Abstract

In this case study and review, we present a case of a primary small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNC) of the male breast. Primary SCNC of the breast is a rare tumor with less than 30 cases reported in the literature. Most cases are found in women. Another exceptional point is that human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (Her-2) immunoreactivity was positive in our recent case, which differed to previous reports detailing SCNC in women. We have no evidence to demonstrate the differences between treatment and prognoses for males and females, because we do not have sufficient cases to undertake an evidence-based investigation. We provide this rare case history; review the literature on SCNC of the breast; and discuss detailed information regarding epidemiology, histogenesis, clinical and histologic diagnosis criteria, surgical and adjuvant treatment, and prognosis.

Keywords: small-cell carcinoma, SMCC, neuroendocrine, male breast cancer, SCNC neoplasm

Case report

A 79-year-old man was referred to the Second Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University with a self-detected mass in the right breast. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one reported case of this on a male, which dates back to 1984.1 Physical examination revealed an irregular mass in the lateral upper quadrant of the right breast measuring approximately 2×1 cm, but no mass was detectable in either axilla. There were no other associated symptoms bar a slight uncomfortable feeling on the right chest wall. Breast ultrasound showed an ill-defined mass (2.1×1.3 cm) with non-uniform internal echo. No other abnormalities were found through general examinations including computed tomography scan of head and neck, and ultrasound scan of chest and abdomen. The patient had a prior smoking history of 50 packs a month.

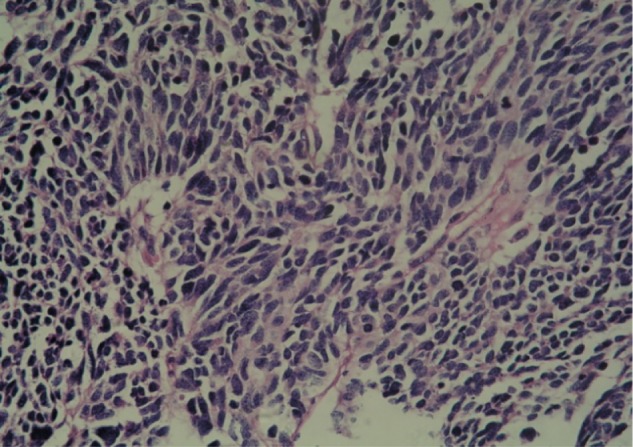

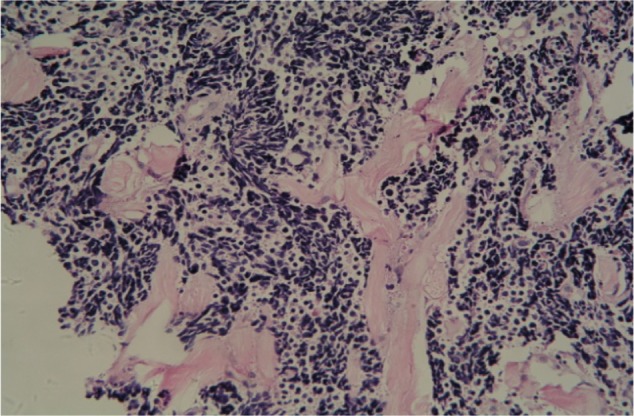

A preoperative biopsy of the mass was not considered. However, this parameter did not change management of the mass, because there was no evidence that the patient required neoadjuvant therapy, even though he was diagnosed with small-cell carcinoma (SMCC) of the breast before surgery. Considering the malignancy of the mass, we conducted a simple radical mastectomy and level I lymphadenectomy, without sentinel lymph node identification. The resection specimen consisted of a round fragment of skin and palpable mass, and underlying fatty soft tissue measuring 15 cm in total. Sectioning showed a firm white mass beneath the skin measuring approximately 2×1 cm. Two of nine lymph nodes were metastatic. The tumor had invaded striated muscle. Histopathological examination demonstrated that the tumor was predominantly composed of small cells with hyperchromatic nuclei demonstrating chromatin diffusion and resembling “oat cell” carcinoma of lung. The tumor was densely cellular, with cells showing thin cytoplasm, and consisted of rounded solid nests of cells. The nucleolus was inconspicuous, and cytokinesis was general. Cancer cells were oval shaped, and had finely granular nuclear chromatin with uniform and vesicular nuclei and relatively eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Histology of the breast tumor tissue.

Note: Tumor predominantly composed of small cells with hyperchromatic nuclei demonstrating chromatin diffusion and resembling “oat cell” carcinoma of the lung.

Figure 2.

Tumor nucleolus showing cytokinesis.

Notes: The tumor tissue nucleolus was inconspicuous and cytokinesis was general. Cancer cells were oval shaped and had finely granular nuclear chromatin with uniform and vesicular nuclei and relatively eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Due to these features, immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses with neuroendocrine markers were performed. Hematoxylin and eosin, and immunohistochemical staining were performed, and results are listed in Table 1. Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (Her-2) was expressed in this case. This is an exceptional case, because Her-2 immunoreactivity has not been reported in primary SCNC of the breast before. Staining for chromogranin A was also positive. These results were consistent with the small-cell type of breast neuroendocrine tumors (World Health Organization [WHO] 2003).2

Table 1.

Stain intensity and evidence of SCNC of the breast markers in tissue samples

| Intensity | |

|---|---|

| Stain | |

| Syp | ++ |

| CD56 | + |

| Breast markers | |

| ER | − |

| PR | + |

| Her-2 | + |

Notes: Thin slices of tumor tissue for all cases received in our histopathology unit were fixed in 4% formaldehyde solution (pH 7.0) for periods not exceeding 24 hours. The tissues were processed routinely for paraffin embedding, and 4 μm-thick sections were cut and placed on glass slides coated with (3-Aminopropyl) triethoxysilane for immunohistochemistry. Tissue samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to determine the histological type and tumor grade.

Abbreviations: SMCC, small-cell carcinoma; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; Syp, synaptophysin; CD56, cluster of differentiation 56.

Due to the patient’s fear of the adverse effects of the chemotherapy, the patient initially refused any further treatment postoperatively until 20 months had passed when the metastatic lymph node was found on his neck. He was then treated with two cycles of irinotecan combined with carboplatin, followed by docetaxel for one cycle because of his intolerance to initial chemotherapy, which caused myelosuppression. Unfortunately, he still developed pulmonary, bone, and hepatic metastases and lived for only 27 months after the operation.

Discussion

In 2003,2 the WHO recognized this type of cancer, and defined mammary neuroendocrine carcinoma as the expression of neuroendocrine markers in more than 50% of tumor cells. In 2012,3 WHO revised the category and divided neuroendocrine carcinomas into three subtypes: 1) neuroendocrine tumor, well-differentiated; 2) neuroendocrine carcinoma, poorly differentiated/small cell carcinoma; and 3) invasive breast carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation. The true incidence of primary neuroendocrine cancer of the breast (NECB) is estimated to range between 0.3% and 0.5% according to the reported reviews of 1,368 and 1,845 breast cancer specimens, respectively.4,5 Therefore, SCNC is extremely rare and has been reported sporadically. Eighty percent of diagnosed cases are found in white women.6 SCNC most commonly arises in the lung, although it may occasionally arise at other sites, such as the breast. Unlike the SCNC in the lung which is more common in male patients, the incidence of SCNC of the breast is more common in females. Additionally, the average age for developing this subtype of cancer is higher in breast than in lung patients, ranging mainly from 60 to 70 years of age.7

Few differences in clinical presentation and imaging features have been confirmed between primary SCNC of the breast and common types of invasive carcinoma, although in some cases the breast lump is described as rapidly growing.8 In this case history, the histological and immunohistochemical investigations occupy an important place in particular. The prognoses for SCNC of the breast are not all the same, because SCNC is mainly defined by histological grade. Stages on average are more advanced than the usual breast carcinomas, since more than 50% of patients have lymph node metastases. Therefore, SCNC has a poor prognosis, whereas other well-differentiated carcinomas with lower proliferative activity could even be considered as benign tumors, because patients can live for more than 13 years according to follow-up.9

We have no evidence that there are differences between male and female patients living with SCNC in either therapeutic regimens or prognosis, and we cannot therefore infer the survival limit. Previous studies revealed that this type of tumor shows prominent vascular invasion and frequent lymph node metastasis.10 However, due to the rarity of the tumor, the published studies are not randomized, nor do they have a large number of patients.

What is needed primarily is that the diagnosis should be made early to prevent diagnostic mistakes. Neuroendocrine (NE) expression in IHC through NE markers represents the gold standard for diagnosing primary SCNC; chromogranin A, chromogranin B, and synaptophysin are considered the most sensitive and specific NE markers for this condition.11 The expression of NE markers is not consistent in the very rare SCNC of the breast subtype, however.8,12 More than 80% to 90% of SCNC express progesterone receptor (PR) and/or estrogen receptor (ER),13 with only 50% to 67% of SCNC subtypes expressing ER and/or PR; one third of SCNCs can be negative for both receptors.14 In SCNC, morphological behavior alone can be relied upon to confirm the diagnosis. Her-2 expression is nonexistent6 or very rarely present in SCNC.15 The average age at diagnosis of primary SCNC is usually 10 years later than the more common types of breast cancer.16 The diagnosis of primary SCNC must meet the following criteria: 1) non-mammary sites must be excluded clinically; and/or 2) in situ components must be demonstrated histologically.

One study indicated that SCNC patients have an unoptimistic prognosis, with most dying within 9 to 15 months after diagnosis despite surgical treatment, adjuvant radiation, and chemotherapy,17 while Shin et al8 indicated the prognosis is mainly dependent on the stage of the disease, and that the earlier notion of SCNC having a poor prognosis may not be correct. Debates around this issue are still without a final conclusion. Since 50% of the regional lymph nodes are often involved at the time of diagnosis, we are inclined to think that this subtype is more serious than more common breast cancers, but that prognosis may not be as poor as for SCNC of the lung. Despite no current line of management being agreed upon, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy should be carried out, because it is conducive to decrease tumor size. The roles of chemotherapy drugs etoposide and cisplatin have also been proved in the adjuvant scheme for treating SCNC of the breast.18 When this regimen was used in the neoadjuvant setting, the size of this SCNC subtype was decreased.

Before the tumor is metastatic, a modified radical mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection, followed by adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy according to the staging paradigm, appears to represent the best way to treat this tumor.19–21 Since SCNC usually stains positive for ER and/or PR, hormonal therapy has been attempted in the adjuvant setting to treat this tumor.22 The efficacy of such an approach is currently unknown. Neither the single adjuvant therapy approach nor combination of two or three methods appears to reach statistical significance in terms of improving overall survival.23

Conclusion

SCNC is a rare neoplasm. No conclusion has been drawn regarding current lines of management, and surgery is still the main treatment. Since it is a rare neoplasm, clinical trials comparing treatment options for SCNC of the breast are needed to define the optimal treatment.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jundt G, Schulz A, Heitz PU, Osborn M. Small-cell neuroendocrine (oat cell) carcinoma of the male breast. Immunocytochemical and ultrastructural investigations. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1984;404(2):213–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00704065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis P, Schnitt SJ, Sastre-Garau X. Invasive breast carcinoma. In: Tavassoli FA, Deyilee P, editors. Tumors of the Breast and Female Genital Organ: Pathology and Genetics. Lyon: France, IARC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakhani S, Ellis I, Schnitt S, Tan P, van de Vijver MJ, editors. WHO Classif Tumours Breast. IARC Press; Lyon: 2012. pp. 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.López-Bonet E, Alonso-Ruano M, Barraza G, Vazquez-Martin A, Bernadó L, Menendez JA. Solid neuroendocrine breast carcinomas: incidence, clinico-pathological features and immunohistochemical profiling. Oncol Rep. 2008;20(6):1369–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Günhan-Bilgen I, Zekioglu O, Ustün EE, Memis A, Erhan Y. Neuroendocrine differentiated breast carcinoma: imaging features correlated with clinical and histopathological findings. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(4):788–793. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1567-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei B, Ding T, Xing Y, et al. Invasive neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: a distinctive subtype of aggressive mammary carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116(19):4463–4473. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adegbola T, Connolly CE, Mortimer G. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: a report of three cases and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(7):775–778. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.020792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin SJ, DeLellis RA, Ying L, Rosen PP. Small-cell carcinoma of the breast: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of nine patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(9):1231–1238. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sapino A, Papotti M, Righi L, Cassoni P, Chiusa L, Bussolati G. Clinical significance of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:S115–S117. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_2.s115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sridhar P, Matey P, Aluwihare N. Primary carcinoma of breast with small-cell differentiation. Breast. 2004;13(2):149–151. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moriya T, Kanomata N, Kozuka Y, et al. Usefulness of immunohistochemistry for differential diagnosis between benign and malignant breast lesions. Breast Cancer. 2009;16(3):173–178. doi: 10.1007/s12282-009-0127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adegbola T, Connolly CE, Mortimer G. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: a report of three cases and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(7):775–778. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.020792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alkaied H, Harris K, Azab B, Dai Q. Primary neuroendocrine breast cancer, how much do we know so far? Med Oncol. 2012;29(4):2613–2618. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0222-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alkaied H, Harris K, Brenner A, Awasum A, Varma S. Does hormonal therapy have a therapeutic role in metastatic primary small-cell neuroendocrine breast carcinoma? Case report and literature review. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12(3):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zekioglu O, Erhan Y, Ciris M, Bayramoglu H. Neuroendocrine differentiated carcinomas of the breast: a distinct entity. Breast. 2003;12(4):251–257. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9776(03)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Upalakalin JN, Collins LC, Tawa N, Parangi S. Carcinoid tumors in the breast. Am J Surg. 2006;191(6):799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papotti M, Gherardi G, Eusebi V, Pagani A, Bussolati G. Primary oat cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the breast. Report of four cases. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1992;420(1):103–108. doi: 10.1007/BF01605991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samli B, Celik S, Evrensal T, et al. Primary neuroendocrine small cell-carcinoma of the breast. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:296–298. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0296-PNSCCT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christie M, Chin-Lenn L, Watts MM, Tsui AE, Buchanan MR. Primary small-cell carcinoma of the breast with TTF-1 and neuroendocrine marker expressing carcinoma in situ. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3(6):629–633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dardick L, Comer TP, O’Neill EJ, Bormanis P, Saxena NC, Weinstein EC. Metastatic neoplasm presenting as primary cancer of the breast: case reports. Mil Med. 1984;149(7):411–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian Z, Wei B, Tang F, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor grading and staging in mammary carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation. Hum Pathol. 2011;42(8):1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francois A, Chatikhine VA, Chevallier B, et al. Neuroendocrine primary small-cell carcinoma of the breast. Report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1995;18(2):133–138. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199504000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourhaleb Z, Uri N, Haddad H, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma with large cells of the breast: case report and review of the literature. Cancer Radiother. 2009;13(8):775–777. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]