Abstract

PURPOSE

Interventions tailored to sociopsychological factors associated with health behaviors have promise for reducing colorectal cancer screening disparities, but limited research has assessed their impact in multiethnic populations. We examined whether an interactive multimedia computer program (IMCP) tailored to expanded health belief model sociopsychological factors could promote colorectal cancer screening in a multiethnic sample.

METHODS

We undertook a randomized controlled trial, comparing an IMCP tailored to colorectal cancer screening self-efficacy, knowledge, barriers, readiness, test preference, and experiences with a nontailored informational program, both delivered before office visits. The primary outcome was record-documented colorectal cancer screening during a 12-month follow-up period. Secondary outcomes included postvisit sociopsychological factor status and discussion, as well as clinician recommendation of screening during office visits. We enrolled 1,164 patients stratified by ethnicity and language (49.3% non-Hispanic, 27.2% Hispanic/English, 23.4% Hispanic/Spanish) from 26 offices around 5 centers (Sacramento, California; Rochester and the Bronx, New York; Denver, Colorado; and San Antonio, Texas).

RESULTS

Adjusting for ethnicity/language, study center, and the previsit value of the dependent variable, compared with control patients, the IMCP led to significantly greater colorectal cancer screening knowledge, self-efficacy, readiness, test preference specificity, discussion, and recommendation. During the followup period, 132 (23%) IMCP and 123 (22%) control patients received screening (adjusted difference = 0.5 percentage points, 95% CI −4.3 to 5.3). IMCP effects did not differ significantly by ethnicity/language.

CONCLUSIONS

Sociopsychological factor tailoring was no more effective than nontailored information in encouraging colorectal cancer screening in a multiethnic sample, despite enhancing sociopsychological factors and visit behaviors associated with screening. The utility of sociopsychological tailoring in addressing screening disparities remains uncertain.

Keywords: colorectal neoplasms, computer-assisted instruction, early detection of cancer, expanded health belief model, health behavior, health care disparities, health education, health promotion, Hispanic Americans, outcome and process assessment (health care), patient acceptance of health care, randomized controlled trial, software

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer screening is underutilized.1,2 Screening rates are particularly low among Hispanic persons, reflecting language and socioeconomic barriers.1,3 Approaches to motivate more individuals to undergo colorectal cancer screening and lessen ethnic screening disparities are needed.

Interventions tailored to sociopsychological factors that may influence behavior, such as self-efficacy, stage of readiness, barriers, and others,4 show promise.5 Such interventions use responses elicited from individuals to match the content and amount of information to individual needs and sociopsychological factors, with the proximate goal of enhancing the factors.6–8 Tailoring of information increases its perceived relevance, promotes deeper cognitive processing, and improves recall.9 Further, in randomized controlled trials tailored interventions are more effective than nontailored interventions in enhancing sociopsychological factors across sociodemographic groups.10–22

Whether enhancement of sociopsychological factors influences health behaviors is uncertain.12,13,19,22–32 Among trials comparing patients receiving sociopsychologically tailored colorectal cancer screening interventions with active control,15,19,20,22,25–30,33 only some found superior effects of tailoring19,25,28,29,34; in all but 1 trial34 screening was self-reported,19,25,28,29 suggesting possible response bias. There is a need to examine further whether objectively measured colorectal cancer screening improves in response to sociopsychological tailoring.

Such interventions could also reduce ethnic disparities in health behaviors.8 One randomized controlled trial included sociopsychological tailoring in a multifaceted study of colorectal cancer screening in Hispanic and Asian-American racial/ethnic groups.25 That study found increased screening in both racial/ethnic groups, but it did not compare effects between these groups, and screening was self-reported. The multifaceted nature of the study precluded determination of tailoring effects specifically.

In a multicenter randomized controlled trial, we compared the effects of 2 patient-focused colorectal cancer screening interventions delivered before office visits. The first was an interactive multimedia computer program (IMCP), tailored to expanded health belief model (EHBM) factors associated with screening: knowledge, self-efficacy, barriers, readiness, test preference, and prior screening.4 Proximate aims were to enhance sociopsychological factors, motivating patients for screening and to encourage discussion of screening, and prompting clinicians to recommend screening.35 The second intervention was a nontailored program providing basic screening information. The primary outcome was colorectal cancer screening during a 12-month follow-up period, ascertained by record review. Randomization was stratified by ethnicity and language (non-Hispanic, Hispanic/English, or Hispanic/Spanish). We hypothesized that the tailored IMCP would be more effective than control in (1) favorably influencing the sociopsychological factors, (2) prompting discussion and clinician recommendation of screening, and (3) promoting screening. Further, given the relevance of EHBM factors across sociodemographic groups,25,36 we hypothesized IMCP effects would not differ by ethnicity or language.

METHODS

Study activities were conducted from February 1, 2010, to November 30, 2012. Institutional review board approval was obtained at all performance sites.

Study Setting, Recruitment, and Randomization

Patients aged 50 to 75 years and not up-to-date for colorectal cancer screening were recruited from primary care offices in Sacramento, California (10 offices, 9 in a university-affiliated network); the Bronx (1 federally qualified health center [FQHC]) and Rochester (2 FQHCs, 1 hospital-based practice), New York; San Antonio, Texas (2 FQHCs, 2 private practices); and Colorado (1 FQHC near Denver, 7 in a FQHC system 200 miles southwest of Denver). A sample size of 1,344 patients was targeted, approximately equally divided among 4 ethnicity/intervention subgroups (Hispanic/experimental, Hispanic/control, non-Hispanic/experimental, non-Hispanic/control). Anticipating 10% attrition, this sample size was estimated to yield 80% power to detect 10 percentage point differences in screening on pairwise between-subgroup comparisons.

At all but 1 site initial study eligibility was determined by medical record review. Patients were considered up-to-date for screening (and therefore ineligible) if 1 or more of the following was documented: fecal occult blood test (FOBT) within 1 year, flexible sigmoidoscopy within 5 years, or colonoscopy within 10 years.2,37 Persons meeting initial eligibility criteria were solicited for participation, primarily by telephone and secondarily by letters inviting a call to the recruitment line.

Additional eligibility required the ability to speak and read English or Spanish and adequate eyesight, hearing, and hand function to use a touchscreen computer. Eligible patients agreeing to participate were asked to arrive 1 hour before an appointment they had previously scheduled with their clinician so they could complete informed consent and the intervention. At the Bronx site, for feasibility reasons, recruitment personnel instead approached patients in the waiting area before their appointments, with study eligibility based on self-report.

Patients were given touchscreen notebook computers to use before and after their visit. Research assistants logged the patients into the study software and showed them how to navigate the program. After answering ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic) and preferred software language (English or Spanish) questions, patients were randomly assigned by the software to receive either the tailored IMCP or control program in their preferred language. Randomization was stratified by ethnicity and language and implemented in blocks of 10 within each stratum, using a random number generation program.38 Patients received a $20 gift card or cash after completing a postvisit questionnaire.

Study Interventions

We designed the study computer programs using standard software engineering principles.39 The design elements (eg, architecture, operating systems, usability features) have been described elsewhere.40

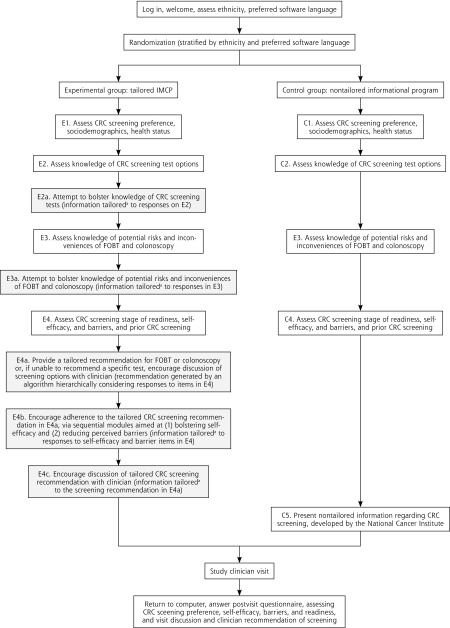

For patients receiving the experimental tailored IMCP, the computer algorithm for presenting tailored messages, including a specific colorectal cancer screening test recommendation based on EHBM measure responses, was developed using a previously described approach.41 The IMCP used sequential tailoring. An initial module assessed and then provided tailored information to increase knowledge of colorectal cancer screening tests (Figure 1, boxes E2 and E2a). The next module assessed and provided tailored information to increase knowledge of screening harms and inconveniences (Figure 1, boxes E3 and E3a). The final module assessed self-efficacy, barriers, readiness, test preference, and screening history (Figure 1, box E4), and then provided tailored information to enhance self-efficacy, barriers, and readiness (Figure 1, boxes E4a, E4b, and E4c). The approach of addressing knowledge gaps before trying to influence other EHBM factors was grounded in research regarding the promotion of informed decisions.42 Previsit EHBM measures were administered sequentially so that responses to each would still be fresh in patients’ minds when they viewed information tailored to the responses. Consistent with adult learning and behavioral theory, the IMCP allowed patients to decide how much information to view.6,43–45 The texts for the English and Spanish IMCP versions (average Flesch-Kincaid reading grade level 7.4) were developed by a previously described process.40,46 Examples of tailored IMCP content are available from the authors.

Figure 1.

Sequence and content of tailored IMCP and nontailored control interventions for colorectal screening.

CRC = colorectal cancer; FOBT = fecal occult blood test; IMCP = interactive multimedia computer program.

Note: shaded boxes indicate keying individually tailored modules of experimental IMCP.

aBasic structure of tailoring in each module: (1) give all users brief feedback tailored to their responses to relevant questions; (2) offer the option to view more-detailed information.

For the nontailored control program, after first completing all previsit study measures, control participants viewed nontailored colorectal cancer screening information, developed by the National Cancer Institute, in their preferred language (English or Spanish) (Figure 1, boxes C1 through C4, and C5, respectively).47,48

Measures

EHBM sociopsychological factors were measured pre- and postvisit. As noted previously, the timing of previsit measures differed somewhat between the study intervention groups (Figure 1). Preference for a colorectal cancer screening test was assessed with a single, newly developed item (response options: do not want screening, prefer FOBT, prefer colonoscopy, prefer another test, or want screening but no specific test preferred).10 Knowledge of screening test options was measured with a 3-item scale, with true (1 point) vs false/don’t know (0 points) responses (scores ranged from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater knowledge).10 Knowledge of screening risks and inconveniences (scores ranged from 0 to 6) was measured with a 6-item scale, using true (1 point) vs false/don’t know (0 points) responses.10 Both screening knowledge scales were modeled on previously validated scales for assessing patient knowledge of health issues.49

Colorectal cancer screening self-efficacy was measured using a 6-item scale; 3 items had been validated,50 and 3 were modeled on previously validated items.51 Barriers to FOBT and colonoscopy were measured with validated 9- and 10-item scales, respectively.52 In the self-efficacy and barriers scales, respondents indicated their degree of agreement or disagreement with statements (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Item responses were averaged to yield total scores (range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy or fewer barriers). FOBTs and colonoscopy stage of readiness (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation) were measured using modifications of a validated item.53 Prior FOBT and colonoscopy testing each were assessed with newly developed items (received vs not received/unsure).

Participants were asked whether screening was discussed during the visit and whether the clinician recommended screening (yes vs no/don’t recall).

Colorectal cancer screening (FOBT, flexible sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy) during 12 months of follow-up was ascertained by review of electronic and paper medical records. Data collection personnel were not alerted to participants’ study group.

In addition to ethnicity and language (both assessed before initial randomization), several other participant characteristics were assessed at baseline to verify that the intervention groups were well matched on characteristics that could influence screening. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, race (white, black, or other), income (less than $10,000, $10,000 to less than $15,000, $15,000 to less than $25,000, $25,000 to less than $50,000, or greater than $50,000), and education (less than high school, some high school, high school graduate, some college, or college graduate). Self-reported health literacy was assessed using a single item (scored from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating worse literacy).54 Health status was measured with the SF-12 Health Survey mental and physical component summaries (scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health).55 A single item assessed length of the clinician-patient relationship (less than 1 year, 1 to 2 years, 3 to 5 years, more than 5 years, or unsure).

Satisfaction with the intervention was assessed using a 5-item scale (scored from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction). Study software use time in minutes was extracted from program logs.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp). Descriptive comparisons used χ2 tests (categorical variables) and t tests (continuous variables). In examining the effects of the key predictor (experimental vs control intervention) on postvisit status of sociopsychological factors and visit behaviors (the dependent variables), we used logistic regression for screening preference (preference for a specific test [FOBT or colonoscopy] vs no specific test preference), discussion of screening (vs no discussion), and clinician recommendation for screening (vs no recommendation). We used ordinal logistic regression to examine intervention effects on stage of readiness (most favorable stage from FOBT and colonoscopy readiness items [precontemplation, contemplation, or preparation]), whereas we used linear regression for screening knowledge (test options and risks/inconveniences scores combined), self-efficacy, and barriers. We analyzed the association of study intervention condition with screening with logistic regression (received FOBT and/or colonoscopy by 12 months or not) and Cox proportional hazards models (time to screening, censoring at 12 months). All of the above analyses were adjusted for study recruitment center and ethnicity/language strata (non-Hispanic, Hispanic/English, and Hispanic/Spanish). The sociopsychological factor models were additionally adjusted for the previsit value of the dependent variable.

To explore whether intervention effects varied by ethnicity/preferred language, further models added experimental intervention*ethnicity/preferred language interaction terms. Additional models stratified by ethnicity/preferred language were also fit.

RESULTS

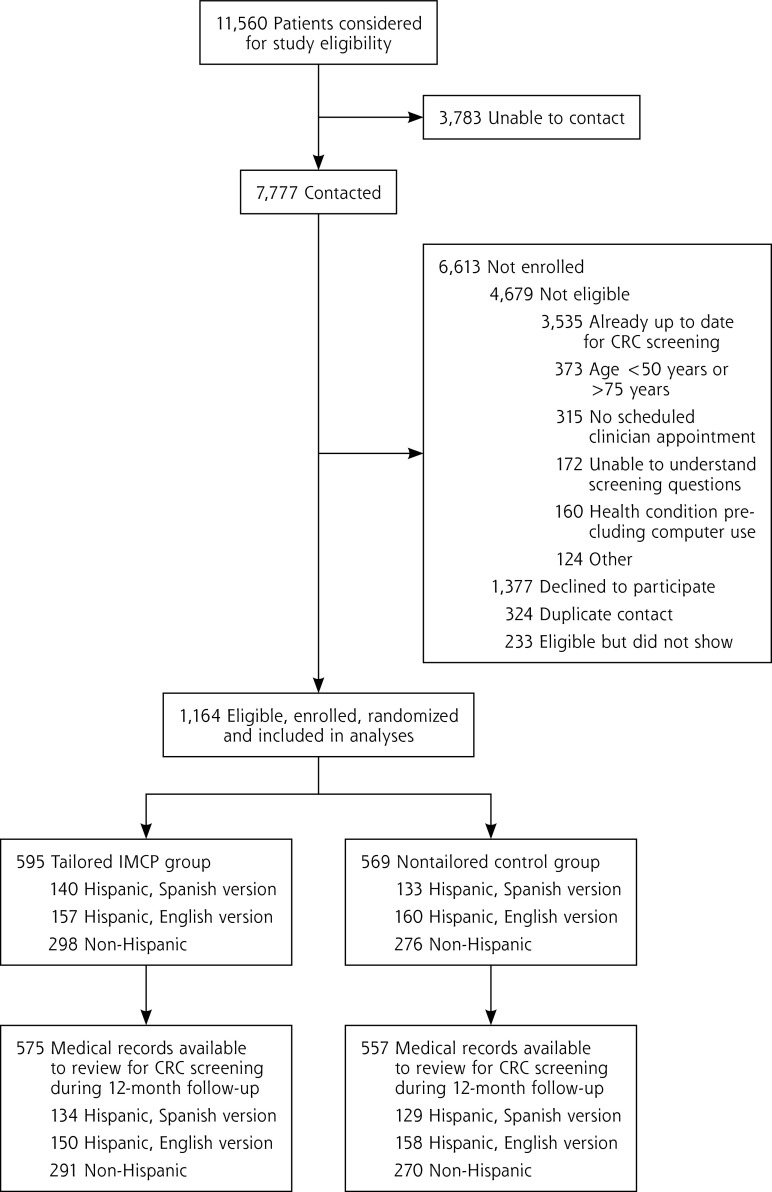

Figure 2 shows the flow of participants through the study. We randomized 1,164 patients (49.3% non-Hispanic, 27.2% Hispanic/English, 23.4% Hispanic/Spanish). There were no significant differences between study groups on previsit patient characteristics or intervention use time or satisfaction (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Flow of participants through the trial.

CRC = colorectal cancer; IMCP = interactive multimedia computer program.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants by Study Group

| Characteristics | Study Intervention Groupa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Control N = 569 |

Tailored IMCP N = 595 |

|

| Patient enrollment by performance site, % | ||

| Rochester, New York | 20.9 | 21.0 |

| Bronx, New York | 24.0 | 24.1 |

| Denver and Southwestern Colorado | 15.6 | 16.0 |

| San Antonio, Texas | 17.9 | 16.7 |

| Sacramento, California | 21.6 | 22.2 |

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 57.1 (6.2) | 57.0 (6.1) |

| Female, % | 65.8 | 65.0 |

| Spanish language version of software, % | 23.5 | 23.4 |

| Ethnicity/race category, % | ||

| Hispanic (any race) | 51.5 | 49.7 |

| Non-Hispanic | ||

| White | 20.7 | 21.0 |

| Black | 23.0 | 24.9 |

| Other race | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| Country of birth, % | ||

| United States | 69.2 | 70.6 |

| Argentina | 9.5 | 7.6 |

| Dominican Republic | 7.7 | 9.6 |

| Mexico | 7.7 | 8.2 |

| Puerto Rico | 5.8 | 4.0 |

| Length of time living in United States, %b | ||

| <1 y | 4.0 | 6.9 |

| 1–5 y | 8.0 | 11.4 |

| 6–10 y | 8.6 | 9.7 |

| >10 y | 79.4 | 72.0 |

| Education level, % | ||

| <High school | 15.8 | 19.0 |

| Some high school | 21.5 | 18.1 |

| High school graduate | 25.1 | 23.8 |

| Some college | 18.5 | 20.9 |

| College graduate | 19.0 | 18.3 |

| Income level, % | ||

| <$10,000 | 33.2 | 35.0 |

| $10,000 to <$15,000 | 18.9 | 17.8 |

| $15,000 to <$25,000 | 17.8 | 14.7 |

| $25,000 to <$50,000 | 14.5 | 15.3 |

| >$50,000 | 15.6 | 17.2 |

| Self-rated health literacy (range 1–5), mean (SD)c | 2.0 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.3) |

| Health-related characteristics | ||

| Health status score (range 0–100), mean (SD)d | ||

| SF-12 physical component summary | 42.9 (11.1) | 42.1 (11.7) |

| SF-12 mental component summary | 45.4 (11.4) | 45.5 (11.3) |

| Duration of current primary care clinician relationship, % | ||

| <1 y | 26.3 | 24.6 |

| 1–2 y | 18.9 | 16.8 |

| 3–5 y | 15.6 | 19.9 |

| >5 y | 36.1 | 36.5 |

| Unsure | 3.0 | 2.2 |

| Intervention factors | ||

| Software use time, mean (SD), mine | 32.5 (22.2) | 33.1 (21.8) |

| Satisfaction with software score (range 1–5), mean (SD)f | 4.2 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.5) |

IMCP = interactive multimedia computer program.

P >.10 for all comparisons of characteristics between groups (χ2 test for categorical variables, t test for continuous variables).

Calculated using data from the 350 respondents (175 control, 175 tailored IMCP, 30% of overall sample) indicating a country of birth other than the United States.

Higher scores indicate lower self-assessed health literacy.

Higher scores indicate better health.

Based on available data from 550 control patients and 572 IMCP patients.

Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction.

Table 2 shows unadjusted sociopsychological factor status, visit behaviors, and colorectal cancer screening by study group. Previsit, tailored IMCP recipients had more favorable scores than control group participants for knowledge of screening harms and inconveniences, total screening knowledge, and self-efficacy. Postvisit, IMCP recipients again had more favorable scores than control group participants for these measures, as well as for knowledge of test options and specific test preference. Visit discussion and clinician recommendation of screening (but not screening during follow-up) were more likely in the tailored IMCP group.

Table 2.

Unadjusted Expanded Health Belief Model Sociopsychological Factor Status, Patient and Provider Visit Behaviors, and Colorectal Cancer Screening by Study Group

| Characteristics (N = 1,164) | Intervention Group

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 569) |

Tailored IMCP (N = 595) |

|

| EHBM sociopsychological factors | ||

| Specific test preference, % | ||

| Previsit | 62.6 | 64.5 |

| Postvisita | 76.3 | 83.2 |

| Screening knowledge score, mean (SD) | ||

| Test options (score range 0–3)b | ||

| Previsit | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.8) |

| Postvisitc | 1.9 (0.8) | 2.2 (0.8) |

| Harms/inconveniences (score range 0–6)b,d | ||

| Previsitc | 3.7 (2.1) | 4.3 (2.1) |

| Postvisitc | 4.1 (2.3) | 5.0 (2.4) |

| Total (score range 0–9)b,e | ||

| Previsitc | 5.3 (2.5) | 5.9 (2.5) |

| Postvisitc | 6.0 (2.7) | 7.2 (2.8) |

| Self-efficacy score (score range 1–5), mean (SD)d,f | ||

| Previsitc | 3.8 (0.7) | 4.1 (0.7) |

| Postvisita | 3.9 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.6) |

| Barriers score (score range 1–5), mean (SD)d,g | ||

| FOBT | ||

| Previsit | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.8) |

| Postvisit | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.8) |

| Colonoscopy | ||

| Previsit | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.6) |

| Postvisit | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.7) |

| Stage of readiness, %d | ||

| Precontemplation | ||

| Previsit | 11.1 | 4.9 |

| Postvisit | 7.4 | 6.2 |

| Contemplation | ||

| Previsit | 63.0 | 62.0 |

| Postvisit | 59.5 | 54.5 |

| Preparation | ||

| Previsit | 25.9 | 33.0 |

| Postvisit | 33.0 | 39.4 |

| Self-reported prior CRC screening, %d | ||

| FOBT | 26.5 | 26.9 |

| Colonoscopy | 13.2 | 15.9 |

| Patient-reported visit behaviors, % | ||

| CRC screening discussed | 34.8 | 41.2 |

| Clinician recommended CRC screening | 50.2 | 59.0 |

| CRC screening, No. (%)h | 123 (22.1) | 132 (23.0) |

CRC = colorectal cancer; IMCP = interactive multimedia computer program; EHBM = expanded health belief model; FOBT = fecal occult blood testing.

P <.01.

Higher scores indicate greater knowledge.

P <.001 for difference in scores between intervention groups (c2 test for categorical variables, t test for continuous variables).

In the tailored IMCP group, these questions were answered after participants had viewed some information tailored to their knowledge of colorectal cancer screening options (see Methods and Figure 1 for details).

Total knowledge score is sum of scores for knowledge of screening test options and knowledge of screening harms and inconveniences scales.

Higher scores indicate higher self-efficacy.

Higher scores indicate fewer barriers.

During 12 months of follow-up, based on review of medical records, available for 1,132 participants (575 IMCP patients, 557 controls).

Table 3 shows the adjusted effects of the tailored IMCP on EHBM factors and visit behaviors. Compared with the control group, IMCP exposure led participants to higher screening knowledge, self-efficacy, and stage of readiness, a greater likelihood of preferring a specific test option, as well as more reported discussion and clinician recommendation of screening. There were no significant IMCP effects on FOBT or colonoscopy barriers. There were no significant interactions between intervention and ethnicity/language in influencing outcomes (data not shown, available upon request). Among Hispanic persons, however, IMCP effects on EHBM factors were limited to greater knowledge, readiness, and specific test preference in the stratum preferring English. There were no significant IMCP effects on screening discussion or recommendation in the Hispanic strata.

Table 3.

Adjusted Effects of the Tailored Intervention (vs Control) on Postvisit Sociopsychological Factors, Visit Behaviors, and Colorectal Cancer Screening

| Outcome | Entire Sample PEa (95% CI) | Stratified by Ethnicity/Preferred Language

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic PEa (95% CI) | Hispanic/English PEa (95% CI) | Hispanic/Spanish PEa (95% CI) | ||

| EHBM sociopsychological factorsb | ||||

| Prefer specific test option, % | 6.8 (2.2 to 11.4)c | 5.8 (−0.9 to 12.4) | 11.1 (1.7 to 20.6)d | 4.3 (−3.8 to 12.5) |

| Screening knowledge (total)e | 1.15 (0.86 to 1.44)f | 1.46 (1.04 to 1.87)f | 1.28 (0.70 to 1.86)f | 0.39 (−0.18 to 0.95) |

| Screening self-efficacy | 0.10 (0.03 to 0.18)c | 0.11 (0.00 to 0.22)d | 0.11 (−0.03 to 0.25) | 0.07 (−0.07 to 0.21) |

| Perceived screening barriers | ||||

| FOBT | 0.03 (−0.05 to 0.12) | 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.16) | 0.02 (−0.14 to 0.18) | 0.01 (−0.16 to 0.18) |

| Colonoscopy | 0.02 (−0.06 to 0.09) | 0.02 (−0.09 to 0.13) | −0.02 (−0.18 to 0.13) | 0.07 (−0.10 to 0.24) |

| Stage of readiness for screening | 1.32 (1.05 to 1.66)d | 1.44 (1.03 to 2.00)d | 1.69 (1.07 to 2.67)d | 0.86 (0.53 to 1.38) |

| Visit behaviors, %g | ||||

| Discussion CRC screening | 8.6 (3.1 to 14.2)c | 9.2 (1.4 to 17.0)d | 10.5 (−0.2 to 21.2) | 6.0 (−5.7 to 17.8) |

| Recommendation CRC screening | 6.4 (1.0 to 11.8)d | 8.1% (0.4 to 15.8%)d | 8.3 (−2.0 to 18.5%) | 3.1 (−7.5 to 13.7) |

| CRC screening, %h | 0.5 (−4.3 to 5.3) | −0.3 (−7.4 to 6.8) | −1.3 (−9.3 to 6.8) | 4.3 (−6.1 to 14.6) |

CRC = colorectal cancer; EHBM = expanded health belief model; FOBT = fecal occult blood testing; IMCP = interactive multimedia computer program; PE = parameter estimate; SE = self-efficacy.

Parameter estimates for total knowledge (score range = 0–9) and self-efficacy (score range = 1–5) represent the amount of change in score (ie, points); parameter estimates for specific test preference, discussion and recommendation of colorectal cancer screening, and colorectal cancer screening represent percentage point increases or decreases; parameter estimate for stage of readiness represents the odds of an increase in stage.

All sociopsychological factor models were adjusted for the previsit value of the dependent variable and study recruitment center; the entire sample analyses also were adjusted for ethnicity/language strata.

P <.01.

P <.05.

Analyses examined effects on a total colorectal cancer screening knowledge scale, derived by combining the scores for the knowledge of screening test options and knowledge of screening risks and inconveniences scales.

P <.001.

All visit behavior models were adjusted for study recruitment center; the entire sample analyses also were adjusted for ethnicity/language strata.

Based on review of medical records, available for 1,132 participants (575 IMCP patients, 557 control patients). All receipt of screening models were adjusted for study recruitment center; the entire sample analysis also was adjusted for ethnicity/language strata.

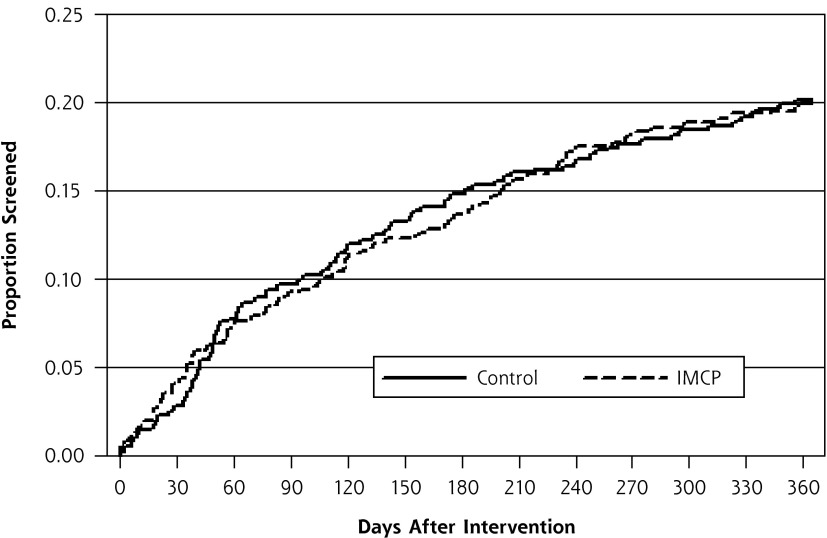

Among 1,132 (97%) patients with available medical records, the tailored IMCP had no greater effect than control on colorectal cancer screening (Table 3). Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves for screening in both study groups during 12 months follow-up.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve for receipt of colorectal cancer screening after intervention according to study group.

IMCP = interactive multimedia computer program.

Note: Screening was ascertained by medical record review.

DISCUSSION

An IMCP tailored to EHBM sociopsychological factors was no more effective than a nontailored informational program in improving objectively measured colorectal cancer screening even though the IMCP successfully enhanced most of the EHBM factors and both targeted visit behaviors, all previously associated with screening. Of previous randomized controlled trials comparing a sociopsychologically tailored colorectal cancer screening intervention with an active control,15,19,20,22,25–30,33 only some reported improvements in screening,19,25,28,29,34 in most instances based on patient report,19,25,28,29 suggesting possible misclassification bias. These observations, plus our current findings, raise doubts about the superiority of sociopsychological tailoring to nontailored approaches in promoting colorectal cancer screening.

Only 1 previous trial of colorectal cancer screening included sociopsychological tailoring in a multiethnic sample as part of a multifaceted intervention, but it did not examine tailoring effects specifically.25 The effects of our IMCP on sociopsychological factors and visit behaviors did not differ significantly among ethnicity/language strata. Although this finding might suggest sociopsychological tailoring holds promise for reducing screening disparities, the lack of superior IMCP effects on screening indicates that promise remains unfulfilled. The greater simplicity and lower cost of the nontailored control compared with the IMCP intervention, coupled with its similar behavioral effects, suggests that wider use of one-time computer-delivered sociopsychological tailoring may not be cost-effective. Others have reached similar conclusions.56

One possible explanation for the lack of superior effects of sociopsychological tailoring on screening is that EHBM factors are insufficiently enhanced. Previsit sociopsychological factor scores were favorable in our sample, leaving relatively little room for improvement. There was no significant effect of the tailored IMCP on screening barriers, and the effect sizes for the other EHBM factors and visit behaviors were small. For example, compared with control, the IMCP produced a 0.16 SD increase in self-efficacy; effect sizes around 0.2 are generally viewed as small.57 Nonetheless, these EHBM factor effect sizes are comparable to those in published trials.10–22

In our sample, a 1 SD increase in self-efficacy was associated with a 5.4% greater likelihood of screening (data not shown, available upon request). Thus, the IMCP self-efficacy effect size of 0.16 would be expected to translate into a less than 1% increase in screening (5.4% × 0.16 = 0.86%). The small estimated IMCP effect on screening is consistent with the findings of prior tailoring trials, most of which focused on EHBM factors. In 2 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials examining sociopsychological tailoring effects on health behaviors (almost exclusively self-reported), the estimated mean behavioral effect sizes were 0.074 (95% CI, 0.066–0.082) and 0.17 (95% CI, 0.14–0.19).23,24 In this context, our findings suggest the need to study the behavioral effects of tailoring to sociopsychological factors other than those in the EHBM. Several promising candidates exist, such as regulatory focus and preference for autonomy-supportive (vs directive) communication.58,59

It may also be that enhancement of complex, temporally far-removed behaviors is too much to expect from a single, brief, computerized tailoring exposure. Weeks to months of delay are common subsequent to a clinician’s order for colorectal cancer screening, particularly for colonoscopy,60 the most frequently utilized test in our sample and nationally.61 We did not serially measure the status of sociopsychological factors, but the salutary effects of tailoring on these factors likely waned with time. Our experience suggests that one-time computerized tailoring may favorably influence immediate sociopsychological and behavioral outcomes, including acceptance of initial care for depression during a linked office visit.62 By contrast, promoting such behaviors as colorectal cancer screening may require repeated tailoring exposures (eg, via the Internet or telephone texting) or linkage with other approaches (eg, reminder e-mails, telephone care management, clinician-focused interventions).63–65

Another possible explanation for the lack of tailoring effects on screening is that the IMCP did not address cultural factors, especially those affecting Hispanic participants. Even so, although differences in screening between ethnicity/language groups were not statistically significant, the IMCP effect on screening was largest in the Hispanic/Spanish group (Table 3). IMCP effects on sociopsychological factors and visit behaviors also were similar among ethnicity/language groups (Table 3), with no significant intervention*ethnicity/language interaction. Furthermore, research suggests that EHBM sociopsychological factors are relevant across cultural groups.25,36

Our study had limitations. Randomization by patient was used for feasibility but may have diluted the intervention effects had study clinicians interacting with IMCP patients treated control patients differently. Record documentation may have been missing for some screened patients, so the screening rates reported here are likely conservative. Still, because rates of missing study data should not differ by study group, comparisons of screening between groups should not have been affected. We measured the study visit behaviors using patient report, which is subject to biases. Alternative methods of assessing visit behaviors also have limitations. For example, clinician reports may also be biased, and observing or recording visits may change the behaviors. In the tailored IMCP (but not control) group, the previsit measures of some EHBM factors were not true baseline (preintervention) measures (Figure 1). As a result, previsit imbalances favored the IMCP group for the knowledge of screening harms and inconveniences and self-efficacy measures (Table 2), leaving less room for improvement in these factors. Because analyses of IMCP effects on these factors are biased toward the null, our estimates for these factors may be conservative.

In conclusion, 1-time EHBM sociopsychological factor tailoring delivered by an IMCP was no more effective than nontailored information in encouraging objectively measured colorectal cancer screening in a multiethnic sample, despite salutary effects on sociopsychological factors and visit behaviors predictive of screening. Furthermore, IMCP effects did not differ significantly among ethnicity and preferred language subgroups. The findings raise doubts regarding the utility of single-exposure sociopsychological factor tailoring in promoting and reducing ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the following individuals, who facilitated recruitment and participation of patients in the study: Dionne Evans-Dean, MHA, Dustin Gottfeld, BS, Lizette Macias, BS, Lori Reid, RN, and Linda Marks, MPA (Sacramento); Mechelle R. Sanders, BA and Leticia E. Serrano, AAS (Rochester); Sandra Monroy, MA (New York City); and Brandon Tutt, MA (Colorado). We also wish to thank Robert Burnett, MA, for his programming contributions to the tailored software program. Finally, we are indebted to all of the primary care offices and patients who participated.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: This work was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA131386) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (CA13138602S1).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00786747

References

- 1.Klabunde CN, Cronin KA, Breen N, Waldron WR, Ambs AH, Nadel MR. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011; 20(8):1611–1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jerant AF, Arellanes RE, Franks P. Factors associated with Hispanic/non-Hispanic white colorectal cancer screening disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1241–1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabatino SA, Lawrence B, Elder R, et al. Community Preventive Services Task Force. Effectiveness of interventions to increase screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers: nine updated systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):97–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chua RY, Iyengar SS. Empowerment through choice? A critical analysis of the effects of choice in organizations. Res Organ Behav. 2006;27:41–79 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, Fishbein M, Dijkstra A. Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(3):454–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerant A, Sohler N, Fiscella K, Franks B, Franks P. Tailored interactive multimedia computer programs to reduce health disparities: opportunities and challenges. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):323–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jerant A, Kravitz RL, Rooney M, Amerson S, Kreuter M, Franks P. Effects of a tailored interactive multimedia computer program on determinants of colorectal cancer screening: a randomized controlled pilot study in physician offices. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(1):67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawl SM, Skinner CS, Perkins SM, et al. Computer-delivered tailored intervention improves colon cancer screening knowledge and health beliefs of African-Americans. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(5):868–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosher CE, Fuemmeler BF, Sloane R, et al. Change in self-efficacy partially mediates the effects of the FRESH START intervention on cancer survivors’ dietary outcomes. Psychooncology. 2008;17(10): 1014–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Napolitano MA, Papandonatos GD, Lewis BA, et al. Mediators of physical activity behavior change: a multivariate approach. Health Psychol. 2008;27(4):409–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emmons KM, Wong M, Puleo E, Weinstein N, Fletcher R, Colditz G. Tailored computer-based cancer risk communication: correcting colorectal cancer risk perception. J Health Commun. 2004;9(2): 127–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costanza ME, Luckmann R, Stoddard AM, et al. Using tailored telephone counseling to accelerate the adoption of colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31(3):191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers RE, Hyslop T, Sifri R, et al. Tailored navigation in colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2008;46 (9)(Suppl 1): S123–S131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christy SM, Perkins SM, Tong Y, et al. Promoting colorectal cancer screening discussion: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):325–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glenn BA, Herrmann AK, Crespi CM, et al. Changes in risk perceptions in relation to self-reported colorectal cancer screening among first-degree relatives of colorectal cancer cases enrolled in a randomized trial. Health Psychol. 2011;30(4):481–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruffin MT, IV, Fetters MD, Jimbo M. Preference-based electronic decision aid to promote colorectal cancer screening: results of a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller DP, Jr, Spangler JG, Case LD, Goff DC, Jr, Singh S, Pignone MP. Effectiveness of a web-based colorectal cancer screening patient decision aid: a randomized controlled trial in a mixed-literacy population. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(6):608–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kukafka R, Lussier YA, Eng P, Patel VL, Cimino JJ. Web-based tailoring and its effect on self-efficacy: results from the MI-HEART randomized controlled trial. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002;410–414 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rawl SM, Champion VL, Scott LL, et al. A randomized trial of two print interventions to increase colon cancer screening among first-degree relatives. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(2):215–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krebs P, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS. A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Prev Med. 2010; 51(3–4):214–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):673–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh JM, Salazar R, Nguyen TT, et al. Healthy colon, healthy life: a novel colorectal cancer screening intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(1):1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vernon SW, Bartholomew LK, McQueen A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored interactive computer-delivered intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening: sometimes more is just the same. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(3):284–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers RE, Sifri R, Hyslop T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the impact of targeted and tailored interventions on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer. 2007;110(9):2083–2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manne SL, Coups EJ, Markowitz A, et al. A randomized trial of generic versus tailored interventions to increase colorectal cancer screening among intermediate risk siblings. Ann Behav Med. 2009; 37(2):207–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcus AC, Mason M, Wolfe P, et al. The efficacy of tailored print materials in promoting colorectal cancer screening: results from a randomized trial involving callers to the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. J Health Commun. 2005;10(Suppl 1):83–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinberg DS, Keenan E, Ruth K, Devarajan K, Rodoletz M, Bieber EJ. A randomized comparison of print and web communication on colorectal cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(2):122–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neville LM, O’Hara B, Milat AJ. Computer-tailored dietary behaviour change interventions: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(4):699–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rimer BK, Conaway M, Lyna P, et al. The impact of tailored interventions on a community health center population. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37(2):125–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myers RE, Bittner-Fagan H, Daskalakis C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored navigation and a standard intervention in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013; 22(1):109–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menon U, Belue R, Wahab S, et al. A randomized trial comparing the effect of two phone-based interventions on colorectal cancer screening adherence. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(3):294–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, von Friederichs-Fitzwater MM, Tancredi DJ, Franks P. Physician counseling for colorectal cancer screening: impact on patient attitudes, beliefs, and behavior. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(6):673–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cameron KA, Francis L, Wolf MS, Baker DW, Makoul G. Investigating Hispanic/Latino perceptions about colorectal cancer screening: a community-based approach to effective message design. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68(2):145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Cancer Society. Guidelines for the early detection of cancer. 2013. http://www.cancer.org/Healthy/FindCancerEarly/CancerScreeningGuidelines/american-cancer-society-guidelines-for-the-early-detection-of-cancer

- 38.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: chance, not choice. Lancet. 2002;359(9305):515–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pressman RS. Software Engineering: A Practitioner’s Approach. 6th ed New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jerant A, Kravitz RL, Fiscella K, et al. Effects of tailored knowledge enhancement on colorectal cancer screening preference across ethnic and language groups. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(1):103–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connor AM, Fiset V, DeGrasse C, et al. Decision aids for patients considering options affecting cancer outcomes: evidence of efficacy and policy implications. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1999;25(25):67–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kreuter M, Farrell D, Olevitch L, Brennan L. Tailoring Health Messages: Customizing Communication With Computer Technology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deci EL, Ryan RM. The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53(6):1024–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller SM. Monitoring versus blunting styles of coping with cancer influence the information patients want and need about their disease. Implications for cancer screening and management. Cancer. 1995;76(2):167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson C, Stunkard AJ. Personal control and health promotion. Soc Sci Med. 1989;28(8):819–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freed E, Long D, Rodriguez T, Franks P, Kravitz RL, Jerant A. The effects of two health information texts on patient recognition memory: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(2): 260–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Cancer Institute. Tests to detect colorectal cancer and polyps. 2011. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/detection/colorectal-screening

- 48.Instituto Nacional del Cáncer. Exámenes para detectar el cáncer colorrectal y los pólipos. 2011. http://www.cancer.gov/espanol/recursos/hojas-informativas/deteccion-diagnostico/examenes-colorrectal

- 49.O’Connor AM. User manual - knowledge. 2000. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Knowledge.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vernon SW, Myers RE, Tilley BC. Development and validation of an instrument to measure factors related to colorectal cancer screening adherence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6(10):825–832 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Connor AM. User manual - decision self-efficacy scale. 1995. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decision_SelfEfficacy.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rawl S, Champion V, Menon U, Loehrer PJ, Vance GH, Skinner CS. Validation of scales to measure benefits of and barriers to colorectal cancer screening. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2001;19:47–63 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prochaska JO, Goldstein MG. Process of smoking cessation. Implications for clinicians. Clin Chest Med. 1991;12(4):727–735 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, Littenberg B. The Single Item Literacy Screener: evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lairson DR, DiCarlo M, Myers RE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of targeted and tailored interventions on colorectal cancer screening use. Cancer. 2008;112(4):779–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis For the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Resnicow K, Davis RE, Zhang G, et al. Tailoring a fruit and vegetable intervention on novel motivational constructs: results of a randomized study. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cesario J, Grant H, Higgins ET. Regulatory fit and persuasion: transfer from “Feeling Right”. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86(3):388–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Denberg TD, Melhado TV, Coombes JM, et al. Predictors of nonadherence to screening colonoscopy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):989–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jerant AF, Fenton JJ, Franks P. Determinants of racial/ethnic colorectal cancer screening disparities. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1317–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kravitz RL, Franks P, Feldman MD, et al. Patient engagement programs for recognition and initial treatment of depression in primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(17):1818–1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Cassells A, et al. Telephone care management to improve cancer screening among low-income women: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):563–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferreira MR, Dolan NC, Fitzgibbon ML, et al. Health care provider-directed intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among veterans: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1548–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schneider F, de Vries H, Candel M, van de Kar A, van Osch L. Periodic email prompts to re-use an internet-delivered computer-tailored lifestyle program: influence of prompt content and timing. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(1):e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]