Abstract

Fear memories guide adaptive behavior in contexts associated with aversive events. The hippocampus forms a neural representation of the context that predicts aversive events. Representations of context incorporate multisensory features of the environment, but must somehow exclude sensory features of the aversive event itself. We investigated this selectivity using cell type–specific imaging and inactivation in hippocampal area CA1 of behaving mice. Aversive stimuli activated CA1 dendrite-targeting interneurons via cholinergic input, leading to inhibition of pyramidal cell distal dendrites receiving aversive sensory excitation from the entorhinal cortex. Inactivating dendrite-targeting interneurons during aversive stimuli increased CA1 pyramidal cell population responses and prevented fear learning. We propose subcortical activation of dendritic inhibition as a mechanism for exclusion of aversive stimuli from hippocampal contextual representations during fear learning.

Aversive stimuli cause animals to associate their environmental context with these experiences, allowing for adaptive defensive behaviors during future exposure to the context. This process of contextual fear conditioning (CFC) is dependent upon the brain performing two functions in series: first developing a unified representation of the multisensory environmental context (the conditioned stimulus, CS), then associating this CS with the aversive event (unconditioned stimulus, US) for memory storage (1–5). The CS is encoded by the dorsal hippocampus, whose outputs are subsequently associated with the US through synaptic plasticity in the amygdala (6–10). The hippocampus must incorporate multisensory features of the environment into a representation of context but, paradoxically, must exclude sensory features during the moment of conditioning, when the primary sensory attribute is the US. The sensory features of the US may disrupt conditioning (11). Although the cellular and circuit mechanisms of fear learning and sensory convergence have been extensively studied in the amygdala (3, 5, 12), much less is known about how the neural circuitry of the hippocampus contributes to fear conditioning.

The primary output neurons of the hippocampus, pyramidal cells (PCs) in area CA1, are driven to spike by proximal dendritic excitation from CA3 and distal dendritic excitation from the entorhinal cortex (13). Whereas CA3 stores a unified representation of the multisensory context (14), the entorhinal cortex conveys information pertaining to the discrete sensory attributes of the context (15). At the cellular level, nonlinear interactions between inputs from CA3 and entorhinal cortex in the dendrites of PCs can result in burst-spiking output and plasticity (16–18). PCs can carry behaviorally relevant information in the timing of single spikes (19), spike rate (13), and spike bursts (20), but information conveyed with just bursts of spikes is sufficient for hippocampal encoding of context during fear learning (21). Distinct CA1 PC firing patterns are under the control of specialized local inhibitory interneurons (22, 23). Whereas spike timing is regulated by parvalbumin-expressing (Pvalb+) interneurons that inhibit the perisomatic region of PCs, burst spiking is regulated by somatostatin-expressing (Som+) interneurons that inhibit PC dendrites (24–26). This functional dissociation suggests that CA1 Som+ interneurons may play an important role in CFC. However, the activity of specific interneurons during CFC and their causal influence remain unknown.

To facilitate neural recording from multiple genetically and anatomically defined circuit elements in CA1 during CFC with two-photon Ca2+ imaging, we developed a variation of CFC for head-fixed mice (hf-CFC). We combined Ca2+ imaging with cell-type–specific inactivation techniques in head-fixed and freely moving mice to investigate the contribution of CA1 neural circuitry to fear learning.

CFC for Head-Fixed Mice

Conditioned fear in rodents is typically measured in terms of freezing upon re-exposure to the context where the subject experienced an aversive stimulus (3, 5). However, using freezing as a conditioned response (CR) is problematic in head-fixed mice. Instead, we measured learned fear using conditioned suppression of water licking (27, 28), an established measure of fear that translates well to head-fixed preparations. We trained water-restricted mice to lick for small water rewards while head-fixed on a treadmill (29), then exposed them to two multisensory contexts (sets of auditory, visual, olfactory, and tactile cues) over three consecutive days and monitored their rate of licking (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A) (see Materials and Methods). On the second day, we paired the air-puff US with one of the contexts and assessed lick rate in both contexts the following day. We found that US pairing caused a decrease in the rate of licking in the conditioned context (CtxC) but not the neutral (CtxN) (Fig. 1, B and C, and fig. S1, B to E).

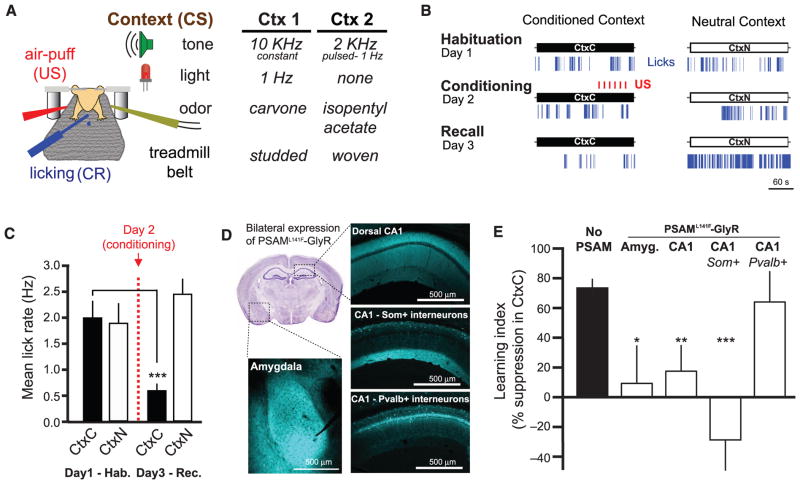

Fig. 1. Som+ interneurons in CA1 are required for learning hf-CFC.

(A) Schematic of hf-CFC task. A head-fixed mouse on a treadmill is exposed to contexts (CS) defined by distinct sets of multisensory stimuli. We used air puffs as the US and suppression of water-licking as a measure of learned fear (CR). The two distinct contexts used in this study are described at right. (B) Behavioral data from an example mouse over the hf-CFC paradigm. Conditioned (CtxC) and neutral (CtxN) contexts are each presented once a day, and lick rate is assessed during the 3-min context. (C) Summary data for 19 mice [two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), context x session, F(1,19) = 9.34, P < 0.01]. Mice showed a selective decrease in mean lick rate between habituation and recall in CtxC but not CtxN (paired sign tests). (D) Viral expression of PSAML141F-GlyR in the amygdala or dorsal CA1, revealed by α-bungarotoxin-Alexa647 immunostaining. All injections were bilateral; for simplicity, only one hemisphere is shown. Image at top left is from the Allen Brain Atlas. (E) Summary data for mice injected with PSEM89 systemically 15 min before the conditioning session in CtxC (day 2 of hf-CFC paradigm). Learning is assessed by the percentage of lick-rate decrease in the CtxC recall session (day 3) relative to the mean lick rate in all sessions. Mice expressing PSAML141F-GlyR in amygdala cells (Amyg., n = 6 mice), dorsal CA1 cells (CA1, n = 5 mice), or CA1 Som+ interneurons (CA1-Som+, n = 8 mice) showed impaired learning compared with mice not expressing PSAML141F-GlyR (No PSAM, n = 11 mice), whereas mice expressing PSAML141F-GlyR in CA1 Pvalb+ interneurons (CA1-Pvalb+, n = 4 mice) did not. Comparisons are Mann-Whitney U tests. Error bars, mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

We used pharmacogenetic neuronal inactivation to test the necessity of the hippocampus and amygdala for the encoding of hf-CFC. We targeted bilateral injections of recombinant adeno-associated virus [rAAV(Synapsin-PSAML141F-GlyR)] to express the ligand-gated Cl− channel PSAML141F-GlyR in either dorsal hippocampal area CA1 or the amygdala in wild-type mice (Fig. 1D). Neurons expressing PSAML141F-GlyR are inactivated for ~15 to 20 min upon systemic administration of its ligand PSEM89 (60 mg per kg of weight, intraperitoneally) (30). We administered PSEM89 to mice before conditioning in CtxC, and tested their memory 24 hours later without the drug by assessing lick suppression in CtxC recall compared with mean licking across all sessions. In agreement with conventional freely moving CFC results (6, 7, 31, 32), we found that inactivating neurons in dorsal CA1 or the amygdala prevented contextual fear learning (Fig. 1E).

Som+ Interneurons Are Required for CFC

To determine the relevance of CA1 inhibitory circuits for the acquisition of hf-CFC, we asked whether acute inactivation of γ–aminobutyric acid-releasing (GABAergic) interneuron subclasses in CA1 would alter learning. We injected rAAV (Synapsin-PSAML141F-GlyR)cre bilaterally into CA1 of Som-cre or Pvalb-cre mice to express PSAML141F-GlyR selectively in either Som+ dendrite-targeting interneurons or Pvalb+ perisomatic-targeting interneurons, respectively (25) (Fig. 1D and fig. S2). Systemic PSEM89 administration during conditioning prevented learning in mice expressing PSAML141F-GlyR in CA1 Som+ interneurons, but not in mice expressing PSAML141F-GlyR in CA1 Pvalb+ interneurons (Fig. 1E).

We repeated our inactivation experiments in conventional CFC experiments with freely-moving mice, with a foot-shock US and freezing as the CR. Inactivating CA1 Som+ interneurons during conditioning prevented recall 24 hours later without the drug, while inactivating Pvalb+ interneurons had no effect (fig. S3, A and B). Inactivating Som+ interneurons or Pvalb+ interneurons did not alter perception of the US, as hippocampal-independent auditory cued conditioning was left intact (fig. S3C). Inactivating Som+ neurons did not simply alter CS perception, as inactivation during both conditioning and recall also prevented learning (fig. S4). The absence of a role for Pvalb+ interneurons in CFC was not due to insufficient neuronal inactivation. In agreement with previous findings (33), this manipulation reduced performance in a spatial working memory task (fig. S5).

The US Activates Som+ Interneurons

We used two-photon Ca2+ imaging to record the activity of CA1 Som+ interneurons over the course of hf-CFC. We unilaterally injected rAAV(Synapsin-GCaMP5G)cre into dorsal CA1 of Som-cre mice to express the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP5G (34) in the somata, dendrites, and axons of Som+ interneurons (Fig. 2A). To visualize CA1 neurons in vivo, we used established surgical techniques (29, 35) to implant a chronic imaging window superficial to dorsal CA1. After recovery, water restriction, and habituation to head-restraint, we engaged mice in the hf-CFC task while imaging Ca2+-evoked GCaMP5G fluorescence transients from Som+ interneuron somata in the oriens and alveus layers of CA1. We returned to the same field of view for each of the six sessions of hf-CFC (Fig. 2B) and processed fluorescence time-series data using established methods for motion-correction and signal processing (29, 36). Strikingly, Som+ interneurons displayed increased activity in response to the US during hf-CFC (example neuron in Fig. 2B).

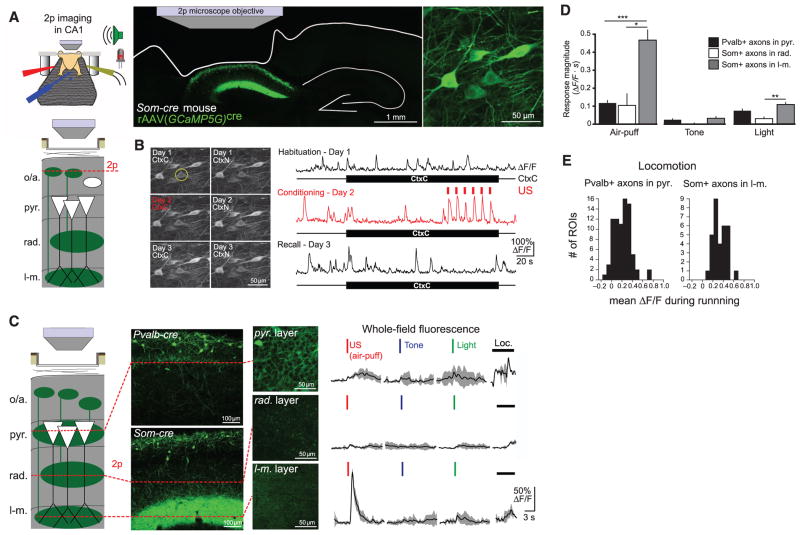

Fig. 2. Som+ interneurons targeting stratum lacunosum-moleculare are activated by the US.

(A) (Top left) Schematic of hf-CFC during two-photon (2p) imaging from hippocampal neurons. (Bottom left) Schematic of recording configuration, with 2p imaging from Som+ interneurons in the oriens/alveus layers of CA1 in vivo (o/a, strata oriens/alveus; pyr., stratum pyramidale; rad., stratum radiatum; l-m., stratum lacunosum-moleculare). (Right) Confocal image of coronal section from mouse expressing GCaMP5G in Som+ interneurons in dorsal CA1. The 2p microscope objective and landmarks showing the outline of the brain, including the removed cortex and the contralateral hippocampus, are illustrated. An in vivo 2p image of GCaMP-expressing Som interneurons is shown at far right. (B) (Left) 2p images of the same field of view from (A) for the six hf-CFC sessions over the course of 3 days. Images are time averages of 2000 motion-corrected imaging frames collected for each imaging session. (Right) ΔF/F traces from an example Som+ CA1 interneuron (circled at left) over the three daily exposures to CtxC. (C) (Left) Schematic of recording configuration, with in vivo 2p imaging from Som+ axons in radiatum or lacunosum-moleculare layers of CA1, Pvalb+ axons in the pyramidale layer. (Middle) Expression of GCaMP5G in layer-specific axonal projections, revealed by confocal images of coronal sections and in vivo 2p images of each layer. (Right) Example trial-averaged responses (five trials each presented in pseudorandom order) of layer-specific whole-field fluorescence responses to discrete 200-ms sensory stimuli and locomotion (mean with shaded SD). (D) Summary data for sensory stimulation experiments shown in (C). Responses are quantified as the mean integral of whole-field ΔF/F over the 3 s after the stimulus. [two-way ANOVA, axon-type x stimulus type, F(4,84) = 16.9, P < 0.001; post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests]. Error bars, mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (E) Summary data for whole-field ΔF/F responses to treadmill-running. Pvalb+ axons in pyramidale exhibit locomotion responses similar to Som+ axons in lacunosum-moleculare (Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.101).

To investigate the dynamics of stimulus-evoked GABAergic signaling in more detail, we imaged CA1 inhibitory neurons during the pseudorandom presentation of discrete sensory stimuli from the hf-CFC task: light flashes and tones, which were elements of the CS, or air-puffs, which served as the US. To image a greater variety of interneurons simultaneously, we injected cre-independent rAAV(Synapsin-GCaMP5G) into CA1 of Som-cre mice crossed with a tdTomato reporter line, which allowed us to simultaneously image sensory responses of Som+ and Som− interneurons (fig. S6A). Air puffs activated most Som+ interneurons (fig. S6B), whereas a smaller proportion of Som− and Pvalb+ interneurons had comparable responses (fig. S6C).

Not all Som+ interneurons were activated by the air puff, which could reflect a difference between bistratified cells and oriens-lacunosum-moleculare (OLM) cells, both of which are labeled in Som-cre mice (25). The axons of bistratified cells arborize in stratum oriens and radiatum, whereas those of OLM cells arborize in stratum lacunosum-moleculare (22, 23). These two inhibitory projections contact the dendritic compartments of CA1 PCs that receive input from CA3 and the entorhinal cortex, respectively, suggesting potentially distinct functions. To isolate the relative contributions of these two inhibitory pathways to US-evoked signaling, we labeled Som+ neurons with GCaMP5G in Som-cre mice and focused our imaging plane on the axons of bistratified cells in radiatum, or the axons of OLM cells in lacunosum-moleculare (Fig. 2C). Whole-field recording from the dense Som+ axonal termination in lacunosum-moleculare revealed a fast, high-amplitude increase in fluorescence in response to the air puff but not the tone or light (Fig. 2D). In contrast, the lower density axons in radiatum revealed little response to these stimuli. We also expressed GCaMP5G in Pvalb-cre mice to record from Pvalb+ basket cell axons in stratum pyramidale. These high-density axons had much smaller responses to the US (Fig. 2, C and D) but responded robustly to treadmill running (Fig. 2E).

Acetylcholine Drives Som+ Interneurons

To drive fast-onset responses to the US, Som+ interneurons in CA1 must receive a time-locked source of US-driven excitation. However, most excitatory inputs to OLM cells are synapses from CA1 PCs (23), and PCs do not encode the US (5, 10) or robustly respond to it (fig. S6C) (37–40). Alternatively, Som+ interneurons could be excited by extrahippocampal sources such as subcortical neuromodulatory inputs. Indeed, OLM cells in CA1 can be depolarized through both nicotinic and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (41, 42), and lesions of cholinergic inputs from the medial septum are known to prevent the suppressive effects of aversive stimuli on CA1 spiking activity (38, 43–45). Additionally, neocortical interneurons have been demonstrated to respond to aversive stimuli through cholinergic input (46).

To probe the source of US-evoked activation of Som+ interneurons, we modified our imaging window to allow for local pharmacological manipulation of the imaged neural tissue (fig. S7A) (29). We applied antagonists of neuromodulatory receptors through the imaging window, which passively diffused into CA1; there, we imaged GCaMP5G-expressing Som+ interneuron responses to stimuli before and after drug administration (Fig. 3, A and B). Blockade of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) did not decrease Som+ interneuron responses to air puffs (1 mM mecamylamine) (Fig. 3C) but instead modestly increased responses. However, blockade of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (mAChR) significantly reduced air-puff responses in Som+ interneurons (1 mM scopolamine) (Fig. 3C). We recapitulated this result with more selective blockade of type 1 mAChRs (1 mM pirenzepine; Fig. 3, B and C), which reduced air-puff–evoked Som+ interneuron responses in a dose-dependent manner (fig. S7B). Metabotropic receptors like mAChRs generally act on slower time scales, but studies in brain slices have demonstrated that muscarinic input can evoke fast-onset depolarization and spiking of CA1 OLM cells (41, 47). mAChRs in dorsal hippocampus are required for encoding CFC (48), and our results suggest a possible circuit mechanism that contributes to this requirement. This effect was not a consequence of reduced di-synaptic drive from m1AChR-responsive PCs (49), because m1AChR block did not substantially alter air-puff–evoked activity in the minority of responding PCs (fig. S7C), and responses of Som+ interneurons were not substantially changed by blockade of glutamatergic AMPA receptors (20 μM 2,3-Dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide) (Fig. 3C).

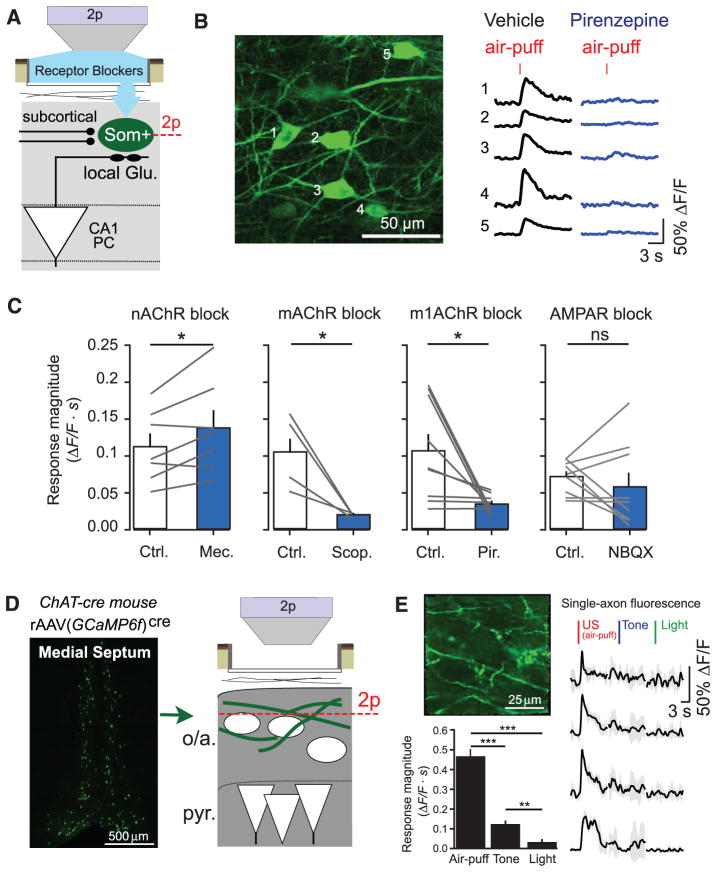

Fig. 3. Cholinergic inputs from the medial septum drive CA1 Som+ interneurons during the US.

(A) Schematic of recording configuration, with 2p imaging from Som+ interneurons in the oriens and alveus layers of CA1, and local pharmacological manipulations through an aperture in the imaging window. (B) Example in vivo 2p image of GCaMP-expressing Som+ interneurons and their fluorescence responses to air puffs in vehicle (cortex buffer) and in the presence of 1 mM pirenzepine. (C) Summary data for local pharmacological manipulations. Each point is the mean response of all Som+ interneurons within a field of view (FOV) to air puffs (5 trials each) in vehicle (Ctrl.) and upon drug application (nAChR block, 7 FOVs in 5 mice; mAChR block, 4 FOVs in 3 mice; m1AChR block, 9 FOVs in 5 mice; AMPAR block, 9 FOVs in 4 mice). Comparisons are paired t tests between drug conditions. (D) (Left) Coronal confocal image of GCaMP6f+/ChAT+ neurons in the medial septum of a ChAT-cre mouse. (Right) Schematic of recording configuration, with 2p imaging from ChAT+ axons in the oriens and alveus layers of CA1. (E) (Top left) Example in vivo 2p image of GCaMP6f-expressing ChAT+ axons in CA1. (Right) Mean responses of individual axons to sensory stimuli. (Bottom left) Summary data from ChAT+ axons averaged within each FOV (sign tests; n = 20 FOVs in 2 mice). Error bars, mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, nonsignificant.

Cholinergic input to the hippocampus arises from projection neurons in the medial septum (50), a region required for CFC (51). To directly record the activity of these projections, we injected rAAV(ef1α-DIO-GCaMP6f)cre into the medial septum (MS) of ChAT-cre mice to express the sensitive Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f (52) in cholinergic projection neurons. We imaged cholinergic (ChAT+) axons in the oriens and alveus layers of CA1 during sensory stimulation (Fig. 3D and fig. S8). ChAT+ axons responded robustly to air puffs, with smaller responses to tones and very little response to light flashes (Fig. 3E). ChAT+ axon responses were independent of air-puff duration, similar to Som+ axons in lacunosum-moleculare (fig. S9) but differing from the graded responses of septohippocampal GABAergic projections (29).

Coaligned Dendritic Inhibition and Excitation

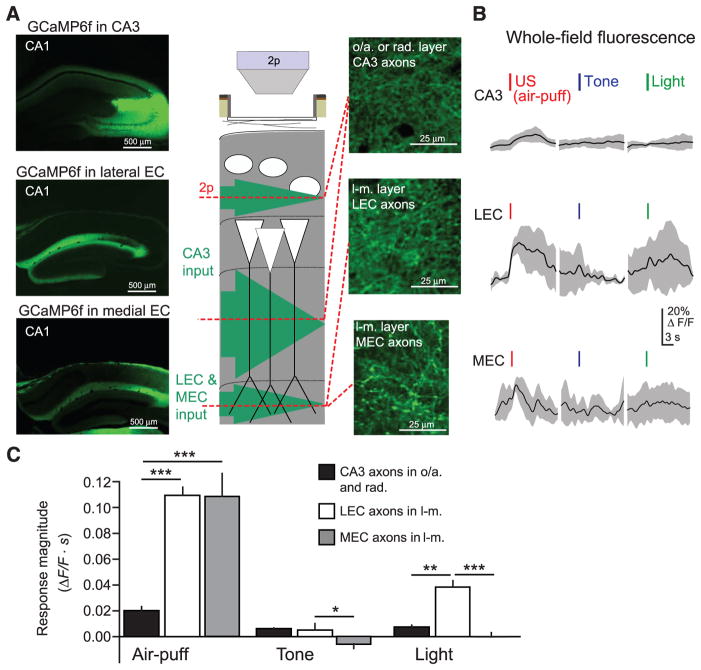

The distal tuft dendrites of PCs receive excitatory input from the entorhinal cortex, raising the possibility that the inhibition we observe is counteracting US-evoked excitation to these dendrites. The entorhinal cortex provides sensory information to CA1 (15), including projections from the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC) (53) and nonspatial neurons of the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) (54) that synapse with CA1 PC distal dendrites. In contrast, the proximal dendrites of PCs receive input from CA3 believed to carry stored contextual representations rather than sensory information (14). To directly record from these excitatory inputs, we injected rAAV(Synapsin-GCaMP6f) into CA3, LEC, or MEC and imaged axonal activity in ipsilateral CA1 layers oriens/radiatum (CA3 axons) or lacunosum-moleculare (LEC and MEC axons) (Fig. 4A and fig. S10, A and B). Sensory inputs, particularly aversive air puffs, evoked stronger signals from LEC and MEC axonal boutons compared with CA3 axonal boutons, reflected by changes in whole-field fluorescence (Fig. 4, B and C). These data indicate that US-driven inhibition of PC distal tuft dendrites in stratum lacunosum-moleculare is coaligned with excitatory input, which could effectively limit dendritic depolarization (55). Compartmentalized inhibition can also prevent propagation of excitation from distal to proximal dendrites (16–18), potentially preserving responses of PCs to sparse excitation from CA3 axons (fig. S10C). Similar US-driven signals may occur in other excitatory inputs to lacunosum-moleculare, such as the thalamic reuniens nucleus.

Fig. 4. US-evoked excitatory input to CA1 PC distal dendrites.

(A) (Left) Confocal images of coronal sections from dorsal hippocampus, showing expression of GCaMP6f in CA1-innervating axons from CA3 (top), LEC (middle), or MEC (bottom). (Middle) Schematic of recording configuration, with 2p imaging from excitatory axons in the oriens/radiatum layers (CA3 projections) or lacunosum-moleculare layer (LEC or MEC projections) of CA1. (Right) Example in vivo 2p images of GCaMP6f-expressing axons in CA1 (CA3, top; LEC, middle; MEC, bottom). (B) Example mean whole-field fluorescence traces from CA3, LEC, and MEC axons [examples in (A)], in response to discrete sensory stimuli (mean with shaded SD). (C) Summary data for sensory stimulation experiments. Responses are quantified as the mean integral of ΔF/F over the 3 s after the stimulus (two-way ANOVA, axon type x stimulus type, F(4,84) = 10.7, P < 0.001; post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests). Error bars, mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Consequences for Hippocampal Output and Learning

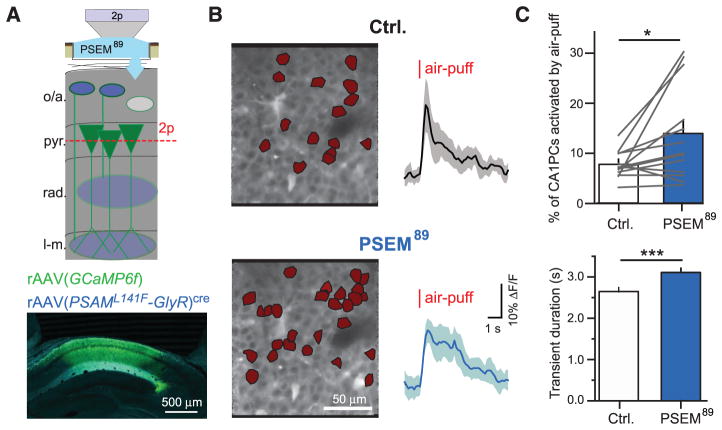

Ultimately, any dysfunction in hippocampal encoding of context is likely reflected in changes to the primary hippocampal output neurons: CA1 PCs. Som+ interneurons appear poised to inhibit excitation during the US and are required for CFC, but the response of PCs in their absence is unknown. To probe the consequences of inactivating Som+ interneurons for US-evoked PC population activity, we simultaneously imaged air-puff responses of ~150 to 200 PCs while inactivating Som+ interneurons. We injected rAAV(Synapsin-PSAML141F-GlyR)cre and rAAV(Synapsin-GCaMP6f) into CA1 of Som-cre mice, and imaged air-puff–evoked responses of PC populations in pyramidale before and during Som+ interneuron inactivation with local application of PSEM89 through the hippocampal imaging window (Fig. 5A). Although systemic PSEM89 reduced air-puff–evoked Ca2+ activity in Som+/PSAML141FGlyR+ interneurons (fig. S11), we applied PSEM89 locally to the imaging window to extend the duration of neuronal inactivation. We imaged PC populations during control conditions and PSEM89 application, identifying neurons with significant air-puff–evoked Ca2+ transients (fig. S12) (36). Inactivating Som+ interneurons significantly increased the number of PCs activated by the air puff within a field of view (Fig. 5, B and C) and significantly increased the duration of Ca2+ transients in PCs that responded to the US in both control and PSEM89 conditions (Fig. 5, B and C). Extended transient duration likely corresponds to the longer spike bursts previously reported from electrophysio-logical measurements of CA1 PCs upon inactivating Som+ interneurons (25, 26). These effects were not observed in control mice that did not express PSAML141F-GlyR (fig. S13A). Non-specific reduction in inhibition with GABAAR blocker bicuculine substantially increased the number of PCs responding to the air puff and their duration (fig. S13B), suggesting that other inhibitory synapses in CA1 also contribute to the control of PC population activity during aversive sensory events.

Fig. 5. Effects of inactivating CA1 Som+ interneurons on US-evoked PC population activity.

(A) (Top) Schematic of recording configuration, with 2p imaging from CA1 PC populations in the pyramidale layer of CA1 and local pharmacologenetic manipulation of PSAML141F-GlyR–expressing Som+ interneurons through an aperture in the imaging window. (Bottom) Confocal image of coronal CA1 sections, with GCaMP6f expression in all neurons (green) and PSAML141F-GlyR expression in Som+ interneurons, revealed by α-BTX immunostaining (blue). (B) (Left) Corrected time-average images of example recordings in pyr. of a mouse expressing PSAML141F-GlyR in Som+ interneurons. PCs with significant US responses are marked in red. (Right) Mean ΔF/F responses of cells active in both control and PSEM89 conditions from left (shading is SD). (C) Summary data for multiple FOVs between drug conditions. (Top) Mean percentage of significantly active CA1 PCs (ctrl, 7.6 ± 0.7%; PSEM89, 13.7 ± 2.5%; n = 13 FOVs; paired t test). (Bottom) Mean duration of significant transients in cells active in both drug conditions (ctrl, 2.64 ± 0.09 s; PSEM89, 3.09 ± 0.09 s; n = 96 cells; paired t test). Error bars, mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

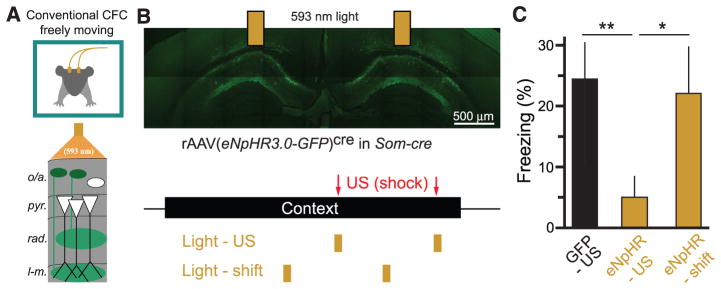

Our imaging data suggest that Som+ interneurons are required for CFC because of their activation during the US. To test this hypothesis directly in a conventional CFC task, we used optogenetic methods in freely moving mice to inactivate Som+ interneurons selectively during the footshock US (Fig. 6A). We expressed the light-gated Cl− pump halorhodopsin (56) in Som+ interneurons by injecting rAAV(Synapsin-eNpHR3.0-eGFP)cre bilaterally into dorsal CA1 of Som-cre mice (fig. S14A) and implanting optic fibers over the injection sites. We used a CFC paradigm with two footshocks, which were each accompanied by coincident illumination of dorsal CA1 with 593-nm light (Fig. 6B), which suppressed spiking of Som+/eNpHR3.0+ neurons (fig. S14b). Inactivating Som+ interneurons during the US significantly reduced conditioned freezing 24 hours later compared with controls injected with rAAV(Synapsin-eGFP)cre (Fig. 6, B and C). Importantly, shifting the optical suppression of Som+ interneurons to 30 s before each US did not reduce freezing (Fig. 6, B and C).

Fig. 6. Inactivating CA1 Som+ interneurons during the US alone is sufficient to prevent CFC.

(A) Schematic of optogenetic experiments in freely moving mice. Bilateral optic fibers deliver 593-nm light to inhibit eNpHR3.0-eGFP–expressing Som+ interneurons in CA1 during CFC in freely moving mice. (B) (Top) Confocal image of eNpHR3.0-eGFP–expressing Som+ interneurons in dorsal CA1 and indication of optic fiber positions. (Bottom) Experimental protocol. Mice are exposed to a context for 3 min, with two footshocks (2 s, 1 mA) 118 s and 178 s into the context. Two pulses of 593-nm light (6 s) were delivered through bilateral optical fibers starting at 116 s and 176 s (Light-US group) or 86 s and 146 s (Light-shift group). (C) Summary data for optogenetic stimulation experiments. GFP-US, n = 6 mice; eNpHR-US, n = 8 mice; eNpHR-shift, n = 6 mice; one-way ANOVA, F(2,19) = 3.87, P < 0.05; comparisons are unpaired t tests. Error bars, mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Classical fear conditioning implies a separation of CS and US prior to their association in the amygdala (3–5). In the case of cued fear conditioning (e.g., tone and shock), the brain achieves CS-US segregation by separate anatomical pathways for auditory and aversive somatosensory inputs (57, 58). Standard models of CFC also assume that the hippocampus does not receive information about the US; rather, the hippocampus encodes the CS alone, whose outputs to the amygdala can be paired with the US for associative conditioning (fig. S15, A and B). However, here we observe a direct cortical excitatory input to CA1 during the US via the entorhinal cortex, indicating an anatomical overlap between sensory information for CS and US before the amygdala (59, 60). This US may impede contextual conditioning (11). We suggest an alternative conceptual model for CFC that addresses the problem of sensory convergence in the hippocampus. In this model, subcortical neuromodulatory input drives CA1 Som+ interneurons to selectively inhibit integration of the excitatory input pathway carrying US information to CA1. These data suggest a circuit mechanism for previously reported suppression of CA1 activity upon aversive stimulation (37–40). Compartmentalized inhibition suppresses integration of excitatory input in PC distal dendrites, which reduces US-evoked CA1 PC activity and can help limit interference of the US with CS encoding. This circuit can ensure that hippocampal output reliably encodes the CS during learning, so that memories stored downstream in the amygdala can be reactivated by exposure to the CS alone (fig. S15, C and D).

Inactivating Som+ interneurons both increases CA1 PC activity and prevents learning. Impairments in memory storage could therefore result from a disruption of the hippocampal ensemble identity or population sparsity. The downstream mechanisms by which associative fear memories are impaired by CA1 Som+ interneuron inactivation can be addressed by studying CS-US convergence and plasticity in the amygdala. Som+ interneurons may also influence processing in the entorhinal cortex and medial septum through long-range inhibition (61). Furthermore, it remains to be determined whether US-driven excitation to CA1 contributes to long-term changes in CA1 PC activity after fear conditioning, such as place-cell remapping (62).

Our data suggest that inhibitory circuits can inhibit selected dendritic compartments to favor integration of one excitatory input pathway (proximal) over another (distal). GABA release localized to lacunosum-moleculare could accomplish this input segregation by inhibiting localized dendritic electrogenesis, which is required for propagating entorhinal excitatory inputs to drive output spikes and for inducing plasticity (16–18). This mechanism may also be present in sensory neocortex, where aversive footshocks activate cholinergic input to drive layer 1 interneurons in primary auditory and visual cortex (46). Layer 1 interneurons inhibit the apical tuft dendrites of layer 5 PCs, the primary output cell of the neocortex, at the site of multimodal association in layer 1 (55). Therefore the same mechanism we describe in CA1 could protect layer 5 PCs in primary sensory cortex from interference by the US, so that their outputs to the amygdala are driven by inputs to their basal dendrites reflecting local sensory processing, rather than inputs to tuft dendrites reflecting cross-modal influences.

These results suggest that dendrite-targeting Som+ interneurons provide US-evoked inhibition that is required for successful contextual fear learning. These interneurons are central to a mechanism by which the hippocampus processes contextual sensory inputs as a CS while excluding the sensory features of the US. Selective inhibitory control over integration of excitatory input pathways could be a general strategy for nervous systems to achieve separate processing channels in anatomically overlapping circuits, a process that could be flexibly controlled by a multitude of inhibitory interneuron types (22, 23) and neuromodulatory systems (63).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Sternson and P. Lee for proving PSEM89, A. Castro for programming assistance, E. Balough and M. Cloidt for scoring freezing, R. Field for preparing brain slices, J. Tsai for assistance with histology, T. Machado for assistance with ChAT-cre mice, W. Fischler for assistance with odor stimuli, and C. Lacefield for assistance with behavioral apparatus. M.L.-B. was supported by an Canadian Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council postgraduate scholarship. P.K. is an Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Predoctoral Fellow. M.A.K. is supported by NIMH K01MH099371, the Sackler Institute, and a NARSAD Young Investigator Award. R.H. is supported by NIH R37 MH068542, NIA R01 AG043688, New York State Stem Cell Science, and the Hope for Depression Research Foundation. B.V.Z. is supported by the Human Frontier Science Program. A.L. is supported by the Searle Scholars Program, the Human Frontier Science Program, and the McKnight Memory and Cognitive Disorders Award.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Fanselow MS. Learn Motiv. 1986;17:16–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fanselow MS. Anim Learn Behav. 1990;18:264–270. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maren S. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:897–931. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudy JW, Huff NC, Matus-Amat P. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanselow MS, Poulos AM. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:207–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JJ, Fanselow MS. Science. 1992;256:675–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1585183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young SL, Bohenek DL, Fanselow MS. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:19–29. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maren S, Fanselow MS. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7548–7564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07548.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frankland PW, et al. Hippocampus. 2004;14:557–569. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fanselow MS, DeCola JP, Young SL. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1993;19:121–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sah P, Faber ES, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:803–834. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed OJ, Mehta MR. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kesner RP. Learn Mem. 2007;14:771–781. doi: 10.1101/lm.688207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maren S, Fanselow MS. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1997;67:142–149. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golding NL, Staff NP, Spruston N. Nature. 2002;418:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nature00854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dudman JT, Tsay D, Siegelbaum SA. Neuron. 2007;56:866–879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi H, Magee JC. Neuron. 2009;62:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones MW, Wilson MA. PLOS Biol. 2005;3:e402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris KD, Hirase H, Leinekugel X, Henze DA, Buzsáki G. Neuron. 2001;32:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu W, et al. Neuron. 2012;73:990–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freund TF, Buzsáki G. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klausberger T, Somogyi P. Science. 2008;321:53–57. doi: 10.1126/science.1149381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Losonczy A, Zemelman BV, Vaziri A, Magee JC. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:967–972. doi: 10.1038/nn.2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovett-Barron M, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:423–430. S1–S3. doi: 10.1038/nn.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royer S, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:769–775. doi: 10.1038/nn.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahoney WJ, Ayres JJB. Anim Learn Behav. 1976;4:357–362. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouton ME, Bolles RC. Anim Learn Behav. 1980;8:429–434. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaifosh P, Lovett-Barron M, Turi GF, Reardon TR, Losonczy A. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1182–1184. doi: 10.1038/nn.3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magnus CJ, et al. Science. 2011;333:1292–1296. doi: 10.1126/science.1206606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anagnostaras SG, Gale GD, Fanselow MS. Hippocampus. 2001;11:8–17. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2001)11:1<8::AID-HIPO1015>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goshen I, et al. Cell. 2011;147:678–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray AJ, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:297–299. doi: 10.1038/nn.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akerboom J, et al. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13819–13840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2601-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dombeck DA, Harvey CD, Tian L, Looger LL, Tank DW. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1433–1440. doi: 10.1038/nn.2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dombeck DA, Khabbaz AN, Collman F, Adelman TL, Tank DW. Neuron. 2007;56:43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herreras O, Solís JM, Muñoz MD, Martín del Río R, Lerma J. Brain Res. 1988;461:290–302. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khanna S. Neuroscience. 1997;77:713–721. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00456-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Funahashi M, He YF, Sugimoto T, Matsuo R. Brain Res. 1999;827:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vinogradova OS. Hippocampus. 2001;11:578–598. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawrence JJ, Statland JM, Grinspan ZM, McBain CJ. J Physiol. 2006;570:595–610. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.100875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leão RN, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1524–1530. doi: 10.1038/nn.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller SW, Groves PM. Physiol Behav. 1977;18:141–146. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herreras O, Solís JM, Herranz AS, del Río RM, Lerma J. Brain Res. 1988;461:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng F, Khanna S. Neuroscience. 2001;103:985–998. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Letzkus JJ, et al. Nature. 2011;480:331–335. doi: 10.1038/nature10674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Widmer H, Ferrigan L, Davies CH, Cobb SR. Hippocampus. 2006;16:617–628. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gale GD, Anagnostaras SG, Fanselow MS. Hippocampus. 2001;11:371–376. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dasari S, Gulledge AT. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:779–792. doi: 10.1152/jn.00686.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hasselmo ME. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:710–715. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calandreau L, Jaffard R, Desmedt A. Learn Mem. 2007;14:422–429. doi: 10.1101/lm.531407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen TW, et al. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hargreaves EL, Rao G, Lee I, Knierim JJ. Science. 2005;308:1792–1794. doi: 10.1126/science.1110449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang SJ, et al. Science. 2013;340:1232627. doi: 10.1126/science.1232627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palmer L, Murayama M, Larkum M. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 2012;6:26. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2012.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang F, et al. Nature. 2007;446:633–639. doi: 10.1038/nature05744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Romanski LM, LeDoux JE. Cereb Cortex. 1993;3:515–532. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.6.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lanuza E, Nader K, Ledoux JE. Neuroscience. 2004;125:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brankačk J, Buzsáki G. Brain Res. 1986;378:303–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burwell RD, Amaral DG. J Comp Neurol. 1998;398:179–205. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980824)398:2<179::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Melzer S, et al. Science. 2012;335:1506–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1217139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moita MA, Rosis S, Zhou Y, LeDoux JE, Blair HT. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7015–7023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5492-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bargmann CI. Bioessays. 2012;34:458–465. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.