Abstract

HPV vaccination rates among adolescents in the United States lag behind some other developed countries, many of which routinely offer the vaccine in schools. We sought to assess mothers’ willingness to have their adolescent daughters receive HPV vaccine at school. A national sample of mothers of adolescent females ages 11–14 completed our internet survey (response rate = 66%). The final sample (n = 496) excluded mothers who did not intend to have their daughters receive HPV vaccine in the next year. Overall, 67% of mothers who intended to vaccinate their daughters or had vaccinated their daughters reported being willing to have their daughters receive HPV vaccine at school. Mothers were more willing to allow their daughters to receive HPV vaccine in schools if they had not yet initiated the vaccine series for their daughters or resided in the Midwest or West (all p < .05). The two concerns about voluntary school-based provision of HPV vaccine that mothers most frequently cited were that their daughters’ doctors should keep track of her shots (64%) and that they wished to be present when their daughters were vaccinated (40%). Our study suggests that most mothers who support adolescent vaccination for HPV find school-based HPV vaccination an acceptable option. Ensuring communication of immunization records with doctors and allowing parents to be present during immunization may increase parental support.

Keywords: HPV vaccine, Vaccination program, Parents, School health, School-based health center

1. Introduction

Widespread uptake of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine has the potential to prevent the majority of cervical cancer cases [1]. As cervical cancer disproportionately affects minority, rural, and low income women [2,3], vaccination is particularly important for these groups. National guidelines recommend routine HPV vaccination for girls ages 11 or 12 and catch-up doses for females ages 13–26 who have not yet been vaccinated [4]. However, as of 2009, only 44% of eligible girls ages 13–17 in the United States have received at least one dose of HPV vaccine, and 27% have received all three doses [5].

School-based provision of HPV vaccine in other countries has proven successful at achieving broad coverage. In the first year after HPV vaccine was added to existing school immunization programs, parts of Australia achieved initiation rates of over 80% among female students ages 12–18 [6-8]. In parts of Australia with follow-up data, fewer students completed all three doses, but coverage still remained sizeable, generally ranging from 60 to 75% [6-8]. In British Columbia, Canada, 65% of eligible 11-year-old girls received the first dose of HPV vaccine when it was offered through a publicly funded school-based vaccine program [9]. The United Kingdom and Sweden have also successfully begun offering HPV vaccination through school health programs [10,11].

Clearly, the U.S. has a more complex, fragmented health care delivery system than these other countries. As such, billing and insurance issues pose an impediment to broader school-based immunization programs as do costs to schools and health departments for implementing such programs. In the U.S., school-based health care varies widely by state, and even within states, from nonexistent care to comprehensive health programs offered by school health centers. In a national study of U.S. schools, only 14% regularly offered any kind of vaccination for students [12]. Although most schools with comprehensive school health centers offer vaccinations [13], only 6% of school districts nationwide have at least one school health center of that nature [12].

Nonetheless, increasing the prevalence of U.S. school-based vaccination programs might improve HPV vaccine coverage of children and teenagers. In a population-based sample in North Carolina, most (62%) parents of unvaccinated daughters intended to vaccinate them against HPV during the coming year [14]. However, on longitudinal follow-up, less than 40% of these parents actually did so, and barriers to care (i.e. believing that it would be difficult to find a provider who stocked the vaccine or who offered the vaccine at an affordable price) were associated with lower uptake [15]. If school vaccination programs could address these barriers, they might increase vaccine receipt among daughters of parents who intend to vaccinate but fail to follow through. Further, because schools offer the possibility of reaching low-income students [13] and students who are not otherwise accessing preventative care [16], they could reduce disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality by targeting areas and populations with high rates of the disease.

To address whether school-based HPV vaccination could remove barriers and provide an acceptable option for parents, we surveyed mothers who got or intended to get HPV vaccine for their daughters about their willingness to let their daughters receive HPV vaccine at school. We also assessed mothers’ potential concerns about school-based HPV vaccine provision.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

We used data from a nationally representative sample of mothers of adolescent females ages 11–14 who were members of an existing panel of U.S. households [17]. The panel was composed using list-assisted, random-digit dialing, supplemented by address-based sampling for homes with no landline, which provided a probability-based sample of U.S. households [17]. Panel members received free internet access and a small payment in exchange for completing multiple internet-based surveys each month. Households without pre-existing internet were provided a laptop computer and internet access. The Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina approved the study.

The survey company invited 1681 mothers to complete our cross-sectional, online survey. Among those mothers, 1170 opened the email invitation, and 1009 had a daughter ages 11–14, making them eligible to participate in the study. A total of 951 mothers of 11–14 year-old females completed the survey in December 2009 (response rate = 66%, calculated using the American Association for Public Opinion Research response rate formula 4 [18]). Participants were more likely than non-participants to have a college degree, but they did not differ on 6 other key sociodemographic characteristics available for non-participants. In order to understand mothers’ support for school-based HPV vaccination specifically, rather than support for HPV vaccination more generally, for this analysis we excluded mothers (n = 443) who did not intend to vaccinate daughters against HPV in the next year and thus included only mothers who had vaccinated or intended to vaccinate daughters in the coming year. We also excluded respondents who had missing data on willingness to get their daughters vaccinated at school (n = 7) or who indicated that daughters were homeschooled (n = 5), resulting in an analytic sample of 496 mothers.

2.2. Measures

The survey (available at www.unc.edu/~ntbrewer/hpv.htm) assessed willingness to vaccinate daughters at school with the question “If [daughter name]’s school offered HPV vaccine, how willing would you be to let her get it there?” We categorized mothers as willing to allow their daughters to get vaccinated at school if they responded they were “definitely” or “probably” willing and categorized them as unwilling if they responded they were “definitely not” or “probably not” willing. Mothers also indicated whether they had any of 6 specific concerns or no concerns about school vaccination.

Current HPV vaccination status had three categories. The “not initiated” group included daughters who had not received any HPV shots but whose mothers intended for them to be vaccinated in the next year. Daughters in the “initiated” group included those who previously received one shot, two shots, or an unknown number of shots. The “completed” vaccine group included those daughters who had received all 3 HPV vaccine shots.

Four survey items assessed HPV vaccine knowledge: HPV vaccine prevents most genital warts, prevents most cases of cervical cancer, is recommended for 11- or 12-year-old girls, and works best if girls get it before they start having sex. We created an index by calculating the proportion of correct answers for each respondent (possible range 0–1, with higher values indicating greater knowledge). Four items assessed mothers’ satisfaction with their daughters’ health care: the daughter’s health care is of good quality, the mother is getting needed information about daughter’s health or health care, the doctor spends enough time with daughter, and the doctor is a trusted source of advice. We averaged these items to create a satisfaction scale (possible range 1–5, with higher values indicating greater satisfaction (α = 0.85)). The survey also assessed demographic correlates including being politically conservative and born-again or evangelical Christian, as concerns about HPV vaccine have often come from these groups[15,19].

2.3. Data analyses

We examined bivariate correlates of willingness to have daughter receive HPV vaccine at school using logistic regression. All correlates identified as statistically significant (p < .05) in bivariate analyses were included in a multivariate model. We examined the percentage of mothers who endorsed each of the school vaccination concerns, comparing those who were willing to vaccinate at school to those who were not willing using chi-square tests. We also used chi-square tests to examine the association between each concern and vaccination status (i.e., mother intended to vaccinate daughter vs. daughter had received one more doses of HPV vaccine). We analyzed weighted data in Stata SE version 10.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX) applying sampling weights. Frequencies are unweighted and estimates (including proportions and odds ratios) are weighted. All analyses were two-tailed, using a critical α of .05.

3. Results

Most mothers were 40 years old or older (55%), non-Hispanic white (55%), married (76%), did not have a college degree (74%), lived in urban areas (85%), and reported a household income of less than $60,000 (55%; Table 1). Approximately one-third (34%) indicated they were born-again or evangelical Christian. Most daughters (93%) had health insurance. Twenty percent of mothers reported that their daughters had completed the 3-dose series of HPV vaccine shots, 31% that daughters had initiated but not completed the series (only 1 or 2 shots), and 48% that they intended to vaccinate daughters in the next year. Twelve mothers who said their daughters initiated the vaccine series but did not know how many doses they had received were included in the “initiated” group. Analyses do not change meaningfully when these 12 cases are omitted.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (n = 496).

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Daughter characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| 11 years | 117 | (26.9) |

| 12 years | 91 | (17.2) |

| 13 years | 132 | (25.0) |

| 14 years | 156 | (30.9) |

| Has health insurance | ||

| No | 19 | (6.8) |

| Yes | 477 | (93.2) |

| Has a regular healthcare provider | ||

| No | 15 | (3.3) |

| Yes | 481 | (96.8) |

| HPV vaccine 3 dose series | ||

| Not initiated | 224 | (48.4) |

| Initiateda | 153 | (31.4) |

| Completed | 119 | (20.3) |

| Mother characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| <40 years | 162 | (45.1) |

| 40–49 years | 270 | (47.0) |

| 50+ years | 64 | (8.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 365 | (54.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 47 | (17.3) |

| Hispanic or other | 84 | (28.1) |

| Education | ||

| No college degree | 272 | (74.0) |

| College degree or higher | 224 | (26.0) |

| Marital status | ||

| Other | 97 | (23.7) |

| Married | 399 | (76.3) |

| Political views | ||

| Somewhat or very conservative | 176 | (37.7) |

| Moderate | 201 | (44.1) |

| Somewhat or very liberal | 119 | (18.1) |

| Born-again or evangelical Christian | ||

| No | 351 | (65.6) |

| Yes | 145 | (34.4) |

| Satisfaction with daughter’s medical care, mean (SD)b | 4.23 | (0.74) |

| Ever talked with daughter about HPV vaccine | ||

| No | 105 | (26.1) |

| Yes | 391 | (73.9) |

| HPV vaccine knowledge, mean (SD)c | 0.52 | (0.31) |

| Household characteristics | ||

| Annual household income | ||

| <$60,000 | 180 | (55.2) |

| $60,000+ | 316 | (44.9) |

| Area of residenced | ||

| Rural | 61 | (15.1) |

| Urban | 435 | (84.9) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 85 | (16.3) |

| Midwest | 153 | (22.4) |

| South | 136 | (40.8) |

| West | 122 | (20.5) |

| Number of children in household | ||

| 1–2 | 337 | (62.3) |

| 3 or more | 159 | (37.7) |

Note: Table shows raw frequencies and weighted percentages. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. HPV = human papillomavirus; SD = standard deviation.

Includes 12 parents who said their daughter initiated the vaccine but did not know how many doses. Analyses do not change meaningfully when these 12 cases are omitted.

Mean score on health care satisfaction scale. Component items included mother’s satisfaction with daughter’s healthcare (range: 1 =very dissatisfied to 5=very satisfied) and mother’s beliefs (range: 1 =strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) that she is getting needed information about daughter’s health or health care, the doctor spends enough time with daughter, and the doctor is a trusted source of advice.

Proportion of correct responses on 4 HPV vaccine knowledge items (range: 0-1). Component items included knowledge that HPV vaccine: prevents most genital warts, prevents most cervical cancer, is recommended for 11- or 12-year-old girls, and works best if girls get it before they start having sex.

Rural defined as living outside of a metropolitan statistical area (Census Bureau Glossary http://factfinder.census.gov/home/en/epss/glossary_r.html).

Overall, 67% of mothers who intended to vaccinate their daughters or had vaccinated their daughters reported being willing to have their daughters receive HPV vaccine at school (Table 2). Multivariate correlates of willingness to vaccinate at school were daughter’s HPV vaccination status and region of residence. Mothers whose daughters had completed the 3-dose series were less accepting of school vaccination than mothers whose daughters had not initiated the vaccine series, (56% vs. 76%, OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.22, 0.97). Mothers whose daughters had not initiated the vaccine series did not differ in support from those who had initiated but not yet completed the series. Compared to mothers residing in the Northeast, willingness to have daughters vaccinated at school was higher among mothers in the Midwest (OR 2.56, 95% CI 1.20, 5.43) or West (OR 3.03, 95% CI 1.51, 6.12).

Table 2.

Correlates of willingness to have daughter receive HPV vaccine at school (n = 496).

| Willing to vaccinate at school |

Bivariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 322 | (66.8) | ||||

| Daughter characteristics | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| 11 years (Ref) | 79 | (74.2) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| 12 years | 64 | (74.6) | 1.02 | (0.40, 2.63) | 1.16 | (0.46, 2.93) |

| 13 years | 73 | (50.2) | 0.35 | (0.15, 0.80)* | 0.52 | (0.24, 1.12) |

| 14 years | 106 | (69.6) | 0.80 | (0.35,1.84) | 1.09 | (0.46, 2.59) |

| Has health insurance | ||||||

| No (Ref) | 14 | (82.7) | 1.00 | - | ||

| ;Yes | 308 | (65.7) | 0.40 | (0.11,1.45) | ||

| Has a regular healthcare provider | ||||||

| No (Ref) | 11 | (73.4) | 1.00 | - | ||

| Yes | 311 | (66.6) | 0.72 | (0.19, 2.77) | ||

| HPV vaccine 3 dose series | ||||||

| Not initiated (Ref) | 158 | (76.4) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Initiateda | 97 | (59.2) | 0.45 | (0.22, 0.91)* | 0.60 | (0.30, 1.23) |

| Completed | 67 | (55.8) | 0.39 | (0.19, 0.79)** | 0.46 | (0.22, 0.97)* |

| Mother characteristics | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| <40 years (Ref) | 102 | (68.3) | 1.00 | - | ||

| 40–49 years | 173 | (62.9) | 0.79 | (0.42,1.47) | ||

| 50+ years | 47 | (81.7) | 2.07 | (0.93, 4.59) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white (Ref) | 234 | (65.0) | 1.00 | - | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 30 | (64.8) | 0.99 | (0.40, 2.48) | ||

| Hispanic or other | 58 | (71.6) | 1.25 | (0.62, 3.00) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Some college or less (Ref) | 182 | (69.1) | 1.00 | - | ||

| Bachelors degree or more | 140 | (60.3) | 0.68 | (0.40, 1.16) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Other (Ref) | 72 | (75.3) | 1.00 | - | ||

| Married | 250 | (64.2) | 0.59 | (0.26,1.35) | ||

| Political views | ||||||

| Conservative (Ref) | 107 | (61.3) | 1.00 | - | ||

| Moderate | 134 | (68.8) | 1.39 | (0.70, 2.76) | ||

| Liberal | 81 | (73.6) | 1.76 | (0.86,3.61) | ||

| Born-again or evangelical Christian | ||||||

| No (Ref) | 240 | (65.7) | 1.00 | - | ||

| Yes | 82 | (69.0) | 1.16 | (0.63, 2.14) | ||

| Satisfaction with daughter’s medical care, mean (SD)b | 4.17 | (0.78) | 0.74 | (0.48,1.13) | ||

| Ever talked with daughter about HPV vaccine | ||||||

| No (Ref) | 75 | (78.3) | 1.00 | - | ||

| Yes | 247 | (62.8) | 0.47 | (0.22,1.01) | ||

| HPV vaccine knowledge, mean (SD)c | 0.48 | (0.32) | 0.33 | (0.12, 0.95)* | 0.49 | (0.17, 1.43) |

| Household characteristics | ||||||

| Annual household income | ||||||

| <$60,000 (Ref) | 123 | (71.3) | 1.00 | - | ||

| $60,000+ | 199 | (61.3) | 0.64 | (0.35,1.15) | ||

| Area of residence | ||||||

| Rural (Ref) | 43 | (69.7) | 1.00 | - | ||

| Urban | 279 | (66.3) | 0.86 | (0.33, 2.19) | ||

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast (Ref) | 47 | (47.3) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| South | 85 | (71.4) | 2.36 | (1.04, 5.36)* | 1.91 | (0.89, 4.10) |

| Midwest | 103 | (68.0) | 2.79 | (1.28, 6.05)* | 2.56 | (1.20, 5.43)* |

| West | 87 | (75.0) | 3.34 | (1.54, 7.23)" | 3.03 | (1.51,6.12)" |

| Number of children in household | ||||||

| 1–2 (Ref) | 223 | (69.1) | 1.00 | - | ||

| 3 or more | 99 | (63.0) | 0.76 | (0.41,1.43) | ||

Note: Table shows raw frequencies and weighted estimates. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. Multivariate model contains all correlates significant (p<.05) in bivariate models. HPV = human papillomavirus; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; Ref= reference category; SD = standard deviation.

Includes 12 parents who said their daughter initiated the vaccine but did not know how many doses. Analyses do not change meaningfully when these 12 cases are omitted.

Mean score on health care satisfaction scale. Component items included mother’s belief that: daughter’s health care is of good quality, she is getting needed information about daughter’s health or health care, the doctor spends enough time with daughter, and the doctor is a trusted source of advice.

Proportion of correct responses on 4 HPV vaccine knowledge items (range: 0–1).

p<.05.

p<.01.

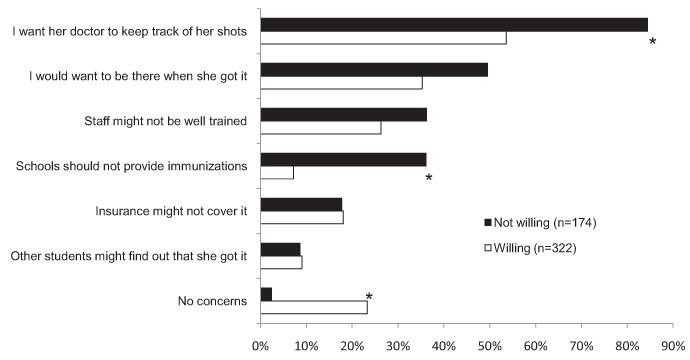

Mothers’ most common concern about in-school vaccination was that the daughter’s doctor should keep track of her shots and other health history (64%). When stratified by willingness to vaccinate at school (Fig. 1), more mothers who were unwilling were concerned about doctors’ keeping track of daughters’ health records than mothers who were willing (84% vs. 54%, p < .001). As one might expect, more mothers who were unwilling to vaccinate at school felt that schools should not provide vaccinations and fewer said that they had no concerns about in-school vaccination, when compared to mothers who approved of in-school HPV vaccination (each p < .001). Concerns about being present during vaccination (40%), staff training (30%), and insurance coverage (18%) were less commonly cited and did not differ by willingness. More mothers who intended to vaccinate daughters were concerned about being present during vaccination than those whose daughters had received one or more doses of HPV vaccine (47% vs. 33%, p < .05).

Fig. 1.

Mothers’ (n = 496) concerns about allowing their daughters to receive HPV vaccine at school, according to willingness to vaccinate at school. *p < .001.

4. Discussion

With less than half of eligible girls having initiated HPV vaccine [5], the U.S. should promote additional vaccine implementation strategies to increase uptake. School-based vaccination has been successful in generating broad HPV vaccination coverage in other countries [7-11], and our findings suggest that the majority of U.S. mothers who support HPV vaccination find school-based vaccination an acceptable option. Among mothers who had already gotten or intended to get HPV vaccine for their daughters, two-thirds were willing to have their daughters receive the vaccine at school.

Mothers whose daughters had already completed the 3-dose HPV vaccine series had somewhat less favorable attitudes toward HPV vaccination at school than mothers who had not initiated the vaccine series for their daughters but intended to do so. The former group might have indicated lower acceptability because they interpreted the question as referring to receipt of additional doses (>3) of the vaccine after the series had already been completed. Alternatively, mothers whose daughters had already completed the vaccination series may have done so precisely because of greater comfort with vaccine administration in a health care provider’s office. Thus, they may prefer this setting over a school.

Concerns about HPV vaccine provision in schools did differ between those who were willing and unwilling to vaccinate at school. The vast majority of mothers who were unwilling to have their daughters receive HPV vaccine at school were concerned about their daughters’ physicians keeping track of their health records, and this may be a difficult issue to address. Although many states have immunization information systems, also known as state vaccination registries, not all private providers participate in these systems, and the comprehensiveness of systems differs from state to state [20]. Moreover, schools do not always participate in these registries, and identifying students in the registries and updating their vaccination data requires time and effort from staff.

A substantial proportion of all mothers wanted to be there when their daughters were vaccinated, and more mothers who intended to vaccinate daughters endorsed this concern compared to mothers whose daughters had some or all shots. Allowing mothers to be present during in-school vaccination would allay some concern. However, as many mothers did not have this concern, requiring parental attendance for vaccination may be unduly burdensome and could reduce vaccine uptake. Being present for vaccination can also mean substantial lost time at jobs for working parents [21].

Some mothers were concerned about the level of staff training and insurance coverage for in-school vaccination. These concerns did not differ by willingness to vaccinate at school, suggesting that they are basic concerns that may not be related specifically to HPV vaccine. To make school-based vaccination more feasible, schools where staff have sufficient training to administer vaccines should reassure parents by describing that training. Insurance coverage for in-school vaccination may vary by insurance plan, but children eligible for the Vaccines for Children program should be able to receive many vaccines, including HPV vaccine, at no cost.

Initiating school-based HPV vaccination programs in the U.S. is likely to be challenging, as the nature and extent of health care offered at schools varies widely [22]. Even when community vaccinators are brought into schools to provide services or school-based programs are coordinated through health departments, barriers include obtaining vaccination records to see which vaccines are needed, billing private insurance, covering students who do not qualify for the federal Vaccines for Children program, and obtaining parental consent for vaccination [13]. Although schools with health centers will receive increased federal funding through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act [23], many of these barriers will remain and will be undoubtedly amplified for programs that will not receive additional funding through the new law.

Furthermore, past experience with school vaccination programs in the U.S. suggests that they tend to be most successful when they are implemented in response to acute outbreaks or to deliver vaccines mandated for school admissions [22], neither of which generally apply to HPV vaccine in the U.S. School-based programs to vaccinate against Hepatitis B in the 1990s were extremely successful, but these programs were by and large demonstration projects, intended to cover the gap until routine infant vaccine administration and school-entry laws ensured widespread coverage [24,25].

Finally, any school-based program must overcome challenges posed by competing priorities and limited resources in the nation’s schools. In response to these challenges, current recommendations for promoting adolescent vaccination in schools include: integrating vaccine information into existing health curricula; disseminating vaccine information to parents via existing channels, such as parent newsletters; working with school nurses and other school personnel to build support; and forming coalitions with community partners, such as school board representatives, health department staff, and pediatricians [22].

Requiring HPV vaccination for school entry could circumvent many of the problems described above and is another strategy with potential to dramatically increase vaccine coverage; however, policymakers in the U.S. have adopted this approach only rarely to date, as such requirements have been controversial. Opponents have argued that HPV school immunization requirements infringe on parental autonomy and have decried the vaccine as unnecessary, unsafe, or implicitly encouraging teenage sexual activity [26-28]. Between 2007 and 2010, 24 states and the District of Columbia proposed legislation requiring HPV vaccination for girls entering sixth grade, but the legislation failed or was withdrawn in a host of states, including Michigan, Ohio, Texas, California, and Maryland [29]. To date, Washington DC and Virginia are the only jurisdictions that have enacted requirements, but both allow parents to easily opt out of the requirement for any reason [29,30]. In the absence of school requirements in most states, voluntary school-based HPV vaccination remains a central strategy to explore, and understanding parental attitudes toward school-based HPV vaccination is an important first step.

Parental support will be crucial to implementing school-based provision of HPV vaccine. School policy decisions in the U.S., including whether to allow vaccination programs in schools, are typically made at the local level by school administrators, including principals and superintendants. Parents are key stakeholders in decisions about school health programs and can influence administrators’ judgments about controversial topics [22]. Understanding parental support for providing HPV vaccine in schools will be important for planning implementation of new policies. It is important to remember that our analytic sample did not include mothers who indicated that they would not vaccinate their daughters against HPV in the coming year. We chose this strategy in order to differentiate attitudes toward school-based HPV vaccination from attitudes toward HPV vaccination in any setting. However, excluding these mothers prevents us from fully characterizing parental support for school-based HPV vaccination policies.

Strengths of this study include the sizeable nationally representative sample and timeliness of the topic for informing new public health programs. However, unfamiliarity with school-based health care in general rather than to opposition to school-based HPV vaccination specifically may inform some parents’ responses, given that school-based health care is relatively uncommon in the U.S. As we did not assess whether daughters attended public or private schools or whether daughters had access to school-based clinics, we were not able to examine the impact of these variables on mothers’ willingness to let their daughters receive HPV vaccine at school.

5. Conclusions

School-based HPV vaccination programs in other countries have been successful in increasing vaccine coverage rates. Findings from this study suggest that many U.S. parents who support vaccination against HPV would be willing to vaccinate their adolescent daughters at school. However, parental acceptance is only one of many barriers to school-based vaccination, perhaps less important than structural barriers like identifying correct payers for billing or maintaining up-to-date vaccination records across multiple vaccine administration settings. With school policy controlled at the local level and the health care and health insurance systems fragmented, the initiation of a widespread school-based vaccination program in the U.S. is not on the immediate horizon. In the mean-time, more research is needed to understand and address parental concerns about the administration of HPV vaccine in schools and to identify steps to address structural barriers.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This research was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Cancer Society (MSRG-06-259-01-CPPB), and the Cancer Control Education Program at UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (R25 CA57726). Members of the CDC were involved in conducting the study and in preparing and submitting this article. None of the other funding sources had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Noel Brewer has received grants from Merck and GlaxoSmithKline. Paul Reiter has received a grant from Merck. These funds were not used to support this research study.

References

- [1].Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, Keys J, Franceschi S, Winer R, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(3):621–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].SEER cancer statistics review [homepage on the Internet] National Cancer Institute; Bethesda MD: 1975-2007. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/ [Google Scholar]

- [3].Newmann SJ, Garner EO. Social inequities along the cervical cancer continuum: a structured review. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16(1):63–70. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1290-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years – United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(32):1018–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Watson M, Shaw D, Molchanoff L, McInnes C. Challenges, lessons learned and results following the implementation of a human papilloma virus school vaccination program in South Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2009;33(4):365–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Reeve C, De La Rue S, Pashen D, Culpan M, Cheffins T. School-based vaccinations delivered by general practice in rural North Queensland: an evaluation of a new human papilloma virus vaccination program. Commun Dis Intell. 2008;32(1):94–8. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2008.32.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brotherton JM, Deeks SL, Campbell-Lloyd S, Misrachi A, Passaris I, Peterson K, et al. Interim estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage in the school-based program in Australia. Commun Dis Intell. 2008;32(4):457–61. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2008.32.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ogilvie G, Anderson M, Marra F, McNeil S, Pielak K, Dawar M, et al. A population-based evaluation of a publicly funded, school-based HPV vaccine program in British Columbia, Canada: parental factors associated with HPV vaccine receipt. PLoS Med. 2010;7(5):e1000270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stretch R. Implementing a school-based HPV vaccination programme. Nurs Times. 2008;104(48):30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tegnell A, Dillner J, Andrae B. Introduction of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Sweden. Euro Surveill. 2009;14(6):19119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Brener ND, Wheeler L, Wolfe LC, Vernon-Smiley M, Caldart-Olson L. Health services: results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007;77(8):464–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Daley MF, Curtis CR, Pyrzanowski J, Barrow J, Benton K, Abrams L, et al. Adolescent immunization delivery in school-based health centers: a national survey. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(5):445–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT, Sternberg MR, Smith JS, Ziarnowski K, Liddon N, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation in an area with elevated rates of cervical cancer. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(5):430–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, Reiter PL, McRee AL, Liddon N, Markowitz L, et al. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in a high-risk geographic area. Sex Transm Dis. 2010 Sep; doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f12dbf. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yu SM, Bellamy HA, Kogan MD, Dunbar JL, Schwalberg RH, Schuster MA. Factors that influence receipt of recommended preventive pediatric health and dental care. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6):e73. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].KnowledgePanel®: processes & procedures contributing to sample representativeness & tests for self-selection bias. 2010 Mar; Available from: http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/ganp/docs/KnowledgePanelR-Statistical-Methods-Note.pdf.

- [18].American Association for Public Opinion Research . Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. AAPOR; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Constantine NA, Jerman P. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination among Californian parents of daughters: a representative statewide analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(2):108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hinman AR, Urquhart GA, Strikas RA. National Vaccine Advisory Committee Immunization information systems: National Vaccine Advisory Committee progress report, 2007. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(6):553–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000296129.31896.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Deuson RR, Hoekstra EJ, Sedjo R, Bakker G, Melinkovich P, Daeke D, et al. The Denver school-based adolescent hepatitis B vaccination program: a cost analysis with risk simulation. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(11):1722–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.11.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lindley MC, Boyer-Chu L, Fishbein DB, Kolasa M, Middleman AB, Wilson T, et al. The role of schools in strengthening delivery of new adolescent vaccinations. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl. 1):S46–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1115F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Public Law. 2010:111–148. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hollinger FB. Comprehensive control (or elimination) of hepatitis B virus transmission in the United States. Gut. 1996;38(Suppl. 2):S24–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.suppl_2.s24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hepatitis B vaccination of adolescents – California, Louisiana, and Oregon, 1992-1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43(33):605–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stewart A. Childhood vaccine and school entry laws: the case of HPV vaccine. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(6):801–3. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Charo RA. Politics, parents, and prophylaxis – mandating HPV vaccination in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1905–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Colgrove J. The ethics and politics of compulsory HPV vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2389–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].HPV vaccine: state legislation and statutes [homepage on the Internet] 2010 [updated April]. Available from: http://www.ncsl.org/default.aspx?tabid=14381.

- [30].Gostin LO, DeAngelis CD. Mandatory HPV vaccination: public health vs private wealth. JAMA. 2007;297(17):1921–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.17.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]