Abstract

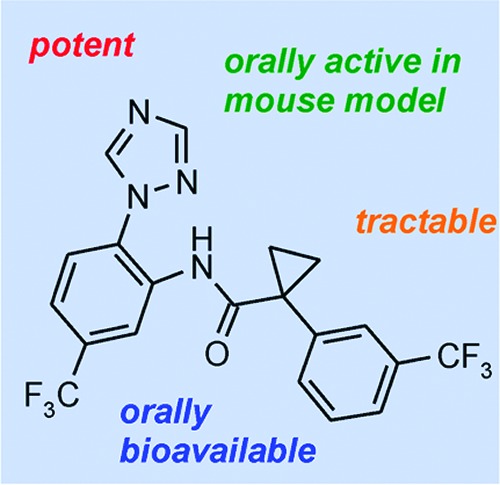

Rapid triaging of three series of related hits selected from the Tres Cantos Anti-Malarial Set (TCAMS) are described. A triazolopyrimidine series was deprioritized due to delayed inhibition of parasite growth. A lactic acid series has derivatives with IC50 < 500 nM in a standard Plasmodium falciparumin vitro whole cell assay (Pf assay) but shows half-lives of < 30 min in both human and murine microsomes. Compound 19, from a series of cyclopropyl carboxamides, is a highly potent in vitro inhibitor of P. falciparum (IC50 = 3 nM) and has an oral bioavailability of 55% in CD-1 mice and an ED90 of 20 mg/kg after oral dosing in a nonmyelo-depleted P. falciparum murine model.

Keywords: TCAMS, Tres Cantos Anti-Malarial Set, malaria, cyclopropyl, carboxamide, triazole, oral bioavailability, in vivo activity, murine, Plasmodium falciparum, Medicines for Malaria Venture

Each year, approximately 250 million people are affected by malaria, and around 800 000 people die. The disease particularly affects children under 5 and pregnant women1 and is particularly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa where the economic and humanitarian burden is considerable.1 Malaria is caused by parasites of the genus Plasmodium with Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax being predominantly responsible for the highest mortality and highest morbidity, respectively.2 Despite approved treatments for malaria such as quinine (1), chloroquine (2), coartem [a combination of artemether (3) and lumefantrine (4)], and malarone [atovaquone (5) and proguanil (6) combination] (structures provided in the Supporting Information), the development of clinically resistant P. falciparum strains compromises treatment. Artemisinin-resistant strains are now also beginning to emerge.2 In 2007, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation supported by other global health organizations initiated a malaria eradication agenda;2 the combination of resistance and the eradication agenda means that there remains an urgent need for new antimalarial medicines. Among several compounds under development, tafenoquine (7), an analogue of primaquine that originated from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, is an 8-aminoquinoline being developed by GSK in conjunction with Medicines for Malaria Venture as a radical cure of P. vivax.

A recent review describes medicinal chemistry progress toward new antimalarial medicines,3 while a drug candidate for malaria from an oxaborole series4 has been announced in the last year. Numerous chemotypes have also been published, a selection of which include naphthoquinones,5 nucleosides,6 ureas,7 and endoperoxide-falcipain.8

In recent years, Novartis,9 Guy at St. Jude's Hospital Memphis,10 and GlaxoSmithKline11 have made major contributions toward the search for new antimalarial medicines by publishing new antimalarial hit structures. GSK published over 13,000 confirmed hits, which inhibit parasite growth by at least 80% at 2 μM concentration; these are known as the Tres Cantos Antimalarial Compounds Set (TCAMS).11 More than 8,000 show activity against the multidrug-resistant P. falciparum Dd2 strain.11 This is a substantial number of new chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Both structures and screening data are available online for public download from the European Bioinformatics Institute at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/chemblntd. TCAMS came from screening over 2 million compounds in the GSK corporate collection, and more than 80% of these are previously proprietary molecules. By putting these structures into the public domain, GSK hopes to contribute toward stimulating additional research into the development of new antimalarial medicines.

With over 13,000 starting points for new antimalarials, it is both a tremendous opportunity and also a challenge to identify those starting points with the highest quality. Our initial process involved various computational clustering and filtration techniques and is described elsewhere.12 From this process, we detail here several series of carboxamides as the first report for progressing hits identified from TCAMS.

One of the significant benefits of these carboxamide series is that analogues are readily prepared in very few steps. The compounds described were commercially available or readily assembled from commercially available acids and anilines using standard amide coupling procedures via the appropriate acid chloride or using coupling reagents. The heterocyclic substituents were introduced by copper(I) iodide-mediated coupling of the appropriate aryl bromide and the heterocycle often with 8-hydroxyquinoline catalysis (see the Supporting Information).

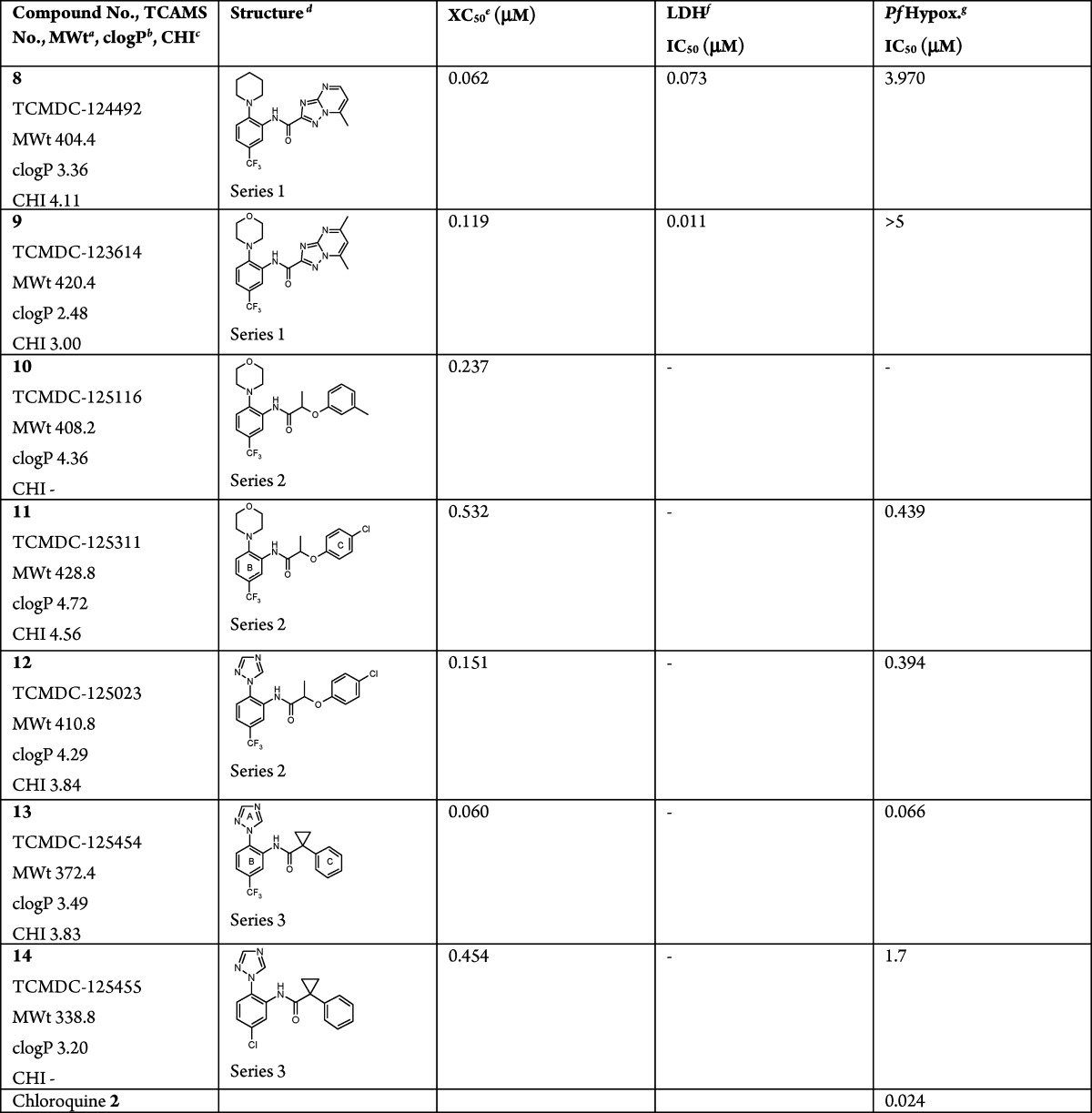

Different assays were used to assess in vitro growth inhibition of P. falciparum 3D7 parasites. The high-throughput screen (HTS) used to identify TCAMS compounds used parasite lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) as a surrogate of Plasmodium growth.11 Estimates of compound concentration producing 50% inhibition of parasite growth were obtained for TCAMS using 5-fold dilutions down to 3 nM, and these values are designated as “XC50’s” (Table 1).11 IC50 values that were more accurately determined than XC50 values were calculated from full dose–response curves using 3-fold dilution and are designated LDH IC50 values (Table 1).11 The standard 3H-hypoxanthine whole cell assay (abbreviated to Pf assay) was used to generate IC50 values for the determination of structure–activity relationship (SAR) (Tables 1–3).13 Most of the compounds described herein showed no or very little activity against mammalian cells in a standard cytotoxicity assay using a HepG2 cell line that is a widely used in vitro marker for liver toxicity (data not shown).14

Table 1. Three Related Carboxamide Hit Series.

Molecular weight.

Calculated using Daylight software.

A lipophilicity value measured at pH 7.4 (see the Supporting Information).

Where applicable, all compounds are racemic.

The XC50 was derived from a 5-fold dilution protocol of the LDH assay as described in ref (11).

See ref (11) for experimental details of the LDH assay.

P. falciparum3H-hypoxanthine assay (see the Supporting Information for experimental details and standard deviations).

Table 3. Physicochemical and in Vitro Profiles of 13 and 19.

| property/assaya | 13 | 19 |

| MWt | 372.4 | 440.3 |

| clog P | 3.49 | 4.38 |

| CHI | 3.83 | 4.25 |

| Pf IC50 (μM) | 0.066 | 0.003 |

| cP450b (μM) | >10c | >10d |

| hERGe (μM) | >50 | >50 |

| CLND solubilityf (μM) | 100 | 9 |

| permeability (nM/s) | 240 | |

| mouse ppbg (%) | 99.0 | 99.4 |

| human ppb (%) | 99.0 | |

| cross-screening | inactive in 44/45 assaysh | inactive in 43/45 assaysi |

See previous tables for definitions of abbreviations.

P450s tested were 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4.

Except for 2C9 7.9 μM.

Except for 2C9 6.3 μM.

Dofetilide binding assay.

Chemiluminescent nitrogen detection—a turbimetric assay from DMSO solution.

Ppb is a plasma protein binding.

A 2.5 μM activity observed against the PXR receptor.

A 0.3 and 1 μM activity observed against PDE4B and the PXR receptor.

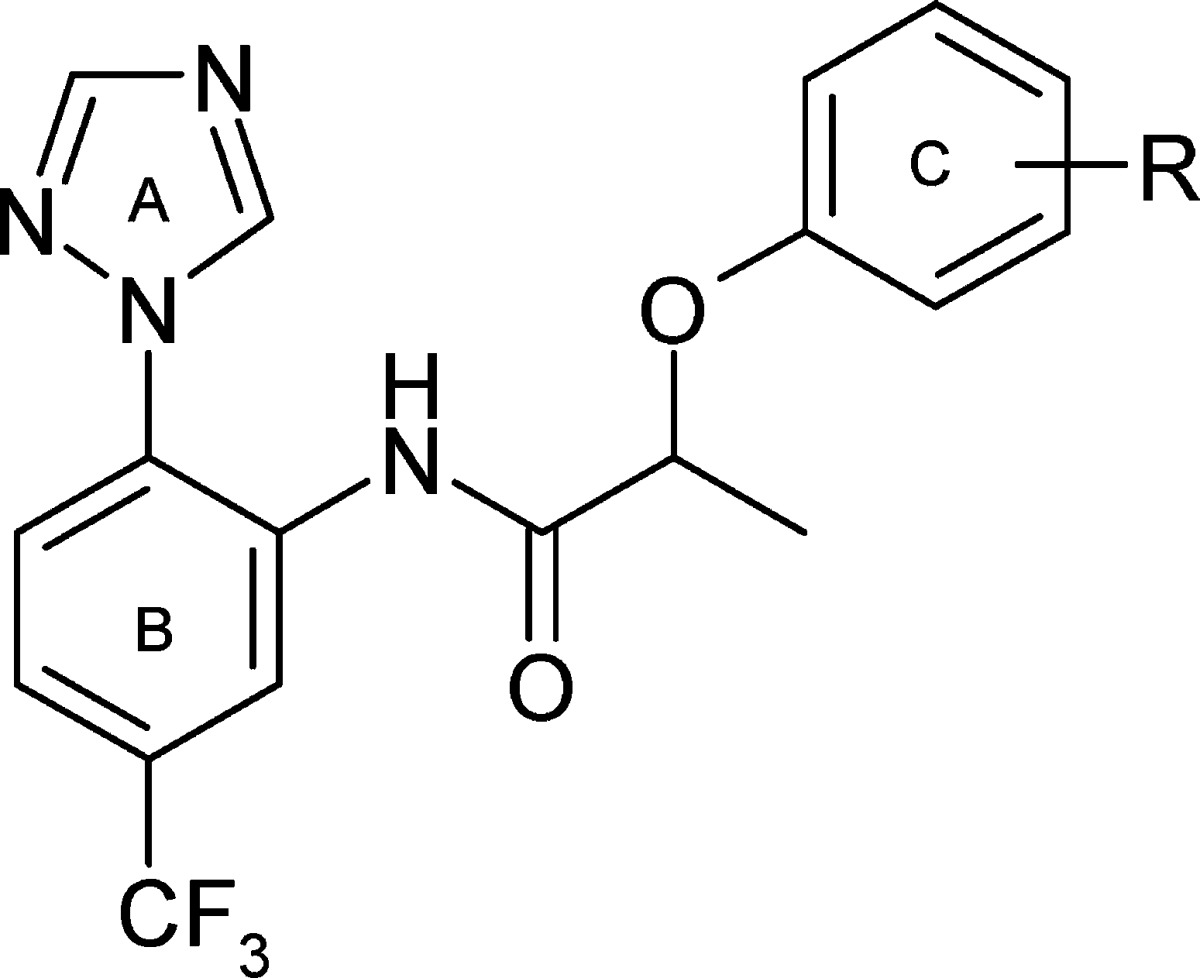

After careful computational analysis of TCAMS,12 three related carboxamide “hit” series were identified for further profiling (Table 1). All of the members of the series display as a common feature a trisubstituted left-hand (LH) aromatic ring linked through an amide to right-hand (RH) aromatic ring. The spacing between these aromatic rings is approximately similar but achieved in different ways by variation of the carboxylic acid fragment of the amide. Series 1 (referred to as the “triazolopyrimidine” series) features a bicyclic triazolopyrimidine carboxylic acid fragment (8 and 9), series 2 (referred to as the “lactic acid ether” series) features an aryloxy-lactic acid fragment (10–12), and series 3 (referred to as the “cyclopropyl carboxamide” series) features an arylcyclopropyl-acetic acid fragment (13 and 14). These series were immediately appealing as potential starting points for oral drug discovery programmes because of their relatively low molecular weights (339–429), lipophilicity (clog P 2.48–4.72), and hydrogen bond acceptor and donor counts. The series are also all synthetically tractable, which is important both for rapid lead optimization and in reducing potential cost of goods, which is crucial where the target cost per treatment for an adult is less than $1 and for a child less than $0.50. Less appealing was the potential for aniline metabolites, but in most cases, the amide bond is sterically hindered, which might prevent or retard metabolism.

Our initial strategy was to establish preliminary SAR for all three series with the ultimate aim of determining which series was the most promising for full lead optimization. To ensure that this was achieved as rapidly as possible, we focused on generating and testing those analogues that were most synthetically accessible. This left gaps in the SAR but, in our view, did not significantly affect the quality of decisions that were made.

The triazolopyrimidines of series 1 (8 and 9) appeared very potent in vitroP. falciparum inhibitors when using the LDH assay.11 However, when tested in the hypoxanthine assay, these compounds displayed only weak activity or were inactive, which from subsequent experiments was indicative of a delayed death phenotype (see the Supporting Information). As a rapid onset of action is desirable for first-line treatments, no further work was therefore carried out on series 1.

The lactic acid ethers of series 2 can be viewed as bioisosteres of series 1 where the triazole ring of the bicycle has been ring opened. From the data (Table 1), these do not suffer from the delayed killing phenotype of series 1. Methyl or chloro substitution is tolerated on the RH ring (ring C) (compounds 10vs11 and 12), while the morpholine substituent of ring B (11) can be replaced by a triazole substituent (12) without affecting the potency, but it does reduce the measured lipophilicity (CHI logD15) from 4.56 to 3.84. By inference from series 3, the trifluoromethyl group on ring B was likely to be preferred. As a result of these SAR together with the ready commercial availability of substituted aryloxy lactic acids, we initially explored the activity of substituents on ring C (Table 2) and on the carbon α to the amide carbonyl (see the Supporting Information). However, we were both unable to significantly increase potency, and the active members of the series possessed only short half-lives in mouse microsomes (Table 2 and the Supporting Information). These data, together with the indication that a chiral center might be required, led to further work on this series 2 being put on hold. In addition, analogues of the cyclopropyl carboxamide series 3, which were being prepared at the same time, were demonstrating profiles that were showing greater promise.

Table 2. SAR for Lactic Acid Ethers (Series 2).

| mouse microsomes |

human microsomes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd no. | Ra | MWtb | clog Pb CHIb | Pfb IC50 (μM) | CLic (mL/min/g) | t1/2 (min) | CLic (mL/min/g) | t1/2 (min) |

| 15 | H | 376.3 | 3.44 | 0.897 | 5.3 | 12.0 | 2.9 | 24.7 |

| 3.52 | ||||||||

| 16 | 2-Cl | 410.8 | 4.06 | 0.190 | 5.6 | 11.7 | 1.6 | >30 |

| 3.71 | ||||||||

| 17 | 3-Cl | 410.8 | 4.29 | 0.327 | 7.9 | 6.2 | 1.2 | >30 |

| 3.84 | ||||||||

| 12 | 4-Cl | 410.8 | 4.29 | 0.394 | 4.1 | 13.6 | 3.3 | 21.8 |

| 3.84 | ||||||||

| 18 | 3-CF3 | 444.3 | 4.57 | 0.285 | ||||

All compounds racemic where applicable.

See Table 1 for abbreviations.

In vitro intrinsic clearance.

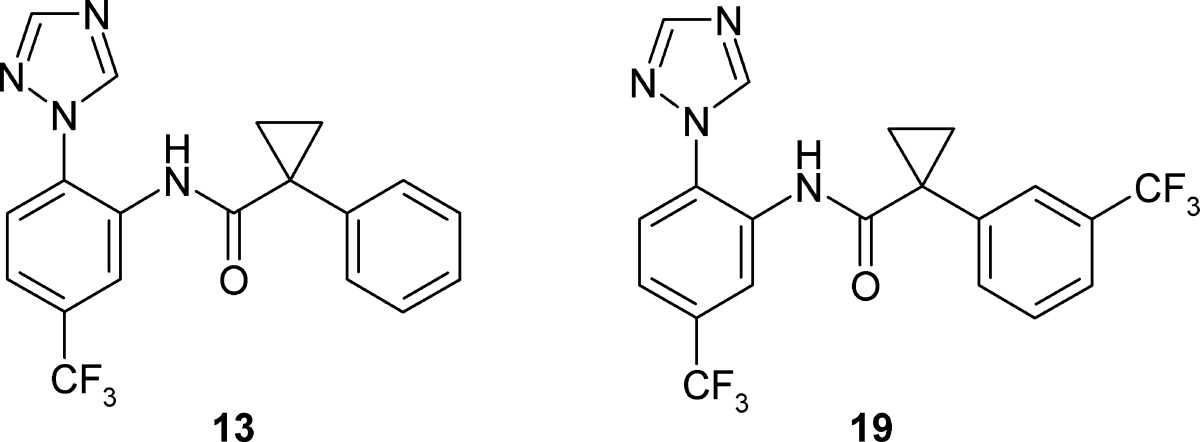

The cyclopropyl carboxamide series 3 (Table 1) is the most potent of the three series with 13 having a Pf IC50 of 66 nM. Like series 2, it also features a triazole substituent on the B ring while also incorporating a benzylic cyclopropyl group adjacent to the amide. The trifluoromethyl substituent on ring B of 13 is 25 times more active than the corresponding chloro analogue 14. The lipophilicity (CHI logD 3.83) and molecular weight (372) of 13 also allow modest scope for adding groups while still remaining within physicochemical space, which is reasonably compatible with oral absorption. We therefore initiated a brief but systematic exploration of the SAR for each part of the molecule, namely, (i) the A ring (the triazole in 13), (ii) the CF3 substituent in ring B, (iii) the cyclopropyl group adjacent to the amide carbonyl, and (iv) substitution on the C ring. In summary, exploration of i–iii gave no improvement in the overall properties of the series (see the Supporting Information). However, a wide variety of substituents were explored in optimization of the substitution on the C ring (see the Supporting Information) and the electronic and lipophilic nature of 19—featuring a m-CF3—proved highly beneficial with a 30-fold increase in activity with a Pf IC50 of 3 nM (Table 3). As a next step, we therefore embarked on a fuller profiling of the leads 13 and 19 (Table 3), including pharmacokinetic and efficacy studies, prior to initiating full lead optimization.

The overall profiles of both 13 and 19 are reasonable;14 however, improving the solubility will help developability. Reducing the plasma protein binding might decrease the ultimate clinical dose although both compounds have promising in vivo activity (see later) despite the very high protein binding observed. Improving selectivity over the PXR receptor and PDE4B would also be beneficial.16

The pharmacokinetic profiles of both 13 and 19 were evaluated in CD-1 mice (Table 4). Following intravenous administration to CD-1 mice, compounds 13 and 19 were characterized by a moderate clearance (1/10–3/4 liver blood flow) and a high volume of distribution. The estimated terminal half-life was high for 13 and very high for 19. A high oral bioavailabity was calculated after the oral gavage administration of 20 mg/kg for both compounds (see the Supporting Information).

Table 4. Pharmacokinetic Parameters for 13 and 19 Estimated in Blood in CD-1 Micea.

| area under curve AUC0-t (μg/h/mL) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd no. | clearance (mL/min/kg) | volume of distribution (L/kg) | half-lifeb (h) | maximum concn Cmaxc (μg/mL) | iv | po | oral bioavailability (% F) |

| 13d | 29.7 | 6.47 | 2.77 | 2.34 | 0.596 | 9.71 | 81 |

| 19e | 14.3 | 11.9 | 10.2 | 1.09 | 2.23 | 13.6 | 55 |

Dosing 2 mg/kg iv and 20 mg/kg po into CD-1 mice (n = 4 for both arms).

iv.

po.

iv vehicle 20% (v:v) encapsine in water, po vehicle 1% (w:v) methylcellulose in water.

iv vehicle 3% solutol, 7% PEG (v:v) in saline, po vehicle 1% (w:v) methylcellulose in water.

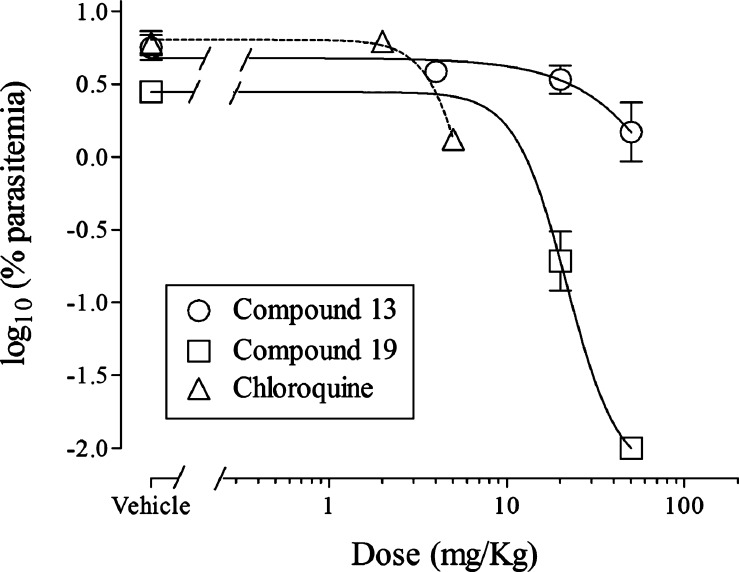

Both compounds displayed in vivo efficacy after oral dosing in a nonmyelo-depleted P. falciparum murine model.17,18 Briefly, groups of three mice engrafted with human erythrocytes were injected with 20 × 106P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes per mouse. Three days after infection, mice were treated with vehicle and compounds 13 and 19. Parasitemia in peripheral blood was assessed from day 3 to day 7 (Figure 1). Both compounds inhibited P. falciparum growth in vivo with estimated efficacies expressed as ED90 values of >50 and 20 mg/kg for 13 and 19, respectively. Chloroquine was used as the control and has an ED50 of between 2 and 5 mg/kg (from 24 experiments). By way of comparison, the ED50 values of 13 and 19 are >50 and 12 mg/kg, respectively.

Figure 1.

Plot of compound dose (chloroquine 2, 13, and 19) vs log10 (% parasitemia) after oral administration. See the text for assay details and estimated ED50 and ED90 values.

Described herein is the first report of exploration of lead series selected from the TCAMS. Initial SAR exploration of three carboxamide series led to the rapid deprioritization of two of the series. In contrast, a cyclopropyl carboxamide series displayed promising properties in particular possessing good oral bioavailability in CD-1 mice and also in vivo activity with the ED50 of 19 being only 2–3 times higher than that of chloroquine under these conditions, although additional studies would be needed to assess the real potential for curing malaria. As such, it represents a starting point for the discovery of a new antimalarial treatment. Further studies on this series have been carried out, and details will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues from the Computational, Analytical and Structural Chemistry (CASC) department for the measurement of the physicochemical properties of compounds described in this paper.

Supporting Information Available

Further experimental details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

GlaxoSmithKline acknowledges financial support from Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) and for the perceptive and helpful advice from Jeremy Burrows and Mike Witty.

Supplementary Material

References

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2009; http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241563901/en/index.html.

- Wells T. N. C.; Alonso P. L.; Gutteridge W. E. New medicines to improve control and contribute to the eradication of malaria. Nature Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.; Nagle A. S.; Chatterjee A. K. Road towards new antimalarials—Overview of the strategies and their chemical progress. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 853–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.-K; Plattner J. J.; Freund Y. R.; Easom E. R.; Zhou Y.; Gut J.; Rosenthal P. J.; Waterson D.; Gamo F.-J.; Angulo-Barturen I.; Ge M.; Li Z.; Li L.; Jian Y.; Cui H.; Wang H.; Yang J. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of novel benzoxaboroles as a new class of antimalarial agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 644–651; see also http://www.mmv.org/newsroom/press-releases/anacor-pharmaceuticals-and-mmv-sign-agreement-pursue-promising-compound-mala. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucumi E.; Darling C.; Jo H.; Napper A. D.; Chandramohanadas R.; Fisher N.; Shone A. E.; Jing H.; Ward S. A.; Biagini G. A.; DeGrado W. F.; Dimond S. L.; Greenbaum D. C. Discovery of potent small molecule inhibitors of muti-drug resistant Plasmodium falciparum using a novel miniaturized high-throughput luciferase-based assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 276, 128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baragana B.; McCarthy O.; Sanchez P.; Bosch-Navarrete C.; Kaiser M.; Brun R.; Whittingham J. L.; Roberts S. M.; Zhou X.-X.; Wilson K. S.; Johansson N. G.; Gonzalez-Pacanowska D.; Gilbert I. H. Beta-Branched acyclic nucleoside analogues as inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum dUTPase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 19, 2378–2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Anderson M.; Weisman J. L.; Lu M.; Choy C. J.; Boyd V. A.; Price J.; Sigal M.; Clark J.; Connelly M.; Zhu F.; Guiguemde W. A.; Jeffries C.; Yang L.; Lemoff A.; Liou A. P.; Webb J. L.; Guy R. K. Evaluation of diarylureas for activity against Plasmodium falciparum. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 460–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons P.; Verissimo E.; Barton V.; Nixon G. L.; Amewu R. K.; Chadwick J.; Stocks P. A.; Biagini G. A.; Srivastava A.; Rosenthal P. J.; Gut J.; Guedes R. C.; Moreira R.; Sharma R.; Berry N.; Cristiano M. L. S.; Shone A. E.; Ward S. A.; O'Neill P. M. Endoperoxide carbonyl falcipain 2/3 inhibitor hybrids: towards combination chemotherapy of malaria through a single chemical entity. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 8202–8206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plouffe D.; Brinker A.; McNamara C.; Henson K.; Kato N.; Kuhen K.; Nagle A.; Adrian F.; Matzen J. T.; Anderson P.; Nam T. G.; Gray N. S.; Chatterjee A. K.; Janes J.; Yan S. F.; Trager R.; Caldwell J. S.; Schultz P. G.; Zhou Y.; Winzeler E. A. In silico activity profiling reveals the mechanism of action of antimalarials discovered in a high-throughput screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 9059–9064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiguemde W. A.; Shelat A. A.; Bouck D.; Duffy S.; Crowther G. J.; Davis P. H.; Smithson D. C.; Connelly M.; Clark J.; Zhu F.; Jimenenz-Diaz M. B.; Martinez M. S.; Wilson E. B.; Tripathi A. K.; Gut J.; Sharlow E. R.; Bathurst I.; El Mazouni F.; Fowble J. W.; Forquer I.; McGinley P. L.; Castro S.; Angulo-Barturen I.; Ferrer S.; Rosenthal P. J.; De Risi J. L.; Sullivan D. J. Jr.; Lazo J. S.; Roos D. S.; Riscoe M. K.; Phillips M. A.; Rathod P. K.; Van Voorhis W.; Avery V. M.; Guy R. K. Chemical genetics of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 2010, 465, 311–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamo F.-J.; Sanz L. M.; Vidal J.; de Cozar C.; Alvarez E.; Lavandera J.-L.; Vanderwall D. E.; Green D. V. S.; Kumar K.; Hasan S.; Brown J. R.; Peishoff C. E.; Cardon L. R.; Garcia-Bustos J. F. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature 2010, 465, 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón F.; Barros D.; Bueno J. M.; Coterón J. M.; Fernández E.; Gamo F. J.; Lavandera J. L.; León M. L.; Macdonald S. J. F.; Mallo A.; Manzano P.; Porras E.; Fiandor J. M.; Castro J.. An Invitation to Open Innovation in Malaria Drug Discovery: 47 Quality Starting Points from the TCAMS. ACS Med. Chem. Lett., DOI: 10.1021/ml200135p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidock D. A.; Rosenthal P. J.; Croft S. L.; Brun R.; Nwaka S. Antimalarial drug discovery: Efficacy models for compound screening. Nature Rev. Drug Discovery 2004, 3, 509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key compounds also showed no or little cytotoxicity against L1210, neuro 2A, H9C2, and MDCK cell lines.

- Valko K.; Bevan C.; Reynolds A. Chromatographic Hydrophobicity Index by Fast-Gradient RP-HPLC: A High-Throughput Alternative to log P/log D. Anal. Chem. 1997, 69, 2022–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The undecorated scaffold of 19 (i.e., without substituents on the aryl B or C rings) occurs fairly frequently in the literature (ca. 500 references in SciFinder in the last 5 years when searched in April 2011), but decorating the scaffold as in 19 provides only two distantly related chemotypes described in the patent literature:; Linders J. T. M.; Willemsens G. H. M.; Gilissen R. A. H. J.; Buyck C. F. R. N.; Vanhoof G. C. P.; Ven Der Veken L. J. E.; Jaroskova L.. Preparation of adamantly acetamides as hydroxysteroid dehydrogenanse inhibitors. PCT WO 2004056744, 2004.; Cremer G.; Hoornaert C.. (IH-imidiazol-4-yl)piperidine derivatives as inhibitors of Na/H+ exchange. PCT WO 9901435, 1999.

- Angulo-Barturen I.; Jimenez-Diaz M. B.; Mulet T.; Rullas J.; Herreros E.; Ferrer S.; Jimenez E.; Mendoza A.; Regadera J.; Rosenthal P. J.; Bathurst I.; Pompliano D. L.; Gomez de las Heras F.; Gargallo-Viola D. A. Murine model of falciparum—Malaria by in vivo selection of competent strains in non-myelodepleted mice engrafted with human erythrocytes. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Díaz M. B.; Mulet T.; Viera S.; Gómez V.; Garuti H.; Ibáñez J.; Alvarez-Doval A.; Shultz L. D.; Martínez A.; Gargallo-Viola D.; Angulo-Barturen I. Improved murine model of malaria using Plasmodium falciparum competent strains and non-myelodepleted NOD-scid IL2Rγnull mice engrafted with human erythrocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 4533–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.