Abstract

The biodegradation of steroids is a crucial biochemical process mediated exclusively by bacteria. So far, information concerning the anoxic catabolic pathways of androgens is largely unknown, which has prevented many environmental investigations. In this work, we show that Sterolibacterium denitrificans DSMZ 13999 can anaerobically mineralize testosterone and some C19 androgens. By using a 13C-metabolomics approach and monitoring the sequential appearance of the intermediates, we demonstrated that S. denitrificans uses the 2,3-seco pathway to degrade testosterone under anoxic conditions. Furthermore, based on the identification of a C17 intermediate, we propose that the A-ring cleavage may be followed by the removal of a C2 side chain at C-5 of 17-hydroxy-1-oxo-2,3-seco-androstan-3-oic acid (the A-ring cleavage product) via retro-aldol reaction. The androgenic activities of the bacterial culture and the identified intermediates were assessed using the lacZ-based yeast androgen assay. The androgenic activity in the testosterone-grown S. denitrificans culture decreased significantly over time, indicating its ability to eliminate androgens. The A-ring cleavage intermediate (≤500 μM) did not exhibit androgenic activity, whereas the sterane-containing intermediates did. So far, only two androgen-degrading anaerobes (Sterolibacterium denitrificans DSMZ 13999 [a betaproteobacterium] and Steroidobacter denitrificans DSMZ 18526 [a gammaproteobacterium]) have been isolated and characterized, and both of them use the 2,3-seco pathway to anaerobically degrade androgens. The key intermediate 2,3-seco-androstan-3-oic acid can be used as a signature intermediate for culture-independent environmental investigations of anaerobic degradation of C19 androgens.

INTRODUCTION

The presence of steroid hormones in the environment has become a major issue in environmental science and policy because these compounds (e.g., estrogens at concentrations above 10 ng/liter) alter diverse physiological functions, including reproduction and development, in animals, especially the aquatic species (1–5). Due to their hydrophobicity and strong adsorption to sediments, they are poorly soluble in water and have only limited bioavailability in natural environments (6). Conventionally, estrogens have attracted considerable attention due to their structural stability, persistence in the environment, and extremely strong endocrine-disrupting activity (1, 5, 7–9). Recent studies also documented masculinization of freshwater wildlife exposed to androgens in polluted rivers (10, 11).

Steroid hormones are discharged into the environment via various routes. They are excreted through the urinary tracts of vertebrates after modifications (e.g., glucuronide and sulfate conjugations) (12, 13). They are also detected in animal feces (14). Animal manure thus contains large amounts of steroid hormones, and the land application of livestock manure as fertilizer is considered one of the major sources of steroid hormones released to the environment (15). Municipal sewage biosolids are also an important source of steroid hormones in the environment (16). In addition, it has been reported that steroid hormones contaminate aquatic environments through leaching from manure-treated agricultural fields (17).

Steroid hormones have been detected in effluents from wastewater treatment plants and rivers worldwide at concentrations in the ng/liter range (18–24). For example, Chang et al. (19) documented five classes of steroid hormones occurring at discharge sites and in rivers in Beijing, China. According to their investigations, androgens were the most abundant steroids and were detected in total concentrations of up to 480 ng/liter in rivers and 1,887 ng/liter at discharge sites. These data suggest the inefficient removal of androgens in wastewater treatment plants.

Biodegradation has been proposed as a crucial mechanism for removing steroid hormones from the environment and engineered systems (12, 25, 26). In the last few decades, various androgen-degrading aerobic bacteria were isolated and characterized (27–29). Coulter and Talalay first established the oxygen-dependent pathway (the 9,10-seco pathway) for the degradation of testosterone by aerobes (30). This is the most widely studied pathway for aerobic androgen biodegradation (28). In contrast to the case for the well-investigated aerobic degradation pathways, there is still a lack of knowledge about androgen-degrading anaerobes and the biochemical mechanisms involved in anoxic androgen biodegradation (31, 32). Recent studies indicated that anoxic sediments and soil may be reservoirs for steroid compounds (6, 15). Some evidence suggests that steroids in soil could be mineralized by microbial activity even when oxygen is not available (33–35). In addition, a recent study on the elimination of steroid hormones in a municipal sewage treatment plant found that many of the detected androgens (for example, 80% of detected androsta-1,4-diene-3,17-dione [ADD]) were eliminated by microbial activities in the anaerobic tanks (22).

In addition to the environmental concerns, microbial steroid biodegradation has also potential applications in pharmacy and medicine (36, 37). Numerous studies have reported the microbial production of androst-4-en-3,17-dione (AD) and ADD from inexpensive cholesterol and phytosterols (27, 38). Additional interest is due to the potential applications of steroid-transforming enzymes with high regio- and stereo-specificity in the industrial synthesis of steroids (37).

We recently proposed an anaerobic testosterone degradation pathway (the 2,3-seco pathway) adopted by a gammaproteobacterium, Steroidobacter denitrificans (Sdo. denitrificans) DSMZ 18526 (39). The oxygenase-independent mechanism of the steroidal A-ring cleavage is highly comparable to that operating in anoxic cyclohexanol catabolism by Alicycliphilus denitrificans DSMZ 14773 (39). However, there is a dearth of information concerning the carbon removal mechanisms involved in anoxic testosterone catabolism. Furthermore, the androgenic activity of the intermediates needs to be determined. The distribution of the 2,3-seco pathway among testosterone-degrading anaerobes also remains unclear. Prior to this study, Sdo. denitrificans DSMZ 18526 was the only known testosterone-degrading anaerobe (40–42).

BLAST analysis has indicated that Sterolibacterium strains can be detected in the natural environment and engineered systems (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Among them, Sterolibacterium denitrificans (S. denitrificans) DSMZ 13999, a betaproteobacterium, was reported to degrade cholesterol both under oxic and anoxic conditions (43–46). In this study, the ability of S. denitrificans to degrade C18 and C19 steroid hormones under anoxic conditions was investigated. We applied a 13C-metabolomic approach to show that S. denitrificans uses the 2,3-seco pathway to anaerobically degrade androgens. The androgenic activities of the bacterial culture and the identified intermediates were then assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and bacterial strains.

[4-14C]testosterone was obtained from Perkin-Elmer. [2,3,4-13C]testosterone was purchased from Isosciences. The chemicals used were of analytical grade and were purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker, Merck, or Sigma-Aldrich. 3,17-Dihydroxy-9,10-seco-androsta-1,3,5(10)-triene-9-one, 3-hydroxy-9,10-seco-androsta-1,3,5(10)-triene-9,17-dione, 1-testosterone, androst-1-en-3,17-dione, 17-hydroxy-1-oxo-2,3-seco-androstan-3-oic acid (2,3-SAOA), and 1,17-dioxo-2,3-seco-androstan-3-oic acid were produced as described elsewhere (39, 47). Sterolibacterium denitrificans DSMZ 13999 was purchased from the Deutsche Sammlung für Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ), Braunschweig, Germany. Comamonas testosteroni ATCC 11996 was obtained from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center (BCRC), Hsinchu, Taiwan.

Androgen and estrogen utilization kinetics.

The preparation of the denitrifying media and the anoxic in vivo assays were performed in an anaerobic chamber containing 95% nitrogen and 5% hydrogen gas. S. denitrificans (resting-cell assays; total proteins, 294 μg/ml) was incubated with individual androgens (ADD, androsterone [ADR], epiandrosterone [EADR], 19-nor-4-androsten-3,17-diol [NADL], or testosterone) or estrogens (17α-estradiol, 17β-estradiol, estriol, estrone, or 17α-ethinylestradiol) at initial concentrations ranging from 5 to 50 mg/liter under denitrifying conditions. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (cyclodextrin) (0.5% [wt/vol]) was added to the culture medium prepared according to a published procedure (46). Substrate utilization kinetics tests were performed in a series of 2.2-ml Eppendorf tubes containing 1 ml of resting cell suspension. The steroid stock solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and the final DMSO concentration was adjusted to 0.5% (vol/vol). The resulting cell suspension was anaerobically incubated at 28°C with shaking (180 rpm) for 2 h. We measured the amount of residual steroids using high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) and determined the protein content of the S. denitrificans cell suspension using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. The determination of Monod kinetic parameters was carried out as described before (48).

Anaerobic growth of S. denitrificans on [4-14C]testosterone.

In the following experiments involving steroid quantification, 17α-ethinylestradiol (final concentration, 50 μM), which cannot be utilized by S. denitrificans, was added to bacterial cultures to serve as an internal control. In a denitrifying fed-batch culture (100 ml), S. denitrificans cells were incubated with 1 mM testosterone containing [4-14C]testosterone (1 × 108 dpm). Nitrate (10 mM) was added to the culture when the nitrate added initially (10 mM NaNO3) was consumed. The fed-batch culture (initial total proteins, 32 μg/ml) was carried out in a 125-ml glass bottle sealed with a rubber stopper. The headspace (25 ml) of the culture was connected to a 125-ml glass bottle containing 100 ml of 5 M NaOH, which trapped 14CO2 produced by the S. denitrificans cells. A Tygon tube (2 mm in inner diameter and 25 cm long) was used for the connection. Every 12 h (0 to 60 h), samples (0.5 ml) were withdrawn from the 5 M NaOH solution. Ten minutes before each sampling, nitrogen gas (ca. 50 ml) was used as a carrier gas to expel the residual 14CO2 from the bacterial culture at a flow rate of 5 ml/min. At the same time intervals, samples (2.5 ml) were withdrawn from the bacterial culture. The culture samples (0.5-ml samples, 3 replicates) were extracted with the same volume of ethyl acetate three times to isolate the residual [4-14C]testosterone from the water fraction. The ethyl acetate was evaporated, and the residue was redissolved in 0.5 ml of ethanol. The water fraction, ethanol, and 5 M NaOH samples (0.1 ml) were added to 1.9 ml of Ultima Gold high-flash-point LSC scintillation cocktail reagent (Perkin-Elmer), and the amount of 14C was determined by liquid scintillation counting (Tri-Carb 2900 TR liquid scintillation analyzer [Perkin-Elmer]). The remaining ethanol samples (0.4-ml samples, 3 replicates) were concentrated to 50 μl, and the testosterone in the ethanol samples was quantified by HPLC. The protein content and nitrate concentration in the samples were determined as described below. After 60 h of incubation, the bacterial cells were harvested twice by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 20 min), and the remaining cells were recovered by passing the supernatant through a 0.22-μm nitrocellulose membrane filter (Millipore). The S. denitrificans cells were lyophilized for 1 week, and the freeze-dried biomass was weighed.

Anoxic transformation of [2,3,4-13C]testosterone by the batch cultures.

In the following biotransformation assays, S. denitrificans was first anaerobically grown in fed-batch cultures (nitrate was continuously supplied). The amounts of residual substrates (testosterone, cholesterol, or palmitate [49]) in the denitrifying S. denitrificans cultures were monitored using HPLC. The utilization of last two substrates can avoid the HPLC detection of C19 catabolic intermediates in the precultures. We then used the log-phase S. denitrificans cultures to transform steroid substrates in a batch mode (no additional nitrate was given during the incubation).

After the consumption of 2 mM testosterone, 10 ml of the anoxic S. denitrificans culture (200 ml) was transferred into two 12-ml glass bottles. The two cultures were subsequently fed with 2 mM testosterone (unlabeled testosterone and [2,3,4-13C]testosterone were mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio) under denitrifying conditions. From an S. denitrificans culture containing 5 mM nitrate, the sample (1 ml) was withdrawn after 4 h of incubation at 28°C. From another batch culture containing 15 mM nitrate, the sample (1 ml) was withdrawn after 16 h of denitrifying incubation. The ethyl acetate-extractable intermediates were identified using ultraperformance liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-HRMS).

Production of 6α-hydroxyandrost-4-en-3,17-dione.

S. denitrificans (2 liters) was anaerobically grown with 2 mM testosterone. After the consumption of 1 mM testosterone, 1 mM 3-mercaptopropionate (an inhibitor of acyl coenzyme A [acyl-CoA] dehydrogenase [50, 51]) was added to the culture, and the incubation was continued for an additional 10 h. Separation of ethyl acetate extracts was carried out using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and HPLC. The structural elucidation of the HPLC-purified intermediate was performed with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and UPLC-HRMS.

Quantification of steroids and androgenic activity in a denitrifying S. denitrificans culture.

After consumption of 2 mM cholesterol, a S. denitrificans culture (500 ml; total proteins, 264 μg/ml) was used to transform 0.5 mM testosterone. The samples (5 ml) were withdrawn every 1 h (0 to 10 h). The steroid intermediates extracted from the cultural samples (4 ml) were quantified using HPLC. The steroids extracted from the remaining samples (1 ml) were dissolved in 10 μl of DMSO, and their androgenic activity was tested using the lacZ-based assay.

Growth of S. denitrificans under various oxygen concentrations.

An S. denitrificans culture (250 ml) containing potassium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0), 10 mM NH4Cl (the nitrogen source), and 10 mM NaNO3 (the potential electron acceptor) was first anaerobically grown on 1 mM palmitic acid (45). After palmitic acid was completely consumed, 0.5 mM testosterone and 10 mM nitrate were added to the bacterial culture. Portions (50 ml) of the resulting culture were transferred to three 500-ml glass bottles and were incubated under various concentrations of oxygen (headspace, 450 ml; 0, 5, and 20% [vol/vol]). Two cultures were prepared in an anaerobic chamber. In the case of the microaerobic culture, 24 ml of oxygen gas was injected into the anoxic headspace after passage through a 0.22-μm membrane filter (Millipore). Samples (1 ml) were retrieved every 12 h (0 to 72 h) to measure the consumption of testosterone and nitrate and to detect the production of the ring cleavage intermediates.

Aerobic growth of S. denitrificans and C. testosteroni in the absence of nitrate.

S. denitrificans was aerobically grown in a phosphate-buffered culture without nitrate (50 ml). After the consumption of 2 mM testosterone (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.8 [optical path, 1 cm]), additional testosterone (2 mM) was added to the S. denitrificans culture. Testosterone (2 mM) was added to a C. testosteroni culture (OD600 = 1.0) grown in tryptic soy broth (BD Difco). Samples (1 ml) were withdrawn every 2 h (0 to 10 h), and the steroid metabolites were identified using UPLC-HRMS.

TLC.

The steroids were separated on silica gel aluminum thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates as described elsewhere (39).

HPLC quantification of androgens and estrogens in bacterial cultures.

The steroids extracted from the culture samples were separated and quantified using a reversed-phase Hitachi HPLC system. The separation was achieved on an analytical RP-C18 column [Luna 18(2), 5 μm, 150 by 4.6 mm; Phenomenex) incubated at 35°C. The mobile phase included a mixture of two solvents, A (0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid) and B (acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid). The separation was performed at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min with a gradient from 30% to 60% B within 60 min. The steroids were detected in the range of 200 to 300 nm using a photodiode array detector. The quantification of steroids was done from their respective peak areas using a standard curve of individual standards. Data shown are the means ± standard errors (SE) from three experimental measurements.

UPLC-HRMS.

The ethyl acetate-extractable samples and the HPLC-purified compound were analyzed using UPLC-HRMS as described before (39).

NMR spectroscopy.

The 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded at 27°C using a Bruker AV600_GRC 600-MHz NMR instrument. Chemical shifts (δ) were recorded and shown as ppm values with deuterated methanol (99.8%; 1H, δ = 3.31 ppm; 13C, δ = 49.0 ppm) as the solvent and internal reference.

Measurement of protein content and nitrate concentration.

The cell suspension (0.1 ml) was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of reaction reagent (Pierce BCA protein assay kit; Thermo Scientific). The protein content was determined using a BCA protein assay according to manufacturer's instructions with bovine serum albumin as the standard. The supernatant (0.1 ml) was diluted with 0.9 ml double-distilled water, and the nitrate was determined using the cadmium reduction method according to manufacturer's instructions (HI93728-01 nitrate reagent kit; Hanna Instruments).

Transformation of yeast cells with the plasmid pRR-AR-5Z.

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae host stain (BY4727, trp−) was a gift from Wen-Hsiung Li, Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. The plasmid pRR-AR-5Z (23058) was purchased from Addgene. The transformation was performed according to an electroporation protocol (52). The resulting transformants were grown on selective agar plates containing 6.7 g/liter yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (BD Difco), 20 g/liter glucose, and 1.92 g/liter SC-Trp (Sunrise Science). The presence of the plasmid pRR-AR-5Z in the yeast cells was confirmed using PCR.

lacZ-based yeast androgen bioassay.

The yeast androgen bioassay was conducted as described by Fox et al. (53) with slight modifications. Briefly, the individual androgens or cell extracts were dissolved in DMSO, and the final concentration of DMSO in the assays (200 μl) was 1% (vol/vol). The resulting DMSO solutions (2 μl) were added to yeast cultures (198 μl; initial OD600, 0.5) in a 96-well microtiter plate. The β-galactosidase activity was determined after 18 h of incubation at 30°C. The yeast suspension (25 μl) was added to Z buffer (225 μl) containing o-nitrophenol-β-d-galactopyranoside (2 mM), and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The reactions were stopped by adding 100 μl of 1 M sodium carbonate, and the amount of nitrophenol product was measured at 420 nm on a plate spectrophotometer. Data shown are the means ± SE for three replicates.

RESULTS

Utilization of androgens and estrogens by S. denitrificans.

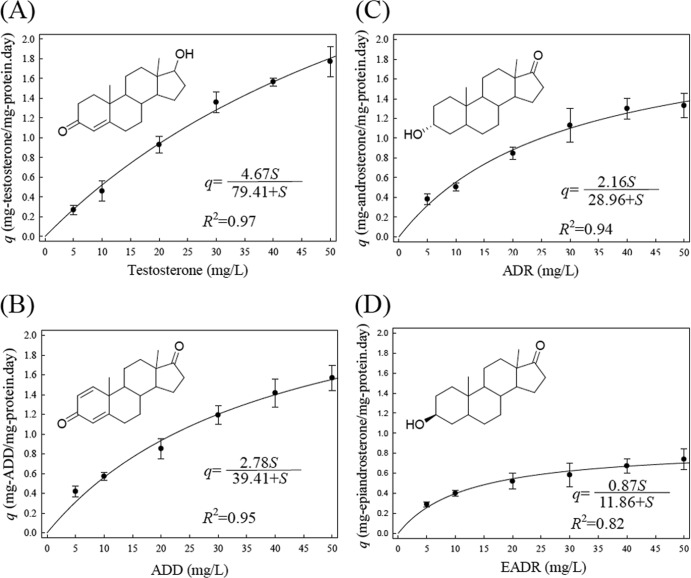

Androgens and estrogens often detected in the environment (18–20, 22–24) were tested for the substrate utilization pattern of S. denitrificans. In this study, cyclodextrin (0.5% [wt/vol]), a carrier molecule, was added to all cell suspensions and bacterial cultures to improve the solubility of steroids. Addition of cyclodextrin can avoid underestimation of the substrate utilization rate due to poor solubility of steroids in media. The maximum specific substrate utilization rates (qm) and the estimated half-velocity constants (Ks) for these androgens are shown in Fig. 1. Testosterone was the most suitable steroid substrate for S. denitrificans. In the presence of cyclodextrin, the qm and Ks values for testosterone were 4.67 mg substrate/mg protein/day and 79.41 mg/liter, respectively. In the absence of cyclodextrin, the qm value for testosterone was 0.34 mg substrate/mg protein/day (data not shown). In contrast, EADR seems to be less favorable. We observed no substrate utilization for C18 steroids, including NADL and estrogens. The data indicated that under denitrifying conditions, S. denitrificans could utilize C19 androgens, but not C18 steroids, as an energy source. However, it was unclear if S. denitrificans mineralized androgens in the absence of oxygen or if it just transformed testosterone to other compounds.

FIG 1.

Monod degradation kinetics of androgens by resting cell suspensions of S. denitrificans. The increase of bacterial biomass within 2 h was negligible (<3%). The solid lines represent fitted Monod kinetic curves. The data are from one representative experiment of four individual experiments.

S. denitrificans mineralizes testosterone during denitrifying growth.

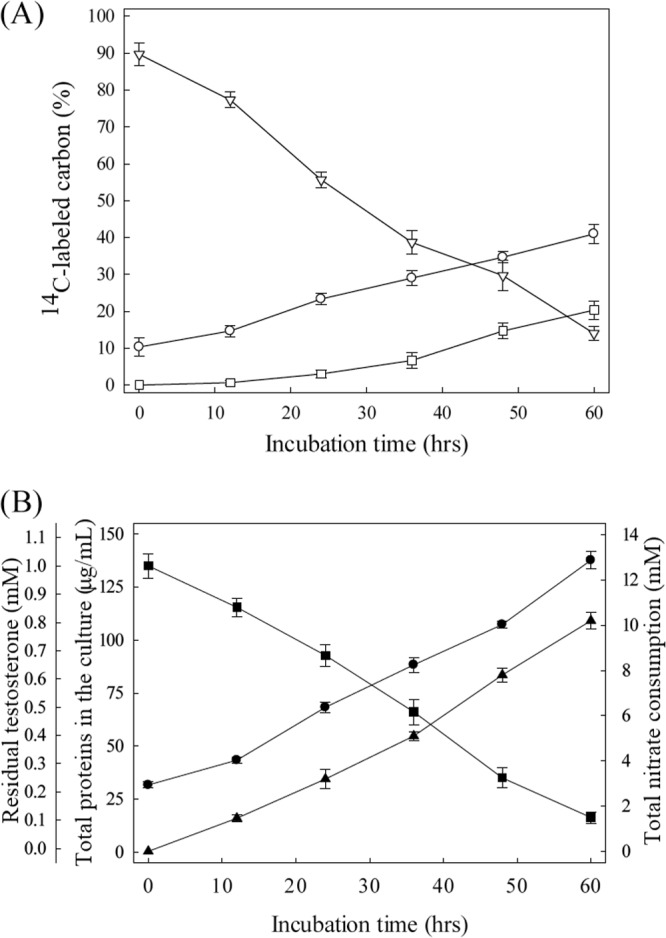

Separation of S. denitrificans cells from the residual testosterone by centrifugation was not successful. Therefore, the culture samples were extracted with ethyl acetate to recover the residual testosterone from the aqueous fraction. As shown in Fig. 2, the decrease in the residual [4-14C]testosterone in the medium was accompanied by the accumulation of radioactive 14C in the bacterial biomass and an increase in the amount of trapped 14CO2 (Fig. 2A). After 60 h of anaerobic growth of S. denitrificans, the total 14C recovered was 75% (14% 14C remained mainly as testosterone in the medium, 20% 14C was trapped by the 5 M NaOH solution, and 41% 14C was assimilated in biomass) (Fig. 2A). Given the stoichiometric results shown below (0.32 mM testosterone [32%] was assimilated in biomass, and 0.57 mM testosterone [57%] was mineralized), most of the lost 14C may due to the incomplete trapping of 14CO2 using NaOH solution.

FIG 2.

Denitrifying growth of S. denitrificans DSMZ 13999 on testosterone. (A) Assimilation and mineralization of [4-14C]testosterone in the bacterial culture. Symbols: ▽, ethyl acetate-extractable 14C; ○, assimilated 14C; □, trapped 14CO2. (B) Nitrate consumption and testosterone utilization in the same bacterial culture. Symbols: ●, bacterial growth; ■, residual total testosterone; ▲, nitrate consumption. The data shown are the means ± SE of three experimental measurements.

The anaerobic growth of S. denitrificans (measured as the increase in the protein concentration) was accompanied by a decrease of residual testosterone and the consumption of nitrate (Fig. 2B). At the end of exponential growth phase (60 h), approximately 158 mg of dry cell mass per liter was produced, accounting for the consumption of 0.89 mM testosterone and 10.3 mM nitrate. Synthesis of bacterial biomass (158 mg/liter) can account for the consumption of 0.32 mM testosterone and 1.2 mM nitrate based on the assimilation equation (using C4H7O3 as the empirical formula for S. denitrificans biomass [45]): 20C19H28O2 + 77NO3− + 77H+ + 14H2O → 95C4H7O3 + 38.5N2.

Considering the testosterone and nitrate consumed for biomass synthesis, 0.57 mM testosterone and 9.1 mM nitrate should have been consumed in the dissimilation process. These data are in good agreement with the theoretical stoichiometry for complete oxidation of testosterone: C19H28O2 + 20NO3− + 20H+ → 19CO2 + 10N2 + 24H2O.

The complete oxidation of 1 mol testosterone yields 100 mol electrons. On the other hand, the reduction of 1 mol nitrate to molecular nitrogen (N2) requires 5 mol electrons. An electron recovery of 124% was calculated.

Identification of catabolic intermediates.

To investigate the 13C-labeled intermediates involved in anoxic testosterone degradation, we incubated two log-phase S. denitrificans cultures (10 ml) with [2,3,4-13C]testosterone. The two batch cultures contained different nitrate concentrations. The steroid substrate was composed of [2,3,4-13C]testosterone and unlabeled testosterone. Therefore, pairs of molecular adduct ions (with an m/z difference of 3) were observed in the mass spectra of testosterone-derived intermediates (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). After 4 h of anaerobic incubation, we detected a total of eight 13C-labeled compounds in the S. denitrificans culture containing 5 mM nitrate (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Note that the polar/ionic compounds such as 2,3-SAOA provided weak ion signals with the atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (APCI) method. These steroid compounds were identified by reference to the UPLC-HRMS behavior of steroid standards. The mass spectra of the 13C-labeled intermediates are given in Fig. S2B in the supplemental material. Of these, 1-testosterone (Fig. S2B3), 2,3-SAOA (Fig. S2B4), and androst-1-en-3,17-dione (Fig. S2B7) are characteristic intermediates involved in the 2,3-seco pathway (39). Interestingly, a saturated steroid, androstan-17β-ol-3-one (Fig. S2B8), was observed in the anoxic S. denitrificans culture. This compound was produced from testosterone by a reduction reaction, which requires electrons. The appearance of this reductive compound might contribute to the NADH/NAD+ cycle in S. denitrificans cells.

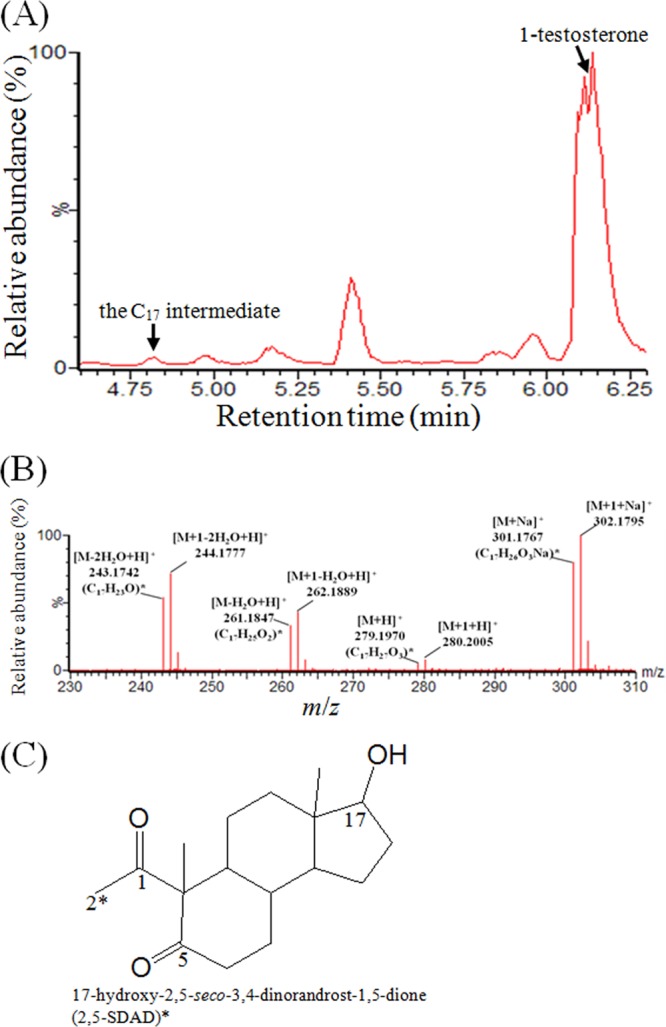

After 16 h of denitrifying incubation, a 13C-labeled intermediate with 17 carbons was identified in another batch culture (10 ml) containing 15 mM nitrate (Fig. 3). According to its electron spray ionization (ESI) mass spectrum, this compound is labeled with only one 13C (Fig. 3B), suggesting the removal of two 13C atoms from testosterone. We assumed that the C-3 and C-4 of this C17 intermediate were removed because (i) testosterone, the steroid substrate, was labeled with three 13C at C-2, C-3, and C-4 and (ii) in the case of 2,3-SAOA, the single bond between C-2 and C-3 was broken. So far, we cannot produce a sufficient amount of this C17 intermediate for NMR analysis. However, some clues suggest that this compound might have a chemical structure as shown in Fig. 3C. First, the ring cleavage product, 2,3-SAOA, has a carboxylic group at its C-3 which could be activated by a coenzyme A (CoA) ligation reaction. After the activation, a CH3-CO-SCoA molecule could be removed via the retro-aldol reaction, which results in a carbonyl group at the C-5 position. Second, this C17 compound was not observed when 1 mM 3-mercaptopropionate (an inhibitor of acyl-CoA dehydrogenase) was added to the in vivo biotransformation assay, suggesting that this intermediate may result from reactions similar to β-oxidation. Third, during the anaerobic incubation of S. denitrificans with testosterone, the 17-hydroxyl intermediates are usually more dominant than their 17-keto structures (see Fig. 5 and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 3.

UPLC-HRMS analysis of a 13C-labeled intermediate produced by the denitrifying S. denitrificans. (A) UPLC chromatogram of the ethyl acetate extract. (B) ESI mass spectra of the C17 intermediate. The predicted elemental composition was calculated using MassLynx mass spectrometry software (Waters). (C) Expected chemical structure. Critical carbon atoms in this compound are numbered according to the steroidal carbon numbering system. ∗, 13C atom.

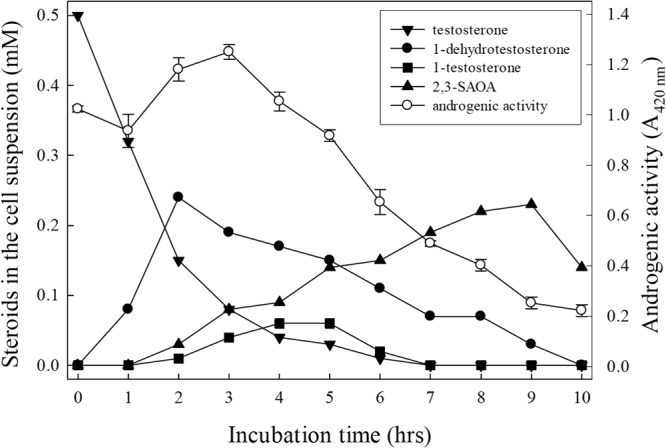

FIG 5.

Time course of intermediate production and androgenic activity of a denitrifying S. denitrificans culture. The A420 of the negative control, DMSO (1%, vol/vol), was set to zero.

Anaerobic incubation of S. denitrificans with testosterone and 3-mercaptopropionate.

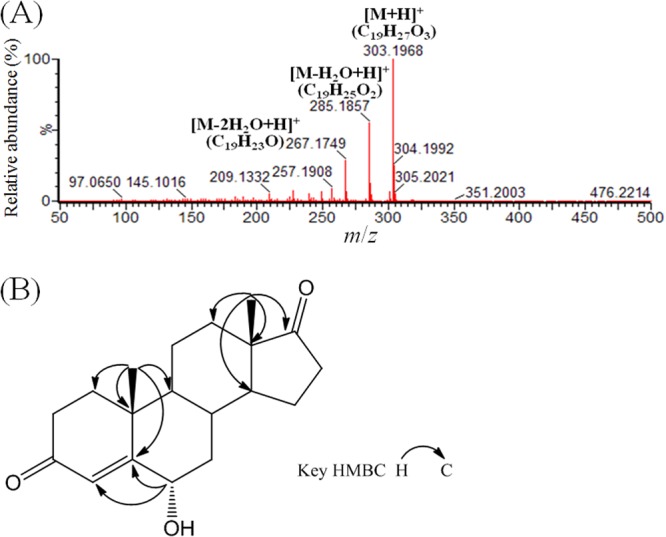

In a denitrifying culture (2 liters), S. denitrificans was grown with unlabeled testosterone and 3-mercaptopropionate (1 mM) for 10 h. Accumulation of 2,3-SAOA and an unprecedented intermediate occurred. The accumulation of the A-ring cleavage intermediate (2,3-SAOA) implies the participation of β-oxidation or similar reactions in the following catabolic steps. The other intermediate was purified by liquid-liquid extraction, TLC, and HPLC. The molecular formula of the HPLC-purified compound was analyzed using UPLC-HRMS. A protonated molecular ion ([M + H]+; m/z 303.1968) was observed in its APCI mass spectrum (Fig. 4A). The molecular formula of this compound was determined to be C19H26O3. Based on the NMR analysis (see the legend to Fig. S3 in the supplemental material for a detailed explanation), this steroid product was characterized as 6α-hydroxyandrost-4-en-3,17-dione (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Structural elucidation of 6α-hydroxyandrost-4-en-3,17-dione produced by S. denitrificans. (A) APCI mass spectrum. (B) Key heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation (HMBC) spectrum.

Sequential appearance of the catabolic intermediates in the denitrifying S. denitrificans culture.

We incubated a S. denitrificans batch culture (500 ml) with testosterone to track the sequential appearance of the catabolic intermediates and to determine the androgenic activity in the bacterial culture (Fig. 5). 1-Dehydrotestosterone was the first accumulated intermediate, and its peak appeared after 2 h of incubation. The strong positive slope for 2,3-SAOA indicates that it is the last detectable product. 1-Testosterone behaved like intermediates between 1-dehydrotestosteorne and 2,3-SAOA. The ethyl acetate extracts of the S. denitrificans culture were tested for their androgenic activity (Fig. 5). After 3 h of incubation, androgenic activity started to steadily decrease over time. Note that the accumulation of 2,3-SAOA did not result in an increase of androgenic activity.

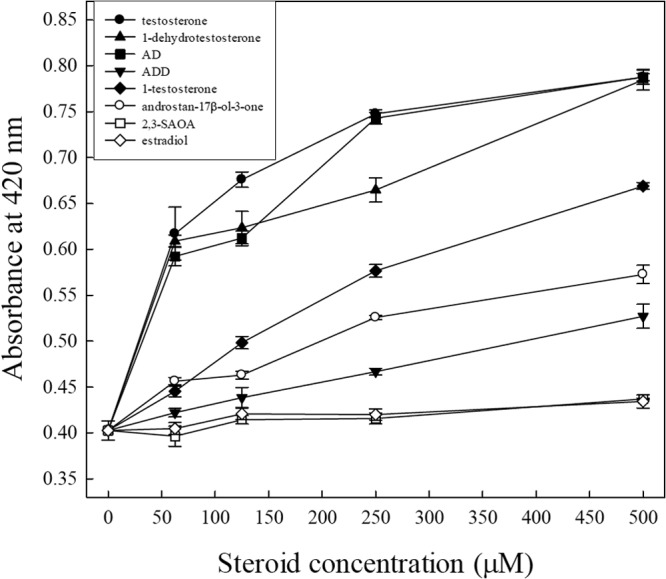

Androgenic activities of the intermediates involved in the 2,3-seco pathway.

We then determined the androgenic activities of the individual intermediates using a lacZ-based yeast androgen assay. A total of seven intermediates were tested. The results showed that testosterone, 1-dehydrotestosterone (DT), and AD exhibited comparable androgenic activity (Fig. 6). However, 1-testosterone, androstan-17β-ol-3-one, and ADD exhibited relatively weak activity. 2,3-SAOA, like estradiol (the negative control), had no detectable androgenic activity even at a concentration of 500 μM. These results are consistent with those for the ethyl acetate extracts of the S. denitrificans culture (Fig. 5), indicating that under anoxic conditions, S. denitrificans can eliminate the androgenic activity of testosterone by opening its sterane structure.

FIG 6.

Response of the yeast androgen bioassay to the individual intermediates. The results are from one representative of four individual experiments.

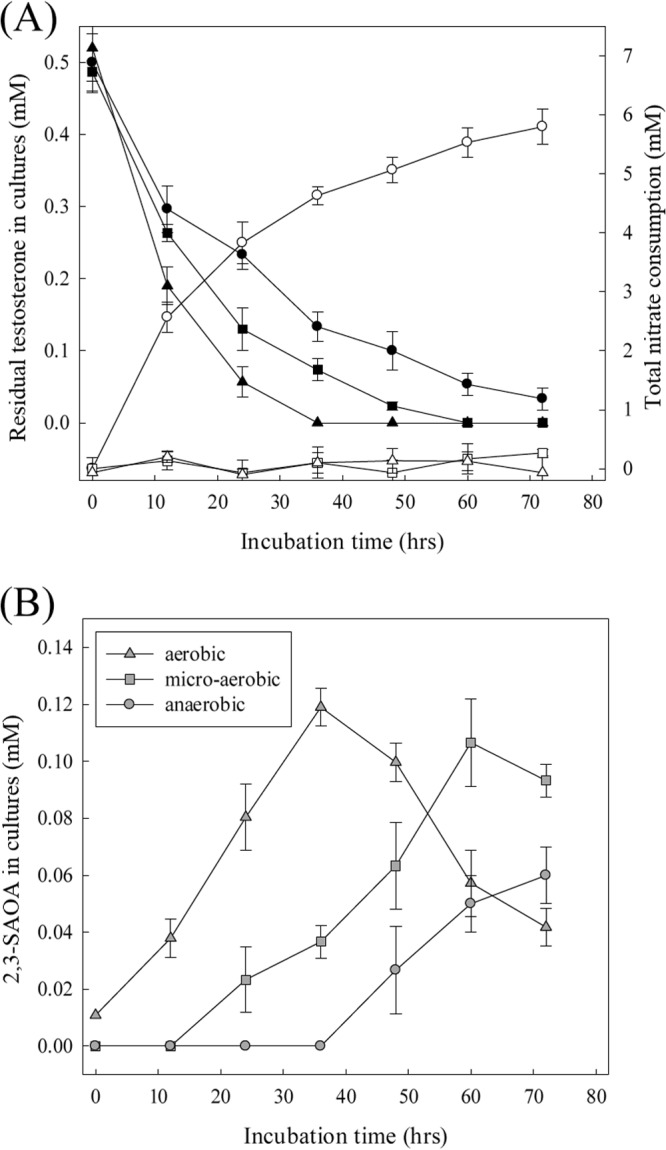

Testosterone degradation by S. denitrificans grown under various oxygen concentrations.

Under oxic conditions, testosterone was exhausted after 36 h of incubation. The slowest testosterone utilization was observed when oxygen was not available, with testosterone exhausted after 72 h of incubation (Fig. 7A). No apparent nitrate consumption was observed in the aerobic and microaerobic cultures, whereas in the anaerobic culture, 5.8 mM nitrate consumption accompanied the utilization of 0.47 mM testosterone (Fig. 7A). It is worth mentioning that the characteristic ring cleavage intermediate of the 9,10-seco pathway, 3,17-dihydroxy-9,10-seco-androsta-1,3,5(10)-triene-9-one, was not detected in the aerobic and microaerobic S. denitrificans cultures. In contrast, the production of 2,3-SAOA was observed in all bacterial cultures (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Testosterone catabolism by S. denitrificans proceeds via the 2,3-seco pathway regardless of oxygen conditions. (A) Testosterone and nitrate consumption in the S. denitrificans cultures. Symbols: ●, testosterone remaining in the anaerobic culture; ■, testosterone in the microaerobic culture; ▲, testosterone in the aerobic culture; ○, nitrate consumption under anaerobic conditions; □, nitrate consumption under microaerobic conditions; △, nitrate consumption under aerobic conditions. (B) 2,3-SAOA production in three S. denitrificans cultures. Representative data from one of three independent experiments are shown.

To investigate if the presence of nitrate might repress the expression of the catabolic genes involved in the classic 9,10-seco pathway, we aerobically grew S. denitrificans with testosterone and without nitrate. Comamonas testosteroni, which is known to degrade testosterone via the 9,10-seco pathway (28), was also tested for comparison (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material). S. denitrificans still produced 1-testosterone and 2,3-SAOA in the absence of nitrate (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material), indicating that nitrate is not repressing the expression of the S. denitrificans catabolic genes involved in the 9,10-seco pathway and confirming that the 2,3-seco pathway is the sole catabolic strategy for testosterone degradation in S. denitrificans.

DISCUSSION

Our results on [4-14C]testosterone mineralization, stoichiometry, and 13C-metabolomics indicate the complete degradation of testosterone by S. denitrificans. We detected more assimilated 14C signals (41%) than the assimilated testosterone (32%) calculated based on the theoretical assimilation equation. This may be because (i) polar catabolic intermediates derived from testosterone remain in the aqueous fraction after ethyl acetate extraction and/or (ii) individual carbons of the testosterone molecule have differential metabolic fates. It was demonstrated that Mycobacterium tuberculosis preferentially utilized different portions of the cholesterol molecule for energy generation and biosynthetic purposes (54). There is a large gap (25%) in the total 14C recovery. In addition to the incomplete capture of 14CO2, volatile metabolites produced in testosterone metabolism may not be trapped by the NaOH solution.

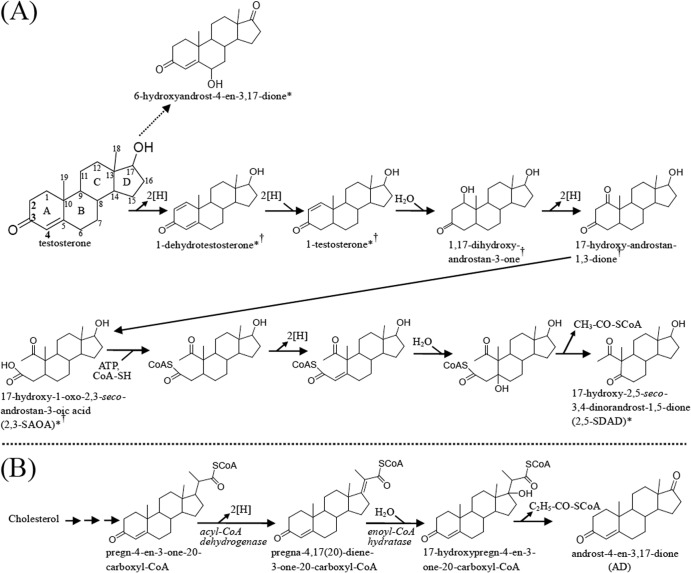

Based on the UPLC-HRMS data and the sequential appearance of the abundant intermediates in the denitrifying cultures, we found that S. denitrificans DSMZ 13999 also uses the 2,3-seco pathway to degrade testosterone. We identified a C17 intermediate using UPLC-HRMS. The loss of two 13C signals implies the removal of C-3 and C-4 from testosterone. This intermediate might be transformed from 2,3-SAOA by a series of CoA ligation, dehydrogenation, hydration, and retro-aldol reactions (Fig. 8A). Highly similar reactions have been demonstrated in the transformation of CoA ester of pregn-4-en-3-one-20-carboxylic acid to androst-4-en-3,17-dione (Fig. 8B) (55–57). In the cholesterol-degrading Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, the β-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase enzyme encoded by fadA5 catalyzes the thiolysis of C27 and C24 steroid-CoA esters (58). One propionyl-CoA moiety and one acetyl-CoA moiety are thus released through two cycles of β-oxidation. However, the additional propionyl-CoA cannot be released from pregn-4-en-3-one-20-carboxyl-CoA by a conventional β-oxidation due to the presence of the cyclopentane D ring. The two following steps, catalyzed by an acyl-CoA dehydrogenase and an enoyl-CoA hydratase, will produce a tertiary alcohol (59), which cannot be oxidized to a keto group (Fig. 8B). Thus, the microbial transformation of 17-hydroxypregn-4-en-3-one-20-carboxyl-CoA to androst-4-en-3,17-dione proceeds by a retro-aldol reaction (55). These reactions have also been detected in microorganisms grown under anoxic conditions (56). One may envisage that S. denitrificans removes the C2 side chain at C-5 of 2,3-SAOA via similar reactions to yield 17-hydroxy-2,5-seco-3,4-dinorandrost-1,5-dione (2,5-SDAD) and acetyl-CoA (Fig. 8A).

FIG 8.

(A) Proposed pathway of anoxic testosterone degradation by the denitrifying bacteria. Note that the 6-hydroxysteroid is produced by S. denitrificans DSMZ 13999 only when 3-mercaptopropionate is present. ∗, intermediates detected in S. denitrificans cultures (this study). †, intermediates detected in Sdo. denitrificans DSMZ 18526 (39, 41). (B) The established retro-aldol reaction involved in the 9,10-seco pathway for the oxic cholesterol catabolism (56).

In the presence of 3-mercaptopropionate, anaerobically grown S. denitrificans produced and accumulated 2,3-SAOA and 6α-hydroxyandrost-4-en-3,17-dione. However, the C17 intermediate was not detected. It seems that this 6α-hydroxysteroid is a by-product accumulating when the native catabolic flow via reactions similar to β-oxidation is hindered. The data suggest that in the normal catabolic steps, the A-ring cleavage might be followed by the B-ring activation via a 6-hydroxylation. The anaerobic hydroxylation occurring at the steroidal B ring was never reported before, although it is known that anaerobic microbial transformation of bile acids involves 7α-dehydroxylation (60). The mechanism of the anaerobic 6α-hydroxylation remains to be unraveled. It might be catalyzed by an enzyme similar to steroid C25 dehydrogenase via a direct hydroxylation (61) or by a protein similar to 2-cyclohexenone hydratase protein through the addition of water to a C=C bond (62). It is worth mentioning that the latter enzyme is bifunctional and also responsible for the subsequent dehydrogenation reaction. The corresponding substrate containing the C=C bond and the 6-keto product were never detected in S. denitrificans cultures. It is therefore likely that 6α-hydroxyandrost-4-en-3,17-dione is produced from androst-4-en-3,17-dione by an anaerobic hydroxylation. Furthermore, at least seven proteins with high similarity to the molybdenum-containing subunit of steroid C25 dehydrogenase were identified in the S. denitrificans genome (61). The anaerobic 6α-hydroxylation could be catalyzed by one of these molybdoproteins.

In this work, the androgenic activity of the intermediates involved in the 2,3-seco pathway was investigated for the first time. Our results revealed that only 2,3-SAOA (≤500 μM), the ring cleavage intermediate, exhibited no androgenic activity. In addition, we showed that during the denitrifying growth of S. denitrificans, the biotransformation of testosterone to 2,3-SAOA was accompanied by an apparent decrease of its androgenic activity. It is known that numerous bacteria can transform testosterone to other androgens (32). Our results (Fig. 6) indicated that the biotransformation of testosterone to other steroids (e.g., ADD) may reduce its androgenic activity, but the cleavage of the sterane structure can drastically reduce the androgenic activity of testosterone.

It has been proposed that proteobacteria play a crucial environmental role in the aerobic degradation of androgens (29), and all studied androgen-degrading aerobes utilized the 9,10-seco pathway to degrade androgens (28). In this study, we observed the production of 2,3-SAOA by S. denitrificans regardless of oxygen conditions. The data indicate that this oxygen-independent testosterone catabolic pathway operates under not only anoxic but also oxic conditions.

One of the major challenges in environmental microbiology is to detect the function of microorganisms in situ and, if possible, to identify the pathways employed for the degradation of environmentally relevant compounds. In general, signature intermediates of degradation pathways have to be highly specific for key reactions of the respective catabolic pathways (63). Therefore, the common intermediates, including DT, AD, and ADD, are not suitable to serve as signature intermediates. On the other hand, 1-oxygenated steroids are highly characteristic in the 2,3-seco pathway but they were accumulated only in in vitro enzyme assays (47), suggesting the inappropriateness of using these intermediates as signature intermediates for in situ environmental studies. In the case of microbial androgen degradation, we suggest the use of ring cleavage products [2,3-SAOA for the 2,3-seco pathway and 3,17-dihydroxy-9,10-seco-androsta-1,3,5(10)-triene-9-one for the 9,10-seco pathway] as the signature intermediates because (i) the two ring cleavage intermediates are highly specific for the respective catabolic pathways, (ii) the two ring cleavage intermediates possess distinguishable molecular mass, UPLC/HPLC, and UV absorption behaviors which facilitate HPLC-UV or UPLC-MS identification, (iii) the two ring cleavage intermediates are often abundant in testosterone-grown bacterial cultures, and (iv) the ring cleavage intermediates exhibit no androgenic activity. So far, information about the functional genes involved in the 2,3-seco pathway is lacking. The in situ detection of these ring cleavage metabolites could be a powerful tool enabling detection of microbial androgen degradation in the natural environment and engineered systems.

Conclusions.

The 2,3-seco pathway is used in all studied cases for anaerobic catabolism of C19 androgens. In addition, some evidence indicates that this pathway also functions under microaerobic and aerobic conditions. Our current study paves the way for the elucidation of the downstream steps in anoxic androgen biodegradation. Furthermore, this work provides the groundwork for culture-independent in situ studies of microbial degradation of androgens by signature metabolite profiling.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC 100-2311-B-001-032-MY3). We acknowledge the support of the CAS/SAFEA International Partnership Program for Creative Research Teams (KZCX2-YW-T08).

We thank the Small Molecule Metabolomics core facility sponsored by the Institute of Plant and Microbial Biology (IPMB), Academia Sinica, for UPLC-MS analysis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 March 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03880-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jobling S, Nolan M, Tyler CR, Brighty G, Sumpter JP. 1998. Widespread sexual disruption in wild fish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32:2498–2506. 10.1021/es9710870 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miles-Richardson SR, Kramer VJ, Fitzgerald SD, Render JA, Yamini B, Barbee SJ, Giesy JP. 1999. Effects of waterborne exposure of 17 β-estradiol on secondary sex characteristics and gonads of fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas). Aquat. Toxicol. 47:129–145. 10.1016/S0166-445X(99)00009-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panter GH, Thompson RS, Sumpter JP. 1998. Adverse reproductive effects in male fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) exposed to environmentally relevant concentrations of the natural oestrogens, oestradiol and oestrone. Aquat. Toxicol. 42:243–253. 10.1016/S0166-445X(98)00038-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Routledge EJ, Sheahan D, Desbrow C, Brighty GC, Waldock M, Sumpter JP. 1998. Identification of estrogenic chemicals in STW effluent. 2. In vivo responses in trout and roach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32:1559–1565 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teles M, Gravato C, Pacheco M, Santos MA. 2004. Juvenile sea bass biotransformation, genotoxic and endocrine responses to beta-naphthoflavone, 4-nonylphenol and 17 beta-estradiol individual and combined exposures. Chemosphere 57:147–158. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams RJ, Johnson AC, Smith JJ, Kanda R. 2003. Steroid estrogens profiles along river stretches arising from sewage treatment works discharges. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37:1744–1750. 10.1021/es0202107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daughton CG. 2008. Pharmaceuticals as environmental pollutants: the ramifications for human exposure. Int. Encyclopedia Public Health 5:66–102. 10.1016/B978-012373960-5.00403-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folmar LC, Denslow ND, Rao V, Chow M, Crain DA, Enblom J, Marcino J, Guillette LJ. 1996. Vitellogenin induction and reduced serum testosterone concentrations in feral male carp (Cyprinus carpio) captured near a major metropolitan sewage treatment plant. Environ. Health Perspect. 104:1096–1101. 10.1289/ehp.961041096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson DGJ, Hällman H, Förlin L. 2000. More male fish embryos near a pulp mill. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 19:2911–2917. 10.1002/etc.5620191210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlando EF, Kolok AS, Binzcik GA, Gates JL, Horton MK, Lambright CS, Gray LE, Soto AM, Guillette LJ. 2004. Endocrine-disrupting effects of cattle feedlot effluent on an aquatic sentinel species, the fathead minnow. Environ. Health Perspect. 112:353–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parks LG, Lambright CS, Orlando EF, Guillette LJ, Ankley GT, Gray LE. 2001. Masculinization of female mosquitofish in Kraft mill effluent-contaminated Fenholloway River water is associated with androgen receptor agonist activity. Toxicol. Sci. 62:257–267. 10.1093/toxsci/62.2.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen H, Siegrist H, Halling-Sorensen B, Ternes TA. 2003. Fate of estrogens in a municipal sewage treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37:4021–4026. 10.1021/es026192a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shore LS, Shemesh M. 2003. Naturally produced steroid hormones and their release into the environment. Pure Appl. Chem. 75:1859–1871. 10.1351/pac200375111859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Möhle U, Heistermann M, Palme R, Hodges JK. 2002. Characterization of urinary and fecal metabolites of testosterone and their measurement for assessing gonadal endocrine function in male nonhuman primates. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 129:135–145. 10.1016/S0016-6480(02)00525-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanselman TA, Graetz DA, Wilkie AC. 2003. Manure-borne estrogens as potential environmental contaminants: a review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37:5471–5478. 10.1021/es034410+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenzen A, Hendel JG, Conn KL, Bittman S, Kwabiah AB, Lazarovitz G, Masse D, McAllister TA, Topp E. 2004. Survey of hormone activities in municipal biosolids and animal manures. Environ. Toxicol. 19:216–225. 10.1002/tox.20014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kjaer J, Olsen P, Bach K, Barlebo HC, Ingerslev F, Hansen M, Sorensen BH. 2007. Leaching of estrogenic hormones from manure-treated structured soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41:3911–3917. 10.1021/es0627747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baronti C, Curini R, D'Ascenzo G, Di Corcia A, Gentili A, Samperi R. 2000. Monitoring natural and synthetic estrogens at activated sludge sewage treatment plants and in a receiving river water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34:5059–5066. 10.1021/es001359q [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang H, Wan Y, Hu J. 2009. Determination and source apportionment of five classes of steroid hormones in urban rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43:7691–7698. 10.1021/es803653j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang H, Wan Y, Wu S, Fan Z, Hu J. 2011. Occurrence of androgens and progestogens in wastewater treatment plants and receiving river waters: comparison to estrogens. Water Res. 45:732–740. 10.1016/j.watres.2010.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Combalbert S, Hernandez-Raquet G. 2010. Occurrence, fate, and biodegradation of estrogens in sewage and manure. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 86:1671–1692. 10.1007/s00253-010-2547-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan Z, Wu S, Chang H, Hu J. 2011. Behaviors of glucocorticoids, androgens and progestogens in a municipal sewage treatment plant: comparison to estrogens. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45:2725–2733. 10.1021/es103429c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolodziej EP, Gray JL, Sedlak DL. 2003. Quantification of steroid hormones with pheromonal properties in municipal wastewater effluent. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 22:2622–2629. 10.1897/03-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ternes TA, Stumpf M, Mueller J, Haberer K, Wilken RD, Servos M. 1999. Behavior and occurrence of estrogens in municipal sewage treatment plants. I. Investigations in Germany, Canada and Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 225:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson AC, Sumpter JP. 2001. Removal of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in activated sludge treatment works. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35:4697–4703. 10.1021/es010171j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanal SK, Xie B, Thompson ML, Sung S, Ong SK, Van Leeuwent J. 2006. Fate, transport, and biodegradation of natural estrogens in the environment and engineered systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40:6537–6546. 10.1021/es0607739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donova MV. 2007. Transformation of steroids by actinobacteria: a review. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 43:1–14. 10.1134/S0003683807010012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horinouchi M, Hayashi T, Kudo T. 2012. Steroid degradation in Comamonas testosteroni. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 129:4–14. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang YY, Pereyra LP, Young RB, Reardon KF, Borch T. 2011. Testosterone-mineralizing culture enriched from swine manure: characterization of degradation pathways and microbial community composition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45:6879–6886. 10.1021/es2013648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coulter AW, Talalay P. 1968. Studies on the microbiological degradation of steroid ring A. J. Biol. Chem. 243:3238–3247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harder J, Probian C. 1997. Anaerobic mineralization of cholesterol by a novel type of denitrifying bacterium. Arch. Microbiol. 167:269–274. 10.1007/s002030050442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ismail W, Chiang YR. 2011. Oxic and anoxic metabolism of steroids by bacteria. J. Bioremed. Biodegr. S1:001. 10.4172/2155-6199.S1-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan Z, Casey FX, Hakk H, Larsen GL. 2007. Persistence and fate of 17beta-estradiol and testosterone in agricultural soils. Chemosphere 67:886–895. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan Z, Casey FX, Hakk H, Larsen GL. 2007. Discerning and modeling the fate and transport of testosterone in undisturbed soil. J. Environ. Qual. 36:864–873. 10.2134/jeq2006.0451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobsen AM, Lorenzen A, Chapman R, Topp E. 2005. Persistence of testosterone and 17beta-estradiol in soils receiving swine manure or municipal biosolids. J. Environ. Qual. 34:861–871. 10.2134/jeq2004.0331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandes P, Cruz A, Angelova B, Pinheiro HM, Cabral JMS. 2003. Microbial conversion of steroid compounds: recent developments. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 32:688–705. 10.1016/S0141-0229(03)00029-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin CJ, Mackenzie PI, Miners JO. 1997. The regio- and stereoselectivity of C19 and C21 hydroxysteroid glucuronidation by UGT2B7 and UGT2B11. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 341:207–211. 10.1006/abbi.1997.9949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei W, Wang FQ, Fan SY, Wei DZ. 2010. Inactivation and augmentation of the primary 3-ketosteroid-δ-1-dehydrogenase in Mycobacterium neoaurum NwIB-01: biotransformation of soybean phytosterols to 4-androstene-3,17-dione or 1,4-androstadiene-3,17-dione. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4578–4582. 10.1128/AEM.00448-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang PH, Leu YL, Ismail W, Tang SL, Tsai CY, Chen HJ, Kao AT, Chiang YR. 2013. Anaerobic and aerobic cleavage of the steroid core ring structure by Steroidobacter denitrificans. J. Lipid Res. 54:1493–1504. 10.1194/jlr.M034223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiang YR, Fang JY, Ismail W, Wang PH. 2010. Initial steps in anoxic testosterone degradation by Steroidobacter denitrificans. Microbiology 156:2253–2259. 10.1099/mic.0.037788-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fahrbach M, Krauss M, Preiss A, Kohler HP, Hollender J. 2010. Anaerobic testosterone degradation in Steroidobacter denitrificans—identification of transformation products. Environ. Pollut. 158:2572–2581. 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fahrbach M, Kuever J, Remesch M, Huber BE, Kampfer P, Dott W, Hollender J. 2008. Steroidobacter denitrificans gen. nov., sp. nov., a steroidal hormone-degrading gammaproteobacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58:2215–2223. 10.1099/ijs.0.65342-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiang YR, Ismail W, Heintz D, Schaeffer C, Van Dorsselaer A, Fuchs G. 2008. Study of anoxic and oxic cholesterol metabolism by Sterolibacterium denitrificans. J. Bacteriol. 190:905–914. 10.1128/JB.01525-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiang YR, Ismail W, Muller M, Fuchs G. 2007. Initial steps in the anoxic metabolism of cholesterol by the denitrifying Sterolibacterium denitrificans. J. Biol. Chem. 282:13240–13249. 10.1074/jbc.M610963200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarlera S, Denner EB. 2003. Sterolibacterium denitrificans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel cholesterol-oxidizing, denitrifying member of the beta-Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1085–1091. 10.1099/ijs.0.02039-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang PH, Lee TH, Ismail W, Tsai CY, Lin CW, Tsai YW, Chiang YR. 2013. An oxygenase-independent cholesterol catabolic pathway operates under oxic conditions. PLoS One 8:e66675. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leu YL, Wang PH, Shiao MS, Ismail W, Chiang YR. 2011. A novel testosterone catabolic pathway in bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 193:4447–4455. 10.1128/JB.00331-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roh H, Chu KH. 2010. 17beta-Estradiol-utilizing bacterium, Sphingomonas strain KC8. I. Characterization and abundance in wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44:4943–4950. 10.1021/es1001902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chiang IZ, Huang WY, Wu JT. 2004. Allelochemicals of Botryococcus braunii (Chlorophyceae). J. Phycol. 40:474–480. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2004.03096.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabbagh E, Cuebas D, Schulz H. 1985. 3-Mercaptopropionic acid, a potent inhibitor of fatty acid oxidation in rat heart mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 260:7337–7342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Mohsen AW, Mihalik Goetzman ES, Vockley J. 2010. Evidence for physical association of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 285:29834–29841. 10.1074/jbc.M110.139493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becker DM, Lundblad V. 1993. Manipulation of yeast genes: introduction of DNA into yeast cells, p 13.7.1–13.7.10 In Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. (ed), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fox JE, Burow ME, McLachlan JA, Miller CA., III 2008. Detecting ligands and dissecting nuclear receptor-signaling pathways using recombinant strains of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Protoc. 3:637–645. 10.1038/nprot.2008.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pandey AK, Sassetti CM. 2008. Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:4376–4380. 10.1073/pnas.0711159105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sih CJ, Tai HH, Tsong YY. 1967. The mechanism of microbial conversion of cholesterol into 17-keto steroids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 89:1957–1958. 10.1021/ja00984a039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sih CJ, Wang KC, Tai HH. 1967. C22 acid intermediates in the microbiological cleavage of the cholesterol side chain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 89:1957–1958. 10.1021/ja00984a039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Świzdor A, Panek Milecka-Tronina A, Kołek NT. 2012. Biotransformations utilizing β-oxidation cycle reactions in the synthesis of natural compounds and medicines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13:16514–16543. 10.3390/ijms131216514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nesbitt NM, Yang X, Fontán P, Kolesnikova I, Smith I, Sampson NS, Dubnau E. 2010. A thiolase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for virulence and production of androstenedione and androstadienedione from cholesterol. Infect. Immun. 78:275–282. 10.1128/IAI.00893-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.García JL, Uhía I, Galán B. 2012. Catabolism and biotechnological applications of cholesterol degrading bacteria. Microb. Biotechnol. 5:679–699. 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2012.00331.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB. 2006. Bile salt biotransformation by human intestinal bacteria. J. Lipid Res. 47:241–259. 10.1194/jlr.R500013-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dermer J, Fuchs G. 2012. Molybdoenzyme that catalyzes the anaerobic hydroxylation of a tertiary carbon atom in the side chain of cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 287:36905–36916. 10.1074/jbc.M112.407304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jin J, Straathof AJJ, Pinkse MWH, Hanefeld U. 2011. Purification, characterization, and cloning of a bifunctional molybdoenzyme with hydratase and alcohol dehydrogenase activity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 89:1831–1840. 10.1007/s00253-010-2996-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eberlein C, Johannes J, Mouttaki H, Sadeghi M, Golding BT, Boll Meckenstock MRU. 2013. ATP-dependent/-independent enzymatic ring reductions involved in the anaerobic catabolism of naphthalene. Environ. Microbiol. 15:1832–1841. 10.1111/1462-2920.12076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.