Abstract

Background

Patterns of social and structural factors experienced by vulnerable populations may negatively affect willingness and ability to seek out health care services, and ultimately, their health.

Methods

The outcome variable was utilization of health care services in the previous 12 months. Using Andersen’s Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations, we examined self-reported data on utilization of health care services among a sample of 546 Black, street-based female sex workers in Miami, Florida. To evaluate the impact of each domain of the model on predicting health care utilization, domains were included in the logistic regression analysis by blocks using the traditional variables first and then adding the vulnerable domain variables.

Findings

The most consistent variables predicting health care utilization were having a regular source of care and self-rated health. The model that included only enabling variables was the most efficient model in predicting health care utilization.

Conclusions

Any type of resource, link, or connection to or with an institution, or any consistent point of care contributes significantly to health care utilization behaviors. A consistent and reliable source for health care may increase health care utilization and subsequently decrease health disparities among vulnerable and marginalized populations, as well as contribute to public health efforts that encourage preventive health.

Vulnerable populations are highly impacted by social ills resulting from structural inequalities, such as suffering higher rates of poverty, homelessness, and violence (Aday 1994; Butters and Erickson 2003; Lazarus et al.2011; O’Daniel 2011). The interaction of these structural factors, often embedded in racist and sexist ideologies, and their consequences on minority communities may affect health care utilization patterns of marginalized populations. Low income, Black women are particularly vulnerable to adverse health outcomes. Doubly marginalized due to gender and racial inequalities, they experience lower life expectancies, higher age-adjusted death rates, and higher rates of a host of diseases, including diabetes, stroke, heart disease, obesity and cancer than women of other ethnicities (Institute of Medicine 2002).

Black women who engage in survival sex work also experience significant health disparities, being more than twice as likely as women of other ethnicities to test positive for HIV (Surratt and Inciardi 2004). Street-based female sex workers are particularly vulnerable to health problems and often neglect their health, seeking care only when at advanced stages of morbidity. Trauma, drug use, homelessness, poverty, violence, stigma and discrimination are some of the experiences that significantly impact the well being of sex workers and contribute to poor physical and mental health (Kurtz et al. 2004; Surratt and Inciardi 2004; Surratt et al. 2005). These factors, however, are sometimes the very reason sex workers do not seek help. Sex workers use health services inconsistently, with low rates of preventive care. They often lack a regular doctor, health insurance, identification, transportation, and safety, and are at a higher risk for being homeless and victims of violence. This combination of social/political/economic issues perpetuates inequality and may affect the way these women view their health and health practices.

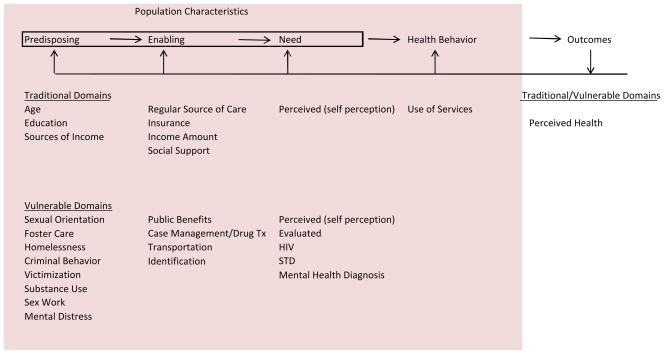

Andersen’s Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (1968, 1995, Gelberg et al.2000) has been used as a framework to examine whether the factors that makes a population vulnerable might also affect use of health services and health status (see Figure 1). The model suggests that health care utilization is a function of three components: a predisposition by people to use health services, factors that enable or impede use, and people’s urgency for care (Andersen 1968, 1995). Each component is divided into traditional and vulnerable domains that are especially important to examine in understanding the health needs and behaviors of vulnerable populations. In this paper, we argue that patterns of social and structural factors experienced by vulnerable populations may negatively affect their willingness and ability to seek out health care services, and ultimately, their health. Using Andersen’s Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (1968, 1995, Gelberg et al.2000), we examined barriers to health care access and utilization among a sample of Black, street-based female sex workers in Miami, Florida.

Figure 1.

The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations

Methods

Data were drawn from baseline interviews originally conducted as part of a randomized intervention trial designed to test two case management approaches for increasing health services linkages among the target population. Eligible participants were self-identified Black women between the ages of 18–50 who had: a) traded sex for money or drugs at least three times in the past thirty days; and, b) used cocaine, crack, or heroin three or more times a week in the past thirty days. The sample was recruited into the study using targeted and snowball sampling strategies (Watters and Biernacki 1989). Participants were recruited from the community by peer outreach workers and participant referrals. Initial screening occurred via telephone and if eligible, participants were invited to the study office where they were re-screened upon arrival. If eligibility was confirmed, informed consent was obtained, and participants were enrolled and interviewed face-to-face, using structured questionnaires administered through CAPI (Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing). Participants were given $25 compensation at completion of the baseline interview.

Study enrollment commenced in May 2007 and was completed in June 2010, with 562 women enrolled. The sample size for this analysis was 546 due to missing data. Project staff completed the requirements of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) web-based certification for protection of human subjects and study protocols were approved by our institutional review board. Data were collected using the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs Initial (GAIN-I). The GAIN-I is a comprehensive instrument that has eight core sections: Background; Substance Use; Physical Health; Risk Behaviors and Disease Prevention; Mental and Emotional Health; Environment and Living Situation; Legal; and Vocational (Dennis et al. 2002). Alphas for the scales used in the current study ranged between .66 to .97.

The outcome variable was receipt of physical health care in the past year and was coded dichotomously. The independent variables were organized into the predisposing, enabling, and need factors that may affect health care utilization using the framework from Andersen’s model (Figure 1). Within each of these constructs, variables were further divided into the Traditional Domain or Vulnerable Domain.

Traditional predisposing variables are age, education, and sources of income. Age was collected as a continuous variable and dichotomized for analysis using the mean age (39.29) to determine the categories. Additional predisposing variables measured as part of the vulnerable domain include sexual orientation, foster care history, homelessness, criminal behavior, victimization, mental distress, substance abuse, and sex work history. Substance use was measured with various questions quantifying the use of different substances in the past 90 days. The items were part of a scale determining whether participants met the DSM -IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition) criteria for substance abuse or dependence. The predisposing variables in the vulnerable domain represent potential marginalized statuses. Participant’s mental state was evaluated using the General Mental Distress Scale based on DSM-IV symptom criteria for depression, anxiety disorders, and somatic symptoms(Dennis, Chan, and Funk 2006) in addition to a Traumatic Stress Index. This index assesses the presence of symptoms of stress disorders related to trauma over the past 12 months. Higher scores on these scales signify more severe problems.

Traditional enabling predictors included whether participants had a regular source of health care, insurance status, income amount, and social support. Social support data were collected via the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey (Sherbourne and Stewart 1991). There are four separate social support scales totaling eighteen items: emotional/informational, tangible, affectionate, and positive social interaction. Vulnerable enabling predictors included variables that may assist or hinder access to health care for vulnerable populations. For example, participants were asked whether they received public benefits, received case management or drug treatment services, had their own transportation, and had valid identification.

Need predictors were divided into perceived health and evaluated health. Measures of perceived health include self-rated health, perceived physical health, and perceived mental health. The markers available for evaluated health were: diagnosis of a mental, emotional, or psychological problem; HIV status; and sexually transmitted disease history. Pregnancy in the previous 12 months was not included as a predictor of utilization as 98.2% had not been pregnant in the 12 months prior to being interviewed.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 20. Blockwise logistic regression was used to examine the contributions of each of the variable domains to health care utilization and select the best fitting model. The first set of models focus on the predisposing, enabling, and need components of the traditional and vulnerable domains that predict utilization of physical health care services in the past year. Domains were included in the analysis by blocks using the traditional items first and then adding the vulnerable domain items to evaluate the effect of the vulnerable domains on the dependent variable. In the final model, variables that were significant at p<.05 were determined to have significant effects on the dependent variable of utilization.

Model 1- Traditional Domain Predisposing

Model 2- Traditional Domain and Vulnerable Domain Predisposing

Model 3- Traditional Domain Enabling

Model 4- Traditional Domain and Vulnerable Domain Enabling

Model 5- Traditional Domain Need

Model 6- Traditional Domain and Vulnerable Domain Need

Model 7- All domains and variables

The purpose of the modeling approach is to examine whether the vulnerable domain variables in combination with the traditional domain variables, better predict health care utilization for these vulnerable women (Figure 1). In addition, this modeling approach allows the comparison of predisposing, enabling, and need variables in order to distinguish which set of variables better predicts health care utilization within this sample. For instance, Andersen intended for the predisposing characteristics to measure structural factors in accessing care. Variables like ethnicity, education, and occupation were intended to characterize the status of a person in the community. However, the status of these women, due to their ethnicity and primary source of income, is not represented in the conceptual model as they were all Black, female sex workers. The vulnerable domains are useful in measuring other variables representing possible structural issues.

Results

Of the 546 women included in these analyses, 68.5% had seen a doctor in the 12 months prior to being interviewed. The demographic and behavioral characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. All participants in the sample self-identified as female and Black. The average age of the sample was 39.3 years. Most women had unstable living situations as 65.0% considered themselves homeless at some point in the 12 months prior to being interviewed. Substance use was a serious problem for these women as the mean score for the DSM-IV scale of substance dependence was 1.89 with 2.00 being the maximum possible score. For the measure of general mental distress, there were particularly high scores on the internal mental distress and depressive symptoms components. Among the enabling variables, 57.5% of women had a regular source of health care, but only 33.3% had any type of health insurance. A little more than half of the women (54.2%) had at least one experience with drug treatment in their lives. Need variables of special interest include self-rated health where 43.2% reported fair/poor health, 35.3% reported good health, and 21.4% reported excellent/very good health. Regarding HIV status, 16.8% of the women were positive.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| % | Frequency N=546 |

Mean (SD) | Range Min, Max |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||||

| Doc Visit in 12 Months | ||||

| No | 31.5 | 172 | ||

| Yes | 68.5 | 374 | ||

| Independent Variables | ||||

|

Predisposing

Traditional

| ||||

| Age | ||||

| 18–39 | 43.4 | 237 | ||

| 40+ | 56.6 | 309 | ||

| Education | ||||

| No HS Diploma | 51.5 | 281 | ||

| HS Diploma/GED | 48.5 | 265 | ||

| Sources of Income | ||||

| Job | 11.2 | 61 | ||

| Welfare, Public Assistance, AFDC, Food Stamps | 51.3 | 280 | ||

| Social Security, Disability | 19.8 | 108 | ||

| Spouse, Family, Friend | 39.0 | 213 | ||

| Selling or Trading Goods | 6.8 | 37 | ||

| Prostitution | 89.6 | 489 | ||

| Other Illegal Activity | 9.2 | 50 | ||

|

Predisposing

Vulnerable

| ||||

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 65.0 | 355 | ||

| Lesbian/Bisexual | 35.0 | 191 | ||

| Foster Care | ||||

| No | 83.3 | 455 | ||

| Yes | 16.7 | 91 | ||

| Homeless past 12 months | ||||

| No | 35.0 | 191 | ||

| Yes | 65.0 | 355 | ||

| Arrests | 9.79 (16.98) | 0, 153 | ||

| Years in Sex Work | 14.53 (9.21) | 0, 38 | ||

| Victimization Scale | 6.85 (3.41) | 0, 11 | ||

| Substance Use (DSM) | 1.89 (0.37) | 0, 2 | ||

| Internal Mental Distress | 1.41 (0.70) | 0, 2 | ||

| Somatic Symptoms | 1.09 (0.65) | 0, 2 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | 1.43 (0.70) | 0, 2 | ||

| Anxiety/Fear | 1.19 (0.76) | 0, 2 | ||

| Trauma | 1.35 (0.90) | 0, 2 | ||

|

Enabling

Traditional

| ||||

| Regular Source of Care | ||||

| No | 42.5 | 232 | ||

| Yes | 57.5 | 314 | ||

| Health Insurance | ||||

| No | 66.7 | 364 | ||

| Yes | 33.3 | 182 | ||

| Income Amount | ||||

| less than $1000 | 34.2 | 187 | ||

| $1,000–1,999 | 29.7 | 162 | ||

| $2,000–3,999 | 25.6 | 140 | ||

| $4,000–5,999 | 5.9 | 32 | ||

| $6,000 or more | 4.6 | 25 | ||

| Social Support | ||||

| Emotional/Informational | 3.11 (1.24) | 1, 5 | ||

| Tangible | 3.20 (1.47) | 1, 5 | ||

| Affectionate | 3.53 (1.42) | 1, 5 | ||

| Positive Interaction | 3.38 (1.41) | 1, 5 | ||

|

Enabling

Vulnerable

| ||||

| Drug Treatment | ||||

| No | 45.8 | 250 | ||

| Yes | 54.2 | 296 | ||

| Transportation | ||||

| Own Car | 7.3 | 40 | ||

| Rely on Other Means | 92.7 | 506 | ||

| Identification | ||||

| No | 24.7 | 135 | ||

| Yes | 75.3 | 411 | ||

|

Need

Traditional

| ||||

| Self-Rated Health | ||||

| Excellent/Very Good | 21.4 | 117 | ||

| Good | 35.3 | 193 | ||

| Fair/Poor | 43.2 | 236 | ||

|

Need

Vulnerable

| ||||

| Mental Health Dx | ||||

| No | 55.9 | 305 | ||

| Yes | 44.1 | 241 | ||

| Health Problem/last 12 months | ||||

| No | 39.2 | 214 | ||

| Yes | 60.6 | 332 | ||

| HIV | ||||

| Negative | 78.2 | 427 | ||

| Positive | 16.8 | 92 | ||

| Unknown | 4.9 | 27 | ||

| STD/last 12 months | ||||

| No | 76.2 | 416 | ||

| Yes | 23.8 | 130 | ||

| Mentally Disturbed/last 12 months | ||||

| No | 30.2 | 165 | ||

| Yes | 69.8 | 381 | ||

Multivariate Results

Although all models were compared to distinguish which set of variables did a better job at predicting health care utilization, overall results are briefly described here with a focus on models that best fit the data. Tables 2, 3, and 4 show the complete logistic regression results for Models 1–7 using the variables from Andersen’s Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations to predict health care utilization in the previous 12 months.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression-Predisposing Characteristics

| Independent Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| N=546 | Coef. | OR | CI | Coef | OR | 95% CI |

|

|

||||||

|

Predisposing

Traditional

| ||||||

| Age1 | 0.42* | 0.66 | 0.45–0.98 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.43–1.10 |

| Education2 | 0.44* | 1.55 | 1.05–2.28 | 0.47* | 1.60 | 1.07–2.39 |

| Source of Income | ||||||

| Job3 | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.49–1.61 | 0.18 | 0.83 | 0.45–1.54 |

| Public Assist.,Welfare, etc.3 | 0.62* | 1.85 | 1.26–2.73 | 0.60** | 1.83 | 1.23–2.73 |

| S. Security, Disability, etc.3 | 1.59* | 4.89 | 2.54–9.42 | 1.51** | 4.51 | 2.28–8.95 |

| Spouse, Family, Friend3 | 0.53* | 1.71 | 1.12–2.59 | 0.60** | 1.82 | 1.18–2.80 |

| Sell/Trade Goods3 | 0.45 | 0.64 | 0.30–1.35 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.26–1.25 |

| Prostitution3 | 0.79* | 2.20 | 1.16–4.19 | 0.70* | 2.02 | 1.03–3.94 |

| Other Illegal Activity3 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.55–2.05 | .000 | 1.00 | 0.51–1.98 |

|

Predisposing

Vulnerable

| ||||||

| Sexual Orientation4 | 0.13 | 0.88 | 0.58–1.35 | |||

| Foster Care3 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.66–2.03 | |||

| Homeless past 12 months3 | 0.40 | 1.49 | 0.94–2.36 | |||

| Arrests | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | |||

| Years in Sex Work | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.97–1.02 | |||

| Victimization | 0.08* | 1.08 | 1.01–1.16 | |||

| Substance Use (DSM) | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.54–1.72 | |||

| Internal Mental Distress | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.50–1.86 | |||

| Somatic Symptoms | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.65–1.38 | |||

| Depressive Symptoms | 0.36 | 1.44 | 0.89–2.31 | |||

| Anxiety/Fear | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.60–1.44 | |||

| Trauma | 0.16 | .085 | 0.65–1.13 | |||

|

Enabling

Traditional

| ||||||

| Regular Source of Care | ||||||

| Health Insurance | ||||||

| Income Amount | ||||||

| Social Support | ||||||

| Emotional/Information | ||||||

| Tangible | ||||||

| Affectionate | ||||||

| Positive Interaction | ||||||

|

Enabling

Vulnerable

| ||||||

| Drug Treatment | ||||||

| Transportation | ||||||

| Identification | ||||||

|

Need

Traditional

| ||||||

| Good Self-Rated Health | ||||||

| Fair/Poor Self-Rated Health | ||||||

|

Need

Vulnerable

| ||||||

| Mental Health Dx | ||||||

| Health Problem | ||||||

| HIV Positive | ||||||

| HIV Status Unknown | ||||||

| STD/last 12 months | ||||||

| Mentally Disturbed | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| X2 | 55.37, 9df, p<.01 | 67.81, 21df, p<.01 | ||||

| Constant Coefficient | −0.59, p=.12 | −1.10, p=.12 | ||||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 625.01 | 612.57 | ||||

p<.05;

p<.01;

: reference category is 18–39;

: reference category is no H.S. diploma;

: reference category is ‘no/none’;

: reference category is lesbian, bisexual, other, unsure

Table 3.

Logistic Regression-Enabling Characteristics

| Independent Variables | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| N=546 | Coef. | OR | 95% CI | Coef. | OR | 95% CI |

|

|

||||||

| Predisposing Traditional | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Age1 | −0.55* | 0.58 | 0.37–0.90 | −0.63** | 0.53 | 0.34–0.83 |

|

| ||||||

| Education2 | 0.47* | 1.60 | 1.05–2.43 | 0.43* | 1.53 | 1.00–2.35 |

| Source of Income | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Job3 | −0.16 | 0.85 | 0.44–1.64 | −0.32 | 0.73 | 0.37–1.43 |

|

| ||||||

| Public Assist., Welfare3 | 0.31 | 1.36 | 0.89–2.09 | 0.25 | 1.29 | 0.83–1.99 |

|

| ||||||

| S. Security, Disability, etc.3 | 0.77 | 2.16 | 0.95–4.92 | 0.66 | 1.94 | 0.84–4.49 |

|

| ||||||

| Spouse, Family, Friend3 | 0.45 | 1.57 | 0.98–2.51 | 0.41 | 1.51 | 0.93–2.43 |

|

| ||||||

| Sell/Trade Goods3 | −0.25 | 0.78 | 0.34–1.78 | −0.37 | 0.69 | 0.31–1.58 |

|

| ||||||

| Prostitution3 | 0.99** | 2.69 | 1.33–5.44 | 1.02** | 2.78 | 1.97–5.65 |

|

| ||||||

| Other Illegal Activity3 | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.55–2.33 | 0.09 | 1.09 | 0.52–2.27 |

|

| ||||||

| Predisposing Vulnerable | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Foster Care | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Homeless past 12 months | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Arrests | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Years in Sex Work | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Victimization | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Substance Use (DSM) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Internal Mental Distress | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Somatic Symptoms | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Anxiety/Fear | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Trauma | ||||||

| Enabling Traditional | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Regular Source of Care3 | 1.61** | 4.98 | 3.15–7.89 | 1.61** | 4.99 | 3.14–7.95 |

|

| ||||||

| Health Insurance3 | 0.72* | 2.04 | 1.08–3.87 | 0.74* | 2.09 | 1.09–4.02 |

|

| ||||||

| Income Amount | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.81–1.21 | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.80–1.20 |

|

| ||||||

| Social Support | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Emotional/Information | −0.08 | 0.93 | 0.73–1.18 | −0.03 | 0.97 | 0.75–1.24 |

|

| ||||||

| Tangible | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.97–1.49 | 0.16 | 1.18 | 0.94–1.47 |

|

| ||||||

| Affectionate | −0.10 | 0.90 | 0.68–1.19 | −0.11 | 0.89 | 0.67–1.19 |

|

| ||||||

| Positive Interaction | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.76–1.25 | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.76–1.25 |

| Enabling Vulnerable | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Drug Treatment3 | 0.56* | 1.75 | 1.14–2.69 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Transportation3 | 1.03 | 2.79 | 0.95–8.24 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Identification3 | 0.27 | 1.31 | 0.81–2.12 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Need Traditional | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Good Self-Rated Health | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Fair/Poor Self-Rated Health | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Need Vulnerable | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Mental Health Dx | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Health Problem | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| HIV Positive | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| HIV Status Unknown | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| STD/last 12 months | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Mentally Disturbed | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| X2 | 130.93, 16df, p<.01 | 143.49, 19df, p<.01 | ||||

| Constant Coefficient | −1.27, p<.05 | −1.72, p<.01 | ||||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 549.44 | 536.89 | ||||

p<.05;

p<.01;

: reference category is 18–39;

: reference category is no H.S. diploma;

: reference category is ‘no/none’

Table 4.

Logistic Regression- Need Characteristics and Full Model

|

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| N=546 | Coef | OR | 95% CI | Coef. | OR | 95% CI | Coef. | OR | 95% CI |

|

|

|||||||||

| Predisposing Traditional | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Age1 | −0.43* | 0.65 | 0.44–0.97 | 0.44* | 0.64 | 0.43–0.97 | −0.54 | 0.59 | 0.34–4.01 |

|

| |||||||||

| Education2 | 0.42* | 1.52 | 1.03–2.24 | 0.48* | 1.61 | 1.08–2.41 | 0.44 | 1.55 | 0.98–2.45 |

| Source of Income | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Job3 | 0.10 | 0.91 | 0.49–1.66 | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.49–1.67 | −0.33 | 0.72 | 0.36–1.45 |

|

| |||||||||

| Public Assist. etc.3 | 0.66** | 1.94 | 1.31–2.87 | 0.57* | 1.77 | 1.18–2.67 | 0.27 | 1.31 | 0.82–2.10 |

|

| |||||||||

| S. Security, Disability,3 | 1.59** | 4.91 | 2.54–9.48 | 1.12* | 3.08 | 1.53–6.18 | 0.66 | 1.93 | 0.77–4.84 |

|

| |||||||||

| Spouse, Family, Friend3 | 0.56** | 1.75 | 1.15–2.67 | 0.55* | 1.74 | 1.12–2.69 | 0.47 | 1.60 | 0.95–2.70 |

|

| |||||||||

| Sell/Trade Goods3 | −0.47 | 0.62 | 0.29–1.33 | 0.55 | 058 | 0.27–1.26 | −0.33 | 0.72 | 0.30–1.74 |

|

| |||||||||

| Prostitution3 | 0.65 | 1.92 | 0.99–3.71 | 0.64 | 1.90 | 0.96–3.77 | 0.07 | 2.02 | 0.93–4.39 |

|

| |||||||||

| Other Illegal Activity3 | 0.10 | 1.11 | 0.57–2.16 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.47–1.88 | 0.18 | 1.19 | 0.54–2.64 |

|

| |||||||||

| Predisposing Vulnerable | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Sexual Orientation4 | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.60–1.60 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Foster Care3 | 0.20 | 1.22 | 0.64–2.35 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Homelessness3 | 0.03 | 1.04 | 0.60–1.78 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Arrests | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Years in Sex Work | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Victimization | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.99–1.16 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Substance Use (DSM) | −0.13 | 0.88 | 0.44–1.76 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Internal Mental Distress | −0.21 | 0.81 | 0.38–1.71 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Somatic Symptoms | −0.27 | 0.76 | 0.49–1.18 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 0.65* | 1.92 | 1.10–3.33 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Anxiety/Fear | −0.09 | 0.92 | 0.55–1.51 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Trauma | −0.18 | 0.83 | 0.60–1.16 | ||||||

| Enabling Traditional | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Regular Source of Care3 | 1.84** | 6.26 | 3.70–10.60 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Health Insurance3 | 0.57 | 1.76 | 0.89–3.50 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Income Amount | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.77–1.17 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Social Support | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Emotional/Informational | −0.03 | 0.97 | 0.74–1.27 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Tangible | 0.18 | 1.19 | 0.94–1.52 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Affectionate | −0.04 | 0.96 | 0.71–1.29 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Positive Interaction | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.74–1.30 | ||||||

| Enabling Vulnerable | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Drug Treatment3 | 0.14 | 1.15 | 0.70–1.89 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Transportation3 | 1.17* | 3.23 | 1.06–9.78 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Identification3 | 0.27 | 1.31 | 0.79–2.18 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Need Traditional | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Good Self-Rated Health5 | 0.67* | 1.95 | 1.15–3.31 | 0.56* | 1.76 | 1.02–3.02 | 0.84** | 2.32 | 1.23–4.38 |

|

| |||||||||

| Fair/Poor Self-Rated5 | 0.47 | 1.60 | 0.96–2.67 | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.69–2.08 | 0.51 | 1.66 | 0.85–3.24 |

| Need Vulnerable | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mental Health Dx3 | 0.56* | 1.75 | 1.14–2.70 | 0.45 | 1.56 | 0.92–2.66 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Health Problem6 | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.78–1.83 | 0.23 | 1.25 | 0.77–2.04 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| HIV Positive7 | 0.92* | 2.52 | 1.26–5.03 | 0.22 | 1.25 | 0.55–2.85 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| HIV Status Unknown7 | 0.53 | 1.70 | 0.63–4.54 | 1.08* | 2.94 | 1.00–8.67 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| STD/last 12 months3 | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.72–2.00 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.60–1.88 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Mentally Disturbed6 | 0.16 | 1.17 | 0.75–1.82 | 0.31 | 1.36 | 0.76–2.47 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| X2 | 61.56 11df p<.01 | 81.65 17df p<.01 | 174.00 39df p<.01 | ||||||

| Constant Coefficient | −0.92, p<.05 | −1.25, p<.01 | −2.99, p<.01 | ||||||

| −2Log Likelihood | 618.82 | 598.73 | 506.38 | ||||||

p<.05;

p<.01;

: reference category is 18–39;

: reference category is no H.S. diploma;

: reference category is ‘no/none’;

: reference category is lesbian, bisexual, other, unsure;

: reference category is excellent/very good;

: reference category is never/more than 12 months ago;

: reference category is HIV negative

Predisposing

The results for multivariate Models 1 and 2, with health care utilization in the past 12 months regressed on predisposing traditional variables (Model 1) and then all predisposing variables (Model 2), are presented in Table 2. The traditional predisposing variables associated with health care utilization were age, education, and certain sources of income. Among the vulnerable predisposing variables, victimization was the only one significantly related to utilization. Comparing the fit of model 2 to Model 1, the addition of vulnerable variables in Model 2 did not represent a significant improvement in fit relative to Model 1.

Enabling

The results for Models 3 and 4 regressed health care utilization on the enabling traditional variables first (Model 3) and then the vulnerable enabling variables (Model 4) (see Table 3). In Model 3, women with a regular source of care (OR=4.98, 95% CI 3.15–7.89) and women with some type of health insurance (OR= 2.04, 95% CI 1.08–3.87) had higher odds of having seen a health care provider in the past 12 months compared to those without a regular source of care or health insurance. Since the variables in Model 1 are nested in Model 3, the models were compared, and Model 3 fit the data better than Model 1; the inclusion of the enabling traditional variables enhanced the fit of the data.

In Model 4, the enabling vulnerable variables were added to the enabling traditional variables to predict health care utilization. Having a regular source of care (p<.01) and insurance status (p<.05) remained significant in predicting health care utilization for these women. In addition, women who had been in drug treatment at least once had higher odds (OR=1.75, 95% CI 1.14–2.69) of having visited a health care provider in the previous 12 months than women who had never been in drug treatment. Model 4 was compared to Model 3 and the inclusion of the vulnerable domain variables (Model 4) provided a better fit for the data.

Need

Models 5 and 6 included the traditional need variable (Model 5) of self-reported health status as well as the vulnerable need variables (Model 6). The results appear in Table 4. Women reporting good health had higher odds (OR= 1.95, 95% CI 1.15–3.31) of seeking health care in the previous 12 months as women who reported “excellent/very good” health. Age (p<.05), education (p<.05), and income from public assistance (p<.01), Social Security (p<.01), and a spouse, family member, or friend (p<.01) were the demographic characteristics associated with health care utilization when accounting for self-rated health. Since the variables in Model 1 are nested in Model 5, the models were compared, and Model 5 was a better fit for the data.

In Model 6, the vulnerable need variables were added to the traditional need variable to predict health care utilization. In addition to self-reported health status, women who had been diagnosed with a mental condition by a doctor (OR1.75, 95% CI 1.14–2.70) and reported being HIV positive (OR= 2.52, 95% CI 1.26–5.03) had higher odds to have utilized care in the previous 12 months. The demographic variables that were significant remained unchanged from the previous model. Model 6, which included the vulnerable domain variables, fit the data better than the reduced Model 5, which contained only the traditional domain variables.

Results for the final model, Model 7, which included all the independent variables from all domains, also are presented in Table 4. When controlling for all variables and domains, several significant relationships were revealed. In the predisposing vulnerable domain, depressive symptoms were associated with health care utilization. Women who reported more depressive symptoms had higher odds (OR=1.92, 95% CI 1.10–3.33) than women who reported less depressive symptoms of visiting a health care provider in the previous 12 months. In the enabling traditional domain, having a regular source of care remained significant (p<.01). Compared to women who had no regular source of care, women who had a regular source of care had higher odds (OR=6.26, 95% CI 3.70–10.60) of visiting a health care provider in the previous 12 months. In the enabling vulnerable domain, women who had their own car had higher odds (OR=3.23, 95% CI 1.06–9.78) of visiting a health care provider in the previous 12 months than women who did not. In the traditional need domain, women who self-reported “good health” had higher odds (OR=2.32, 95% CI 1.23–4.38) of seeing a health care provider in the previous 12 months than women who did not self-report “good health”. HIV status also continued to predict health care utilization, but this time, women with unknown HIV status had higher odds (OR=2.94, 95% CI 1.00–8.67) of seeking care in the previous 12 months than HIV negative women.

Models 2 (predisposing variables), 4 (enabling variables), and 6 (need variables) were each compared individually to Model 7 to determine if the full model fit the data better than the predisposing, enabling, and need variable models. The full model, Model 7, fit the data better than Models 2 and 6. However, when comparing the full model to Model 4, the enabling variables, the change in the chi-square value and the change in degrees of freedom were not statistically significant (ΔX2=30.51, Δdf=20, p>05). As such, Model 7 did not represent a significant improvement in fit relative to Model 4; therefore, the enabling variables provided the best fit for the data.

Discussion

This study examined the contributions of predisposing, enabling, and need factors as described by Andersen’s Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (1968, 1995) on health care utilization among a highly vulnerable sample of female sex workers. Although there are mixed findings, overall, vulnerable characteristics do seem to help predict health care utilization for this sample of women. However, some of the variables that represent marginalized or vulnerable statuses (depressive symptoms, mental health diagnosis, HIV) actually contribute to the likelihood of visiting a health care professional. The most consistent predictors of health care utilization were having a regular source of care and self-rated health. These represented traditional domain variables and were significant in every model.

Having a consistent or meaningful link or resource for accessing health care facilitates utilization among this group of vulnerable women and determines future utilization behaviors. Our findings resonate with prior research among minority women, which demonstrated underutilization of health care services due to lack of insurance or a regular source of care (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2000; Hargraves and Hadley 2003; Mead et al. 2008). This association was represented by several enabling variables: having a regular source of care, insurance status, or having received any case management or drug treatment services (Stein, Andersen, and Gelberg 2007). For vulnerable populations, sometimes a first tier of access, usually in the form of shelter or outreach program, provided the needed entry into necessary care (Hatton 2001). The model that included only these enabling variables (Model 4) was the most efficient model in predicting health care utilization in the previous 12 months. This model had fewer variables than the full model, yet was just as effective predicting health care utilization as the full model. The variable that quantified whether the women had a regular source of care was the most consistent predictor of health care utilization in the models. This variable was significant (p<.01) in every model where it was included (Models 3, 4, and 7). Having a regular health care provider likely represents stability and trust, characteristics that may not be common in the lives of most of these women. For these women, this may be more important than having health insurance, as insurance status no longer predicted utilization in the full model, yet having a regular provider remained significant.

Another example of the strength of this variable can be seen when examining our findings on the receipt of public benefits, which resonate with prior studies among homeless populations (Gelberg, Andersen, and Leake 2000). Receiving social security, disability, welfare, public assistance or food stamps was significant in every model except when accounting for having a regular source of care. Having a regular source of care reduces the effect of receiving public assistance on health care utilization to non-significance. That is, the impact of public assistance for health care utilization is mediated by having a regular source of care.

Several need variables were associated with health care utilization in the models. Self-reported health status was another consistent predictor of health care utilization whenever it was included in a model, although the direction was not as hypothesized. Women who self-reported “good” health were more likely to use health care services than those in “excellent/very good” health. There were no significant differences in utilization between those in “fair/poor” health compared to women in “excellent/very good” health. Although women reporting “fair/poor” health are those in highest “need,” they might consider themselves in fair or poor health precisely because they have not been to see a health care provider recently and are not able to access care. These women may represent those with the fewest links to resources.

Significant need variables that also represented opportunities to be linked to care were HIV status and mental health diagnoses. In our study, women who self-identified as being HIV positive were more linked to services, which is likely attributed to public health efforts that exist to provide care for HIV positive patients. Mental health care diagnosis was also significant in the models. This is consistent with other studies on marginalized populations (Cunningham et al. 2007) and likely represents connection to an institution providing a link to care as the diagnosis of a mental health problem had to be identified by some type of health care provider. Since women were asked only whether a doctor ever diagnosed them with a mental health problem, there is no way to know whether the reason for visiting a doctor in the previous 12 months was for mental health care, or whether the participant was diagnosed by a mental health practitioner who then opened up a link to other health care. What the data do show is that women who had been diagnosed with a mental health problem were more likely to have visited a health care provider in the past year supporting the idea that any contact with a health-related institution may facilitate a link to care.

Linkage to care through HIV diagnosis, mental health diagnosis, and drug treatment suggest that women who have hit “bottom” are more likely to have accessed health care services than women who may be struggling but perhaps have not reached severe levels of substance use or sex work. This was supported by the enabling data models on experiences with drug treatment. Women with previous connection to an institution via drug treatment or through a shelter were considered as having a “resource” or “link” to care. Drug treatment provides case management services and is often inpatient. Many of these programs provide health care through onsite clinics and volunteer health care providers. It is troubling that access to health care seems facilitated by what most would consider desperate situations.

Limitations

Certain limitations must be considered before drawing any final conclusions based on these findings. First, the data analyzed were cross-sectional data using targeted and snowball sampling. The study does not assume to be representative of all Black, substance using, sex workers in Miami. There may be sample selection bias due to the sampling strategies used to find this hidden population. The women included in this sample were women working the “strolling” areas of Miami, where sex workers work on the streets. There are other sex workers found in more organized locations or under the control of a pimp that were likely not included in this sample and would have required different sampling techniques. However, the sample size is large (n=546) which helps increase the potential for generalizability of the findings.

Some of the data collected were sensitive in nature and difficult to answer. Data on behaviors and health status were self-reported, increasing the possibility of reporting bias. To counteract this, all interviewers were trained extensively and were taught the importance of being non-judgmental, building rapport, and making the participants feel comfortable. Interviewers reinforced the importance of answering honestly and reminded participants of the voluntary nature of participation as well as the strict confidentiality of the data.

Temporal sequence is an issue with cross-sectional studies. Women answered “yes” or “no” to whether they had seen a health care provider in the twelve months prior to being interviewed. Data were not available on exactly when the woman utilized health care within those 12 months.

Conclusions

Andersen’s Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations proved useful in examining the health care utilization behaviors of this vulnerable group of women. Vulnerable domains contributed to predicting health care utilization behaviors, particularly the variables within the enabling and need characteristics. The enabling characteristics in both the traditional and vulnerable domains were particularly efficient in predicting health care utilization for these women. Andersen (1995) defined enabling variables as representing a measure of access to health care; a sign of inequitable access is when these variables determine who receives health care. Results of the multivariate models revealed that this access was the most significant predictor of utilization for this sample of women.

The data showed that a regular source of health care was critical to future utilization for these women. Resources, links, any type of connection to or with an institution, or any consistent point of care contribute significantly to these women’s health care behaviors. Although Andersen’s model attempts to account for structural elements by including variables that may represent structural inequities, the process by which structural inequities impact health care utilization cannot be fully captured with this model. Demographic, social, and economic quantifiable characteristics of health care utilization are accounted for, but are unable to capture the actual process of seeking out health care or the meaning of the process for these women. To better understand the context in which these women seek health care, future research should focus on the processes of seeking and utilizing care.

Implications for Practice and Policy

For these vulnerable women, a stable source of health care is more important to future utilization than insurance. Even connecting to health care through an HIV diagnosis or a drug treatment program may be considered stable care for a vulnerable population. Efforts to assist vulnerable populations with obtaining consistent health services prior to the onset of a serious life event may not only improve health care utilization, health status and quality of life among these women, but also provide a mechanism for preventative care before their health problems become severe and difficult to manage.

These findings suggest the need for structural level interventions that would connect women more efficiently and equitably to resources in order to increase consistency and dependability of access and care. Overall, these women represent other vulnerable populations that likely experience similar struggles when trying to seek health care. This research provides information on how to better serve those in greatest need in society for the benefit of public health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant # R01DA013131 from the National Institute Drug Abuse. NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of this report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- Aday Lu Ann. Health Status of Vulnerable Populations. Annual Review of Public Health. 1994;15:487–509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care” Fact Sheet. AHRQ Publication No 00-PO41. 2000 http://www.ahrq.gov/research/disparit.htm.

- Andersen Ronald M. Behavioral Models of Families’ Use of Health Services. Chicago, IL: Center for Health Administration Studies, University of Chicago; 1968. Research series number 25. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen Ronald M. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Care: Does it Matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters Jennifer, Erickson Patricia. Meeting the Health Care Needs of Female Crack Users: A Canadian Example. Women and Health. 2003;37:1–17. doi: 10.1300/J013v37n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham Chinazo O, Sohler Nancy L, Wong Mitchell D, Relf Michael, Cunnigham William E, Drainoni Mari-Lynn, Bradford Judith, Pounds Moses B, Cabral Howard D. Utilization of Health Care Services in Hard-to-Reach marginalized HIV-infected Individuals. AIDS Patient Care. 2007;21(3):177–186. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis Michael L, Titus JC, White MK, Unsicker JI, Hodgkins D. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs - Initial (GAIN-I) Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis Michael L, Chan Ya-Fen, Funk Rodney. Development and Validation of the GAIN Short Screener (GSS) for Internalizing, Externalizing and Substance Use Disorders and Crime/Violence Problems Among Adolescents and Adults. American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15(S1):80–91. doi: 10.1080/10550490601006055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg Lillian, Andersen Ronald, Leake Barbara. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: Application to Medical Care Use and Outcomes for Homeless People. Health Services Research. 2000;34(6):1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargraves J Lee, Hadley Jack. The Contribution of Insurance Coverage and Community Resources to Reducing Racial/ethnic Disparities in Access to Care. Health Services Research. 2003;38(3):809–830. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton Diane C. Homeless Women’s Access to Health Services: A Study of Social Networks and Managed Care in the US. Women & Health. 2001;33(3/4):149–162. doi: 10.1300/J013v33n03_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: What Healthcare Providers Need to Know About Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health-Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz Steven P, Surratt Hilary L, Kiley Marion C, Inciardi James A. Barriers to Health and Social Services for Street-based Sex Workers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2005;16:345–361. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus L, Chettiar J, Deering K, Nabess R, Shannon K. Risky health environments: Women sex workers’ struggles to find safe, secure and non-exploitative housing in Canada’s poorest postal code. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;73:1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead Holly, Cartwright-Smith Lara, Jones Karen, Ramos Christal, Woods Kristy, Siegel Bruce. The Commonwealth Fund. 2008. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in U.S. Healthcare: A Chartbook; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- O’Daniel Alyson J. Access to Medical Care is Not the Problem: Low-Income Status and Health Care Needs Among HIV-Positive African-American Women in Urban North Carolina. Human Organization. 2011;70:416–426. [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne Cathy D, Stewart Anita L. The MOS Social Support Survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein Judith A, Andersen Ronald, Gelberg Lillian. Applying the Gelberg-Andersen behavioral model for vulnerable populations to health services utilization in homeless women. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(5):791–804. doi: 10.1177/1359105307080612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt Hilary L, Inciardi James A. HIV Risk, Seropositivity and Predictors of Infection among Homeless and Non-Homeless Women Sex Workers in Miami, Florida, USA. AIDS Care. 2004a;16(5):594–604. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001716397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt Hilary L, Kurtz Steven P, Weaver Jason C, Inciardi James A. The Connections of Mental Health Problems, Violent Life Experiences, and the Social Milieu of the ‘Stroll’ with the HIV Risk Behaviors of Female Street Sex Workers. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 2005;17:23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Watters John, Biernacki Patrick. Targeted Sampling: Options for the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1989;36(4):416–430. [Google Scholar]