Abstract

Four traditional type I sourdoughs were comparatively propagated (28 days) under firm (dough yield, 160) and liquid (dough yield, 280) conditions to mimic the alternative technology options frequently used for making baked goods. After 28 days of propagation, liquid sourdoughs had the lowest pH and total titratable acidity (TTA), the lowest concentrations of lactic and acetic acids and free amino acids, and the most stable density of presumptive lactic acid bacteria. The cell density of yeasts was the highest in liquid sourdoughs. Liquid sourdoughs showed simplified microbial diversity and harbored a low number of strains, which were persistent. Lactobacillus plantarum dominated firm sourdoughs over time. Leuconostoc lactis and Lactobacillus brevis dominated only some firm sourdoughs, and Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis persisted for some time only in some firm sourdoughs. Leuconostoc citreum persisted in all firm and liquid sourdoughs, and it was the only species detected in liquid sourdoughs at all times; it was flanked by Leuconostoc mesenteroides in some sourdoughs. Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida humilis, Saccharomyces servazzii, Saccharomyces bayanus-Kazachstania sp., and Torulaspora delbrueckii were variously identified in firm and liquid sourdoughs. A total of 197 volatile components were identified through purge and trap–/solid-phase microextraction–gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (PT–/SPME–GC-MS). Aldehydes, several alcohols, and some esters were at the highest levels in liquid sourdoughs. Firm sourdoughs mainly contained ethyl acetate, acetic acid, some sulfur compounds, and terpenes. The use of liquid fermentation would change the main microbial and biochemical features of traditional baked goods, which have been manufactured under firm conditions for a long time.

INTRODUCTION

Sourdough is traditionally used as the leavening agent for bread making. About 30 to 50% of the breads manufactured in European countries require the use of sourdough. In Italy, ca. 200 different types of traditional/typical sourdough breads are manufactured, especially by small or medium-size specialized bakeries (1, 2). During the last 2 decades, a very abundant literature has dealt with sourdough: 818 published items were retrieved from the main literature databases in November 2013. At present, the use of sourdough has been extended to making crackers, pizza, various sweet baked goods, and gluten-free products (3, 4). Most studies have demonstrated that sourdough positively influences the sensory, nutritional, texture, and shelf-life features of baked goods (3, 5). A microbial consortium, mainly consisting of obligately and/or facultatively heterofermentative lactobacilli and yeasts, dominates mature sourdough (6). The microbial ecology dynamics during rye and wheat sourdough preparation was recently described through a high-throughput sequencing approach targeting DNA and RNA (7). Operational taxonomic unit network analysis provided an immediate interpretation of the dynamics. As soon as the fermentation was started by adding water to the flour, the microbial complexity rapidly simplified, and rye and wheat sourdoughs became dominated by a core microbiota consisting mainly of lactic acid bacteria (7).

The diversity and stability of the sourdough microbiota depend on a number of ecological determinants, which include technological (e.g., dough yield [DY], the percentage of sourdough used as an inoculum, salt, pH, redox potential, leavening temperature, the use of baker's yeast, the number and length of sourdough refreshments, and the chemical and enzyme composition of the flour) (3, 8–12) and not fully controllable (e.g., flour and other ingredients and house microbiota [the microorganisms contaminating the bakery setting and equipment]) parameters (12). Furthermore, the metabolic adaptability to stressing sourdough conditions, the nutritional interactions among microorganisms, and the intrinsic robustness or weakness of microorganisms all influence the stability of the mature sourdough (12). Given these numerous factors, the diverse taxonomy and metabolism that characterize sourdough yeasts and, especially, lactic acid bacteria are not surprising (13, 14).

Among the technological parameters, the dough yield (DY = [flour weight + water weight] × 100/flour weight) markedly influences the progress and outcome of sourdough fermentation, due to the effect on microbial diversity (12, 15). Since flours have different capacities to absorb water, DY mainly deals with dough consistency and measures the amount of water used in the dough formula. The greater the amount of water, the higher the value of DY, which has an influence on the acidity of the sourdough (15) and, slightly, on the values of water activity (15, 16). Type I, or traditional, sourdough is usually made from firm dough, with DY values of ca. 150 to 160. Management (fermentation, refreshment/backslopping [the inoculation of flour and water with an aliquot of previously fermented dough], and storage) of type I sourdough on an industrial scale is considered somewhat time-consuming, requires qualified staff, and interferes with microbial stability and optimum performance during bread making. To overcome such limitations, liquid-sourdough fermentation was more or less recently introduced as another technology option for bakeries that used traditional type I sourdough (17–20). Therefore, a large number of bakeries, especially in Italy, switched from firm- to liquid-sourdough fermentation, aiming, however, at manufacturing the same traditional/typical bread. In view of this technology change, some issues need to be addressed. How are the diversity and stability of the microbiota influenced during the switch from firm to liquid sourdough and, consequently, does the liquid-sourdough fermentation produce the same biochemical and sensory features as firm conditions? Furthermore, a very few studies (21, 22) have considered the effect of DY on the diversity of the sourdough microbiota, and none used the approach of this study and provided in-depth microbial and biochemical characterization.

This study considered four firm and mature type I sourdoughs, which were propagated daily for 28 days under firm and liquid conditions to mimic the technology changes that likely occur on an industrial scale. The diversity of the lactic acid bacteria and yeast microbiota was monitored through culture-independent and -dependent methods, and the biochemical features and the profile of volatile components (VOC) were determined. Multivariate statistical analysis was used to find correlations between the composition of the sourdough microbiota, the biochemical characteristics, the volatile components, and firm or liquid sourdoughs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sourdoughs.

Sourdoughs from four artisan bakeries, which are located in southern Italy, were considered in the study. The acronyms used were as follows: MA, MB, MC (Matera, Basilicata region) and A (Altamura, Apulia region). On a bakery scale, sourdoughs were made and propagated through traditional protocols (sourdough type I), without the use of starter cultures or baker's yeast. Preliminarily, sourdoughs were propagated daily at the laboratory level for 7 days under the conditions used by artisan bakeries. This stabilized the effect of the laboratory environment on the composition of the sourdough microbiota (23). Table 1 describes the ingredients and technology parameters used for daily backslopping of sourdoughs, which lasted 28 days. Liquid propagation was carried out with stirring (150 rpm). Between the daily fermentations, the sourdoughs were left at 10°C for 16 to 19 h. This corresponds to the most common practice at the artisanal level, which avoids disturbance of microbial performance (e.g., leavening activity) by the refrigeration temperature and allows slight microbial growth. Throughout the process, three batches of each sourdough were collected (every 7 days) at the end of fermentation. The numbers I, II, III, IV, and V identify sourdoughs after 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days of backslopping. The sourdoughs were cooled to 4°C and analyzed within 2 h after collection. All the analyses were carried out in duplicate for each batch of sourdough (a total of six analyses for each type of sourdough).

TABLE 1.

Ingredients and technology parameters used for daily sourdough backslopping

| Sourdougha | Typeb | Flour (g)c,d | Sourdough (g)d | Water (g)d | % of sourdough in the refreshment | DY | Backslopping timee (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | F | 585.9 | 62.5 | 351.6 | 6.25 | 160 | 5 |

| L | 334.8 | 62.5 | 602.7 | 6.25 | 280 | 5 | |

| MB | F | 437.5 | 300 | 262.5 | 30 | 160 | 4 |

| L | 250.0 | 300 | 450.0 | 30 | 280 | 4 | |

| MC | F | 437.5 | 300 | 262.5 | 30 | 160 | 3 |

| L | 250.0 | 300 | 450.0 | 30 | 280 | 3 | |

| A | F | 556.9 | 109 | 334.1 | 10.9 | 160 | 6 |

| L | 318.2 | 109 | 572.8 | 10.9 | 280 | 6 |

Sourdoughs are identified with the names of the bakeries. Only one step of propagation (daily backslopping) was traditionally used.

F, firm sourdough (DY = 160); L, liquid sourdough (DY = 280).

Triticum durum.

The amount of each ingredient refers to 1 kg of dough.

Time indicates the length of backslopping (h) at an incubation temperature of 25°C.

Determinations of pH, TTA, organic acids, and FAA.

The pH values were determined with a pH meter. Total titratable acidity (TTA) was measured on 10-g dough samples, which were homogenized with 90 ml of distilled water for 3 min in a Bag Mixer 400P (Interscience, St Nom, France), and is expressed as the amount (in ml) of 0.1 N NaOH to achieve pH 8.3. Lactic and acetic acids were determined in the water-soluble extract of the sourdough. Ten grams of sourdough was homogenized with 90 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.8. After incubation (30 min at 25°C with stirring), the suspension was centrifuged (12,857 × g; 10 min; 4°C), and the supernatant was analyzed using an Äkta Purifier system (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden) equipped with a refractive index detector (PerkinElmer Corp., Waltham, MA). The fermentation quotient (FQ) was defined as the molar ratio between lactic and acetic acids. The concentration of free amino acids (FAA) of the water-soluble extract was determined using the Biochrom 30 Amino Acid Analyser (Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge Science Park, Cambridge, England). A mixture of amino acids at known concentration (Sigma Chemical Co., Milan, Italy) was added, along with cysteic acid, methionine sulfoxide, methionine sulfone, tryptophan, and ornithine, and used as the external standard (24).

PCR amplification and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analysis.

Ninety milliliters of 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, buffer was added to 10 g of sourdough and homogenized for 5 min, and the DNA extraction was carried out as described by Minervini et al. (25). Bacterial DNA was amplified with primers Lac1 (5′-AGCAGTAGGGAATCTTCCA-3′) and Lac2 (5′-ATTYCACCGCTACACATG-3′), targeting a 340-bp region of the 16S rRNA genes of the Lactobacillus group, including the genera Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, and Weissella (26). DNA from acetic acid bacteria was amplified with primers WBAC1 (5′-GTCGTCAGCTCGTGTCGTGAGA-3′) and WBAC2 (5′-CCCGGGAACGTATTCACCGCG-3′) targeting the V7-V8 regions of the 16S rRNA genes, which produced amplicons of approximately 330 bp (27). Normalization of the gels was performed using reference ladders of DNA from pure cultures of Acetobacter malorum DSM 14337 and Gluconobacter oxydans DSM 7145 mixed in equal volumes of the same concentration.

DNA from yeasts was amplified with primers NL1 (5′-GCCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG-3′) and LS2 (5′-ATTCCCAAACAACTCGACTC-3′), corresponding to the D1-D2 region of the 26S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (28). The PCR core program was carried out as described previously (26–28).

Amplicons were separated by DGGE using the Bio-Rad DCode Universal Mutation detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Milan, Italy). Sybr green I-stained gels were photographed through the Gel Doc 2000 documentation system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Profiles were digitally normalized through comparison with the standard reference (MassRuler Low Range DNA Ladder, ready-to-use; 80 to 1,031 bp; Fermentas Molecular Biology Tools, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) and BioNumerics software, version 2.50 (Applied Maths, St. Martens-Latem, Belgium). The DGGE bands of yeasts were cut out and eluted in 50 μl of sterile water overnight at 4°C. Two microliters of the eluted DNA was reamplified, and the PCR products were separated as described above. The amplicons were eluted from the gel and purified with the GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (GE Healthcare). DNA-sequencing reactions were carried out by MWG Biotech AG (Ebersberg, Germany). Sequences were compared using the GenBank database and the BLAST program (29).

Enumeration and isolation of lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria and yeasts.

Ten grams of sourdough was homogenized with 90 ml of sterile peptone water (1% [wt/vol] peptone and 0.9% [wt/vol] NaCl) solution. Lactic acid bacteria were counted using sourdough bacteria (SDB) agar medium supplemented with cycloheximide (0.1 g liter−1). The plates were incubated under anaerobiosis (AnaeroGen and AnaeroJar; Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom) at 30°C for 48 h. At least 10 colonies of presumptive lactic acid bacteria were randomly selected from the plates containing the two highest sample dilutions. Gram-positive, catalase-negative, nonmotile rod and coccus isolates were cultivated in SDB broth at 30°C for 24 h and restreaked onto the same agar medium. All isolates considered for further analysis were able to acidify the culture medium. Acetic acid bacteria were counted on deoxycholate sorbitol mannitol (DSM) medium (30) supplemented with cycloheximide (0.1 g liter−1). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 to 4 days under aerobic conditions. At least five colonies of presumptive acetic acid bacteria were randomly selected from the plates containing the two highest sample dilutions. Gram-negative, aerobic, rod-shaped bacteria were cultivated in DSM broth at 37°C for 2 to 4 days and restreaked onto the same agar medium. Stock cultures were stored at −20°C in 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. The number of yeasts was estimated on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) (Oxoid) medium supplemented with chloramphenicol (0.1 g liter−1) at 30°C for 48 h. Five randomly selected colonies of yeasts from the highest plate dilutions were subcultured in SDA and restreaked onto the same agar media.

Genotypic characterization by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)-PCR analysis.

Genomic DNA of lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria was extracted according to the method of De Los Reyes-Gavilán et al. (31). Three oligonucleotides, P4 (5′-CCGCAGCGTT-3′), P7 (5′-AGCAGCGTGG-3′) (32), and M13 (5′-GAGGGTGGCGGTTCT-3′) (33), with arbitrarily chosen sequences were used for biotyping of lactic acid and acetic acid bacterial isolates. The reaction mixture and PCR conditions for primers P4 and P7 were those described by Corsetti et al. (32), whereas those reported by Zapparoli et al. (34) were used for primer M13.

Genomic DNA of yeast was extracted using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two oligonucleotides, M13m (5′-GAGGGTGGCGGTTC-3′) and Rp 11 (5′-GAAACTCGCCAAG-3′) (35), were used singly in two series of amplifications for biotyping of yeast isolates. RAPD-PCR profiles were acquired by the Gel Doc 2000 Documentation System and compared using Fingerprinting II Informatix software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). We evaluated the similarity of the electrophoretic profiles by determining the Dice coefficients of similarity and using the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) algorithm. Since RAPD profiles of the isolates from one batch of each type of sourdough were confirmed by analyzing isolates from two other batches, strains isolated from a single batch were further analyzed.

Genotypic identification of lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria and yeasts.

To identify presumptive lactic acid bacterial strains, two primer pairs, LacbF/LacbR and LpCoF/LpCoR (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Milan, Italy), were used for amplifying the 16S rRNA genes (36). Primers designed for the recA gene were also used to distinguish Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus pentosus, and Lactobacillus paraplantarum species (37). Primers designed for the pheS gene were used for identifications to the species level within the genera Leuconostoc and Weissella (38). Sequencing analysis for acetic acid bacteria was carried out using primers 5′-CGTGTCGTGAGATGTTGG-3′ (positions 1071 to 1087 on 16S rRNA genes; Escherichia coli numbering) and 5′-CGGGGTGCTTTTCACCTTTCC-3′ (positions 488 to 468 on 23S rRNA genes; E. coli numbering), according to the procedure described by Trčekl and Teuber (39). To identify presumptive yeasts, two primers, NL-1 (5′-GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG-3′) and NL-4 (5′-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG-3′), were used for amplifying the divergent D1-D2 domain of the 26S rDNA (40). Electrophoresis was carried out on an agarose gel at 1.5% (wt/vol) (Gellyphor; EuroClone), and amplicons were purified with GFX PCR DNA and a Gel Band Purification Kit (GE Healthcare). Sequencing electrophoregram data were processed with Geneious. rRNA sequence alignments were carried out using the multiple-sequence alignment method (41), and identification queries were fulfilled by a BLAST search (29) in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/).

Determinations of VOC and VFFA.

VOC were extracted through purge and trap coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (PT–GC-MS) according to the method of Di Cagno et al. (42). Volatile free fatty acids (VFFA) were extracted by solid-phase microextraction coupled with GC-MS (SPME–GC-MS). Prior to PT and SPME analyses, a suspension of 10% (wt/wol) sourdough in UHQ water deodorized by boiling for 15 min was homogenized with Ultra-Turrax (IKA Staufen, Germany). For extraction of VOC, 10 ml of this suspension was poured into a glass extractor connected to the PT apparatus (Tekmar LSC 3000; Agilent Technologies, Les Ulis, France). Extraction was carried out at 45°C for 45 min with helium at a flow rate of 40 ml/min on a Tenax trap (Agilent Technologies) at 37°C. Trap desorption was at 225°C, and injection into the chromatograph was performed directly into the column with a cryo-cooldown injector at −150°C. The chromatograph (6890; Agilent Technologies) was equipped with a DB5-like (apolar) capillary column (RTX5; Restek, Lisses, France; 60-m length, 0.32-μm inside diameter [i.d.], and 1-μm thickness). The helium flow rate was 2 ml/min; the oven temperature was 40°C during the first 6 min, and then it was increased at 3°C/min to 230°C. The mass detector (MSD5973; Agilent Technologies) was used in electronic impact at 70 eV in scan mode from 29 to 206 atomic mass. Identification of volatile compounds was done by comparison of experimental mass spectra with spectra of the NIST/EPA/MSDC Mass Spectral Database (Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Semiquantification was done by integration of one ion characteristic of each compound, allowing comparison of the area of each eluted compound between samples. Measurements are given in arbitrary area units of characteristic ions. Analyses were duplicated. For SPME extraction of VFFA, each sample was analyzed three times at three different dilutions; 200 μl, 400 μl, or 1 ml of the 10% suspension of sourdough was poured into a 10-ml flask with 100 μl of 2 N sulfuric acid and 900, 700, or 100 μl, respectively, of UHQ water. The flask was sealed and placed into a bath at 60°C for 15 min. An SPME carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane 75-μm fiber (black plain hub; Supelco, Sigma Chemical Co., L'isle d'Abeau, France) was introduced into the flask and held in the headspace for 30 min at 60°C. Then, it was removed and desorbed for 5 min in a splitless chromatograph injector at 240°C. The chromatograph (6890; Agilent Technologies) was equipped with a Carbowax-like capillary column (Stabilwax DA; Restek, Lisses, France; 30-m length, 0.32-μm i.d., and 0.5-μm thickness). The helium flow rate was 2 ml/min; the oven temperature was 120°C during the first minute, and then it was increased at 1.8°C/min to 240°C. The mass detector (MSD5973; Agilent Technologies) was used as described above. Concentrations of VFFA were calculated from calibration curves established with external standards of acetic, propionic, butyric, pentanoic, hexanoic, heptanoic, octanoic, 2-methyl-propionic, 3-methyl-butyric, and 2-methyl-butyric acids (Sigma) and expressed in ppm.

Statistical analyses.

Data on pH, TTA, organic acids, FAA, FQ, and cell density of presumptive lactic acid bacteria, yeasts, and acetic acid bacteria were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and pair comparison of treatment means was achieved by Tukey's procedure at a P value of <0.05, using the statistical software Statistica 7.0 for Windows. Data on pH, TTA, organic acids, FQ, FAA, and cell density of lactic acid bacteria were subjected to permutation analysis using PermutMatrix (43). Cluster analysis of RAPD profiles was carried out using Pearson's correlation coefficient, and only profiles that differed by more than 15% are shown. For each sourdough (after 1 and 28 days of backslopping), culture-independent (DGGE bands of lactic acid bacteria), culture-dependent (numbers of species and strains, cell density of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts, and percentages of obligately and facultatively heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria), and biochemical-characteristic (pH, TTA, organic acids, FAA, and FQ) data were used as variables for principal-component analysis (PCA). All data were standardized before PCA using the statistical software Statistica for Windows. Volatile components that mainly (P < 0.05) differentiated sourdoughs (after 1 and 28 days of backslopping) were also subjected to PCA.

RESULTS

Technological, biochemical, and microbiological characteristics.

All sourdoughs used in this study were handled at artisan bakeries that had been manufacturing leavened baked goods (mainly bread) for at least 2 years. As is usual in southern Italy, all sourdoughs were made with Triticum durum flour (Table 1). The percentages of sourdough used for backslopping varied from ca. 6.0% (MA) and 11% (A) to 30% (MB and MC). The preliminary daily sourdough propagation at laboratory level (7 days) did not show modification of the sourdough microbiota compared to profiles, which were found after collecting samples from artisan bakeries (data not shown). Further, sourdoughs were propagated under firm (DY = 160) and liquid (DY = 280) conditions. The times of fermentation ranged between 3 and 6 h, and the temperature was 25°C. Overall, the time of fermentation for sourdoughs was that traditionally used by artisan bakeries, and in part, it reflected the percentage of sourdough used during refreshment.

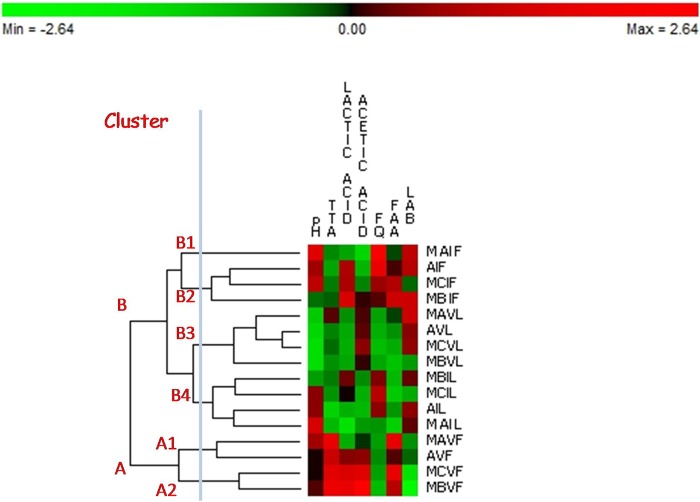

The pH, TTA, organic acids, FQ, FAA, and cell density of presumptive lactic acid bacteria were determined over time (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Figure 1 shows the permutation analysis based on the above characteristics after 1 (I) and 28 (V) days of backslopping. The sourdoughs were distributed in two major clusters (A and B). Apart from the type, cluster A grouped firm sourdoughs after 28 days of propagation. They had pH values that ranged from 4.29 to 4.33, the highest TTA (11 to 13 ml 0.1 N NaOH/10 g of dough), almost the highest concentrations of lactic and acetic acids (30 to 56 mmol kg−1 and 19 to 45 mmol kg−1, respectively) and FAA (525 to 796 mg kg−1), and the lowest number of presumptive lactic acid bacteria (6.59 to 7.72 log CFU g−1). Cluster B grouped firm (I) and liquid (I and V) sourdoughs. Within cluster B, subclusters B1 and B2 included firm sourdoughs after 1 day of propagation, with pH values ranging from 4.27 to 4.38, which corresponded to TTA of 5.7 to 7.1 ml 0.1 N NaOH/10 g of dough. The concentrations of lactic and acetic acids and FAA were 31 to 53 mmol kg−1, 6 to 20 mmol kg−1, and 467 to 643 mg kg−1, respectively. The number of presumptive lactic acid bacteria was almost the highest (7.71 to 8.56 log CFU g−1). Unlike firm sourdoughs, which were scattered in two major clusters (A and B), liquid sourdoughs after 1 and 28 days of propagation were grouped in the same cluster, B, and were separated into subclusters B3 and B4, respectively. The concentrations of FAA (280 to 389 mg kg−1) and lactic and acetic acids (22 to 42 and 10 to 14 mmol kg−1, respectively) already differentiated liquid from firm sourdoughs after 1 day of propagation. Comparing liquid sourdoughs after 1 and 28 days of propagation, the latter showed lower pH values (4.20 to 4.22) and an increased concentration of acetic acid (range, 30 to 54%), even though the number of presumptive lactic acid bacteria remained almost constant (7.51 to 8.56 log CFU g−1). The numbers of yeasts in MAVL, MCVL, and AVL (6.5 ± 0.1, 7.2 ± 0.2, and 7.2 ± 0.1 log CFU g−1, respectively) were ca. 2 log cycles higher (P < 0.05) than those found in the corresponding firm sourdoughs. Similar values (ca. 6.2 log CFU g−1) were found for firm and liquid MB sourdoughs. Compared to lactic acid bacteria and yeasts, the number of acetic acid bacteria was scarcely relevant. Except for MCVL, which contained a number of acetic acid bacteria (3.0 ± 0.5 log CFU g−1) significantly (P < 0.05) higher than that found in the corresponding firm sourdough (1.0 ± 0.2 log CFU g−1), the other firm and liquid sourdoughs did not show significant (P < 0.05) differences (1.0 to 3.0 log CFU g−1).

FIG 1.

pH, TTA (milliliters of 0.1 N NaOH/10 g of dough), lactic and acetic acids (mM), FQ, FAA (mg kg−1), and cell density (log CFU g−1) of presumptive lactic acid bacteria (LAB) of the four sourdoughs (MA, MB, MC, and A) propagated daily under firm (F) and liquid (L) conditions for 1 (I) and 28 (V) days. The ingredients and technological parameters used for daily sourdough backslopping are reported in Table 1. Euclidean distance and McQuitty's criterion (weighted pair group method with averages) were used for clustering. The colors correspond to normalized mean data levels from low (green) to high (red). The color scale, in terms of units of standard deviation, is shown at the top.

DGGE analyses.

No differences were found in the numbers and sizes of amplicons of the Lactobacillus group, either between sourdoughs propagated under firm and liquid conditions or during backslopping (see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material). This finding did not reflect the results of the culture-dependent approach. Primers NL1-GC/LS1, targeting the region of the 26S rRNA gene of yeasts, were also used (see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material). Sequencing of the main bands revealed the presence of Triticum sp. (100% identity; DNA band a), while band b remained unknown. The other DNA corresponded to Saccharomyces cerevisiae (99%) (band c), Saccharomyces bayanus-Kazachstania sp. (99%) (band d), Kazachstania sp.-Kazachstania unispora (99%) (band e), and Candida humilis-Kazachstania barnettii (100%) (band f). Although PCR-DGGE analysis was successful for acetic acid bacteria used as reference strains, no DNA amplicons were found with primers WBAC1/C2.

Typing and identification of lactic acid bacteria.

Gram-positive, catalase-negative, nonmotile cocci and rods able to acidify SDB broth (400 isolates) were subjected to RAPD-PCR analysis (Table 2). The reproducibility of RAPD fingerprints was assessed by comparing the PCR products obtained with primers P7, P4, and M13 and DNA extracted from three separate cultures of the same strain. For this purpose, 10 strains were studied, and patterns for the same strain were similar at a level of ca. 90% (data not shown), as estimated by UPGMA. As shown by cluster analysis of RAPD profiles using UPGMA, the diversity between isolates of the four sourdoughs ranged from ca. 2.5 to 35% (see Fig. S3A to D in the supplemental material). Strains showing RAPD profiles with a maximum level of diversity of 15% were grouped into the same cluster (15, 9, 11, and 15 clusters were found for MA, MB, MC, and A, respectively). Although some clusters grouped isolates from sourdoughs that were backslopped under the same conditions, the majority of them clustered regardless of firm or liquid propagation. The sourdoughs harbored the following species: Leuconostoc citreum (26 strains), L. plantarum (10), Leuconostoc mesenteroides (7), Leuconostoc lactis (4), Weissella cibaria (3), Lactoccocus lactis (3), Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis (3), Lactobacillus brevis (3), and Lactobacillus sakei (1).

TABLE 2.

Species of bacteria identified from the four sourdoughs propagated under firm and liquid conditions for various times

| Sourdough | Closest relative (% identity)a/no. of strains | No. of clustersb | Conditions and times of backsloppingc | Accession no. (no. of clusters) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | L. plantarum (100)/2 | 1, 2 | F I, II, III, IV, V; L I | gb|JN851804.1 (1, 2) |

| L. citreum (99–100)/5 | 3, 5, 6, 9, 10 | F I, II, III, IV, V; L I, II, III, IV, V | ref|NR_074694.1 (3, 5), gb|JN851752.1 (6), gb|JN851747.1 (9, 10) | |

| Leuconostoc lactis (100)/3 | 4, 7, 15 | F II, III, IV, V; L III | gb|KC545927.1 (4, 15), gb|KC836716.1 (7) | |

| Lactococcus lactis (100)/1 | 14 | F III | gb|KC692209.1 (14) | |

| L. mesenteroides (99–100)/2 | 8, 13 | F I, II, III, IV; L I, II, III, IV | gb|KC292492.1 (8), gb|JN863609.1 (13) | |

| W. cibaria (99–100)/2 | 11, 12 | F I; L I | gb|JN851745.1 (11, 12) | |

| MB | L. plantarum (100)/2 | 1, NC | F III, IV, V; L III | gb|JN851804.1 (1), gb|JN851776.1 (NC) |

| L. citreum (99–100)/6 | 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 | F I, II, III, IV, V; L I, II, III, IV, V | gb|KC836690.1 (2), HM058995.1 (4), gb|JN851747.1 (5, 7, 8), gb|JN851752.1 (6) | |

| L. sanfranciscensis (100)/1 | 3 | F I, II, III; L I | gb|JN851759.1 (3) | |

| L. sakei (99)/1 | NC | F III | gb|KF193896.1 (NC) | |

| L. brevis (99)/1 | NC | F III | gb|JN863602.1 (NC) | |

| L. mesenteroides (99)/1 | 9 | F IV; L III | gb|KF148692.1 (9) | |

| Lactococcus lactis (99)/1 | NC | F III | gb|CP004884.1 (NC) | |

| MC | L. plantarum (99–100)/3 | 1, 10, 11 | F I, II, III, IV, V; L I, II, III, IV, V | gb|JN851775.1 (1), gb|JN851804.1 (10), gb|JN851803.1 (11) |

| L. citreum (99–100)/5 | 2, 3, 5, 6, NC | F I, II, III, IV, V; L I, II, III, IV, V | gb|KC836690.1 (2, 5, NC), gb|JN851753.1 (3) ref|NR_074694.1 (6) | |

| L. brevis (100)/2 | 4, 9 | F I, II, III, IV, V; L I, II, III | gb|JN863602.1 (4, 9) | |

| L. mesenteroides (100)/2 | 7, 8 | F I, II, III, IV; L I, II, III, IV, V | gb|KC542404.1 (7), gb|JN863609.1 (8) | |

| W. cibaria (100)/1 | NC | L I | gb|JN851745.1 (NC) | |

| A | L. plantarum (99)/3 | 1, 2, 9 | F I, II, III, IV, V; L I, II | gb|GU138593.1 (1, 2), gb|JN851803.1 (9) |

| L. citreum (99–100)/10 | 3, 4, 6, 11, 12, 14, 15, NC (3) | F I, II, III, IV, V; L I, II, III, IV, V | gb|KF149766.1 (3, 12, 4, 15, NC) gb|KC836690.1 (6, 11, NC) gb|JN851753.1 (4), gb|KF150181.1 (NC) | |

| L. sanfranciscensis (99–100)/2 | 5, 7 | F I, II, III, IV; L I | gb|JN851754.1 (5, 7) | |

| Leuconostoc lactis (99)/1 | 8 | L V | gb|KF193923.1 (8) | |

| L. mesenteroides (100)/2 | 10, 13 | L I, II, III, IV | gb|JN863609.1 (10, 13) |

Species showing the highest identity to the strain isolated from sourdough. The percent identity was found by performing multiple-sequence alignments in BLAST. Identification was carried out by 16S rRNA, recA, or pheS gene sequencing.

Numbers of RAPD-PCR clusters. NC, not clustered.

The ingredients and technological parameters used for daily sourdough backslopping are reported in Table 1. Times were as follows: 1 (I), 7 (II), 14 (III), 21 (IV), and 28 (V) days.

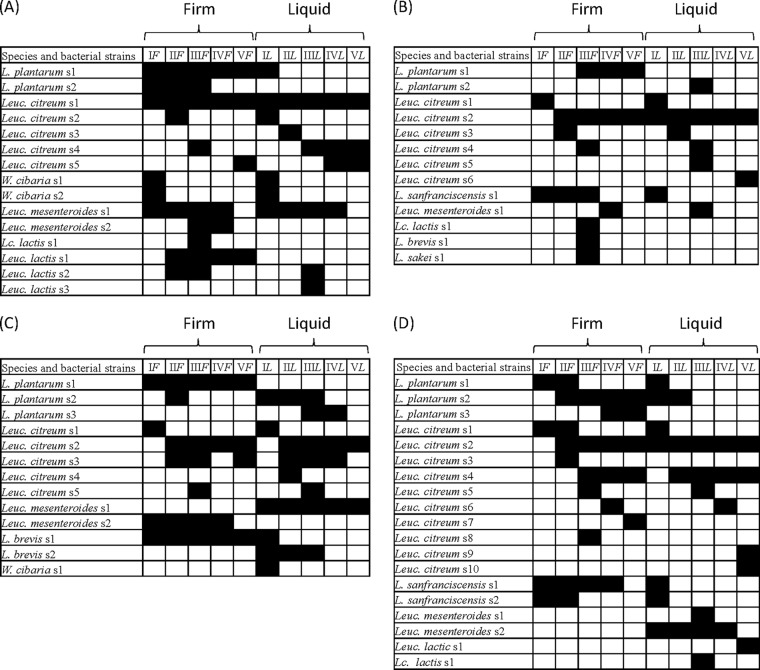

Strains belonging to the same species but isolated from different sourdoughs (firm and liquid) showed different RAPD-PCR profiles. As expected, the microbiota compositions of firm and liquid sourdoughs were similar after 1 day of propagation. Later, species succeeded or were found only in firm sourdoughs, and strains differed between firm and liquid conditions (Fig. 2A to D). Sourdough MA harbored Leuc. mesenteroides, Leuc. citreum, L. plantarum, Leuconostoc lactis, Lactoccocus lactis, and W. cibaria (Fig. 2A). Apart from firm or liquid conditions, strains of Leuc. mesenteroides (strain 1 [s1]) and Leuc. citreum (s1) persisted throughout propagation. Other strains of Leuc. citreum (s4 and s5) occurred from days 14 and 21 on only in liquid sourdough. On the other hand, strains of L. plantarum (s1) and Leuconostoc lactis (s1) persisted only in firm sourdough. One strain of Leuc. citreum (s2) dominated throughout the propagation of sourdoughs MBF and MBL (Fig. 2B). One strain of L. plantarum (s1) was identified during late propagation of only firm sourdough. One strain of L. sanfranciscensis (s1) persisted up to 14 days only in MBF. Among the five species of lactic acid bacteria that were identified in sourdough MC (Fig. 2C), strains of Leuc. citreum (s2 and s3) dominated the microbiota of both the firm and liquid sourdoughs. Strains of L. plantarum (s1), Leuc. mesenteroides (s2), and L. brevis (s1) were identified only in firm sourdough, whereas Leuc. mesenteroides (s1) was found only in liquid sourdough throughout the 28 days. Among the six species of lactic acid bacteria that were identified in sourdough A (Fig. 2D), strains of Leuc. citreum (s2 and s4) were always dominant. Two strains of L. sanfranciscensis (s1 and s2) persisted only in the firm sourdough for up to 21 and 7 days, respectively. One strain of L. plantarum (s2) was dominant throughout the propagation of AF. Leuc. mesenteroides (strain s2) was identified and persisted only in sourdough AL.

FIG 2.

Species and bacterial strains of lactic acid bacteria identified through the culture-dependent method in the four sourdoughs propagated under firm and liquid conditions for 1 (I), 7 (II), 14 (III), 21 (IV), and 28 (V) days. The black and white squares indicate the presence or absence of strains, respectively. The ingredients and technological parameters used for daily sourdough backslopping are reported in Table 1. (A) MA. (B) MB. (C) MC. (D) A.

Microbial diversity and biochemical characteristics.

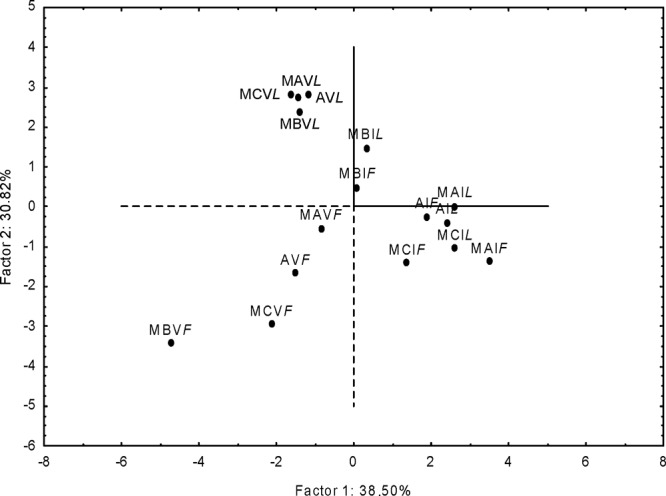

Figure 3 shows the PCA based on DGGE profiles, number of species and strains of lactic acid bacteria (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), percentages of obligately and facultatively heterofermentative lactic acid bacterial species, cell density of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts, and biochemical characteristics (pH, TTA, concentration of lactic and acetic acids, FQ, and FAA) throughout propagation. PCA showed two significant PCs that explained 38.5% (PC1) and 30.82% (PC2) of the total variance of the data. Apart from the type of sourdough, the distribution on the plane was determined by time of backslopping and firm or liquid propagation. After 1 day of propagation, firm and liquid sourdoughs were almost in the same zone of the plane, whereas after 28 days, they were scattered in two different zones, depending on the method of propagation. In particular, liquid sourdoughs were correlated with high numbers of DGGE bands, high numbers of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts, low numbers of species and strains, and high and low percentages of obligately and facultatively heterofermentative species, respectively. The opposite features, which determined the opposite distributions, were shown by firm sourdoughs after 28 days of propagation. The distribution of sourdoughs also reflected the different biochemical characteristics, which agreed with data from permutation analysis (Fig. 1; see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 3.

Score plot of first and second principal components after principal-component analysis based on profiles of the microbial community (numbers of bands in DGGE profiles of lactic acid bacteria, numbers of species and strains of lactic acid bacteria, percentages of obligately and facultatively heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria, and cell densities [log CFU g−1] of presumptive lactic acid bacteria and yeasts) and pH values, total titratable acidity (milliliters of 0.1 N NaOH/10 g), free amino acids (mg kg−1), lactic acid and acetic acid concentrations (mmol kg−1), and fermentation quotients of the four sourdoughs propagated under firm and liquid conditions for 1 (I) and 28 (V) days. The ingredients and technological parameters used for daily sourdough backslopping are reported in Table 1.

Typing and identification of yeasts and acetic acid bacteria.

After a preliminary morphological screening, 139 isolates of yeasts (ca. 30 for each sourdough) were subjected to RAPD-PCR (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Cluster analysis of the RAPD-PCR profiles revealed diversity levels among isolates that ranged from 5 to 35% (data not shown). Isolates showing RAPD-PCR profiles with a maximum level of diversity of 10% were grouped in the same cluster (6, 7, 8, and 7 clusters were found for MA, MB, MC, and A, respectively). The majority of isolates were grouped based on firm or liquid propagation. The following species were identified: S. cerevisiae (sourdough MAF and MAL) and C. humilis (sourdough MAL); Saccharomyces servazzii (sourdough MBF) and S. cerevisiae (sourdoughs MBF and MBL); S. cerevisiae and Torulaspora delbrueckii (sourdoughs MCF and MCL); and S. cerevisiae, C. humilis (sourdoughs AF and AL), and T. delbrueckii (sourdough AF).

Gram-negative, oxidase-negative, catalase-positive cocci or rods (ca. 140 isolates of acetic acid bacteria) were subjected to RAPD-PCR analysis (data not shown). Cluster analysis of the RAPD-PCR profiles revealed diversities of 7.5 to 40%. Most of the isolates were grouped based on firm or liquid propagation. The following species were identified: G. oxydans, A. malorum, and Gluconobacter sp. (sourdoughs MAF and MAL); Gluconobacter frauterii (sourdough MAF); G. oxydans and Gluconobacter sp. (sourdoughs MBF and MBL); G. oxydans and A. malorum (sourdoughs MCF and MCL) and G. frauterii (sourdough MCF); and G. oxydans and A. malorum (sourdoughs AF and AL), Gluconobacter sp. (sourdough AF), and G. frauterii (sourdough AL).

Volatile components.

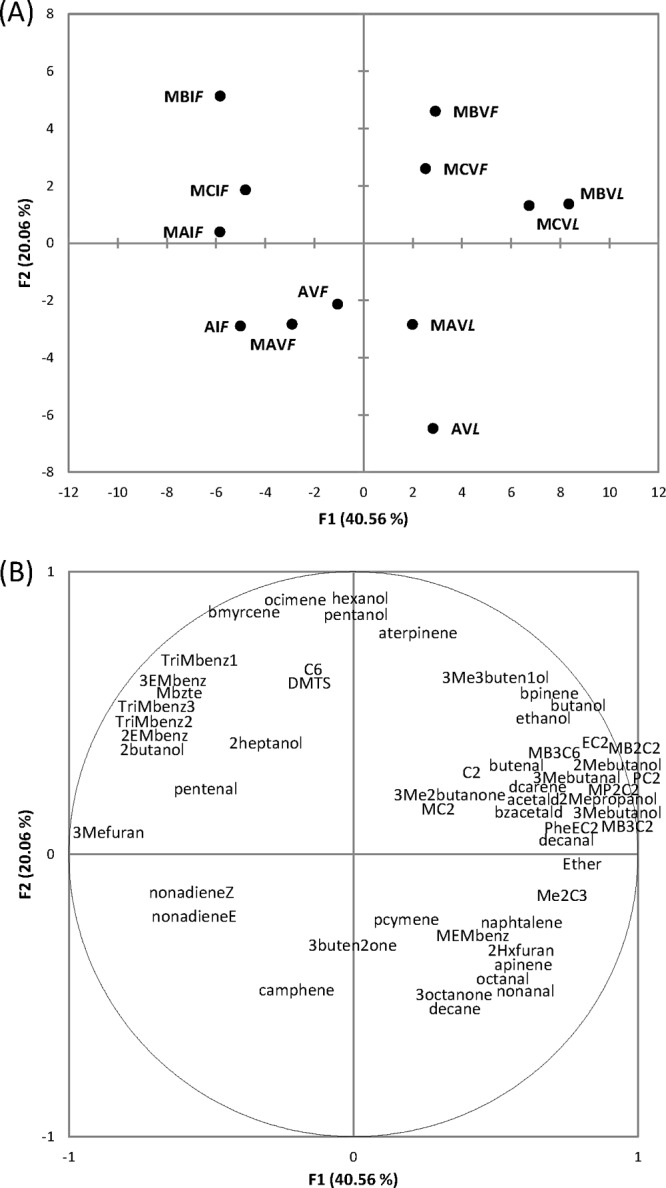

Based on the previous results, which showed only a few differences between firm and liquid sourdoughs after 1 day of propagation, volatile components were analyzed in sourdoughs only after 28 days of propagation and using the firm sourdough at 1 day as the reference. A total of 197 volatile components, which belonged to various chemical classes, were identified through PT–/SPME–GC-MS. Table 3 shows the volatile components that mainly (P < 0.05) differentiated sourdoughs. Nevertheless, only some of them may contribute to the aroma of sourdough baked goods, which varies, depending on the odor activity value (44–46). The data were elaborated through PCA (Fig. 4A and B). The two PCs explained ca. 60% of the total variance of the data. Firm and liquid sourdoughs differed, and as determined by the two PCs (factors), were located in different zones of the plane. According to factor 1 (40.56%), liquid sourdoughs were distributed oppositely to firm sourdoughs at 1 day of propagation. After 28 days of propagation, firm sourdoughs were located at the same distance from the two groups. According to factor 2 (20.06%), sourdoughs MB and MC were separated from MA and A. Overall, aldehydes (e.g., 3-methyl-butanal, octanal, nonanal, and decanal) (44, 46) were found at almost the highest levels in liquid sourdoughs. The same was found for several alcohols (e.g., 1-butanol, 2-methyl-1-propanol, and 3-methyl-1-butanol) (44–46), especially in sourdough MA. Except for ethyl acetate and methyl acetate, which were identified mainly in firm sourdoughs, esters such as propyl acetate, 2-methyl-propyl acetate, 3-methyl-butyl acetate, 2-methyl-butyl acetate, and 2-phenylethyl acetate were also at the highest levels in liquid sourdoughs. Also, ketones, such as 3-octanone and 3-methyl-butanone, mainly characterized liquid sourdoughs. Compared to liquid sourdoughs, the firm sourdoughs contained higher levels of sulfur compounds (e.g., dimethyl-trisulfide) (47), terpenes (e.g., beta-pinene, camphene, and p-cymene), and furans, benzene derivatives, and hydrocarbons. Among the volatile free fatty acids, acetic and caproic acids were found at the highest levels in firm sourdoughs.

TABLE 3.

Concentrations of volatile free fatty acids and volatile components identified in the four sourdoughs propagated under firm and liquid conditions for different times

| Acid or componenta | Concnb |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAI | MAVL | MAVF | MBI | MBVL | MBVF | MCI | MCVL | MCVF | AI | AVL | AVF | |

| VFFA | ||||||||||||

| Acetic acid | 514cd | 446d | 774bc | 863b | 824b | 1040a | 459d | 643c | 1178a | 283e | 953ab | 847b |

| 2-Methyl-propionic acid | 0.27bc | 0.40b | 0.33b | 0.20c | 0.40b | 0.38b | 0.20c | 0.36b | 0.52a | 0.08d | 0.51a | 0.31b |

| Caproic acid | 2.37a | 0.96c | 2.82a | 2.56a | 1.38b | 2.69a | 2.03a | 1.86ab | 3.13a | 0.71c | 0.98c | 0.90c |

| VOC | ||||||||||||

| Acetaldehyde | 1.6E6c | 3.5E6b | 2.4E6bc | 1.8E6c | 4.7E6a | 4.8E6a | 3.5E6b | 6.1E6a | 4.7E6a | 1.7E6c | 3.0Eb | 5.7E6a |

| Octanal | 3.7E5bc | 5.9E5b | 3.6E5bc | 5.6E5b | 6.9E5b | 4.0E5b | 2.9E5c | 7.1E5b | 5.4E5b | 5.0E5b | 1.2E6a | 4.1E5b |

| Nonanal | 1.4E6c | 2.0E5b | 2.1E6b | 2.0E5b | 2.7E5b | 2.0E5b | 1.2E5c | 3.4E6ab | 2.2E5b | 2.5E5b | 4.0E5a | 2.3E5b |

| Decanal | 1.2E5c | 4.3E5ab | 3.5E5b | 4.2E5ab | 5.0E5a | 5.1E5a | 2.1E5c | 4.9E5a | 5.1E5a | 3.8E5b | 4.9E5a | 3.7E5b |

| 2-Butenal (Z) | 3.6E4c | 5.0E4b | 3.6E4c | 4.3E4b | 5.2Ea | 4.5E4b | 4.5E4b | 4.6E4b | 3.8E4b | 3.1E4bc | 4.2E4b | 2.5E4c |

| 2-Pentenal | 4.4E5ab | 2.4E5bc | 3.7E5b | 3.0E5b | 2.6E5bc | 2.8E5b | 5.0E5a | 3.2E5b | 4.3E5ab | 4.1E5ab | 2.4E5bc | 2.0E5c |

| 3-Methyl-butanal | 1.7E5c | 6.0E5b | 1.4E5c | 1.5E5c | 2.1E6a | 1.0E6ab | 4.9E5bc | 2.0E6a | 1.3E6ab | 1.5E5c | 7.0E5b | 3.2E5bc |

| Benzeneacetaldehyde | 2.9E5c | 1.5E6b | 1.0E5c | 2.6E5c | 4.1E6a | 7.7E5bc | 1.9E5c | 2.9E6ab | 9.3E5bc | 2.0E5c | 6.5E5bc | 1.9E5c |

| Ethanol | 9.7E7b | 2.1E8a | 3.5E7c | 2.2E8a | 3.7E8a | 3.3E8a | 2.7E8a | 3.8E8a | 3.8E8a | 1.6E8a | 1.8E8a | 3.3E8a |

| 1-Butanol | 7.8E5b | 1.2E6ab | 9.3E5b | 9.6E5b | 1.7E6a | 1.7E6a | 8.3E5bc | 1.7E6a | 1.6E6a | 6.8E5c | 7.9E5b | 6.8E5c |

| 2-Butanol | 5.1E5a | 1.4E5a | 8.6E4b | 8.4E5a | 0.0E0c | 0.0E0c | 7.9E5a | 8.8E3bc | 2.6E4bc | 1.5E5a | 2.0E2c | 2.0E2c |

| 2-Methyl-1-propanol | 4.9E5c | 4.5E6b | 2.4E5c | 2.8E5c | 1.3E7a | 6.0E6b | 1.4E6bc | 9.8E6ab | 4.9E6b | 6.1E5bc | 3.6E6b | 4.5E6b |

| 3-Methyl-1-butanol | 7.1E6c | 8.3E7b | 3.2E6c | 2.3E6c | 2.1E8a | 1.1E8a | 1.8E7ab | 1.6E8a | 8.7E7b | 4.2E6c | 8.5E7b | 4.4E7ab |

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol | 1.4E6bc | 1.7E7ab | 7.7E5c | 6.6E5c | 4.0E7a | 2.3E7ab | 4.6E6b | 3.6E7a | 1.9E7ab | 4.5E5c | 9.8E6b | 4.1E6b |

| 3-Octanone | 1.1E5b | 1.3E5ab | 8.7E4bc | 1.0E5b | 1.1E5b | 8.1E4bc | 6.5E4c | 1.3E5ab | 9.7E4b | 1.0E5b | 1.8E5a | 7.5E4bc |

| 3-Methyl-2-butanone | 1.3E5b | 1.3E5b | 7.4E4bc | 1.5E5ab | 1.8E5a | 1.1E5b | 1.1E5b | 1.4E5b | 9.9E4bc | 1.2E5b | 1.3E5b | 5.6E4c |

| Methyl acetate | 3.1E5bc | 7.0E5b | 6.3E5b | 3.7E5bc | 4.3E5b | 1.5E6a | 5.7E5b | 5.2E5b | 1.4E6a | 2.8E5c | 7.3E5b | 1.4E6a |

| Methyl benzoate | 3.9E4b | 6.6E3c | 1.0E4bc | 8.8E4a | 1.5E4bc | 1.7E4bc | 3.1E4b | 1.6E4bc | 2.1E4bc | 4.2E4b | 5.5E3c | 9.1E3c |

| Ethyl acetate | 9.6E7d | 1.8E8c | 1.1E8b | 1.6E8c | 2.9E8a | 3.1E8a | 1.1E8d | 2.8E8b | 2.3E8ab | 1.2E8d | 1.7E8c | 2.1E8b |

| Propyl acetate | 1.2E5c | 9.0E5b | 1.4E5c | 3.8E5bc | 3.6E6a | 2.6E6a | 2.9E5bc | 3.0E6a | 1.2E6a | 1.4E5c | 8.8E5b | 1.4E6a |

| 2-Methyl-propyl acetate | 4.5E4c | 1.8E6a | 3.3E4c | 6.3E4c | 5.8E6a | 3.8E6a | 1.8E5b | 4.3E6a | 1.6E6a | 5.3E4c | 1.4E6a | 2.0E6a |

| 3-Methyl-butyl acetate | 4.5E5c | 2.5E7a | 2.9E5c | 3.1E5c | 5.3E7a | 4.0E7a | 1.9E6b | 4.2E7a | 2.0E7a | 2.5E5c | 3.0E7a | 1.3E7a |

| 2-Methyl-butyl acetate | 1.1E5bc | 4.3E6b | 8.6E4c | 9.7E4c | 1.3E7a | 9.2E6ab | 4.6E5bc | 9.7E6ab | 4.3E6b | 3.9E4c | 2.6E6b | 1.1E6b |

| 3-Methyl-butyl hexanoate | 3.1E3bc | 2.2E4b | 2.0E2c | 3.5E3bc | 7.9E4a | 3.4E4b | 0.0E0c | 7.6E4a | 2.6E4b | 9.4E2c | 6.5E3bc | 2.9E3bc |

| 2-Phenyl-ethyl acetate | 1.3E5d | 5.4E5bc | 3.9E3g | 9.4E4e | 1.3E6a | 2.0E5c | 3.7E4f | 7.3E5b | 3.7E5c | 7.5E4ef | 1.6E5d | 9.0E4e |

| Carbon disulfide | 1.0E4cd | 1.6E4c | 2.8E4b | 3.0E4b | 1.1E4cd | 2.7E4b | 2.9E4b | 8.7E3d | 2.8E4b | 3.4E4b | 1.9E4c | 6.5E4a |

| Dimethyl-trisulfide | 4.4E3c | 3.2E3cd | 4.8E3c | 7.6E3b | 4.8E3c | 9.1E3a | 7.6E3b | 4.8E3c | 8.1E3ab | 4.7E3c | 2.1E3d | 9.9E3a |

| 3-Methyl-furan | 2.0E5ab | 3.0E4d | 1.8E5b | 2.1E5ab | 5.3E3e | 2.6E4d | 1.6E5b | 5.1E3e | 8.8E4c | 2.4E5a | 1.9E4d | 4.9E4cd |

| 2-Hexyl-furan | 2.1E5b | 4.3E5a | 2.5E5b | 2.6E5b | 4.5E5a | 1.9E5b | 2.0E5b | 3.0E5b | 2.1E5b | 1.9E5bc | 4.7E5a | 1.4E5c |

| Diethyl-ether | 4.8E3c | 4.5E4ab | 2.2E4b | 5.9E3c | 5.6E4a | 6.0E4a | 3.8E4ab | 6.1E4a | 6.7E4a | 1.6E4bc | 5.5E4a | 6.5E4a |

| Decane | 3.1E5cd | 9.6E5b | 2.3E5d | 4.6E5c | 8.1E5b | 3.0E5d | 2.3E5d | 4.2E5c | 3.4E5cd | 7.7E5b | 1.1E6a | 2.5E5d |

| Nonadiene1 | 1.3E5b | 6.3E4d | 1.0E5bc | 1.6E5b | 4.6E4e | 1.2E5bc | 1.3E5b | 4.6E4e | 8.2E4c | 1.8E5ab | 1.4E5b | 3.0E5a |

| Nonadiene2 | 1.5E5b | 6.5E4d | 1.2E5c | 1.7E5bc | 5.0E4d | 1.4E5b | 1.5E5b | 5.3E4d | 1.0E5c | 2.0E5ab | 1.4E5b | 3.1E5a |

| Ethyl,3-methyl-benzene | 1.5E5b | 8.3E4c | 9.5E4c | 2.2E5a | 8.7E4c | 1.6E5b | 1.4E5b | 1.1E5bc | 1.1E5bc | 1.6E5b | 8.8E4c | 1.1E5bc |

| 1-Methyl,2-ethyl-benzene | 2.1E5ab | 1.1E5b | 1.1E5b | 3.5E5a | 9.9E4c | 1.7E5b | 2.0E5ab | 1.3E5b | 1.4E5b | 2.2E5ab | 1.2E5b | 2.1E5ab |

| 1,2,3-Trimethyl-benzene | 2.1E5b | 1.3E5d | 1.4E5cd | 2.9E5a | 1.4E5cd | 2.3E5b | 2.1E5b | 1.8E5bc | 1.6E5c | 2.2E5b | 1.3E5d | 1.6E5c |

| 1,3,5-Trimethyl-benzene | 7.4E5b | 4.1E5c | 4.5E5c | 1.2E6a | 3.7E5c | 7.2E5b | 7.3E5b | 4.9E5c | 5.5E5bc | 8.1E5b | 4.6E5c | 5.8E5bc |

| 1,2,4-Trimethyl-benzene | 2.9E5b | 1.7E5bc | 1.9E5bc | 4.5E5a | 1.5E5c | 2.6E5b | 2.8E5b | 1.9E5bc | 2.3E5b | 3.0E5b | 2.0E5b | 2.2E5b |

| Naphtalene | 7.2E5c | 8.1E5bc | 9.4E5bc | 7.4E5c | 1.1E6b | 1.0E6b | 6.0E5c | 1.4E6a | 1.5E6a | 1.1E6b | 1.3E6ab | 1.5E6a |

| Alpha-pinene | 6.3E4d | 1.0E5b | 7.2E4c | 8.0E4c | 9.6E4bc | 6.6E4d | 7.1E4c | 1.5E5a | 7.6E4c | 7.5E4c | 1.6E5a | 6.6E4d |

| Camphene | 7.1E4e | 7.6E4e | 1.1E5cd | 8.0E4e | 8.7E4e | 1.3E5cd | 7.4E4e | 1.0E5d | 1.1E5d | 4.0E5a | 1.9E5c | 2.8E5b |

| Beta-pinene | 5.4E4cd | 8.0E4c | 4.7E4d | 8.6E4c | 1.2E5ab | 1.3E5a | 7.8E4c | 1.0E5b | 1.2E5ab | 5.7E4cd | 8.3E4c | 4.1E4d |

| Beta-myrcene | 3.2E5a | 1.9E5c | 2.5E5b | 3.3E5a | 2.4E5b | 3.2E5a | 3.2E5a | 2.4E5b | 3.0E5a | 2.2E5b | 1.7E5c | 2.4E5b |

| Delta-carene | 2.8E4c | 4.4E4b | 6.3E4ab | 3.1E4bc | 4.8E4b | 7.1E4a | 2.6E4c | 7.5E4a | 5.6E4ab | 2.9E4c | 3.4E4bc | 4.2E4b |

| p-Cymene | 3.1E5c | 2.9E5d | 5.1E5a | 3.1E5c | 3.0E5d | 4.4E5b | 2.6E5d | 3.6E5c | 4.9E5b | 2.9E5d | 4.6E5b | 5.3E5a |

| 1(1-methyl-1-ethenyl)-4-methyl-benzene | 6.1E4c | 5.5E4cd | 8.8E4a | 5.8E4cd | 6.5E4c | 7.6E4b | 5.0E4d | 8.5E4ab | 7.9E4b | 4.9E4d | 9.0E4a | 9.3E4a |

Compounds that, based on the literature (44–47), may have an impact on the aroma of sourdough baked goods are in boldface.

VFFA are reported in ppm and VOC in arbitrary units of area. Only VOC that showed variation (P ≤ 0.05) between samples are reported. The ingredients and technological parameters used for daily sourdough backslopping are reported in Table 1. Times were as follows: 1 (I) and 28 (V) days. The data are the means of three independent experiments, and values in the same row followed by different lowercase letters (a to g) differ significantly (P ≤ 0.05).

FIG 4.

Score plot (A) and loading plot (B) of first and second principal components after principal-component analysis based on volatile components that mainly (P < 0.05) differentiated the four sourdoughs propagated under firm and liquid conditions for 1 (I) and 28 (V) days. The ingredients and technological parameters used for daily sourdough backslopping are reported in Table 1. C2, acetic acid; C6, caproic acid; Me2C3, 2-methyl-propionic acid; 3Mebutanal, 3-methyl-butanal; bzacetald, benzeneacetaldehyde; 2Mepropanol, 2-methyl-1-propanol; 3Mebutanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol; 2Mebutanol, 2-methyl-1-butanol; 3Me3buten1ol, 3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol; 3buten2one, 3-buten-2-one; 3Me2butanon3, 3-methyl-2-butanone; MC2, methyl acetate; Mbzte, methyl benzoate; EC2, ethyl acetate; PC2, propyl acetate; MP2C2, 2-methyl-propyl acetate; MB3C2, 3-methyl-butyl acetate; MB2C2, 2-methyl-butyl acetate; MB3C6, 3-methyl-butyl hexanoate; PheEC2, 2-phenyl-ethyl acetate; DMTS, dimethyl-trisulfide; 3Mefuran, 3-methyl-furan; 2Hxfuran, 2-hexyl-furan; Ether, diethyl-ether; 3EMbenz, 1-ethyl,3-methyl-benzene; 2EMbenz, 1-ethyl,2-methyl-benzene; TriMbenz1, 1,x,y-trimethyl-benzene; TriMbenz2, 1,w,z-trimethyl-benzene; TriMbenz3, 1,3,5-trimethyl-benzene; apinene, alpha-pinene; bmyrcene, beta-myrcene; dcarene, delta-carene; aterpinene, alpha-terpinene; pcymene, p-cymene; MEMbenz, 1(1-methyl-1-ethenyl)-4-methyl-benzene; bpinene, beta-pinene.

DISCUSSION

Four traditional type I sourdoughs were comparatively propagated under firm (DY = 160) and liquid (DY = 280) conditions to address two questions. What happens to sourdoughs when switched from firm to liquid fermentation, and could the liquid-sourdough fermentation be considered another technology option for making traditional baked goods, keeping the characteristics constant? Although mature and used for at least 2 years, firm sourdoughs confirmed the fluctuations of some biochemical and microbial characteristics during daily propagation (7, 23). In spite of this, and though the number of isolates was probably not exhaustive enough to describe all the species and strain diversity, the main traits differentiating firm and liquid sourdoughs emerged from this study, and some responses to the above queries were provided.

The cell density of presumptive lactic acid bacteria and related biochemical features (e.g., pH, TTA, and concentration of organic acids) were affected by the method of propagation. Permutation analysis based on the above parameters rather clearly separated firm and liquid sourdoughs. After 28 days of propagation, firm sourdoughs had slightly higher pH values (4.29 to 4.33) than the liquid sourdoughs (4.20 to 4.22). These differences did not reflect the TTA, which was highest on firm sourdoughs. Indeed, the latter had the highest concentrations of lactic and especially acetic acids. Overall, the concentration of acetic acid increased throughout propagation, and firm sourdoughs showed the greatest increases. Low DY values amplify the buffering capacity of the flour, thereby lowering the rate of acidification even in the presence of higher levels of organic acids (15). The synthesis of acetic acid is negatively affected under liquid conditions (21, 48), even though it was found in a large number of obligately heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria, which probably synthesized more ethanol than acetic acid. Despite these differences, the molar ratio between lactic and acetic acids, and the resulting FQ, were similar between firm and liquid sourdoughs at the end of propagation. Cell numbers of presumptive lactic acid bacteria moderately fluctuated in firm sourdoughs. On the other hand, the numbers were more stable in liquid sourdoughs, probably due to better environmental diffusion of carbohydrates, FAA, and other nutrients (49). The cell density of yeasts in most of the liquid sourdoughs was markedly higher than that found in the firm sourdoughs. The higher the water content of the sourdough, the greater the growth of yeasts should be (16). Sequencing of the main bands from DGGE profiles, revealed the presence of S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus-Kazachstania sp. in almost all sourdoughs. Only in the firm sourdough MA was the DNA band corresponding to S. cerevisiae not more detectable from day 14 on. After 28 days of propagation, two new bands appeared in the liquid sourdough MA, one of which corresponded to Kazachstania sp.-K. unispora. C. humilis, K. barnettii, Kazachstania exigua, and S. cerevisiae are the dominant yeasts in Italian bakery sourdoughs (15). Overall, S. cerevisiae is the species of yeast most frequently isolated in sourdoughs from central and southern Italy (2, 50, 51). Recently, it was shown that the composition of the yeast microbiota differed between artisan bakery and laboratory sourdoughs (23), and the persistence of S. cerevisiae might be due to contamination of the bakery environment with commercial baker's yeast. All the firm sourdoughs, which showed decreased numbers of yeasts, had the highest concentration of FAA. The opposite was found for liquid sourdoughs. The consumption of free amino acids by yeasts was previously described during sourdough fermentation (52). Almost the same species of yeasts were identified, and the same information was obtained, through a culture-dependent approach. The only exceptions were S. servazzii (sourdough MBF) and T. delbrueckii (sourdoughs MCF, MCL, and AF).

Several species of lactic acid bacteria were variously identified during propagation under firm and liquid conditions. Overall, they corresponded to the dominant or frequently identified facultatively and obligately heterofermentative species under low incubation temperatures and continuous backslopping, which characterize traditional type I sourdoughs (2, 3, 15). Identification occurred repeatedly and at short intervals (7 days), which should have allowed reliable detection of the microbial succession. Some species (e.g., W. cibaria, Lactococcus lactis, and L. sakei) and strains were only occasionally found, while others seemed to be representative of the microbiota. Regardless of the type of sourdough, those propagated under liquid conditions showed a simplified microbial diversity over time (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Furthermore, liquid sourdoughs harbored a low number of strains, which, however, persisted. L. plantarum dominated in all firm sourdoughs over time, but not in the corresponding liquid sourdoughs. Several strains of L. plantarum seemed to share phenotypic traits, which determined the capacity to outcompete the contaminating lactic acid bacterium biota (25). Leuconostoc lactis and L. brevis dominated only the firm sourdoughs MA and MC, respectively. L. sanfranciscensis persisted for some time only in some firm sourdoughs (MB and A). Although L. sanfranciscensis is considered a stable inhabitant of traditional type I sourdoughs, its competitiveness is markedly intraspecific and depends on a number of technological and environmental parameters (53, 54). Leuc. citreum persisted in all firm and liquid sourdoughs. Leuc. citreum was also the only species detected in liquid sourdoughs at all times and was accompanied by Leuc. mesenteroides in the liquid sourdoughs MC and A. Overall, Leuconostoc species adapt well and grow at low temperatures (e.g., 10°C), such as that used in this study between backsloppings (55). Flour and the house microbiota are the main factors perturbing the microbial stability of the sourdough during propagation (12, 56). During liquid propagation, a smaller amount of flour is used than for firm sourdough. This would reduce the influence of bacteria derived from flour and, in general, would lead to a less competitive pressure and environment. Under these conditions, all the liquid sourdoughs shift to a microbiota almost exclusively composed of Leuconostoc species.

Several studies (23, 57, 58) have shown that subpopulations of pediococci, enterococci, and acetic acid bacteria are also part of the sourdough microbiota under certain conditions of propagation. Theoretically, liquid propagation was considered to be particularly suitable for acetic acid bacteria. Based on this consideration, the microbial group was also investigated in this study. Nevertheless, no consistent differences were found between firm and liquid sourdoughs, and especially, the number of acetic acid bacteria seemed to be irrelevant compared to lactic acid bacteria and yeasts.

Overall, the synthesis of VOC is mainly due to the metabolic activities of yeasts and lactic acid bacteria (45, 46). After 28 days of propagation, firm and liquid sourdoughs were scattered as shown in Fig. 4 (cf. Table 3), depending on the levels of several VOC, which, together with nonvolatile compounds (46), would have an impact on the sensory features of baked goods. Alcohols (e.g., 1-butanol, 2-methyl-1-propanol, and 3-methyl-1-butanol), which mainly derived from the metabolism of free amino acids by lactic acid bacteria and, especially, yeasts, were at the highest levels in liquid sourdoughs that harbored the highest numbers of yeasts and the lowest levels of free amino acids (44). Some aldehydes (e.g., octanal, nonanal, decanal, and 3-methyl-butanal) and 3-octanone were also at the highest levels in liquid sourdoughs. Firm sourdoughs mainly contained ethyl-acetate, acetic acid, and related methyl- and ethyl-acetates, dimethyl-trisulfide, and terpenes (e.g., beta-pinene, camphene, and p-cymene) (44–47). Ethyl-acetate and acetic acid are compounds that markedly affect the flavor of baked goods (46). Also, all firm sourdoughs contained a higher concentration of FAA than liquid sourdoughs. Notwithstanding the contributions of cereal proteases and the metabolism of free amino acids by yeasts, secondary proteolysis by sourdough lactic acid bacteria is another metabolic activity that contributes to the development of typical sourdough baked good flavors (8, 59).

A number of bakeries consider liquid sourdough fermentation an effective technology option to decrease some drawbacks associated with the traditional daily backslopping of firm sourdoughs. This option is also considered for the manufacture of traditional/typical breads. Although only four sourdoughs were examined in this study, the switch from firm to liquid sourdough seemed to consistently modify the composition of the sourdough microbiota, especially regarding lactic acid bacteria, and the related biochemical features. Although we did not make a comparative quality assessment, undoubtedly the use of liquid fermentation would change the main microbial and biochemical features of traditional/typical baked goods.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 March 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00309-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Istituto Nazionale di Sociologia Rurale. 2000. Atlante dei prodotti tipici: il pane, p 13 Agra-Rai Eri, Rome, Italy [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minervini F, Di Cagno R, Lattanzi A, De Angelis M, Antonielli L, Cardinali G, Cappelle S, Gobbetti M. 2012. Lactic acid bacterium and yeast microbiotas of 19 sourdoughs used for traditional/typical Italian breads: interactions between ingredients and microbial species diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:1251–1264. 10.1128/AEM.07721-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Vuyst L, Vrancken G, Ravyts F, Rimaux T, Weckx S. 2009. Biodiversity, ecological determinants, and metabolic exploitation of sourdough microbiota. Food Microbiol. 26:666–675. 10.1016/j.fm.2009.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gobbetti M. 1998. Interactions between lactic acid bacteria and yeasts in sourdoughs. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 9:267–274. 10.1016/S0924-2244(98)00053-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gobbetti M, Rizzello CG, Di Cagno R, De Angelis M. 2014. How the sourdough may affect the functional features of leavened baked goods. Food Microbiol. 37:30–40. 10.1016/j.fm.2013.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel RF, Müller MRA, Stolz P, Ehrmann MA. 1996. Ecology in sourdough produced by traditional and modern technologies. Adv. Food Sci. 18:152–159 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ercolini D, Pontonio E, De Filippis F, Minervini F, La Storia A, Gobbetti M, Di Cagno R. 2013. Microbial ecology dynamics during rye and wheat sourdough preparation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:7827–7836. 10.1128/AEM.02955-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobbetti M, De Angelis M, Corsetti A, Di Cagno R. 2005. Biochemistry and physiology of sourdough lactic acid bacteria. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 16:57–69. 10.1016/j.tifs.2004.02.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gänzle MG, Vogel RF. 2003. Contribution of reutericyclin production to the stable persistence of Lactobacillus reuteri in an industrial sourdough fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 80:31–45. 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00146-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammes WP, Stolz P, Gänzle M. 1996. Metabolism of lactobacilli in traditional sourdoughs. Adv. Food Sci. 18:176–184 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gänzle MG, Vermeulen N, Vogel RF. 2007. Carbohydrate, peptide and lipid metabolism of lactic acid bacteria in sourdough. Food Microbiol. 24:128–138. 10.1016/j.fm.2006.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minervini F, De Angelis M, Di Cagno R, Gobbetti M. 2014. Ecological parameters influencing microbial diversity and stability of traditional sourdough. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 171:136–146. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Vuyst L, Neysens P. 2005. Biodiversity of sourdough lactic acid bacteria. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 16:43–56. 10.1016/j.tifs.2004.02.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vuyst L, Schrijvers V, Paramithiotis S, Hoste B, Vancanneyt M, Swings J, Kalantzopoulos G, Tsakalidou E, Messens W. 2002. The biodiversity of lactic acid bacteria of Greek traditional wheat sourdoughs is reflected in both composition and metabolite formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6059–6069. 10.1128/AEM.68.12.6059-6069.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Vuyst L, Van Kerrebroeck S, Harth H, Huys G, Daniel H-M, Weckx S. 2014. Microbial ecology of sourdough fermentations: diverse or uniform? Food Microbiol. 37:11–29. 10.1016/j.fm.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gianotti A, Vannini L, Gobbetti M, Corsetti A, Gardini F, Guerzoni ME. 1997. Modelling of the activity of selected starters during sourdough fermentation. Food Microbiol. 14:327–337. 10.1006/fmic.1997.0099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacaze G, Wick M, Cappelle S. 2007. Emerging fermentation technologies: development of novel sourdoughs. Food Microbiol. 24:155–160. 10.1016/j.fm.2006.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carnevali P, Ciati R, Leporati A, Paese M. 2007. Liquid sourdough fermentation: industrial application perspectives. Food Microbiol. 24:150–154. 10.1016/j.fm.2006.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mastilovic J, Popov S. 2001. Investigation of rheological properties of liquid sourdough, p 53–62 Proceedings of the 3rd Croatian Congress of Cereal Technologists, Opatija, Croatia University of Osijek, Opatija, Croatia [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandt MJ. 2007. Sourdough products for convenient use in baking. Food Microbiol. 24:161–164. 10.1016/j.fm.2006.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banu I, Vasilean I, Aprodu I. 2011. Effect of select parameters of the sourdough rye fermentation on the activity of some mixed starter cultures. Food Biotechnol. 25:275–291. 10.1080/08905436.2011.617251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogelmann SA, Hertel C. 2011. Impact of ecological factors on the stability of microbial associations in sourdough fermentation. Food Microbiol. 28:583–589. 10.1016/j.fm.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minervini F, Lattanzi A, De Angelis M, Di Cagno R, Gobbetti M. 2012. Influence of artisan bakery- or laboratory-propagated sourdoughs on the diversity of lactic acid bacterium and yeast microbiotas. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:5328–5340. 10.1128/AEM.00572-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Angelis M, Di Cagno R, Gallo G, Curci M, Siragusa S, Crecchio C, Parente E, Gobbetti M. 2007. Molecular and functional characterization of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis strains isolated from sourdoughs. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 114:69–82. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minervini F, De Angelis M, Di Cagno R, Pinto D, Siragusa S, Rizzello CG, Gobbetti M. 2010. Robustness of Lactobacillus plantarum starters during daily propagation of wheat flour sourdough type I. Food Microbiol. 27:897–908. 10.1016/j.fm.2010.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walter J, Hertel C, Tannock GW, Lis CM, Munro K, Hammes WP. 2001. Detection of Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, and Weissella species in human feces by using group-specific PCR primers and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2578–2585. 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2578-2585.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camu N, De Winter T, Verbrugghe K, Cleenwerck I, Vandamme P, Takrama JS, Vancanneyt M, De Vuyst L. 2007. Dynamics and biodiversity of populations of lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria involved in spontaneous heap fermentation of cocoa beans in Ghana. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1809–1824. 10.1128/AEM.02189-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cocolin L, Bisson LF, Mills DA. 2000. Direct profiling of the yeast dynamics in wine fermentations. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 189:81–87. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleenwerck I, Gonzalez A, Camu N, Engelbeen K, De Vosand P, De Vuyst L. 2008. Acetobacter fabarum sp. nov., an acetic acid bacterium from a Ghanaian cocoa bean heap fermentation. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58:2180–2185. 10.1099/ijs.0.65778-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Los Reyes-Gavilán CG, Limsowtin GKY, Tailliez P, Séchaud L, Accolas JP. 1992. A Lactobacillus helveticus-specific DNA probe detects restriction fragment length polymorphisms in this species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3429–3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corsetti A, De Angelis M, Dellaglio F, Paparella A, Fox PF, Settanni L, Gobbetti M. 2003. Characterization of sourdough lactic acid bacteria based on genotypic and cell-wall protein analysis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94:641–654. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stendid J, Karlsson JO, Hogberg N. 1994. Intra-specific genetic variation in Heterobasidium annosum revealed by amplification of minisatellite DNA. Mycol. Res. 98:57–63. 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80337-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zapparoli G, Torriani S, Dellaglio F. 1998. Differentiation of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis strains by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 166:324–332 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Cagno R, Cardinali G, Minervini G, Antonielli L, Rizzello CG, Ricciuti P, Gobbetti M. 2010. Taxonomic structure of the yeasts and lactic acid bacteria microbiota of pineapple (Ananas comosus L. Merr.) and use of autochthonous starters for minimally processing. Food Microbiol. 27:381–389. 10.1016/j.fm.2009.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Angelis M, Siragusa S, Berloco M, Caputo L, Settanni L, Alfonsi G, Amerio M, Grandi A, Ragni A, Gobbetti M. 2006. Selection of potential probiotic lactobacilli from pig feces to be used as additives in pelleted feeding. Res. Microbiol. 157:792–801. 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torriani S, Felis GE, Dellaglio F. 2001. Differentiation of Lactobacillus plantarum, L. pentosus, and L. paraplantarum by recA gene sequence analysis and multiplex PCR assay with recA gene-derived primers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3450–3454. 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3450-3454.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naser SM, Thompson FL, Hoste B, Gevers D, Dawyndt P, Vancanneyt M, Swings J. 2005. Application of multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) for rapid identification of Enterococcus species based on rpoA and pheS genes. Microbiology 151:2141–2150. 10.1099/mic.0.27840-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trčekl J, Teuber M. 2002. Genetic and restriction analysis of the 16S–23S rDNA internal transcribed spacer regions of the acetic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 208:69–75. 10.1016/S0378-1097(01)00593-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Donnell K. 1993. Fusarium and its near relatives, p 225–233 In Reynolds DR, Taylor JW. (ed), The fungal holomorph: mitotic, meiotic and pleomorphic speciation in fungal systematics. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Cagno R, Surico RF, Paradiso A, De Angelis M, Salmon JC, Buchin S, De Gara L, Gobbetti M. 2009. Effect of autochthonous lactic acid bacteria starters on health-promoting and sensory properties of tomato juices. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 128:473–483. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caraux G, Pinloche S. 2005. PermutMatrix: a graphical environment to arrange gene expression profiles in optimal linear order. Bioinformatics 21:1280–1281. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Birch AN, Petersen MA, Hansen AS. 2013. The aroma profile of wheat bread crumb influenced by yeast concentration and fermentation temperature. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 50:480–488. 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.08.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hansen A, Schieberle P. 2005. Generation of aroma compounds during sourdough fermentation: applied and fundamental aspects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 16:85–94. 10.1016/j.tifs.2004.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rehman S-UR, Paterson A, Piggot JR. 2006. Flavour in sourdough breads: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 17:557–566. 10.1016/j.tifs.2006.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirchhoff E, Schieberle P. 2001. Determination of key aroma compounds in the crumb of a three-stage sourdough rye bread by stable isotope dilution assay and sensory studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49:4304–4311. 10.1021/jf010376b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Decock P, Cappelle S. 2005. Bread technology and sourdough technology. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 16:113–120. 10.1016/j.tifs.2004.04.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spicher G, Stephan H. 1993. Handbuch Sauerteig, Biologie, Biochemie, Technologie. Behr, Hamburg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iacumin L, Cecchini F, Manzano M, Osualdini M, Boscolo D, Orlic S, Comi G. 2009. Description of the microflora of sourdoughs by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Food Microbiol. 26:128–135. 10.1016/j.fm.2008.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valmorri S, Tofalo R, Settanni L, Corsetti A, Suzzi G. 2010. Yeast microbiota associated with spontaneous sourdough fermentations in the production of traditional wheat sourdough breads of the Abruzzo region (Italy). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 97:119–129. 10.1007/s10482-009-9392-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gobbetti M, Corsetti A, Rossi J. 1994. The sourdough microflora. Interactions between lactic acid bacteria and yeasts: metabolism of amino acids. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 10:275–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siragusa S, Di Cagno R, Ercolini D, Minervini F, Gobbetti M, De Angelis M. 2009. Taxonomic structure and monitoring of the dominant population of lactic acid bacteria during wheat flour sourdough type I propagation using Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis starters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:1099–1109. 10.1128/AEM.01524-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vrancken G, Rimaux T, Weckx S, Leroy F, De Vuyst L. 2011. Influence of temperature and backslopping time on the microbiota of a type I propagated laboratory wheat sourdough fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:2716–2726. 10.1128/AEM.02470-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hemme D, Foucaud-Scheunemann C. 2004. Leuconostoc, characteristics, use in dairy technology and prospects in functional foods. Int. Dairy J. 14:467–494. 10.1016/j.idairyj.2003.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scheirlinck I, Van der Meulen R, De Vuyst L, Vandamme P, Huys G. 2009. Molecular source tracking of predominant lactic acid bacteria in traditional Belgian sourdoughs and their production environments. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106:1081–1092. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scheirlinck I, Van Der Meulen R, Van Schoor A, Vancanneyt M, De Vuyst L, Vandamme P, Huys G. 2008. Taxonomic structure and stability of the bacterial community in Belgian sourdough ecosystems assessed by culturing and population fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2414–2423. 10.1128/AEM.02771-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Corsetti A, Settanni L, Valmorri S, Mastrangelo M, Suzzi G. 2007. Identification of subdominant sourdough lactic acid bacteria and their evolution during laboratory-scale fermentations. Food Microbiol. 24:592–600. 10.1016/j.fm.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gaenzle MG, Loponen J, Gobbetti M. 2008. Proteolysis in sourdough fermentations: mechanisms and potential for improved bread quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 19:513–521. 10.1016/j.tifs.2008.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.