Abstract

An efficient method for the reconstruction of the 9-dihydroerythromycin A macrolactone skeleton has been established. The key steps are oxidative cleavage at the 11,12-position and reconstruction after insertion of an appropriate functionalized amino alcohol. Novel 15-membered macrolides, we named as “11a-azalides”, were synthesized based on the above methodology and evaluated for their antibacterial activity. Among them, (13R)-benzyloxymethyl-11a-azalide showed the most potent Streptococcus pneumoniae activity, with improved activity against a representative erythromycin-resistant strain compared to clarithromycin (CAM).

Keywords: Antibiotic, macrolide, 11a-azalide, resistant-pathogen, novel scaffold

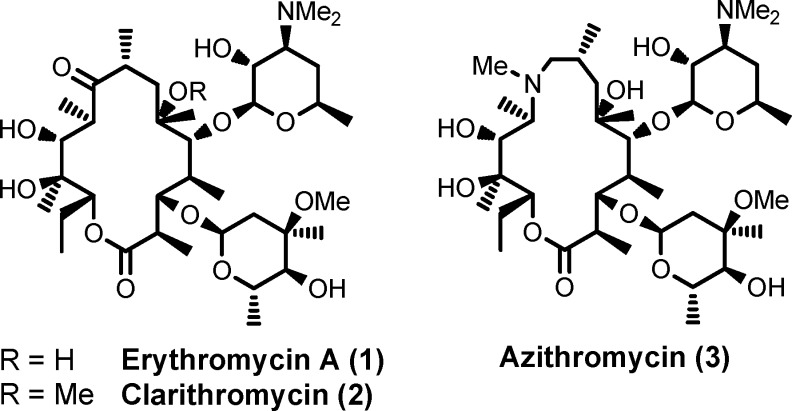

Macrolide antibiotics1−4 (see Figure 1 for some structures) are a safe and effective class of drugs for the treatment of respiratory tract infections. Erythromycin A (EM-A, 1), a 14-membered macrolide antibiotic, has been widely prescribed for more than five decades. Since EM-A decomposed to antibacterialy inactive spiroketal products5 under the acidic conditions in the stomach, its bioavailability was not high and interindividually varied.6 To improved the pharmacokinetic profile of EM-A caused by the acid instability, enteric-coating of the tablets and chemical modifications of EM-A have been performed.1−4 Second-generation macrolides, such as clarithromycin7 (CAM, 2) and azithromycin8 (AZM, 3), were investigated in the 1980s and eventually launched in the 1990s as a result of chemical modification efforts.

Figure 1.

Structures of macrolide antibiotics.

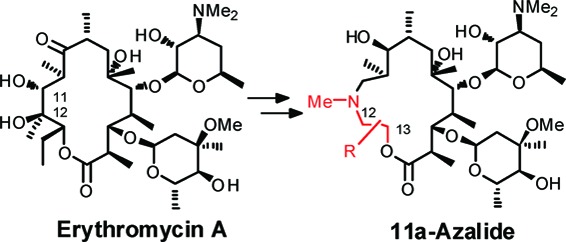

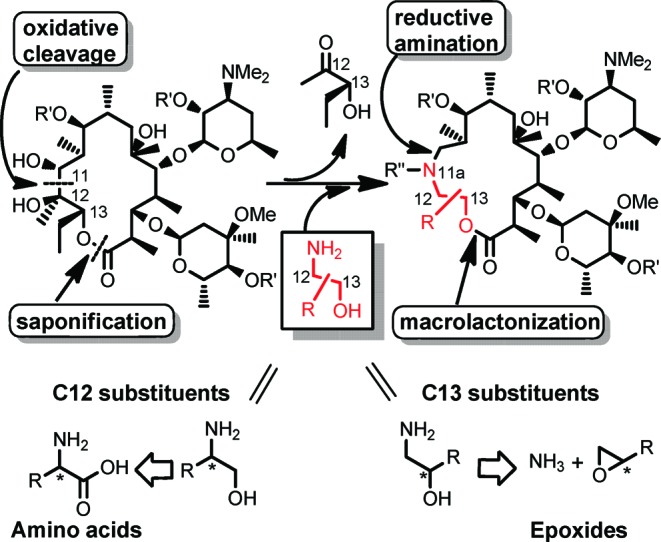

The increasing prevalence of macrolide-resistant pathogens among clinical isolates in recent times is of concern to public health.9−12 To overcome resistance problems, numerous chemical modifications of EM-A have been attempted.13−15 In a chemobiosynthesis report seeking novel scaffolds by transformation of the macrolactone skeleton, the C13 position of EM-A promises to play a key role in the improvement of antibacterial activity against resistant pathogens.16,17 However, chemical modification at the C13 position has been underexplored because of its lack of chemical reactivity. During the mid 1990s, Waddell18,19 and Nishida20 independently reported C9−C13 modified EM-A derivatives, synthesized from the original C1−8 or 9 fragment of EM-A and a newly prepared C9 or 10−13 fragment. Although this “cut and paste” methodology seemed to be a universal procedure to provide structural diversity into the C13 region, the reported compounds were limited to simple and primitive derivatives. Alternatively, related ring reconstruction methodology using 16-membered macrolide as the starting material has been reported.21 In this paper, we report an efficient method for the reconstruction of the macrolactone skeleton that enables us to synthesize a novel class of 15-membered macrolide antibiotics, “11a-azalides”, possessing a variety of substituents on the C12 and/or C13 position.

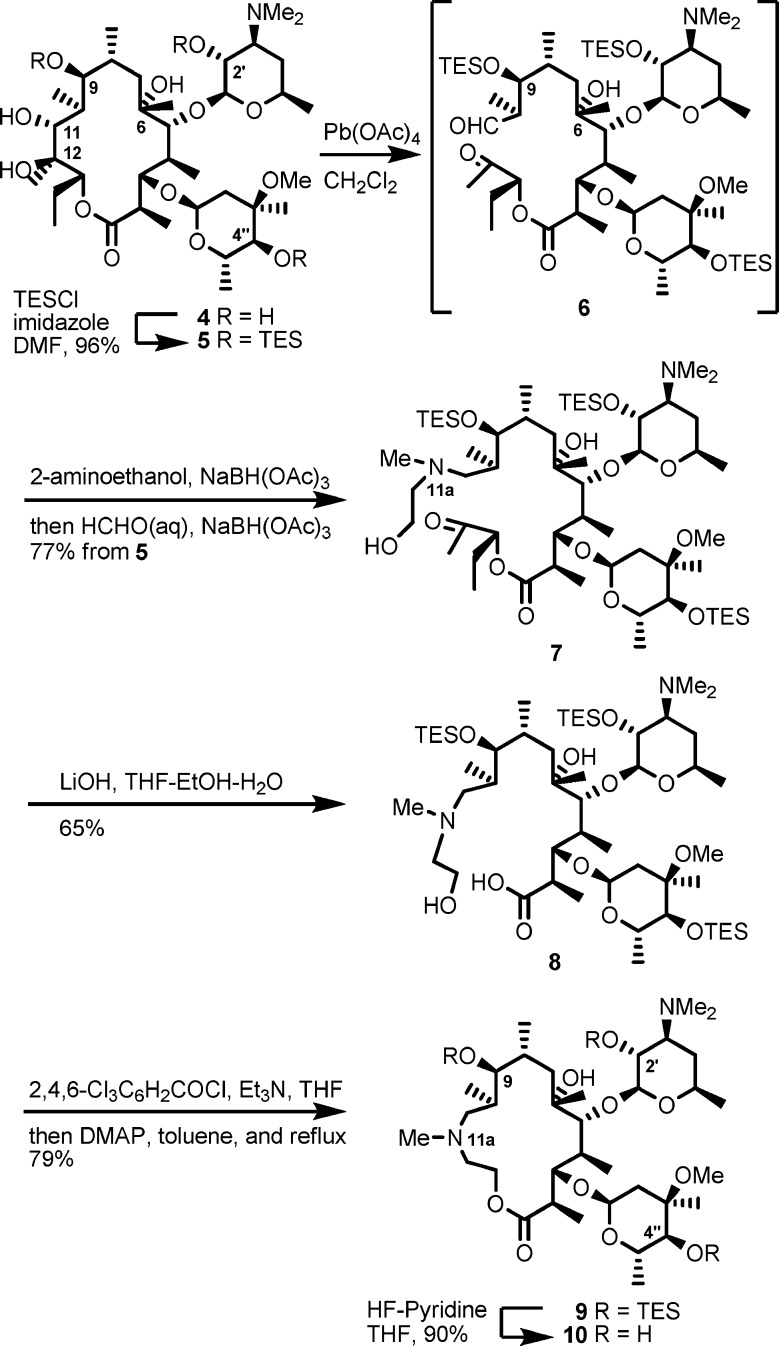

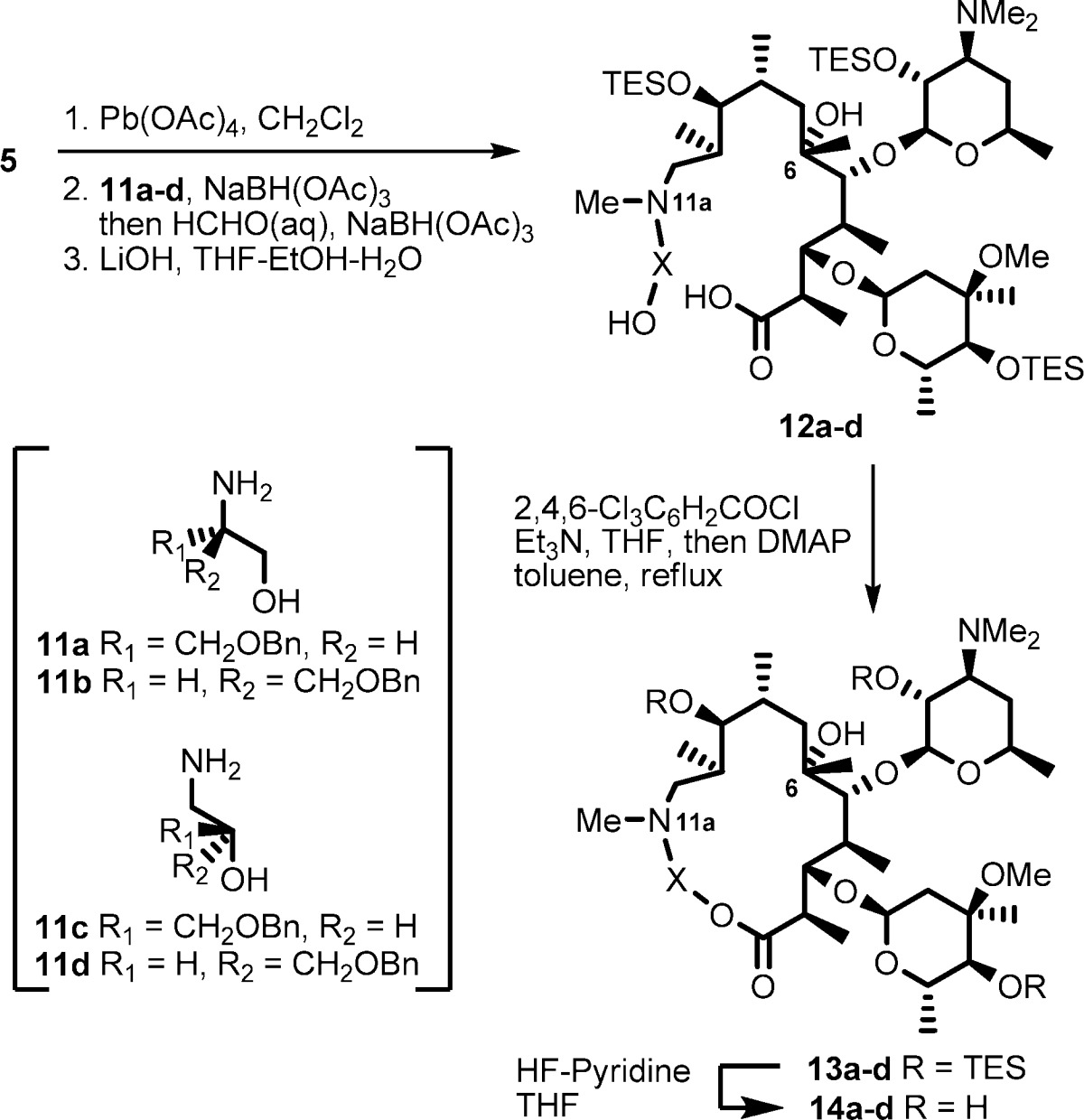

Our synthetic strategy is shown in Scheme 1. The 11,12-diol moiety of the EM-A macrolactone skeleton was cleaved oxidatively. After insertion of an appropriate functionalized amino alcohol and successive saponification of the remaining original C12−13 residue, the resulting acyclic skeleton was intramolecularly cyclized by a macrolactonization reaction. The advantage of this strategy over previous methods was that it enabled us to provide structural diversity to both the C12 and C13 positions using an easily prepared, functionalized amino alcohol.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Strategy for 11a-Azalide.

Our initial approach was to establish a methodology using reconstruction of the simplest macrolactone skeleton. EM-A (9-keto analogue) was converted to an acyclic keto-aldehyde intermediate by treatment with lead tetraacetate. However, the reductive amination of the aldehyde with 2-aminoethanol failed, presumably because of the formation of an unstable β-keto-aldehyde intermediate. To avoid side reactions, (9S)-9-dihydroerythromycin (4) was selected as the starting material (Scheme 2). The 9-dihydro derivative 4 was readily prepared by reduction of tthe 9-keto group of 1.22,23 The 9,2′,4′′-hydroxyl groups of 4 were selectively protected by triethylsilyl (TES) groups to give 11,12-diol 5, which was then treated with lead tetraacetate to give acyclic aldehyde intermediate 6.24 Reductive amination25 of aldehyde 6 with 2-aminoethanol and subsequent methylation of the resulting secondary amine at the 11a-position with formaldehyde gave the desired seco-ester 7. The above three sequential reactions were performed in a one-pot manner in 77% yield from diol 5.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 11a-Azalide.

Saponification of seco-ester 7 with LiOH produced seco-acid 8 in 65% yield, and macrolactone skeleton reconstruction was achieved using modified Yamaguchi’s macrolactonization method.26−28 Seco-acid 8 was converted to a mixed anhydride by the treatment with triethylamine and 2,4,6-trichlorobenzoyl chloride in THF at 50 mM. When the mixed anhydride solution was added dropwise to a tenth-volume of refluxing solution of 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (25 equiv), the macrolactonization reaction proceeded smoothly to give the 15-membered macrolide 9 in 79% yield. Deprotection of the TES groups of 9 was conducted by HF-pyridine treatment to give the desired 11a-azalide 10 in 90% yield.

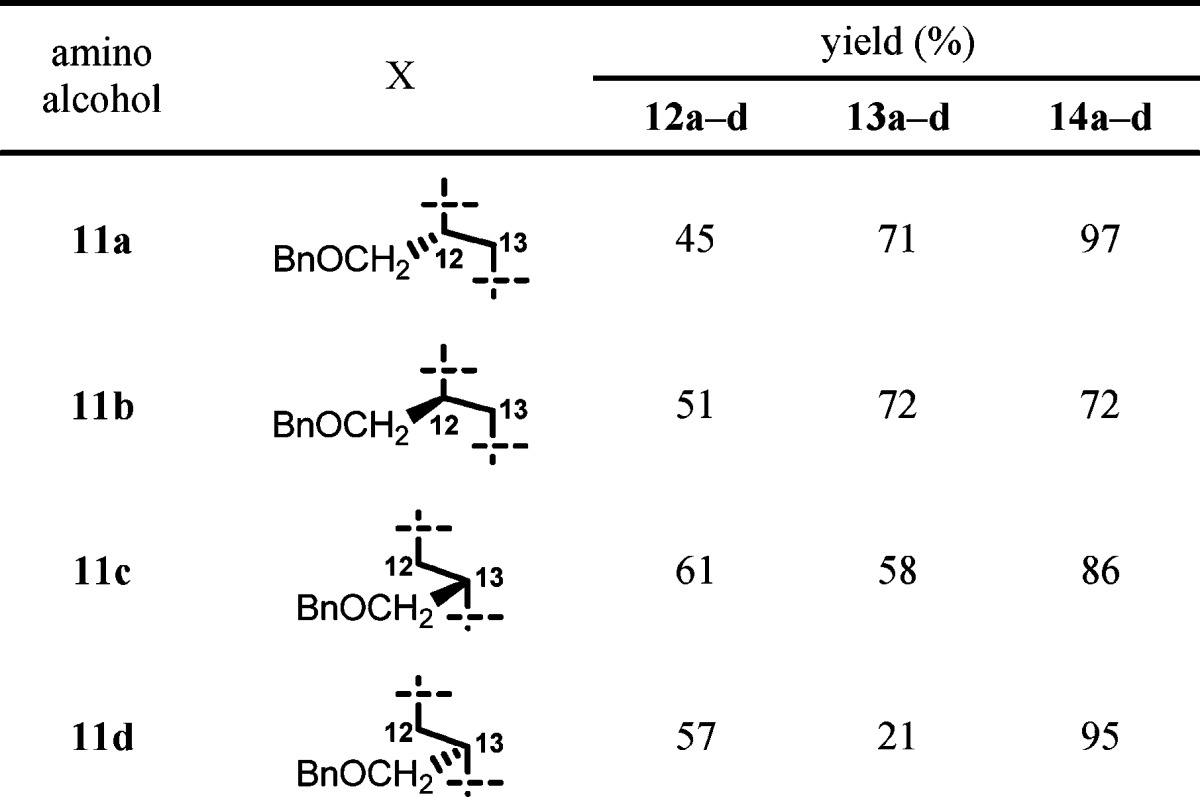

Based on the established methodology, we synthesized 12-/13-benzyloxymethyl-11a-azalides 14a−d (Table 1). Amino alcohols 11a,b29 were prepared through reduction of optically active O-benzyl serine with LiAlH4, and 11c,d were prepared by ring-opening reactions of optically pure benzylglycidol with aqueous ammonia. Seco-acids 12a−d were prepared from 5 and amino alcohols 11a−d in a manner similar to the preparation of 8. Macrolactonization reaction of seco-acids 12a,b, which possess a primary hydroxyl group, proceeded smoothly to give the desired 12-substituted-11a-azalides 13a,b. On the other hand, reaction of seco-acids 12c,d, which possess a secondary hydroxyl group, gave the desired 15-membered products 13c,d in relatively low yield along with an undesired 7-membered byproduct.30 In the macrolactonization reaction of erythronolides,31,32 the 6-hydroxyl group of seco-acids was generally inert. However, the same 7-membered byproduct has been observed in the case of glycosylated seco-acid.33 HF-pyridine treatment of 13a−d gave the desired 12-/13-substituted 11a-azalides 14a−d.

Table 1. Synthesis of 12-/13-Substituted 11a-Azalides.

|

The antibacterial activities of the synthesized 11a-azalides against Streptococcus pneumoniae were evaluated as shown in Table 2.34 Compound 14d showed the most potent antibacterial activity against erythromycin-susceptible S. pneumoniae compared to CAM, and it showed a 4-fold improved antibacterial activity against the erythromycin-resistant strain compared to CAM. The position and configuration of the substituents on the 11a-azalides turned out to have a significant impact on the antibacterial activity.

Table 2. Antibacterial Activity of 11a-Azalides.

| MIC (μg/mL) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 14a | 14c | 14d | CAM | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC49619a | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| S. pneumoniae 205b | >128 | 128 | 64 | 32 | >128 |

Erythromycin-susceptible strain.

Erythromycin-resistant strain.

In conclusion, we established an efficient method for the reconstruction of the 9-dihydroerythromycin A macrolactone skeleton. Based on this methodology, we synthesized a novel class of 15-membered macrolides “11a-azalides” possessing a substituent on their C12 or C13 position. Among them, (13R)-benzyloxymethyl-11a-azalide 14d showed the most potent S. pneumoniae activity, with improved activity against the representative erythromycin-resistant strain compared to CAM. This methodology provides 11a-azalides as a novel scaffold, which allows us to engage in further exploration to improve the antibacterial activity against resistant pathogens.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Keiko Suzuki and Ms. Yukiko Yamasaki for providing antibacterial activity data.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

T.S. led research design (chemistry) and execution (performed synthesis) and contributed to writing of the manuscript, and is the corresponding author; T.T. participated in research design (chemistry) and execution (performed synthesis) and contributed to writing of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- For recent reviews, see: ; Omura S.Macrolide Antibiotics. Chemistry, Biology, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Academic Press Inc.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T.; Dougherty T. J.; Magee T. V.. Macrolide Antibiotics. In Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry II; Taylor J. B, Triggle D. J, Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: Oxford, U.K., 2006; Vol. 7, pp 973−980. [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau J. M. The Evolution and Role of Macrolides in Infectious Diseases. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2002, 3, 1131–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau J. M.; DeCarolis E.; Metzer K. L.; Hansen G. T. The Macrolide. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 2002, 11, 189–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurath P.; Jones P. H.; Egan R. S.; Perun T. J. Acid degradation of erythromycin A and erythromycin B. Experientia 1971, 27, 362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. T.; van Boxtel C. J. Pharmacokinetics of erythromycin in man. Antibiot. Chemother. 1978, 25, 181–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto S.; Takahashi Y.; Watanabe Y.; Omura S. Chemical Modification of Erythromycins. I. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of 6-O-Methylerythromycins A. J. Antibiot. 1984, 37, 187–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djokić S.; Kobrehel G.; Lazarevski G.; Lopotar N.; Tamburasě v, Z. Erythromycin Series. Part 11. Ring Expansion of Erythromycin A Oxime by the Beckmann Rearrangement. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1986, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar]

- Doern G. V.; Heilmann K. P.; Huynh H. K.; Rhomberg P. R.; Coffman S. L.; Brueggemann A. B. Antimicrobial Resistance among Clinical Isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States during 1999−2000, Including a Comparison of Resistance Rates since 1994−1995. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 1721–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoban D. J.; Zhanel G. G. Clinical implications of macrolide resistance in community-acquired respiratory tract infections. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2006, 4, 973–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins S. G.; Brown S. D.; Farrell D. J. Trends in antibacterial resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in the USA: update from PROTEKT US years 1−4. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2008, 7, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmingham D.; Cantón R.; Jenkins S. G. Regional trends in beta-lactam, macrolide, fluoroquinolone and telithromycin resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates 2001−2004. J. Infect. 2007, 552111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T.; McArthur H.; Sutcliffe J. Recent Developments in the Area of Macrolide Antibiotics. Expert Opin. Ther. Patents 2000, 10, 403–425. [Google Scholar]

- Asaka T.; Manaka A.; Sugiyama H. Recent Developments in Macrolide Antimicrobial Research. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2003, 3, 961–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S. A. Journey Across the Sequential Development of Macrolides and Ketolides Related to Erythromycin. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 3171–3200. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw S. J.; Abbanat D.; Ashley G. W.; Bush K.; Foleno B.; Macielag M.; Zhang D.; Myles D. C. 15-Amido Erythromycins: Synthesis and in Vitro Activity of a New Class of Macrolide Antibiotics. J. Antibiot. 2005, 58, 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley G. W.; Burlingame M.; Desai R.; Fu H.; Leaf T.; Licari P. J.; Tran C.; Abbanat D.; Bush K.; Macielag M. Preparation of Erythromycin Analogs Having Functional Groups at C-15. J. Antibiot. 2006, 59, 392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell S. T.; Blizzard T. A. Chimeric Azalides with Simplified Western Portions. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 5385–5388. [Google Scholar]

- Waddell S. T.; Eckert J. M.; Blizzard T. A. Chimeric Azalides with Functionalized Western Portions. Heterocycles 1996, 43, 2325–2332. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida A.; Yagi K.; Kawahara N.; Nishida M.; Yonemitsu O. Chemical Modification of Erythromycin A: Synthesis of the C1−C9 Fragment from Erythromycin A and Reconstruction of the Macrolactone Ring. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 3215–3218. [Google Scholar]

- Miura T.; Kanemoto K.; Natsume S.; Atsumi K.; Fushimi H.; Yoshida T.; Ajito K. Novel azalides derived from 16-membered macrolides. Part II: Isolation of the linear 9-formylcarboxylic acid and its sequential macrocyclization with an amino alcohol or an azidoamine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 10129–10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabski T.; Bojarska-Dahlig H.; Slawinski W. Erythromycin derivatives. Part VIII. 9-Dihydroerythromycin A cyclic 11,12-carbonate. Pol. Roczniki Chem. 1976, 50, 1281–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.-M.; Wong H. N. C.; Chu D. T. W.; Lin X. Synthetic Studies of Erythromycin Derivatives: 6-O-Methlation of (9S)-12,21-Anhydro-9-dihydroerythromycin A Derivatives. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 7033–7045. [Google Scholar]

- The aldehyde 6 was not isolated in high purity. Selected 1H NMR spectral data of crude 6: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.81 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 11-CHO), 2.16 (s, 12-COCH3).

- Abdel-Magid A. F.; Carson K. G.; Harris B. D.; Maryanoff C. A.; Shah R. D. Reductive Amination of Aldehydes and Ketones with Sodium Triacetoxyborohydride. Studies on Direct and Indirect Reductive Amination Procedures. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 3849–3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagawa J.; Hirata K.; Saeki H.; Katsuki T.; Yamaguchi M. A Rapid Esterification by Means of Mixed Anhydride and Its Application to Large-ring Lactonization. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979, 52, 1989–1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tone H.; Nishi T.; Oikawa Y.; Hikota M.; Yonemitsu O. A Stereoselective Total Synthesis of (9S)-9-Dihydroerythronolide A from D-Glucose. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 4569–4572. [Google Scholar]

- Hikota M.; Tone H.; Horita K.; Yonemitsu O. Stereoselective Synthesis of Erythronolide A via an Extremely Efficient Macrolactonization by the Modified Yamaguchi Method. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Keith D. D.; De Bernardo S.; Weigele M. The Absolute Configration of Rhizobitoxine. Tetrahedron 1975, 31, 2629–2632. [Google Scholar]

- In the case of the macrolactonization reaction of seco-acid 12d, the undesired 7-membered byproduct was isolated in 32% yield.

- Hikota M.; Tone H.; Horita K.; Yonemitsu O. Stereoselective Synthesis of Erythronolide a Extremely Efficient Lactonization Based on Conformational Adjustment and High Activation of Seco-acid. Tetrahedron 1990, 46, 4613–4628. [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. F.; Hida T.; Kym P. R.; Loft M.; Hodgson A. The Asymmetric Synthesis of Erythromycin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 3193–3194. [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. F.; Yamashita M. Novel Macrolactonization Strategy for the Synthesis of Erythromycin Antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 406–410. [Google Scholar]

- Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by the broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (formerly National Committee of Clinical Laboratory Standards) guidelines for S. pneumoniae.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.