Abstract

Optimization of a benzofuranyl S1P1 agonist lead compound (3) led to the discovery of 1-(3-fluoro-4-(5-(2-fluorobenzyl)benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)benzyl)azetidine-3-carboxylic acid (14), a potent S1P1 agonist with minimal activity at S1P3. Dosed orally at 0.3 mg/kg, 14 significantly reduced blood lymphocyte counts 24 h postdose and attenuated a delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) response to antigen challenge.

Keywords: Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor, S1P1, agonist, inflammation, lymphocyte

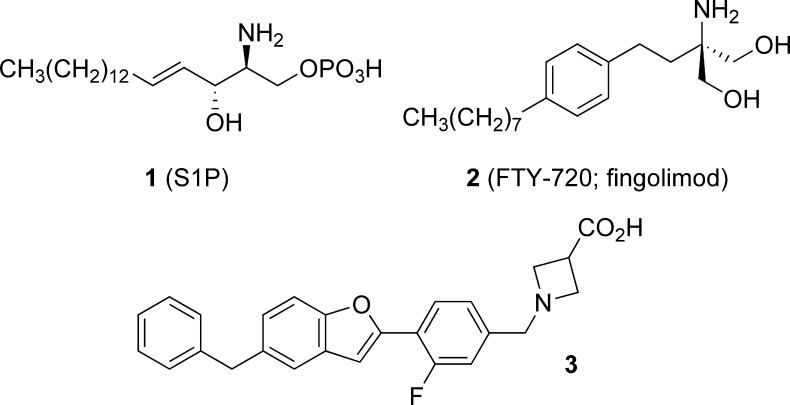

Research efforts over the past decade have revealed the lysophospholipid sphingosine-1-phosphate (1, S1P; Figure 1) to be a pleiotropic modulator of diverse cellular processes including migration, adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation.1,2 These effects are mediated, at least in part, by the interaction of S1P with a set of paralogous G protein-coupled receptors (S1P1−5), which are widely expressed in the immune, cardiovascular, and central nervous systems.3−5 The S1P1 receptor, highly expressed in lymphocytes, has recently been the focus of extensive investigation due to its role in the regulation of lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes.6−9

Figure 1.

S1P, FTY-720, and benzofuran lead 3.

Much of this effort has centered on the study of fingolimod (2, FTY-720),10 a synthetic amino diol prodrug, which is stereoselectively phosphorylated in vivo by sphingosine kinase 2 to generate the corresponding (S)-phosphate (FTY-720P), which is a potent agonist of S1P1,3−5. FTY-720P binding to lymphocyte S1P1 receptors leads to receptor internalization (RI) and proteolysis.11 Knockout studies in mice have revealed S1P1 receptor expression in T12,13 and B cells14 to be required for these lymphocytes to exit secondary lymphoid organs and enter the circulation; FTY-720P-mediated RI thus leads to lymphocyte sequestration in secondary lymphoid organs.15

Although FTY-720-mediated lymphocyte sequestration does not impair antiviral and antibacterial immune responses to secondary infections in rodent models,16,17 decreased lymphocyte recruitment to sites of inflammation has been demonstrated to moderate immune responses in rodent models of multiple sclerosis18,19 and organ transplantation.20 Phase III human clinical trials have recently revealed 2 to be efficacious in reducing relapse rates in patients with relapsing−remitting multiple sclerosis.21,22

Human clinical trials have additionally shown dosing of 2 to be associated with transient, dose-dependent decreases in mean heart rate and asymptomatic atrioventricular blockade.23 Studies of 2 in rodents have revealed lymphocyte sequestration and heart rate reduction to be driven by distinct S1P receptor isoforms (S1P1 and S1P3, respectively), however.24−27 These observations, coupled with the impressive efficacy of 2 emerging from human clinical investigations, have prompted the widespread search for S1P1 agonists with minimal activity at the S1P3 receptor.28,29 In this communication, we describe the discovery of a potent S1P3-sparing S1P1 agonist, benzothiazole 14, as well as its in vivo pharmacological and pharmacokinetic characteristics.

In prior work, in silico docking of a library of commercially available molecules with druglike properties into a S1P1 receptor model generated using PREDICT methodology,30 followed by modeling-driven structure−activity relationship (SAR) studies, led to the identification of a benzofuran-containing hit series, of which 3 was chosen as the lead molecule.31 Benzofuran 3 demonstrated double-digit nanomolar activity at hS1P1 in an assay measuring RI of an hS1P1-GFP fusion protein in U2OS cells and limited activity at hS1P3 as determined by Ca2+ mobilization in hS1P3- and Gq/i5-transfected CHO-K1 cells (Table 1). Oral dosing (1 mg/kg) of 3 in rats resulted in a statistically significant reduction in circulating lymphocytes 24 h postdose and significantly attenuated a delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) response to antigen challenge.32 One potential liability of 3 identified during preclinical toxicology studies was the observation of proconvulsive activity in rat at oral doses of 40 mg/kg and higher. Herein, we report on a successful effort to identify derivatives of 3 lacking this liability.

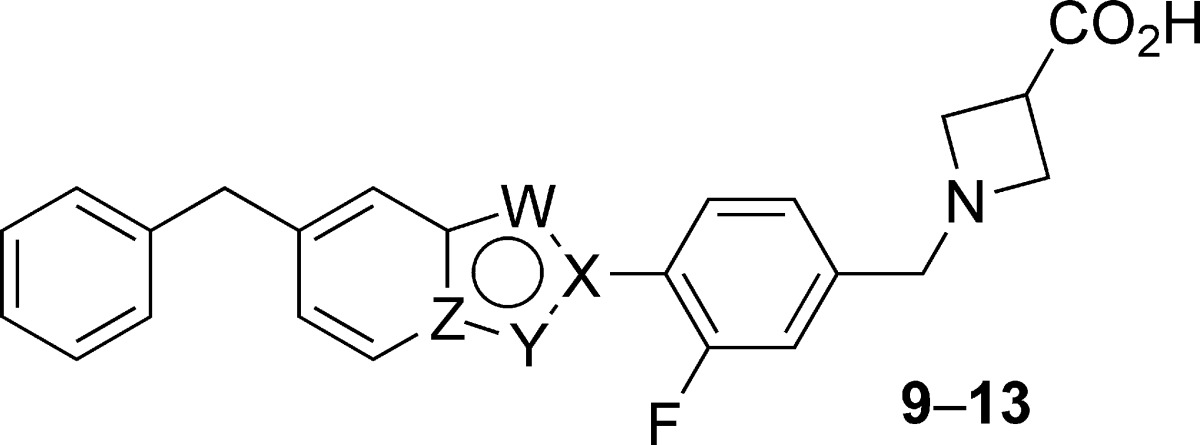

Table 1. SAR of 5-Benzyl-Substituted Bicyclic Coresa.

| compd | W | X | Y | Z | hS1P1 RI EC50 (μM) (% efficacy) | hS1P3 Ca2+ EC50 (μM) (% efficacy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | O | C | CH | C | 0.057 (96) | 1.73 (42) |

| 4 | O | C | N | C | 0.325 (105) | 0.354 (77) |

| 5 | N | C | S | C | 0.221 (84) | 3.47 (50) |

| 6 | N | C | NH | C | >6.25 | >25 |

| 7 | N | C | CH | N | 6.72 (115) | >25 |

| 8 | N | N | CH | C | 2.89 (53) | 1.11 (43) |

Data represent an average of at least two determinations. Percent efficacy is reported relative to 1.00 μM 9 and 0.200 μM S1P for hS1P1 RI and hS1P3 Ca2+ assays, respectively. (S1P demonstrates 91% efficacy relative to 1.00 μM 9 in hS1P1 RI studies.) >[Highest concentration tested] is reported for compounds that do not achieve >10% of control activity (1.00 μM 9 or 0.200 μM S1P).

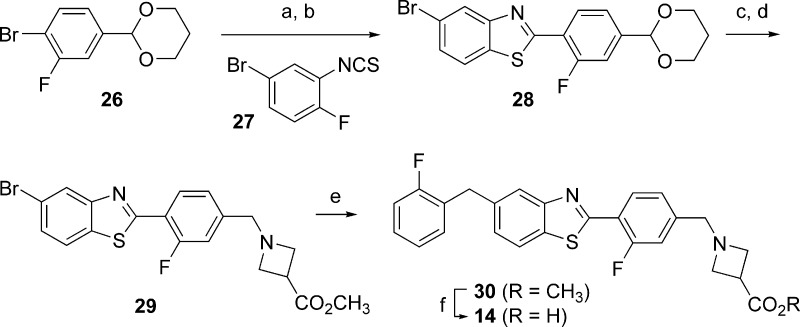

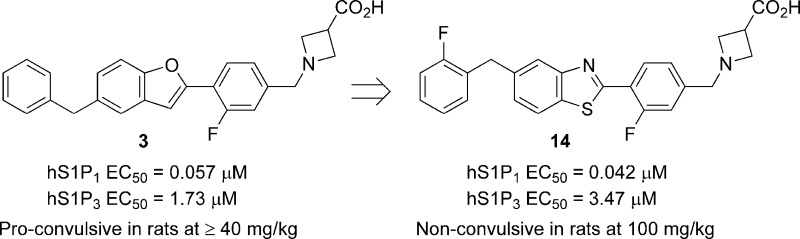

As proconvulsive activity had not been reported with prior nonisoform-selective S1P receptor agonists, such activity was tentatively assumed to be peculiar to benzofuran 3. An effort was therefore undertaken to identify closely structurally related analogues of 3 that possessed similar or improved pharmacological profiles but that were devoid of proconvulsive activity. To this end, a series of compounds was prepared wherein the benzofuran core of 3 was replaced with a range of bioisosteric heterocycles (Tables 1 and 2). Analogues wherein the benzylic substituent of the central 5,6-ring system was located para to the more electronegative substituent (“W”) of the six-membered ring were uniformly found to be less potent (4−118-fold) than 3 in the S1P1 RI assay (Table 1). In contrast, several analogues wherein the benzylic substituent was located meta to the more electronegative substituent of the six-membered ring possessed comparable or superior S1P1 activity to 3 (Table 2). Benzothiazole 11 was particularly noteworthy, as it possessed not only comparable in vitro activity to lead 3 but proved similarly active in vivo, bringing about statistically significant lymphocyte depletion upon oral dosing at 1.0 mg/kg.

Table 2. SAR of 6-Benzyl-Substituted Bicyclic Coresa.

| compd | W | X | Y | Z | hS1P1 RI EC50 (μM) (% efficacy) | hS1P3 Ca2+ EC50 (μM) (% efficacy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | O | C | CH | C | 0.013 (110) | 0.679 (42) |

| 10 | O | C | N | C | 0.094 (108) | 0.542 (87) |

| 11 | N | C | S | C | 0.042 (102) | 1.21 (24) |

| 12 | N | C | CH | N | 0.741 (110) | 6.09 (50) |

| 13 | N | N | CH | C | 1.81 (100) | 2.71 (48) |

Data represent an average of at least two determinations. Percent efficacy is reported as in Table 1.

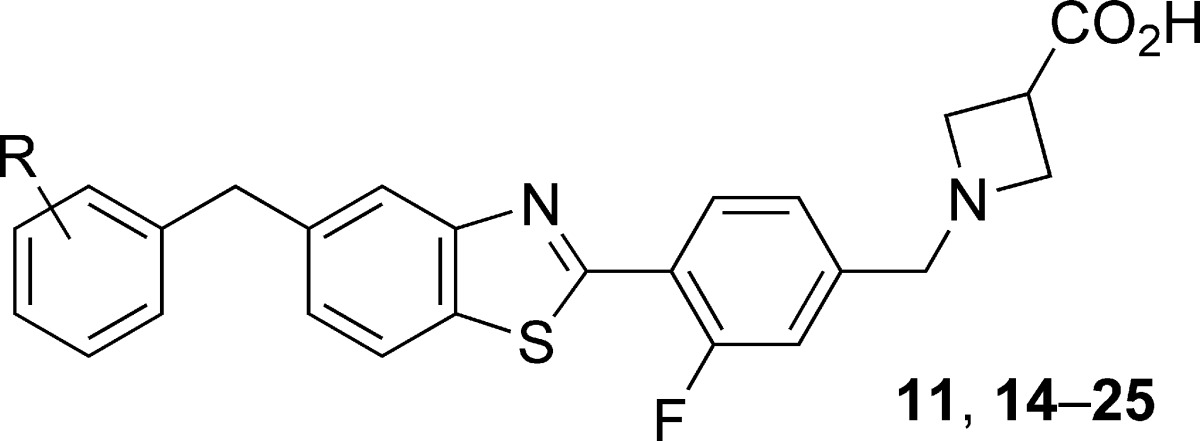

In an effort to further understand the S1P1 and S1P3 SARs of benzothiazole 11, a series of analogues was prepared wherein the terminal phenyl group of 11 was modified with a range of small lipophilic substituents (Table 3). S1P1 activity was generally maintained across these analogues; however, 4-substitution of the phenyl group with larger substituents led to moderate decreases in S1P1 activity (22, EC50 = 0.077 μM; 25, EC50 = 0.159 μM), as did 2,6-difluorination (18, EC50 = 0.126 μM). Substitution of the terminal phenyl group demonstrated a more varied effect on S1P3 activity: Whereas methylation had little impact on S1P3 activity (EC50 = 1.80−2.44 μM), chlorination led to moderate to significant decreases in S1P3 activity (EC50 = 3.88 to >25 μM), and fluorination resulted both in compounds with increased S1P3 activity (15, EC50 = 0.687 μM) and in a compound with no detectable activity at S1P3 (18, EC50 > 25 μM).

Table 3. Optimization of Benzothiazole Agonistsa.

| compd | R | hS1P1 RI EC50 (μM) (% efficacy) | hS1P3 Ca2+ EC50 (μM) (% efficacy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | H | 0.042 (102) | 1.21 (24) |

| 14 | 2-F | 0.042 (115) | 3.47 (14) |

| 15 | 3-F | 0.021 (138) | 0.687 (22) |

| 16 | 4-F | 0.033 (129) | 1.91 (37) |

| 17 | 2,4-di-F | 0.042 (186) | 1.20 (24) |

| 18 | 2,6-di-F | 0.126 (126) | >25 |

| 19 | 3,4-di-F | 0.030 (151) | 0.967 (19) |

| 20 | 2-Me | 0.026 (118) | 2.44 (40) |

| 21 | 3-Me | 0.054 (92) | >2.5 |

| 22 | 4-Me | 0.077 (132) | 1.80 (17) |

| 23 | 2-Cl | 0.042 (121) | 4.88 (41) |

| 24 | 3-Cl | 0.049 (141) | 3.88 (35) |

| 25 | 4-Cl | 0.159 (117) | >25 |

Data represent an average of at least two determinations. Percent efficacy is reported as in Table 1. >[Highest concentration tested] is reported for compounds that do not achieve >10% of control activity (1.00 μM 9 or 0.200 μM S1P).

One trend to emerge from these studies was that 2-substitution of the terminal phenyl group of 11 uniformly led to moderate, but significant, reductions in S1P3 activity. As a small lipophilic substituent proved nearly equally effective to a larger substituent in reducing S1P3 activity (cf. 14, CLog P = 4.1, and 23, CLog P = 4.6),33 we selected the least lipophilic analogue, 2-fluorobenzyl benzothiazole 14 (RI EC50 = 0.042 μM, Ca2+ EC50 = 3.47 μM), for further in vitro and in vivo profiling.34

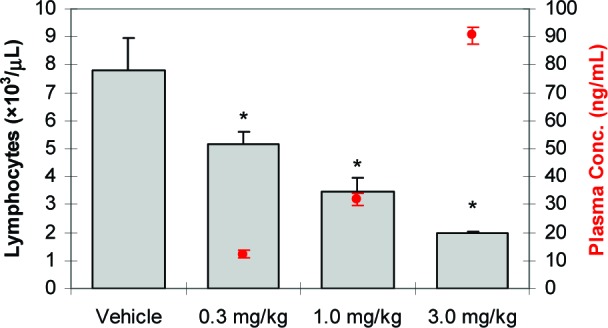

Dosed orally at 0.3, 1.0, and 3.0 mg/kg in Lewis rats, 14 produced a dose-dependent reduction in circulating blood lymphocytes 24 h postdose, consistent with S1P1 agonism (Figure 2). Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was achieved at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg (34% reduction in lymphocytes vs vehicle), and a 3.0 mg/kg dose resulted in near maximal lymphopenia (74% reduction in lymphocytes vs vehicle).35

Figure 2.

Compound 14 dosed orally reduces blood lymphocyte counts in female Lewis rats 24 h postdose (N = 5/group; bars represent average blood lymphocyte counts + SEs; circles represent average plasma concentration ± SEs; *P < 0.05 vs vehicle by ANOVA/Dunnett's multiple comparison test; vehicle = 20 % captisol, pH 2).

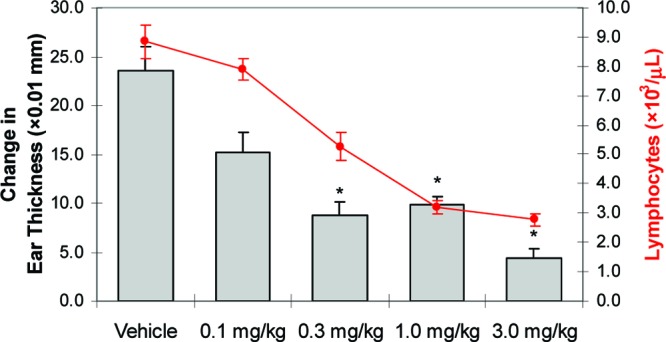

Compound 14 was subsequently investigated in a DTH antigen challenge model, an in vivo model of cell-mediated immune responses. In this study, Lewis rats were orally dosed with 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, or 3.0 mg/kg 14 or vehicle once daily over the course of 10 days. One day after initiating dosing, rats were immunized with a mixture of ovalbumin and complete Freund's adjuvant. One week later, the immunized rats were rechallenged with ovalbumin by intracutaneous injection into one ear. After an additional 2 days, differential swelling of the inoculated ear (determined by change in ear thickness) and circulating blood lymphocyte counts were measured. As seen in Figure 3, a statistically significant (P < 0.05) reduction in ear swelling was observed at doses of 0.3 mg/kg and higher. Furthermore, reduced ear swelling was found to closely track circulating lymphocyte counts, consistent with the cell-mediated etiology of the DTH immune response.

Figure 3.

Compound 14 dosed orally (qd for 10 days) reduces ovalbumin (OVA)-induced ear swelling in OVA-immunized female Lewis rats 48 h post-OVA challenge [N = 8/group (vehicle, 0.1, 0.3, and 1.0 mg/kg), N = 4/group (3.0 mg/kg); bars represent average change in ear thickness + SEs; circles represent average blood lymphocyte counts ± SEs; *P < 0.05 vs vehicle by ANOVA/Dunnett's multiple comparison test; vehicle = 20% captisol, pH 2].

Pharmacokinetic profiling of 14 in rats and nonhuman primates (Table 4) revealed 14 to possess acceptable characteristics for further development: 14 demonstrated low clearance (10−19% of liver blood flow), moderate steady state volumes of distribution (Vss = 1.6−3.3 L/kg), moderate-to-long mean residence times (3.3−10 h), and acceptable oral bioavailability (23−68%). In vitro studies established that 14 neither inhibited nor induced human cytochrome P450 enzymes, was nonmutagenic (Ames and micronucleus negative), and did not significantly inhibit the hERG channel in an electrophysiology assay (PatchXpress;36 IC50 > 10 μM).

Table 4. Pharmacokinetic Parameters for 14.

| species | Cl (L/h/kg) | Vss (L/kg) | T1/2 (h) | MRT (h) | % F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rata | 0.33 | 3.3 | 7.5 | 10 | 68 |

| NHPb | 0.50 | 1.6 | 35.2 | 3.3 | 23 |

Female Sprague−Dawley (iv: 2 mg/kg, DMSO, N = 3; po: 15 mg/kg, 20% captisol, pH 2, N = 3).

Male Cynomolgus (iv: 4 mg/kg, 20% captisol, pH 4, N = 3; po: 10 mg/kg, 20% captisol, 1% pluronic F68, 1% HPMC, pH 2, N = 3).

Cardiovascular safety studies of 14 in telemetered rats established a no-effect level for heart rate and mean arterial pressure changes of 30 mg/kg (po), indicating a wide margin for S1P3-associated cardiovascular toxicity. Most significantly, 14 did not exhibit proconvulsive activity in Sprague−Dawley rats (N = 3) at a dose of 100 mg/kg when administered orally once daily for 4 days. The exposure of 14 at the end of the fourth day (Cmax = 49 ± 10 μg/mL, AUC0−24 = 987 ± 185 μg·h/mL) was significantly higher (3-fold Cmax, 40-fold AUC0−24) than the exposure at which proconvulsive activity was observed with benzofuran 3. As the plasma free fractions37 of 14 (2.1%) and 3 (1.5%) in rat were similar, the lack of proconvulsive activity of 14 relative to 3 is currently not well understood.

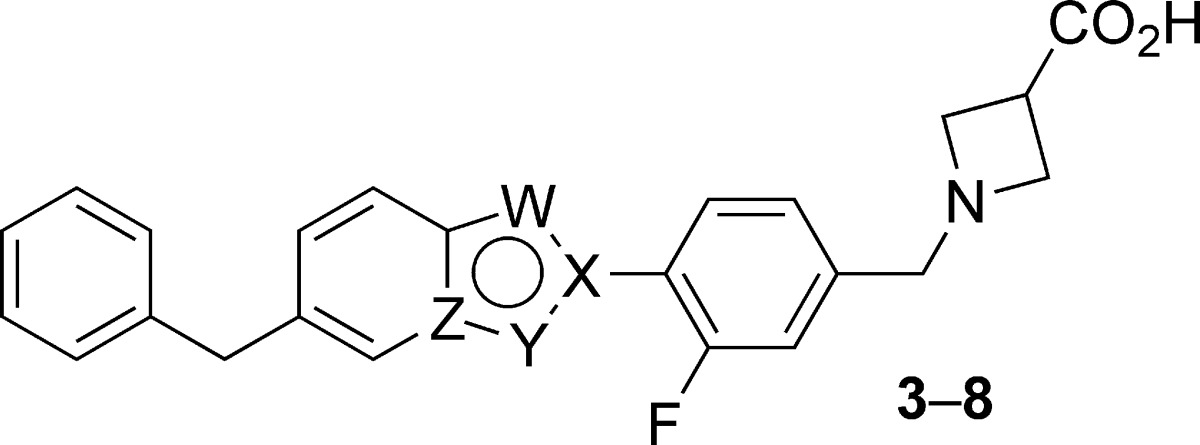

The synthesis of benzothiazole 14 is described in Scheme 1. Aryl bromide 26, prepared in one step from commercially available 3-fluoro-4-bromobenzaldehyde, was treated with n-butyllithium at −78 °C, and 2-fluoro-5-bromophenyl isothiocyanate 27 was then added to the resulting aryl lithium species, generating the corresponding thioamide. Incubation of the thioamide with a suspension of sodium carbonate in hot DMF resulted in clean cyclization to benzothiazole 28. Exposure of 28 to HCl in warm THF resulted in cleavage of the acetal protecting group; reductive amination of the resulting aldehyde subsequently provided methyl azetidine carboxylate 29. Negishi coupling of 29 with (2-fluorobenzyl)zinc chloride delivered 5-benzylbenzothiazole 30, and saponification of 30 followed by pH adjustment of the resulting reaction mixture resulted in the precipitation of benzothiazole 14 as its zwitterion.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 14.

Reagents and conditions: (a) n-BuLi, 27, THF, −78 °C, 63%. (b) Na2CO3, DMF, 110 °C, 93%. (c) 5 N HCl, THF, 55 °C, 100%. (d) Methyl azetidine-3-carboxylate hydrochloride, AcOH, DIPEA, NaBH3CN, MeOH/CH2Cl2, 71%. (e) Bis(di-tert-butyl(phenyl)phosphine) palladium dichloride (5 mol %), (2-fluorobenzyl)zinc chloride, THF, 85%. (f) LiOH, THF/H2O, then HCl and pH 6 sodium phosphate buffer, 99%.

In summary, replacement of the benzofuranyl core of a novel S1P1 agonist (3) with a series of bioisosteric heterocycles led to the identification of benzothiazole 11, which retained both the S1P1 activity and the S1P3 selectivity of 3. Subsequent substitution of the terminal phenyl group of 11 with a range of small lipophilic substituents led to the discovery of 2-fluorobenzyl benzothiazole 14, which was found to be a potent S1P1 agonist (EC50 = 0.042 μM) with reduced activity at S1P3 (EC50 = 3.47 μM). Oral dosing of 14 in rats (0.3 mg/kg) resulted in a statistically significant reduction in circulating lymphocytes 24 h postdose, as well as a statistically significant attenuation of a DTH response to antigen challenge. Furthermore, benzothiazole 14 was devoid of the proconvulsive activity of 3 at doses of up to 100 mg/kg. In vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic studies and safety studies have established that 14 possesses acceptable properties for further development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ronya Shatila and Beth Tominey for in vivo PKDM studies; Brenda Burke, Bobby Riahi, and Filisaty Vounatsos for large-scale synthesis (14 and methyl azetidine-3-carboxylate hydrochloride); and Oren Becker, Pini Orbach, Ashis Saha, and Sharon Shacham for their leadership of research efforts at EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Dilara McCauley and Ashis Saha are acknowledged for their leadership of prior studies leading to the identification of benzofuran 3.

Supporting Information Available

Statistical analysis of data presented in Tables 1−3, experimental procedures and characterization data for 3−25, and details of in vitro and in vivo assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hannun Y. A.; Obeid L. M. Principles of Bioactive Lipid Signaling: Lessons from Sphingolipids. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 9, 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A.; Mitsutake S.; Mizutani Y.; Igarashi Y. Metabolism and Biological Functions of Two Phosphorylated Sphingolipids, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate and Ceramide 1-Phosphate. Prog. Lipid Res. 2007, 46, 126–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H.; Gonzalez-Cabrera P. J.; Sanna M. G.; Brown S. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor Signaling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 743–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyster J. G. Chemokines, Spingosine-1-Phosphate, and Cell Migration in Secondary Lymphoid Organs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 23, 127–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H.; Goetzl E. J. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate and its Receptors: An Autocrine and Paracrine Network. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 560–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsolais D.; Rosen H. Chemical Modulators of Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptors as Barrier-Oriented Therapeutic Molecules. Nature Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 297–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptors in Health and Disease: Mechanistic Insights from Gene Deletion Studies and Reverse Pharmacology. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 115, 84–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardell S. E.; Dubin A. E.; Chun J. Emerging Medicinal Roles for Lysophospholipid Signaling. Trends Mol. Med. 2006, 12, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandala S.; Hajdu R.; Bergstrom J.; Quackenbush E.; Xie J.; Milligan J.; Thornton R.; Shei G.-J.; Card D.; Keohane C.; Rosenbach M.; Hale J.; Lynch C. L.; Rupprecht K.; Parsons W.; Rosen H. Alteration of Lymphocyte Trafficking by Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor Agonists. Science 2002, 296, 346–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi K.; Chiba K. FTY720 Story. Its Discovery and the Following Accelerated Development of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor Agonists as Immunomodulators Based on Reverse Pharmacology. Perspect. Med. Chem. 2007, 1, 11–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oo M. L.; Thangada S.; Wu M.-T.; Liu C. H.; Macdonald T. L.; Lynch K. R.; Lin C.-Y.; Hla T. Immunosuppressive and Anti-angiogenic Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor-1 Agonists Induce Ubiquitinylation and Proteasomal Degradation of the Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 9082–9089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M.; Lo C. G.; Cinamon G.; Lesneski M. J.; Xu Y.; Brinkmann V.; Allende M. L.; Proia R. L.; Cyster J. G. Lymphocyte Egress from Thymus and Peripheral Lymphoid Organs is Dependent on S1P Receptor 1. Nature 2004, 427, 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allende M. L.; Dreier J. L.; Mandala S.; Proia R. L. Expression of the Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor, S1P1, on T-cells Controls Thymic Emigration. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 15396–15401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabashima K.; Haynes N. M.; Xu Y.; Nutt S. L.; Allende M. L.; Proia R. L.; Cyster J. G. Plasma Cell S1P1 Expression Determines Secondary Lymphoid Organ Retention Versus Bone Marrow Tropism. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 2683–2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba K.; Yanagawa Y.; Masubuchi Y.; Kataoka H.; Kawaguchi T.; Ohtsuki M.; Hoshino Y. FTY720, a Novel Immunosuppressant, Induces Sequestration of Circulating Mature Lymphocytes by Acceleration of Lymphocyte Homing in Rats. I. FTY720 Selectively Decreases the Number of Circulating Mature Lymphocytes by Acceleration of Lymphocyte Homing. J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 5037–5044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinschewer D. D.; Ochsenbein A. F.; Odermatt B.; Brinkmann V.; Hengartner H.; Zinkernagel R. M. FTY720 Immunosuppression Impairs Effector T Cell Peripheral Homing Without Affecting Induction, Expansion, and Memory. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 5761–5770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kursar M.; Jänner N.; Pfeffer K.; Brinkmann V.; Kaufmann S. H. E.; Mittrücker H.-W. Requirement of Secondary Lymphoid Tissues for the Induction of Primary and Secondary T cell Responses Against Listeria monocytogenes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008, 38, 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka H.; Sugahara K.; Shimano K.; Teshima K.; Koyama M.; Fukunari A.; Chiba K. FTY720, Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor Modulator, Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Inhibition of T Cell Infiltration. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2005, 2, 439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino M.; Funeshima N.; Kitazawa Y.; Kimura H.; Amemiya H.; Suzuki S.; Li X.-K. Amelioration of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in Lewis Rats by FTY720 Treatment. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 305, 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba K.; Hoshino Y.; Suzuki C.; Masubuchi Y.; Yanagawa Y.; Ohtsuki M.; Sasaki S.; Fujita T. FTY720, A Novel Immunosuppressant Possessing Unique Mechanisms. I. Prolongation of Skin Allograft Survival and Synergistic Effect in Combination with Cyclosporine in Rats. Transplant. Proc. 1996, 28, 1056–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappos L.; Radue E.-W.; O'Connor P.; Polman C.; Hohlfeld R.; Calabresi P; Selmaj K.; Agoropoulou C.; Leyk M.; Zhang-Auberson L.; Burtin P. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Oral Fingolimod in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 387–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A.; Barkhof F.; Comi G.; Hartung H.-P.; Khatri B. O.; Montalban X.; Pelletier J.; Capra R.; Gallo P.; Izquierdo G.; Tiel-Wilck K.; de Vera A.; Jin J.; Stites T.; Wu S.; Aradhye S.; Kappos L. Oral Fingolimod or Intramuscular Interferon for Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 402–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See refs (21), (22), and Schmouder R.; Serra D.; Wang Y.; Kovarik J. M.; DiMarco J.; Hunt T. L.; Bastien M.-C. FTY720: Placebo-Controlled Study of the Effect on Cardiac Rate and Rhythm in Healthy Subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006, 46, 895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest M.; Sun S.-Y.; Hajdu R.; Bergstrom J.; Card D.; Doherty G.; Hale J.; Keohane C.; Meyers C.; Milligan J.; Mills S.; Nomura N.; Rosen H.; Rosenbach M.; Shei G.-J.; Singer I. I.; Tian M.; West S.; White V.; Xie J.; Proia R. L.; Mandala S. Immune Cell Regulation and Cardiovascular Effects of Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor Agonists in Rodents are Mediated via Distinct Receptor Subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 309, 758–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna M. G.; Liao J.; Jo E.; Alfonso C.; Ahn M.-Y.; Peterson M. S.; Webb B.; Lefebvre S.; Chun J.; Gray N.; Rosen H. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate (S1P) Receptor Subtypes S1P1 and S1P3, Respectively, Regulate Lymphocyte Recirculation and Heart Rate. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 13839–13848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recent research has suggested that S1P1 rather than S1P3 mediates heart rate reduction in humans: ; Gergely P.; Wallström E.; Nuesslein-Hildesheim B.; Bruns C.; Zécri F.; Cooke N.; Traebert M.; Tuntland T.; Rosenberg M.; Saltzman M. Phase I study with the selective S1P1/S1P5 receptor modulator BAF312 indicates that S1P1 rather than S1P3 mediates transient heart rate reduction in humans. Mult. Scler. 2009, 15, S125–S126. [Google Scholar]; See also ref (27).

- Brossard P.; Hofmann S.; Cavallaro M.; Halabi A.; Dingemanse J. Entry-into-Humans Study with ACT-128800, A Selective S1P1 Receptor Agonist: Tolerability, Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 85, S63–S64. [Google Scholar]

- Buzard D. J.; Thatte J.; Lerner M.; Edwards J.; Jones R. M. Recent Progress in the Development of Selective S1P1 Receptor Agonists for the Treatment of Inflammatory and Autoimmune Disorders. Expert Opin. Ther. Patents 2008, 18, 1141–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke N.; Zécri F. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Type 1 Receptor Modulators: Recent Advances and Therapeutic Potential. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2007, 42, 245–263. For reports from 2008 to the present and modeling-based approaches to rationalizing isoform selectivity, see the Supporting Information.. [Google Scholar]

- Shacham S.; Marantz Y.; Bar-Haim S.; Kalid O.; Warshaviak D.; Avisar N.; Inbal B.; Heifetz A.; Fichman M.; Topf M.; Naor Z.; Noiman S.; Becker O. M. PREDICT Modeling and In-Silico Screening for G-Protein Coupled Receptors. Proteins 2004, 57, 51–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A. K.; Yu X.; Lin J.; Lobera M.; Sharadendu A.; Cheruku S.; Schutz N.; Segal D.; Marantz Y.; McCauley D.; Buys J.; Horner M.; Salyers K.; Schrag M.; Vargas H. M.; Xu Y.; McElvain M.; Xu H.. Benzofuran-based Sphingosine-1 Phosphate Receptor-1 (S1P1) Agonists: Discovery of a Potent, Selective and Orally Bioavailable Preclinical Lead Molecule. ACS Med. Chem. Lett., in press.

- Ovalbumin/complete Freund's adjuvant. For experimental protocol, see the Supporting Information.

- ChemBioDraw Ultra, version 11.0, Cambridgesoft, 100 CambridgePark Drive, Cambridge, MA 02140.

- Dosed orally (1 mg/kg) in female Lewis rats, 14, 20, and 23 were similarly efficacious in reducing blood lymphocyte counts 24 h postdose (63−73% reduction).

- S1P1 agonists have previously been reported to produce a maximal ∼70% reduction in lymphocyte count: Hale J. J.; Lynch C. L.; Neway W.; Mills S. G.; Hajdu R.; Keohane C. A.; Rosenbach M. J.; Milligan J. A.; Shei G.-J.; Parent S. A.; Chrebet G.; Bergstrom J.; Card D.; Ferrer M.; Hodder P.; Strulovici B.; Rosen H.; Mandala S. A Rational Utilization of High-Throughput Screening Affords Selective, Orally Bioavailable 1-Benzyl-3-carboxyazetidine Sphingosine-1-phosphate-1 Receptor Agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 6662–6665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PatchXpress 7000A Automated Parallel Patch-Clamp System, Molecular Devices, 1311 Orleans Drive, Sunnyvale, CA 94089.

- Determined by ultracentrifugation at 5.0 μg/mL test compound concentration.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.