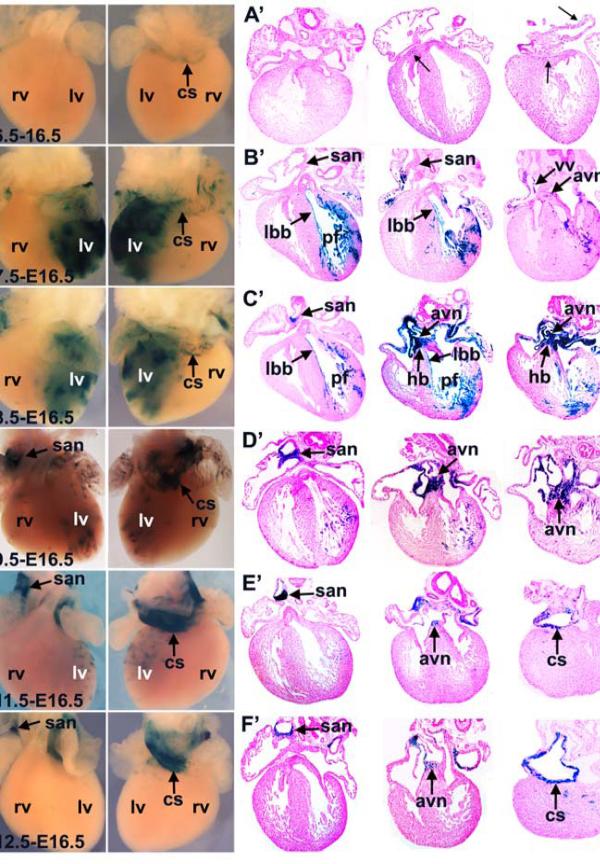

To further examine the fate of HCN4 expressing cells during development, HCN4CreERT2 mice were bred into an R26RLacZ reporter background 24. Tamoxifen inductions were performed at distinct stages of embryonic development, harvesting at E16.5 when the CCS is well defined29, 30 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. HCN4CreERT2:R26RLacZ fate mapping during heart development.

Tamoxifen was given to HCN4CreERT2;R26RLacZ pregnant females at distinct developmental stages as indicated, hearts were harvested at E16.5 and stained with X-gal. (A-F) Ventral and dorsal view; (A’-F’) serial section. A, A’) A few HCN4 lineage labeled cells (Xgal+) were found in coronary sinus (cs) and atrioventricular region (arrow) when tamoxifen induction was performed at E6.5. B, B’) Inductions at E7.5 resulted in labeling of cells in left ventricle and trabeculae/purkinje fibers (pf), left bundle branch (lbb), both atria, coronary sinus (cs), venous valves (vv), and a small number of cells in atrioventricular node (avn). A few labeled cells were also observed in the Crista terminalis (Ct), and distal tail of san. C, C’) Inductions at E8.5 resulted in a similar labeling pattern to that observed at E7.5, except that labeling of cells in san, avn and His bundle was markedly increased. D-F’) Inductions at E9.5 (D, D’), E11.5 (E, E’) and E12.5 (F, F’) resulted in selective labeling of cells in san, avn and coronary sinus. At E9.5 there was some labeling of Purkinje fibers and ventricular and atrial myocytes, which disappeared with later inductions. No significant labeling was observed in His bundle or bundle branches with inductions at these stages.

To analyze the fate of HCN4 expressing myocytes of the first heart field, HCN4CreERT2; R26RLacZ mice were fed with tamoxifen at E6.5 and E7.5. When harvested at E16.5, a few X-gal labeled cells were observed in the coronary sinus following inductions at E6.5 (Fig. 3A, A’). Inductions at E7.5 (Fig. 3B, B’) resulted in selective labeling of cells within the coronary sinus, SAN tail, venous valves, left bundle branch, Purkinje fibers, left ventricle, ventricular septum, and both atria. Infrequent labeling was also observed of Purkinje fibers within right ventricle, consistent with low levels of HCN4nLacZ/H2BGFP observed at E10.5 and E12.5 within the right ventricular trabeculae. Inductions at E8.5 (Fig. 3C, C’) labeled the foregoing populations, and in addition the SAN head, AVN, His bundle, and atrial septum. Inductions at E9.5 (Fig. 3D, D’) resulted in labeling of more restricted cell populations than at E8.5, with reduced labeling of Purkinje fibers, left ventricle, and atria, and strong labeling of the SAN, AVN, atrial septum, left superior vena cava, and the coronary sinus. Inductions at E11.5-E12.5 resulted in labeling of SAN, AVN, left superior vena cava and the coronary sinus, with few or no cells labeled in left ventricle (Fig. 3E, E’, F, F’).

Contribution of HCN4 lineages to components of the forming CCS

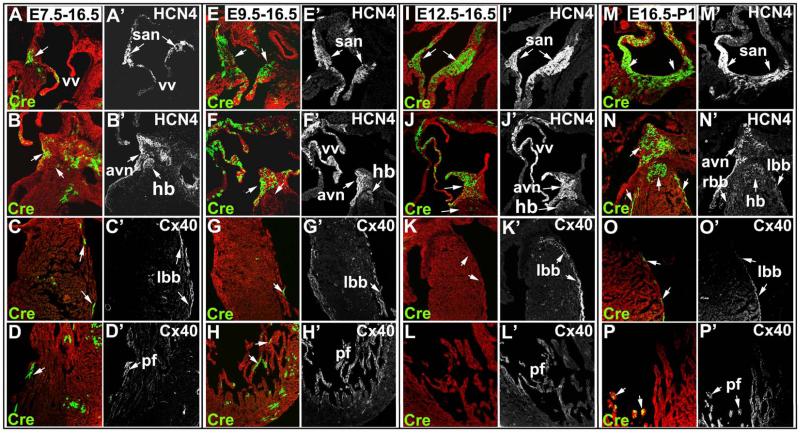

To confirm that HCN4CreERT2 lineages were giving rise to cells of the CCS, inductions were also performed in an HCN4CreERT2;Rosa-mT/mG indicator background 26 to facilitate co-immunostaining with markers of the CCS. HCN4 was used to label SAN, AVN and His-bundle, and Cx40 to label bundle branches and Purkinje fibers (Fig. 4). Inductions were performed at multiple stages, harvesting at E16.5, as previously, and gave results consistent with those with the R26RLacZ reporter.

Figure 4. HCN4CreERT2;Rosa mR/mG fate mapping and co-immunostaining with markers of CCS during heart development.

Tamoxifen was given to HCN4CreERT2;Rosa mT/mG pregnant females at distinct developmental stages as indicated. Hearts were harvested at stages indicated, and sections co-immunostained with antibody to HCN4 as a marker for sinoatrial node (san), atrioventricular node (avn) and His bundle (hb); and Cx40 as marker for His bundle and Purkinje fibers (pf) (A’-P’). A-D’) Tamoxifen induction at E7.5 resulted in labeling of cells (mGFP) in san, venous valves (vv) (A) and avn (B) as seen by co-localization with endogenous HCN4 (A’, B’). HCN4CreERT2 lineage labeled cells were also found in left bundle branch (lbb) (C) and Purkinje fibers (D) as seen by co-localization with Cx40 (C’, D’), and a subset of cells in atria (A) and left ventricle (D) that do not actively express HCN4 at E16.5. E-H’) Induction at E9.5 resulted in labeling of cells in san, venous valves (A) and avn as marked by HCN4 (E’, F’), and left bundle branch and Purkinje fibers marked by Cx40 (G’, H’). Similar to induction at E7.5, no HCN4CreERT2 lineage-labeled cells were found in right bundle branch or His-bundle (F, not shown). I-L’) Inductions at E12.5 resulted in labeling of cells in san, avn and venous valves. A few labeled cells were found in His bundle (J), but no HCN4CreERT2 lineage labeled cells were observed in left bundle branch (K) or Purkinje fibers (L). M-P’) Inductions at E16.5 and harvested at postnatal day 1 (P1) resulted in labeling of cells in all components of the CCS, including san, avn and His bundle, as marked by HCN4 (M-N’), right and left bundle branch (N-O’) and Purkinje fibers as marked by Cx40 (P, P’).

Tamoxifen induction at E7.5 resulted in labeling of cells (mGFP) in a subset of cells in SAN, venous valves, and AVN as seen by co-localization with endogenous HCN4 (Fig. 4A-B’). HCN4CreERT2 lineage labeled cells were also found in left bundle branch and Purkinje fibers as seen by co-localization with Cx40 (Fig. 4C-D’). A subset of myocytes in atria (Fig. 4A) and left ventricle (Fig. 4D) that do not actively express HCN4 at E16.5 were also labeled.

Induction at E9.5 resulted in increased labeling of cells in SAN and AVN as marked by HCN4 (Fig. 4E-F’), and labeling of left bundle branch and Purkinje fibers marked by Cx40 (Fig. 4G-H’). Similar to inductions at E7.5, no HCN4CreERT2 lineage labeled cells were found in right bundle branch and His-bundle (Fig. 4F, not shown).

Inductions at E12.5 resulted in labeling of cells in SAN, AVN, venous valves and a few cells in His bundle (Fig. 4I-J’), but no labeled cells were observed in left bundle branch or Purkinje fibers (Fig. 4K-L’). However, inductions performed at E16.5, harvesting at postnatal day 1 (P1) (Fig. 4M-P’), resulted in labeling of all components of the CCS, including those not labeled by inductions at E12.5, the His-bundle, bundle branch and Purkinje fibers (Fig. 4N-P’), demonstrating re-expression or de novo expression of HCN4 in distinct components of the CCS at later stages

Contribution of the first and second heart field to components of the CCS

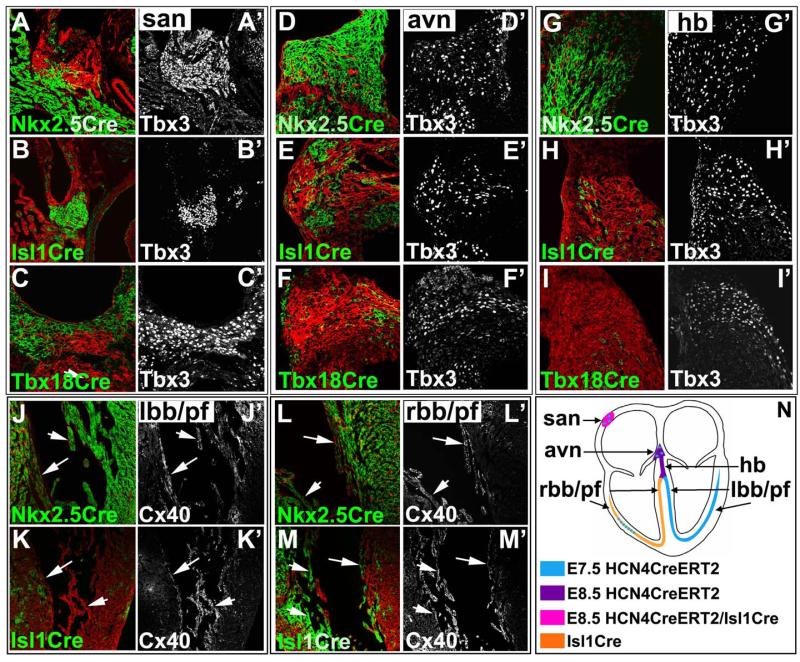

These data suggested that the earliest expression of HCN4 in the cardiac crescent and early heart tube labeled the first heart field, as HCN4 lineages were largely excluded from second heart field derived outflow tract and right ventricle. To further investigate the contribution of first and second heart lineages to the CCS, we performed lineage tracing experiments utilizing several Cre mouse lines. Nkx2.5Cre31 labels the first and second heart fields, Isl1Cre labels the second heart field17, and Tbx18Cre labels a posteriormost subset of the second heart field which will contribute to the SAN18, 19, 32. Each of these Cre was bred into the Rosa-mT/mG indicator background26 and co-immunostainings were performed at E16.5 utilizing Tbx3 to label SAN, AVN and His bundle (Fig. 5A’-I’), and Cx40 to label bundle branches and Purkinje fibers (Fig.5J’-M’).

Figure 5. Nkx2.5Cre, Isl1Cre and Tbx18Cre fate mapping to investigate lineages origins of the CCS.

Lineage tracing experiments were performed at E16.5 utilizing Cre and Rosa-mT/mG mouse lines, including Nkx2.5Cre, Isl1Cre and Tbx18Cre. Coimmunostaining was performed with antibodies to Tbx3 (A’-I’) to mark sinoatrial node (san), atrioventricular node (avn) and His bundle (hb); and Cx40 (J’-M’) to mark bundle branches (bb) and Purkinje fibers (pf). A-C’) A majority of san cells (marked by Tbx3) were derived from Isl1Cre (B) and Tbx18Cre (C) lineages (mGFP), whereas only a small subset of peripheral san cells directly adjacent to atrial myocardium was labeled by Nkx2.5Cre (mGFP) (A). D-F’) A majority of avn cells (marked by Tbx3) were derived from Nkx2.5Cre (D) lineage (mGFP), whereas only a small subset of avn cells was labeled by Isl1Cre (E), but no significant contribution of Tbx18Cre to avn was observed (F).G-I) Contribution of Nkx2.5Cre (G), Isl1Cre (H) and Tbx18Cre (I) to His bundle. J-K) Contribution of Nkx2.5Cre (J), and Isl1Cre (K) to left bundle branch (lbb) (arrow) and Purkinje fibers (arrowhead) of left ventricle. L-M) Right bundle branch (rbb) and Purkinje fibers were derived from Isl1Cre (M) and Nkx2.5Cre (L) lineages. Tbx18Cre lineages did not contribute to His bundle, bundle branches or Purkinje fibers (data not shown). N) Model for lineage derivation and timing of differentiation of CCS precursors in developing heart: The earliest HCN4 expression marks first heart field, contributing to left bundle branches, Purkinje fibers and a small subset of right Purkinje fibers (N, blue), and slightly later His bundle, avn and a small subset of san tail (N, purple and pink). In contrast, a majority of the san and right Purkinje fibers were derived from Isl1 second heart field lineages (N, pink and orange).

A majority of cells in AVN, His bundle, left bundle branch and Purkinje fibers were labeled by Nkx2.5Cre (Fig. 5D, G, J, L), whereas only a small subset of Nkx2.5Cre labeled cells were found at the boundary of the SAN and right atria (Fig. 5A’). In contrast, a majority of SAN cells were found to be Isl1Cre and Tbx18Cre labeled (Fig. 5B, C), whereas only a small subset of AVN and His bundle cells were labeled by Isl1Cre, but not by Tbx18Cre (Fig. 5E, F, H, I). A majority of cells in right bundle branches, and a substantial number of Purkinje fibers in the right ventricle were also labeled by Isl1Cre (Fig. 5K, M).

Quantitative assessment of the contribution of each lineage to distinct components of the CCS was performed (Table 1). Results of these analyses were consistent with lineage data generated by early inductions (E6.5-E8.5) of HCN4CreERT2 (Fig. 3A-C). Consistent with their derivation from the first heart field, a majority of cells within the AVN (98±1.1%), His bundle (91.4±3.5%), left bundle branch (89.8±2.5%) and Purkinje fibers were selectively labeled by Nkx2.5Cre (Table 1 and Fig. 5D, G, J, L), but not Isl1Cre (Fig. 5E, H, K, M).

Table 1.

Lineage contribution of the first and second heart field to components of the cardiac conduction system

| Isl1Cre (%) | Nkx2.5Cre (%) | Tbx18Cre (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAN head | 99.3±1.4 | 11.3±1.4 | 89.4±3.5 |

| SAN Tail | 17.6±3.2 | 54.3±5.3 | |

| AVN | 9.4±3.2 | 98±1.1 | NS |

| HB | 4.5±1.2 | 91.4±3.5 | NS |

| LBB | 6.6±2.2 | 89.8±2.5 | NS |

| RBB | 90.5±3.8 | 9.8±1.2 | NS |

| LPF | 4.5±0.5 | 92±1.8 | NS |

| RPF | 59±1.9 | 88±2.2 | NS |

Note:

* Percentages of Cre-lineage labeled cells at E16.5 in the SAN, AVN and HB were expressed as total Cre-lineage positive cells (mGFP) per area (≥10 sections per heart with significant labeling, 3-5 hearts) among total HCN4 expressing cells in the same areas.

† Percentages of Cre-lineage labeled cells in the LBB, RBB, LPF and RPF were expressed as total Cre-lineage positive cells (mGFP) per area (≥10 sections per sample, 3-5 samples) among total Cx40 expressing cells in the same areas.

‡ NS, not significant

Nkx2.5Cre lineages contributed to a small subset of cells within the SAN tail (9.4±3.2%) (Fig. 5A), consistent with labeling of these cells by early inductions of HCN4CreERT2. A majority of cells within SAN was labeled by both Isl1Cre (99.3±1.4%) and Tbx18Cre (89.4±3.5 and 54.3±5.3 in the head and tail SAN respectively) (Table 1 and Fig. 5B, C), consistent with inductions of HCN4CreERT2 at E8.5 (Fig. 3C), suggesting that, in addition to selectively marking the first heart lineage at earliest stages, by E8.5 HCN4 is also expressed in the posterior second heart field, overlapping with Isl1 in SAN precursors.

A majority of cells in the right bundle branch (90.5±3.8%) was labeled by Isl1Cre (Table 1 and Fig.5M), but was not labeled by HCN4CreERT2 at early stages (Fig. 3), confirming derivation from the second heart field. Purkinje fibers within the right ventricle arise both from second heart field and first heart field, as indicated by labeling of a subset of these cells by Isl1Cre (59±1.9%) and a subset by Nkx2.5Cre (88±2.2%), respectively (Table 1 and Fig.5L, M).

Altogether, our data suggest a model for lineage derivation and timing of differentiation of CCS precursors in developing heart, as summarized in Fig. 5N. Precursors to left Purkinje fibers, left bundle branch, and a subset of right Purkinje fibers were among first heart field myocytes marked by HCN4CreERT2 inductions at E7.5 (cardiac crescent) (blue). The foregoing CCS lineages, and precursors to the His bundle and atrioventricular node were marked by slightly later inductions of HCN4CreERT2 at E8.5 (early heart tube) (purple). With the exception of a majority of right Purkinje fibers which were marked by Isl1Cre (orange), these CCS lineages were not marked by Isl1Cre, consistent with their being derived from the first heart field. Inductions of HCN4-CreERT2 at E8.5 also marked SAN precursors, as did Isl1Cre, indicating derivation of most SAN cells from the second heart field (pink), and reflecting expression of HCN4 in SAN precursors. The right bundle branch was also derived from the second heart field, being exclusively marked by Isl1Cre (orange). A very few precursors to the SAN and AVN were labeled by inductions of HCN4CreERT2 at E7.5 (blue).

DISCUSSION

The hyperpolarization activated nucleotide gated cation channel HCN4 has been described as a marker of the pacemaker of the heart, the sinoatrial node (SAN), both during early and later development 20-22. We observed that HCN4 was expressed in the first differentiating cells of the cardiac crescent, and was expressed transiently throughout the early heart tube 23. These observations suggested that HCN4, in addition to being a marker for pacemaker cells of the heart, might be a marker of the first heart field. To further explore the significance of the dynamic expression of HCN4 during heart development and its relationship to CCS development, we generated a number of HCN4-knockin mouse lines.

Analyses with these mice, complemented by studies with other cardiac lineage-restricted Cre mice (Isl1Cre, Nkx2.5Cre, and Tbx18Cre), demonstrated that earliest expression of HCN4 marks the first heart field, in an expression domain complementary to that of Isl1. At this stage, and at later embryonic stages, HCN4 expression dynamically marks differentiated myocyte precursors of distinct components of the CCS. These precursors include those which will give rise both to working myocytes and those of the specialized conduction system, as demonstrated in previous studies 6-11. At late fetal stages (E16.5) HCN4 specifically marks all components of the CCS, being reactivated in some populations with a previous history of HCN4 expression, and activated de novo in others. These observations speak to a complex regulation of HCN4 expression during development, and it will be of great interest to investigate transcriptional regulatory mechanisms underlying this dynamic expression pattern.

Our data have given new insights into lineage origins of the CCS, and the order in which distinct precursors for each component express HCN4 and are allocated to the CCS (Fig. 5N). The earliest HCN4 expressing cells of the first heart field contribute a few cells to the SAN tail, but later HCN4 expressing cells from the posterior second heart field contribute a majority of cells to the SAN (Fig. 5N, pink). HCN4 is expressed very early in precursors of the left and a subset of right Purkinje fibers and left bundle branch (Fig. 5N, blue), and slightly later also marks precursors of the His bundle (Fig. 5N, purple), but expression within these cell populations themselves is downregulated by E11.5, with HCN4 expression remaining on only in components of the central CCS, SAN and AVN. Previous studies utilizing a Tbx2Cre allele, which demonstrated that atrioventricular canal myocardium participates in formation of the AVN, but not of the His bundle and bundle branches, indicate that AVN and His bundle do not develop from a common progenitor population, but segregate early in development 5. Our data suggest that left bundle branch precursors differentiate prior to precursors of the AVN and His bundle (Fig. 5N, blue and purple). The lineage relationship between trabecular myocardium and the Purkinje fiber network has been reaffirmed utilizing an inducible Cx40Cre which demonstrated that early trabeculae will give rise to both Purkinje fibers and working myocytes 6, 33, consistent with our observations of HCN4CreERT2 labeling both lineages. By E16.5 through adult stages, HCN4 is expressed throughout the CCS, suggesting reactivation in most components of the ventricular conduction system, and de novo activation in right bundle branch which was not significantly marked by earlier inductions of HCN4CreERT2 (Fig. 5N, orange and blue).

Our data highlight the utility of HCN4 as a marker for precursors of the CCS, but emphasize that HCN4 expression marks distinct precursors or components of the CCS at distinct times during development. Our data suggest the utility of HCN4 in conjunction with other markers to optimize protocols for the generation of specific conduction system precursors. In this context, it is also important to note that we have also observed HCN4 expression in several endothelial populations at distinct stages of development, including endothelium of the aorta and pulmonary artery, some coronary vessel endothelium, and a subset of endocardial cells (Fig. 2 and Online Figure III).

The HCN4 knockin mouse lines that we have generated should be of utility for future studies on HCN4 lineages. Although we have not observed any baseline electrophysiological phenotypes in mice which are heterozygous for HCN4, in keeping with the published literature34, heterozygosity of HCN4 should be kept in mind as a potential complicating factor when utilizing these mice, particularly in the case of ablation of other genes important for conduction system function, in light of potential genetic interactions. In experiments with HCN4CreERT2, our controls included mice both with and without tamoxifen treatment, and we did not observe leaky activity of the Cre. However, this must be kept in mind as a possibility when using these mice.

CONCLUSION

In summary, these studies have demonstrated that earliest expression of HCN4 specifically marks the first heart field, permitting early inductions of HCN4CreERT2 to shed light on cell fates adopted by the first heart field. Dynamic expression of HCN4, in concert with other lineage specific Cres, has allowed us to examine the temporal recruitment of CCS lineages, and their lineage origins, giving new insight into formation of the CCS. Additionally, our data highlight the potential of HCN4 in concert with other markers in identifying distinct CCS precursor populations, both in mouse embryos and potentially in embryonic stem cells or other pluripotent stem cells.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Cardiac arrhythmias, often consequent to abnormalities of cardiac conduction system (CCS), are one leading cause of death.

Understanding lineage origins of CCS and defining markers to identify and isolate conduction system precursors is of clinical relevance.

HCN4 is a marker of the developing cardiac pacemaker and is expressed in early differentiating cells of the cardiac crescent.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Earliest expression of HCN4 marks the first heart field.

Distinct components of the CCS derive from the first and/or second heart field.

Distinct components of the CCS express HCN4 in a temporally defined sequence, suggesting a model for progressive differentiation of distinct CCS components.

Comprehensive studies that define contributions of first and second heart field to each component of the CCS have been lacking, hampered in part by lack of a suitable marker for the first heart field. Here, we addressed the contribution of first and second heart fields to each component of the CCS, by utilizing HCN4CreERT2, in conjunction with other Cre lines, which mark the second, or first and second heart fields. Our studies identify first and second heart field contributions to each component of the CCS, and provide a new model for progressive differentiation of distinct CCS components throughout development. These studies have also highlighted the utility of HCN4, in conjunction with other markers, as a marker for precursors of each component of the CCS. The findings should greatly facilitate isolation of these cells for both basic and translational research purposes.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

SME was supported by grants from NIH. YS by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (31071280, 81171069), Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (SSTC) (10PJ1408600), the Ministry of Science and Technology China (2011CB504006, 2011DFB30010) and GBIA grant from American heart association (AHA); XL by grants from the NSFC (31171393, 81270409) and SSTC (12ZZ030, 12PJ1407400); LL by SDG (10SDG2610105) from AHA; Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope at UCSD neuroscience microscope core was purchased with grants P30 grant (NS047101)

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CCS

cardiac conduction system

- SAN (san)

sinoatrial node

- AVN (avn)

atrioventricular node

- Hb

His-bundle

- Lbb

left bundle branch

- Rbb

right bundle branch

- pf

Purkinje fiber

- Ct

crista terminalis

- Cs

coronary sinus

- Vv

venous valves

- Svc

superior vena cava

- Rv

right ventricle

- lv

left ventricle

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hirota A, Fujii S, Kamino K. Optical monitoring of spontaneous electrical activity of 8-somite embryonic chick heart. The Japanese journal of physiology. 1979;29:635–639. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.29.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamino K, Hirota A, Fujii S. Localization of pacemaking activity in early embryonic heart monitored using voltage-sensitive dye. Nature. 1981;290:595–597. doi: 10.1038/290595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Mierop LH. Location of pacemaker in chick embryo heart at the time of initiation of heartbeat. Am J Physiol. 1967;212:407–415. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.212.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viragh S, Challice CE. The development of the conduction system in the mouse embryo heart. Developmental biology. 1980;80:28–45. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90496-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aanhaanen WT, Brons JF, Dominguez JN, Rana MS, Norden J, Airik R, Wakker V, de Gier-de Vries C, Brown NA, Kispert A, Moorman AF, Christoffels VM. The tbx2+ primary myocardium of the atrioventricular canal forms the atrioventricular node and the base of the left ventricle. Circulation research. 2009;104:1267–1274. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikawa T, Fischman DA. The polyclonal origin of myocyte lineages. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:509–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pennisi DJ, Rentschler S, Gourdie RG, Fishman GI, Mikawa T. Induction and patterning of the cardiac conduction system. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46:765–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gourdie RG, Mima T, Thompson RP, Mikawa T. Terminal diversification of the myocyte lineage generates purkinje fibers of the cardiac conduction system. Development. 1995;121:1423–1431. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gourdie RG, Wei Y, Kim D, Klatt SC, Mikawa T. Endothelin-induced conversion of embryonic heart muscle cells into impulse-conducting purkinje fibers. PNAS. 1998;95:6815–6818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6815. 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyer J, Johansen M, Prasad A, Wessels A, Kirby ML, Gourdie RG, Mikawa T. Induction of purkinje fiber differentiation by coronary arterialization. PNAS. 1999;96:13214–13218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13214. 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rentschler S, Zander J, Meyers K, France D, Levine R, Porter G, Rivkees SA, Morley GE, Fishman GI. Neuregulin-1 promotes formation of the murine cardiac conduction system. PNAS. 2002;99:10464–10469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162301699. 10.1073/pnas.162301699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans SM, Yelon D, Conlon FL, Kirby ML. Myocardial lineage development. Circulation research. 2010;107:1428–1444. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyer LA, Kirby ML. The role of secondary heart field in cardiac development. Developmental biology. 2009;336:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckingham M, Meilhac S, Zaffran S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:826–835. doi: 10.1038/nrg1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meilhac SM, Esner M, Kelly RG, Nicolas JF, Buckingham ME. The clonal origin of myocardial cells in different regions of the embryonic mouse heart. Developmental cell. 2004;6:685–698. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent SD, Buckingham ME. How to make a heart: The origin and regulation of cardiac progenitor cells. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;90:1–41. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)90001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai CL, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu PH, Pfaff SL, Chen J, Evans S. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev Cell. 2003;5:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christoffels VM, Mommersteeg MT, Trowe MO, Prall OW, de Gier-de Vries C, Soufan AT, Bussen M, Schuster-Gossler K, Harvey RP, Moorman AF, Kispert A. Formation of the venous pole of the heart from an nkx2-5-negative precursor population requires tbx18. Circ Res. 2006;98:1555–1563. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227571.84189.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiese C, Grieskamp T, Airik R, Mommersteeg MT, Gardiwal A, de Gier-de Vries C, Schuster-Gossler K, Moorman AF, Kispert A, Christoffels VM. Formation of the sinus node head and differentiation of sinus node myocardium are independently regulated by tbx18 and tbx3. Circ Res. 2009;104:388–397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludwig A, Zong X, Jeglitsch M, Hofmann F, Biel M. A family of hyperpolarization-activated mammalian cation channels. Nature. 1998;393:587–591. doi: 10.1038/31255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stieber J, Herrmann S, Feil S, Loster J, Feil R, Biel M, Hofmann F, Ludwig A. The hyperpolarization-activated channel hcn4 is required for the generation of pacemaker action potentials in the embryonic heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15235–15240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434235100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moorman AF, Christoffels VM. Cardiac chamber formation: Development, genes, and evolution. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1223–1267. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Frigola C, Shi Y, Evans SM. Expression of the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel hcn4 during mouse heart development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:777–783. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00125-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soriano P. Generalized lacz expression with the rosa26 cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, Lein ES, Zeng H. A robust and high-throughput cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Y, Liang X, Najafi N, Cass M, Lin L, Cai CL, Chen J, Evans SM. Islet 1 is expressed in distinct cardiovascular lineages, including pacemaker and coronary vascular cells. Dev Biol. 2007;304:286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hadjantonakis AK, Papaioannou VE. Dynamic in vivo imaging and cell tracking using a histone fluorescent protein fusion in mice. BMC Biotechnol. 2004;4:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-4-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rentschler S, Vaidya DM, Tamaddon H, Degenhardt K, Sassoon D, Morley GE, Jalife J, Fishman GI. Visualization and functional characterization of the developing murine cardiac conduction system. Development. 2001;128:1785–1792. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.10.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viswanathan S, Burch JB, Fishman GI, Moskowitz IP, Benson DW. Characterization of sinoatrial node in four conduction system marker mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moses KA, DeMayo F, Braun RM, Reecy JL, Schwartz RJ. Embryonic expression of an nkx2-5/cre gene using rosa26 reporter mice. Genesis. 2001;31:176–180. doi: 10.1002/gene.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai CL, Martin JC, Sun Y, Cui L, Wang L, Ouyang K, Yang L, Bu L, Liang X, Zhang X, Stallcup WB, Denton CP, McCulloch A, Chen J, Evans SM. A myocardial lineage derives from tbx18 epicardial cells. Nature. 2008;454:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature06969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miquerol L, Beyer S, Kelly RG. Establishment of the mouse ventricular conduction system. Cardiovascular research. 2011;91:232–242. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoesl E, Stieber J, Herrmann S, Feil S, Tybl E, Hofmann F, Feil R, Ludwig A. Tamoxifen-inducible gene deletion in the cardiac conduction system. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2008;45:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.