Abstract

Ongoing antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence and secondary HIV transmission risk reduction (positive prevention) support are needed in resource-limited settings. We evaluated a nurse-delivered counseling intervention in Kenya. We trained 90 nurses on a brief counseling algorithm that comprised ART and sexual risk assessment, risk reduction messages, and health promotion planning. Self-reported measures were assessed before, immediately after, and 2 months post-training. Consistent ART adherence assessment was reported by 29% of nurses at baseline and 66% at 2 months post-training (p < 0.001). Assessment of patient sexual behaviors was 25% at baseline and 60% at 2 months post-training (p < 0.001). Nurse practice behaviors recommended in the counseling algorithm improved significantly at 2 months post-training compared with baseline, odds ratios 4.30–10.50. We found that training nurses in clinical counseling for ART adherence and positive prevention is feasible. Future studies should test impact of nurse counseling on patient outcomes in resource-limited settings.

Keywords: antiretrovirals, HIV counseling, prevention with positives, resource-limited settings, treatment adherence

Clinicians do not always address secondary HIV transmission risk reduction (Marks et al., 2002) with HIV-infected patients, though guidelines have been published and meta-analyses have shown that behavioral interventions can reduce unprotected sex among persons with HIV in resource-rich countries. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], National Institutes of Health [NIH], HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Society of America, HIV Prevention in Clinical Care Working Group, 2004; Crepaz et al., 2006; Johnson, Carey, Chaudoir, & Reid, 2006). Research in the United States has found that clinics with written positive prevention protocols have higher levels of provider-reported delivery of such counseling (Morin et al., 2004). Fewer data are available on such positive prevention counseling approaches in resource-limited settings with high HIV disease burdens. Likewise, ongoing antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence support is necessary for persons living with HIV (PLWH), especially in settings where second-line regimens are significantly more expensive. In these settings nurses provide a substantial proportion of HIV patient care (Samb et al., 2007) but may not receive training in evidence-based counseling for patients regarding ART adherence and transmission risk reduction.

We report here on a counseling intervention focusing on integrated delivery of both HIV treatment adherence and prevention of secondary HIV transmission (positive prevention) that was piloted among nurses delivering HIV care in Kenya. Our aim was to delineate the potential utility of a curriculum for brief, evidence-based counseling by nurses in Kenya, where more than 1.4 million people are living with HIV and population prevalence in some geographical areas is 25%.

Methods

Intervention

The nurse counseling algorithm drew from the available evidence base showing reduced sexual transmission risk behaviors from HIV clinic-based counseling (Bunnell et al., 2006; Bunnell et al., 2005; Fisher et al., 2006; Malamba et al., 2005; Richardson et al., 2004) and guidelines for incorporating prevention into HIV care settings (CDC, HRSA, NIH, HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Society of America, HIV Prevention in Clinical Care Working Group, 2004), including cultural adaptation to African settings (Rosenberg et al., 2007) and ART adherence interventions (Amico, Harman, & Johnson, 2006; Simoni, Pearson, Pantalone, Marks, & Crepaz, 2006). No national “prevention with positives” guidelines had been promulgated in Kenya at the time of this intervention, although the Kenya National AIDS/STD Control Programme Positive Prevention counseling guideline was published in October 2009.

Kenyan HIV nurses and educators (n = 6) and HIV-infected female patients (n = 5) served as expert advisors in the cultural contextualization of the intervention materials, reviewing them for face and content validity. We also conducted formative interviews using a structured topic guide with 20 HIV-infected women, 10 on ART and 10 not, who were recruited from a Mombasa research cohort, and 10 health care workers from clinic sites throughout Mombasa (findings not described here; see McClelland et al., 2011). These qualitative data informed final development of the Pambazuko – Life Goes On intervention materials including patient education graphical booklets in English and Kiswahili. Materials are available at http://www.pambazuko.org/.

Participants were instructed in the delivery of the Pambazuko counseling content at a training that followed the principles of adult learning, using exemplar case studies in an interactive problem-based learning (Williams & Pace, 2009) approach. The provision of tools to help nurses modify the clinic milieu to encourage open discussion of sexual risk reduction and adherence was an important feature of the intervention. Tools included posters to hang in clinic, penile models to use with patients for condom demonstrations, and patient education booklets. Such changes in clinic milieu have been shown to be effective in prior studies of health behaviors (Manfredi, Crittenden, Cho, Engler, & Warnecke, 2000; Mathews et al., 2002).

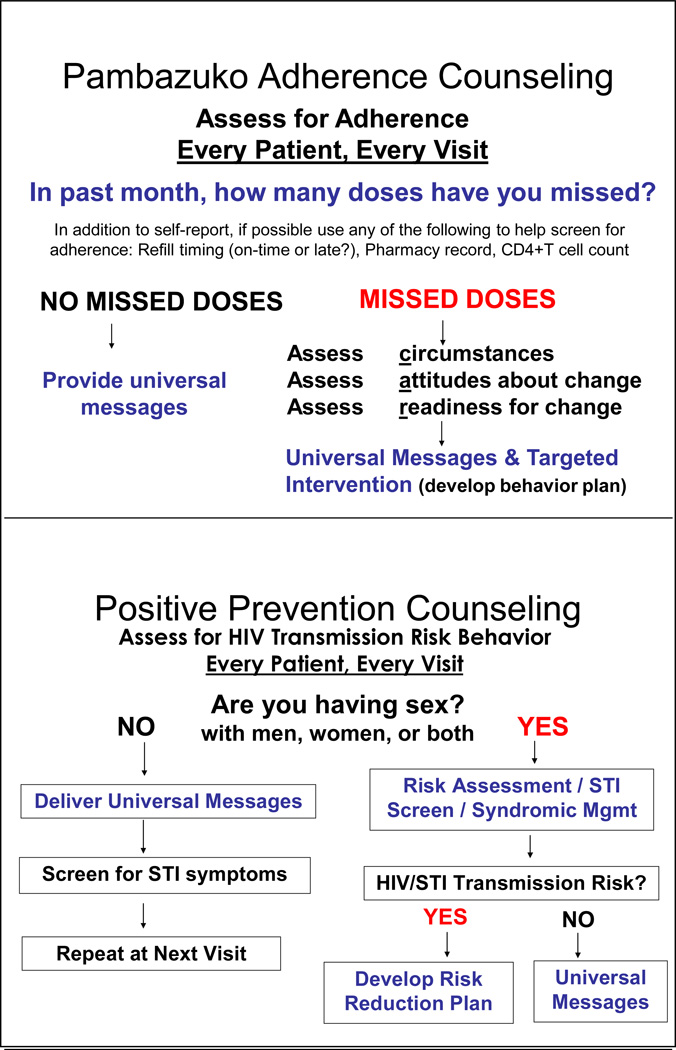

The nurse counseling model was formally pilot tested by assessing shifts in clinical practice measures following a 3-day workshop held in Mombasa in November 2007, attended by 90 nurses involved in HIV care from seven of the eight provinces throughout Kenya. The counseling model included ART adherence and sexual risk assessment, sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening, universal risk reduction messages, and developing behavior plans for high-risk patients to support treatment adherence and reduce sexual risk(s), to be delivered at every clinic visit (Figure 1). Baseline, immediate post-training, and 2-month post-training attendee knowledge, attitudes, and clinical practice measure data were collected using self-administered questionnaires with Likert scale, multiple choice, and categorical items. Pre-training and 2-month post-training survey items were worded exactly the same except that some immediately-post training items were worded as intent to perform behavior upon return to work.

Figure 1. HIV provider counseling algorithm.

Note. STI = sexually transmitted infection; Mgmt = Management; Patient education (in English and Kiswahili), provider counseling algorithm, and clinic milieu materials available for download at www.pambazuko.org

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from all regions of the country through email contact with directors of President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) sites, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) clinics and programs, University of Nairobi HIV/STI Collaborative Research Group in Kenya, and the Nursing Council of Kenya, as well as through recommendation of the study expert advisory group. Eligibility criteria were: (a) being a registered nurse in Kenya, (b) working in a clinic or hospital with HIV-1 seropositive patients, (c) participant’s worksite initiated or planned to initiate ART within 1 year of the training, and (d) willingness to attend the training and be available for 2-month follow-up evaluation. Exclusion criterion was a license (KRN or Kenyan registered counselor or equivalent) that was not up to date. All participants gave written informed consent. Human subjects approval was obtained from the University of Washington and the Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Curriculum

Training content totaled 24 hours held over 4 days. Sessions involved all nurses and faculty and included didactic lectures, clinical case studies, skills demonstrations, and small group work.

Analysis

Nurse knowledge and clinical practice outcomes at both immediate post-intervention and at 2 months post-intervention were compared with baseline. We assessed computed aggregate knowledge and attitude score variables separately. The knowledge score comprised four items assessing general self-reported knowledge of how ART affects HIV in the body, how ART should be used most effectively, factors that can affect ART adherence, and strategies that may increase adherence. The attitude score summed 4-point Likert scales for six separate items framed as the respondent’s level of comfort with various scenarios described as follows: (a) asking gender of patient’s partner(s), (b) discussing sexual behavior, (c) asking about HIV/STI prevention methods, (d) discussing experience with using condoms, (e) educating regarding HIV/STI transmission, and (f) helping patient make a risk reduction plan. To detect changes in the knowledge or attitude score, we compared the mean score at baseline, at immediate post-training and 2-month post-training follow-up using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Bonferroni test of equivalence of means. In order to report a single point estimate of this effect, we modeled a 1-point increase in Likert score comparing baseline to 2 months using linear regression with robust estimators.

For each clinical practice behavior, we compared reported behaviors 2 months post-training with reported behaviors at baseline using a logistic regression model using robust sandwich estimators of the standard error to properly account for correlation in reported behavior for the same individual. We also examined the data using generalized estimating equations (GEE) and found no difference in interpretation, and so we report here the logistic models. Subgroup patterns that were hypothesized a priori, specifically whether training effect varied if counseling protocols existed in the workplace prior to the training, were assessed for effect modification.

Results

Among the 86 nurses (95.6%) who completed assessments, 75% were female, 7% were Registered Nurses (diploma) while the remainder were Enrolled Nurses (certificate), and about one third were relatively new practitioners (< 5 years post licensure, 30.6%). The median number of HIV-infected patients cared for per month was 750 (interquartile range 162–1625). Written protocols were reported to be available in their clinics prior to the training as follows: post-exposure prophylaxis (94.8%), management of patients initiating ART (81.3%), post-initiation ART management (80.0%), reducing occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens (77.5%), and protocols to support HIV transmission risk reduction among HIV-infected patients (prevention with positives; 61.5%).

Daily process evaluations during the training documented which elements of the counseling content were useful, as well as which additional issues were particularly relevant in the Kenyan context. These included the need for increased focus on polygynous marriages in the context of HIV disclosure to sexual partners, addressing reproductive goals of HIV-discordant couples, partner notification options, and a need to emphasize a range of prevention messages beyond reinforcing condom use. Notably, 20% of nurses spontaneously noted on these forms as well as commented during the condom demonstration training that they had never previously touched a condom nor had known how to use one.

Self-reported comfort level with performing ART adherence and positive prevention assessments improved significantly following the counseling intervention training, as measured on a 4-point Likert scale measurement. We observed significant increases in provider comfort with discussing sexual behaviors, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.6 (95% CI 1.3–2.0) for each 1-point increase in provider comfort level between baseline (44.7% were at the highest comfort level) to 2 months post-training (75.4% at highest level). Provider comfort with discussing the sex of the patient’s sexual partners increased from 27.6% at highest comfort level at baseline to 61.5% at 2 months, OR 1.9 (95% CI 1.5–2.3).

The nurses’ aggregate knowledge and attitudes scores both improved significantly from baseline to the immediate post-training assessment (knowledge: mean score of 8.8 to 11.6 on a scale of 0 to 12, p < 0.001; attitude: mean score of 14.8 to 17.5 on a scale of 0 to 24, p < 0.001). Many of these practice behaviors remained stable at 2 months post-training (knowledge: mean = 11.0, p = 0.317 for immediate vs. 2 months post; attitude: mean of 17.1, p = 1.0 for immediate vs. 2 months post).

Evidence of improvement in consistent clinical practice patterns, defined as reportedly used for more than 75% of HIV-infected patients in the previous 2 months, was seen for all counseling elements comparing baseline to the 2-month post-test: ART adherence, discussion of sexual behavior, universal prevention messaging, and plan to reduce risky sexual behavior (Table 2). When asked to refer only to their last HIV-infected patient seen at a routine visit, statistically significant increases in clinical practice behavior were reported for all but three practice patterns: asking about condoms, pregnancy risk, and alcohol use, for which nurse assessment already was high (> 80%) at baseline.

Table 2.

HIV Nurse Practice Behaviors

| Clinical practice pattern comparing 2 months post-training with baseline |

Pre- training |

2 months post- training |

Odds Ratio (OR) |

95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (% reporting behavior) |

|||||

| Addressed with > 75% of HIV patients in previous 2 months | |||||

| ART adherence assessment* | 28.6% | 65.6% | 4.8 | 2.6, 8.8 | 0.000 |

| Importance of ART adherence | 29.0% | 70.3% | 5.9 | 2.9, 12.0 | 0.000 |

| Barriers to support ART adherence plan* | 20.0% | 56.3% | 5.7 | 2.9, 11.3 | 0.000 |

| Sexual behavior | 25.0% | 60.3% | 4.6 | 2.4, 8.8 | 0.000 |

| Universal prevention messages* | 30.7% | 73.4% | 6.4 | 3.3, 12.4 | 0.000 |

| Readiness to change risky sexual behavior | 13.2% | 54.7% | 8.2 | 3.6, 18.9 | 0.000 |

| Plan for HIV transmission risk reduction* | 24.7% | 61.5% | 5.3 | 2.7, 10.2 | 0.000 |

| Addressed with HIV-infected patient seen at routine visit | |||||

| Number of recent sex partners | 68.7% | 90.5% | 4.3 | 1.6, 11.7 | 0.001 |

| Sex of all patient’s sexual partners | |||||

| Trainee in workplace without counseling protocols | 32.0% | 52.0% | 2.2 | 0.9, 5.7 | 0.103 |

| Trainee in workplace with counseling protocols | 21.0% | 78.0% | 7.3 | 2.2, 24.5 | 0.001 |

| HIV status of sex partner(s) | 85.5% | 96.9% | 5.4 | 1.3, 23.4 | 0.023 |

| Use of condom or other barrier method | 90.7% | 98.5% | 6.5 | 0.8, 55.8 | 0.086 |

| Presence of STI symptoms* | 55.2% | 84.1% | 4.3 | 2.0, 9.2 | 0.000 |

| Type of sex (oral, anal, or vaginal)* | 20.3% | 72.9% | 10.5 | 4.6, 24.0 | 0.000 |

| For women: pregnancy risk | 80.5% | 90.5% | 1.8 | 0.7, 4.7 | 0.246 |

| Use of alcohol or other drugs | 79.7% | 84.4% | 1.4 | 0.6, 3.0 | 0.477 |

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy;

key elements of the counseling algorithm

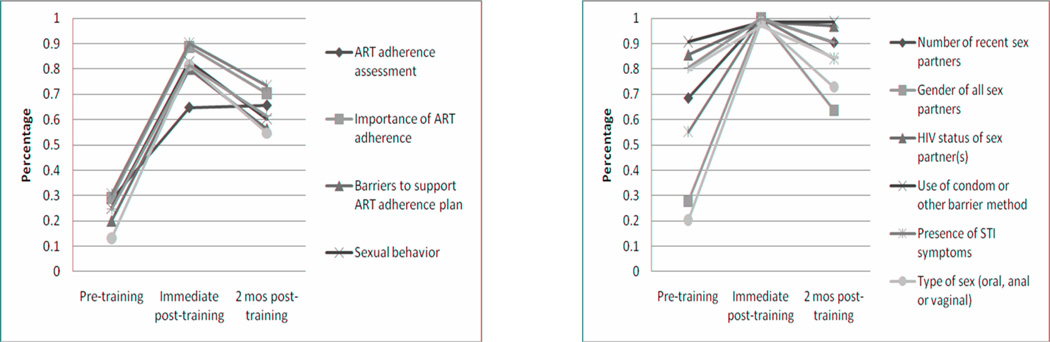

In most cases, there was no difference in the effect of the training on clinical practice among those trainees whose workplace already had a complete set of counseling protocols in place versus those whose workplaces did not. However, we did observe an improvement in discussion of the sexual partner’s sex among trainees in workplaces with protocols previously in place, with OR 7.3 (95% CI 2.2–24.5) versus a non-significant OR of 2.2 (0.9–5.7). Persistence of nurse assessment and counseling behaviors tended to decline somewhat in the time period between receiving the counseling intervention training and being back in practice for 2 months (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. HIV nurse counseling practices over time.

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy; STI = sexually transmitted infection; mos = months

Discussion

We found that an integrated counseling algorithm for medication adherence and positive prevention risk reduction supported significantly increased reports of routine ART adherence and sexual risk assessment, message delivery, and risk reduction plan-making with patients among nurses involved in direct care of patients with HIV in Kenya. It remains to be explored whether such changes could be sustained beyond the relatively short follow-up period we observed, or would require booster counseling training and support. Provider “drift” from counseling algorithms has been noted in a variety of studies (Miller & Rollnick, 2002).

Given the importance of ongoing adherence to reduce the likelihood of developing viral resistance, morbidity, and mortality, it was noteworthy that consistent ART adherence assessment was reported by fewer than one in three nurses at baseline (28.6%) but improved significantly following the intervention training. Likewise, prior to receiving the intervention, only one in four of these clinically-experienced HIV nurses reported routinely asking about patients’ sexual risks, but this level improved with training. These issues are not restricted to low- versus high-resource settings. Studies of U.S. providers have found that sexual risk assessment is highly variable (Duffus et al., 2003; Metsch et al., 2004; St. Lawrence et al., 2002), a pattern also noted in Kenyan STD clinics (O'Hara et al., 2001).

The training intervention appeared to increase nurses’ comfort levels with discussing the sex of patients’ partners, notable given that homophobia can be widespread in some African health care settings (Lane, Mogale, Struthers, McIntyre, & Kegeles, 2008). Allowing open discussions (e.g., about homophobia) by role-modeling faculty during the training, along with testimonials by a panel of PLWH, may have supported changing attendee biases. A sizable proportion of the nurses indicated that they had patients who were men who have sex with men (14%), injecting drug users (24%), and female sex workers (61%).

Limitations of this study included the use of self-report measures, a non-randomized intervention, a short follow-up period, and attendees with heterogeneous education backgrounds. Provider self-report of prevention health counseling practices may overestimate actual practice patterns. Future research could include nurse-patient interaction observation, perhaps using standardized patients (Carney & Ward, 1998; Seung et al., 2008), and should assess longer-term impact on HIV-infected patient behaviors, as well as the feasibility for scaling up such integrated counseling interventions in high-volume HIV clinics in resource-limited settings. Time motion studies could be conducted to ensure that the burden on already stressed health care providers does not increase substantially. Given the costs involved in doing in-person trainings (in terms of nurses being pulled away from the workplace, as well as travel and staffing needs), innovative training models also should be explored. We are currently engaged in a trial with a large HIV clinic in central Kenya studying the delivery of the Pambazuko counseling intervention on personal digital assistants (PDAs) in a self-study mode that may be more scalable than conducting in-person trainings. That study also is looking at booster sessions to assess trends in counseling over time (NIH 1 R24 HD056799). Lessons learned from both in-person and digital trainings will advance our understanding of the modalities and content that can best equip providers to provide consistent assessment and evidence-based counseling over time to their highest need patients.

This study demonstrated the potential utility of a nurse-delivered intervention to support HIV treatment adherence and reduction of secondary HIV transmission. The data suggest that nurses receiving relatively limited training can incorporate evidence-based counseling to actively assess and support the needs of PLWH in high-burden settings.

Table 1.

HIV Nurse Knowledge and Attitudes Scores Over Time

| Knowledge score* (range 0–12) | ||

| M | SD | |

| Baseline | 8.82 | 2.62 |

| Immediate post-training | 11.55 | 0.99 |

| 2 months post-training | 11.02 | 1.61** |

| Bonferroni test for equality of means | p-value | |

| Baseline to immediate post | < 0.001 | |

| Baseline to 2-month follow-up | < 0.001 | |

| Immediate post to 2-month follow-up | 0.317 | |

| Attitude score** (range 0–18) | ||

| M | SD | |

| Baseline | 14.76 | 3.23 |

| Immediate post-training | 17.46 | 1.18 |

| 2 months post-training | 17.11 | 1.26 |

| Bonferroni test for equality of means | p-value | |

| Baseline to immediate post | < 0.001 | |

| Baseline to 2-month follow-up | < 0.001 | |

| Immediate post to 2-month follow-up | 1.0 |

Note. M = Mean; SD = standard deviation;

Comprised of 5 items regarding antiretrovirals and adherence;

Comprised of 6 items regarding sexual behaviors and positive prevention

Clinical Considerations.

Nurses can effectively deliver interventions to support HIV treatment adherence and reduce secondary HIV transmission among persons living with HIV (PLWH).

Nurses would benefit from training to help them incorporate evidence-based counseling to actively assess and support the needs of PLWH.

Counseling areas of concern include ART adherence, discussions about sexual behaviors, universal prevention messaging, and creating plans with PLWH to reduce transmission risk behaviors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH, NIAID grant 3 P30 AI027757-18S1. We are deeply grateful to Jeff Rohwer of Incendia Health Studios; staff of the Ganjoni Clinic, study expert advisory group and faculty Beatrice Jakait, Naomi Mutea, Elizabeth Mweha, Alice Njoroge, Sr. Pauline Nthenya, Rose Ochieng, James Okongo, Regina Owino; Jane Simoni, Kishorchandra Mandaliya; and the study participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article (including relationships with pharmaceutical companies, biomedical device manufacturers, grantors, or other entities whose products or services are related to topics covered in this manuscript) that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

A. Kurth: As study PI was involved in design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting, editing and final approval of the manuscript.

L McClelland: As Study Coordinator was involved in study design and operations, data analysis and interpretation, drafting, editing and final approval of the manuscript.

G. Wanje: Was involved in data analysis and interpretation, drafting, editing and final approval of the manuscript.

A. Ghee: Was involved in data analysis and interpretation, drafting, editing and final approval of the manuscript.

N. Peshu: Was involved in editing and final approval of the manuscript.

E. Mutunga: Was involved in editing and final approval of the manuscript.

W. Jaoko: Was involved in editing and final approval of the manuscript.

M. Storwick: Was involved study operations and in data interpretation, editing and final approval of the manuscript.

K.K. Holmes: Was involved in editing and final approval of the manuscript.

R.S. McClelland: Was involved study design, data interpretation, in editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ann E. Kurth, University of Washington, Seattle WA USA.

Lauren McClelland, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

George Wanje, Municipality of Mombasa, Mombasa, Kenya.

Annette E. Ghee, World Vision, Seattle, WA, USA.

Norbert Peshu, KEMRI Centre for Geographic Medicine Research-Coast, Kilifi, Kenya.

Esther Mutunga, Municipality of Mombasa, Mombasa, Kenya.

Walter Jaoko, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

Marta Storwick, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

King K. Holmes, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Scott McClelland, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

References

- Amico KR, Harman JJ, Johnson BT. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: A research synthesis of trials, 1996 to 2004. Journal of Acquired {mmune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(3):285–297. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197870.99196.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, Wamai N, Bikaako-Kajura W, Were W, Mermin J. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2006;20(1):85–92. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196566.40702.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell RE, Nassozi J, Marum E, Mubangizi J, Malamba S, Dillon B, Mermin JH. Living with discordance: Knowledge, challenges, and prevention strategies of HIV-discordant couples in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2005;17(8):999–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540120500100718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney PA, Ward DH. Using unannounced standardized patients to assess the HIV preventive practices of family nurse practitioners and family physicians. The Nurse Practitioner. 1998;23(2):56–58. 63, 67–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Society of America, HIV Prevention in Clinical Care Working Group. Recommendations for incorporating human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;38(1):104–121. doi: 10.1086/380131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, Passin WF, Rama SM, Herbst JH, Stall R. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2006;20(2):143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffus WA, Barragan M, Metsch L, Krawczyk CS, Loughlin AM, Gardner LI, del Rio C. Effect of physician specialty on counseling practices and medical referral patterns among physicians caring for disadvantaged human immunodeficiency virus-infected populations. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;36(12):1577–1584. doi: 10.1086/375070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, Amico RK, Bryan A, Friedland GH. Clinician-delivered intervention during routine clinical care reduces unprotected sexual behavior among HIV-infected patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(1):44–52. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000192000.15777.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, Reid AE. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: Research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(5):642–650. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194495.15309.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Mogale T, Struthers H, McIntyre J, Kegeles SM. "They see you as a different thing:" The experiences of men who have sex with men with healthcare workers in South African township communities. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2008;84(6):430–433. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamba SS, Mermin JH, Bunnell R, Mubangizi J, Kalule J, Marum E, Downing R. Couples at risk: HIV-1 concordance and discordance among sexual partners receiving voluntary counseling and testing in Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39(5):576–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi C, Crittenden KS, Cho YI, Engler J, Warnecke R. Minimal smoking cessation interventions in prenatal, family planning, and well-child public health clinics. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(3):423–427. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Richardson JL, Crepaz N, Stoyanoff S, Milam J, Kemper C, McCutcheon A. Are HIV care providers talking with patients about safer sex and disclosure?: A multi-clinic assessment. AIDS. 2002;16(14):1953–1957. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews C, Guttmacher SJ, Coetzee N, Magwaza S, Stein J, Lombard C, Coetzee D. Evaluation of a video based health education strategy to improve sexually transmitted disease partner notification in South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(1):53–57. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland L, Wanje G, Kashonga F, McClelland RS, Kiarie J, Mandaliya K, Peshu N, Holmes KK, Kurth A. Understanding the risk context of HIV and sexual behaviour following antiretroviral therapy rollout in a population of high-risk women in Kenya. AIDS Education & Behavior. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.4.299. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metsch LR, Pereyra M, del Rio C, Gardner L, Duffus WA, Dickinson G, Greenberg AE. Delivery of HIV prevention counseling by physicians at HIV medical care settings in 4 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1186–1192. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morin SF, Koester KA, Steward WT, Maiorana A, McLaughlin M, Myers JJ, Chesney MA. Missed opportunities: Prevention with HIV-infected patients in clinical care settings. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;36(4):960–966. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara HB, Voeten HA, Kuperus AG, Otido JM, Kusimba J, Habbema JD, Ndinya-Ochola JO. Quality of health education during STD case management in Nairobi, Kenya. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2001;12(5):315–323. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JL, Milam J, Stoyanoff S, Kemper C, Bolan R, Larsen RA, McCutchan A. Using patient risk indicators to plan prevention strategies in the clinical care setting. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37(Suppl 2):S88–S94. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140606.59263.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg N, Bachanas P, Bollini A, Poulsen M, Ackers M, Muhenje O. Adapting an evidence-based positive prevention intervention for African HIV clinic; Paper presented at the National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, Georgia. 2007. Dec 2–5, [Google Scholar]

- Samb B, Celletti F, Holloway J, Van Damme W, De Cock KM, Dybul M. Rapid expansion of the health workforce in response to the HIV epidemic. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(24):2510–2514. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seung KJ, Bitalabeho A, Buzaalirwa LE, Diggle E, Downing M, Bhatt Shah M, Gove S. Standardized patients for HIV/AIDS training in resource-poor settings: The expert patient-trainer. Academic Medicine. 2008;83(12):1204–1209. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31818c72ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Marks G, Crepaz N. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load. A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S23–S35. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248342.05438.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Lawrence JS, Montano DE, Kasprzyk D, Phillips WR, Armstrong K, Leichliter JS. STD screening, testing, case reporting, and clinical and partner notification practices: A national survey of U.S. physicians. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(11):1784–1788. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Pace AE. Problem based learning in chronic disease management: A review of the research. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;77(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]