Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Surrogacy arrangements are multifaceted in nature, involving multiple controversial aspects and engaging ethical, moral, psychological and social issues. Successful treatment in reproductive medicine is strongly based on the mutual agreement of both partners, especially in Iran where men often make the final decision for health-related problems of this nature. AIM: The aim of the following study is to assess the attitudes of Iranian infertile couples toward surrogacy.

SETTING AND DESIGN:

This descriptive study was conducted at the infertility clinic of Hamadan university of medical sciences, Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The study sample consisted of 150 infertile couples selected using a systematic randomized method. Data collection was based on responses to a questionnaire consisting of 22 questions.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

P <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS:

While 33.3% of men and 43.3% of women surveyed insisted on not using surrogacy, the overall attitudes toward surrogacy were positive (53.3% of women and 54.6% of men surveyed).

CONCLUSION:

Although, there was not a significant difference between the overall positive attitudes of infertile women and men toward surrogacy, the general attitude toward using this method is not strongly positive. Therefore, further efforts are required to increase the acceptability of surrogacy among infertile couples.

KEY WORDS: Attitude, infertility, surrogacy

INTRODUCTION

Infertility is generally defined as 1 year of unprotected intercourse without resulting in conception.[1] According to a study conducted by the World Health Organization in 2004, 187 million couples in 47 developing countries (excluding China), were affected by infertility.[2] Similarly, a population-based survey has shown prevalence of 8% among couples in our country.[3] Many people believe that having a child would be one of the most wonderful and memorable events in their lives.[4] Infertility, as a stressful life crisis, may thus have a devastating effect on a person's mental health and may negatively impact the lives of affected couples.[5] Indeed, some studies have indicated that infertility would be the most upsetting experience for most women and a proportion (15%) of affected men.[4,5] Overall, while evaluation and treatment protocols have considerably improved,[6,7] the overall incidence of infertility has not changed over the past 30 years. Surrogacy is a form of assisted reproductive treatment (ART) in which a woman conceives and carries a child in her uterus for an infertile person or couple, and then gives the child to that person or couple.[8,9] Surrogacy arrangements involve many controversial aspects and engage ethnical, moral, psychological and social issues.[10,11,12] Successful treatment in reproductive medicine is greatly based on the agreement of both partners,[7] especially in middle eastern countries such as Iran, where men often make the final decision. However, there are few studies on the general opinion of both women and men about surrogacy.

Thus, considering the importance of a comprehensive study regarding the attitudes of infertile couples toward surrogacy, we gathered relevant information from affected men and women in a city located in the west of Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This descriptive study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences and the Fatemiyeh infertility center in which we conducted the study. We evaluated 150 infertile couples (150 women and 150 men) being treated for infertility at the infertility center between 2010 and 2011. Inclusion criteria included: Signed informed consent to take part in the study; living in the same province; not currently using surrogacy; and completing the questionnaire. Potential subjects were excluded from the study based on a known history of active mental disorders and/or the occurrence of a stressful event in the 6 months prior to the study. The research participants were selected by a systematic randomized method and their anonymity was maintained. A total of 300 persons (150 couples) agreed to participate in this study. Data collection was based on a questionnaire filled out by the study participants. Written approval forms were taken from all participants before distributing questionnaires. The questionnaire was designed based on related published studies,[5,7,8,13,14] and was evaluated by 10 expert professors from four different medical universities in Iran before being used. The test-retest reliability of the questionnaire was established using Cronbach's alpha coefficient (0.89) following a pilot study on a sample of 25 infertile women. The questionnaire form consisted of two parts with 22 questions: A: Demographic test questions (5 items), B: Attitude test questions (17 items).

Two of the researchers were involved in data collection. All participants were asked to provide demographic information including sex, age, education level, religion and previous information about surrogacy. Necessary information about gestational surrogacy was given to all study subjects before collecting data regarding attitudes toward surrogacy. For illiterate study participants, the interviewer read the questions out loud and a relative filled in the participant's responses. The following scoring system was designed based on the responses to the statements in the questionnaire: Agree (4 points), disagree (1 point) and no idea (2 points). Participants' overall attitude toward surrogacy was considered negative if the score was below 34 points (inclusive) and positive if the score was at least 35. The collected information was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 software. Descriptive analytical spearman tests and statistical Chi-square tests were used for comparing the attitudes of infertile women and men. P < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

All participants were Shiite Muslim, and the mean age of infertile women and infertile men were 26.9 ± 5.8 years and 35 ± 5.2 respectively. 2 women (1.3%) were illiterate, 58 women (38.6%) and 52 men (34.6%) had up to primary school education level. 50 women (33.3%) and 63 men (42%) had a high-school diploma and 40 women (26.6%) and 35 men (23.3%) had university degrees. 50 women (33.3%) and 57 men (38%) had previous information about surrogacy. There were no significant differences between the two gender groups of the study participants with regards to their average age (P = 0.2), level of education (P = 0.15), or previous information about surrogacy (P = 0.1).

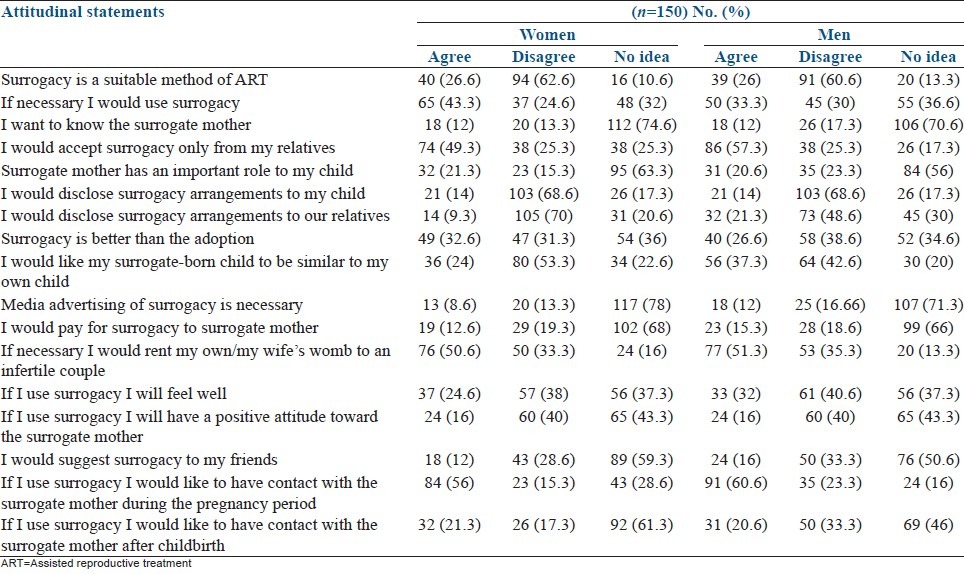

Infertile couples' responses to each item of the questionnaire and their overall attitude toward surrogacy are presented in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

Table 1.

Attitudes of Iranian infertile couples toward surrogacy

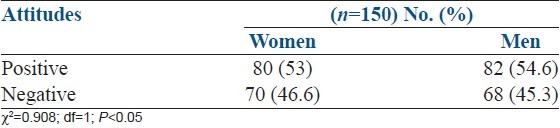

Table 2.

Relationship between gender and overall attitude toward surrogacy

According to Chi-square test results, there was no significant difference in the overall positive attitudes between infertile women and men toward surrogacy (P < 0.05) [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study performed in order to determine the opinions and attitudes of infertile Iranian women and men toward surrogacy in our country.

We found no significant differences between the two gender groups of the study with regards to the average age, level of education, or previous information about surrogacy. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the overall attitudes between infertile women and men toward surrogacy. To compare our findings with other related reports, we discuss selected statements from the questionnaire regarding the participants' attitudes toward surrogacy.

If necessary, I would use surrogacy

In our study, 26.6% of infertile women and 26% of infertile men considered surrogacy as a suitable ART method. Shirai has shown that 24% of infertile females and 40% of infertile males approved of gestational surrogacy[15] while Nagata et al. (discussed by Saito and Matsuo[13] ) showed in 1992 that 45% of both infertile women and men agreed with gestational surrogacy.[16] Unlike these previous studies, our overall rates (26%) in both women and men accepting surrogacy as a suitable method of ART were lower. Furthermore, we did not see any differences between the gender groups. Interestingly, we found that a greater proportion of infertile individuals would actually use gestational surrogacy if it were necessary: 33.3% and 43.3% of infertile men and women, respectively. These rates were considerably lower in the study reported by Saito and Matsuo, which indicated that only 10% of women and 23% of men among infertile couples would accept using gestational surrogacy as an inevitable method.[13] Furthermore, our study showed that women had a more positive attitude toward surrogacy arrangements than did men, among infertile couples.

I would accept surrogacy from relatives

We found that almost half of the participants (49.3% in women and 57.3% in men) would rather have a surrogate mother from among their relatives while just over a quarter (25.3%) of the couples surveyed preferred the identity of the surrogate to remain unknown. Kilic et al. previously found that 43% of Turkish infertile women preferred to have a sister or close friend to be a surrogate mother and only 13.33% of their subjects preferred to have an unknown or anonymous surrogate.[14] In contrast, Saito and Matsuo has reported that 70% of Japanese women and men in infertile couples favored to receive an unknown surrogate uterus.[13] Our results are not consistent with Yoshiko's study but rather are more similar to Kilic's results, which may be due to a greater similarity in religious and cultural views between Turkey and the country in which our study was conducted. In addition, the present study reveals that more Iranian infertile men than women would prefer to have a blood-related child by having a relative as a surrogate, which may potentially be associated with the personalities and perspectives of men.

I would disclose surrogacy arrangements to my child

We found that 68.6% of infertile women and 56.6% of infertile men would be likely to inform children born using surrogacy about his/her origin. Similarly, Rahmani et al. reported that 67.2% of Iranian infertile women in Tabriz city (in north-west of Iran) would prefer to disclose surrogacy arrangements to their child[17] and Svanberg et al. indicated the preference of infertile women to inform their child (ren) about the oocyte donor, based on a public opinion survey on oocyte donation in Sweden.[18] However, the results of previous studies carried out in the same country suggest an opposite trend, which could be due to the differing beliefs and traditions of different regions, despite subjects living in the same country and having the same religion. The desire infertile women have to disclose surrogacy arrangements to their potential child (ren) could be related to their inability to have a normal pregnancy, resulting in them turning to gestational surrogacy and oocyte donation. Furthermore, if children were told the truth by relatives or friends or discovered it through other means, they could be perceived to eventually consider their mothers as "guilty." Thus, telling the truth to the surrogate-born children themselves would make mothers feel more self-confident about such an arrangement.

Surrogacy is better than adoption

In our study, 32.6% of infertile women and 26.6% of infertile men believed that surrogacy would be better than adoption, while 34.6% of infertile women and 36% of infertile men were uncertain about either option. Rahmani et al. found that 67.2% of Iranian infertile women preferred surrogacy to adoption.[17] In contrast, Kilic et al. have reported that 59.6% of Turkish infertile women preferred to arrange an adoption and only 24% of them accepted gestational surrogacy.[14] It is generally considered worthy to adopt a child in all cultures and most people around the world are familiar with this method of building a family. However, it will most likely take time for surrogacy to be considered as an option to the same extent as adoption. Considering the increase in the proportion of men and women who would use surrogacy when presented as a general ART method compared to when presented as a necessary method (26.6% and 26% to 33.3% and 43% of women and men respectively), it appears that the more knowledge infertile couples have about gestational surrogacy and its future outcomes would encourage them to make more informed decisions about using various ART methods, including surrogacy.

If necessary I would rent my own/my wife's womb to an infertile couple

In our study, nearly half of both infertile women and men agreed with potentially renting their own/their wife's womb to another infertile couple. In comparison, only 5.3% of Turkish women were willing to act as a surrogate mother,[19] with 73.1% of the women who participated in the study indicating they would not serve as a surrogate mother.[20] One reason for such discrepancy with our study could be that since the participants of the latter study by Chiliatokis et al. were selected from general society, they did not have any particular sympathy for infertile couples as in our study. Moreover, infertile women, as in our study, might not consider such a question to the same extent fertile women would.

If I use surrogacy I would have a relationship with the surrogate mother during pregnancy period/after birth

We found that 56% of infertile women and 60.6% of infertile men surveyed were would be inclined to stay in touch with a surrogate mother during the pregnancy period, although the majority would prefer to not continue the relationship with the surrogate mother after birth of the child (61.3% of women and 69% of men). The relationship between surrogate and intended mothers has already been described by Pashmi et al., showing the existence of regular and good relations between most surrogate and intended mothers until the birth of the child.[21] In addition, MacCallum et al. showed that there was a strong feeling among intended mothers to establish a regular relationship with surrogate mothers, in order to render future beneficial effects to the surrogate-born child.[8]

Overall attitudes of Iranian infertile women and men toward gestational surrogacy

As shown in Table 2, the present study showed no significant differences between the overall positive attitudes of infertile women (53.3%) and infertile men (54.6%) (χ2 = 0.908 df = 1 P < 0.05) toward surrogacy. A previous study reports that 95%, of infertile couples surveyed have an overall negative attitude concerning this method of ART[22] while another reports that 89.9% of infertile women in Iran have a positive attitude toward gestational surrogacy.[17] The results of our study do not show as strong a position for or against surrogacy as do these previous studies. However, these studies do differ in various aspects. For instance, it should be noted that Rahmani et al. surveyed only infertile women[17] whereas we evaluated the perspectives of both women and men. Importantly, reproductive medicine is greatly dependent on both husband and wife, and couples considering such treatment may affect and moderate one anothers' opinions in making such an important decision. In addition, culture, religion and social status may have an important impact - for instance, Kilic et al. showed that only 24% of infertile Turkish women had a positive attitude concerning gestational surrogacy,[14] in contrast to the results of the study conducted by Rahmani et al.[17] It is clear that the results of such studies must be carefully evaluated considering the makeup of the subject pool the cultural and religious background, and degree of education regarding surrogacy, among other factors.

Our study has some limitations to be considered. First, the questionnaires were handed out to both husband and wife; while participants were instructed to answer questions independently, it cannot be confirmed whether the questions were answered by individual participants alone without input from their spouse. Second, this study focused on assessing the viewpoint of infertile women and men toward surrogacy, but did not assess the views of fertile women or men. An important advantage of the present study is simultaneously assessing the views of the husbands of the infertile women, which is particularly important to consider in Middle Eastern cultures where men often make the health-related decisions in the family.

CONCLUSION

While the overall attitudes of Iranian infertile women and men surveyed in our study tend to be positive, surrogacy is not yet strongly considered by either sex as a form of ART to be used. If the acceptability of using surrogacy is to increase, further efforts are required to increase the knowledge and understanding about this method. This would be required not only at the level of educating infertile couples, but also at the level of the general population in order to create a general understanding - and acceptance - of surrogacy as a suitable method not only to be considered and used by infertile couples, but also to have willing fertile women to act as surrogate mothers, and to support couples who do choose to use this method in order to build their own family. Thus, it would also be interesting to expand the study to examine the attitudes, understanding and acceptance of the general public toward using gestational surrogacy, and potentially other forms of ART as well, in order to create a more complete understanding of how gestational surrogacy is perceived and to subsequently come up with methods of increasing public understanding and acceptance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Appreciation goes to the deputy of research of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences for their financial support. We would like to thank Alma N. Mohebiany for the critical reading and editing of this article. The authors would like to thank all the couples who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study has been done by the scientific and financial support of ethics and medical history research center of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berek JS. Berek and Novak's Gynecology. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Women and health: Today's evidence, tomorrow's agenda. World Health Organization. 2009. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 25]. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563857_eng.pdf .

- 3.Safarinejad MR. Infertility among couples in a population-based study in Iran: Prevalence and associated risk factors. Int J Androl. 2008;31:303–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kainz K. The role of the psychologist in the evaluation and treatment of infertility. Womens Health Issues. 2001;11:481–5. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(01)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poote AE, van den Akker OB. British women's attitudes to surrogacy. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:139–45. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speroff L, Fritz MA. Clinical Gynecology Endocrinology and Infertility. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minai J, Suzuki K, Takeda Y, Hoshi K, Yamagata Z. There are gender differences in attitudes toward surrogacy when information on this technique is provided. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;132:193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacCallum F, Lycett E, Murray C, Jadva V, Golombok S. Surrogacy: The experience of commissioning couples. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1334–42. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sills ES, Healy CM. Building Irish families through surrogacy: Medical and judicial issues for the advanced reproductive technologies. Reprod Health. 2008;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner DK, Weissman A, Howles CM, Shoham Z. Textbook of Assisted Reproductive Techniques: Laboratory and Clinical Perspectives. 1th ed. London: Informa Healthcare; 2004. pp. 855–65. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ber R. Ethical issues in gestational surrogacy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2000;21:153–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1009956218800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciccarelli JC, Beckman LJ. Navigating rough waters: An overview of psychological aspects of surrogacy. J Soc Issues. 2005;61:21–43. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-4537.2005.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito Y, Matsuo H. Survey of Japanese infertile couples' attitudes toward surrogacy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;30:156–61. doi: 10.1080/01674820802429435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilic S, Ucar M, Yaren H, Gulec M, Atac A, Demirel F, et al. Determination of the attitudes of Turkish infertile women toward surrogacy and oocyte donation. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25:36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirai Y. Japanese attitudes toward assisted procreation. J Law Med Ethics. 1993;21:43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1993.tb01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagata Y, Ichikawa Y, Okada H, Kyouno H, Sato E, Sato K, et al. (Ethical Japan Society of Fertilization and Implantation). Views of infertile patients on assisted reproductive technologies for extra-marital state (in Japanese) J Fert Implant (Tokyo) 2004;21:6–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahmani A, Sattarzadeh N, Gholizadeh L, Sheikhalipour Z, Allahbakhshian A, Hassankhani H. Gestational surrogacy: Viewpoint of Iranian infertile women. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2011;4:138–42. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.92288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svanberg AS, Lampic C, Bergh T, Lundkvist O. Public opinion regarding oocyte donation in Sweden. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1107–14. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baykal B, Korkmaz C, Ceyhan ST, Goktolga U, Baser I. Opinions of infertile Turkish women on gamete donation and gestational surrogacy. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:817–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chliaoutakis JE, Koukouli S, Papadakaki M. Using attitudinal indicators to explain the public's intention to have recourse to gamete donation and surrogacy. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2995–3002. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.11.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pashmi M, Tabatabaaie MS, Ahmadi A. Evaluating the experience of surrogate and intended in terms of surrogacy in Isfahan. Iran J Reprod Med. 2010;8:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sohrabvand F, Jafarabadi M. Knowledge and attitudes of infertile couples about assisted reproductive technology. Iran J Reprod Med. 2005;3:90–4. [Google Scholar]