Abstract

Prior work shows developmental cannabinoid exposure alters zebra finch vocal development in a manner associated with altered CNS physiology, including changes in patterns of CB1 receptor immunoreactivity, endocannabinoid concentrations and dendritic spine densities. These results raise questions about the selectivity of developmental cannabinoid effects: are they a consequence of a generalized developmental disruption, or are effects produced through more selective and distinct interactions with biochemical pathways that control receptor, endogenous ligand and dendritic spine dynamics? To begin to address this question we have examined effects of developmental cannabinoid exposure on the pattern and density of expression of proteins critical to dendritic (MAP2) and axonal (Nf-200) structure to determine the extent to which dendritic vs. axonal neuronal morphology may be altered. Results demonstrate developmental, but not adult cannabinoid treatments produce generalized changes in expression of both dendritic and axonal cytoskeletal proteins within brain regions and cells known to express CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Results clearly demonstrate that cannabinoid exposure during a period of sensorimotor development, but not adulthood, produce profound effects upon both dendritic and axonal morphology that persist through at least early adulthood. These findings suggest an ability of exogenous cannabinoids to alter general processes responsible for normal brain development. Results also further implicate the importance of endocannabinoid signaling to peri-pubertal periods of adolescence, and underscore potential consequences of cannabinoid abuse during periods of late-postnatal CNS development.

Keywords: Nf-200, MAP2, dendritic spines, cannabinoid, vocal development, neuronal morphology

1. Introduction

It has become clear that cannabinoid signaling plays an important modulatory role in establishing neuronal connectivity and morphology both during development and as a function of experience (reviewed by Soderstrom and Gilbert, 2012). This includes regulation of axonal migration (Berghuis et al., 2007) and dendritic structure (Hill et al., 2012). A distinct behavioral sensitivity to cannabinoid exposure during limited periods of peri-adolescent development is also now well-documented (reviewed by Schneider, 2008; Soderstrom and Gilbert, 2012) but physiological mechanisms responsible for these persistent, developmental effects on behavior remain poorly understood.

Zebra finch vocal learning is controlled by a well-characterized set of discrete, interconnected brain regions (reviewed by Mooney, 2009) that distinctly and densely express CB1 cannabinoid receptors (Soderstrom et al., 2004; Soderstrom and Tian, 2006). As vocal development in these animals depends upon both successful progress through a sensitive period of development, and also sensorimotor practice and experience, we have hypothesized that previously-established cannabinoid-altered vocal learning (Soderstrom and Johnson, 2003; Soderstrom and Tian, 2004) may be attributable to disruption of endocannabinoid control of associated changes in neuronal morphology. This hypothesis is supported by evidence that developmental cannabinoid exposure persistently alters CB1 receptor staining patterns and endocannabinoid levels in the CNS, and densities of dendritic spines within at least some brain regions important to song learning and control (Gilbert and Soderstrom, 2011; Soderstrom and Tian, 2008; Soderstrom et al., 2011). Importantly, all of these effects are restricted to developmental exposure, and are not produced by similar treatment of adults. Altered neuronal morphology following developmental cannabinoid treatment may be due to selective pharmacological disruption of biochemical processes, such as those controlling dendritic spine dynamics (Frost et al., 2010), or may be due to interaction with more general, non-selective or activity-dependent developmental mechanisms. Experiments described herein were designed to begin to address these possibilities.

Using antibodies against structural, cytoskeleton-associated proteins with expression largely restricted to dendrites (MAP2, Huber and Matus, 1984) or axons (Nf-200, Marszalek et al., 1996) we studied expression patterns and densities as a function of developmental vs. adult treatments. This permitted generalized changes in dendritic and/or axonal neuronal structures to be appreciated. Treatment differences were observed within several song control regions of zebra finch telencephalon important to vocal learning and production.

2. Results

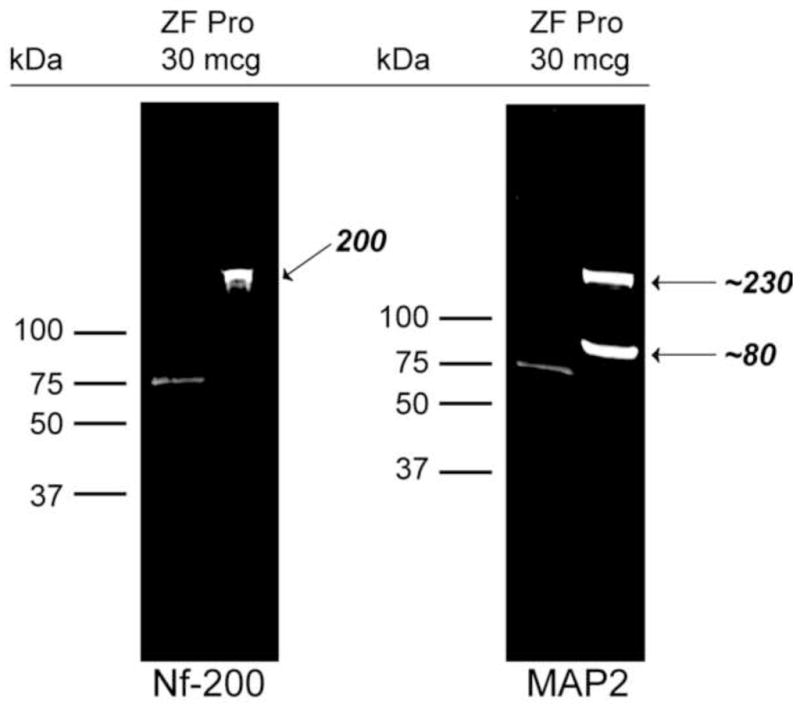

2.1 Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed to assess the selectivity of the monoclonal antibodies directed against the two neurocytoskeletal proteins used in immunohistochemistry experiments. SDS-PAGE separation of 30 μg of brain cytoskeletal fractions revealed the presence of a single predominant band of approximately 200 kDa labeled by the anti-phosphorylated Nf-200 antibody (Fig. 1) Two predominant protein bands consistent with high-molecular weight isoforms of MAP2 (MAP2a and MAP2b, at approximately 230 kDa), and the lower molecular weight isoforms of MAP2 (MAP2c and MAP2d, at approximately 80 kDa) were labeled by the anti-MAP2 antibody used. The sizes of these selectively labeled proteins are similar to those reported from other mammalian species, including mouse, rat, horse and human (Alexanian et al., 2008; Russo et al., 2012; Saraceno et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Western blotting demonstrates selectivity of Nf-200 and MAP2 antibody interactions with zebra finch brain proteins. Following separation and transfer of 30 μg zebra finch protein to membranes and exposure to NF-200 and MAP2 antibodies, near IR-labeling of bands of expected sizes were observed with very little background. Molecular weight markers were run in left lanes, and 75 kDa bands are apparent. Arrows indicate bands of expected size for both phosphorylated Nf-200 (~ 200 kDa) and MAP2 that consists of two alternative splicing isoforms of ~ 80 and 230 kDa (Loveland et al., 1999).

2.2 Patterns of Nf-200 staining

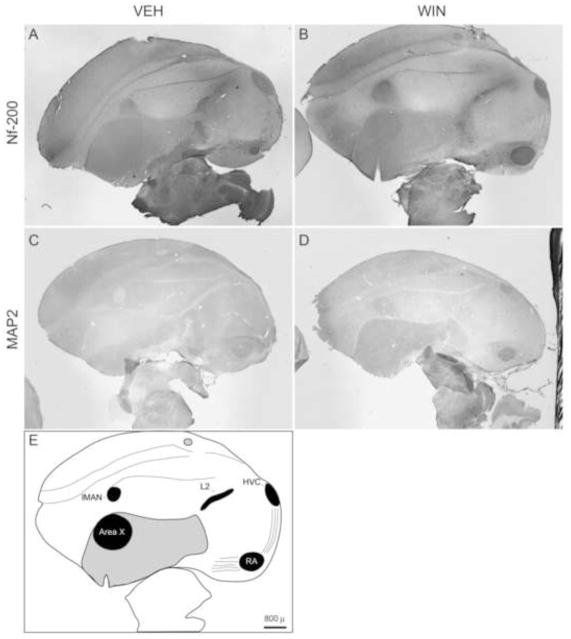

Regions of telencephalon (HVC used as a proper name, robust nucleus of arcopallium [RA], lateral magnocellular nucleus of anterior nidopallium [lMAN], Area X of striatum [Area X]); thalamus (nucleus ovoidalis [Ov], medial portion of the dorsolateral thalamus [DLM]); and cerebellum (CER) were studied. General Nf-200 staining patterns, and relative anatomical positions of the telencephalic song regions studied (HVC, RA, lMAN, Area X) are illustrated as a function of developmental treatments in Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

(A–D) Representative 12.5 X images of parasagittal sections stained with anti-Nf-200 and MAP2 antibodies following developmental VEH and WIN treatments. Low-power magnification allows appreciation of general staining patterns. (E) Diagrammatical representation of the section shown in Panel A. A subset of telencephalic song regions evaluated are labeled (lMAN, Area X, HVC, RA). Striatum is shaded in grey. Rostral is left, ventral top. Bar = 800 μ.

2.2.1 Song Regions within Caudal Telencephalon

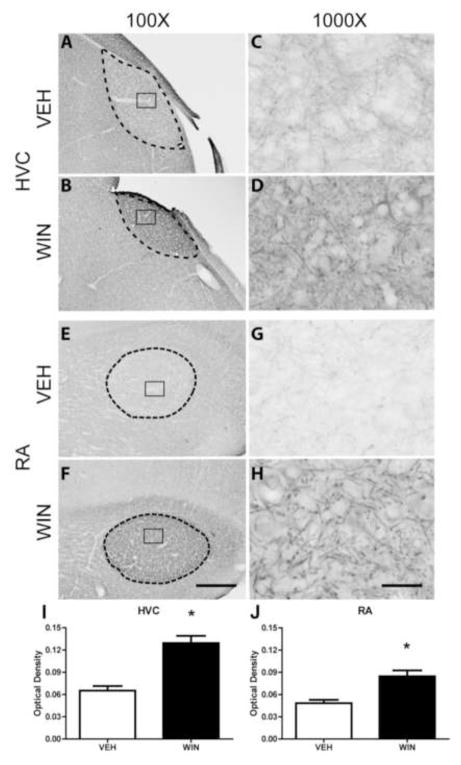

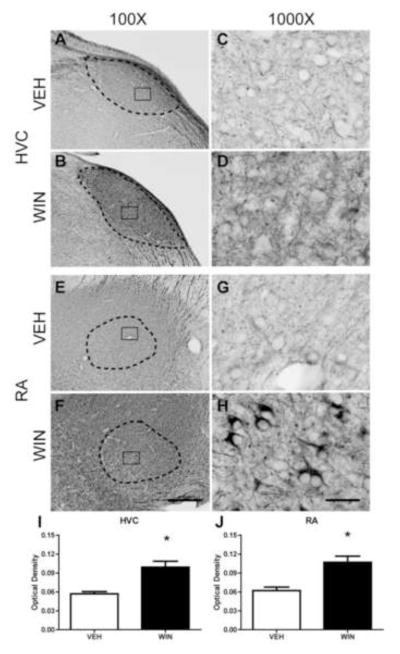

Distinct, dense Nf-200 staining patterns were observed within HVC, relative to that seen within surrounding regions of nidopallium (see Fig. 3A and B) of animals treated with vehicle during sensorimotor development. At 1000X, the presence of long, thin neuronal processes were detected with the Nf-200 antibody used. We observed little Nf-200 neuropil staining, therefore separate fibers measuring approximately 0.5 – 1 μm in diameter were easier to detect (Fig. 3C). In HVC of developmentally WIN-treated animals, Nf-200 protein appeared to be more densely expressed, and more intensely stained (compare Fig. 3A and B). Staining intensity within HVC of treated animals was increased to the point it was difficult to distinguish distinct cell bodies from surrounding neuropil (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Axonal Nf-200 staining in song regions of caudal telencephalon as a function of developmental treatments. HVC is a pre-motor region that projects to vocal-motor RA. WIN or VEH was administered daily for 25 days during the sensorimotor period of vocal development. Following treatments, birds were allowed to mature to adulthood (110 days). WIN treatments increased densities of anti-phosphorylated Nf-200 staining in both HVC (compare panels A and B) and RA (compare panels E and F). Staining patterns remained similar in HVC (compare C and D). The pattern of staining of axonal terminals surrounding unstained cells was dramatically increased in RA (compare G and H). Optical density measurements confirmed WIN-associated density increases in both regions (panels I and J). 100X scale bar = 300 μm, 1000X scale bar = 30 μm.

In the caudal arcopallial region RA, however, differences in patterns of phosphorylated Nf-200 staining between both VEH and WIN developmentally treated groups were more grossly apparent. Thick axonal projections emanating from HVC appeared to terminate within subregions of RA. Nf-200 staining was noted throughout the entire arcopallium, however staining was generally heavier within RA itself (see Fig. 3E and F). Light perisomal Nf-200 expression was evident within RA of vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 3G). However, in animals treated developmentally with WIN, Nf-200-labeled fibers appeared thicker (Fig. 3H). Within RA, axon terminals surrounding the cell bodies appeared to contain large amounts of phosphorylated Nf-200 (Fig. 3H).

2.2.2 Song Regions within Rostral Telencephalon

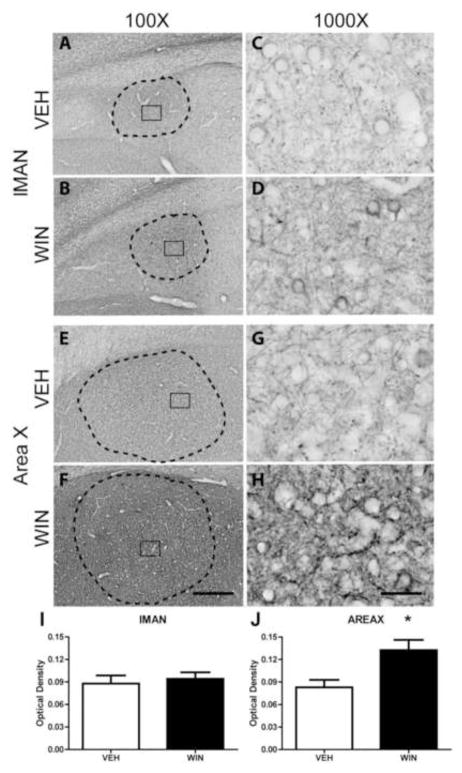

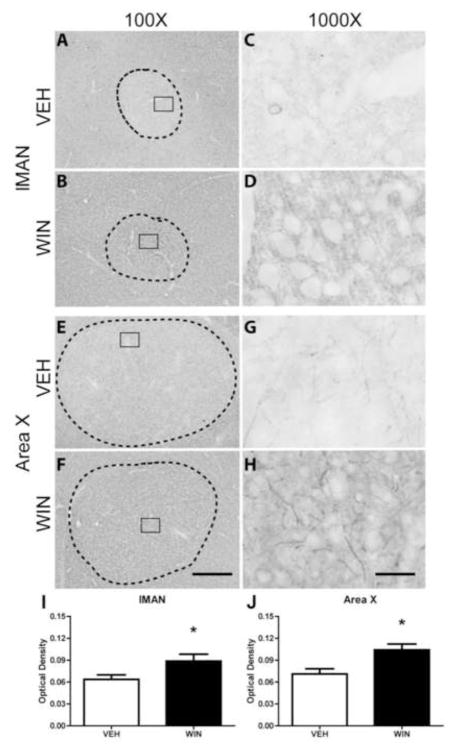

Within lMAN, distinct Nf-200 staining was apparent, but was not restricted to the boundaries of this region within nidopallium (Fig. 4A and B). Staining was of diffuse neuropil, fibers, and peri-somatic structures, giving the region an overall “scratched” appearance. Compared to tissue from VEH-treated animals, WIN exposure during development resulted in an apparent, but not statistically significant, increase in phosphorylated Nf-200 protein within lMAN (Fig. 4I, and compare 4C and D).

Figure 4.

Axonal Nf-200 staining in song regions of rostral telencephalon as a function of developmental treatments. Both lMAN and Area X are essential for vocal learning, but are not required for adult production of learned song. WIN or VEH was administered daily for 25 days during the sensorimotor period of vocal development. Following treatments, birds were allowed to mature to adulthood (110 days). WIN treatments altered the pattern of anti-phosphorylated Nf-200 staining within lMAN (compare panels C and D) by increasing axonal terminal staining surrounding unstained cells. A similar, but more dramatic pattern was observed in Area X (panels G and H). Despite apparent differences in staining patterns within lMAN, overall optical density of staining did not vary as a function of treatment (panel I). Intensity of staining was significantly increased following WIN treatment within Area X (panel J), although this increase did not appear restricted to the song region, but appeared to occur generally throughout striatum (panel F). 100X scale bar = 300 μm, 1000X scale bar = 30 μm.

Area X and surrounding striatum were also positive for Nf-200 staining (Fig 4E, F). At 1000X under vehicle control conditions, Nf-200 expression patterns appeared similar to that of HVC; distinctly long, thin processes, light perisomatic expression, and very little neuropil staining were observed (see Fig. 4E, G). However, in animals treated developmentally with WIN, markedly-increased densities of neuropil staining were noted with thicker, more fragmented axons (compare Fig. 4G and H).

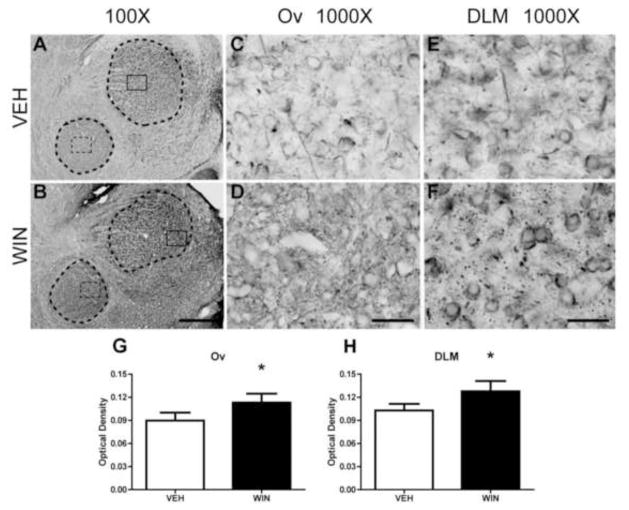

2.2.3 Thalamic Regions Related to Vocal Development

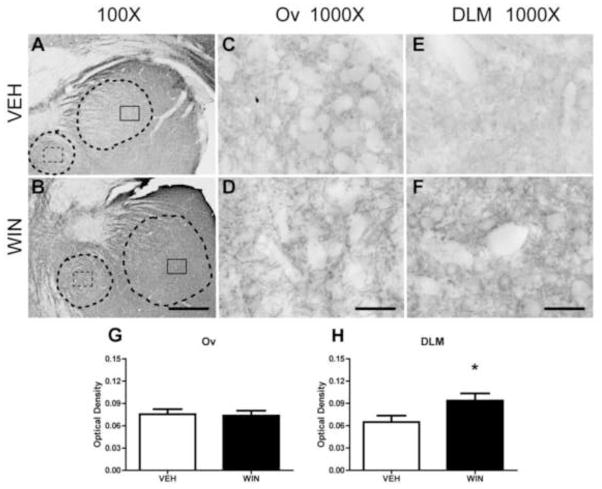

Anti-Nf-200 staining of thalamic regions DLM and Ov are illustrated in Fig. 5. As DLM (the larger, dorsal region outlined in panels A and B) receives input from Area X and projects to lMAN, it is part of a basal ganglia circuit important to vocal learning (Luo and Perkel, 1999). Ov (the smaller, ventral region outlined in panels A and B) projects to auditory Field L2 and NCM, and receives input from the midbrain nucleus mesencephalicus lateralis pars dorsalis (MLd, thought to be the avian homologue of mammalian inferior colliculus) and RA, implicating a role in auditory and sensorimotor feedback (Amin et al., 2010). General staining patterns of thalamic regions Ov and DLM were similar to HVC in that Nf-200 staining was distinctly expressed within these regions relative to background. Within Ov, under vehicle control conditions, neuropil staining was low with some distinct long, thin fibers consistent with axons and their terminals surrounding unstained cells (Fig. 5A, dashed box inset and Fig. 5C). Administration of WIN during development resulted in considerable increases in Ov neuropil expression (Fig 5D). Many thicker, irregularly-stained fibers surrounding unstained somata were observed likely representing terminals of axons arriving from either MLd or RA (see Fig. 5B, dashed box and Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Axonal Nf-200 staining in thalamic song regions as a function of developmental treatments. As DLM (the larger, dorsal region outlined in panels A and B) receives input from Area X and projects to lMAN, it is essential for vocal learning (Luo and Perkel, 1999). Ov (the smaller, ventral region outlined in panels A and B) projects to auditory Field L2 and NCM, and receives input from MLd and RA, implicating a role in auditory feedback necessary for sensorimotor learning (Amin et al., 2010). Basal expression is remarkable for sparse axonal fibers terminating on unstained somata. In Ov (panel C) these may be terminals projecting from MLd or RA. Within DLM (panel E) fiber terminals likely emanate from Area X. Following WIN treatments, notable, interesting patterns of stained puncta, possible fibers perpendicular to the plane of section, become apparent within both regions (compare C to D, and E to F). OD measures confirm a modest increase in staining intensity within both regions (panels G and H). 100X scale bar = 300 μm, 1000X scale bar = 30 μm.

Within DLM (Fig. 5E and F) staining patterns following vehicle treatments were similar to those within Ov, with the addition of increased frequency of distinct puncta, possibly representing Nf-200-expressing axons traveling perpendicular to the plane of section. These puncta became more pronounced in WIN-treated animals, as did perisomatic staining of axon terminals (likely arriving from Area X) surrounding unstained cells (likely cell bodies of neurons projecting to lMAN, Fig. 5F).

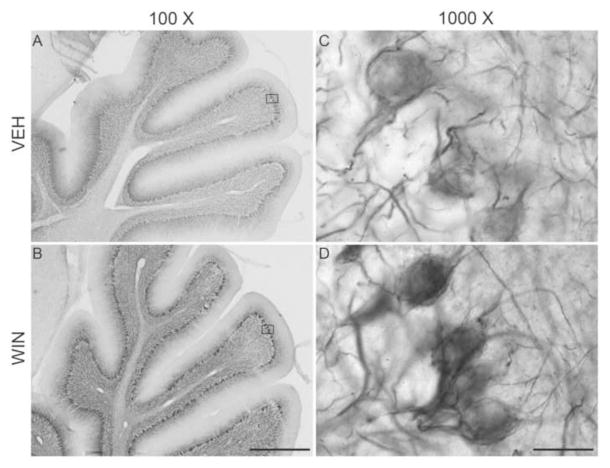

2.2.4 Cerebellum

Although cerebellum has not been established to play a clear role in vocal development, there is limited evidence that it does influence brain regions important to song learning (Person et al., 2008). Cerebellum is particularly relevant to cannabinoid pharmacology as it expresses distinctly high densities of CB1 receptors (Herkenham et al., 1991; Soderstrom and Tian, 2006). These receptors are present within basket cell neurons that project to Purkinje cells, and also are evenly distributed throughout the molecular layer, likely expressed by granule cell axons that form parallel fibers terminating on Purkinje cell dendrites (Egertova and Elphick, 2000). Because of dense receptor expression within a structure with known circuitry that is well-conserved across vertebrates, we have included cerebellum in these studies. Given the heterogeneous nature of cerebellum, comprised of granule cell, Purkinje cell and molecular layers, OD comparisons are difficult. However, expression patterns can be appreciated. Dendritic MAP2 staining was generally light in cerebellum, and less remarkable than axonal anti-Nf-200 staining. Therefore we present and focus on the staining patterns of Nf-200 in this cannabinoid-relevant region (see Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Representative images of DAB-immunohistochemical staining of phosphorylated Nf-200 protein within the cerebellum of adult male zebra finches developmentally treated with either vehicle (Panel A, inset C) or WIN (1 mg/kg, Panel B, inset D). Heterogeneity of granule cell, Purkinje cell and molecular layers precluded OD analysis of this region, however patterns of staining can be appreciated. Staining within both the molecular and Purkinje cell layers appear dense after developmental cannabinoid treatment (Panel B, inset D) relative to that of vehicle-treated animals (Panel A, inset C). Particularly distinct is staining of transverse axons within a region of the molecular layer bordering Purkinje cells consistent with basket cell axons. Fibers impinging upon and surrounding Purkinje cells are also notable following developmental WIN treatments. As most input to Purkinje cell somata is from inhibitory basket cell neurons, it is likely that dense staining is associated with these GABAergic terminals. 100X scale bar = 300 μm, 1000X scale bar = 30 μm.

The Nf-200 antibody prominently stained axons within all three cerebellar layers (Fig. 6). In the molecular layer, fiber staining was restricted to regions proximal to the Purkinje cell layer, occupying about a third of the layer (Fig 6A and B). This localization is consistent with the staining of basket cell axons that run parallel to, and terminate on Purkinje cell somata. In VEH-treated animals, stained fibers appeared to surround unstained Purkinje cell bodies (Fig. 6C). This staining pattern appeared more pronounced following developmental WIN treatments (Fig. 6D).

2.2.5 Nf-200 Optical Densities

In this study, two-way ANOVA revealed that developmental treatment with the cannabinoid agonist WIN during periods of sensorimotor learning resulted in a significant increase in anti-Nf-200 staining intensities as compared to vehicle-treated groups (F(1,393) = 31.070, p < 0.001). Further Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc analyses revealed that these differences lie within the caudal regions HVC (from vehicle control mean OD = 0.0569 ± .004 to 0.099 ± 0.010 in WIN-treated subjects, q = 4.343, p = 0.002), RA (from vehicle control mean OD = 0.062 ± 0.010 to 0.107 ± 0.010 in animals treated with WIN, q = 4.602, p = 0.001), rostral region Area X (from vehicle-treated control mean OD = 0.083 ± 0.010 to 0.132 ± 0.014, WIN-treated mean, q = 4.945, p < 0.001) and midbrain thalamic regions Ov (from vehicle-treated control mean OD = 0.089 ± 0.010 to 0.113 ± 0.012 WIN-treated mean, q = 4.836, p < 0.001) and DLM (from vehicle-treated control mean OD = 0.103 ± 0.009 to 0.130 ± 0.013, WIN-treated mean, q = 4.906, p < 0.001). Importantly, when administered to adults that had already completed vocal development, cannabinoid treatments did not produce significant differences in optical densities of Nf-200 staining (F(1,384) = 0.049, p = 0.825) within any of the analyzed telencephalic areas or thalamic regions DLM and Ov (images not shown).

2.3 Patterns of MAP2 staining

In general, we noted a similarity in MAP2 staining patterns across all telencephalic regions under vehicle-treated conditions, regardless of whether treatments were administered during development or to adults. This pattern was characterized by light, diffuse neuropil staining that was often lighter than that of the non-song regions surrounding areas of interest (e.g. lMAN, Area X and HVC, Fig. 2C).

2.3.1 Song Regions of Caudal Telencephalon

MAP2 staining was observed within both HVC and RA of vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 7). In the case of HVC, this staining appeared distinctly lower than that of surrounding nidopallium. This gave rise to a negative staining appearance that clearly contrasted with that of Nf-200 staining in caudal telencephalon. Upon closer inspection, clear neuropil staining was noted (Fig. 7C and G). Following developmental WIN treatments, staining intensities within both HVC and RA were increased. These increases were characterized by distinct fiber, neuropil and puncta staining (Fig. 7D and H). Analysis of OD measures confirmed increased staining intensities following WIN treatment (Fig. 7I and J).

Figure 7.

Dendritic MAP2 staining in song regions of caudal telencephalon as a function of developmental treatments. HVC is a pre-motor region that projects to vocal-motor RA. WIN treatments increased densities of MAP2 staining in both HVC (compare panels A and B) and RA (compare panels E and F). Staining patterns changed as a function of WIN treatment (compare C and D) with increased frequency of fibers surrounding unstained somata and stained puncta. These WIN-induced differences were more prominent within RA (compare G and H). Optical density measurements confirmed WIN-associated density increases in both regions (panels I and J). 100X scale bar = 300 μm, 1000X scale bar = 30 μm.

2.3.2 Song Regions within Rostral Telencephalon

In lMAN, immunostaining for MAP2 was limited to neuropil in both control and WIN-treated animals (Fig 8C and D). This neuorpil staining appeared to surround large, unstained somata and was increased in intensity following developmental WIN treatments (Fig. 8I). Staining within Area X was also characterized by neuropil staining, but also included staining of distinct fibers, sometimes surrounding large unstained somata. Developmental WIN treatments also increased the density of Area X neuropil staining (Fig. 8J, compare 8G and H).

Figure 8.

Dendritic MAP2 staining in song regions of rostral telencephalon as a function of developmental treatments. Both lMAN and Area X are essential for vocal learning, but are not required for adult production of learned song. VEH treatments were associated with song region staining intensities lower than that of surrounding areas (compare A with B and E with F). In lMAN, WIN treatments increased intensity of neuropil staining surrounding large unstained somata (compare C and D). A similar increase in neuropil was also observed in Area X, with additional staining of distinct fibers. WIN-increased staining intensities were confirmed by OD measurements (panels I and J). 100X scale bar = 300 μm, 1000X scale bar = 30 μm.

2.3.3 Thalamic Regions Related to Vocal Development

MAP2 staining of thalamic regions DLM and Ov are illustrated in Fig 9. DLM is the larger, ventral-caudal region with solid line inset; Ov is the smaller rostral-ventral region with dashed line inset. Anti-MAP2 staining patterns were similar across groups with diffuse neuropil observed occasionally around unstained somata. In the case of animals treated developmentally with WIN, staining intensities were significantly increased (Fig. 9G and H).

Figure 9.

Dendritic MAP2 staining in thalamic song regions as a function of developmental treatments. As DLM (the larger, dorsal region outlined in panels A and B) receives input from Area X and projects to lMAN, it is essential for vocal learning (Luo and Perkel, 1999). Ov (the smaller, ventral region outlined in panels A and B) projects to auditory Field L2 and NCM, and receives input from MLd and RA, implicating a role in auditory feedback necessary for sensorimotor learning (Amin et al., 2010). Basal expression is remarkable for sparse neuropil, in the case of Ov that surrounds unstained somata (panels C and E). Following WIN treatments, in Ov fiber and punctate staining appear more prominent (panel D). In DLM, a more general increase in diffuse neuropil staining is evident. OD measures confirm a modest increase in staining intensity within DLM (panel H). 100X scale bar = 300 μm, 1000X scale bar = 30 μm.

2.3.4 MAP2 Optical Densities

Comparisons of the vehicle-control group treated during development with those that were administered WIN revealed a significant increase in MAP2 immunoreactivity (F (1,384) = 48.097, p < 0.001). Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc analyses revealed differences lie within all four of the telencephalic song regions (HVC, from 0.065 ± 0.000 to 0.130 ± 0.010, RA, from 0.049 ± 0.010 to 0.085 ± 0.010, Area X, from 0.071 ± 0.007 to 0.104 ± 0.008, and lMAN, from 0.064 ± 0.007 to 0.089 ± 0.010, results summarized in Fig. 7 and 8). In addition, we observed significant differences in levels of MAP2 staining within DLM (from vehicle-control mean 0.065 ± 0.009 to 0.094 ± 0.010 in treated animals), but not within Ov. Importantly, following treatments administered to adults that had completed vocal development, no differences in optical densities of MAP2 immunoreactivity were found (F (1,419) = 0.546, p = 0.580, images not shown).

3. Discussion

The results of the experiments reported herein indicate that repeated developmental exposure to cannabinoids during a critical period for sensorimotor learning leads to persistent, gross morphological changes in the expression of axonal marker Nf-200, and dendritic marker MAP2. This study focused on songbird CNS regions previously shown to express CB1 cannabinoid receptors at high levels: HVC, RA, lMAN, Area X, Ov, DLM, and cerebellum (Soderstrom et al., 2004; Soderstrom and Tian, 2006). These results suggest that increased cannabinoid receptor activation significantly alters the morphological features of neurons located within many of these regions that are critical for zebra finch development of stereotyped song. This work represents the first attempt to identify persistent morphological correlates within zebra finch song regions associated with developmental cannabinoid treatments known to cause persistent disruptions in adult singing behavior (Soderstrom and Johnson, 2003; Soderstrom and Tian, 2004).

Our approach in using dendritic and axonal markers as indicators of drug effects on neuronal morphology is not novel. Others have used anti-Nf-200 antibodies to demonstrate that chronic morphine and cocaine exposure reduces expression of this axonal protein within rat ventral tegmentum, but not substantia nigra (Beitner-Johnson et al., 1992). More recently, both Nf-200 axonal and MAP2 dendritic expression have been used to demonstrate that chronic cannabinoid treatments increase expression of both markers in several rat brain regions, including frontal cortex, hippocampal CA1, medial striatum, and cerebellum (Tagliaferro et al., 2006). Thus, our results contribute to accumulating evidence that CNS-active drugs of abuse have potential to generally alter neuronal morphology.

It should be noted that both of these prior studies employed rats of about 40 to 45 days of age. Rats of this age are pubertal and still developing. This rat pubertal development proceeds on a time course similar to that of zebra finches, where mature adulthood is reached by about 90 days (Adriani and Laviola, 2004; Spear, 2000). Thus, prior rat experiments were done using developing animals, during a roughly similar period of late-postnatal development as the zebra finches employed in the developmental studies described here. Therefore, evidence for the ability of CNS-active drugs of abuse to alter axonal and dendritic structures is restricted to studies of peri-pubescent, adolescent animals. Our work represents the first to directly compare cannabinoid effects on neuronal morphology as a function of adolescent vs. mature adult chronic exposures. Thus, this is the first demonstration of developmental effects that are not produced following adult treatments. As birds learn song during this drug-sensitive period, they provide an additional opportunity to study drug effects within the context of an ethologically-relevant, critical period of learning.

3.1 MAP2 staining patterns

MAP2 has long been appreciated to have an important role in CNS development through the regulation and stabilization of other cytoskeletal proteins important for extension and maintenance of dendritic structure (Sanchez et al., 2000). MAP2 expression is associated with the “bundling” of microtubules (Burgin et al., 1994) that promotes stiffening of dendritic structures (Matus, 1994). Thus, increased MAP2 expression following developmental, but not adult, cannabinoid treatments within learning-essential song regions (lMAN, Area X, DLM) and vocal-motor regions (HVC and RA) may indicate inappropriately stabilized dendritic structures. As CNS development is characterized by initial profusion of synaptic connections, followed by learning- and experience-promoted refinement, it is likely that inappropriate stabilization will interfere with these processes (Luo and O’Leary, 2005). Thus, previously documented cannabinoid-altered vocal development may involve, and be attributable to, a lack of activity-dependent, learning-related refinement of synaptic connections (Soderstrom and Johnson, 2003; Soderstrom and Tian, 2004). This is consistent with our earlier finding that dendritic spine densities within HVC and Area X are elevated following developmental, but not adult WIN exposure (Gilbert and Soderstrom, 2011).

In contrast to patterns of Nf-200 staining (discussed in detail below) treatment-related differences in MAP2 expression were generally more modest and more related to intensity than pattern. Notable treatment effects on MAP2 staining include distinctly increased densities in each of the telencephalic song regions assessed including caudal HVC and RA (Fig. 7) and rostral lMAN and Area X (Fig 8). Interestingly, staining intensities within these regions following vehicle treatments appeared lower than that of surrounding areas. This gave a “negative staining” appearance to the telencephalic song regions of control animals. This suggests that low MAP2 expression is a property of song control regions, which implies reduced dendritic stability relative to that of other regions. Developmental WIN treatments increased MAP2 staining intensities to levels approximating those of surrounding regions (Fig. 8). Within caudal regions HVC and RA, developmental WIN treatments resulted in a change from negative staining to intensities greater than surrounding nidopallium and arcopallium, respectively (Fig. 7). The significance of these differential effects in rostral vs. caudal song regions remain unknown, but may have some relationship to learning (rostral lMAN and Area X) vs. vocal-motor (caudal HVC and RA) roles of these regions.

3.2 Nf-200 staining patterns

We used an anti-Nf-200 antibody as a marker for changes in axonal morphology as the protein it targets is selectively enriched within axons, particularly those of large caliber, characteristic of projection neurons (Trojanowski et al., 1986). Axon caliber is positively regulated by Nf-200 expression (Hoffman et al., 1987) suggesting that increased expression observed following developmental cannabinoid treatments may promote a general increase in axon diameter and conduction efficiency. The antibody used here and also by others (Beitner-Johnson et al., 1992) selectively labels the phosphorylated form of the protein. Thus, increased densities of expression may be attributable to either increased de novo expression and post-translational phosphorylation or increased phosphorylation of existing pools of inactive protein, or perhaps combinations of both. Whichever case applies, as the active phosphorylated form of Nf-200 is the one relevant to increased axon caliber (de Waegh et al., 1992; Mata et al., 1992) its use was most appropriate to investigate effects on axon morphology.

Increased Nf-200 staining following developmental, but not adult treatments, was observed within learning-associated song regions Area X and DLM (but not lMAN), and vocal-motor HVC and RA. It may be the case that during normal development Nf-200 expression within these brain regions is distinctly elevated, as interconnections between nuclei of the song system are established and mature. This is seen with developmental expression of CB1 cannabinoid receptors that peaks during periods of sensorimotor learning (50 – 75 days of age) and then wanes to adulthood (by 100 days of age, Soderstrom and Tian, 2006). Preliminary results indicate that a similar pattern of Nf-200 expression may occur over normal development, suggesting cannabinoid exposure inhibits normal decreases. Evidence for cannabinoid inhibition of normal CNS developmental processes, and interference with associated morphological change is accumulating for several signaling systems (Soderstrom and Gilbert, 2012).

3.2.1 Nf-200 staining pattern within cerebellum

Changes in Nf-200 staining patterns following developmental treatments were distinct within cerebellum. Although a clear role for cerebellum in vocal development has not been established, given known distinct and dense CB1 receptor expression and well-characterized circuitry, study of the structure is warranted here. The Nf-200 antibody distinctly labeled fibers within all three layers of cerebellum, but most densely stained a network of fibers running parallel with and proximal to the Purkinje cell layer extending through about third of the molecular layer (see Fig. 6). These fibers appeared to surround and terminate upon Purkinje cell bodies in a manner and with anatomy consistent with axons of CB1 receptor-expressing, GABAergic basket cells (Elphick and Egertova, 2001). Labeling of these fibers appeared more distinct in animals treated developmentally with WIN (Fig. 6D). This suggests that axons of densely CB1-expressing cell types like cerebellar basket cells are subject to persistent morphological change following developmental cannabinoid exposure. Increased basket cell Nf-200 expression suggests greater axon diameters and increased efficiency of inhibitory input to Purkinje cells.

Presynaptic CB1 receptor localization on Nf-200-expressing GABAergic basket cell terminals explains established neurophysiological effects of endocannabinoid signaling to produce Purkinje cell depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI, reviewed by Diana and Marty, 2004). Purkinje cell depolarization results in calcium-dependent release of the endogenous cannabinoid, 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG, Bisogno et al., 2003). Released 2-AG freely diffuses to presynaptic CB1-expressing inhibitory terminals and activates cannabinoid receptors. Cannabinoid receptor-induced signaling reduces presynaptic calcium concentrations, decreasing the probability of inhibitory transmitter release, which in this circuit, further potentiates Purkinje cell activation. Thus, potential increased axon bore and efficiency of GABAergic transmission following increased Nf-200 expression is likely to antagonize this normal DSI-mediated feed-forward amplification of activation, potentially interfering with endocannabinoid modulation of normal cerebellar function (Tanimura et al., 2009). This hypothesis is consistent with recent diffusion-fMRI evidence correlating white matter alterations and reduced cerebellar activity in adult patients with histories of heavy adolescent Cannabis abuse (Lopez-Larson et al., 2012; Zalesky et al., 2012).

3.2.2 Nf-200 Staining Patterns within Rostral Telencephalic Song Regions

As noted previously, the song regions Area X and lMAN are essential for vocal learning, but are not necessary for production of adult song (Bottjer et al., 1984; Sohrabji et al., 1990). Within Area X, increased staining included that of perisomatic fibers, but also appeared as a general enhanced labeling of neuropil (see Fig. 4H). This increased neuropil staining is consistent with that of cerebellum described above, and may involve glutamatergic palliostriatal inputs to Area X spiny interneurons known to be subject to endocannabinoid modulation (Thompson and Perkel, 2011). The effect of increasing this transmission would be similar to that proposed within in cerebellum; to antagonize endocannabinoid-mediated modulatory feedback, but in this case ultimately augmenting excitatory input and thus interneuron activity within Area X. Because increased staining intensities were observed throughout striatum, and were not restricted to only the song region, cannabinoid-altered activity likely occurs throughout the entire striatum. This suggests additional non-vocal development-related processes are likely also influenced by developmental cannabinoid treatments. In other species, regions of striatum are notably involved in control of motor behavior and reward, which are both learning-essential processes (Wickens, 1990). Given the relevance of zebra finch striatum to vocal learning, and marked avian/mammalian similarities in dopaminergic input from midbrain regions (e.g. ventral tegmentum and substansia nigra, Gale and Perkel, 2006) cannabinoid-altered axonal morphology may generally influence reward-motivated learning and motor behaviors, a hypothesis supported by accumulating evidence generated through developmental studies employing peri-pubertal rodents (reviewed by Schneider, 2008).

Within lMAN, in contrast to effects to elevate MAP2 expression, developmental cannabinoid treatments did not significantly alter measures of Nf-200 staining density. At high-power magnification, subtle increases in fiber staining, particularly that surrounding large, unstained somata were observed (see Fig. 4D). This suggests that developmental treatments may have some effect on activity within lMAN that is perhaps less robust than within other telencephalic song regions. There is evidence that lMAN activity is more important to early, auditory learning stages of vocal development (Livingston and Mooney, 1997). Thus, it may be the case that sensitivity of lMAN to developmental effects of cannabinoids will be greater earlier stages of song learning, a hypothesis that warrants testing.

3.2.3 Nf-200 Staining Within Song Regions of Caudal Telencephalon

Developmental cannabinoid treatments were associated with dramatically increased Nf-200 staining intensities within the pre-vocal motor song region HVC (Fig. 3D). HVC is comprised of three populations of neurons: those that project to the vocal-motor output, RA; those that project to the learning essential Area X of striatum; and modulatory interneurons (Daou et al., 2013). The pattern of increased HVC staining consisted primarily of neuropil consistent with labeling of interneuron axons. This suggests that activity of HVC interneurons may be most subject to developmental cannabinoid effects. As HVC both responds to auditory stimuli (Vates et al., 1996) and initiates vocal-motor output (Vu et al., 1994), altered interneuron activity likely interferes with the auditory-motor integration function of this region in a manner consistent with cannabinoid-altered vocal development.

The pattern of increased Nf-200 staining within the vocal-motor output region RA also included neuropil, but more notably included fibers terminating on and surrounding large unstained somata (Fig. 3H). These terminals appear of fibers emanating from HVC (Fig 2A, B and 3A, B and E) but known afferents from lMAN cannot be ruled-out (Bottjer et al., 1984). The large diameters of these cells surrounded by Nf-200 expressing terminals (>10 μ) suggests they are cell bodies of projection neurons. Thus, it is expected that increased efficiency of Nf-200 expressing axon terminals may be associated with increased vocal motor output. We know that acute cannabinoid exposure effectively decreases vocal-motor activity (Soderstrom and Johnson, 2003), but we have not investigated the amount of singing done following chronic, vocal development-altering treatments. This question merits investigation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1 Materials

Except where noted, all materials and reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Immunochemicals were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burligame, CA). The primary anti-phosphorylated Nf-200 and MAP2 monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Sigma (N1042 and M9942, St. Louis, MO). Equithesin was prepared from reagents (40 % propylene glycol, 10 % ETOH, 5 % chloral hydrate, 1 % pentobarbital). The synthetic cannabinoid agonist WIN55212-2 (WIN) was suspended in vehicle from concentrated DMSO stocks (10 mM). Vehicle consisted of a suspension of 1:1:18 DMSO:Alkamuls EL-620 (Rhodia, Cranberry, NJ):phosphate-buffered saline.

4.2 Animals

Both juvenile and adult male zebra finches bred and raised in our aviary were used as subjects in these experiments. From three days prior to the start of experiments until the end of experiments, birds were housed singly in visual isolation with free access to grit, water, mixed seeds (Sunseed Vita Finch), and cuttlebone, and provided multiple perches. Animals were maintained on a 14:10 light/dark cycle, and ambient temperature was maintained at 78° F. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of East Carolina University.

4.3 Treatments

This study employed two age groups: (1) a developmental treatment group where young animals received daily injections of either VEH or WIN during sensorimotor vocal development from 50 to 75 days of age and; (2) an adult group that was administered the same daily treatments for 25 days as adults after prior completion of vocal development. After completion of the daily treatment regimen, both groups were allowed to develop an additional 25 days. This maturation period allowed developmental subjects to reach adulthood. Thus, treatment effects observed were persistent for at least 25 days, and lasted to adulthood. Also, all analyses were done on tissue taken from adult animals.

Once daily drug treatments of either vehicle or WIN were administered via 50 μl IM injections into either the right or left pectoralis muscle for 25 consecutive days, 30 minutes before lights on. For animals in the developmental group, these treatments started at 50 days of age, and ended at 75 days. Adult group animals were given the same regimen, with injections beginning after maturation (> 100 days of age). Injection sites were alternated daily (e.g. day 1 right muscle, day 2 left muscle) in an effort to minimize damage to the skin, protect the administration route, and maximize comfort. This cannabinoid treatment given during the zebra finch sensorimotor period from 50 to 75 days alters song learning and vocal development (Soderstrom and Johnson, 2003; Soderstrom and Tian, 2004). Following the completion of treatments, animals were allowed to mature to at least 110 days of age in visual isolation.

4.4 Western Blotting

The presence of phosphorylated Nf-200 and MAP2 protein was detected within the zebra finch brain by using mouse monoclonal antibodies targeting phosphorylated Nf-200 and MAP2, respectively. Protein extraction protocols were adapted from methods described by Schafer et al., 1998. Adult male zebra finches, subjected to song stimulation procedures described below, were killed by Equithesin overdose. Brains were removed, homogenized with a polytron in an ice-cold extraction buffer containing 1 M Tris-HCl, pH = 7.0, 0.6 M KCl, 0.5 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM MgCl2, along with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (0.25 M sucrose/1 mM EDTA/4 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/1 mM 4-amino benzamidine/0.1 % w/v bacitracin), and briefly micro-centrifuged at 1000 x g. Supernatants were stirred on ice for 30 min, collected and centrifuged at 24,000 x g. Following this, supernatants were ultra-centrifuged at 100,000 x g for 1 hour. Pellets were discarded and supernatants were filtered through cheesecloth to remove traces of excess lipid, and dialyzed against 10 L of ice-cold distilled water for 4 hours at 4° C. The fractions were then dialyzed overnight against two changes of ice-cold extraction buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM ATP, 0.1 mM DTT, 100 mM KCl, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Samples were centrifuged a final time at 24,000 x g at 4° C to remove trace precipitate. Supernatants were collected and protein concentrations determined using the Bradford method. 30 μg of soluble protein was loaded into a 10 % polyacrylamide gel, separated by SDS-PAGE, and blotted onto a PVDF membrane. Blots were blocked with a non-mammalian blocking reagent (Odyssey Blocking Buffer, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and incubated overnight at 4° C in a 1:1500 dilution of the phosphorylated Nf-200 or MAP2 antibodies in Odyssey Blocking Buffer. The next day, blots were washed three times with 1X PBS-T (Phosphate-Buffered Saline [pH = 7.4] with 0.05 % Tween-20), and incubated in secondary antibody solutions containing an infrared anti-mouse secondary antibody at 1:25,000 (IR Dye 800CW Goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L), LI-COR Biosciences # 926-32210) and 0.02 % SDS for 2 hours at room temperature in the dark. The blots were washed 4 times with 1X PBS (Phosphate-Buffered Saline [pH = 7.4]) for 10 minutes each, and visualized using the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. Masses of infrared bands were determined via standard curves fit to distances migrated by molecular weight standards using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

4.5 Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemical methods used in this study were adapted from Soderstrom and Tian, 2006. After the birds reached either maturation of at least 110 days, or the end of experiments, animals were killed by Equithesin overdose (50 μl), PBS transcardially perfused, followed by phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (pH = 7.0). Brains were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, and then transferred to an ice-cold 20 % sucrose solution the next morning, in preparation for histological analyses. Once tissues sank in the sucrose solution, brains were blocked down the midline and sectioned parasagittally, using a vibrating microtome (Leica VT 1000s, Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove IL). Tissue was briefly rinsed in 1X PBS for 10 minutes followed by incubation in 1 % H2O2 for 30 minutes, to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were again rinsed 3 times with 1X PBS, and then blocked with 5 % normal goat serum for 35 minutes. Following blocking, sections were incubated overnight at room temperature in a solution containing primary antibody (1:5000 dilution), 1 % normal goat serum, 0.01 % sodium azide, and 0.3 % Triton-X 100 in PBS. The following day, tissues were rinsed three times in PBS and incubated in a biotinylated anti-mouse antiserum for 60 minutes followed by an avidin-biotin complex solution (ABC Elite kit, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA). Presence of antibody was visualized using a 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. DAB solution was inactivated by three washes in 1X PBS. Tissue sections were mounted on glass slides coated with 0.3 % gelatin. After sections on slides were allowed to dry overnight, sections were dehydrated with graded concentrations of ethanol (70 %, 95 %, and 100 % respectively), cleared with xylenes, and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher).

4.6 Optical Density Measurements

Immunohistochemical staining was examined in various brain regions at 40, 100, and 1000 X using an Olympus BX51 microscope with Nomarski DIC optics. For measurements, images were captured at 100 X using a Spot Insight QE digital camera and Image-Pro Plus 5.0 software (MediaCybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) under identical, calibrated exposure conditions. All images were background-corrected, and converted to 8-bit grey scale; borders that outlined brain regions of interest were traced manually. Two-dimensional optical density measurements of both labeled processes from areas enclosed within traced areas were performed on images without knowledge of treatment condition for each brain region of interest. With the exception of heterogeneous cerebellum, all intact sections containing brain regions of interest were included for analysis, and analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 5.0 software. Mean optical densities (within brain region counts of stained nuclei and neuropil/area of the region) were compared across each treatment group using two-way ANOVA as described below.

4.7 Statistical Methods

All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistically significant differences between groups were assessed by the Student’s t-test; relationships between optical densities and drug treatments were assessed through two-way ANOVA with brain region (HVC, RA, lMAN, Area X, DLM, Ov) and treatment (vehicle vs. 1 mg/kg WIN) as factors. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed probability of less than 0.05. Results pertaining to the hypothesis tested (that drug treatment would alter phosphorylated Nf-200 and/or MAP2 protein expression) were presented in our analysis of data. After a significant treatment effect was determined by two-way ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc tests were performed. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0, SigmaStat, and Microsoft Excel PC software.

5. Conclusions

We have found that developmental cannabinoid treatments persistently alter patterns and densities of expression of both dendritic (MAP2) and axonal (Nf-200) markers. Altered expression was evident within brain regions important to zebra finch vocal learning and production, and in some cases surrounding areas also. These results demonstrate a generalized ability of repeated cannabinoid exposure to alter neuronal morphology when administered during periods of peri-pubertal, adolescent development. Importantly, these changes were not observed following the same treatments administered to adults. These findings add to accumulating evidence that adolescent cannabinoid exposure interferes with normal processes of late-postnatal CNS development, and suggests a mechanism responsible for persistent behavioral effects following early chronic Cannabis abuse.

Highlights.

Expression of axonal Nf-200 and dendritic MAP2 markers are studied in zebra finch brain

Cannabinoid exposure increases staining following developmental, but not adult treatments

Effects are seen within several brain regions important to vocal learning and production

Results indicate early cannabinoid exposure generally alters neuronal morphology

Developmentally-selective effects may explain cannabinoid alerted vocal development

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01DA020109.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- Adriani W, Laviola G. Windows of vulnerability to psychopathology and therapeutic strategy in the adolescent rodent model. Behav Pharmacol. 2004;15:341–52. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexanian AR, Maiman DJ, Kurpad SN, Gennarelli TA. In vitro and in vivo characterization of neurally modified mesenchymal stem cells induced by epigenetic modifiers and neural stem cell environment. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:1123–30. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin N, Gill P, Theunissen FE. Role of the zebra finch auditory thalamus in generating complex representations for natural sounds. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:784–98. doi: 10.1152/jn.00128.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitner-Johnson D, Guitart X, Nestler EJ. Neurofilament proteins and the mesolimbic dopamine system: common regulation by chronic morphine and chronic cocaine in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2165–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02165.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghuis P, Rajnicek AM, Morozov YM, Ross RA, Mulder J, Urban GM, Monory K, Marsicano G, Matteoli M, Canty A, Irving AJ, Katona I, Yanagawa Y, Rakic P, Lutz B, Mackie K, Harkany T. Hardwiring the brain: endocannabinoids shape neuronal connectivity. Science. 2007;316:1212–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1137406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Howell F, Williams G, Minassi A, Cascio MG, Ligresti A, Matias I, Schiano-Moriello A, Paul P, Williams EJ, Gangadharan U, Hobbs C, Di Marzo V, Doherty P. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:463–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottjer SW, Miesner EA, Arnold AP. Forebrain lesions disrupt development but not maintenance of song in passerine birds. Science. 1984;224:901–3. doi: 10.1126/science.6719123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgin KE, Ludin B, Ferralli J, Matus A. Bundling of microtubules in transfected cells does not involve an autonomous dimerization site on the MAP2 molecule. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:511–7. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.5.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daou A, Ross M, Johnson F, Hyson RL, Bertram R. Electrophysiological characterization and computational models of HVC neurons in the zebra finch. J Neurophysiol. 2013 doi: 10.1152/jn.00162.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waegh SM, Lee VM, Brady ST. Local modulation of neurofilament phosphorylation, axonal caliber, and slow axonal transport by myelinating Schwann cells. Cell. 1992;68:451–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90183-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertova M, Elphick MR. Localisation of cannabinoid receptors in the rat brain using antibodies to the intracellular C-terminal tail of CB. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422:159–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000626)422:2<159::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elphick MR, Egertova M. The neurobiology and evolution of cannabinoid signalling. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:381–408. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost NA, Kerr JM, Lu HE, Blanpied TA. A network of networks: cytoskeletal control of compartmentalized function within dendritic spines. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:578–87. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale SD, Perkel DJ. Physiological properties of zebra finch ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra pars compacta neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2295–306. doi: 10.1152/jn.01040.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MT, Soderstrom K. Late-postnatal cannabinoid exposure persistently elevates dendritic spine densities in Area X and HVC song regions of zebra finch telencephalon. Brain Res. 2011;1405:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci. 1991;11:563–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00563.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MN, Kumar SA, Filipski SB, Iverson M, Stuhr KL, Keith JM, Cravatt BF, Hillard CJ, Chattarji S, McEwen BS. Disruption of fatty acid amide hydrolase activity prevents the effects of chronic stress on anxiety and amygdalar microstructure. Mol Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman PN, Cleveland DW, Griffin JW, Landes PW, Cowan NJ, Price DL. Neurofilament gene expression: a major determinant of axonal caliber. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:3472–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber G, Matus A. Differences in the cellular distributions of two microtubule-associated proteins, MAP1 and MAP2, in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1984;4:151–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-01-00151.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston FS, Mooney R. Development of intrinsic and synaptic properties in a forebrain nucleus essential to avian song learning. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8997–9009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-08997.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Larson MP, Rogowska J, Bogorodzki P, Bueler CE, McGlade EC, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Cortico-cerebellar abnormalities in adolescents with heavy marijuana use. Psychiatry Res. 2012;202:224–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland KL, Herszfeld D, Chu B, Rames E, Christy E, Briggs LJ, Shakri R, de Kretser DM, Jans DA. Novel low molecular weight microtubule-associated protein-2 isoforms contain a functional nuclear localization sequence. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19261–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, O’Leary DD. Axon retraction and degeneration in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:127–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Perkel DJ. A GABAergic, strongly inhibitory projection to a thalamic nucleus in the zebra finch song system. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6700–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06700.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek JR, Williamson TL, Lee MK, Xu Z, Hoffman PN, Becher MW, Crawford TO, Cleveland DW. Neurofilament subunit NF-H modulates axonal diameter by selectively slowing neurofilament transport. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:711–24. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata M, Kupina N, Fink DJ. Phosphorylation-dependent neurofilament epitopes are reduced at the node of Ranvier. J Neurocytol. 1992;21:199–210. doi: 10.1007/BF01194978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus A. Stiff microtubules and neuronal morphology. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:19–22. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney R. Neurobiology of song learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:654–60. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person AL, Gale SD, Farries MA, Perkel DJ. Organization of the songbird basal ganglia, including area X. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:840–66. doi: 10.1002/cne.21699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo D, Castellani G, Chiocchetti R. Expression of high-molecular-mass neurofilament protein in horse (Equus caballus) spinal ganglion neurons. Microsc Res Tech. 2012;75:626–37. doi: 10.1002/jemt.21102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C, Diaz-Nido J, Avila J. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) and its relevance for the regulation of the neuronal cytoskeleton function. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:133–68. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraceno GE, Ayala MV, Badorrey MS, Holubiec M, Romero JI, Galeano P, Barreto G, Giraldez-Alvarez LD, Kolliker-Fres R, Coirini H, Capani F. Effects of perinatal asphyxia on rat striatal cytoskeleton. Synapse. 2012;66:9–19. doi: 10.1002/syn.20978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DA, Jennings PB, Cooper JA. Rapid and Efficient Purification of Actin from Nonmuscle Sources. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1998;39:166–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)39:2<166::AID-CM7>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. Puberty as a highly vulnerable developmental period for the consequences of cannabis exposure. Addict Biol. 2008;13:253–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Johnson F. Cannabinoid exposure alters learning of zebra finch vocal patterns. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;142:215–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(03)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Tian Q. Distinct periods of cannabinoid sensitivity during zebra finch vocal development. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;153:225–32. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Tian Q, Valenti M, Di Marzo V. Endocannabinoids link feeding state and auditory perception-related gene expression. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10013–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3298-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Tian Q. Developmental pattern of CB1 cannabinoid receptor immunoreactivity in brain regions important to zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) song learning and control. J Comp Neurol. 2006;496:739–58. doi: 10.1002/cne.20963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Tian Q. CB(1) cannabinoid receptor activation dose dependently modulates neuronal activity within caudal but not rostral song control regions of adult zebra finch telencephalon. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:265–73. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1190-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Poklis JL, Lichtman AH. Cannabinoid exposure during zebra finch sensorimotor vocal learning persistently alters expression of endocannabinoid signaling elements and acute agonist responsiveness. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom K, Gilbert MT. Cannabinoid mitigation of neuronal morphological change important to development and learning: Insight from a zebra finch model of psychopharmacology. Life Sci. 2012;92:467–75. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabji F, Nordeen EJ, Nordeen KW. Selective impairment of song learning following lesions of a forebrain nucleus in the juvenile zebra finch. Behav Neural Biol. 1990;53:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(90)90797-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–63. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliaferro P, Javier Ramos A, Onaivi ES, Evrard SG, Lujilde J, Brusco A. Neuronal cytoskeleton and synaptic densities are altered after a chronic treatment with the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212–2. Brain Res. 2006;1085:163–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura A, Kawata S, Hashimoto K, Kano M. Not glutamate but endocannabinoids mediate retrograde suppression of cerebellar parallel fiber to Purkinje cell synaptic transmission in young adult rodents. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JA, Perkel DJ. Endocannabinoids mediate synaptic plasticity at glutamatergic synapses on spiny neurons within a basal ganglia nucleus necessary for song learning. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:1159–69. doi: 10.1152/jn.00676.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowski JQ, Walkenstein N, Lee VM. Expression of neurofilament subunits in neurons of the central and peripheral nervous system: an immunohistochemical study with monoclonal antibodies. J Neurosci. 1986;6:650–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-03-00650.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vates GE, Broome BM, Mello CV, Nottebohm F. Auditory pathways of caudal telencephalon and their relation to the song system of adult male zebra finches. J Comp Neurol. 1996;366:613–42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960318)366:4<613::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu ET, Mazurek ME, Kuo YC. Identification of a forebrain motor programming network for the learned song of zebra finches. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6924–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06924.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens J. Striatal dopamine in motor activation and reward-mediated learning: steps towards a unifying model. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1990;80:9–31. doi: 10.1007/BF01245020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalesky A, Solowij N, Yucel M, Lubman DI, Takagi M, Harding IH, Lorenzetti V, Wang R, Searle K, Pantelis C, Seal M. Effect of long-term cannabis use on axonal fibre connectivity. Brain. 2012;135:2245–55. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]