Abstract

Optimal decision-making often requires exercising self-control. A growing fMRI literature has implicated the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) in successful self-control, but due to the limitations inherent in BOLD measures of brain activity, the neurocomputational role of this region has not been resolved. Here we exploit the high temporal resolution and whole-brain coverage of event-related potentials (ERPs) to test the hypothesis that dlPFC affects dietary self-control through two different mechanisms: attentional filtering and value modulation. Whereas attentional filtering of sensory input should occur early in the decision process, value modulation should occur later on, after the computation of stimulus values begins. Hungry human subjects were asked to make food choices while we measured neural activity using ERP in a natural condition, in which they responded freely and did not exhibit a tendency to regulate their diet, and in a self-control condition, in which they were given a financial incentive to lose weight. We then measured various neural markers associated with the attentional filtering and value modulation mechanisms across the decision period to test for changes in neural activity during the exercise of self-control. Consistent with the hypothesis, we found evidence for top-down attentional filtering early on in the decision period (150–200 ms poststimulus onset) as well as evidence for value modulation later in the process (450–650 ms poststimulus onset). We also found evidence that dlPFC plays a role in the deployment of both mechanisms.

Introduction

Optimal decision-making often requires foregoing attractive but ultimately inferior rewards in pursuit of more desirable goals. For example, to maintain a healthy weight one may choose an apple over a piece of chocolate cake. A growing human fMRI literature has implicated the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) in successful self-control in domains ranging from diet to savings (Miller and Cohen, 2001; McClure et al., 2004, 2007; Ochsner and Gross, 2005; Camus et al., 2009; Mansouri et al., 2009; Figner et al., 2010; Kober et al., 2010; Mitchell, 2011; Philiastides et al., 2011; Hutcherson et al., 2012). Unfortunately, due to the limitations inherent in BOLD measures of brain activity, the precise neurocomputational role of dlPFC has not been resolved.

There are two natural models of what this role might be. The first one is based on previous findings from decision neuroscience. There is a growing consensus that ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) encodes stimulus values that guide decisions at the time of choice (Kable and Glimcher, 2009; Rushworth et al., 2009; Rangel and Clithero, 2013). Given this, dlPFC could influence self-control by modulating the value signals computed in vmPFC so that they reflect more desirable attributes, such as the health of foods (Cho and Strafella, 2009; Hare et al., 2009, 2011; Baumgartner et al., 2011).

A second model comes from the perceptual, attention, and working memory literatures, which have found that the dlPFC is part of a large-scale attentional network that modulates early sensory responses (Kastner and Ungerleider, 2001; Yamasaki et al., 2002; Buschman and Miller, 2007; Zanto and Gazzaley, 2009; Zanto et al., 2010, 2011; Lennert and Martinez-Trujillo, 2011). This phenomenon, often called attentional filtering, could aid in self-control by reducing the neural processing devoted to distracting, goal-irrelevant items: for example, via suppression of perceptual responses when tempting foods are likely to be present.

A critical difference between these two accounts lies in their timing. If self-control reflects dynamic attentional filtering of sensory input, there should be differential activity associated with self-control success versus failure early in perceptual processing. In contrast, value modulation should occur during vmPFC value computations, starting ∼400 ms poststimulus onset (Harris et al., 2011).

Here we exploited the high temporal resolution and whole-brain coverage of event-related potentials to test the hypothesis that both mechanisms are at work in simple dietary self-control. Subjects were asked to make food choices while we measured neural activity using event-related potentials (ERPs) in a natural condition, where they responded freely without tending to regulate their diet, and in a self-control condition, in which they were given a financial incentive to lose weight. We then measured various markers associated with attentional filtering and value modulation across the decision process. We predicted that early sensory responses should reflect differential self-control success associated with attentional filtering, whereas changes in the value assigned to taste and health attributes should be visible later in the decision period. Furthermore, both mechanisms should be linked to dlPFC.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Thirty-two right-handed subjects (ages 18–40, 21 males) from the local Caltech community participated in the study. Two additional subjects participated in the first experimental session, but were excluded from further participation because their choices revealed unusual food preferences, or their choices were so noisy that we could not reject the hypothesis that they were deciding randomly. Four subjects completed all experimental sessions, but their data were excluded from further analysis because their reported hunger levels were inconsistent with the experimental instructions described below (three subjects), or their EEG data exhibited persistent artifact after the preprocessing step (one subject). Subjects provided written informed consent before participation. All procedures were approved by Caltech's Institutional Review Board.

Stimuli.

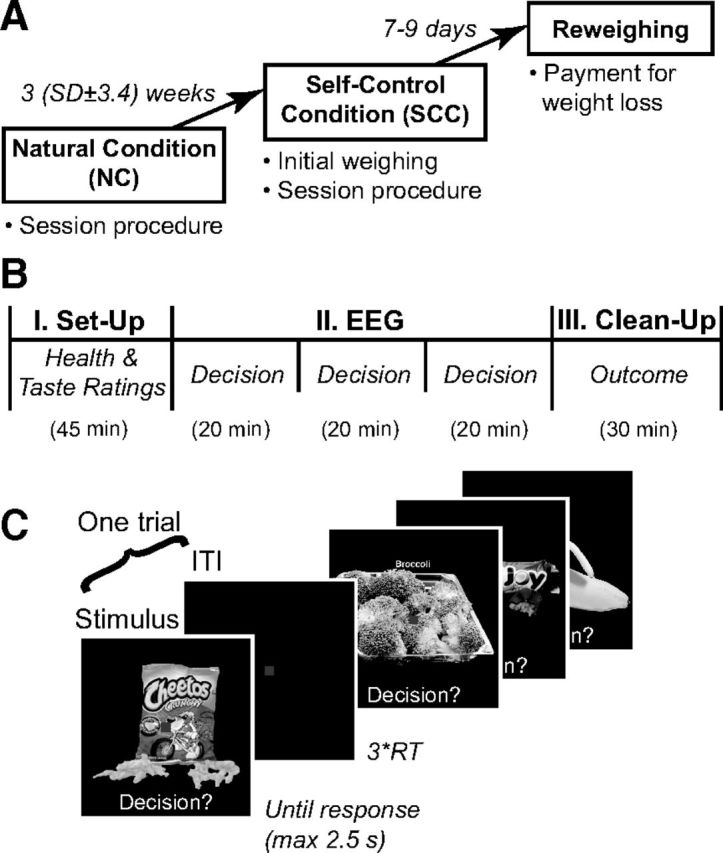

Subjects were presented with color pictures of 200 appetitive snack foods on a black background (Fig. 1; 576 × 432 pixels, 6.7° × 5° visual angle). The set of food items was selected based on prior behavioral data to satisfy the following properties in a typical subject: (1) span the full range of the tastiness and healthiness scales (described below), and (2) exhibit a low degree of correlation between the tastiness and healthiness attributes across items. The set of foods ranged from fruits and vegetables to chips and candy bars.

Figure 1.

Experimental procedures. A, Subjects made decisions about whether to eat snack foods varying in taste and health in two separate sessions: NC, in which they were instructed to respond naturally, and SCC, in which they were financially incentivized to lose weight to provide a motivation to exercise dietary self-control. Adherence to the weight loss incentive was measured in a separate final behavioral session. B, Procedure for each EEG session. In Part I, subjects rated each food on taste and health. In Part II, subjects decided whether or not they would like to eat each food at the end of the experiment while their EEG responses were recorded. In Part III, the choice made by the subject in a randomly selected trial was implemented. C, Sample stimuli and screens from the decision-making task.

Procedure.

The task consisted of two electroencephalography (EEG) experimental sessions, followed by a short behavioral session (Fig. 1A). For reasons that will become obvious below, we refer to the first EEG session as the natural condition (NC), and to the second EEG session as the self-control condition (SCC).

Subjects were asked to fast for at least 2 h before the experiment. We monitored compliance through self-reported hunger ratings on a five-point scale (1 = “not at all hungry” to 5 = “very hungry”) at the beginning of each session. A rating of 1 or 2 in either session was preselected as a criterion for exclusion from data analysis. Figure 1B describes the timing of events within each of the two EEG sessions. First, subjects provided tastiness and healthiness ratings for each of the 200 foods using a four-point scale (1 = Strong-No, 2 = Weak-No, 3 = Weak-Yes, 4 = Strong-Yes). On each trial, a food picture was displayed onscreen until the subject responded. Subjects entered their rating through a button press, with left-to-right order counterbalanced across subjects and sessions. The two types of ratings were blocked, with order counterbalanced across subjects. These ratings measure subjects' perceptions about how the taste and health attributes apply to each food, on each experimental session, and independently of the choices that they make later in the task.

Second, subjects performed a simple decision-making task, during which EEG recordings were made. As shown in Figure 1C, on every trial they were shown one food and had to decide whether or not they wanted to eat it at the end of the experiment. Subjects again entered their responses using a four-point scale (1 = Strong-No, 2 = Weak-No, 3 = Weak-Yes, 4 = Strong-Yes). This allowed us to simultaneously measure their choice (yes/no) and the strength of their preference (strong/weak). Subjects cared about these choices because they knew that at the end of each of the two EEG sessions they would be required to stay in the laboratory for 30 min, and that during that time, the only thing that they would be allowed to eat would be what they chose in a randomly selected trial. There were three runs of 200 trials each, with the foods presented in random order once per run, for a total of 600 trials. Each image was shown until subject response (maximum 2.5 s). Subjects were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible, and completed a short practice block before the actual experiment. Median reaction time (RT) was calculated cumulatively during each run, and the duration of the intertrial interval (ITI) was iteratively adjusted to 3 × median(RT) to ensure that all decision-making computations were completed before the start of the next trial. Runs were subdivided into short blocks with intervening self-paced breaks. During the decision task, subjects were asked to maintain central fixation and minimize eye movements and blinks. Their performance was monitored with the recording equipment. The three runs were separated by 10 min breaks.

Third, a food was randomly chosen and the subject's choice for that food was implemented. In particular, the subject had to eat at least three bites of the selected item if he responded Strong- or Weak-Yes on two or more of the three presentations of the item, but was not given anything to eat if he responded Strong- or Weak-No on the majority of the trials for that item. Subjects were required to stay in the lab for 30 min regardless of the outcome.

The key difference between the two sessions was that subjects responded “naturally” during the NC session, but were financially incentivized to lose weight during the SCC session. In particular, at the beginning of the SCC session subjects were weighed using a Health-o-meter Professional 349KLX digital medical scale (Pelstar LLC) while wearing a medical gown, and were told that they would be reweighed 7–9 d later when they returned to the lab for a final behavioral session. Reweighing was scheduled for the same time of day as the SCC session to account for daily fluctuations in weight. Subjects received a $100 bonus for losing 0.25% of the initial weight, up to 1 pound, but only $50 for losing >1 pound, and no bonus for weight gain. These incentives were chosen to induce subjects to exercise self-control during the SCC session choice task, while targeting a small weight loss during the rest of the week to discourage unhealthy dietary behaviors. We emphasize that the intervention itself was not of experimental interest, and was added simply to provide a strong incentive for exercising self-control during the SCC choices.

The NC and SCC sessions were separated by several weeks. We chose not to counterbalance the order of the two sessions across subjects, because it was unclear whether exposure to the self-control incentive would have long-lasting effects on behavior. However, although order and practice effects might have influenced the level of expertise with the task, and thus reaction times and consistency in choices, they are unlikely to have contaminated the analysis strategy described below. In particular, as described below, most analyses involve comparisons only within trials of the SCC, or conjunctions between NC and SCC trials, which are not confounded by the presence of putative practice effects.

EEG data acquisition and preprocessing.

EEG data were collected using a 128-channel HydroCel Geodesic Sensor Net (Electrical Geodesics) with AgCl-plated electrodes. Evoked brain potentials were digitized continuously at 500 Hz, and referenced to vertex electrode Cz. Online filters consisted of a 200 Hz low-pass Bessel filter and a 0.1 Hz high-pass hardware filter. Impedances were kept <50 kΩ, with adjustments during the 10 min breaks between runs. Following each session, sensor positions were digitized using the Geodesic Photogrammetry System.

Data preprocessing was performed offline using the EEGLAB toolbox for Matlab (MathWorks; Delorme and Makeig, 2004). Data were re-referenced to an average reference and high-pass-filtered at 1 Hz using a two-way least-squares FIR filter to remove slow voltage drifts. Epochs of 2300 ms time-locked to stimulus onset (100 ms pre-, 2200 ms post-) were extracted.

Traditional artifact removal techniques based on rejecting trials are suboptimal for our datasets due to the unequal number of trials per condition. Given this, we identified and removed experimental artifacts using independent components analysis, implemented via second-order blind identification (SOBI; Belouchrani et al., 1997; Tang et al., 2005). Like other blind source separation algorithms, SOBI enables the effective identification of artifactual components, which can be removed while leaving the overall number of trials in each condition intact (Tang et al., 2005). Specifically, SOBI linearly “unmixes” the EEG data into a sum of temporally correlated and spatially fixed components, which can be classified as artifactual or nonartifactual based on their power spectra, scalp topographies, and activity. Task-related nonartifactual components are characterized by clear stimulus- or response-locking and meaningful scalp topography, whereas artifactual components reflect blinks, eye movement, muscle activity, sensor noise, and slow voltage drifts (Harris et al., 2011, their Fig. 3 shows a visualization of this artifact removal procedure). By projecting only nonartifactual components back onto the scalp, it is possible to obtain artifact-corrected brain signals (Jung et al., 2000). Following artifact removal, a stimulus-locked dataset was constructed with epochs of 1100 ms (100 ms pre- to 1000 ms poststimulus onset), baseline-corrected to the prestimulus period.

Figure 3.

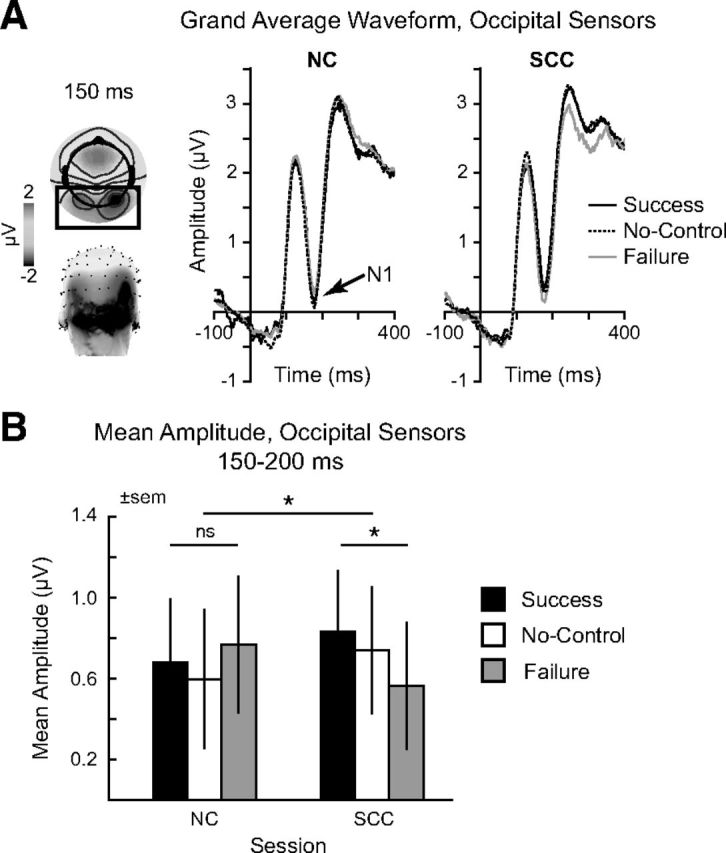

Analysis of N1 responses associated with attentional filtering. A, Left, Scalp distribution of evoked potentials at 150 ms, revealing strong responses over occipital sensors (black box). Right, Grand average waveforms at occipital sensors for self-control success (black), noncontrol (dashed), and self-control failure (gray) in NC and SCC sessions, displaying the visual N1 deflection at ∼170 ms poststimulus onset. B, Mean evoked amplitude (μV) for self-control success (black), noncontrol (white), and self-control failure (gray) at occipital sensors from 150 to 200 ms in the NC versus SCC session. Error bars reflect SEM. *p < 0.05.

EEG: self-control success versus failure analysis.

The goal of this analysis was to identify sensors and time windows that, during the SCC, exhibited differential activity for trials involving self-control successes and failures. To do this we divided the trials of the SCC session into three types: (1) successful self-control trials, in which subjects responded Yes to healthy but disliked foods, or No to liked but unhealthy foods; (2) failed self-control trials, in which subjects responded No to healthy-disliked foods or Yes to liked-unhealthy foods; and (3) no-control trials that did not require self-control, involving healthy-liked or unhealthy-disliked items. For the purpose of this analysis, yes and no responses were aggregated across strong and weak levels. We then computed an averaged ERP response for each subject and sensor over nonoverlapping 50 ms windows, from 100 to 1000 ms, separately for successful and failed self-control trials. This led to 128 sensor × 18 time window maps for both types of trials, which were then compared using a two-tailed paired t test.

Given the large number of statistical tests produced by the analyses described above and below, it was necessary to correct for multiple comparisons. Multiple-comparison corrections were implemented using permutation tests (Lage-Castellanos et al., 2010). To compare self-control success and failure, an approximate permutation test was computed by reshuffling the condition labels 1000 times to obtain an empirical distribution of t values, to which the actual t values were then compared. The number of statistical comparisons was further limited by carrying out this analysis starting at 100 ms poststimulus onset, the earliest latency at which visual evoked potentials are reliably reported. The same comment applies to the regression analyses described below.

EEG: phase-locking analysis.

The goal of this analysis was to test whether there was increased phase locking in the alpha range (8–12 Hz) between anterior and posterior sensors during successful self-control trials in the SCC. Current source density (CSD) estimates of the original vertex-referenced ERP data were computed using the CSD Toolbox for Matlab (MathWorks; Kayser and Tenke, 2006). The CSD transform produces reference-free data, minimizing spurious changes in phase coherence due to the use of an average reference. Additionally, due to its lower sensitivity to deep cortical sources, this measure is less influenced by artifactual volume-conducted signals.

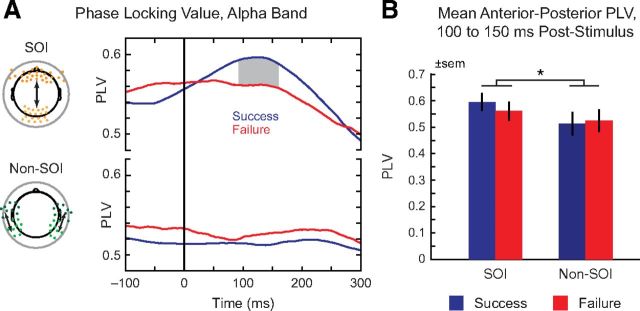

Predefined sets of sensors covering frontal and occipital scalp regions were used as anterior and posterior sensors of interest (SOIs; see Fig. 5A, left). Time-frequency analyses were performed using the FieldTrip software package (Oostenveld et al., 2011). ERP data were averaged across each SOI and filtered in the alpha band (8–12 Hz) via convolution with complex Morlet wavelets (family ratio: f0/σf = 7) and filter order of 400 ms. Phase-locking values (PLVs) were computed by measuring the intertrial variability of the phase difference at each time (Lachaux et al., 1999). The resulting PLVs are bounded between 0 and 1, with highly consistent phase differences yielding a PLV close to 1, and random phase differences yielding a PLV close to 0. Because previous analyses have found that frontal-occipital phase-locking associated with attentional modulation precedes the earliest cortical evoked potentials (Zanto et al., 2010, 2011), our PLV analysis focused on the window from 100 ms pre- to 300 ms poststimulus onset.

Figure 5.

Phase-locking value analysis. A, Phase-locking values, alpha band (8–12 Hz). Left: Sensor positions of frontal and occipital SOIs (orange) and control non-SOI sensors (green). Right, PLV from −100 to 300 ms after stimulus onset for self-control success (blue) and failure (red). Gray shading denotes significant differences surviving permutation correction. B, Comparison of mean anterior–posterior PLV for frontal-occipital SOIs versus control non-SOI sensors, 100–150 ms after stimulus onset. Error bars reflect SEM. *p ≤ 0.05.

EEG: regression analysis of stimulus values.

The goal of this analysis was to identify sensors and time windows in which neural activity at the time of decision was correlated with the stimulus value of the foods, as measured by the subject's decision. Evoked data for each trial between 100 and 1000 ms poststimulus onset were summed across 50 ms nonoverlapping windows for each sensor. For each subject, the EEG responses for each of the 128 sensors × 18 time windows were then entered into a linear regression model of the form:

where ysensor,time consists of trial-by-trial data (in μV) for a particular sensor and time window, and β0 is the average activity in the sensor. The Decision covariate measures the decision value (1 = Strong-No to 4 = Strong-Yes). The Arousal covariate measures the strength of preference regardless of valence (0 for Weak-No or Weak-Yes, 1 for Strong-No or Strong-Yes). We included the latter covariate to take out the components of the signal that are related to arousal (Litt et al., 2011), which increases the statistical power of the linear model to identify value related activity. The linear regressor analysis generated a map of estimated regression coefficients (i.e., beta map) for every sensor, time window, and subject. We aggregated these maps into mixed-effect group estimates by computing one-sample t tests versus zero across subjects for each sensor and time window. This led to output significant maps that identify sensors and windows in which evoked responses increase with stimulus value. Results were corrected for multiple comparisons using exact permutation tests, performed by calculating the linear models for every possible permutation of the four condition labels (4! = 24). Observed t values were compared with this empirical distribution, with those greater than or equal to the highest t values, and less than or equal to the lowest t values, considered as surviving multiple comparisons correction with a threshold of p = 1/24 = 0.04 (one-tailed). Thus, given the small number of permutations, in practice the observed data had to fall at the extreme end of the permutation distribution to survive multiple-comparisons correction. These analyses were performed separately for the SC and NCC trials.

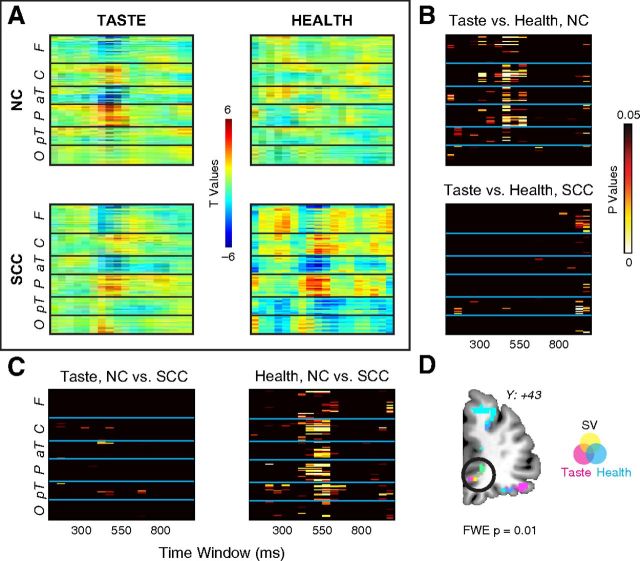

EEG: regression analysis of health and taste ratings.

The goal of this analysis was to identify sensors and time windows in which evoked neural responses were linearly responsive to either the taste or the health ratings. The analyses were performed separately for the SC and NCC trials. The analysis is almost identical to the previous one, except that now the linear regression model is given by:

where the Health and Taste covariates correspond to the subject's health and taste ratings entered in each session. The resulting beta maps were then compared using various paired t tests. Permutation tests were used to correct for multiple comparisons, randomly shuffling the assignment of each subject's beta value maps to the two conditions (taste and health), and then calculating the resulting distribution of the t statistics (1000 permutations).

EEG: Bayesian source reconstruction.

The goal of this analysis was to localize the regions associated with the significant activity identified in the previous EEG analyses at the sensor level. Distributed source reconstructions were performed using SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, Institute of Neurology, London, UK).

The neural generators for any given waveform can be modeled as a combination of hundreds of small dipolar patches distributed across the cortical sheet. In our analysis, we first computed source reconstructions across the entire trial, −100 to 1000 ms from stimulus onset, which produces models of activity in all potential sources spanning this entire period. Following this large-scale reconstruction, sources were modeled for specific time windows of interest (WOIs) defined from the mixed-effects ERP regression analysis. Thus, for any given time window (e.g., 150–200 ms), we could identify putative neural sources arising from the pattern of electrical potentials recorded at the scalp.

To pinpoint generators associated with specific cognitive effects, we used a “difference of localizations” approach in some analyses, and a “localization of differences” approach in others (Henson et al., 2007). These two analyses differ in the types of inferences being drawn. Specifically, a “localization of differences” (LoD) assumes that there exists a set of neural sources that represent different levels of the psychological variable of interest; for example, brain regions whose activity is correlated with stimulus values. Yet, because this analysis is designed to find sources representing all conditions, it cannot address the question of whether different conditions (e.g., self-control success and failure) are associated with spatially distinct brain networks. In this case, the more apt comparison is a “difference of localizations” (DoL), in which neural generators for the conditions are modeled separately, and the respective source estimates are then compared statistically.

Given this, to examine how self-control success and failure differentially recruit various brain networks, we used a DoL approach. In each subject, separate source reconstructions were performed for the waveforms associated with self-control success and failure. These reconstructions were then entered into a paired t test analysis across subjects, producing statistical maps identifying sources differentially associated with self-control success or failure (Table 1).

Table 1.

Peak MNI coordinates; self-control success versus failure SCC, 150–200 ms

| No. Voxels | Side | Peak MNI coordinates | t | MNI coordinate region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-control success > self-control failure | ||||||

| 402 | L | −32 | −20 | 20 | 11.6 | Insula |

| −30 | −26 | 14 | 11.6 | |||

| −40 | −26 | 8 | 11.3 | |||

| 377 | R | 34 | −16 | 18 | 11.1 | Insula* |

| 106 | R | 42 | 20 | −16 | 9.72 | Inferior frontal gyrus* |

| 42 | L | −40 | 20 | −16 | 8.10 | Inferior frontal gyrus |

| 184 | R | 40 | 50 | 16 | 8.04 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex* |

| 38 | 40 | 34 | 7.93 | Middle frontal gyrus | ||

| 38 | 46 | 24 | 7.72 | |||

| 187 | L | −36 | 42 | 28 | 7.95 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| −42 | 46 | 16 | 7.93 | Middle frontal gyrus | ||

| −34 | 54 | 14 | 6.93 | |||

| Self-control failure > self-control success | ||||||

| 86 | L | −40 | −42 | 50 | −6.55 | Inferior parietal lobe |

| −26 | −40 | 48 | −6.67 | |||

| −30 | −38 | 36 | −6.84 | |||

| 144 | R | 42 | −40 | 42 | −6.55 | Inferior parietal lobe |

| 36 | −40 | 54 | −6.64 | Intraparietal sulcus | ||

| 28 | −34 | 38 | −6.70 | |||

| 108 | L | −60 | −38 | −14 | −6.55 | Middle temporal gyrus |

| −64 | −30 | −10 | −6.59 | Inferior temporal gyrus | ||

| −60 | −32 | −22 | −6.65 | |||

| 171 | R | 44 | −32 | −2 | −6.51 | Middle temporal gyrus |

| 58 | −34 | −20 | −6.54 | |||

| 58 | −40 | −10 | −6.55 | |||

| 105 | R | 32 | −30 | −8 | −6.49 | Hippocampus |

| 24 | −18 | −22 | −6.50 | Parahippocampal gyrus | ||

| 18 | 0 | −12 | −6.51 | |||

| 60 | R | 54 | −34 | 8 | −6.49 | Superior temporal gyrus |

| 54 | −42 | 10 | −6.54 | Temporoparietal junction | ||

| 64 | −28 | 0 | −6.85 | |||

Clusters surviving FWE-corrected threshold p < 0.01 (t ≥ 6.49) and cluster size threshold k = 5. For this and all other tables, bold type indicates a cluster-level maximum, with separate (>8 mm) maxima listed in plain type. Because of the relatively low spatial resolution of EEG reconstruction, the source regions listed here do not precisely correspond to the coordinates, but rather reflect the general location of source activity within the specified cluster.

*Clusters used as ROIs in causal connectivity analysis.

In contrast, for our analyses of stimulus values, and of taste and health ratings, we relied on a LoD approach. The aim of source reconstruction here was to find regions showing a parametrically varying representation of these stimulus attributes, in line with subjects' decisions and ratings. To do so, we performed source reconstructions of the linear ordering from Strong-No to Strong-Yes. Difference waveforms were computed in each subject by multiplying the average waveforms for each of the conditions (Strong-No to Strong-Yes) by the corresponding weights (−3, −1, +1, +3), and then summing across all weighted averages. This set of weights is commonly used to test for linear trends, weighting the data to find monotonically increasing responses with increasing ratings. Following source reconstruction, source estimates across subjects were entered into an F test, allowing us to identify neural sources associated with parametric responses (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Peak MNI coordinates; stimulus value NC, 400–500 ms

| No. Voxels | Side | Peak MNI coordinates | F | MNI coordinate region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 240 | L | −22 | 28 | −22 | 109.8 | Inferior frontal gyrus |

| −28 | 0 | −16 | 60.8 | Orbitofrontal cortex | ||

| 512 | R | 18 | 26 | −22 | 99.0 | Inferior frontal gyrus |

| 34 | −2 | −26 | 69.7 | Orbitofrontal cortex | ||

| 26 | 16 | −16 | 65.1 | |||

| 210 | R | 26 | −34 | −10 | 90.0 | Parahippocampal cortex |

| 6 | −44 | 12 | 67.9 | Retrosplenial cortex | ||

| 8 | −36 | 6 | 67.9 | Posterior cingulate cortex | ||

| 172 | R | 38 | 10 | 26 | 81.8 | Inferior frontal gyrus |

| 46 | 0 | 38 | 66.1 | Middle frontal gyrus | ||

| 34 | 0 | 28 | 60.2 | |||

| 21 | R | 40 | −20 | 20 | 79.0 | Insula |

| 36 | −12 | 18 | 56.4 | |||

| 40 | −28 | 22 | 50.0 | |||

| 177 | R | 52 | −34 | 12 | 78.8 | Superior temporal gyrus |

| 48 | −24 | −2 | 67.3 | |||

| 60 | −30 | 8 | 64.0 | |||

| 85 | R | 48 | −68 | 34 | 76.3 | Angular gyrus |

| 40 | −64 | 34 | 65.7 | Inferior parietal lobe | ||

| 38 | −52 | 20 | 60.6 | |||

| 69 | L | −2 | 14 | 12 | 75.8 | Cingulate cortex |

| −20 | −50 | 4 | 61.8 | Parahippocampal gyrus | ||

| −4 | −26 | 10 | 56.8 | |||

| 51 | L | −4 | 22 | 14 | 73.6 | Anterior cingulate cortex |

| −10 | 4 | 42 | 59.0 | |||

| −6 | 20 | 24 | 53.13 | |||

| 184 | L | −30 | −84 | 32 | 71.1 | Superior occipital gyrus |

| −26 | −64 | 30 | 67.5 | Parietal lobe | ||

| −22 | −60 | 40 | 59.8 | |||

| 351 | R | 34 | −50 | 34 | 70.3 | Superior parietal lobule |

| 32 | −60 | 32 | 68.7 | Precuneus | ||

| 32 | −78 | 26 | 62.7 | |||

| 146 | L | −50 | −8 | −44 | 69.6 | Inferior temporal gyrus |

| −38 | −22 | −20 | 57.9 | Parahippocampal gyrus | ||

| −38 | −8 | −40 | 51.2 | |||

| 73 | L | −10 | −36 | 60 | 69.3 | Paracentral lobule |

| −6 | −46 | 70 | 65.2 | Precuneus | ||

| 51 | R | 6 | 26 | 22 | 68.9 | Anterior cingulate cortex |

| 4 | 18 | 24 | 61.7 | Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | ||

| 6 | 34 | 12 | 50.6 | |||

| 187 | L | −34 | −50 | 58 | 68.6 | Parietal lobe |

| −24 | −36 | 54 | 57.4 | |||

| 52 | L | −22 | 48 | 20 | 64.2 | Superior frontal gyrus |

| 77 | L | −40 | 8 | 32 | 61.4 | Inferior frontal gyrus |

| −44 | 36 | 14 | 53.2 | |||

| −44 | 18 | 28 | 45.6 | |||

| 42 | L | −14 | −30 | 62 | 57.8 | Paracentral lobule |

| 6 | R | 4 | −40 | 22 | 55.4 | Posterior cingulate cortex |

| 13 | L | −32 | 48 | 28 | 55.0 | Middle frontal gyrus |

| −36 | 48 | 20 | 52.0 | |||

| 29 | L | −58 | −26 | −10 | 54.6 | Middle temporal gyrus |

| −58 | −18 | −12 | 52.1 | |||

| −52 | −28 | −4 | 49.0 | |||

| 6 | L | −48 | −72 | −8 | 54.5 | Inferior temporal lobe |

| 11 | R | 0 | 14 | 18 | 52.4 | Cingulate cortex |

| 0 | 6 | 20 | 52.0 | |||

| 13 | R | 52 | −48 | −24 | 52.3 | Fusiform gyrus |

| 6 | L | −44 | −64 | 40 | 51.0 | Inferior parietal lobule |

| 5 | L | −38 | −90 | −2 | 48.0 | Middle occipital gyrus |

| 5 | L | −34 | −38 | 44 | 46.1 | Parietal lobe |

Clusters surviving FWE-corrected threshold p < 0.01 (F = 45.2) and cluster size threshold k = 5.

Table 3.

Peak MNI coordinates; stimulus value SCC, 450–650 ms

| No. Voxels | Side | Peak MNI coordinates | F | MNI coordinate region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 136 | R | 12 | 26 | −16 | 90.8 | Ventromedial prefrontal cortex* |

| 14 | 40 | 0 | 82.8 | Anterior cingulate cortex | ||

| 10 | 36 | 10 | 77.7 | Medial orbitofrontal cortex | ||

| 183 | L | −26 | 16 | −10 | 89.2 | Inferior frontal gyrus |

| −30 | 28 | −20 | 76.2 | Insula | ||

| −32 | −2 | −16 | 54.1 | |||

| 108 | R | 62 | −24 | −10 | 84.1 | Middle temporal gyrus |

| 66 | −28 | −18 | 76.9 | Inferior temporal gyrus | ||

| 58 | −30 | −16 | 73.2 | |||

| 183 | R | 26 | −28 | −14 | 79.3 | Parahippocampal gyrus |

| 16 | 0 | −12 | 74.4 | Limbic lobe | ||

| 34 | −32 | −14 | 72.7 | |||

| 84 | L | −62 | −22 | −8 | 71.6 | Middle temporal gyrus |

| −60 | −28 | −20 | 58.6 | Inferior temporal gyrus | ||

| 89 | R | 20 | 30 | −20 | 67.1 | Inferior frontal gyrus |

| 28 | 16 | −12 | 49.5 | Orbitofrontal gyrus | ||

| 21 | R | 16 | −38 | 46 | 62.8 | Parietal lobe |

| 68 | L | −40 | 4 | −6 | 60.0 | Insula |

| −42 | −6 | −16 | 55.3 | Superior temporal gyrus | ||

| −48 | −6 | −22 | 49.9 | |||

| 12 | 0 | −34 | 24 | 58.1 | Posterior cingulate | |

| 0 | −38 | 16 | 55.4 | |||

| 13 | L | −4 | −24 | 34 | 57.8 | Posterior cingulate |

| 10 | 0 | −32 | 10 | 57.3 | Posterior cingulate | |

| 39 | L | −40 | −88 | 0 | 55.7 | Middle occipital gyrus |

| −38 | −80 | −4 | 46.5 | |||

| 55 | R | 48 | 2 | −16 | 55.3 | Superior temporal gyrus |

| 46 | −4 | −22 | 51.1 | Superior temporal pole | ||

| 12 | R | 32 | 54 | 2 | 55.0 | Middle frontal gyrus |

| 13 | R | 4 | −2 | 30 | 54.2 | Anterior cingulate |

| 4 | 6 | 28 | 50.3 | |||

| 6 | 18 | 26 | 49.2 | |||

| 5 | L | −16 | −74 | 42 | 51.6 | Superior parietal cortex |

| 5 | L | −14 | −72 | 36 | 50.2 | Precuneus |

| 7 | R | 30 | −90 | 2 | 49.0 | Middle occipital gyrus |

| 5 | L | −34 | 56 | 6 | 48.4 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| 12 | L | −24 | −32 | 68 | 48.0 | Sensorimotor cortex |

| 17 | R | 6 | 52 | 26 | 48.0 | Superior medial frontal gyrus |

| 17 | L | −26 | 8 | −36 | 46.9 | Temporal pole |

| −28 | 2 | −30 | 46.6 | Superior temporal gyrus | ||

| 5 | R | 46 | −6 | −42 | 46.4 | Inferior temporal lobe |

Clusters surviving FWE-corrected threshold p < 0.01 (F = 44.9) and cluster size threshold k = 5.

*Cluster used to derive ROI in causal connectivity analysis.

In all reconstructions, source localization was performed via an empirical Bayesian algorithm (Friston et al., 2008) that constrains the underlying sources to provide a common explanation for evoked responses in all subjects (Litvak and Friston, 2008). In contrast to traditional dipole fitting, this approach does not require a priori assumptions about the number of sources or their spatial locations. Subjects were entered into the same source space using a “canonical mesh” based on SPM's template head model derived from the MNI brain. Individual subjects' sensor and fiducial coordinates, acquired with the Geodesic Photogrammetry System, were coregistered with the MRI coordinate system and matched to the cortical mesh using an iterative alignment algorithm. The source space was modeled using a boundary element model.

All reconstructions were then entered into statistical analyses (t and F tests) to identify statistically significant source estimates across individuals. Results were visualized in terms of maximal intensity projection (MIP) of the corresponding statistic. All statistics were corrected for multiple comparisons using a stringent familywise-error (FWE) corrected threshold of p < 0.01. As displayed in Tables 1–3, our analysis focused on cortical generators, because subcortical structures generally lack the coherent neural organization of pyramidal cortical cells and are unlikely to make a major contribution to potentials recorded at the scalp (Cohen et al., 2011).

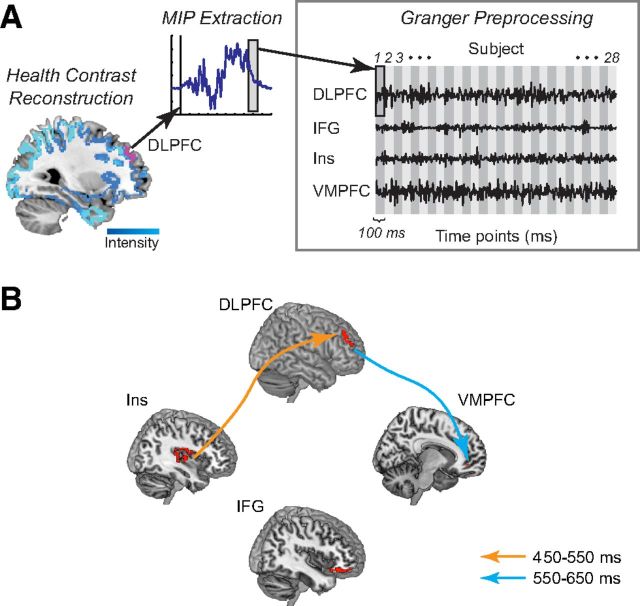

EEG: Granger connectivity analysis.

The goal of this analysis was to test for modulatory influence from dlPFC to vmPFC during the time windows associated with the computation of stimulus values, as identified by the previous analyses. Granger causality analysis was performed using the Granger Causal Connectivity Analysis toolbox (GCCA) for Matlab (MathWorks; Seth, 2010).

Given our interest in how regions associated with successful self-control modulate stimulus value signals, we chose the regions of interest (ROIs) for the GCCA based on the results from previous analyses. In particular, the ROIs were defined to be sources that exhibited greater responses in successful over failed self-control trials over the conjunction of time windows showing significant differential effects (150–200 ms, 400–450 ms, and 500–550 ms poststimulus onset), and using a liberal threshold of p < 0.005 (uncorrected) to be inclusive. This conjunction analysis identified three bilateral ROIs: dlPFC, insula, and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC). Additionally, a vmPFC ROI was defined from the conjunction of stimulus value sources surviving FWE-corrected p < 0.01, from 250 to 350 ms and 450–650 ms.

The GCCA proceeded in several steps, all of them applied to data for the SCC only. First, we performed a Bayesian source reconstruction of the linear contrast for health ratings (least to most healthy) over the time window to generate a dipole intensity map for each subject (see Fig. 8A, left). We focused on this contrast because the previous results showed an increased weighting on health in both choices and the vmPFC value signals. We focused on this time window because it was identified by previous analyses as the period over which stimulus values were computed. Second, we used this map to forward-model the projected average time course for each ROI and subject, averaged across hemispheres (see Fig. 8A, middle). Third, we applied several preprocessing steps on the time-series, so that they satisfied the assumptions required by GCCA. Preprocessing included linear detrending, subtraction of the temporal mean, and division by the temporal SD. Data across subjects was combined into one matrix treating each subject as a single realization of an underlying stochastic process, followed by subtraction of the ensemble mean and division by the ensemble SD. First-order differencing was applied to address covariance nonstationary. Augmented Dickey–Fuller and KPSS tests produced divergent results, providing no clear evidence regarding covariance stationarity. Because additional differencing necessary for convergence would make interpretation difficult, we considered first-order differencing sufficient to approximate the stationarity assumptions required by Granger causality. These steps produced the matrix of sources and data points used in Granger causal modeling (see Fig. 8A, right). Fourth, we estimated the GCCA model among the ROIs over the 450–650 ms window. The optimal model order selected using the Bayesian information criterion was 10, corresponding to a lag of 20 ms. Significance was assessed using a threshold of p = 0.01, Bonferroni-corrected. For all comparisons showing significant effects, the Durbin–Watson test found no significant correlation of the residuals, and the consistency test showed high consistency of the fitted model with the correlation structure of the data (>85%).

Figure 8.

Exploratory Granger causal connectivity analysis. Note that due to the coarse spatial resolution of the source reconstruction technique, the selected ROIs are not precise anatomical regions but rather represent broad divisions of cortex. A, Granger causal connectivity methodology. The linear response to healthiness (least to most healthy) was used as a surrogate for self-control. Left, Source reconstruction of the healthiness signal produced an intensity map for the modeled dipolar patches within each subject (shades of blue). Pink, dlPFC ROI from self-control success > failure. Middle, Time courses of the MIP for each dipole in each ROI were extracted and averaged, then selected for specified time windows (gray box). Right, For each ROI, data for each time window were concatenated across subjects and preprocessed (linear detrending, subtraction of temporal mean, subtraction of ensemble mean, first-order differencing) before being entered into Granger causal modeling. B, Model and causal connectivity for health contrast 450–650 ms after stimulus onset. All displayed connections are significant at a threshold of p = 0.01, Bonferroni-corrected.

Results

Subjects participated in two separate EEG sessions, each consisting of three separate parts (Fig. 1). First, subjects were shown pictures of 200 different snack foods, one at a time, and had to provide tastiness and healthiness ratings for each of them using a four-point scale (1 = Strong-No, 2 = Weak-No, 3 = Weak-Yes, 4 = Strong-Yes). These ratings provide measures of subjects' perceptions of the level of these attributes for each food in each session, independent of the subsequent choices. Second, subjects were shown pictures of the same foods, one at a time, and had to decide whether or not they wanted to eat them at the end of the experiment. They entered their decisions using the same four-point scale, which allowed us to simultaneously measure their choice (yes/no) and the strength of their preferences (strong/weak). Third, the choice made by the subject for a randomly selected food was implemented. See Materials and Methods for more details.

Critically, the two EEG sessions differed on the goals that subjects had when making the food choices. In the first session, which we refer to as the NC, subjects were asked to make food choices naturally. In the second condition, which we refer to as the SCC, subjects were given an incentive to exercise dietary self-control when making their choices. In particular, they were weighed at the beginning of the SCC session and were told that if they lost >0.25% of their body weight over the next week (up to a maximum of 1 pound), they would earn an additional $100. The weight-loss intervention was not of direct experimental interest, and was used only to induce subjects to exercise self-control reliably during the SCC choices. The order of the NC and SCC sessions was not counterbalanced because we were concerned that it might have a permanent impact on the choices made by subjects in the experiment. Although this design feature might have resulted in increased expertise and familiarity with the task during the SCC session, and thus more consistent decisions and faster responses, it did not contaminate the analyses described below (see Materials and Methods for details).

The analyses below are organized as follows. First, we analyzed the behavioral data, mainly with the goal of verifying that the weight-loss intervention was successful. Second, we used the ERP data to look for evidence of increased attentional filtering, early in the decision process, during successful self-control trials. Third, we used the ERP data to look for evidence of increased late value modulation during the SCC session, where subjects have an incentive to exercise self-control, in contrast to the NC session, where they do not.

Behavior: choice responses

We performed several analyses of the choice responses to verify that the weight-loss intervention increased self-control. First, as shown in Figure 2A, a comparison of behavior between the two conditions showed a significant shift from a majority of positive responses in the NC to a majority of negative responses in the SCC (χ2 = 3755.7, p ≈ 0). This is to be expected if individuals exercise self-control in large part by refusing tasty but unhealthy items, like candy or chips.

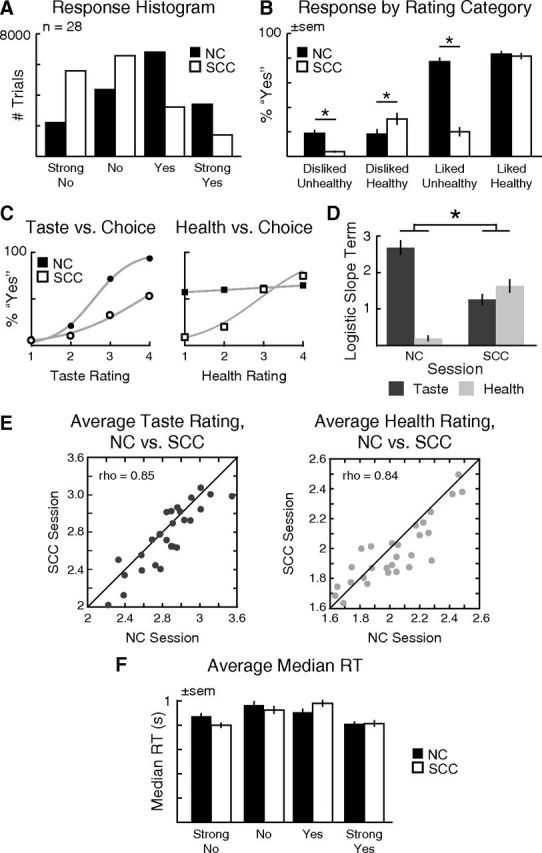

Figure 2.

Behavioral data. A, Histogram of responses for NC and SCC conditions. B, Responses for each session binned by rating category in terms of taste (liked or disliked) and health (healthy or unhealthy). C, Group average choices as a function of taste (left) and health (right) ratings. D, Average slope terms for a logistic regression of choice (yes/no) on taste and health ratings, separately for each subject and condition. E, Correlation of average taste (left) and health (right) ratings for the NC and SCC sessions. Each point denotes the average for one subject across all foods; 45° line is shown. F, Average median RTs by session. All error bars reflect SEM. *p < 0.05.

To investigate this further, we examined the effect of condition as a function of food type (Fig. 2B). In particular, we divided foods into four categories: disliked-unhealthy, disliked-healthy, liked-unhealthy, and liked-healthy. Note that self-control is required when individuals are shown liked-unhealthy or disliked-healthy foods, but not in the other two cases. We found that in the SCC subjects were more likely to reject unhealthy foods (Liked Unhealthy: t(27) = 11.1, p = 1.5 × 10−11; Disliked Unhealthy: t(27) = 4.83, p = 4.9 × 10−5) and to accept healthy foods that they disliked (t(27) = −2.36, p = 0.03). The effect was particularly large for the case of liked-unhealthy foods, like candy or chips, which again suggests that individuals exercised self-control in large part by refusing to eat these types of items.

Another way of looking at the extent to which individuals exercise self-control is to measure how their choices vary with the perceived health and taste attributes of the foods. To do this, we estimated a logistic regression of choice (yes/no) versus health and taste ratings, separately for each individual and condition, given the attribute ratings provided in each session. An increase in self-control involves an increase in the regression coefficient for the health rating and/or a decrease in the regression coefficient for taste. Figure 2C,D shows that during the NC, subjects' choices relied almost exclusively on taste, whereas in the SCC their decisions incorporated information about taste and health (condition × rating interaction: t(27) = 8.9, p = 1.5 × 10−9).

Behavior: changes in attribute ratings

The previous results show that individuals exercised self-control during the SCC both by increasing the weight that they gave to health, and by decreasing the weight that they gave to taste. However, subjects can also increase their self-control by changing their perception of the items (i.e., by viewing foods like candy as less healthy and tasty, and foods like broccoli as healthier and tastier), independently of how they are weighted. To investigate whether this additional self-control mechanism was at work, we computed mean taste and health ratings across foods for each individual and condition. As shown in Figure 2E, the ratings were very highly correlated across conditions (taste: Spearman ρ = 0.85, p < 10−8; health: Spearman ρ = 0.84, p < 10−8). Yet the average ratings were nonetheless significantly lower in the SCC session, as seen by the number of points clustered below the line of unity, although the magnitude of the effect was small (taste: t(27) = 3.19, p = 0.004; health: t(27) = 2.4, p = 0.03). Together with the previous results, this suggests that both mechanisms of self-control were at work, but that the change in attribute weighting plays a more important role.

Behavior: reaction times

With regards to reaction times, the two conditions showed similar measures of central tendency and variability (NC: median = 861 ms, SD = 316; SCC: median = 841 ms, SD = 313), though differences in the skew of the two distributions were significant, reflecting a heavier right tail in the first NC session (NC: skew = 1.64; SCC: skew = 1.54; t(27) = 2.03, p = 0.053). Likewise, the RTs for each decision type were similar across conditions (Fig. 2F), as shown by a two-way ANOVA (Condition × Decision), which revealed no significant main effect of session (F < 1). In contrast, the main effect of Decision was highly significant (F(3,78) = 21.9, p = 2.1 × 10−10), reflecting the inverted U-shaped function of median RT by Decision (quadratic contrast: F(1,78) = 64.5, p = 8.2 × 10−12). Additionally, the interaction of Condition × Decision was also significant (F(3,78) = 8.9, p = 3.7 × 10−5), due to the different skew in the distribution of reaction times between the NC and SCC conditions: whereas subjects were slowest to respond during Weak-No decisions in the NC, they shifted to longer reaction times during Weak-Yes in the SCC trials.

ERP and early attentional filtering: N1 responses and self-control

We next performed three tests of the hypothesis that increased self-control involves deployment of top-down attentional filtering early in the decision period. The first test is based on the properties of the N1 response. The second test is based on the idea that, under top-down attentional modulation, there should be more prefrontal activation during successful self-control trials. The third test is based on expected changes in phase locking between occipital and frontal sensors.

First, consider the test associated with the N1 response. This response is associated with a negative deflection that occurs at occipital electrodes ∼150–200 ms after stimulus onset, and is thought to reflect early stages of perceptual processing in extrastriate visual areas (Hopf et al., 2002). Importantly, the N1 amplitude increases with attention and working memory demands (Hillyard and Anllo-Vento, 1998; Rose et al., 2005; Zanto and Gazzaley, 2009), and is dramatically reduced in patients with prefrontal damage (Swick, 1998; Knight et al., 1999). This suggests the N1 response also reflects top-down inputs from frontal executive regions, and that it can be used as a marker of early top-down attentional filtering.

We hypothesized that, in our paradigm, attentional filtering would take the form of inhibition of early perceptual processing for potentially distracting, goal-irrelevant items, as part of a general attentional suppression when tempting foods may be present. The hypothesis can be tested as follows. Begin by dividing the trials of the SCC session into three types: (1) successful self-control trials, in which subjects responded Yes to healthy but disliked foods, or No to liked but unhealthy foods; (2) failed self-control trials, in which subjects responded No to healthy-disliked foods or Yes to liked-unhealthy foods; and (3) no-control trials that did not require self-control, involving healthy-liked or unhealthy-disliked items. The hypothesis then predicts that the amplitude of the N1 response should be most negative in failed self-control trials and least negative in successful self-control trials, with no-control trials in between. Furthermore, because attentional filtering is only required when there is an incentive for self-control, we hypothesized that this pattern would be present in the SCC, but not during the NC.

We performed the test in two steps. First, we verified that the N1 response was present in our dataset, regardless of the self-control condition. To do this, we computed the average ERP response over all occipital sensors, for SCC and NC trials separately. As shown in Figure 3A, we found a characteristic N1 ∼170 ms poststimulus in both cases (NC: M = 176 ms, SD = 11.6; SCC: M = 176 ms, SD = 13.3). Second, for every subject, trial type, and session we computed the mean amplitude between 150 and 200 ms poststimulus. We found a clear linear ordering of amplitudes (Fig. 3B) associated with self-control success, noncontrol, and self-control failure in the SCC, but not in the NC (Session × Condition interaction: F(2,54) = 5.97, p = 0.005; main effects, n.s.). This was confirmed by a significant linear contrast for the SCC (F(1,54) = 10.3, p = 0.002), but not for the NC (F(1,54) = 1.14, p = 0.29).

ERP and early attentional filtering: stronger dlPFC activity during successful self-control

Next, we hypothesized that increased top-down attentional modulation would be associated with stronger dlPFC activity early on during successful self-control trials, as compared with failed self-control trials. The hypothesis is based on previous studies, which have shown dynamic fluctuations in top-down attentional filtering by dlPFC during perceptual and working memory tasks (Zanto and Gazzaley, 2009; Lennert and Martinez-Trujillo, 2011; Suzuki and Gottlieb, 2013).

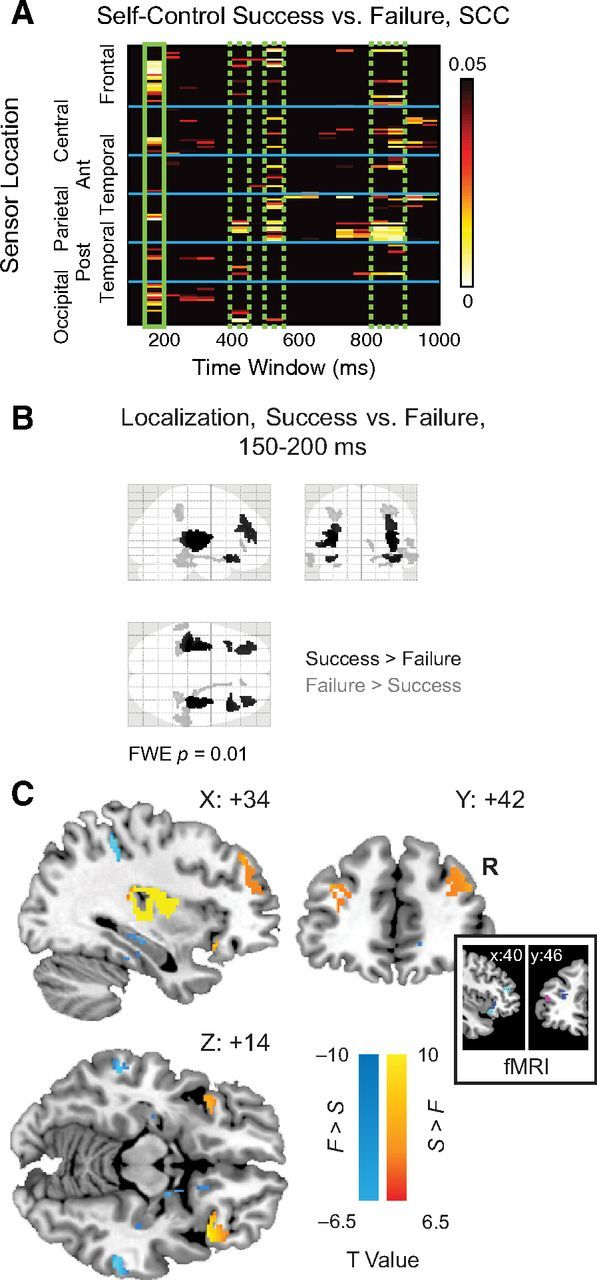

We tested this hypothesis in two steps. First, we used two-tailed paired t tests to compare the responses in each sensor between successful and failed self-control trials, using 50 ms windows, from 100 to 1000 ms after stimulus onset. We corrected for multiple comparisons using permutation tests. As shown in Figure 4A, we found multiple sensors and time windows at which the responses in successful self-control trials were significantly different from those in failed self-control trials. The earliest differential response occurred from 150 to 200 ms in frontal and occipital sensors. Second, we used distributed Bayesian source reconstruction (Friston et al., 2008; Litvak and Friston, 2008) to localize, separately, cortical regions associated with significant responses during successful and failed self-control trials. We then used a “difference of localizations” approach (Henson et al., 2007), to identify regions that exhibited a stronger response in successful than failed self-control trials. In this approach, separate localizations are performed for the two conditions of interest, and then the two localizations are contrasted statistically. In particular, we compared the separate source reconstructions for self-control success and failure trials over the 150–200 ms poststimulus interval using paired t tests (Fig. 4B). We found stronger responses in bilateral dlPFC, vlPFC, and insula during successful self-control trials (Fig. 4C; Table 1). In contrast, stronger responses were observed in inferior parietal lobe, middle and superior temporal gyri, and hippocampal and parahippocampal cortex during failed self-control trials. Interestingly, despite the coarse spatial resolution of the source reconstruction technique, the dlPFC sources identified in the Success > Failure comparison match previous fMRI results (Fig. 4C, inset) for self-control in dieters (Hare et al., 2009), intertemporal choice (McClure et al., 2004), and regulation of craving in smokers (Kober et al., 2010).

Figure 4.

Analysis of self-control success versus failure. A, Heat map showing significant activity for self-control success (yes to healthy disliked, no to unhealthy liked) versus failure. Significant effects were visible at multiple time windows including 400–450, 550–600, and 800–900 ms (dashed green boxes). However, only in the first 150–200 ms window (solid green box) did source localizations reach the stringent significance threshold of FWE-corrected p = 0.01. B, “Glass brain” display depicting MIP of source reconstructions from 150 to 200 ms for Success > Failure (black) and Failure > Success (gray), FWE-corrected p < 0.01. C, Sources overlaid on representative brain images (warm colors, Success > Failure; cool colors, Failure > Success). Inset, Spherical masks based on peak coordinates from 3 fMRI studies [blue, Kober et al. (2010); magenta, Hare et al. (2009); cyan, McClure et al. (2004)], 6 mm radius.

ERP and early attentional filtering: PLV between frontal and occipital sensors

The final test of early attentional filtering involved looking for differences in PLV (Lachaux et al., 1999) between frontal and occipital sensors during successful self-control, particularly in the alpha band (8–12 Hz). Previous studies suggest that long-range synchronization between frontal and occipital sensors is a plausible mechanism for top-down attentional filtering (Zanto et al., 2010, 2011). Importantly, the hypothesized change in phase coherence is expected to occur before the onset of the N1-evoked potentials: for example, increased PLV associated with attentional control has been reported between 15 and 130 ms after stimulus onset (Zanto et al., 2010). Although this time window partially overlaps with the visual P1 component, alpha phase modulation did not significantly correlate with attentional modulation, in line with previous work suggesting partial independence of event-related responses and PLV (Thut et al., 2003). Instead, it is likely that PLV reflects anticipatory gating by the frontoparietal attention network.

To test this hypothesis, we computed alpha-band PLV between frontal and occipital SOIs defined a priori based on scalp location (Fig. 5A, left). PLVs were computed for the window from 100 ms pre- to 300 ms poststimulus onset, with special interest in the time window preceding the onset of the N1 response (∼150–200 ms). Failures of self-control were associated with significantly lower PLVs between frontal and occipital SOIs relative to self-control successes, with the significance of permutation-corrected paired t tests peaking between 98 and 160 ms after stimulus onset (Fig. 5A, top right). As a control, we performed a similar PLV analysis between sets of “non-SOI” sensors, based on a priori definitions for anterior frontotemporal versus posterior occipitotemporal electrodes. During the same time window of interest, these sensor sets did not show any significant difference between successful versus failed self-control (Fig. 5A, bottom right). Confirming this pattern (Fig. 5B), the difference between self-control success and failure in SOI versus non-SOI electrodes was significant in the 100–150 ms window, as measured by a paired t test (t(27) = 2.1, p = 0.045).

Given the latency of the PLV differences, one potential concern is that they could be driven by ERP modulation of the P1. However, in line with Zanto et al. (2010), we found no significant difference between ERP responses to successful and failed self-control in the time preceding the N1. Thus, our results are consistent with previous reports of the partial independence of ERP and PLV measures (Thut et al., 2003).

Because estimates of PLV are inflated when the number of trials is low, the unequal numbers of trials in the self-control success versus failure conditions presents another cause for concern. However, this asymmetry is unlikely to explain our results, as the small number of self-control failures would create bias in the opposite direction to our findings. Consistent with this idea, weighting the average PLV computation by the number of trials per individual produced an even more marked visual separation (unreported) between the success and failure conditions.

Together, these results support the hypothesis that increased self-control involves early attentional filtering, implemented via increased synchronization between activity in frontal and posterior regions. This pattern may reflect dynamic fluctuations in top-down attentional filtering by dlPFC, in keeping with its role in ignoring irrelevant stimuli during perceptual and working memory tasks (Zanto and Gazzaley, 2009; Lennert and Martinez-Trujillo, 2011; Suzuki and Gottlieb, 2013). Consistent with this idea, a post hoc analysis showed that reaction times were significantly slower for failed than for successful self-control trials (t(27) = −3.6, p = 0.002), perhaps reflecting increased influence of distracting information on decision-making in these trials.

ERP evidence for late value modulation: stimulus value signals in vmPFC

Next, we performed three separate tests of the hypothesis that self-control involves late modulation of stimulus value signals in vmPFC, by increasing the extent to which values are responsive to health attributes and/or decreasing the extent to which they are responsive to taste attributes. The first test verified that the same regions of vmPFC encoded stimulus values during the NC and SCC session. The second test is based on the idea that the extent to which the taste attribute is represented in the value signals should decrease between the NC and the SCC, and/or that the opposite should be true for the health attribute. The third test looked for evidence of modulation of vmPFC by dlPFC at the later stages of the decision trial using a Granger causality analysis.

Consider the first test, which asked whether there is a common region of vmPFC that encoded stimulus values during the NC and SCC sessions. This test is important because previous fMRI (Yang et al., 2003; Kable and Glimcher, 2007; Knutson et al., 2007; Tom et al., 2007; Hare et al., 2008, 2009, 2010; Boorman et al., 2009; Chib et al., 2009; FitzGerald et al., 2009; Basten et al., 2010; Philiastides et al., 2010; Plassmann et al., 2010; Wunderlich et al., 2010; Litt et al., 2011), EEG (Harris et al., 2011), and MEG (Hunt et al., 2012) studies have found that a common region of vmPFC encodes stimulus values across a wide class of paradigms, and regardless of the level of self-control deployed by the subjects (Kable and Glimcher, 2007; Hare et al., 2009, 2011; Hutcherson et al., 2012).

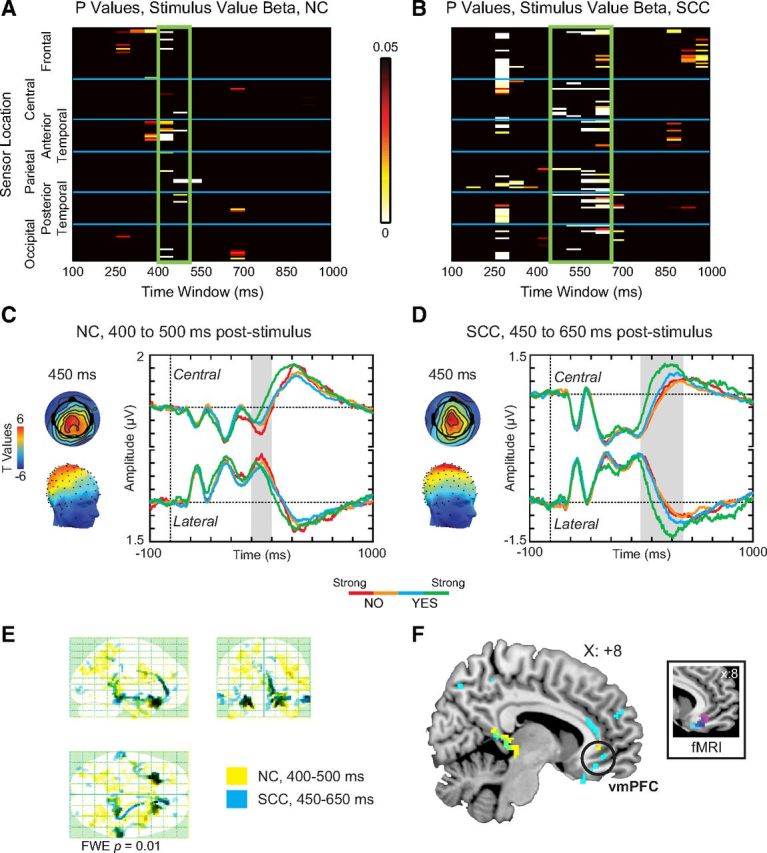

We tested for this hypothesis in two steps. First, we estimated a linear regression, across 50 ms bins, from 100 to 1000 ms after stimulus onset, of each subject's evoked activity versus the decision made in each trial (1 = Strong-No to 4 = Strong-Yes). The resulting maps of estimated coefficients (i.e., beta maps) were then aggregated across subjects using one-sample t tests for each sensor and time window. Results were corrected for multiple comparisons using exact permutation tests. We found significant activity related to stimulus values beginning at 400–450 ms after stimulus onset, for both the NC and the SCC, distributed over central and frontotemporal sensors (Fig. 6A,B). Grand average waveforms, computed from sensors-of-interest with significant stimulus value activity at p ≤ 0.05, showed a clear separation of activity by stimulus value during this time window, with the linear effect reaching corrected significance from 400 to 500 ms in the NC, and from 450 to 650 ms in the SCC (Fig. 6C,D, gray boxes). Furthermore, we found no significant differences in the coding of stimulus values between the NC and SCC during the 400–650 ms window (t(27) = 0.02, p = 0.99).

Figure 6.

Analysis of stimulus value. Top, Heat maps of significant p values associated with stimulus value in (A) NC and (B) SCC sessions. Both sessions show significant stimulus value activity arising from ∼400–450 ms after stimulus onset (green boxes). Middle, Topographic scalp distribution (left) and average waveforms (right) for (C) 400–500 ms period in NC, and (D) 450–650 ms period in SCC. For all average waveforms, the highlighted gray window indicates the window of significant activity, which was also specified as the time window of interest for source reconstruction. Red, Strong No; orange, No; cyan, Yes; green, Strong Yes. E, Source reconstruction results for NC (yellow) and SCC (cyan, 450–650 ms) sessions displayed on a glass brain MIP. F, Sources overlaid on a representative brain image show localization to regions including vmPFC (circled). Inset, Spherical masks based on peak coordinates from three fMRI studies [blue, Plassmann et al. (2007); magenta, Hare et al. (2009); cyan, Litt et al. (2010)], 6 mm radius.

Second, we performed a Bayesian source reconstruction to localize the stimulus value signals to specific brain regions. Figure 6E and Tables 2 and 3 describe the resulting maximum intensity projections. Stimulus value activity was consistently localized to vmPFC (Fig. 6F), in both the NC and SCC conditions. Interestingly, and despite the limited precision of source reconstruction methods, the localized signals in vmPFC closely resembled those from previous fMRI and EEG results (Fig. 6F, inset).

ERP evidence for late value modulation: differential representation of health and taste attributes during SCC trials

Next, we hypothesized that late value modulation during the SCC, compared with the NC, would be associated with a decreased representation of taste attributes and/or an increased representation of health attributes, especially in frontal sensors related to the vmPFC stimulus value signals.

To test this hypothesis, we examined how activity throughout the brain correlated with the tastiness and healthiness of the foods, particularly in frontal sensors of interest associated with stimulus valuation. In particular, we estimated another linear regression, with similar bins and time windows as the previous one, of each subject's evoked activity versus the taste and health ratings provided for each food in that condition. As before, beta maps were then aggregated across subjects using one-sample t tests for each sensor and time window, and compared using paired t tests corrected by permutation testing.

Consistent with the behavioral data, we found that ERP responses showed widespread greater weighting on taste than health in NC, but not in SCC (Fig. 7A,B). We also found that the ERP weighting on health at central and frontotemporal sensors increased significantly from the NC to the SCC session after 450 ms poststimulus onset, but only minor differences were found for taste weighting between the two conditions (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, and consistent with the hypothesis, the beta map for increases in health weights resembles the time course and sensor map for stimulus value computations. In addition, a Bayesian source reconstruction of the taste and health signals showed vmPFC sources largely overlapping with the region identified above for stimulus valuation (Fig. 7D). More concretely, a comparison of responses in the sensors reflecting stimulus value related activity in both the NC and SCC revealed larger estimated coefficients for taste than health in the NC (t(27) = 4.4, p = 1.6 × 10−4), but not in the SCC. We also found larger estimated coefficients for health in the SCC versus NC (t(27) = −3.4, p = 0.0022), but not for taste.

Figure 7.

Weightings of ERP data on taste and health. A, Heat maps of t values from one-sample t tests on taste (left) and health (right) betas across subjects, in NC (top) and SCC (bottom) sessions. B, Statistical significance maps comparing taste versus health in NC (top) and SCC (bottom) sessions. C, Statistical significance maps comparing NC versus SCC session for taste (left) and health (right). D, Source reconstruction of neural data showing significant weighting on the linear ordering of stimulus value (yellow), tastiness (magneta), and healthiness (magenta). Overlapping source reconstructions are indicated by the color overlays in the key (orange = stimulus value + taste; blue = taste + health; green = stimulus value + health; gray = stimulus value + taste + health).

ERP evidence for late value modulation: Granger causality analysis

The final test for the hypothesis of late value modulation involved looking for directed connectivity from dlPFC to the vmPFC at the time that stimulus values are computed. This hypothesis was motivated by previous fMRI work from our group (Hare et al., 2009, 2011), which found that successful self-control is associated with increased functional connectivity between dlPFC and the vmPFC valuation region. Note, however, that due to the limitations of the BOLD data, our previous work was not able to test for the directionality of the connectivity, or its timing within a decision period.

We tested this hypothesis by carrying out a GCCA (Seth, 2010; Bressler and Seth, 2011) among several ROIs in the SCC session, looking at the 450–650 ms window during which stimulus values are computed. GCCA is useful in this context because it allows us to look for directional interactions between time courses of neural activity. In particular, for two simultaneously measured time-varying signals X and Y, signal X is considered Granger causal if past information about X improves the prediction of signal Y, over what can be predicted using only lagged values of Y.

Because we found differential effects of successful over failed self-control at multiple time periods (including 150–200 ms, 400–450 ms, and 500–550 ms; Fig. 4A), we applied the GCCA to ROIs associated with self-control across all of these periods. To be inclusive, we characterized the ROIs using a conjunction analysis with a liberal threshold of p < 0.005 (uncorrected), for the contrast of successful > failed self-control trials, which identified regions of dlPFC, insula, and inferior frontal gyrus shown in Figure 8B. Additionally, a vmPFC ROI was derived from the conjunction of stimulus value localization at 250–350 ms and 450–650 ms after stimulus onset, which covers the entire period over which activity in frontal sensors correlated with stimulus values.

The GCC analysis among these areas proceeded in several steps, all of them applied to data for the SCC only. First, we performed a Bayesian source reconstruction of the linear contrast for health ratings (least to most healthy) to generate a dipole intensity map for each subject (Fig. 8A, left). We focused on this contrast because the previous results showed an increased weighting on health in both choices and the vmPFC value signals. Second, we used this map to forward-model the projected average time course for each ROI and subject, averaged across hemispheres (Fig. 8A, middle). The resulting time courses are called MIPs. Third, after applying some preprocessing to the time courses, so that they satisfy the required assumptions (Fig. 8A, right), we performed a GCC analysis among the ROIs over the 450–650 ms window (see Materials and Methods for details).

We found no significant Granger causal connections between the ROIs at a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of p = 0.01, over the entire 450–650 ms window. However, an analysis that allowed for differential connectivity during the 450–550 and the 550–650 ms windows found significant results. In particular, as shown in Figure 8B, we found significant connectivity from insula to dlPFC during the 450–550 ms window, and from dlPFC to vmPFC during the 550–650 ms window. A further post hoc check revealed that the dlPFC to vmPFC connectivity also remained significant when the start of the later window was moved to 500 ms.

Together, the last three results provide evidence for the hypothesis that self-control involves modulation from dlPFC to vmPFC, starting ∼550 ms after stimulus onset, that increases the weighting of stimulus value signals in vmPFC on the healthiness of the foods.

Discussion

Although self-control is important for optimal decision-making, it can often be achieved in different ways. Here, in the context of a dietary choice task, we explored the neural bases of two different possible mechanisms for self-control: attentional filtering of early sensory input and later modulation of stimulus value signals computed in vmPFC. By comparing ERP activity when participants were incentivized to make choices naturally or with the goal of losing weight, we investigated the extent to which both mechanisms are activated with and without self-control.

Subjects showed clear changes in their choice behavior from the natural to self-control condition, shifting from almost exclusive reliance on taste attributes to similar weightings on taste and health. These behavioral adjustments were accompanied by changes in neural markers, measured both between the two experimental conditions, and across trials within the self-control condition, suggesting that multiple regions are involved in the successful deployment of self-control.

In line with previous work that has shown attentional modulation of early perceptual components (Rose et al., 2005; Zanto and Gazzaley, 2009), we found differential ERP activity for self-control success versus failure as early as 150–200 ms, associated with the visual N1 response. Joining a growing body of work on mind-wandering and fluctuations in attention (Smallwood and Schooler, 2006; Weissman et al., 2006; Cohen and Maunsell, 2011), the dynamic variations in N1 amplitude suggest that early differences in attentional modulation can be associated with far-reaching behavioral effects.

Where does the effect of attentional filtering on self-control originate? Contrasting source reconstructions for self-control success greater than failure revealed a bilateral network of regions including the dlPFC, insula, and vlPFC. Although the extremely coarse spatial precision of the localization technique limits our inferences, these results agree with an extensive literature on cognitive and emotional regulation. In particular, our dlPFC source is very close to those found in previous fMRI studies of self-control (McClure et al., 2007; Hare et al., 2009; Kober et al., 2010). In addition, the same area of vlPFC identified here has been linked to adjustments of behavior in the face of contextual changes (Mitchell, 2011).

Most intriguingly, the source localization of dlPFC, in conjunction with the reduced N1 response during successful self-control, matches recent work suggesting a special role for this region in attention suppression (Lennert and Martinez-Trujillo, 2011; Suzuki and Gottlieb, 2013). In this light, the reduced N1 response associated with self-control success, relative to failure, may reflect anticipatory suppression in the presence of potentially tempting foods. At first sight, this interpretation runs counter to a previous finding in patients with prefrontal damage, who showed reductions in N1 amplitude compared with matched controls (Swick, 1998). However, it is important to note that this previous experiment was designed to look for neural correlates of attentional enhancement, whereas successful self-control in our task involves attentional filtering. In fact, when inhibition of task-irrelevant information is required, prefrontal patients actually show an increase in early sensory evoked potentials, relative to healthy controls (Knight et al., 1999). Our results highlight the importance of dlPFC for guiding behavior not only through enhancement of goal-relevant information, but also by suppression of potential distractors.

One proposed mechanism for top-down attentional filtering is via long-range synchronization in the alpha band (8–12 Hz). Consistent with other work showing increased early phase-locking between anterior and posterior regions for attended items (Zanto et al., 2010), successful self-control was associated with greater PLV between frontal and occipital sensors preceding the attentional modulation of the N1 response. Although our data cannot determine the direction of this modulation, previous work using transcranial magnetic stimulation strongly implicates prefrontal cortices in top-down changes in PLV (Zanto et al., 2011). With a latency overlapping the earliest cortical visual responses, this phase-coherence modulation does not appear to be stimulus-specific, instead reflecting a more general attention gating. In conjunction with the reduced N1 amplitude, this result points to heightened frontal-occipital synchrony as reflecting a broad suppression of early visual processing. Given that our task demanded continuous self-control over an extended period of time, such early perceptual dampening may form a first-line strategy for successful maintenance of contextual goals.

Aside from early attentional filtering, another possible route for self-control entails shifting the value assigned to specific perceptual attributes, such as taste or health. ERP activity in the time range associated with stimulus value computations, ∼450–650 ms after stimulus onset, demonstrated just such a shift in health weightings at spatially overlapping sensors, and both stimulus value and taste and health value signals were localized to vmPFC. Although ERP correlates of energetic value (fat content) have been reported as early as 165 ms after stimulus onset (Toepel et al., 2009), our data suggest that valuation of taste and health attributes occurs relatively late, beyond the window of early perceptual processing.

Our findings therefore raise the question, suggested by previous neuroimaging (Hare et al., 2009, 2011) and rTMS (Camus et al., 2009; Cho and Strafella, 2009; Baumgartner et al., 2011) studies, of whether dlPFC can modulate vmPFC stimulus value computations during self-control. To test this idea, we examined the functional connectivity between these regions during the window of stimulus value computation via Granger causality. Although analysis of the larger time period from 450 to 650 ms failed to find any causal connections, further subdivision of the time course revealed significant causal connectivity from dlPFC to vmPFC from 500 to 650 ms. Although the precise nature of this later top-down modulation remains unclear, these results join several recent studies demonstrating that dlPFC plays a causal role in decision-making (Camus et al., 2009; Cho and Strafella, 2009; Figner et al., 2010; Baumgartner et al., 2011; Philiastides et al., 2011).

We emphasize that although Granger connectivity is not sufficient to establish full causality, our data complement these findings by providing high-resolution information about when self-control modulations occur over the time course of choice. In pointing to the existence of multiple neural mechanisms by which dlPFC can affect behavior, our results also help to unify the decision-making literature with similar findings from attention and working memory (Zanto et al., 2011), suggesting various routes by which this region may influence behavior to reflect contextual goals.

Together, our results suggest that self-control during a simple choice task involves a combination of both early attentional filtering and late value signal modulation. This result mirrors a trend in conceptualizing self-control, epitomized by frameworks such as the dual mechanisms of control (DMC) account (Braver, 2012). Emphasizing the intrinsic variability of cognitive control, DMC posits the existence of two different modes of control, proactive and reactive, associated with different brain networks. Whereas proactive control reflects sustained, anticipatory activity in lateral prefrontal cortex, reactive control is asserted in a bottom-up fashion at the time of choice, arising transiently from stimulus-driven interference or episodic associations. Despite obvious parallels to this theoretical framework, especially in terms of proactive control, our data diverge from the DMC account in certain respects. For example, although the results of our Granger causal modeling are consistent with vmPFC value modulation as a “late correction” mechanism, the lack of interference measures in our experiment complicates any attempt to link this finding to reactive control.