Abstract

Eph receptor protein-tyrosine kinases are among the oldest known animal receptors and have greatly expanded in number during vertebrate evolution. Their complex transduction mechanisms are capable of bidirectional and bimodal (multi-response) signaling. Eph receptors are expressed in almost every cell type in the human body, yet their roles in development, physiology, and disease are incompletely understood. Studies in C. elegans have helped identify biological functions of these receptors, as well as transduction mechanisms. Here we review advances in our understanding of Eph receptor signaling made using the C. elegans model system.

1. Introduction

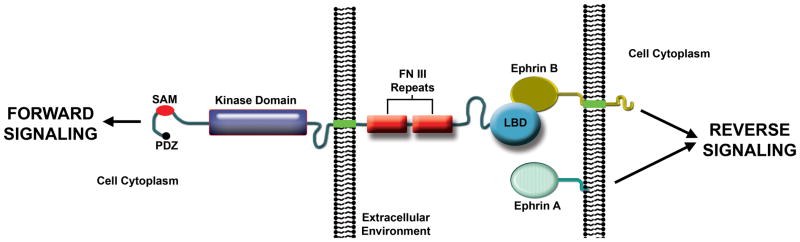

Eph receptors (EphRs) are the largest subfamily of receptor protein-tyrosine kinases in vertebrates, with fourteen members encoded in the human genome (Pasquale, 2010: PMID20179713; Pitulescu and Adams, 2010: PMID21078817). The name Eph is for Erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular carcinoma cell line from which the first cDNA was isolated (Hirai et al., 1987: PMID2825356). EphRs are divided into A and B subclasses. Both contain an N-terminal ligand binding domain, which folds into a compact “jellyroll” β-sandwich (Himanen et al., 1998: PMID9853759), followed by a cysteine-rich region, two fibronectin type III repeats, transmembrane-spanning domain, tyrosine kinase domain, sterile α motif (SAM), and PDZ-binding motif at the C-terminus (Fig. 1). Several years after the discovery of EphRs, membrane-associated ligands called ephrins were identified (Bartley et al., 1994: PMID8139691; Davis et al., 1994: PMID7973638). A-type ephrins are glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored, whereas B-types have a single transmembrane domain (Fig. 1). The human genome encodes five A-type and four B-type ephrins. In general, the A-types bind with high affinity to EphA class receptors and the B-types bind with high affinity to EphB class receptors. However, there is evidence for cross-class binding. Ephrin binding to EphRs induces bidirectional signaling into the receptor-expressing cell, which is called “forward signaling”, and the ligand-expressing cell, which is called “reverse signaling” (Pasquale, 2010: PMID20179713; Pitulescu and Adams, 2010: PMID21078817). Thus, ephrins are also capable of signal transduction (Fig. 1). EphR homologs are present in the earliest-diverging animals, making them among the oldest evolutionarily conserved receptors (Chapman et al., 2010: PMID20228792; Srivastava et al., 2010: PMID20686567).

Figure 1. Vertebrate Eph receptor structure and signaling.

Ephrin-induced EphR clustering, autophosphorylation, and association of EphR intracellular domains with signaling effectors triggers “forward” signaling. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho family GTPases couple forward signals to the actin cytoskeleton. The transmembrane domain-containing B-type ephrins transmit “reverse” signals, whereby the EphR extracellular domain functions as a ligand. GPI-linked A-type ephrins are thought to transmit reverse signals, but the mechanism is not well understood (Arvanitis and Davy, 2008: PMID18281458; Pasquale, 2008: PMID18394988; Pitulescu and Adams, 2010: PMID21078817). LBD, ligand binding domain; FN III, fibronectin type III; SAM, sterile alpha motif; PDZ, post synaptic density protein/Drosophila disc large tumor suppressor/zonula occludens-1 protein domain binding.

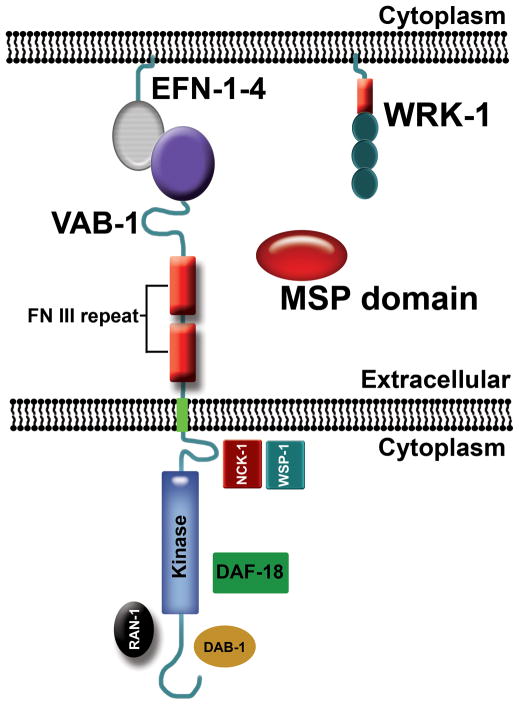

In contrast to vertebrate genomes, the C. elegans genome encodes a single EphR called VAB-1 (Fig. 2), which is equally similar to EphA and EphB receptors (George et al., 1998: PMID9506518). It also encodes four GPI-anchored ephrins with sequences more similar to vertebrate B-type than A-type ephrins (Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431; Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316). Studies in C. elegans have provided valuable insight into the biological functions of EphRs, as well as into their transduction mechanisms. This review focuses on the contributions of these studies to our understanding of EphR signaling.

Figure 2. C. elegans Eph receptor signaling showing proteins that directly interact with VAB-1.

The genome encodes one Eph receptor called VAB-1, four GPI-linked ephrins called EFN-1 to EFN-4, and numerous proteins with MSP domains (George et al., 1998: PMID9506518; Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431; Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316; Tarr and Scott, 2005: PMID15837611). MSP domains directly interact with the VAB-1 extracellular domain and can function as ephrin antagonists, as well as signal independent of ephrins (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Govindan et al., 2006: PMID16824915; Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774; Chen and Chan, 2009: PMID19808793). The VAB-1 intracellular domain directly interacts with the Disabled homolog DAB-1 (Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420), Ran GTPase RAN-1 (Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420), PTEN homolog DAF-18 (Brisbin et al., 2009: PMID19853560), and a complex containing the NCK-1 adaptor protein and WSP-1 WASP homolog (Mohamed et al., 2012: PMID22383893).

2. Genetic identification of variable abnormal (Vab) genes

The first Eph receptor and ephrin mutants were isolated by Sydney Brenner in his initial EMS mutagenesis screens for visible mutants (Brenner, 1974: PMID4366476). One class called “abnormal” mutants had a common variable abnormal (Vab) phenotype characterized by a split or notched head. Multiple alleles for vab-1 and vab-2 were isolated and vab-1(e2) and vab-2(e96) were kept as reference mutants. Most mutants with Vab phenotypes (including vab-1 and vab-2) were not further analyzed and it was over 20 years later that the molecular identities for vab-1 and vab-2 were discovered. The vab-1(e2) allele is a point mutation that abolishes kinase activity (George et al., 1998: PMID9506518), whereas vab-2(e96) truncates the GPI anchor signal of the EFN-1 ligand (Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431). The mab-26(bx80) (male abnormal) allele was identified in screens for mutants with defective male tail morphogenesis (Chow and Emmons, 1994: PMID7956833) and later shown to encode the EFN-4 ligand (Chin-Sang et al., 2002: PMID12403719). The two other ephrins were identified using a reverse genetics approach (see below).

The incompletely penetrant and variably expressed nature of vab mutants has provided clues to the mechanisms by which animals develop. vab genes encode proteins involved in a diverse array of biochemical functions. In general, mutations in these genes cause patterning defects during embryonic development that often manifest as incompletely penetrant head and tail abnormalities. While partial redundancy among pathways governing these developmental processes is one explanation for variability and incomplete penetrance of the mutant alleles, there may also be another (not necessarily mutually exclusive) answer. “Hub” genes, which encode chromatin modifiers, have been proposed to act as buffers for genetic variation among unrelated processes (Lehner et al., 2006: PMID16845399). RNAi of these hub genes can increase the frequency of the notched head phenotype in vab-1 mutants. Thus, hub genes may maintain robust biological outcomes despite variations in EphR signal strength.

3. Overview of VAB-1 EphR signal transduction

The conventional mode of receptor protein-tyrosine kinase activation is ligand-induced receptor dimerization and transphosphorylation, leading to the recruitment of phosphotyrosine binding domain proteins that initiate intracellular transduction cascades. While EphRs transduce signals by this mechanism, there are additional features that diversify cellular responses. First, ephrin and EphR interactions can form heteromers with different stoichiometries (Himanen et al., 2001: PMID11780069; Smith et al., 2004: PMID14660665). Higher order structures are thought to activate different downstream effectors relative to lower order structures (Stein et al., 1998: PMID9499402; Hansen et al., 2004: PMID15182713; Wimmer-Kleikamp et al., 2004: PMID14993233). Second, kinase activation is not absolutely required for signaling (George et al., 1998: PMID9506518; Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431; Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316; Gu and Park, 2001: PMID11416136). Finally, ephrin/EphR interactions can transduce bidirectional signaling in forward and reverse directions. These features are reviewed in detail elsewhere (Arvanitis and Davy, 2008: PMID18281458; Pasquale, 2010: PMID20179713; Pitulescu and Adams, 2010: PMID21078817).

In C. elegans, genetic and biochemical studies suggest that the VAB-1 EphR has all the features of its vertebrate counterparts (Fig. 2). However, C. elegans has contributed to the field the most in the identification of EphR biological functions and signal transduction mechanisms. These contributions are discussed in the following sections.

3.1 Ligands

C. elegans ephrins are called EFN-1/VAB-2, EFN-2, EFN-3, and EFN-4/MAB-26. efn-1 was identified as the vab-2 gene when an ephrin-like sequence mapped to the vab-2 locus (Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431). efn-2, efn-3, and efn-4 were identified by BLAST searches against the C. elegans genome (Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316). Each ephrin contains a predicted signal peptide for secretion, followed by a conserved ~130 amino acid receptor binding domain, and a C-terminal GPI anchor sequence (Fig. 2). EFN-4 contains a 24 amino acid insert within the receptor binding domain. C. elegans ephrins are more similar in the receptor binding domain to vertebrate B-type ephrins (37%–40% identical) than A-type ephrins (26%–30% identical), yet they contain a GPI anchor instead of a transmembrane domain. The sole Drosophila ephrin contains a transmembrane domain (Boyle et al., 2006: PMID16613832), whereas an ephrin in the moth Manduca sexta is GPI-anchored (Kaneko and Nighorn, 2003: PMID14684856). Both are more similar in sequence to B-type vertebrate ephrins. Thus, GPI-anchoring or transmembrane sequences may have arisen multiple times in ephrin evolution.

EFN-1 binds to the VAB-1 EphR extracellular domain with high affinity (Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431). EFN-2 and EFN-3 are also likely bind with high affinity, although the affinity has not been directly measured (Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316). On the other hand, EFN-4 appears to have reduced affinity (Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316). Multiple lines of evidence support the hypothesis that EFN binding is critical for VAB-1 function in vivo. First, VAB-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in vivo requires its ligand-binding domain and ephrins (Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316). Second, mutations that reduce the affinity of EFN-1 for VAB-1 have reduced activity (Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431). Finally, genetic interactions between efn and vab-1 mutations are consistent with these genes acting in a common pathway (Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431; Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316). One exception is EFN-4. Mutations in efn-4 and vab-1 exhibit synergy, suggesting that EFN-4 can transduce signals through another receptor (Chin-Sang et al., 2002: PMID12403719). Nevertheless, multiple ephrins can interact with VAB-1 to transduce signals.

Another GPI-linked protein called WRK-1 (Wrapper/Rega-1/Klingon homolog) has been identified that modulates VAB-1 signal transduction (Fig. 2). WRK-1 is an immunoglobulin-containing cell surface protein that physically and genetically interacts with VAB-1 and EFN-1 (Boulin et al., 2006: PMID17027485). WRK-1 and VAB-1 signaling appears to occur specifically during axon guidance at the ventral midline. Whether the physical interaction with VAB-1 (or EFN-1) occurs in cis or trans is not yet clear, but phenotypic rescue experiments suggest that WRK-1 and VAB-1 interact between cells in apposition. While ephrins and WRK-1 are both GPI-linked, they are unrelated in sequence.

VAB-1 can also bind to a diffusible class of ligands (Fig. 2) and this interaction appears to be conserved in nematodes, arthropods, and mammals (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Govindan et al., 2006: PMID16824915; Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774). The discovery that major sperm protein (MSP) domains bind to EphRs was first made in the C. elegans gonad. Prior to fertilization, C. elegans sperm secrete MSPs to stimulate oocyte maturation and ovarian sheath cell contraction, which together facilitate ovulation (Miller et al., 2001: PMID11251118). An MSP binding screen identified VAB-1 as a potential receptor (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508). Biochemical experiments have demonstrated that VAB-1 is a bona fide MSP receptor, although coreceptors or cofactors may enhance binding affinity. Binding and genetic data indicate that there are additional MSP receptors expressed in the proximal gonad. MSP binding to VAB-1 antagonizes ephrin-dependent and ephrin-independent signal transduction (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420; Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774). Thus, MSP is an ephrin antagonist that can also signal through VAB-1 independent of ephrins.

The MSP domain is an evolutionarily conserved ~120 amino acid immunoglobulin-like fold found in an array of proteins (Tarr and Scott, 2005: PMID15837611; Han et al., 2010: PMID20034089). The VAPs (VAMP/synaptobrevin-associated proteins) are the ancestral family from which MSP domain-containing proteins derive. VAPs are type II membrane proteins with the C-terminus anchored in the endoplasmic reticulum. At the N-terminus is a single MSP domain followed by a coiled-coil motif and transmembrane-spanning region (Lev et al., 2008: PMID18468439). VAP MSP domains are cleaved from the transmembrane domain in the cytosol and secreted into the extracellular environment (Fig. 2), where they bind to multiple growth cone guidance receptors, including EphRs (Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774; Lua et al., 2011: PMID22069488; Han et al., 2012: PMID22264801). MSP domains are secreted by an unconventional mechanism in a cell-type specific fashion (Kosinski et al., 2005: PMID15975936; Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774). Biochemical studies with mammalian proteins have shown that VAP MSP domains compete with ephrins for EphR binding (Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774). Moreover, the MSP domain from C. elegans VPR-1 (VAP-Related) binds to the VAB-1 extracellular domain (Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774). In contrast to MSPs, which are expressed specifically in sperm (Klass and Hirsh, 1981; Ward and Klass, 1982: PMID7049792), VPR-1 is broadly expressed (Han et al., 2012: PMID22264801). The most parsimonious scenario is that early in nematode evolution an MSP gene was created from a duplicated VAP gene that lost the coiled coil and transmembrane domains. This MSP gene acquired sperm-specific expression and retained its hormonal function. A P56S mutation in the human VAPB MSP domain is associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and late-onset spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), two neurodegenerative diseases that affect motor neurons (Nishimura et al., 2004: PMID15372378). Thus, MSPs may be the founding members of a new class of secreted hormones that are important for human motor neuron survival.

3.2 Downstream pathways

Genetic and biochemical approaches have been used to identify downstream mediators of VAB-1 EphR signaling (see Table 1 for summary). VAB-1 is expressed in oocytes, where it functions as a modest negative regulator of oocyte maturation (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420; Brisbin et al., 2009: PMID19853560). Sperm-derived MSPs antagonize VAB-1 activity to help stimulate this process. A critical downstream event is activation of the conserved mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (Miller et al., 2001: PMID11251118; Lee et al., 2007: PMID18073423; Yang et al., 2010: PMID20380830). The molecular mechanisms by which MSPs promote oocyte maturation are complex and reviewed elsewhere (Yamamoto et al., 2005: PMID16372336; Han et al., 2010: PMID20034089). Multiple studies have shown that VAB-1 negatively regulates oocyte MPK-1 MAPK activity, which is primarily controlled by phosphorylation (Lee et al., 2007: PMID18073423). How VAB-1 activation couples to the MAPK cascade is incompletely understood, but several downstream mediators have been identified. A genome-wide RNAi screen identified numerous genes that function in oocytes to inhibit MPK-1 phosphorylation (Govindan et al., 2006: PMID16824915). Genetic tests are consistent with the model that the Disabled homolog DAB-1, Ran GTPase RAN-1, protein kinase C homolog PKC-1, Rho GEF VAV-1, and STAM homolog PQN-19 act in the same pathway as VAB-1. However, these proteins also appear to act in a VAB-1-independent pathway. DAB-1 and RAN-1 physically interact with the VAB-1 intracellular domain, providing the most compelling evidence for a role in signal transduction (Fig. 2) (Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420). Both these proteins are required for VAB-1 accumulation in endocytic-recycling compartments in the absence of sperm.

Table 1.

EphR signaling homologs in selected animals. Shown are components with evidence for a direct interaction with C. elegans VAB-1 (and homologs).

| Description | C. elegans | Drosophila | H. sapiens | Conserved EphR interaction? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand, ephrin class | EFN-1 through EFN-41 | Ephrin | EphrinA1 through EphrinA5, EphrinB1 through EphrinB3 | Drosophila and mammals |

| Ligand, MSP class | MSPs (~28 genes) | None2 | None2 | Not applicable |

| Ligand, MSP/VAP class | VPR-1 | dVAP/VAP332 | VAPA and VAPB2 | Drosophila and mammals (Lua et al., 2011:3 PMID22069488; Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774) |

| Ligand/co-receptor | WRK-1 | None3 | None3 | Not applicable |

| Eph Receptor | VAB-1 | Eph | EphA1 through EphA9, EphB1 through EphB5 | Not applicable |

| Adaptor | NCK-1 | Dock | NCK1 and NCK2 | Drosophila and mammals (Stein et al., 1998a:3 PMID9430661) |

| Adaptor | DAB-1 | Disabled | Disabled1 and Disabled2 | Not known |

| Effector, GTPase | RAN-1 | Ran | Ran | Not known |

| Effector, PTEN | DAF-18 | PTEN | PTEN | Not known |

EFN-4 binds to VAB-1 with lower affinity than other ephrin

There are additional proteins encoded by these genomes with an MSP domain (two in Drosophila and three in humans)

There are proteins encoded by these genomes with similar MAM domains

The phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) DAF-18 is another conserved protein that directly interacts with the VAB-1 intracellular domain (Fig. 2) (Brisbin et al., 2009: PMID19853560). The VAB-1 kinase domain phosphorylates DAF-18, diminishing DAF-18 protein levels and function. daf-18 mutations suppress vab-1 null mutant oocyte maturation and MAPK activation defects, suggesting that DAF-18/PTEN functions in VAB-1 signaling in oocytes. However, daf-18 null mutants (and vab-1 null mutants) are fertile and DAF-18 is likely to play a modulatory role in oocyte maturation (Suzuki and Han, 2006: PMID16481471; Brisbin et al., 2009: PMID19853560). Genetic evidence suggests that the interaction between VAB-1 and DAF-18 in neurons modulates dauer entry and lifespan. DAF-18 is thought to dephosphorylate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, thereby down-regulating insulin signaling (Ogg and Ruvkun, 1998: PMID9885576; Mihaylova et al., 1999: PMID10377431; Rouault et al., 1999: PMID10209098).

VAB-1 also functions in axon guidance where it has roles in regulating the actin cytoskeleton to stop axonal growth. Downstream signal transduction proteins include the NCK-1 SH2/SH3 adaptor protein, which binds to the activated VAB-1 receptor (Fig. 2). The binding of NCK-1 in turn modulates the actin regulators UNC-34 Ena/VASP, WSP-1/N-Wasp and the Arp2/3 complex (Mohamed and Chin-Sang, 2011: PMID21443870; Mohamed et al., 2012: PMID22383893). NCK-1 binding to EphRs appears to be conserved in Drosophila and mammals (Stein et al., 1998: PMID9430661).

Multiple cell surface proteins have been shown to interact with VAB-1. The SAX-3 Roundabout (Robo) receptor and VAB-1 intracellular domains directly interact in yeast two hybrid and in vitro pull down assays (Ghenea et al., 2005: PMID16033794). Gene dosage, non-allelic non-complementation, and co-localization studies support the model that these two receptors form a complex in migrating neuroblasts. In vertebrates, EphRs and NMDA receptor subunits directly interact to modulate Ca2+ influx (Dalva et al., 2000: PMID11136979; Takasu et al., 2002: PMID11799243). Genetic suppression, non-allelic non-complementation, and localization studies support the model that VAB-1 functionally interacts with the NMR-1 NMDA-subtype glutamate receptor in the proximal gonad (Corrigan et al., 2005: PMID16267094). A gain of function allele in the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gene unc-43 causes ectopic oocyte maturation in the absence of sperm, suggesting that it might be regulated by VAB-1 and NMR-1 interaction. Genetic data and a phosphorylation-specific antibody against UNC-43 supported this model (Corrigan et al., 2005: PMID16267094). However, Cheng et al. were not able to replicate the antibody results (Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420). This discrepancy remains unresolved, but could be due to methodological differences. Together, these studies support the view that VAB-1 assembles into multiple heteromeric complexes that affect signal transduction in a cell type-specific fashion.

Among the pathways associated with vertebrate EphR activation are those that modulate the actin cytoskeleton via Rho family small GTPases. EphRs directly interact with Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), such as Ephexin and Vav2 (Shamah et al., 2001: PMID11336673; Cowan et al., 2005: PMID15848800). GEFs have not been directly linked to VAB-1 signaling in C. elegans, but VAB-1 and the Rho GEF VAV-1 have been implicated in oocyte maturation and gonadal sheath contraction (Norman et al., 2005: PMID16213217; Govindan et al., 2006: PMID16824915). Genetic analyses support the hypothesis that VAB-1 and VAV-1 function in a common oocyte pathway to regulate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation (Govindan et al., 2006: PMID16824915). Hence, it is possible that EphR signaling via GEFs is conserved in worms.

3.3 Kinase-independent and reverse signaling

Eph receptors and ephrins transduce bidirectional signals into the Eph receptor-expressing cells and ephrin-expressing cells, known as forward and reverse signaling, respectively (Henkemeyer et al., 1996: PMID8689685). EphRs use tyrosine kinase activity for forward signaling, whereas proteins with SH2 and PDZ domains bind to phosphorylated ephrin B ligands to transmit reverse signals (Cowan and Henkemeyer, 2001: PMID11557983; Lu et al., 2001: PMID11301003). As Ephrin A ligands do not traverse the membrane, less is known regarding their mechanisms of reverse signaling. In C. elegans, there is genetic evidence for a GPI-linked ephrin in reverse signaling. Mutations abolishing VAB-1 tyrosine kinase activity are hypomorphic, suggesting that VAB-1 has kinase-dependent and kinase-independent functions. efn-1/vab-2 mutations specifically enhance vab-1 kinase mutations and the double mutants resemble the vab-1 null phenotype. These genetic interactions suggest that EFN-1 may promote a kinase-independent role for VAB-1, perhaps via reverse signaling. Since EFN-1 is GPI-anchored, it cannot transmit signals on its own and probably depends on transmembrane proteins for reverse signal transmission (Fig. 1). Vertebrate EphA receptors have also been linked to reverse signaling (Araujo et al., 1998: PMID9753674; Davy et al., 1999: PMID10601038; Konstantinova et al., 2007: PMID17448994; Lim et al., 2008: PMID18786358; Bonanomi et al., 2012: PMID22304922). Kinase-independent signaling may not require reverse signaling, as cell adhesion independent of signaling activity may play a role. Furthermore, ligands could signal to the VAB-1 intracellular domain in a way that does not involve VAB-1 kinase activity. For example, a kinase-inactive version of VAB-1 retained some forward signaling function in PLM neurons (Mohamed and Chin-Sang, 2006: PMID16386725).

4. VAB-1 EphR functions during development and adulthood

Although first implicated in neuronal development, Eph receptors have widespread roles during development and in adult tissues. Below we summarize data on known functions for C. elegans VAB-1. These diverse functions are mediated through shared as well as distinct pathway components (see Table 2 for summary).

Table 2.

Summary of VAB-1 EphR biological functions and pathway components.

| Function | Pathway components (upstream, downstream, or parallel) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Ventral enclosure and epidermal morphogenesis | EFN-1-4, BUS-8, SAX-3, PTP-3, MAB-20, PLX-2 | Complex process involving the integration of multiple signaling pathways in neuroblasts and epidermal cells. May also involve VPR-1. |

| Male tail development | EFN1-4, MAB-20, PLX-2 | Involves multiple signaling pathways. |

| Neuron and axon guidance | EFN1-3, VPR-1, WRK-1, NCK-1, WSP-1, UNC-34, ARP2/3, SAX-3 | Includes multiple independent guidance decisions. |

| Muscle cell migration | EFN-1 | Other ephrins may be involved. |

| Oocyte meiotic maturation and oocyte growth | EFN-1-3, MSPs, DAF-18, RAN-1, DAB-1, NMR-1, GSA-1, INX-14, INX-22, MPK-1, PTP-2, LET-60 | Complex process involving the integration of multiple signaling pathways in sheath cells and oocytes (some components not shown). The biochemical relationships among some components are not well understood. |

| Germ line apoptosis | EFN1-3 | |

| Axon regeneration | Likely involves ephrins. | |

| Hypoxia protection | HIF-1 | HIF-1 up-regulates VAB-1 transcription. |

4.1 Ventral enclosure and epidermal morphogenesis

During embryogenesis, the dorsal epidermal cells migrate ventrally to the midline to wrap the embryo in its skin. The VAB-1 EphR and ephrin ligands EFN-1-4 are required for proper ventral epidermal enclosure (George et al., 1998: PMID9506518; Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431; Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316; Chin-Sang et al., 2002: PMID12403719). Surprisingly, EphR signaling is not required in the epidermal leading cells, but instead VAB-1 and EFN-1 are expressed and function in underlying neuroblasts. In vab-1 and efn-1 mutants, the neuroblasts and neurons either fail to move or have abnormal adhesion. Although the molecular mechanisms of neuroblast migration are still unknown, the current model is that EphR signaling is required in neuroblasts for proper organization of the neuronal substrate that the epidermal cells migrate over. The bus-8 gene encodes a glycosyltransferase and acts in or with ephrin signaling. BUS-8 likely modifies one or more components of an ephrin signaling pathway to regulate neuroblast organization (Partridge et al., 2008: PMID18395708).

EFN-1 is considered the major ligand for VAB-1 during ventral enclosure, as efn-2 and efn-3 mutants do not have significant ventral enclosure defects. However, this is likely due to functional redundancy, as the triple ephrin 1–3 mutant resembles a vab-1 null allele. Null mutations in vab-1 or efn-1 do not lead to a completely penetrant phenotype, suggesting that other signaling pathways function redundantly with EphR signaling. Indeed, mutations in the divergent ephrin efn-4, the receptor tyrosine phosphatase ptp-3, and the Robo receptor sax-3 all display a synthetic lethal mutant phenotype with vab-1 null alleles and thus, function redundantly (Chin-Sang et al., 2002: PMID12403719; Harrington et al., 2002: PMID11959824; Ghenea et al., 2005: PMID16033794). The semaphorin MAB-20 and its plexin receptor PLX-2 are thought to function together with EFN-4 during embryogenesis (Nakao et al., 2007: PMID17507686). MAB-20 and PLX-2 also function with VAB-1 in the late stage of ventral enclosure. Here the VAB-1 EphR functions in epidermal cells P9/10, as well as in the underlying neurons to facilitate a bridge for the enclosing pocket cells, providing evidence for a neuronal to epidermal signaling mechanism in ventral enclosure (Ikegami et al., 2012: PMID22197242). Finally, a null mutation in the VAP homolog vpr-1 causes embryogenesis defects and genetically interacts with vab-1 mutants, raising the possibility that VPR-1 participates somehow in embryonic VAB-1 signaling (Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774).

4.2 Male tail development

VAB-1 EphR signaling is required for male tail development, as vab-1 and ephrin mutants have male tail defects, such as ray fusions (Wang et al., 1999: PMID10635316). Similar to ventral enclosure, EFN-4 functions with MAB-20 semaphorin and its plexin receptor PLX-2 to regulate cell-cell contact formation during ray development. In efn-4 and mab-20 mutants, abnormal contacts form between ray cells. However, genetic data suggest that efn-4 acts in parallel to mab-20 during male tail development (Hahn and Emmons, 2003: PMID12679110; Ikegami et al., 2004: PMID15030761; Nakao et al., 2007: PMID17507686).

4.3 Neuron and axon guidance

The VAB-1 EphR was shown to function in guiding amphid sensory neuron axons ventrally into the nerve ring during embryonic development. In addition, the SAX-3 Robo receptor and VAB-1 EphR both function to prevent aberrant axon crossing at the ventral midline (Zallen et al., 1999: PMID10409513). The guidance cues are likely the slit and ephrin ligands, respectively. VAB-1, SAX-3, and the VAP homolog VPR-1 have been implicated in regulating amphid cell body position, suggesting that EphR signaling also influences amphid migration (Zallen et al., 1999: PMID10409513; Ghenea et al., 2005: PMID16033794; Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774).

As mentioned above, WRK-1 functions in midline guidance of a subset of ventral nerve cord axons. The embryonic midline is defined by motor neuron cell bodies that separate the left from the right ventral cord fascicles. WRK-1 and ephrins are expressed on the surface of the embryonic motor neurons DD, DB, and DA. These ligands act together as cues to prevent migrating ventral nerve cord axons from crossing the midline (Boulin et al., 2006: PMID17027485).

EphR signaling is also required for correct PLM cell body positioning and PLM termination. EphR and ephrin ligand mutants display a PLM overshooting phenotype, suggesting that VAB-1 functions to transmit a stop cue for the PLM. Consistent with this idea, a hyperactive ligand-independent version of VAB-1 (MYR-VAB-1) causes PLM axons to stop prematurely (Mohamed and Chin-Sang, 2006: PMID16386725). The NCK-1 adaptor protein functions downstream of VAB-1 in axon guidance and it shares similar axon guidance defects as vab-1 (Mohamed and Chin-Sang, 2011: PMID21443870). Using a candidate suppressor approach, several downstream players in VAB-1 signaling were identified (Mohamed et al., 2012: PMID22383893). The current model is that the actin regulator UNC-34 Ena/VASP is needed for PLM filopodia formation at the growth cone. VAB-1 signaling stops PLM growth by two methods, first by inhibiting UNC-34 activity and second, by recruiting NCK-1 and WSP-1 in a complex, which in turn activates the Arp2/3 complex. Arp2/3 changes actin dynamics at the growth cone from progressive filament protrusions (filopodia) to increased branching. The combined action leads to loss of filopodia at the growth cone, stopping further forward movement.

4.4 Muscle cell migration

During embryogenesis, body wall muscle cells arise from four founder cells on each side of the embryo and migrate dorsally or ventrally toward the midline (Sulston et al., 1983: PMID6684600; Hresko et al., 1994: PMID8106548; Moerman et al., 1996: PMID8575624). The cells eventually rest beneath the dorsal or ventral hypodermal cells, where they develop into four muscle quadrants that run down the anterior to posterior axis. The most anterior muscle cells in each quadrant extend membrane processes to the anterior of the embryo that direct migrating muscle cells. In efn-1 and vab-1 mutants, the ventral anterior muscle cell processes do not extend normally and the muscle cells become displaced posteriorly (Tucker and Han, 2008: PMID18452914; Viveiros et al., 2011: PMID21820426). This abnormal process might be responsible for the classical “notched head” phenotype seen in mutant worms. efn-1 and vab-1 are required for migration of the ventral anterior muscle cells during embryogenesis (Viveiros et al., 2011: PMID21820426). However, this signaling mechanism is not acting in the muscle. Both EFN-1 and VAB-1 function in migrating neuronal precursors (Chin-Sang et al., 1999: PMID10619431; Tucker and Han, 2008: PMID18452914). efn-1 and vab-1 mutations disrupt the migration of these neuronal precursors, resulting in their mislocalization into the path of migrating muscle cells. Hence, neuron migration defects might explain why disruption of anterior muscle processes is limited to ventral muscle cells. Whether the neurons provide cues to the muscle cells that direct their migration or simply block their route in vab-1 mutants is not understood.

4.5 Oocyte maturation

Oocyte maturation is a conserved process by which prophase-arrested oocytes resume meiosis in response to hormonal stimulus (Greenstein, 2005: PMID18050412). C. elegans sperm secrete MSPs to stimulate oocyte maturation (Miller et al., 2001: PMID11251118). The VAB-1 EphR’s role in this process was discovered in a screen for oocyte MSP receptors. MSP binding is reduced by ~35% when VAB-1 is absent, with the remaining binding sites due to additional receptors likely including SAX-3 Robo and CLR-1 Lar-like receptors (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Han et al., 2012: PMID22264801). Biochemical experiments have demonstrated that MSP directly interacts with the VAB-1 EphR extracellular domain (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Govindan et al., 2006: PMID16824915; Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774). The current model is that MSP binds to multiple receptors expressed on oocyte and sheath surfaces to promote oocyte maturation and sheath contraction.

The VAB-1 EphR localizes to the oocyte surface, as well as to endosomal compartments (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420; Brisbin et al., 2009: PMID19853560). Genetic studies have shown that VAB-1 acts as a negative regulator of oocyte maturation. vab-1 null mutants exhibit nearly normal oocyte maturation rates in the presence of MSP, indicating that VAB-1 is not required for oocyte maturation. VAB-1 functions to inhibit MPK-1 activation in growing oocytes exposed to MSP and to down-regulate oocyte maturation rates as sperm numbers diminish. These functions involve the ephrin EFN-2 and PTEN homolog DAF-18 (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Suzuki and Han, 2006: PMID16481471; Brisbin et al., 2009: PMID19853560). In unmated females, the VAB-1 EphR acts in parallel to sheath/oocyte gap junctions to inhibit MPK-1 activation and oocyte maturation (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Govindan et al., 2006: PMID16824915; Whitten and Miller, 2007: PMID16982048), a function that is largely independent of ephrins (Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420). Taken together, the data support the model that MSP binding to VAB-1 antagonizes ephrin-dependent and ephrin-independent inhibitory mechanisms.

VAB-1 EphR trafficking in oocytes is important for signal transduction (Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420). In the absence of MSP, a rescuing VAB-1::GFP reporter primarily localizes to an endocytic-recycling compartment, suggesting that VAB-1 inhibits oocyte maturation while in endosomes. When MSP is present, VAB-1 transits to the cell surface. VAB-1::GFP trafficking to recycling endosomes requires the cytoplasmic adaptor protein DAB-1 and GTPase RAN-1, both of which interact with the VAB-1 intracellular domain. Inactivation of endosomal recycling regulators causes a VAB-1-dependent reduction in the oocyte maturation rate. These results support the model that MSP promotes VAB-1 trafficking. A sheath cell Gαs-adenylate cyclase pathway mediated by GSA-1 and sheath/oocyte gap junctions also regulates VAB-1::GFP trafficking (Govindan et al., 2006: PMID16824915; Cheng et al., 2008: PMID18472420; Govindan et al., 2009: PMID19502483). gsa-1 RNAi causes VAB-1::GFP to accumulate in endosomes in the presence of MSP, resembling the pattern seen in unmated females. In contrast, loss of gap junctions in unmated females causes VAB-1::GFP to localize to the cell surface, resembling the pattern seen in hermaphrodites.

4.6 Axon regeneration

The axons of many animals are able to regenerate after injury. VAB-1 EphR signaling influences the outgrowth and guidance of regenerating axons. In vab-1 mutants, axon regrowth after axotomy is more accurate than in wild-type animals. Kinase-independent signaling appears to interfere with guidance of the regrowing axon, while a kinase-dependent role represses anterior growth (Wu et al., 2007: PMID17848506).

4.7 Germ line apoptosis

The somatic gonadal sheath cells are proposed to provide an apoptotic signal that promotes germ cell apoptosis important for oogenesis (Li et al., 2012: PMID22240896). EFN-1, 2, and 3 have a partially redundant pro-apoptotic function and are thought to signal from sheath cells to germ cell VAB-1 (Li et al., 2012: PMID22240896). VAB-1 EphR signaling functions in the germ line to promote apoptosis and may act upstream of or in parallel to MAPK signaling. The role of MPK-1 is germ cell apoptosis may not be simple. Whereas strong loss of function mutations in mpk-1 prevent apoptosis (Gumienny et al., 1999: PMID9927601), it is unclear whether the germ cells have differentiated enough to enter the cell death pathway. Temperature shift experiments using the mpk-1(ga111) allele suggest that MPK-1 may negatively regulate apoptosis (Arur et al., 2009: PMID19264959).

4.8 Other functions

In addition to the processes described above, the VAB-1 EphR has been implicated in several other processes. VAB-1 was shown to act downstream of the transcription factor HIF-1 (hypoxia-inducible factor 1) during oxygen deprivation (Pocock and Hobert, 2008: PMID18587389). HIF-1-dependent VAB-1 up-regulation protects embryos from hypoxia. However, increased VAB-1 activity also causes abnormal axon trajectories in oxygen-deprived animals. The mechanism by which VAB-1 protects worms from hypoxia is not well understood, although VAB-1 has been shown to regulate DAF-18 PTEN (Brisbin et al., 2009: PMID19853560). DAF-18-mediated down-regulation of insulin signaling plays an important role in modulating metabolism during normal and hypoxic conditions (Vowels and Thomas, 1992: PMID1732156; Ogg and Ruvkun, 1998: PMID9885576; Scott et al., 2002: PMID12065745; Pocock and Hobert, 2008: PMID18587389). vab-1 null hermaphrodites have longer lifespans and increased dauer frequency at high temperature relative to controls (Brisbin et al., 2009: PMID19853560). Elevated FOXO activity causes increased lifespan and dauer entry (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2006: PMID16839734). Thus, VAB-1-mediated regulation of PTEN may modulate metabolism that in turn affects survival under hypoxic conditions, dauer, and lifespan.

VAB-1 has been implicated in regulating the basal gonadal sheath contraction rate, which is stimulated by MSP (Miller et al., 2001: PMID11251118). Sheath contraction is an actomyosin-dependent process that does not require oocytes or input from the nervous system (Myers et al., 1996: PMID8601585; Hall et al., 1999: PMID10419689; McCarter et al., 1999: PMID9882501). The heterotrimeric G protein subunit Gαq EGL-30, phospholipase CγPLC-3, and inositol triphosphate receptor ITR-1 are essential for sheath contraction (Yin et al., 2004: PMID15194811; Corrigan et al., 2005: PMID16267094; Govindan et al., 2009: PMID19502483). Furthermore, EGL-30 activity is sufficient for contraction. There have been several reports that vab-1 null mutant or RNAi adults have lower basal sheath contraction rates in the presence of MSP (Miller et al., 2003: PMID12533508; Yin et al., 2004: PMID15194811; Corrigan et al., 2005: PMID16267094). However, another study could not replicate this finding and it is currently unclear whether this discrepancy is due to differences in animal age, mounting conditions, or other methodological issues (Govindan et al., 2009: PMID19502483).

Mutations in the ephrin efn-2, vab-1, or VAP homolog vpr-1 cause defects in migration of the distal tip cell (DTC) (Tsuda et al., 2008: PMID18555774), a leader cell that patterns the gonad (Kimble, 1981: PMID6117910). vpr-1 VAP null mutants exhibit fully penetrant DTC migration defects, whereas vab-1 EphR and efn-2 mutant phenotypes are relatively mild and incompletely penetrant. VPR-1 has been shown to regulate the actin cytoskeleton and mitochondria in body wall muscle and the effects of vpr-1 mutants on DTC migration could be due to abnormal energy metabolism in the gonad (Han et al., 2012: PMID22264801).

5. Future Prospects

EphRs were among the first receptors to emerge during animal evolution and have among the most complex signaling mechanisms. Although vab-1 mutant phenotypes were initially described over 30 years ago, there is still much to learn about EphR signaling in C. elegans. Genetic and biochemical evidence suggests that VAB-1 forms multiple heteromeric complexes that affect signal transduction, yet the compositions of these complexes and their transduction mechanisms are not well understood. It will be important to address these outstanding issues, as they may relate to kinase-independent and reverse signaling. Another important area of focus should be on signal transduction to the actin cytoskeleton and MAPK cascade. These mechanisms could have important implications for development, metabolism, axon regeneration, neurodegenerative diseases, reproduction, and cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pauline Cottee, Sung Min Han, Se-Jin Lee, William Bendena, Jun Liu, and Michael Zanetti for comments on the manuscript. Work in the Miller lab is supported by grants from the NIH (R01GM085105) and MDA (186119). Work in the Chin-Sang lab is supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC 249779) and the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (CCSRI 700219).

Contributor Information

Michael A. Miller, Email: mamiller@uab.edu.

Ian D. Chin-Sang, Email: chinsang@queensu.ca.

References

- Araujo M, Piedra ME, Herrera MT, Ros MA, Nieto MA. The expression and regulation of chick EphA7 suggests roles in limb patterning and innervation. Development. 1998:4195–4204. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arur S, Ohmachi M, Nayak S, Hayes M, Miranda A, Hay A, Golden A, Schedl T. Multiple ERK substrates execute single biological processes in Caenorhabditis elegans germ-line development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009:4776–4781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812285106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitis D, Davy A. Eph/ephrin signaling: networks. Genes Dev. 2008:416–429. doi: 10.1101/gad.1630408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley TD, Hunt RW, Welcher AA, Boyle WJ, Parker VP, Lindberg RA, Lu HS, Colombero AM, Elliott RL, Guthrie BA, et al. B61 is a ligand for the ECK receptor protein-tyrosine kinase. Nature. 1994:558–560. doi: 10.1038/368558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanomi D, Chivatakarn O, Bai G, Abdesselem H, Lettieri K, Marquardt T, Pierchala BA, Pfaff SL. Ret Is a Multifunctional Coreceptor that Integrates Diffusible- and Contact-Axon Guidance Signals. Cell. 2012:568–582. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulin T, Pocock R, Hobert O. A novel Eph receptor-interacting IgSF protein provides C. elegans motoneurons with midline guidepost function. Curr Biol. 2006:1871–1883. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M, Nighorn A, Thomas JB. Drosophila Eph receptor guides specific axon branches of mushroom body neurons. Development. 2006:1845–1854. doi: 10.1242/dev.02353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisbin S, Liu J, Boudreau J, Peng J, Evangelista M, Chin-Sang I. A role for C. elegans Eph RTK signaling in PTEN regulation. Dev Cell. 2009:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JA, Kirkness EF, Simakov O, Hampson SE, Mitros T, Weinmaier T, Rattei T, Balasubramanian PG, Borman J, Busam D, et al. The dynamic genome of Hydra. Nature. 2010:592–596. doi: 10.1038/nature08830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chan DC. Mitochondrial dynamics--fusion, fission, movement, and mitophagy--in neurodegenerative diseases. Human molecular genetics. 2009:R169–176. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Govindan JA, Greenstein D. Regulated trafficking of the MSP/Eph receptor during oocyte meiotic maturation in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2008:705–714. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin-Sang ID, George SE, Ding M, Moseley SL, Lynch AS, Chisholm AD. The ephrin VAB-2/EFN-1 functions in neuronal signaling to regulate epidermal morphogenesis in C. elegans. Cell. 1999:781–790. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin-Sang ID, Moseley SL, Ding M, Harrington RJ, George SE, Chisholm AD. The divergent C. elegans ephrin EFN-4 functions inembryonic morphogenesis in a pathway independent of the VAB-1 Eph receptor. Development. 2002:5499–5510. doi: 10.1242/dev.00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow KL, Emmons SW. HOM-C/Hox genes and four interacting loci determine the morphogenetic properties of single cells in the nematode male tail. Development. 1994:2579–2592. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan C, Subramanian R, Miller MA. Eph and NMDA receptors control Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activation during C. elegans oocyte meiotic maturation. Development. 2005:5225–5237. doi: 10.1242/dev.02083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M. The SH2/SH3 adaptor Grb4 transduces B-ephrin reverse signals. Nature. 2001:174–179. doi: 10.1038/35093123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CW, Shao YR, Sahin M, Shamah SM, Lin MZ, Greer PL, Gao S, Griffith EC, Brugge JS, Greenberg ME. Vav family GEFs link activated Ephs to endocytosis and axon guidance. Neuron. 2005:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalva MB, Takasu MA, Lin MZ, Shamah SM, Hu L, Gale NW, Greenberg ME. EphB receptors interact with NMDA receptors and regulate excitatory synapse formation. Cell. 2000:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Gale NW, Aldrich TH, Maisonpierre PC, Lhotak V, Pawson T, Goldfarb M, Yancopoulos GD. Ligands for EPH-related receptor tyrosine kinases that require membrane attachment or clustering for activity. Science. 1994:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.7973638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davy A, Gale NW, Murray EW, Klinghoffer RA, Soriano P, Feuerstein C, Robbins SM. Compartmentalized signaling by GPI-anchored ephrin-A5 requires the Fyn tyrosine kinase to regulate cellular adhesion. Genes Dev. 1999:3125–3135. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.23.3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SE, Simokat K, Hardin J, Chisholm AD. The VAB-1 Eph receptor tyrosine kinase functions in neural and epithelial morphogenesis in C. elegans. Cell. 1998:633–643. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghenea S, Boudreau JR, Lague NP, Chin-Sang ID. The VAB-1 Eph receptor tyrosine kinase and SAX-3/Robo neuronal receptors function together during C. elegans embryonic morphogenesis. Development. 2005:3679–3690. doi: 10.1242/dev.01947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindan JA, Cheng H, Harris JE, Greenstein D. Galphao/i and Galphas signaling function in parallel with the MSP/Eph receptor to control meiotic diapause in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2006:1257–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindan JA, Nadarajan S, Kim S, Starich TA, Greenstein D. Somatic cAMP signaling regulates MSP-dependent oocyte growth and meiotic maturation in C. elegans. Development. 2009:2211–2221. doi: 10.1242/dev.034595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein D. Control of oocyte meiotic maturation and fertilization. WormBook. 2005:1–12. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.53.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C, Park S. The EphA8 receptor regulates integrin activity through p110gamma phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase in a tyrosine kinase activity-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2001:4579–4597. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4579-4597.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumienny TL, Lambie E, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR, Hengartner MO. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite germline. Development. 1999:1011–1022. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn AC, Emmons SW. The roles of an ephrin and a semaphorin in patterning cell-cell contacts in C. elegans sensory organ development. Dev Biol. 2003:379–388. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DH, Winfrey VP, Blaeuer G, Hoffman LH, Furuta T, Rose KL, Hobert O, Greenstein D. Ultrastructural features of the adult hermaphrodite gonad of Caenorhabditis elegans: relations between the germ line and soma. Dev Biol. 1999:101–123. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SM, Cottee PA, Miller MA. Sperm and oocyte communication mechanisms controlling C. elegans fertility. Dev Dyn. 2010:1265–1281. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SM, Tsuda H, Yang Y, Vibbert J, Cottee P, Lee SJ, Winek J, Haueter C, Bellen HJ, Miller MA. Secreted VAPB/ALS8 Major Sperm Protein Domains Modulate Mitochondrial Localization and Morphology via Growth Cone Guidance Receptors. Dev Cell. 2012:348–362. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MJ, Dallal GE, Flanagan JG. Retinal axon response to ephrin-as shows a graded, concentration-dependent transition from growth promotion to inhibition. Neuron. 2004:717–730. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington RJ, Gutch MJ, Hengartner MO, Tonks NK, Chisholm AD. The C. elegans LAR-like receptor tyrosine phosphatase PTP-3 and the VAB-1 Eph receptor tyrosine kinase have partly redundant functions in morphogenesis. Development. 2002:2141–2153. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.9.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkemeyer M, Orioli D, Henderson JT, Saxton TM, Roder J, Pawson T, Klein R. Nuk controls pathfinding of commissural axons in the mammalian central nervous system. Cell. 1996:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himanen JP, Henkemeyer M, Nikolov DB. Crystal structure of the ligand-binding domain of the receptor tyrosine kinase EphB2. Nature. 1998:486–491. doi: 10.1038/24904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himanen JP, Rajashankar KR, Lackmann M, Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M, Nikolov DB. Crystal structure of an Eph receptor-ephrin complex. Nature. 2001:933–938. doi: 10.1038/414933a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai H, Maru Y, Hagiwara K, Nishida J, Takaku F. A novel putative tyrosine kinase receptor encoded by the eph gene. Science. 1987:1717–1720. doi: 10.1126/science.2825356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hresko MC, Williams BD, Waterston RH. Assembly of body wall muscle and muscle cell attachment structures in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 1994:491–506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami R, Simokat K, Zheng H, Brown L, Garriga G, Hardin J, Culotti J. Semaphorin and Eph Receptor Signaling Guide a Series of Cell Movements for Ventral Enclosure in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2012:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami R, Zheng H, Ong SH, Culotti J. Integration of semaphorin-2A/MAB-20, ephrin-4, and UNC-129 TGF-beta signaling pathways regulates sorting of distinct sensory rays in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2004:383–395. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Nighorn A. Interaxonal Eph-ephrin signaling may mediate sorting of olfactory sensory axons in Manduca sexta. J Neurosci. 2003:11523–11538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11523.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble JE. Strategies for control of pattern formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1981:539–551. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1981.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klass MR, Hirsh D. Sperm isolation and biochemical analysis of the major sperm protein from C. elegans. Dev Biol. 1981:299–312. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinova I, Nikolova G, Ohara-Imaizumi M, Meda P, Kucera T, Zarbalis K, Wurst W, Nagamatsu S, Lammert E. EphA-Ephrin-A-mediated beta cell communication regulates insulin secretion from pancreatic islets. Cell. 2007:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski M, McDonald K, Schwartz J, Yamamoto I, Greenstein D. C. elegans sperm bud vesicles to deliver a meiotic maturation signal to distant oocytes. Development. 2005:3357–3369. doi: 10.1242/dev.01916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Ohmachi M, Arur S, Nayak S, Francis R, Church D, Lambie E, Schedl T. Multiple functions and dynamic activation of MPK-1 extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans germline development. Genetics. 2007:2039–2062. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.081356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner B, Crombie C, Tischler J, Fortunato A, Fraser AG. Systematic mapping of genetic interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans identifies common modifiers of diverse signaling pathways. Nat Genet. 2006:896–903. doi: 10.1038/ng1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev S, Ben Halevy D, Peretti D, Dahan N. The VAP protein family: from cellular functions to motor neuron disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2008:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Johnson RW, Park D, Chin-Sang I, Chamberlin HM. Somatic gonad sheath cells and Eph receptor signaling promote germ-cell death in C. elegans. Cell Death Differ. 2012 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YS, McLaughlin T, Sung TC, Santiago A, Lee KF, O’Leary DD. p75(NTR) mediates ephrin-A reverse signaling required for axon repulsion and mapping. Neuron. 2008:746–758. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Sun EE, Klein RS, Flanagan JG. Ephrin-B reverse signaling is mediated by a novel PDZ-RGS protein and selectively inhibits G protein-coupled chemoattraction. Cell. 2001:69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lua S, Qin H, Lim L, Shi J, Gupta G, Song J. Structural, stability, dynamic and binding properties of the ALS-causing T46I mutant of the hVAPB MSP domain as revealed by NMR and MD simulations. PLoS One. 2011:e27072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarter J, Bartlett B, Dang T, Schedl T. On the control of oocyte meiotic maturation and ovulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental biology. 1999:111–128. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova VT, Borland CZ, Manjarrez L, Stern MJ, Sun H. The PTEN tumor suppressor homolog in Caenorhabditis elegans regulates longevity and dauer formation in an insulin receptor-like signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999:7427–7432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Nguyen VQ, Lee MH, Kosinski M, Schedl T, Caprioli RM, Greenstein D. A sperm cytoskeletal protein that signals oocyte meiotic maturation and ovulation. Science. 2001:2144–2147. doi: 10.1126/science.1057586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Ruest PJ, Kosinski M, Hanks SK, Greenstein D. An Eph receptor sperm-sensing control mechanism for oocyte meiotic maturation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2003:187–200. doi: 10.1101/gad.1028303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerman DG, Hutter H, Mullen GP, Schnabel R. Cell autonomous expression of perlecan and plasticity of cell shape in embryonic muscle of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1996:228–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed AM, Boudreau JR, Yu FP, Liu J, Chin-Sang ID. The Caenorhabditis elegans Eph receptor activates NCK and N-WASP, and inhibits Ena/VASP to regulate growth cone dynamics during axon guidance. PLoS Genetics. 2012:e1002513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed AM, Chin-Sang ID. Characterization of loss-of-function and gain-of-function Eph receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in C. elegans axon targeting and cell migration. Dev Biol. 2006:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed AM, Chin-Sang ID. The C. elegans nck-1 gene encodes two isoforms and is required for neuronal guidance. Dev Biol. 2011:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A, Oh SW, Tissenbaum HA. Worming pathways to and from DAF-16/FOXO. Exp Gerontol. 2006:928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CD, Goh PY, Allen TS, Bucher EA, Bogaert T. Developmental genetic analysis of troponin T mutations in striated and nonstriated muscle cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 1996:1061–1077. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.6.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao F, Hudson ML, Suzuki M, Peckler Z, Kurokawa R, Liu Z, Gengyo-Ando K, Nukazuka A, Fujii T, Suto F, et al. The PLEXIN PLX-2 and the ephrin EFN-4 have distinct roles in MAB-20/Semaphorin 2A signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans morphogenesis. Genetics. 2007:1591–1607. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.067116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura AL, Mitne-Neto M, Silva HC, Richieri-Costa A, Middleton S, Cascio D, Kok F, Oliveira JR, Gillingwater T, Webb J, et al. A mutation in the vesicle-trafficking protein VAPB causes late-onset spinal muscular atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004:822–831. doi: 10.1086/425287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman KR, Fazzio RT, Mellem JE, Espelt MV, Strange K, Beckerle MC, Maricq AV. The Rho/Rac-family guanine nucleotide exchange factor VAV-1 regulates rhythmic behaviors in C. elegans. Cell. 2005:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg S, Ruvkun G. The C. elegans PTEN homolog, DAF-18, acts in the insulin receptor-like metabolic signaling pathway. Mol Cell. 1998:887–893. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge FA, Tearle AW, Gravato-Nobre MJ, Schafer WR, Hodgkin J. The C. elegans glycosyltransferase BUS-8 has two distinct and essential roles in epidermal morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: bidirectional signalling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010:165–180. doi: 10.1038/nrc2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitulescu ME, Adams RH. Eph/ephrin molecules--a hub for signaling and endocytosis. Genes Dev. 2010:2480–2492. doi: 10.1101/gad.1973910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock R, Hobert O. Oxygen levels affect axon guidance and neuronal migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Neurosci. 2008:894–900. doi: 10.1038/nn.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouault JP, Kuwabara PE, Sinilnikova OM, Duret L, Thierry-Mieg D, Billaud M. Regulation of dauer larva development in Caenorhabditis elegans by daf-18, a homologue of the tumour suppressor PTEN. Curr Biol. 1999:329–332. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott BA, Avidan MS, Crowder CM. Regulation of hypoxic death in C. elegans by the insulin/IGF receptor homolog DAF-2. Science. 2002:2388–2391. doi: 10.1126/science.1072302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamah SM, Lin MZ, Goldberg JL, Estrach S, Sahin M, Hu L, Bazalakova M, Neve RL, Corfas G, Debant A, et al. EphA receptors regulate growth cone dynamics through the novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor ephexin. Cell. 2001:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FM, Vearing C, Lackmann M, Treutlein H, Himanen J, Chen K, Saul A, Nikolov D, Boyd AW. Dissecting the EphA3/Ephrin-A5 interactions using a novel functional mutagenesis screen. J Biol Chem. 2004:9522–9531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava M, Simakov O, Chapman J, Fahey B, Gauthier ME, Mitros T, Richards GS, Conaco C, Dacre M, Hellsten U, et al. The Amphimedon queenslandica genome and the evolution of animal complexity. Nature. 2010:720–726. doi: 10.1038/nature09201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Huynh-Do U, Lane AA, Cerretti DP, Daniel TO. Nck recruitment to Eph receptor, EphB1/ELK, couples ligand activation to c-Jun kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998:1303–1308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Lane AA, Cerretti DP, Schoecklmann HO, Schroff AD, Van Etten RL, Daniel TO. Eph receptors discriminate specific ligand oligomers to determine alternative signaling complexes, attachment, and assembly responses. Genes Dev. 1998:667–678. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Han M. Genetic redundancy masks diverse functions of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN during C. elegans development. Genes Dev. 2006:423–428. doi: 10.1101/gad.1378906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasu MA, Dalva MB, Zigmond RE, Greenberg ME. Modulation of NMDA receptor-dependent calcium influx and gene expression through EphB receptors. Science. 2002:491–495. doi: 10.1126/science.1065983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr DE, Scott AL. MSP domain proteins. Trends Parasitol. 2005:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda H, Han SM, Yang Y, Tong C, Lin YQ, Mohan K, Haueter C, Zoghbi A, Harati Y, Kwan J, et al. The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 8 protein VAPB is cleaved, secreted, and acts as a ligand for Eph receptors. Cell. 2008:963–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M, Han M. Muscle cell migrations of C. elegans are mediated by the alpha-integrin INA-1, Eph receptor VAB-1, and a novel peptidase homologue MNP-1. Dev Biol. 2008:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros R, Hutter H, Moerman DG. Membrane extensions are associated with proper anterior migration of muscle cells during Caenorhabditis elegans embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 2011:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vowels JJ, Thomas JH. Genetic analysis of chemosensory control of dauer formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1992:105–123. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Roy PJ, Holland SJ, Zhang LW, Culotti JG, Pawson T. Multiple ephrins control cell organization in C. elegans using kinase- dependent and -independent functions of the VAB-1 Eph receptor. Mol Cell. 1999:903–913. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S, Klass M. The location of the major protein in Caenorhabditis elegans sperm and spermatocytes. Dev Biol. 1982:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten SJ, Miller MA. The role of gap junctions in Caenorhabditis elegans oocyte maturation and fertilization. Dev Biol. 2007:432–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer-Kleikamp SH, Janes PW, Squire A, Bastiaens PI, Lackmann M. Recruitment of Eph receptors into signaling clusters does not require ephrin contact. J Cell Biol. 2004:661–666. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Ghosh-Roy A, Yanik MF, Zhang JZ, Jin Y, Chisholm AD. Caenorhabditis elegans neuronal regeneration is influenced by life stage, ephrin signaling, and synaptic branching. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007:15132–15137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto I, Kosinski ME, Greenstein D. Start me up: Cell signaling and the journey from oocyte to embryo in C. elegans. Dev Dyn. 2005:571–585. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Han SM, Miller MA. MSP hormonal control of the oocyte MAP kinase cascade and reactive oxygen species signaling. Dev Biol. 2010:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Gower NJ, Baylis HA, Strange K. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling regulates rhythmic contractile activity of myoepithelial sheath cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2004:3938–3949. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen JA, Kirch SA, Bargmann CI. Genes required for axon pathfinding and extension in the C. elegans nerve ring. Development. 1999:3679–3692. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]