Abstract

A long tradition of research and theory on gender, marriage, and mental health suggests that marital status is more important to men’s psychological well-being than women’s while marital quality is more important to women’s well-being than men’s. These beliefs rest largely on a theoretical and empirical foundation established in the 1970s, but, despite changes in gender and family roles, they have rarely been questioned. The present analysis of three waves of a nationally representative survey indicates that, with few exceptions, the effects of marital status, marital transitions, and marital quality on psychological well-being are similar for men and women. Further, for men and women, occupying an unsatisfying marriage undermines psychological well-being to a similar extent—and, in some cases, to a greater extent—than exiting marriage or being continually unmarried.

Thirty years ago, sociologist Jessie Bernard argued that the gap in men’s and women’s marital experiences was so great as to constitute “his” and “her” marriages (Bernard 1972). Bernard further proclaimed that, “marriage introduced such profound discontinuities into the lives of women as to constitute genuine emotional health hazards” (p. 37). A year later, Gove and Tudor (1973) introduced and tested a similar theory, arguing that married women are at greater risk for mental illness than their male counterparts because the adult roles of married women are less valued and more frustrating than those of married men.

According to Bernard, the gendered nature of marriage places women in a double-bind: Although family roles are less beneficial and, in some ways, more harmful to women than men, gendered socialization processes encourage women to highly value and identify with the role of wife and mother. Therefore, marital quality should be more important to women’s mental health than to men’s, while simply being married should be more important to men’s mental health than to women’s (Gove, Hughes, and Style 1983). The idea that marriage benefits men more than women while marital quality affects women more than men forms the cornerstone of sociological research on gender, marriage, and mental health and continues to drive much of the research conducted in this area today. For the past thirty years, this idea has contributed to research and theory on a range of related topics, including explanations of marital dissolution, gender differences in mental health, the gendered division of household labor, and the physical and mental health consequences of women’s multiple roles.

Despite Bernard’s caustic assessment of the current state of marriage at the time, she speculated that shifts in marital and gender roles gaining momentum in the early 1970s could lead to a “future of marriage” that provided equal advantages to women and men. Demographic and cultural changes in the United States have, in fact, significantly altered women’s status and roles both within and outside of the family. Has the future of marriage that Bernard envisioned arrived? The present study addresses this question using panel data from three recent waves of a nationally representative survey. In addition to providing a contemporary assessment of gender differences in the effects of marital status and marital quality on psychological well-being, the analysis extends previous research in several ways. First, the effects of continuity in an unmarried status are separated from the effects of transitions into and out of marriage in order to assess potential gender differences in the processes underlying marital status differences in well-being. Second, both positive and negative dimensions of marital quality and psychological well-being are considered. Finally, the analysis examines whether being unmarried or exiting marriage through divorce or widowhood undermines psychological well-being more than being in a strained marriage, and whether these associations differ by gender.

SHIFTS IN GENDER, MARRIAGE, AND FAMILY ROLES

The dramatic changes in gender roles and family structure of the past 30 years provide an important reason for questioning the assumption of gender differences in the effects of marital status and marital quality on psychological well-being. The increase in married women’s workforce participation is especially significant. Rates of labor force participation among married women with young children almost doubled between 1970 and 1990 (from 30% to 59%; U.S. Bureau of the Census 1991). Shifts in women’s employment patterns were accompanied by delays in the timing of marriage and childbirth and declines in marital stability (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1991). These demographic changes affect the economic necessity, meaning, and experience of marriage. For example, as women’s workforce participation and relative contributions to household income increase, so does their power within the marital relationship (Ferber 1982). Changes in women’s roles may have also weakened the relative importance of marital quality to women’s well-being compared to men’s. The roles of wife and mother were once the primary adult roles available to women in the U.S. Women today have a wider range of opportunities for the fulfillment of socially accepted goals—opportunities that may include but are no longer limited to having a happy and harmonious marriage. Further, as women’s workforce participation increased, economic barriers to leaving strained marriages weakened.

RECENT EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

Gender, Marital Status, and Psychological Well-Being

A few recent studies suggest that gender differences in the association of marital status with psychological well-being have diminished. For example, some research finds no gender difference in the greater psychological well-being of the married compared to the unmarried (Ross 1995), the never-married (Horwitz and White 1991; Horwitz et al. 1996), the recently divorced (Booth and Amato 1991; Marks and Lambert 1998; Menaghan and Lieberman 1986) and the widowed (Marks and Lambert 1998). In their recent book, The Case for Marriage, Linda Waite and Maggie Gallagher (2000) summarize the evidence and conclude that marriage provides mental health benefits to both men and women.

Overall, however, research that examines the links between gender, marital status, and mental health has produced results that are inconsistent and contradictory. Some studies report that the advantages of being married compared to being never married (Williams et al. 1992), divorced (Aseltine and Kessler 1993), or experiencing a recent transition to divorce (Marks and Lambert 1998; Simon and Marcussen 1999) or widowhood (Marks and Lambert 1998) are greater for women than for men. Other research (Marks and Lambert 1998) indicates that, among older adults, being never-married undermines men’s psychological well-being more than women’s—a finding that is consistent with Bernard’s (1972) and Gove and Tudor’s (1973) earlier observations.

Inconsistencies in the research literature are likely due to a number of factors, including the analysis of cross-sectional versus longitudinal data and the conceptualization and measurement of marital status. Explanations for associations between marital status and psychological well-being typically take one of two forms. The marital resource model suggests that the greater well-being of the married compared to the unmarried is due to the greater economic resources and social support that the married enjoy. In contrast, the crisis model implies that the strains of marital dissolution undermine psychological well-being more than the resources of marriage protect it (Williams et al. 1992).

Distinguishing between the resource model and the crisis model requires separating the effects of continuity in a marital status from the effects of transitions into and out of marriage. Few recent studies of the association between gender, marital status, and well-being simultaneously distinguish between the mental health consequences of marital transitions and the effects of continuity in unmarried statuses. Although the results have been somewhat inconsistent, the limited evidence suggests that assumptions about the greater mental health benefit of marriage for men should be questioned. For example, using different analytical approaches and varying indicators of well-being, both Marks and Lambert’s (1998) and Simon’s (2002) analysis of data from the National Survey of Families and Households indicate that continuity in an unmarried status generally has similar effects on men’s and women’s psychological well-being. Furthermore, although Simon finds no gender differences in the effects of marital transitions on mental health, Marks and Lambert’s (1998) analysis suggests that transitions out of marriage in some cases undermine women’s well-being more than men’s.

In sum, several studies question the view that marital status is more important to men than to women. The results of this research, however, are too discrepant and preliminary to warrant rejection of this fundamental assumption. The present study addresses this question using a sample that has previously not been used to investigate these associations. The use of longitudinal data greatly reduces (but does not completely eliminate) the probability that observed associations of marital status with psychological well-being reflect the selection of individuals into or out of marriage based on mental health. More importantly, the present study extends previous research by assessing potential gender differences in the effects of marital quality on psychological well-being, and by investigating whether it is worse for men and women to be unmarried or to exit marriage through divorce or widowhood than to be in a strained marriage.

Gender, Marital Quality, and Psychological Well-Being

The idea that marital quality is more important to women’s mental health than to men’s is based in part on theories of gender differences in socialization. According to this argument, social norms encourage the belief among women that having a harmonious marital and family life is the highest achievement to which women can aspire (Bernard 1972). Moreover, gendered socialization practices encourage girls to place a high value on the emotional component of personal relationships (Gilligan 1982). Despite general acceptance of the greater importance of marital quality for women’s well-being compared to men, only a few recent empirical studies have directly tested this assumption (Barnett, et al.1994; Horwitz, McLaughlin, and White 1998; Simon 1995; Umberson et al. 1996). The results of this research do not offer definitive conclusions. For example, Horwitz and colleagues’ (1998) study of young adults supports the hypothesis that marital quality is more important to the psychological well-being of women than to their male counterparts. Others find that that marital role quality has similar effects on men’s and women’s well-being (Barnett et al. 1994), and qualitative research suggests that having a supportive spousal relationship is more important to men’s well-being than to women’s (Simon 1995).

Marital quality is a multidimensional construct (Glenn 1998). Positive and negative aspects of the marital relationship may have different effects on the mental health of individuals in general and on the well-being of men and women in particular (Rook 1984). With few exceptions (Horwitz et al. 1998; Umberson et al. 1996), studies of the association between marital quality and psychological well-being employ only global indicators of marital satisfaction. Yet recent research suggests that the existence of gender differences in the impact of marital quality on mental health may depend on the way that marital quality is measured (Umberson et al. 1996). The present study employs scales constructed from five indicators of marital quality to examine the influence of positive and negative dimensions of the marital relationship on men’s and women’s psychological well-being.

Gender and the Relative Effects of Marital Status and Marital Quality on Psychological Well-Being

The overwhelming evidence of the greater well-being of the married compared to the unmarried commonly leads to the conclusion that becoming and staying married maximizes adult health and well-being. That the validity of this conclusion depends on marital quality is frequently overlooked. This is not an especially novel idea. In fact, twenty years ago, Gove and colleagues (1983) observed that, for both men and women, marital quality is more important to mental health than marital status, per se. Moreover, the social stress literature suggests that stressful life events such as the transition to divorce or widowhood may have positive effects on well-being when they involve exits from stressful roles (e.g., a strained marriage) (Wheaton 1990). Despite the established importance of marital quality, the substantial research literature on marital status differences in health and well-being has, with few exceptions, developed independently of this recognition. The result is a severely cropped and, I argue, overstated representation of the positive mental health effects of marriage and the negative consequences of marital dissolution or loss.

Moreover, a misreading of previous research findings may have resulted in inaccurate conclusions about gender differences in the relative effects of marital status and marital quality on mental health. The belief that men benefit from marriage regardless of the quality of the marital relationship is pervasive in the literature (e.g., Acitelli and Antonucci 1994; Brown 2000; Tower and Kasl 1995; Walen and Lachman 2000; Nock 1998). This conclusion appears to be based entirely on the results of a single study that was not designed to test these gender differences and provided no evidence to support such a claim.1 That study, published in this journal almost 20 years ago by Walter Gove and colleagues (1983), argued that marital quality is more predictive of well-being than marital status for both men and women. Although testing the significance of gender differences was not the primary focus of their research, their analysis suggested— consistent with the implications of Bernard’s (1972) argument—that marital status may be more strongly associated with men’s well-being than women’s, while marital quality may be more strongly associated with women’s well-being than men’s. Even if such gender differences exist, this observation differs greatly from the following assertion, for which only the Gove et al. (1983) study is typically provided as evidence: “Marriage is typically an asset for men regardless of the quality of the marital union (Nock 1998:14).” Although this conclusion may be true, neither Gove’s (1983) study nor any published research since has directly tested this hypothesis.2 Such an association implies a much greater gender difference in the experience of marriage—and in its consequences for psychological well-being—than simply observing that marital status is more important to men’s mental health than to women’s. It essentially implies that marriage is so important to men’s well-being that they are better off being in a strained marriage than being unmarried. Testing this hypothesis is a final goal of the present research.

DATA AND METHODS

The data used in the present study are from three waves of the Americans’ Changing Lives survey (House 1986). Face to face interviews were conducted with a nationally representative sample of 3,617 persons ages 24 and older in 1986 residing in the contiguous United States. Of the 3,617 respondents originally interviewed in 1986, 65 percent (n = 2,348) were also interviewed in 1989 and 1994. The attrition rate for all three waves of data collection is 35 percent (n = 1,269). Mortality of respondents was responsible for 43 percent of that attrition (n = 546). Non-response was responsible for the remaining attrition (n = 723). The sample was obtained using multistage area probability sampling with an oversample of African Americans and older adults. All analyses in the present study are weighted to adjust for the oversample of special populations and sample attrition and the standard errors are adjusted for design effects.

Analytic Approach

Analyses reported here are based on a standard cross-sectional time-series or panel design. To take full advantage of the available data, the three waves of the ACL data are pooled. Data are obtained from each survey respondent at each of three time points, providing two survey waves with information on the respondent at the current survey wave and the previous wave. Because there are two observations for the 2,348 respondents who participated in all three waves of data collection, standard errors are adjusted for the clustering of observations within individuals using cross-sectional time series estimators in STATA. I also control for the number of months elapsed between the Time 1 and Time 2 measurement of the dependent variable.3

Measures

Marital status continuity and change

Dummy variables represent continuity and change between Time 1 and Time 2 in the following marital statuses: (1) continually married, (2) continually never married, (3) continually divorced or separated, (4) continually widowed, (5) married to divorced or separated, (6) married to widowed, and (7) unmarried (never-married, divorced, or widowed) to married. The number of respondents who experienced multiple marital status transitions between Time 1 and Time 2 is too small to facilitate meaningful comparisons between these groups and they are omitted from the analysis.

Marital quality

Because different dimensions of marital quality may have different effects on the well-being of men and women, two scales were constructed based on five indicators of marital quality. Factor analysis indicated that the five items represent two distinct dimensions of marital quality: (1) a positive dimension, which I label marital harmony, and (2) a negative dimension, which I label marital stress. Factor scores were obtained following varimax rotation and these scores were used to create standardized scales for each dimension of marital quality. Marital harmony consists of marital satisfaction (“Taking all things together, how satisfied are you with your marriage?”), and spousal emotional support (“How much does your spouse make you feel loved and cared for?” and “How much is s/he willing to listen when you need to talk about your worries or problems?”). Marital stress is measured with marital conflict (“How often would you say the two of you have unpleasant disagreements or conflicts?”) and marital strain (“How often do you feel bothered or upset by your marriage”). With the exception of marital conflict, which is measured on a seven-point scale, response categories for all items range from 1 to 5, with higher values indicating greater marital harmony or stress. The marital quality scales are standardized for each model estimated so that the mean equals 0 and the standard deviation equals 1 for each subsample. Models that estimate the effects of marital quality on well-being control for change in marital quality between Time 1 and Time 2, which is constructed by subtracting the Time 1 value of marital quality from the Time 2 value.

Psychological well-being

Research indicates that psychological well-being consists of at least two distinct components: (1) positive affect (e.g., happiness and life satisfaction) and (2) the relative absence of psychological distress (e.g., strain or depression) (see Ryff and Keyes 1995). Dependent variables in the present study include both depression and life satisfaction. Depression is measured with an 11-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Respondents reported how often in the past week they experienced each of the following: (1) felt depressed, (2) felt that everything done was an effort, (3) restless sleep, (4) felt happy, (5) felt lonely, (6) people were unfriendly, (7) enjoyed life, (8) poor appetite, (9) felt sad, (10) felt that people disliked me, (11) could not get “going.” Response categories include (1) never or hardly ever, (2) some of the time, and (3) most of the time. Items were scored so that higher values indicate higher levels of depression. The scores were summed and the scale was standardized (α = .83, .82, and .83 for 1986, 1989, and 1994, respectively). The CES-D is widely accepted among epidemiologists as an indicator of psychological distress in general populations and has demonstrated high reliability and validity in community surveys (Radloff 1977). Life satisfaction is measured on a seven-point scale indicating complete dissatisfaction (1) to complete satisfaction (7) with one’s life as a whole. The indicators of psychological well-being are standardized for each model estimated so that the mean equals 0 and the standard deviation equals 1 for each subsample.

Sociodemographic control variables

The Time 1 values of the following variables are controlled in all analyses: race (African American = 1), education in years, gender (female = 1), presence of a minor child in the home (1 = presence of child), annual household income in thousands of dollars, employment status (1 = employed for pay), age, and age-squared. Marital duration at Time 2 in months is controlled in models that estimate the effects of marital quality on well-being. Means and standard deviations for all variables in the analysis are presented separately for men and women in Table 1.

Table 1.

Weighted Means and Standard Deviations for Independent and Dependent Variables by Gender: U.S. Women and Men Ages 24–96 in 1986

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Mean (s.d.) |

Mean (s.d.) |

|

| Marital Status T1–T2 | ||

| Continually married | .598 (.490) |

.725 (.439) |

| Continually never-married | .062 (.243) |

.091 (.297) |

| Continually divorced | .104 (.305) |

.072 (.251) |

| Continually widowed | .132 (.339) |

.028 (.166) |

| Married to divorced / separated | .032 (.176) |

.034 (.146) |

| Married to widowed | .030 (.174) |

.010 (.083) |

| Never-married to married | .013 (.112) |

.020 (.146) |

| Divorced or widowed to remarried | .026 (.160) |

.020 (.134) |

| Psychological Well-Being | ||

| Depression T1 | .000 (1.000) |

.000 (1.000) |

| Depression T2 | .000 (1.000) |

.000 (1.000) |

| Life Satisfaction T1 | .000 (1.000) |

.000 (1.000) |

| Life Satisfaction T2 | .000 (1.000) |

.000 (1.000) |

| Marital Quality | ||

| Marital harmony T1 | .000 (1.000) |

.000 (1.000) |

| Marital harmony T2 | .000 (1.000) |

.000 (1.000) |

| Marital stress T1 | .000 (1.000) |

.000 (1.000) |

| Marital stress T2 | .000 (1.000) |

.000 (1.000) |

| Weighted n (observations) | 2,676 | 2,374 |

| Unweighted n (observations) | 3,221 | 1,829 |

RESULTS

Gender, Marital Status, Marital Transitions and Psychological Well-Being

Continually unmarried compared to continually married

If men receive greater benefits from marriage than women, then the continually married should have better psychological well-being than every category of the continually unmarried, and this difference should be greater for men. To test this hypothesis, depression and life satisfaction at Time 2 are regressed on dummy variables that distinguish the continually divorced or separated, the continually widowed, and the continually never-married from the continually married (reference category).4 Some respondents who are married or unmarried for less than five years will be included in the marital transition groups in later analyses and are excluded here. Controls are included for Time 1 values of sociodemographic variables, with the exception of income. Because it has been identified as a potential mechanism through which marital status influences health and well-being (Ross et al. 1990), controlling for income may mask true differences in the psychological well-being of the married and the unmarried.

The results shown in Panel A of Table 2 are consistent with prior research and indicate that, on average, the continually never-married, the continually divorced or separated, and the continually widowed report higher levels of depression and lower levels of life satisfaction at T2 than the continually married. Interaction terms for gender with each marital status are entered in Model 2 and Model 4 but do not reach statistical significance. The findings fail to support the hypothesis that marriage provides greater psychological benefits to men than to women. Rather, for both men and women, being continually unmarried is associated with poorer psychological well-being relative to being married.

Table 2.

Regression Coefficients (and Standard Errors) from Models Estimating the Effects of Marital Status and Marital Transitions on Psychological Well-Being: U.S. Adults Age 24– 96 in 1986 a

| T2 Depression | T2 Life Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Independent variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|

A. Continuity in an unmarried status

(compared to continually married) |

||||

| Continually never-married | .267** (.084) |

.272* (.119) |

−.199* (.079) |

−.187 (.110) |

| Continually never-married X female | --- --- |

.006 (.151) |

--- --- |

−.032 (.140) |

| Continually divorced or separated | .229** (.080) |

.402* (.163) |

−.483*** (.074) |

−.556*** (.136) |

| Continually divorced/separated X female | --- --- |

−.282 (.180) |

--- --- |

.119 (.159) |

| Continually widowed | .156* (.067) |

.232 (.144) |

−.307*** (.076) |

−.307 (.185) |

| Continually widowed X female | --- --- |

−.102 (.155) |

--- --- |

.003 (.196) |

| Female | .084 (.049) |

.115* (.057) |

.100* (.046) |

.092 (.054) |

| Constant | 1.205*** (.299) |

1.170*** (.297) |

.378 (.276) |

.389 (.277) |

| n (observations) | 4,220 | 4,220 | 4,208 | 4,208 |

|

B. Transition out of marriage

(compared to continually married) |

||||

| Married to divorced / separated | .315** (.108) |

.442** (.164) |

−.342* (.135) |

−.348 (.223) |

| Married to divorced / separated X female | --- --- |

−.249 (.211) |

--- --- |

.012 (.270) |

| Married to widowed | .361*** (.097) |

.887** (.235) |

−.396*** (.111) |

.119 (.302) |

| Married to widowed X female | --- --- |

−.614* (.295) |

--- --- |

−.607* (.322) |

| Female | −.008 (.035) |

.010 (.035) |

.038 (.041) |

.046 (.041) |

| T1 value of the dependent variable | .596*** (.023) |

.596*** (.023) |

.452*** (.025) |

.451*** (.025) |

| Constant | .418 (.244) |

.365 (.243) |

.157 (.297) |

.119 (.297) |

| n (observations) | 2,817 | 2,817 | 2,805 | 2,805 |

|

C. Transition into first marriage

(compared to continually never married) |

||||

| Never-married to married | −.317* (.146) |

−.230 (.205) |

.515*** (.146) |

.628*** (.198) |

| Never-married to married X female | --- --- |

−.202 (.279) |

--- --- |

−.266 (.263) |

| T1 value of dependent variable | .475*** (.044) |

.476*** (.044) |

.414*** (.050) |

.414*** (.049) |

| Female | −.001 (.090) |

.034 (.098) |

.015 (.089) |

.058 (.095) |

| Constant | .463 (.591) |

.415 (.598) |

−.261 (.578) |

−.312 (.580) |

| n (observations) | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 |

|

D. Transition into remarriage

(compared to continually widowed or divorced) |

||||

| Divorced or widowed to remarried | −.071 (.119) |

−.419** (.157) |

.188 (.120) |

.454** (.170) |

| Divorced or widowed to remarried X female | --- --- |

.499** (.188) |

--- --- |

−.383* (.192) |

| T1 value of dependent variable | .443*** (.043) |

.444*** (.044) |

.460*** (.040) |

.456*** (.039) |

| Female | −.100 (.081) |

−.143 (.086) |

.099 (.076) |

.131 (.078) |

| Constant | .370 (.394) |

.334 (.397) |

−.430 (.421) |

−.402 (.420) |

| n (observations) | 1,337 | 1,337 | 1,317 | 1,317 |

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001 (two-tailed tests)

With the exception of the models in Panel A, which do not include a control for income, all models include controls for the following sociodemographic variables, measured at T1: income, employment status, race, age, age-squared, education, and the presence of a minor child in the home. Also included is a control for months between the T1 and T2 measurement.

Transition out of marriage compared to continually married

I next assess potential gender differences in the effects of transitions out of marriage through divorce/separation or widowhood on change in psychological well-being. The Time 2 indicator of psychological well-being is regressed on dummy variables that indicate whether a respondent became divorced/separated or widowed between Time 1 and Time 2, or was continually married for a period of at least five years (reference category). To estimate the association of marital transitions with change in well-being, the Time 1 value of the dependent variable is controlled. Thus, for a given marital transition, a positive coefficient indicates that it is associated with an increase in well-being between Time 1 and Time 2 while a negative coefficient reflects a decrease in well-being, relative to the change experienced by the comparison group. These models also control for the Time 1 values of all sociodemographic variables. The results are shown in Panel B of Table 2.

For both dependent variables, Models 1 and 3 (Table 2, Panel B) show that the transition to divorce or separation and the transition to widowhood are associated with increases in depression and declines in life satisfaction. Models 2 and 4 indicate that the estimated effects of the transition to divorce or separation on depression and life satisfaction do not differ by gender. However, although the transition to widowhood is associated with an increase in depression for men and women, the magnitude is significantly greater among men (.887 for men; .887 − .614 = .273 for women). In contrast, the recent death of a spouse is associated with a decline in life satisfaction for women (.119 − .607 = −.488), but not for men (.119). In sum, although the transition to widowhood appears to undermine the psychological well-being of both men and women, the specific dimensions of well-being most strongly affected differ by gender.

Transitions into marriage compared to continually unmarried

If men receive greater benefits from marriage than women, transitions into marriage should be associated with increased well-being and this effect should be greater for men. I estimate lagged dependent variable models that compare the well-being of the following groups: (1) those who experience a transition into first marriage compared to the continually never-married (shown in Table 2, Panel C), and (2) those who experience a transition into remarriage compared to the continually divorced or widowed (shown in Table 2, Panel D). These models also control for the T1 values of sociodemographic variables and the dependent variable.

Whether transitions into marriage have different effects on men’s and women’s well-being depends on prior marital history. As shown in Model A (Table 2, Panel C) for each dependent variable, entering into the first marriage is associated with a decline in depression and an increase in life satisfaction. The lack of significant interactions between gender and the transition to first marriage (in Models 1 and 3) indicates that these associations are similar for men and women. However, the estimated effect of the transition to remarriage on well-being differs by gender. The significant interactions with gender in Models 2 and 4 suggest that the transition into a second or later marriage is associated with a decline in depression and an increase in life satisfaction for men only. In sum, although first marriage offers similar psychological rewards to men and women, only men appear to benefit from remarriage.

Gender, Marital Quality, and Psychological Well-Being

The next part of the analysis tests the hypothesis that marital quality is more important to women’s well-being than to men’s. Depression and life satisfaction at Time 2 are regressed on the Time 1 value of marital harmony or marital stress, the Time 1 values of the dependent variable, the sociodemographic variables, and marital duration. An indicator of marital quality change between Time 1 and Time 2 is included to control for the simultaneous effects of change in marital quality on change in psychological well-being (see Sprecher and Felmlee 1992). Further, to eliminate the possibility that observed associations between poor marital quality at Time 1 and declines in well-being between Time 1 and Time 2 are due to the subsequent divorce of those with the lowest Time 1 marital quality, the analysis is restricted to those who remained married to the same spouse between Time 1 and Time 2.

Consistent with prior research, the results shown in Models 1, 3, 5 and 7 of Table 3 indicate that marital quality is strongly associated with change in depression and life satisfaction. Lower marital harmony and greater marital stress at Time 1 appear to increase depression and undermine life satisfaction. In Models 2, 4, 6, and 8, each of the coefficients for the interaction of gender and marital quality are small, and none reach statistical significance. The results fail to support the hypothesis that the quality of the marital relationship is more important to women’s psychological well-being than to men’s. For men and women, high levels of marital stress and low levels of marital harmony undermine life satisfaction and increase depression.

Table 3.

Regression Coefficients (and Standard Errors) from Models Estimating the Effects of T1 Marital Quality on Change in Psychological Well-Being T1–T2: U.S. Adults Age 24– 96 in 1986 a

| 1994 Depression | T2 Life Satisfaction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Marital Harmony | Marital Stress | Marital Harmony | Marital Stress | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Independent variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 |

| Marital quality T1 | ||||||||

| Marital harmony | −.178*** (.030) |

−.190*** (.045) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

.406*** (.031) |

.405*** (.051) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Marital harmony X female | --- --- |

.017 (.039) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

--- --- |

.002 (.042) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Marital stress | --- --- |

--- --- |

.269*** (.035) |

.263*** (.047) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

−.416*** (.040) |

−.424*** (.054) |

| Marital stress X female | --- --- |

--- --- |

--- --- |

.008 (.038) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

--- --- |

.009 (.039) |

| Marital quality Δ T1–T2 | ||||||||

| Marital harmony change | −.173*** (.023) |

−.173*** (.023) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

.286*** (.022) |

.286*** (.022) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Marital stress change | --- --- |

--- --- |

.202*** (.024) |

.202*** (.024) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

−.236*** (.026) |

−.236* (.026) |

| T1 value of dependent variable | .555*** (.029) |

.556*** (.029) |

.547*** (.029) |

.546*** (.029) |

.349*** (.030) |

.349*** (.030) |

.409*** (.028) |

.409*** (.028) |

| Female | −.029 (.037) |

−.028 (.036) |

.005 (.034) |

.005 (.033) |

.166*** (.041) |

.166*** (.040) |

.078* (.039) |

.078* (.039) |

| Constant | 1.078*** (.247) |

1.074*** (.246) |

1.045*** (.234) |

1.046*** (.233) |

.105 (.292) |

.105 (.291) |

.250 (.285) |

.251 (.285) |

| N (observations) | 2,492 | 2,492 | 2,477 | 2,477 | 2,485 | 2.485 | 2,485 | 2,485 |

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001 (two-tailed tests)

All models include controls for the following sociodemographic variables, measured at T1: income, employment status, race, age, age-squared, education, marital duration, and the presence of a minor child in the home. Also included is a control for months between the T1 and T2 measurement.

Gender and Relative Effects of Marital Status and Marital Quality on Psychological Well-Being

Some scholars theorize that men benefit from marriage regardless of the quality of the marital relationship (e.g., Nock 1998). The next part of the analysis addresses the following questions: (1) Do the continually unmarried have better or worse psychological well-being than those in troubled marriages? (2) Is psychological well-being more or less negatively affected by remaining in an unhappy marriage than by exiting such a marriage through divorce, separation, or widowhood? and (3) Do the answers to questions (1) and (2) above differ for men and women?

Continually married compared to continually unmarried

To address the first question, internal moderator models test whether well-being differences between the continually unmarried and the continually married depend on the level of marital quality reported by the continually married at Time 1. The construction of internal moderators requires that the group to which the moderator (i.e., standardized Time 1 marital quality) applies—in this case, the continually married—be coded as 1. This internal moderator term, as well as the indicator of marital quality change between Time 1 and Time 2, is constructed by assigning a value of zero (the mean) for all continually unmarried respondents (i.e., the reference category).5 Preliminary models indicated that the results did not substantially differ when either marital harmony or marital stress was used to assess marital quality. Only the results using marital harmony are presented here.

The results are shown in Panel A of Table 4. Turning first to depression, the significant coefficient for marital status in Model 1 indicates that continually married respondents with average levels of marital harmony are less depressed than their unmarried counterparts. However, the significant interaction between marital status and marital quality suggests that the advantage of being married compared to being unmarried diminishes as marital harmony declines. Model 2 introduces an interaction term to test for gender differences in the role of marital quality in moderating the association between marital status and well-being. This interaction is not distinguishable from zero and indicates that the relative effects on depression of marital quality versus being continually unmarried do not differ for men and women.

Table 4.

Regression Coefficients (and Standard Errors) from Models Estimating the Relative Effects on Psychological Well-Being of Being Continually Unmarried or Exiting Marriage Versus Being Continually Married with Poor Marital Quality: U.S. Adults Age 24– 96 in 1986 a

| T2 Depression | T2 Life Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Independent variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| A. Continuity in an unmarried status b | ||||

| Continually married | −.229*** (.050) |

−.237** (.091) |

.349*** (.048) |

.254** (.085) |

| Continually married X T1 marital harmony | −.351*** (.031) |

−.351*** (.050) |

.462*** (.026) |

.463*** (.043) |

| Continually married X female | --- --- |

.012 (.103) |

--- --- |

.157 (.099) |

| Continually married X T1 marital harmony X female | --- --- |

.000 (.055) |

--- --- |

.004 (.048) |

| Female | −.017 (.048) |

−.026 (.090) |

.214*** (.043) |

.097 (.087) |

| Continually married X marital harmony Δ T1–T2 | −.234*** (.026) |

−.235*** (.026) |

.309*** (.021) |

.310*** (.021) |

| Constant | 1.678*** (.273) |

1.682*** (.278) |

−.148 (.2405 |

−.102 (.247) |

| n (observations) | 4,203 | 4,203 | 4,192 | 4,192 |

| B. Transitions out of Marriage c | ||||

| Married to divorced/separated | .436** (.163) |

.435** (.164) |

−.333 (.213) |

−.334 (.211) |

| Married to div./sep. X female | −.126 (.240) |

−.131 (.239) |

−.001 (.255) |

−.028 (.284) |

| Married to div./sep. X T1 marital harmony | .234* (.083) |

.249 (.161) |

−.202* (.100) |

−.139 (.180) |

| Married to div./sep. X female X T1 marital harmony | –-- --- |

−.025 (.184) |

--- --- |

−.098 (.220) |

| Married to widowed | .832*** (.275) |

.701*** (.170) |

.323 (.314) |

.412 (.392) |

| Married to widowed X female | −.542* (.268) |

−.415* (.190) |

−.878** (.335) |

−.967* (.406) |

| Married to widowed X T1 marital harmony | .180* (.074) |

.436* (.209) |

−.485*** (.091) |

−.644 (.442) |

| Married to widowed X female X T1 marital harmony | --- --- |

−.278 (.261) |

--- --- |

.168 (.451) |

| T1 marital harmony | −.157*** (.024) |

−.162*** (.038) |

.339*** (.025) |

.334*** (.042) |

| T1 marital harmony X female | --- --- |

.009 (.040) |

--- --- |

.009 (.044) |

| Female | −.038 (.038) |

−.038 (.038) |

.182*** (.042) |

.182*** (.042) |

| T1 value of dependent variable | .531*** (.026) |

.531*** (.026) |

.308*** (.026) |

.309*** (.026) |

| Constant | .534* (.248) |

.527* (.248) |

−.106 (.291) |

−.101 (.290) |

| n (observations) | 2,795 | 2,795 | 2,783 | 2,783 |

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001 (two-tailed tests)

With the exception of models in Panel A, which do not include a control for income, all models include controls for the following sociodemographic variables, measured at T1: income, employment status, race, age, age-squared, education, and presence of a minor child in the home. Also included is a control for months between the T1 and T2 measurement and change in marital quality T1–T2 among the continually married.

The reference category in Panel A is the continually unmarried, which includes the continually divorced or separated, the continually widowed, and the never-married.

The reference category in Panel B is the continually married.

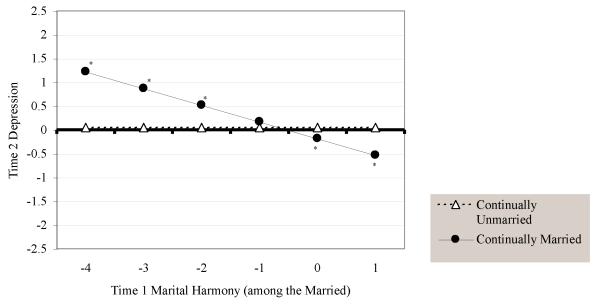

These results are summarized in Figure 1, which was constructed by calculating the predicted value of the dependent variable for: (1) the continually unmarried and (2) the continually married at various levels of marital quality, within the range of the data (i.e., 3 standard deviations below the mean through 1 standard deviation above the mean).6 Figure 1 shows that continually married men and women with low levels of marital harmony at Time 1 (1 standard deviation below the mean and lower) are significantly more depressed three to five years later than their unmarried counterparts. The only situation in which marriage appears to confer psychological benefits relative to being unmarried is when marital quality is at its highest levels.

FIGURE 1. Estimated Time 2 Depression among the Continually Married and Continually Unmarried by Time 1 Marital Quality of the Married.

Notes : Because the coefficients for “Married X female” and “Married X female X marital harmony” are not significant, associations shown here are based on results from Model 1 (Table 4, Panel A. Model controls for gender, age, race, presence of a minor child in the home, education, employment status, and months elapsed between Time 1 and Time 2.|

* Indicates marital status differences in depression are significant at p <= .05 for a given level of Time 1 marital harmony (among the married).

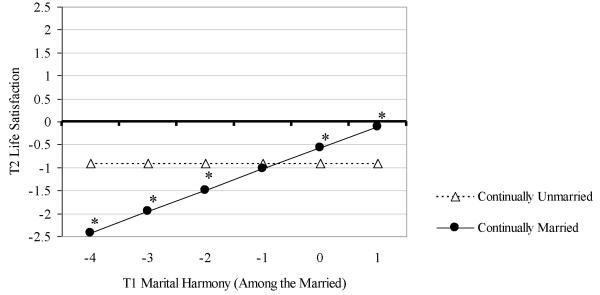

The estimated relative effects of marital status and marital quality on life satisfaction follow a similar pattern, summarized in Figure 2. Men and women who remain continually married despite low levels of marital harmony at Time 1 report significantly lower life satisfaction at Time 2 than their unmarried counterparts. It is only those married individuals who have average or high levels of marital quality (i.e., mean or mean + 1 standard deviation.) who are more satisfied with their lives at Time 2 than the unmarried. In Model 4 (Table 4, Panel A), the coefficient for the interaction of gender, marital status, and marital harmony is small and does not reach statistical significance. In sum, the results for both depression and life satisfaction indicate that, for men and women, it is better to be continually unmarried than to continually occupy even a moderately unsatisfying marriage.

Figure 2. Estimated T2 Life Satisfaction Among the Continually Married and Continually Unmarried by T1 Marital Quality of the Married a.

a Because the coefficients for “married X female” and “married X female X marital harmony” are not significant, associations shown here are based on results from Model A (Table 4, Panel A, Depression column). Model controls for gender, age, race, presence of a minor child in the home, education, employment status, and months elapsed between T1 and T2.

* Indicates marital status differences in life stisfaction are significant at p<=.05 for a given level of T1 marital harmony (among the married).

Continually married compared to transitions out of marriage

A slightly different approach is employed in estimating the relative effects of marital quality versus exiting marriage through divorce, separation, or widowhood. Marital quality at Time 1 may not only influence the psychological well-being of the continually married, but it may also partly determine whether exits from marriage undermine well-being (Wheaton 1990). The models shown in Panel B of Table 4 test whether psychological well-being is more negatively affected by remaining in an unsatisfying marriage or by exiting such a marriage through divorce, separation, or widowhood. I continue the procedure of controlling for change in marital quality between Time 1 and Time 2 among the continually married. Furthermore, because the analysis includes those who experience a change in marital status between Time 1 and Time 2, the Time 1 value of the dependent variable is controlled. Results presented previously indicate that the effect of the transition to widowhood on specific indicators of well-being differ for men and women. Therefore, the interaction term for gender by each marital transition are included.

Results are presented in Panel B of Table 4. Turning first to the Depression column, the positive coefficients for the interaction of each marital transition (i.e., married to divorced/separated and married to widowed) with marital quality indicate that, as Time 1 marital harmony declines, the increase in depression associated with the transition to divorce or separation (−1 * .234) and the transition to widowhood (−1 * .180) diminishes. Similarly, for life satisfaction, as marital harmony declines, the decrease in life satisfaction associated with the transition to divorce or separation (−1 * − .202) and the transition to widowhood (−1 * −.485) diminishes. The interaction of gender, marital status, and marital quality is introduced in Models 2 and 4 to determine whether the relative effects of exiting marriage as conditioned by marital quality differ for men and women. The coefficients for these interactions are small and nonsignificant.

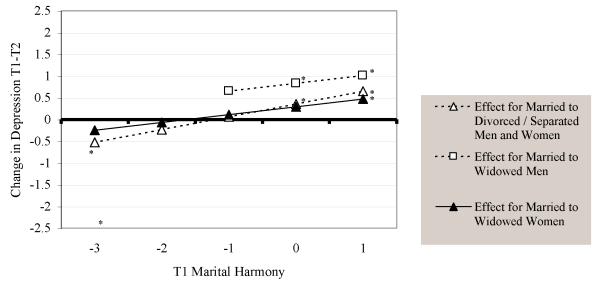

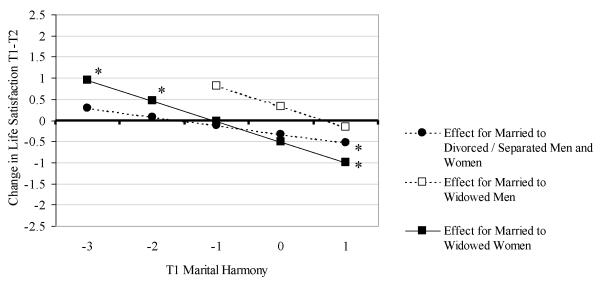

The implications of these findings for marital status differences in depression and life satisfaction are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. These figures show, at various levels of marital quality (within the range of the data), the estimated change in well-being associated with a transition out of marriage that cannot be attributed to maturation alone (i.e., the estimated change shown is net of the change estimated for the continually married comparison group). Values are plotted at each level of marital quality by first calculating the predicted value of Time 2 depression, controlling for Time 1 depression, among the group exiting marriage and the continually married. The net change in the dependent variable associated with a transition out of marriage (i.e., the estimated effect of the transition) is then calculated by subtracting the predicted value of the dependent variable among the continually married from the predicted value of the dependent variable for those exiting marriage. A point plotted above the zero axis indicates that, at a given level of marital quality, exiting marriage is associated with an increase in depression or life satisfaction, and a point plotted below the zero axis indicates that exiting marriage is associated with a decline in depression or life satisfaction.

Figure 3. Estimated Effect of Exiting Marriage T1-T2 on Change in Depression by T1 Marital Quality and Gender a.

a Because the coefficients for “marital transition X female X T1 marital harmony” are not significant, associations shown here are based on results from Model A (Table 4, Panel B, Depression column). Model controls for gender, age, race, presence of a minor child in the home, education, employment status, income, T1 life satisfaction, and months elapsed between T1 and T2.|

* Estimated effect of marital transition on change in depression is significant at p<=.05 for the given level of T1 marital harmony.

Figure 4. Estimated Effect of Exiting Marriage T1-T2 on Change in Life Satisfaction by T1 Marital Quality and Gender a.

a Because the coefficients for “marital transition X female X T1 marital harmony” are not significant, associations shown here are based on results from Model B (Table 4, Panel B, Life Satisfaction column). The regression line estimating the effect of the transition to divorce as moderated by marital quality is identical for men and women. Model controls for gender, age, race, presence of a minor child in the home, education, employment status, income, T1 life satisfaction, and months elapsed between T1and T2.

* Estimated effect of marital transition on change in life satisfaction is significant at p<=.05 for a given level of T1 marital harmony.

The most significant pattern in Figure 3 is the following: When Time 1 marital quality is poor, those who exit marriage through divorce, separation, or widowhood do not report significantly greater increases in depression than the continually married. In fact, among men and women with the lowest levels of Time 1 marital quality, exiting marriage through divorce or separation is associated with a decline in depression compared to remaining married. Whether a similar effect exists for the transition to widowhood cannot be determined because very few recently widowed men had poor marital quality at Time 1. In sum, exiting marriage increases depression only when Time 1 marital quality is relatively high

The results for life satisfaction are summarized in Figure 4. Because the regression lines for the transition to divorce for men and women were nearly identical, they are plotted with a single line. Figure 4 shows that it is only when Time 1 marital quality is very high (1 standard deviation above the mean) that exiting marriage through divorce, separation, or widowhood undermines life satisfaction compared to remaining in an unsatisfying marriage. When marital quality is lower than the mean—and even when it is at the mean—women and men who divorce or become widowed between Time 1 and Time 2 do not experience greater declines in life satisfaction than their counterparts who remain in their unsatisfying marriages. In fact, among women with poor Time 1 marital quality, the transition to widowhood is associated with increased life satisfaction.

DISCUSSION

Jessie Bernard’s critical assessment of the state of marriage in the 1970s was tempered by her hope that shifts in women’s roles, both within and outside of the home, might bring about a “future of marriage” that offered equal benefits to women and men. Has this “future of marriage” arrived? The results of the present study suggest that it has. Being in a satisfying, supportive marriage offers similar benefits to women and men, and exiting such a marriage or being in a strained marriage confers similar costs. It is unclear whether this present state of marriage is a product of recent changes in women’s status and economic opportunities, or whether it existed all along. The empirical evidence presented by Bernard in her classic work was certainly limited (Waite and Gallagher 2000), and methodological advances have improved our ability to address these questions. Regardless of their empirical support at the time, Bernard’s ideas have profoundly influenced the ways that individuals understand and interpret the experience of marriage in everyday life. The idea that marriage is bad for women and good for men fits so well with sociological knowledge about the history of gender stratification that it has rarely been questioned. Research presented here indicates that, with few exceptions, continued acceptance of the existence of gender differences in the effects of marital status and marital quality on psychological well-being is unwarranted.

Do Men Receive Greater Psychological Benefits from Marriage than Women?

Sociological theories that attempt to explain marital status differences in mental and physical health focus either on the resources that marriage provides or on the strains of exiting marriage. The present results suggest that, although both explanations contribute to marital status differences in psychological well-being, gender differences primarily reflect the short-term strains experienced by those who exit marriage, especially through widowhood. With the exception of remarriage, which appears to be more advantageous to men, women and men receive similar psychological benefits from being and remaining married.

Notably, support for Bernard’s classic hypothesis of the “his” and “her” marriage is observed only when considering a form of marriage that has recently gained prevalence. The observation that remarriage improves men’s well-being but not women’s is an exception to the conclusion that marriage provides similar psychological benefits to men and women. Remarriage can involve strains associated with blending two families, particularly when one or both spouses have children (Whitsett and Land 1992). Gender differences in the benefits of remarriage may reflect the persistence of gender roles, which continue to give women much of the responsibility for caregiving and forging interpersonal bonds, in this case between members of the new blended family. Overall, however, very little is known about the process of remarriage and its influence on men’s and women’s mental health. More research should be devoted to understanding this process and to identifying the structural, personal, and family-level characteristics that influence the ease with which both men and women transition into a second or later marriage.

A potential limitation of the present research is the inability to assess gender differences in styles of expressing emotional distress. Socialization processes encourage women to internalize distress, a process that can result in depression. In contrast, men are more likely to externalize distress through behavior such as alcohol or substance abuse (Horwitz and Davies 1994). Therefore, studies of the emotional consequences of marriage that include only depression as an outcome are likely to find that marital transitions have stronger effects on women’s well-being than on men’s. Because prior research and theory suggest that any gender differences that exist are in the opposite direction (i.e., that marriage is more important to men’s well-being than to women’s), the inability to consider alcohol abuse as an outcome in the present study should not bias the results. In fact, the present study provides no evidence that women are more likely than men to respond to the transition to divorce or to the state of being unmarried with increased depression. Moreover, the transition to widowhood appears to increase depression among men but not women.

The present findings contrast somewhat with Simon’s (2000) recent study that uses data from the National Survey of Families and Households to examine the impact of marital transitions on depression and alcohol abuse. In contrast to the present findings of no gender differences in the effects of the transition to divorce on well-being, Simon (2000) finds that it actually increases women’s depression more than men’s. Further, although the present study finds that remarriage reduces depression among men but not women, Simon (2000) finds no gender difference. These inconsistencies likely result in part from differences in the timing of important control variables in each study. Simon’s (2002) study controls for T2 measures of two key variables that are likely to be affected by marital transitions: parental status (i.e., the presence of minor children in the home) and household income. In contrast, models in the present study include controls for the T1 measures of these variables. Therefore, Simon’s results estimate the consequences that marital transitions would have for mental health if they did not affect T2 income or T2 living arrangements of children (i.e., if the recently divorced or separated/remarried did not differ from the continuously married/continuously unmarried on these variables).

For example, Simon’s findings regarding no gender difference in the effect of remarriage on depression indicate that the transition to remarriage would not be more strongly associated with men’s depression levels than with women’s if the recently remarried and continually divorced or separated had similar levels of income and were equally likely to have minor children in the home at T2. In contrast, the present study focuses on the more global effects of marital transitions on mental health (which include those effects that operate through the mechanisms controlled in Simon’s study). Recognizing that the recently remarried likely differ from the continually unmarried in the living arrangements of children and household income, the present study indicates that remarriage offers greater psychological benefits to men than to women.7 More importantly, however, the present study goes beyond previous work by showing that, for both women and men, the effect of exits from marriage on well-being depends greatly on prior marital quality.

Is Marital Quality More Important to Women’s Psychological Well-Being than to Men’s?

In contrast to theories that emphasize women’s greater attention to the affective dimensions of personal relationships, I find no evidence that the quality of the marital relationship is more important to women’s well-being than to men’s. For both men and women, positive and negative dimensions of marital quality have strong and consistent effects on psychological well-being. However, some caution is urged in generalizing these results beyond the group examined here (i.e., those who remain married for a period of at least three years following the initial assessment of marital quality). Individuals who divorce or separate between Time 1 and Time 2 generally report lower levels of marital quality at Time 1 than those who remain married. The present analysis may produce conservative estimates of the impact of poor marital quality on psychological well-being because it necessarily excludes those likely to have the lowest marital quality at Time 1. Further, although every attempt was made to control for variables that affect both psychological well-being and the probability of staying married, the existence of unmeasured variables may introduce selection bias.

Is It Better to Be Unmarried or to Exit Marriage Than to Be in a Bad Marriage?

Much recent research on the mental and physical health consequences of marriage and marital dissolution leads to the conclusion that being married is generally advantageous compared to being divorced, widowed, or never-married. In contrast, the present analysis indicates that this conclusion applies only to those in happy marriages. Indeed, the results suggest that it is better to be unmarried for at least 5 years than to remain in an unhappy marriage. Further, the strains of exiting a problematic marriage do not undermine psychological well-being to a greater extent than remaining in such a marriage. Both of these conclusions appear to apply equally to men and women. In the absence of empirical evidence, we should be reasonably skeptical of the assumption that it is better for men to be in a strained marriage than to be unmarried.

These observations should not be interpreted as an endorsement of divorce. Because the analysis controls for changes in marital quality between Time 1 and Time 2, it assumes that continually married people who have poor marital quality at Time 1 continue to have poor marital quality across the time period considered. Clearly, both positive and negative evaluations of marriage change over time. Those who remain married despite poor marital quality may do so in part because their marriage improves. For these couples, riding out the rough spots of marriage likely offers many advantages. However, improved marital quality is not the only reason that couples in troubled marriages stay together. Barriers to divorce such as financial constraints, the presence of young children in the home, or religious beliefs may keep persistently troubled marriages intact (Knoester and Booth 2000). The present analysis suggests that, in the short-run, remaining in a such a marriage undermines psychological well-being to a similar extent as the transition to divorce; in the long-run, it may result in even greater depression and lower life satisfaction than being unmarried.

CONCLUSION

Perhaps the most important conclusion suggested by the present research is the following: The marital relationship confers both resources and strains, and it is the relative balance of these factors that most strongly determines the effects of marriage on the psychological well-being of women and men. Research that compares the married and the unmarried on a range of outcomes (e.g., psychological well-being, physical health, mortality) rarely considers that these associations are highly dependent on the context in which particular marriages are experienced. The present findings clearly indicate that the effects of marital status and marital transitions on mental health—for both men and women—cannot be adequately assessed without considering the quality of the marital relationship.

Biography

Kristi Williams is Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Ohio State University and Research Associated at the Ohio State University Initiative in Population Research. Her research examines the influence of family and other personal relationships on mental and physical health, with a particular focus on gender and life course variations in these processes.

Footnotes

Each of the studies mentioned cites the Gove et al. (1983) article as evidence.

A search of articles published between 1983 and 2002 indexed in Sociological Abstracts, Social Science Citation Index, and PsychINFO revealed no research that directly examines this question.

Using separate models to estimate (1) the effects of marital patterns between 1986 and 1989 on 1989 well-being and (2) the effects of marital patterns between 1989 and 1994 on 1994 well-being produces results that are comparable to those using the pooled data presented here. In both approaches, coefficients are of a similar magnitude and in the same direction.

Unlike subsequent models that estimate the effects of marital transitions on change in well-being, this model does not include a control for Time 1. There is little reason to suspect that the well-being of the continually unmarried changes at a different rate than that of the continually married.

Preliminary analyses indicated that combining the continually never-married, continually divorced or separated, and the continually widowed into a single “continually unmarried” reference category does not produce substantially different results than considering each unmarried status separately.

Because gender differences in the relative effects of marital status and marital quality are small and nonsignificant, Figure 1 is based on results shown in Model 1 (Table 4, Panel A). This regression equation is used to calculate y at each level of marital quality, with model-specific means entered for all control variables.

Time 1 values of income, parental status, and other sociodemographic variables are controlled in the present study. This approach reduces the probability that selection into or out of particular marital statuses based on these pre-existing characteristics explains observed associations of marital transitions with mental health.

This research was supported in part by a National Institute on Aging Specialized Training Grant (2T32AG00243, University of Chicago, Center on Demography and Economics of Aging). Thanks to Michelle Frisco, R. Kelly Raley, Ross Stolzenberg, Linda Waite and, especially, Debra Umberson for their comments on earlier versions of this paper. I also thank James House for permission to use the 1994 wave of the Americans’ Changing Lives survey. Direct correspondence to Kristi Williams, Department of Sociology, 300 Bricker Hall, 190 N. Oval Mall, The Ohio State University, Columbus OH 43210.

REFERENCES

- Acitelli Linda K., Antonucci Toni C. Gender Differences in the Link Between Marital Support and Satisfaction in Older Couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:688–98. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aseltine Robert H., Jr., Kessler Ronald C. Marital Disruption and Depression in a Community Sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34:237–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett Rosalind C., Brennan Robert T., Raudenbush Stephen W., Marshall Nancy L. Gender and the Relationship between Marital–Role Quality and Psychological Distress: A Study of Women and Men in Dual–Earner Couples. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1994;18:105–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard Jessie. The Future of Marriage. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Booth Alan, Amato Paul R. Divorce and Psychological Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:396–07. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Susan L. Union Transitions among Cohabitors: The Significance of Relationship Assessments and Expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:833–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ferber Marianne A. Labor Market Participation of Young Married Women: Causes and Effects. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1982;44:457–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan Carol. In a Different Voice. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn Norval D. Problems and Prospects in Longitudinal Research on Marriage: A Sociologist’s Perspective. In: Bradbury Thomas., editor. The Developmental Course of Marital Dysfunction. Cambridge University. Press; New York: 1998. pp. 427–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gove Walter R., Hughes Michael, Style Carolyn Briggs. Does Marriage Have Positive Effects on the Psychological Well–Being of the Individual?”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:122–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gove Walter R., Tudor Jeannette F. Adult Sex Roles and Mental Illness. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78:812–35. doi: 10.1086/225404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild Arlie Russell. The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home. Viking; New York, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz Allan V., Davies Lorraine. Are Emotional Distress and Alcohol Problems Differential Outcomes to Stress? An Exploratory Test. Social Science Quarterly. 1994;75:607–21. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz Allan V., McLaughlin Julie, White Helene Raskin. How the Negative and Positive Aspects of Partner Relationships Affect the Mental Health of Young Married Persons. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1998;39:124–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz Allan V., White Helene Raskin, Howell-White Sandra. The Use of Multiple Outcomes in Stress Research: A Case Study of Gender Differences in Response to Marital Dissolution. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:278–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House James S. American’s Changing Lives: Wave I [machine readable data file] Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Knoester Chris, Booth Alan. Barriers to Divorce: When Are They Effective? When Are They Not?”. Journal of Family Issues. 2000;21:78–99. [Google Scholar]

- Marks Nadine F., Lambert James K. Marital Status Continuity and Change Among Young and Midlife Adults: Longitudinal Effects on Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Family Issues. 1998;19:652–87. [Google Scholar]

- Menaghan Elizabeth G., Lieberman Morton A. Changes in Depression Following Divorce: A Panel Study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:319–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nock Steven L. Marriage in Men’s Lives. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff Lenore S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rook Karen. The Negative Side of Social Interaction: Impact on Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:1097–1108. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E. Reconceptualizing Marital Status as a Continuum of Social Attachment. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:129–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E., Mirowsky John, Goldsteen Karen. The Impact of Family on Health: The Decade in Review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:1059–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff Carol D., Keyes Corey L. M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon Robin W. Gender, Multiple Roles, Role Meaning, and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:182–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ------ Revisiting the Relationships among Gender, Marital Status, and Mental Health. American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107:1065–96. doi: 10.1086/339225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon Robin W., Marcussen Kristen. Marital Transitions, Marital Beliefs, and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:115–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher Susan, Felmlee Diane. The Influence of Parents and Friends on the Quality and Stability of Romantic Relationships: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Investigation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:888–900. [Google Scholar]

- Tower Roni B., Kasl Stanislav V. Depressive Symptoms across Older Spouses and the Moderating Effect of Marital Closeness. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:625–38. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Chen Meichu D., House James S., Hopkins Kristine, Slaten Ellen. The Effect of Social Relationships on Psychological Well-Being: Are Men and Women Really So Different?”. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:837–57. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census . Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1991. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C.: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J., Gallagher Maggie. The Case for Marriage: Why Married People are Happier, Healthier, and Better off Financially. Doubleday; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walen Heather R., Lachman Margie E. Social Support and Strain from Partner, Family, and Friends: Costs and Benefits for Men and Women in Adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2000;17:5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton Blair. Life Transitions, Role Histories, and Mental Health. American Sociological Review. 1990;55:209–23. [Google Scholar]

- Whitsett Doni, Land Helen. Role Strain, Coping, and Marital Satisfaction of Stepparents. Families in Society. 1992;73(2):79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R., Takeuchi David T., Adair Russell K. Marital Status and Psychiatric Disorders among Blacks and Whites. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992;33:140–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]